Coordinates: 47°N 20°E / 47°N 20°E

|

Hungary Magyarország (Hungarian) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: «Himnusz» (Hungarian)[1] (English: «Hymn») |

|

![Location of Hungary (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/EU-Hungary.svg/250px-EU-Hungary.svg.png)

Location of Hungary (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Budapest 47°26′N 19°15′E / 47.433°N 19.250°E |

| Official languages | Hungarian[2] |

| Ethnic groups

(microcensus 2016) |

|

| Religion

(census 2011)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Hungarian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

|

• President |

Katalin Novák |

|

• Prime Minister |

Viktor Orbán |

|

• Speaker of the National Assembly |

László Kövér |

| Legislature | Országgyűlés |

| Foundation | |

|

• Principality of Hungary |

895[5] |

|

• Christian Kingdom |

25 December 1000[6] |

|

• Golden Bull of 1222 |

24 April 1222 |

|

• Battle of Mohács |

29 August 1526 |

|

• Liberation of Buda |

2 September 1686 |

|

• Revolution of 1848 |

15 March 1848 |

|

• Austro-Hungarian Empire |

30 March 1867 |

|

• Treaty of Trianon |

4 June 1920 |

|

• Third Republic |

23 October 1989 |

|

• Joined NATO |

12 March 1999 |

|

• Joined the European Union |

1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

93,030[7] km2 (35,920 sq mi) (108th) |

|

• Water (%) |

3.7[8] |

| Population | |

|

• 2021 estimate |

9,689,000 [9] (91st) |

|

• Density |

105/km2 (271.9/sq mi) (78th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 46th |

| Currency | Forint (HUF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | yyyy.mm.dd. |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +36 |

| ISO 3166 code | HU |

| Internet TLD | .hu[a] |

|

Hungary (Hungarian: Magyarország [ˈmɒɟɒrorsaːɡ] (listen)) is a landlocked country in Central Europe.[2] Spanning 93,030 square kilometres (35,920 sq mi) of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and Slovenia to the southwest, and Austria to the west. Hungary has a population of 9.7 million, mostly ethnic Hungarians and a significant Romani minority. Hungarian, the official language, is the world’s most widely spoken Uralic language and among the few non-Indo-European languages widely spoken in Europe.[13] Budapest is the country’s capital and largest city; other major urban areas include Debrecen, Szeged, Miskolc, Pécs, and Győr.

The territory of present-day Hungary has for centuries been a crossroads for various peoples, including Celts, Romans, Germanic tribes, Huns, West Slavs and the Avars. The foundation of the Hungarian state was established in the late 9th century AD with the conquest of the Carpathian Basin by Hungarian grand prince Árpád.[14][15] His great-grandson Stephen I ascended the throne in 1000, converting his realm to a Christian kingdom. By the 12th century, Hungary became a regional power, reaching its cultural and political height in the 15th century.[16] Following the Battle of Mohács in 1526, it was partially occupied by the Ottoman Empire (1541–1699). Hungary came under Habsburg rule at the turn of the 18th century, later joining with the Austrian Empire to form Austria-Hungary, a major power into the early 20th century.[17]

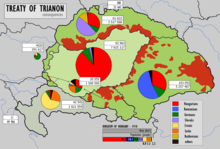

Austria-Hungary collapsed after World War I, and the subsequent Treaty of Trianon established Hungary’s current borders, resulting in the loss of 71% of its territory, 58% of its population, and 32% of ethnic Hungarians.[18][19][20] Following the tumultuous interwar period, Hungary joined the Axis powers in World War II, suffering significant damage and casualties.[21][22] Postwar Hungary became a satellite state of the Soviet Union, leading to the establishment of the Hungarian People’s Republic. Following the failed 1956 revolution, Hungary became a comparatively freer, though still repressive, member of the Eastern Bloc. The removal of Hungary’s border fence with Austria accelerated the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and subsequently the Soviet Union.[23] On 23 October 1989, Hungary again became a democratic parliamentary republic.[24] Hungary joined the European Union in 2004 and has been part of the Schengen Area since 2007.[25]

Hungary is a middle power in international affairs, owing mostly to its cultural and economic influence.[26] It is a high-income economy with a very high human development index, where citizens enjoy universal health care and tuition-free secondary education.[27][28] Hungary has a long history of significant contributions to arts, music, literature, sports, science and technology.[29][30][31][32] It is a popular tourist destination in Europe, drawing 24.5 million international tourists in 2019.[33] It is a member of numerous international organisations, including the Council of Europe, NATO, United Nations, World Health Organization, World Trade Organization, World Bank, International Investment Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the Visegrád Group.[34]

Etymology

The «H» in the name of Hungary (and Latin Hungaria) is most likely derived from historical associations with the Huns, who had settled Hungary prior to the Avars. The rest of the word comes from the Latinised form of Byzantine Greek Oungroi (Οὔγγροι). The Greek name might be borrowed from Old Bulgarian ągrinŭ, in turn borrowed from Oghur-Turkic Onogur (‘ten [tribes of the] Ogurs’), perhaps entering Slavic through a dialectal *Ongur.[35] Onogur was the collective name for the tribes who later joined the Bulgar tribal confederacy that ruled the eastern parts of Hungary after the Avars.[36][37] Peter B. Golden also considers Árpád Berta’s theory, who has suggested that the name derives from Khazar Turkic ongar (oŋ «right,» oŋar- «to make something better, to put (it) right,» oŋgar- “to make something better, to put (it) right,” oŋaru “towards the right») “rightwing”. This points to the idea that the pre-Conquest Magyar Union formed the «right wing» (= western wing) of the Khazar military forces.[38]

The Hungarian endonym is Magyarország, composed of magyar (‘Hungarian’) and ország (‘country’). The name «Magyar», which refers to the people of the country, more accurately reflects the name of the country in some other languages such as Turkish, Persian and other languages as Magyaristan or Land of Magyars or similar. The word magyar is taken from the name of one of the seven major semi-nomadic Hungarian tribes, magyeri.[39][40][41] The first element magy is likely from proto-Ugric *mäńć- ‘man, person’, also found in the name of the Mansi people (mäńćī, mańśi, måńś). The second element eri, ‘man, men, lineage’, survives in Hungarian férj ‘husband’, and is cognate with Mari erge ‘son’, Finnish archaic yrkä ‘young man’.[42]

History

Before 895

Roman provinces: Illyricum, Macedonia, Dacia, Moesia, Pannonia, Thracia

The Roman Empire conquered the territory between the Alps and the area west of the Danube River from 16 to 15 BC, the Danube being the frontier of the empire.[43] In 14 BC, Pannonia, the western part of the Carpathian Basin, which includes today’s west of Hungary, was recognised by emperor Augustus in the Res Gestae Divi Augusti as part of the Roman Empire.[43] The area south-east of Pannonia was organised as the Roman province Moesia in 6 BC.[43] An area east of the river Tisza became the Roman province of Dacia in 106 AD, which included today’s east Hungary. It remained under Roman rule until 271.[44] From 235, the Roman Empire went through troubled times, caused by revolts, rivalry and rapid succession of emperors. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century under the stress of the migration of Germanic tribes and Carpian pressure.[44]

This period brought many invaders into Central Europe, beginning with the Hunnic Empire (c. 370–469). The most powerful ruler of the Hunnic Empire was Attila the Hun (434–453), who later became a central figure in Hungarian mythology.[45] After the disintegration of the Hunnic Empire, the Gepids, an Eastern Germanic tribe, who had been vassalised by the Huns, established their own kingdom in the Carpathian Basin.[46] Other groups which reached the Carpathian Basin during the Migration Period were the Goths, Vandals, Lombards, and Slavs.[44]

In the 560s, the Avars founded the Avar Khaganate, a state that maintained supremacy in the region for more than two centuries. The Franks under Charlemagne defeated the Avars in a series of campaigns during the 790s.[47] Between 804 and 829, the First Bulgarian Empire conquered the lands east of the Danube and took over the rule of the local Slavic tribes and remnants of the Avars.[48] By the mid-9th century, the Balaton Principality, also known as Lower Pannonia, was established west of the Danube as part of the Frankish March of Pannonia.[49]

Middle Ages (895–1526)

The freshly unified Hungarians[50] led by Árpád (by tradition a descendant of Attila), settled in the Carpathian Basin starting in 895.[51][52] According to the Finno-Ugrian theory, they originated from an ancient Uralic-speaking population that formerly inhabited the forested area between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains.[53] As a federation of united tribes, Hungary was established in 895, some 50 years after the division of the Carolingian Empire at the Treaty of Verdun in 843, before the unification of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Initially, the rising Principality of Hungary («Western Tourkia» in medieval Greek sources)[54] was a state created by a semi-nomadic people. It accomplished an enormous transformation into a Christian realm during the 10th century.[55] This state was well-functioning, and the nation’s military power allowed the Hungarians to conduct successful fierce campaigns and raids, from Constantinople to as far as today’s Spain.[55] The Hungarians defeated no fewer than three major East Frankish imperial armies between 907 and 910.[56] A defeat at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 signaled a provisory end to most campaigns on foreign territories, at least towards the west.

