В учебниках по геометрии часто встречаются задачи на подобие фигур. Какой знак используется для обозначения подобия фигур? Какие фигуры называются подобными? Поговорим обо всем этом в нашей статье.

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

Подобными называются фигуры, если одна из них представляет уменьшенную копию другой.

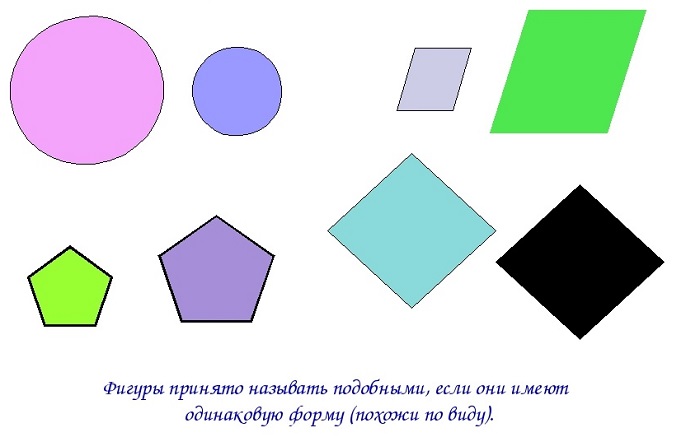

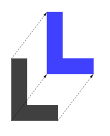

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

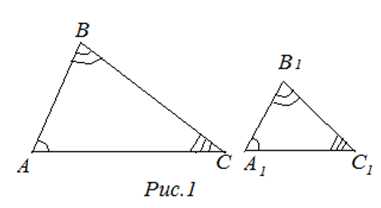

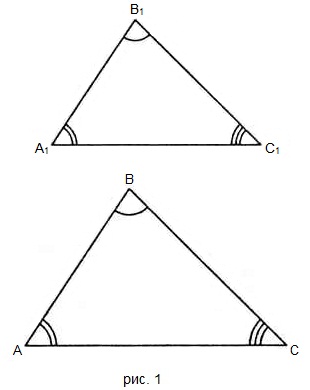

∆ABC ~ ∆A1B1C1

— треугольники ABC и A1B1C1

подобны.

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

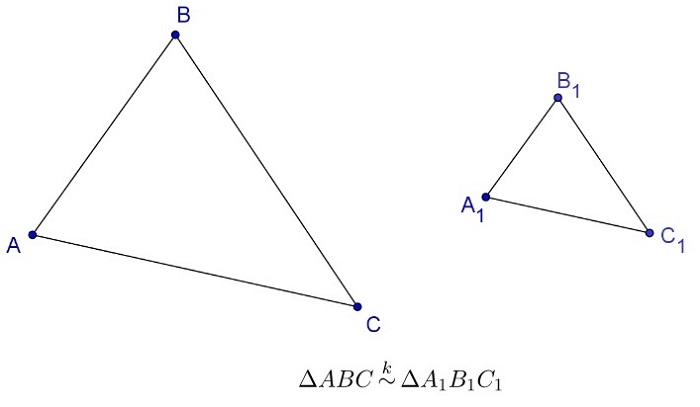

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком ~ обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

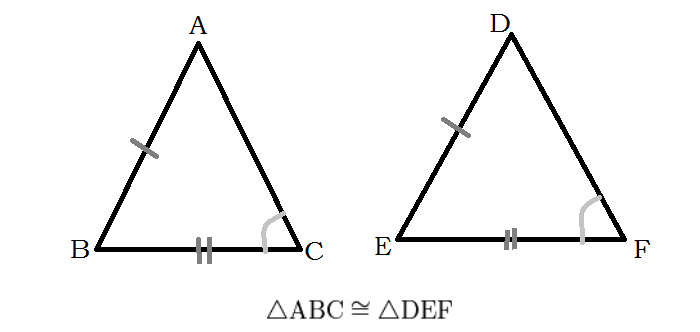

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

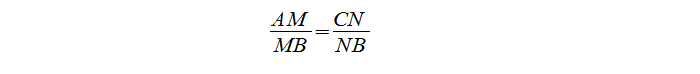

Признаки подобия прямоугольных треугольников

Острые углы: наличие равного острого угла в прямоугольных треугольниках делает их подобными.

Два катета: общая пропорциональность катетам одного прямоугольного треугольника к катетам второго делает их подобными.

Катет и гипотенуза: пропорциональность катета и гипотенузы одного прямоугольного треугольника к катету и гипотенузе второго прямоугольного треугольника делает их подобными.

Утверждения:

-

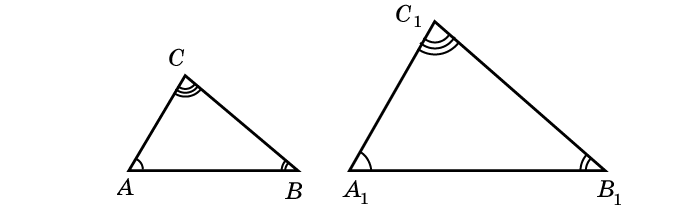

треугольник ∆ABC и треугольник ∆A1B1C1 считаются подобными при равнозначности углов и пропорциональности сторон;

-

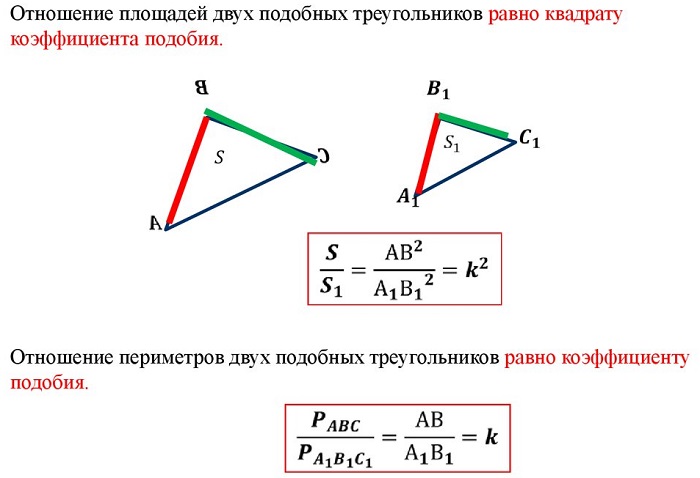

отношение площадей подобных треугольников равно квадрату коэффициента подобия.

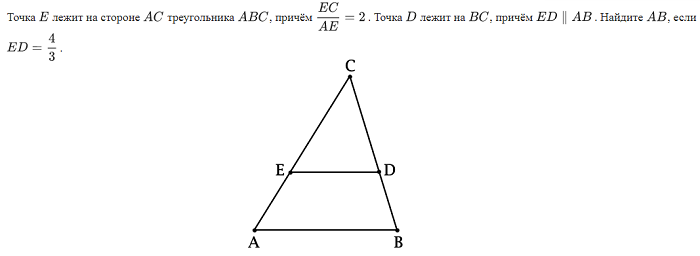

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

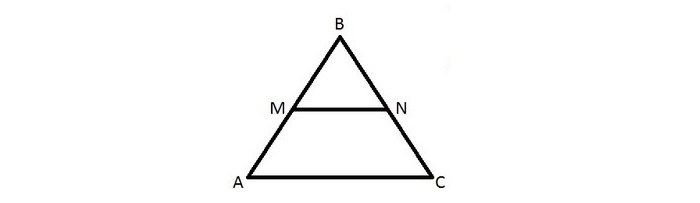

Имеется треугольник ∆ABC, mn — средняя линия. M лежит на AB, N лежит на BC.

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN ~ ∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Примеры решения задач по геометрии на тему «Подобие треугольников»

_____________________________________________________________________

In Euclidean geometry, two objects are similar if they have the same shape, or one has the same shape as the mirror image of the other. More precisely, one can be obtained from the other by uniformly scaling (enlarging or reducing), possibly with additional translation, rotation and reflection. This means that either object can be rescaled, repositioned, and reflected, so as to coincide precisely with the other object. If two objects are similar, each is congruent to the result of a particular uniform scaling of the other.

|

|

|

|

|

For example, all circles are similar to each other, all squares are similar to each other, and all equilateral triangles are similar to each other. On the other hand, ellipses are not all similar to each other, rectangles are not all similar to each other, and isosceles triangles are not all similar to each other.

