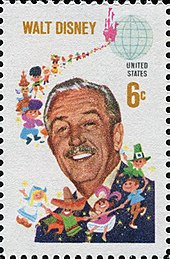

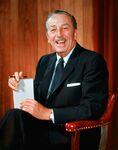

Walter Elias Disney (;[2] December 5, 1901 – December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film producer, he holds the record for most Academy Awards earned and nominations by an individual, having won 22 Oscars from 59 nominations. He was presented with two Golden Globe Special Achievement Awards and an Emmy Award, among other honors. Several of his films are included in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress and have also been named as some of the greatest films ever by the American Film Institute. Disney was the first person to be nominated for Academy Awards in six different categories.

|

Walt Disney |

|

|---|---|

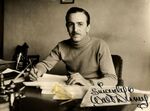

Disney in 1946 |

|

| Born |

Walter Elias Disney December 5, 1901 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 15, 1966 (aged 65)

Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Occupations |

|

| Title | President of The Walt Disney Company[1] |

| Spouse |

Lillian Disney (m. 1925) |

| Children | 2, including Diane Disney Miller |

| Relatives | Disney family |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

|

Born in Chicago in 1901, Disney developed an early interest in drawing. He took art classes as a boy and got a job as a commercial illustrator at the age of 18. He moved to California in the early 1920s and set up the Disney Brothers Studio with his brother Roy. With Ub Iwerks, he developed the character Mickey Mouse in 1928, his first highly popular success; he also provided the voice for his creation in the early years. As the studio grew, he became more adventurous, introducing synchronized sound, full-color three-strip Technicolor, feature-length cartoons and technical developments in cameras. The results, seen in features such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio, Fantasia (both 1940), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942), furthered the development of animated film. New animated and live-action films followed after World War II, including the critically successful Cinderella (1950), Sleeping Beauty (1959) and Mary Poppins (1964), the last of which received five Academy Awards.

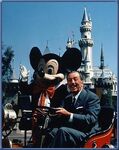

In the 1950s, Disney expanded into the amusement park industry, and in July 1955 he opened Disneyland in Anaheim, California. To fund the project he diversified into television programs, such as Walt Disney’s Disneyland and The Mickey Mouse Club. He was also involved in planning the 1959 Moscow Fair, the 1960 Winter Olympics, and the 1964 New York World’s Fair. In 1965, he began development of another theme park, Disney World, the heart of which was to be a new type of city, the «Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow» (EPCOT). Disney was a heavy smoker throughout his life and died of lung cancer in December 1966 before either the park or the EPCOT project were completed.

Disney was a shy, self-deprecating and insecure man in private but adopted a warm and outgoing public persona. He had high standards and high expectations of those with whom he worked. Although there have been accusations that he was racist or antisemitic, they have been contradicted by many who knew him. Historiography of Disney has taken a variety of perspectives, ranging from views of him as a purveyor of homely patriotic values to being a representative of American imperialism. He remains an important figure in the history of animation and in the cultural history of the United States, where he is considered a national cultural icon. His film work continues to be shown and adapted, and the Disney theme parks have grown in size and number to attract visitors in several countries.

Early life

Disney was born on December 5, 1901, at 1249 Tripp Avenue, in Chicago’s Hermosa neighborhood.[a] He was the fourth son of Elias Disney—born in the Province of Canada, to Irish parents—and Flora (née Call), an American of German and English descent.[4][5][b] Aside from Walt, Elias and Flora’s sons were Herbert, Raymond and Roy; and the couple had a fifth child, Ruth, in December 1903.[8] In 1906, when Disney was four, the family moved to a farm in Marceline, Missouri, where his uncle Robert had just purchased land. In Marceline, Disney developed his interest in drawing when he was paid to draw the horse of a retired neighborhood doctor.[9] Elias was a subscriber to the Appeal to Reason newspaper, and Disney practiced drawing by copying the front-page cartoons of Ryan Walker.[10] He also began to develop an ability to work with watercolors and crayons.[5] He lived near the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway line and became enamored with trains.[11] He and his younger sister Ruth started school at the same time at the Park School in Marceline in late 1909.[12] The Disney family were active members of a Congregational church.[13]

In 1911, the Disneys moved to Kansas City, Missouri.[14] There, Disney attended the Benton Grammar School, where he met fellow-student Walter Pfeiffer, who came from a family of theatre fans and introduced him to the world of vaudeville and motion pictures. Before long, Disney was spending more time at the Pfeiffers’ house than at home.[15] Elias had purchased a newspaper delivery route for The Kansas City Star and Kansas City Times. Disney and his brother Roy woke up at 4:30 every morning to deliver the Times before school and repeated the round for the evening Star after school. The schedule was exhausting, and Disney often received poor grades after falling asleep in class, but he continued his paper route for more than six years.[16] He attended Saturday courses at the Kansas City Art Institute and also took a correspondence course in cartooning.[5][17]

In 1917, Elias bought stock in a Chicago jelly producer, the O-Zell Company, and moved back to the city with his family.[18] Disney enrolled at McKinley High School and became the cartoonist of the school newspaper, drawing patriotic pictures about World War I;[19][20] he also took night courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.[21] In mid-1918, he attempted to join the United States Army to fight the Germans, but he was rejected as too young. After forging the date of birth on his birth certificate, he joined the Red Cross in September 1918 as an ambulance driver. He was shipped to France but arrived in November, after the armistice.[22] He drew cartoons on the side of his ambulance for decoration and had some of his work published in the army newspaper Stars and Stripes.[23] He returned to Kansas City in October 1919,[24] where he worked as an apprentice artist at the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio, where he drew commercial illustrations for advertising, theater programs and catalogs, and befriended fellow artist Ub Iwerks.[25]

Career

Early career: 1920–1928

Walt Disney’s business envelope featured a self-portrait, c. 1921.

In January 1920, as Pesmen-Rubin’s revenue declined after Christmas, Disney, aged 18, and Iwerks were laid off. They started their own business, the short-lived Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists.[26] Failing to attract many customers, Disney and Iwerks agreed that Disney should leave temporarily to earn money at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, run by A. V. Cauger; the following month Iwerks, who was not able to run their business alone, also joined.[27] The company produced commercials using the cutout animation technique.[28] Disney became interested in animation, although he preferred drawn cartoons such as Mutt and Jeff and Max Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell. With the assistance of a borrowed book on animation and a camera, he began experimenting at home.[29][c] He came to the conclusion that cel animation was more promising than the cutout method.[d] Unable to persuade Cauger to try cel animation at the company, Disney opened a new business with a co-worker from the Film Ad Co, Fred Harman.[31] Their main client was the local Newman Theater, and the short cartoons they produced were sold as «Newman’s Laugh-O-Grams».[32] Disney studied Paul Terry’s Aesop’s Fables as a model, and the first six «Laugh-O-Grams» were modernized fairy tales.[33]

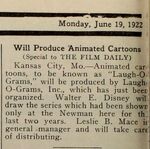

Newman Laugh-O-Gram (1921)

In May 1921, the success of the «Laugh-O-Grams» led to the establishment of Laugh-O-Gram Studio, for which he hired more animators, including Fred Harman’s brother Hugh, Rudolf Ising and Iwerks.[34] The Laugh-O-Grams cartoons did not provide enough income to keep the company solvent, so Disney started production of Alice’s Wonderland—based on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—which combined live action with animation; he cast Virginia Davis in the title role.[35] The result, a 12-and-a-half-minute, one-reel film, was completed too late to save Laugh-O-Gram Studio, which went into bankruptcy in 1923.[36]