Age of Árpádian kings

In 972 the ruling prince (Hungarian: fejedelem) Géza of the Árpád dynasty officially started to integrate Hungary into Christian Western Europe.[57] His first-born son, Saint Stephen I, became the first King of Hungary after defeating his pagan uncle Koppány, who also claimed the throne. Under Stephen, Hungary was recognised as a Catholic Apostolic Kingdom.[58] Applying to Pope Sylvester II, Stephen received the insignia of royalty (including probably a part of the Holy Crown of Hungary, currently kept in the Hungarian Parliament) from the papacy.

By 1006, Stephen consolidated his power and started sweeping reforms to convert Hungary into a Western feudal state. The country switched to using Latin for administration purposes, and until as late as 1844, Latin remained the official language of administration. Around this time, Hungary began to become a powerful kingdom.[citation needed] Ladislaus I extended Hungary’s frontier in Transylvania and invaded Croatia in 1091.[59][60][61][62] The Croatian campaign culminated in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain in 1097 and a personal union of Croatia and Hungary in 1102, ruled by Coloman.[63]

The Holy Crown (Szent Korona), one of the key symbols of Hungary

The most powerful and wealthiest king of the Árpád dynasty was Béla III, who disposed of the equivalent of 23 tonnes of silver per year. This exceeded the income of the French king (estimated at 17 tonnes) and was double the receipts of the English Crown.[64] Andrew II issued the Diploma Andreanum which secured the special privileges of the Transylvanian Saxons and is considered the first autonomy law in the world.[65] He led the Fifth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1217, setting up the largest royal army in the history of Crusades. His Golden Bull of 1222 was the first constitution in Continental Europe. The lesser nobles also began to present Andrew with grievances, a practice that evolved into the institution of the parliament (parlamentum publicum).

In 1241–1242, the kingdom received a major blow with the Mongol (Tatar) invasion. Up to half of Hungary’s population of 2 million were victims of the invasion.[66] King Béla IV let Cumans and Jassic people into the country, who were fleeing the Mongols.[67] Over the centuries, they were fully assimilated into the Hungarian population.[68] After the Mongols retreated, King Béla ordered the construction of hundreds of stone castles and fortifications, to defend against a possible second Mongol invasion. The Mongols returned to Hungary in 1285, but the newly built stone-castle systems and new tactics (using a higher proportion of heavily armed knights) stopped them. The invading Mongol force was defeated[69] near Pest by the royal army of King Ladislaus IV. As with later invasions, it was repelled handily, the Mongols losing much of their invading force.

Age of elected kings

The Kingdom of Hungary reached one of its greatest extents during the Árpádian kings, yet royal power was weakened at the end of their rule in 1301. After a destructive period of interregnum (1301–1308), the first Angevin king, Charles I of Hungary – a bilineal descendant of the Árpád dynasty – successfully restored royal power and defeated oligarch rivals, the so-called «little kings». The second Angevin Hungarian king, Louis the Great (1342–1382), led many successful military campaigns from Lithuania to southern Italy (Kingdom of Naples) and was also King of Poland from 1370. After King Louis died without a male heir, the country was stabilised only when Sigismund of Luxembourg (1387–1437) succeeded to the throne, who in 1433 also became Holy Roman Emperor. Sigismund was also (in several ways) a bilineal descendant of the Árpád dynasty.

The first Hungarian Bible translation was completed in 1439. For half a year in 1437, there was an antifeudal and anticlerical peasant revolt in Transylvania which was strongly influenced by Hussite ideas.

From a small noble family in Transylvania, John Hunyadi grew to become one of the country’s most powerful lords, thanks to his outstanding capabilities as a mercenary commander. He was elected governor, then regent. He was a successful crusader against the Ottoman Turks, one of his greatest victories being the siege of Belgrade in 1456.

The last strong king of medieval Hungary was the Renaissance king Matthias Corvinus (1458–1490), son of John Hunyadi. His election was the first time that a member of the nobility mounted to the Hungarian royal throne without dynastic background. He was a successful military leader and an enlightened patron of the arts and learning.[70] His library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe’s greatest collection of historical chronicles, philosophic and scientific works in the 15th century, and second only in size to the Vatican Library. Items from the Bibliotheca Corviniana were inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2005.[71] The serfs and common people considered him a just ruler because he protected them from excessive demands and other abuses by the magnates.[72] Under his rule, in 1479, the Hungarian army destroyed the Ottoman and Wallachian troops at the Battle of Breadfield. Abroad he defeated the Polish and German imperial armies of Frederick at Breslau (Wrocław). Matthias’ mercenary standing army, the Black Army of Hungary, was an unusually large army for its time, and it conquered Vienna as well as parts of Austria and Bohemia.

Decline (1490–1526)

King Matthias died without lawful sons, and the Hungarian magnates procured the accession of the Pole Vladislaus II (1490–1516), supposedly because of his weak influence on Hungarian aristocracy.[70] Hungary’s international role declined, its political stability was shaken, and social progress was deadlocked.[73] In 1514, the weakened old King Vladislaus II faced a major peasant rebellion led by György Dózsa, which was ruthlessly crushed by the nobles, led by John Zápolya. The resulting degradation of order paved the way for Ottoman pre-eminence. In 1521, the strongest Hungarian fortress in the South, Nándorfehérvár (today’s Belgrade, Serbia), fell to the Turks. The early appearance of Protestantism further worsened internal relations in the country.

Ottoman wars (1526–1699)

Painting commemorating the Siege of Eger, a major victory against the Ottomans

After some 150 years of wars with the Hungarians and other states, the Ottomans gained a decisive victory over the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, where King Louis II died while fleeing. Amid political chaos, the divided Hungarian nobility elected two kings simultaneously, John Zápolya and Ferdinand I of the Habsburg dynasty. With the conquest of Buda by the Turks in 1541, Hungary was divided into three parts and remained so until the end of the 17th century. The north-western part, termed as Royal Hungary, was annexed by the Habsburgs who ruled as kings of Hungary. The eastern part of the kingdom became independent as the Principality of Transylvania, under Ottoman (and later Habsburg) suzerainty. The remaining central area, including the capital Buda, was known as the Pashalik of Buda.