Figures shown in the same color are similar

If two angles of a triangle have measures equal to the measures of two angles of another triangle, then the triangles are similar. Corresponding sides of similar polygons are in proportion, and corresponding angles of similar polygons have the same measure.

Two congruent shapes are similar, with a scale factor of 1. However, some school textbooks specifically exclude congruent triangles from their definition of similar triangles by insisting that the sizes must be different if the triangles are to qualify as similar.[citation needed]

Similar triangles[edit]

Two triangles, △ABC and △A′B′C′, are similar if and only if corresponding angles have the same measure: this implies that they are similar if and only if the lengths of corresponding sides are proportional.[1] It can be shown that two triangles having congruent angles (equiangular triangles) are similar, that is, the corresponding sides can be proved to be proportional. This is known as the AAA similarity theorem.[2] Note that the «AAA» is a mnemonic: each one of the three A’s refers to an «angle». Due to this theorem, several authors simplify the definition of similar triangles to only require that the corresponding three angles are congruent.[3]

There are several criteria each of which is necessary and sufficient for two triangles to be similar:

- Any two pairs of congruent angles,[4] which in Euclidean geometry implies that their all three angles are congruent:[5]

-

- If ∠BAC is equal in measure to ∠B′A′C′, and ∠ABC is equal in measure to ∠A′B′C′, then this implies that ∠ACB is equal in measure to ∠A′C′B′ and the triangles are similar.

- All the corresponding sides are proportional:[6]

-

- AB/A′B′ = BC/B′C′ = AC/A′C′. This is equivalent to saying that one triangle (or its mirror image) is an enlargement of the other.

- Any two pairs of sides are proportional, and the angles included between these sides are congruent:[7]

-

- AB/A′B′ = BC/B′C′ and ∠ABC is equal in measure to ∠A′B′C′.

This is known as the SAS similarity criterion.[8] The «SAS» is a mnemonic: each one of the two S’s refers to a «side»; the A refers to an «angle» between the two sides.

Symbolically, we write the similarity and dissimilarity of two triangles△ABC and △A′B′C′ as follows:[9]

There are several elementary results concerning similar triangles in Euclidean geometry:[10]

- Any two equilateral triangles are similar.

- Two triangles, both similar to a third triangle, are similar to each other (transitivity of similarity of triangles).

- Corresponding altitudes of similar triangles have the same ratio as the corresponding sides.

- Two right triangles are similar if the hypotenuse and one other side have lengths in the same ratio.[11] There are several equivalent conditions in this case, such as the right triangles having an acute angle of the same measure, or having the lengths of the legs (sides) being in the same proportion.

Given a triangle △ABC and a line segment DE one can, with ruler and compass, find a point F such that △ABC ∼ △DEF. The statement that the point F satisfying this condition exists is Wallis’s postulate[12] and is logically equivalent to Euclid’s parallel postulate.[13] In hyperbolic geometry (where Wallis’s postulate is false) similar triangles are congruent.

In the axiomatic treatment of Euclidean geometry given by George David Birkhoff (see Birkhoff’s axioms) the SAS similarity criterion given above was used to replace both Euclid’s parallel postulate and the SAS axiom which enabled the dramatic shortening of Hilbert’s axioms.[8]

Similar triangles provide the basis for many synthetic (without the use of coordinates) proofs in Euclidean geometry. Among the elementary results that can be proved this way are: the angle bisector theorem, the geometric mean theorem, Ceva’s theorem, Menelaus’s theorem and the Pythagorean theorem. Similar triangles also provide the foundations for right triangle trigonometry.[14]

Other similar polygons[edit]

The concept of similarity extends to polygons with more than three sides. Given any two similar polygons, corresponding sides taken in the same sequence (even if clockwise for one polygon and counterclockwise for the other) are proportional and corresponding angles taken in the same sequence are equal in measure. However, proportionality of corresponding sides is not by itself sufficient to prove similarity for polygons beyond triangles (otherwise, for example, all rhombi would be similar). Likewise, equality of all angles in sequence is not sufficient to guarantee similarity (otherwise all rectangles would be similar). A sufficient condition for similarity of polygons is that corresponding sides and diagonals are proportional.

For given n, all regular n-gons are similar.

Similar curves[edit]

Several types of curves have the property that all examples of that type are similar to each other. These include:

- Lines (any two lines are even congruent)

- Line segments

- Circles

- Parabolas[15]

- Hyperbolas of a specific eccentricity[16]

- Ellipses of a specific eccentricity[16]

- Catenaries

- Graphs of the logarithm function for different bases

- Graphs of the exponential function for different bases

- Logarithmic spirals are self-similar

In Euclidean space[edit]

A similarity (also called a similarity transformation or similitude) of a Euclidean space is a bijection f from the space onto itself that multiplies all distances by the same positive real number r, so that for any two points x and y we have

where «d(x,y)» is the Euclidean distance from x to y.[17] The scalar r has many names in the literature including; the ratio of similarity, the stretching factor and the similarity coefficient. When r = 1 a similarity is called an isometry (rigid transformation). Two sets are called similar if one is the image of the other under a similarity.

As a map f : ℝn → ℝn, a similarity of ratio r takes the form

where A ∈ On(ℝ) is an n × n orthogonal matrix and t ∈ ℝn is a translation vector.

Similarities preserve planes, lines, perpendicularity, parallelism, midpoints, inequalities between distances and line segments.[18] Similarities preserve angles but do not necessarily preserve orientation, direct similitudes preserve orientation and opposite similitudes change it.[19]

The similarities of Euclidean space form a group under the operation of composition called the similarities group S.[20] The direct similitudes form a normal subgroup of S and the Euclidean group E(n) of isometries also forms a normal subgroup.[21] The similarities group S is itself a subgroup of the affine group, so every similarity is an affine transformation.

One can view the Euclidean plane as the complex plane,[22] that is, as a 2-dimensional space over the reals. The 2D similarity transformations can then be expressed in terms of complex arithmetic and are given by f(z) = az + b (direct similitudes) and f(z) = az + b (opposite similitudes), where a and b are complex numbers, a ≠ 0. When |a| = 1, these similarities are isometries.

Area ratio and volume ratio[edit]

The tessellation of the large triangle shows that it is similar to the small triangle with an area ratio of 5. The similarity ratio is 5/h = h/1 = √5. This can be used to construct a non-periodic infinite tiling.

The ratio between the areas of similar figures is equal to the square of the ratio of corresponding lengths of those figures (for example, when the side of a square or the radius of a circle is multiplied by three, its area is multiplied by nine — i.e. by three squared). The altitudes of similar triangles are in the same ratio as corresponding sides. If a triangle has a side of length b and an altitude drawn to that side of length h then a similar triangle with corresponding side of length kb will have an altitude drawn to that side of length kh. The area of the first triangle is, A = 1/2bh, while the area of the similar triangle will be A′ = 1/2(kb)(kh) = k2A. Similar figures which can be decomposed into similar triangles will have areas related in the same way. The relationship holds for figures that are not rectifiable as well.

The ratio between the volumes of similar figures is equal to the cube of the ratio of corresponding lengths of those figures (for example, when the edge of a cube or the radius of a sphere is multiplied by three, its volume is multiplied by 27 — i.e. by three cubed).

Galileo’s square–cube law concerns similar solids. If the ratio of similitude (ratio of corresponding sides) between the solids is k, then the ratio of surface areas of the solids will be k2, while the ratio of volumes will be k3.

Similarity with a center[edit]

Example where each similarity

composed with itself several times successively

has a center at the center of a regular polygon that it shrinks.

Example of direct similarity of center S

decomposed into a rotation of 135° angle

and a homothety that halves areas.

Examples of direct similarities that have each a center.

If a similarity has exactly one invariant point: a point that the similarity keeps unchanged, then this only point is called «center» of the similarity.

