| Internal energy | |

|---|---|

|

Common symbols |

U |

| SI unit | J |

| In SI base units | m2⋅kg/s2 |

|

Derivations from |

|

The internal energy of a thermodynamic system is the total energy contained within it. It is the energy necessary to create or prepare the system in its given internal state, and includes the contributions of potential energy and internal kinetic energy. It keeps account of the gains and losses of energy of the system that are due to changes in its internal state.[1][2] It does not include the kinetic energy of motion of the system as a whole, or any external energies from surrounding force fields. The internal energy of an isolated system is constant, which is expressed as the law of conservation of energy, a foundation of the first law of thermodynamics. The internal energy is an extensive property.

The internal energy cannot be measured directly and knowledge of all its components is rarely interesting, such as the static rest mass energy of its constituent matter. Thermodynamics is chiefly concerned only with changes in the internal energy, not with its absolute value. Instead, it is customary to define a reference state, and measure any changes in a thermodynamic process from this state. The processes that change the internal energy are transfers of matter, or of energy as heat, or by thermodynamic work.[3] These processes are measured by changes in the system’s properties, such as temperature, entropy, volume, and molar constitution. When transfer of matter is prevented by impermeable containing walls, the system is said to be closed. If the containing walls pass neither matter nor energy, the system is said to be isolated and its internal energy cannot change.

The internal energy depends only on the state of the system and not on the particular choice from many possible processes by which energy may pass to or from the system. It is a thermodynamic potential. Microscopically, the internal energy can be analyzed in terms of the kinetic energy of microscopic motion of the system’s particles from translations, rotations, and vibrations, and of the potential energy associated with microscopic forces, including chemical bonds.

The unit of energy in the International System of Units (SI) is the joule (J). The internal energy relative to the mass with unit J/kg is the specific internal energy. The corresponding quantity relative to the amount of substance with unit J/mol is the molar internal energy.[4]

Cardinal functions[edit]

The internal energy of a system depends on its entropy S, its volume V and its number of massive particles: U(S,V,{Nj}). It expresses the thermodynamics of a system in the energy representation. As a function of state, its arguments are exclusively extensive variables of state. Alongside the internal energy, the other cardinal function of state of a thermodynamic system is its entropy, as a function, S(U,V,{Nj}), of the same list of extensive variables of state, except that the entropy, S, is replaced in the list by the internal energy, U. It expresses the entropy representation.[5][6][7]

Each cardinal function is a monotonic function of each of its natural or canonical variables. Each provides its characteristic or fundamental equation, for example U = U(S,V,{Nj}), that by itself contains all thermodynamic information about the system. The fundamental equations for the two cardinal functions can in principle be interconverted by solving, for example, U = U(S,V,{Nj}) for S, to get S = S(U,V,{Nj}).

In contrast, Legendre transforms are necessary to derive fundamental equations for other thermodynamic potentials and Massieu functions. The entropy as a function only of extensive state variables is the one and only cardinal function of state for the generation of Massieu functions. It is not itself customarily designated a ‘Massieu function’, though rationally it might be thought of as such, corresponding to the term ‘thermodynamic potential’, which includes the internal energy.[6][8][9]

For real and practical systems, explicit expressions of the fundamental equations are almost always unavailable, but the functional relations exist in principle. Formal, in principle, manipulations of them are valuable for the understanding of thermodynamics.

Description and definition[edit]

The internal energy

where

and the

It is the energy needed to create the given state of the system from the reference state. From a non-relativistic microscopic point of view, it may be divided into microscopic potential energy,

The microscopic kinetic energy of a system arises as the sum of the motions of all the system’s particles with respect to the center-of-mass frame, whether it be the motion of atoms, molecules, atomic nuclei, electrons, or other particles. The microscopic potential energy algebraic summative components are those of the chemical and nuclear particle bonds, and the physical force fields within the system, such as due to internal induced electric or magnetic dipole moment, as well as the energy of deformation of solids (stress-strain). Usually, the split into microscopic kinetic and potential energies is outside the scope of macroscopic thermodynamics.

Internal energy does not include the energy due to motion or location of a system as a whole. That is to say, it excludes any kinetic or potential energy the body may have because of its motion or location in external gravitational, electrostatic, or electromagnetic fields. It does, however, include the contribution of such a field to the energy due to the coupling of the internal degrees of freedom of the object with the field. In such a case, the field is included in the thermodynamic description of the object in the form of an additional external parameter.

For practical considerations in thermodynamics or engineering, it is rarely necessary, convenient, nor even possible, to consider all energies belonging to the total intrinsic energy of a sample system, such as the energy given by the equivalence of mass. Typically, descriptions only include components relevant to the system under study. Indeed, in most systems under consideration, especially through thermodynamics, it is impossible to calculate the total internal energy.[10] Therefore, a convenient null reference point may be chosen for the internal energy.

The internal energy is an extensive property: it depends on the size of the system, or on the amount of substance it contains.

At any temperature greater than absolute zero, microscopic potential energy and kinetic energy are constantly converted into one another, but the sum remains constant in an isolated system (cf. table). In the classical picture of thermodynamics, kinetic energy vanishes at zero temperature and the internal energy is purely potential energy. However, quantum mechanics has demonstrated that even at zero temperature particles maintain a residual energy of motion, the zero point energy. A system at absolute zero is merely in its quantum-mechanical ground state, the lowest energy state available. At absolute zero a system of given composition has attained its minimum attainable entropy.

The microscopic kinetic energy portion of the internal energy gives rise to the temperature of the system. Statistical mechanics relates the pseudo-random kinetic energy of individual particles to the mean kinetic energy of the entire ensemble of particles comprising a system. Furthermore, it relates the mean microscopic kinetic energy to the macroscopically observed empirical property that is expressed as temperature of the system. While temperature is an intensive measure, this energy expresses the concept as an extensive property of the system, often referred to as the thermal energy,[11][12] The scaling property between temperature and thermal energy is the entropy change of the system.

Statistical mechanics considers any system to be statistically distributed across an ensemble of

This is the statistical expression of the law of conservation of energy.

| Type of system | Mass flow | Work | Heat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open | |||

| Closed | |||

| Thermally isolated | |||

| Mechanically isolated | |||

| Isolated |

Internal energy changes[edit]

Thermodynamics is chiefly concerned with the changes in internal energy

For a closed system, with matter transfer excluded, the changes in internal energy are due to heat transfer

When a closed system receives energy as heat, this energy increases the internal energy. It is distributed between microscopic kinetic and microscopic potential energies. In general, thermodynamics does not trace this distribution. In an ideal gas all of the extra energy results in a temperature increase, as it is stored solely as microscopic kinetic energy; such heating is said to be sensible.

A second kind of mechanism of change in the internal energy of a closed system changed is in its doing of work on its surroundings. Such work may be simply mechanical, as when the system expands to drive a piston, or, for example, when the system changes its electric polarization so as to drive a change in the electric field in the surroundings.

If the system is not closed, the third mechanism that can increase the internal energy is transfer of matter into the system. This increase,

If a system undergoes certain phase transformations while being heated, such as melting and vaporization, it may be observed that the temperature of the system does not change until the entire sample has completed the transformation. The energy introduced into the system while the temperature does not change is called latent energy or latent heat, in contrast to sensible heat, which is associated with temperature change.

Internal energy of the ideal gas[edit]

Thermodynamics often uses the concept of the ideal gas for teaching purposes, and as an approximation for working systems. The ideal gas consists of particles considered as point objects that interact only by elastic collisions and fill a volume such that their mean free path between collisions is much larger than their diameter. Such systems approximate monatomic gases such as helium and other noble gases. For an ideal gas the kinetic energy consists only of the translational energy of the individual atoms. Monatomic particles do not possess rotational or vibrational degrees of freedom, and are not electronically excited to higher energies except at very high temperatures.

Therefore, the internal energy of an ideal gas depends solely on its temperature (and the number of gas particles):

The internal energy of an ideal gas is proportional to its mass (number of moles)

where

where

Internal energy of a closed thermodynamic system[edit]

The above summation of all components of change in internal energy assumes that a positive energy denotes heat added to the system or the negative of work done by the system on its surroundings.[note 1]

This relationship may be expressed in infinitesimal terms using the differentials of each term, though only the internal energy is an exact differential.[14]: 33 For a closed system, with transfers only as heat and work, the change in the internal energy is

expressing the first law of thermodynamics. It may be expressed in terms of other thermodynamic parameters. Each term is composed of an intensive variable (a generalized force) and its conjugate infinitesimal extensive variable (a generalized displacement).

For example, the mechanical work done by the system may be related to the pressure

This defines the direction of work,

where

The change in internal energy becomes

Changes due to temperature and volume[edit]

The expression relating changes in internal energy to changes in temperature and volume is

|

|

(1) |

This is useful if the equation of state is known.

In case of an ideal gas, we can derive that

Changes due to temperature and pressure[edit]

When considering fluids or solids, an expression in terms of the temperature and pressure is usually more useful:

where it is assumed that the heat capacity at constant pressure is related to the heat capacity at constant volume according to

Changes due to volume at constant temperature[edit]

The internal pressure is defined as a partial derivative of the internal energy with respect to the volume at constant temperature:

Internal energy of multi-component systems[edit]

In addition to including the entropy

where

where

which shows (or defines) temperature

and where the coefficients

As conjugate variables to the composition

The sum over the composition of the system is the Gibbs free energy:

that arises from changing the composition of the system at constant temperature and pressure. For a single component system, the chemical potential equals the Gibbs energy per amount of substance, i.e. particles or moles according to the original definition of the unit for

Internal energy in an elastic medium[edit]

For an elastic medium the mechanical energy term of the internal energy is expressed in terms of the stress

Euler’s theorem yields for the internal energy:[16]

For a linearly elastic material, the stress is related to the strain by

where the

Elastic deformations, such as sound, passing through a body, or other forms of macroscopic internal agitation or turbulent motion create states when the system is not in thermodynamic equilibrium. While such energies of motion continue, they contribute to the total energy of the system; thermodynamic internal energy pertains only when such motions have ceased.