Disney moved to Hollywood in July 1923 at 21 years old. Although New York was the center of the cartoon industry, he was attracted to Los Angeles because his brother Roy was convalescing from tuberculosis there,[37] and he hoped to become a live-action film director.[38] Disney’s efforts to sell Alice’s Wonderland were in vain until he heard from New York film distributor Margaret J. Winkler. She was losing the rights to both the Out of the Inkwell and Felix the Cat cartoons, and needed a new series. In October, they signed a contract for six Alice comedies, with an option for two further series of six episodes each.[38][39] Disney and his brother Roy formed the Disney Brothers Studio—which later became The Walt Disney Company—to produce the films;[40][41] they persuaded Davis and her family to relocate to Hollywood to continue production, with Davis on contract at $100 a month. In July 1924, Disney also hired Iwerks, persuading him to relocate to Hollywood from Kansas City.[42]

In 1926,[43] the first official Walt Disney Studio was established at 2725 Hyperion Avenue, demolished in 1940.[44]

By 1926, Winkler’s role in the distribution of the Alice series had been handed over to her husband, the film producer Charles Mintz, although the relationship between him and Disney was sometimes strained.[45] The series ran until July 1927,[46] by which time Disney had begun to tire of it and wanted to move away from the mixed format to all animation.[45][47] After Mintz requested new material to distribute through Universal Pictures, Disney and Iwerks created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a character Disney wanted to be «peppy, alert, saucy and venturesome, keeping him also neat and trim».[47][48]

In February 1928, Disney hoped to negotiate a larger fee for producing the Oswald series, but found Mintz wanting to reduce the payments. Mintz had also persuaded many of the artists involved to work directly for him, including Harman, Ising, Carman Maxwell and Friz Freleng. Disney also found out that Universal owned the intellectual property rights to Oswald. Mintz threatened to start his own studio and produce the series himself if Disney refused to accept the reductions. Disney declined Mintz’s ultimatum and lost most of his animation staff, except Iwerks, who chose to remain with him.[49][50][e]

Creation of Mickey Mouse to the first Academy Awards: 1928–1933

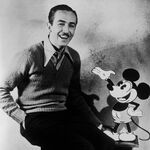

To replace Oswald, Disney and Iwerks developed Mickey Mouse, possibly inspired by a pet mouse that Disney had adopted while working in his Laugh-O-Gram studio, although the origins of the character are unclear.[52][f] Disney’s original choice of name was Mortimer Mouse, but his wife Lillian thought it too pompous, and suggested Mickey instead.[53][g] Iwerks revised Disney’s provisional sketches to make the character easier to animate. Disney, who had begun to distance himself from the animation process,[55] provided Mickey’s voice until 1947. In the words of one Disney employee, «Ub designed Mickey’s physical appearance, but Walt gave him his soul.»[56]

Mickey Mouse first appeared in May 1928 as a single test screening of the short Plane Crazy, but it, and the second feature, The Gallopin’ Gaucho, failed to find a distributor.[57] Following the 1927 sensation The Jazz Singer, Disney used synchronized sound on the third short, Steamboat Willie, to create the first post-produced sound cartoon. After the animation was complete, Disney signed a contract with the former executive of Universal Pictures, Pat Powers, to use the «Powers Cinephone» recording system;[58] Cinephone became the new distributor for Disney’s early sound cartoons, which soon became popular.[59]

To improve the quality of the music, Disney hired the professional composer and arranger Carl Stalling, on whose suggestion the Silly Symphony series was developed, providing stories through the use of music; the first in the series, The Skeleton Dance (1929), was drawn and animated entirely by Iwerks. Also hired at this time were several local artists, some of whom stayed with the company as core animators; the group later became known as the Nine Old Men.[60][h] Both the Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies series were successful, but Disney and his brother felt they were not receiving their rightful share of profits from Powers. In 1930, Disney tried to trim costs from the process by urging Iwerks to abandon the practice of animating every separate cel in favor of the more efficient technique of drawing key poses and letting lower-paid assistants sketch the inbetween poses. Disney asked Powers for an increase in payments for the cartoons. Powers refused and signed Iwerks to work for him; Stalling resigned shortly afterwards, thinking that without Iwerks, the Disney Studio would close.[61] Disney had a nervous breakdown in October 1931—which he blamed on the machinations of Powers and his own overwork—so he and Lillian took an extended holiday to Cuba and a cruise to Panama to recover.[62]

Disney in 1935 in Place de la Concorde, Paris

With the loss of Powers as distributor, Disney studios signed a contract with Columbia Pictures to distribute the Mickey Mouse cartoons, which became increasingly popular, including internationally.[63][64][i] Disney and his crew would also introduce new cartoon stars like Pluto in 1930, Goofy in 1932 and Donald Duck in 1934.[65] Always keen to embrace new technology and encouraged by his new contract with United Artists, Disney filmed Flowers and Trees (1932) in full-color three-strip Technicolor;[66] he was also able to negotiate a deal giving him the sole right to use the three-strip process until August 31, 1935.[67] All subsequent Silly Symphony cartoons were in color.[68] Flowers and Trees was popular with audiences[69] and won the inaugural Academy Award for best Short Subject (Cartoon) at the 1932 ceremony. Disney had been nominated for another film in that category, Mickey’s Orphans, and received an Honorary Award «for the creation of Mickey Mouse».[70][71]

In 1933, Disney produced The Three Little Pigs, a film described by the media historian Adrian Danks as «the most successful short animation of all time».[72] The film won Disney another Academy Award in the Short Subject (Cartoon) category. The film’s success led to a further increase in the studio’s staff, which numbered nearly 200 by the end of the year.[73] Disney realized the importance of telling emotionally gripping stories that would interest the audience,[74] and he invested in a «story department» separate from the animators, with storyboard artists who would detail the plots of Disney’s films.[75]

Golden age of animation: 1934–1941

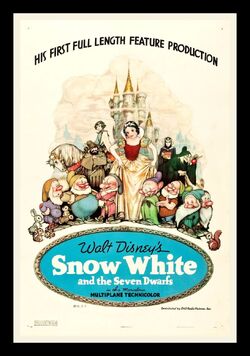

Walt Disney introduces each of the seven dwarfs in a scene from the original 1937 Snow White theatrical trailer.

By 1934, Disney had become dissatisfied with producing formulaic cartoon shorts,[65] and believed a feature-length cartoon would be more profitable.[76] The studio began the four-year production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, based on the fairy tale. When news leaked out about the project, many in the film industry predicted it would bankrupt the company; industry insiders nicknamed it «Disney’s Folly».[77] The film, which was the first animated feature made in full color and sound, cost $1.5 million to produce—three times over budget.[78] To ensure the animation was as realistic as possible, Disney sent his animators on courses at the Chouinard Art Institute;[79] he brought animals into the studio and hired actors so that the animators could study realistic movement.[80] To portray the changing perspective of the background as a camera moved through a scene, Disney’s animators developed a multiplane camera which allowed drawings on pieces of glass to be set at various distances from the camera, creating an illusion of depth. The glass could be moved to create the impression of a camera passing through the scene. The first work created on the camera—a Silly Symphony called The Old Mill (1937)—won the Academy Award for Animated Short Film because of its impressive visual power. Although Snow White had been largely finished by the time the multiplane camera had been completed, Disney ordered some scenes be re-drawn to use the new effects.[81]

Snow White premiered in December 1937 to high praise from critics and audiences. The film became the most successful motion picture of 1938 and by May 1939 its total gross of $6.5 million made it the most successful sound film made to that date.[77][j] Disney won another Honorary Academy Award, which consisted of one full-sized and seven miniature Oscar statuettes.[83][k] The success of Snow White heralded one of the most productive eras for the studio; the Walt Disney Family Museum calls the following years «the ‘Golden Age of Animation’ ».[84][85] With work on Snow White finished, the studio began producing Pinocchio in early 1938 and Fantasia in November of the same year. Both films were released in 1940, and neither performed well at the box office—partly because revenues from Europe had dropped following the start of World War II in 1939. The studio made a loss on both pictures and was deeply in debt by the end of February 1941.[86]

