Line art drawing of parallel lines and curves.

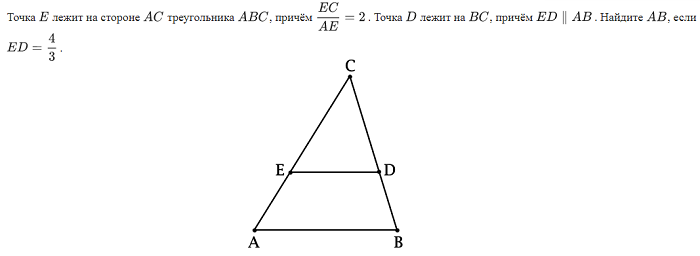

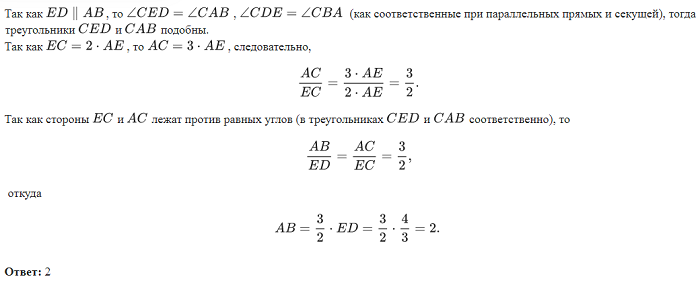

In geometry, parallel lines are coplanar straight lines that do not intersect at any point. Parallel planes are planes in the same three-dimensional space that never meet. Parallel curves are curves that do not touch each other or intersect and keep a fixed minimum distance. In three-dimensional Euclidean space, a line and a plane that do not share a point are also said to be parallel. However, two noncoplanar lines are called skew lines.

Parallel lines are the subject of Euclid’s parallel postulate.[1] Parallelism is primarily a property of affine geometries and Euclidean geometry is a special instance of this type of geometry.

In some other geometries, such as hyperbolic geometry, lines can have analogous properties that are referred to as parallelism.

Symbol[edit]

The parallel symbol is

In the Unicode character set, the «parallel» and «not parallel» signs have codepoints U+2225 (∥) and U+2226 (∦), respectively. In addition, U+22D5 (⋕) represents the relation «equal and parallel to».[4]

The same symbol is used for a binary function in electrical engineering (the parallel operator). It is distinct from the double-vertical-line brackets that indicate a norm (e.g.

||) in several programming languages.

Euclidean parallelism[edit]

Two lines in a plane[edit]

Conditions for parallelism[edit]

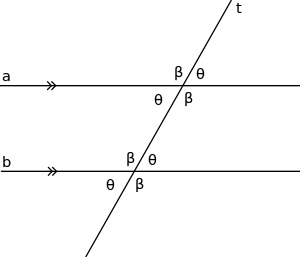

As shown by the tick marks, lines a and b are parallel. This can be proved because the transversal t produces congruent corresponding angles

Given parallel straight lines l and m in Euclidean space, the following properties are equivalent:

- Every point on line m is located at exactly the same (minimum) distance from line l (equidistant lines).

- Line m is in the same plane as line l but does not intersect l (recall that lines extend to infinity in either direction).

- When lines m and l are both intersected by a third straight line (a transversal) in the same plane, the corresponding angles of intersection with the transversal are congruent.

Since these are equivalent properties, any one of them could be taken as the definition of parallel lines in Euclidean space, but the first and third properties involve measurement, and so, are «more complicated» than the second. Thus, the second property is the one usually chosen as the defining property of parallel lines in Euclidean geometry.[5] The other properties are then consequences of Euclid’s Parallel Postulate. Another property that also involves measurement is that lines parallel to each other have the same gradient (slope).

History[edit]

The definition of parallel lines as a pair of straight lines in a plane which do not meet appears as Definition 23 in Book I of Euclid’s Elements.[6] Alternative definitions were discussed by other Greeks, often as part of an attempt to prove the parallel postulate. Proclus attributes a definition of parallel lines as equidistant lines to Posidonius and quotes Geminus in a similar vein. Simplicius also mentions Posidonius’ definition as well as its modification by the philosopher Aganis.[6]

At the end of the nineteenth century, in England, Euclid’s Elements was still the standard textbook in secondary schools. The traditional treatment of geometry was being pressured to change by the new developments in projective geometry and non-Euclidean geometry, so several new textbooks for the teaching of geometry were written at this time. A major difference between these reform texts, both between themselves and between them and Euclid, is the treatment of parallel lines.[7] These reform texts were not without their critics and one of them, Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll), wrote a play, Euclid and His Modern Rivals, in which these texts are lambasted.[8]

One of the early reform textbooks was James Maurice Wilson’s Elementary Geometry of 1868.[9] Wilson based his definition of parallel lines on the primitive notion of direction. According to Wilhelm Killing[10] the idea may be traced back to Leibniz.[11] Wilson, without defining direction since it is a primitive, uses the term in other definitions such as his sixth definition, «Two straight lines that meet one another have different directions, and the difference of their directions is the angle between them.» Wilson (1868, p. 2) In definition 15 he introduces parallel lines in this way; «Straight lines which have the same direction, but are not parts of the same straight line, are called parallel lines.» Wilson (1868, p. 12) Augustus De Morgan reviewed this text and declared it a failure, primarily on the basis of this definition and the way Wilson used it to prove things about parallel lines. Dodgson also devotes a large section of his play (Act II, Scene VI § 1) to denouncing Wilson’s treatment of parallels. Wilson edited this concept out of the third and higher editions of his text.[12]

Other properties, proposed by other reformers, used as replacements for the definition of parallel lines, did not fare much better. The main difficulty, as pointed out by Dodgson, was that to use them in this way required additional axioms to be added to the system. The equidistant line definition of Posidonius, expounded by Francis Cuthbertson in his 1874 text Euclidean Geometry suffers from the problem that the points that are found at a fixed given distance on one side of a straight line must be shown to form a straight line. This can not be proved and must be assumed to be true.[13] The corresponding angles formed by a transversal property, used by W. D. Cooley in his 1860 text, The Elements of Geometry, simplified and explained requires a proof of the fact that if one transversal meets a pair of lines in congruent corresponding angles then all transversals must do so. Again, a new axiom is needed to justify this statement.

Construction[edit]

The three properties above lead to three different methods of construction[14] of parallel lines.

The problem: Draw a line through a parallel to l.

-

Property 1: Line m has everywhere the same distance to line l.

-

Property 2: Take a random line through a that intersects l in x. Move point x to infinity.

-

Property 3: Both l and m share a transversal line through a that intersect them at 90°.

Distance between two parallel lines[edit]

Because parallel lines in a Euclidean plane are equidistant there is a unique distance between the two parallel lines. Given the equations of two non-vertical, non-horizontal parallel lines,

the distance between the two lines can be found by locating two points (one on each line) that lie on a common perpendicular to the parallel lines and calculating the distance between them. Since the lines have slope m, a common perpendicular would have slope −1/m and we can take the line with equation y = −x/m as a common perpendicular. Solve the linear systems

and

to get the coordinates of the points. The solutions to the linear systems are the points

and

These formulas still give the correct point coordinates even if the parallel lines are horizontal (i.e., m = 0). The distance between the points is

which reduces to

When the lines are given by the general form of the equation of a line (horizontal and vertical lines are included):

their distance can be expressed as

Two lines in three-dimensional space[edit]

Two lines in the same three-dimensional space that do not intersect need not be parallel. Only if they are in a common plane are they called parallel; otherwise they are called skew lines.

