BMW (Bayerische Motoren Werke — «Баварские моторные заводы») — немецкая компания, занимающаяся изготовлением высокотехнологичных автомобилей и мотоциклов. Данный производитель входит в число фирм с самыми высокими продажами товаров.

Создайте свой логотип онлайн за 5 минут в Turbologo. Поместите свой логотип на визитки, бланки, другую сопутствующую графику и скачайте в один клик.

Создать логотип бесплатно

Девизом бренда является фраза «С удовольствием за рулём».

Происхождение марки БМВ

В 1916 году фирму основал Карл Фридрих Рапп. Он предложил руководителю схожего небольшого предприятия объединиться – решение принималось с целью увеличить экономическую выгоду. В середине 1917 года производство было зарегистрировано. Теперь оно выпускало авиационные двигатели и находилось вблизи крупного завода по созданию самолётов.

Спустя некоторое время сборка авиации на территории государства становится запрещена, поэтому BMW вынуждены начать реализацию сельскохозяйственной техники и тормозов для поездов. В 1922 году компания разрабатывает свой первый мотоцикл. В 1928 году фирма производит небольшие автомобили Dixi.

Во время Второй мировой войны бренд переключается на производство авиационных моторов. Но после окончания военных действий в стране компания оказывается в плачевном положении: разрушается часть предприятий, а остальные попадают в зону оккупации СССР. Однако фирма не прекращает свое существование и выпускает автомобили из оставшихся ресурсов.

К 1959 году компания вновь оказывается на грани разорения. Спрос на продукцию снижается из-за бедности населения. Представители бренда решают продать компанию на аукционе, но выпуск новых партий авто помогает фирме встать на ноги. На территории России продукция начинает реализовываться только в 1993 году. Это помогает бренду БМВ усилить свое влияние на рынке и повысить продажи.

Первый логотип БМВ

Первый логотип БМВ появился в 1917 году: две пересекающиеся перпендикулярные линии символизируют пропеллер (отсылка к изначальному роду деятельности бренда).

Центральный круглый сектор БМВ лого разделён двумя равными перпендикулярными линиями на четыре одинаковых сегмента. А эти четверти в свою очередь в шахматном порядке окрашены в насыщенный синий и белый оттенки. Элемент обведён широким чёрным кругом, а вверху расположена жёлтая надпись BMW.

Но что же означает логотип БМВ? Касательно цветового решения, есть несколько вариантов трактовки:

- белые и голубые сектора БМВ лого обозначают небо;

- оттенки транслируют флаг Баварии. Этой точки зрения придерживаются сами «Баварские моторные заводы».

История изменения логотипа БМВ

За свою почти столетнюю историю логотип BMW не претерпел кардинальных изменений. Однако небольшие ребрендинги все же были.

1923

1923 год: линии на логотипе, которыми обведены окружности, приобретают светло-коричневый цвет. Буквы надписи печатаются полужирным шрифтом. Центральная часть эмблемы остается неизменной.

1936

1936 год: логотип БМВ изменяет цветовое решение – буквы и окантовки становятся белыми. Части сектора круга становятся голубыми на смену синим. Шрифт надписи сохраняется.

1954

1954 год: символы логотипа избавляются от засечек и становятся рубленными. Также иной вид приобретает обводка эмблемы: она становится значительно ярче. Данный лого внешне максимально схож с тем, который используется компанией сейчас.

1970

1970 год: дизайн эмблемы теперь кардинально отличается от своих предшественников. Он разрабатывается в первую очередь для размещения на мототехнике. В расцветку логотипа добавляется розовый цвет. Кроме этого, на знаке появляются элементы не только голубого, но и темно-синего оттенков. Значительно изменяется и форма иконки: центральная часть помещается в середину лого, а вокруг располагаются три полуокружности разных цветов.

2000

2000 год: эмблема приобретает фактуру, используемую брендом в настоящий момент. В отличие от предыдущих вариантов дизайна, в лого добавляется объем. В остальном фирменный знак практически ничем не отличается от первых логотипов БМВ.

Заключение

Логотип BMW – один из самых узнаваемых в мире. Благодаря своей лаконичности и незамысловатости он не только легко запоминается, но и рассказывает историю компании.

Часто задаваемые вопросы

Что означает логотип БМВ?

Бело-синие сектора в лого BMW окрашены в цвета флага Баварии. А черное кольцо по краям эмблемы отражает принадлежность к Рапп Motorenwerke (так назывался бренд до переименования в БМВ).

На лого БМВ изображен пропеллер?

Данное мнение было опровергнуто представителями компании. Бренд и правда занимался производством авиационных двигателей, но на логотипе не изображен пропеллер.

Когда появился первый логотип БМВ?

Первая версия фирменного знака BMW была разработана в 1917 году.

Какой шрифт используется в логотипе БМВ?

На фирменном знаке бренда BMW надпись выполнена шрифтом BMW Helvetica bold.

Продуктовый и графический дизайнер с опытом работы более 10 лет. Пишу о брендинге, дизайне логотипов и бизнесе.

This article is about the German motor vehicle manufacturer. For other uses, see BMW (disambiguation).

Trading logo since 2020 |

|

BMW Headquarters in Munich, Germany |

|

| Type | Public (Aktiengesellschaft) |

|---|---|

|

Traded as |

FWB: BMW DAX Component |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Predecessors | Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik Rapp Motorenwerke Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach |

| Founded | 7 March 1916; 106 years ago (as Bayerische Flugzeugwerke) |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters |

Munich , Germany |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

Oliver Zipse, Chairman of the Board of Management Norbert Reithofer, Chairman of the Supervisory Board |

| Products |

|

|

Production output |

|

| Brands |

|

| Services | Financial services |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owners | Public float (50%); Stefan Quandt (29%), Susanne Klatten (21%) |

|

Number of employees |

118,909 (2021)[1] |

| Website | bmw.com bmwgroup.com |

Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, abbreviated as BMW (German pronunciation: [ˌbeːʔɛmˈveː] (listen)), is a German multinational manufacturer of luxury vehicles and motorcycles headquartered in Munich, Bavaria. The corporation was founded in 1916 as a manufacturer of aircraft engines, which it produced from 1917 until 1918 and again from 1933 to 1945.

Automobiles are marketed under the brands BMW, Mini and Rolls-Royce, and motorcycles are marketed under the brand BMW Motorrad. In 2017, BMW was the world’s fourteenth-largest producer of motor vehicles, with 2,279,503 vehicles produced.[2] The company has significant motor-sport history, especially in touring cars, sports cars, and the Isle of Man TT.

BMW is headquartered in Munich and produces motor vehicles in Germany, Brazil, China, India, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Quandt family is a long-term shareholder of the company (with the remaining shares owned by public float), following investments by the brothers Herbert and Harald Quandt in 1959 which saved the company from bankruptcy.

