«Acetic» redirects here. Not to be confused with Ascetic.

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Acetic acid[3] |

||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ethanoic acid |

||

| Other names

Vinegar (when dilute); Hydrogen acetate; Methanecarboxylic acid[1][2] |

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

|

| 3DMet |

|

|

| Abbreviations | AcOH | |

|

Beilstein Reference |

506007 | |

| ChEBI |

|

|

| ChEMBL |

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

| DrugBank |

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.528 |

|

| EC Number |

|

|

| E number | E260 (preservatives) | |

|

Gmelin Reference |

1380 | |

|

IUPHAR/BPS |

|

|

| KEGG |

|

|

| MeSH | Acetic+acid | |

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

|

| UNII |

|

|

| UN number | 2789 | |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

|

InChI

|

||

|

SMILES

|

||

| Properties | ||

|

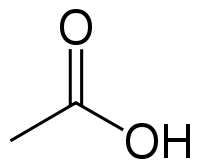

Chemical formula |

CH3COOH | |

| Molar mass | 60.052 g·mol−1 | |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid | |

| Odor | Heavily vinegar-like | |

| Density | 1.049 g/cm3 (liquid); 1.27 g/cm3 (solid) | |

| Melting point | 16 to 17 °C; 61 to 62 °F; 289 to 290 K | |

| Boiling point | 118 to 119 °C; 244 to 246 °F; 391 to 392 K | |

|

Solubility in water |

Miscible | |

| log P | -0.28[4] | |

| Vapor pressure | 11.6 mmHg (20 °C)[5] | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.756 | |

| Conjugate base | Acetate | |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

-31.54·10−6 cm3/mol | |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

1.371 (VD = 18.19) | |

| Viscosity | 1.22 mPa s | |

|

Dipole moment |

1.74 D | |

| Thermochemistry | ||

|

Heat capacity (C) |

123.1 J K−1 mol−1 | |

|

Std molar |

158.0 J K−1 mol−1 | |

|

Std enthalpy of |

-483.88–483.16 kJ/mol | |

|

Std enthalpy of |

-875.50–874.82 kJ/mol | |

| Pharmacology | ||

|

ATC code |

G01AD02 (WHO) S02AA10 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | ||

| GHS labelling: | ||

|

Pictograms |

|

|

|

Signal word |

Danger | |

|

Hazard statements |

H226, H314 | |

|

Precautionary statements |

P280, P305+P351+P338, P310 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3 2 0 |

|

| Flash point | 40 °C (104 °F; 313 K) | |

|

Autoignition |

427 °C (801 °F; 700 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 4–16% | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | ||

|

LD50 (median dose) |

3.31 g kg−1, oral (rat) | |

|

LC50 (median concentration) |

5620 ppm (mouse, 1 hr) 16000 ppm (rat, 4 hr)[7] |

|

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | ||

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 ppm (25 mg/m3)[6] | |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 ppm (25 mg/m3) ST 15 ppm (37 mg/m3)[6] | |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

50 ppm[6] | |

| Related compounds | ||

|

Related carboxylic acids |

Formic acid Propionic acid |

|

|

Related compounds |

Acetaldehyde Acetamide Acetic anhydride Chloroacetic acid Acetyl chloride Glycolic acid Ethyl acetate Potassium acetate Sodium acetate Thioacetic acid |

|

| Supplementary data page | ||

| Acetic acid (data page) | ||

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

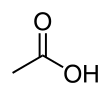

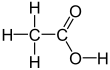

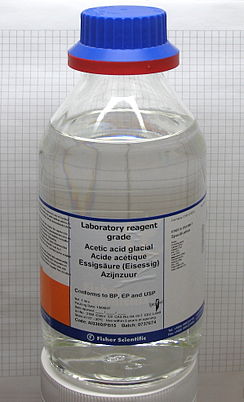

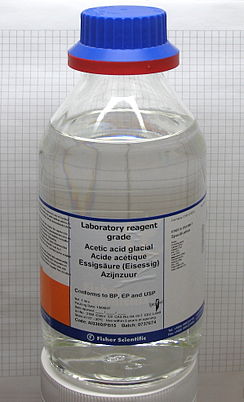

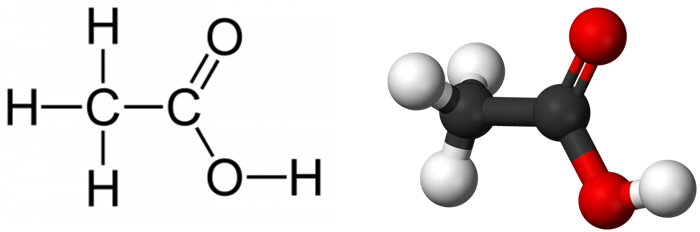

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula CH3COOH (also written as CH3CO2H, C2H4O2, or HC2H3O2). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main component of vinegar apart from water and other trace elements.

Acetic acid is the second simplest carboxylic acid (after formic acid). It is an important chemical reagent and industrial chemical, used primarily in the production of cellulose acetate for photographic film, polyvinyl acetate for wood glue, and synthetic fibres and fabrics. In households, diluted acetic acid is often used in descaling agents. In the food industry, acetic acid is controlled by the food additive code E260 as an acidity regulator and as a condiment. In biochemistry, the acetyl group, derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to all forms of life. When bound to coenzyme A, it is central to the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats.

The global demand for acetic acid is about 6.5 million metric tons per year (t/a), of which approximately 1.5 t/a is met by recycling; the remainder is manufactured from methanol.[8] Vinegar is mostly dilute acetic acid, often produced by fermentation and subsequent oxidation of ethanol.

Nomenclature[edit]

The trivial name «acetic acid» is the most commonly used and preferred IUPAC name. The systematic name «ethanoic acid», a valid IUPAC name, is constructed according to the substitutive nomenclature.[9] The name «acetic acid» derives from «acetum», the Latin word for vinegar, and is related to the word «acid» itself.

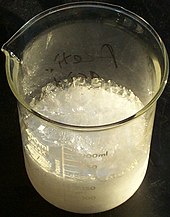

«Glacial acetic acid» is a name for water-free (anhydrous) acetic acid. Similar to the German name «Eisessig» («ice vinegar»), the name comes from the ice-like crystals that form slightly below room temperature at 16.6 °C (61.9 °F) (the presence of 0.1% water lowers its melting point by 0.2 °C).[10]

A common symbol for acetic acid is AcOH, where Ac is the pseudoelement symbol representing the acetyl group CH3−C(=O)−; the conjugate base, acetate (CH3COO−), is thus represented as AcO−.[11] (The symbol Ac for the acetyl functional group is not to be confused with the symbol Ac for the element actinium; the context prevents confusion among organic chemists). To better reflect its structure, acetic acid is often written as CH3−C(O)OH, CH3−C(=O)OH, CH3COOH, and CH3CO2H. In the context of acid–base reactions, the abbreviation HAc is sometimes used,[12] where Ac in this case is a symbol for acetate (rather than acetyl). Acetate is the ion resulting from loss of H+ from acetic acid. The name «acetate» can also refer to a salt containing this anion, or an ester of acetic acid.[13]

Properties[edit]

Acidity[edit]

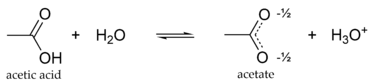

The hydrogen centre in the carboxyl group (−COOH) in carboxylic acids such as acetic acid can separate from the molecule by ionization:

- CH3COOH ⇌ CH3CO−2 + H+

Because of this release of the proton (H+), acetic acid has acidic character. Acetic acid is a weak monoprotic acid. In aqueous solution, it has a pKa value of 4.76.[14] Its conjugate base is acetate (CH3COO−). A 1.0 M solution (about the concentration of domestic vinegar) has a pH of 2.4, indicating that merely 0.4% of the acetic acid molecules are dissociated.[a] However, in very dilute (< 10−6 M) solution acetic acid is >90% dissociated.

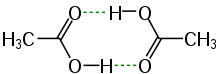

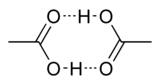

Cyclic dimer of acetic acid; dashed green lines represent hydrogen bonds

Structure[edit]

In solid acetic acid, the molecules form chains, individual molecules being interconnected by hydrogen bonds.[15] In the vapour at 120 °C (248 °F), dimers can be detected. Dimers also occur in the liquid phase in dilute solutions in non-hydrogen-bonding solvents, and a certain extent in pure acetic acid,[16] but are disrupted by hydrogen-bonding solvents. The dissociation enthalpy of the dimer is estimated at 65.0–66.0 kJ/mol, and the dissociation entropy at 154–157 J mol−1 K−1.[17] Other carboxylic acids engage in similar intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions.[18]

Solvent properties[edit]

Liquid acetic acid is a hydrophilic (polar) protic solvent, similar to ethanol and water. With a relative static permittivity (dielectric constant) of 6.2, it dissolves not only polar compounds such as inorganic salts and sugars, but also non-polar compounds such as oils as well as polar solutes. It is miscible with polar and non-polar solvents such as water, chloroform, and hexane. With higher alkanes (starting with octane), acetic acid is not miscible at all compositions, and solubility of acetic acid in alkanes declines with longer n-alkanes.[19] The solvent and miscibility properties of acetic acid make it a useful industrial chemical, for example, as a solvent in the production of dimethyl terephthalate.[8]

Biochemistry[edit]

At physiological pHs, acetic acid is usually fully ionised to acetate.