On the first image below the title, on the left, one or another similarity shrinks a regular polygon into a concentric one, the vertices of which are each on a side of the previous polygon. This rotational reduction is repeated, so the initial polygon is extended into an abyss of regular polygons. The center of the similarity is the common center of the successive polygons. A red segment joins a vertex of the initial polygon to its image under the similarity, followed by a red segment going to the following image of vertex, and so on to form a spiral. Actually we can see more than three direct similarities on this first image, because every regular polygon is invariant under certain direct similarities, more precisely certain rotations the center of which is the center of the polygon, and a composition of direct similarities is also a direct similarity. For example we see the image of the initial regular pentagon under a homothety of negative

Below the title on the right, the second image shows a similarity decomposed into a rotation and a homothety. Similarity and rotation have the same angle of +135 degrees modulo 360 degrees. Similarity and homothety have the same ratio

This direct similarity that transforms triangle EFA into triangle ATB can be decomposed into a rotation and a homothety of same center S in several manners. For example,

With

How to construct the center S of direct similarity

In general metric spaces[edit]

In a general metric space (X, d), an exact similitude is a function f from the metric space X into itself that multiplies all distances by the same positive scalar r, called f ‘s contraction factor, so that for any two points x and y we have

Weaker versions of similarity would for instance have f be a bi-Lipschitz function and the scalar r a limit

This weaker version applies when the metric is an effective resistance on a topologically self-similar set.

A self-similar subset of a metric space (X, d) is a set K for which there exists a finite set of similitudes { fs }s∈S with contraction factors 0 ≤ rs < 1 such that K is the unique compact subset of X for which

-

A self-similar set constructed with two similitudes z’=0.1[(4+i)z+4] and z’=0.1[(4+7i)z*+5-2i]

These self-similar sets have a self-similar measure μD with dimension D given by the formula

which is often (but not always) equal to the set’s Hausdorff dimension and packing dimension. If the overlaps between the fs(K) are «small», we have the following simple formula for the measure:

Topology[edit]

In topology, a metric space can be constructed by defining a similarity instead of a distance. The similarity is a function such that its value is greater when two points are closer (contrary to the distance, which is a measure of dissimilarity: the closer the points, the lesser the distance).

The definition of the similarity can vary among authors, depending on which properties are desired. The basic common properties are

- Positive defined:

- Majored by the similarity of one element on itself (auto-similarity):

More properties can be invoked, such as reflectivity (

Note that, in the topological sense used here, a similarity is a kind of measure. This usage is not the same as the similarity transformation of the § In Euclidean space and § In general metric spaces sections of this article.

Self-similarity[edit]

Self-similarity means that a pattern is non-trivially similar to itself, e.g., the set {…, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, …} of numbers of the form {2i, 3·2i} where i ranges over all integers. When this set is plotted on a logarithmic scale it has one-dimensional translational symmetry: adding or subtracting the logarithm of two to the logarithm of one of these numbers produces the logarithm of another of these numbers. In the given set of numbers themselves, this corresponds to a similarity transformation in which the numbers are multiplied or divided by two.

Psychology[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) |

The intuition for the notion of geometric similarity already appears in human children, as can be seen in their drawings.[23]

See also[edit]

- Congruence (geometry)

- Hamming distance (string or sequence similarity)

- Helmert transformation

- Inversive geometry

- Jaccard index

- Proportionality

- Basic proportionality theorem

- Semantic similarity

- Similarity search

- Similarity (philosophy)

- Similarity space on numerical taxonomy

- Homoeoid (shell of concentric, similar ellipsoids)

- Solution of triangles

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sibley 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Stahl 2003, p. 127. This is also proved in Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 4.

- ^ For instance, Venema 2006, p. 122 and Henderson & Taimiņa 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 4.

- ^ This statement is not true in non-Euclidean geometry where the triangle angle sum is not 180 degrees.

- ^ Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 5.

- ^ Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 6.

- ^ a b Venema 2006, p. 143.

- ^ Posamentier, Alfred S.; Lehmann, Ingmar (2012). The Secrets of Triangles. Prometheus Books. p. 22.

- ^ Jacobs 1974, pp. 384–393.

- ^ Hadamard, Jacques (2008). Lessons in Geometry, Vol. I: Plane Geometry. American Mathematical Society. Theorem 120, p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8218-4367-3.

- ^ Named for John Wallis (1616–1703)

- ^ Venema 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Venema 2006, p. 145.

- ^ a proof from academia.edu

- ^ a b The shape of an ellipse or hyperbola depends only on the ratio b/a

- ^ Smart 1998, p. 92.

- ^ Yale 1968, p. 47 Theorem 2.1.

- ^ Pedoe 1988, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Yale 1968, p. 46.

- ^ Pedoe 1988, p. 182.

- ^ This traditional term, as explained in its article, is a misnomer. This is actually the 1-dimensional complex line.

- ^ Cox, Dana Christine (2008). Understanding Similarity: Bridging Geometric and Numeric Contexts for Proportional Reasoning (Ph.D.). Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. ISBN 978-0-549-75657-6. S2CID 61331653.

References[edit]

- Henderson, David W.; Taimiņa, Daina (2005). Experiencing Geometry/Euclidean and Non-Euclidean with History (3rd ed.). Pearson Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-143748-7.

- Jacobs, Harold R. (1974). Geometry. W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-0456-0.

- Pedoe, Dan (1988) [1970]. Geometry/A Comprehensive Course. Dover. ISBN 0-486-65812-0.

- Sibley, Thomas Q. (1998). The Geometric Viewpoint/A Survey of Geometries. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-87450-1.

- Smart, James R. (1998). Modern Geometries (5th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-35188-3.

- Stahl, Saul (2003). Geometry/From Euclid to Knots. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-032927-1.

- Venema, Gerard A. (2006). Foundations of Geometry. Pearson Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-143700-5.

- Yale, Paul B. (1968). Geometry and Symmetry. Holden-Day.

Further reading[edit]

- Cederberg, Judith N. (2001) [1989]. «Chapter 3.12: Similarity Transformations». A Course in Modern Geometries. Springer. pp. 183–189. ISBN 0-387-98972-2.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1969) [1961]. «§5 Similarity in the Euclidean Plane». pp. 67–76. «§7 Isometry and Similarity in Euclidean Space». pp. 96–104. Introduction to Geometry. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ewald, Günter (1971). Geometry: An Introduction. Wadsworth Publishing. pp. 106, 181.

- Martin, George E. (1982). «Chapter 13: Similarities in the Plane». Transformation Geometry: An Introduction to Symmetry. Springer. pp. 136–146. ISBN 0-387-90636-3.

External links[edit]

- Animated demonstration of similar triangles

In Euclidean geometry, two objects are similar if they have the same shape, or one has the same shape as the mirror image of the other. More precisely, one can be obtained from the other by uniformly scaling (enlarging or reducing), possibly with additional translation, rotation and reflection. This means that either object can be rescaled, repositioned, and reflected, so as to coincide precisely with the other object. If two objects are similar, each is congruent to the result of a particular uniform scaling of the other.

|

|

|

|

|

For example, all circles are similar to each other, all squares are similar to each other, and all equilateral triangles are similar to each other. On the other hand, ellipses are not all similar to each other, rectangles are not all similar to each other, and isosceles triangles are not all similar to each other.

Figures shown in the same color are similar

If two angles of a triangle have measures equal to the measures of two angles of another triangle, then the triangles are similar. Corresponding sides of similar polygons are in proportion, and corresponding angles of similar polygons have the same measure.

Two congruent shapes are similar, with a scale factor of 1. However, some school textbooks specifically exclude congruent triangles from their definition of similar triangles by insisting that the sizes must be different if the triangles are to qualify as similar.[citation needed]

Similar triangles[edit]

Two triangles, △ABC and △A′B′C′, are similar if and only if corresponding angles have the same measure: this implies that they are similar if and only if the lengths of corresponding sides are proportional.[1] It can be shown that two triangles having congruent angles (equiangular triangles) are similar, that is, the corresponding sides can be proved to be proportional. This is known as the AAA similarity theorem.[2] Note that the «AAA» is a mnemonic: each one of the three A’s refers to an «angle». Due to this theorem, several authors simplify the definition of similar triangles to only require that the corresponding three angles are congruent.[3]

There are several criteria each of which is necessary and sufficient for two triangles to be similar:

- Any two pairs of congruent angles,[4] which in Euclidean geometry implies that their all three angles are congruent:[5]

-

- If ∠BAC is equal in measure to ∠B′A′C′, and ∠ABC is equal in measure to ∠A′B′C′, then this implies that ∠ACB is equal in measure to ∠A′C′B′ and the triangles are similar.

