Знак примерно (приблизительно) на клавиатуре: как набрать?

-

Категория ~

Технические советы -

– Автор:

Игорь (Администратор)

Любите ли вы математику или нет, но время от времени приходится использовать различные математические символы. И об одном из них, а конкретнее о знаке примерно (приблизительно), и пойдет речь. Более того, я расскажу вам несколько методов как его набрать на клавиатуре.

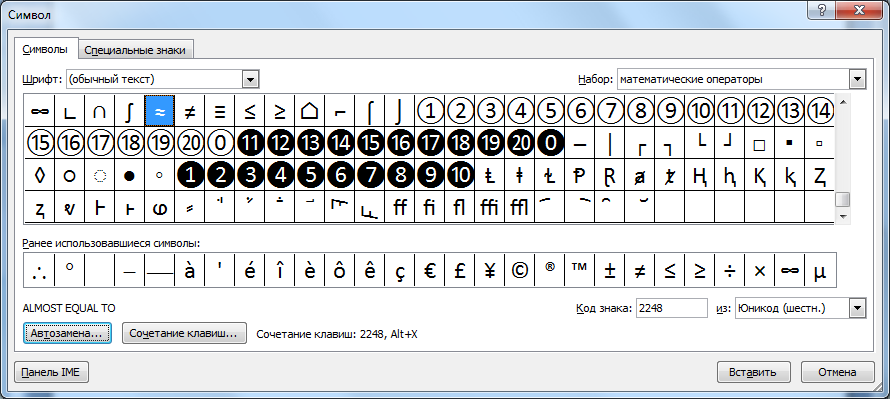

Знак примерно (приблизительно)

Знак примерно (приблизительно) или ≈ — это математический символ, который указывается между двумя примерно одинаковыми выражениями, при этом допускается некая доля погрешности. Например, выражение «4,99 ≈ 5» означает, что 4,99 это примерно 5.

Знак приблизительно обычно применяется в тех случаях, когда необходимо упростить расчеты или же когда важен порядок цифр, а не их точность. Утрированный пример для понимания. Допустим, статистика утверждает, что в среднем каждому человеку нужно 9,42 салфетки за один вечер «гулянки». В мероприятии под названием «вечеринка» должно участвовать 37 человек. Вам нужно посчитать сколько брать упаковок салфеток по 50 штук. Вы действительно будете умножать 9,42 на 37? Нет, конечно. Вы умножите 10 на 37. Получите 370. Округлите до 400 и разделите на 50. И возьмете 8 упаковок. И даже если 1 упаковка будет лишней (9,42 * 37 = 348,54 ≈ 350 = 50 * 7), то это же салфетки по 50 шт, а не по 500 000 шт.

Способы как набрать знак примерно (приблизительно) на клавиатуре

В жизни бывают разные ситуации, поэтому чем больше способов вы знаете, тем лучше. Как говорится, альтернатива никогда не будет лишней. Кстати, обзор в тему зачем нужны аналоги. Возвращаясь к сути, вот, собственно, несколько способов как набрать знак приблизительно (примерно) на клавиатуре.

Метод 1. Скопируйте знак примерно (приблизительно)

Зачем ждать? Если вам нужен символ, то самое простое и очевидное это просто скопировать его. Собственно, к тому как это сделать и переходим.

Вот знак примерно (приблизительно): ≈

Метод 2. Знак примерно (приблизительно) с помощью комбинаций на клавиатуре

Сразу отмечу, что данный способ далеко не везде и всегда приводит к нужному результату. И вот что нужно сделать.

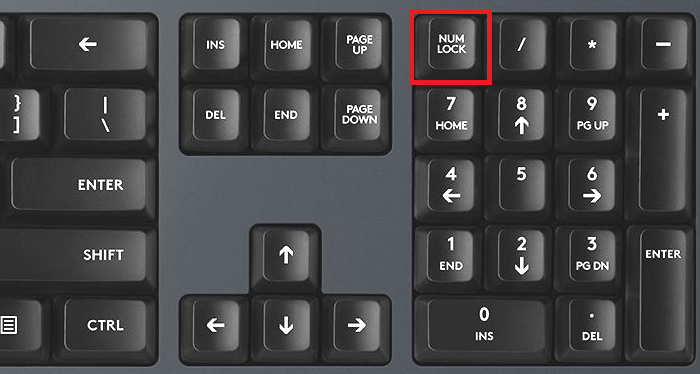

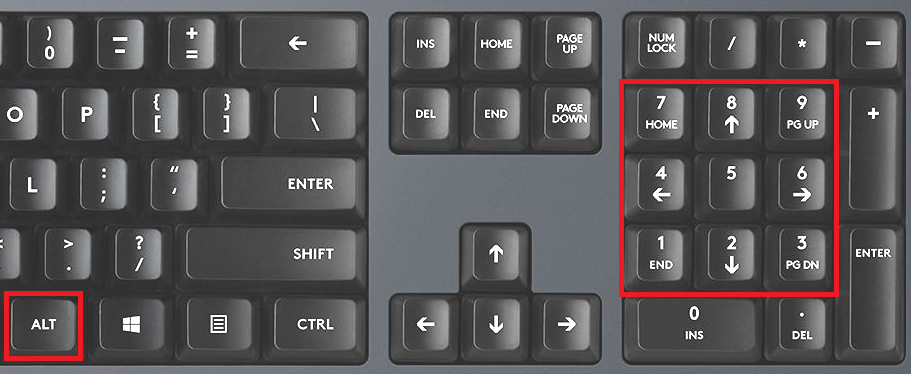

Чтобы набрать знак приблизительно (примерно), вам нужно зажать клавишу «Alt» и набрать «008776» или просто «8776» (в правой колодке клавиатуры). Должен появиться знак «≈«.

Метод 3. Знак примерно (приблизительно) с помощью таблицы символов Windows

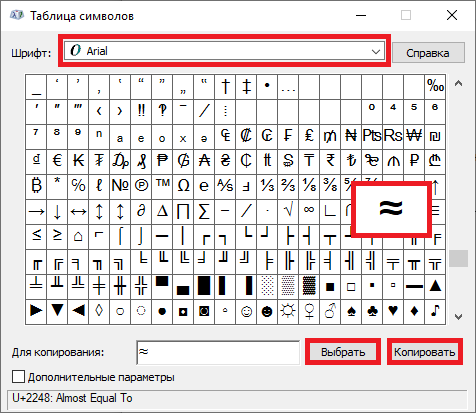

Знак примерно (приблизительно) можно набрать и с помощью классного инструмента Windows под названием Таблица символов, который позволяет найти нужный символ или знак. И вот что нужно делать:

1. Откройте меню Пуск и в поиске наберите «таблица символов».

2. Выберите пункт с одноименным названием.

3. Откроется окно с символами.

3.1. В нем можно либо вручную найти знак «примерно» — «≈«.

3.2. Либо можно сделать следующее.

3.2.1. Установите галочку напротив пункта «Дополнительные параметры».

3.2.2. Внизу в выпадающем списке «Группировка» выберите пункт «Диапазоны Юникода».

3.2.3. Откроется небольшое окно, в нем необходимо выбрать пункт «Математические операторы».

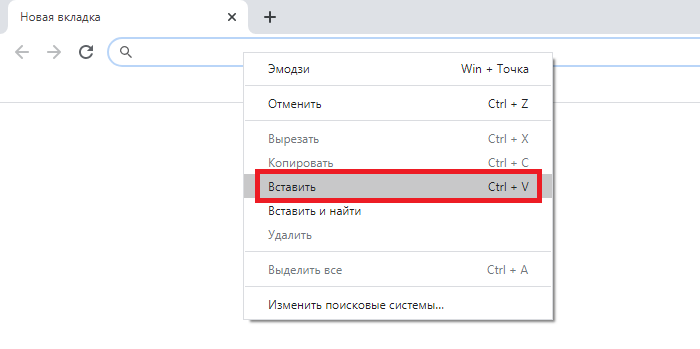

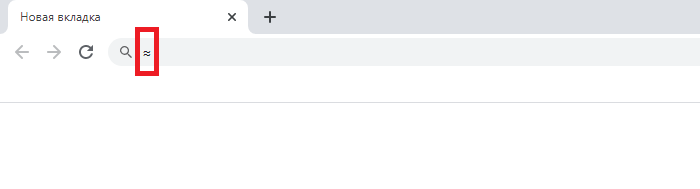

3.2.4. Теперь щелкните по знаку приблизительно «≈«. Затем нажмите кнопку «Выбрать» под таблицей и скопируйте символ из текстового поля рядом (или нажмите кнопку «копировать»).

3.2.5. Дальше вставьте знак «примерно» там, где вам необходимо.

Метод 4. Еще можно схитрить и набрать символ, похожий на знак примерно (приблизительно)

Смекалка это полезная вещь! К ней всегда стоит прибегать. Чего я сейчас и сделаю. На клавиатуре слева от кнопки «1» существует кнопка с символом «ё» в русской раскладке. В латинице это специфическая верхняя запятая — `. Если перевести раскладку в латиницу, одновременно нажать Shift и эту кнопку, то получится символ «тильда» — «~«, который отчасти похож на символ приблизительно. Вполне неплохой вариант для случаев, когда нужно быстро передать смысл.

Метод 5. Коды знака приблизительно (примерно) в html

А вот еще один метод на тот случай, если вам нужно набрать знак примерно в html. Скажем, в случае, когда вы пишите формулы. Соответственно вот сами коды.

Чтобы вставить знак примерно (приблизительно): ≈ и ≈

Понравилась заметка? Тогда время подписываться в социальных сетях и делать репосты!

☕ Понравился обзор? Поделитесь с друзьями!

-

Что такое Тема для сайта простыми словами?

Технические советы -

Знак умножения на клавиатуре: как набрать?

Технические советы -

Знак номера на клавиатуре: как набрать?

Технические советы -

Размеры форматов бумаги

Технические советы -

Как переместить папку Мои документы

Технические советы -

Как скрыть папку в Windows 7?

Технические советы

Добавить комментарий / отзыв

В некоторых случаях в тексте необходимо указать приблизительные, то есть примерные параметры. Можно указать это дело словом, однако можно использовать специальный символ, который в том числе поддерживает операционная система Windows. В этой статье — несколько способов, как поставить знак примерно (приблизительно) с помощью клавиатуры компьютера или ноутбука.

Первый способ

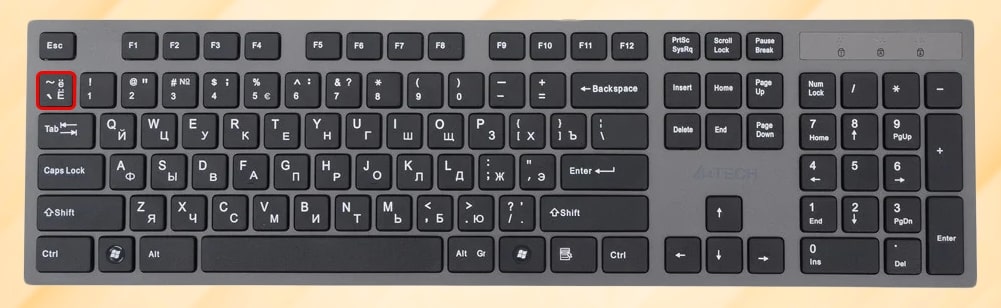

Скажем сразу — для этого способа мы будем использовать символ тильда в виде одной волнистой черты, в то время как в знаке приблизительно черты две. Тем менее, тильду часто используют в качестве символа примерно, так что проблем быть не должно.