In response to the financial crisis, Disney and his brother Roy started the company’s first public stock offering in 1940, and implemented heavy salary cuts. The latter measure, and Disney’s sometimes high-handed and insensitive manner of dealing with staff, led to a 1941 animators’ strike which lasted five weeks.[87] While a federal mediator from the National Labor Relations Board negotiated with the two sides, Disney accepted an offer from the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs to make a goodwill trip to South America, ensuring he was absent during a resolution he knew would be unfavorable to the studio.[88][l] As a result of the strike—and the financial state of the company—several animators left the studio, and Disney’s relationship with other members of staff was permanently strained as a result.[91] The strike temporarily interrupted the studio’s next production, Dumbo (1941), which Disney produced in a simple and inexpensive manner; the film received a positive reaction from audiences and critics alike.[92]

World War II and beyond: 1941–1950

Disney drawing Goofy for a group of girls in Argentina, 1941

Shortly after the release of Dumbo in October 1941, the U.S. entered World War II. Disney formed the Walt Disney Training Films Unit within the company to produce instruction films for the military such as Four Methods of Flush Riveting and Aircraft Production Methods.[93] Disney also met with Henry Morgenthau Jr., the Secretary of the Treasury, and agreed to produce short Donald Duck cartoons to promote war bonds.[94] Disney also produced several propaganda productions, including shorts such as Der Fuehrer’s Face—which won an Academy Award—and the 1943 feature film Victory Through Air Power.[95]

The military films generated only enough revenue to cover costs, and the feature film Bambi—which had been in production since 1937—underperformed on its release in April 1942, and lost $200,000 at the box office.[96] On top of the low earnings from Pinocchio and Fantasia, the company had debts of $4 million with the Bank of America in 1944.[97][m] At a meeting with Bank of America executives to discuss the future of the company, the bank’s chairman and founder, Amadeo Giannini, told his executives, «I’ve been watching the Disneys’ pictures quite closely because I knew we were lending them money far above the financial risk. … They’re good this year, they’re good next year, and they’re good the year after. … You have to relax and give them time to market their product.»[98] Disney’s production of short films decreased in the late 1940s, coinciding with increasing competition in the animation market from Warner Bros. and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Roy Disney, for financial reasons, suggested more combined animation and live-action productions.[58][n] In 1948, Disney initiated a series of popular live-action nature films, titled True-Life Adventures, with Seal Island the first; the film won the Academy Award in the Best Short Subject (Two-Reel) category.[99]

Theme parks, television and other interests: 1950–1966

In early 1950, Disney produced Cinderella, his studio’s first animated feature in eight years. It was popular with critics and theater audiences. Costing $2.2 million to produce, it earned nearly $8 million in its first year.[100][o] Disney was less involved than he had been with previous pictures because of his involvement in his first entirely live-action feature, Treasure Island (1950), which was shot in Britain, as was The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952).[101] Other all-live-action features followed, many of which had patriotic themes.[58][p] He continued to produce full-length animated features too, including Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953). From the early to mid-1950s, Disney began to devote less attention to the animation department, entrusting most of its operations to his key animators, the Nine Old Men, although he was always present at story meetings. Instead, he started concentrating on other ventures.[102] Around the same time, Disney would establish his own film distribution chain Buena Vista, replacing his most recent distributor RKO Pictures.[103]

For several years Disney had been considering building a theme park. When he visited Griffith Park in Los Angeles with his daughters, he wanted to be in a clean, unspoiled park, where both children and their parents could have fun.[104] He visited the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Denmark, and was heavily influenced by the cleanliness and layout of the park.[105] In March 1952 he received zoning permission to build a theme park in Burbank, near the Disney studios.[106] This site proved too small, and a larger plot in Anaheim, 35 miles (56 km) south of the studio, was purchased. To distance the project from the studio—which might attract the criticism of shareholders—Disney formed WED Enterprises (now Walt Disney Imagineering) and used his own money to fund a group of designers and animators to work on the plans;[107][108] those involved became known as «Imagineers».[109] After obtaining bank funding he invited other stockholders, American Broadcasting-Paramount Theatres—part of American Broadcasting Company (ABC)—and Western Printing and Lithographing Company.[58] In mid-1954, Disney sent his Imagineers to every amusement park in the U.S. to analyze what worked and what pitfalls or problems there were in the various locations and incorporated their findings into his design.[110] Construction work started in July 1954, and Disneyland opened in July 1955; the opening ceremony was broadcast on ABC, which reached 70 million viewers.[111] The park was designed as a series of themed lands, linked by the central Main Street, U.S.A.—a replica of the main street in his hometown of Marceline. The connected themed areas were Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland and Tomorrowland. The park also contained the narrow gauge Disneyland Railroad that linked the lands; around the outside of the park was a high berm to separate the park from the outside world.[112][113] An editorial in The New York Times considered that Disney had «tastefully combined some of the pleasant things of yesterday with fantasy and dreams of tomorrow».[114] Although there were early minor problems with the park, it was a success, and after a month’s operation, Disneyland was receiving over 20,000 visitors a day; by the end of its first year, it attracted 3.6 million guests.[115]

The money from ABC was contingent on Disney television programs.[116] The studio had been involved in a successful television special on Christmas Day 1950 about the making of Alice in Wonderland. Roy believed the program added millions to the box office takings. In a March 1951 letter to shareholders, he wrote that «television can be a most powerful selling aid for us, as well as a source of revenue. It will probably be on this premise that we enter television when we do».[58] In 1954, after the Disneyland funding had been agreed, ABC broadcast Walt Disney’s Disneyland, an anthology consisting of animated cartoons, live-action features and other material from the studio’s library. The show was successful in terms of ratings and profits, earning an audience share of over 50%.[117][q] In April 1955, Newsweek called the series an «American institution».[118] ABC was pleased with the ratings, leading to Disney’s first daily television program, The Mickey Mouse Club, a variety show catering specifically to children.[119] The program was accompanied by merchandising through various companies (Western Printing, for example, had been producing coloring books and comics for over 20 years, and produced several items connected to the show).[120] One of the segments of Disneyland consisted of the five-part miniseries Davy Crockett which, according to Gabler, «became an overnight sensation».[121] The show’s theme song, «The Ballad of Davy Crockett», became internationally popular, and ten million records were sold.[122] As a result, Disney formed his own record production and distribution entity, Disneyland Records.[123]

As well as the construction of Disneyland, Disney worked on other projects away from the studio. He was consultant to the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow; Disney Studios’ contribution was America the Beautiful, a 19-minute film in the 360-degree Circarama theater that was one of the most popular attractions.[58] The following year he acted as the chairman of the Pageantry Committee for the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley, California, where he designed the opening, closing and medal ceremonies.[124] He was one of twelve investors in the Celebrity Sports Center, which opened in 1960 in Glendale, Colorado; he and Roy bought out the others in 1962, making the Disney company the sole owner.[125]

Despite the demands wrought by non-studio projects, Disney continued to work on film and television projects. In 1955, he was involved in «Man in Space», an episode of the Disneyland series, which was made in collaboration with NASA rocket designer Wernher von Braun.[r] Disney also oversaw aspects of the full-length features Lady and the Tramp (the first animated film in CinemaScope) in 1955, Sleeping Beauty (the first animated film in Technirama 70 mm film) in 1959, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (the first animated feature film to use Xerox cels) in 1961, and The Sword in the Stone in 1963.[127]

In 1964, Disney produced Mary Poppins, based on the book series by P. L. Travers; he had been trying to acquire the rights to the story since the 1940s.[128] It became the most successful Disney film of the 1960s, although Travers disliked the film intensely and regretted having sold the rights.[129] The same year he also became involved in plans to expand the California Institute of the Arts (colloquially called CalArts), and had an architect draw up blueprints for a new building.[130]