- All the corresponding sides are proportional:[6]

-

- AB/A′B′ = BC/B′C′ = AC/A′C′. This is equivalent to saying that one triangle (or its mirror image) is an enlargement of the other.

- Any two pairs of sides are proportional, and the angles included between these sides are congruent:[7]

-

- AB/A′B′ = BC/B′C′ and ∠ABC is equal in measure to ∠A′B′C′.

This is known as the SAS similarity criterion.[8] The «SAS» is a mnemonic: each one of the two S’s refers to a «side»; the A refers to an «angle» between the two sides.

Symbolically, we write the similarity and dissimilarity of two triangles△ABC and △A′B′C′ as follows:[9]

There are several elementary results concerning similar triangles in Euclidean geometry:[10]

- Any two equilateral triangles are similar.

- Two triangles, both similar to a third triangle, are similar to each other (transitivity of similarity of triangles).

- Corresponding altitudes of similar triangles have the same ratio as the corresponding sides.

- Two right triangles are similar if the hypotenuse and one other side have lengths in the same ratio.[11] There are several equivalent conditions in this case, such as the right triangles having an acute angle of the same measure, or having the lengths of the legs (sides) being in the same proportion.

Given a triangle △ABC and a line segment DE one can, with ruler and compass, find a point F such that △ABC ∼ △DEF. The statement that the point F satisfying this condition exists is Wallis’s postulate[12] and is logically equivalent to Euclid’s parallel postulate.[13] In hyperbolic geometry (where Wallis’s postulate is false) similar triangles are congruent.

In the axiomatic treatment of Euclidean geometry given by George David Birkhoff (see Birkhoff’s axioms) the SAS similarity criterion given above was used to replace both Euclid’s parallel postulate and the SAS axiom which enabled the dramatic shortening of Hilbert’s axioms.[8]

Similar triangles provide the basis for many synthetic (without the use of coordinates) proofs in Euclidean geometry. Among the elementary results that can be proved this way are: the angle bisector theorem, the geometric mean theorem, Ceva’s theorem, Menelaus’s theorem and the Pythagorean theorem. Similar triangles also provide the foundations for right triangle trigonometry.[14]

Other similar polygons[edit]

The concept of similarity extends to polygons with more than three sides. Given any two similar polygons, corresponding sides taken in the same sequence (even if clockwise for one polygon and counterclockwise for the other) are proportional and corresponding angles taken in the same sequence are equal in measure. However, proportionality of corresponding sides is not by itself sufficient to prove similarity for polygons beyond triangles (otherwise, for example, all rhombi would be similar). Likewise, equality of all angles in sequence is not sufficient to guarantee similarity (otherwise all rectangles would be similar). A sufficient condition for similarity of polygons is that corresponding sides and diagonals are proportional.

For given n, all regular n-gons are similar.

Similar curves[edit]

Several types of curves have the property that all examples of that type are similar to each other. These include:

- Lines (any two lines are even congruent)

- Line segments

- Circles

- Parabolas[15]

- Hyperbolas of a specific eccentricity[16]

- Ellipses of a specific eccentricity[16]

- Catenaries

- Graphs of the logarithm function for different bases

- Graphs of the exponential function for different bases

- Logarithmic spirals are self-similar

In Euclidean space[edit]

A similarity (also called a similarity transformation or similitude) of a Euclidean space is a bijection f from the space onto itself that multiplies all distances by the same positive real number r, so that for any two points x and y we have

where «d(x,y)» is the Euclidean distance from x to y.[17] The scalar r has many names in the literature including; the ratio of similarity, the stretching factor and the similarity coefficient. When r = 1 a similarity is called an isometry (rigid transformation). Two sets are called similar if one is the image of the other under a similarity.

As a map f : ℝn → ℝn, a similarity of ratio r takes the form

where A ∈ On(ℝ) is an n × n orthogonal matrix and t ∈ ℝn is a translation vector.

Similarities preserve planes, lines, perpendicularity, parallelism, midpoints, inequalities between distances and line segments.[18] Similarities preserve angles but do not necessarily preserve orientation, direct similitudes preserve orientation and opposite similitudes change it.[19]

The similarities of Euclidean space form a group under the operation of composition called the similarities group S.[20] The direct similitudes form a normal subgroup of S and the Euclidean group E(n) of isometries also forms a normal subgroup.[21] The similarities group S is itself a subgroup of the affine group, so every similarity is an affine transformation.

One can view the Euclidean plane as the complex plane,[22] that is, as a 2-dimensional space over the reals. The 2D similarity transformations can then be expressed in terms of complex arithmetic and are given by f(z) = az + b (direct similitudes) and f(z) = az + b (opposite similitudes), where a and b are complex numbers, a ≠ 0. When |a| = 1, these similarities are isometries.

Area ratio and volume ratio[edit]

The tessellation of the large triangle shows that it is similar to the small triangle with an area ratio of 5. The similarity ratio is 5/h = h/1 = √5. This can be used to construct a non-periodic infinite tiling.

The ratio between the areas of similar figures is equal to the square of the ratio of corresponding lengths of those figures (for example, when the side of a square or the radius of a circle is multiplied by three, its area is multiplied by nine — i.e. by three squared). The altitudes of similar triangles are in the same ratio as corresponding sides. If a triangle has a side of length b and an altitude drawn to that side of length h then a similar triangle with corresponding side of length kb will have an altitude drawn to that side of length kh. The area of the first triangle is, A = 1/2bh, while the area of the similar triangle will be A′ = 1/2(kb)(kh) = k2A. Similar figures which can be decomposed into similar triangles will have areas related in the same way. The relationship holds for figures that are not rectifiable as well.

The ratio between the volumes of similar figures is equal to the cube of the ratio of corresponding lengths of those figures (for example, when the edge of a cube or the radius of a sphere is multiplied by three, its volume is multiplied by 27 — i.e. by three cubed).

Galileo’s square–cube law concerns similar solids. If the ratio of similitude (ratio of corresponding sides) between the solids is k, then the ratio of surface areas of the solids will be k2, while the ratio of volumes will be k3.

Similarity with a center[edit]

Example where each similarity

composed with itself several times successively

has a center at the center of a regular polygon that it shrinks.

Example of direct similarity of center S

decomposed into a rotation of 135° angle

and a homothety that halves areas.

Examples of direct similarities that have each a center.

If a similarity has exactly one invariant point: a point that the similarity keeps unchanged, then this only point is called «center» of the similarity.

On the first image below the title, on the left, one or another similarity shrinks a regular polygon into a concentric one, the vertices of which are each on a side of the previous polygon. This rotational reduction is repeated, so the initial polygon is extended into an abyss of regular polygons. The center of the similarity is the common center of the successive polygons. A red segment joins a vertex of the initial polygon to its image under the similarity, followed by a red segment going to the following image of vertex, and so on to form a spiral. Actually we can see more than three direct similarities on this first image, because every regular polygon is invariant under certain direct similarities, more precisely certain rotations the center of which is the center of the polygon, and a composition of direct similarities is also a direct similarity. For example we see the image of the initial regular pentagon under a homothety of negative

Below the title on the right, the second image shows a similarity decomposed into a rotation and a homothety. Similarity and rotation have the same angle of +135 degrees modulo 360 degrees. Similarity and homothety have the same ratio

This direct similarity that transforms triangle EFA into triangle ATB can be decomposed into a rotation and a homothety of same center S in several manners. For example,

With

How to construct the center S of direct similarity

In general metric spaces[edit]

In a general metric space (X, d), an exact similitude is a function f from the metric space X into itself that multiplies all distances by the same positive scalar r, called f ‘s contraction factor, so that for any two points x and y we have

Weaker versions of similarity would for instance have f be a bi-Lipschitz function and the scalar r a limit

This weaker version applies when the metric is an effective resistance on a topologically self-similar set.