The acetyl group, formally derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to all forms of life. When bound to coenzyme A, it is central to the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats. Unlike longer-chain carboxylic acids (the fatty acids), acetic acid does not occur in natural triglycerides. However, the artificial triglyceride triacetin (glycerine triacetate) is a common food additive and is found in cosmetics and topical medicines.[20]

Acetic acid is produced and excreted by acetic acid bacteria, notably the genus Acetobacter and Clostridium acetobutylicum. These bacteria are found universally in foodstuffs, water, and soil, and acetic acid is produced naturally as fruits and other foods spoil. Acetic acid is also a component of the vaginal lubrication of humans and other primates, where it appears to serve as a mild antibacterial agent.[21]

Production[edit]

Purification and concentration plant for acetic acid in 1884

Acetic acid is produced industrially both synthetically and by bacterial fermentation. About 75% of acetic acid made for use in the chemical industry is made by the carbonylation of methanol, explained below.[8] The biological route accounts for only about 10% of world production, but it remains important for the production of vinegar because many food purity laws require vinegar used in foods to be of biological origin. Other processes are methyl formate isomerization, conversion of syngas to acetic acid, and gas phase oxidation of ethylene and ethanol.[22]

Acetic acid can be purified via fractional freezing using an ice bath. The water and other impurities will remain liquid while the acetic acid will precipitate out. As of 2003–2005, total worldwide production of virgin acetic acid[b] was estimated at 5 Mt/a (million tonnes per year), approximately half of which was produced in the United States. European production was approximately 1 Mt/a and declining, while Japanese production was 0.7 Mt/a. Another 1.5 Mt were recycled each year, bringing the total world market to 6.5 Mt/a.[23][24] Since then the global production has increased to 10.7 Mt/a (in 2010), and further; however, a slowing in this increase in production is predicted.[25] The two biggest producers of virgin acetic acid are Celanese and BP Chemicals. Other major producers include Millennium Chemicals, Sterling Chemicals, Samsung, Eastman, and Svensk Etanolkemi [sv].[26]

Methanol carbonylation[edit]

Most acetic acid is produced by methanol carbonylation. In this process, methanol and carbon monoxide react to produce acetic acid according to the equation:

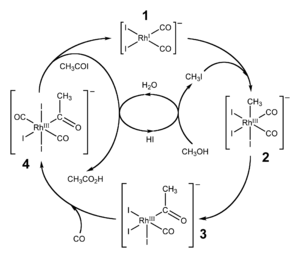

The process involves iodomethane as an intermediate, and occurs in three steps. A catalyst, metal carbonyl, is needed for the carbonylation (step 2).[27]

- CH3OH + HI → CH3I + H2O

- CH3I + CO → CH3COI

- CH3COI + H2O → CH3COOH + HI

Two related processes exist for the carbonylation of methanol: the rhodium-catalyzed Monsanto process, and the iridium-catalyzed Cativa process. The latter process is greener and more efficient[28] and has largely supplanted the former process, often in the same production plants. Catalytic amounts of water are used in both processes, but the Cativa process requires less, so the water-gas shift reaction is suppressed, and fewer by-products are formed.

By altering the process conditions, acetic anhydride may also be produced on the same plant using the rhodium catalysts.[29]

Acetaldehyde oxidation[edit]

Prior to the commercialization of the Monsanto process, most acetic acid was produced by oxidation of acetaldehyde. This remains the second-most-important manufacturing method, although it is usually not competitive with the carbonylation of methanol. The acetaldehyde can be produced by hydration of acetylene. This was the dominant technology in the early 1900s.[30]

Light naphtha components are readily oxidized by oxygen or even air to give peroxides, which decompose to produce acetic acid according to the chemical equation, illustrated with butane:

- 2 C4H10 + 5 O2 → 4 CH3CO2H + 2 H2O

Such oxidations require metal catalyst, such as the naphthenate salts of manganese, cobalt, and chromium.

The typical reaction is conducted at temperatures and pressures designed to be as hot as possible while still keeping the butane a liquid. Typical reaction conditions are 150 °C (302 °F) and 55 atm.[31] Side-products may also form, including butanone, ethyl acetate, formic acid, and propionic acid. These side-products are also commercially valuable, and the reaction conditions may be altered to produce more of them where needed. However, the separation of acetic acid from these by-products adds to the cost of the process.[32]

Under similar conditions and using similar catalysts as are used for butane oxidation, the oxygen in air to produce acetic acid can oxidize acetaldehyde.[32]

- 2 CH3CHO + O2 → 2 CH3CO2H

Using modern catalysts, this reaction can have an acetic acid yield greater than 95%. The major side-products are ethyl acetate, formic acid, and formaldehyde, all of which have lower boiling points than acetic acid and are readily separated by distillation.[32]

Ethylene oxidation[edit]

Acetaldehyde may be prepared from ethylene via the Wacker process, and then oxidised as above.

In more recent times, chemical company Showa Denko, which opened an ethylene oxidation plant in Ōita, Japan, in 1997, commercialised a cheaper single-stage conversion of ethylene to acetic acid.[33] The process is catalyzed by a palladium metal catalyst supported on a heteropoly acid such as silicotungstic acid. A similar process uses the same metal catalyst on silicotungstic acid and silica:[34]

- C2H4 + O2 → CH3CO2H

It is thought to be competitive with methanol carbonylation for smaller plants (100–250 kt/a), depending on the local price of ethylene.

The approach will be based on utilizing a novel selective photocatalytic oxidation technology for the selective oxidation of ethylene and ethane to acetic acid. Unlike traditional oxidation catalysts, the selective oxidation process will use UV light to produce acetic acid at ambient temperatures and pressure.

Oxidative fermentation[edit]

For most of human history, acetic acid bacteria of the genus Acetobacter have made acetic acid, in the form of vinegar. Given sufficient oxygen, these bacteria can produce vinegar from a variety of alcoholic foodstuffs. Commonly used feeds include apple cider, wine, and fermented grain, malt, rice, or potato mashes. The overall chemical reaction facilitated by these bacteria is:

- C2H5OH + O2 → CH3COOH + H2O

A dilute alcohol solution inoculated with Acetobacter and kept in a warm, airy place will become vinegar over the course of a few months. Industrial vinegar-making methods accelerate this process by improving the supply of oxygen to the bacteria.[35]

The first batches of vinegar produced by fermentation probably followed errors in the winemaking process. If must is fermented at too high a temperature, acetobacter will overwhelm the yeast naturally occurring on the grapes. As the demand for vinegar for culinary, medical, and sanitary purposes increased, vintners quickly learned to use other organic materials to produce vinegar in the hot summer months before the grapes were ripe and ready for processing into wine. This method was slow, however, and not always successful, as the vintners did not understand the process.[36]

One of the first modern commercial processes was the «fast method» or «German method», first practised in Germany in 1823. In this process, fermentation takes place in a tower packed with wood shavings or charcoal. The alcohol-containing feed is trickled into the top of the tower, and fresh air supplied from the bottom by either natural or forced convection. The improved air supply in this process cut the time to prepare vinegar from months to weeks.[37]

Nowadays, most vinegar is made in submerged tank culture, first described in 1949 by Otto Hromatka and Heinrich Ebner.[38] In this method, alcohol is fermented to vinegar in a continuously stirred tank, and oxygen is supplied by bubbling air through the solution. Using modern applications of this method, vinegar of 15% acetic acid can be prepared in only 24 hours in batch process, even 20% in 60-hour fed-batch process.[36]

Anaerobic fermentation[edit]

Species of anaerobic bacteria, including members of the genus Clostridium or Acetobacterium can convert sugars to acetic acid directly without creating ethanol as an intermediate. The overall chemical reaction conducted by these bacteria may be represented as:

- C6H12O6 → 3 CH3COOH

These acetogenic bacteria produce acetic acid from one-carbon compounds, including methanol, carbon monoxide, or a mixture of carbon dioxide and hydrogen:

- 2 CO2 + 4 H2 → CH3COOH + 2 H2O

This ability of Clostridium to metabolize sugars directly, or to produce acetic acid from less costly inputs, suggests that these bacteria could produce acetic acid more efficiently than ethanol-oxidizers like Acetobacter. However, Clostridium bacteria are less acid-tolerant than Acetobacter. Even the most acid-tolerant Clostridium strains can produce vinegar in concentrations of only a few per cent, compared to Acetobacter strains that can produce vinegar in concentrations up to 20%. At present, it remains more cost-effective to produce vinegar using Acetobacter, rather than using Clostridium and concentrating it. As a result, although acetogenic bacteria have been known since 1940, their industrial use is confined to a few niche applications.[39]

Uses[edit]

Acetic acid is a chemical reagent for the production of chemical compounds. The largest single use of acetic acid is in the production of vinyl acetate monomer, closely followed by acetic anhydride and ester production. The volume of acetic acid used in vinegar is comparatively small.[8][24]

Vinyl acetate monomer[edit]

The primary use of acetic acid is the production of vinyl acetate monomer (VAM). In 2008, this application was estimated to consume a third of the world’s production of acetic acid.[8] The reaction consists of ethylene and acetic acid with oxygen over a palladium catalyst, conducted in the gas phase.[40]

- 2 H3C−COOH + 2 C2H4 + O2 → 2 H3C−CO−O−CH=CH2 + 2 H2O

Vinyl acetate can be polymerised to polyvinyl acetate or other polymers, which are components in paints and adhesives.[40]

Ester production[edit]

The major esters of acetic acid are commonly used as solvents for inks, paints and coatings. The esters include ethyl acetate, n-butyl acetate, isobutyl acetate, and propyl acetate. They are typically produced by catalyzed reaction from acetic acid and the corresponding alcohol:

- CH3COO−H + HO−R → CH3COO−R + H2O, R = general alkyl group

For example, acetic acid and ethanol gives ethyl acetate and water.