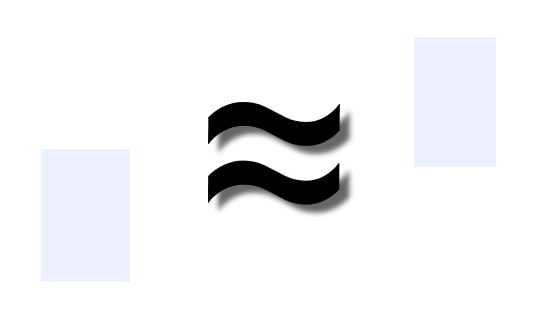

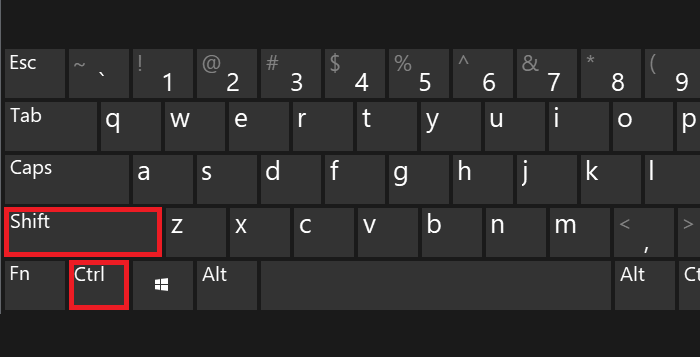

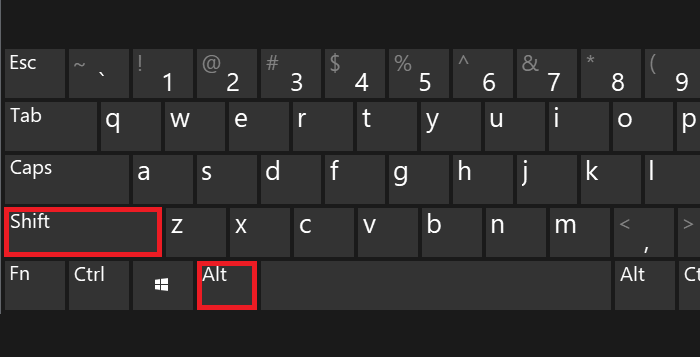

Используйте англоязычную раскладку. Если используется русскоязычная, переключите ее, нажав Shift+Ctrl:

Или Shift+Alt:

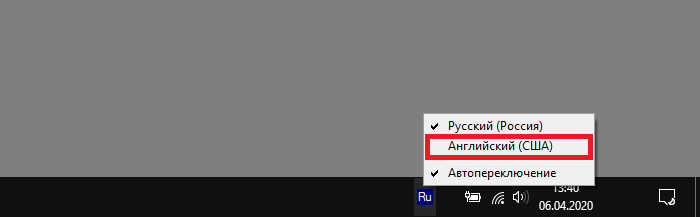

Или используйте языковую иконку, которая находится на панели задач:

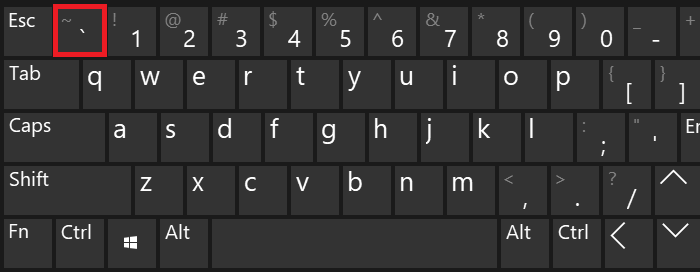

Теперь найдите символ тильды (слева от цифры 1, часто на этой же клавише можно увидеть букву ё).

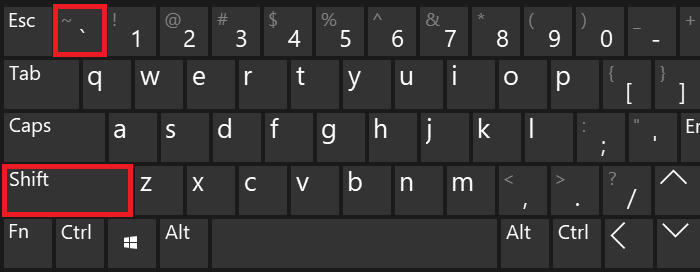

Однако если нажать на указанную клавишу, вы увидите совсем другой символ, поэтому предварительно нажмите на Shift и, удерживая его, нажмите на клавишу тильда, после чего отпустите Shift.

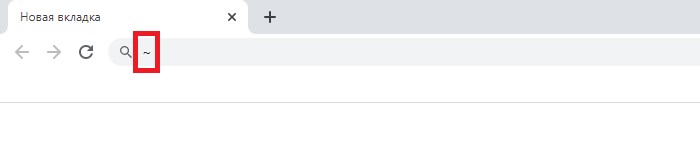

Что у вас должно получиться:

Второй способ

Если вам нужны исключительно две волнистые черты, их тоже можно поставить, но способ чуть более долгий.

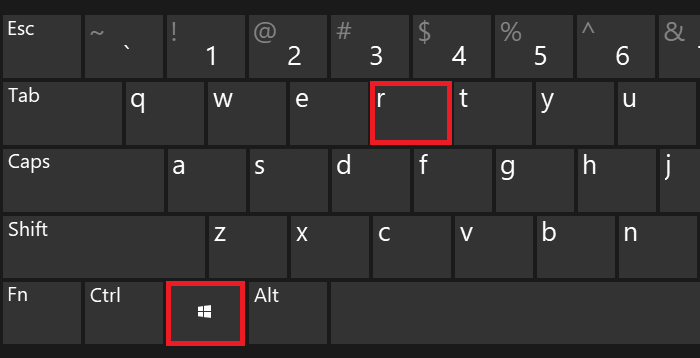

На клавиатуре своего устройства нажмите Win+R.

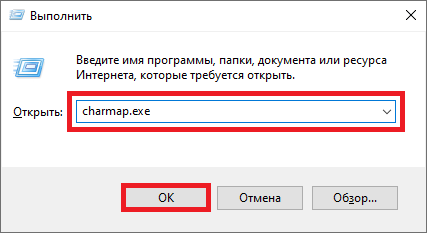

Появится окно «Выполнить». Добавьте команду charmap.exe, нажмите ОК.

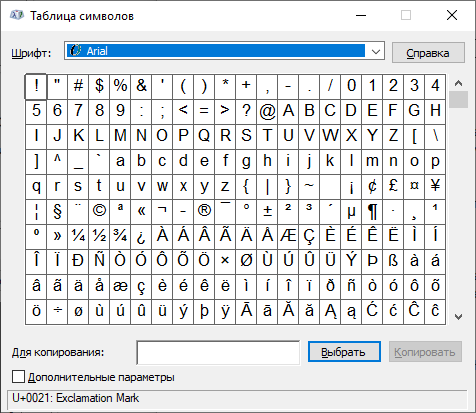

Запущена таблица символов Windows.

Выбираете шрифт Arial, затем в списке находите символ приблизительно (примерно), нажимаете на него левой клавишей мыши, а затем по очереди — на кнопки «Выбрать» и «Копировать».

Теперь вставляете символ в определенное место вашего текста.

Готово.

Третий способ

Работает только в некоторых текстовых редакторах, включая Word.

Включите цифровую клавиатуру, что находится в правой части основной клавиатуры, с помощью клавиши Num Lock.

Зажмите Alt и, удерживая, введите цифру 008776. После отпустите Alt.

Если не получилось с правым Alt, повторите действие, но с левым Alt.

Четвертый способ

Скопируйте символ из этой строки — ≈.

В разделе собраны математические символы, которые невозможно корректно отобразить с помощью ввода на клавиатуре. Весь представленный набор можно разделить на несколько групп:

- знаки операций – сложение, вычитание, деление, умножение, сумма;

- символы интегралов – двойные, тройные, интеграл по объему, поверхности, с правым и левым обходом;

- знаки сравнения – больше, меньше;

- примерно равно, не равно, эквивалентно, тождественно;

- геометрические символы – отображение угла, пропорции, диаметра, перпендикуляра, параллельности, пересечения;

- геометрические фигуры — треугольники, дуги, параллелограмм, ромб;

- знак извлечения из корня, степень числа;

- для теории множеств — пустое множество, принадлежит, подмножество, объединение, пересечение;

- логические — следовательно, и, или, отрицание, равносильно;

- иные символы – бесконечность, существует, принадлежит, оператор набла, троеточия для матриц, скобки потолков числа, для теории групп.

Примеры использования

Функция параболы: ƒ(x)=ax²+bx+c (a≠0)

Определение исключающего «ИЛИ»: A⊕B :⇔ (A⋁B) ∧¬ (A∧B)

Скорость, с которой упадет тело с высоты h: V=√̅2̅g̅h̅

Использование данных иконок – единственный вариант корректного отображения ряда математических символов на сайте или в сообщении в любой операционной системе конечного пользователя. Достаточно лишь скопировать закодированный значок. Применение изображений для этих целей значительно усложняет процесс, требует подгонки при разработке и наполнении интернет-ресурса. Кроме того, медиа-контент занимает большой объем дискового пространства.

Математические символы подойдут для публикаций в социальных сетях, создания сообщений в чатах и форумах, разработки интернет-страниц.

Математика, как язык всех наук, не может обходиться без системы записи. Многочисленные понятия, и операторы обрели своё начертание по мере развития этой науки. Так как в стандартные алфавиты эти символы не входят, напечатать их с клавиатуры может оказаться проблематично. Отсюда можно скопировать и вставить.

Консорциум Юникода включил в таблицу множество различных знаков. Если тут нет того, что нужно, воспользуйтесь поиском по сайту или посмотрите в разделах:

Математические операторы 2200–22FF

Разные математические символы — A 27C0–27EF

Разные математические символы — B 2980–29FF

Дополнительные математические операторы 2A00–2AFF

Буквы для формул:

Греческое и коптское письмо 0370–03FF

Математические буквы и цифры 1D400–1D7FF

Степени и дроби

Для степеней числа используются Подстрочные и надстрочные цифры. Мы собрали их в отдельный набор. В этом же наборе собраны дроби.

Инструкция для компьютеров и ноутбуков

В зависимости от версии вашей операционной системы, способ вставки нужного символа будет различаться. По этой причине мы подготовили 2 руководства: для Windows и для macOS (MacBook, Mac Pro и iMac). Переходите к соответствующему подразделу и изучайте наши рекомендации.

Windows

В стандартной раскладке этот знак находится на том же месте, где буква Ё. Это левый верхний угол, под клавишей Esc.