A self-similar subset of a metric space (X, d) is a set K for which there exists a finite set of similitudes { fs }s∈S with contraction factors 0 ≤ rs < 1 such that K is the unique compact subset of X for which

-

A self-similar set constructed with two similitudes z’=0.1[(4+i)z+4] and z’=0.1[(4+7i)z*+5-2i]

These self-similar sets have a self-similar measure μD with dimension D given by the formula

which is often (but not always) equal to the set’s Hausdorff dimension and packing dimension. If the overlaps between the fs(K) are «small», we have the following simple formula for the measure:

Topology[edit]

In topology, a metric space can be constructed by defining a similarity instead of a distance. The similarity is a function such that its value is greater when two points are closer (contrary to the distance, which is a measure of dissimilarity: the closer the points, the lesser the distance).

The definition of the similarity can vary among authors, depending on which properties are desired. The basic common properties are

- Positive defined:

- Majored by the similarity of one element on itself (auto-similarity):

More properties can be invoked, such as reflectivity (

Note that, in the topological sense used here, a similarity is a kind of measure. This usage is not the same as the similarity transformation of the § In Euclidean space and § In general metric spaces sections of this article.

Self-similarity[edit]

Self-similarity means that a pattern is non-trivially similar to itself, e.g., the set {…, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, …} of numbers of the form {2i, 3·2i} where i ranges over all integers. When this set is plotted on a logarithmic scale it has one-dimensional translational symmetry: adding or subtracting the logarithm of two to the logarithm of one of these numbers produces the logarithm of another of these numbers. In the given set of numbers themselves, this corresponds to a similarity transformation in which the numbers are multiplied or divided by two.

Psychology[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) |

The intuition for the notion of geometric similarity already appears in human children, as can be seen in their drawings.[23]

See also[edit]

- Congruence (geometry)

- Hamming distance (string or sequence similarity)

- Helmert transformation

- Inversive geometry

- Jaccard index

- Proportionality

- Basic proportionality theorem

- Semantic similarity

- Similarity search

- Similarity (philosophy)

- Similarity space on numerical taxonomy

- Homoeoid (shell of concentric, similar ellipsoids)

- Solution of triangles

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sibley 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Stahl 2003, p. 127. This is also proved in Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 4.

- ^ For instance, Venema 2006, p. 122 and Henderson & Taimiņa 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 4.

- ^ This statement is not true in non-Euclidean geometry where the triangle angle sum is not 180 degrees.

- ^ Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 5.

- ^ Euclid’s Elements, Book VI, Proposition 6.

- ^ a b Venema 2006, p. 143.

- ^ Posamentier, Alfred S.; Lehmann, Ingmar (2012). The Secrets of Triangles. Prometheus Books. p. 22.

- ^ Jacobs 1974, pp. 384–393.

- ^ Hadamard, Jacques (2008). Lessons in Geometry, Vol. I: Plane Geometry. American Mathematical Society. Theorem 120, p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8218-4367-3.

- ^ Named for John Wallis (1616–1703)

- ^ Venema 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Venema 2006, p. 145.

- ^ a proof from academia.edu

- ^ a b The shape of an ellipse or hyperbola depends only on the ratio b/a

- ^ Smart 1998, p. 92.

- ^ Yale 1968, p. 47 Theorem 2.1.

- ^ Pedoe 1988, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Yale 1968, p. 46.

- ^ Pedoe 1988, p. 182.

- ^ This traditional term, as explained in its article, is a misnomer. This is actually the 1-dimensional complex line.

- ^ Cox, Dana Christine (2008). Understanding Similarity: Bridging Geometric and Numeric Contexts for Proportional Reasoning (Ph.D.). Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. ISBN 978-0-549-75657-6. S2CID 61331653.

References[edit]

- Henderson, David W.; Taimiņa, Daina (2005). Experiencing Geometry/Euclidean and Non-Euclidean with History (3rd ed.). Pearson Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-143748-7.

- Jacobs, Harold R. (1974). Geometry. W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-0456-0.

- Pedoe, Dan (1988) [1970]. Geometry/A Comprehensive Course. Dover. ISBN 0-486-65812-0.

- Sibley, Thomas Q. (1998). The Geometric Viewpoint/A Survey of Geometries. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-87450-1.

- Smart, James R. (1998). Modern Geometries (5th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-35188-3.

- Stahl, Saul (2003). Geometry/From Euclid to Knots. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-032927-1.

- Venema, Gerard A. (2006). Foundations of Geometry. Pearson Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-143700-5.

- Yale, Paul B. (1968). Geometry and Symmetry. Holden-Day.

Further reading[edit]

- Cederberg, Judith N. (2001) [1989]. «Chapter 3.12: Similarity Transformations». A Course in Modern Geometries. Springer. pp. 183–189. ISBN 0-387-98972-2.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1969) [1961]. «§5 Similarity in the Euclidean Plane». pp. 67–76. «§7 Isometry and Similarity in Euclidean Space». pp. 96–104. Introduction to Geometry. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ewald, Günter (1971). Geometry: An Introduction. Wadsworth Publishing. pp. 106, 181.

- Martin, George E. (1982). «Chapter 13: Similarities in the Plane». Transformation Geometry: An Introduction to Symmetry. Springer. pp. 136–146. ISBN 0-387-90636-3.

External links[edit]

- Animated demonstration of similar triangles

Знак подобия в геометрии

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЕ

Два треугольника и называются подобными, если у них равные углы и пропорциональные стороны.

Обозначают подобие треугольников знаком «».

Пример. (читают: треугольник подобен треугольнику ).

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Иногда над знаком подобия ставят коэффициент подобия треугольников, т.е. .

Знак «» представляет собой типографский знак «тильда», который изображается в виде волнистой черты. Этот знак может быть как надстрочным, так и междустрочным.

В математике «тильда» используется для обозначения различных видов отношений эквивалентности, в частности, отношения подобия.

Знак «тильда» (или «двойная тильда» ), который стоит перед числом может означать «примерно», «приблизительно равно».

В алгебре высказываний знак «» обозначает логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

Если знак «тильда» сочетать со знаком равенства: «», то он будет обозначать отношение конгруэнтности.

Также знак «тильда» активно используется в информатике и вычислительной технике. Например, в редакторе Tex этот знак означает «неразрывный пробел».

ru.solverbook.com

Знак подобия треугольников в геометрии — что значит «~» в геометрии? — 22 ответа

В разделе Школы на вопрос что значит «~» в геометрии? заданный автором Нету лучший ответ это Это знак «Приблизительно»

Ответ от 22 ответа[гуру]

Привет! Вот подборка тем с ответами на Ваш вопрос: что значит «~» в геометрии?

Ответ от Mitternacht[гуру]

Вроде приблизительно

Ответ от Острословить[гуру]

подобие.. . посмотрите в планиметрии в правилах подобия треугольников.. . там этот знак активно используется…

Ответ от Невропатолог

[гуру]

точно не уверенна, но может подобие Для тех кто пишет приблизительно: знак приблизительности похож на знак =,только линии там волнистые, как в вопросе

Ответ от Недоносок[новичек]

Это значит приблизительно

Ответ от МiRaMih[гуру]

Подобие

Ответ от Антон Рзаханов[активный]

это знак подобия)) мы щас проходим)

Ответ от Hip-hop4live[гуру]

Подобие!!!!

Ответ от Ёаша Рощин[активный]

Прекрасных комедий множество. Но одна из лучших «Не упускай из виду! » 1975г. с Пьером Ришаром.

Узнал об этом фильме у него на спектакле в Москве феврале в этом году. Решил посмотреть этот фильм, у меня была истерика, чуть упал под стол от смеха, особенно когда он бегал с унитазом на ноге )) А на самом спектакле Ришар такие байки травил, особенно про Депардье, что я реально устал смеяться )

Ответ от Влад Матвеев[новичек]

подобие

Ответ от Supreme[новичек]

Подобие )

Признаки подобия треугольников на Википедии

Посмотрите статью на википедии про Признаки подобия треугольников

Ответить на вопрос:

22oa.ru

что значит «~» в геометрии?

Вроде приблизительно

подобие.. .

посмотрите в планиметрии в правилах подобия треугольников.. . там этот знак активно используется…

точно не уверенна, но может подобие

Для тех кто пишет приблизительно:

знак приблизительности похож на знак =,только линии там волнистые, как в вопросе

Это значит приблизительно

это знак подобия)) мы щас проходим)

приблизительно

этот символ означает «подобие», а два параллельных (друг под другом) символа означают «приблизительно»

Это «тильда», она обозначает «подобие» в геометрии.

touch.otvet.mail.ru

Что в Геометрий обозначает недорисованная, перевёрнутая 8-ка?