The vast majority of the seventeen and nineteen thousand Ottoman soldiers in service in the Ottoman fortresses in the territory of Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs rather than ethnic Turkish people.[74] Orthodox Southern Slavs were also acting as akinjis and other light troops intended for pillaging in the territory of present-day Hungary.[75] In 1686, the Holy League’s army, containing over 74,000 men from various nations, reconquered Buda from the Turks. After some more crushing defeats of the Ottomans in the next few years, the entire Kingdom of Hungary was removed from Ottoman rule by 1718. The last raid into Hungary by the Ottoman vassals Tatars from Crimea took place in 1717.[76] The constrained Habsburg Counter-Reformation efforts in the 17th century reconverted the majority of the kingdom to Catholicism. The ethnic composition of Hungary was fundamentally changed as a consequence of the prolonged warfare with the Turks. A large part of the country became devastated, population growth was stunted, and many smaller settlements perished.[77] The Austrian-Habsburg government settled large groups of Serbs and other Slavs in the depopulated south, and settled Germans (called Danube Swabians) in various areas, but Hungarians were not allowed to settle or re-settle in the south of the Carpathian Basin.[78]

From the 18th century to World War I (1699–1918)

Between 1703 and 1711, there was a large-scale war of independence led by Francis II Rákóczi, who after the dethronement of the Habsburgs in 1707 at the Diet of Ónod, took power provisionally as the ruling prince for the wartime period, but refused the Hungarian crown and the title «king». The uprisings lasted for years. The Hungarian Kuruc army, although taking over most of the country, lost the main battle at Trencsén (1708). Three years later, because of the growing desertion, defeatism, and low morale, the Kuruc forces finally surrendered.[79]

During the Napoleonic Wars and afterward, the Hungarian Diet had not convened for decades.[80] In the 1820s, the emperor was forced to convene the Diet, which marked the beginning of a Reform Period (1825–1848, Hungarian: reformkor). Count István Széchenyi, one of the most prominent statesmen of the country, recognised the urgent need for modernisation and his message got through. The Hungarian Parliament was reconvened in 1825 to handle financial needs. A liberal party emerged and focused on providing for the peasantry. Lajos Kossuth—a famous journalist at that time—emerged as a leader of the lower gentry in the Parliament. A remarkable upswing started as the nation concentrated its forces on modernisation even though the Habsburg monarchs obstructed all important liberal laws relating to civil and political rights and economic reforms. Many reformers (Lajos Kossuth, Mihály Táncsics) were imprisoned by the authorities.

On 15 March 1848, mass demonstrations in Pest and Buda enabled Hungarian reformists to push through a list of 12 demands. Under Governor and President Lajos Kossuth and Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány, the House of Habsburg was dethroned. The Habsburg ruler and his advisors skillfully manipulated the Croatian, Serbian and Romanian peasantry, led by priests and officers firmly loyal to the Habsburgs, and induced them to rebel against the Hungarian government, though the Hungarians were supported by the vast majority of the Slovak, German and Rusyn nationalities and by all the Jews of the kingdom, as well as by a large number of Polish, Austrian and Italian volunteers.[81] In July 1849 the Hungarian Parliament proclaimed and enacted the first laws of ethnic and minority rights in the world.[82] Many members of the nationalities gained the coveted highest positions within the Hungarian Army, like General János Damjanich, an ethnic Serb who became a Hungarian national hero through his command of the 3rd Hungarian Army Corps or Józef Bem, who was Polish and also became a national hero in Hungary. The Hungarian forces (Honvédség) defeated Austrian armies. To counter the successes of the Hungarian revolutionary army, Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph I asked for help from the «Gendarme of Europe», Tsar Nicholas I, whose Russian armies invaded Hungary. This made Artúr Görgey surrender in August 1849. The leader of the Austrian army, Julius Jacob von Haynau, became governor of Hungary for a few months and ordered the execution of the 13 Martyrs of Arad, leaders of the Hungarian army, and Prime Minister Batthyány in October 1849. Kossuth escaped into exile. Following the war of 1848–1849, the whole country was in «passive resistance».

Because of external and internal problems, reforms seemed inevitable, and major military defeats of Austria forced the Habsburgs to negotiate the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, by which the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was formed. This empire had the second largest area in Europe (after the Russian Empire), and it was the third most populous (after Russia and the German Empire). The two realms were governed separately by two parliaments from two capital cities, with a common monarch and common external and military policies. Economically, the empire was a customs union. The old Hungarian Constitution was restored, and Franz Joseph I was crowned as King of Hungary. The era witnessed impressive economic development. The formerly backward Hungarian economy became relatively modern and industrialised by the turn of the 20th century, although agriculture remained dominant until 1890. In 1873, the old capital Buda and Óbuda were officially united with Pest,[83] thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. Many of the state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period.

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Prime Minister István Tisza and his cabinet tried to avoid the outbreak and escalating of a war in Europe, but their diplomatic efforts were unsuccessful. Austria-Hungary drafted 9 million (fighting forces: 7.8 million) soldiers in World War I (over 4 million from the Kingdom of Hungary) on the side of Germany, Bulgaria, and Turkey. The troops raised in the Kingdom of Hungary spent little time defending the actual territory of Hungary, with the exceptions of the Brusilov offensive in June 1916 and a few months later when the Romanian army made an attack into Transylvania,[84][self-published source?] both of which were repelled. The Central Powers conquered Serbia. Romania declared war. The Central Powers conquered southern Romania and the Romanian capital Bucharest. In 1916 Emperor Joseph died, and the new monarch Charles IV sympathised with the pacifists. With great difficulty, the Central Powers stopped and repelled the attacks of the Russian Empire.

The Eastern Front of the Allied (Entente) Powers completely collapsed. The Austro-Hungarian Empire then withdrew from all defeated countries. On the Italian front, the Austro-Hungarian army made no progress against Italy after January 1918. Despite great success on the Eastern Front, Germany suffered complete defeat on the Western Front. By 1918, the economic situation had deteriorated (strikes in factories were organised by leftist and pacifist movements) and uprisings in the army had become commonplace. In the capital cities, the Austrian and Hungarian leftist liberal movements (the maverick parties) and their leaders supported the separatism of ethnic minorities. Austria-Hungary signed a general armistice in Padua on 3 November 1918.[85] In October 1918, Hungary’s union with Austria was dissolved.

Between the World Wars (1918–1941)

With the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost 72% of its territory, its sea ports, and 3,425,000 ethnic Hungarians[86][87]

Majority Hungarian areas (according to the 1910 census) detached from Hungary

Following the First World War, Hungary underwent a period of profound political upheaval, beginning with the Aster Revolution in 1918, which brought the social-democratic Mihály Károlyi to power as prime minister. The Hungarian Royal Honvéd army still had more than 1,400,000 soldiers[88][89] when Károlyi was installed. Károlyi yielded to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s demand for pacifism by ordering the disarmament of the Hungarian army. This happened under the direction of Béla Linder, minister of war in the Károlyi government.[90][91] Disarmament of its army meant that Hungary was to remain without a national defence at a time of particular vulnerability. During the rule of Károlyi’s pacifist cabinet, Hungary lost control over approximately 75% of its former pre-WW1 territories (325,411 square kilometres (125,642 sq mi)) without a fight and was subject to foreign occupation. The Little Entente, sensing an opportunity, invaded the country from three sides—Romania invaded Transylvania, Czechoslovakia annexed Upper Hungary (today’s Slovakia), and a joint Serb-French coalition annexed Vojvodina and other southern regions. In March 1919, communists led by Béla Kun ousted the Károlyi government and proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic (Tanácsköztársaság), followed by a thorough Red Terror campaign. Despite some successes on the Czechoslovak front, Kun’s forces were ultimately unable to resist the Romanian invasion; by August 1919, Romanian troops occupied Budapest and ousted Kun.

In November 1919, rightist forces led by former Austro-Hungarian admiral Miklós Horthy entered Budapest; exhausted by the war and its aftermath, the populace accepted Horthy’s leadership. In January 1920, parliamentary elections were held, and Horthy was proclaimed regent of the reestablished Kingdom of Hungary, inaugurating the so-called «Horthy era» (Horthy-kor). The new government worked quickly to normalise foreign relations while turning a blind eye to a White Terror that swept through the countryside; extrajudicial killings of suspected communists and Jews lasted well into 1920. On 4 June 1920, the Treaty of Trianon established new borders for Hungary. The country lost 71% of its territory and 66% of its pre-war population, as well as many sources of raw materials and its sole port at Fiume.[92][93] Though the revision of the treaty quickly rose to the top of the national political agenda, the Horthy government was not willing to resort to military intervention to do so.

The initial years of the Horthy regime were preoccupied with putsch attempts by Charles IV, the Austro-Hungarian pretender; continued suppression of communists; and a migration crisis triggered by the Trianon territorial changes. Though free elections continued, Horthy’s personality and those of his personally selected prime ministers dominated the political scene. The government’s actions continued to drift right with the passage of antisemitic laws and, because of the continued isolation of the Little Entente, economic and then political gravitation towards Italy and Germany. The Great Depression further exacerbated the situation, and the popularity of fascist politicians increased, such as Gyula Gömbös and Ferenc Szálasi, promising economic and social recovery.