Для ввода значка приблизительно в текст вам сначала нужно перейти к английскому языку набора, а уже потом зажать Shift и один раз щелкнуть по соответствующей клавише. С русским языком это не сработает, вместо нужного значка появится строчная буква Ё.

Как правило, смена раскладки установлена на сочетание Shift + Alt. А еще это можно сделать на языковой панели рядом с индикатором времени и даты в углу экрана.

Второй удобный способ – использование Alt-кодов. Он будет работать с любой раскладкой. Для такого значка приблизительно (~) код Alt + 126. Вводится он предельно просто:

-

Зажмите любую клавишу Alt и не отпускайте ее до самого конца.

-

С помощью цифрового блока, который легко найти в правой части клавиатуры, по очереди нажмите на числа 1, 2 и 6.

-

А уже теперь снимите палец с Alt.

Но учтите, что этот способ может не сработать, если у вас отключен индикатор NumLock, который и отвечает за использование цифрового блока.

А еще с помощью Alt-кода можно ввести альтернативный вариант символа – ≈. Для его добавления воспользуйтесь кодом Alt + 247.

Универсальный способ, чтобы поставить знак, заключается в копировании из одного места, например, с нашего сайта, и последующей вставки. Сделать это получится как для Windows, так и для macOS. Проще всего воспользоваться горячими клавишами клавиатуры, но также подойдет и мышка.

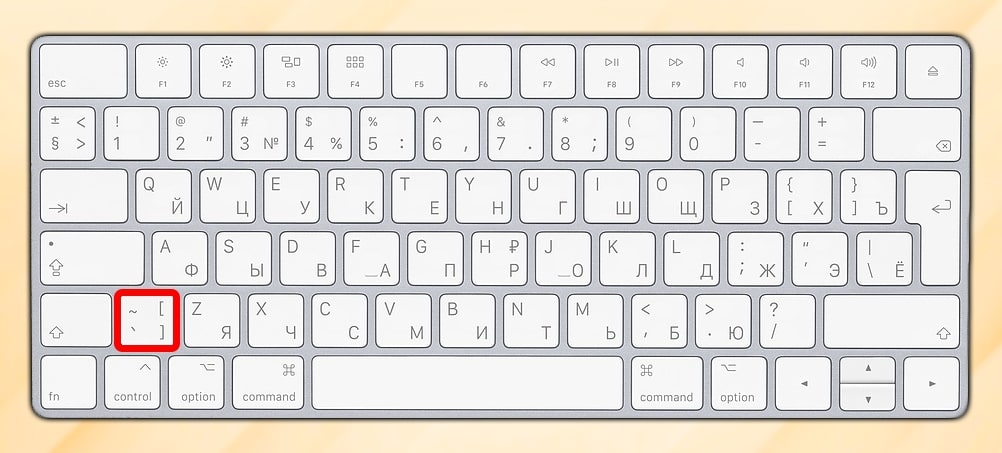

macOS

На компьютерах и ноутбуках фирмы Apple используется оригинальная клавиатура, раскладка и вид которой несколько отличается от моделей, изначально предназначенных для Windows. Да и способы ввода спецсимволов в случае с операционной системой macOS будут другими.

Знак приблизительно (~) на фирменной клавиатуре Apple находится между левым Шифтом и буквой Я, на той же клавише, где и фигурные скобки ([]).

Пользоваться им получится только после переключения языка ввода на английский. С зажатым левым или правым Shift щелкните на выделенную выше клавишу, чтобы поставить нужный знак в тексте.

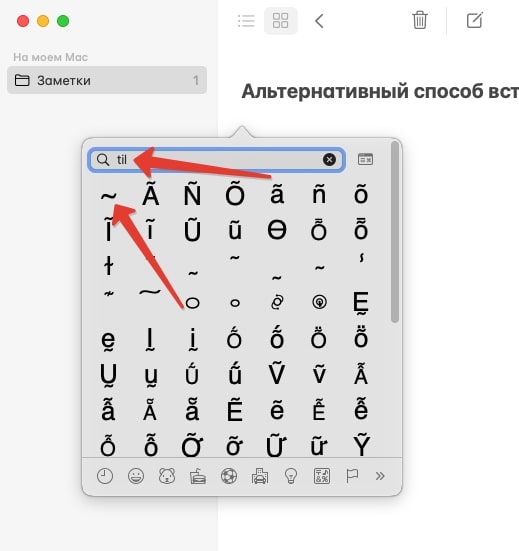

Заодно упомянем встроенный в macOS инструмент вставки спецсимволов. Вызывается он хоткеем Command + Ctrl + Пробел во время набора текста с любым шрифтом. В поле поиска таблицы введите til и кликните по соответствующему значку, чтобы он появился в тексте.

Если же вы хотите получить ≈, то воспользуйтесь сочетанием Option + X.

Ну и не забывайте про вариант с копированием и вставкой, который был упомянут в предыдущей части статьи.

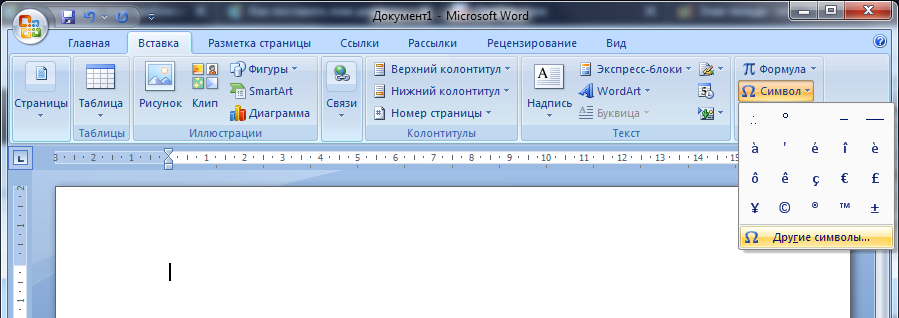

Офисный пакет Microsoft Office (редактор Word и таблицы Excel)

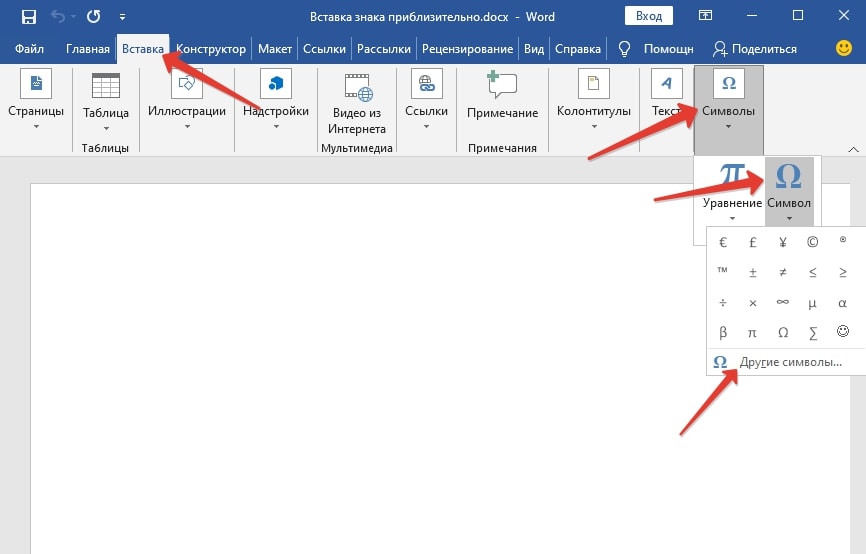

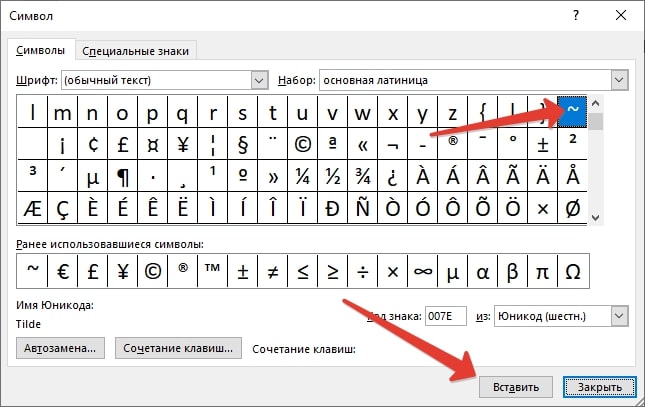

В Microsoft Word и Excel добавлено специальное меню для быстрой вставки символов. Чтобы добраться до него, разверните вкладку Вставка на верхней панели, нажмите на элемент Символ и выберите Другие.

Ориентируясь по иконкам, отыщите нужную, выделите ее кликом мыши и нажмите Вставить.

А еще можно воспользоваться функцией поиска по коду:

-

~ – 007E

-

≈ – 2248

Заключительный способ – быстрая замена символов комбинацией Alt + X. Вам нужно ввести один из предложенных выше кодов в текст документа Microsoft Word и сразу же после нажать сочетание Alt + X, тогда произойдет замена. При этом важно не делать никаких пробелов, чтобы мигающая черточка набора стояла после последнего символа.

Инструкция для мобильных устройств

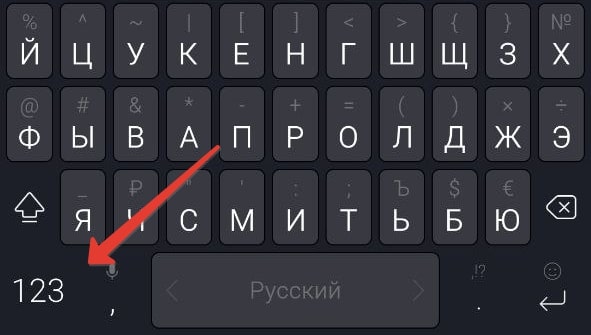

На мобильных устройствах основной метод ввода – виртуальная клавиатура. И далеко не всем очевидно, как с ее помощью проставить в текст значок приблизительно. Мы расскажем способы вставки по отдельности для Айфона и телефонов под управлением Андроид.

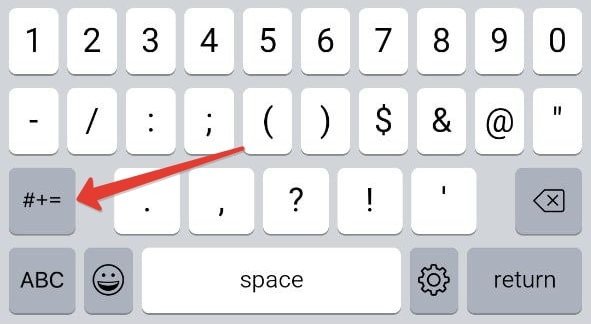

Способ для Айфона

Если вы пользуетесь стандартным приложением клавиатуры, то нажмите на выделенную иконку для переключения на панель с цифрами.

Теперь переключитесь на панель с символами.

Здесь вы и найдете нужный математический значок.

