Как правильно пишется словосочетание «удостоверение личности»

- Как правильно пишется слово «удостоверение»

- Как правильно пишется слово «личность»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: эргономика — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «удостоверение личности»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «удостоверение личности»

Предложения со словосочетанием «удостоверение личности»

- Но для начала, друзья мои, я вас лично внесу в список жителей нашего славного города и выдам пока, так сказать, справочки, временные удостоверения личности.

- Нами установлено, что они незаконно проникли на планету, воспользовавшись фальшивыми удостоверениями личности.

- Мы входим в невысокое серое здание из шлакоблоков и показываем удостоверения личности бледному мужчине в очках.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «удостоверение личности»

- После праздника все эти преступники оказывались или мелкими воришками, или просто бродяжками из московских мещан и ремесленников, которых по удостоверении личности отпускали по домам, и они расходились, справив сытно праздник за счет «благодетелей», ожидавших горячих молитв за свои души от этих «несчастненьких, ввергнутых в узилища слугами антихриста».

- Перед большими праздниками, к великому удивлению начальства, Лефортовская и Рогожская части переполнялись арестантами, и по всей Москве шли драки и скандалы, причем за «бесписьменность» задерживалось неимоверное количество бродяг, которые указывали свое местожительство главным образом в Лефортове и Рогожской, куда их и пересылали с конвоем для удостоверения личности.

- Еврея велено придержать, а от нигилиста потребовали удостоверения его личности. Он молча подал листок, взглянув на который начальник станции резко переменил тон и попросил его в кабинет, добавив при этом:

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «удостоверение»

- водительское удостоверение

служебное удостоверение

командировочное удостоверение - удостоверение личности

удостоверение сотрудника

удостоверение офицера - номер удостоверения

в поисках удостоверения

красная корочка удостоверения - удостоверение принадлежало

- показать удостоверение

предъявить удостоверение

достать удостоверение - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Сочетаемость слова «личность»

- человеческая личность

отдельные личности

сильная личность - личность человека

личность ребёнка

личность преступника - развитие личности

культ личности

удостоверение личности - личность исчезает

личность формируется

личность представляет - установить личность

стать личностью

являться личностью - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Каким бывает «удостоверение личности»

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «личность»

- Каждая человеческая личность имеет в себе нечто совершенно особенное, совершенно неопределимое внешним образом, не поддающееся никакой формуле…

- Свободная личность значительно больше обогащает общество, чем подневольная.

- Уважайте в себе и других человеческую личность.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

Документы, удостоверяющие личность и их коды

| Код | Наименование документа |

|---|---|

| 03 | Свидетельство о рождении |

| 07 | Военный билет |

| 08 | Временное удостоверение, выданное взамен военного билета |

| 10 | Паспорт иностранного гражданина |

| 11 | Свидетельство о рассмотрении ходатайства о признании лица беженцем на территории РФ по существу |

| 12 | Вид на жительство в РФ |

| 13 | Удостоверение беженца |

| 14 | Временное удостоверение личности гражданина РФ |

| 15 | Разрешение на временное проживание в РФ |

| 19 | Свидетельство о предоставлении временного убежища на территории РФ |

| 21 | Паспорт гражданина РФ |

| 22 | Загранпаспорт гражданина РФ |

| 23 | Свидетельство о рождении, выданное уполномоченным органом иностранного государства |

| 24 | Удостоверение личности военнослужащего РФ |

| 27 | Военный билет офицера запаса |

| 91 | Иные документы* |

Буквенное обозначение, требуемое для некоторых документов приведено в таблице ниже:

Существует целый ряд нормативных актов, в той или иной степени регламентирующих виды и юридическую значимость как документов, удостоверяющих личность, так и их коды.

Нормативное регулирование

Список документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ, в разных вариациях представлен в нескольких нормативных актах, а именно:

Если проанализировать все вышеперечисленные акты и свести представленные в них перечни документов, то список документов, удостоверяющих личность, можно подразделить на две группы – документов гражданина РФ и документов иностранного гражданина, пребывающего или въезжающего на территорию РФ.

Так, перечень документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ, будет примерно следующим:

Перечень документов, удостоверяющих личность иностранных граждан, находящихся или въезжающих на территорию РФ, включает в себя:

Как видно из списка, перечень документов достаточно разнообразен, причем каждый документ из перечня в той или иной степени зависит от вида правоотношений, для которых он создан.

Где применяются двухзначные и буквенные коды

Двухзначный код вида документа используется к примеру в таких формах как:

Буквенный код используется в формах для регистрации в системе обязательного пенсионного страхования, например в:

Основные документы и требования к ним

В настоящее время на территории РФ действуют следующие формы единого основного документа – паспорта гражданина РФ:

Следует уточнить, что действительность паспорта, вне зависимости от его формы, зависит от двух факторов, а именно:

Приравнены на определенный срок по юридической значимости к паспорту гражданина РФ:

Документы иностранцев

Иностранные граждане, находящиеся или въезжающие на территорию РФ, должны обладать один из следующих документов:

Паспорт международного образца, выдаваемый гражданам РФ для поездок за рубеж, хотя и признан удостоверением личности, не является эквивалентом внутреннего паспорта, а потому обладает некоторыми ограничениями в гражданском обороте.

Является ли водительское удостоверение документом, удостоверяющим личность

Чисто юридически водительское удостоверение является лишь документом, подтверждающим право его обладателя управлять транспортным средством.

Однако, в соответствии с Постановлением ГКПИ 06-1016 ВС РФ, водительское удостоверение имеет двоякую функцию, а именно:

Однако существует ряд ведомственных ограничений по гражданскому обороту водительского удостоверения.

Например, в соответствии с Положением ЦБ РФ, актами МИД и МВД РФ, исключено проведение любых банковских операций по водительскому удостоверению.

Документы, не удостоверяющие личность

Не являются удостоверением личности любые документы, выдаваемые в связи с профессиональной или иной деятельностью гражданина, например:

Не могут служить удостоверением личности также:

Назначение кодов

Перечень кодов документов содержится в приказе MMВ-7-6/25@ от 25 января 2012 года. Назначение кодов состоит в регламентации учета видов документов, используемых для заполнения различных заявлений в налоговые службы.

Источник

Основные документы, удостоверяющие личность: возможные планы по систематизации и единому регулированию

|

| 4zeva / Depositphotos.com |

В Госдуму внесен проект федерального закона «Об основных документах, удостоверяющих личность». Документ разработан депутатом нижней палаты парламента Сергеем Ивановым в целях определения правового статуса основных документов, удостоверяющих личность, и систематизации установленных различными нормативно-правовыми актами документов, удостоверяющих личность россиян в стране и за ее пределами, а также иностранных граждан и лиц без гражданства на территории РФ.

Законопроект 1 закрепляет правовые основы документов, удостоверяющих личность, устанавливает требования к их оформлению, а также регулирует деятельность по изготовлению, выдаче, замене, сдаче, изъятию и уничтожению таких документов.

Остановимся на ключевых моментах инициативы.

Четкая терминология

В ст. 1 проектируемого закона планируется закрепить понятие «документ, удостоверяющий личность». Под таковым будет пониматься материальный объект установленного образца с зафиксированной на нем информацией о персональных данных физического лица, позволяющей установить личность и правовой статус его владельца. Одновременно разъясняется, какие документы будут считаться основными (они выделены в законопроекте из общего перечня документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ на территории России или за ее пределами и документов, удостоверяющих личность иностранного гражданина и лица без гражданства на территории нашей страны). Также терминологический аппарат предусматривает расшифровку понятия «уполномоченные государственные органы» (к ним отнесены органы внутренних дел, органы юстиции, орган в области внешнеполитической деятельности, орган в области транспорта и коммуникаций, осуществляющие в пределах своей компетенции оформление, выдачу, замену, изъятие и уничтожение документов, удостоверяющих личность).