History[edit]

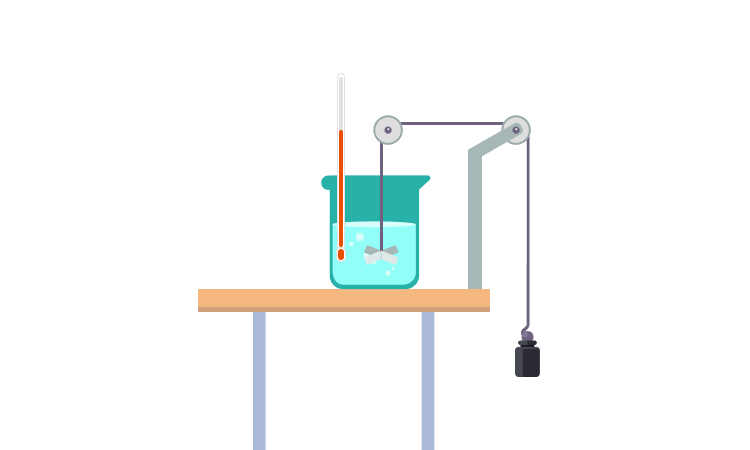

James Joule studied the relationship between heat, work, and temperature. He observed that friction in a liquid, such as caused by its agitation with work by a paddle wheel, caused an increase in its temperature, which he described as producing a quantity of heat. Expressed in modern units, he found that c. 4186 joules of energy were needed to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water by one degree Celsius.[17]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c This article uses the sign convention of the mechanical work as often defined in engineering, which is different from the convention used in physics and chemistry, where work performed by the system against the environment, e.g., a system expansion, is negative, while in engineering, this is taken to be positive.

See also[edit]

- Calorimetry

- Enthalpy

- Exergy

- Thermodynamic equations

- Thermodynamic potentials

- Gibbs free energy

- Helmholtz free energy

References[edit]

- ^ Crawford, F. H. (1963), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Haase, R. (1971), pp. 24–28.

- ^ a b Born, M. (1949), Appendix 8, pp. 146–149.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Physical and Biophysical Chemistry Division (2007). Quantities, units, and symbols in physical chemistry (PDF) (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: RSC Pub. ISBN 978-1-84755-788-9. OCLC 232639283.

- ^ Tschoegl, N.W. (2000), p. 17.

- ^ a b Callen, H.B. (1960/1985), Chapter 5.

- ^ Münster, A. (1970), p. 6.

- ^ Münster, A. (1970), Chapter 3.

- ^ Bailyn, M. (1994), pp. 206–209.

- ^ I. Klotz, R. Rosenberg, Chemical Thermodynamics — Basic Concepts and Methods, 7th ed., Wiley (2008), p.39

- ^ Leland, T. W. Jr., Mansoori, G. A., pp. 15, 16.

- ^ Thermal energy – Hyperphysics.

- ^ van Gool, W.; Bruggink, J.J.C., eds. (1985). Energy and time in the economic and physical sciences. North-Holland. pp. 41–56. ISBN 978-0444877482.

- ^ Adkins, C. J. (Clement John) (1983). Equilibrium thermodynamics (3rd ed.). Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25445-0. OCLC 9132054.

- ^ Landau, Lev Davidovich; Lifshit︠s︡, Evgeniĭ Mikhaĭlovich; Pitaevskiĭ, Lev Petrovich; Sykes, John Bradbury; Kearsley, M. J. (1980). Statistical physics. Oxford. p. 70. ISBN 0-08-023039-3. OCLC 3932994.

- ^ Landau & Lifshitz 1986, p. 8.

- ^ Joule, J.P. (1850). «On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 140: 61–82. doi:10.1098/rstl.1850.0004.

Bibliography of cited references[edit]

- Adkins, C. J. (1968/1975). Equilibrium Thermodynamics, second edition, McGraw-Hill, London, ISBN 0-07-084057-1.

- Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics Press, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3.

- Born, M. (1949). Natural Philosophy of Cause and Chance, Oxford University Press, London.

- Callen, H. B. (1960/1985), Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, (first edition 1960), second edition 1985, John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN 0-471-86256-8.

- Crawford, F. H. (1963). Heat, Thermodynamics, and Statistical Physics, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

- Haase, R. (1971). Survey of Fundamental Laws, chapter 1 of Thermodynamics, pages 1–97 of volume 1, ed. W. Jost, of Physical Chemistry. An Advanced Treatise, ed. H. Eyring, D. Henderson, W. Jost, Academic Press, New York, lcn 73–117081.

- Thomas W. Leland Jr., G. A. Mansoori (ed.), Basic Principles of Classical and Statistical Thermodynamics (PDF).

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1986). Theory of Elasticity (Course of Theoretical Physics Volume 7). (Translated from Russian by J. B. Sykes and W. H. Reid) (Third ed.). Boston, MA: Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-2633-0.

- Münster, A. (1970), Classical Thermodynamics, translated by E. S. Halberstadt, Wiley–Interscience, London, ISBN 0-471-62430-6.

- Planck, M., (1923/1927). Treatise on Thermodynamics, translated by A. Ogg, third English edition, Longmans, Green and Co., London.

- Tschoegl, N. W. (2000). Fundamentals of Equilibrium and Steady-State Thermodynamics, Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN 0-444-50426-5.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alberty, R. A. (2001). «Use of Legendre transforms in chemical thermodynamics» (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 73 (8): 1349–1380. doi:10.1351/pac200173081349. S2CID 98264934.

- Lewis, Gilbert Newton; Randall, Merle: Revised by Pitzer, Kenneth S. & Brewer, Leo (1961). Thermodynamics (2nd ed.). New York, NY USA: McGraw-Hill Book Co. ISBN 978-0-07-113809-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

| Internal energy | |

|---|---|

|

Common symbols |

U |

| SI unit | J |

| In SI base units | m2⋅kg/s2 |

|

Derivations from |

|

The internal energy of a thermodynamic system is the total energy contained within it. It is the energy necessary to create or prepare the system in its given internal state, and includes the contributions of potential energy and internal kinetic energy. It keeps account of the gains and losses of energy of the system that are due to changes in its internal state.[1][2] It does not include the kinetic energy of motion of the system as a whole, or any external energies from surrounding force fields. The internal energy of an isolated system is constant, which is expressed as the law of conservation of energy, a foundation of the first law of thermodynamics. The internal energy is an extensive property.

The internal energy cannot be measured directly and knowledge of all its components is rarely interesting, such as the static rest mass energy of its constituent matter. Thermodynamics is chiefly concerned only with changes in the internal energy, not with its absolute value. Instead, it is customary to define a reference state, and measure any changes in a thermodynamic process from this state. The processes that change the internal energy are transfers of matter, or of energy as heat, or by thermodynamic work.[3] These processes are measured by changes in the system’s properties, such as temperature, entropy, volume, and molar constitution. When transfer of matter is prevented by impermeable containing walls, the system is said to be closed. If the containing walls pass neither matter nor energy, the system is said to be isolated and its internal energy cannot change.

The internal energy depends only on the state of the system and not on the particular choice from many possible processes by which energy may pass to or from the system. It is a thermodynamic potential. Microscopically, the internal energy can be analyzed in terms of the kinetic energy of microscopic motion of the system’s particles from translations, rotations, and vibrations, and of the potential energy associated with microscopic forces, including chemical bonds.

The unit of energy in the International System of Units (SI) is the joule (J). The internal energy relative to the mass with unit J/kg is the specific internal energy. The corresponding quantity relative to the amount of substance with unit J/mol is the molar internal energy.[4]

Cardinal functions[edit]

The internal energy of a system depends on its entropy S, its volume V and its number of massive particles: U(S,V,{Nj}). It expresses the thermodynamics of a system in the energy representation. As a function of state, its arguments are exclusively extensive variables of state. Alongside the internal energy, the other cardinal function of state of a thermodynamic system is its entropy, as a function, S(U,V,{Nj}), of the same list of extensive variables of state, except that the entropy, S, is replaced in the list by the internal energy, U. It expresses the entropy representation.[5][6][7]

Each cardinal function is a monotonic function of each of its natural or canonical variables. Each provides its characteristic or fundamental equation, for example U = U(S,V,{Nj}), that by itself contains all thermodynamic information about the system. The fundamental equations for the two cardinal functions can in principle be interconverted by solving, for example, U = U(S,V,{Nj}) for S, to get S = S(U,V,{Nj}).

In contrast, Legendre transforms are necessary to derive fundamental equations for other thermodynamic potentials and Massieu functions. The entropy as a function only of extensive state variables is the one and only cardinal function of state for the generation of Massieu functions. It is not itself customarily designated a ‘Massieu function’, though rationally it might be thought of as such, corresponding to the term ‘thermodynamic potential’, which includes the internal energy.[6][8][9]

For real and practical systems, explicit expressions of the fundamental equations are almost always unavailable, but the functional relations exist in principle. Formal, in principle, manipulations of them are valuable for the understanding of thermodynamics.

Description and definition[edit]

The internal energy

where

and the

It is the energy needed to create the given state of the system from the reference state. From a non-relativistic microscopic point of view, it may be divided into microscopic potential energy,

The microscopic kinetic energy of a system arises as the sum of the motions of all the system’s particles with respect to the center-of-mass frame, whether it be the motion of atoms, molecules, atomic nuclei, electrons, or other particles. The microscopic potential energy algebraic summative components are those of the chemical and nuclear particle bonds, and the physical force fields within the system, such as due to internal induced electric or magnetic dipole moment, as well as the energy of deformation of solids (stress-strain). Usually, the split into microscopic kinetic and potential energies is outside the scope of macroscopic thermodynamics.

Internal energy does not include the energy due to motion or location of a system as a whole. That is to say, it excludes any kinetic or potential energy the body may have because of its motion or location in external gravitational, electrostatic, or electromagnetic fields. It does, however, include the contribution of such a field to the energy due to the coupling of the internal degrees of freedom of the object with the field. In such a case, the field is included in the thermodynamic description of the object in the form of an additional external parameter.