Two distinct lines l and m in three-dimensional space are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P on line m to the nearest point on line l is independent of the location of P on line m. This never holds for skew lines.

A line and a plane[edit]

A line m and a plane q in three-dimensional space, the line not lying in that plane, are parallel if and only if they do not intersect.

Equivalently, they are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P on line m to the nearest point in plane q is independent of the location of P on line m.

Two planes[edit]

Similar to the fact that parallel lines must be located in the same plane, parallel planes must be situated in the same three-dimensional space and contain no point in common.

Two distinct planes q and r are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P in plane q to the nearest point in plane r is independent of the location of P in plane q. This will never hold if the two planes are not in the same three-dimensional space.

Extension to non-Euclidean geometry[edit]

In non-Euclidean geometry, it is more common to talk about geodesics than (straight) lines. A geodesic is the shortest path between two points in a given geometry. In physics this may be interpreted as the path that a particle follows if no force is applied to it. In non-Euclidean geometry (elliptic or hyperbolic geometry) the three Euclidean properties mentioned above are not equivalent and only the second one (Line m is in the same plane as line l but does not intersect l) is useful in non-Euclidean geometries, since it involves no measurements. In general geometry the three properties above give three different types of curves, equidistant curves, parallel geodesics and geodesics sharing a common perpendicular, respectively.

Hyperbolic geometry[edit]

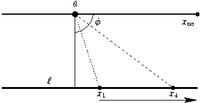

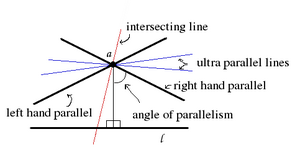

Intersecting, parallel and ultra parallel lines through a with respect to l in the hyperbolic plane. The parallel lines appear to intersect l just off the image. This is just an artifact of the visualisation. On a real hyperbolic plane the lines will get closer to each other and ‘meet’ in infinity.

While in Euclidean geometry two geodesics can either intersect or be parallel, in hyperbolic geometry, there are three possibilities. Two geodesics belonging to the same plane can either be:

- intersecting, if they intersect in a common point in the plane,

- parallel, if they do not intersect in the plane, but converge to a common limit point at infinity (ideal point), or

- ultra parallel, if they do not have a common limit point at infinity.

In the literature ultra parallel geodesics are often called non-intersecting. Geodesics intersecting at infinity are called limiting parallel.

As in the illustration through a point a not on line l there are two limiting parallel lines, one for each direction ideal point of line l. They separate the lines intersecting line l and those that are ultra parallel to line l.

Ultra parallel lines have single common perpendicular (ultraparallel theorem), and diverge on both sides of this common perpendicular.

Spherical or elliptic geometry[edit]

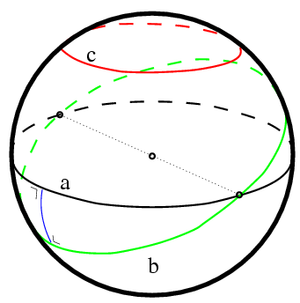

On the sphere there is no such thing as a parallel line. Line a is a great circle, the equivalent of a straight line in spherical geometry. Line c is equidistant to line a but is not a great circle. It is a parallel of latitude. Line b is another geodesic which intersects a in two antipodal points. They share two common perpendiculars (one shown in blue).

In spherical geometry, all geodesics are great circles. Great circles divide the sphere in two equal hemispheres and all great circles intersect each other. Thus, there are no parallel geodesics to a given geodesic, as all geodesics intersect. Equidistant curves on the sphere are called parallels of latitude analogous to the latitude lines on a globe. Parallels of latitude can be generated by the intersection of the sphere with a plane parallel to a plane through the center of the sphere.

Reflexive variant[edit]

If l, m, n are three distinct lines, then

In this case, parallelism is a transitive relation. However, in case l = n, the superimposed lines are not considered parallel in Euclidean geometry. The binary relation between parallel lines is evidently a symmetric relation. According to Euclid’s tenets, parallelism is not a reflexive relation and thus fails to be an equivalence relation. Nevertheless, in affine geometry a pencil of parallel lines is taken as an equivalence class in the set of lines where parallelism is an equivalence relation.[15][16][17]

To this end, Emil Artin (1957) adopted a definition of parallelism where two lines are parallel if they have all or none of their points in common.[18]

Then a line is parallel to itself so that the reflexive and transitive properties belong to this type of parallelism, creating an equivalence relation on the set of lines. In the study of incidence geometry, this variant of parallelism is used in the affine plane.

See also[edit]

- Clifford parallel

- Collinearity

- Concurrent lines

- Limiting parallel

- Parallel curve

- Ultraparallel theorem

Notes[edit]

- ^ Although this postulate only refers to when lines meet, it is needed to prove the uniqueness of parallel lines in the sense of Playfair’s axiom.

- ^ Kersey (the elder), John (1673). Algebra. Vol. Book IV. London. p. 177.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1993) [September 1928]. «§ 184, § 359, § 368». A History of Mathematical Notations — Notations in Elementary Mathematics. Vol. 1 (two volumes in one unaltered reprint ed.). Chicago, US: Open court publishing company. pp. 193, 402–403, 411–412. ISBN 0-486-67766-4. LCCN 93-29211. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

§359. […] ∥ for parallel occurs in Oughtred’s Opuscula mathematica hactenus inedita (1677) [p. 197], a posthumous work (§ 184) […] §368. Signs for parallel lines. […] when Recorde’s sign of equality won its way upon the Continent, vertical lines came to be used for parallelism. We find ∥ for «parallel» in Kersey,[14] Caswell, Jones,[15] Wilson,[16] Emerson,[17] Kambly,[18] and the writers of the last fifty years who have been already quoted in connection with other pictographs. Before about 1875 it does not occur as often […] Hall and Stevens[1] use «par[1] or ∥» for parallel […] [14] John Kersey, Algebra (London, 1673), Book IV, p. 177. [15] W. Jones, Synopsis palmarioum matheseos (London, 1706). [16] John Wilson, Trigonometry (Edinburgh, 1714), characters explained. [17] W. Emerson, Elements of Geometry (London, 1763), p. 4. [18] L. Kambly [de], Die Elementar-Mathematik, Part 2: Planimetrie, 43. edition (Breslau, 1876), p. 8. […] [1] H. S. Hall and F. H. Stevens, Euclid’s Elements, Parts I and II (London, 1889), p. 10. […]

[1] - ^ «Mathematical Operators – Unicode Consortium» (PDF). Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ Wylie 1964, pp. 92—94

- ^ a b Heath 1956, pp. 190–194

- ^ Richards 1988, Chap. 4: Euclid and the English Schoolchild. pp. 161–200

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (2009) [1879], Euclid and His Modern Rivals, Barnes & Noble, ISBN 978-1-4351-2348-9

- ^ Wilson 1868

- ^ Einführung in die Grundlagen der Geometrie, I, p. 5

- ^ Heath 1956, p. 194

- ^ Richards 1988, pp. 180–184

- ^ Heath 1956, p. 194

- ^ Only the third is a straightedge and compass construction, the first two are infinitary processes (they require an «infinite number of steps».)