Horthy’s nationalist agenda reached its apogee in 1938 and 1940, when the Nazis rewarded Hungary’s staunchly pro-Germany foreign policy in the First and Second Vienna Awards, peacefully restoring ethnic-Hungarian-majority areas lost after Trianon. In 1939, Hungary regained further territory from Czechoslovakia through force. Hungary formally joined the Axis powers on 20 November 1940 and in 1941 participated in the invasion of Yugoslavia, gaining some of its former territories in the south.

World War II (1941–1945)

Kingdom of Hungary, 1941–44

Hungary formally entered World War II as an Axis power on 26 June 1941, declaring war on the Soviet Union after unidentified planes bombed Kassa, Munkács, and Rahó. Hungarian troops fought on the Eastern Front for two years. Despite early success at the Battle of Uman,[94] the government began seeking a secret peace pact with the Allies after the Second Army suffered catastrophic losses at the River Don in January 1943. Learning of the planned defection, German troops occupied Hungary on 19 March 1944 to guarantee Horthy’s compliance. In October, as the Soviet front approached, and the government made further efforts to disengage from the war, German troops ousted Horthy and installed a puppet government under Szálasi’s fascist Arrow Cross Party.[94] Szálasi pledged all the country’s capabilities in service of the German war machine. By October 1944, the Soviets had reached the river Tisza, and despite some losses, succeeded in encircling and besieging Budapest in December.

After German occupation, Hungary participated in the Holocaust.[95][96] During the German occupation in May–June 1944, the Arrow Cross and Hungarian police deported nearly 440,000 Jews, mainly to Auschwitz. Nearly all of them were murdered.[97][98] The Swedish Diplomat Raoul Wallenberg managed to save a considerable number of Hungarian Jews by giving them Swedish passports.[99] Rezső Kasztner, one of the leaders of the Hungarian Aid and Rescue Committee, bribed senior SS officers such as Adolf Eichmann to allow some Jews to escape.[100][101][102] The Horthy government’s complicity in the Holocaust remains a point of controversy and contention.

The war left Hungary devastated, destroying over 60% of the economy and causing significant loss of life. In addition to the over 600,000 Hungarian Jews killed,[103] as many as 280,000[104][105] other Hungarians were raped, murdered and executed or deported for slave labour by Czechoslovaks,[106][107][108][109][110][111] Soviet Red Army troops,[112][113][114] and Yugoslavs.[115]

On 13 February 1945, Budapest surrendered; by April, German troops left the country under Soviet military occupation. 200,000 Hungarians were expelled from Czechoslovakia in exchange for 70,000 Slovaks living in Hungary. 202,000 ethnic Germans were expelled to Germany,[116] and through the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties, Hungary was again reduced to its immediate post-Trianon borders.

Communism (1945–1989)

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany, Hungary became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. The Soviet leadership selected Mátyás Rákosi to front the Stalinisation of the country, and Rákosi de facto ruled Hungary from 1949 to 1956. His government’s policies of militarisation, industrialisation, collectivisation, and war compensation led to a severe decline in living standards. In imitation of Stalin’s KGB, the Rákosi government established a secret political police, the ÁVH, to enforce the regime. In the ensuing purges, approximately 350,000 officials and intellectuals were imprisoned or executed from 1948 to 1956.[117] Many freethinkers, democrats, and Horthy-era dignitaries were secretly arrested and extrajudicially interned in domestic and foreign gulags. Some 600,000 Hungarians were deported to Soviet labour camps, where at least 200,000 died.[118]

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet Union pursued a programme of de-Stalinisation that was inimical to Rákosi, leading to his deposition. The following political cooling saw the ascent of Imre Nagy to the premiership and the growing interest of students and intellectuals in political life. Nagy promised market liberalisation and political openness, while Rákosi opposed both vigorously. Rákosi eventually managed to discredit Nagy and replace him with the more hard-line Ernő Gerő. Hungary joined the Warsaw Pact in May 1955, as societal dissatisfaction with the regime swelled. Following the firing on peaceful demonstrations by Soviet soldiers and secret police, and rallies throughout the country on 23 October 1956, protesters took to the streets in Budapest, initiating the 1956 Revolution. In an effort to quell the chaos, Nagy returned as premier, promised free elections, and took Hungary out of the Warsaw Pact.

The violence nonetheless continued as revolutionary militias sprung up against the Soviet Army and the ÁVH; the roughly 3,000-strong resistance fought Soviet tanks using Molotov cocktails and machine-pistols. Though the preponderance of the Soviets was immense, they suffered heavy losses, and by 30 October 1956, most Soviet troops had withdrawn from Budapest to garrison the countryside. For a time, the Soviet leadership was unsure how to respond but eventually decided to intervene to prevent a destabilisation of the Soviet bloc. On 4 November, reinforcements of more than 150,000 troops and 2,500 tanks entered the country from the Soviet Union.[120] Nearly 20,000 Hungarians were killed resisting the intervention, while an additional 21,600 were imprisoned afterward for political reasons. Some 13,000 were interned and 230 brought to trial and executed. Nagy was secretly tried, found guilty, sentenced to death, and executed by hanging in June 1958. Because borders were briefly opened, nearly a quarter of a million people fled the country by the time the revolution was suppressed.[121]

Kádár era (1956–1988)

After a second, briefer period of Soviet military occupation, János Kádár, Nagy’s former minister of state, was chosen by the Soviet leadership to head the new government and chair the new ruling Socialist Workers’ Party. Kádár quickly normalised the situation. In 1963, the government granted a general amnesty and released the majority of those imprisoned for their active participation in the uprising. Kádár proclaimed a new policy line, according to which the people were no longer compelled to profess loyalty to the party if they tacitly accepted the socialist regime as a fact of life. In many speeches, he described this as, «Those who are not against us are with us.» Kádár introduced new planning priorities in the economy, such as allowing farmers significant plots of private land within the collective farm system (háztáji gazdálkodás). The living standard rose as consumer goods and food production took precedence over military production, which was reduced to one-tenth of pre-revolutionary levels.

In 1968, the New Economic Mechanism introduced free-market elements into the socialist command economy. From the 1960s through the late 1980s, Hungary was often referred to as «the happiest barrack» within the Eastern bloc. During the latter part of the Cold War Hungary’s GDP per capita was fourth only to East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union.[122] As a result of this relatively high standard of living, a more liberalised economy, a less censored press, and less restricted travel rights, Hungary was generally considered one of the more liberal countries in which to live in Central Europe during communism. In 1980, Hungary sent a Cosmonaut into space as part of the Interkosmos. The first Hungarian astronaut was Bertalan Farkas. Hungary became the seventh nation to be represented in space by him.[123] In the 1980s, however, living standards steeply declined again because of a worldwide recession to which communism was unable to respond.[124] By the time Kádár died in 1989, the Soviet Union was in steep decline and a younger generation of reformists saw liberalisation as the solution to economic and social issues.

Third Republic (1989–present)

Hungary’s transition from communism to democracy and capitalism (rendszerváltás, «regime change») was peaceful and prompted by economic stagnation, domestic political pressure, and changing relations with other Warsaw Pact countries. Although the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party began Round Table Talks with various opposition groups in March 1989, the reburial of Imre Nagy as a revolutionary martyr that June is widely considered the symbolic end of communism in Hungary. Over 100,000 people attended the Budapest ceremony without any significant government interference, and many speakers openly called for Soviet troops to leave the country. Free elections were held in May 1990, and the Hungarian Democratic Forum, a major conservative opposition group, was elected to the head of a coalition government. József Antall became the first democratically elected prime minister since World War II.

With the removal of state subsidies and rapid privatisation in 1991, Hungary was affected by a severe economic recession. The Antall government’s austerity measures proved unpopular, and the Communist Party’s legal and political heir, the Socialist Party, won the subsequent 1994 elections. This abrupt shift in the political landscape was repeated in 1998 and 2002; in each electoral cycle, the governing party was ousted and the erstwhile opposition elected. Like most other post-communist European states, however, Hungary broadly pursued an integrationist agenda, joining NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004. As a NATO member, Hungary was involved in the Yugoslav Wars.