- CH3COO−H + HO−CH2CH3 → CH3COO−CH2CH3 + H2O

Most acetate esters, however, are produced from acetaldehyde using the Tishchenko reaction. In addition, ether acetates are used as solvents for nitrocellulose, acrylic lacquers, varnish removers, and wood stains. First, glycol monoethers are produced from ethylene oxide or propylene oxide with alcohol, which are then esterified with acetic acid. The three major products are ethylene glycol monoethyl ether acetate (EEA), ethylene glycol monobutyl ether acetate (EBA), and propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PMA, more commonly known as PGMEA in semiconductor manufacturing processes, where it is used as a resist solvent). This application consumes about 15% to 20% of worldwide acetic acid. Ether acetates, for example EEA, have been shown to be harmful to human reproduction.[24]

Acetic anhydride[edit]

The product of the condensation of two molecules of acetic acid is acetic anhydride. The worldwide production of acetic anhydride is a major application, and uses approximately 25% to 30% of the global production of acetic acid. The main process involves dehydration of acetic acid to give ketene at 700–750 °C. Ketene is thereafter reacted with acetic acid to obtain the anhydride:[41]

- CH3CO2H → CH2=C=O + H2O

- CH3CO2H + CH2=C=O → (CH3CO)2O

Acetic anhydride is an acetylation agent. As such, its major application is for cellulose acetate, a synthetic textile also used for photographic film. Acetic anhydride is also a reagent for the production of heroin and other compounds.[41]

Use as solvent[edit]

As a polar protic solvent, acetic acid is frequently used for recrystallization to purify organic compounds. Acetic acid is used as a solvent in the production of terephthalic acid (TPA), the raw material for polyethylene terephthalate (PET). In 2006, about 20% of acetic acid was used for TPA production.[24]

Acetic acid is often used as a solvent for reactions involving carbocations, such as Friedel-Crafts alkylation. For example, one stage in the commercial manufacture of synthetic camphor involves a Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement of camphene to isobornyl acetate; here acetic acid acts both as a solvent and as a nucleophile to trap the rearranged carbocation.[42]

Glacial acetic acid is used in analytical chemistry for the estimation of weakly alkaline substances such as organic amides. Glacial acetic acid is a much weaker base than water, so the amide behaves as a strong base in this medium. It then can be titrated using a solution in glacial acetic acid of a very strong acid, such as perchloric acid.[43]

Medical use[edit]

Acetic acid injection into a tumor has been used to treat cancer since the 1800s.[44][45]

Acetic acid is used as part of cervical cancer screening in many areas in the developing world.[46] The acid is applied to the cervix and if an area of white appears after about a minute the test is positive.[46]

Acetic acid is an effective antiseptic when used as a 1% solution, with broad spectrum of activity against streptococci, staphylococci, pseudomonas, enterococci and others.[47][48][49] It may be used to treat skin infections caused by pseudomonas strains resistant to typical antibiotics.[50]

While diluted acetic acid is used in iontophoresis, no high quality evidence supports this treatment for rotator cuff disease.[51][52]

As a treatment for otitis externa, it is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.[53][54]

Foods[edit]

Acetic acid has 349 kcal (1,460 kJ) per 100 g.[55] Vinegar is typically no less than 4% acetic acid by mass.[56][57][58] Legal limits on acetic acid content vary by jurisdiction. Vinegar is used directly as a condiment, and in the pickling of vegetables and other foods. Table vinegar tends to be more diluted (4% to 8% acetic acid), while commercial food pickling employs solutions that are more concentrated. The proportion of acetic acid used worldwide as vinegar is not as large as commercial uses, but is by far the oldest and best-known application.[59]

Reactions[edit]

Organic chemistry[edit]

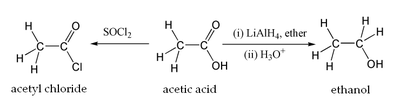

Two typical organic reactions of acetic acid

Acetic acid undergoes the typical chemical reactions of a carboxylic acid. Upon treatment with a standard base, it converts to metal acetate and water. With strong bases (e.g., organolithium reagents), it can be doubly deprotonated to give LiCH2COOLi. Reduction of acetic acid gives ethanol. The OH group is the main site of reaction, as illustrated by the conversion of acetic acid to acetyl chloride. Other substitution derivatives include acetic anhydride; this anhydride is produced by loss of water from two molecules of acetic acid. Esters of acetic acid can likewise be formed via Fischer esterification, and amides can be formed. When heated above 440 °C (824 °F), acetic acid decomposes to produce carbon dioxide and methane, or to produce ketene and water:[60][61][62]

- CH3COOH → CH4 + CO2

- CH3COOH → CH2=C=O + H2O

Reactions with inorganic compounds[edit]

Acetic acid is mildly corrosive to metals including iron, magnesium, and zinc, forming hydrogen gas and salts called acetates:

- Mg + 2 CH3COOH → (CH3COO)2Mg + H2

Because aluminium forms a passivating acid-resistant film of aluminium oxide, aluminium tanks are used to transport acetic acid. Metal acetates can also be prepared from acetic acid and an appropriate base, as in the popular «baking soda + vinegar» reaction giving off sodium acetate:

- NaHCO3 + CH3COOH → CH3COONa + CO2 + H2O

A colour reaction for salts of acetic acid is iron(III) chloride solution, which results in a deeply red colour that disappears after acidification.[63] A more sensitive test uses lanthanum nitrate with iodine and ammonia to give a blue solution.[64] Acetates when heated with arsenic trioxide form cacodyl oxide, which can be detected by its malodorous vapours.[65]

Other derivatives[edit]

Organic or inorganic salts are produced from acetic acid. Some commercially significant derivatives:

- Sodium acetate, used in the textile industry and as a food preservative (E262).

- Copper(II) acetate, used as a pigment and a fungicide.

- Aluminium acetate and iron(II) acetate—used as mordants for dyes.

- Palladium(II) acetate, used as a catalyst for organic coupling reactions such as the Heck reaction.

Halogenated acetic acids are produced from acetic acid. Some commercially significant derivatives:

- Chloroacetic acid (monochloroacetic acid, MCA), dichloroacetic acid (considered a by-product), and trichloroacetic acid. MCA is used in the manufacture of indigo dye.

- Bromoacetic acid, which is esterified to produce the reagent ethyl bromoacetate.

- Trifluoroacetic acid, which is a common reagent in organic synthesis.

Amounts of acetic acid used in these other applications together account for another 5–10% of acetic acid use worldwide.[24]

History[edit]

Vinegar was known early in civilization as the natural result of exposure of beer and wine to air, because acetic acid-producing bacteria are present globally. The use of acetic acid in alchemy extends into the third century BC, when the Greek philosopher Theophrastus described how vinegar acted on metals to produce pigments useful in art, including white lead (lead carbonate) and verdigris, a green mixture of copper salts including copper(II) acetate. Ancient Romans boiled soured wine to produce a highly sweet syrup called sapa. Sapa that was produced in lead pots was rich in lead acetate, a sweet substance also called sugar of lead or sugar of Saturn, which contributed to lead poisoning among the Roman aristocracy.[66]

In the 16th-century German alchemist Andreas Libavius described the production of acetone from the dry distillation of lead acetate, ketonic decarboxylation. The presence of water in vinegar has such a profound effect on acetic acid’s properties that for centuries chemists believed that glacial acetic acid and the acid found in vinegar were two different substances. French chemist Pierre Adet proved them identical.[66][67]

Crystallised acetic acid.