Принципы правового регулирования в сфере документов, удостоверяющих личность

Требования к оформлению, выдаче, замене, сдаче, изъятию и уничтожению документов, удостоверяющих личность, планируется привязать к принципам:

Перечень основных документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ

В проекте сформирован перечень из девяти основных документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ. В их числе:

Оговорено, что иные предусмотренные законодательством документы, удостоверяющие личность гражданина РФ, не являются основными. Хотя в некоторых случаях, прямо прописанных в федеральных законах, к удостоверяющим личность документам могут быть отнесены также водительское удостоверение, военный билет, справка об освобождении из мест лишения свободы и актовая запись о рождении.

Причем возможность совершения гражданско-правовых сделок гражданами РФ связывается с наличием любого из трех документов – удостоверения личности гражданина РФ, паспорта гражданина РФ и свидетельства о рождении, а для иностранцев и лиц без гражданства – только одного (вида на жительство).

Требования к основным документам, удостоверяющим личность гражданина РФ

Проект закона содержит требования, касающиеся не только оформления основных документов, удостоверяющих личность (на русском языке в виде документа на бумажном или пластиковом носителе), но и содержащихся в них данных. Речь идет о минимальном наборе сведений – таких, как: имя полностью (Ф. И. О. и другие части имени при наличии); дата и место рождения; пол; национальная принадлежность (по желанию гражданина); гражданство; фотография; наименование органа, выдавшего документ; номер и серия документа при наличии; дата выдачи документа и дата истечения срока действия документа, если такой установлен; подпись гражданина; иные сведения в случаях, предусмотренных законодательством.

Некоторые новеллы законопроекта

Главной новеллой можно признать введение нового вида документа, удостоверяющего личность гражданина РФ, – удостоверения личности гражданина РФ. Речь идет о документе (исключительно на пластиковом носителе), удостоверяющем личность и подтверждающем гражданство РФ. По замыслу парламентария, удостоверение личности россияне будут получать с 14-летнего возраста сроком на 10 лет. Причем граждане РФ, выезжающие на постоянное место жительство за пределы страны, должны будут сдать удостоверения личности в органы внутренних дел. Иные особенности использования удостоверения личности на пластиковом носителе должно будет установить Правительство РФ (например, пока в законопроекте не уточняется, нужно ли будет получать такое удостоверение на пластиковом носителе гражданам старше указанного возраста).

Согласно законопроекту в паспортах граждан, уклоняющихся от уплаты алиментов, может появиться новая отметка – об обязанности платить алименты.

Особенности выдачи и ограничения на использование основных документов, удостоверяющих личность

Наконец, вводится ряд запретов – например, на принятие в залог документов, удостоверяющих личность, а также на идентификацию физического лица по копиям таких документов.

Отметим, намерение урегулировать статус основных документов, удостоверяющих личность, отдельным федеральным законом было высказано еще при принятии Указа Президента РФ от 13 марта 1997 г. № 232. Так, преамбула документа гласит: «В целях создания необходимых условий для обеспечения конституционных прав и свобод граждан Российской Федерации впредь до принятия соответствующего федерального закона об основном документе, удостоверяющем личность гражданина Российской Федерации на территории Российской Федерации, постановляю». Таким законом может стать рассматриваемый законопроект в случае его одобрения Госдумой, Советом Федерации и подписания Президентом РФ. Если это произойдет, то новые нормы начнут действовать со дня их официального опубликования, за исключением положений об удостоверении личности – их планируется применять начиная с 1 января 2021 года (после утверждения Правительством РФ формы, порядка оформления, выдачи, замены, сдачи, изъятия и уничтожения такого документа).

1 С текстом законопроекта № 845287-7 «Об основных документах, удостоверяющих личность» и материалами к нему можно ознакомиться на официальном сайте Госдумы.

Источник

Как пишется удостоверение личности

(введена Федеральным законом от 24.02.2021 N 22-ФЗ)

(абзац введен Федеральным законом от 01.07.2021 N 274-ФЗ)

2. Заявление о выдаче временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, заявление о замене временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации подаются в территориальный орган федерального органа исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел после завершения процедуры установления личности лица без гражданства в соответствии со статьей 10.1 настоящего Федерального закона.

Временное удостоверение личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации выдается лицу без гражданства в течение десяти рабочих дней со дня подачи им заявления о выдаче временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации или заявления о замене временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации.

Направление лицом, содержащимся в специальном учреждении, заявления о выдаче временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации и выдача временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации такому лицу осуществляются через администрацию специального учреждения.

3. Временное удостоверение личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации выдается лицу без гражданства на десять лет.

Лицо без гражданства не позднее чем за десять рабочих дней до истечения срока действия имеющегося у него временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации обязано обратиться в территориальный орган федерального органа исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел с заявлением о замене временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, а при наличии иных условий, предусмотренных абзацем вторым настоящего пункта, в течение тридцати дней со дня их наступления.

5. Временное удостоверение личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации лицу без гражданства не выдается, а ранее выданное ему временное удостоверение личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации аннулируется при установлении факта сообщения лицом без гражданства заведомо ложных сведений о себе либо представления поддельных или подложных документов при подаче заявления о выдаче временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, при установлении наличия у данного лица гражданства иностранного государства или при установлении государства, готового принять лицо без гражданства, либо в случае, если указанное лицо без гражданства имеет либо получило разрешение на временное проживание или вид на жительство.

При аннулировании временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации в связи с установлением наличия у данного лица гражданства иностранного государства или в связи с установлением государства, готового принять лицо без гражданства, данному лицу в соответствии со статьей 10.1 настоящего Федерального закона выдается справка для следования в дипломатическое представительство соответствующего иностранного государства в Российской Федерации, а в случае аннулирования временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации в связи с установлением факта сообщения лицом без гражданства заведомо ложных сведений о себе либо представления поддельных или подложных документов в отношении данного лица проводится процедура установления личности иностранного гражданина, предусмотренная статьей 10.1 настоящего Федерального закона.

При аннулировании временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации в связи с установлением наличия у данного лица гражданства иностранного государства либо в связи с установлением государства, готового принять лицо без гражданства, федеральный орган исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел или его территориальный орган уведомляет об этом в течение трех рабочих дней уполномоченный федеральный орган исполнительной власти или его территориальный орган, вынесший решение о нежелательности пребывания (проживания) в Российской Федерации и (или) решение о неразрешении въезда в Российскую Федерацию.

В случае, если временное удостоверение личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации аннулировано в связи с установлением наличия у данного лица гражданства иностранного государства либо в связи с установлением государства, готового принять лицо без гражданства, данное лицо обязано выехать из Российской Федерации в течение пятнадцати календарных дней. Иностранный гражданин, не исполнивший такой обязанности, подлежит привлечению к ответственности в соответствии с законодательством Российской Федерации.

6. Лица, указанные в настоящей статье, не могут быть привлечены к административной ответственности за нарушение правил въезда в Российскую Федерацию либо режима пребывания (проживания) в Российской Федерации, незаконное осуществление трудовой деятельности в Российской Федерации или нарушение иммиграционных правил, если такие нарушения были выявлены в связи с подачей данными лицами заявления об установлении личности, предусмотренного статьей 10.1 настоящего Федерального закона, или заявления о выдаче временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации.

7. Форма и описание бланка временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, в том числе в форме карты с электронным носителем информации, являющегося бланком строгой отчетности, порядок выдачи, замены, аннулирования временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, форма заявления о выдаче временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации и форма заявления о замене временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации утверждаются федеральным органом исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел.

(в ред. Федерального закона от 01.07.2021 N 274-ФЗ)

(см. текст в предыдущей редакции)

8. Территориальный орган федерального органа исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел, принявший решение о выдаче лицу, в отношении которого принято решение об административном выдворении за пределы Российской Федерации, временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, в течение трех рабочих дней со дня принятия такого решения уведомляет об этом с приложением копии такого решения орган прокуратуры в целях опротестования постановления суда об административном выдворении за пределы Российской Федерации, а также территориальный орган федерального органа исполнительной власти, уполномоченного на осуществление функций по обеспечению установленного порядка деятельности судов, исполнению судебных актов, актов иных органов, и должностных лиц.