In 2006, major nationwide protests erupted after it was revealed that Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány had claimed in a closed-door speech that his party «lied» to win the recent elections. The popularity of left-wing parties plummeted in the ensuing political upheaval, and in 2010, Viktor Orbán’s national-conservative Fidesz party was elected to a parliamentary supermajority. The legislature consequently approved a new constitution, among other sweeping governmental and legal changes. One of these was the change of constituencies, and making elections single-round elections.

Police car at Hungary-Serbia border barrier

During the 2015 migrant crisis, the government built a border barrier on the Hungarian-Croatian and Hungarian-Serbian borders to prevent illegal migration.[125] The Hungarian government also criticised the official European Union policy for not dissuading migrants from entering Europe.[126] The barrier became successful, as from 17 October 2015 onward, thousands of migrants were diverted daily to Slovenia instead.[127] Migration has become a key issue in the 2018 parliamentary elections. Fidesz wins the election again supermajority.[128]

In the late 2010s, Orbán’s government came under increased international scrutiny over alleged rule-of-law violations. In 2018, the European Parliament voted to act against Hungary under the terms of Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union. Hungary has and continues to dispute these allegations.[129]

The coronavirus pandemic has also hit Hungary hard. On 4 March 2020, the first cases in Hungary were announced.[130] The first coronavirus-related death was announced on 15 March on the government’s official website.[131] On March 18, 2020, Surgeon general Cecília Müller announced that the virus had spread to every part of the country.[132] As of June 2021, Hungary had the second-highest COVID-19 death rate in the world.[133] The first vaccine against Covid19 became available in the European Union at the end of December, so on 26 December, the vaccines were also available in Hungary, in line with the other EU member states. The vaccination was free and voluntary. In February 2021, Hungary became the first country in the EU to use Russian and Chinese vaccines, making it one of the highest vaccination coverage countries in Europe for a short period of time.

Geography

Geographic map of Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country. Its geography has traditionally been defined by its two main waterways, the Danube and Tisza rivers. The common tripartite division—Dunántúl («beyond the Danube», Transdanubia), Tiszántúl («beyond the Tisza»), and Duna-Tisza kőze («between the Danube and Tisza»)—is a reflection of this. The Danube flows north–south through the centre of contemporary Hungary, and the entire country lies within its drainage basin.

Transdanubia, which stretches westward from the centre of the country towards Austria, is a primarily hilly region with a terrain varied by low mountains. These include the very eastern stretch of the Alps, Alpokalja, in the west of the country, the Transdanubian Mountains in the central region of Transdanubia, and the Mecsek Mountains and Villány Mountains in the south. The highest point of the area is the Írott-kő in the Alps, at 882 metres (2,894 ft). The Little Hungarian Plain (Kisalfőld) is found in northern Transdanubia. Lake Balaton and Lake Hévíz, the largest lake in Central Europe and the largest thermal lake in the world, respectively, are in Transdanubia as well.

The Duna-Tisza kőze and Tiszántúl are characterised mainly by the Great Hungarian Plain (Alfőld), which stretches across most of the eastern and southeastern areas of the country. To the north of the plain are the foothills of the Carpathians in a wide band near the Slovakian border. The Kékes at 1,014 m (3,327 ft) is the tallest mountain in Hungary and is found there.

Phytogeographically, Hungary belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Hungary belongs to the terrestrial ecoregion of Pannonian mixed forests.[134] It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.25/10, ranking it 156th globally out of 172 countries.[135]

Hungary has 10 national parks, 145 minor nature reserves, and 35 landscape protection areas.

Climate

Hungary has a temperate seasonal climate,[136][137] with generally warm summers with low overall humidity levels but frequent rain showers and cold snowy winters. Average annual temperature is 9.7 °C (49.5 °F). Temperature extremes are 41.9 °C (107.4 °F) on 20 July 2007 at Kiskunhalas in the summer and −35 °C (−31.0 °F) on 16 February 1940 at Miskolc in the winter. Average high temperature in the summer is 23 to 28 °C (73 to 82 °F) and average low temperature in the winter is −3 to −7 °C (27 to 19 °F). The average yearly rainfall is approximately 600 mm (23.6 in).

Hungary is ranked sixth in an environmental protection index by GW/CAN.[138]

Government and politics

Hungary is a unitary, parliamentary republic. The Hungarian political system operates under a framework reformed in 2012; this constitutional document is the Fundamental Law of Hungary. Amendments generally require a two-thirds majority of parliament; the fundamental principles of the constitution (as expressed in the articles guaranteeing human dignity, the separation of powers, the state structure, and the rule of law) are valid in perpetuity. 199 Members of Parliament (országgyűlési képviselő) are elected to the highest organ of state authority, the unicameral Országgyűlés (National Assembly), every four years in a single-round first-past-the-post election with an election threshold of 5%.[citation needed]

The President of the Republic (köztársasági elnök) serves as the head of state and is elected by the National Assembly every five years. The president is invested primarily with representative responsibilities and powers: receiving foreign heads of state, formally nominating the prime minister at the recommendation of the National Assembly, and serving as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Importantly, the president is also invested with veto power and may send legislation to the 15-member Constitutional Court for review. The third most significant governmental position in Hungary is the Speaker of the National Assembly, who is elected by the National Assembly and responsible for overseeing the daily sessions of the body.[citation needed]

The prime minister (miniszterelnök) is elected by the National Assembly, serving as the head of government and exercising executive power. Traditionally, the prime minister is the leader of the largest party in parliament. The prime minister selects Cabinet ministers and has the exclusive right to dismiss them, although cabinet nominees must appear before consultative open hearings before one or more parliamentary committees, survive a vote in the National Assembly, and be formally approved by the president. The Cabinet reports to Parliament.[citation needed]

Political parties

|

Current Structure of the National Assembly of Hungary |

|

|---|---|

| Structure | |

| Seats | 199 |

|

|

|

Political groups |

Government (135)

Supported by (1)

Opposition (65)

|

Since the fall of communism, Hungary has a multi-party system. The last Hungarian parliamentary election took place on 3 April 2022.[139] This parliamentary election was the 8th since the 1990 first multi-party election. The result was a victory for Fidesz–KDNP alliance, preserving its two-thirds majority with Orbán remaining prime minister.[140] It was the third election according to the new Constitution of Hungary which went into force on 1 January 2012. The new electoral law also entered into force that day. The voters elected 199 MPs instead of previous 386 lawmakers.[141][142] Since 2014, voters of ethnic minorities in Hungary are able to vote on nationality lists. The minorities can obtain a preferential mandate if they reach the quarter of the ninety-third part of the list votes.[143] Nationalities who did not get a mandate could send a nationality spokesman to the National Assembly. The current political landscape in Hungary is dominated by the conservative Fidesz, who have a near supermajority, and three medium-sized parties, the left-wing Democratic Coalition (DK), the far-right Our Homeland Movement and liberal Momentum.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of communist dictatorship in 1989, a democratic form of government was established. Today’s parliament is still called Országgyűlés just like in royal times, but in order to differentiate between the historical royal diet is referred to as the «National Assembly» now. The Diet of Hungary was a legislative institution in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary from the 1290s,[144][145] and in its successor states, Royal Hungary and the Habsburg kingdom of Hungary throughout the early modern period. The articles of the 1790 diet set out that the diet should meet at least once every 3 years, but since the diet was called by the Habsburg monarchy, this promise was not kept on several occasions thereafter. As a result of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, it was reconstituted in 1867. The Latin term Natio Hungarica («Hungarian nation») was used to designate the political elite which had participation in the diet, consisting of the nobility, the Catholic clergy, and a few enfranchised burghers,[146][147] regardless of language or ethnicity.[148]

Law and judicial system

The judicial system of Hungary is a civil law system divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with jurisdiction over litigation between individuals and the public administration. Hungarian law is codified and based on German law and in a wider sense, civil law or Roman law. The court system for civil and criminal jurisdiction consists of local courts (járásbíróság), regional appellate courts (ítélőtábla), and the supreme court (Kúria). Hungary’s highest courts are located in Budapest.[149]