Disney provided four exhibits for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, for which he obtained funding from selected corporate sponsors. For PepsiCo, who planned a tribute to UNICEF, Disney developed It’s a Small World, a boat ride with audio-animatronic dolls depicting children of the world; Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln contained an animatronic Abraham Lincoln giving excerpts from his speeches; Carousel of Progress promoted the importance of electricity; and Ford’s Magic Skyway portrayed the progress of mankind. Elements of all four exhibits—principally concepts and technology—were re-installed in Disneyland, although It’s a Small World is the ride that most closely resembles the original.[131][132]

During the early to mid-1960s, Disney developed plans for a ski resort in Mineral King, a glacial valley in California’s Sierra Nevada. He hired experts such as the renowned Olympic ski coach and ski-area designer Willy Schaeffler.[133][134][s] With income from Disneyland accounting for an increasing proportion of the studio’s income, Disney continued to look for venues for other attractions. In 1963 he presented a project to create a theme park in downtown St. Louis, Missouri; he initially reached an agreement with the Civic Center Redevelopment Corp, which controlled the land, but the deal later collapsed over funding.[136][137] In late 1965, he announced plans to develop another theme park to be called «Disney World» (now Walt Disney World), a few miles southwest of Orlando, Florida. Disney World was to include the «Magic Kingdom»—a larger and more elaborate version of Disneyland—plus golf courses and resort hotels. The heart of Disney World was to be the «Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow» (EPCOT),[138] which he described as:

an experimental prototype community of tomorrow that will take its cue from the new ideas and new technologies that are now emerging from the creative centers of American industry. It will be a community of tomorrow that will never be completed, but will always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and systems. And EPCOT will always be a showcase to the world for the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise.[139]

During 1966, Disney cultivated businesses willing to sponsor EPCOT.[140] He received a story credit in the 1966 film Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. as Retlaw Yensid, his name spelt backwards.[141] He increased his involvement in the studio’s films, and was heavily involved in the story development of The Jungle Book, the live-action musical feature The Happiest Millionaire (both 1967) and the animated short Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day (1968).[142]

Illness, death and aftermath

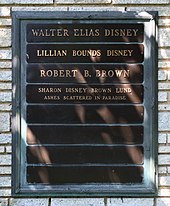

Grave of Walt Disney at Forest Lawn, Glendale

Disney had been a heavy smoker since World War I. He did not use cigarettes with filters and had smoked a pipe as a young man. In early November 1966, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and was treated with cobalt therapy.[143] On November 30, he felt unwell and was taken by ambulance from his home to St. Joseph Hospital where, on December 15, 1966, aged 65, he died of circulatory collapse caused by the cancer.[144] His remains were cremated two days later and his ashes interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.[145][t]

The release of The Jungle Book and The Happiest Millionaire in 1967 raised the total number of feature films that Disney had been involved in to 81.[19] When Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day was released in 1968, it earned Disney an Academy Award in the Short Subject (Cartoon) category, awarded posthumously.[149] After Disney’s death, his studios continued to produce live-action films prolifically but largely abandoned animation until the late 1980s, after which there was what The New York Times describes as the «Disney Renaissance» that began with The Little Mermaid (1989).[150] Disney’s companies continue to produce successful film, television and stage entertainment.[151]

Disney’s plans for the futuristic city of EPCOT did not come to fruition. After Disney’s death, his brother Roy deferred his retirement to take full control of the Disney companies. He changed the focus of the project from a town to an attraction.[152] At the inauguration in 1971, Roy dedicated Walt Disney World to his brother.[153][u] Walt Disney World expanded with the opening of Epcot Center in 1982; Walt Disney’s vision of a functional city was replaced by a park more akin to a permanent world’s fair.[155] In 2009, the Walt Disney Family Museum, designed by Disney’s daughter Diane and her son Walter E. D. Miller, opened in the Presidio of San Francisco.[156] Thousands of artifacts from Disney’s life and career are on display, including numerous awards that he received.[157] In 2014, the Disney theme parks around the world hosted approximately 134 million visitors.[158]

Personal life and character

Early in 1925, Disney hired an ink artist, Lillian Bounds. They married in July of that year, at her brother’s house in her hometown of Lewiston, Idaho.[159] The marriage was generally happy, according to Lillian, although according to Disney’s biographer Neal Gabler she did not «accept Walt’s decisions meekly or his status unquestionably, and she admitted that he was always telling people ‘how henpecked he is’.»[160][v] Lillian had little interest in films or the Hollywood social scene and she was, in the words of the historian Steven Watts, «content with household management and providing support for her husband».[161] Their marriage produced two daughters, Diane (born December 1933) and Sharon (adopted in December 1936, born six weeks previously).[162][w] Within the family, neither Disney nor his wife hid the fact Sharon had been adopted, although they became annoyed if people outside the family raised the point.[163] The Disneys were careful to keep their daughters out of the public eye as much as possible, particularly in the light of the Lindbergh kidnapping; Disney took steps to ensure his daughters were not photographed by the press.[164]

Disney family at Schiphol Airport (1951)

In 1949, Disney and his family moved to a new home in the Holmby Hills district of Los Angeles. With the help of his friends Ward and Betty Kimball, who already had their own backyard railroad, Disney developed blueprints and immediately set to work on creating a miniature live steam railroad for his backyard. The name of the railroad, Carolwood Pacific Railroad, came from his home’s location on Carolwood Drive. The miniature working steam locomotive was built by Disney Studios engineer Roger E. Broggie, and Disney named it Lilly Belle after his wife;[165] after three years Disney ordered it into storage due to a series of accidents involving his guests.[166]

Disney grew more politically conservative as he got older. A Democratic Party supporter until the 1940 presidential election, when he switched allegiance to the Republican Party,[167] he became a generous donor to Thomas E. Dewey’s 1944 bid for the presidency.[168] In 1946, he was a founding member of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, an organization who stated they «believ[ed] in, and like, the American Way of Life … we find ourselves in sharp revolt against a rising tide of Communism, Fascism and kindred beliefs, that seek by subversive means to undermine and change this way of life».[169] In 1947, during the Second Red Scare, Disney testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), where he branded Herbert Sorrell, David Hilberman and William Pomerance, former animators and labor union organizers, as communist agitators; Disney stated that the 1941 strike led by them was part of an organized communist effort to gain influence in Hollywood.[170][171] It was alleged by The New York Times in 1993 that Disney had been passing secret information to the FBI from 1940 until his death in 1966. In return for this information, J. Edgar Hoover allowed Disney to film in FBI headquarters in Washington. Disney was made a «full Special Agent in Charge Contact» in 1954.[172]

Disney’s public persona was very different from his actual personality.[173] Playwright Robert E. Sherwood described him as «almost painfully shy … diffident» and self-deprecating.[174] According to his biographer Richard Schickel, Disney hid his shy and insecure personality behind his public identity.[175] Kimball argues that Disney «played the role of a bashful tycoon who was embarrassed in public» and knew that he was doing so.[176] Disney acknowledged the façade and told a friend that «I’m not Walt Disney. I do a lot of things Walt Disney would not do. Walt Disney does not smoke. I smoke. Walt Disney does not drink. I drink.»[177] Critic Otis Ferguson, in The New Republic, called the private Disney: «common and everyday, not inaccessible, not in a foreign language, not suppressed or sponsored or anything. Just Disney.»[176] Many of those with whom Disney worked commented that he gave his staff little encouragement due to his exceptionally high expectations. Norman recalls that when Disney said «That’ll work», it was an indication of high praise.[178] Instead of direct approval, Disney gave high-performing staff financial bonuses, or recommended certain individuals to others, expecting that his praise would be passed on.[179]