In 1845 German chemist Hermann Kolbe synthesised acetic acid from inorganic compounds for the first time. This reaction sequence consisted of chlorination of carbon disulfide to carbon tetrachloride, followed by pyrolysis to tetrachloroethylene and aqueous chlorination to trichloroacetic acid, and concluded with electrolytic reduction to acetic acid.[68]

By 1910, most glacial acetic acid was obtained from the pyroligneous liquor, a product of the distillation of wood. The acetic acid was isolated by treatment with milk of lime, and the resulting calcium acetate was then acidified with sulfuric acid to recover acetic acid. At that time, Germany was producing 10,000 tons of glacial acetic acid, around 30% of which was used for the manufacture of indigo dye.[66][69]

Because both methanol and carbon monoxide are commodity raw materials, methanol carbonylation long appeared to be attractive precursors to acetic acid. Henri Dreyfus at British Celanese developed a methanol carbonylation pilot plant as early as 1925.[70] However, a lack of practical materials that could contain the corrosive reaction mixture at the high pressures needed (200 atm or more) discouraged commercialization of these routes. The first commercial methanol carbonylation process, which used a cobalt catalyst, was developed by German chemical company BASF in 1963. In 1968, a rhodium-based catalyst (cis−[Rh(CO)2I2]−) was discovered that could operate efficiently at lower pressure with almost no by-products. US chemical company Monsanto Company built the first plant using this catalyst in 1970, and rhodium-catalyzed methanol carbonylation became the dominant method of acetic acid production (see Monsanto process). In the late 1990s, the chemicals company BP Chemicals commercialised the Cativa catalyst ([Ir(CO)2I2]−), which is promoted by iridium[71] for greater efficiency. This iridium-catalyzed Cativa process is greener and more efficient[28] and has largely supplanted the Monsanto process, often in the same production plants.

Interstellar medium[edit]

Interstellar acetic acid was discovered in 1996 by a team led by David Mehringer[72] using the former Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Association array at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory and the former Millimeter Array located at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory. It was first detected in the Sagittarius B2 North molecular cloud (also known as the Sgr B2 Large Molecule Heimat source). Acetic acid has the distinction of being the first molecule discovered in the interstellar medium using solely radio interferometers; in all previous ISM molecular discoveries made in the millimetre and centimetre wavelength regimes, single dish radio telescopes were at least partly responsible for the detections.[72]

Health effects and safety[edit]

Concentrated acetic acid is corrosive to skin.[73][74] These burns or blisters may not appear until hours after exposure.

Prolonged inhalation exposure (eight hours) to acetic acid vapours at 10 ppm can produce some irritation of eyes, nose, and throat; at 100 ppm marked lung irritation and possible damage to lungs, eyes, and skin may result. Vapour concentrations of 1,000 ppm cause marked irritation of eyes, nose and upper respiratory tract and cannot be tolerated. These predictions were based on animal experiments and industrial exposure.

In 12 workers exposed for two or more years to acetic acid airborne average concentration of 51 ppm (estimated), produced symptoms of conjunctive irritation, upper respiratory tract irritation, and hyperkeratotic dermatitis. Exposure to 50 ppm or more is intolerable to most persons and results in intensive lacrimation and irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, with pharyngeal oedema and chronic bronchitis. Unacclimatised humans experience extreme eye and nasal irritation at concentrations in excess of 25 ppm, and conjunctivitis from concentrations below 10 ppm has been reported. In a study of five workers exposed for seven to 12 years to concentrations of 80 to 200 ppm at peaks, the principal findings were blackening and hyperkeratosis of the skin of the hands, conjunctivitis (but no corneal damage), bronchitis and pharyngitis, and erosion of the exposed teeth (incisors and canines).[75]

The hazards of solutions of acetic acid depend on the concentration. The following table lists the EU classification of acetic acid solutions:[76][citation needed]

| Concentration by weight |

Molarity | GHS pictograms | H-Phrases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–25% | 1.67–4.16 mol/L |

|

H315 |

| 25–90% | 4.16–14.99 mol/L |

|

H314 |

| >90% | >14.99 mol/L |

|

H226, H314 |

Concentrated acetic acid can be ignited only with difficulty at standard temperature and pressure, but becomes a flammable risk in temperatures greater than 39 °C (102 °F), and can form explosive mixtures with air at higher temperatures (explosive limits: 5.4–16%).

See also[edit]

- Acetic acid (data page)

- Acids in wine

Notes[edit]

- ^ [H3O+] = 10−2.4 = 0.4%

- ^ Acetic acid that is manufactured by intent, rather than recovered from processing (such as the production of cellulose acetates, polyvinyl alcohol operations, and numerous acetic anhydride acylations).

References[edit]

- ^ Scientific literature reviews on generally recognised as safe (GRAS) food ingredients. National Technical Information Service. 1974. p. 1.

- ^ «Chemistry», volume 5, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1961, page 374

- ^ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 745. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-00648. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ «acetic acid_msds».

- ^ Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, 10th ed.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0002». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ «Acetic acid». Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c d e Cheung, Hosea; Tanke, Robin S.; Torrence, G. Paul. «Acetic Acid». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_045.pub2.

- ^ IUPAC Provisional Recommendations 2004 Chapter P-12.1; page 4

- ^ Armarego, W.L.F.; Chai, Christina (2009). Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 6th edition. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-1-85617-567-8.

- ^ Cooper, Caroline (9 August 2010). Organic Chemist’s Desk Reference (2 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-1-4398-1166-5.

- ^ DeSousa, Luís R. (1995). Common Medical Abbreviations. Cengage Learning. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8273-6643-5.

- ^ Hendrickson, James B.; Cram, Donald J.; Hammond, George S. (1970). Organic Chemistry (3 ed.). Tokyo: McGraw Hill Kogakusha. p. 135.

- ^ Goldberg, R.; Kishore, N.; Lennen, R. (2002). «Thermodynamic Quantities for the Ionization Reactions of Buffers» (PDF). Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 31 (2): 231–370. Bibcode:2002JPCRD..31..231G. doi:10.1063/1.1416902. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2008.

- ^ Jones, R. E.; Templeton, D.H. (1958). «The crystal structure of acetic acid» (PDF). Acta Crystallographica. 11 (7): 484–487. doi:10.1107/S0365110X58001341. hdl:2027/mdp.39015077597907.

- ^ Briggs, James M.; Toan B. Nguyen; William L. Jorgensen (1991). «Monte Carlo simulations of liquid acetic acid and methyl acetate with the OPLS potential functions». Journal of Physical Chemistry. 95 (8): 3315–3322. doi:10.1021/j100161a065.

- ^ Togeas, James B. (2005). «Acetic Acid Vapor: 2. A Statistical Mechanical Critique of Vapor Density Experiments». Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 109 (24): 5438–5444. Bibcode:2005JPCA..109.5438T. doi:10.1021/jp058004j. PMID 16839071.

- ^ McMurry, John (2000). Organic Chemistry (5 ed.). Brooks/Cole. p. 818. ISBN 978-0-534-37366-5.

- ^ Zieborak, K.; Olszewski, K. (1958). Bulletin de l’Académie Polonaise des Sciences, Série des Sciences Chimiques, Géologiques et Géographiques. 6 (2): 3315–3322.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Fiume, M. Z.; Cosmetic Ingredients Review Expert Panel (June 2003). «Final report on the safety assessment of triacetin». International Journal of Toxicology. 22 (Suppl 2): 1–10. doi:10.1080/747398359. PMID 14555416.

- ^ Buckingham, J., ed. (1996). Dictionary of Organic Compounds. Vol. 1 (6th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-54090-5.

- ^ Yoneda, Noriyuki; Kusano, Satoru; Yasui, Makoto; Pujado, Peter; Wilcher, Steve (2001). «Recent advances in processes and catalysts for the production of acetic acid». Applied Catalysis A: General. 221 (1–2): 253–265. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(01)00800-6.

- ^ «Production report». Chemical & Engineering News: 67–76. 11 July 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Malveda, Michael; Funada, Chiyo (2003). «Acetic Acid». Chemicals Economic Handbook. SRI International. p. 602.5000. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011.

- ^ Acetic Acid. SRI Consulting.

- ^ «Reportlinker Adds Global Acetic Acid Market Analysis and Forecasts». Market Research Database. June 2014. p. contents.

- ^ Yoneda, N.; Kusano, S.; Yasui, M.; Pujado, P.; Wilcher, S. (2001). «Recent advances in processes and catalysts for the production of acetic acid». Applied Catalysis A: General. 221 (1–2): 253–265. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(01)00800-6.

- ^ a b Lancaster, Mike (2002). Green Chemistry, an Introductory Text. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 262–266. ISBN 978-0-85404-620-1.

- ^ Zoeller, J. R.; Agreda, V. H.; Cook, S. L.; Lafferty, N. L.; Polichnowski, S. W.; Pond, D. M. (1992). «Eastman Chemical Company Acetic Anhydride Process». Catalysis Today. 13 (1): 73–91. doi:10.1016/0920-5861(92)80188-S.

- ^ Hintermann, Lukas; Labonne, Aurélie (2007). «Catalytic Hydration of Alkynes and Its Application in Synthesis». Synthesis. 2007 (8): 1121. doi:10.1055/s-2007-966002.

- ^ Chenier, Philip J. (2002). Survey of Industrial Chemistry (3 ed.). Springer. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-306-47246-6.

