Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

Знак пересечения

Определение

Знак пересечения – это символ, указывающий на пересечение прямых, углов, лучей, отрезков, плоскостей и других фигур в геометрии, пересечение множеств в математике (алгебре) и информатике.

Как пишется этот символ пересечения?

Этот знак выглядит и пишется так – ⋂

Его достаточно легко запомнить, он похож на русскую букву «П», начальную букву слова «пересечение».

Как быстро запомнить этот знак?

Просто представьте себе и запомните, что этот символ выглядит как буква «П» и похож на подкову, перевернутую вниз ногами.

Как применяется знак ⋂?

Применяется для обозначения пересечения прямых, углов, лучей, отрезков в геометрии, пересечение множеств в математике (алгебре) и информатике.

Как выглядит знак «не пересечения» в геометрии?

Пример

А ∩ С = ∅ — 2 луча или (2 прямые, 2отрезка) А и С не пересекаются.

Что обозначает знак пересечения наоборот?

Это символ выглядит и пишется следующим образом: ∪

Обозначается термином – «объединение».

Источник

Геометрия 7 класс.

Точка, прямая и отрезок

Казалось бы, что таким простым понятиям, как «точка» или «прямая», которые мы повседневно используем в жизни, крайне просто дать определения. Но на практике оказалось, что это не так.

Существует множество определений, которые давали знаменитые математики терминам «точка» и «прямая». За многие века ученые так и не пришли к единому определению.

Мы не будем приводить все определения точки и прямой. Остановимся на объяснениях, которые, на наш взгляд, наиболее простым образом их описывают.

Точка — элементарная фигура, не имеющая частей.

Прямая состоит из множества точек и простирается бесконечно в обе стороны.

То есть выражаясь геометрическими обозначениями, информацию о расположении прямой и точек на рисунке выше можно записать так:

Как обозначить прямую

Прямую обычно обозначают одной маленькой латинской буквой.

Прямую, на которой отмечены две точки, иногда обозначают по названиям этих точек большими латинскими точками.

Задача № 1 из учебника Атанасян 7-9 класс

Решение задачи

Опишем взаимное расположение точек и прямой.

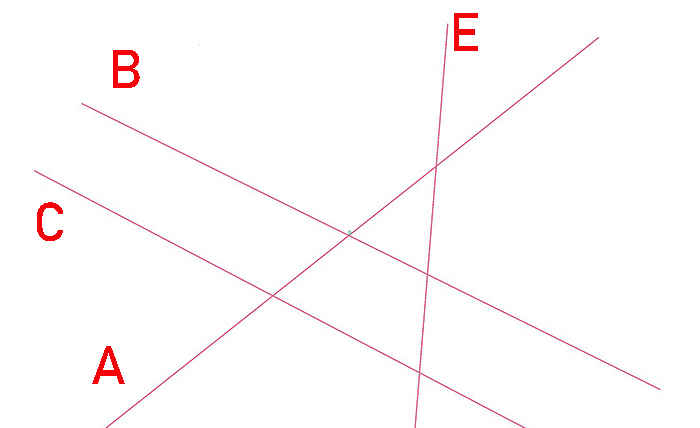

Как обозначается пересечение прямых

Хотя на чертеже не видно, но прямые a и c тоже пересекаются (это становится ясно, если мысленно продолжить вниз прямые a и с ).

Прямые e и f не имеют общей точки — т.е. они не пересекаются.

Взаимное расположение прямой и точек

Через одну точку (·)A можно провести сколько угодно прямых.

Через две точки (·)A и (·)B можно провести только одну прямую.

Сколько общих точек имеют две прямые

Две прямые либо имеют только одну общую точку, либо не имеют общих точек.

Докажем утверждение выше. Для этого рассмотрим все возможные случаи расположения двух прямых.

Первый случай расположения прямых

На рисунке выше мы видим, что у прямых f и e нет общих точек, т.к. эти прямые не пересекаются.

Второй случай расположения прямых

Третий случай расположения прямых

Вывод: две прямые либо имеют только одну общую точку, либо не имеют общих точек.

Задача № 3 из учебника Атанасян 7-9 класс

Проведите три прямые так, чтобы каждые две из них пересекались. Обозначьте все точки пересечения этих прямых. Сколько получилось точек? Рассмотрите все возможные случаи.

Решение задачи

Проведём две прямые a и b так, чтобы эти две прямые пересекались, и обозначим точку пересечения.

Как мы видим, точка пересечения только одна. Мы можем провести третью прямую так, чтобы она тоже проходила через эту точку пересечения.

Мы убедились, что возможны оба варианта. Поэтому в ответе запишем их оба.

Ответ: точек пересечения получается одна или три.