History

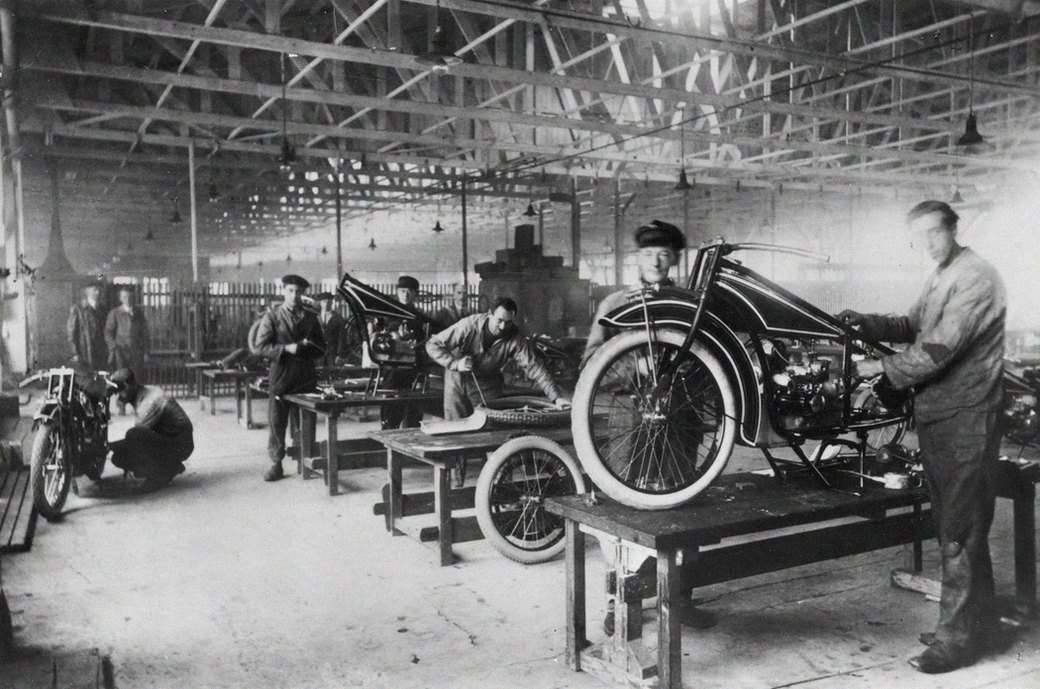

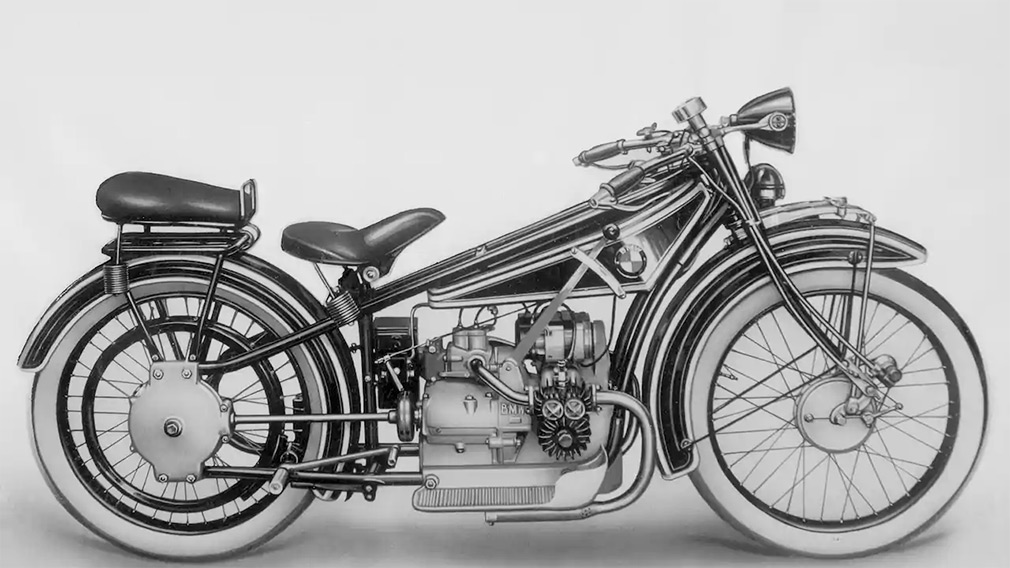

Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik was founded in 1910 by Gustav Otto in Bavaria. The firm was reorganized on 7 March 1916 into Bayerische Flugzeugwerke AG. This company was then renamed to Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) in 1922. However the name BMW dates back to 1913, when the original company to use the name was founded by Karl Rapp (initially as Rapp Motorenwerke GmbH). The name and Rapp Motorenwerke’s engine-production assets were transferred to Bayerische Flugzeugwerke in 1922, who adopted the name the same year.[3] BMW’s first product was a straight-six aircraft engine called the BMW IIIa, designed in the spring of 1917 by engineer Max Friz. Following the end of World War I, BMW remained in business by producing motorcycle engines, farm equipment, household items and railway brakes. The company produced its first motorcycle, the BMW R 32 in 1923.

BMW became an automobile manufacturer in 1928 when it purchased Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach, which, at the time, built Austin Sevens under licence under the Dixi marque.[4] The first car sold as a BMW was a rebadged Dixi called the BMW 3/15, following BMW’s acquisition of the car manufacturer Automobilwerk Eisenach. Throughout the 1930s, BMW expanded its range into sports cars and larger luxury cars.

Aircraft engines, motorcycles, and automobiles would be BMW’s main products until World War II. During the war, BMW concentrated on aircraft engine production using as many as 40,000 slave laborers.[5] These consisted primarily of prisoners from concentration camps, most prominently Dachau. Motorcycles remained as a side-line and automobile manufacture ceased altogether.

BMW’s factories were heavily bombed during the war and its remaining West German facilities were banned from producing motor vehicles or aircraft after the war. Again, the company survived by making pots, pans, and bicycles. In 1948, BMW restarted motorcycle production. BMW resumed car production in Bavaria in 1952 with the BMW 501 luxury saloon. The range of cars was expanded in 1955, through the production of the cheaper Isetta microcar under licence. Slow sales of luxury cars and small profit margins from microcars meant BMW was in serious financial trouble and in 1959 the company was nearly taken over by rival Daimler-Benz.

A large investment in BMW by Herbert Quandt and Harald Quandt resulted in the company surviving as a separate entity. The Quandts’ father, Günther Quandt, was a well-known German industrialist. Quandt joined the Nazi party in 1933 and made a fortune arming the German Wehrmacht, manufacturing weapons and batteries.[6][better source needed] Many of his enterprises were appropriated from Jewish owners under duress with minimal compensation. At least three of his enterprises made extensive use of slave laborers, as many as 50,000 in all.[7][better source needed] One of his battery factories had its own on-site concentration camp, complete with gallows. Life expectancy for laborers was six months.[8] While Quandt and BMW were not directly connected during the war, funds amassed in the Nazi era by his father allowed Herbert Quandt to buy BMW.[5]

The BMW 700 was successful and assisted in the company’s recovery.

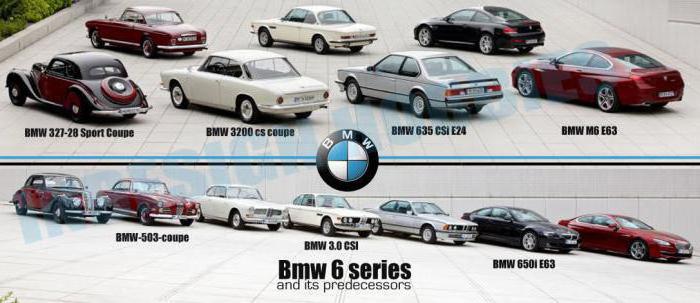

The 1962 introduction of the BMW New Class compact sedans was the beginning of BMW’s reputation as a leading manufacturer of sport-oriented cars. Throughout the 1960s, BMW expanded its range by adding coupe and luxury sedan models. The BMW 5 Series mid-size sedan range was introduced in 1972, followed by the BMW 3 Series compact sedans in 1975, the BMW 6 Series luxury coupes in 1976 and the BMW 7 Series large luxury sedans in 1978.

The BMW M division released its first road car, a mid-engine supercar, in 1978. This was followed by the BMW M5 in 1984 and the BMW M3 in 1986. Also in 1986, BMW introduced its first V12 engine in the 750i luxury sedan.

The company purchased the Rover Group in 1994, however the takeover was not successful and was causing BMW large financial losses. In 2000, BMW sold off most of the Rover brands, retaining only the Mini brand.

In 1998, BMW also acquired the rights to the Rolls-Royce brand from Vickers Plc.

The 1995 BMW Z3 expanded the line-up to include a mass-production two-seat roadster and the 1999 BMW X5 was the company’s entry into the SUV market.

The first modern mass-produced turbocharged petrol engine was introduced in 2006, (from 1973 to 1975, BMW built 1672 units of a turbocharged M10 engine for the BMW 2002 turbo),[9] with most engines switching over to turbocharging over the 2010s. The first hybrid BMW was the 2010 BMW ActiveHybrid 7, and BMW’s first mass-production electric car was the BMW i3 city car, which was released in 2013, (from 1968 to 1972, BMW built two battery-electric BMW 1602 Elektro saloons for the 1972 Olympic Games).[10] After many years of establishing a reputation for sporting rear-wheel drive cars, BMW’s first front-wheel drive car was the 2014 BMW 2 Series Active Tourer multi-purpose vehicle (MPV).

In January 2021, BMW announced that its sales in 2020 fell by 8.4% due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions. However, in the fourth quarter of 2020, BMW witnessed a rise of 3.2% of its customers’ demands.[11]

On 18 January 2022, BMW announced a new limited edition M760Li xDrive simply called «The Final V12,»[12] the last BMW series production vehicle to be fitted with a V-12 engine.[12]

BMW and Toyota aim to sell jointly-developed hydrogen fuel cell vehicles as soon as 2025.[13][14]

Branding

BMW badge on a 1931 Dixi

Company name

BMW is an abbreviation for Bayerische Motoren Werke (German pronunciation: [ˈbaɪ̯ʁɪʃə mɔˈtʰɔʁn̩ ˈvɛɐ̯kə]). This name is grammatically incorrect (in German, compound words must not contain spaces), which is why the name’s grammatically correct form Bayerische Motorenwerke (German pronunciation: [ˈbaɪ̯ʁɪʃə mɔˈtʰɔʁn̩vɛɐ̯kə] (listen)) has been used in several publications and advertisements in the past.[15][16] Bayerische Motorenwerke translates into English as Bavarian Motor Works.[17] The suffix AG, short for Aktiengesellschaft, signifies an incorporated entity which is owned by shareholders, thus akin to «Inc.» (US) or PLC, «Public Limited Company» (UK).

The terms Beemer, Bimmer and Bee-em are sometimes used as slang for BMW in the English language[18][19] and are sometimes used interchangeably for cars and motorcycles.[20][21][22]

Logo

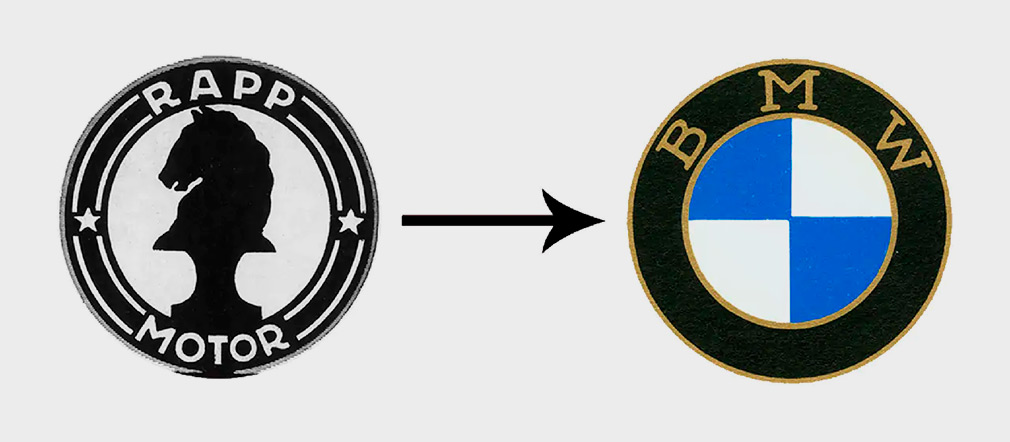

The circular blue and white BMW logo or roundel evolved from the circular Rapp Motorenwerke company logo, which featured a black ring bearing the company name surrounding the company logo,[23] on a plinth a horse’s head couped.[24]

BMW retained Rapp’s black ring inscribed with the company name, but adopted as the central element a circular escutcheon bearing a quasi-heraldic reference to the coat of arms (and flag) of the Free State of Bavaria (as the state of their origin was named after 1918), being the arms of the House of Wittelsbach, Dukes and Kings of Bavaria.[23] However, as the local law regarding trademarks forbade the use of state coats of arms or other symbols of sovereignty on commercial logos, the design was sufficiently differentiated to comply, but retained the tinctures azure (blue) and argent (white).[23][25][26]