Law enforcement in Hungary is split among the police and the National Tax and Customs Administration. The Hungarian Police is the main and largest state law enforcement agency in Hungary. It carries nearly all general police duties such as criminal investigation, patrol activity, traffic policing, border control. It is led by the national police commissioner under the control of the Minister of the Interior. The body is divided into county police departments which are also divided into regional and town police departments. The National Police has subordinate agencies with nationwide jurisdiction, such as the «Nemzeti Nyomozó Iroda» (National Bureau of Investigation), a civilian police force specialised in investigating serious crimes, and the gendarmerie-like, militarised «Készenléti rendőrség» (Stand-by Police) mainly dealing with riots and often reinforcing local police forces. Because of Hungary’s accession to the Schengen Treaty, the police and border guards were merged into a single national corps, with the border guards (Határőrség Magyarországon) becoming police officers. This merger took place in January 2008. The Customs and Excise Authority remained subject to the Ministry of Finance under the National Tax and Customs Administration.[150]

Foreign relations

Meeting of the leaders of the Visegrád Group, Germany and France in 2013

The foreign policy is based on four basic commitments: to Atlantic co-operation, to European integration, to international development and to international law.[151] Hungary has been a member of the United Nations since December 1955 and a member of the European Union, NATO, the OECD, the Visegrád Group, the WTO, the World Bank, the AIIB and the IMF. Hungary took on the presidency of the Council of the European Union for half a year in 2011 and the next will be in 2024. In 2015, Hungary was the fifth largest OECD non-DAC donor of development aid in the world, which represents 0.13% of its Gross National Income.

Budapest is home to more than 100 embassies and representative bodies as an international political actor.[152] Hungary hosts the main and regional headquarters of many international organisations as well, including European Institute of Innovation and Technology, European Police College, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Centre for Democratic Transition, Institute of International Education, International Labour Organization, International Organization for Migration, International Red Cross, Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe, Danube Commission and others.[153]

Since 1989, the top foreign policy goal has been achieving integration into Western economic and security organisations. Hungary joined the Partnership for Peace programme in 1994 and has actively supported the IFOR and SFOR missions in Bosnia. Since 1989 Hungary has improved its often frosty neighbour relations by signing basic treaties with Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. These renounce all outstanding territorial claims and lay the foundation for constructive relations. However, the issue of ethnic Hungarian minority rights in Romania, Slovakia, and Serbia periodically cause bilateral tensions to flare up, although relations with Serbia have more recently become extremely close due to strong Hungarian advocacy for Serbian EU membership.[154] Since 2017, the relations with Ukraine rapidly deteriorated over the issue of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine.[155] Since 1989, Hungary has signed all of the OSCE documents, and served as the OSCE’s Chairman-in-Office in 1997. Historically, Hungary has had particularly friendly relations with Poland; this special relationship was recognised by the parliaments of both countries in 2007 with the joint declaration of 23 March as «The Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship».[156]

Military

The president holds the title of commander-in-chief of the nation’s armed forces. The Ministry of Defence jointly with chief of staff administers the armed forces, including the Hungarian Ground Force (HDF) and the Hungarian Air Force. Since 2007, the Hungarian Armed Forces has been under a unified command structure. The Ministry of Defence maintains political and civil control over the army. A subordinate Joint Forces Command coordinates and commands the HDF. In 2016, the armed forces had 31,080 personnel on active duty, the operative reserve brought the total number of troops to fifty thousand. In 2016, it was planned that military spending the following year would be $1.21 billion, about 0.94% of the country’s GDP, well below the NATO target of 2%. In 2012, the government adopted a resolution in which it pledged to increase defence spending to 1.4% of GDP by 2022.[157]

Military service is voluntary, though conscription may occur in wartime. In a significant move for modernisation, Hungary decided in 2001 to buy 14 JAS 39 Gripen fighter aircraft for about 800 million EUR. Hungarian National Cyber Security Center was re-organised in 2016 in order to become more efficient through cyber security.[158] In 2016, the Hungarian military had about 700 troops stationed in foreign countries as part of international peacekeeping forces, including 100 HDF troops in the NATO-led ISAF force in Afghanistan, 210 Hungarian soldiers in Kosovo under command of KFOR, and 160 troops in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Hungary sent a 300-strong logistics unit to Iraq in order to help the U.S. occupation with armed transport convoys, though public opinion opposed the country’s participation in the war.[citation needed]

Administrative divisions

Hungary is divided into 19 counties (vármegye). The capital (főváros) Budapest is an independent entity. The counties and the capital are the 20 NUTS third-level units of Hungary. The states are further subdivided into 174 districts (járás).[159] The districts are further divided into towns and villages, of which 25 are designated towns with county rights (megyei jogú város), sometimes known as «urban counties» in English. The local authorities of these towns have extended powers, but these towns belong to the territory of the respective district instead of being independent territorial units. County and district councils and municipalities have different roles and separate responsibilities relating to local government. The role of the counties are basically administrative and focus on strategic development, while preschools, public water utilities, garbage disposal, elderly care, and rescue services are administered by the municipalities.

Since 1996, the counties and city of Budapest have been grouped into seven regions for statistical and development purposes. These seven regions constitute NUTS’ second-level units of Hungary. They are Central Hungary, Central Transdanubia, Northern Great Plain, Northern Hungary, Southern Transdanubia, Southern Great Plain, and Western Transdanubia.

Counties of Hungary

Regions of Hungary

The districts of Hungary

Towns and villages in Hungary

| County (vármegye) |

Administrative centre |

Population | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kecskemét | 524,841 | Southern Great Plain | |

| Pécs | 391,455 | Southern Transdanubia | |

| Békéscsaba | 361,802 | Southern Great Plain | |

| Miskolc | 684,793 | Northern Hungary | |

| Budapest | 1,744,665 | Central Hungary | |

| Szeged | 421,827 | Southern Great Plain | |

| Székesfehérvár | 426,120 | Central Transdanubia | |

| Győr | 449,967 | Western Transdanubia | |

| Debrecen | 565,674 | Northern Great Plain | |

| Eger | 307,985 | Northern Hungary | |

| Szolnok | 386,752 | Northern Great Plain | |

| Tatabánya | 311,411 | Central Transdanubia | |

| Salgótarján | 201,919 | Northern Hungary | |

| Budapest | 1,237,561 | Central Hungary | |

| Kaposvár | 317,947 | Southern Transdanubia | |

| Nyíregyháza | 552,000 | Northern Great Plain | |

| Szekszárd | 231,183 | Southern Transdanubia | |

| Szombathely | 257,688 | Western Transdanubia | |

| Veszprém | 353,068 | Central Transdanubia | |

| Zalaegerszeg | 287,043 | Western Transdanubia |

Cities and towns

Budapest, the capital and most populous city of Hungary

Hungary has 3,152 municipalities as of 15 July 2013: 346 towns (Hungarian term: város, plural: városok; the terminology doesn’t distinguish between cities and towns – the term town is used in official translations) and 2,806 villages (Hungarian: község, plural: községek) which fully cover the territory of the country. The number of towns can change, since villages can be elevated to town status by act of the president. Budapest has a special status and is not included in any county while 23 of the towns are so-called urban counties (megyei jogú város – town with county rights). All county seats except Budapest are urban counties. Four of the cities (Budapest, Miskolc, Győr, and Pécs) have agglomerations, and the Hungarian Statistical Office distinguishes seventeen other areas in earlier stages of agglomeration development.[160] The largest city is Budapest, while the smallest town is Pálháza with 1,038 inhabitants in 2010. The largest village is Solymár with a population of 10,123 as of 2010. There are more than 100 villages with fewer than 100 inhabitants while the smallest villages have fewer than 20 inhabitants.