Что такое отрезок

Отрезок — часть прямой, ограниченная двумя точками.

В отличии от прямой любой отрезок можно измерить. Т.е. каждый отрезок имеет длину.

Источник

Обозначения и символика

Для обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между ними, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем в курсе используется геометрический язык, составленный из обозначений и символов, принятых в курсе математики (в частности, в новом курсе геометрии в средней школе).

Все многообразие обозначений и символов, а также связи между ними могут быть подразделены на две группы:

группа I — обозначения геометрических фигур и отношений между ними;

группа II обозначения логических операций, составляющие синтаксическую основу геометрического языка.

Ниже приводится полный список математических символов, используемых в данном курсе. Особое внимание уделяется символам, которые применяются для обозначения проекций геометрических фигур.

СИМВОЛЫ, ОБОЗНАЧАЮЩИЕ ГЕОМЕТРИЧЕСКИЕ ФИГУРЫ И ОТНОШЕНИЯ МЕЖДУ НИМИ

А. Обозначение геометрических фигур

1. Геометрическая фигура обозначается — Ф.

2. Точки обозначаются прописными буквами латинского алфавита или арабскими цифрами:

3. Линии, произвольно расположенные по отношению к плоскостям проекций, обозначаются строчными буквами латинского алфавита:

Линии уровня обозначаются: h — горизонталь; f— фронталь.

Для прямых используются также следующие обозначения:

(АВ) — прямая, проходящая через точки А а В;

[АВ) — луч с началом в точке А;

[АВ] — отрезок прямой, ограниченный точками А и В.

4. Поверхности обозначаются строчными буквами греческого алфавита:

Чтобы подчеркнуть способ задания поверхности, следует указывать геометрические элементы, которыми она определяется, например:

α(а || b) — плоскость α определяется параллельными прямыми а и b;

5. Углы обозначаются:

6. Угловая: величина (градусная мера) обозначается знаком

Прямой угол отмечается квадратом с точкой внутри

7. Расстояния между геометрическими фигурами обозначаются двумя вертикальными отрезками — ||.

|АВ| — расстояние между точками А и В (длина отрезка АВ);

|Аа| — расстояние от точки А до линии a;

|Аα| — расстояшие от точки А до поверхности α;

|аb| — расстояние между линиями а и b;

|αβ| расстояние между поверхностями α и β.

π2 —фрюнтальная плоскость проекций.

При замене плоскостей проекций или введении новых плоскостей последние обозначают π3, π4 и т. д.

Постояшную прямую эпюра Монжа обозначают k.

10. Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей, любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса, соответствующего плоскости проекции, на которой они получены:

11. Следы плоскостей (поверхностей) обозначаются теми же буквами, что и горизонталь или фронталь, с добавлением подстрочного индекса 0α, подчеркивающего, что эти линии лежат в плоскости проекции и принадлежат плоскости (поверхности) α.

12. Следы прямых (линий) обозначаются заглавными буквами, с которых начинаются слова, определяющие название (в латинской транскрипции) плоскости проекции, которую пересекает линия, с подстрочным индексом, указывающим принадлежность к линии.

Например: Ha — горизонтальный след прямой (линии) а;

Fa — фронтальный след прямой (линии ) a.

13. Последовательность точек, линий (любой фигуры) отмечается подстрочными индексами 1,2,3. n:

Вспомогательная проекция точки, полученная в результате преобразования для получения действительной величины геометрической фигуры, обозначается той же буквой с подстрочным индексом 0:

14. Аксонометрические проекции точек, линий, поверхностей обозначаются теми же буквами, что и натура с добавлением верхнего индекса 0 :

15. Вторичные проекции обозначаются путем добавления верхнего индекса 1 :

Для облегчения чтения чертежей в учебнике при оформлении иллюстративного материала использованы несколько цветов, каждый из которых имеет определенное смысловое значение: линиями (точками) черного цвета обозначены исходные данные; зеленый цвет использован для линий вспомогательных графических построений; красными линиями (точками) показаны результаты построений или те геометрические элементы, на которые следует обратить особое внимание.

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как пишется знак пересечения в геометрии, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как пишется знак пересечения в геометрии», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

∩ Пересечение

Нажмите, чтобы скопировать и вставить символ

Значение символа

Пересечение. Математические операторы.

Символ «Пересечение» был утвержден как часть Юникода версии 1.1 в 1993 г.