- ^ a b c Sano, Ken‐ichi; Uchida, Hiroshi; Wakabayashi, Syoichirou (1999). «A new process for acetic acid production by direct oxidation of ethylene». Catalysis Surveys from Japan. 3 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1023/A:1019003230537. ISSN 1384-6574. S2CID 93855717.

- ^ Sano, Ken-ichi; Uchida, Hiroshi; Wakabayashi, Syoichirou (1999). «A new process for acetic acid production by direct oxidation of ethylene». Catalyst Surveys from Japan. 3: 66–60. doi:10.1023/A:1019003230537. S2CID 93855717.

- ^ Misono, Makoto (2009). «Recent progress in the practical applications of heteropolyacid and perovskite catalysts: Catalytic technology for the sustainable society». Catalysis Today. 144 (3–4): 285–291. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2008.10.054.

- ^ Chotani, Gopal K.; Gaertner, Alfred L.; Arbige, Michael V.; Dodge, Timothy C. (2007). «Industrial Biotechnology: Discovery to Delivery». Kent and Riegel’s Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology. Kent and Riegel’s Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology. Springer. pp. 32–34. Bibcode:2007karh.book……. ISBN 978-0-387-27842-1.

- ^ a b Hromatka, Otto; Ebner, Heinrich (1959). «Vinegar by Submerged Oxidative Fermentation». Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 51 (10): 1279–1280. doi:10.1021/ie50598a033.

- ^ Partridge, Everett P. (1931). «Acetic Acid and Cellulose Acetate in the United States A General Survey of Economic and Technical Developments». Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 23 (5): 482–498. doi:10.1021/ie50257a005.

- ^ Hromatka, O.; Ebner, H. (1949). «Investigations on vinegar fermentation: Generator for vinegar fermentation and aeration procedures». Enzymologia. 13: 369.

- ^ Sim, Jia Huey; Kamaruddin, Azlina Harun; Long, Wei Sing; Najafpour, Ghasem (2007). «Clostridium aceticum—A potential organism in catalyzing carbon monoxide to acetic acid: Application of response surface methodology». Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 40 (5): 1234–1243. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.09.017.

- ^ a b Roscher, Günter. «Vinyl Esters». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_419.

- ^ a b Held, Heimo; Rengstl, Alfred; Mayer, Dieter. «Acetic Anhydride and Mixed Fatty Acid Anhydrides». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_065.

- ^ Sell, Charles S. (2006). «4.2.15 Bicyclic Monoterpenoids». The Chemistry of Fragrances: From Perfumer to Consumer. RSC Paperbacks Series. Vol. 38 (2 ed.). Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-85404-824-3.

- ^ Felgner, Andrea. «Determination of Water Content in Perchloric acid 0,1 mol/L in acetic acid Using Karl Fischer Titration». Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ Barclay, John (1866). «Injection of Acetic Acid in Cancer». Br Med J. 2 (305): 512. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.305.512-a. PMC 2310334.

- ^ Shibata N. (1998). «Percutaneous ethanol and acetic acid injection for liver metastasis from colon cancer». Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. 25 (5): 751–5. PMID 9571976.

- ^ a b Fokom-Domgue, J.; Combescure, C.; Fokom-Defo, V.; Tebeu, P. M.; Vassilakos, P.; Kengne, A. P.; Petignat, P. (3 July 2015). «Performance of alternative strategies for primary cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies». BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 351: h3084. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3084. PMC 4490835. PMID 26142020.

- ^ Madhusudhan, V. L. (8 April 2015). «Efficacy of 1% acetic acid in the treatment of chronic wounds infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: prospective randomised controlled clinical trial». International Wound Journal. 13 (6): 1129–1136. doi:10.1111/iwj.12428. ISSN 1742-481X. PMC 7949569. PMID 25851059. S2CID 4767974.

- ^ Ryssel, H.; Kloeters, O.; Germann, G.; Schäfer, Th; Wiedemann, G.; Oehlbauer, M. (1 August 2009). «The antimicrobial effect of acetic acid—an alternative to common local antiseptics?». Burns. 35 (5): 695–700. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2008.11.009. ISSN 1879-1409. PMID 19286325.

- ^ «Antiseptics on Wounds: An Area of Controversy». www.medscape.com. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Nagoba, B. S.; Selkar, S. P.; Wadher, B. J.; Gandhi, R. C. (December 2013). «Acetic acid treatment of pseudomonal wound infections—a review». Journal of Infection and Public Health. 6 (6): 410–5. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2013.05.005. PMID 23999348.

- ^ Page, M. J.; Green, S.; Mrocki, M. A.; Surace, S. J.; Deitch, J.; McBain, B.; Lyttle, N.; Buchbinder, R. (10 June 2016). «Electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (6): CD012225. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012225. PMC 8570637. PMID 27283591.

- ^ Habif, Thomas P. (2009). Clinical Dermatology (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-323-08037-8.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ Greenfield, Heather; Southgate, D.A.T. (2003). Food Composition Data: Production, Management and Use. Rome: FAO. p. 146. ISBN 9789251049495.

- ^ «CPG Sec. 525.825 Vinegar, Definitions» (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. March 1995.

- ^ «Departmental Consolidation of the Food and Drugs Act and the Food and Drug Regulations – Part B – Division 19» (PDF). Health Canada. August 2018. p. 591.

- ^ «Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/263». Official Journal of the European Union. European Commission. February 2016.

- ^ Bernthsen, A.; Sudborough, J. J. (1922). Organic Chemistry. London: Blackie and Son. p. 155.

- ^ Blake, P. G.; Jackson, G. E. (1968). «The thermal decomposition of acetic acid». Journal of the Chemical Society B: Physical Organic: 1153–1155. doi:10.1039/J29680001153.

- ^ Bamford, C. H.; Dewar, M. J. S. (1949). «608. The thermal decomposition of acetic acid». Journal of the Chemical Society: 2877. doi:10.1039/JR9490002877.

- ^ Duan, Xiaofeng; Page, Michael (1995). «Theoretical Investigation of Competing Mechanisms in the Thermal Unimolecular Decomposition of Acetic Acid and the Hydration Reaction of Ketene». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 117 (18): 5114–5119. doi:10.1021/ja00123a013. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ Charlot, G.; Murray, R. G. (1954). Qualitative Inorganic Analysis (4 ed.). CUP Archive. p. 110.

- ^ Neelakantam, K.; Row, L Ramachangra (1940). «The Lanthanum Nitrate Test for Acetatein Inorganic Qualitative Analysis» (PDF). Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ Brantley, L. R.; Cromwell, T. M.; Mead, J. F. (1947). «Detection of acetate ion by the reaction with arsenious oxide to form cacodyl oxide». Journal of Chemical Education. 24 (7): 353. Bibcode:1947JChEd..24..353B. doi:10.1021/ed024p353. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ a b c Martin, Geoffrey (1917). Industrial and Manufacturing Chemistry (Part 1, Organic ed.). London: Crosby Lockwood. pp. 330–331.

- ^ Adet, P. A. (1798). «Mémoire sur l’acide acétique (Memoir on acetic acid)». Annales de Chimie. 27: 299–319.

- ^ Goldwhite, Harold (September 2003). «This month in chemical history» (PDF). New Haven Section Bulletin American Chemical Society. 20 (3): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009.

- ^ Schweppe, Helmut (1979). «Identification of dyes on old textiles». Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 19 (1/3): 14–23. doi:10.2307/3179569. JSTOR 3179569. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2005.

- ^ Wagner, Frank S. (1978). «Acetic acid». In Grayson, Martin (ed.). Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Industrial Organic Chemicals, Harold A. Wittcoff, Bryan G. Reuben, Jeffery S. Plotkin

- ^ a b Mehringer, David M.; et al. (1997). «Detection and Confirmation of Interstellar Acetic Acid». Astrophysical Journal Letters. 480 (1): L71. Bibcode:1997ApJ…480L..71M. doi:10.1086/310612.

- ^ «ICSC 0363 – ACETIC ACID». International Programme on Chemical Safety. 5 June 2010.

- ^ «Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Acetic Acid» (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ Sherertz, Peter C. (1 June 1994). Acetic Acid (PDF). Virginia Department of Health Division of Health Hazards Control. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ «Details». hcis.safeworkaustralia.gov.au.

External links[edit]

Look up acetic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- International Chemical Safety Card 0363

- National Pollutant Inventory – Acetic acid fact sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Method for sampling and analysis

- 29 CFR 1910.1000, Table Z-1 (US Permissible exposure limits)

- ChemSub Online: Acetic acid

- Calculation of vapor pressure, liquid density, dynamic liquid viscosity, surface tension of acetic acid

- Acetic acid bound to proteins in the PDB

- Swedish Chemicals Agency. Information sheet – Acetic Acid

- Process Flow sheet of Acetic acid Production by the Carbonylation of Methanol

«Acetic» redirects here. Not to be confused with Ascetic.