Территориальный орган федерального органа исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел, принявший решение о выдаче лицу, в отношении которого принято решение о депортации, временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, в течение трех рабочих дней со дня принятия такого решения уведомляет об этом с приложением копии такого решения федеральный орган исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел или его территориальный орган, принявший решение о депортации данного лица, в целях отмены решения о депортации.

Территориальный орган федерального органа исполнительной власти в сфере внутренних дел, принявший решение о выдаче лицу, в отношении которого принято решение о нежелательности пребывания (проживания) в Российской Федерации или решение о неразрешении въезда в Российскую Федерацию, временного удостоверения личности лица без гражданства в Российской Федерации, в течение трех рабочих дней со дня принятия соответствующего решения уведомляет об этом с приложением копии соответствующего решения федеральный орган исполнительной власти или его территориальный орган, принявший решение о нежелательности пребывания (проживания) в Российской Федерации или решение о неразрешении въезда в Российскую Федерацию, в целях отмены соответствующего решения.

Источник

Документы, удостоверяющие личность: перечень

История появления

Взаимодействие гражданина с различными организациями неразрывно связано с необходимостью предоставить документы, подтверждающие личность. Это правило обязательно для исполнения для всех учреждений, в особенности тех, где операции имеют финансовый характер.

Необходимость персонифицирования личности человека возникла еще во время Киевской Руси. Правда, в те времена это были далеко не те документы, которые мы привыкли видеть сегодня, да и степень их подлинности ничем не защищалась. Например, для определения личности использовалась вышивка с определенными орнаментами на поясе. Более объемные опознавательные знаки располагались на фамильных гербах и флагах.

Какие документы удостоверяют личность?

Широкое распространение паспорта, как документа, удостоверяющего личность, пришлось на времена начала грандиозного строительства Санкт-Петербурга и крупных заводов на Урале. Для этого требовалось большое количество рабочей силы, которая прибывала из других стран. Нахождение рабочих на русской земле и свободное перемещение было возможным только благодаря наличию специального «прокормежного письма» или «пропускного». В этом документе описывались главные приметы его обладателя.

На сегодняшний день перечень документов, удостоверяющих личность, имеет вполне определенную классификацию, четко ограниченный функционал, способ получения и срок действия:

Для детей

Для получения свидетельства необходима справка из родильного дома, подтверждающая факт рождения ребенка, заявление, паспорта обоих родителей, свидетельство о браке предъявляется при его наличии. Как правило, специалисты готовят документ в день обращения заявителя. Предъявлять данный документ, удостоверяющий личность гражданина РФ, можно только до получения им паспорта общероссийского образца. На основании него ребенку предоставляются услуги по медицинскому обслуживанию, регистрация по месту жительства, принимается заявление на поступление в дошкольное учреждение и начальную школу и т. д.

Для тех, кому исполнилось 14 лет

Третья страница паспорта имеет специальное покрытие прозрачной пленкой с нанесенным изображением российского герба и буквенного символа «РФ». Документ поделен на разделы: место жительства, отношение к воинской службе, семейное положение, отметки о детях. Они заполняются по факту внесения изменений, например, при регистрации брака, рождении детей и прочее. Все страницы паспорта, кроме 2 и 3, имеют перфорацию серии и номера для слабовидящих.

Получить главное удостоверение личности гражданина РФ можно не ранее 14 лет. Далее он меняется в 20 и потом в 45 лет. Те, кто вносит изменение в части фамилии, имени, отчества или при утере паспорта, повреждении страниц, обязаны произвести своевременную замену документа. На время его отсутствия можно получить временное удостоверение личности по форме 2-п. В нем содержатся персональные сведения, в том числе относительно даты рождения владельца паспорта, его регистрационный номер, данные об утерянном или ранее заменяемом документе, месте регистрации гражданина. Бланк защищен гербовой печатью и подписью уполномоченного лица, имеет ограничение по сроку действия, который указан на лицевой стороне бланка. Не допускается использование нотариально заверенной копии паспорта взамен оригинала.

Для выезжающих за рубеж

Покидая территорию Российской Федерации, любой гражданин, независимо от возраста, должен иметь соответствующий документ, который подтверждает его личность. Если со взрослыми туристами все более-менее понятно, то большинство родителей, впервые столкнувшихся с необходимостью пересечь границу с детьми, задаются вопросом, а какие документы являются удостоверением личности для них? Одного свидетельства о рождении может оказаться недостаточно. Вдобавок ко всему пограничники потребуют, чтобы в паспорте родителя имелась отметка о ребенке. Если его сопровождают взрослые, не являющиеся родителями, то необходимо подготовить заранее доверенность.

Наличие отдельного паспорта для выезда за границу РФ обязательно для всех лиц старше 14 лет. На сегодняшний день такой документ можно получить либо старого, либо нового образца. Их отличие в:

Документ может предоставляться в организациях, расположенных на территории РФ, в качестве второго документа. Если говорить о банках, то они принимают его вместо паспорта, только если данные о нем уже заведены в базу. Поэтому стоит заранее уточнить, можно ли его предъявить в качестве удостоверения личности в той или иной организации, куда планирует обратиться гражданин.

Для военнослужащих

Дипломатические документы

К числу лиц, допущенных к оформлению дипломатического паспорта, относятся также члены их семьи. Использовать данный документ разрешается только в рамках служебной командировке, после прибытия его необходимо сдать.

Для моряков

Начиная с 01 декабря 1997 года, на основании Постановления правительства РФ № 1508, все служащие на военно-морском флоте в качестве документа, удостоверяющего личность в РФ, предъявляет удостоверение личности моряка. Он необходим не только во время прохождения воинской службы, но и в период нахождения в командировке российскими владельцами судов на иностранных кораблях.

Для иностранцев

Предоставление паспорта иностранного государства возможно в качестве документа, удостоверяющего личность заявителя в судах, в федеральных или региональных бюджетных учреждениях и т. д. То есть на основании него гражданин может находиться на территории России только в течение времени, указанного в визе. По истечении ее срока действия, он обязан покинуть страну. При этом нельзя продлить визу, находясь на территории РФ.

Тем, кто остался без гражданства

При признании гражданина беженцем выдается удостоверение или свидетельство о рассмотрении соответствующего ходатайства. Регулируется данное положение нормами федерального закона РФ, где конкретно прописан список документов, удостоверяющих личность беженцев, и как их можно оформить.

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как пишется удостоверение личности, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как пишется удостоверение личности», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

- удостоверяющий личность документ,

Существительное

мн. удостоверяющие личность документы

Склонение существительного удостоверяющий личность документм.р.,

Единственное число

Множественное число

Единственное число

Именительный падеж

(Кто? Что?)

удостоверяющий личность документ

удостоверяющие личность документы

Родительный падеж

(Кого? Чего?)

удостоверяющего личность документа

удостоверяющих личность документов

Дательный падеж

(Кому? Чему?)

удостоверяющему личность документу

удостоверяющим личность документам

Винительный падеж

(Кого? Что?)

удостоверяющий личность документ

удостоверяющие личность документы

Творительный падеж

(Кем? Чем?)

удостоверяющим личность документом

удостоверяющими личность документами

Предложный падеж

(О ком? О чем?)