Свойства

| Версия | 1.1 |

| Блок | Математические операторы |

| Тип парной зеркальной скобки (bidi) | Нет |

| Композиционное исключение | Нет |

| Изменение регистра | 2229 |

| Простое изменение регистра | 2229 |

Кодировка

| Кодировка | hex | dec (bytes) | dec | binary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTF-8 | E2 88 A9 | 226 136 169 | 14846121 | 11100010 10001000 10101001 |

| UTF-16BE | 22 29 | 34 41 | 8745 | 00100010 00101001 |

| UTF-16LE | 29 22 | 41 34 | 10530 | 00101001 00100010 |

| UTF-32BE | 00 00 22 29 | 0 0 34 41 | 8745 | 00000000 00000000 00100010 00101001 |

| UTF-32LE | 29 22 00 00 | 41 34 0 0 | 690094080 | 00101001 00100010 00000000 00000000 |

Для обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между ними, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем в курсе используется геометрический язык, составленный из обозначений и символов, принятых в курсе математики (в частности, в новом курсе геометрии в средней школе).

Все многообразие обозначений и символов, а также связи между ними могут быть подразделены на две группы:

группа I — обозначения геометрических фигур и отношений между ними;

группа II обозначения логических операций, составляющие синтаксическую основу геометрического языка.

Ниже приводится полный список математических символов, используемых в данном курсе. Особое внимание уделяется символам, которые применяются для обозначения проекций геометрических фигур.

Группа I

СИМВОЛЫ, ОБОЗНАЧАЮЩИЕ ГЕОМЕТРИЧЕСКИЕ ФИГУРЫ И ОТНОШЕНИЯ МЕЖДУ НИМИ

А. Обозначение геометрических фигур

1. Геометрическая фигура обозначается — Ф.

2. Точки обозначаются прописными буквами латинского алфавита или арабскими цифрами:

А, В, С, D, … , L, М, N, …

1,2,3,4,…,12,13,14,…

3. Линии, произвольно расположенные по отношению к плоскостям проекций, обозначаются строчными буквами латинского алфавита:

а, b, с, d, … , l, m, n, …

Линии уровня обозначаются: h — горизонталь; f— фронталь.

Для прямых используются также следующие обозначения:

(АВ) — прямая, проходящая через точки А а В;

[АВ) — луч с началом в точке А;

[АВ] — отрезок прямой, ограниченный точками А и В.

4. Поверхности обозначаются строчными буквами греческого алфавита:

α, β, γ, δ,…,ζ,η,ν,…

Чтобы подчеркнуть способ задания поверхности, следует указывать геометрические элементы, которыми она определяется, например:

α(а || b) — плоскость α определяется параллельными прямыми а и b;

β(d1 d2gα) — поверхность β определяется направляющими d1 и d2 , образующей g и плоскостью параллелизма α.

5. Углы обозначаются:

∠ABC — угол с вершиной в точке В, а также ∠α°, ∠β°, … , ∠φ°, …

6. Угловая: величина (градусная мера) обозначается знаком

Прямой угол отмечается квадратом с точкой внутри

7. Расстояния между геометрическими фигурами обозначаются двумя вертикальными отрезками — ||.

Например:

|АВ| — расстояние между точками А и В (длина отрезка АВ);

|Аа| — расстояние от точки А до линии a;

|Аα| — расстояшие от точки А до поверхности α;

|аb| — расстояние между линиями а и b;

|αβ| расстояние между поверхностями α и β.

8. Для плоскостей проекций приняты обозначения: π1 и π2,

где π1 — горизонтальная плоскость проекций;

π2 —фрюнтальная плоскость проекций.

При замене плоскостей проекций или введении новых плоскостей последние обозначают π3, π4 и т. д.

9. Оси проекций обозначаются: х, у, z, где х — ось абсцисс; у — ось ординат; z — ось аппликат.

Постояшную прямую эпюра Монжа обозначают k.

10. Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей, любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса, соответствующего плоскости проекции, на которой они получены:

А’, В’, С’, D’, … , L’, М’, N’, горизонтальные проекции точек; А», В», С», D», … , L», М», N», … фронтальные проекции точек; a’ , b’ , c’ , d’ , … , l’, m’ , n’ , —

горизонтальные проекции линий; а» ,b» , с» , d» , … , l» , m» , n» , … фронтальные проекции линий; α’, β’, γ’, δ’,…,ζ’,η’,ν’,… горизонтальные проекции поверхностей;

α», β», γ», δ»,…,ζ»,η»,ν»,…

фронтальные проекции поверхностей.

11. Следы плоскостей (поверхностей) обозначаются теми же буквами, что и горизонталь или фронталь, с добавлением подстрочного индекса 0α, подчеркивающего, что эти линии лежат в плоскости проекции и принадлежат плоскости (поверхности) α.

Так: h0α — горизонтальный след плоскости (поверхности) α;

f0α — фронтальный след плоскости (поверхности) α.

12. Следы прямых (линий) обозначаются заглавными буквами, с которых начинаются слова, определяющие название (в латинской транскрипции) плоскости проекции, которую пересекает линия, с подстрочным индексом, указывающим принадлежность к линии.