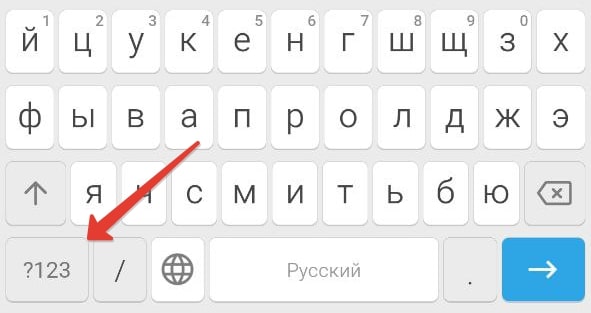

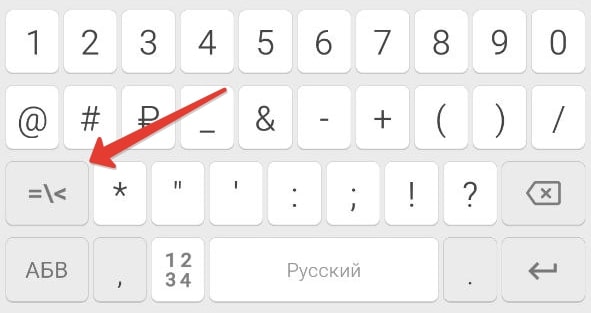

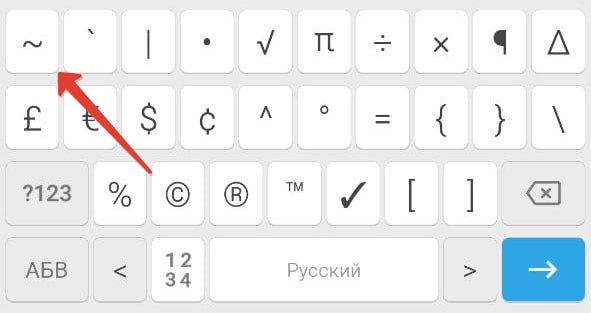

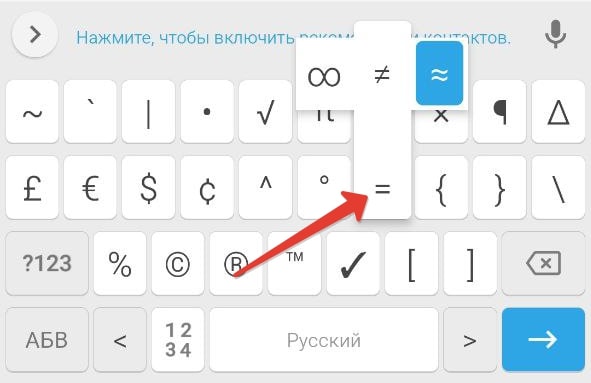

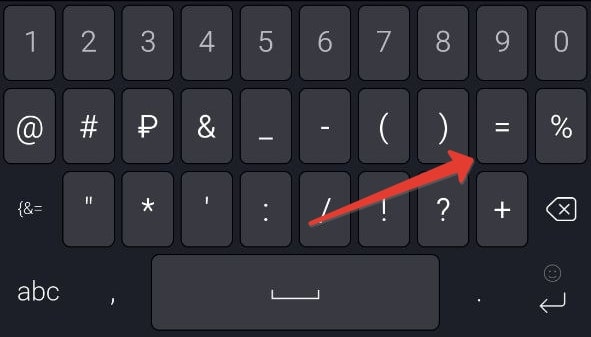

Способ для телефонов на Андроиде

У разных смартфонов под управлением Android по умолчанию установлены разные клавиатуры. Кроме того, пользователи сами могут выбирать альтернативные приложения. Самое популярное из них – это Gboard, фирменная клавиатура от Google. Она несколько похожа на приложение Samsung.

Чтобы поставить знак:

-

Нажмите на иконку с надписью ?123 в левом нижнем углу.

-

Переключитесь на страницу расширенного набора с помощью отмеченной иконки.

-

Нажмите на нужный символ, расположенный слева сверху.

Если вы хотите вставить ≈, то зажмите знак равно (=) и сдвиньте ползунок выбора вправо.

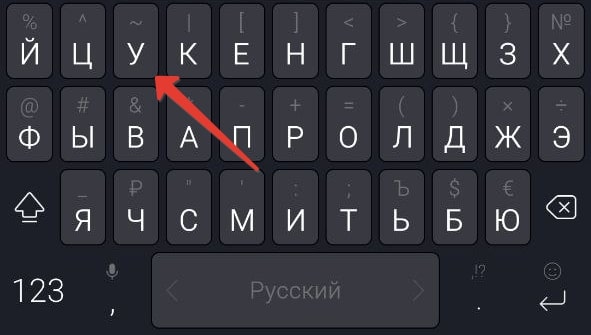

В случае с Microsoft SwiftKey нужный символ находится на букве У в русской раскладке.

А для вставки ≈ включите панель с цифрами.

А затем зажмите пальцем знак равно (=).

A mathematical symbol is a figure or a combination of figures that is used to represent a mathematical object, an action on mathematical objects, a relation between mathematical objects, or for structuring the other symbols that occur in a formula. As formulas are entirely constituted with symbols of various types, many symbols are needed for expressing all mathematics.

The most basic symbols are the decimal digits (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), and the letters of the Latin alphabet. The decimal digits are used for representing numbers through the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. Historically, upper-case letters were used for representing points in geometry, and lower-case letters were used for variables and constants. Letters are used for representing many other sorts of mathematical objects. As the number of these sorts has remarkably increased in modern mathematics, the Greek alphabet and some Hebrew letters are also used. In mathematical formulas, the standard typeface is italic type for Latin letters and lower-case Greek letters, and upright type for upper case Greek letters. For having more symbols, other typefaces are also used, mainly boldface

The use of Latin and Greek letters as symbols for denoting mathematical objects is not described in this article. For such uses, see Variable (mathematics) and List of mathematical constants. However, some symbols that are described here have the same shape as the letter from which they are derived, such as

These letters alone are not sufficient for the needs of mathematicians, and many other symbols are used. Some take their origin in punctuation marks and diacritics traditionally used in typography; others by deforming letter forms, as in the cases of

Layout of this article[edit]

Normally, entries of a glossary are structured by topics and sorted alphabetically. This is not possible here, as there is no natural order on symbols, and many symbols are used in different parts of mathematics with different meanings, often completely unrelated. Therefore, some arbitrary choices had to be made, which are summarized below.

The article is split into sections that are sorted by an increasing level of technicality. That is, the first sections contain the symbols that are encountered in most mathematical texts, and that are supposed to be known even by beginners. On the other hand, the last sections contain symbols that are specific to some area of mathematics and are ignored outside these areas. However, the long section on brackets has been placed near to the end, although most of its entries are elementary: this makes it easier to search for a symbol entry by scrolling.

Most symbols have multiple meanings that are generally distinguished either by the area of mathematics where they are used or by their syntax, that is, by their position inside a formula and the nature of the other parts of the formula that are close to them.

As readers may not be aware of the area of mathematics to which is related the symbol that they are looking for, the different meanings of a symbol are grouped in the section corresponding to their most common meaning.

When the meaning depends on the syntax, a symbol may have different entries depending on the syntax. For summarizing the syntax in the entry name, the symbol

Most symbols have two printed versions. They can be displayed as Unicode characters, or in LaTeX format. With the Unicode version, using search engines and copy-pasting are easier. On the other hand, the LaTeX rendering is often much better (more aesthetic), and is generally considered a standard in mathematics. Therefore, in this article, the Unicode version of the symbols is used (when possible) for labelling their entry, and the LaTeX version is used in their description. So, for finding how to type a symbol in LaTeX, it suffices to look at the source of the article.

For most symbols, the entry name is the corresponding Unicode symbol. So, for searching the entry of a symbol, it suffices to type or copy the Unicode symbol into the search textbox. Similarly, when possible, the entry name of a symbol is also an anchor, which allows linking easily from another Wikipedia article. When an entry name contains special characters such as [, ], and |, there is also an anchor, but one has to look at the article source to know it.

Finally, when there is an article on the symbol itself (not its mathematical meaning), it is linked to in the entry name.

Arithmetic operators[edit]

- +

- 1. Denotes addition and is read as plus; for example, 3 + 2.

- 2. Denotes that a number is positive and is read as plus. Redundant, but sometimes used for emphasizing that a number is positive, specially when other numbers in the context are or may be negative; for example, +2.

- 3. Sometimes used instead of

for a disjoint union of sets.

- –

- 1. Denotes subtraction and is read as minus; for example, 3 – 2.

- 2. Denotes the additive inverse and is read as negative or the opposite of; for example, –2.

- 3. Also used in place of for denoting the set-theoretic complement; see in § Set theory.

- ×

- 1. In elementary arithmetic, denotes multiplication, and is read as times; for example, 3 × 2.

- 2. In geometry and linear algebra, denotes the cross product.

- 3. In set theory and category theory, denotes the Cartesian product and the direct product. See also × in § Set theory.

- ·

- 1. Denotes multiplication and is read as times; for example, 3 ⋅ 2.

- 2. In geometry and linear algebra, denotes the dot product.

- 3. Placeholder used for replacing an indeterminate element. For example, «the absolute value is denoted | · |» is clearer than saying that it is denoted as | |.

- ±

- 1. Denotes either a plus sign or a minus sign.

- 2. Denotes the range of values that a measured quantity may have; for example, 10 ± 2 denotes an unknown value that lies between 8 and 12.

- ∓

- Used paired with ±, denotes the opposite sign; that is, + if ± is –, and – if ± is +.

- ÷

- Widely used for denoting division in anglophone countries, it is no longer in common use in mathematics and its use is «not recommended».[1] In some countries, it can indicate subtraction.

- :

- 1. Denotes the ratio of two quantities.

- 2. In some countries, may denote division.

- 3. In set-builder notation, it is used as a separator meaning «such that»; see {□ : □}.

- /

- 1. Denotes division and is read as divided by or over. Often replaced by a horizontal bar. For example, 3 / 2 or

.

- 2. Denotes a quotient structure. For example, quotient set, quotient group, quotient category, etc.

- 3. In number theory and field theory,

denotes a field extension, where F is an extension field of the field E.

- 4. In probability theory, denotes a conditional probability. For example,

denotes the probability of A, given that B occurs. Also denoted

: see «|«.

- √

- Denotes square root and is read as the square root of. Rarely used in modern mathematics without a horizontal bar delimiting the width of its argument (see the next item). For example, √2.

- √

- 1. Denotes square root and is read as the square root of. For example,

.

- 2. With an integer greater than 2 as a left superscript, denotes an nth root. For example,

.

- ^

- 1. Exponentiation is normally denoted with a superscript. However,

is often denoted x^y when superscripts are not easily available, such as in programming languages (including LaTeX) or plain text emails.

- 2. Not to be confused with ∧.

Equality, equivalence and similarity[edit]

- =

- 1. Denotes equality.

- 2. Used for naming a mathematical object in a sentence like «let

«, where E is an expression. On a blackboard and in some mathematical texts, this may be abbreviated as

or

This is related to the concept of assignment in computer science, which is variously denoted (depending on the programming language used)

- ≠

- Denotes inequality and means «not equal».

- ≈

- Means «is approximately equal to». For example,

(for a more accurate approximation, see pi).

- ~

- 1. Between two numbers, either it is used instead of ≈ to mean «approximatively equal», or it means «has the same order of magnitude as».

- 2. Denotes the asymptotic equivalence of two functions or sequences.