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Acetic acid[3] |

||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ethanoic acid |

||

| Other names

Vinegar (when dilute); Hydrogen acetate; Methanecarboxylic acid[1][2] |

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

|

| 3DMet |

|

|

| Abbreviations | AcOH | |

|

Beilstein Reference |

506007 | |

| ChEBI |

|

|

| ChEMBL |

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

| DrugBank |

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.528 |

|

| EC Number |

|

|

| E number | E260 (preservatives) | |

|

Gmelin Reference |

1380 | |

|

IUPHAR/BPS |

|

|

| KEGG |

|

|

| MeSH | Acetic+acid | |

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

|

| UNII |

|

|

| UN number | 2789 | |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

|

InChI

|

||

|

SMILES

|

||

| Properties | ||

|

Chemical formula |

CH3COOH | |

| Molar mass | 60.052 g·mol−1 | |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid | |

| Odor | Heavily vinegar-like | |

| Density | 1.049 g/cm3 (liquid); 1.27 g/cm3 (solid) | |

| Melting point | 16 to 17 °C; 61 to 62 °F; 289 to 290 K | |

| Boiling point | 118 to 119 °C; 244 to 246 °F; 391 to 392 K | |

|

Solubility in water |

Miscible | |

| log P | -0.28[4] | |

| Vapor pressure | 11.6 mmHg (20 °C)[5] | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.756 | |

| Conjugate base | Acetate | |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

-31.54·10−6 cm3/mol | |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

1.371 (VD = 18.19) | |

| Viscosity | 1.22 mPa s | |

|

Dipole moment |

1.74 D | |

| Thermochemistry | ||

|

Heat capacity (C) |

123.1 J K−1 mol−1 | |

|

Std molar |

158.0 J K−1 mol−1 | |

|

Std enthalpy of |

-483.88–483.16 kJ/mol | |

|

Std enthalpy of |

-875.50–874.82 kJ/mol | |

| Pharmacology | ||

|

ATC code |

G01AD02 (WHO) S02AA10 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | ||

| GHS labelling: | ||

|

Pictograms |

|

|

|

Signal word |

Danger | |

|

Hazard statements |

H226, H314 | |

|

Precautionary statements |

P280, P305+P351+P338, P310 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3 2 0 |

|

| Flash point | 40 °C (104 °F; 313 K) | |

|

Autoignition |

427 °C (801 °F; 700 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 4–16% | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | ||

|

LD50 (median dose) |

3.31 g kg−1, oral (rat) | |

|

LC50 (median concentration) |

5620 ppm (mouse, 1 hr) 16000 ppm (rat, 4 hr)[7] |

|

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | ||

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 ppm (25 mg/m3)[6] | |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 ppm (25 mg/m3) ST 15 ppm (37 mg/m3)[6] | |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

50 ppm[6] | |

| Related compounds | ||

|

Related carboxylic acids |

Formic acid Propionic acid |

|

|

Related compounds |

Acetaldehyde Acetamide Acetic anhydride Chloroacetic acid Acetyl chloride Glycolic acid Ethyl acetate Potassium acetate Sodium acetate Thioacetic acid |

|

| Supplementary data page | ||

| Acetic acid (data page) | ||

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula CH3COOH (also written as CH3CO2H, C2H4O2, or HC2H3O2). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main component of vinegar apart from water and other trace elements.

Acetic acid is the second simplest carboxylic acid (after formic acid). It is an important chemical reagent and industrial chemical, used primarily in the production of cellulose acetate for photographic film, polyvinyl acetate for wood glue, and synthetic fibres and fabrics. In households, diluted acetic acid is often used in descaling agents. In the food industry, acetic acid is controlled by the food additive code E260 as an acidity regulator and as a condiment. In biochemistry, the acetyl group, derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to all forms of life. When bound to coenzyme A, it is central to the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats.

The global demand for acetic acid is about 6.5 million metric tons per year (t/a), of which approximately 1.5 t/a is met by recycling; the remainder is manufactured from methanol.[8] Vinegar is mostly dilute acetic acid, often produced by fermentation and subsequent oxidation of ethanol.

Nomenclature[edit]

The trivial name «acetic acid» is the most commonly used and preferred IUPAC name. The systematic name «ethanoic acid», a valid IUPAC name, is constructed according to the substitutive nomenclature.[9] The name «acetic acid» derives from «acetum», the Latin word for vinegar, and is related to the word «acid» itself.

«Glacial acetic acid» is a name for water-free (anhydrous) acetic acid. Similar to the German name «Eisessig» («ice vinegar»), the name comes from the ice-like crystals that form slightly below room temperature at 16.6 °C (61.9 °F) (the presence of 0.1% water lowers its melting point by 0.2 °C).[10]

A common symbol for acetic acid is AcOH, where Ac is the pseudoelement symbol representing the acetyl group CH3−C(=O)−; the conjugate base, acetate (CH3COO−), is thus represented as AcO−.[11] (The symbol Ac for the acetyl functional group is not to be confused with the symbol Ac for the element actinium; the context prevents confusion among organic chemists). To better reflect its structure, acetic acid is often written as CH3−C(O)OH, CH3−C(=O)OH, CH3COOH, and CH3CO2H. In the context of acid–base reactions, the abbreviation HAc is sometimes used,[12] where Ac in this case is a symbol for acetate (rather than acetyl). Acetate is the ion resulting from loss of H+ from acetic acid. The name «acetate» can also refer to a salt containing this anion, or an ester of acetic acid.[13]

Properties[edit]

Acidity[edit]

The hydrogen centre in the carboxyl group (−COOH) in carboxylic acids such as acetic acid can separate from the molecule by ionization:

- CH3COOH ⇌ CH3CO−2 + H+

Because of this release of the proton (H+), acetic acid has acidic character. Acetic acid is a weak monoprotic acid. In aqueous solution, it has a pKa value of 4.76.[14] Its conjugate base is acetate (CH3COO−). A 1.0 M solution (about the concentration of domestic vinegar) has a pH of 2.4, indicating that merely 0.4% of the acetic acid molecules are dissociated.[a] However, in very dilute (< 10−6 M) solution acetic acid is >90% dissociated.

Cyclic dimer of acetic acid; dashed green lines represent hydrogen bonds

Structure[edit]

In solid acetic acid, the molecules form chains, individual molecules being interconnected by hydrogen bonds.[15] In the vapour at 120 °C (248 °F), dimers can be detected. Dimers also occur in the liquid phase in dilute solutions in non-hydrogen-bonding solvents, and a certain extent in pure acetic acid,[16] but are disrupted by hydrogen-bonding solvents. The dissociation enthalpy of the dimer is estimated at 65.0–66.0 kJ/mol, and the dissociation entropy at 154–157 J mol−1 K−1.[17] Other carboxylic acids engage in similar intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions.[18]

Solvent properties[edit]

Liquid acetic acid is a hydrophilic (polar) protic solvent, similar to ethanol and water. With a relative static permittivity (dielectric constant) of 6.2, it dissolves not only polar compounds such as inorganic salts and sugars, but also non-polar compounds such as oils as well as polar solutes. It is miscible with polar and non-polar solvents such as water, chloroform, and hexane. With higher alkanes (starting with octane), acetic acid is not miscible at all compositions, and solubility of acetic acid in alkanes declines with longer n-alkanes.[19] The solvent and miscibility properties of acetic acid make it a useful industrial chemical, for example, as a solvent in the production of dimethyl terephthalate.[8]

Biochemistry[edit]

At physiological pHs, acetic acid is usually fully ionised to acetate.

The acetyl group, formally derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to all forms of life. When bound to coenzyme A, it is central to the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats. Unlike longer-chain carboxylic acids (the fatty acids), acetic acid does not occur in natural triglycerides. However, the artificial triglyceride triacetin (glycerine triacetate) is a common food additive and is found in cosmetics and topical medicines.[20]

Acetic acid is produced and excreted by acetic acid bacteria, notably the genus Acetobacter and Clostridium acetobutylicum. These bacteria are found universally in foodstuffs, water, and soil, and acetic acid is produced naturally as fruits and other foods spoil. Acetic acid is also a component of the vaginal lubrication of humans and other primates, where it appears to serve as a mild antibacterial agent.[21]

Production[edit]

Purification and concentration plant for acetic acid in 1884

Acetic acid is produced industrially both synthetically and by bacterial fermentation. About 75% of acetic acid made for use in the chemical industry is made by the carbonylation of methanol, explained below.[8] The biological route accounts for only about 10% of world production, but it remains important for the production of vinegar because many food purity laws require vinegar used in foods to be of biological origin. Other processes are methyl formate isomerization, conversion of syngas to acetic acid, and gas phase oxidation of ethylene and ethanol.[22]

Acetic acid can be purified via fractional freezing using an ice bath. The water and other impurities will remain liquid while the acetic acid will precipitate out. As of 2003–2005, total worldwide production of virgin acetic acid[b] was estimated at 5 Mt/a (million tonnes per year), approximately half of which was produced in the United States. European production was approximately 1 Mt/a and declining, while Japanese production was 0.7 Mt/a. Another 1.5 Mt were recycled each year, bringing the total world market to 6.5 Mt/a.[23][24] Since then the global production has increased to 10.7 Mt/a (in 2010), and further; however, a slowing in this increase in production is predicted.[25] The two biggest producers of virgin acetic acid are Celanese and BP Chemicals. Other major producers include Millennium Chemicals, Sterling Chemicals, Samsung, Eastman, and Svensk Etanolkemi [sv].[26]

Methanol carbonylation[edit]

Most acetic acid is produced by methanol carbonylation. In this process, methanol and carbon monoxide react to produce acetic acid according to the equation:

The process involves iodomethane as an intermediate, and occurs in three steps. A catalyst, metal carbonyl, is needed for the carbonylation (step 2).[27]

- CH3OH + HI → CH3I + H2O

- CH3I + CO → CH3COI

- CH3COI + H2O → CH3COOH + HI

Two related processes exist for the carbonylation of methanol: the rhodium-catalyzed Monsanto process, and the iridium-catalyzed Cativa process. The latter process is greener and more efficient[28] and has largely supplanted the former process, often in the same production plants. Catalytic amounts of water are used in both processes, but the Cativa process requires less, so the water-gas shift reaction is suppressed, and fewer by-products are formed.