Economy

Hungary is an OECD high-income mixed economy with very high human development index and skilled labour force with the 16th lowest income inequality in the world.[161] Furthermore, it is the 9th most complex economy according to the Economic Complexity Index.[162] The economy is the 57th-largest in the world (out of 188 countries measured by IMF) with $265.037 billion output[163] and ranks 49th in the world in terms of GDP per capita measured by purchasing power parity. Hungary is an export-oriented market economy with a heavy emphasis on foreign trade, thus the country is the 36th largest export economy in the world. The country has more than $100 billion export in 2015 with high, $9.003 billion trade surplus, of which 79% went to the EU and 21% was extra-EU trade.[164] Hungary has a more than 80% privately owned economy with 39.1% overall taxation, which provides the basis for the country’s welfare economy. On the expenditure side, household consumption is the main component of GDP and accounts for 50% of its total use, followed by gross fixed capital formation with 22% and government expenditure with 20%.[165]

A proportional representation of Hungary’s exports, 2019

Hungary continues to be one of the leading nations for attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) in Central and Eastern Europe, the inward FDI in the country was $119.8 billion in 2015, while investing more than $50 billion abroad.[166] As of 2015, the key trading partners were Germany, Austria, Romania, Slovakia, France, Italy, Poland and Czech Republic.[167] Major industries include food processing, pharmaceuticals, motor vehicles, information technology, chemicals, metallurgy, machinery, electrical goods, and tourism (with 12.1 million international tourists in 2014).[168] Hungary is the largest electronics producer in Central and Eastern Europe. Electronics manufacturing and research are among the main drivers of innovation and economic growth in the country. In the past 20 years Hungary has also grown into a major centre for mobile technology, information security, and related hardware research.[169] The employment rate was 68.3% in 2017;[170] the employment structure shows the characteristics of post-industrial economies, 63.2% of employed workforce work in service sector, the industry contributed by 29.7%, while agriculture with 7.1%. Unemployment rate was 4.1% in 2017,[171] down from 11% during the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Hungary is part of the European single market which represents more than 508 million consumers. Several domestic commercial policies are determined by agreements among European Union members and by EU legislation.

Large Hungarian companies are included in the BUX, the stock market index listed on Budapest Stock Exchange. Well-known companies include the Fortune Global 500 firm MOL Group, the OTP Bank, Gedeon Richter Plc., Magyar Telekom, CIG Pannonia, FHB Bank, Zwack Unicum and more.[172] Besides this Hungary has a large portion of specialised small and medium enterprise, for example a significant number of automotive suppliers and technology start ups among others.[173]

Budapest is the financial and business capital, classified as an Alpha world city in the study by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[174] On the national level, Budapest is the primate city of Hungary regarding business and economy, accounting for 39% of the national income, the city has a gross metropolitan product more than $100 billion in 2015, making it one of the largest regional economies in the European Union.[175][176] Budapest is also among the Top 100 GDP performing cities in the world, measured by PricewaterhouseCoopers.[177] Furthermore, Hungary’s corporate tax rate is only 9%, which is relatively low for EU states.[178]

Hungary maintains its own currency, the Hungarian forint (HUF), although the economy fulfills the Maastricht criteria with the exception of public debt, but it is also significantly below the EU average with the level of 75.3% in 2015. The Hungarian National Bank—founded in 1924, after the dissolution of Austro-Hungarian Empire—is currently focusing on price stability with an inflation target of 3%.[179]

Science and technology

Hungary’s achievements in science and technology have been significant, and research and development efforts form an integral part of the country’s economy. Hungary spent 1.61% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on civil research and development in 2020, which is the 25th highest ratio in the world.[180] Hungary ranks 32nd among the most innovative countries in the Bloomberg Innovation Index.[181] Hungary was ranked 34th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 33rd in 2019.[182][183][184][185][186] In 2014, Hungary counted 2,651 full-time equivalent researchers per million inhabitants, steadily increasing from 2,131 in 2010 and compares with 3,984 in the U.S. or 4,380 in Germany.[187] Hungary’s high technology industry has benefited from both the country’s skilled workforce and the strong presence of foreign high-tech firms and research centres. Hungary also has one of the highest rates of filed patents, the sixth highest ratio of high-tech and medium high-tech output in the total industrial output, the 12th highest research FDI inflow, placed 14th in research talent in business enterprise and has the 17th best overall innovation efficiency ratio in the world.[188]

The key actor of research and development in Hungary is the National Research, Development and Innovation (NRDI) Office, which is a national strategic and funding agency for scientific research, development and innovation, the primary source of advice on RDI policy for the Hungarian government and the primary RDI funding agency. Its role is to develop RDI policy and ensure that Hungary adequately invest in RDI by funding excellent research and supporting innovation to increase competitiveness and to prepare the RDI strategy of the government, to handle the NRDI Fund and represents the government and RDI community in international organisations.[189]

Scientific research is supported partly by industry and partly by the state, through universities and by scientific state-institutions such as Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[190][191] Hungary has been the home of some of the most prominent researchers in various scientific disciplines, notably physics, mathematics, chemistry and engineering. As of 2018, thirteen Hungarian scientists have been recipients of a Nobel Prize.[192] Until 2012 three individuals—Csoma, János Bolyai and Tihanyi—were included in the UNESCO Memory of the World register as well as the collective contributions Tabula Hungariae and Bibliotheca Corviniana. Contemporary scientists include mathematician László Lovász, physicist Albert-László Barabási, physicist Ferenc Krausz, and biochemist Árpád Pusztai. Hungary has excellent mathematics education which has trained numerous outstanding scientists. Famous Hungarian mathematicians include father Farkas Bolyai and son János Bolyai, who was one of the founders of non-Euclidean geometry; Paul Erdős, famed for publishing in over forty languages and whose Erdős numbers are still tracked, and John von Neumann, a key contributor in the fields of quantum mechanics and game theory, a pioneer of digital computing, and the chief mathematician in the Manhattan Project. Notable Hungarian inventions include the lead dioxide match (János Irinyi), a type of carburetor (Donát Bánki, János Csonka), the electric (AC) train engine and generator (Kálmán Kandó), holography (Dennis Gabor), the Kalman filter (Rudolf E. Kálmán), and Rubik’s Cube (Ernő Rubik).

Transport

Hungary has a highly developed road, railway, air, and water transport system. Budapest serves as an important hub for the Hungarian railway system (MÁV). The capital is served by three large train stations called Keleti (Eastern), Nyugati (Western), and Déli (Southern) pályaudvars (terminuses). Szolnok is the most important railway hub outside Budapest, while Tiszai Railway Station in Miskolc and the main stations of Szombathely, Győr, Szeged, and Székesfehérvár are also key to the network.

Budapest, Debrecen, Miskolc, and Szeged have tram networks. The Budapest Metro is the second-oldest underground metro system in the world; its Line 1 dates from 1896. The system consists of four lines. A commuter rail system, HÉV, operates in the Budapest metropolitan area.

Hungary has a total length of approximately 1,314 km (816.48 mi) motorways (Hungarian: autópálya). Motorway sections are being added to the existing network, which already connects many major economically important cities to the capital. Ports are located at Budapest, Dunaújváros and Baja.

There are five international airports: Budapest Ferenc Liszt (informally called «Ferihegy»), Debrecen, Hévíz–Balaton (also called Sármellék Airport), Győr-Pér, and Pécs-Pogány, but only two of these (Budapest and Debrecen) receive scheduled flights. Low-budget airline Wizz Air is based at Ferihegy.

Energy

Hungary’s total energy supply is dominated by fossil fuels, with natural gas occupying the largest share, followed by oil and coal.[193] In June 2020, Hungary passed a law binding itself to a target of net-zero emissions by 2050. As part of a broader restructuring of the nation’s energy and climate policies, Hungary also extended its National Energy Strategy 2030 to look even further, adding an outlook until 2040 that prioritizes carbon-neutral and cost-effective energy while focusing on reinforcing energy security and energy independence.[193] Key forces in the country’s 2050 target include renewables, nuclear electricity, and electrification of end-use sectors. Significant investments in the power sector are expected, including for the construction of two new nuclear energy generating units. Renewable energy capacity has increased significantly, but in recent years growth in the renewables sector has stagnated. What is more, certain policies that limit development of wind power are expected to negatively impact the renewables sector.[193]

Hungary’s emission of greenhouse gases has dropped alongside the economy’s decreasing use of carbon-based fuels. However, independent analysis has identified space for Hungary to set more ambitious emissions reduction targets.[193]

Demographics

Population density in Hungary by district

Hungary’s population was 9,689,000 in 2021 according to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, making it the fifth most populous country in Central and Eastern Europe and medium-sized member state of the European Union. Population density stands at 107 inhabitants per square kilometre, which is about two times higher than the world average. More than one quarter of the population lived in the Budapest metropolitan area, 6,903,858 people (69.5%) in cities and towns overall.[194]