удостоверяющем личность документе

удостоверяющих личность документах

Множественное число

удостоверяющие личность документы

удостоверяющих личность документов

удостоверяющим личность документам

удостоверяющие личность документы

удостоверяющими личность документами

удостоверяющих личность документах

| Код | Наименование документа |

|---|---|

| 03 | Свидетельство о рождении |

| 07 | Военный билет |

| 08 | Временное удостоверение, выданное взамен военного билета |

| 10 | Паспорт иностранного гражданина |

| 11 | Свидетельство о рассмотрении ходатайства о признании лица беженцем на территории РФ по существу |

| 12 | Вид на жительство в РФ |

| 13 | Удостоверение беженца |

| 14 | Временное удостоверение личности гражданина РФ |

| 15 | Разрешение на временное проживание в РФ |

| 19 | Свидетельство о предоставлении временного убежища на территории РФ |

| 21 | Паспорт гражданина РФ |

| 22 | Загранпаспорт гражданина РФ |

| 23 | Свидетельство о рождении, выданное уполномоченным органом иностранного государства |

| 24 | Удостоверение личности военнослужащего РФ |

| 27 | Военный билет офицера запаса |

| 91 | Иные документы* |

Буквенное обозначение, требуемое для некоторых документов приведено в таблице ниже:

| Наименование документа | Код |

|---|---|

| Паспорт гражданина Российской Федерации | ПАСПОРТ РОССИИ |

| Паспорт гражданина СССР | ПАСПОРТ |

| Загранпаспорт гражданина Российской Федерации | ЗГПАСПОРТ РФ |

| Свидетельство о рождении | СВИД О РОЖД |

| Удостоверение личности офицера (военнослужащего) | УДОСТ ОФИЦЕРА |

| Справка об освобождении из места лишения свободы | СПРАВКА ОБ ОСВ |

| Военный билет солдата (матроса, сержанта, старшины) | ВОЕННЫЙ БИЛЕТ |

| Дипломатический паспорт гражданина Российской Федерации | ДИППАСПОРТ РФ |

| Служебный паспорт | СЛУЖ ПАСПОРТ |

| Паспорт иностранного гражданина | ИНПАСПОРТ |

| Свидетельство о регистрации ходатайства о признании иммигранта беженцем по существу | СВИД БЕЖЕНЦА |

| Вид на жительство | ВИД НА ЖИТЕЛЬ |

| Удостоверение беженца в Российской Федерации | УДОСТ БЕЖЕНЦА |

| Временное удостоверение личности гражданина Российской Федерации (форма № 2П) | ВРЕМ УДОСТ |

| Удостоверение личности моряка, паспорт моряка | ПАСПОРТ МОРЯКА |

| Военный билет офицера запаса | ВОЕН БИЛЕТ ОЗ |

| Иные документы, выдаваемые органами МВД России | ПРОЧЕЕ |

Существует целый ряд нормативных актов, в той или иной степени регламентирующих виды и юридическую значимость как документов, удостоверяющих личность, так и их коды.

Нормативное регулирование

Список документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ, в разных вариациях представлен в нескольких нормативных актах, а именно:

- в Законе РФ «Об основных гарантиях избирательных прав и права на участие в референдуме граждан РФ»;

- в Законе РФ «О порядке выезда из РФ и въезда в Российскую Федерацию»

- в Указе № 1325 Президента РФ от 14 ноября 2002 «Об утверждении Положения о порядке рассмотрения вопросов гражданства Российской Федерации»;

- в Законе РФ «Об актах гражданского состояния»;

- в Приказе № 524 Минпромторга РФ от 15 апреля 2011.

Если проанализировать все вышеперечисленные акты и свести представленные в них перечни документов, то список документов, удостоверяющих личность, можно подразделить на две группы – документов гражданина РФ и документов иностранного гражданина, пребывающего или въезжающего на территорию РФ.

Так, перечень документов, удостоверяющих личность гражданина РФ, будет примерно следующим:

- внутренний паспорт, в том числе и паспорт гражданина РФ для граждан, проживающих за пределами РФ;

- свидетельство о рождении;

- общегражданский заграничный паспорт;

- дипломатический паспорт;

- служебный паспорт;

- военный билет и временное удостоверение для лиц, проходящих военную службу;

- специальная форма, выдаваемая вместо паспорта на период времени, необходимый для оформления паспорта;

- паспорт моряка;

- справка осужденного, подозреваемого или обвиняемого, выдаваемая взамен изъятого паспорта.

Перечень документов, удостоверяющих личность иностранных граждан, находящихся или въезжающих на территорию РФ, включает в себя:

- внутренний или международный паспорт иностранца (в зависимости от пограничного режима с тем или иным государством);

- вид на жительство в РФ;

- удостоверение на временное проживание;

- удостоверение о предоставленном в РФ статусе беженца либо свидетельство о предоставлении убежища на территории Российской Федерации.

Как видно из списка, перечень документов достаточно разнообразен, причем каждый документ из перечня в той или иной степени зависит от вида правоотношений, для которых он создан.

Например, заграничный паспорт имеет цель удостоверения личности гражданина РФ за рубежом и при пересечении государственной границы, а паспорт моряка служит для документального обеспечения граждан РФ, находящихся в плавании.

То есть тот же заграничный паспорт или временная справка или паспорт моряка служат разным целям и при этом являются частичными эквивалентами основного внутригосударственного документа, а именно, внутреннего паспорта гражданина РФ.

Где применяются двухзначные и буквенные коды

Двухзначный код вида документа используется к примеру в таких формах как:

- справка о доходах и суммах налога физического лица 2-НДФЛ;

- налоговая декларация по форме 3-НДФЛ;

- отчет о движении средств физического лица — резидента по счету (вкладу) в банке за пределами территории РФ;

- декларация по водному налогу.

Буквенный код используется в формах для регистрации в системе обязательного пенсионного страхования, например в:

- анкете застрахованного лица в ПФР АДВ-1;

- заявлении об обмене страхового свидетельства АДВ-2;

- запросе об уточнении сведений АДИ-2.

Основные документы и требования к ним

В настоящее время на территории РФ действуют следующие формы единого основного документа – паспорта гражданина РФ:

- паспорт образца 1997 года, установленный Указом 232 Президента Российской Федерации;

- паспорт с гражданством СССР, выданный в установленном законом порядке в период существования СССР, который, хотя и подлежит замене, но является полноценным эквивалентом паспорта образца 1997 года. Дело в том, что Закон о гражданстве РФ не предусматривает ограничения срока действия паспорта в зависимости от его формы;

- паспорт гражданина РФ, выданный в установленном законом порядке и действовавший до 1.07.2002 года.

Следует уточнить, что действительность паспорта, вне зависимости от его формы, зависит от двух факторов, а именно:

- отсутствия не предусмотренных законом записей или отметок в паспорте;

- степени сохранности и читаемости паспорта.

Поврежденный паспорт, а равно паспорт, содержащий в себе неустановленные записи, будет считаться недействительным.

Приравнены на определенный срок по юридической значимости к паспорту гражданина РФ:

- удостоверение личности моряка. Так, паспорт моряка в равной степени действителен в пределах РФ и приравнен к заграничному паспорту за рубежом в соответствии с Постановлением № 628 Правительства РФ от 18.08.2008 года;

- свидетельство о рождении для детей в возрасте до 14 лет, в соответствии с Законом РФ «Об актах гражданского состояния»;

- военное удостоверение личности для офицеров, прапорщиков и мичманов флота, находящихся на воинской службе;

- военный билет, выдаваемый солдатам, сержантам и старшинам срочной службы или служащим по контракту;

- справки формы № 2П, выдаваемые на период оформления паспорта.

Документы иностранцев

Иностранные граждане, находящиеся или въезжающие на территорию РФ, должны обладать один из следующих документов:

- паспортом международного образца своей страны. Для граждан государств, имеющих с РФ упрощенный режим пересечения границ, достаточно внутреннего паспорта;

- дипломатическим паспортом международного образца, если деятельность иностранного гражданина связана с дипломатическим или консульским представительством;

- паспортом гражданина СССР в случае, если иностранец является гражданином одной из республик бывшего СССР и законно проживает на территории РФ;

- разрешением на временное проживание на территории РФ;

- видом на жительство в РФ;

- удостоверением о присвоенном статусе беженца или о предоставлении убежища на территории РФ.

Является ли заграничный паспорт документом, удостоверяющим личность

Паспорт международного образца, выдаваемый гражданам РФ для поездок за рубеж, хотя и признан удостоверением личности, не является эквивалентом внутреннего паспорта, а потому обладает некоторыми ограничениями в гражданском обороте.