By altering the process conditions, acetic anhydride may also be produced on the same plant using the rhodium catalysts.[29]

Acetaldehyde oxidation[edit]

Prior to the commercialization of the Monsanto process, most acetic acid was produced by oxidation of acetaldehyde. This remains the second-most-important manufacturing method, although it is usually not competitive with the carbonylation of methanol. The acetaldehyde can be produced by hydration of acetylene. This was the dominant technology in the early 1900s.[30]

Light naphtha components are readily oxidized by oxygen or even air to give peroxides, which decompose to produce acetic acid according to the chemical equation, illustrated with butane:

- 2 C4H10 + 5 O2 → 4 CH3CO2H + 2 H2O

Such oxidations require metal catalyst, such as the naphthenate salts of manganese, cobalt, and chromium.

The typical reaction is conducted at temperatures and pressures designed to be as hot as possible while still keeping the butane a liquid. Typical reaction conditions are 150 °C (302 °F) and 55 atm.[31] Side-products may also form, including butanone, ethyl acetate, formic acid, and propionic acid. These side-products are also commercially valuable, and the reaction conditions may be altered to produce more of them where needed. However, the separation of acetic acid from these by-products adds to the cost of the process.[32]

Under similar conditions and using similar catalysts as are used for butane oxidation, the oxygen in air to produce acetic acid can oxidize acetaldehyde.[32]

- 2 CH3CHO + O2 → 2 CH3CO2H

Using modern catalysts, this reaction can have an acetic acid yield greater than 95%. The major side-products are ethyl acetate, formic acid, and formaldehyde, all of which have lower boiling points than acetic acid and are readily separated by distillation.[32]

Ethylene oxidation[edit]

Acetaldehyde may be prepared from ethylene via the Wacker process, and then oxidised as above.

In more recent times, chemical company Showa Denko, which opened an ethylene oxidation plant in Ōita, Japan, in 1997, commercialised a cheaper single-stage conversion of ethylene to acetic acid.[33] The process is catalyzed by a palladium metal catalyst supported on a heteropoly acid such as silicotungstic acid. A similar process uses the same metal catalyst on silicotungstic acid and silica:[34]

- C2H4 + O2 → CH3CO2H

It is thought to be competitive with methanol carbonylation for smaller plants (100–250 kt/a), depending on the local price of ethylene.

The approach will be based on utilizing a novel selective photocatalytic oxidation technology for the selective oxidation of ethylene and ethane to acetic acid. Unlike traditional oxidation catalysts, the selective oxidation process will use UV light to produce acetic acid at ambient temperatures and pressure.

Oxidative fermentation[edit]

For most of human history, acetic acid bacteria of the genus Acetobacter have made acetic acid, in the form of vinegar. Given sufficient oxygen, these bacteria can produce vinegar from a variety of alcoholic foodstuffs. Commonly used feeds include apple cider, wine, and fermented grain, malt, rice, or potato mashes. The overall chemical reaction facilitated by these bacteria is:

- C2H5OH + O2 → CH3COOH + H2O

A dilute alcohol solution inoculated with Acetobacter and kept in a warm, airy place will become vinegar over the course of a few months. Industrial vinegar-making methods accelerate this process by improving the supply of oxygen to the bacteria.[35]

The first batches of vinegar produced by fermentation probably followed errors in the winemaking process. If must is fermented at too high a temperature, acetobacter will overwhelm the yeast naturally occurring on the grapes. As the demand for vinegar for culinary, medical, and sanitary purposes increased, vintners quickly learned to use other organic materials to produce vinegar in the hot summer months before the grapes were ripe and ready for processing into wine. This method was slow, however, and not always successful, as the vintners did not understand the process.[36]

One of the first modern commercial processes was the «fast method» or «German method», first practised in Germany in 1823. In this process, fermentation takes place in a tower packed with wood shavings or charcoal. The alcohol-containing feed is trickled into the top of the tower, and fresh air supplied from the bottom by either natural or forced convection. The improved air supply in this process cut the time to prepare vinegar from months to weeks.[37]

Nowadays, most vinegar is made in submerged tank culture, first described in 1949 by Otto Hromatka and Heinrich Ebner.[38] In this method, alcohol is fermented to vinegar in a continuously stirred tank, and oxygen is supplied by bubbling air through the solution. Using modern applications of this method, vinegar of 15% acetic acid can be prepared in only 24 hours in batch process, even 20% in 60-hour fed-batch process.[36]

Anaerobic fermentation[edit]

Species of anaerobic bacteria, including members of the genus Clostridium or Acetobacterium can convert sugars to acetic acid directly without creating ethanol as an intermediate. The overall chemical reaction conducted by these bacteria may be represented as:

- C6H12O6 → 3 CH3COOH

These acetogenic bacteria produce acetic acid from one-carbon compounds, including methanol, carbon monoxide, or a mixture of carbon dioxide and hydrogen:

- 2 CO2 + 4 H2 → CH3COOH + 2 H2O

This ability of Clostridium to metabolize sugars directly, or to produce acetic acid from less costly inputs, suggests that these bacteria could produce acetic acid more efficiently than ethanol-oxidizers like Acetobacter. However, Clostridium bacteria are less acid-tolerant than Acetobacter. Even the most acid-tolerant Clostridium strains can produce vinegar in concentrations of only a few per cent, compared to Acetobacter strains that can produce vinegar in concentrations up to 20%. At present, it remains more cost-effective to produce vinegar using Acetobacter, rather than using Clostridium and concentrating it. As a result, although acetogenic bacteria have been known since 1940, their industrial use is confined to a few niche applications.[39]

Uses[edit]

Acetic acid is a chemical reagent for the production of chemical compounds. The largest single use of acetic acid is in the production of vinyl acetate monomer, closely followed by acetic anhydride and ester production. The volume of acetic acid used in vinegar is comparatively small.[8][24]

Vinyl acetate monomer[edit]

The primary use of acetic acid is the production of vinyl acetate monomer (VAM). In 2008, this application was estimated to consume a third of the world’s production of acetic acid.[8] The reaction consists of ethylene and acetic acid with oxygen over a palladium catalyst, conducted in the gas phase.[40]

- 2 H3C−COOH + 2 C2H4 + O2 → 2 H3C−CO−O−CH=CH2 + 2 H2O

Vinyl acetate can be polymerised to polyvinyl acetate or other polymers, which are components in paints and adhesives.[40]

Ester production[edit]

The major esters of acetic acid are commonly used as solvents for inks, paints and coatings. The esters include ethyl acetate, n-butyl acetate, isobutyl acetate, and propyl acetate. They are typically produced by catalyzed reaction from acetic acid and the corresponding alcohol:

- CH3COO−H + HO−R → CH3COO−R + H2O, R = general alkyl group

For example, acetic acid and ethanol gives ethyl acetate and water.