лежащая на боку 8 знак бесконечности …

Перевёрнутая восьмёрка выглядит также как обычная.

Интеграл, параграф. Больше не знаю. У меня была тройка по геометрии (((

в геометрии такой знак обозначает подобие фигур

Я насколько помню так всю жизнь обозначали подобие, НО такого символа фактически нет. Это ~ и она не настолько загнута по краям, как её в школах рисовали.

Перевернутая восьмерка обозначает бесконечность

touch.otvet.mail.ru

Как называется этот знак (Геометрия)???

Дуга выгнута вверх? Тогда это знак пересечения. Если выгнута вниз — объединение…. Если я, конечно, вспомнила правильно

он так и называется дуга. а читается например дуга ОВ

может»принадлежит» ет обуква э ?

Вероятно ето пересечение, если на U похоже.

Это значит точка О получается пересечением АВ и СД. Может это знак пересечения? Больше на ум ничего не идет, что смысл бы имело…

это и есть -дуга — 100%

Если дуга выгнута вниз, значит это «дуга», а если вверх то «пересечение».

touch.otvet.mail.ru

Содержание

- Определение прямой

- Определение и обозначение подобных треугольников

- Определение треугольника

- Классификация треугольников

- Прямая линия. Уравнение прямой.

- Свойства прямой

- Основные признаки делимости.

- Типы треугольников

- По величине углов

- По числу равных сторон

- Признаки равенства треугольников

- Окружность описанная вокруг треугольника

- Вычисление площади треугольника в пространстве с помощью векторов

- Свойства окружности описанной вокруг треугольника

- Формулы радиуса окружности описанной вокруг треугольника

- Теоремы о треугольниках

- Связь между вписанной и описанной окружностями треугольника

- Соотношение сторон в произвольном треугольнике

- Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

- Медианы треугольника

- Свойства медиан треугольника:

- Формулы медиан треугольника

- Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

- Биссектрисы треугольника

- Свойства биссектрис треугольника:

- Формулы биссектрис треугольника

- Примеры наиболее часто встречающихся подобных треугольников

- Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

- Взаимное расположение прямых

Определение прямой

Определение прямой начинается с определения линии. Что такое линия? Это множество точек, соединенных между собой. Линия может быть прямой, кривой, ломанной, непрерывной и даже разомкнутой. И именно из-за этого разнообразия линии очень трудно определить в пространстве. Непонятно, как пройдет та или иная кривая, когда выйдет за пределы листа. Поэтому был выделен отдельный вид линий – прямые.

Рис. 1. Виды прямых.

Когда в разговоре вы слышите прямая – люди имеют в виду прямую линию, но последнее слово в словосочетании принято опускать.

Что такое прямая в математике? Прямые это бесконечные непрерывные линии, которые не имеют искривлений. Первое правило линий: через любые две точки можно провести линию. А вот через три точки уже не всегда. Чаще всего через три точки можно провести три прямых.

Если прямая проходит через три точки, то про эти точки говорят, что они лежат на одной прямой. Прямые, как правило, обозначают малой латинской буквой или по названию двух точек на прямой.

Почему двух, а не трех? Очень просто: через две точки может пройти только одна прямая. Тогда как через одну: бесконечное множество. А три точки не имеет смысла использовать: ни к чему усложнять обозначение.

Определение и обозначение подобных треугольников

Подобными называются треугольники, у которых углы соответственно равны, а стороны одного треугольника пропорциональны сходственным сторонам другого.

Сходственные стороны в подобных треугольниках – это стороны, лежащие напротив их равных углов.

Для обозначения подобия фигур используется специальный символ “∼“. Например, △ABC ∼ △KLM.

Определение треугольника

Треугольник – это геометрическая фигура на плоскости, состоящая из трех сторон, которые образованы путем соединения трех точек, не лежащих на одной прямой. Для обозначения используется специальный символ – △.

- Точки A, B и C – вершины треугольника.

- Отрезки AB, BC и AC – стороны треугольника, которые часто обозначаются в виде одной латинской буквы. Например, AB = a, BC = b, AC = c.

- Внутренность треугольника – часть плоскости, ограниченная сторонами треугольника.

Стороны треугольника в вершинах образуют три угла, традиционно обозначающиеся греческими буквами – α, β, γ и т.д. Из-за этого треугольник еще называют многоугольником с тремя углами.

Углы можно, также, обозначать с помощью специального знака “∠“:

- α – ∠BAC или ∠CAB

- β – ∠ABC или ∠CBA

- γ – ∠ACB или ∠BCA

Классификация треугольников

В зависимости от величины углов или количества равных сторон выделяют следующие виды фигуры:

1. Остроугольный – треугольник, у которого все три угла острые, т.е. меньше 90°.

2. Тупоугольный – треугольник, в котором один из углов больше 90°. Два остальных угла – острые.

3. Прямоугольный – треугольник, в котором один из углов является прямым, т.е. равен 90°. В такой фигуре две стороны, которые образуют прямой угол, называются катетами (AB и AC). Третья сторона, расположенная напротив прямого угла – это гипотенуза (BC).

4. Разносторонний – треугольник, у которого все стороны имеют разную длину.

5. Равнобедренный – треугольник, имеющие две равные стороны, которые называются боковыми (AB и BC). Третья сторона – это основание (AC). В данной фигуре углы при основании равны (∠BAC = ∠BCA).

6. Равносторонний (или правильный) – треугольник, у которого все стороны имеют одинаковую длину. Также все его углы равны 60°.

Прямая линия. Уравнение прямой.

Основная информация по курсу геометрии для обучения и подготовки в экзаменам, ГВЭ, ЕГЭ, ОГЭ, ГИА

Прямая линия. Уравнение прямой.

Свойства прямой

1. Через любые две точки можно провести только одну прямую линию.

Это основное свойство прямой. Оно часто используется на практике, для прокладывания прямых линий с помощью двух каких-либо объектов.

2. Если две любые точки прямой лежат на плоскости, то все точки этой прямой лежат на той же плоскости.

3. Через одну точку можно провести бесконечно много прямых.

4. Есть точки лежащие на прямой и не лежащие на ней.

Точки N и M лежат на прямой a. Точка L не лежит на прямой a.

Для записи принадлежности точки к прямой используется символ принадлежности – ∈. Например, запись M ∈ a обозначает, что точка M принадлежит прямой a. Для того, чтобы указать что точка не принадлежит прямой можно использовать символ ∉. Например, запись L ∉ a обозначает, что точка L не принадлежит прямой a.

5. Из трёх разных точек, лежащих на одной прямой, только одна может лежать между двумя другими точками.

На рисунке изображена прямая с тремя точками A, B и C, лежащими на ней. Про эти точки можно сказать: Точка B лежит между точками A и C, точка B разделяет точки A и C, – или, – точки A и C лежат по разные стороны от точки B

. Также можно сказать: Точки B и C лежат по одну сторону от точки A, они не разделяются точкой A, – или, – точки A и B лежат по одну сторону от точки C

.

6. Две прямые, лежащие на одной плоскости, или пересекаются друг с другом в одной точке, или являются параллельными.

Основные признаки делимости.

Признак делимости – правила с помощью которого можно относительно бегло найти, является ли число кратным предварительно выбранному.

Основные признаки делимости.

Типы треугольников

| Типы треугольников | ||

|---|---|---|

Прямоугольный |

||

Разносторонний |

Равносторонний |

По величине углов

сумма углов треугольника равна 180°.

Поскольку в евклидовой геометрии сумма углов треугольника равна 180°, то не менее двух углов в треугольнике должны быть острыми (меньшими 90°). Выделяют следующие виды треугольников:

- Если все углы треугольника острые, то треугольник называется остроугольным

- Если один из углов треугольника тупой (больше 90°), то треугольник называется тупоугольным

- Если один из углов треугольника прямой (равен 90°), то треугольник называется прямоугольным. Две стороны, образующие прямой угол, называются катетами, а сторона, противолежащая прямому углу, называется гипотенузой.