- ^ H. S. M. Coxeter (1961) Introduction to Geometry, p 192, John Wiley & Sons

- ^ Wanda Szmielew (1983) From Affine to Euclidean Geometry, p 17, D. Reidel ISBN 90-277-1243-3

- ^ Andy Liu (2011) «Is parallelism an equivalence relation?», The College Mathematics Journal 42(5):372

- ^ Emil Artin (1957) Geometric Algebra, page 52 via Internet Archive

References[edit]

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956), The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.), New York: Dover Publications

- (3 vols.): ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3). Heath’s authoritative translation plus extensive historical research and detailed commentary throughout the text.

- Richards, Joan L. (1988), Mathematical Visions: The Pursuit of Geometry in Victorian England, Boston: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-587445-6

- Wilson, James Maurice (1868), Elementary Geometry (1st ed.), London: Macmillan and Co.

- Wylie, C. R. Jr. (1964), Foundations of Geometry, McGraw–Hill

Further reading[edit]

- Papadopoulos, Athanase; Théret, Guillaume (2014), La théorie des parallèles de Johann Heinrich Lambert : Présentation, traduction et commentaires, Paris: Collection Sciences dans l’histoire, Librairie Albert Blanchard, ISBN 978-2-85367-266-5

External links[edit]

Line art drawing of parallel lines and curves.

In geometry, parallel lines are coplanar straight lines that do not intersect at any point. Parallel planes are planes in the same three-dimensional space that never meet. Parallel curves are curves that do not touch each other or intersect and keep a fixed minimum distance. In three-dimensional Euclidean space, a line and a plane that do not share a point are also said to be parallel. However, two noncoplanar lines are called skew lines.

Parallel lines are the subject of Euclid’s parallel postulate.[1] Parallelism is primarily a property of affine geometries and Euclidean geometry is a special instance of this type of geometry.

In some other geometries, such as hyperbolic geometry, lines can have analogous properties that are referred to as parallelism.

Symbol[edit]

The parallel symbol is

In the Unicode character set, the «parallel» and «not parallel» signs have codepoints U+2225 (∥) and U+2226 (∦), respectively. In addition, U+22D5 (⋕) represents the relation «equal and parallel to».[4]

The same symbol is used for a binary function in electrical engineering (the parallel operator). It is distinct from the double-vertical-line brackets that indicate a norm (e.g.

||) in several programming languages.

Euclidean parallelism[edit]

Two lines in a plane[edit]

Conditions for parallelism[edit]

As shown by the tick marks, lines a and b are parallel. This can be proved because the transversal t produces congruent corresponding angles

Given parallel straight lines l and m in Euclidean space, the following properties are equivalent:

- Every point on line m is located at exactly the same (minimum) distance from line l (equidistant lines).

- Line m is in the same plane as line l but does not intersect l (recall that lines extend to infinity in either direction).

- When lines m and l are both intersected by a third straight line (a transversal) in the same plane, the corresponding angles of intersection with the transversal are congruent.

Since these are equivalent properties, any one of them could be taken as the definition of parallel lines in Euclidean space, but the first and third properties involve measurement, and so, are «more complicated» than the second. Thus, the second property is the one usually chosen as the defining property of parallel lines in Euclidean geometry.[5] The other properties are then consequences of Euclid’s Parallel Postulate. Another property that also involves measurement is that lines parallel to each other have the same gradient (slope).

History[edit]

The definition of parallel lines as a pair of straight lines in a plane which do not meet appears as Definition 23 in Book I of Euclid’s Elements.[6] Alternative definitions were discussed by other Greeks, often as part of an attempt to prove the parallel postulate. Proclus attributes a definition of parallel lines as equidistant lines to Posidonius and quotes Geminus in a similar vein. Simplicius also mentions Posidonius’ definition as well as its modification by the philosopher Aganis.[6]

At the end of the nineteenth century, in England, Euclid’s Elements was still the standard textbook in secondary schools. The traditional treatment of geometry was being pressured to change by the new developments in projective geometry and non-Euclidean geometry, so several new textbooks for the teaching of geometry were written at this time. A major difference between these reform texts, both between themselves and between them and Euclid, is the treatment of parallel lines.[7] These reform texts were not without their critics and one of them, Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll), wrote a play, Euclid and His Modern Rivals, in which these texts are lambasted.[8]

One of the early reform textbooks was James Maurice Wilson’s Elementary Geometry of 1868.[9] Wilson based his definition of parallel lines on the primitive notion of direction. According to Wilhelm Killing[10] the idea may be traced back to Leibniz.[11] Wilson, without defining direction since it is a primitive, uses the term in other definitions such as his sixth definition, «Two straight lines that meet one another have different directions, and the difference of their directions is the angle between them.» Wilson (1868, p. 2) In definition 15 he introduces parallel lines in this way; «Straight lines which have the same direction, but are not parts of the same straight line, are called parallel lines.» Wilson (1868, p. 12) Augustus De Morgan reviewed this text and declared it a failure, primarily on the basis of this definition and the way Wilson used it to prove things about parallel lines. Dodgson also devotes a large section of his play (Act II, Scene VI § 1) to denouncing Wilson’s treatment of parallels. Wilson edited this concept out of the third and higher editions of his text.[12]

Other properties, proposed by other reformers, used as replacements for the definition of parallel lines, did not fare much better. The main difficulty, as pointed out by Dodgson, was that to use them in this way required additional axioms to be added to the system. The equidistant line definition of Posidonius, expounded by Francis Cuthbertson in his 1874 text Euclidean Geometry suffers from the problem that the points that are found at a fixed given distance on one side of a straight line must be shown to form a straight line. This can not be proved and must be assumed to be true.[13] The corresponding angles formed by a transversal property, used by W. D. Cooley in his 1860 text, The Elements of Geometry, simplified and explained requires a proof of the fact that if one transversal meets a pair of lines in congruent corresponding angles then all transversals must do so. Again, a new axiom is needed to justify this statement.

Construction[edit]

The three properties above lead to three different methods of construction[14] of parallel lines.

The problem: Draw a line through a parallel to l.

-

Property 1: Line m has everywhere the same distance to line l.

-

Property 2: Take a random line through a that intersects l in x. Move point x to infinity.

-

Property 3: Both l and m share a transversal line through a that intersect them at 90°.

Distance between two parallel lines[edit]

Because parallel lines in a Euclidean plane are equidistant there is a unique distance between the two parallel lines. Given the equations of two non-vertical, non-horizontal parallel lines,

the distance between the two lines can be found by locating two points (one on each line) that lie on a common perpendicular to the parallel lines and calculating the distance between them. Since the lines have slope m, a common perpendicular would have slope −1/m and we can take the line with equation y = −x/m as a common perpendicular. Solve the linear systems

and

to get the coordinates of the points. The solutions to the linear systems are the points

and

These formulas still give the correct point coordinates even if the parallel lines are horizontal (i.e., m = 0). The distance between the points is

which reduces to

When the lines are given by the general form of the equation of a line (horizontal and vertical lines are included):

their distance can be expressed as

Two lines in three-dimensional space[edit]

Two lines in the same three-dimensional space that do not intersect need not be parallel. Only if they are in a common plane are they called parallel; otherwise they are called skew lines.

Two distinct lines l and m in three-dimensional space are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P on line m to the nearest point on line l is independent of the location of P on line m. This never holds for skew lines.

A line and a plane[edit]

A line m and a plane q in three-dimensional space, the line not lying in that plane, are parallel if and only if they do not intersect.