Like most other European countries, Hungary is experiencing sub-replacement fertility; its estimated total fertility rate of 1.43 children per woman is well below the replacement rate of 2.1,[195] albeit higher than its nadir of 1.28 in 1999,[196] and remains considerably below the high of 5.59 children born per woman in 1884.[197] As a result, its population has been gradually declining and rapidly aging. In 2011, the conservative government began a programme to increase the birth rate with a focus on ethnic Magyars by reinstating 3 year maternity leave as well as boosting part-time jobs. The fertility rate has gradually increased from 1.27 children born per woman in 2011.[198] The natural decrease in the first 10 months of 2016 was only 25,828 which was 8,162 less than the corresponding period in 2015.[199] In 2015, 47.9% of births were to unmarried women.[200] Hungary has one of the oldest populations in the world, with the average age of 42.7 years.[201] Life expectancy was 71.96 years for men and 79.62 years for women in 2015,[202] growing continuously since the fall of Communism.[203]

Hungary recognises two sizeable minority groups, designated as «national minorities» because their ancestors have lived in their respective regions for centuries in Hungary: a German community of about 130,000 that lives throughout the country, and a Romani minority that numbers around 300,000 and mainly resides in the northern part of the country. Some studies indicate a considerably larger number of Romani in Hungary (876,000 people – c. 9% of the population.).[204][205] According to the 2011 census, there were 8,314,029 (83.7%) ethnic Hungarians, 308,957 (3.1%) Romani, 131,951 (1.3%) Germans, 29,647 (0.3%) Slovaks, 26,345 (0.3%) Romanians, and 23,561 (0.2%) Croats in Hungary; 1,455,883 people (14.7% of the total population) did not declare their ethnicity. Thus, Hungarians made up more than 90% of people who declared their ethnicity.[4] In Hungary, people can declare more than one ethnicity, so the sum of ethnicities is higher than the total population.[206]

Today, approximately 5 million Hungarians live outside Hungary.

Languages

Regions of Central and Eastern Europe inhabited by Hungarian speakers today

Hungarian is the official and predominant spoken language. Hungarian is the 13th most widely spoken first language in Europe with around 13 million native speakers and it is one of 24 official and working languages of the European Union.[207] Outside Hungary, it is also spoken in neighbouring countries and by Hungarian diaspora communities worldwide. According to the 2011 census, 9,896,333 people (99.6%) speak Hungarian in Hungary, of whom 9,827,875 people (99%) speak it as a first language, while 68,458 people (0.7%) speak it as a second language.[4] English (1,589,180 speakers, 16.0%), and German (1,111,997 speakers, 11.2%) are the most widely spoken foreign languages, while there are several recognised minority languages in Hungary (Armenian, Bulgarian, Croatian, German, Greek, Romanian, Romani, Rusyn, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, and Ukrainian).[194]

Hungarian is a member of the Uralic language family, unrelated to any neighbouring language and distantly related to Finnish and Estonian. It is the largest of the Uralic languages in terms of the number of speakers and the only one spoken in Central Europe. There are sizeable populations of Hungarian speakers in Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, the former Yugoslavia, Ukraine, Israel, and the U.S. Smaller groups of Hungarian speakers live in Canada, Slovenia, and Austria, but also in Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela, and Chile. Standard Hungarian is based on the variety spoken Budapest. Although the use of the standard dialect is enforced, Hungarian has several urban and rural dialects.

Religion

Hungary is a historically Christian country. Hungarian historiography identifies the foundation of the Hungarian state with Stephen I’s baptism and coronation with the Holy Crown in A.D. 1000. Stephen promulgated Catholicism as the state religion, and his successors were traditionally known as the Apostolic Kings. The Catholic Church in Hungary remained strong through the centuries, and the Archbishop of Esztergom was granted extraordinary temporal privileges as prince-primate (hercegprímás) of Hungary.

Although contemporary Hungary has no official religion and recognises freedom of religion as a fundamental right, the constitution «recognises Christianity’s nation-building role» in its preamble[208] and in Article VII affirms that «the state may cooperate with the churches for community goals.»[209] The 2011 census showed that the majority of Hungarians were Christians (54.2%), with Roman Catholics (római katolikusok) (37.1%) and Hungarian Reformed Calvinists (reformátusok) (11.1%) making up the bulk of these alongside Lutherans (evangélikusok) (2.2%), Greek Catholics (1.8%), and other Christians (1.3%). Jewish (0.1%), Buddhist (0.1%) and Muslim (0.06%) communities are in the minority. 27.2% of the population did not declare a religious affiliation while 16.7% declared themselves explicitly irreligious, another 1.5% atheist.[4]

During the initial stages of the Protestant Reformation, most Hungarians adopted first Lutheranism and then Calvinism in the form of the Hungarian Reformed Church. In the second half of the 16th century, the Jesuits led a Counter-Reformation campaign, and the population once again became predominantly Catholic. This campaign was only partially successful, however, and the (mainly Reformed) Hungarian nobility were able to secure freedom of worship for Protestants. In practice, this meant cuius regio, eius religio; thus, most individual localities in Hungary are still identifiable as historically Catholic, Lutheran, or Reformed. The country’s eastern regions, especially around Debrecen (the «Calvinist Rome»), remain almost completely Reformed,[210] a trait they share with historically contiguous ethnically Hungarian regions across the Romanian border. Orthodox Christianity in Hungary is associated with the country’s ethnic minorities: Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Romanians, Rusyns, Ukrainians, and Serbs.

Historically, Hungary was home to a significant Jewish community with a pre-World War II population of more than 800,000, but it is estimated that just over 564,000 Hungarian Jews were killed between 1941 and 1945 during the Holocaust in Hungary.[211] Between 15 May and 9 July 1944 alone, over 434,000 Jews were deported on 147 trains,[212] most of them to Auschwitz, where about 80% were gassed on arrival. Some Jews were able to escape, but most were either deported to concentration camps, where they were killed by Arrow Cross members. From over 800,000 Jews living within Hungary’s borders in 1941–1944, about 255,500 are thought to have survived. There are about 120,000 Jews in Hungary today.[213][214]

Education

Education is predominantly public, run by the Ministry of Education. Preschool-kindergarten education is compulsory and provided for all children between three and six years old, after which school attendance is also compulsory until the age of sixteen.[28] Primary education usually lasts for eight years. Secondary education includes three traditional types of schools focused on different academic levels: the Gymnasium enrolls the most gifted children and prepares students for university studies; the secondary vocational schools for intermediate students lasts four years and the technical school prepares pupils for vocational education and the world of work. The system is partly flexible and bridges exist, graduates from a vocational school can achieve a two years programme to have access to vocational higher education for instance.[215] The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study rated 13–14-year-old pupils in Hungary among the best in the world for maths and science.

Most of the universities are public institutions, and students traditionally study without fee payment. The general requirement for university is the Matura. The Hungarian public higher education system includes universities and other higher education institutes, that provide both education curricula and related degrees up to doctoral degree and also contribute to research activities. Health insurance for students is free until the end of their studies. English and German language are important in Hungarian higher education, there are a number of degree programmes that are taught in these languages, which attracts thousands of exchange students every year. Hungary’s higher education and training has been ranked 44 out of 148 countries in the Global Competitiveness Report 2014.[216]

Hungary has a long tradition of higher education reflecting the existence of established knowledge economy. The established universities include some of the oldest in the world, the first was the University of Pécs founded in 1367 which is still functioning, although in 1276, the university of Veszprém was destroyed by the troops of Peter Csák but it was never rebuilt. Sigismund established Óbuda University in 1395. Another, Universitas Istropolitana, was established 1465 in Pozsony by Matthias Corvinus. Nagyszombat University was founded in 1635 and moved to Buda in 1777, and it is called Eötvös Loránd University today. The world’s first institute of technology was founded in Selmecbánya in 1735; its legal successor is the University of Miskolc. The Budapest University of Technology and Economics is considered the oldest institute of technology in the world with university rank and structure, its legal predecessor the Institutum Geometrico-Hydrotechnicum was founded in 1782 by Emperor Joseph II.