- 3. Often used for denoting other types of similarity, for example, matrix similarity or similarity of geometric shapes.

- 4. Standard notation for an equivalence relation.

- 5. In probability and statistics, may specify the probability distribution of a random variable. For example,

means that the distribution of the random variable X is standard normal.[2]

- 6. Notation for showing proportionality. See also ∝ for a less ambiguous symbol.

- ≡

- 1. Denotes an identity, that is, an equality that is true whichever values are given to the variables occurring in it.

- 2. In number theory, and more specifically in modular arithmetic, denotes the congruence modulo an integer.

- 1. May denote an isomorphism between two mathematical structures, and is read as «is isomorphic to».

- 2. In geometry, may denote the congruence of two geometric shapes (that is the equality up to a displacement), and is read «is congruent to».

Comparison[edit]

- <

- 1. Strict inequality between two numbers; means and is read as «less than».

- 2. Commonly used for denoting any strict order.

- 3. Between two groups, may mean that the first one is a proper subgroup of the second one.

- >

- 1. Strict inequality between two numbers; means and is read as «greater than».

- 2. Commonly used for denoting any strict order.

- 3. Between two groups, may mean that the second one is a proper subgroup of the first one.

- ≤

- 1. Means «less than or equal to». That is, whatever A and B are, A ≤ B is equivalent to A < B or A = B.

- 2. Between two groups, may mean that the first one is a subgroup of the second one.

- ≥

- 1. Means «greater than or equal to». That is, whatever A and B are, A ≥ B is equivalent to A > B or A = B.

- 2. Between two groups, may mean that the second one is a subgroup of the first one.

- ≪ , ≫

- 1. Means «much less than» and «much greater than». Generally, much is not formally defined, but means that the lesser quantity can be neglected with respect to the other. This is generally the case when the lesser quantity is smaller than the other by one or several orders of magnitude.

- 2. In measure theory,

means that the measure

is absolutely continuous with respect to the measure

.

- ≦

- 1. A rarely used synonym of ≤. Despite the easy confusion with ≤, some authors use it with a different meaning.

- ≺ , ≻

- Often used for denoting an order or, more generally, a preorder, when it would be confusing or not convenient to use < and >.

Set theory[edit]

- ∅

- Denotes the empty set, and is more often written

. Using set-builder notation, it may also be denoted

.

- #

- 1. Number of elements:

may denote the cardinality of the set S. An alternative notation is

; see

.

- 2. Primorial:

denotes the product of the prime numbers that are not greater than n.

- 3. In topology,

denotes the connected sum of two manifolds or two knots.

- ∈

- Denotes set membership, and is read «in» or «belongs to». That is,

means that x is an element of the set S.

- ∉

- Means «not in». That is,

means

.

- ⊂

- Denotes set inclusion. However two slightly different definitions are common.

- 1.

may mean that A is a subset of B, and is possibly equal to B; that is, every element of A belongs to B; in formula,

.

- 2.

may mean that A is a proper subset of B, that is the two sets are different, and every element of A belongs to B; in formula,

.

- ⊆

means that A is a subset of B. Used for emphasizing that equality is possible, or when the second definition of

is used.

- ⊊

means that A is a proper subset of B. Used for emphasizing that

, or when the first definition of

is used.

- ⊃, ⊇, ⊋

- Denote the converse relation of

,

, and

respectively. For example,

is equivalent to

.

- ∪

- Denotes set-theoretic union, that is,

is the set formed by the elements of A and B together. That is,

.

- ∩

- Denotes set-theoretic intersection, that is,

is the set formed by the elements of both A and B. That is,

.

- ∖

- Set difference; that is,

is the set formed by the elements of A that are not in B. Sometimes,

is used instead; see – in § Arithmetic operators.

- ⊖ or

- Symmetric difference: that is,

or

is the set formed by the elements that belong to exactly one of the two sets A and B.

- ∁

- 1. With a subscript, denotes a set complement: that is, if

, then

.

- 2. Without a subscript, denotes the absolute complement; that is,

, where U is a set implicitly defined by the context, which contains all sets under consideration. This set U is sometimes called the universe of discourse.

- ×

- See also × in § Arithmetic operators.

- 1. Denotes the Cartesian product of two sets. That is,

is the set formed by all pairs of an element of A and an element of B.

- 2. Denotes the direct product of two mathematical structures of the same type, which is the Cartesian product of the underlying sets, equipped with a structure of the same type. For example, direct product of rings, direct product of topological spaces.

- 3. In category theory, denotes the direct product (often called simply product) of two objects, which is a generalization of the preceding concepts of product.

- ⊔

- Denotes the disjoint union. That is, if A and B are sets then

is a set of pairs where iA and iB are distinct indices discriminating the members of A and B in

.

- ∐

- 1. An alternative to

.

- 2. Denotes the coproduct of mathematical structures or of objects in a category.

Basic logic[edit]

Several logical symbols are widely used in all mathematics, and are listed here. For symbols that are used only in mathematical logic, or are rarely used, see List of logic symbols.

- ¬

- Denotes logical negation, and is read as «not». If E is a logical predicate,

is the predicate that evaluates to true if and only if E evaluates to false. For clarity, it is often replaced by the word «not». In programming languages and some mathematical texts, it is sometimes replaced by «~» or «!«, which are easier to type on some keyboards.

- ∨

- 1. Denotes the logical or, and is read as «or». If E and F are logical predicates,

is true if either E, F, or both are true. It is often replaced by the word «or».

- 2. In lattice theory, denotes the join or least upper bound operation.

- 3. In topology, denotes the wedge sum of two pointed spaces.

- ∧

- 1. Denotes the logical and, and is read as «and». If E and F are logical predicates,

is true if E and F are both true. It is often replaced by the word «and» or the symbol «&«.

- 2. In lattice theory, denotes the meet or greatest lower bound operation.

- 3. In multilinear algebra, geometry, and multivariable calculus, denotes the wedge product or the exterior product.

- ⊻

- Exclusive or: if E and F are two Boolean variables or predicates,

denotes the exclusive or. Notations E XOR F and

are also commonly used; see ⊕.

- ∀

- 1. Denotes universal quantification and is read as «for all». If E is a logical predicate,

means that E is true for all possible values of the variable x.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «for all» or «for every».

- ∃

- 1. Denotes existential quantification and is read «there exists … such that». If E is a logical predicate,

means that there exists at least one value of x for which E is true.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «there exists».

- ∃!

- Denotes uniqueness quantification, that is,

means «there exists exactly one x such that P (is true)». In other words,

is an abbreviation of

.

- ⇒

- 1. Denotes material conditional, and is read as «implies». If P and Q are logical predicates,

means that if P is true, then Q is also true. Thus,

is logically equivalent with

.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «implies».

- ⇔

- 1. Denotes logical equivalence, and is read «is equivalent to» or «if and only if». If P and Q are logical predicates,

is thus an abbreviation of

, or of

.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «if and only if».

- ⊤

- 1.

denotes the logical predicate always true.

- 2. Denotes also the truth value true.

- 3. Sometimes denotes the top element of a bounded lattice (previous meanings are specific examples).

- 4. For the use as a superscript, see □⊤.

- ⊥

- 1.

denotes the logical predicate always false.

- 2. Denotes also the truth value false.

- 3. Sometimes denotes the bottom element of a bounded lattice (previous meanings are specific examples).

- 4. In Cryptography often denotes an error in place of a regular value.

- 5. For the use as a superscript, see □⊥.

- 6. For the similar symbol, see

.

Blackboard bold[edit]

The blackboard bold typeface is widely used for denoting the basic number systems. These systems are often also denoted by the corresponding uppercase bold letter. A clear advantage of blackboard bold is that these symbols cannot be confused with anything else. This allows using them in any area of mathematics, without having to recall their definition. For example, if one encounters

- Denotes the set of natural numbers

, or sometimes

. It is often denoted also by

. When the distinction is important and readers might assume either definition,

and

are used, respectively, to denote one of them unambiguously.

- Denotes the set of integers

. It is often denoted also by

.

- 1. Denotes the set of p-adic integers, where p is a prime number.

- 2. Sometimes,

denotes the integers modulo n, where n is an integer greater than 0. The notation

is also used, and is less ambiguous.

- Denotes the set of rational numbers (fractions of two integers). It is often denoted also by

.

- Denotes the set of p-adic numbers, where p is a prime number.

- Denotes the set of real numbers. It is often denoted also by

.

- Denotes the set of complex numbers. It is often denoted also by

.

- Denotes the set of quaternions. It is often denoted also by

.

- Denotes the finite field with q elements, where q is a prime power (including prime numbers). It is denoted also by GF(q).

- Used on rare occasions to denote the set of octonions. It is often denoted also by

.

Calculus[edit]

- □‘

- Lagrange’s notation for the derivative: If f is a function of a single variable,

, read as «f prime», is the derivative of f with respect to this variable. The second derivative is the derivative of

, and is denoted

.

- Newton’s notation, most commonly used for the derivative with respect to time: If x is a variable depending on time, then

is its derivative with respect to time. In particular, if x represents a moving point, then

is its velocity.

- Newton’s notation, for the second derivative: If x is a variable that represents a moving point, then

is its acceleration.

- d □/d □

- Leibniz’s notation for the derivative, which is used in several slightly different ways.

- 1. If y is a variable that depends on x, then

, read as «d y over d x», is the derivative of y with respect to x.

- 2. If f is a function of a single variable x, then

is the derivative of f, and

is the value of the derivative at a.

- 3. Total derivative: If

is a function of several variables that depend on x, then

is the derivative of f considered as a function of x. That is,

.

- ∂ □/∂ □

- Partial derivative: If

is a function of several variables,

is the derivative with respect to the ith variable considered as an independent variable, the other variables being considered as constants.

- 𝛿 □/𝛿 □

- Functional derivative: If

is a functional of several functions,

is the functional derivative with respect to the nth function considered as an independent variable, the other functions being considered constant.

- 1. Complex conjugate: If z is a complex number, then

is its complex conjugate. For example,

.

- 2. Topological closure: If S is a subset of a topological space T, then

is its topological closure, that is, the smallest closed subset of T that contains S.

- 3. Algebraic closure: If F is a field, then

is its algebraic closure, that is, the smallest algebraically closed field that contains F. For example,

is the field of all algebraic numbers.

- 4. Mean value: If x is a variable that takes its values in some sequence of numbers S, then

may denote the mean of the elements of S.

- →

- 1.

denotes a function with domain A and codomain B. For naming such a function, one writes

, which is read as «f from A to B«.

- 2. More generally,

denotes a homomorphism or a morphism from A to B.

- 3. May denote a logical implication. For the material implication that is widely used in mathematics reasoning, it is nowadays generally replaced by ⇒. In mathematical logic, it remains used for denoting implication, but its exact meaning depends on the specific theory that is studied.

- 4. Over a variable name, means that the variable represents a vector, in a context where ordinary variables represent scalars; for example,

. Boldface (

) or a circumflex (

) are often used for the same purpose.

- 5. In Euclidean geometry and more generally in affine geometry,

denotes the vector defined by the two points P and Q, which can be identified with the translation that maps P to Q. The same vector can be denoted also

; see Affine space.