Reputation

Views of Disney and his work have changed over the decades, and there have been polarized opinions.[180] Mark Langer, in the American Dictionary of National Biography, writes that «Earlier evaluations of Disney hailed him as a patriot, folk artist, and popularizer of culture. More recently, Disney has been regarded as a paradigm of American imperialism and intolerance, as well as a debaser of culture.»[58] Steven Watts wrote that some denounce Disney «as a cynical manipulator of cultural and commercial formulas»,[180] while PBS records that critics have censured his work because of its «smooth façade of sentimentality and stubborn optimism, its feel-good re-write of American history».[181]

Disney has been accused of anti-Semitism for having given Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl a tour of his studio a month after Kristallnacht,[182] something he disavowed three months later claiming he was unaware who she was when he was issued the invitation.[183][x] None of Disney’s employees—including the animator Art Babbitt, who disliked Disney intensely—ever accused him of making anti-Semitic slurs or taunts.[185] The Walt Disney Family Museum acknowledges that ethnic stereotypes common to films of the 1930s were included in some early cartoons[y] but also points out that Disney donated regularly to Jewish charities, was named «1955 Man of the Year» by the B’nai B’rith chapter in Beverly Hills,[188][189] and his studio employed a number of Jews, some of whom were in influential positions.[190][z] Gabler, the first writer to gain unrestricted access to the Disney archives, concludes that the available evidence does not support accusations of anti-Semitism and that Disney was «not [anti-Semitic] in the conventional sense that we think of someone as being an anti-Semite». Gabler concludes that «though Walt himself, in my estimation, was not anti-Semitic, nevertheless, he willingly allied himself with people who were anti-Semitic [meaning some members of the MPAPAI], and that reputation stuck. He was never really able to expunge it throughout his life».[192] Disney distanced himself from the Motion Picture Alliance in the 1950s.[193] According to Disney’s daughter Diane Disney-Miller, her sister Sharon dated a Jewish boyfriend for a period of time- to which her father raised no objections and even reportedly said «Sharon, I think it’s wonderful how these Jewish families have accepted you.»[186]

Disney has also been accused of other forms of racism because some of his productions released between the 1930s and 1950s contain racially insensitive material.[194][aa] The feature film Song of the South was criticized by contemporary film critics, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and others for its perpetuation of black stereotypes,[195] but Disney later campaigned successfully for an Honorary Academy Award for its star, James Baskett, the first black actor so honored.[196][ab] Gabler argues that «Walt Disney was no racist. He never, either publicly or privately, made disparaging remarks about blacks or asserted white superiority. Like most white Americans of his generation, however, he was racially insensitive.»[194] Floyd Norman, the studio’s first black animator who worked closely with Disney during the 1950s and 1960s, said, «Not once did I observe a hint of the racist behavior Walt Disney was often accused of after his death. His treatment of people—and by this I mean all people—can only be called exemplary.»[197]

Watts argues that many of Disney’s post-World War II films «legislated a kind of cultural Marshall Plan. They nourished a genial cultural imperialism that magically overran the rest of the globe with the values, expectations, and goods of a prosperous middle-class United States.»[198] Film historian Jay P. Telotte acknowledges that many see Disney’s studio as an «agent of manipulation and repression», although he observes that it has «labored throughout its history to link its name with notions of fun, family, and fantasy».[199] John Tomlinson, in his study Cultural Imperialism, examines the work of Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, whose 1971 book Para leer al Pato Donald (trans: How to Read Donald Duck) identifies that there are «imperialist … values ‘concealed’ behind the innocent, wholesome façade of the world of Walt Disney»; this, they argue, is a powerful tool as «it presents itself as harmless fun for consumption by children.»[200] Tomlinson views their argument as flawed, as «they simply assume that reading American comics, seeing adverts, watching pictures of the affluent … [‘Yankee’] lifestyle has a direct pedagogic effect».[201]

Disney has been portrayed numerous times in fictional works. H. G. Wells references Disney in his 1938 novel The Holy Terror, in which World Dictator Rud fears that Donald Duck is meant to lampoon the dictator.[202] Disney was portrayed by Len Cariou in the 1995 made-for-TV film A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes: The Annette Funicello Story,[203] and by Tom Hanks in the 2013 film Saving Mr. Banks.[204] In 2001, the German author Peter Stephan Jungk published Der König von Amerika (trans: The King of America), a fictional work of Disney’s later years that re-imagines him as a power-hungry racist. The composer Philip Glass later adapted the book into the opera The Perfect American (2013).[205]

Several commentators have described Disney as a cultural icon.[206] On Disney’s death, journalism professor Ralph S. Izard comments that the values in Disney’s films are those «considered valuable in American Christian society», which include «individualism, decency, … love for our fellow man, fair play and toleration».[207] Disney’s obituary in The Times calls the films «wholesome, warm-hearted and entertaining … of incomparable artistry and of touching beauty».[208] Journalist Bosley Crowther argues that Disney’s «achievement as a creator of entertainment for an almost unlimited public and as a highly ingenious merchandiser of his wares can rightly be compared to the most successful industrialists in history.»[5] Correspondent Alistair Cooke calls Disney a «folk-hero … the Pied Piper of Hollywood»,[209] while Gabler considers Disney «reshaped the culture and the American consciousness».[210] In the American Dictionary of National Biography, Langer writes:

Disney remains the central figure in the history of animation. Through technological innovations and alliances with governments and corporations, he transformed a minor studio in a marginal form of communication into a multinational leisure industry giant. Despite his critics, his vision of a modern, corporate utopia as an extension of traditional American values has possibly gained greater currency in the years after his death.[58]

In December 2021, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened a three month special exhibit in honor of Disney titled «Inspiring Walt Disney».[211]

Awards and honors

Disney received 59 Academy Award nominations, including 22 awards: both totals are records.[212] He was nominated for three Golden Globe Awards, but did not win, but he was presented with two Special Achievement Awards—for Bambi (1942) and The Living Desert (1953)—and the Cecil B. DeMille Award.[213] He also received four Emmy Award nominations, winning once, for Best Producer for the Disneyland television series.[214] Several of his films are included in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant»: Steamboat Willie, The Three Little Pigs, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Pinocchio, Bambi, Dumbo and Mary Poppins.[215] In 1998, the American Film Institute published a list of the 100 greatest American films, according to industry experts; the list included Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (at number 49), and Fantasia (at 58).[216]

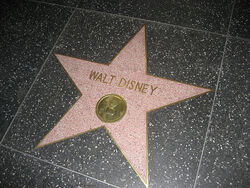

In February 1960, Disney was inducted to the Hollywood Walk of Fame with two stars, one for motion pictures and the other for his television work;[217] Mickey Mouse was given his own star for motion pictures in 1978.[218] Disney was also inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1986,[219] the California Hall of Fame in December 2006,[220] and was the inaugural recipient of a star on the Anaheim walk of stars in 2014.[221]

The Walt Disney Family Museum records that he «along with members of his staff, received more than 950 honors and citations from throughout the world».[19] He was made a Chevalier in the French Légion d’honneur in 1935,[222] and in 1952 he was awarded the country’s highest artistic decoration, the Officer d’Academie.[223] Other national awards include Thailand’s Order of the Crown (1960); Germany’s Order of Merit (1956),[224] Brazil’s Order of the Southern Cross (1941),[225] and Mexico’s Order of the Aztec Eagle (1943).[226] In the United States, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom on September 14, 1964,[227] and on May 24, 1968, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.[228] He received the Showman of the World Award from the National Association of Theatre Owners,[226] and in 1955, the National Audubon Society awarded Disney its highest honor, the Audubon Medal, for promoting the «appreciation and understanding of nature» through his True-Life Adventures nature films.[229] A minor planet discovered in 1980 by astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina, was named 4017 Disneya,[230] and he was also awarded honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale, the University of Southern California and the University of California, Los Angeles.[19]

Notes

- ^ In 1909, in a renumbering exercise, the property’s address changed to 2156 North Tripp Avenue.[3]