Например: Ha — горизонтальный след прямой (линии) а;

Fa — фронтальный след прямой (линии ) a.

13. Последовательность точек, линий (любой фигуры) отмечается подстрочными индексами 1,2,3,…, n:

А1, А2, А3,…,Аn;

a1, a2, a3,…,an;

α1, α2, α3,…,αn;

Ф1, Ф2, Ф3,…,Фn и т. д.

Вспомогательная проекция точки, полученная в результате преобразования для получения действительной величины геометрической фигуры, обозначается той же буквой с подстрочным индексом 0:

A0, B0, С0, D0, …

Аксонометрические проекции

14. Аксонометрические проекции точек, линий, поверхностей обозначаются теми же буквами, что и натура с добавлением верхнего индекса 0:

А0, В0, С0, D0, …

10, 20, 30, 40, …

a0, b0, c0, d0, …

α0, β0, γ0, δ0, …

15. Вторичные проекции обозначаются путем добавления верхнего индекса 1 :

А1 0, В1 0, С1 0, D1 0, …

11 0, 21 0, 31 0, 41 0, …

a1 0, b1 0, c1 0, d1 0, …

α1 0, β1 0, γ1 0, δ1 0, …

Для облегчения чтения чертежей в учебнике при оформлении иллюстративного материала использованы несколько цветов, каждый из которых имеет определенное смысловое значение: линиями (точками) черного цвета обозначены исходные данные; зеленый цвет использован для линий вспомогательных графических построений; красными линиями (точками) показаны результаты построений или те геометрические элементы, на которые следует обратить особое внимание.

| № по пор. | Обозначение | Содержание | Пример символической записи |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≡ | Совпадают | (АВ)≡(CD) — прямая, проходящая через точки А и В, совпадает с прямой, проходящей через точки С и D |

| 2 | ≅ | Конгруентны | ∠ABC≅∠MNK — угол АВС конгруентен углу MNK |

| 3 | ∼ | Подобны | ΔАВС∼ΔMNK — треугольники АВС и MNK подобны |

| 4 | || | Параллельны | α||β — плоскость α параллельна плоскости β |

| 5 | ⊥ | Перпендикулярны | а⊥b — прямые а и b перпендикулярны |

| 6 |  |

Скрещиваются | с  d — прямые с и d скрещиваются d — прямые с и d скрещиваются |

| 7 |  |

Касательные | t  l — прямая t является касательной к линии l. l — прямая t является касательной к линии l. β  α — плоскость β касательная к поверхности α α — плоскость β касательная к поверхности α |

| 8 | → | Отображаются | Ф1→Ф2 — фигура Ф1 отображается на фигуру Ф2 |

| 9 | S | Центр проецирования. Если центр проецирования несобственная точка, то его положение обозначается стрелкой, указывающей направление проецирования |

— |

| 10 | s | Направление проецирования | — |

| 11 | P | Параллельное проецирование | рsα Параллельное проецирование — параллельное проецирование на плоскость α в направлении s |

| № по пор. | Обозначение | Содержание | Пример символической записи | Пример символической записи в геометрии |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M,N | Множества | — | — |

| 2 | A,B,C,… | Элементы множества |

— | — |

| 3 | { … } | Состоит из … | Ф{A, B, C,… } | Ф{A, B, C,… } — фигура Ф состоит из точек А, В,С, … |

| 4 | ∅ | Пустое множество | L — ∅ — множество L пустое (не содержит элементов ) | — |

| 5 | ∈ | Принадлежит, является элементом | 2∈N (где N — множество натуральных чисел) — число 2 принадлежит множеству N |

А ∈ а — точка А принадлежит прямой а (точка А лежит на прямой а ) |

| 6 | ⊂ | Включает, cодержит | N⊂М — множество N является частью (подмножеством) множества М всех рациональных чисел |

а⊂α — прямая а принадлежит плоскости α (понимается в смысле: множество точек прямой а является подмножеством точек плоскости α) |

| 7 | ∪ | Объединение | С = A U В — множество С есть объединение множеств A и В; {1, 2. 3, 4,5} = {1,2,3}∪{4,5} |

ABCD = [AB] ∪ [ВС] ∪ [CD] — ломаная линия, ABCD есть объединение отрезков [АВ], [ВС], [CD] |

| 8 | ∩ | Пересечение множеств | М=К∩L — множество М есть пересечение множеств К и L (содержит в себе элементы, принадлежащие как множеству К, так и множеству L). М ∩ N = ∅— пересечение множеств М и N есть пустое множество (множества М и N не имеют общих элементов) |