Ограничения обусловлены тем, что заграничный паспорт предназначен удостоверять личность гражданина РФ за рубежом, а потому не может быть эквивалентом внутригосударственного паспорта.

Является ли водительское удостоверение документом, удостоверяющим личность

Чисто юридически водительское удостоверение является лишь документом, подтверждающим право его обладателя управлять транспортным средством.

Однако, в соответствии с Постановлением ГКПИ 06-1016 ВС РФ, водительское удостоверение имеет двоякую функцию, а именно:

- подтверждение права управления ТС;

- подтверждение личности владельца водительского удостоверения.

Однако существует ряд ведомственных ограничений по гражданскому обороту водительского удостоверения.

Например, в соответствии с Положением ЦБ РФ, актами МИД и МВД РФ, исключено проведение любых банковских операций по водительскому удостоверению.

Документы, не удостоверяющие личность

Не являются удостоверением личности любые документы, выдаваемые в связи с профессиональной или иной деятельностью гражданина, например:

- студенческие билеты и зачётные книжки;

- пенсионные удостоверения, справки об инвалидности, удостоверения ветерана, инвалида, почётного донора;

- трудовые книжки;

- загранпаспорта;

- свидетельства о браке и о расторжении брака;

- профессиональные удостоверения, например, удостоверения адвоката, работника ФСБ, полиции, госслужащего или члена РАН.

Не могут служить удостоверением личности также:

- копии паспортов, в том числе и заверенные нотариально;

- справки об освобождении. Предел их действия – это предоставление в паспортный стол для получения основного документа.

Назначение кодов

Перечень кодов документов содержится в приказе MMВ-7-6/25@ от 25 января 2012 года. Назначение кодов состоит в регламентации учета видов документов, используемых для заполнения различных заявлений в налоговые службы.

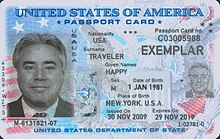

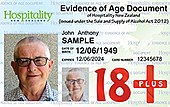

An identity document (also called ID or colloquially as papers) is any document that may be used to prove a person’s identity. If issued in a small, standard credit card size form, it is usually called an identity card (IC, ID card, citizen card),[a] or passport card.[b] Some countries issue formal identity documents, as national identification cards that may be compulsory or non-compulsory, while others may require identity verification using regional identification or informal documents. When the identity document incorporates a person’s photograph, it may be called photo ID.[1]

In the absence of a formal identity document, a driver’s license may be accepted in many countries for identity verification. Some countries do not accept driver’s licenses for identification, often because in those countries they do not expire as documents and can be old or easily forged. Most countries accept passports as a form of identification.

Some countries require all people to have an identity document available at all times. Many countries require all foreigners to have a passport or occasionally a national identity card from their home country available at any time if they do not have a residence permit in the country.

The identity document is used to connect a person to information about the person, often in a database. The connection between the identity document and database is based on personal information present on the document, such as the bearer’s full name, age, birth date, address, an identification number, card number, gender, citizenship and more. A unique national identification number is the most secure way, but some countries lack such numbers or don’t show them on identity documents.

History

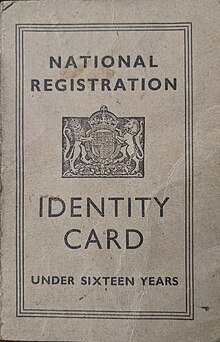

A version of the passport considered to be the earliest identity document inscribed into law was introduced by King Henry V of England with the Safe Conducts Act 1414.[2]

For the next 500 years up to the onset of the First World War, most people did not have or need an identity document.

Photographic identification appeared in 1876[3] but it did not become widely used until the early 20th century when photographs became part of passports and other ID documents, all of which came to be referred to as «photo IDs» in the late 20th century. Both Australia and Great Britain, for example, introduced the requirement for a photographic passport in 1915 after the so-called Lody spy scandal.[4]

The shape and size of identity cards were standardized in 1985 by ISO/IEC 7810. Some modern identity documents are smart cards that include a difficult-to-forge embedded integrated circuit standardized in 1988 by ISO/IEC 7816. New technologies allow identity cards to contain biometric information, such as a photograph, face; hand, or iris measurements; or fingerprints. Many countries issue electronic identity cards.

Adoption

Law enforcement officials claim that identity cards make surveillance and the search for criminals easier and therefore support the universal adoption of identity cards. In countries that don’t have a national identity card, there is concern about the projected costs and potential abuse of high-tech smartcards.

In many countries – especially English-speaking countries such as Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States – there are no government-issued compulsory identity cards for all citizens. Ireland’s Public Services Card is not considered a national identity card by the Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection (DEASP),[5] but many say it is in fact becoming that, and without public debate or even a legislative foundation.[6]

There is debate in these countries about whether such cards and their centralised databases constitute an infringement of privacy and civil liberties. Most criticism is directed towards the possibility of abuse of centralised databases storing sensitive data. A 2006 survey of UK Open University students concluded that the planned compulsory identity card under the Identity Cards Act 2006 coupled with a central government database generated the most negative response among several options. None of the countries listed above mandate identity documents, but they have de facto equivalents since these countries still require proof of identity in many situations. For example, all vehicle drivers must have a driving licence, and young people may need to use specially issued «proof of age cards» when purchasing alcohol.

Arguments for

Arguments for identity documents as such:

- In order to avoid mismatching people and to fight fraud, there should be a secure way to prove a person’s identity.

- Every human being already carries their own personal identification in the form of DNA, which is extremely hard to falsify or to discard (in terms of modification). Even for non-state commercial and private interactions, this may shortly become the preferred identifier, rendering a state-issued identity card a lesser evil than the potentially extensive privacy risks associated with everyday use of a person’s genetic profile for identification purposes.[1][7][8][9][10]

Arguments for national identity documents:

- If using only private alternatives, such as ID cards issued by banks, the inherent lack of consistency regarding issuance policies can lead to downstream problems. For example, in Sweden private companies such as banks (citing security reasons) refused to issue ID cards to individuals without a Swedish card or Swedish passport. This forced the government to start issuing national cards. It is also harder to control information usage by private companies, such as when credit card issuers or social media companies map purchase behaviour in order to assist ad targeting.

Arguments against

Arguments against identity documents as such:

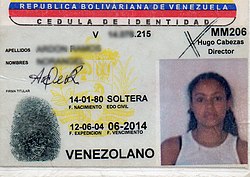

- The development and administrative costs of an identity card system can be high. Figures from £30 to £90 or even higher were suggested for the abandoned UK ID card. In countries such as Chile the identity card is paid for by each person up to £6; in other countries, such as France or Venezuela, the ID card is free.[11][12] This, however, does not disclose the true cost of issuing ID cards as some additional portion may be borne by taxpayers in general.

Arguments against national identity documents:

- Rather than relying on government-issued ID cards, U.S. federal policy has encouraged a variety of identification systems that already exist, such as driver’s or firearms licences or private cards.

Arguments against overuse or abuse of identity documents:

- Cards reliant on a centralized database can be used to track someone’s physical movements and private life, thus infringing on personal freedom and privacy. The proposed British ID card proposes a series of linked databases managed by private sector firms. The management of disparate linked systems across a range of institutions and any number of personnel is alleged to be a security disaster in the making.[13]

- If race is displayed on mandatory ID documents, this information can lead to racial profiling.

National policies

Compulsory ID cards

Non-compulsory ID cards

According to Privacy International, as of 1996, possession of identity cards was compulsory in about 100 countries, though what constitutes «compulsory» varies. In some countries (see below), it is compulsory to have an identity card when a person reaches a prescribed age. The penalty for non-possession is usually a fine, but in some cases it may result in detention until identity is established. For people suspected with crimes such as shoplifting or no bus ticket, non-possession might result in such detention, also in countries not formally requiring identity cards. In practice, random checks are rare, except in certain times.