For practical considerations in thermodynamics or engineering, it is rarely necessary, convenient, nor even possible, to consider all energies belonging to the total intrinsic energy of a sample system, such as the energy given by the equivalence of mass. Typically, descriptions only include components relevant to the system under study. Indeed, in most systems under consideration, especially through thermodynamics, it is impossible to calculate the total internal energy.[10] Therefore, a convenient null reference point may be chosen for the internal energy.

The internal energy is an extensive property: it depends on the size of the system, or on the amount of substance it contains.

At any temperature greater than absolute zero, microscopic potential energy and kinetic energy are constantly converted into one another, but the sum remains constant in an isolated system (cf. table). In the classical picture of thermodynamics, kinetic energy vanishes at zero temperature and the internal energy is purely potential energy. However, quantum mechanics has demonstrated that even at zero temperature particles maintain a residual energy of motion, the zero point energy. A system at absolute zero is merely in its quantum-mechanical ground state, the lowest energy state available. At absolute zero a system of given composition has attained its minimum attainable entropy.

The microscopic kinetic energy portion of the internal energy gives rise to the temperature of the system. Statistical mechanics relates the pseudo-random kinetic energy of individual particles to the mean kinetic energy of the entire ensemble of particles comprising a system. Furthermore, it relates the mean microscopic kinetic energy to the macroscopically observed empirical property that is expressed as temperature of the system. While temperature is an intensive measure, this energy expresses the concept as an extensive property of the system, often referred to as the thermal energy,[11][12] The scaling property between temperature and thermal energy is the entropy change of the system.

Statistical mechanics considers any system to be statistically distributed across an ensemble of

This is the statistical expression of the law of conservation of energy.

| Type of system | Mass flow | Work | Heat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open | |||

| Closed | |||

| Thermally isolated | |||

| Mechanically isolated | |||

| Isolated |

Internal energy changes[edit]

Thermodynamics is chiefly concerned with the changes in internal energy

For a closed system, with matter transfer excluded, the changes in internal energy are due to heat transfer

When a closed system receives energy as heat, this energy increases the internal energy. It is distributed between microscopic kinetic and microscopic potential energies. In general, thermodynamics does not trace this distribution. In an ideal gas all of the extra energy results in a temperature increase, as it is stored solely as microscopic kinetic energy; such heating is said to be sensible.

A second kind of mechanism of change in the internal energy of a closed system changed is in its doing of work on its surroundings. Such work may be simply mechanical, as when the system expands to drive a piston, or, for example, when the system changes its electric polarization so as to drive a change in the electric field in the surroundings.

If the system is not closed, the third mechanism that can increase the internal energy is transfer of matter into the system. This increase,

If a system undergoes certain phase transformations while being heated, such as melting and vaporization, it may be observed that the temperature of the system does not change until the entire sample has completed the transformation. The energy introduced into the system while the temperature does not change is called latent energy or latent heat, in contrast to sensible heat, which is associated with temperature change.

Internal energy of the ideal gas[edit]

Thermodynamics often uses the concept of the ideal gas for teaching purposes, and as an approximation for working systems. The ideal gas consists of particles considered as point objects that interact only by elastic collisions and fill a volume such that their mean free path between collisions is much larger than their diameter. Such systems approximate monatomic gases such as helium and other noble gases. For an ideal gas the kinetic energy consists only of the translational energy of the individual atoms. Monatomic particles do not possess rotational or vibrational degrees of freedom, and are not electronically excited to higher energies except at very high temperatures.

Therefore, the internal energy of an ideal gas depends solely on its temperature (and the number of gas particles):

The internal energy of an ideal gas is proportional to its mass (number of moles)

where

where

Internal energy of a closed thermodynamic system[edit]

The above summation of all components of change in internal energy assumes that a positive energy denotes heat added to the system or the negative of work done by the system on its surroundings.[note 1]

This relationship may be expressed in infinitesimal terms using the differentials of each term, though only the internal energy is an exact differential.[14]: 33 For a closed system, with transfers only as heat and work, the change in the internal energy is

expressing the first law of thermodynamics. It may be expressed in terms of other thermodynamic parameters. Each term is composed of an intensive variable (a generalized force) and its conjugate infinitesimal extensive variable (a generalized displacement).

For example, the mechanical work done by the system may be related to the pressure

This defines the direction of work,

where

The change in internal energy becomes

Changes due to temperature and volume[edit]

The expression relating changes in internal energy to changes in temperature and volume is

|

|

(1) |

This is useful if the equation of state is known.

In case of an ideal gas, we can derive that

Changes due to temperature and pressure[edit]

When considering fluids or solids, an expression in terms of the temperature and pressure is usually more useful:

where it is assumed that the heat capacity at constant pressure is related to the heat capacity at constant volume according to

Changes due to volume at constant temperature[edit]

The internal pressure is defined as a partial derivative of the internal energy with respect to the volume at constant temperature:

Internal energy of multi-component systems[edit]

In addition to including the entropy

where

where

which shows (or defines) temperature

and where the coefficients

As conjugate variables to the composition

The sum over the composition of the system is the Gibbs free energy:

that arises from changing the composition of the system at constant temperature and pressure. For a single component system, the chemical potential equals the Gibbs energy per amount of substance, i.e. particles or moles according to the original definition of the unit for

Internal energy in an elastic medium[edit]

For an elastic medium the mechanical energy term of the internal energy is expressed in terms of the stress

Euler’s theorem yields for the internal energy:[16]

For a linearly elastic material, the stress is related to the strain by

where the

Elastic deformations, such as sound, passing through a body, or other forms of macroscopic internal agitation or turbulent motion create states when the system is not in thermodynamic equilibrium. While such energies of motion continue, they contribute to the total energy of the system; thermodynamic internal energy pertains only when such motions have ceased.

History[edit]

James Joule studied the relationship between heat, work, and temperature. He observed that friction in a liquid, such as caused by its agitation with work by a paddle wheel, caused an increase in its temperature, which he described as producing a quantity of heat. Expressed in modern units, he found that c. 4186 joules of energy were needed to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water by one degree Celsius.[17]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c This article uses the sign convention of the mechanical work as often defined in engineering, which is different from the convention used in physics and chemistry, where work performed by the system against the environment, e.g., a system expansion, is negative, while in engineering, this is taken to be positive.

See also[edit]

- Calorimetry

- Enthalpy

- Exergy

- Thermodynamic equations

- Thermodynamic potentials

- Gibbs free energy

- Helmholtz free energy

References[edit]

- ^ Crawford, F. H. (1963), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Haase, R. (1971), pp. 24–28.

- ^ a b Born, M. (1949), Appendix 8, pp. 146–149.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Physical and Biophysical Chemistry Division (2007). Quantities, units, and symbols in physical chemistry (PDF) (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: RSC Pub. ISBN 978-1-84755-788-9. OCLC 232639283.

- ^ Tschoegl, N.W. (2000), p. 17.

- ^ a b Callen, H.B. (1960/1985), Chapter 5.

- ^ Münster, A. (1970), p. 6.

- ^ Münster, A. (1970), Chapter 3.

- ^ Bailyn, M. (1994), pp. 206–209.

- ^ I. Klotz, R. Rosenberg, Chemical Thermodynamics — Basic Concepts and Methods, 7th ed., Wiley (2008), p.39

- ^ Leland, T. W. Jr., Mansoori, G. A., pp. 15, 16.

- ^ Thermal energy – Hyperphysics.

- ^ van Gool, W.; Bruggink, J.J.C., eds. (1985). Energy and time in the economic and physical sciences. North-Holland. pp. 41–56. ISBN 978-0444877482.

- ^ Adkins, C. J. (Clement John) (1983). Equilibrium thermodynamics (3rd ed.). Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25445-0. OCLC 9132054.

- ^ Landau, Lev Davidovich; Lifshit︠s︡, Evgeniĭ Mikhaĭlovich; Pitaevskiĭ, Lev Petrovich; Sykes, John Bradbury; Kearsley, M. J. (1980). Statistical physics. Oxford. p. 70. ISBN 0-08-023039-3. OCLC 3932994.

- ^ Landau & Lifshitz 1986, p. 8.

- ^ Joule, J.P. (1850). «On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 140: 61–82. doi:10.1098/rstl.1850.0004.

Bibliography of cited references[edit]

- Adkins, C. J. (1968/1975). Equilibrium Thermodynamics, second edition, McGraw-Hill, London, ISBN 0-07-084057-1.

- Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics Press, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3.

- Born, M. (1949). Natural Philosophy of Cause and Chance, Oxford University Press, London.

- Callen, H. B. (1960/1985), Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, (first edition 1960), second edition 1985, John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN 0-471-86256-8.

- Crawford, F. H. (1963). Heat, Thermodynamics, and Statistical Physics, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

- Haase, R. (1971). Survey of Fundamental Laws, chapter 1 of Thermodynamics, pages 1–97 of volume 1, ed. W. Jost, of Physical Chemistry. An Advanced Treatise, ed. H. Eyring, D. Henderson, W. Jost, Academic Press, New York, lcn 73–117081.

- Thomas W. Leland Jr., G. A. Mansoori (ed.), Basic Principles of Classical and Statistical Thermodynamics (PDF).

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1986). Theory of Elasticity (Course of Theoretical Physics Volume 7). (Translated from Russian by J. B. Sykes and W. H. Reid) (Third ed.). Boston, MA: Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-2633-0.

- Münster, A. (1970), Classical Thermodynamics, translated by E. S. Halberstadt, Wiley–Interscience, London, ISBN 0-471-62430-6.

- Planck, M., (1923/1927). Treatise on Thermodynamics, translated by A. Ogg, third English edition, Longmans, Green and Co., London.

- Tschoegl, N. W. (2000). Fundamentals of Equilibrium and Steady-State Thermodynamics, Elsevier, Amsterdam, ISBN 0-444-50426-5.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alberty, R. A. (2001). «Use of Legendre transforms in chemical thermodynamics» (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 73 (8): 1349–1380. doi:10.1351/pac200173081349. S2CID 98264934.