- ↦

- Used for defining a function without having to name it. For example,

is the square function.

- ○[4]

- 1. Function composition: If f and g are two functions, then

is the function such that

for every value of x.

- 2. Hadamard product of matrices: If A and B are two matrices of the same size, then

is the matrix such that

. Possibly,

is also used instead of ⊙ for the Hadamard product of power series.[citation needed]

- ∂

- 1. Boundary of a topological subspace: If S is a subspace of a topological space, then its boundary, denoted

, is the set difference between the closure and the interior of S.

- 2. Partial derivative: see ∂□/∂□.

- ∫

- 1. Without a subscript, denotes an antiderivative. For example,

.

- 2. With a subscript and a superscript, or expressions placed below and above it, denotes a definite integral. For example,

.

- 3. With a subscript that denotes a curve, denotes a line integral. For example,

, if r is a parametrization of the curve C, from a to b.

- ∮

- Often used, typically in physics, instead of

for line integrals over a closed curve.

- ∬, ∯

- Similar to

and

for surface integrals.

or

- Nabla, the gradient or vector derivative operator

, also called del or grad.

- ∇2 or ∇⋅∇

- Laplace operator or Laplacian:

. The forms

and

represent the dot product of the gradient (

or

) with itself. Also notated Δ (next item).

- Δ

- 1. Another notation for the Laplacian (see above).

- 2. Operator of finite difference.

or

- Quad, the 4-vector gradient operator or four-gradient,

.

or

- Denotes the d’Alembertian or squared four-gradient, which is a generalization of the Laplacian to four-dimensional spacetime. In flat spacetime with Euclidean coordinates, this may mean either

or

; the sign convention must be specified. In curved spacetime (or flat spacetime with non-Euclidean coordinates), the definition is more complicated. Also called box or quabla.

(Capital Greek letter delta—not to be confused with

(Note: the notation

(here an actual box, not a placeholder)

Linear and multilinear algebra[edit]

- ∑ (Sigma notation)

- 1. Denotes the sum of a finite number of terms, which are determined by subscripts and superscripts (which can also be placed below and above), such as in

or

.

- 2. Denotes a series and, if the series is convergent, the sum of the series. For example,

.

- ∏ (Capital-pi notation)

- 1. Denotes the product of a finite number of terms, which are determined by subscripts and superscripts (which can also be placed below and above), such as in

or

.

- 2. Denotes an infinite product. For example, the Euler product formula for the Riemann zeta function is

.

- 3. Also used for the Cartesian product of any number of sets and the direct product of any number of mathematical structures.

- ⊕

- 1. Internal direct sum: if E and F are abelian subgroups of an abelian group V, notation

means that V is the direct sum of E and F; that is, every element of V can be written in a unique way as the sum of an element of E and an element of F. This applies also when E and F are linear subspaces or submodules of the vector space or module V.

- 2. Direct sum: if E and F are two abelian groups, vector spaces, or modules, then their direct sum, denoted

is an abelian group, vector space, or module (respectively) equipped with two monomorphisms

and

such that

is the internal direct sum of

and

. This definition makes sense because this direct sum is unique up to a unique isomorphism.

- 3. Exclusive or: if E and F are two Boolean variables or predicates,

may denote the exclusive or. Notations E XOR F and

are also commonly used; see ⊻.

- ⊗

- Denotes the tensor product. If E and F are abelian groups, vector spaces, or modules over a commutative ring, then the tensor product of E and F, denoted

is an abelian group, a vector space or a module (respectively), equipped with a bilinear map

from

to

, such that the bilinear maps from

to any abelian group, vector space or module G can be identified with the linear maps from

to G. If E and F are vector spaces over a field R, or modules over a ring R, the tensor product is often denoted

to avoid ambiguity.

- □⊤

- 1. Transpose: if A is a matrix,

denotes the transpose of A, that is, the matrix obtained by exchanging rows and columns of A. Notation

is also used. The symbol

is often replaced by the letter T or t.

- 2. For inline uses of the symbol, see ⊤.

- □⊥

- 1. Orthogonal complement: If W is a linear subspace of an inner product space V, then

denotes its orthogonal complement, that is, the linear space of the elements of V whose inner products with the elements of W are all zero.

- 2. Orthogonal subspace in the dual space: If W is a linear subspace (or a submodule) of a vector space (or of a module) V, then

may denote the orthogonal subspace of W, that is, the set of all linear forms that map W to zero.

- 3. For inline uses of the symbol, see ⊥.

Advanced group theory[edit]

- ⋉

⋊ - 1. Inner semidirect product: if N and H are subgroups of a group G, such that N is a normal subgroup of G, then

and

mean that G is the semidirect product of N and H, that is, that every element of G can be uniquely decomposed as the product of an element of N and an element of H. (Unlike for the direct product of groups, the element of H may change if the order of the factors is changed.)

- 2. Outer semidirect product: if N and H are two groups, and

is a group homomorphism from N to the automorphism group of H, then

denotes a group G, unique up to a group isomorphism, which is a semidirect product of N and H, with the commutation of elements of N and H defined by

.

- ≀

- In group theory,

denotes the wreath product of the groups G and H. It is also denoted as

or

; see Wreath product § Notation and conventions for several notation variants.

Infinite numbers[edit]

- ∞

- 1. The symbol is read as infinity. As an upper bound of a summation, an infinite product, an integral, etc., means that the computation is unlimited. Similarly,

in a lower bound means that the computation is not limited toward negative values.

- 2.

and

are the generalized numbers that are added to the real line to form the extended real line.

- 3.

is the generalized number that is added to the real line to form the projectively extended real line.

- 𝔠

denotes the cardinality of the continuum, which is the cardinality of the set of real numbers.

- ℵ

- With an ordinal i as a subscript, denotes the ith aleph number, that is the ith infinite cardinal. For example,

is the smallest infinite cardinal, that is, the cardinal of the natural numbers.

- ℶ

- With an ordinal i as a subscript, denotes the ith beth number. For example,

is the cardinal of the natural numbers, and

is the cardinal of the continuum.

- ω

- 1. Denotes the first limit ordinal. It is also denoted

and can be identified with the ordered set of the natural numbers.

- 2. With an ordinal i as a subscript, denotes the ith limit ordinal that has a cardinality greater than that of all preceding ordinals.

- 3. In computer science, denotes the (unknown) greatest lower bound for the exponent of the computational complexity of matrix multiplication.

- 4. Written as a function of another function, it is used for comparing the asymptotic growth of two functions. See Big O notation § Related asymptotic notations.

- 5. In number theory, may denote the prime omega function. That is,

is the number of distinct prime factors of the integer n.

Brackets[edit]

Many sorts of brackets are used in mathematics. Their meanings depend not only on their shapes, but also on the nature and the arrangement of what is delimited by them, and sometimes what appears between or before them. For this reason, in the entry titles, the symbol □ is used as a placeholder for schematizing the syntax that underlies the meaning.

Parentheses[edit]

- (□)

- Used in an expression for specifying that the sub-expression between the parentheses has to be considered as a single entity; typically used for specifying the order of operations.

- □(□)

□(□, □)

□(□, …, □) - 1. Functional notation: if the first

is the name (symbol) of a function, denotes the value of the function applied to the expression between the parentheses; for example,

,

. In the case of a multivariate function, the parentheses contain several expressions separated by commas, such as

.

- 2. May also denote a product, such as in

. When the confusion is possible, the context must distinguish which symbols denote functions, and which ones denote variables.

- (□, □)

- 1. Denotes an ordered pair of mathematical objects, for example,

.

- 2. If a and b are real numbers,

, or

, and a < b, then

denotes the open interval delimited by a and b. See ]□, □[ for an alternative notation.

- 3. If a and b are integers,

may denote the greatest common divisor of a and b. Notation

is often used instead.

- (□, □, □)

- If x, y, z are vectors in

, then

may denote the scalar triple product.[citation needed] See also [□,□,□] in § Square brackets.

- (□, …, □)

- Denotes a tuple. If there are n objects separated by commas, it is an n-tuple.

- (□, □, …)

(□, …, □, …) - Denotes an infinite sequence.

- Denotes a matrix. Often denoted with square brackets.

- Denotes a binomial coefficient: Given two nonnegative integers,

is read as «n choose k«, and is defined as the integer

(if k = 0, its value is conventionally 1). Using the left-hand-side expression, it denotes a polynomial in n, and is thus defined and used for any real or complex value of n.

- (□/□)

- Legendre symbol: If p is an odd prime number and a is an integer, the value of

is 1 if a is a quadratic residue modulo p; it is –1 if a is a quadratic non-residue modulo p; it is 0 if p divides a. The same notation is used for the Jacobi symbol and Kronecker symbol, which are generalizations where p is respectively any odd positive integer, or any integer.

Square brackets[edit]

- [□]

- 1. Sometimes used as a synonym of (□) for avoiding nested parentheses.

- 2. Equivalence class: given an equivalence relation,

often denotes the equivalence class of the element x.

- 3. Integral part: if x is a real number,

often denotes the integral part or truncation of x, that is, the integer obtained by removing all digits after the decimal mark. This notation has also been used for other variants of floor and ceiling functions.

- 4. Iverson bracket: if P is a predicate,

may denote the Iverson bracket, that is the function that takes the value 1 for the values of the free variables in P for which P is true, and takes the value 0 otherwise. For example,

is the Kronecker delta function, which equals one if

, and zero otherwise.

- □[□]

- Image of a subset: if S is a subset of the domain of the function f, then

is sometimes used for denoting the image of S. When no confusion is possible, notation f(S) is commonly used.

- [□, □]

- 1. Closed interval: if a and b are real numbers such that

, then

denotes the closed interval defined by them.

- 2. Commutator (group theory): if a and b belong to a group, then

.

- 3. Commutator (ring theory): if a and b belong to a ring, then

.

- 4. Denotes the Lie bracket, the operation of a Lie algebra.

- [□ : □]

- 1. Degree of a field extension: if F is an extension of a field E, then

denotes the degree of the field extension

. For example,

.

- 2. Index of a subgroup: if H is a subgroup of a group E, then

denotes the index of H in G. The notation |G:H| is also used

- [□, □, □]

- If x, y, z are vectors in

, then

may denote the scalar triple product.[5] See also (□,□,□) in § Parentheses.

- Denotes a matrix. Often denoted with parentheses.

Braces[edit]

- { }

- Set-builder notation for the empty set, also denoted

or ∅.

- {□}

- 1. Sometimes used as a synonym of (□) and [□] for avoiding nested parentheses.

- 2. Set-builder notation for a singleton set:

denotes the set that has x as a single element.

- {□, …, □}

- Set-builder notation: denotes the set whose elements are listed between the braces, separated by commas.

- {□ : □}

{□ | □} - Set-builder notation: if

is a predicate depending on a variable x, then both

and

denote the set formed by the values of x for which

is true.

- Single brace

- 1. Used for emphasizing that several equations have to be considered as simultaneous equations; for example,

.

- 2. Piecewise definition; for example,

.

- 3. Used for grouped annotation of elements in a formula; for example,

,

,

Other brackets[edit]

- |□|

- 1. Absolute value: if x is a real or complex number,

denotes its absolute value.