Equivalently, they are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P on line m to the nearest point in plane q is independent of the location of P on line m.

Two planes[edit]

Similar to the fact that parallel lines must be located in the same plane, parallel planes must be situated in the same three-dimensional space and contain no point in common.

Two distinct planes q and r are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P in plane q to the nearest point in plane r is independent of the location of P in plane q. This will never hold if the two planes are not in the same three-dimensional space.

Extension to non-Euclidean geometry[edit]

In non-Euclidean geometry, it is more common to talk about geodesics than (straight) lines. A geodesic is the shortest path between two points in a given geometry. In physics this may be interpreted as the path that a particle follows if no force is applied to it. In non-Euclidean geometry (elliptic or hyperbolic geometry) the three Euclidean properties mentioned above are not equivalent and only the second one (Line m is in the same plane as line l but does not intersect l) is useful in non-Euclidean geometries, since it involves no measurements. In general geometry the three properties above give three different types of curves, equidistant curves, parallel geodesics and geodesics sharing a common perpendicular, respectively.

Hyperbolic geometry[edit]

Intersecting, parallel and ultra parallel lines through a with respect to l in the hyperbolic plane. The parallel lines appear to intersect l just off the image. This is just an artifact of the visualisation. On a real hyperbolic plane the lines will get closer to each other and ‘meet’ in infinity.

While in Euclidean geometry two geodesics can either intersect or be parallel, in hyperbolic geometry, there are three possibilities. Two geodesics belonging to the same plane can either be:

- intersecting, if they intersect in a common point in the plane,

- parallel, if they do not intersect in the plane, but converge to a common limit point at infinity (ideal point), or

- ultra parallel, if they do not have a common limit point at infinity.

In the literature ultra parallel geodesics are often called non-intersecting. Geodesics intersecting at infinity are called limiting parallel.

As in the illustration through a point a not on line l there are two limiting parallel lines, one for each direction ideal point of line l. They separate the lines intersecting line l and those that are ultra parallel to line l.

Ultra parallel lines have single common perpendicular (ultraparallel theorem), and diverge on both sides of this common perpendicular.

Spherical or elliptic geometry[edit]

On the sphere there is no such thing as a parallel line. Line a is a great circle, the equivalent of a straight line in spherical geometry. Line c is equidistant to line a but is not a great circle. It is a parallel of latitude. Line b is another geodesic which intersects a in two antipodal points. They share two common perpendiculars (one shown in blue).

In spherical geometry, all geodesics are great circles. Great circles divide the sphere in two equal hemispheres and all great circles intersect each other. Thus, there are no parallel geodesics to a given geodesic, as all geodesics intersect. Equidistant curves on the sphere are called parallels of latitude analogous to the latitude lines on a globe. Parallels of latitude can be generated by the intersection of the sphere with a plane parallel to a plane through the center of the sphere.

Reflexive variant[edit]

If l, m, n are three distinct lines, then

In this case, parallelism is a transitive relation. However, in case l = n, the superimposed lines are not considered parallel in Euclidean geometry. The binary relation between parallel lines is evidently a symmetric relation. According to Euclid’s tenets, parallelism is not a reflexive relation and thus fails to be an equivalence relation. Nevertheless, in affine geometry a pencil of parallel lines is taken as an equivalence class in the set of lines where parallelism is an equivalence relation.[15][16][17]

To this end, Emil Artin (1957) adopted a definition of parallelism where two lines are parallel if they have all or none of their points in common.[18]

Then a line is parallel to itself so that the reflexive and transitive properties belong to this type of parallelism, creating an equivalence relation on the set of lines. In the study of incidence geometry, this variant of parallelism is used in the affine plane.

See also[edit]

- Clifford parallel

- Collinearity

- Concurrent lines

- Limiting parallel

- Parallel curve

- Ultraparallel theorem

Notes[edit]

- ^ Although this postulate only refers to when lines meet, it is needed to prove the uniqueness of parallel lines in the sense of Playfair’s axiom.

- ^ Kersey (the elder), John (1673). Algebra. Vol. Book IV. London. p. 177.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1993) [September 1928]. «§ 184, § 359, § 368». A History of Mathematical Notations — Notations in Elementary Mathematics. Vol. 1 (two volumes in one unaltered reprint ed.). Chicago, US: Open court publishing company. pp. 193, 402–403, 411–412. ISBN 0-486-67766-4. LCCN 93-29211. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

§359. […] ∥ for parallel occurs in Oughtred’s Opuscula mathematica hactenus inedita (1677) [p. 197], a posthumous work (§ 184) […] §368. Signs for parallel lines. […] when Recorde’s sign of equality won its way upon the Continent, vertical lines came to be used for parallelism. We find ∥ for «parallel» in Kersey,[14] Caswell, Jones,[15] Wilson,[16] Emerson,[17] Kambly,[18] and the writers of the last fifty years who have been already quoted in connection with other pictographs. Before about 1875 it does not occur as often […] Hall and Stevens[1] use «par[1] or ∥» for parallel […] [14] John Kersey, Algebra (London, 1673), Book IV, p. 177. [15] W. Jones, Synopsis palmarioum matheseos (London, 1706). [16] John Wilson, Trigonometry (Edinburgh, 1714), characters explained. [17] W. Emerson, Elements of Geometry (London, 1763), p. 4. [18] L. Kambly [de], Die Elementar-Mathematik, Part 2: Planimetrie, 43. edition (Breslau, 1876), p. 8. […] [1] H. S. Hall and F. H. Stevens, Euclid’s Elements, Parts I and II (London, 1889), p. 10. […]

[1] - ^ «Mathematical Operators – Unicode Consortium» (PDF). Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ Wylie 1964, pp. 92—94

- ^ a b Heath 1956, pp. 190–194

- ^ Richards 1988, Chap. 4: Euclid and the English Schoolchild. pp. 161–200

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (2009) [1879], Euclid and His Modern Rivals, Barnes & Noble, ISBN 978-1-4351-2348-9

- ^ Wilson 1868

- ^ Einführung in die Grundlagen der Geometrie, I, p. 5

- ^ Heath 1956, p. 194

- ^ Richards 1988, pp. 180–184

- ^ Heath 1956, p. 194

- ^ Only the third is a straightedge and compass construction, the first two are infinitary processes (they require an «infinite number of steps».)

- ^ H. S. M. Coxeter (1961) Introduction to Geometry, p 192, John Wiley & Sons

- ^ Wanda Szmielew (1983) From Affine to Euclidean Geometry, p 17, D. Reidel ISBN 90-277-1243-3

- ^ Andy Liu (2011) «Is parallelism an equivalence relation?», The College Mathematics Journal 42(5):372

- ^ Emil Artin (1957) Geometric Algebra, page 52 via Internet Archive

References[edit]

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956), The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.), New York: Dover Publications

- (3 vols.): ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3). Heath’s authoritative translation plus extensive historical research and detailed commentary throughout the text.

- Richards, Joan L. (1988), Mathematical Visions: The Pursuit of Geometry in Victorian England, Boston: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-587445-6

- Wilson, James Maurice (1868), Elementary Geometry (1st ed.), London: Macmillan and Co.