а = α ∩ β — прямая а есть пересечение плоскостей α и β а ∩ b = ∅ — прямые а и b не пересекаются (не имеют общих точек) |

| № по пор. | Обозначение | Содержание | Пример символической записи |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∧ | Конъюнкция предложений; соответствует союзу «и». Предложение (р∧q) истинно тогда и только тогда,когда р и q оба истинны |

α∩β = { К:K∈α∧K∈β} Пересечение поверхностей α и β есть множество точек (линия), состоящее из всех тех и только тех точек К, которые принадлежат как поверхности α, так и поверхности β |

| 2 | ∨ | Дизъюнкция предложений; соответствует союзу «или». Предложение (p∨q) истинно, когда истинно хотя бы одно из предложений р или q (т. е. или р, или q, или оба). |

— |

| 3 | ⇒ | Импликация — логическое следствие. Предложение р⇒q означает: «если р, то и q» | (а||с∧b||с)⇒a||b. Если две прямые параллельны третьей, то они параллельны между собой |

| 4 | ⇔ | Предложение (р⇔q) понимается в смысле: «если р, то и q; если q, то и р» | А∈α⇔А∈l⊂α. Точка принадлежит плоскости, если она принадлежит некоторой линии, принадлежащей этой плоскости. Справедливо также и обратное утверждение: если точка принадлежит некоторой линии, принадлежащей плоскости, то она принадлежит и самой плоскости |

| 5 | ∀ | Квантор общности, читается: для всякого, для всех, для любого. Выражение ∀(x)P(x) означает: «для всякого x: имеет место свойство Р(х) « |

∀( ΔАВС)( = 180°) Для всякого (для любого) треугольника сумма величин его углов = 180°) Для всякого (для любого) треугольника сумма величин его углов при вершинах равна 180° |

| 6 | ∃ | Квантор существования, читается: существует. Выражение ∃(х)P(х) означает: «существует х, обладающее свойством Р(х)» |

(∀α)(∃a)[a⊄α∧a||α].Для любой плоскости α существует прямая а, не принадлежащая плоскости α и параллельная плоскости α |

| 7 | ∃1 | Квантор единственности существования, читается: существует единственное (-я, -й)… Выражение ∃1(x)(Рх) означает: «существует единственное (только одно) х, обладающее свойством Рх» |

(∀ А, В)(А≠B)(∃1а)(а∋А, В) Для любых двух различных точек А и В существует единственная прямая a, проходящая через эти точки. |

| 8 | (Px) | Отрицание высказывания P(x) | а b(∃α)(α⊃а, Ь).Если прямые а и b скрещиваются, то не существует плоскости а, которая содержит их b(∃α)(α⊃а, Ь).Если прямые а и b скрещиваются, то не существует плоскости а, которая содержит их |

| 9 | Отрицание знака | [AB]≠[CD] —отрезок [АВ] не равен отрезку [CD].а?b — линия а не параллельна линии b |

Символьные обозначенияДля обозначения геометрических фигур и их проекций, для отображения отношения между геометрическими фигурами, а также для краткости записей геометрических предложений, алгоритмов решения задач и доказательства теорем используются символьные обозначения.

Символьные обозначения, все их многообразие, может быть подразделено на две группы: Символьные обозначения — Первая группа Символы, обозначающие геометрические фигуры и отношения между ними

Обозначения геометрических фигур:

O — точка пересечения осей проекций;

Проекции точек, линий, поверхностей любой геометрической фигуры обозначаются теми же буквами (или цифрами), что и оригинал, с добавлением верхнего индекса A`, A», A`» Символы взаиморасположения геометрических объектов

Символьные обозначения — Вторая группа Символы обозначающие логические операции

+ |

The red dot represents the point at which the two lines intersect.

In geometry, an intersection is a point, line, or curve common to two or more objects (such as lines, curves, planes, and surfaces). The simplest case in Euclidean geometry is the line–line intersection between two distinct lines, which either is one point or does not exist (if the lines are parallel). Other types of geometric intersection include:

- Line–plane intersection

- Line–sphere intersection

- Intersection of a polyhedron with a line

- Line segment intersection

- Intersection curve

Determination of the intersection of flats – linear geometric objects embedded in a higher-dimensional space – is a simple task of linear algebra, namely the solution of a system of linear equations. In general the determination of an intersection leads to non-linear equations, which can be solved numerically, for example using Newton iteration. Intersection problems between a line and a conic section (circle, ellipse, parabola, etc.) or a quadric (sphere, cylinder, hyperboloid, etc.) lead to quadratic equations that can be easily solved. Intersections between quadrics lead to quartic equations that can be solved algebraically.