- Lewis, Gilbert Newton; Randall, Merle: Revised by Pitzer, Kenneth S. & Brewer, Leo (1961). Thermodynamics (2nd ed.). New York, NY USA: McGraw-Hill Book Co. ISBN 978-0-07-113809-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Содержание:

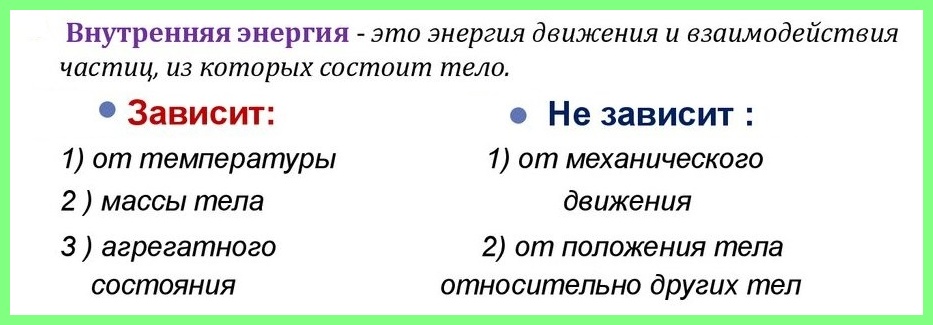

Внутренняя энергия:

Вы знаете, что движущееся тело обладает кинетической энергией. А если оно еще и взаимодействует с другим телом, то обладает потенциальной энергией. Оба вида энергии представляют собой механическую энергию. Они взаимно превращаемы: кинетическая энергия может переходить в потенциальную и наоборот. Кроме того, вы знаете, что любое тело имеет дискретную структуру, т. е. состоит из частиц (атомов, молекул). Частицы находятся в непрерывном хаотическом движении. А частицы жидкости и твердого тела еще и взаимодействуют между собой. Следовательно, частицы обладают кинетической, а частицы жидкости и твердых тел — еще и потенциальной энергией. Сумма кинетической и потенциальной энергий всех частиц тела называется внутренней энергией. Внутренняя энергия измеряется в джоулях. Чем отличается внутренняя энергия от механической? В чем ее особенности? Может ли механическая энергия переходить во внутреннюю?

Для ответа на эти вопросы рассмотрим пример. Шайба, двигавшаяся горизонтально по льду (рис. 1), остановилась. Как изменилась ее механическая энергия относительно льда?

Кинетическая энергия шайбы уменьшилась до нуля. Положение шайбы над уровнем льда не изменилось, шайба не деформировалась. Значит, изменение потенциальной энергии равно нулю. Означает ли это, что се механическая (кинетическая) энергия исчезла бесследно? Нет. Механическая энергия шайбы перешла во внутреннюю энергию шайбы и льда.

А может ли внутренняя энергия тела, как механическая, быть равной нулю? Движение частиц, из которых состоит тело, не прекращается даже при самых низких температурах. Значит, тело всегда (подчеркиваем, всегда) обладает некоторым запасом внутренней энергии. Его можно либо увеличить, либо уменьшить — и только!

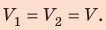

Велико ли значение внутренней энергии тела? Энергия одной частицы, например кинетическая, в силу незначительности ее массы чрезвычайно мала. Расчеты для средней энергии поступательного движения молекулы кислорода показывают, что ее значение при комнатной температуре

Главные выводы:

- Независимо от того, есть у тела механическая энергия или нет, оно обладает внутренней энергией.

- Внутренняя энергия тела равна сумме кинетической и потенциальной энергий частиц, из которых оно состоит.

- Внутренняя энергия тела всегда не равна нулю.

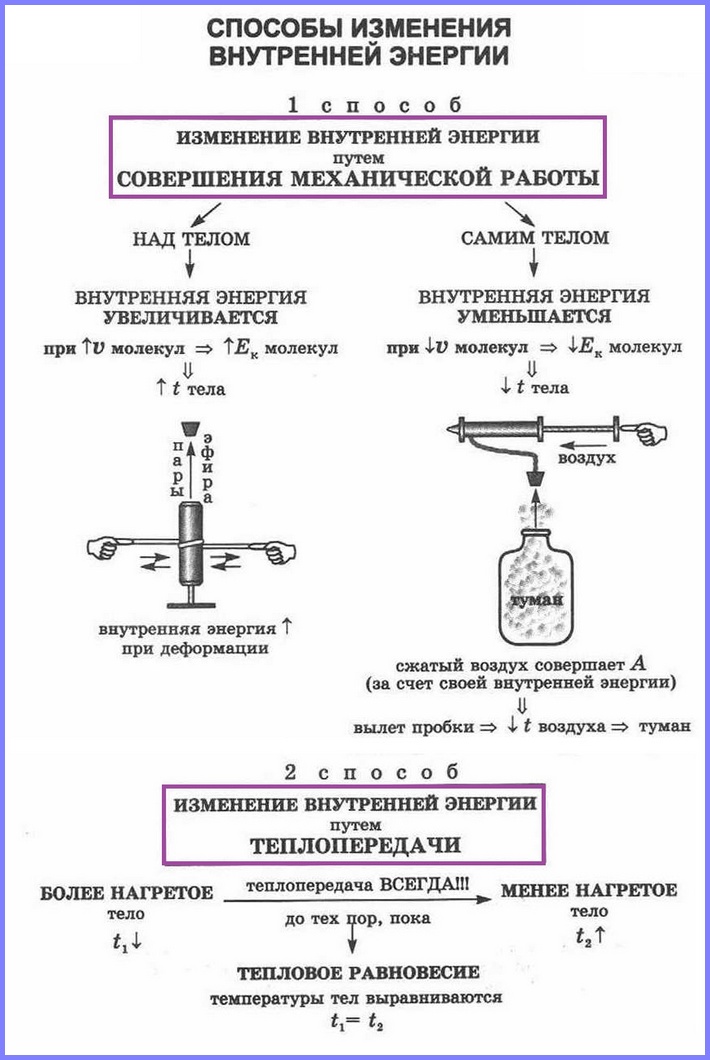

Способы изменения внутренней энергии

Чтобы изменить механическую энергию тела, надо изменить скорость его движения, взаимодействие с другими телами или взаимодействие частей тела. Вы уже знаете, что это достигается совершением работы.

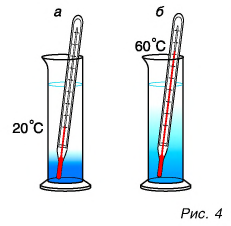

Как можно изменить (увеличить или уменьшить) внутреннюю энергию тела? Рассуждаем логически. Внутренняя энергия определяется как сумма кинетической и потенциальной энергий частиц. Значит, нужно изменить либо скорость движения частиц, либо их взаимодействие (изменить расстояния между ними). Очевидно, можно изменить и скорость, и расстояния между частицами одновременно. Изменить скорость частиц тела можно, увеличив или уменьшив его температуру. Действительно, наблюдения за диффузией показывают, что быстрота ее протекания увеличивается при нагревании (рис. 4, а, б).

Значит, увеличивается средняя скорость движения частиц, а следовательно, их средняя кинетическая энергия. Отсюда следует важный вывод: температура является мерой средней кинетической энергии частиц.

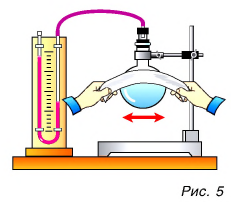

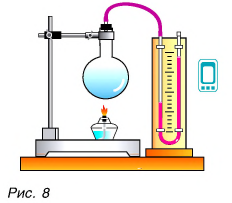

Как изменить кинетическую энергию частиц тела? Существуют два способа. Рассмотрим их на опытах. Будем натирать колбу с воздухом полоской сукна (рис. 5).

Через некоторое время уровень жидкости в правом колене манометра (см. рис. 5) опустится, т. е. давление воздуха в колбе увеличится. Это говорит о нагревании воздуха. Значит, увеличилась скорость движения и кинетическая энергия его молекул, а следовательно, и внутренняя энергия. Но за счет чего? Очевидно, за счет совершения механической работы при трении сукна о колбу. Нагрелась колба, а от нее — газ.

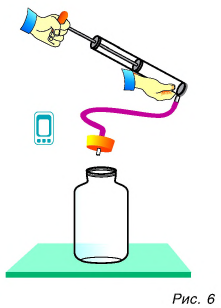

Проведем еще один опыт. В толстостенный стеклянный сосуд нальем немного воды (чайную ложку для увлажнения воздуха в нем. Насосом (рис. 6) будем накачивать в сосуд воздух. Через несколько качков пробка вылетит, а в сосуде образуется туман. Из наблюдений за окружающей средой мы знаем, что туман появляется тогда, когда после теплого дня наступает холодная ночь. Образование тумана в сосуде свидетельствует об охлаждении воздуха, т. е. об уменьшении его внутренней энергии. Но почему уменьшилась энергия? Потому что за ее счет совершена работа по выталкиванию пробки из сосуда.

Сравним результаты опытов. В обоих случаях изменилась внутренняя энергия газа, но в первом опыте она увеличилась, так как работа совершалась внешней силой (над колбой с газом), а во втором — уменьшилась, ибо работу совершала сила давления самого газа.

А можно ли, совершая работу, изменить потенциальную энергию взаимодействия молекул?

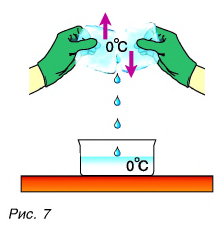

Опять обратимся к опыту. Два куска льда при О °C будем тереть друг о друга (рис. 7).

Лед превращается в воду, при этом температура воды и льда остается постоянной, равной О °C (см. рис. 7). На что тратится механическая работа силы трения?

Конечно же, на изменение внутренней энергии!