- 2. Number of elements: If S is a set,

may denote its cardinality, that is, its number of elements.

is also often used, see #.

- 3. Length of a line segment: If P and Q are two points in a Euclidean space, then

often denotes the length of the line segment that they define, which is the distance from P to Q, and is often denoted

.

- 4. For a similar-looking operator, see |.

- |□:□|

- Index of a subgroup: if H is a subgroup of a group G, then

denotes the index of H in G. The notation [G:H] is also used

denotes the determinant of the square matrix

.

- ||□||

- 1. Denotes the norm of an element of a normed vector space.

- 2. For the similar-looking operator named parallel, see ∥.

- ⌊□⌋

- Floor function: if x is a real number,

is the greatest integer that is not greater than x.

- ⌈□⌉

- Ceiling function: if x is a real number,

is the lowest integer that is not lesser than x.

- ⌊□⌉

- Nearest integer function: if x is a real number,

is the integer that is the closest to x.

- ]□, □[

- Open interval: If a and b are real numbers,

, or

, and

, then

denotes the open interval delimited by a and b. See (□, □) for an alternative notation.

- (□, □]

]□, □] - Both notations are used for a left-open interval.

- [□, □)

[□, □[ - Both notations are used for a right-open interval.

- ⟨□⟩

- 1. Generated object: if S is a set of elements in an algebraic structure,

denotes often the object generated by S. If

, one writes

(that is, braces are omitted). In particular, this may denote

- the linear span in a vector space (also often denoted Span(S)),

- the generated subgroup in a group,

- the generated ideal in a ring,

- the generated submodule in a module.

- 2. Often used, mainly in physics, for denoting an expected value. In probability theory,

is generally used instead of

.

- ⟨□, □⟩

⟨□ | □⟩ - Both

and

are commonly used for denoting the inner product in an inner product space.

- ⟨□| and |□⟩

- Bra–ket notation or Dirac notation: if x and y are elements of an inner product space,

is the vector defined by x, and

is the covector defined by y; their inner product is

.

Symbols that do not belong to formulas[edit]

In this section, the symbols that are listed are used as some sorts of punctuation marks in mathematical reasoning, or as abbreviations of English phrases. They are generally not used inside a formula. Some were used in classical logic for indicating the logical dependence between sentences written in plain English. Except for the first two, they are normally not used in printed mathematical texts since, for readability, it is generally recommended to have at least one word between two formulas. However, they are still used on a black board for indicating relationships between formulas.

- ■ , □

- Used for marking the end of a proof and separating it from the current text. The initialism Q.E.D. or QED (Latin: quod erat demonstrandum, «as was to be shown») is often used for the same purpose, either in its upper-case form or in lower case.

- ☡

- Bourbaki dangerous bend symbol: Sometimes used in the margin to forewarn readers against serious errors, where they risk falling, or to mark a passage that is tricky on a first reading because of an especially subtle argument.

- ∴

- Abbreviation of «therefore». Placed between two assertions, it means that the first one implies the second one. For example: «All humans are mortal, and Socrates is a human. ∴ Socrates is mortal.»

- ∵

- Abbreviation of «because» or «since». Placed between two assertions, it means that the first one is implied by the second one. For example: «11 is prime ∵ it has no positive integer factors other than itself and one.»

- ∋

- 1. Abbreviation of «such that». For example,

is normally printed «x such that

«.

- 2. Sometimes used for reversing the operands of

; that is,

has the same meaning as

. See ∈ in § Set theory.

- ∝

- Abbreviation of «is proportional to».

Miscellaneous[edit]

- !

- 1. Factorial: if n is a positive integer, n! is the product of the first n positive integers, and is read as «n factorial».

- 2. Subfactorial: if n is a positive integer, !n is the number of derangements of a set of n elements, and is read as «the subfactorial of n».

- *

- Many different uses in mathematics; see Asterisk § Mathematics.

- |

- 1. Divisibility: if m and n are two integers,

means that m divides n evenly.

- 2. In set-builder notation, it is used as a separator meaning «such that»; see {□ | □}.

- 3. Restriction of a function: if f is a function, and S is a subset of its domain, then

is the function with S as a domain that equals f on S.

- 4. Conditional probability:

denotes the probability of X given that the event E occurs. Also denoted

; see «/».

- 5. For several uses as brackets (in pairs or with ⟨ and ⟩) see § Other brackets.

- ∤

- Non-divisibility:

means that n is not a divisor of m.

- ∥

- 1. Denotes parallelism in elementary geometry: if PQ and RS are two lines,

means that they are parallel.

- 2. Parallel, an arithmetical operation used in electrical engineering for modeling parallel resistors:

.

- 3. Used in pairs as brackets, denotes a norm; see ||□||.

- ∦

- Sometimes used for denoting that two lines are not parallel; for example,

.

- 1. Denotes perpendicularity and orthogonality. For example, if A, B, C are three points in a Euclidean space, then

means that the line segments AB and AC are perpendicular, and form a right angle.

- 2. For the similar symbol, see

.

- ⊙

- Hadamard product of power series: if

and

, then

. Possibly,

is also used instead of ○ for the Hadamard product of matrices.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- List of mathematical symbols (Unicode and LaTeX)

- List of mathematical symbols by subject

- List of logic symbols

- Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols (Unicode block)

- Mathematical constants and functions

- Table of mathematical symbols by introduction date

- List of Unicode characters

- Blackboard bold#Usage

- Letterlike Symbols

- Unicode block

- Lists of Mathematical operators and symbols in Unicode

- Mathematical Operators and Supplemental Mathematical Operators

- Miscellaneous Math Symbols: A, B, Technical

- Arrow (symbol) and Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows and arrow symbols

- ISO 31-11 (Mathematical signs and symbols for use in physical sciences and technology)

- Number Forms

- Geometric Shapes

- Diacritic

- Language of mathematics

- Mathematical notation

- Typographical conventions and common meanings of symbols:

- APL syntax and symbols

- Greek letters used in mathematics, science, and engineering

- Latin letters used in mathematics

- List of common physics notations

- List of letters used in mathematics and science

- List of mathematical abbreviations

- Mathematical notation

- Notation in probability and statistics

- Physical constants

- Typographical conventions in mathematical formulae

References[edit]

- ^ ISO 80000-2, Section 9 «Operations», 2-9.6

- ^ «Statistics and Data Analysis: From Elementary to Intermediate».

- ^ a b c d Letourneau, Mary; Wright Sharp, Jennifer (2017). «AMS style guide» (PDF). American Mathematical Society. p. 99.

- ^ The LaTeX equivalent to both Unicode symbols ∘ and ○ is circ. The Unicode symbol that has the same size as circ depends on the browser and its implementation. In some cases ∘ is so small that it can be confused with an interpoint, and ○ looks similar as circ. In other cases, ○ is too large for denoting a binary operation, and it is ∘ that looks like circ. As LaTeX is commonly considered as the standard for mathematical typography, and it does not distinguish these two Unicode symbols, they are considered here as having the same mathematical meaning.

- ^ Rutherford, D. E. (1965). Vector Methods. University Mathematical Texts. Oliver and Boyd Ltd., Edinburgh.

External links[edit]

- Jeff Miller: Earliest Uses of Various Mathematical Symbols

- Numericana: Scientific Symbols and Icons

- GIF and PNG Images for Math Symbols

- Mathematical Symbols in Unicode

- Detexify: LaTeX Handwriting Recognition Tool

- Some Unicode charts of mathematical operators and symbols:

- Index of Unicode symbols

- Range 2100–214F: Unicode Letterlike Symbols

- Range 2190–21FF: Unicode Arrows

- Range 2200–22FF: Unicode Mathematical Operators

- Range 27C0–27EF: Unicode Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols–A

- Range 2980–29FF: Unicode Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols–B

- Range 2A00–2AFF: Unicode Supplementary Mathematical Operators

- Some Unicode cross-references:

- Short list of commonly used LaTeX symbols and Comprehensive LaTeX Symbol List

- MathML Characters — sorts out Unicode, HTML and MathML/TeX names on one page

- Unicode values and MathML names

- Unicode values and Postscript names from the source code for Ghostscript

A mathematical symbol is a figure or a combination of figures that is used to represent a mathematical object, an action on mathematical objects, a relation between mathematical objects, or for structuring the other symbols that occur in a formula. As formulas are entirely constituted with symbols of various types, many symbols are needed for expressing all mathematics.

The most basic symbols are the decimal digits (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), and the letters of the Latin alphabet. The decimal digits are used for representing numbers through the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. Historically, upper-case letters were used for representing points in geometry, and lower-case letters were used for variables and constants. Letters are used for representing many other sorts of mathematical objects. As the number of these sorts has remarkably increased in modern mathematics, the Greek alphabet and some Hebrew letters are also used. In mathematical formulas, the standard typeface is italic type for Latin letters and lower-case Greek letters, and upright type for upper case Greek letters. For having more symbols, other typefaces are also used, mainly boldface

The use of Latin and Greek letters as symbols for denoting mathematical objects is not described in this article. For such uses, see Variable (mathematics) and List of mathematical constants. However, some symbols that are described here have the same shape as the letter from which they are derived, such as

These letters alone are not sufficient for the needs of mathematicians, and many other symbols are used. Some take their origin in punctuation marks and diacritics traditionally used in typography; others by deforming letter forms, as in the cases of

Layout of this article[edit]

Normally, entries of a glossary are structured by topics and sorted alphabetically. This is not possible here, as there is no natural order on symbols, and many symbols are used in different parts of mathematics with different meanings, often completely unrelated. Therefore, some arbitrary choices had to be made, which are summarized below.

The article is split into sections that are sorted by an increasing level of technicality. That is, the first sections contain the symbols that are encountered in most mathematical texts, and that are supposed to be known even by beginners. On the other hand, the last sections contain symbols that are specific to some area of mathematics and are ignored outside these areas. However, the long section on brackets has been placed near to the end, although most of its entries are elementary: this makes it easier to search for a symbol entry by scrolling.

Most symbols have multiple meanings that are generally distinguished either by the area of mathematics where they are used or by their syntax, that is, by their position inside a formula and the nature of the other parts of the formula that are close to them.

As readers may not be aware of the area of mathematics to which is related the symbol that they are looking for, the different meanings of a symbol are grouped in the section corresponding to their most common meaning.

When the meaning depends on the syntax, a symbol may have different entries depending on the syntax. For summarizing the syntax in the entry name, the symbol

Most symbols have two printed versions. They can be displayed as Unicode characters, or in LaTeX format. With the Unicode version, using search engines and copy-pasting are easier. On the other hand, the LaTeX rendering is often much better (more aesthetic), and is generally considered a standard in mathematics. Therefore, in this article, the Unicode version of the symbols is used (when possible) for labelling their entry, and the LaTeX version is used in their description. So, for finding how to type a symbol in LaTeX, it suffices to look at the source of the article.

For most symbols, the entry name is the corresponding Unicode symbol. So, for searching the entry of a symbol, it suffices to type or copy the Unicode symbol into the search textbox. Similarly, when possible, the entry name of a symbol is also an anchor, which allows linking easily from another Wikipedia article. When an entry name contains special characters such as [, ], and |, there is also an anchor, but one has to look at the article source to know it.