The current iteration of the logo was introduced in 2020,[27] removing 3D effects that had been used in renderings of the logo, and also removing the black outline encircling the rondel. The logo will be used on BMW’s branding but will not be used on vehicles.[28][29]

-

Logo used in vehicles

-

The logo on a BMW car

-

Logo used for publicity purposes since March 2020

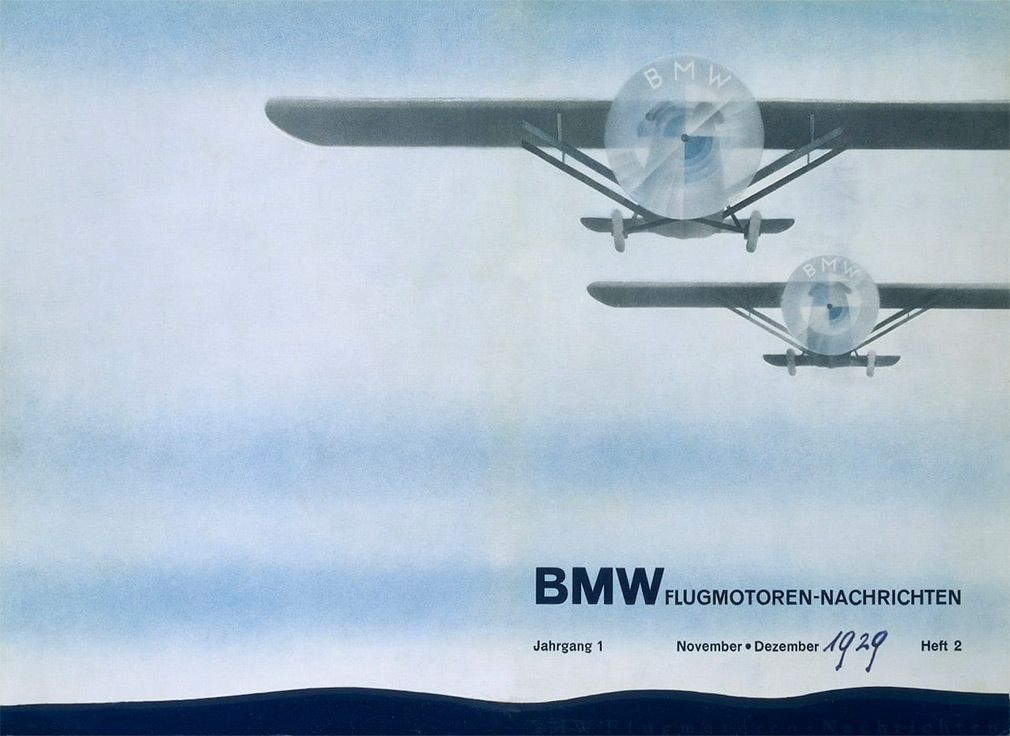

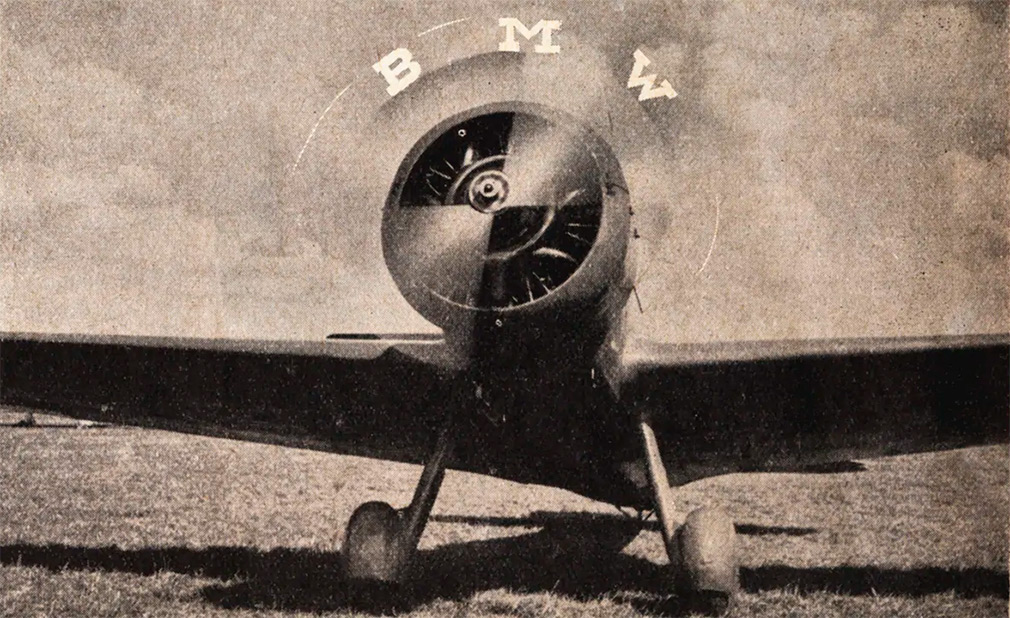

The origin of the logo as a portrayal of the movement of an aircraft propeller, the BMW logo with the white blades seeming to cut through a blue sky, is a myth which sprang from a 1929 BMW advertisement depicting the BMW emblem overlaid on a rotating propeller, with the quarters defined by strobe-light effect, a promotion of an aircraft engine then being built by BMW under license from Pratt & Whitney.[23]

For a long time, BMW made little effort to correct the myth that the BMW badge is a propeller

— Fred Jakobs, Archive Director, BMW Group Classic, [23]

It is well established that this propeller portrayal was first used in a BMW advertisement in 1929 – twelve years after the logo was created – so this is not the true origin of the logo.[30]

Slogan

The slogan ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’ was first used in North America in 1974.[31][32] In 2010, this long-lived campaign was mostly supplanted by a campaign intended to make the brand more approachable and to better appeal to women, ‘Joy’. By 2012 BMW had returned to ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’.[33]

Finances

For the fiscal year 2017, BMW reported earnings of EUR 8.620 billion, with an annual revenue of EUR 98.678 billion, an increase of 4.8% over the previous fiscal cycle.[34] BMW’s shares traded at over €77 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at US 55.3 billion in November 2018.[35]

| Year | Revenue in bn. EUR€ |

Net income in bn. EUR€ |

Total Assets in bn. EUR€ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 68.821 | 4.881 | 123.429 | 100,306 |

| 2012 | 76.848 | 5.096 | 131.850 | 105,876 |

| 2013 | 76.058 | 5.314 | 138.368 | 110,351 |

| 2014 | 80.401 | 5.798 | 154.803 | 116,324 |

| 2015 | 92.175 | 6.369 | 172.174 | 122,244 |

| 2016 | 94.163 | 6.863 | 188.535 | 124,729 |

| 2017 | 98.678 | 8.620 | 193.483 | 129,932 |

| 2018 | 97.480 | 7.117 | 208.980 | 134,682 |

| 2019 | 104.210 | 4.915 | 241.663 | 133,778 |

| 2020 | 98.990 | 3.775 | 216.658 | 120,726 |

| 2021 | 111.239 | 12.382 | 229.527 | 118,909 |

Motorcycles

BMW began production of motorcycle engines and then motorcycles after World War I.[36] Its motorcycle brand is now known as BMW Motorrad. Their first successful motorcycle after the failed Helios and Flink, was the «R32» in 1923, though production originally began in 1921.[37] This had a «boxer» twin engine, in which a cylinder projects into the air-flow from each side of the machine. Apart from their single-cylinder models (basically to the same pattern), all their motorcycles used this distinctive layout until the early 1980s. Many BMW’s are still produced in this layout, which is designated the R Series.

The entire BMW Motorcycle production has, since 1969, been located at the company’s Berlin-Spandau factory.

During the Second World War, BMW produced the BMW R75 motorcycle with a motor-driven sidecar attached, combined with a lockable differential, this made the vehicle very capable off-road.[38][39]

In 1982, came the K Series, shaft drive but water-cooled and with either three or four cylinders mounted in a straight line from front to back. Shortly after, BMW also started making the chain-driven F and G series with single and parallel twin Rotax engines.

In the early 1990s, BMW updated the airhead Boxer engine which became known as the oilhead. In 2002, the oilhead engine had two spark plugs per cylinder. In 2004 it added a built-in balance shaft, an increased capacity to 1,170 cc (71 cu in) and enhanced performance to 75 kW (101 hp) for the R1200GS, compared to 63 kW (84 hp) of the previous R1150GS. More powerful variants of the oilhead engines are available in the R1100S and R1200S, producing 73 and 91 kW (98 and 122 hp), respectively.

In 2004, BMW introduced the new K1200S Sports Bike which marked a departure for BMW. It had an engine producing 125 kW (168 hp), derived from the company’s work with the Williams F1 team, and is lighter than previous K models. Innovations include electronically adjustable front and rear suspension, and a Hossack-type front fork that BMW calls Duolever.

BMW introduced anti-lock brakes on production motorcycles starting in the late 1980s. The generation of anti-lock brakes available on the 2006 and later BMW motorcycles paved the way for the introduction of electronic stability control, or anti-skid technology later in the 2007 model year.

BMW has been an innovator in motorcycle suspension design, taking up telescopic front suspension long before most other manufacturers. Then they switched to an Earles fork, front suspension by swinging fork (1955 to 1969). Most modern BMWs are truly rear swingarm, single sided at the back (compare with the regular swinging fork usually, and wrongly, called swinging arm).

Some BMWs started using yet another trademark front suspension design, the Telelever, in the early 1990s. Like the Earles fork, the Telelever significantly reduces dive under braking.