- Wylie, C. R. Jr. (1964), Foundations of Geometry, McGraw–Hill

Further reading[edit]

- Papadopoulos, Athanase; Théret, Guillaume (2014), La théorie des parallèles de Johann Heinrich Lambert : Présentation, traduction et commentaires, Paris: Collection Sciences dans l’histoire, Librairie Albert Blanchard, ISBN 978-2-85367-266-5

External links[edit]

∥ Параллельно

Нажмите, чтобы скопировать и вставить символ

Значение символа

Параллельно. Математические операторы.

Символ «Параллельно» был утвержден как часть Юникода версии 1.1 в 1993 г.

Свойства

| Версия | 1.1 |

| Блок | Математические операторы |

| Тип парной зеркальной скобки (bidi) | Нет |

| Композиционное исключение | Нет |

| Изменение регистра | 2225 |

| Простое изменение регистра | 2225 |

Кодировка

| Кодировка | hex | dec (bytes) | dec | binary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTF-8 | E2 88 A5 | 226 136 165 | 14846117 | 11100010 10001000 10100101 |

| UTF-16BE | 22 25 | 34 37 | 8741 | 00100010 00100101 |

| UTF-16LE | 25 22 | 37 34 | 9506 | 00100101 00100010 |

| UTF-32BE | 00 00 22 25 | 0 0 34 37 | 8741 | 00000000 00000000 00100010 00100101 |

| UTF-32LE | 25 22 00 00 | 37 34 0 0 | 622985216 | 00100101 00100010 00000000 00000000 |

Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

Когда и кем была введена знак параллельности II

В евклидовой геометрии

Параллельными (иногда — равнобежными) прямыми называются прямые, которые лежат в одной плоскости и либо совпадают, либо не пересекаются. В некоторых школьных определениях совпадающие прямые не считаются параллельными, здесь такое определение не рассматривается.

[править] Свойства

1. Параллельность — бинарное отношение эквивалентности, поэтому разбивает всё множество прямых на классы параллельных между собой прямых.

2. Через любую точку можно провести ровно одну прямую, параллельную данной. Это отличительное свойство евклидовой геометрии, в других геометриях число 1 заменено другими (в геометрии Лобачевского таких прямых минимум две)

3. 2 параллельные прямые в пространстве лежат в одной плоскости.

4. При пересечении 2 параллельных прямых третьей, называемой секущей:

1. Секущая обязательно пересекает обе прямые.

2. При пересечении образуется 8 углов, некоторые характерные пары которых имеют особые названия и свойства:

1. Накрест лежащие углы равны.

2. Соответственные углы равны.

3. Односторонние углы в сумме составляют 180°.

[править] В геометрии Лобачевского

Параллельные прямые в модели Пуанкаре: две зелёные прямые параллельны синей прямой, а фиолетовая ультрапараллельна к ней

В геометрии Лобачевского в плоскости через точку C вне данной прямой AB проходит бесконечное множество прямых, не пересекающих AB. Из них параллельными к AB называются только две. Прямая CE называется равнобежной (параллельной) прямой AB в направлении от A к B, если:

Источник

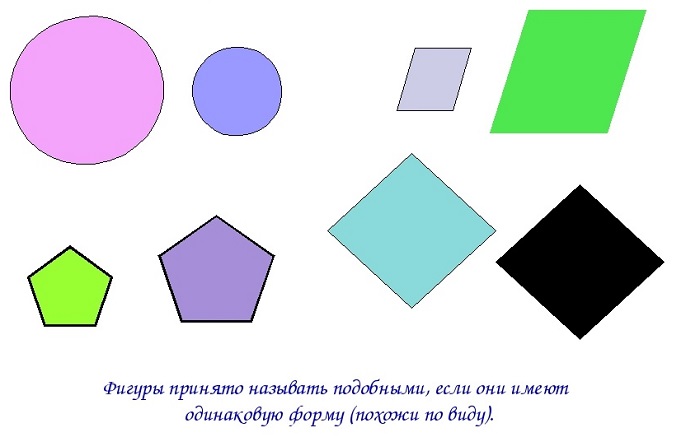

В учебниках по геометрии часто встречаются задачи на подобие фигур. Какой знак используется для обозначения подобия фигур? Какие фигуры называются подобными? Поговорим обо всем этом в нашей статье.

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

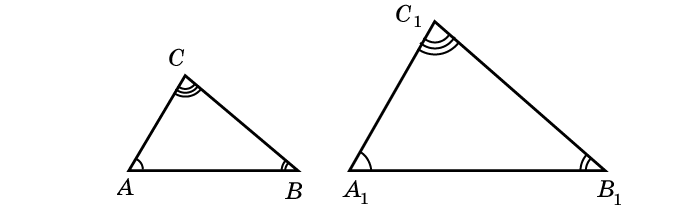

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

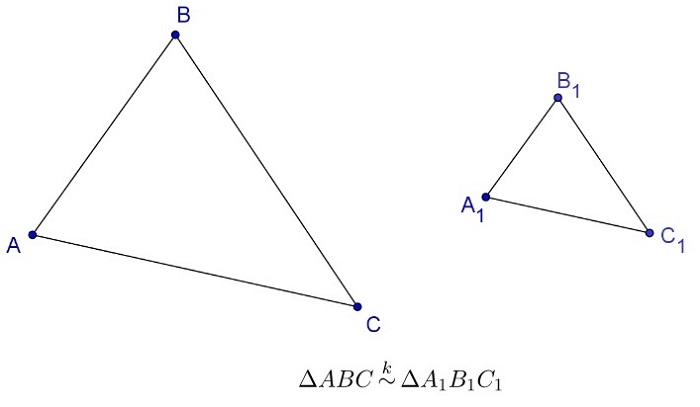

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком

обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

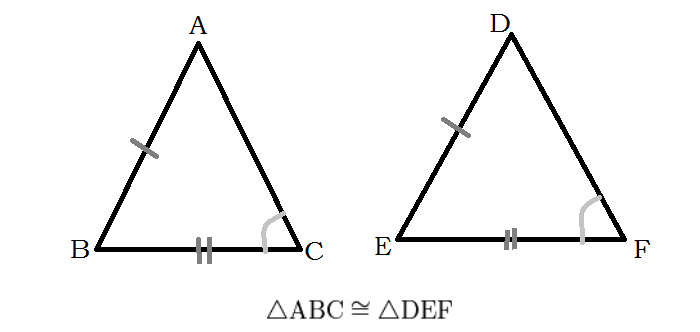

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

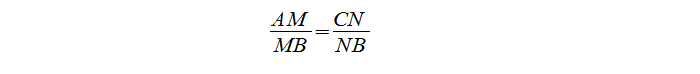

Признаки подобия прямоугольных треугольников

Острые углы: наличие равного острого угла в прямоугольных треугольниках делает их подобными.

Два катета: общая пропорциональность катетам одного прямоугольного треугольника к катетам второго делает их подобными.

Катет и гипотенуза: пропорциональность катета и гипотенузы одного прямоугольного треугольника к катету и гипотенузе второго прямоугольного треугольника делает их подобными.