On a plane[edit]

Two lines[edit]

For the determination of the intersection point of two non-parallel lines

one gets, from Cramer’s rule or by substituting out a variable, the coordinates of the intersection point

(If

Two line segments[edit]

Intersection of two line segments

For two non-parallel line segments

The line segments intersect only in a common point

The parameters

It can be solved for s and t using Cramer’s rule (see above). If the condition

Example: For the line segments

and

Remark: Considering lines, instead of segments, determined by pairs of points, each condition

A line and a circle[edit]

For the intersection of

one solves the line equation for x or y and substitutes it into the equation of the circle and gets for the solution (using the formula of a quadratic equation)

if

If

If the circle’s midpoint is not the origin, see.[1] The intersection of a line and a parabola or hyperbola may be treated analogously.

Two circles[edit]

The determination of the intersection points of two circles

can be reduced to the previous case of intersecting a line and a circle. By subtraction of the two given equations one gets the line equation:

This special line is the radical line of the two circles.

Intersection of two circles with centers on the x-axis, their radical line is dark red

Special case

In this case the origin is the center of the first circle and the second center lies on the x-axis (s. diagram). The equation of the radical line simplifies to

In case of

In case of

Any general case as written above can be transformed by a shift and a rotation into the special case.

The intersection of two disks (the interiors of the two circles) forms a shape called a lens.

circle–ellipse intersection

Two conic sections[edit]

The problem of intersection of an ellipse/hyperbola/parabola with another conic section leads to a system of quadratic equations, which can be solved in special cases easily by elimination of one coordinate. Special properties of conic sections may be used to obtain a solution. In general the intersection points can be determined by solving the equation by a Newton iteration. If a) both conics are given implicitly (by an equation) a 2-dimensional Newton iteration b) one implicitly and the other parametrically given a 1-dimensional Newton iteration is necessary. See next section.

Two smooth curves[edit]

A transversal intersection of two curves

touching intersection (left), touching (right)

Two curves in

have an intersection point, if they have a point of the plane in common and have at this point

- a: different tangent lines (transversal intersection), or

- b: the tangent line in common and they are crossing each other (touching intersection, see diagram).

If both the curves have a point S and the tangent line there in common but do not cross each other, they are just touching at point S.

Because touching intersections appear rarely and are difficult to deal with, the following considerations omit this case. In any case below all necessary differential conditions are presupposed. The determination of intersection points always leads to one or two non-linear equations which can be solved by Newton iteration. A list of the appearing cases follows:

intersection of a parametric curve and an implicit curve

intersection of two implicit curves

- If both curves are explicitly given:

, equating them yields the equation

- If both curves are parametrically given:

- Equating them yields two equations in two variables:

- If one curve is parametrically and the other implicitly given:

- This is the simplest case besides the explicit case. One has to insert the parametric representation of

into the equation

of curve

and one gets the equation:

- If both curves are implicitly given:

- Here, an intersection point is a solution of the system

Any Newton iteration needs convenient starting values, which can be derived by a visualization of both the curves. A parametrically or explicitly given curve can easily be visualized, because to any parameter t or x respectively it is easy to calculate the corresponding point. For implicitly given curves this task is not as easy. In this case one has to determine a curve point with help of starting values and an iteration. See

.[2]

Examples:

- 1:

and circle

(see diagram).

- The Newton iteration

for function

has to be done. As start values one can choose −1 and 1.5.

- The intersection points are: (−1.1073, −1.3578), (1.6011, 4.1046)

- The Newton iteration

- 2:

(see diagram).

- The Newton iteration

has to be performed, where

is the solution of the linear system

at point

. As starting values one can choose(−0.5, 1) and (1, −0.5).

- The linear system can be solved by Cramer’s rule.

- The intersection points are (−0.3686, 0.9953) and (0.9953, −0.3686).

Two polygons[edit]

intersection of two polygons: window test

If one wants to determine the intersection points of two polygons, one can check the intersection of any pair of line segments of the polygons (see above). For polygons with many segments this method is rather time-consuming. In practice one accelerates the intersection algorithm by using window tests. In this case one divides the polygons into small sub-polygons and determines the smallest window (rectangle with sides parallel to the coordinate axes) for any sub-polygon. Before starting the time-consuming determination of the intersection point of two line segments any pair of windows is tested for common points. See.[3]

In space (three dimensions)[edit]

In 3-dimensional space there are intersection points (common points) between curves and surfaces. In the following sections we consider transversal intersection only.

A line and a plane[edit]

The intersection of a line and a plane in general position in three dimensions is a point.

Commonly a line in space is represented parametrically

for parameter

If the linear equation has no solution, the line either lies on the plane or is parallel to it.

Three planes[edit]

If a line is defined by two intersecting planes

Three planes

For the proof one should establish

A curve and a surface[edit]

intersection of curve

Analogously to the plane case the following cases lead to non-linear systems, which can be solved using a 1- or 3-dimensional Newton iteration.[4]

- parametric curve

and

- parametric surface

- parametric curve

and

- implicit surface

Example:

- parametric curve

and

- implicit surface

(s. picture).