BMW Group, on 31 January 2013, announced that Pierer Industrie AG has bought Husqvarna Motorcycles for an undisclosed amount, which will not be revealed by either party in the future. The company is headed by Stephan Pierer (CEO of KTM). Pierer Industrie AG is 51% owner of KTM and 100% owner of Husqvarna.

In September 2018, BMW unveiled a new self-driving motorcycle with BMW Motorrad with a goal of using the technology to help improve road safety.[40] The design of the bike was inspired by the company’s BMW R1200 GS model.[41]

Automobiles

Current models

The current model lines of BMW cars are:

- 1 Series five-door hatchbacks (model code F40). A four-door sedan variant (model code F52) is also sold in China and Mexico.[42]

- 2 Series two-door coupes (model code G42), «Active Tourer» five-seat MPVs (U06) and four-door «Gran Coupe» fastback sedans (model code F44).

- 3 Series four-door sedans (model code G20) and five-door station wagons (G21).

- 4 Series two-door coupes (model code G22), two-door convertibles (model code G23) and five-door «Gran Coupe» fastbacks (model code G26).

- 5 Series four-door sedans (model code G30) and five-door station wagons (G31). A long-wheelbase sedan variant (G38) is also sold in China.

- 6 Series «Gran Turismo» five-door fastbacks (model code G32)

- 7 Series four-door sedans (model code G70).

- 8 Series two-door coupes (model code G14), two-door convertibles (G15) and «Gran Coupe» four-door fastback sedans (G16).

-

2 Series Gran Coupé (F44)

The current model lines of the X Series SUVs and crossovers are:

- X1 (U11)

- X2 (F39)

- X3 (G01)

- X4 (G02)

- X5 (G05)

- X6 (G06)

- X7 (G07)

The current model line of the Z Series two-door roadsters is the Z4 (model code G29).

i models

All-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles are sold under the BMW i sub-brand. The current model range consists of:

- i4 D-segment (compact) liftback, powered by one or two electric motors

- i7 F-segment (full-size) sedan, powered by two electric motors

- iX1 C-segment (subcompact) SUV, powered by two electric motors

- iX3 D-segment (compact) SUV, powered by one electric motor

- iX E-segment (mid-size) SUV, powered by two electric motors

In addition, several plug-in hybrid models built on existing platforms have been marketed as iPerformance models. Examples include the 225xe using a 1.5 L three-cylinder turbocharged petrol engine with an electric motor, the 330e/530e using a 2.0 L four-cylinder engine with an electric motor, and the 740e using a 2.0 litre turbocharged petrol engine with an electric motor.[43] Also, crossover and SUV plug-in hybrid models have been released using i technology: X1 xDrive25e, X2 xDrive25e, X3 xDrive30e, and X5 xDrive40e.[44]

M models

The BMW M GmbH subsidiary (called BMW Motorsport GmbH until 1993) started making high-performance versions of various BMW models in 1978.

As of September 2022, the M lineup is:[45]

- M3 four-door sedan and five-door station wagon

- M4 two-door coupe/convertible

- M5 four-door sedan

- M8 two-door coupe/convertible and four-door sedan

- X3 M compact SUV[46]

- X4 M compact coupe SUV[46]

- X5 M mid-size SUV[47]

- X6 M mid-size coupe SUV[48]

The letter «M» is also often used in the marketing of BMW’s regular models, for example the F20 M140i model, the G11 M760Li model and various optional extras called «M Sport», «M Performance» or similar.

Naming convention for models

Motorsport

BMW has a long history of motorsport activities, including:

- Touring cars, such as DTM, WTCC, ETCC and BTCC

- Formula One

- Endurance racing, such as 24 Hours Nürburgring, 24 Hours of Le Mans, 24 Hours of Daytona and Spa 24 Hours

- Isle of Man TT

- Dakar Rally

- American Le Mans Series

- IMSA SportsCar Championship

- Formula BMW – a junior racing Formula category.

- Formula Two

- Formula E

Involvement in the arts

Art Cars

In 1975, sculptor Alexander Calder was commissioned to paint the BMW 3.0 CSL racing car driven by Hervé Poulain at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, which became the first in the series of BMW Art Cars. Since Calder’s work of art, many other renowned artists throughout the world have created BMW Art Cars, including David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol.[49] To date, a total of 19 BMW Art Cars, based on both racing and regular production vehicles, have been created.

-

1975 3.0 CSL Art Car by Alexander Calder

-

1979 M1 Art Car by Andy Warhol

Architecture

The global BMW Headquarters in Munich represents the cylinder head of a 4-cylinder engine. It was designed by Karl Schwanzer and was completed in 1972. The building has become a European icon[49] and was declared a protected historic building in 1999. The main tower consists of four vertical cylinders standing next to and across from each other. Each cylinder is divided horizontally in its center by a mold in the facade. Notably, these cylinders do not stand on the ground; they are suspended on a central support tower.

BMW Museum is a futuristic cauldron-shaped building, which was also designed by Karl Schwanzer and opened in 1972.[50] The interior has a spiral theme and the roof is a 40-metre diameter BMW logo.

BMW Welt, the company’s exhibition space in Munich, was designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au and opened in 2007. It includes a showroom and lifting platforms where a customer’s new car is theatrically unveiled to the customer.[51]

-

BMW Museum

-

BMW Welt

Film

In 2001 and 2002, BMW produced a series of 8 short films called The Hire, which had plots based around BMW models being driven to extremes by Clive Owen.[52] The directors for The Hire included Guy Ritchie, John Woo, John Frankenheimer and Ang Lee. In 2016, a ninth film in the series was released.

The 2006 «BMW Performance Series» was a marketing event geared to attract black car buyers. It consisted of seven concerts by jazz musician Mike Phillips, and screenings of films by black filmmakers.[53][54]

Visual arts

BMW was the principal sponsor of the 1998 The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition at various Guggenheim museums, though the financial relationship between BMW and the Guggenheim Foundation was criticised in many quarters.[55][56]

In 2012, BMW began sponsoring Independent Collectors production of the BMW Art Guide, which is the first global guide to private and publicly accessible collections of contemporary art worldwide.[57] The fourth edition, released in 2016, features 256 collections from 43 countries.[58]

Production and sales

BMW produces complete automobiles in the following countries:

- Germany: Munich, Dingolfing, Regensburg and Leipzig

- Austria: Graz[59]

- United States: Spartanburg[60]

- Mexico: San Luis Potosí[61]

- South Africa: Rosslyn

- India: Chennai

- China: Shenyang

- Brazil: Araquari

BMW also has local assembly operation using complete knock-down (CKD) components in Thailand, Russia, Egypt, Indonesia, Malaysia and India.[62]

In the UK, BMW has a Mini factory near Oxford, plants in Swindon and Hams Hall, and Rolls-Royce vehicle assembly at Goodwood. In 2020, these facilities were shut down for the period from March 23 to April 17 due to the coronavirus outbreak.[63]

The BMW group (including Mini and Rolls-Royce) produced 1,366,838 automobiles in 2006 and then 1,481,253 automobiles in 2010.[64][65] BMW Motorcycles are being produced at the company’s Berlin factory, which earlier had produced aircraft engines for Siemens.

By 2011, about 56% of BMW-brand vehicles produced are powered by petrol engines and the remaining 44% are powered by diesel engines. Of those petrol vehicles, about 27% are four-cylinder models and about nine percent are eight-cylinder models.[66] On average, 9,000 vehicles per day exit BMW plants, and 63% are transported by rail.[67]

Annual production since 2005, according to BMW’s annual reports:[65]

| Year | BMW | MINI | Rolls-Royce | Motorcycle* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,122,308 | 200,119 | 692 | 92,013 |

| 2006 | 1,179,317 | 186,674 | 847 | 103,759 |

| 2007 | 1,302,774 | 237,700 | 1,029 | 104,396 |

| 2008 | 1,203,482 | 235,019 | 1,417 | 118,452 |

| 2009 | 1,043,829 | 213,670 | 918 | 93,243 |

| 2010 | 1,236,989 | 241,043 | 3,221 | 112,271 |

| 2011 | 1,440,315 | 294,120 | 3,725 | 110,360 |

| 2012 | 1,547,057 | 311,490 | 3,279 | 113,811 |

| 2013 | 1,699,835 | 303,177 | 3,354 | 110,127 |

| 2014 | 1,838,268 | 322,803 | 4,495 | 133,615 |

| 2015 | 1,933,647 | 342,008 | 3,848 | 151,004 |

| 2016 | 2,002,997 | 352,580 | 4,179 | 145,555 |

| 2017 | 2,123,947 | 378,486 | 3,308 | 185,682 |

| 2018 | 2,168,496 | 368,685 | 4,353 | 162,687 |

| 2019 | 2,205,841 | 352,729 | 5,455 | 187,116 |

| 2020 | 1,980,740 | 271,121 | 3,776 | 168,104 |

| 2021 | 2,166,644 | 288,713 | 5,912 | 187,500 |

Annual sales since 2005, according to BMW’s annual reports:

| Year | BMW | MINI | Rolls-Royce | Motorcycle* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,126,768 | 200,428 | 797 | 97,474 |

| 2006 | 1,185,089 | 188,077 | 805 | 100,064 |

| 2007 | 1,276,793 | 222,875 | 1,010 | 102,467 |

| 2008 | 1,202,239 | 232,425 | 1,212 | 115,196 |

| 2009 | 1,068,770 | 216,538 | 1,002 | 100,358 |

| 2010 | 1,224,280 | 234,175 | 2,711 | 110,113 |

| 2011 | 1,380,384 | 285,060 | 3,538 | 113,572 |

| 2012 | 1,540,085 | 301,525 | 3,575 | 117,109 |

| 2013 | 1,655,138 | 305,030 | 3,630 | 115,215** |

| 2014 | 1,811,719 | 302,183 | 4,063 | 123,495 |

| 2015 | 1,905,234 | 338,466 | 3,785 | 136,963 |

| 2016 | 2,003,359 | 360,233 | 4,011 | 145,032 |

| 2017 | 2,088,283 | 371,881 | 3,362 | 164,153 |

| 2018 | 2,114,963 | 364,135 | 4,194 | 165,566 |

| 2019 | 2,185,793 | 347,474 | 5,100 | 175,162 |

| 2020 | 2,028,841 | 292,582 | 3,756 | 169,272 |

| 2021 | 2,213,379 | 302,138 | 5,586 | 194,261 |

* In 2008–2012, motorcycle productions figures include Husqvarna models.