Но кинетическая энергия молекул не изменилась, так как температура не изменилась. Лед превратился в воду. При этом изменились силы взаимодействия молекул

Совершение механической работы — один из способов изменения внутренней энергии тела.

А есть ли возможность изменить внутреннюю энергию тела, не совершая механическую работу?

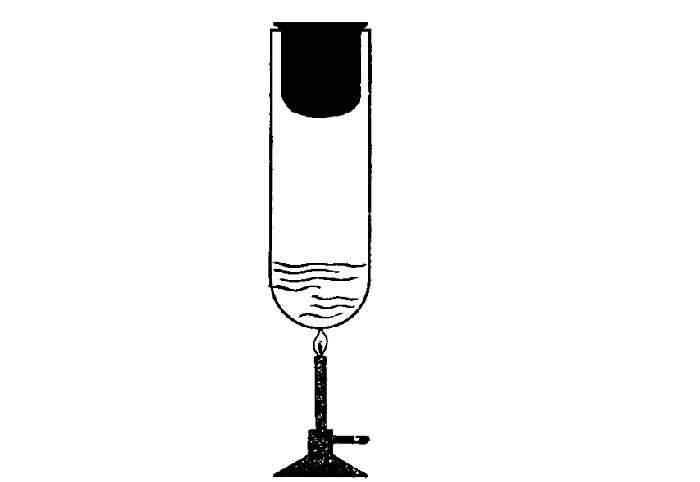

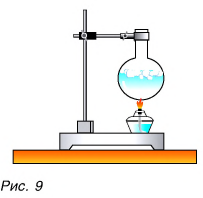

Да, есть. Нагреть воздух в колбе (рис. 8), расплавить лед (рис. 9) можно с помощью спиртовки, передав и воздуху, и льду теплоту. В обоих случаях внутренняя энергия увеличивается.

При охлаждении тел (если колбы со льдом и воздухом поместить в морозильник) их внутренняя энергия уменьшается. Теплота от тел передается окружающей среде.

Процесс изменения внутренней энергии тела, происходящий без совершения работы, называется теплопередачей (теплообменом).

Таким образом, совершение механической работы и теплопередача — два способа изменения внутренней энергии тела.

Величину, равную изменению внутренней энергии при теплопередаче, называют количеством теплоты (обозначается Q). Единицей количества теплоты, как работы и энергии, в СИ является 1 джоуль.

Для любознательных:

Физики XVIII в. и первой половины XIX в. рассматривали теплоту не как изменение энергии, а как особое вещество — теплород — жидкость (флюид), которая может перетекать от одного тела к другому. Если тело нагревалось, то считалось, что в него вливался теплород, а если охлаждалось — то выливался. При нагревании тела расширяются. Это объяснялось тем, что теплород имеет объем. Но если теплород — вещество, то тела при нагревании должны увеличивать свою массу. Однако взвешивания показывали, что масса тела не менялась. Поэтому теплород считали невесомым. Теорию теплорода поддерживали многие ученые, в том числе и такой гениальный ученый, как Г. Галилей. Позже Дж. Джоуль на основании проведенных им опытов пришел к выводу, что теплород не существует и что теплота есть мера изменения кинетической и потенциальной энергий движущихся частиц тела.

В дальнейшем выражение «сообщить телу количество теплоты» мы будем понимать как «изменить внутреннюю энергию тела без совершения механической работы, т. е. путем теплообмена». А выражение «нагреть тело» будем понимать как «повысить его температуру» любым из двух способов.

Главные выводы:

- Внутреннюю энергию тела можно изменить путем совершения механической работы или теплопередачи (теплообмена).

- Изменение внутренней энергии при нагревании или охлаждении тела при постоянном объеме связано с изменением средней кинетической энергии его частиц.

- Изменение внутренней энергии тела при неизменной температуре связано с изменением потенциальной энергии его частиц.

Основы термодинамики

МКТ стала общепризнанной на рубеже XIX и XX веков. Задолго до ее создания исследованием тепловых процессов занималась термодинамика — раздел физики, изучающий превращение внутренней (тепловой) энергии в другие виды энергии и наоборот, а также количественные соотношения при таких превращениях.

- Заказать решение задач по физике

Внутренняя энергия и ее особенности

Внутренняя энергия макроскопического тела определяется характером движения и взаимодействия всех микрочастиц, из которых состоит тело (система тел). Таким образом, к внутренней энергии следует отнести:

- кинетическую энергию хаотического (теплового) движения частиц вещества (атомов, молекул, ионов);

- потенциальную энергию взаимодействия частиц вещества;

- энергию взаимодействия атомов в молекулах (химическую энергию);

- энергию взаимодействия электронов и ядра в атоме и энергию взаимодействия нуклонов в ядре (внутриатомную и внутриядерную энергии).

Однако для описания тепловых процессов важно не столько значение внутренней энергии, как ее изменение. При тепловых процессах химическая, внутриатомная и внутриядерная энергии практически не изменяются. Именно поэтому внутренняя энергия в термодинамике определяется как сумма кинетических энергий хаотического (теплового) движения частиц вещества (атомов, молекул, ионов), из которых состоит тело, и потенциальных энергий их взаимодействия.

Внутреннюю энергию обозначают символом U.

Единица внутренней энергии в СИ — джоуль: [U]=1 Дж (J).

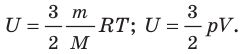

Особенности внутренней энергии идеального газа

- Атомы и молекулы идеального газа практически не взаимодействуют друг с другом, поэтому внутренняя энергия идеального газа равна кинетической энергии поступательного и вращательного движений его частиц.

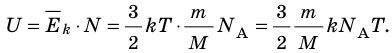

- Внутренняя энергия данной массы идеального газа прямо пропорциональна его абсолютной температуре. Докажем данное утверждение для одноатомного газа. Атомы такого газа движутся только поступательно, поэтому, чтобы определить его внутреннюю энергию, следует среднюю кинетическую энергию поступательного движения атомов умножить на количество атомов:

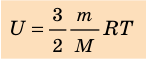

Итак, для одноатомного идеального газа:

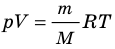

. Используя уравнение состояния

, выражение для внутренней энергии идеального одноатомного газа можно представить так:

- Внутренняя энергия — функция состояния системы, то есть она однозначно определяется основными макроскопическими параметрами (p, V, T), характеризующими систему. Независимо от того, каким образом система переведена из одного состояния в другое, изменение внутренней энергии будет одинаковым.

- Внутреннюю энергию можно изменить двумя способами: совершением работы и теплопередачей.

Какие существуют виды теплопередачи

Теплопередача (теплообмен) — процесс изменения внутренней энергии тела или частей тела без совершения работы. Процесс теплопередачи возможен только при наличии разности температур. Самопроизвольно тепло всегда передается от более нагретого тела к менее нагретому. Чем больше разность температур, тем быстрее — при прочих равных условиях — протекает процесс передачи тепла.

| Виды теплопередачи | ||

|---|---|---|

| Теплопроводность | Конвекция | Излучение |

|

Вид теплопередачи, который обусловлен хаотическим движением частиц вещества и не сопровождается переносом этого вещества. Лучшие проводники тепла — металлы, плохо проводят тепло дерево, стекло, кожа, жидкости (за исключением жидких металлов); самые плохие проводники тепла — газы. Передача энергии от горячей воды к батарее отопления, от поверхности воды до ее нижних слоев и т. д. происходит благодаря теплопроводности. |

Вид теплопередачи, при котором тепло переносится потоками жидкости или газа. Теплые потоки жидкости или газа имеют меньшую плотность, поэтому под действием архимедовой силы поднимаются, а холодные потоки — опускаются. Благодаря конвекции происходит циркуляция воздуха в помещении, нагревается жидкость в стоящей на плите кастрюле, существуют ветры и морские течения и т. д. В твердых телах конвекция невозможна. | Вид теплопередачи, при котором энергия передается посредством электромагнитных волн. Излучение — универсальный вид теплопередачи: тела всегда излучают и поглощают инфракрасное (тепловое) излучение. Это единственный вид теплообмена, возможный в вакууме (энергия от Солнца передается только излучением). Лучше излучают и поглощают энергию тела с темной поверхностью. |

Как определить количество теплоты

Количество теплоты Q — это физическая величина, равная энергии, которую тело получает (или отдает) в ходе теплопередачи.

Единица количества теплоты в СИ — джоуль: [П] =1 Дж (J).

Из курса физики 8 класса вы знаете, что количество теплоты, которое поглощается при нагревании вещества (или выделяется при его охлаждении), вычисляют по формуле: Q=cm∆Т=cm∆t , где c — удельная теплоемкость вещества; m — масса вещества;

Обратите внимание! Произведение удельной теплоемкости на массу вещества, из которого изготовлено тело, называют теплоемкостью тела: C=cm . Если известна теплоемкость C тела, то количество теплоты, которое получает тело при изменении температуры на ∆T, вычисляют по формуле: Q=C∆T .

| Расчет количества теплоты при фазовых переходах | |

|---|---|

| Кристаллическое состояние ↔ Жидкое состояние | Жидкое состояние ↔ Газообразное состояние |

|

Температуру, при которой происходят фазовые переходы «кристалл → жидкость» и «жидкость → кристалл», называют температурой плавления. Температура плавления зависит от рода вещества и внешнего давления. Количество теплоты Q, которое поглощается при плавлении кристаллического вещества (или выделяется при кристаллизации жидкости), вычисляют по формуле: Q = λm, где m — масса вещества; λ — удельная теплота плавления. |

Фазовые переходы «жидкость → пар» и «пар → жидкость» происходят при любой температуре. Количество теплоты Q, которая поглощается при парообразовании (или выделяется при конденсации), вычисляют по формуле: Q=rm (Q=Lm), где m — масса вещества; r (L) — удельная теплота парообразования при данной температуре (обычно в таблицах представлена удельная теплота парообразования при температуре кипения жидкости). |

| Напомним: и при плавлении, и при кипении температура вещества не изменяется. |

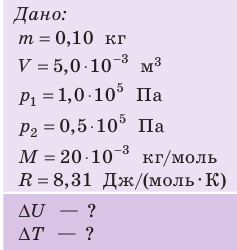

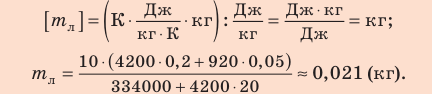

Пример решения задачи №1

Неон массой 100 г находится в колбе объемом 5,0 л. В процессе изохорного охлаждения давление неона уменьшилось с 100 до 50 кПа. На сколько при этом изменились внутренняя энергия и температура неона?