- ^ Disney was a descendant of Robert d’Isigny, a Frenchman who had traveled to England with William the Conqueror in 1066.[6] The family anglicized the d’Isigny name to «Disney» and settled in the English village now known as Norton Disney in the East Midlands.[7]

- ^ The book, Edwin G. Lutz’s Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development (1920), was the only one in the local library on the subject; the camera he borrowed from Cauger.[29]

- ^ Cutout animation is the technique of producing cartoons by animating objects cut from paper, material or photographs and photographing them moving incrementally. Cel animation is the method of drawing or painting onto transparent celluloid sheets («cels»), with each sheet an incremental movement on from the previous.[30]

- ^ In 2006, the Walt Disney Company finally re-acquired Oswald the Lucky Rabbit when its subsidiary ESPN purchased rights to the character, along with other properties from NBCUniversal.[51]

- ^ Several stories about the origins exist. Disney’s biographer, Bob Thomas, observes that «The birth of Mickey Mouse is obscured in legend, much of it created by Walt Disney himself.»[52]

- ^ The name Mortimer Mouse was used in the 1936 cartoon Mickey’s Rival as a potential love-interest for Minnie Mouse. He was portrayed as a «humorous denigration of the smooth city slicker» with a smart car, but failed to win over Minnie from the more homespun Mickey.[54]

- ^ The Nine Old Men consisted of Eric Larson, Wolfgang Reitherman, Les Clark, Milt Kahl, Ward Kimball, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Frank Thomas and John Lounsbery.[58]

- ^ By 1931 he was called Michael Maus in Germany, Michel Souris in France, Miguel Ratonocito or Miguel Pericote in Spain and Miki Kuchi in Japan.[63]

- ^ $1.5 million in 1937 equates to $28,274,306 in 2023; $6.5 million in 1939 equates to $126,929,257 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[82]

- ^ The citation for the award reads: «To Walt Disney for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, recognized as a significant screen innovation which has charmed millions and pioneered a great new entertainment field for the motion picture cartoon.»[83]

- ^ The trip inspired two combined live-action and animation works Saludos Amigos (1942) and The Three Caballeros (1945).[89][90]

- ^ $4 million in 1944 equates to $61,572,779 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[82]

- ^ These included Make Mine Music (1946), Song of the South (1946), Melody Time (1948) and So Dear to My Heart (1949).[58]

- ^ $2.2 million in 1950 equates to $24,778,147 in 2023; $8 million in 1950 equates to $90,102,351 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[82]

- ^ The patriotic films include Johnny Tremain (1957), Old Yeller (1957), Tonka (1958), Swiss Family Robinson (1960), Polyanna (1960).[58]

- ^ Even repeats of the program proved more popular than all other television shows—aside from Lucille Ball’s I Love Lucy; no ABC program had ever been in the top 25 before Disneyland.[117]

- ^ The program, which was produced by Ward Kimball, was nominated for an Academy Award for the Best Documentary (Short Subject) at the 1957 Awards.[126]

- ^ Disney’s death in 1966, and opposition from conservationists, stopped the building of the resort.[135]

- ^ A long-standing urban legend maintains that Disney was cryonically frozen.[146] Disney’s daughter Diane later stated, «There is absolutely no truth to the rumor that my father, Walt Disney, wished to be frozen.»[147][148]

- ^ Roy died two months later, in December 1971.[154]

- ^ One possible exception to the stable relationship was during the making Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), where the stresses and turmoil associated with the production led to the couple discussing divorce.[160]

- ^ Lillian had two miscarriages during the eight years between marriage and the birth of Diane; she suffered a further miscarriage shortly before the family adopted Sharon.[162]

- ^ Another example included animator Art Babbitt, an organizer of the 1941 strike at Disney’s studio, claimed in his later years that he saw Disney and his lawyer attend meetings of the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi organization, during the late 1930s.[184] Gabler questions Babbitt’s claim on the basis that Disney had no time for political meetings and was «something of a political naïf» during the 1930s.[185] Disney’s office appointment book makes no mention of him attending Bund rallies, and no other animators ever made claims of Disney attending such meetings.[186] Disney had previously told one reporter in the mid-1930s- as tensions in Europe were brewing- that America should «let ’em fight their own wars» claiming he had «learned my lesson» from the last one.[187]

- ^ Examples include The Three Little Pigs (in which the Big Bad Wolf comes to the door dressed as a Jewish peddler) and The Opry House (in which Mickey Mouse is dressed and dances as a Hasidic Jew).[188][189]

- ^ As pointed out by story artist Joe Grant, which included himself, production manager Harry Tytle, and head of merchandising Kay Kamen, who once quipped that Disney’s New York office had «more Jews than The Book of Leviticus»[190] In addition songwriter Robert B. Sherman recalled that when one of Disney’s lawyers made anti-Semitic remarks towards him and his brother, Disney defended them and fired the attorney.[191][186]

- ^ Examples include Mickey’s Mellerdrammer, in which Mickey Mouse dresses in blackface; the black-colored bird in the short Who Killed Cock Robin; the American Indians in Peter Pan; and the crows in Dumbo (although the case has been made that the crows were sympathetic to Dumbo because they knew what it was like to be ostracized).[194]

- ^ Baskett died shortly afterward, and his widow wrote Disney a letter of gratitude for his support.[196]

References

Citations

- ^ «Disney to Quit Post at Studio». Los Angeles Times. September 11, 1945.

- ^

«Definition of Disney, Walt in English». Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 8.

- ^

Rackl, Lori (September 27, 2009). «Walt Disney, the Man Behind the Mouse». Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved October 21, 2010. - ^ a b c d

Crowther, Bosley (April 27, 2015). «Walt Disney». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016. - ^ Mosley 1990, p. 22; Eliot 1995, p. 2.

- ^

Winter, Jon (April 12, 1997). «Uncle Walt’s Lost Ancestors». The Independent. London. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016. - ^ Barrier 2007, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 9–10, 15.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Broggie 2006, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Vintage Books. 2007. ISBN 9780679757474.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Krasniewicz 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Barrier 2007, pp. 18–19.

- ^

«Biography of Walt Disney (1901–1966), Film Producer». The Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d

«About Walt Disney». D23. The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016. - ^ Finch 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Mosley 1990, p. 39.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 36–38.

- ^

«Walt Disney, 65, Dies on Coast; Founded an Empire on a Mouse». The New York Times. December 16, 1966. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016. (subscription required) - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Thomas 1994, p. 56; Barrier 2007, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Mosley 1990, p. 63.

- ^ a b Thomas 1994, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Withrow 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 60–61, 64–66.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 71–73; Nichols 2014, p. 102.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 39.

- ^ a b Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 29.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 40.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 78.

- ^

«About the Walt Disney Company». The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2016. - ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 73–75.

- ^ «Disney Studios on Hyperion». Photo Collection. Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ «Demolition of Disney Hyperion Studios». Photo Collection. Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ a b

«Alice Hits the Skids». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2016. - ^

«The Final Alice Comedy Is Released». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2016. - ^ a b

Soteriou, Helen (December 3, 2012). «Could Oswald the Lucky Rabbit have been bigger than Mickey?». BBC News. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2016. - ^ Thomas 1994, p. 83.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 109.

- ^

«Secret Talks». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2016. - ^

«Stay ‘tooned: Disney gets ‘Oswald’ for Al Michaels». ESPN.com. February 10, 2006. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2016. - ^ a b Thomas 1994, p. 88.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 112.

- ^ Watts 2013, p. 73.

- ^ Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 39.

- ^

Solomon, Charles. «The Golden Age of Mickey Mouse». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on July 10, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Langer 2000.

- ^ Finch 1999, pp. 23–24; Gabler 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Finch 1999, pp. 26–27; Langer 2000.

- ^ Finch 1999, pp. 26–27; Gabler 2006, pp. 142–44.