В геометрии Лобачевского сумма углов треугольника всегда меньше 180°, а на сфере — всегда больше. Разность суммы углов треугольника и 180° называется дефектом. Дефект пропорционален площади треугольника, таким образом, у бесконечно малых треугольников на сфере или плоскости Лобачевского сумма углов будет мало отличаться от 180°.

По числу равных сторон

- Равнобедренным называется треугольник, у которого две стороны равны. Эти стороны называются боковыми, третья сторона называется основанием. В равнобедренном треугольнике углы при основании равны. Высота, медиана и биссектриса равнобедренного треугольника, опущенные на основание, совпадают.

- Равносторонним называется треугольник, у которого все три стороны равны. В равностороннем треугольнике все углы равны 60°, а центры вписанной и описанной окружностей совпадают.

Признаки равенства треугольников

Треугольник на евклидовой плоскости однозначно (с точностью до конгруэнтности) можно определить по следующим тройкам основных элементов:

- a, b, γ (равенство по двум сторонам и углу лежащему между ними);

- a, β, γ (равенство по стороне и двум прилежащим углам);

- a, b, c (равенство по трём сторонам).

Признаки равенства прямоугольных треугольников:

- по катету и гипотенузе;

- по двум катетам;

- по катету и острому углу;

- по гипотенузе и острому углу.

В сферической геометрии и в геометрии Лобачевского существует признак равенства треугольников по трём углам.

Окружность описанная вокруг треугольника

Определение. Окружность называется описанной вокруг треугольника, если она содержит все вершины треугльника.

Вычисление площади треугольника в пространстве с помощью векторов

Пусть вершины треугольника находятся в точках .

Введём вектор площади . Длина этого вектора равна площади треугольника, а направлен он по нормали к плоскости треугольника:

и аналогично

Площадь треугольника равна .

Альтернативой служит вычисление длин сторон (по теореме Пифагора) и далее по формуле Герона.

Свойства окружности описанной вокруг треугольника

Центр описанной вокруг треугольника окружности лежит на пересечении серединных перпендикуляров к его сторонам.

Вокруг любого треугольника можно описать окружность, и только одну.

Свойства углов

Центр описанной окружности лежит внутри остроугольного треугольника, снаружи тупоугольнго треугольника, на середине гипотенузы прямоугольного треугольника.

Формулы радиуса окружности описанной вокруг треугольника

Радиус описанной окружности через три стороны и площадь:

Радиус описанной окружности через площадь и три угла:

R = S 2 sin α sin β sin γ

Радиус описанной окружности через сторону и противоположный угол (теорема синусов):

R = a 2 sin α = b 2 sin β = c 2 sin γ

Теоремы о треугольниках

Теорема Дезарга: если два треугольника перспективны (прямые, проходящие через соответственные вершины треугольников, пересекаются в одной точке), то их соответственные стороны пересекаются на одной прямой.

Теорема Сонда́: если два треугольника перспективны и ортологичны (перпендикуляры, опущенные из вершин одного треугольника на стороны, противоположные соответственным вершинам треугольника, и наоборот), то оба центра ортологии (точки пересечения этих перпендикуляров) и центр перспективы лежат на одной прямой, перпендикулярной оси перспективы (прямой из теоремы Дезарга).

Теорема Чевы

Теорема Менелая

Связь между вписанной и описанной окружностями треугольника

Если d — расстояние между центрами вписанной и описанной окружностей, то.

d2 = R2 – 2Rr

= 4 sin

α 2

sin

β 2

sin

γ 2

= cos α + cos β + cos γ – 1

Соотношение сторон в произвольном треугольнике

Теорема косинусов:

Теорема синусов:

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

Имеется треугольник ∆ABC, mn – средняя линия. M лежит на AB, N лежит на BC.

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN ~ ∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Определение. Медиана треугольника ― отрезок внутри треугольника, который соединяет вершину треугольника с серединой противоположной стороны.

Свойства медиан треугольника:

-

Медианы треугольника пересекаются в одной точке. (Точка пересечения медиан называется центроидом)

-

В точке пересечения медианы треугольника делятся в отношении два к одному (2:1)

AO OD=

BO OE

=

CO OF

=

2 1

-

Медиана треугольника делит треугольник на две равновеликие части

S∆ABD = S∆ACD

S∆BEA = S∆BEC

S∆CBF = S∆CAF

-

Треугольник делится тремя медианами на шесть равновеликих треугольников.

S∆AOF = S∆AOE = S∆BOF = S∆BOD = S∆COD = S∆COE

-

Из векторов, образующих медианы, можно составить треугольник.

Формулы медиан треугольника

Формулы медиан треугольника через стороны

ma = 1 2 √2b2+2c2–a2

mb = 1 2 √2a2+2c2–b2

mc = 1 2 √2a2+2b2–c2

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

Подобными называются фигуры, если одна из них представляет уменьшенную копию другой.

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

∆ABC ~ ∆A1B1C1

— треугольники ABC и A1B1C1

подобны.

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

Биссектрисы треугольника

Определение. Биссектриса угла — луч с началом в вершине угла, делящий угол на два равных угла.

Свойства биссектрис треугольника:

-

Биссектрисы треугольника пересекаются в одной точке, равноудаленной от трех сторон треугольника, – центре вписанной окружности.

-

Биссектриса треугольника делит противолежащую сторону на отрезки, пропорциональные прилежащим сторонам треугольника

-

Угол между биссектрисами внутреннего и внешнего углов треугольника при одной вершине равен 90°.

Угол между lc и lc‘ = 90°

-

Если в треугольнике две биссектрисы равны, то треугольник — равнобедренный.

Формулы биссектрис треугольника

Формулы биссектрис треугольника через стороны:

la = 2√bcp(p – a) b + c

lb = 2√acp(p – b) a + c

lc = 2√abp(p – c) a + b

где p = a + b + c 2 – полупериметр треугольника

Формулы биссектрис треугольника через две стороны и угол:

la = 2bc cos α 2 b + c

lb = 2ac cos β 2 a + c

lc = 2ab cos γ 2 a + b

Примеры наиболее часто встречающихся подобных треугольников

1. Прямая, параллельная стороне треугольника, отсекает от него треугольник, подобный данному.

2. Треугольники и

и , образованные отрезками диагоналей и основаниями трапеции, подобны. Коэффициент подобия –

3. В прямоугольном треугольнике высота, проведенная из вершины прямого угла, разбивает его на два треугольника, подобных исходному.

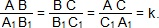

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком ~ обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

Взаимное расположение прямых

Две прямые в пространстве могут располагаться по-разному. Самый простой и частый случай это пересечение. Если две прямые имеют одну общую точку, про такие прямые говорят, что они пересекаются.

Рис. 2. Взаимное расположение прямых.

А как прямые назвать, если они не пересекаются? Тогда – параллельные, то есть прямые, которые не имеют общих точек.

А что будет, если у двух прямых две и больше общих точек? Тогда прямые совпадут.

При пересечении двух прямых образуется две пар вертикальных углов. Вертикальные углы в каждой паре равны между собой.

Если угол пересечения равен 90 градусов, то прямые перпендикулярны друг другу.

Рис. 3. Пересечение прямых.

Источники

- https://obrazovaka.ru/matematika/pryamaya-chasti-chto-takoe.html

- https://MicroExcel.ru/podobie-treugolnikov/

- https://MicroExcel.ru/treugolnik-figura/

- https://www.calc.ru/Ponyatiye-Pryamoy-Yee-Svoystva.html

- https://izamorfix.ru/matematika/planimetriya/pryamaya_liniya.html

- https://www.calc.ru/101.html

- https://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwiki/8313

- https://ru.onlinemschool.com/math/formula/triangle/

- https://egemaximum.ru/treugolnik/

- https://Sprint-Olympic.ru/uroki/geometrija/85548-znak-podobiia-v-geometrii-pravilo-i-primery-oboznacheniia.html

- https://egemaximum.ru/podobnye-treugolniki/

Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

Знак подобия в геометрии — правило и примеры обозначения

В учебниках по геометрии часто встречаются задачи на подобие фигур. Какой знак используется для обозначения подобия фигур? Какие фигуры называются подобными? Поговорим обо всем этом в нашей статье.

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

Подобными называются фигуры, если одна из них представляет уменьшенную копию другой.

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

∆A 1 B 1 C 1

— треугольники ABC и A1B1C1

подобны.