A number of countries do not have national identity cards. These include Andorra,[14] Australia, the Bahamas,[15] Canada, Denmark, India (see below), Japan (see below), Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Palau, Samoa, Turkmenistan,[16] Tuvalu, and the United Kingdom. Other identity documents such as passports or driver’s licenses are then used as identity documents when needed. However, governments of Kiribati and Samoa are planning to introduce new national identity cards in the near future[17][18][19] Some of these, e.g. Denmark, have more simple official identity cards, which do not match the security and level of acceptance of a national identity card, used by people without driver’s licenses.

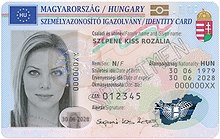

A number of countries have voluntary identity card schemes. These include Austria, Belize, Finland, France (see France section), Hungary (however, all citizens of Hungary must have at least one of: valid passport, photo-based driving licence, or the National ID card), Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Saint Lucia, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States. The United Kingdom’s scheme was scrapped in January 2011 and the database was destroyed.

In the United States, the Federal government issues optional identity cards known as «Passport Cards» (which include important information such as the nationality). On the other hand, states issue optional identity cards for people who do not hold a driver’s license as an alternate means of identification. These cards are issued by the same organisation responsible for driver’s licenses, usually called the Department of Motor Vehicles. Passport Cards hold limited travel status or provision, usually for domestic travel requirements. Note, this is not an obligatory identification card for citizens.

For the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara, pre-1975 Spanish identity cards are the main proof that they were Saharawi citizens as opposed to recent Moroccan colonists. They would thus be allowed to vote in an eventual self-determination referendum.

Companies and government departments may issue ID cards for security purposes, proof of identity, or proof of a qualification. For example, all taxicab drivers in the UK carry ID cards. Managers, supervisors, and operatives in construction in the UK have a photographic ID[20] card, the CSCS (Construction Skills Certification Scheme) card, indicating training and skills including safety training. Those working on UK railway lands near working lines must carry a photographic ID card to indicate training in track safety (PTS and other cards) possession of which is dependent on periodic and random alcohol and drug screening. In Queensland and Western Australia, anyone working with children has to take a background check and get issued a Blue Card or Working with Children Card, respectively.

Africa

Liberia

Liberia has begun the issuance process of its national biometric identification card, which citizens and foreign residents will use to open bank accounts and participate in other government services on a daily basis.

More than 4.5 million people are expected to register and obtain ID cards of citizenship or residence in Liberia. The project has already started where NIR (National Identification Registry) is issuing Citizen National ID Cards. The centralized National Biometric Identification System (NBIS) will be integrated with other government ministries. Resident ID Cards and ECOWAS ID Cards will also be issued.[21]

Cape Verde

Cartão Nacional de Identificação (CNI) is the national identity card of Cape Verde.

Egypt

It is compulsory for all Egyptian citizens age 16 or older to possess an ID card [22] (Arabic: بطاقة تحقيق شخصية Biṭāqat taḥqīq shakhṣiyya, literally, «Personal Verification Card»).[citation needed] In daily colloquial speech, it is generally simply called «el-biṭāqa» («the card»). It is used for:[citation needed]

- Opening or closing a bank account

- Registering at a school or university

- Registering the number of a mobile or landline telephone

- Interacting with most government agencies, including:

- Applying for or renewing a driver’s license

- Applying for a passport

- Applying for any social services or grants

- Registering to vote, and voting in elections

- Registering as a taxpayer

Egyptian ID cards consist of 14 digits, the national identity number, and expire after 7 years from the date of issue. Some feel that Egyptian ID cards are problematic, due to the general poor quality of card holders’ photographs and the compulsory requirements for ID card holders to identify their religion and for married women to include their husband’s name on their cards.[citation needed]

The Tunisian identity card

Tunisia

Every citizen of Tunisia is expected to apply for an ID card by the age of 18; however, with the approval of a parent(s), a Tunisian citizen may apply for, and receive, an ID card prior to their eighteenth birthday upon parental request.[citation needed]

In 2016, The government has introduced a new bill to the parliament to issue new biometric ID documents. The bill has created controversy amid civil society organizations.[23]

The Gambia

All Gambian citizens over 18 years of age are required to hold a Gambian National Identity Card.[citation needed] In July 2009, a new biometric identity card was introduced.[citation needed] The biometric card is one of the acceptable documents required to apply for a Gambian Driving Licence.[citation needed]

Ghana

Ghana begun the issueing of a national identity card for Ghanaian citizens in 1973.[24]

However, the project was discontinued three years later due to problems with logistics and lack of financial support. This was the first time the idea of national identification systems in the form of the Ghana Card arose in the country.[24] Full implementation of the Ghana Cards begun from 2006.[25]

According to the National Identification Authority, over 15 million Ghanaians have been registered for the Ghana card by September 2020.[26]

Mauritius

Mauritius requires all citizens who have reached the age of 18 to apply for a National Identity Card. The National Identity Card is one of the few accepted forms of identification, along with passports. A National Identity Card is needed to apply for a passport for all adults, and all minors must take with them the National Identity Card of a parent(s) when applying for a passport.[27]

Mozambique

Bilhete de identidade (BI) is the national ID card of Mozambique.

Nigeria

Nigeria first introduced a national identity card in 2005, but its adoption back then was limited and not widespread.

The country is now in the process of introducing a new biometric ID card complete with a SmartCard and other security features. The National Identity Management Commission (NIMC)[28] is the federal government agency responsible for the issuance of these new cards, as well as the management of the new National Identity Database.

The Federal Government of Nigeria announced in April 2013[29] that after the next general election in 2015, all subsequent elections will require that voters will only be eligible to stand for office or vote provided the citizen possesses a NIMC-issued identity card.

The Central Bank of Nigeria is also looking into instructing banks to request for a National Identity Number (NIN) for any citizen maintaining an account with any of the banks operating in Nigeria. The proposed kick off date is yet to be determined.

South Africa

The reverse of the South African Smart ID

South African citizens aged 15 years and 6 months or older are eligible for an ID card. The South African identity document is not valid as a travel document or valid for use outside South Africa. Although carrying the document is not required in daily life, it is necessary to show the document or a certified copy as proof of identity when:

- Signing a contract, including

- Opening or closing a bank account

- Registering at a school or university

- Buying a mobile phone and registering the number

- Interacting with most government agencies, including

- Applying for or renewing a driving licence or firearm licence

- Applying for a passport

- Applying for any social services or grants

- Registering to vote, and voting in elections

- Registering as a taxpayer or for unemployment insurance

The South African identity document used to also contain driving and firearms licences; however, these documents are now issued separately in card format.

In mid 2013 a smart card ID was launched to replace the ID book. The cards were launched on July 18, 2013, when a number of dignitaries received the first cards at a ceremony in Pretoria.[30] The government plans to have the ID books phased out over a six to eight-year period.[31] The South African government is looking into possibly using this smart card not just as an identification card but also for licences, National Health Insurance, and social grants.[32]

Zimbabwe

Zimbabweans are required to apply for National Registration at the age of 16.[citation needed] Zimbabwean citizens are issued with a plastic card which contains a photograph and their particulars onto it. Before the introduction of the plastic card, the Zimbabwean ID card used to be printed on anodised aluminium. Along with Driving Licences, the National Registration Card (including the old metal type) is universally accepted as proof of identity in Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans are required by law to carry identification on them at all times and visitors to Zimbabwe are expected to carry their passport with them at all times.[citation needed]

Asia

Afghanistan

Afghan citizens over the age of 18 are required to carry a national ID document called Tazkira.

Bahrain

Bahraini citizens must have both an ID card, called a «smart card», which is recognized as an official document and can be used within the Gulf Cooperation Council, and a passport, which is recognized worldwide.[citation needed]

Bangladesh

Biometric identification has existed in Bangladesh since 2008. All Bangladeshis who are 18 years of age and older are included in a central Biometric Database, which is used by the Bangladesh Election Commission to oversee the electoral procedure in Bangladesh. All Bangladeshis are issued with an NID Card which can be used to obtain a passport, Driving Licence, credit card, and to register land ownership.

Bhutan

The Bhutanese national identity card (called the Buthanese Citizenship card) is an electronic ID card, compulsory for all Bhutanese nationals and costs 100 Bhutanese ngultrum.