Finally, when there is an article on the symbol itself (not its mathematical meaning), it is linked to in the entry name.

Arithmetic operators[edit]

- +

- 1. Denotes addition and is read as plus; for example, 3 + 2.

- 2. Denotes that a number is positive and is read as plus. Redundant, but sometimes used for emphasizing that a number is positive, specially when other numbers in the context are or may be negative; for example, +2.

- 3. Sometimes used instead of

for a disjoint union of sets.

- –

- 1. Denotes subtraction and is read as minus; for example, 3 – 2.

- 2. Denotes the additive inverse and is read as negative or the opposite of; for example, –2.

- 3. Also used in place of for denoting the set-theoretic complement; see in § Set theory.

- ×

- 1. In elementary arithmetic, denotes multiplication, and is read as times; for example, 3 × 2.

- 2. In geometry and linear algebra, denotes the cross product.

- 3. In set theory and category theory, denotes the Cartesian product and the direct product. See also × in § Set theory.

- ·

- 1. Denotes multiplication and is read as times; for example, 3 ⋅ 2.

- 2. In geometry and linear algebra, denotes the dot product.

- 3. Placeholder used for replacing an indeterminate element. For example, «the absolute value is denoted | · |» is clearer than saying that it is denoted as | |.

- ±

- 1. Denotes either a plus sign or a minus sign.

- 2. Denotes the range of values that a measured quantity may have; for example, 10 ± 2 denotes an unknown value that lies between 8 and 12.

- ∓

- Used paired with ±, denotes the opposite sign; that is, + if ± is –, and – if ± is +.

- ÷

- Widely used for denoting division in anglophone countries, it is no longer in common use in mathematics and its use is «not recommended».[1] In some countries, it can indicate subtraction.

- :

- 1. Denotes the ratio of two quantities.

- 2. In some countries, may denote division.

- 3. In set-builder notation, it is used as a separator meaning «such that»; see {□ : □}.

- /

- 1. Denotes division and is read as divided by or over. Often replaced by a horizontal bar. For example, 3 / 2 or

.

- 2. Denotes a quotient structure. For example, quotient set, quotient group, quotient category, etc.

- 3. In number theory and field theory,

denotes a field extension, where F is an extension field of the field E.

- 4. In probability theory, denotes a conditional probability. For example,

denotes the probability of A, given that B occurs. Also denoted

: see «|«.

- √

- Denotes square root and is read as the square root of. Rarely used in modern mathematics without a horizontal bar delimiting the width of its argument (see the next item). For example, √2.

- √

- 1. Denotes square root and is read as the square root of. For example,

.

- 2. With an integer greater than 2 as a left superscript, denotes an nth root. For example,

.

- ^

- 1. Exponentiation is normally denoted with a superscript. However,

is often denoted x^y when superscripts are not easily available, such as in programming languages (including LaTeX) or plain text emails.

- 2. Not to be confused with ∧.

Equality, equivalence and similarity[edit]

- =

- 1. Denotes equality.

- 2. Used for naming a mathematical object in a sentence like «let

«, where E is an expression. On a blackboard and in some mathematical texts, this may be abbreviated as

or

This is related to the concept of assignment in computer science, which is variously denoted (depending on the programming language used)

- ≠

- Denotes inequality and means «not equal».

- ≈

- Means «is approximately equal to». For example,

(for a more accurate approximation, see pi).

- ~

- 1. Between two numbers, either it is used instead of ≈ to mean «approximatively equal», or it means «has the same order of magnitude as».

- 2. Denotes the asymptotic equivalence of two functions or sequences.

- 3. Often used for denoting other types of similarity, for example, matrix similarity or similarity of geometric shapes.

- 4. Standard notation for an equivalence relation.

- 5. In probability and statistics, may specify the probability distribution of a random variable. For example,

means that the distribution of the random variable X is standard normal.[2]

- 6. Notation for showing proportionality. See also ∝ for a less ambiguous symbol.

- ≡

- 1. Denotes an identity, that is, an equality that is true whichever values are given to the variables occurring in it.

- 2. In number theory, and more specifically in modular arithmetic, denotes the congruence modulo an integer.

- 1. May denote an isomorphism between two mathematical structures, and is read as «is isomorphic to».

- 2. In geometry, may denote the congruence of two geometric shapes (that is the equality up to a displacement), and is read «is congruent to».

Comparison[edit]

- <

- 1. Strict inequality between two numbers; means and is read as «less than».

- 2. Commonly used for denoting any strict order.

- 3. Between two groups, may mean that the first one is a proper subgroup of the second one.

- >

- 1. Strict inequality between two numbers; means and is read as «greater than».

- 2. Commonly used for denoting any strict order.

- 3. Between two groups, may mean that the second one is a proper subgroup of the first one.

- ≤

- 1. Means «less than or equal to». That is, whatever A and B are, A ≤ B is equivalent to A < B or A = B.

- 2. Between two groups, may mean that the first one is a subgroup of the second one.

- ≥

- 1. Means «greater than or equal to». That is, whatever A and B are, A ≥ B is equivalent to A > B or A = B.

- 2. Between two groups, may mean that the second one is a subgroup of the first one.

- ≪ , ≫

- 1. Means «much less than» and «much greater than». Generally, much is not formally defined, but means that the lesser quantity can be neglected with respect to the other. This is generally the case when the lesser quantity is smaller than the other by one or several orders of magnitude.

- 2. In measure theory,

means that the measure

is absolutely continuous with respect to the measure

.

- ≦

- 1. A rarely used synonym of ≤. Despite the easy confusion with ≤, some authors use it with a different meaning.

- ≺ , ≻

- Often used for denoting an order or, more generally, a preorder, when it would be confusing or not convenient to use < and >.

Set theory[edit]

- ∅

- Denotes the empty set, and is more often written

. Using set-builder notation, it may also be denoted

.

- #

- 1. Number of elements:

may denote the cardinality of the set S. An alternative notation is

; see

.

- 2. Primorial:

denotes the product of the prime numbers that are not greater than n.

- 3. In topology,

denotes the connected sum of two manifolds or two knots.

- ∈

- Denotes set membership, and is read «in» or «belongs to». That is,

means that x is an element of the set S.

- ∉

- Means «not in». That is,

means

.

- ⊂

- Denotes set inclusion. However two slightly different definitions are common.

- 1.

may mean that A is a subset of B, and is possibly equal to B; that is, every element of A belongs to B; in formula,

.

- 2.

may mean that A is a proper subset of B, that is the two sets are different, and every element of A belongs to B; in formula,

.

- ⊆

means that A is a subset of B. Used for emphasizing that equality is possible, or when the second definition of

is used.

- ⊊

means that A is a proper subset of B. Used for emphasizing that

, or when the first definition of

is used.

- ⊃, ⊇, ⊋

- Denote the converse relation of

,

, and

respectively. For example,

is equivalent to

.

- ∪

- Denotes set-theoretic union, that is,

is the set formed by the elements of A and B together. That is,

.

- ∩

- Denotes set-theoretic intersection, that is,

is the set formed by the elements of both A and B. That is,

.

- ∖

- Set difference; that is,

is the set formed by the elements of A that are not in B. Sometimes,

is used instead; see – in § Arithmetic operators.

- ⊖ or

- Symmetric difference: that is,

or

is the set formed by the elements that belong to exactly one of the two sets A and B.

- ∁

- 1. With a subscript, denotes a set complement: that is, if

, then

.

- 2. Without a subscript, denotes the absolute complement; that is,

, where U is a set implicitly defined by the context, which contains all sets under consideration. This set U is sometimes called the universe of discourse.

- ×

- See also × in § Arithmetic operators.

- 1. Denotes the Cartesian product of two sets. That is,

is the set formed by all pairs of an element of A and an element of B.

- 2. Denotes the direct product of two mathematical structures of the same type, which is the Cartesian product of the underlying sets, equipped with a structure of the same type. For example, direct product of rings, direct product of topological spaces.

- 3. In category theory, denotes the direct product (often called simply product) of two objects, which is a generalization of the preceding concepts of product.

- ⊔

- Denotes the disjoint union. That is, if A and B are sets then

is a set of pairs where iA and iB are distinct indices discriminating the members of A and B in

.

- ∐

- 1. An alternative to

.

- 2. Denotes the coproduct of mathematical structures or of objects in a category.

Basic logic[edit]

Several logical symbols are widely used in all mathematics, and are listed here. For symbols that are used only in mathematical logic, or are rarely used, see List of logic symbols.

- ¬

- Denotes logical negation, and is read as «not». If E is a logical predicate,

is the predicate that evaluates to true if and only if E evaluates to false. For clarity, it is often replaced by the word «not». In programming languages and some mathematical texts, it is sometimes replaced by «~» or «!«, which are easier to type on some keyboards.

- ∨

- 1. Denotes the logical or, and is read as «or». If E and F are logical predicates,

is true if either E, F, or both are true. It is often replaced by the word «or».

- 2. In lattice theory, denotes the join or least upper bound operation.

- 3. In topology, denotes the wedge sum of two pointed spaces.

- ∧

- 1. Denotes the logical and, and is read as «and». If E and F are logical predicates,

is true if E and F are both true. It is often replaced by the word «and» or the symbol «&«.

- 2. In lattice theory, denotes the meet or greatest lower bound operation.

- 3. In multilinear algebra, geometry, and multivariable calculus, denotes the wedge product or the exterior product.

- ⊻

- Exclusive or: if E and F are two Boolean variables or predicates,

denotes the exclusive or. Notations E XOR F and

are also commonly used; see ⊕.

- ∀

- 1. Denotes universal quantification and is read as «for all». If E is a logical predicate,

means that E is true for all possible values of the variable x.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «for all» or «for every».

- ∃

- 1. Denotes existential quantification and is read «there exists … such that». If E is a logical predicate,

means that there exists at least one value of x for which E is true.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «there exists».

- ∃!

- Denotes uniqueness quantification, that is,

means «there exists exactly one x such that P (is true)». In other words,

is an abbreviation of

.

- ⇒

- 1. Denotes material conditional, and is read as «implies». If P and Q are logical predicates,

means that if P is true, then Q is also true. Thus,

is logically equivalent with

.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «implies».

- ⇔

- 1. Denotes logical equivalence, and is read «is equivalent to» or «if and only if». If P and Q are logical predicates,

is thus an abbreviation of

, or of

.

- 2. Often used improperly[3] in plain text as an abbreviation of «if and only if».

- ⊤

- 1.

denotes the logical predicate always true.

- 2. Denotes also the truth value true.

- 3. Sometimes denotes the top element of a bounded lattice (previous meanings are specific examples).

- 4. For the use as a superscript, see □⊤.

- ⊥

- 1.

denotes the logical predicate always false.

- 2. Denotes also the truth value false.

- 3. Sometimes denotes the bottom element of a bounded lattice (previous meanings are specific examples).

- 4. In Cryptography often denotes an error in place of a regular value.

- 5. For the use as a superscript, see □⊥.

- 6. For the similar symbol, see

.

Blackboard bold[edit]