** Excluding Husqvarna, sales volume up to 2013: 59,776 units.

Recalls

In November 2016, BMW recalled 136,000 2007–2012 model year U.S. cars for fuel pump wiring problems possibly resulting in fuel leak and engine stalling or restarting issues.[68]

In 2018, BMW recalled 106,000 diesel vehicles in South Korea with a defective exhaust gas recirculation module, which caused 39 engine fires. The recall was then expanded to 324,000 more cars in Europe.[69] Following the recall in South Korea, the government banned cars which had not yet been inspected from driving on public roads.[70] This affected up to 25% of the recalled cars, where the owners had been notified but the cars had not yet been inspected. BMW is reported to have been aware since 2016 that more than 4% of the affected cars in South Korea had experienced failures in the EGR coolers,[71] leading to approximately 20 owners suing the company.[72]

Industry collaboration

BMW has collaborated with other car manufacturers on the following occasions:

- McLaren Automotive: BMW designed and produced the V12 engine that powered the McLaren F1.[73][74]

- Groupe PSA (predecessor to Stellantis): Joint production of four-cylinder petrol engines, beginning in 2004.[75]

- Daimler Benz: Joint venture to produce the hybrid drivetrain components used in the ActiveHybrid 7.[76][77] Development of automated driving technology.[78]

- Toyota: Three-part agreement in 2013 to jointly develop fuel cell technology, develop a joint platform for a sports car (for the 2018 BMW Z4 (G29) and Toyota Supra) and research lithium-air batteries.[79][80][81]

- Audi and Mercedes: Joint purchase of Nokia’s Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps) in 2015.[82]

- In 2018, Horizn Studios collaborated with BMW to launch special luggage editions.[83]

BMW sponsor car at the London 2012 Olympics

BMW made a six-year sponsorship deal with the United States Olympic Committee in July 2010.[84][85]

In golf, BMW has sponsored various events,[86] including the PGA Championship since 2007,[87][88] the Italian Open from 2009 to 2012, the BMW Masters in China from 2012 to 2015[89][90] and the BMW International Open in Munich since 1989.[91]

In rugby, BMW sponsored the South Africa national rugby union team from 2011 to 2015.[92][93]

Environmental record

BMW is a charter member of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) National Environmental Achievement Track, which recognizes companies for their environmental stewardship and performance.[94] It is also a member of the South Carolina Environmental Excellence Program.[95]

Since 1999, BMW has been named the world’s most sustainable automotive company every year by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.[96] The BMW Group is one of three automotive companies to be featured every year in the index.[97] In 2001, the BMW Group committed itself to the United Nations Environment Programme, the UN Global Compact and the Cleaner Production Declaration. It was also the first company in the automotive industry to appoint an environmental officer, in 1973.[98] BMW is a member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.[99]

In 2012, BMW was the highest automotive company in the Carbon Disclosure Project’s Global 500 list, with a score of 99 out of 100.[100][101] The BMW Group was rated the most sustainable DAX 30 company by Sustainalytics in 2012.[102]

To reduce vehicle emissions, BMW is improving the efficiency of existing fossil-fuel powered models, while researching electric power, hybrid power and hydrogen for future models.[103]

During the first quarter of 2018, BMW sold 26,858 Electrified Vehicles (EVs, PHEVs, & Hybrids).[104]

Car-sharing services

DriveNow was a joint-venture between BMW and Sixt that operated from in Europe from 2011 until 2019. By December 2012,[105] DriveNow operated over 1,000 vehicles, in five cities and with approximately 60,000 customers.[106]

In 2012, the BMW-owned subsidiary Alphabet began a corporate car-sharing service in Europe called AlphaCity.[107][108]

The ReachNow car-sharing service was launched in Seattle in April 2016.[109] ReachNow currently operates in Seattle, Portland and Brooklyn.

In 2018, BMW announced the launching of a pilot car subscription service for the United States called Access by BMW (its first one for the country), in Nashville, Tennessee. In January 2021, the company said that Access by BMW was «suspended».[110]

Overseas subsidiaries

Production facilities

China

The first BMW production facility in China was opened in 2004, as a result of a joint venture between BMW and Brilliance Auto.[111][112] The plant was opened in the Shenyang industrial area and produces 3 Series and 5 Series models for the Chinese market.[113][114] In 2012, a second factory was opened in Shenyang.[115]

Between January and November 2014, BMW sold 415,200 vehicles in China, through a network of over 440 BMW stores and 100 Mini stores.[116]

On 7 October 2021, BMW announced to be moving the production of the X5 from the United States to China.[117]

In February 2022, BMW invested an additional $4.2 billion into the Chinese joint venture, increasing its stake from 50% to 75%, becoming one of the first foreign automakers holding majority stake in China.[118]

In June 2022, BMW announced a new plant project in Lydia, Shenyang designed for electric vehicles. It will become BMW Group’s largest single project in China, costing 15 billion yuan (2.13 billion euros).[119] The investment amount was raised by a further 10 billion yuan (US$1.4 billion) in November 2022, following German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s visit to China.[120]

Hungary

On 31 July 2018, BMW announced to build 1 billion euro car factory in Hungary. The plant, to be built near Debrecen, will have a production capacity of 150,000 cars a year.[121]

Mexico

In July 2014, BMW announced it was establishing a plant in Mexico, in the city and state of San Luis Potosi involving an investment of $1 billion. The plant will employ 1,500 people, and produce 150,000 cars annually.[122]

Netherlands

The Mini Convertible, Mini Countryman and BMW X1 are currently produced in the Netherlands at the VDL Nedcar factory in Born.[123][124] Long-term orders for the Mini Countryman ended in 2020.[125]

South Africa

BMWs have been assembled in South Africa since 1968,[126] when Praetor Monteerders’ plant was opened in Rosslyn, near Pretoria. BMW initially bought shares in the company, before fully acquiring it in 1975; in so doing, the company became BMW South Africa, the first wholly owned subsidiary of BMW to be established outside Germany. Unlike United States manufacturers, such as Ford and GM, which divested from the country in the 1980s, BMW retained full ownership of its operations in South Africa.

Following the end of apartheid in 1994, and the lowering of import tariffs, BMW South Africa ended local production of the 5 Series and 7 Series, in order to concentrate on production of the 3 Series for the export market. South African–built BMWs are now exported to right hand drive markets including Japan, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa. Since 1997, BMW South Africa has produced vehicles in left-hand drive for export to Taiwan, the United States and Iran, as well as South America.

Three unique models that BMW Motorsport created for the South African market were the E23 M745i (1983), which used the M88 engine from the BMW M1, the BMW 333i (1986), which added a six-cylinder 3.2-litre M30 engine to the E30,[127] and the E30 BMW 325is (1989) which was powered by an Alpina-derived 2.7-litre engine.

The plant code (position 11 in the VIN) for South African built models is «N».[128]

United States

BMW cars have been officially sold in the United States since 1956[129] and manufactured in the United States since 1994.[130] The first BMW dealership in the United States opened in 1975.[131] In 2016, BMW was the twelfth highest selling brand in the United States.[132]

The manufacturing plant in Greer, South Carolina has the highest production of the BMW plants worldwide,[133] currently producing approximately 1,500 vehicles per day.[134] The models produced at the Spartanburg plant are the X3, X4, X6 and X7 SUV models. The X5 model’s production was announced to be moving to China in December 2021.[117]

In addition to the South Carolina manufacturing facility, BMW’s North American companies include sales, marketing, design, and financial services operations in the United States, Mexico, Canada and Latin America.

Complete knock-down assembly facilities

Brazil

On 9 October 2014, BMW’s new complete knock-down (CKD) assembly plant in Araquari, assembled its first car— an F30 3 Series.[135][136]

The cars assembled at Araquari are the F20 1 Series, F30 3 Series, F48 X1, F25 X3 and Mini Countryman.[137]

Egypt

Bavarian Auto Group became the importer of the BMW and Mini brands in 2003.

Since 2005, the 3 Series, 5 Series, 7 Series, X1 and X3 models sold in Egypt are assembled from complete knock-down components at the BMW plant in 6th of October City.[137]

India

BMW India was established in 2006 as a sales subsidiary with a head office located in Gurugram.

A BMW complete knock-down assembly plant was opened in Chennai in 2007, assembling Indian-market 3 Series, 5 Series, 7 Series, X1, X3, X5, Mini Countryman and motorcycle models.[137][138] The 20 Million Euro plant aims to produce 1,700 cars per year.

Russia

Russian-market 3 Series and 5 Series cars are assembled from complete knock-down components in Kaliningrad beginning in 1999.[139] In March 2022, BMW left Russian market and stopped importing and producing cars in Russia due to International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War.[140]

Malaysia

BMW’s complete knock-down (CKD) assembly plant in Kedah. Assembled Malaysia-market 1 Series, 3 Series, 5 Series, 7 Series, X1, X3, X4, X5, X6 and Mini Countryman since 2008.[141]

Vehicle importers

Canada

BMW’s first dealership in Canada, located in Ottawa, was opened in 1969.[142] In 1986, BMW established a head office in Canada.[143]

BMW sold 28,149 vehicles in Canada in 2008.[144]

Japan

BMW Japan Corp, a wholly owned subsidiary, imports and distributes BMW vehicles in Japan.[145]

Philippines

BMW Philippines, an owned subsidiary of San Miguel Corporation, is the official importer and distributor of BMW in the Philippines.[146]

BMW sold 920 vehicles in the Philippines in 2019.[147]

South Korea

BMW Korea imports BMW vehicles in South Korea with more than fifty service centers to fully accomplish to South Korean customers. Also, BMW Korea has its own driving center in Incheon.[148]

See also

- BMW Group Classic

- List of BMW engines

References

- ^ a b c d e f g «BMW Group Report 2021» (PDF). BMW. pp. 9, 10, 105, 152. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ «World Motor Vehicle Production: OICA Correspondents Survey» (PDF). OICA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ «BMW name, meaning, and history». bmw.com.