China

Chinese second generation ID card

The People’s Republic of China requires each of its citizens aged 16 and over to carry an identity card. The card is the only acceptable legal document to obtain employment, a residence permit, driving licence or passport, and to open bank accounts or apply for entry to tertiary education and technical colleges.

Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Identity Card (or HKID) is an official identity document issued by the Immigration Department of Hong Kong to all people who hold the right of abode, right to land or other forms of limited stay longer than 180 days in Hong Kong. According to Basic Law of Hong Kong, all permanent residents are eligible to obtain the Hong Kong Permanent Identity Card which states that the holder has the right of abode in Hong Kong. All persons aged 16 and above must carry a valid legal government identification document in public. All persons aged 16 and above must be able to produce valid legal government identification documents when requested by legal authorities; otherwise, they may be held in detention to investigate his or her identity and legal right to be in Hong Kong.

India

While there is no mandatory identity card in India, the Aadhaar card, a multi-purpose national identity card, carrying 16 personal details and a unique identification number, has been available to all citizens since 2007. The card contains a photograph, full name, date of birth, and a unique, randomly generated 12-digit National Identification Number. However, the card itself is rarely required as proof, the number or a copy of the card being sufficient. The card has a SCOSTA QR code embedded on the card, through which all the details on the card are accessible.[33] In addition to Aadhaar, PAN cards, ration cards, voter cards and driving licences are also used. These may be issued by either the government of India or the government of any state, and are valid throughout the nation. The Indian passport may also be used.

Indonesia

Indonesian national identity card

Residents over 17 are required to hold a KTP (Kartu Tanda Penduduk) identity card. The card will identify whether the holder is an Indonesian citizen or foreign national. In 2011, the Indonesian government started a two-year ID issuance campaign that utilizes smartcard technology and biometric duplication of fingerprint and iris recognition. This card, called the Electronic KTP (e-KTP), will replace the conventional ID card beginning in 2013. By 2013, it is estimated that approximately 172 million Indonesian nationals will have an e-KTP issued to them.

Iran

Every citizen of Iran has an identification document called Shenasnameh (Iranian identity booklet) in Persian (شناسنامه). This is a booklet based on the citizen’s birth certificate which features their Shenasnameh National ID number, given name, surname, their birth date, their birthplace, and the names, birth dates and National ID numbers of their legal ascendants. In other pages of the Shenasnameh, their marriage status, names of spouse(s), names of children, date of every vote cast and eventually their death would be recorded.[34]

Every Iranian permanent resident above the age of 15 must hold a valid National Identity Card (Persian:کارت ملی) or at least obtain their unique National Number from any of the local Vital Records branches of the Iranian Ministry of Interior.[35]

In order to apply for an NID card, the applicant must be at least 15 years old and have a photograph attached to their Birth Certificate, which is undertaken by the Vital Records branch.

Since June 21, 2008, NID cards have been compulsory for many things in Iran and Iranian missions abroad (e.g., obtaining a passport, driver’s license, any banking procedure, etc.).[36]

Iraq

Every Iraqi citizen must have a National Card (البطاقة الوطنية).

Israel

Israeli biometric national identity card

Israeli law requires every permanent resident above the age of 16, whether a citizen or not, to carry an identification card called te’udat zehut (Hebrew: תעודת זהות) in Hebrew or biţāqat huwīya (بطاقة هوية) in Arabic.

The card is designed in a bilingual form, printed in Hebrew and Arabic; however, the personal data is presented in Hebrew by default and may be presented in Arabic as well if the owner decides so. The card must be presented to an official on duty (e.g., a policeman) upon request, but if the resident is unable to do this, one may contact the relevant authority within five days to avoid a penalty.

Until the mid-1990s, the identification card was considered the only legally reliable document for many actions such as voting or opening a bank account. Since then, the new Israeli driver’s licenses which include photos and extra personal information are now considered equally reliable for most of these transactions. In other situations any government-issued photo ID, such as a passport or a military ID, may suffice.

Japan

Japanese citizens are not required to have identification documents with them within the territory of Japan. When necessary, official documents, such as one’s Japanese driver’s license, basic resident registration card,[37] radio operator license,[38] social insurance card, health insurance card or passport are generally used and accepted. On the other hand, mid- to long-term foreign residents are required to carry their Zairyū cards,[39] while short-term visitors and tourists (those with a Temporary Visitor status sticker in their passport) are required to carry their passports.

Kuwait

Front and reverse of the Kuwaiti national identity card

The Kuwaiti identity card is issued to Kuwaiti citizens. It can be used as a travel document when visiting countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Macau

Front of the Macau identity card

Reverse of the Macau identity card

The Macau Resident Identity Card is an official identity document issued by the Identification Department to permanent residents and non-permanent residents.

Malaysia

In Malaysia, the MyKad is the compulsory identity document for Malaysian citizens aged 12 and above. Introduced by the National Registration Department of Malaysia on September 5, 2001, as one of four MSC Malaysia flagship applications[40] and a replacement for the High Quality Identity Card (Kad Pengenalan Bermutu Tinggi), Malaysia became the first country in the world to use an identification card that incorporates both photo identification and fingerprint biometric data on an in-built computer chip embedded in a piece of plastic.[41]

Myanmar

Myanmar citizens are required to obtain a National Registration Card (NRC), while non-citizens are given a Foreign Registration Card (FRC).

Nepal

New biometric cards rolled out in 2018. Information displayed in both English and Nepali.[42][43]

Pakistan

In Pakistan, all adult citizens must register for the Computerized National Identity Card (CNIC), with a unique number, at age 18. CNIC serves as an identification document to authenticate an individual’s identity as a citizen of Pakistan.

Earlier on, National Identity Cards (NICs) were issued to citizens of Pakistan. Now, the government has shifted all its existing records of National Identity Cards (NIC) to the central computerized database managed by NADRA.

New CNIC’s are machine readable and have security features such as facial and finger print information. At the end of 2013, smart national identity cards, SNICs, were also made available.

Palestine

The Palestinian Authority issues identification cards following agreements with Israel. Since 1995, in accordance to the Oslo Accords, the data is forwarded to Israeli databases and verified.[citation needed] In February 2014, a presidential decision issued by Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas to abolish the religion field was announced.[44] Israel has objected to abolishing religion on Palestinian IDs because it controls their official records, IDs and passports and the PA does not have the right to make amendments to this effect without the prior approval of Israel. The Palestinian Authority in Ramallah said that abolishing religion on the ID has been at the center of negotiations with Israel since 1995. The decision was criticized by Hamas officials in Gaza Strip, saying it is unconstitutional and will not be implemented in Gaza because it undermines the Palestinian cause.[45]

Papua New Guinea

E-National ID cards were rolled out in 2015.[46]

Philippines

Philippine identity card.

A new Philippines identity card known as the Philippine Identification System (PhilSys) ID card began to be issued in August 2018 to Filipino citizens and foreign residents age 18 and above. This national ID card is non-compulsory but should harmonize existing government-initiated identification cards that have been issued – including the Unified Multi-Purpose ID issued to members of the Social Security System, Government Service Insurance System, Philippine Health Insurance Corporation and the Home Development Mutual Fund (Pag-IBIG Fund).

Singapore

In Singapore, every citizen, and permanent resident (PR) must register at the age of 15 for an Identity Card (IC). The card is necessary not only for procedures of state but also in the day-to-day transactions such as registering for a mobile phone line, obtaining certain discounts at stores, and logging on to certain websites on the internet. Schools frequently use it to identify students, both online and in exams.[47]

South Korea

Every citizen of South Korea over the age of 17 is issued an ID card called Jumindeungrokjeung (주민등록증). It has had several changes in its history, the most recent form being a plastic card meeting the ISO 7810 standard. The card has the holder’s photo and a 15 digit ID number calculated from the holder’s birthday and birthplace. A hologram is applied for the purpose of hampering forgery. This card has no additional features used to identify the holder, save the photo. Other than this card, the South Korean government accepts a Korean driver’s license card, an Alien Registration Card, a passport and a public officer ID card as an official ID card.