- ^ Krasniewicz 2010, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b

«Regulated Rodent». Time. February 16, 1931. p. 21. - ^ Finch 1999, pp. 26–27; Gabler 2006, p. 142.

- ^ a b Thomas 1994, p. 129.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 178; Thomas 1994, p. 169.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 167; Gabler 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Barrier 2007, pp. 89–90.

- ^

«The 5th Academy Awards 1933». Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016. - ^

Danks, Adrian (December 2003). «Huffing and Puffing about Three Little Pigs». Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on April 22, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 184–86.

- ^ Lee & Madej 2012, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 186.

- ^ Thomas & Johnston 1995, p. 90.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 270.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 130; Finch 1999, p. 59.

- ^

Walt Disney: The Man Behind the Myth (Television production). The Walt Disney Family Foundation. January 17, 2015. Event occurs at 38:33–39:00. - ^

Walt Disney: An American Experience (Television production). PBS. September 14, 2015. Event occurs at 1:06:44 – 1:07:24. - ^ Williams, Denney & Denney 2004, p. 116.

- ^ a b c 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. «Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–». Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b

«The 11th Academy Awards 1939». Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2016. - ^

«The Golden Age of Animation». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2016. - ^ Krasniewicz 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 161–62; Barrier 2007, pp. 152, 162–63.

- ^ Ceplair & Englund 1983, p. 158; Thomas 1994, pp. 163–65; Barrier 1999, pp. 171–73.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 170–71; Gabler 2006, pp. 370–71.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 394–95.

- ^ Langer 2000; Gabler 2006, p. 378.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 71; Gabler 2006, pp. 380–81.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 184–85; Gabler 2006, pp. 382–83.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 384–85.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 77.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 399.

- ^

«The Disney Brothers Face a Fiscal Crisis». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on June 2, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2016. - ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 186–87.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 445–46.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 220.

- ^ Finch 1999, pp. 126–27; Barrier 2007, pp. 221–23.

- ^ Canemaker 2001, p. 110.

- ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 336–337.

- ^

«Dreaming of Disneyland». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on May 18, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2013. - ^

Walt Disney: The Man Behind the Myth (Television production). The Walt Disney Family Foundation. January 17, 2015. Event occurs at 1:10:00–1:13:00. - ^ Barrier 2007, pp. 233–34.

- ^

«The Beginning of WED». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2016. - ^

Mumford, David; Gordon, Bruce. «The Genesis of Disneyland». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2016. - ^ Finch 1999, p. 139.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 246.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 524, 530–32.

- ^ Eliot 1995, pp. 225–26.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 498.

- ^

«Topics of the Times». The New York Times. July 22, 1955. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016. (subscription required) - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 537.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 508–09.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 511.

- ^

«A Wonderful World: Growing Impact of Disney Art». Newsweek. April 18, 1955. p. 62. - ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 520–21.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 245.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 514.

- ^ Thomas 1994, p. 257.

- ^ Hollis & Ehrbar 2006, pp. 5–12, 20.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 566.

- ^ «Celebrity Sports Center: Bowling, video games, and your very first water slide». Denver Public Library. January 25, 2020.

- ^

«The 29th Academy Awards 1957». Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2016. - ^ Finch 1999, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Finch 1999, p. 130.

- ^

Singh, Anita (April 10, 2012). «Story of how Mary Poppins author regretted selling rights to Disney to be turned into film». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2016. - ^ Thomas 1994, p. 298.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 293.

- ^

Carnaham, Alyssa (June 26, 2012). «Look Closer: 1964 New York World’s Fair». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 621–23.

- ^

Meyers, Charlie (September 1988). «Ski Life». Ski. p. 26. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 631.

- ^ Nicklaus, David (May 8, 2013). «No, Disney didn’t spurn St. Louis over beer». St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Salter, Jim (December 7, 2015). «Walt Disney World was almost in St. Louis». Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 606–08.

- ^ Beard 1982, p. 11.

- ^ Thomas 1994, p. 307.

- ^ Broggie 2006, pp. 28.

- ^ Thomas 1994, p. 343; Barrier 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Markel, Howard (17 December 2018). «How a strange rumor of Walt Disney’s death became legend». PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 626–31.

- ^ Mosley 1990, p. 298.

- ^ Eliot 1995, p. 268.

- ^

Poyser, John (July 15, 2009). «Estate-planning lessons from the Magic Kingdom». Winnipeg Free Press. p. B5. - ^

Mikkelson, David (October 19, 1995). «Was Walt Disney Frozen?». Snopes. Retrieved June 15, 2020. - ^ Dobson 2009, p. 220.

- ^

Puig, Claudia (March 26, 2010). «‘Waking Sleeping Beauty’ documentary takes animated look at Disney renaissance». USA Today. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^

«History of The Walt Disney Studios» (PDF). The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016. - ^

Patches, Matt (May 20, 2015). «Inside Walt Disney’s Ambitious, Failed Plan to Build the City of Tomorrow». Esquire. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^

«Walt Disney World Resort: World History». Targeted News Service. March 18, 2009. - ^ Thomas 1994, pp. 357–58.

- ^

«News Update: EPCOT». AT&T Archives. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^

«About Us». The Walt Disney Family Museum. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014. - ^

Rothstein, Edward (September 30, 2009). «Exploring the Man Behind the Animation». The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2016. - ^

Dostis, Melanie (October 1, 2015). «13 things to know about the Disney parks on 44th anniversary of Walt Disney World». New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2016. - ^ «Walt Disney dies of cancer at 65». Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. December 16, 1966. p. 1.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 544.

- ^ Watts 2013, p. 352.

- ^ a b Barrier 2007, pp. 102, 131.

- ^ Mosley 1990, p. 169; Gabler 2006, p. 280.

- ^ Thomas 1994, p. 196; Watts 2013, p. 352.

- ^ Broggie 2006, pp. 7, 109.

- ^ Barrier 2007, p. 219.

- ^ Thomas 1994, p. 227.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 452.

- ^ Watts 2013, p. 240.

- ^

«Testimony of Walter E. Disney before HUAC». CNN. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 370.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (May 6, 1993). «Disney Link To the F.B.I. And Hoover Is Disclosed». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^

The Two Sides of Walt Disney (Television trailer). PBS. September 10, 2015. Event occurs at 0:08–0:13. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 204.

- ^ Schickel 1986, p. 341.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 205.

- ^

The Two Sides of Walt Disney (Television trailer). PBS. September 10, 2015. Event occurs at 0:14–0:25. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^ Norman 2013, p. 64.

- ^ Krasniewicz 2010, p. 77.

- ^ a b Watts 1995, p. 84.

- ^

«American Experience: Walt Disney». PBS. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016. - ^

Dargis, Manohla (September 21, 2011). «And Now a Word From the Director». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2011. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 499.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 448.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, pp. 448, 457.

- ^ a b c Korkis, Jim (November 20, 2017). «Debunking Myths About Walt Disney». www.mouseplanet.com. Mouseplanet. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Gabler 2006, pp. 449.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 456.

- ^ a b

«Creative Explosion: Walt’s Political Outlook». The Walt Disney Family Museum. p. 16. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2014. - ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 455.

- ^ Korkis, Jim (November 20, 2017). «Debunking Disney Urban Myths». cartoonresearch.com. Cartoon Research. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^

«Walt Disney: More Than ‘Toons, Theme Parks». CBS News. November 1, 2006. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. 611.

- ^ a b c Gabler 2006, p. 433.

- ^ Cohen 2004, p. 60.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, pp. 438–39.

- ^ Korkis 2012, p. xi.

- ^ Watts 1995, p. 107.

- ^ Telotte 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Tomlinson 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Tomlinson 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Pierce 1987, p. 100.