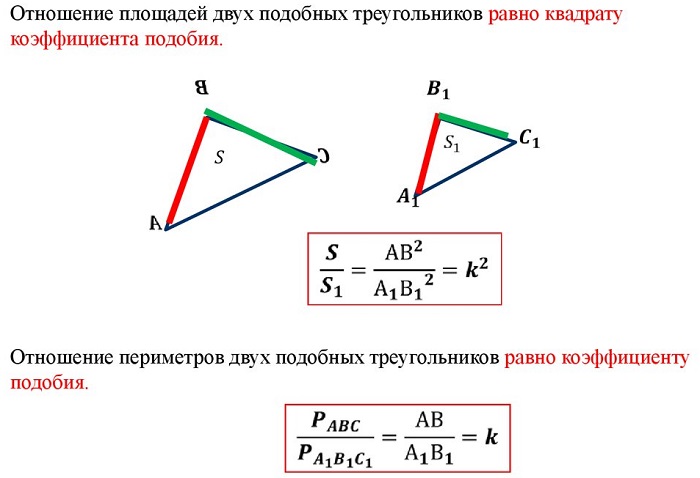

треугольник ∆ABC и треугольник ∆A1B1C1 считаются подобными при равнозначности углов и пропорциональности сторон;

отношение площадей подобных треугольников равно квадрату коэффициента подобия.

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

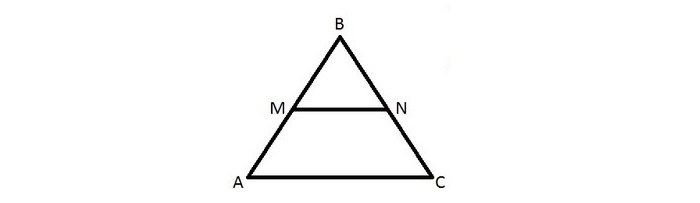

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN

∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Примеры решения задач по геометрии на тему «Подобие треугольников»

Источник

В учебниках по геометрии часто встречаются задачи на подобие фигур. Какой знак используется для обозначения подобия фигур? Какие фигуры называются подобными? Поговорим обо всем этом в нашей статье.

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком

обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

Признаки подобия прямоугольных треугольников

Острые углы: наличие равного острого угла в прямоугольных треугольниках делает их подобными.

Два катета: общая пропорциональность катетам одного прямоугольного треугольника к катетам второго делает их подобными.

Катет и гипотенуза: пропорциональность катета и гипотенузы одного прямоугольного треугольника к катету и гипотенузе второго прямоугольного треугольника делает их подобными.

треугольник ∆ABC и треугольник ∆A1B1C1 считаются подобными при равнозначности углов и пропорциональности сторон;

отношение площадей подобных треугольников равно квадрату коэффициента подобия.

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN

∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Примеры решения задач по геометрии на тему «Подобие треугольников»

Источник

Обозначения и символика

Для обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между ними, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем в курсе используется геометрический язык, составленный из обозначений и символов, принятых в курсе математики (в частности, в новом курсе геометрии в средней школе).

Все многообразие обозначений и символов, а также связи между ними могут быть подразделены на две группы:

группа I — обозначения геометрических фигур и отношений между ними;

группа II обозначения логических операций, составляющие синтаксическую основу геометрического языка.

Ниже приводится полный список математических символов, используемых в данном курсе. Особое внимание уделяется символам, которые применяются для обозначения проекций геометрических фигур.

СИМВОЛЫ, ОБОЗНАЧАЮЩИЕ ГЕОМЕТРИЧЕСКИЕ ФИГУРЫ И ОТНОШЕНИЯ МЕЖДУ НИМИ

А. Обозначение геометрических фигур

1. Геометрическая фигура обозначается — Ф.

2. Точки обозначаются прописными буквами латинского алфавита или арабскими цифрами:

3. Линии, произвольно расположенные по отношению к плоскостям проекций, обозначаются строчными буквами латинского алфавита:

Линии уровня обозначаются: h — горизонталь; f— фронталь.

Для прямых используются также следующие обозначения:

(АВ) — прямая, проходящая через точки А а В;

[АВ) — луч с началом в точке А;

[АВ] — отрезок прямой, ограниченный точками А и В.

4. Поверхности обозначаются строчными буквами греческого алфавита:

Чтобы подчеркнуть способ задания поверхности, следует указывать геометрические элементы, которыми она определяется, например:

α(а || b) — плоскость α определяется параллельными прямыми а и b;

5. Углы обозначаются:

6. Угловая: величина (градусная мера) обозначается знаком

Прямой угол отмечается квадратом с точкой внутри

7. Расстояния между геометрическими фигурами обозначаются двумя вертикальными отрезками — ||.

|АВ| — расстояние между точками А и В (длина отрезка АВ);

|Аа| — расстояние от точки А до линии a;

|Аα| — расстояшие от точки А до поверхности α;

|аb| — расстояние между линиями а и b;

|αβ| расстояние между поверхностями α и β.

π2 —фрюнтальная плоскость проекций.

При замене плоскостей проекций или введении новых плоскостей последние обозначают π3, π4 и т. д.

Постояшную прямую эпюра Монжа обозначают k.

10. Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей, любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса, соответствующего плоскости проекции, на которой они получены:

11. Следы плоскостей (поверхностей) обозначаются теми же буквами, что и горизонталь или фронталь, с добавлением подстрочного индекса 0α, подчеркивающего, что эти линии лежат в плоскости проекции и принадлежат плоскости (поверхности) α.

12. Следы прямых (линий) обозначаются заглавными буквами, с которых начинаются слова, определяющие название (в латинской транскрипции) плоскости проекции, которую пересекает линия, с подстрочным индексом, указывающим принадлежность к линии.

Например: Ha — горизонтальный след прямой (линии) а;

Fa — фронтальный след прямой (линии ) a.

13. Последовательность точек, линий (любой фигуры) отмечается подстрочными индексами 1,2,3. n:

Вспомогательная проекция точки, полученная в результате преобразования для получения действительной величины геометрической фигуры, обозначается той же буквой с подстрочным индексом 0:

14. Аксонометрические проекции точек, линий, поверхностей обозначаются теми же буквами, что и натура с добавлением верхнего индекса 0 :

15. Вторичные проекции обозначаются путем добавления верхнего индекса 1 :

Для облегчения чтения чертежей в учебнике при оформлении иллюстративного материала использованы несколько цветов, каждый из которых имеет определенное смысловое значение: линиями (точками) черного цвета обозначены исходные данные; зеленый цвет использован для линий вспомогательных графических построений; красными линиями (точками) показаны результаты построений или те геометрические элементы, на которые следует обратить особое внимание.

Источник

Обозначения и символика

Для обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между ними, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем в курсе используется геометрический язык, составленный из обозначений и символов, принятых в курсе математики (в частности, в новом курсе геометрии в средней школе).

Все многообразие обозначений и символов, а также связи между ними могут быть подразделены на две группы:

группа I — обозначения геометрических фигур и отношений между ними;

группа II обозначения логических операций, составляющие синтаксическую основу геометрического языка.

Ниже приводится полный список математических символов, используемых в данном курсе. Особое внимание уделяется символам, которые применяются для обозначения проекций геометрических фигур.

СИМВОЛЫ, ОБОЗНАЧАЮЩИЕ ГЕОМЕТРИЧЕСКИЕ ФИГУРЫ И ОТНОШЕНИЯ МЕЖДУ НИМИ

А. Обозначение геометрических фигур

1. Геометрическая фигура обозначается — Ф.

2. Точки обозначаются прописными буквами латинского алфавита или арабскими цифрами:

3. Линии, произвольно расположенные по отношению к плоскостям проекций, обозначаются строчными буквами латинского алфавита:

Линии уровня обозначаются: h — горизонталь; f— фронталь.

Для прямых используются также следующие обозначения:

(АВ) — прямая, проходящая через точки А а В;

[АВ) — луч с началом в точке А;

[АВ] — отрезок прямой, ограниченный точками А и В.