Решение:

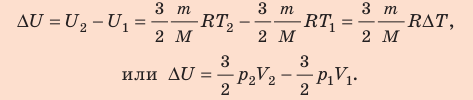

Неон — одноатомный газ; для таких газов изменение внутренней энергии равно:

Поскольку охлаждение изохорное, объем неона не изменяется:

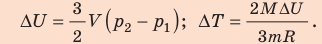

Проверим единицы, найдем значения искомых величин:

Анализ результатов. Знак «–» свидетельствует о том, что внутренняя энергия и температура неона уменьшились, — это соответствует изохорному охлаждению. Ответ: ∆U = –375 Дж; ∆T = –6 К.

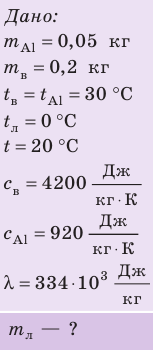

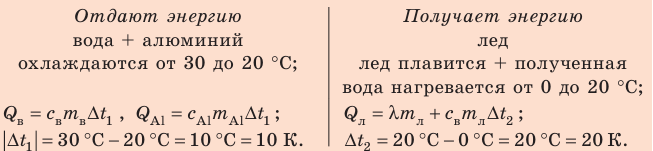

Пример решения задачи №2

Внутренний алюминиевый сосуд калориметра имеет массу 50 г и содержит 200 г воды при температуре 30 °С. В сосуд бросили кубики льда при температуре 0 °С, в результате чего температура воды в калориметре снизилась до 20 °С. Определите массу льда. Удельные теплоемкости воды и алюминия:

Анализ физической проблемы.

Калориметр имеет такое устройство, что теплообмен с окружающей средой практически отсутствует, поэтому для решения задачи воспользуемся уравнением теплового баланса. В теплообмене участвуют три тела: вода, внутренний сосуд калориметра, лед.

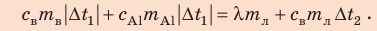

Решение:

Запишем уравнение теплового баланса:

После преобразований получим:

Проверим единицу, найдем значение искомой величины:

Ответ:

Выводы:

- В термодинамике под внутренней энергией U тела понимают сумму кинетических энергий хаотического движения частиц вещества, из которых состоит тело, и потенциальных энергий их взаимодействия. Внутренняя энергия однозначно определяется основными макроскопическими параметрами (p, V, T), характеризующими термодинамическую систему. Внутреннюю энергию идеального одноатомного газа определяют по формулам:

- Внутреннюю энергию можно изменить двумя способами: совершением работы и теплопередачей. Существует три вида теплопередачи: теплопроводность, конвекция, излучение.

- Физическую величину, равную энергии, которую тело получает или отдает при теплопередаче, называют количеством теплоты (Q): Q=cm∆T = С∆T — количество теплоты, которое поглощается при нагревании тела (или выделяется при его охлаждении); Q = λm — количество теплоты, которое поглощается при плавлении вещества (или выделяется при кристаллизации); Q=rm (Q=Lm) — количество теплоты, которое поглощается при парообразовании вещества (или выделяется при конденсации).

- Теплопроводность в физике

- Конвекция в физике

- Излучение тепла в физике

- Виды излучений в физике

- Машины и механизмы в физике

- Коэффициент полезного действия (КПД) механизмов

- Тепловые явления в физике

- Тепловое движение в физике и его измерение

Термодинамика — раздел физики, изучающий превращения энергии в макроскопических системах и основные свойства этих систем.

Термодинамика опирается на общие закономерности тепловых процессов и свойств макроскопических систем. Выводы термодинамики эмпирические, то есть опираются на факты, проверенные опытным путем с использованием молекулярно-кинетической модели.

Для описания термодинамических процессов в системах, состоящих из большого числа частиц, используются величины, не применимые к отдельным молекулам и атомам: температура, давление, концентрация, объем, энтропия)

Термодинамическое равновесие — состояние макросопической системы, когда описывающие ее макроскопические величины остаются неизменными.

В термодинамике рассматриваются изолированные системы тел, находящиеся в термодинамическом равновесии. То есть в системах с прекращением всех наблюдаемых макроскопических процессов. Особую важность представляет свойство, которое получило название выравнивания температуры всех ее частей.

При внешнем воздействии на термодинамическую систему наблюдается переход в другое равновесное состояние. Он получил название термодинамического процесса. Когда время его протекания достаточно медленное, система приближена к состоянию равновесия. Процессы, состоящие из последовательности равновесных состояний, называют квазистатическими.

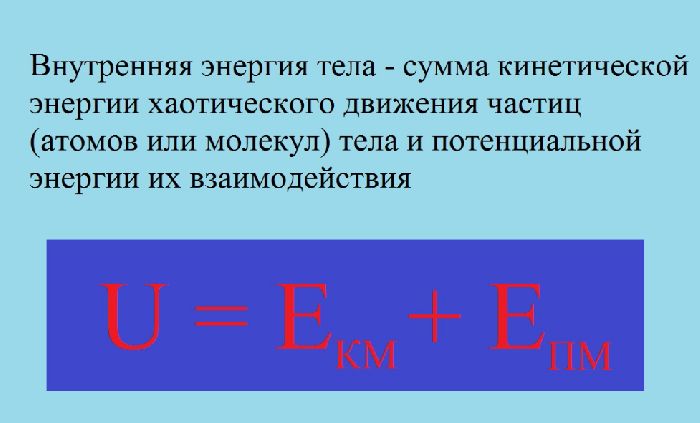

Внутренняя энергия. Формулы

Внутренняя энергия считается важнейшим понятием термодинамики. Макроскопические тела (системы) имеют внутреннюю энергию, состящую из энергии каждой молекулы. Исходя из молекулярно-кинетической теории, внутренняя энергия состоит из кинетической энергии атомов и молекул, а также потенциальной энергии их взаимодействия.

Например, внутренняя энергия идеального газа равняется сумме кинетических энергий частиц газа, которые находятся в непрерывном беспорядочном тепловом движении. После подтверждений большим количеством экспериментов, был получен закон Джоуля:

Внутренняя энергия идеального газа зависит только от его температуры и не зависит от объема.

Применение молекулярно-кинетической теории говорит о том, что выражение для определения внутренней энергии 1 моля одноатомного газа, с поступательными движениями молекул записывается как:

U=32NАkT=32RT.

Зависимость от расстояния между молекулами у потенциальной энергии очевидна, поэтому внутренняя U и температура Т обусловлены изменениями V:

U=U(T, V).

Определение внутренней энергии U производится с помощью наличия макроскопических параметров, характеризующих состояние тела. Изменение внутренней энергии происходит по причине действия на тело внешних сил, совершающих работу. Внутренняя энергия является функцией состояния системы.

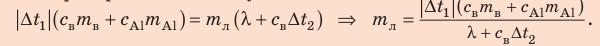

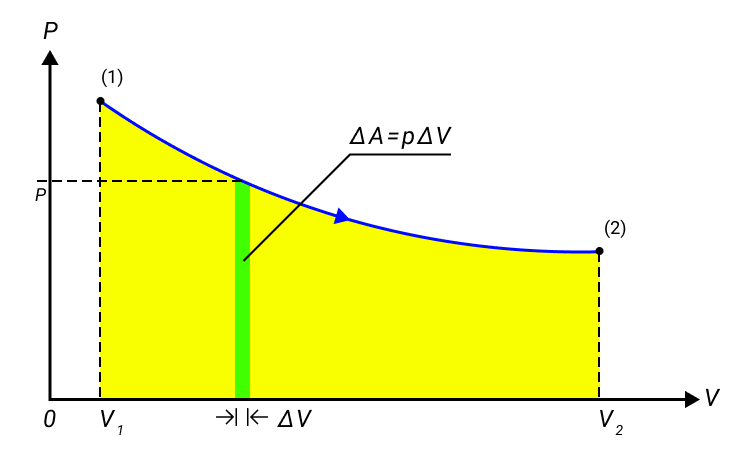

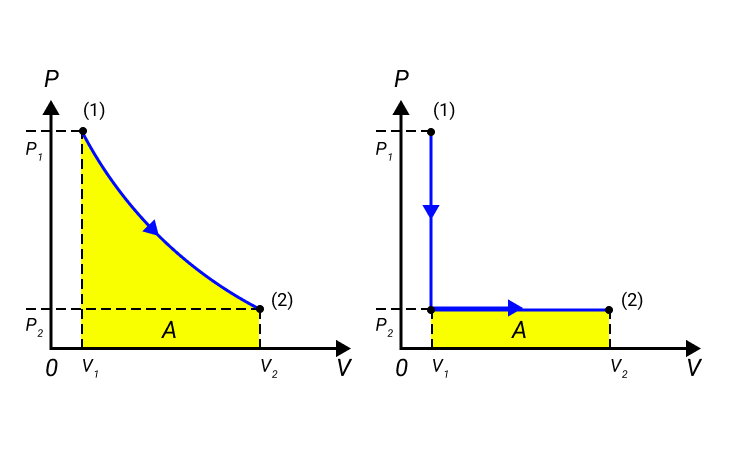

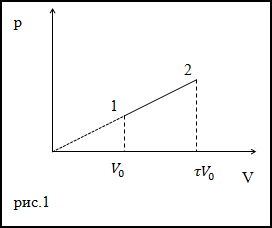

Когда газ в цилиндре сжимается под поршнем, то внешние силы совершают положительную работу A’. Силы давления газа на поршень также совершают работу, но равную A=-A’. При изменении объема газа на величину ∆V, говорят, что он совершает работу pS∆x=p∆V, где p – давление газа, S – площадь поршня, ∆x – его перемещение. Подробно показано в примере на рисунке 1.