- The intersection points are: (−0.8587, 0.7374, −0.6332), (0.8587, 0.7374, 0.6332).

A line–sphere intersection is a simple special case.

Like the case of a line and a plane, the intersection of a curve and a surface in general position consists of discrete points, but a curve may be partly or totally contained in a surface.

A line and a polyhedron[edit]

Two surfaces[edit]

Two transversally intersecting surfaces give an intersection curve. The most simple case the intersection line of two non-parallel planes.

See also[edit]

- Analytic geometry#Intersections

- Computational geometry

- Equation of a line

- Intersection (set theory)

- Intersection theory

References[edit]

- ^ Erich Hartmann: Geometry and Algorithms for COMPUTER AIDED DESIGN. Lecture notes, Technische Universität Darmstadt, October 2003, p. 17

- ^ Erich Hartmann: Geometry and Algorithms for COMPUTER AIDED DESIGN. Lecture notes, Technische Universität Darmstadt, October 2003, p. 33

- ^ Erich Hartmann: CDKG: Computerunterstützte Darstellende und Konstruktive Geometrie. Lecture notes, TU Darmstadt, 1997, p. 79 (PDF; 3,4 MB)

- ^ Erich Hartmann: Geometry and Algorithms for COMPUTER AIDED DESIGN. Lecture notes, Technische Universität Darmstadt, October 2003, p. 93

Further reading[edit]

- Nicholas M. Patrikalakis and Takashi Maekawa, Shape Interrogation for Computer Aided Design and Manufacturing, Springer, 2002, ISBN 3540424547, 9783540424543, pp. 408. [1]

The red dot represents the point at which the two lines intersect.

In geometry, an intersection is a point, line, or curve common to two or more objects (such as lines, curves, planes, and surfaces). The simplest case in Euclidean geometry is the line–line intersection between two distinct lines, which either is one point or does not exist (if the lines are parallel). Other types of geometric intersection include:

- Line–plane intersection

- Line–sphere intersection

- Intersection of a polyhedron with a line

- Line segment intersection

- Intersection curve

Determination of the intersection of flats – linear geometric objects embedded in a higher-dimensional space – is a simple task of linear algebra, namely the solution of a system of linear equations. In general the determination of an intersection leads to non-linear equations, which can be solved numerically, for example using Newton iteration. Intersection problems between a line and a conic section (circle, ellipse, parabola, etc.) or a quadric (sphere, cylinder, hyperboloid, etc.) lead to quadratic equations that can be easily solved. Intersections between quadrics lead to quartic equations that can be solved algebraically.

On a plane[edit]

Two lines[edit]

For the determination of the intersection point of two non-parallel lines

one gets, from Cramer’s rule or by substituting out a variable, the coordinates of the intersection point

(If

Two line segments[edit]

Intersection of two line segments

For two non-parallel line segments

The line segments intersect only in a common point

The parameters

It can be solved for s and t using Cramer’s rule (see above). If the condition

Example: For the line segments

and

Remark: Considering lines, instead of segments, determined by pairs of points, each condition

A line and a circle[edit]

For the intersection of

one solves the line equation for x or y and substitutes it into the equation of the circle and gets for the solution (using the formula of a quadratic equation)

if

If

If the circle’s midpoint is not the origin, see.[1] The intersection of a line and a parabola or hyperbola may be treated analogously.

Two circles[edit]

The determination of the intersection points of two circles

can be reduced to the previous case of intersecting a line and a circle. By subtraction of the two given equations one gets the line equation:

This special line is the radical line of the two circles.

Intersection of two circles with centers on the x-axis, their radical line is dark red

Special case

In this case the origin is the center of the first circle and the second center lies on the x-axis (s. diagram). The equation of the radical line simplifies to

In case of

In case of

Any general case as written above can be transformed by a shift and a rotation into the special case.

The intersection of two disks (the interiors of the two circles) forms a shape called a lens.

circle–ellipse intersection

Two conic sections[edit]

The problem of intersection of an ellipse/hyperbola/parabola with another conic section leads to a system of quadratic equations, which can be solved in special cases easily by elimination of one coordinate. Special properties of conic sections may be used to obtain a solution. In general the intersection points can be determined by solving the equation by a Newton iteration. If a) both conics are given implicitly (by an equation) a 2-dimensional Newton iteration b) one implicitly and the other parametrically given a 1-dimensional Newton iteration is necessary. See next section.