- ^ Odin, L.C. World in Motion 1939 — The whole of the year’s automobile production. Belvedere Publishing, 2015. ASIN: B00ZLN91ZG.

- ^ a b «Horsepower under the hood and skeletons in the closet: BMW celebrates 100 years | DW | 04.03.2016». Deutsche Welle.

- ^ «BMW and the Holocaust».

- ^ «Varta Battery Factories».

- ^ BMW’s Quandt Family to Investigate Wealth Amassed in Third Reich Der Spiegel. 2007.

- ^ BMW Group (ed.): BMW 2002 turbo, retrieved 26 August 2020

- ^ BMW (ed.): BMW 1602 Elektro, retrieved 26 August 2020

- ^ Reuters Staff (12 January 2021). «BMW sales fall 8.4% in 2020 as coronavirus takes toll». Reuters. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ a b Silvestro, Brian (18 January 2022). «BMW Waves Goodbye to the V-12 With a Final Edition M760Li». Road & Track. Hearst Communications.

- ^ Jon Fingas (12 August 2022). «BMW and Toyota plan to release jointly-built fuel cell cars in 2025». Engadget.

- ^ Jaclyn Trop, Tim De Chant (12 August 2022). «EV laggards BMW and Toyota to partner on hydrogen fuel cell vehicles». TechCrunch.

- ^ Hans List: Vorwort und Einführung zum Gesamtwerk. Band 1 von Die Verbrennungskraftmaschine, Springer, Wien, 1949. ISBN 9783662294888. Verzeichnis der Abkürzungen

- ^ Roland Löwisch: BMW — Die schönsten Modelle: 100 Jahre Design und Technik’ by azar’. HEEL, 2016, ISBN 9783958434066. p 7.

- ^ «BMW 1970s brochure for the United States». www.bmw-grouparchiv.de. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ «Bee em / BMW Motorcycle Club of Victoria Inc». National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ «No Toupees allowed». Bangkok Post. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Lighter, Jonathan E. (1994). Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang: A-G. Vol. 1. Random House. pp. 126–27. ISBN 978-0-394-54427-4.

Beemer n. [BMW + »er»] a BMW automobile. Also Beamer.

- ^ Lighter, Jonathan E. (1994). Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang: A-G. Vol. 1. Random House. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-394-54427-4.

Bimmer n. Beemer.

- ^ 1982 S. Black Totally Awesome 83 BMW («Beemer»).

1985 L.A. Times (13 April) V 4: Id much rather drive my Beemer than a truck.

1989 L. Roberts Full Cleveland 39: Baby boomers… in… late-model Beemers.

1990 Hull High (NBC-TV): You should ee my dad’s new Beemer.

1991 Cathy (synd. cartoon strip) (21 April): Sheila… [ground] multi-grain snack chips crumbs into the back seat of my brand-new Beamer!

1992 Time (18 May) 84: Its residents tend to drive pickups or subcompacts, not Beemers or Rolles. - ^ a b c d e «The BMW Logo – meaning and history». BMW. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Described heraldically

- ^ The heraldic blazon of the BMW quasi-heraldic circular escutcheon is Quarterly of 4: 1&4: Azure; 2&3: Argent

- ^ BMW. «The origin of the BMW logo». YouTube. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ BMW changes logo for the digital age, Retrieved March 8, 2020

- ^ «Introducing BMW’s new brand design for online and offline communication». www.press.bmwgroup.com. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (4 March 2020). «BMW’s new flat logo is everything that’s wrong with modern logo design». The Verge. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Stephen Williams (7 January 2010). «BMW Roundel: Not Born From Planes». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ «The Stories Behind 10 of the Most Iconic Brand Slogans». www.highsnobiety.com. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2017.[dead link]

- ^ «Can Lutz repeat his BMW marketing magic at GM?». www.autonews.com. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ «BMW Still the Ultimate Driving Machine». Forbes.com. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ «Unternehmensprofil». wallstreet-online.de. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ «BMW.DE Key Statistics | BAY.MOTOREN WERKE AG ST Stock — Yahoo Finance». finance.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Peter Gantriis, Henry Von Wartenberg. «The Art of BMW: 85 Years of Motorcycling Excellence». MotorBooks International, September 2008, p. 10.

- ^ «What is the history of BMW motorcycles in the USA?». Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ «R75WH». 30 November 2018. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ «BMW R75». Military Factory. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ O’Kane, Sean (12 September 2018). «BMW made a self-driving motorcycle». The Verge. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Su, Jean Baptiste. «BMW Unveils The First Driverless Motorcycle». Forbes. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ «BMW 1 Series Sedan No Longer China-Exclusive; Launched in Mexico». Motor1.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ BMW Group (November 2016). «Electrified by BMW i — BMW iPerformance: Plug-in hybrids with BMW i know-how». BMW.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ «BMW Plug-in Hybrid Models». BMW UK. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020. The 330e and 530e are available as sedan or saloon and wagon or touring trims.

- ^ «BMW M models». BMW USA. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ a b «The all-new BMW X3 M and the all-new BMW X4 M.» www.press.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ «The Next-Generation BMW X5 M Could Debut Early In 2020». www.carbuzz.com. 30 December 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ «2020 BMW X6 (G06) Spied In Spartanburg». www.autoevolution.com. 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ a b Patton, Phil (12 March 2009). «These Canvases Need Oil and a Good Driver». The New York Times. p. AU1. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017.

- ^ Williams, Stephen (31 December 2009). «Touring the Temples of German Automaking». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Schmitt, Bernd; Van Zutphen, Glenn (2012), Happy Customers Everywhere: How Your Business Can Profit from the Insights of Positive Psychology, Macmillan, p. 64, ISBN 9781137000460, archived from the original on 19 March 2018

- ^ «BMW Films». Archived from the original on 25 June 2007.

- ^ «Performance of a Different Kind: BMW arts series aims at black consumers». www.autoweek.com. 10 August 2006. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ «BMW arts series aims at black consumers». Automotive News. Vol. 80, no. 6215. 7 August 2006. p. 37.

- ^ «When merchants enter the temple; Marketing museums». The Economist. 21 April 2001. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (3 August 1998). «Latest Biker Hangout? Guggenheim Ramp». The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ^ «About the Guide – «I don’t think anybody has been to all these places.»«. www.bmw-art-guide.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ «HYPERALLERGIC: The Fourth BMW Art Guide by Independent Collectors». 13 December 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ «BMW increasing Spartanburg production to 200,000 yearly». BMW Car Club of America. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007.

- ^ «Contact Us». www.bmwusfactory.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ «BMW Group Plant San Luis Potosi». Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ «BMW Group». BMW Group. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ «Almost all UK car production paused amid virus fears». BBC News. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ «World Motor Vehicle Production, OICA correspondents survey 2006» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b «Annual Report 2010» (PDF). BMW Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Hilton Holloway (11 February 2011). «The future of BMW’s engines». Autocar. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ Christopher Ludwig (22 December 2016). «BMW’s ‘connected’ logistics: Shaping a self-steering supply chain». Automotive Logistics. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

logistics as the «heart of BMW’s production system»: 30m parts per day move from 1,800 suppliers; 7,000 sea freight containers per day, and in a year 84m cubic metres across ocean, road, rail and air freight. Outbound, around 9,000 vehicles leave BMW plants each day on their way to 4,500 dealers in 160 countries. 63% of cars leave plants by train

- ^ Atiyeh, Clifford (November 2016). «BMW Recalls 136,000 Cars for Fuel Leaks and Stalling». Car and Driver. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Randewich, Noel; Duguid, Kate (7 August 2018). «BMW recalls 324,000 cars in Europe after Korean engine fires: FAZ». Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Mullen, Jethro (14 August 2018). «BMW Recall: South Korea announces ban after engine fires». CNN. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ «BMW코리아 ‘시정계획서’엔…2년 전 결함 인지→본사 보고까지 : 네이버 뉴스». www.naver.com (in Korean). Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ «BMW코리아·본사가 결함 은폐해온 의혹» 차주들, 고소 나선다 : 네이버 뉴스». www.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ «McLaren F1 Supercar». www.caranddriver.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «Jay Leno Pulls Out McLaren F1’s V12 Engine for All to See». www.carscoops.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «PSA, BMW Collaboration Grows». www.wardsauto.com. 19 January 2007. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «2010 BMW ActiveHybrid 7 Review». www.topspeed.com. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «2010 BMW ActiveHybrid 7 – Official Information». www.bmwblog.com. 12 August 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW and Daimler to develop automated driving tech». KERO. 5 July 2019. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ «BMW Group and Toyota Motor Corporation Deepen Collaboration by Signing Binding Agreements». www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW, Toyota Confirm Hydrogen Fuel Cell, Technology Deals». 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016.