- ^

Scott, Tony (October 20, 1995). «Review: ‘Cbs Sunday Movie a Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes: The Annette Funicello Story’«. Variety. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016. - ^

Gettell, Oliver (December 18, 2013). «‘Saving Mr. Banks’ director: ‘Such an advantage’ shooting in L.A.» Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2014. - ^

Gritten, David (May 17, 2013). «Walt Disney: hero or villain?». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016. - ^ Mannheim 2016, p. 40; Krasniewicz 2010, p. xxii; Watts 2013, p. 58; Painter 2008, p. 25.

- ^

Izard, Ralph S. (July 1967). «Walt Disney: Master of Laughter and Learning». Peabody Journal of Education. 45 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1080/01619566709537484. JSTOR 1491447. - ^

«Obituary: Mr Walt Disney». The Times. December 16, 1966. p. 14. - ^

Cooke, Alistair (December 16, 1966). «Death of Walt Disney—folk-hero». The Manchester Guardian. p. 1. - ^ Gabler 2006, p. x.

- ^ «Centuries-old art behind Disney’s best animated films arrives at the Met». By Zachary Kussin. December 18, 2021. [1]

- ^

«Nominee Facts – Most Nominations and Awards» (PDF). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2013. - ^

«Winners & Nominees: Walt Disney». Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016. - ^

«Awards & Nominations: Walt Disney». Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016. - ^

«Complete National Film Registry Listing». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016. - ^

«AFI’s 100 Greatest American Movies of All Time». American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016. - ^

«Walt Disney». Hollywood Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2014. - ^

«Mickey Mouse». Hollywood Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016. - ^

«Hall of Fame Honorees: Complete List». Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2014. - ^

«John Muir Inducted in California Hall of Fame». The John Muir Exhibit. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2014. - ^

«Disney to be first honoree on O.C. Walk of Stars». Orange County Register. November 8, 2006. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2014. - ^

«Untitled». The Manchester Guardian. December 20, 1935. p. 10. - ^

«Walt Disney Honored». San Mateo Times. San Mateo, CA. February 5, 1952. p. 9. - ^ West Germans Against The West: Anti-Americanism in Media and Public Opinion in the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1968. Written by C. Müller

- ^ Unirio

- ^ a b

«Walt Disney». The California Museum. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016. - ^

Aarons, Lerby F. (September 15, 1964). «Arts, Science, Public Affairs Elite Honored With Freedom Medals». The Washington Post. p. 1. - ^

Marth, Mike (April 4, 1969). «Walt Disney Honored With Congressional Gold Medal». The Van Nuys News. p. 27. - ^

«Disney Receives Audubon Medal». The Blade. Toledo, OH. November 16, 1955. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016. - ^ Schmadel 2003, p. 342.

Sources

- Barrier, J. Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503759-3.

- Barrier, J. Michael (2007). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24117-6.

Buckaroo Bugs’.

- Beard, Richard R. (1982). Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center: Creating the New World of Tomorrow. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-0821-5.

- Broggie, Michael (2006). Walt Disney’s Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom. Marceline, MO: Carolwood Pacific. ISBN 978-0-9758584-2-4.

- Canemaker, John (2001). Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. Burbank, CA: Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0-7868-6496-6.

- Ceplair, Larry; Englund, Steven (1983). The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930–1960. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04886-7.

- Cohen, Karl F. (2004). Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0725-2.

- Dobson, Nichola (2009). Historical Dictionary of Animation and Cartoons. Plymouth, Devon: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6323-1.

- Eliot, Marc (1995). Walt Disney: Hollywood’s Dark Prince. London: André Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-98961-7.

- Finch, Christopher (1999). The Art of Walt Disney from Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0344-7.

- Gabler, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Biography. London: Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-277-4.

- Hollis, Tim; Ehrbar, Greg (2006). Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-61703-433-6.

- Korkis, Jim (2012). Who’s Afraid of the Song of the South?. Dallas, TX: Theme Park Press. ISBN 978-0-9843415-5-9.

- Krasniewicz, Louise (2010). Walt Disney: A Biography. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 978-0-313-35830-2.

- Langer, Mark (2000). «Disney, Walt». American National Biography. Retrieved April 11, 2016. (subscription required)

- Lee, Newton; Madej, Krystina (2012). Disney Stories: Getting to Digital. Tujunga, CA: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4614-2101-6.

- Mannheim, Steve (2016). Walt Disney and the Quest for Community. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-00058-7.

- Mosley, Leonard (1990). Disney’s World. Lanham, MD: Scarborough House. ISBN 978-1-58979-656-0.

- Nichols, Catherine (2014). Alice’s Wonderland: A Visual Journey Through Lewis Carroll’s Mad, Mad World. New York: Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1-937994-97-6.

- Norman, Floyd (2013). Animated Life: A Lifetime of Tips, Tricks, Techniques and Stories from a Disney Legend. Burlington, MA: Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-81805-4.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (February 2008). «Was Marie White? The Trajectory of a Question in the United States». The Journal of Southern History. 74 (1): 3–30.

- Pierce, John J. (1987). Foundations of Science Fiction: A Study in Imagination and Evolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25455-0.

- Schickel, Richard (1986). The Disney Version: The Life, Times, Art and Commerce of Walt Disney. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-85145-007-7.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- Telotte, Jay P. (June 2, 2008). The Mouse Machine: Disney and Technology. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09263-3.

- Thomas, Bob (1994) [1976]. Walt Disney: An American Original. New York: Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0-7868-6027-2.

- Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1995) [1981]. The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-6070-8.

- Tomlinson, John (2001). Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-5013-5.

- Watts, Steven (June 1995). «Walt Disney: Art and Politics in the American Century». The Journal of American History. 82 (1): 84–110. doi:10.2307/2081916. JSTOR 2081916.

- Watts, Steven (2013). The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-7300-0.

- Williams, Pat; Denney, James; Denney, Jim (2004). How to Be Like Walt: Capturing the Disney Magic Every Day of Your Life. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications. ISBN 978-0-7573-0231-2.

- Withrow, Steven (2009). Secrets of Digital Animation. Mies, Switzerland: RotoVision. ISBN 978-2-88893-014-3.

External links

- Walt Disney at IMDb

- Walt Disney at the TCM Movie Database

- Works by or about Walt Disney in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- The Walt Disney Family Museum

- The Walt Disney Birthplace

- Talking About Walt Disney at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- FBI Records: The Vault – Walter Elias Disney from the Federal Bureau of Investigation

|

Walt Disney |

|

|---|---|

Disney in 1946 |

|

| Born |

Walter Elias Disney December 5, 1901 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 15, 1966 (aged 65)

Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Occupations |

|

| Title | President of The Walt Disney Company[1] |

| Spouse |

Lillian Disney (m. 1925) |

| Children | 2, including Diane Disney Miller |

| Relatives | Disney family |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

|

Walter Elias Disney (;[2] December 5, 1901 – December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film producer, he holds the record for most Academy Awards earned and nominations by an individual, having won 22 Oscars from 59 nominations. He was presented with two Golden Globe Special Achievement Awards and an Emmy Award, among other honors. Several of his films are included in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress and have also been named as some of the greatest films ever by the American Film Institute. Disney was the first person to be nominated for Academy Awards in six different categories.

Born in Chicago in 1901, Disney developed an early interest in drawing. He took art classes as a boy and got a job as a commercial illustrator at the age of 18. He moved to California in the early 1920s and set up the Disney Brothers Studio with his brother Roy. With Ub Iwerks, he developed the character Mickey Mouse in 1928, his first highly popular success; he also provided the voice for his creation in the early years. As the studio grew, he became more adventurous, introducing synchronized sound, full-color three-strip Technicolor, feature-length cartoons and technical developments in cameras. The results, seen in features such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio, Fantasia (both 1940), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942), furthered the development of animated film. New animated and live-action films followed after World War II, including the critically successful Cinderella (1950), Sleeping Beauty (1959) and Mary Poppins (1964), the last of which received five Academy Awards.