Sri Lanka

The E-National Identity Card (abbreviation: E-NIC) is the identity document in use in Sri Lanka. It is compulsory for all Sri Lankan citizens who are sixteen years of age and older to have a NIC. NICs are issued from the Department for Registration of Persons. The Registration of Persons Act No.32 of 1968 as amended by Act Nos 28 and 37 of 1971 and Act No.11 of 1981 legislates the issuance and usage of NICs.

Sri Lanka is in the process of developing a Smart Card based RFID NIC card which will replace the obsolete ‘laminated type’ cards by storing the holders information on a chip that can be read by banks, offices, etc., thereby reducing the need to have documentation of these data physically by storing in the cloud.

The NIC number is used for unique personal identification, similar to the social security number in the US.

In Sri Lanka, all citizens over the age of 16 need to apply for a National Identity Card (NIC). Each NIC has a unique 10 digit number, in the format 000000000A (where 0 is a digit and A is a letter). The first two digits of the number are your year of birth (e.g.: 93xxxxxxxx for someone born in 1993). The final letter is generally a ‘V’ or ‘X’. An NIC number is required to apply for a passport (over 16), driving license (over 18) and to vote (over 18). In addition, all citizens are required to carry their NIC on them at all times as proof of identity, given the security situation in the country.[citation needed] NICs are not issued to non-citizens, who are still required to carry a form of photo identification (such as a photocopy of their passport or foreign driving license) at all times. At times the Postal ID card may also be used.

Taiwan

The «National Identification Card» (Chinese: 國民身分證) is issued to all nationals of the Republic of China (Official name of Taiwan) aged 14 and older who have household registration in the Taiwan area. The Identification Card is used for virtually all activities that require identity verification within Taiwan such as opening bank accounts, renting apartments, employment applications and voting.

The Identification Card contains the holder’s photo, ID number, Chinese name, and (Minguo calendar) date of birth. The back of the card also contains the person’s registered address where official correspondence is sent, place of birth, and the name of legal ascendants and spouse (if any).

If residents move, they must re-register at a municipal office (Chinese: 戶政事務所).

ROC nationals with household registration in Taiwan are known as «registered nationals». ROC nationals who do not have household registration in Taiwan (known as «unregistered nationals») do not qualify for the Identification Card and its associated privileges (e.g., the right to vote and the right of abode in Taiwan), but qualify for the Republic of China passport, which unlike the Identification Card, is not indicative of residency rights in Taiwan. If such «unregistered nationals» are residents of Taiwan, they will hold a Taiwan Area Resident Certificate as an identity document, which is nearly identical to the Alien Resident Certificate issued to foreign nationals/citizens residing in Taiwan.

Thailand

Thai national identity card

In Thailand, the Thai National ID Card (Thai: บัตรประจำตัวประชาชน; RTGS: bat pracham tua pracha chon) is an official identity document issued only to Thai Nationals. The card proves the holder’s identity for receiving government services and other entitlements.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

The Federal Authority For Identity and Citizenship is a government agency that is responsible for issuing the National Identity Cards for the citizens (UAE nationals), GCC (Gulf Corporation Council) nationals and residents in the country. All individuals are mandated to apply for the ID card at all ages. For individuals of 15 years and above, fingerprint biometrics (10 fingerprints, palm, and writer) are captured in the registration process. Each person has a unique 15-digit identification number (IDN) that a person holds throughout his/her life.

The Identity Card is a smart card that has a state-of-art technology in the smart cards field with very high security features which make it difficult to duplicate. It is a 144KB Combi Smart Card, where the electronic chip includes personal information, 2 fingerprints, 4-digit pin code, digital signature, and certificates (digital and encryption). Personal photo, IDN, name, date of birth, signature, nationality, and the ID card expiry date are fields visible on the physical card.

In the UAE it is used as an official identification document for all individuals to benefit from services in the government, some of the non-government, and private entities in the UAE. This supports the UAE’s vision of smart government as the ID card is used to securely access e-services in the country. The ID card could also be used by citizens as an official travel document between GCC countries instead of using passports. The implementation of the national ID program in the UAE enhanced security of the individuals by protecting their identities and preventing identity theft.[48]

Vietnam

In Vietnam, all citizens above 14 years old must possess a citizen identification card provided by the local authority, and must be reissued when the citizens’ years of age reach 25, 40 and 60. Formerly a people’s ID document was used.

Europe

European Economic Area

National identity cards issued to citizens of the EEA (European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway) and Switzerland, which states EEA or Swiss citizenship, can not only be used as an identity document within the home country, but also as a travel document to exercise the right of free movement in the EEA and Switzerland.[49][50][51]

During the UK Presidency of the EU in 2005 a decision was made to: «Agree common standards for security features and secure issuing procedures for ID cards (December 2005), with detailed standards agreed as soon as possible thereafter. In this respect, the UK Presidency put forward a proposal for the EU-wide use of biometrics in national identity cards».[52]

From August 2, 2021, the European identity card[53][54] is intended to replace and standardize the various identity card styles currently in use.[c][56][57]

Austria

Current Austrian identity card.

The Austrian identity card is issued to Austrian citizens. It can be used as a travel document when visiting countries in the EEA (EU plus EFTA) countries, Europe’s microstates, the British Crown Possessions, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, the Republic of Macedonia,[citation needed] North Cyprus, Serbia, Montserrat, the French overseas territories and British Crown Possessions, and on organized tours to Jordan (through Aqaba airport) and Tunisia. Only around 10% of the citizens of Austria had this card in 2012,[2] as they can use the Austrian driver’s licenses or other identity cards domestically and the more widely accepted Austrian passport abroad.

Belgium

Belgian national identity card

In Belgium, everyone above the age of 12 is issued an identity card (carte d’identité in French, identiteitskaart in Dutch and Personalausweis in German), and from the age of 15 carrying this card at all times is mandatory. For foreigners residing in Belgium, similar cards (foreigner’s cards, vreemdelingenkaart in Dutch, carte pour étrangers in French) are issued, although they may also carry a passport, a work permit, or a (temporary) residence permit.

Since 2000, all newly issued Belgian identity cards have a chip (eID card), and roll-out of these cards is expected to be complete in the course of 2009. Since 2008, the aforementioned foreigner’s card has also been replaced by an eID card, containing a similar chip. The eID cards can be used both in the public and private sector for identification and for the creation of legally binding electronic signatures.

Until end 2010 Belgian consulates issued old style ID cards (105 x 75 mm) to Belgian citizens who were permanently residing in their jurisdiction and who chose to be registered at the consulate (which is strongly advised).

Since 2011 Belgian consulates issue electronic ID cards, the electronic chip on which is not activated however.

Bulgaria

In Bulgaria, it is obligatory to possess an identity card (Bulgarian – лична карта, lichna karta) at the age of 14 and above. Any person above 14 being checked by the police without carrying at least some form of identification is liable to a fine of 50 Bulgarian levs (about €25).

Croatia

All Croatian citizens may request an Identity Card, called Osobna iskaznica (literally Personal card). All persons over the age of 18 must have an Identity Card and carry it at all times. Refusal to carry or produce an Identity Card to a police officer can lead to a fine of 100 kuna or more and detention until the individual’s identity can be verified by fingerprints.

The Croatian ID card is valid in the entire European Union, and can also be used to travel throughout the non-EU countries of the Balkans.

The 2013 design of the Croatian ID card is prepared for future installation of an electronic identity card chip, which is set for implementation in 2014.[58]

Cyprus

The acquisition and possession of a Civil Identity Card is compulsory for any eligible person who has reached twelve years of age. On January 29, 2015, it was announced that all future IDs to be issued will be biometric.[59] They can be applied for at Citizen Service Centres (KEP) or at consulates with biometric data capturing facilities.

An ID card costs €30 for adults and €20 for children with 10/5 years validity respectively. It is a valid travel document for the entire European Union.

Czech Republic