- ^ «BMW and Toyota sign Agreement for Fuel Cell System, Sports Vehicle, Lightweight Technology and Lithium-air Battery». www.bmwblog.com. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «Nokia sells Here maps unit to Audi, BMW, and Mercedes for $3 billion». www.theverge.com. 3 August 2015. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ «Horizn Studios Introduces New Product Line». vegconomist.com. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ «BMW, USOC make 6-year sponsorship deal official». www.teamusa.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW to sponsor America’s Olympic committee». www.autonews.com. 23 July 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW Int’l Sponsorship Head Eckhard Wannieck Talks About Company’s Sports Sponsorships». www.sportsbusinessdaily.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW extends sponsorship of BMW Championship». www.pgatour.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «Sponsors». www.pgatour.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «Who Does What: Automobile Manufacturers». www.sponsorship.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «A Slow And Steady Course: Inside BMW’s Sponsorship Strategy». www.sponsorship.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW extends sponsorship of Wentworth PGA event». Sportbusiness.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ «BMW named new Springbok sponsor». www.supersport.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW SA drops the Springboks». www.wheels24.co.za. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ «Performance Track Final Progress Report» (PDF). EPA. May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Sauer, Paul. «Ultimate Factories». Facts: BMW. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ «BMW Group once again sector leader in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. World’s most sustainable automotive company in 2016». www.automotiveworld.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW Group once again sector leader in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. World’s most sustainable automotive company in 2016». www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW Group once again sector leader in Dow Jones Sustainability Index». bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- ^ «BMW AG». Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ «Carbon Disclosure Project Reveals Global Top 10; Apple and Amazon Don’t Respond». www.environmentalleader.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ «Carbon Disclosure Project recognises BMW Group for the exemplary transparency of its climate protection activities — Number One Automotive Manufacturer in the CDP Global 500 ranking». www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ BMW Group (16 May 2014). «BMW Group : Sustainable Value Report 2012 : Sustainability management». bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- ^ Bird, J and Walker, M: «BMW A Sustainable Future? «, page 11. Wild World 2005

- ^ «Record first quarter for BMW Group sales». Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «About DriveNow Car Sharing from BMW & Sixt». www.drive-now.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ «BMW Group takes top prize at the 2012 Corporate Entrepreneur Awards for premium car-sharing joint venture DriveNow. Jury impressed by willingness to trial new models of mobility». Electricdrive.org. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ «Alphabet Business Mobility solutions». www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ «Corporate car sharing scheme claims to be a first». www.fleetnews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ ReachNow official website. «ReachNow | CarSharing by BMW, BMW i, MINI Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.» 8 May 2016.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J (14 January 2021). «BMW becomes the latest automaker to shut down its subscription service». The Verge. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ General Overview Archived 19 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Brilliance Auto Official Site

- ^ «BMW opens China factory». Testdriven.co.uk. 21 May 2004. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ Brands and Products – BMW Sedan Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Brilliance Auto Official Site

- ^ «BMW launches new plant in Shenyang». english.people.com.cn. 21 May 2004. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Schmidt, Nico (24 May 2012). «BMW to Boost China Investment». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ «BMW to Pay $820 Million to China Car Dealers, Group Says». Bloomberg News. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b «BMW to add X5 production in China -spokesperson». Reuters. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Waldersee, Victoria (11 February 2022). «BMW pays $4.2 BLN to take control of Chinese JV». Reuters.

- ^ «BMW to open a new factory in Shenyang». 23 June 2022.

- ^ «BMW confirms it will invest another US$1.4 billion in Chinese EV battery plant». 14 November 2022.

- ^ «BMW to build 1 billion euro car factory in Hungary». Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ «Joining rivals, BMW to set up $1bn plant in Mexico». Mexico Star. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ «BMW Group Report 2020» (PDF). BMW Group. March 2021. p. 93. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ «Nedcar rescue deal finalised». Dutch News. 1 October 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ «VDL Nedcar: no new follow-up order for MINI Countryman». VDL Groep. 15 October 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ «Corporate Information: History». BMW South Africa. Archived from the original on 25 April 2007.

- ^ «BMW South Africa – Plant Rosslyn». Bmwplant.co.za. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ «Manufacturer’s Information Dabase». NHTSA.

- ^ «Isetta 300 model selection». www.realoem.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ «Company — History». www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ «This is how BMW became the top selling luxury car company in the U.S.» www.fortune.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ «Sales by Manufacturer». www.edmunds.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW Plant Spartanburg leads U.S. auto exports». Roundel. BMW Car Club of America: 30. April 2015. ISSN 0889-3225.

- ^ «Production». BMW Manufacturing Co. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ «BMW Group assembles first car in Brazil». press.bmwgroup.com. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ «BMW Brazil to export X1 SUVs to US». www.just-auto.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ a b c «BMW: Global growth». www.automotivemanufacturingsolutions.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ Interone Worldwide GmbH (11 December 2006). «International BMW website». Bmw.in. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ Production of new BMW 5 series begins in Kaliningrad — Pravda.Ru Archived 15 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «BMW приостанавливает производство и импорт автомобилей в Россию» (in Russian). Интерфакс. 1 March 2022.

- ^ «BMW: Global growth». Automotive Manufacturing Solutions. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ «The Otto’s Story». www.bmwottos.ca. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ «In photos: The evolution and history of BMW as it turns 100». www.theglobeandmail.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ «History of BMW Canada». www.bmwlondon.ca. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ «About BMW Japan Corp». www.bmwcareer.jp. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ «BMW Philippines». Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ «Philippine auto industry reports 416,637 unit sales in 2019». autoindustriya.com. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ «Introduction to BMW Korea». Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

Further reading

- Grunert, Manfred; Triebe, Florian (2006). Das Unternehmen BMW seit 1916 [The BMW Company since 1916] (in German). Königswinter, Germany: Heel Verlag. ISBN 3932169468.

- Hodges, David (2000). BMW. Suttons Photographic History of Transport series. Stroud, Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750921447.

- Kiley, David (2004). Driven: Inside BMW, the Most Admired Car Company in the World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26920-5.

- Lewandowski, Jürgen (2006). BMW: Typen und Geschichte [BMW: Types and History] (in German) (3rd ed.). Bielefeld: Delius Klasing. ISBN 3768814203.

- Lewin, Tony (2022). BMW Century (2nd ed.). Beverly, MA, USA: Motorbooks. ISBN 9780760373774.

- Noakes, Andrew (2010). The Ultimate History of BMW: From the innovative 328 sports car and the Isetta bubble car to the 5 Series Gran Turismo. Bath: Parragon Books. ISBN 9781407549781.

- Schrader, Halwart (2011). BMW: Passion · Power · Perfektion [BMW: Passion · Power · Perfection] (in German). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 9783613033788.

- ———————— (2016). BMW: Von 1981 bis heute [BMW: From 1981 to today]. Typenkompass series (in German). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 9783613038721.

- Werner, Constanze (2006). Kriegswirtschaft und Zwangsarbeit bei BMW [War Economy and Forced Labour at BMW] (in German). München: Oldenbourg. ISBN 3486577921.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to BMW.

- Official website

This article is about the German motor vehicle manufacturer. For other uses, see BMW (disambiguation).

Trading logo since 2020 |

|

BMW Headquarters in Munich, Germany |

|

| Type | Public (Aktiengesellschaft) |

|---|---|

|

Traded as |

FWB: BMW DAX Component |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Predecessors | Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik Rapp Motorenwerke Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach |

| Founded | 7 March 1916; 106 years ago (as Bayerische Flugzeugwerke) |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters |

Munich , Germany |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

Oliver Zipse, Chairman of the Board of Management Norbert Reithofer, Chairman of the Supervisory Board |

| Products |

|

|

Production output |

|

| Brands |

|

| Services | Financial services |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owners | Public float (50%); Stefan Quandt (29%), Susanne Klatten (21%) |

|

Number of employees |

118,909 (2021)[1] |

| Website | bmw.com bmwgroup.com |

Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, abbreviated as BMW (German pronunciation: [ˌbeːʔɛmˈveː] (listen)), is a German multinational manufacturer of luxury vehicles and motorcycles headquartered in Munich, Bavaria. The corporation was founded in 1916 as a manufacturer of aircraft engines, which it produced from 1917 until 1918 and again from 1933 to 1945.

Automobiles are marketed under the brands BMW, Mini and Rolls-Royce, and motorcycles are marketed under the brand BMW Motorrad. In 2017, BMW was the world’s fourteenth-largest producer of motor vehicles, with 2,279,503 vehicles produced.[2] The company has significant motor-sport history, especially in touring cars, sports cars, and the Isle of Man TT.

BMW is headquartered in Munich and produces motor vehicles in Germany, Brazil, China, India, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Quandt family is a long-term shareholder of the company (with the remaining shares owned by public float), following investments by the brothers Herbert and Harald Quandt in 1959 which saved the company from bankruptcy.

History

Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik was founded in 1910 by Gustav Otto in Bavaria. The firm was reorganized on 7 March 1916 into Bayerische Flugzeugwerke AG. This company was then renamed to Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) in 1922. However the name BMW dates back to 1913, when the original company to use the name was founded by Karl Rapp (initially as Rapp Motorenwerke GmbH). The name and Rapp Motorenwerke’s engine-production assets were transferred to Bayerische Flugzeugwerke in 1922, who adopted the name the same year.[3] BMW’s first product was a straight-six aircraft engine called the BMW IIIa, designed in the spring of 1917 by engineer Max Friz. Following the end of World War I, BMW remained in business by producing motorcycle engines, farm equipment, household items and railway brakes. The company produced its first motorcycle, the BMW R 32 in 1923.

BMW became an automobile manufacturer in 1928 when it purchased Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach, which, at the time, built Austin Sevens under licence under the Dixi marque.[4] The first car sold as a BMW was a rebadged Dixi called the BMW 3/15, following BMW’s acquisition of the car manufacturer Automobilwerk Eisenach. Throughout the 1930s, BMW expanded its range into sports cars and larger luxury cars.

Aircraft engines, motorcycles, and automobiles would be BMW’s main products until World War II. During the war, BMW concentrated on aircraft engine production using as many as 40,000 slave laborers.[5] These consisted primarily of prisoners from concentration camps, most prominently Dachau. Motorcycles remained as a side-line and automobile manufacture ceased altogether.