- CH3COO−H + HO−CH2CH3 → CH3COO−CH2CH3 + H2O

Most acetate esters, however, are produced from acetaldehyde using the Tishchenko reaction. In addition, ether acetates are used as solvents for nitrocellulose, acrylic lacquers, varnish removers, and wood stains. First, glycol monoethers are produced from ethylene oxide or propylene oxide with alcohol, which are then esterified with acetic acid. The three major products are ethylene glycol monoethyl ether acetate (EEA), ethylene glycol monobutyl ether acetate (EBA), and propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PMA, more commonly known as PGMEA in semiconductor manufacturing processes, where it is used as a resist solvent). This application consumes about 15% to 20% of worldwide acetic acid. Ether acetates, for example EEA, have been shown to be harmful to human reproduction.[24]

Acetic anhydride[edit]

The product of the condensation of two molecules of acetic acid is acetic anhydride. The worldwide production of acetic anhydride is a major application, and uses approximately 25% to 30% of the global production of acetic acid. The main process involves dehydration of acetic acid to give ketene at 700–750 °C. Ketene is thereafter reacted with acetic acid to obtain the anhydride:[41]

- CH3CO2H → CH2=C=O + H2O

- CH3CO2H + CH2=C=O → (CH3CO)2O

Acetic anhydride is an acetylation agent. As such, its major application is for cellulose acetate, a synthetic textile also used for photographic film. Acetic anhydride is also a reagent for the production of heroin and other compounds.[41]

Use as solvent[edit]

As a polar protic solvent, acetic acid is frequently used for recrystallization to purify organic compounds. Acetic acid is used as a solvent in the production of terephthalic acid (TPA), the raw material for polyethylene terephthalate (PET). In 2006, about 20% of acetic acid was used for TPA production.[24]

Acetic acid is often used as a solvent for reactions involving carbocations, such as Friedel-Crafts alkylation. For example, one stage in the commercial manufacture of synthetic camphor involves a Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement of camphene to isobornyl acetate; here acetic acid acts both as a solvent and as a nucleophile to trap the rearranged carbocation.[42]

Glacial acetic acid is used in analytical chemistry for the estimation of weakly alkaline substances such as organic amides. Glacial acetic acid is a much weaker base than water, so the amide behaves as a strong base in this medium. It then can be titrated using a solution in glacial acetic acid of a very strong acid, such as perchloric acid.[43]

Medical use[edit]

Acetic acid injection into a tumor has been used to treat cancer since the 1800s.[44][45]

Acetic acid is used as part of cervical cancer screening in many areas in the developing world.[46] The acid is applied to the cervix and if an area of white appears after about a minute the test is positive.[46]

Acetic acid is an effective antiseptic when used as a 1% solution, with broad spectrum of activity against streptococci, staphylococci, pseudomonas, enterococci and others.[47][48][49] It may be used to treat skin infections caused by pseudomonas strains resistant to typical antibiotics.[50]

While diluted acetic acid is used in iontophoresis, no high quality evidence supports this treatment for rotator cuff disease.[51][52]

As a treatment for otitis externa, it is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.[53][54]

Foods[edit]

Acetic acid has 349 kcal (1,460 kJ) per 100 g.[55] Vinegar is typically no less than 4% acetic acid by mass.[56][57][58] Legal limits on acetic acid content vary by jurisdiction. Vinegar is used directly as a condiment, and in the pickling of vegetables and other foods. Table vinegar tends to be more diluted (4% to 8% acetic acid), while commercial food pickling employs solutions that are more concentrated. The proportion of acetic acid used worldwide as vinegar is not as large as commercial uses, but is by far the oldest and best-known application.[59]

Reactions[edit]

Organic chemistry[edit]

Two typical organic reactions of acetic acid

Acetic acid undergoes the typical chemical reactions of a carboxylic acid. Upon treatment with a standard base, it converts to metal acetate and water. With strong bases (e.g., organolithium reagents), it can be doubly deprotonated to give LiCH2COOLi. Reduction of acetic acid gives ethanol. The OH group is the main site of reaction, as illustrated by the conversion of acetic acid to acetyl chloride. Other substitution derivatives include acetic anhydride; this anhydride is produced by loss of water from two molecules of acetic acid. Esters of acetic acid can likewise be formed via Fischer esterification, and amides can be formed. When heated above 440 °C (824 °F), acetic acid decomposes to produce carbon dioxide and methane, or to produce ketene and water:[60][61][62]

- CH3COOH → CH4 + CO2

- CH3COOH → CH2=C=O + H2O

Reactions with inorganic compounds[edit]

Acetic acid is mildly corrosive to metals including iron, magnesium, and zinc, forming hydrogen gas and salts called acetates:

- Mg + 2 CH3COOH → (CH3COO)2Mg + H2

Because aluminium forms a passivating acid-resistant film of aluminium oxide, aluminium tanks are used to transport acetic acid. Metal acetates can also be prepared from acetic acid and an appropriate base, as in the popular «baking soda + vinegar» reaction giving off sodium acetate:

- NaHCO3 + CH3COOH → CH3COONa + CO2 + H2O

A colour reaction for salts of acetic acid is iron(III) chloride solution, which results in a deeply red colour that disappears after acidification.[63] A more sensitive test uses lanthanum nitrate with iodine and ammonia to give a blue solution.[64] Acetates when heated with arsenic trioxide form cacodyl oxide, which can be detected by its malodorous vapours.[65]

Other derivatives[edit]

Organic or inorganic salts are produced from acetic acid. Some commercially significant derivatives:

- Sodium acetate, used in the textile industry and as a food preservative (E262).

- Copper(II) acetate, used as a pigment and a fungicide.

- Aluminium acetate and iron(II) acetate—used as mordants for dyes.

- Palladium(II) acetate, used as a catalyst for organic coupling reactions such as the Heck reaction.

Halogenated acetic acids are produced from acetic acid. Some commercially significant derivatives:

- Chloroacetic acid (monochloroacetic acid, MCA), dichloroacetic acid (considered a by-product), and trichloroacetic acid. MCA is used in the manufacture of indigo dye.

- Bromoacetic acid, which is esterified to produce the reagent ethyl bromoacetate.

- Trifluoroacetic acid, which is a common reagent in organic synthesis.

Amounts of acetic acid used in these other applications together account for another 5–10% of acetic acid use worldwide.[24]

History[edit]

Vinegar was known early in civilization as the natural result of exposure of beer and wine to air, because acetic acid-producing bacteria are present globally. The use of acetic acid in alchemy extends into the third century BC, when the Greek philosopher Theophrastus described how vinegar acted on metals to produce pigments useful in art, including white lead (lead carbonate) and verdigris, a green mixture of copper salts including copper(II) acetate. Ancient Romans boiled soured wine to produce a highly sweet syrup called sapa. Sapa that was produced in lead pots was rich in lead acetate, a sweet substance also called sugar of lead or sugar of Saturn, which contributed to lead poisoning among the Roman aristocracy.[66]

In the 16th-century German alchemist Andreas Libavius described the production of acetone from the dry distillation of lead acetate, ketonic decarboxylation. The presence of water in vinegar has such a profound effect on acetic acid’s properties that for centuries chemists believed that glacial acetic acid and the acid found in vinegar were two different substances. French chemist Pierre Adet proved them identical.[66][67]

Crystallised acetic acid.

In 1845 German chemist Hermann Kolbe synthesised acetic acid from inorganic compounds for the first time. This reaction sequence consisted of chlorination of carbon disulfide to carbon tetrachloride, followed by pyrolysis to tetrachloroethylene and aqueous chlorination to trichloroacetic acid, and concluded with electrolytic reduction to acetic acid.[68]

By 1910, most glacial acetic acid was obtained from the pyroligneous liquor, a product of the distillation of wood. The acetic acid was isolated by treatment with milk of lime, and the resulting calcium acetate was then acidified with sulfuric acid to recover acetic acid. At that time, Germany was producing 10,000 tons of glacial acetic acid, around 30% of which was used for the manufacture of indigo dye.[66][69]

Because both methanol and carbon monoxide are commodity raw materials, methanol carbonylation long appeared to be attractive precursors to acetic acid. Henri Dreyfus at British Celanese developed a methanol carbonylation pilot plant as early as 1925.[70] However, a lack of practical materials that could contain the corrosive reaction mixture at the high pressures needed (200 atm or more) discouraged commercialization of these routes. The first commercial methanol carbonylation process, which used a cobalt catalyst, was developed by German chemical company BASF in 1963. In 1968, a rhodium-based catalyst (cis−[Rh(CO)2I2]−) was discovered that could operate efficiently at lower pressure with almost no by-products. US chemical company Monsanto Company built the first plant using this catalyst in 1970, and rhodium-catalyzed methanol carbonylation became the dominant method of acetic acid production (see Monsanto process). In the late 1990s, the chemicals company BP Chemicals commercialised the Cativa catalyst ([Ir(CO)2I2]−), which is promoted by iridium[71] for greater efficiency. This iridium-catalyzed Cativa process is greener and more efficient[28] and has largely supplanted the Monsanto process, often in the same production plants.

Interstellar medium[edit]

Interstellar acetic acid was discovered in 1996 by a team led by David Mehringer[72] using the former Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Association array at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory and the former Millimeter Array located at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory. It was first detected in the Sagittarius B2 North molecular cloud (also known as the Sgr B2 Large Molecule Heimat source). Acetic acid has the distinction of being the first molecule discovered in the interstellar medium using solely radio interferometers; in all previous ISM molecular discoveries made in the millimetre and centimetre wavelength regimes, single dish radio telescopes were at least partly responsible for the detections.[72]

Health effects and safety[edit]

Concentrated acetic acid is corrosive to skin.[73][74] These burns or blisters may not appear until hours after exposure.

Prolonged inhalation exposure (eight hours) to acetic acid vapours at 10 ppm can produce some irritation of eyes, nose, and throat; at 100 ppm marked lung irritation and possible damage to lungs, eyes, and skin may result. Vapour concentrations of 1,000 ppm cause marked irritation of eyes, nose and upper respiratory tract and cannot be tolerated. These predictions were based on animal experiments and industrial exposure.