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком

обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

Признаки подобия прямоугольных треугольников

Острые углы: наличие равного острого угла в прямоугольных треугольниках делает их подобными.

Два катета: общая пропорциональность катетам одного прямоугольного треугольника к катетам второго делает их подобными.

Катет и гипотенуза: пропорциональность катета и гипотенузы одного прямоугольного треугольника к катету и гипотенузе второго прямоугольного треугольника делает их подобными.

треугольник ∆ABC и треугольник ∆A1B1C1 считаются подобными при равнозначности углов и пропорциональности сторон;

отношение площадей подобных треугольников равно квадрату коэффициента подобия.

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

Имеется треугольник ∆ABC, mn — средняя линия. M лежит на AB, N лежит на BC.

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN

∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Примеры решения задач по геометрии на тему «Подобие треугольников»

Источник

Знак подобия в геометрии — правило и примеры обозначения

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

Подобными называются фигуры, если одна из них представляет уменьшенную копию другой.

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

∆A 1 B 1 C 1

— треугольники ABC и A1B1C1

подобны.

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком

обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

Признаки подобия прямоугольных треугольников

Острые углы: наличие равного острого угла в прямоугольных треугольниках делает их подобными.

Два катета: общая пропорциональность катетам одного прямоугольного треугольника к катетам второго делает их подобными.

Катет и гипотенуза: пропорциональность катета и гипотенузы одного прямоугольного треугольника к катету и гипотенузе второго прямоугольного треугольника делает их подобными.

треугольник ∆ABC и треугольник ∆A1B1C1 считаются подобными при равнозначности углов и пропорциональности сторон;

отношение площадей подобных треугольников равно квадрату коэффициента подобия.

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

Имеется треугольник ∆ABC, mn — средняя линия. M лежит на AB, N лежит на BC.

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN

∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Примеры решения задач по геометрии на тему «Подобие треугольников»

Источник

В учебниках по геометрии часто встречаются задачи на подобие фигур. Какой знак используется для обозначения подобия фигур? Какие фигуры называются подобными? Поговорим обо всем этом в нашей статье.

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

На нижеприведенном рисунке подобные фигуры: круги, параллелограммы, пятиугольники и ромбы.

Для обозначения термина «подобие» в геометрии используют знак «тильда», который является типографским символом и обозначается волнистой чертой:

Знак «двойная тильда» ставится около чисел для демонстрации примерности или приблизительности чего-либо:

1,35 ≈ 1,4 — числа 1,35 и 1,4 приблизительно равны.

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Часто сверху знака подобия выставляют коэффициент подобия треугольников:

В математических задачах и уравнениях «тильду» используют для маркирования разных типов подобия. Часто применяется для обозначения подобия, эквивалентности.

В алгебре высказываний знаком

обозначают логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

При сочетании тильды и знака равенства получают обозначение отношения конгруэнтности, определения в геометрии, применяемого в контексте обозначения равенства различных фигур и тел (углов, отрезков):

Признаки подобия прямоугольных треугольников

Острые углы: наличие равного острого угла в прямоугольных треугольниках делает их подобными.

Два катета: общая пропорциональность катетам одного прямоугольного треугольника к катетам второго делает их подобными.

Катет и гипотенуза: пропорциональность катета и гипотенузы одного прямоугольного треугольника к катету и гипотенузе второго прямоугольного треугольника делает их подобными.

треугольник ∆ABC и треугольник ∆A1B1C1 считаются подобными при равнозначности углов и пропорциональности сторон;

отношение площадей подобных треугольников равно квадрату коэффициента подобия.

Доказательство подобия треугольников через среднюю линию

Требуется доказательство подобия треугольников ∆MBN и ∆ABC.

Посмотрев на ∆MBN и ∆ABC, видим, что угол В — общий, а отношение:

Отсюда делаем вывод, что ∆MBN

∆ABC по II признаку подобия треугольников, что и требовалось доказать.

Примеры решения задач по геометрии на тему «Подобие треугольников»

Источник

Глоссарий. Алгебра и геометрия

Два треугольника называются подобными, если их углы соответственно равны и стороны одного треугольника пропорциональны сходственным сторонам другого.

Другими словами, два треугольника подобны, если их можно обозначить буквами ABC и A1B1C1 так, что

Число k, равное отношению сходственных сторон треугольника называется коэффициентом подобия.

Подобие треугольников ABC и A1B1C1 обозначается так:

∆ A1B1C1. На рисунке 1 изображены подобные треугольники.

Источник

Знак в геометрии подобен – Знак подобия в геометрии

Знак подобия в геометрии

Определение и знак подобия в геометрии

Обозначают подобие треугольников знаком «».

Пример. (читают: треугольник подобен треугольнику ).

Коэффициент подобия треугольников и знак подобия

Знак «» представляет собой типографский знак «тильда», который изображается в виде волнистой черты. Этот знак может быть как надстрочным, так и междустрочным.

В математике «тильда» используется для обозначения различных видов отношений эквивалентности, в частности, отношения подобия.

Знак «тильда» (или «двойная тильда» ), который стоит перед числом может означать «примерно», «приблизительно равно».

В алгебре высказываний знак «» обозначает логическую операцию «эквиваленция».

Если знак «тильда» сочетать со знаком равенства: «», то он будет обозначать отношение конгруэнтности.

Также знак «тильда» активно используется в информатике и вычислительной технике. Например, в редакторе Tex этот знак означает «неразрывный пробел».

Знак подобия треугольников в геометрии — что значит «

» в геометрии? — 22 ответа

В разделе Школы на вопрос что значит «

» в геометрии? заданный автором Нету лучший ответ это Это знак «Приблизительно»

Ответ от 22 ответа[гуру]

Привет! Вот подборка тем с ответами на Ваш вопрос: что значит «

Ответ от Mitternacht[гуру]

Вроде приблизительно

Ответ от Невропатолог

Ответ от Недоносок[новичек]

Это значит приблизительно

Ответ от МiRaMih[гуру]

Подобие

Ответ от Антон Рзаханов[активный]

это знак подобия)) мы щас проходим)

Ответ от Hip-hop4live[гуру]

Подобие.

Ответ от Ёаша Рощин[активный]

Прекрасных комедий множество. Но одна из лучших «Не упускай из виду! » 1975г. с Пьером Ришаром.

Узнал об этом фильме у него на спектакле в Москве феврале в этом году. Решил посмотреть этот фильм, у меня была истерика, чуть упал под стол от смеха, особенно когда он бегал с унитазом на ноге )) А на самом спектакле Ришар такие байки травил, особенно про Депардье, что я реально устал смеяться )

Ответ от Влад Матвеев[новичек]

подобие

Ответ от Supreme[новичек]

Подобие )

Признаки подобия треугольников на Википедии

Посмотрите статью на википедии про Признаки подобия треугольников

Ответить на вопрос:

что значит «

точно не уверенна, но может подобие Для тех кто пишет приблизительно: знак приблизительности похож на знак =,только линии там волнистые, как в вопросе

Это значит приблизительно

это знак подобия)) мы щас проходим)

Это «тильда», она обозначает «подобие» в геометрии.

Что в Геометрий обозначает недорисованная, перевёрнутая 8-ка?

лежащая на боку 8 знак бесконечности …

Перевёрнутая восьмёрка выглядит также как обычная. Интеграл, параграф. Больше не знаю. У меня была тройка по геометрии (((

в геометрии такой знак обозначает подобие фигур

Я насколько помню так всю жизнь обозначали подобие, НО такого символа фактически нет. Это

и она не настолько загнута по краям, как её в школах рисовали.

Перевернутая восьмерка обозначает бесконечность

Как называется этот знак (Геометрия).

Дуга выгнута вверх? Тогда это знак пересечения. Если выгнута вниз — объединение…. Если я, конечно, вспомнила правильно

он так и называется дуга. а читается например дуга ОВ

Вероятно ето пересечение, если на U похоже.

Это значит точка О получается пересечением АВ и СД. Может это знак пересечения? Больше на ум ничего не идет, что смысл бы имело…

Если дуга выгнута вниз, значит это «дуга», а если вверх то «пересечение».

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как пишется знак подобия в геометрии, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как пишется знак подобия в геометрии», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.