BMW’s factories were heavily bombed during the war and its remaining West German facilities were banned from producing motor vehicles or aircraft after the war. Again, the company survived by making pots, pans, and bicycles. In 1948, BMW restarted motorcycle production. BMW resumed car production in Bavaria in 1952 with the BMW 501 luxury saloon. The range of cars was expanded in 1955, through the production of the cheaper Isetta microcar under licence. Slow sales of luxury cars and small profit margins from microcars meant BMW was in serious financial trouble and in 1959 the company was nearly taken over by rival Daimler-Benz.

A large investment in BMW by Herbert Quandt and Harald Quandt resulted in the company surviving as a separate entity. The Quandts’ father, Günther Quandt, was a well-known German industrialist. Quandt joined the Nazi party in 1933 and made a fortune arming the German Wehrmacht, manufacturing weapons and batteries.[6][better source needed] Many of his enterprises were appropriated from Jewish owners under duress with minimal compensation. At least three of his enterprises made extensive use of slave laborers, as many as 50,000 in all.[7][better source needed] One of his battery factories had its own on-site concentration camp, complete with gallows. Life expectancy for laborers was six months.[8] While Quandt and BMW were not directly connected during the war, funds amassed in the Nazi era by his father allowed Herbert Quandt to buy BMW.[5]

The BMW 700 was successful and assisted in the company’s recovery.

The 1962 introduction of the BMW New Class compact sedans was the beginning of BMW’s reputation as a leading manufacturer of sport-oriented cars. Throughout the 1960s, BMW expanded its range by adding coupe and luxury sedan models. The BMW 5 Series mid-size sedan range was introduced in 1972, followed by the BMW 3 Series compact sedans in 1975, the BMW 6 Series luxury coupes in 1976 and the BMW 7 Series large luxury sedans in 1978.

The BMW M division released its first road car, a mid-engine supercar, in 1978. This was followed by the BMW M5 in 1984 and the BMW M3 in 1986. Also in 1986, BMW introduced its first V12 engine in the 750i luxury sedan.

The company purchased the Rover Group in 1994, however the takeover was not successful and was causing BMW large financial losses. In 2000, BMW sold off most of the Rover brands, retaining only the Mini brand.

In 1998, BMW also acquired the rights to the Rolls-Royce brand from Vickers Plc.

The 1995 BMW Z3 expanded the line-up to include a mass-production two-seat roadster and the 1999 BMW X5 was the company’s entry into the SUV market.

The first modern mass-produced turbocharged petrol engine was introduced in 2006, (from 1973 to 1975, BMW built 1672 units of a turbocharged M10 engine for the BMW 2002 turbo),[9] with most engines switching over to turbocharging over the 2010s. The first hybrid BMW was the 2010 BMW ActiveHybrid 7, and BMW’s first mass-production electric car was the BMW i3 city car, which was released in 2013, (from 1968 to 1972, BMW built two battery-electric BMW 1602 Elektro saloons for the 1972 Olympic Games).[10] After many years of establishing a reputation for sporting rear-wheel drive cars, BMW’s first front-wheel drive car was the 2014 BMW 2 Series Active Tourer multi-purpose vehicle (MPV).

In January 2021, BMW announced that its sales in 2020 fell by 8.4% due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions. However, in the fourth quarter of 2020, BMW witnessed a rise of 3.2% of its customers’ demands.[11]

On 18 January 2022, BMW announced a new limited edition M760Li xDrive simply called «The Final V12,»[12] the last BMW series production vehicle to be fitted with a V-12 engine.[12]

BMW and Toyota aim to sell jointly-developed hydrogen fuel cell vehicles as soon as 2025.[13][14]

Branding

BMW badge on a 1931 Dixi

Company name

BMW is an abbreviation for Bayerische Motoren Werke (German pronunciation: [ˈbaɪ̯ʁɪʃə mɔˈtʰɔʁn̩ ˈvɛɐ̯kə]). This name is grammatically incorrect (in German, compound words must not contain spaces), which is why the name’s grammatically correct form Bayerische Motorenwerke (German pronunciation: [ˈbaɪ̯ʁɪʃə mɔˈtʰɔʁn̩vɛɐ̯kə] (listen)) has been used in several publications and advertisements in the past.[15][16] Bayerische Motorenwerke translates into English as Bavarian Motor Works.[17] The suffix AG, short for Aktiengesellschaft, signifies an incorporated entity which is owned by shareholders, thus akin to «Inc.» (US) or PLC, «Public Limited Company» (UK).

The terms Beemer, Bimmer and Bee-em are sometimes used as slang for BMW in the English language[18][19] and are sometimes used interchangeably for cars and motorcycles.[20][21][22]

Logo

The circular blue and white BMW logo or roundel evolved from the circular Rapp Motorenwerke company logo, which featured a black ring bearing the company name surrounding the company logo,[23] on a plinth a horse’s head couped.[24]

BMW retained Rapp’s black ring inscribed with the company name, but adopted as the central element a circular escutcheon bearing a quasi-heraldic reference to the coat of arms (and flag) of the Free State of Bavaria (as the state of their origin was named after 1918), being the arms of the House of Wittelsbach, Dukes and Kings of Bavaria.[23] However, as the local law regarding trademarks forbade the use of state coats of arms or other symbols of sovereignty on commercial logos, the design was sufficiently differentiated to comply, but retained the tinctures azure (blue) and argent (white).[23][25][26]

The current iteration of the logo was introduced in 2020,[27] removing 3D effects that had been used in renderings of the logo, and also removing the black outline encircling the rondel. The logo will be used on BMW’s branding but will not be used on vehicles.[28][29]

-

Logo used in vehicles

-

The logo on a BMW car

-

Logo used for publicity purposes since March 2020

The origin of the logo as a portrayal of the movement of an aircraft propeller, the BMW logo with the white blades seeming to cut through a blue sky, is a myth which sprang from a 1929 BMW advertisement depicting the BMW emblem overlaid on a rotating propeller, with the quarters defined by strobe-light effect, a promotion of an aircraft engine then being built by BMW under license from Pratt & Whitney.[23]

For a long time, BMW made little effort to correct the myth that the BMW badge is a propeller

— Fred Jakobs, Archive Director, BMW Group Classic, [23]

It is well established that this propeller portrayal was first used in a BMW advertisement in 1929 – twelve years after the logo was created – so this is not the true origin of the logo.[30]

Slogan

The slogan ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’ was first used in North America in 1974.[31][32] In 2010, this long-lived campaign was mostly supplanted by a campaign intended to make the brand more approachable and to better appeal to women, ‘Joy’. By 2012 BMW had returned to ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’.[33]

Finances

For the fiscal year 2017, BMW reported earnings of EUR 8.620 billion, with an annual revenue of EUR 98.678 billion, an increase of 4.8% over the previous fiscal cycle.[34] BMW’s shares traded at over €77 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at US 55.3 billion in November 2018.[35]

| Year | Revenue in bn. EUR€ |

Net income in bn. EUR€ |

Total Assets in bn. EUR€ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 68.821 | 4.881 | 123.429 | 100,306 |

| 2012 | 76.848 | 5.096 | 131.850 | 105,876 |

| 2013 | 76.058 | 5.314 | 138.368 | 110,351 |

| 2014 | 80.401 | 5.798 | 154.803 | 116,324 |

| 2015 | 92.175 | 6.369 | 172.174 | 122,244 |

| 2016 | 94.163 | 6.863 | 188.535 | 124,729 |

| 2017 | 98.678 | 8.620 | 193.483 | 129,932 |

| 2018 | 97.480 | 7.117 | 208.980 | 134,682 |

| 2019 | 104.210 | 4.915 | 241.663 | 133,778 |

| 2020 | 98.990 | 3.775 | 216.658 | 120,726 |

| 2021 | 111.239 | 12.382 | 229.527 | 118,909 |

Motorcycles

BMW began production of motorcycle engines and then motorcycles after World War I.[36] Its motorcycle brand is now known as BMW Motorrad. Their first successful motorcycle after the failed Helios and Flink, was the «R32» in 1923, though production originally began in 1921.[37] This had a «boxer» twin engine, in which a cylinder projects into the air-flow from each side of the machine. Apart from their single-cylinder models (basically to the same pattern), all their motorcycles used this distinctive layout until the early 1980s. Many BMW’s are still produced in this layout, which is designated the R Series.

The entire BMW Motorcycle production has, since 1969, been located at the company’s Berlin-Spandau factory.

During the Second World War, BMW produced the BMW R75 motorcycle with a motor-driven sidecar attached, combined with a lockable differential, this made the vehicle very capable off-road.[38][39]

In 1982, came the K Series, shaft drive but water-cooled and with either three or four cylinders mounted in a straight line from front to back. Shortly after, BMW also started making the chain-driven F and G series with single and parallel twin Rotax engines.

In the early 1990s, BMW updated the airhead Boxer engine which became known as the oilhead. In 2002, the oilhead engine had two spark plugs per cylinder. In 2004 it added a built-in balance shaft, an increased capacity to 1,170 cc (71 cu in) and enhanced performance to 75 kW (101 hp) for the R1200GS, compared to 63 kW (84 hp) of the previous R1150GS. More powerful variants of the oilhead engines are available in the R1100S and R1200S, producing 73 and 91 kW (98 and 122 hp), respectively.

In 2004, BMW introduced the new K1200S Sports Bike which marked a departure for BMW. It had an engine producing 125 kW (168 hp), derived from the company’s work with the Williams F1 team, and is lighter than previous K models. Innovations include electronically adjustable front and rear suspension, and a Hossack-type front fork that BMW calls Duolever.

BMW introduced anti-lock brakes on production motorcycles starting in the late 1980s. The generation of anti-lock brakes available on the 2006 and later BMW motorcycles paved the way for the introduction of electronic stability control, or anti-skid technology later in the 2007 model year.

BMW has been an innovator in motorcycle suspension design, taking up telescopic front suspension long before most other manufacturers. Then they switched to an Earles fork, front suspension by swinging fork (1955 to 1969). Most modern BMWs are truly rear swingarm, single sided at the back (compare with the regular swinging fork usually, and wrongly, called swinging arm).