4. Поверхности обозначаются строчными буквами греческого алфавита:

Чтобы подчеркнуть способ задания поверхности, следует указывать геометрические элементы, которыми она определяется, например:

α(а || b) — плоскость α определяется параллельными прямыми а и b;

5. Углы обозначаются:

6. Угловая: величина (градусная мера) обозначается знаком

Прямой угол отмечается квадратом с точкой внутри

7. Расстояния между геометрическими фигурами обозначаются двумя вертикальными отрезками — ||.

|АВ| — расстояние между точками А и В (длина отрезка АВ);

|Аа| — расстояние от точки А до линии a;

|Аα| — расстояшие от точки А до поверхности α;

|аb| — расстояние между линиями а и b;

|αβ| расстояние между поверхностями α и β.

π2 —фрюнтальная плоскость проекций.

При замене плоскостей проекций или введении новых плоскостей последние обозначают π3, π4 и т. д.

Постояшную прямую эпюра Монжа обозначают k.

10. Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей, любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса, соответствующего плоскости проекции, на которой они получены:

11. Следы плоскостей (поверхностей) обозначаются теми же буквами, что и горизонталь или фронталь, с добавлением подстрочного индекса 0α, подчеркивающего, что эти линии лежат в плоскости проекции и принадлежат плоскости (поверхности) α.

12. Следы прямых (линий) обозначаются заглавными буквами, с которых начинаются слова, определяющие название (в латинской транскрипции) плоскости проекции, которую пересекает линия, с подстрочным индексом, указывающим принадлежность к линии.

Например: Ha — горизонтальный след прямой (линии) а;

Fa — фронтальный след прямой (линии ) a.

13. Последовательность точек, линий (любой фигуры) отмечается подстрочными индексами 1,2,3. n:

Вспомогательная проекция точки, полученная в результате преобразования для получения действительной величины геометрической фигуры, обозначается той же буквой с подстрочным индексом 0:

14. Аксонометрические проекции точек, линий, поверхностей обозначаются теми же буквами, что и натура с добавлением верхнего индекса 0 :

15. Вторичные проекции обозначаются путем добавления верхнего индекса 1 :

Для облегчения чтения чертежей в учебнике при оформлении иллюстративного материала использованы несколько цветов, каждый из которых имеет определенное смысловое значение: линиями (точками) черного цвета обозначены исходные данные; зеленый цвет использован для линий вспомогательных графических построений; красными линиями (точками) показаны результаты построений или те геометрические элементы, на которые следует обратить особое внимание.

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как пишется знак параллельно в геометрии, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как пишется знак параллельно в геометрии», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

Символьные обозначенияДля обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между геометрическими фигурами, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем используются символьные обозначения.

Символьные обозначения, все их многообразие, может быть подразделено на две группы: Символьные обозначения — Первая группа Символы, обозначающие геометрические фигуры и отношения между ними

Обозначения геометрических фигур:

O — точка пересечения осей проекций;

Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса A`, A», A`» Символы взаиморасположения геометрических объектов

Символьные обозначения — Вторая группа Символы обозначающие логические операции

+ |

Для обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между ними, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем в курсе используется геометрический язык, составленный из обозначений и символов, принятых в курсе математики (в частности, в новом курсе геометрии в средней школе).

Все многообразие обозначений и символов, а также связи между ними могут быть подразделены на две группы:

группа I — обозначения геометрических фигур и отношений между ними;

группа II обозначения логических операций, составляющие синтаксическую основу геометрического языка.

Ниже приводится полный список математических символов, используемых в данном курсе. Особое внимание уделяется символам, которые применяются для обозначения проекций геометрических фигур.

Группа I

СИМВОЛЫ, ОБОЗНАЧАЮЩИЕ ГЕОМЕТРИЧЕСКИЕ ФИГУРЫ И ОТНОШЕНИЯ МЕЖДУ НИМИ

А. Обозначение геометрических фигур

1. Геометрическая фигура обозначается — Ф.

2. Точки обозначаются прописными буквами латинского алфавита или арабскими цифрами:

А, В, С, D, … , L, М, N, …

1,2,3,4,…,12,13,14,…

3. Линии, произвольно расположенные по отношению к плоскостям проекций, обозначаются строчными буквами латинского алфавита:

а, b, с, d, … , l, m, n, …

Линии уровня обозначаются: h — горизонталь; f— фронталь.

Для прямых используются также следующие обозначения:

(АВ) — прямая, проходящая через точки А а В;

[АВ) — луч с началом в точке А;

[АВ] — отрезок прямой, ограниченный точками А и В.

4. Поверхности обозначаются строчными буквами греческого алфавита:

α, β, γ, δ,…,ζ,η,ν,…

Чтобы подчеркнуть способ задания поверхности, следует указывать геометрические элементы, которыми она определяется, например:

α(а || b) — плоскость α определяется параллельными прямыми а и b;

β(d1 d2gα) — поверхность β определяется направляющими d1 и d2 , образующей g и плоскостью параллелизма α.

5. Углы обозначаются:

∠ABC — угол с вершиной в точке В, а также ∠α°, ∠β°, … , ∠φ°, …

6. Угловая: величина (градусная мера) обозначается знаком

Прямой угол отмечается квадратом с точкой внутри

7. Расстояния между геометрическими фигурами обозначаются двумя вертикальными отрезками — ||.

Например:

|АВ| — расстояние между точками А и В (длина отрезка АВ);

|Аа| — расстояние от точки А до линии a;

|Аα| — расстояшие от точки А до поверхности α;

|аb| — расстояние между линиями а и b;

|αβ| расстояние между поверхностями α и β.

8. Для плоскостей проекций приняты обозначения: π1 и π2,

где π1 — горизонтальная плоскость проекций;

π2 —фрюнтальная плоскость проекций.

При замене плоскостей проекций или введении новых плоскостей последние обозначают π3, π4 и т. д.

9. Оси проекций обозначаются: х, у, z, где х — ось абсцисс; у — ось ординат; z — ось аппликат.

Постояшную прямую эпюра Монжа обозначают k.

10. Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей, любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса, соответствующего плоскости проекции, на которой они получены:

А’, В’, С’, D’, … , L’, М’, N’, горизонтальные проекции точек; А», В», С», D», … , L», М», N», … фронтальные проекции точек; a’ , b’ , c’ , d’ , … , l’, m’ , n’ , —

горизонтальные проекции линий; а» ,b» , с» , d» , … , l» , m» , n» , … фронтальные проекции линий; α’, β’, γ’, δ’,…,ζ’,η’,ν’,… горизонтальные проекции поверхностей;

α», β», γ», δ»,…,ζ»,η»,ν»,…

фронтальные проекции поверхностей.

11. Следы плоскостей (поверхностей) обозначаются теми же буквами, что и горизонталь или фронталь, с добавлением подстрочного индекса 0α, подчеркивающего, что эти линии лежат в плоскости проекции и принадлежат плоскости (поверхности) α.

Так: h0α — горизонтальный след плоскости (поверхности) α;

f0α — фронтальный след плоскости (поверхности) α.

12. Следы прямых (линий) обозначаются заглавными буквами, с которых начинаются слова, определяющие название (в латинской транскрипции) плоскости проекции, которую пересекает линия, с подстрочным индексом, указывающим принадлежность к линии.