Two smooth curves[edit]

A transversal intersection of two curves

touching intersection (left), touching (right)

Two curves in

have an intersection point, if they have a point of the plane in common and have at this point

- a: different tangent lines (transversal intersection), or

- b: the tangent line in common and they are crossing each other (touching intersection, see diagram).

If both the curves have a point S and the tangent line there in common but do not cross each other, they are just touching at point S.

Because touching intersections appear rarely and are difficult to deal with, the following considerations omit this case. In any case below all necessary differential conditions are presupposed. The determination of intersection points always leads to one or two non-linear equations which can be solved by Newton iteration. A list of the appearing cases follows:

intersection of a parametric curve and an implicit curve

intersection of two implicit curves

- If both curves are explicitly given:

, equating them yields the equation

- If both curves are parametrically given:

- Equating them yields two equations in two variables:

- If one curve is parametrically and the other implicitly given:

- This is the simplest case besides the explicit case. One has to insert the parametric representation of

into the equation

of curve

and one gets the equation:

- If both curves are implicitly given:

- Here, an intersection point is a solution of the system

Any Newton iteration needs convenient starting values, which can be derived by a visualization of both the curves. A parametrically or explicitly given curve can easily be visualized, because to any parameter t or x respectively it is easy to calculate the corresponding point. For implicitly given curves this task is not as easy. In this case one has to determine a curve point with help of starting values and an iteration. See

.[2]

Examples:

- 1:

and circle

(see diagram).

- The Newton iteration

for function

has to be done. As start values one can choose −1 and 1.5.

- The intersection points are: (−1.1073, −1.3578), (1.6011, 4.1046)

- The Newton iteration

- 2:

(see diagram).

- The Newton iteration

has to be performed, where

is the solution of the linear system

at point

. As starting values one can choose(−0.5, 1) and (1, −0.5).

- The linear system can be solved by Cramer’s rule.

- The intersection points are (−0.3686, 0.9953) and (0.9953, −0.3686).

Two polygons[edit]

intersection of two polygons: window test

If one wants to determine the intersection points of two polygons, one can check the intersection of any pair of line segments of the polygons (see above). For polygons with many segments this method is rather time-consuming. In practice one accelerates the intersection algorithm by using window tests. In this case one divides the polygons into small sub-polygons and determines the smallest window (rectangle with sides parallel to the coordinate axes) for any sub-polygon. Before starting the time-consuming determination of the intersection point of two line segments any pair of windows is tested for common points. See.[3]

In space (three dimensions)[edit]

In 3-dimensional space there are intersection points (common points) between curves and surfaces. In the following sections we consider transversal intersection only.

A line and a plane[edit]

The intersection of a line and a plane in general position in three dimensions is a point.

Commonly a line in space is represented parametrically

for parameter

If the linear equation has no solution, the line either lies on the plane or is parallel to it.

Three planes[edit]

If a line is defined by two intersecting planes

Three planes

For the proof one should establish

A curve and a surface[edit]

intersection of curve

Analogously to the plane case the following cases lead to non-linear systems, which can be solved using a 1- or 3-dimensional Newton iteration.[4]

- parametric curve

and

- parametric surface

- parametric curve

and

- implicit surface

Example:

- parametric curve

and

- implicit surface

(s. picture).

- The intersection points are: (−0.8587, 0.7374, −0.6332), (0.8587, 0.7374, 0.6332).

A line–sphere intersection is a simple special case.

Like the case of a line and a plane, the intersection of a curve and a surface in general position consists of discrete points, but a curve may be partly or totally contained in a surface.

A line and a polyhedron[edit]

Two surfaces[edit]

Two transversally intersecting surfaces give an intersection curve. The most simple case the intersection line of two non-parallel planes.

See also[edit]

- Analytic geometry#Intersections

- Computational geometry

- Equation of a line

- Intersection (set theory)

- Intersection theory

References[edit]

- ^ Erich Hartmann: Geometry and Algorithms for COMPUTER AIDED DESIGN. Lecture notes, Technische Universität Darmstadt, October 2003, p. 17

- ^ Erich Hartmann: Geometry and Algorithms for COMPUTER AIDED DESIGN. Lecture notes, Technische Universität Darmstadt, October 2003, p. 33

- ^ Erich Hartmann: CDKG: Computerunterstützte Darstellende und Konstruktive Geometrie. Lecture notes, TU Darmstadt, 1997, p. 79 (PDF; 3,4 MB)

- ^ Erich Hartmann: Geometry and Algorithms for COMPUTER AIDED DESIGN. Lecture notes, Technische Universität Darmstadt, October 2003, p. 93

Further reading[edit]

- Nicholas M. Patrikalakis and Takashi Maekawa, Shape Interrogation for Computer Aided Design and Manufacturing, Springer, 2002, ISBN 3540424547, 9783540424543, pp. 408. [1]