Наличие знака перед работой говорит о работе газа в разных состояниях: положительная при расширении и отрицательная при сжатии. Переход из начального в конечное состояние работы газа может быть описан с помощью формулы:

A=∑pidVi или в пределе при ∆Vi→0:

A=∫V1V2pdV.

Рисунок 1. Работа газа при расширении.

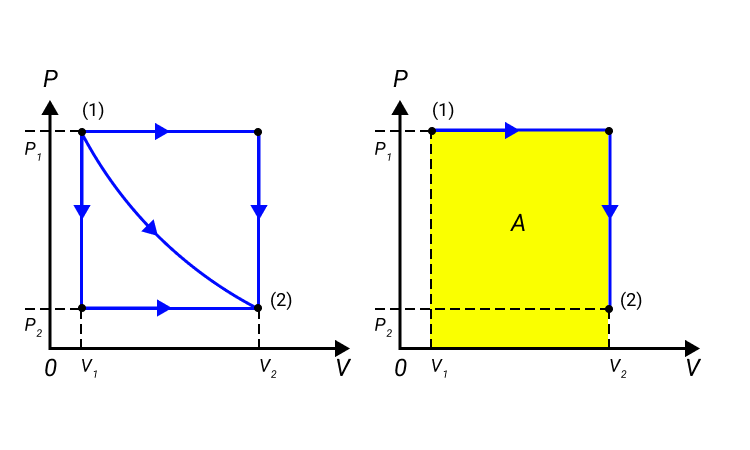

Обратимые и необратимые процессы

Работа численно равняется площади процесса, изображенного на диаграмме p, V. Величина А зависит от метода перехода от начального состояния в конечное. Рисунок 2 показывает 3 процесса, которые переводят газ из состояние (1) в состояние (2). Во всех случаях газ совершает работу.

Рисунок 2. Три различных пути перехода из состояния (1) в состояние (2). Во всех трех случаях газ совершает разную работу, равную площади под графиком процесса.

Процессы из рисунка 2 возможно провести в обратном направлении. Тогда произойдет изменение знака А на противоположный.

Процессы, которые возможно проводить в обоих направлениях, получили название обратимых.

Жидкости и твердые тела могут незначительно изменять свой объем, поэтому при совершении работы разрешено им пренебречь. Но их внутренняя энергия подвергается изменениям посредствам совершения работы.

Механическая обработка деталей нагревает их. Это способствует изменению внутренней энергии. Имеется еще один пример опыта Джоуля 1843 года, служащий для определения механического эквивалента теплоты, изображенного на рисунке 3. Во время вращения катушки, находящейся в воде, внешние силы совершают положительную работу A’>0, тогда жидкость повышает температуру из-за наличия силы трения, то есть происходит увеличение внутренней энергии.

Процессы примеров не могут проводиться в противоположных направлениях, поэтому они получили название необратимых.

Рисунок 3. Упрощенная схема опыта Джоуля по определению механического эквивалента теплоты.

Изменение внутренней энергии возможно при наличии совершаемой работы и при теплообмене. Тепловой контакт тел позволяет увеличиваться энергии одного тела с уменьшением энергии другого. Иначе это называется тепловым потоком.

Количество теплоты

Количество теплоты Q, полученное телом, называется его внутренней энергией, получаемой в результате теплообмена.

Рисунок 4. Модель работы газа.

Процесс передачи тепла тел возможен только при разности их температур.

Направление теплового потока всегда идет к холодному телу.

Количество теплоты Q считается энергетической величиной и измеряется в джоулях (Дж).

«Внутренняя энергия»

Существуют два вида механической энергии: кинетическая и потенциальная. Сумма кинетической и потенциальной энергии тела называется его полной механической энергией, которая зависит от скорости движения тела и от его положения относительно того тела, с которым оно взаимодействует. Если тело обладает энергией, то оно может совершить работу. При совершении работы энергия тела изменяется. Значение работы равно изменению энергии. (подробнее о Механической энергии в конспекте «Механическая энергия. Закон сохранения энергии»)

Внутренняя энергия

Если в закрытую пробкой толстостенную банку, дно которой покрыто водой, накачивать, то через какое-то время пробка из банки вылетит и в банке образуется туман. Пробка вылетела из банки, потому что находившийся там воздух действовал на неё с определённой силой. Воздух при вылете пробки совершил работу. Известно, что работу тело может совершить, если оно обладает энергией. Следовательно, воздух в банке обладает энергией.

При совершении воздухом работы понизилась его температура, изменилось его состояние. При этом механическая энергия воздуха не изменилась: не изменились ни его скорость, ни его положение относительно Земли. Следовательно, работа была совершена не за счёт механической, а за счёт другой энергии. Эта энергия — внутренняя энергия воздуха, находящегося в банке.

Внутренняя энергия тела – это сумма кинетической энергии движения его молекул и потенциальной энергии их взаимодействия. Кинетической энергией (Ек) молекулы обладают, так как они находятся в движении, а потенциальной энергией (Еп), поскольку они взаимодействуют. Внутреннюю энергию обозначают буквой U. Единицей внутренней энергии является 1 джоуль (1 Дж). U = Eк + En.

Способы изменения внутренней энергии

Чем больше скорости движения молекул, тем выше температура тела, следовательно, внутренняя энергия зависит от температуры тела. Чтобы перевести вещество из твёрдого состояния в жидкое состояние, например, превратить лёд в воду, нужно подвести к нему энергию. Следовательно, вода будет обладать большей внутренней энергией, чем лёд той же массы, и, следовательно, внутренняя энергия зависит от агрегатного состояния тела.

Внутреннюю энергию можно изменить при совершении работы. Если по куску свинца несколько раз ударить молотком, то даже на ощупь можно определить, что кусок свинца нагреется. Следовательно, его внутренняя энергия, так же как и внутренняя энергия молотка, увеличилась. Это произошло потому, что была совершена работа над куском свинца.

Если тело само совершает работу, то его внутренняя энергия уменьшается, а если над ним совершают работу, то его внутренняя энергия увеличивается.

Если в стакан с холодной водой налить горячую воду, то температура горячей воды понизится, а холодной воды — повысится. В рассмотренном примере механическая работа не совершается, внутренняя энергия тел изменяется путём теплопередачи, о чем и свидетельствует понижение её температуры.

Молекулы горячей воды обладают большей кинетической энергией, чем молекулы холодной воды. Эту энергию молекулы горячей воды передают молекулам холодной воды при столкновениях, и кинетическая энергия молекул холодной воды увеличивается. Кинетическая энергия молекул горячей воды при этом уменьшается.

Теплопередача – это способ изменения внутренней энергии тела при передаче энергии от одной части тела к другой или от одного тела к другому без совершения работы.

Конспект урока по физике в 8 классе «Внутренняя энергия».

Следующая тема: «Виды теплопередачи: теплопроводность, конвекция, излучение».

Внутренняя энергия

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 267.

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 267.

Энергия как физическая величина характеризует способность физических объектов совершать работу. Механическая энергия является суммой потенциальной и кинетической энергий, которые зависят от взаимного расположения тел и скорости их движения. С помощью характеристики внутренней энергии в физике объясняются процессы, когда работа может совершаться покоящимся телом за счет энергии отдельных частиц, из которых состоит это тело.

Примеры внутренней энергии

Если в лабораторную колбу налить немного воды, закрыть ее пробкой и поставить нагреваться на плитке, то через некоторое время пробка выскочит под давлением пара, который образуется в результате кипения воды. То есть будет произведена работа по выталкиванию (перемещению) пробки, хотя весь объем пара (как целое) находился в состоянии покоя. Электрическая энергия перешла в тепло, которое довело воду до точки кипения, и образовавшийся пар (газообразное состояние воды) вытолкнул пробку. На совершение работа была затрачена внутренняя энергия пара.

.

Откуда берется эта энергия?

Все физические объекты (твердые, жидкие и газообразные) состоят из атомов и молекул, которые находятся в постоянном движении. В газах атомы и молекулы перемещаются внутри всего объема хаотично. В жидкостях длина пробега намного меньше, а в твердом теле молекулы колеблются в узлах кристаллической решетки. При повышении температуры возрастают скорость перемещения частиц, то есть увеличивается их кинетическая энергия, которая равняется:

$$Ek={mv^2 over 2}$$

где:

Ek — кинетическая энергия;

m — масса;

v — скорость.

Все частицы взаимодействуют друг с другом (притягиваются, отталкиваются), а значит обладают еще и потенциальной энергией Eп. Сумма этих двух энергий является внутренней энергией системы, которую обозначают U:

$$U=Ek + Eп $$

Скорости молекул в газах сильно зависят от массы молекул и температуры. Например, при комнатной температуре средняя скорость молекул в водороде составляет 1930 м/сек, а в кислороде — 480 м/сек.

Как измерить внутреннюю энергию?

Внутренняя энергия тела может изменяться под воздействием внешней средой либо получая или отдавая тепло Q, либо совершая работу А. Экспериментально можно измерить только изменение внутренней энергии U. Первый закон термодинамики устанавливает формулу нахождения U:

$∆U ={ Q – A }$

Величину совершенной работы и полученное (или отданное) тепло можно измерить, а значит можно определить изменение внутренней энергии.

Молекулярная внутренняя энергия идеального газа

Идеальным газом называют такую среду, в которой расстояния между молекулами настолько велики, что друг с другом они не взаимодействуют, а значит внутренняя энергия газа представляет собой только сумму кинетических энергий всех молекул. Для такой модели удается получить формулу для вычисления внутренней энергии U:

$$U={3mRTover 2}$$

где:

m — масса газа, кг;

M — молярная масса газа, кг/моль;

T — температура газа;

R — универсальная газовая постоянная, R = 8,3144598 Дж/(моль*К).