Например: Ha — горизонтальный след прямой (линии) а;

Fa — фронтальный след прямой (линии ) a.

13. Последовательность точек, линий (любой фигуры) отмечается подстрочными индексами 1,2,3,…, n:

А1, А2, А3,…,Аn;

a1, a2, a3,…,an;

α1, α2, α3,…,αn;

Ф1, Ф2, Ф3,…,Фn и т. д.

Вспомогательная проекция точки, полученная в результате преобразования для получения действительной величины геометрической фигуры, обозначается той же буквой с подстрочным индексом 0:

A0, B0, С0, D0, …

Аксонометрические проекции

14. Аксонометрические проекции точек, линий, поверхностей обозначаются теми же буквами, что и натура с добавлением верхнего индекса 0:

А0, В0, С0, D0, …

10, 20, 30, 40, …

a0, b0, c0, d0, …

α0, β0, γ0, δ0, …

15. Вторичные проекции обозначаются путем добавления верхнего индекса 1 :

А1 0, В1 0, С1 0, D1 0, …

11 0, 21 0, 31 0, 41 0, …

a1 0, b1 0, c1 0, d1 0, …

α1 0, β1 0, γ1 0, δ1 0, …

Для облегчения чтения чертежей в учебнике при оформлении иллюстративного материала использованы несколько цветов, каждый из которых имеет определенное смысловое значение: линиями (точками) черного цвета обозначены исходные данные; зеленый цвет использован для линий вспомогательных графических построений; красными линиями (точками) показаны результаты построений или те геометрические элементы, на которые следует обратить особое внимание.

| № по пор. | Обозначение | Содержание | Пример символической записи |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≡ | Совпадают | (АВ)≡(CD) — прямая, проходящая через точки А и В, совпадает с прямой, проходящей через точки С и D |

| 2 | ≅ | Конгруентны | ∠ABC≅∠MNK — угол АВС конгруентен углу MNK |

| 3 | ∼ | Подобны | ΔАВС∼ΔMNK — треугольники АВС и MNK подобны |

| 4 | || | Параллельны | α||β — плоскость α параллельна плоскости β |

| 5 | ⊥ | Перпендикулярны | а⊥b — прямые а и b перпендикулярны |

| 6 |  |

Скрещиваются | с  d — прямые с и d скрещиваются d — прямые с и d скрещиваются |

| 7 |  |

Касательные | t  l — прямая t является касательной к линии l. l — прямая t является касательной к линии l. β  α — плоскость β касательная к поверхности α α — плоскость β касательная к поверхности α |

| 8 | → | Отображаются | Ф1→Ф2 — фигура Ф1 отображается на фигуру Ф2 |

| 9 | S | Центр проецирования. Если центр проецирования несобственная точка, то его положение обозначается стрелкой, указывающей направление проецирования |

— |

| 10 | s | Направление проецирования | — |

| 11 | P | Параллельное проецирование | рsα Параллельное проецирование — параллельное проецирование на плоскость α в направлении s |

| № по пор. | Обозначение | Содержание | Пример символической записи | Пример символической записи в геометрии |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M,N | Множества | — | — |

| 2 | A,B,C,… | Элементы множества |

— | — |

| 3 | { … } | Состоит из … | Ф{A, B, C,… } | Ф{A, B, C,… } — фигура Ф состоит из точек А, В,С, … |

| 4 | ∅ | Пустое множество | L — ∅ — множество L пустое (не содержит элементов ) | — |

| 5 | ∈ | Принадлежит, является элементом | 2∈N (где N — множество натуральных чисел) — число 2 принадлежит множеству N |

А ∈ а — точка А принадлежит прямой а (точка А лежит на прямой а ) |

| 6 | ⊂ | Включает, cодержит | N⊂М — множество N является частью (подмножеством) множества М всех рациональных чисел |

а⊂α — прямая а принадлежит плоскости α (понимается в смысле: множество точек прямой а является подмножеством точек плоскости α) |

| 7 | ∪ | Объединение | С = A U В — множество С есть объединение множеств A и В; {1, 2. 3, 4,5} = {1,2,3}∪{4,5} |

ABCD = [AB] ∪ [ВС] ∪ [CD] — ломаная линия, ABCD есть объединение отрезков [АВ], [ВС], [CD] |

| 8 | ∩ | Пересечение множеств | М=К∩L — множество М есть пересечение множеств К и L (содержит в себе элементы, принадлежащие как множеству К, так и множеству L). М ∩ N = ∅— пересечение множеств М и N есть пустое множество (множества М и N не имеют общих элементов) |

а = α ∩ β — прямая а есть пересечение плоскостей α и β а ∩ b = ∅ — прямые а и b не пересекаются (не имеют общих точек) |

| № по пор. | Обозначение | Содержание | Пример символической записи |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∧ | Конъюнкция предложений; соответствует союзу «и». Предложение (р∧q) истинно тогда и только тогда,когда р и q оба истинны |

α∩β = { К:K∈α∧K∈β} Пересечение поверхностей α и β есть множество точек (линия), состоящее из всех тех и только тех точек К, которые принадлежат как поверхности α, так и поверхности β |

| 2 | ∨ | Дизъюнкция предложений; соответствует союзу «или». Предложение (p∨q) истинно, когда истинно хотя бы одно из предложений р или q (т. е. или р, или q, или оба). |

— |

| 3 | ⇒ | Импликация — логическое следствие. Предложение р⇒q означает: «если р, то и q» | (а||с∧b||с)⇒a||b. Если две прямые параллельны третьей, то они параллельны между собой |

| 4 | ⇔ | Предложение (р⇔q) понимается в смысле: «если р, то и q; если q, то и р» | А∈α⇔А∈l⊂α. Точка принадлежит плоскости, если она принадлежит некоторой линии, принадлежащей этой плоскости. Справедливо также и обратное утверждение: если точка принадлежит некоторой линии, принадлежащей плоскости, то она принадлежит и самой плоскости |

| 5 | ∀ | Квантор общности, читается: для всякого, для всех, для любого. Выражение ∀(x)P(x) означает: «для всякого x: имеет место свойство Р(х) « |

∀( ΔАВС)( = 180°) Для всякого (для любого) треугольника сумма величин его углов = 180°) Для всякого (для любого) треугольника сумма величин его углов при вершинах равна 180° |

| 6 | ∃ | Квантор существования, читается: существует. Выражение ∃(х)P(х) означает: «существует х, обладающее свойством Р(х)» |

(∀α)(∃a)[a⊄α∧a||α].Для любой плоскости α существует прямая а, не принадлежащая плоскости α и параллельная плоскости α |

| 7 | ∃1 | Квантор единственности существования, читается: существует единственное (-я, -й)… Выражение ∃1(x)(Рх) означает: «существует единственное (только одно) х, обладающее свойством Рх» |

(∀ А, В)(А≠B)(∃1а)(а∋А, В) Для любых двух различных точек А и В существует единственная прямая a, проходящая через эти точки. |

| 8 | (Px) | Отрицание высказывания P(x) | а b(∃α)(α⊃а, Ь).Если прямые а и b скрещиваются, то не существует плоскости а, которая содержит их b(∃α)(α⊃а, Ь).Если прямые а и b скрещиваются, то не существует плоскости а, которая содержит их |

| 9 | Отрицание знака | [AB]≠[CD] —отрезок [АВ] не равен отрезку [CD].а?b — линия а не параллельна линии b |