Из этой формулы следует, что внутренняя энергия идеального газа U зависит только от температуры.

Реальные физические объекты (газов, жидкостей, твердых тел) такая модель не описывает, так как необходимо учитывать энергию взаимодействия между частицами. Значит появится зависимость от объема тела.

Что мы узнали?

Итак, мы узнали, что внутренняя энергия тела — это сумма кинетической и потенциальной энергий всех частиц тела. В идеальном газе внутренняя энергия зависит только от температуры. Изменить внутреннюю энергию можно только либо с помощью совершения работы, либо подведения (или отбора) тепла к телу.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Айана Капсаргина

9/10

-

Мария Кшевач

8/10

Оценка доклада

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 267.

А какая ваша оценка?

Содержание:

- Определение и формула внутренней энергии

- Внутренняя энергия идеального газа

- Первое начало термодинамики

- Единицы измерения внутренней энергии

- Примеры решения задач

Определение и формула внутренней энергии

Определение

Внутренней энергией тела (системы) называют энергию, которая связана со всеми видами движения и взаимодействия частиц,

составляющих тело (систему), включая энергию взаимодействия и движения сложных частиц.

Из выше сказанного следует, что к внутренней энергии не относят кинетическую энергию движения центра масс системы и потенциальную энергию системы, вызванную действием внешних сил. Это энергия, которая зависит только от термодинамического состояния системы.

Внутреннюю энергию чаще всего обозначают буквой U. При этом бесконечно малое ее изменение станет обозначаться dU. Считается, что dU является положительной величиной, если внутренняя энергия системы растет, соответственно, внутренняя энергия отрицательна, если внутренняя энергия уменьшается.

Внутренняя энергия системы тел равна сумме внутренних энергий каждого отдельного тела плюс энергия взаимодействия между телами внутри системы.

Внутренняя энергия – функция состояния системы. Это означает, что изменение внутренней энергии системы при переходе системы из одного состояния в другое не зависит от способа перехода (вида термодинамического процесса при переходе) системы и равно разности внутренних энергий конечного и начального состояний:

$$Delta U=U_{2}-U_{1}(1)$$

Для кругового процесса полное изменение внутренней энергии системы равно нулю:

$$oint d U=0(2)$$

Для системы, на которую не действуют внешние силы и находящуюся в состоянии макроскопического покоя, внутренняя энергия – полная энергия системы.

Внутренняя энергия может быть определена только с точностью до некоторого постоянного слагаемого (U0), которое не определимо

методами термодинамики. Однако, данный факт не существенен, так как при использовании термодинамического анализа, имеют дело с изменениями

внутренней энергии, а не абсолютными ее величинами. Часто U_0 полагают равным нулю. При этом в качестве внутренней энергии рассматривают ее

составляющие, которые изменяются в предлагаемых обстоятельствах.

Внутреннюю энергию считают ограниченной и ее граница (нижняя) соответствует T=0K.

Внутренняя энергия идеального газа

Внутренняя энергия идеального газа зависит только от его абсолютной температуры (T) и пропорциональна массе:

$$U=int_{0}^{T} C_{V} d T+U_{0}=mleft(int_{0}^{T} c_{V} d T+u_{0}right)$$

где CV – теплоемкость газа в изохорном процессе; cV — удельная теплоемкость газа в изохорном процессе;

$u_{0}=frac{U_{0}}{m}$ – внутренняя энергия, приходящаяся на единицу массы газа

при абсолютном нуле температур. Или:

$$d U=frac{i}{2} nu R d T(4)$$

i – число степеней свободы молекулы идеального газа, v – число молей газа, R=8,31 Дж/(моль•К) – универсальная газовая постоянная.

Первое начало термодинамики

Как известно первое начало термодинамики имеет несколько формулировок. Одна из формулировок, которую предложил К.

Каратеодори говорит о существовании внутренней энергии как составляющей полной энергии системы.Она является функцией состояния,

в простых системах зависящей от объема (V), давления (p), масс веществ (mi), которые составляют данную систему:

$U=Uleft(p, V, sum m_{i}right)$ . В формулировке, которую дал Каратеодори внутренняя

энергия не является характеристической функцией своих независимых переменных.

В более привычных формулировках первого начала термодинамики, например, формулировке Гельмгольца внутренняя энергия системы вводится как физическая характеристика системы. При этом поведение системы определено законом сохранения энергии. Гельмгольц не определяет внутреннюю энергию как функцию конкретных параметров состояния системы:

$$Delta U=Q-A(5)$$

$Delta U$ – изменение внутренней энергии в равновесном процессе,

Q – количество теплоты, которое получила система в рассматриваемом процессе, A – работа, которую система совершила.

Единицы измерения внутренней энергии

Основной единицей измерения внутренней энергии в системе СИ является: [U]=Дж

Примеры решения задач

Пример

Задание. Вычислите, на какую величину изменится внутренняя энергия гелия имеющего массу 0,1 кг, если его температура увеличилась на 20С.

Решение. При решении задачи считаем гелий одноатомным идеальным газом, тогда для расчетов можно применить формулу:

$$d U=frac{i}{2} nu R d T(1.1)$$

Так как мы имеем с одноатомным газом, то $i=3 ; nu=frac{m}{mu}$, молярную массу

($mu$) возьмем из таблицы Менделеева

($mu_{H e}=4 cdot 10^{-3}$ кг/моль). Масса газа в представленном процессе

не изменяется, следовательно, изменение внутренней энергии равно:

$$Delta U=int_{T_{1}}^{T_{2}} d U=frac{i}{2} frac{m}{mu} R int_{T_{1}}^{T_{2}} d T=frac{i}{2} frac{m}{mu} Rleft(T_{2}-T_{1}right)$$

где $T_{2}-T_{1}=Delta T=Delta t$

Все величины необходимые для вычислений имеются:

$Delta U=frac{3}{2} cdot frac{0,1}{4 cdot 10^{-3}} cdot 20 cdot 8,31=6,2 cdot 10^{3}$ (Дж)

Ответ. $Delta U=6,2 cdot 10^{3}$ (Дж)

236

проверенных автора готовы помочь в написании работы любой сложности

Мы помогли уже 4 396 ученикам и студентам сдать работы от решения задач до дипломных на отлично! Узнай стоимость своей работы за 15 минут!

Пример

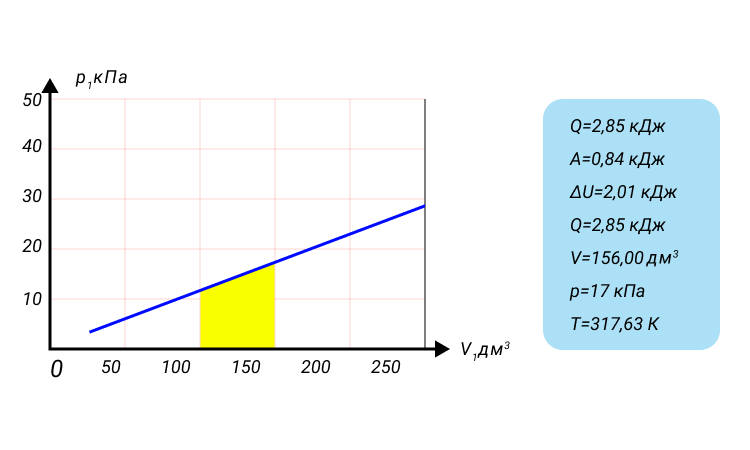

Задание. Идеальный газ расширили в соответствии с законом, который изображен графиком на рис.1. от начального объема

V0. При расширении объем сал равен $V=tau V_{0}$ .

Каково приращение внутренней энергии газа в заданном процессе? Коэффициент адиабаты равен $gamma$.

Решение. Исходя из рисунка, уравнение процесса можно представить аналитически как:

$$p=alpha V(2.1)$$

Показатель адиабаты связан с числом степеней свободы газа выражением:

$$gamma=frac{i+2}{i}(2.2)$$

Выразим число степеней свободы из (2.2):

$$i=frac{2}{gamma-1}$$

Приращение внутренней энергии для постоянной массы газа (см. Пример 1) найдем в соответствии с формулой:

$$Delta U=frac{i}{2} nu R Delta T(2.4)$$

Запишем уравнения состояний идеального газа для точек (1) и (2) рис.1:

$$

begin{aligned}

p V &=nu R T(2.5) \

p_{0} V_{0} &=nu R T_{0}

end{aligned}

$$

Тогда приращение температуры, учитывая уравнение процесса и выражения (2.5), (2.6) найдем как:

$$

begin{aligned}

Delta T &=T-T_{0}=frac{1}{nu R}left(p V-p_{0} V_{0}right)=frac{1}{nu R}left(alpha V cdot V-alpha V_{0} V_{0}right)=\

&=frac{1}{nu R}left(alpha tau V_{0} cdot tau V_{0}-alpha V_{0} V_{0}right)=frac{1}{nu R} V_{0}^{2} alphaleft(tau^{2}-1right)(2.7)

end{aligned}

$$

Подставим $Delta T$ в выражение для

$Delta U$ (2.4), получим:

$Delta U=frac{i}{2} v R frac{1}{v R} V_{0}^{2} alphaleft(tau^{2}-1right)=frac{1}{gamma-1} V_{0}^{2} alphaleft(tau^{2}-1right)$

Ответ. $Delta U=frac{1}{gamma-1} V_{0}^{2} alphaleft(tau^{2}-1right)$

Читать дальше: Формула времени.

![{displaystyle mathrm {d} U=C_{V},mathrm {d} T+left[Tleft({frac {partial P}{partial T}}right)_{V}-Pright]mathrm {d} V.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8ed701e880407b580dd14a57cd80113a92b019e1)

Итак, для одноатомного идеального газа:

Итак, для одноатомного идеального газа:  . Используя уравнение состояния

. Используя уравнение состояния  , выражение для внутренней энергии идеального одноатомного газа можно представить так:

, выражение для внутренней энергии идеального одноатомного газа можно представить так: