Arabic numerals are the ten symbols most commonly used to write decimal numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as computer symbols, trademarks, or license plates. The term often implies a decimal number, in particular when contrasted with Roman numerals.

They are also called Western Arabic numerals, Ghubār numerals, Hindu-Arabic numerals,[1] Western digits, Latin digits, or European digits.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary differentiates them with the fully capitalized Arabic Numerals to refer to the Eastern digits.[3] The term numbers or numerals or digits often implies only these symbols, however this can only be inferred from context.

Europeans learned of Arabic numerals about the 10th century, though their spread was a gradual process. Two centuries later, in the Algerian city of Béjaïa, the Italian scholar Fibonacci first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and colonialism helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary spread of the Latin alphabet, and have become common in the writing systems where other numeral systems existed previously, such as Chinese and Japanese numerals.

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

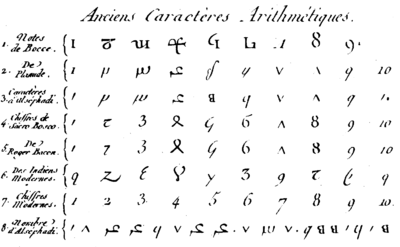

Evolution of Indian numerals into Arabic numerals and their adoption in Europe

The reason the digits are more commonly known as «Arabic numerals» in Europe and the Americas is that they were introduced to Europe in the 10th century by Arabic speakers of Spain and North Africa, who were then using the digits from Libya to Morocco. In the eastern part of Arabic Peninsula, Arabs were using the Eastern Arabic numerals or «Mashriki» numerals: ٠ ١ ٢ ٣ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ٨ ٩[a][4]

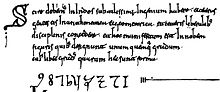

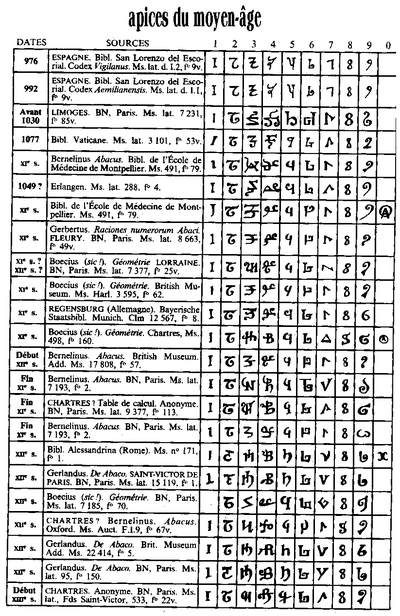

Al-Nasawi wrote in the early 11th century that mathematicians had not agreed on the form of the numerals, but most of them had agreed to train themselves with the forms now known as Eastern Arabic numerals.[5] The oldest specimens of the written numerals available are from Egypt and date to 873–874 CE. They show three forms of the numeral «2» and two forms of the numeral «3», and these variations indicate the divergence between what later became known as the Eastern Arabic numerals and the Western Arabic numerals.[6] The Western Arabic numerals came to be used in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus from the 10th century onward.[7] Some amount of consistency in the Western Arabic numeral forms endured from the 10th century, found in a Latin manuscript of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae from 976 and the Gerbertian abacus, into the 12th and 13th centuries, in early manuscripts of translations from the city of Toledo.[4]

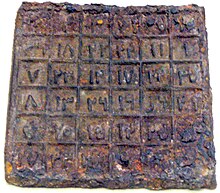

Calculations were originally performed using a dust board (takht, Latin: tabula), which involved writing symbols with a stylus and erasing them. The use of the dust board appears to have introduced a divergence in terminology as well: whereas the Hindu reckoning was called ḥisāb al-hindī in the east, it was called ḥisāb al-ghubār in the west (literally, «calculation with dust»).[8] The numerals themselves were referred to in the west as ashkāl al‐ghubār («dust figures») or qalam al-ghubår («dust letters»).[9] Al-Uqlidisi later invented a system of calculations with ink and paper «without board and erasing» (bi-ghayr takht wa-lā maḥw bal bi-dawāt wa-qirṭās).[10]

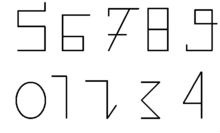

A popular myth claims that the symbols were designed to indicate their numeric value through the number of angles they contained, but no evidence exists of this, and the myth is difficult to reconcile with any digits past 4.[11]

Adoption and spread[edit]

The first mentions of the numerals from 1 to 9 in the West are found in the Codex Vigilanus of 976, an illuminated collection of various historical documents covering a period from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania.[12] Other texts show that numbers from 1 to 9 were occasionally supplemented by a placeholder known as sipos, represented as a circle or wheel, reminiscent of the eventual symbol for zero. The Arabic term for zero is sifr (صفر), transliterated into Latin as cifra, and the origin of the English word cipher.

From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later, Pope Sylvester II) used his position to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth. He was known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.[12]

The reception of Arabic numerals in the West was gradual and lukewarm, as other numeral systems circulated in addition to the older Roman numbers. As a discipline, the first to adopt Arabic numerals as part of their own writings were astronomers and astrologists, evidenced from manuscripts surviving from mid-12th-century Bavaria. Reinher of Paderborn (1140–1190) used the numerals in his calendrical tables to calculate the dates of Easter more easily in his text Compotus emendatus.[13]

Italy[edit]

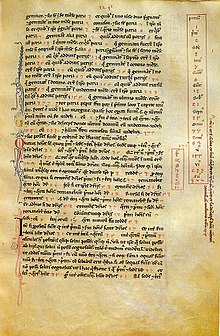

A page of the Liber Abaci. The list on the right shows the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377. The 2, 8, and 9 resemble Arabic numerals more than Eastern Arabic numerals or Indian numerals

Fibonacci, a mathematician from the Republic of Pisa who had studied in Béjaïa (Bugia), Algeria, promoted the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Europe with his 1202 book Liber Abaci:

When my father, who had been appointed by his country as public notary in the customs at Bugia acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians’ nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it.

The Liber Abaci introduced the huge advantages of a positional numeric system, and was widely influential. As Fibonacci used the symbols from Béjaïa for the digits, these symbols were also introduced in the same instruction, ultimately leading to their widespread adoption.[14]

Fibonacci’s introduction coincided with Europe’s commercial revolution of the 12th and 13th centuries, centered in Italy. Positional notation could be used for quicker and more complex mathematical operations (such as currency conversion) than Roman and other numeric systems could. They could also handle larger numbers, did not require a separate reckoning tool, and allowed the user to check a calculation without repeating the entire procedure.[14] Although positional notation opened possibilities that were hampered by previous systems, late medieval Italian merchants did not stop using Roman numerals (or other reckoning tools). Rather, Arabic numerals became an additional tool that could be used alongside others.[14]

Europe[edit]

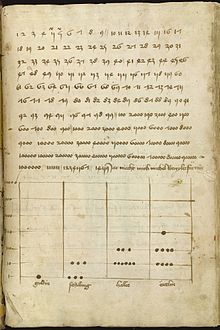

A German manuscript page teaching use of Arabic numerals (Talhoffer Thott, 1459). At this time, knowledge of the numerals was still widely seen as esoteric, and Talhoffer presents them with the Hebrew alphabet and astrology.

In the late 14th century only a few texts using Arabic numerals appeared outside of Italy. This suggests that the use of Arabic numerals in commercial practice, and the significant advantage they conferred, remained a virtual Italian monopoly until the late 15th century.[14] This may in part have been due to language – although Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci was written in Latin, the Italian abacus traditions was predominantly written in Italian vernaculars that circulated in the private collections of abacus schools or individuals. It was likely difficult for non-Italian merchant bankers to access comprehensive information.

The European acceptance of the numerals was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, and they became widely known during the 15th century. Their use grew steadily in other centers of finance and trade such as Lyon.[15] Early evidence of their use in Britain includes: an equal hour horary quadrant from 1396,[16] in England, a 1445 inscription on the tower of Heathfield Church, Sussex; a 1448 inscription on a wooden lych-gate of Bray Church, Berkshire; and a 1487 inscription on the belfry door at Piddletrenthide church, Dorset; and in Scotland a 1470 inscription on the tomb of the first Earl of Huntly in Elgin Cathedral.[17] In central Europe, the King of Hungary Ladislaus the Posthumous, started the use of Arabic numerals, which appear for the first time in a royal document of 1456.[18]

By the mid-16th century, they were in common use in most of Europe. Roman numerals remained in use mostly for the notation of Anno Domini years, and for numbers on clock faces.[citation needed] Other digits (such as Eastern Arabic) were virtually unknown.[citation needed]

Russia[edit]

Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals, Cyrillic numerals, derived from the Cyrillic alphabet, were used by South and East Slavic peoples. The system was used in Russia as late as the early 18th century, although it was formally replaced in official use by Peter the Great in 1699.[19] Reasons for Peter’s switch from the alphanumerical system are believed to go beyond his desire to imitate the West. Historian Peter Brown makes arguments for sociological, militaristic, and pedagogical reasons for the change. At a broad, societal level, Russian merchants, soldiers, and officials increasingly came into contact with counterparts from the West and became familiar with the communal use of Arabic numerals. Peter the Great also travelled incognito throughout Northern Europe from 1697 to 1698 during his Grand Embassy and was likely exposed to Western mathematics, if informally, during this time.[20] The Cyrillic numeric system was also inferior in terms of calculating properties of objects in motions, such as the trajectories and parabolic flight patterns of artillery. It was unable to keep pace with Arabic numerals in the growing science of ballistics, whereas Western mathematicians such as John Napier had been publishing on the topic since 1614.[21]

China[edit]

Chinese numeral systems that used positional notation (such as the counting rod system and Suzhou numerals) were in use in China preior to the introduction of Arabic numerals,[22][23] and some were introduced to medieval China by the Muslim Hui people. In the early 17th century, European-style Arabic numerals were introduced by Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits.[24][25][26]

Encoding[edit]

The ten Arabic numerals are encoded in virtually every character set designed for electric, radio, and digital communication, such as Morse code.

They are encoded in ASCII at positions 0x30 to 0x39. Masking to the lower four binary bits (or taking the last hexadecimal digit) gives the value of the digit, a great help in converting text to numbers on early computers. These positions were inherited in Unicode.[27] EBCDIC used different values, but also had the lower 4 bits equal to the digit value.

| ASCII Binary | ASCII Octal | ASCII Decimal | ASCII Hex | Unicode | EBCDIC Hex |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | U+0030 DIGIT ZERO | F0 |

| 1 | 0011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | U+0031 DIGIT ONE | F1 |

| 2 | 0011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | U+0032 DIGIT TWO | F2 |

| 3 | 0011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | U+0033 DIGIT THREE | F3 |

| 4 | 0011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | U+0034 DIGIT FOUR | F4 |

| 5 | 0011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | U+0035 DIGIT FIVE | F5 |

| 6 | 0011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | U+0036 DIGIT SIX | F6 |

| 7 | 0011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | U+0037 DIGIT SEVEN | F7 |

| 8 | 0011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | U+0038 DIGIT EIGHT | F8 |

| 9 | 0011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | U+0039 DIGIT NINE | F9 |

Comparison with other digits[edit]

| Symbol | Used with scripts | Numerals | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | many | Arabic numerals |

| 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 | Brahmi | Brahmi numerals |

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ | Devanagari | Devanagari numerals |

| ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | Bengali–Assamese | Bengali numerals |

| ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | Gurmukhi | Gurmukhi numerals |

| ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ | Gujarati | Gujarati numerals |

| ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ | Odia | Odia numerals |

| ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ | Santali | Santali numerals |

| 𑇐 | 𑇑 | 𑇒 | 𑇓 | 𑇔 | 𑇕 | 𑇖 | 𑇗 | 𑇘 | 𑇙 | Sharada | Sharada numerals |

| ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ | Tamil | Tamil numerals |

| ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ | Telugu | Telugu script § Numerals |

| ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ | Kannada | Kannada script § Numerals |

| ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ | Malayalam | Malayalam numerals |

| ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ | Sinhala | Sinhala numerals |

| ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ | Burmese | Burmese numerals |

| ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ | Tibetan | Tibetan numerals |

| ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | Mongolian | Mongolian numerals |

| ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ | Khmer | Khmer numerals |

| ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ | Thai | Thai numerals |

| ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ | Lao | Lao script § Numerals |

| ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ | Sundanese | Sundanese numerals |

| ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ | Javanese | Javanese numerals |

| ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ | Balinese | Balinese numerals |

| ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | Arabic | Eastern Arabic numerals |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Persian / Dari / Pashto | |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Urdu / Shahmukhi | |

| — | ፩ | ፪ | ፫ | ፬ | ፭ | ፮ | ፯ | ፰ | ፱ | Ethio-Semitic | Ge’ez numerals |

| 〇 | 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | East Asia | Chinese numerals |

See also[edit]

- Arabic numeral variations

- Regional variations in modern handwritten Arabic numerals

- Seven-segment display

- Text figures

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Shown right-to-left, zero is on the right, nine on the left.

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Arabic numeral». American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Terminology for Digits Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Unicode Consortium.

- ^ «Arabic», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ^ a b Burnett, Charles (2002). Dold-Samplonius, Yvonne; Van Dalen, Benno; Dauben, Joseph; Folkerts, Menso (eds.). From China to Paris: 2000 Years Transmission of Mathematical Ideas. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 237–288. ISBN 978-3-515-08223-5. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 7: «Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n’ont pas été d’accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d’entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit.»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 12–13: «While specimens of Western Arabic numerals from the early period—the tenth to thirteenth centuries—are still not available, we know at least that Hindu reckoning (called ḥisāb al-ghubār) was known in the West from the 10th century onward…»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ifrah, Georges (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer. Translated by David Bellos (from the French). London: Harvill Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9781860463242.

- ^ a b Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (3 May 2020). «Medieval Europe’s satanic ciphers: on the genesis of a modern myth». British Journal for the History of Mathematics. 35 (2): 107–136. doi:10.1080/26375451.2020.1726050. ISSN 2637-5451. S2CID 213113566.

- ^ Herold, Werner (2005). «Der «computus emendatus» des Reinher von Paderborn». ixtheo.de (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Danna, Raffaele (12 July 2021). The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Arithmetic: a Socio-Economic Perspective (13th–16th centuries) (Doctoral thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.72497. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Danna, Raffaele; Iori, Martina; Mina, Andrea (22 June 2022). «A Numerical Revolution: The Diffusion of Practical Mathematics and the Growth of Pre-modern European Economies». SSRN 4143442.

- ^ «14th century timepiece unearthed in Qld farm shed». ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ See G. F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, for more examples.

- ^ Erdélyi: Magyar művelődéstörténet 1-2. kötet. Kolozsvár, 1913, 1918.

- ^ Conatser Segura, Sylvia (26 May 2020). Orthographic Reform and Language Planning in Russian History (Honors thesis). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Brown, Peter B. (2012). «Muscovite Arithmetic in Seventeenth-Century Russian Civilization: Is It Not Time to Discard the «Backwardness» Label?». Russian History. 39 (4): 393–459. doi:10.1163/48763316-03904001. ISSN 0094-288X. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Lockwood, E. H. (October 1978). «Mathematical discoveries 1600-1750, by P. L. Griffiths. Pp 121. £2·75. 1977. ISBN 0 7223 1006 4 (Stockwell)». The Mathematical Gazette. 62 (421): 219. doi:10.2307/3616704. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3616704. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Shell-Gellasch, Amy (2015). Algebra in context : introductory algebra from origins to applications. J. B. Thoo. Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1728-8. OCLC 907657424.

- ^ Uy, Frederick L. (January 2003). «The Chinese Numeration System and Place Value». Teaching Children Mathematics. 9 (5): 243–247. doi:10.5951/tcm.9.5.0243. ISSN 1073-5836. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Helaine Selin, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Meuleman, Johan H. (2002). Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity. Psychology Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7007-1691-3. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Peng Yoke Ho (2000). Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ «The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0» (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2001. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2003). «The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered». In J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Burnett, Charles (2006). «The Semantics of Indian Numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin». Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer-Netherlands. 34 (1–2): 15–30. doi:10.1007/s10781-005-8153-z. S2CID 170783929.

- Hayashi, Takao (1995). The Bakhshālī Manuscript: An Ancient Indian Mathematical Treatise. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten. ISBN 906980087X.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000). A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to Computers. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471393401.

- Katz, Victor J., ed. (20 July 2007). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691114859.

- «Mathematics in South Asia». Nature. 189 (4761): 273. 1961. Bibcode:1961Natur.189S.273.. doi:10.1038/189273c0. S2CID 4288165.

- Ore, Oystein (1988). «Hindu-Arabic numerals». Number Theory and Its History. Dover. pp. 19–24. ISBN 0486656209.

External links[edit]

- Lam Lay Yong, «Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic», Chinese Science 13 (1996): 35–54.

- «Counting Systems and Numerals», Historyworld. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- The Evolution of Numbers. 16 April 2005.

- O’Connor, J. J., and E. F. Robertson, Indian numerals Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. November 2000.

- History of the numerals

- Arabic numerals

- Hindu-Arabic numerals

- Numeral & Numbers’ history and curiosities

- Gerbert d’Aurillac’s early use of Hindu-Arabic numerals at Convergence

Arabic numerals are the ten symbols most commonly used to write decimal numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as computer symbols, trademarks, or license plates. The term often implies a decimal number, in particular when contrasted with Roman numerals.

They are also called Western Arabic numerals, Ghubār numerals, Hindu-Arabic numerals,[1] Western digits, Latin digits, or European digits.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary differentiates them with the fully capitalized Arabic Numerals to refer to the Eastern digits.[3] The term numbers or numerals or digits often implies only these symbols, however this can only be inferred from context.

Europeans learned of Arabic numerals about the 10th century, though their spread was a gradual process. Two centuries later, in the Algerian city of Béjaïa, the Italian scholar Fibonacci first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and colonialism helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary spread of the Latin alphabet, and have become common in the writing systems where other numeral systems existed previously, such as Chinese and Japanese numerals.

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

Evolution of Indian numerals into Arabic numerals and their adoption in Europe

The reason the digits are more commonly known as «Arabic numerals» in Europe and the Americas is that they were introduced to Europe in the 10th century by Arabic speakers of Spain and North Africa, who were then using the digits from Libya to Morocco. In the eastern part of Arabic Peninsula, Arabs were using the Eastern Arabic numerals or «Mashriki» numerals: ٠ ١ ٢ ٣ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ٨ ٩[a][4]

Al-Nasawi wrote in the early 11th century that mathematicians had not agreed on the form of the numerals, but most of them had agreed to train themselves with the forms now known as Eastern Arabic numerals.[5] The oldest specimens of the written numerals available are from Egypt and date to 873–874 CE. They show three forms of the numeral «2» and two forms of the numeral «3», and these variations indicate the divergence between what later became known as the Eastern Arabic numerals and the Western Arabic numerals.[6] The Western Arabic numerals came to be used in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus from the 10th century onward.[7] Some amount of consistency in the Western Arabic numeral forms endured from the 10th century, found in a Latin manuscript of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae from 976 and the Gerbertian abacus, into the 12th and 13th centuries, in early manuscripts of translations from the city of Toledo.[4]

Calculations were originally performed using a dust board (takht, Latin: tabula), which involved writing symbols with a stylus and erasing them. The use of the dust board appears to have introduced a divergence in terminology as well: whereas the Hindu reckoning was called ḥisāb al-hindī in the east, it was called ḥisāb al-ghubār in the west (literally, «calculation with dust»).[8] The numerals themselves were referred to in the west as ashkāl al‐ghubār («dust figures») or qalam al-ghubår («dust letters»).[9] Al-Uqlidisi later invented a system of calculations with ink and paper «without board and erasing» (bi-ghayr takht wa-lā maḥw bal bi-dawāt wa-qirṭās).[10]

A popular myth claims that the symbols were designed to indicate their numeric value through the number of angles they contained, but no evidence exists of this, and the myth is difficult to reconcile with any digits past 4.[11]

Adoption and spread[edit]

The first mentions of the numerals from 1 to 9 in the West are found in the Codex Vigilanus of 976, an illuminated collection of various historical documents covering a period from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania.[12] Other texts show that numbers from 1 to 9 were occasionally supplemented by a placeholder known as sipos, represented as a circle or wheel, reminiscent of the eventual symbol for zero. The Arabic term for zero is sifr (صفر), transliterated into Latin as cifra, and the origin of the English word cipher.

From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later, Pope Sylvester II) used his position to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth. He was known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.[12]

The reception of Arabic numerals in the West was gradual and lukewarm, as other numeral systems circulated in addition to the older Roman numbers. As a discipline, the first to adopt Arabic numerals as part of their own writings were astronomers and astrologists, evidenced from manuscripts surviving from mid-12th-century Bavaria. Reinher of Paderborn (1140–1190) used the numerals in his calendrical tables to calculate the dates of Easter more easily in his text Compotus emendatus.[13]

Italy[edit]

A page of the Liber Abaci. The list on the right shows the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377. The 2, 8, and 9 resemble Arabic numerals more than Eastern Arabic numerals or Indian numerals

Fibonacci, a mathematician from the Republic of Pisa who had studied in Béjaïa (Bugia), Algeria, promoted the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Europe with his 1202 book Liber Abaci:

When my father, who had been appointed by his country as public notary in the customs at Bugia acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians’ nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it.

The Liber Abaci introduced the huge advantages of a positional numeric system, and was widely influential. As Fibonacci used the symbols from Béjaïa for the digits, these symbols were also introduced in the same instruction, ultimately leading to their widespread adoption.[14]

Fibonacci’s introduction coincided with Europe’s commercial revolution of the 12th and 13th centuries, centered in Italy. Positional notation could be used for quicker and more complex mathematical operations (such as currency conversion) than Roman and other numeric systems could. They could also handle larger numbers, did not require a separate reckoning tool, and allowed the user to check a calculation without repeating the entire procedure.[14] Although positional notation opened possibilities that were hampered by previous systems, late medieval Italian merchants did not stop using Roman numerals (or other reckoning tools). Rather, Arabic numerals became an additional tool that could be used alongside others.[14]

Europe[edit]

A German manuscript page teaching use of Arabic numerals (Talhoffer Thott, 1459). At this time, knowledge of the numerals was still widely seen as esoteric, and Talhoffer presents them with the Hebrew alphabet and astrology.

In the late 14th century only a few texts using Arabic numerals appeared outside of Italy. This suggests that the use of Arabic numerals in commercial practice, and the significant advantage they conferred, remained a virtual Italian monopoly until the late 15th century.[14] This may in part have been due to language – although Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci was written in Latin, the Italian abacus traditions was predominantly written in Italian vernaculars that circulated in the private collections of abacus schools or individuals. It was likely difficult for non-Italian merchant bankers to access comprehensive information.

The European acceptance of the numerals was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, and they became widely known during the 15th century. Their use grew steadily in other centers of finance and trade such as Lyon.[15] Early evidence of their use in Britain includes: an equal hour horary quadrant from 1396,[16] in England, a 1445 inscription on the tower of Heathfield Church, Sussex; a 1448 inscription on a wooden lych-gate of Bray Church, Berkshire; and a 1487 inscription on the belfry door at Piddletrenthide church, Dorset; and in Scotland a 1470 inscription on the tomb of the first Earl of Huntly in Elgin Cathedral.[17] In central Europe, the King of Hungary Ladislaus the Posthumous, started the use of Arabic numerals, which appear for the first time in a royal document of 1456.[18]

By the mid-16th century, they were in common use in most of Europe. Roman numerals remained in use mostly for the notation of Anno Domini years, and for numbers on clock faces.[citation needed] Other digits (such as Eastern Arabic) were virtually unknown.[citation needed]

Russia[edit]

Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals, Cyrillic numerals, derived from the Cyrillic alphabet, were used by South and East Slavic peoples. The system was used in Russia as late as the early 18th century, although it was formally replaced in official use by Peter the Great in 1699.[19] Reasons for Peter’s switch from the alphanumerical system are believed to go beyond his desire to imitate the West. Historian Peter Brown makes arguments for sociological, militaristic, and pedagogical reasons for the change. At a broad, societal level, Russian merchants, soldiers, and officials increasingly came into contact with counterparts from the West and became familiar with the communal use of Arabic numerals. Peter the Great also travelled incognito throughout Northern Europe from 1697 to 1698 during his Grand Embassy and was likely exposed to Western mathematics, if informally, during this time.[20] The Cyrillic numeric system was also inferior in terms of calculating properties of objects in motions, such as the trajectories and parabolic flight patterns of artillery. It was unable to keep pace with Arabic numerals in the growing science of ballistics, whereas Western mathematicians such as John Napier had been publishing on the topic since 1614.[21]

China[edit]

Chinese numeral systems that used positional notation (such as the counting rod system and Suzhou numerals) were in use in China preior to the introduction of Arabic numerals,[22][23] and some were introduced to medieval China by the Muslim Hui people. In the early 17th century, European-style Arabic numerals were introduced by Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits.[24][25][26]

Encoding[edit]

The ten Arabic numerals are encoded in virtually every character set designed for electric, radio, and digital communication, such as Morse code.

They are encoded in ASCII at positions 0x30 to 0x39. Masking to the lower four binary bits (or taking the last hexadecimal digit) gives the value of the digit, a great help in converting text to numbers on early computers. These positions were inherited in Unicode.[27] EBCDIC used different values, but also had the lower 4 bits equal to the digit value.

| ASCII Binary | ASCII Octal | ASCII Decimal | ASCII Hex | Unicode | EBCDIC Hex |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | U+0030 DIGIT ZERO | F0 |

| 1 | 0011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | U+0031 DIGIT ONE | F1 |

| 2 | 0011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | U+0032 DIGIT TWO | F2 |

| 3 | 0011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | U+0033 DIGIT THREE | F3 |

| 4 | 0011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | U+0034 DIGIT FOUR | F4 |

| 5 | 0011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | U+0035 DIGIT FIVE | F5 |

| 6 | 0011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | U+0036 DIGIT SIX | F6 |

| 7 | 0011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | U+0037 DIGIT SEVEN | F7 |

| 8 | 0011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | U+0038 DIGIT EIGHT | F8 |

| 9 | 0011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | U+0039 DIGIT NINE | F9 |

Comparison with other digits[edit]

| Symbol | Used with scripts | Numerals | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | many | Arabic numerals |

| 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 | Brahmi | Brahmi numerals |

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ | Devanagari | Devanagari numerals |

| ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | Bengali–Assamese | Bengali numerals |

| ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | Gurmukhi | Gurmukhi numerals |

| ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ | Gujarati | Gujarati numerals |

| ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ | Odia | Odia numerals |

| ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ | Santali | Santali numerals |

| 𑇐 | 𑇑 | 𑇒 | 𑇓 | 𑇔 | 𑇕 | 𑇖 | 𑇗 | 𑇘 | 𑇙 | Sharada | Sharada numerals |

| ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ | Tamil | Tamil numerals |

| ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ | Telugu | Telugu script § Numerals |

| ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ | Kannada | Kannada script § Numerals |

| ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ | Malayalam | Malayalam numerals |

| ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ | Sinhala | Sinhala numerals |

| ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ | Burmese | Burmese numerals |

| ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ | Tibetan | Tibetan numerals |

| ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | Mongolian | Mongolian numerals |

| ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ | Khmer | Khmer numerals |

| ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ | Thai | Thai numerals |

| ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ | Lao | Lao script § Numerals |

| ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ | Sundanese | Sundanese numerals |

| ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ | Javanese | Javanese numerals |

| ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ | Balinese | Balinese numerals |

| ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | Arabic | Eastern Arabic numerals |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Persian / Dari / Pashto | |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Urdu / Shahmukhi | |

| — | ፩ | ፪ | ፫ | ፬ | ፭ | ፮ | ፯ | ፰ | ፱ | Ethio-Semitic | Ge’ez numerals |

| 〇 | 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | East Asia | Chinese numerals |

See also[edit]

- Arabic numeral variations

- Regional variations in modern handwritten Arabic numerals

- Seven-segment display

- Text figures

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Shown right-to-left, zero is on the right, nine on the left.

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Arabic numeral». American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Terminology for Digits Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Unicode Consortium.

- ^ «Arabic», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ^ a b Burnett, Charles (2002). Dold-Samplonius, Yvonne; Van Dalen, Benno; Dauben, Joseph; Folkerts, Menso (eds.). From China to Paris: 2000 Years Transmission of Mathematical Ideas. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 237–288. ISBN 978-3-515-08223-5. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 7: «Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n’ont pas été d’accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d’entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit.»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 12–13: «While specimens of Western Arabic numerals from the early period—the tenth to thirteenth centuries—are still not available, we know at least that Hindu reckoning (called ḥisāb al-ghubār) was known in the West from the 10th century onward…»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ifrah, Georges (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer. Translated by David Bellos (from the French). London: Harvill Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9781860463242.

- ^ a b Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (3 May 2020). «Medieval Europe’s satanic ciphers: on the genesis of a modern myth». British Journal for the History of Mathematics. 35 (2): 107–136. doi:10.1080/26375451.2020.1726050. ISSN 2637-5451. S2CID 213113566.

- ^ Herold, Werner (2005). «Der «computus emendatus» des Reinher von Paderborn». ixtheo.de (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Danna, Raffaele (12 July 2021). The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Arithmetic: a Socio-Economic Perspective (13th–16th centuries) (Doctoral thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.72497. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Danna, Raffaele; Iori, Martina; Mina, Andrea (22 June 2022). «A Numerical Revolution: The Diffusion of Practical Mathematics and the Growth of Pre-modern European Economies». SSRN 4143442.

- ^ «14th century timepiece unearthed in Qld farm shed». ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ See G. F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, for more examples.

- ^ Erdélyi: Magyar művelődéstörténet 1-2. kötet. Kolozsvár, 1913, 1918.

- ^ Conatser Segura, Sylvia (26 May 2020). Orthographic Reform and Language Planning in Russian History (Honors thesis). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Brown, Peter B. (2012). «Muscovite Arithmetic in Seventeenth-Century Russian Civilization: Is It Not Time to Discard the «Backwardness» Label?». Russian History. 39 (4): 393–459. doi:10.1163/48763316-03904001. ISSN 0094-288X. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Lockwood, E. H. (October 1978). «Mathematical discoveries 1600-1750, by P. L. Griffiths. Pp 121. £2·75. 1977. ISBN 0 7223 1006 4 (Stockwell)». The Mathematical Gazette. 62 (421): 219. doi:10.2307/3616704. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3616704. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Shell-Gellasch, Amy (2015). Algebra in context : introductory algebra from origins to applications. J. B. Thoo. Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1728-8. OCLC 907657424.

- ^ Uy, Frederick L. (January 2003). «The Chinese Numeration System and Place Value». Teaching Children Mathematics. 9 (5): 243–247. doi:10.5951/tcm.9.5.0243. ISSN 1073-5836. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Helaine Selin, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Meuleman, Johan H. (2002). Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity. Psychology Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7007-1691-3. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Peng Yoke Ho (2000). Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ «The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0» (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2001. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2003). «The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered». In J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Burnett, Charles (2006). «The Semantics of Indian Numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin». Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer-Netherlands. 34 (1–2): 15–30. doi:10.1007/s10781-005-8153-z. S2CID 170783929.

- Hayashi, Takao (1995). The Bakhshālī Manuscript: An Ancient Indian Mathematical Treatise. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten. ISBN 906980087X.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000). A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to Computers. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471393401.

- Katz, Victor J., ed. (20 July 2007). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691114859.

- «Mathematics in South Asia». Nature. 189 (4761): 273. 1961. Bibcode:1961Natur.189S.273.. doi:10.1038/189273c0. S2CID 4288165.

- Ore, Oystein (1988). «Hindu-Arabic numerals». Number Theory and Its History. Dover. pp. 19–24. ISBN 0486656209.

External links[edit]

- Lam Lay Yong, «Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic», Chinese Science 13 (1996): 35–54.

- «Counting Systems and Numerals», Historyworld. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- The Evolution of Numbers. 16 April 2005.

- O’Connor, J. J., and E. F. Robertson, Indian numerals Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. November 2000.

- History of the numerals

- Arabic numerals

- Hindu-Arabic numerals

- Numeral & Numbers’ history and curiosities

- Gerbert d’Aurillac’s early use of Hindu-Arabic numerals at Convergence

Арабские цифры (шрифт без засечек)

| Системы счисления в культуре | |

|---|---|

| Индо-арабская система счисления | |

| Арабская Индийские Тамильская Бирманская |

Кхмерская Лаоская Монгольская Тайская |

| Восточноазиатские системы счисления | |

| Китайская Японская Сучжоу Корейская |

Вьетнамская Счётные палочки |

| Алфавитные системы счисления | |

| Абджадия Армянская Ариабхата Кириллическая |

Греческая Эфиопская Еврейская Катапаяди |

| Другие системы | |

| Вавилонская Египетская Этруская Римская |

Аттическая Кипу Майская |

| Позиционные системы счисления | |

| Десятичная система счисления (10) | |

| 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 16, 20, 60 | |

| Нега-позиционная система счисления | |

| Симметричная система счисления | |

| Смешанные системы счисления | |

| Фибоначчиева система счисления | |

| Непозиционные системы счисления | |

| Единичная (унарная) система счисления | |

| Список систем счисления |

Арабские цифры — традиционное название набора из десяти знаков: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9; ныне использующегося в большинстве стран для записи чисел в десятичной системе счисления.

История

Арабские цифры. Цифры 4, 5 и 6 существуют в двух вариантах, слева — арабский, справа — персидский.

Индийские цифры возникли в Индии не позднее V века. Тогда же было открыто и формализовано понятие нуля (шунья), которое позволило перейти к позиционной записи чисел.

Арабские и индо-арабские цифры являются видоизменёнными начертаниями индийских цифр, приспособленными к арабскому письму[1].

Индийскую систему записи широко популяризировал учёный ал-Хорезми, автор знаменитой работы «Китаб аль-джебр ва-ль-мукабала», от названия которой произошёл термин «алгебра».

Арабские цифры стали известны европейцам в X веке. Благодаря тесным связям христианской Барселоны (Барселонское графство) и мусульманской Кордовы (Кордовский халифат), Сильвестр II (папа римский с 999 по 1003 годы) имел возможность доступа к научной информации, которой не имел никто в тогдашней Европе. В частности, он одним из первых среди европейцев познакомился с арабскими цифрами, понял удобство их употребления по сравнению с римскими цифрами и начал всячески пропагандировать их внедрение в европейскую науку.

| Арабские цифры, используемые в арабских странах Африки (кроме Египта) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Индо-арабские цифры, используемые в арабских странах Азии и в Египте | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ |

| Персидские цифры | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ |

| Индийские цифры (в письме деванагари), используемые в Индии | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Цифры в письме гуджарати | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ |

| Цифры в письме гурмукхи | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Цифры в письме лимбу (Limbu) | ᥆ | ᥇ | ᥈ | ᥉ | ᥊ | ᥋ | ᥌ | ᥍ | ᥎ | ᥏ |

| Цифры в бенгальском письме | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Цифры в письме ория | ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

| Цифры в письме телугу | ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| Цифры в письме каннада | ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ |

| Цифры в письме малаялам | ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ |

| Цифры в тамильском письме | ೦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ |

| Цифры в тибетском письме | ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ |

| Цифры в бирманском письме | ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ |

| Цифры в тайском письме | ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ |

| Цифры в кхмерском письме | ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ |

| Цифры в лаосском письме | ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ |

Одна из легенд происхождения начертания современных арабских цифр[2]. Количество углов соответствует числовому значению цифры.

|

|

|

Название «арабские цифры» образовалось исторически, из-за того что именно арабы распространяли десятичную позиционную систему счисления. Цифры, которые используют в арабских странах, по начертанию сильно отличаются от используемых в европейских странах.

Примечания

- ↑ وجهات النظر حول أصل الأرقام ا&# … (ар.)

- ↑ Florian Cajori A History of Mathematical Notations. — Cosimo, Inc., 2007. — Vol. I. — P. 64-66. — ISBN 9781602066847

Ссылки

- Арабские цифры // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: В 86 томах (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- «Арабские цифры» в Большой советской энциклопедии

- Титло — переводчик национальных начертаний арабских и других чисел

- Арабские цифры, использующиеся при датировке ковров

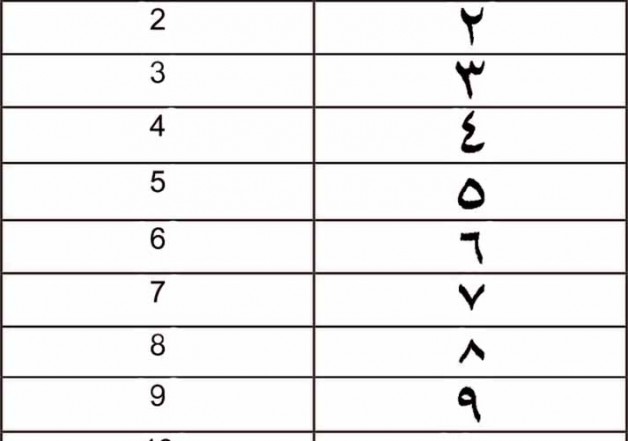

Арабский язык указан как один из самых сложных для изучения языков, но понимать числа очень просто. Арабский — это официальный и со-официальный язык из двадцати шести стран, и на нем говорят более чем 420 millones людей.

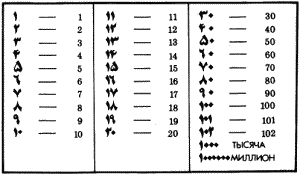

Структура написания этих чисел на арабском языке имеет больше смысла, чем на испанском. Поэтому их изучение может быть для вас не таким сложным. Вам следует знать кое-что интересное, что Арабские цифры или индо-арабские цифры, пришли из Индия, сотни лет назад.

Со временем они распространились по остальным арабским странам, а затем и по всему миру. Сегодня используется арабская система счисления, потому что она более легко чем остальные. Это позиционная система нумерации, которая включает: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 и 9.

Есть арабы, которые пишут такие числа, а есть другие, которые этого не делают. Они используют арабские числа, которые мы вам покажем позже. Важно, чтобы вы выучили другой способ письма. В арабских странах он не используется в полной мере, но подготовиться к нему не помешает.

В этой статье мы покажем вам Кардинальные и порядковые числа. При этом вам будет достаточно еще немного овладеть языком. В конце концов, мы оставим вам немного Ejemplos полезно для вас, чтобы просмотреть то, что вы узнали.

Содержание

- 1 Кардинальные числа на арабском языке

- 1.1 Арабские цифры от 0 до 20

- 2 Порядковые числа на арабском языке

- 3 Примеры фраз с цифрами на арабском языке

Кардинальные числа на арабском языке

Кардинальные числа на арабском языке, которые используются для счета, вы должны узнать из 0 20 к из памяти.

Чтобы сформировать больше чисел, как и в других языках, вы собираетесь составить композицию между единицы и десятки.

Арабские цифры от 0 до 20

Мы представим вам эти первые числа в формате: число — число на арабском языке (цифры) — произношение — число на арабском языке (буквы).

- 0 — ٠ — sifr — رٌ

- 1 — ١ — wahid — واحد

- 2 — ٢ — ithnan — نان

- 3 — ٣ — thalatha — ثلاثة

- 4 — ٤ — arba’a — أربع

- 5 — ٥ — khamsa — خمسة

- 6 — ٦ — ситта — ستة

- 7 — ٧ — sab’a — سبعة

- 8 — ٨ — thamaniya — مانية

- 9 — ٩ — tis’a — تسعة

- 10 — ١٠ — ‘ашра — عشرة

- 11 — ١١ — ahada ‘ashar — احد عشر

- 12 — ١٢ — ithna ‘ashar — اثنا عشر

- 13 — ١٣ — thalatha ‘ashar — ثلاثة عشر

- 14 — ١٤ — arba’a ‘ashar — اربعة عشر

- 15 — ١٥ — khamsa ‘ashar — خمسة عشر

- 16 — ١٦ — sitta ‘ashar — ستة عشر

- 17 — ١٧ — sab’a ‘ashar — سبعة عشر

- 18 — ١٨ — thamaniya ‘ashar — ثمانية عشر

- 19 — ١٩ — tis’a ‘ashar — تسعة عشر

- 20 — ٢٠ — ‘ishrun — عرون

Цифровые числа в арабском языке немного похожи на обычные: ٠, ١, ٢, ٣, ٤, ٥, ٦, ٧, ٨ и ٩.

И написание, обозначающее большее количество чисел, такое же. Например, число 21 пишется «٢١». Так и с остальным.

Объяснить, как они написаны (عرون), сложнее. Поэтому мы только покажем вам уже написанное, не объясняя, как это сделать.

Первый двадцать одно число, От 0 до 20, они имеют уникальные имена. Запомни их. Вы также увидите другие со своими именами.

Остальные — это комбинации между десятки и единицы, по крайней мере, так было до 99 года.

Посмотрите на все десятки по-арабски:

- 10 — ١٠ — ‘ашра — عشرة

- 20 — ٢٠ — ‘ishrun — عرون

- 30 — thalathun — لاثون

- 40 — ٤٠ — arba’un — أربعون

- 50 — ٥٠ — khamsun — خمسون

- 60 — ٦٠ — sittun — ستون

- 70 — ٧٠ — sab’un — سبعون

- 80 — ٨٠ — thamanun — مانون

- 90 — ٩٠ — tis’un — تسعون

Обратите внимание, что из второй десятки это те же единицы, заканчивающиеся на «а», с их исключения. Вот как их следует произносить.

Для записи чисел в диапазоне десятков после 20 необходимо использовать соединитель «Ва» (و). И поставьте сначала единицу, а потом десятку.

Например, тридцать три будут выглядеть так: три тридцать по арабски.

Посмотрите, как написаны числа от 20 до 29.

- 21 — ٢١ — wahid wa-‘ishroun — واحد وعشرون

- 22 — ٢٢ — isnan wa-‘ishroun — إثنان وعشرون

- 23 — ٢٣ — Salasah wa-‘ishroun — ثلاثة وعشرين

- 24 — ٢٤ — arbah’ah wa-‘ishroun — أربع وعشرين

- 25 — ٢٥ — hamsah wa-‘ishroun — خمسة وعشرين

- 26 — ٢٦ — sittah wa-‘ishroun — ستة وعشرين

- 27 — ٢٧ — sab’ah wa-‘ishroun — سبعة وعشرون

- 28 — ٢٨ — samaniyah wa-‘ishroun — ثمانية وعشرين

- 29 — ٢٩ — tis’ah wa-‘ishroun — تسعة وعشرون

Вы должны сохранить этот же образец для остальных чисел. до 99 лет. Далее мы покажем вам список с остальными числами от 30 до 99 на арабском языке.

С 30 до 39.

- 30 — لاثون

- 31 — واحد وثلاثون

- 32 — اثنان وثلاثون

- 33 — لاثة وثلاثون

- 34 — ربعة وثلاثون

- 35 — مسة وثلاثون

- 36 — ستة وثلاثون

- 37 — سبعة وثلاثون

- 38 — مانية وثلاثون

- 39 — تسعة وثلاثون

С 40 до 49.

- 40 — ربعون

- 41 — واحد وأربعون

- 42 — اثنان واربعون

- 43 — لاثة وأربعون

- 44 — ربعة وأربعون

- 45 — مسة وأربعون

- 46 — ستة وأربعون

- 47 — سبعة واربعون

- 48 — مانية واربعون

- 49 — تسعة وأربعون

С 50 до 59.

- 50 — مسون

- 51 — واحد وخمسون

- 52 — اثنان وخمسون

- 53 — لاثة وخمسون

- 54 — الرابعة والخمسون

- 55 — مسة وخمسون

- 56 — ستة وخمسون

- 57 — سبعة وخمسون

- 58 — مانية وخمسون

- 59 — تسعة وخمسون

С 60 до 69.

- 60 — ستون

- 61 — واحد وستون

- 62 — انان وستون

- 63 — لاثة وستون

- 64 — ربعة وستون

- 65 — مسة وستون

- 66 — ستة وستون

- 67 — سبعة وستون

- 68 — مانية وستون

- 69 — تسعة وستون

С 70 до 79.

- 70 — سبعون

- 71 — واحد وسبعون

- 72 — انان وسبعون

- 73 — لاثة وسبعون

- 74 — ربعة وسبعون

- 75 — مسة وسبعون

- 76 — ستة وسبعون

- 77 — سبعة وسبعون

- 78 — مانية وسبعون

- 79 — تسعة وسبعون

С 80 до 89.

- 80 — مانون

- 81 — واحد وثمانون

- 82 — اثنان وثمانون

- 83 — لاثة وثمانون

- 84 — ربعة وثمانون

- 85 — مسة وثمانون

- 86 — ستة وثمانون

- 87 — سبعة وثمانون

- 88 — مانية وثمانون

- 89 — تسعة وثمانون

С 90 до 99.

- 90 — تسعين

- 91 — واحد وتسعون

- 92 — انان وتسعون

- 93 — لاثة وتسعون

- 94 — ربعة وتسعون

- 95 — مسة وتسعون

- 96 — ستة وتسعون

- 97 — سبعة وتسعون

- 98 — مانية وتسعون

- 99 — تسعة وتسعون

Остальные большие числа отсутствуют, например сотни и тысячи.

- 100 — miaya — مائة

- 1 000 — ‘альф — لف

- 100 000 — miayat ‘alf — مائة الف

- 1 000 000 — милюн — مليون

Со всеми теми, которые мы вам показали, вам просто нужно объединить их так же, как мы делали раньше, чтобы сформировать другие числа.

- 200 — مائتان

- 343 — لاث مئة وثلاثة واربعون

- 1 020 — الف وعشرين

- 34 000 — اربعة وثلاثون الف

- 950 230 — تسعمائة الف ومائتان وثلاثون

- 20 200 000 — عرون مليون ومئتان لف

- 90 000 001 — واحد وتسعين مليون

Порядковые числа на арабском языке

Порядковые числа в арабском языке имеют форму «فَاعِل», за исключением первый и второй, которые нерегулярны.

Мы оставим вам список с первые 20 порядковых номеров так что вы познакомитесь с ними.

- 1-й. — ولا

- 2-й. — في المرتبة الثانية

- 3-й. — لث

- 4-й. — رابع

- 5-е. — خامس

- 6-е. — سادس

- 7-е. — سابع

- 8-е. — امن

- 9-е. — تاسع

- 10-е. — عشر

- 11-е. — العاشر الاول

- 12-е. — Я الثاني عشر

- 13-е. — الثالث عشر

- 14-го. — الرابع عشر

- 15 °. — الخامس عشر

- 16-го. — سادس عشر

- 17-е. — في السابع عشر

- 18-е. — الثامن عشر

- 19-е. — التاسع عشر

- 20 °. — عرون

Примеры фраз с цифрами на арабском языке

- там двадцать коровы на ферме — ناك عشرين بقرة في المزرعة

- Tengo три красные шары и внутри желтый — لدي ثلاث كرات حمراء واثنتان صفراء

- там тринадцать студенты курса — هناك ثلاثة عشر طالبا في الدورة

- оставаться шесть позиции на лодке — ناك ستة أماكن اليسار على متن القارب

- я третий прибыть — أنا الثالث للوصول

- она ферма девушка — هي الفتاة الخامسة

- Я остался первый в турнире — كنت الأول في البطولة

- является седьмой встреча года — هذا هو الاجتماع السابع لهذا العام

↓ СОДЕРЖАНИЕ СТАТЬИ: ↓

- Цифры от 1 до 10 на арабском языке

- Количественные числительные от 11 до 19

- Числительные круглых десятков

- Числительные круглых сотен

- Числительные круглых тысяч

- Числительные круглых десятков тысяч

- Числительные круглых сотен тысяч

- Египетский фунт — названия бумажных денег и монет

Слова в арабском языке пишутся справа налево, а вот числа — как и привычно нам — слева направо.

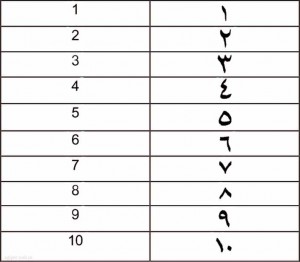

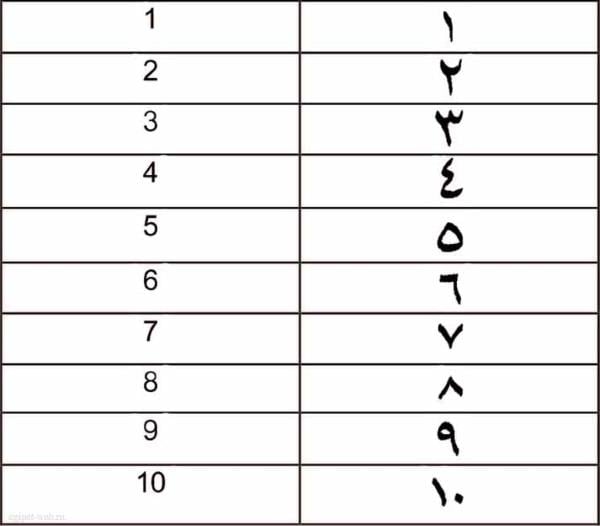

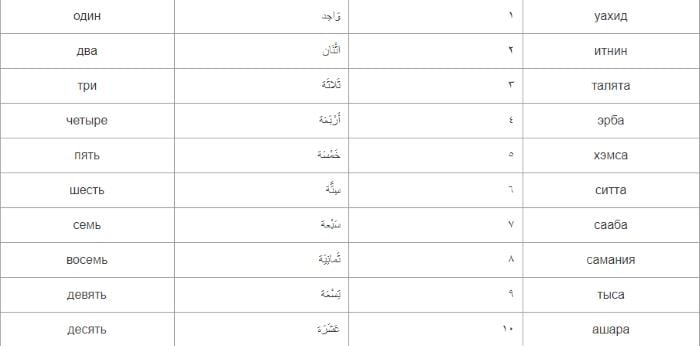

Цифры от 1 до 10 на арабском языке

| Русский | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| один | وَاحِد | ١ | уахид |

| два | اثْنَان | ٢ | итнин |

| три | ثَلاثَة | ٣ | талята |

| четыре | أَرْبَعَة | ٤ | эрба |

| пять | خَمْسَة | ٥ | хэмса |

| шесть | سِتَّة | ٦ | ситта |

| семь | سَبْعة | ٧ | сааба |

| восемь | ثَمانِيَة | ٨ | самания |

| девять | تِسْعَة | ٩ | тыса |

| десять | عَشَرَة | ١٠ | ашара |

Количественные числительные от 11 до 19

| Русский | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| одиннадцать | أَحَدَ عَشَرَ | ١١ | ахда ашер |

| двенадцать | اِثْنا عَشَرَ | ١٢ | итнин ашер |

| тринадцать | ثَلاثَ عَشْرَة | ١٣ | талята ашер |

| четырнадцать | أَرْبَعَ عَشْرَة | ١٤ | эрба ашер |

| пятнадцать | خ َمْسَ عَشْرَة |

١٥ | хэмса ашер |

| шестнадцать | سِتَّ عَشْرَة | ١٦ | ситта ашер |

| семнадцать | سَبْع عَشْرَة | ١٧ | сааба ашер |

| восемнадцать | ثَمانِيَ عَشْرَة | ١٨ | самания ашер |

| девятнадцать | تِسْعَ عَشْرَة | ١٩ | тыса ашер |

Числительные круглых десятков

| Русский | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| десять | عَشَرَة | ١٠ | ашара |

| двадцать | اعِشْرُون | ٢٠ | ашрин |

| тридцать | ثلاثون | ٣٠ | талятин |

| сорок | أَرْبَعُون | ٤٠ | арбаин |

| пятьдесят | خَمْسُون | ٥٠ | хамсин |

| шестьдесят | ستون | ٦٠ | ситтин |

| семьдесят | سَبْعُونَ | ٧٠ | сабаин |

| восемьдесят | ثَمَانُونَ | ٨٠ | саманин |

| девяносто | تِسْعُونَ | ٩٠ | тысин |

Числительные круглых сотен

| Русский | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| сто | مِائَة | ١٠٠ | ми’а |

| двести | مِائَتَيْنْ | ٢٠٠ | ми’атейн |

| триста (три сотни) | ثَلاثْ مِائَة | ٣٠٠ | саляс ми’а |

| четыреста (четыре сотни) | ﺁﺭﺒﻤﻴﺔ | ٤٠٠ | эрба ми’а |

| пятьсот (пять сотен) | ﺨﻤﺴﻤﻴﺔ | ٥٠٠ | хэмса ми’а |

| шестьсот (шесть сотен) | ﺴﺘﻤﻴﺔ | ٦٠٠ | ситта ми’а |

| семьсот (семь сотен) | ﺴﺒﻌﻤﻴﺔ | ٧٠٠ | сабаа ми’а |

| восемьсот (восемь сотен) | ﺘﻤﻨﻤﻴﺔ | ٨٠٠ | томму ми’а |

| девятьсот (девять сотен) | ﺘﺴﻌﻤﻴﺔ | ٩٠٠ | тыс’а ми’а |

Числительные круглых тысяч

| Число | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 000 | ﺁﻟﻒ | ١٠٠٠ | альф |

| 2 000 | ﺁﻟﻓﻴﻦ | ٢٠٠٠ | альфейн |

| 3 000 | ﺘﻟﺘﻼﻒ | ٣٠٠٠ | талет талеф |

| 4 000 | ﺁﺮﺒﻌﺘﻼﻒ | ٤٠٠٠ | арбаа талеф |

| 5 000 | ﺨﻤﺴﺘﻼﻒ | ٥٠٠٠ | хамса талеф |

| 6 000 | ﺴﺘﻼﻒ | ٦٠٠٠ | сит талеф |

| 7 000 | ﺴﺒﻌﻼﻒ | ٧٠٠٠ | сабаа талеф |

| 8 000 | ﺘﻤﻨﺘﻼﻒ | ٨٠٠٠ | таман талеф |

| 9 000 | ﺘﺴﻌﺘﻼﻒ | ٩٠٠٠ | тысса талеф |

Числительные круглых десятков тысяч

| Русский | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 000 | ﻋﺸﺮﺘﻼﻒ | ١٠٠٠٠ | ашр талеф |

| 11 000 | ﺤﺪﺍﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١١٠٠٠ | хэдашр альф |

| 12 000 | ﺍﺘﻨﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٢٠٠٠ | итнашр альф |

| 13 000 | ﺘﻠﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٣٠٠٠ | таляташр альф |

| 14 000 | ﺁﺭﺒﻌﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٤٠٠٠ | арбаташр альф |

| 15 000 | ﺤﻤﺴﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٥٠٠٠ | хамасташр альф |

| 16 000 | ﺴﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٦٠٠٠ | ситташр альф |

| 17 000 | ﺴﺒﻌﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٧٠٠٠ | сабаташр альф |

| 18 000 | ﺘﻤﻨﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٨٠٠٠ | таманташр альф |

| 19 000 | ﺘﺴﻌﺘﺎﺸﺭﺁﻠﻑ | ١٩٠٠٠ | тыссаташр альф |

| 20 000 | ﻋﺸﺭﻴﻦﺁﻠﻑ | ٢٠٠٠٠ | ашриин альф |

| 30 000 | ﺘﻼﺘﻴﻦﺁﻠﻑ | ٣٠٠٠٠ | талятин альф |

| 40 000 | ﺁﺭﺒﻌﻴﻦﺁﻠﻑ | ٤٠٠٠٠ | арбаин альф |

| 50 000 | ﺤﻤﺴﻴﻦﺁﻠﻑ | ٥٠٠٠٠ | хамсин альф |

| 60 000 | ﺴﺘﻴﻦ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٦٠٠٠٠ | ситтин альф |

| 70 000 | ﺴﺒﻴﻦﺁﻠﻑ | ٧٠٠٠٠ | сабаин альф |

| 80 000 | ﺘﻤﻨﻴﻦ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٨٠٠٠٠ | таманин альф |

| 90 000 | ﺘﺴﻌﻴﻦ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٩٠٠٠٠ | тыссаин альф |

Числительные круглых сотен тысяч

| Русский | Арабский (прописью) | Арабский (число) | Как произносить |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 000 | ﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ١٠٠٠٠٠ | мит альф |

| 200 000 | ﻤﺘﻴﻦ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٢٠٠٠٠٠ | митейн альф |

| 300 000 | ﺘﻟﺘﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٣٠٠٠٠٠ | тульту мит альф |

| 400 000 | ﺭﺒﻌﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٤٠٠٠٠٠ | робу мит альф |

| 500 000 | ﺤﻤﺴﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٥٠٠٠٠٠ | хомсу мит альф |

| 600 000 | ﺴﺘﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٦٠٠٠٠٠ | ситу мит альф |

| 700 000 | ﺴﺒﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٧٠٠٠٠٠ | собу мит альф |

| 800 000 | ﺘﻤﻭﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٨٠٠٠٠٠ | тому мит альф |

| 900 000 | ﺘﺴﻌﻤﻴﺖ ﺁﻠﻑ | ٩٠٠٠٠٠ | тысса мит альф |

Египетский фунт — названия бумажных денег и монет

Подробная статья про египетские деньги с фотографиями здесь: Деньги Египта.

| Русский | Арабский (число) | Как произносить (масри) |

|---|---|---|

| 200 фунтов | ٢٠٠ | ми’атейн гине |

| 100 фунтов | ١٠٠ | ми’а гине |

| 50 фунтов | ٥٠ | хамсин гине |

| 20 фунтов | ٢٠ | ашрин гине |

| 10 фунтов | ١٠ | ашер гине |

| 5 фунтов | ٥ | хэмса гине |

| 1 фунт | ١ | уахид гине |

| 50 пиастров | ٥٠ | нысф гине (хамсин эрш) |

| 25 пиастров | ٢٥ | хэмс-ашрин эрш |

| 75 пиастров | ٧٥ | хэмс-саабаин эрш |

| 1 фунт 25 пиастров | гине уа хэмс-ашрин эрш |

Числительные в арабский язык пришли из Индии, хотя цифрами привычного нам вида (1, 2, 3 и т.д.) пользуется весь мир, при этом почему-то называя их арабскими. В отличие от слов, пишущихся «справа налево» арабские цифры пишутся наоборот — «слева направо», что является лучшим доказательством заимствованности системы счёта от чуждой арабам культуры, а заодно и выдаёт тайну истоков происхождения цивилизации «серой подрасы» из Индии. При этом весь неарабский мир продолжает упорно не замечать факт чуждости для планеты Земля самой арабской цивилизации, отличающейся не только письменностью, но также устройством общества и семьи, религией, жизненными ценностями, принципами жизни и отношением к другим народам.

Фактов хватает, об этом будет написана отдельная статья, а пока, так как мы продолжаем ездить отдыхать на Красное море, придётся учить арабские цифры и числа на арабском языке.

Числительные, арабские цифры — египетский (каирский) диалект

Арабские цифры от 1 до 10

В египетском языке существуют количественные и порядковые числительные. Количественные числительные свободно употребляются вместо порядковых. Существуют некоторые диалектические вариации произношения, не имеющие принципиального значения и понятные всем арабам (примерно как разница между произношениями украинского и русского языков: одын, один, одыныця, единица) . Для полного раскрытия темы здесь указаны и вариации.

Знак «’» обозначает ударение.

Количественные числительные

- 1 — ва’хид, уа’хид

- 2 — итни’н, этни’н, этни’йн

- 3 — тале’та, таля’та

- 4 — арба’а

- 5 — ха’мса

- 6 — сы’тта, си’тта

- 7 — са’баа

- 8 — тама’ния, тамэ’ния

- 9 — ты’сса, ти’съа

- 10 — а’шара, а’шэра, а’шра

Единица в сочетании с именем мужского рода звучит «ва’хид», в сочетании с именем женского рода — «ва’хида». Остальные количественные числительные применяются без изменений, независимо от рода.

Числительные от 11 до 19 применяются с исчисляемым именем в единственном числе, по родам не изменяются.

- 11 — хэда’шар, хада’шр, хидаа’шар

- 12 — итна’шар, итна’шр, итнаа’шар

- 13 — талята’шар, талята’шр, тляттаа’шар

- 14 — арбаата’шар, арбаата’шр

- 15 — хамста’шар, хамаста’шр, хамастаа’шар

- 16 — ситта’шар, ситта’шр, ситтаа’шар

- 17 — сабаата’шар, сабаата’шр, сабаата’шар

- 18 — таманта’шар, таманта’шр, тмантаа’шар

- 19 — тиссата’шар, тисъата’шр, тэсаата’шар, тсаата’шар

Десятки

- 20 — ашри’н, эшри’н

- 30 — таляти’н, талети’н

- 40 — арбаи’н

- 50 — хамси’н

- 60 — сытти’н, ситти’н

- 70 — сабаи’н

- 80 — тамэни’н, тамани’н

- 90 — тиссаи’н, тисъаи’н

Сотни

- 100 — ми’йя, ме’йа

- 200 — митти’н, мите’йн

- 300 — ту’льта ми’йя, ту’льта ме’йа

- 400 — арба’ ми’йя, арба’ ме’йа, урба’ ми’йя

- 500 — хо’мсу ми’йя, хо’мсу ме’йа

- 600 — си’та ми’йя, си’та ме’йа

- 700 — са’баа ми’йя, са’баа ме’йа

- 800 — то’му ми’йя, то’мму ме’йа

- 900 — ты’сса ми’йя, ти’съа ме’йа

Тысячи

- 1 000 — альф

- 2 000 — альфе’йн, альфе’йин, итне’йн альф

- 3 000 — тале’т тале’ф, таля’т тале’ф, таляталя’ф

- 4 000 — арба’а тале’ф, арбааталя’ф

- 5 000 — ха’мса тале’ф, хамс тале’ф, хама’сталяф

- 6 000 — сит тале’ф, си’тталяф

- 7 000 — са’баа тале’ф, са’бааталяф

- 8 000 — тама’н тале’ф, тама’нияталяф

- 9 000 — ты’сса тале’ф, та’съа тале’ф, ти’сааталяф

- 10 000 — ашр тале’ф, а’шараталяф

- 11 000 — хэда’шр альф, хада’шр альф

- 12 000 — итна’шр альф

- 13 000 — талята’шр альф

- 14 000 — арбата’шр альф

- 15 000 — хамаста’шр альф, хамста’шр альф

- 16 000 — ситта’шр альф

- 17 000 — сабата’шр альф

- 18 000 — таманта’шр альф

- 19 000 — тыссата’шр альф, тисъата’шр альф

- 20 000 — ашри’ин альф, а’шрин альф

- 30 000 — таляти’н альф, т’лятин альф

- 40 000 — арбаи’н альф

- 50 000 — хамси’н альф

- 60 000 — ситти’н альф

- 70 000 — сабаи’н альф

- 80 000 — тамани’н альф

- 90 000 — тыссаи’н альф, тисъаи’н альф

- 100 000 — мит альф

- 200 000 — мите’йн альф

- 300 000 — ту’льту мит альф

- 400 000 — ро’бу мит альф

- 500 000 — хо’мсу мит альф

- 600 000 — си’ту мит альф

- 700 000 — со’бу мит альф

- 800 000 — то’му мит альф

- 900 000 — ты’сса мит альф, ти’съа мит альф

- 1 000 000 — мильу’н, мильё’н

- 2 000 000 — итни’ин мильу’н

- …

- 1 000 000 000 — милиа’р

Множественное число для миллиона — «мильуи’нин».

Чаще говорят «этн’ийн мильуи’нин», «таля’та мильуи’нин», т.е. «два миллионов, три …». Хотя граматически правильно нужно говорить «этни’йн мильу’н».

Правила числительных

Числительные от 21 содержат связующий элемент «уау», встречается произношение «ва», «уи», «уа», «у»:

- 21 — ва’хид ва ашри’н, уа’хид уау (уи) ашри’н, ва’хед у ашри’н

- 22 — этни’н ва ашри’н, этни’йн уау (уи) ашри’н, итнэ’йн у ашри’н

- 23 — тале’та ва ашри’н, таля’та уау (уи) ашри’н

- 24 — арба’ ва ашри’н, арба’ уи (уи) ашри’н

- 25 — ха’мса ва ашри’н, ха’мса уау (уи) ашри’н

- 26 — сы’тта ва ашри’н, си’тта уау (уи) ашри’н

- 27 — са’баа ва ашри’н, са’баа уау (уи) ашри’н

- 28 — тамэ’ния ва ашри’н, тама’ния уау (уи) ашрин

- 29 — ты’сса ва ашри’н, ти’съа уау (уи) ашри’н

- 30 — талети’н, таляти’н

- 31 — ва’хид ва таляти’н, уахид уау (уи) талети’н

- 32 — этни’н ва таляти’н, этнийн уау (уи) талети’н

- …

Числительные сотен:

- 101 — ми’йя у ва’хид, ми’йя ва ва’хид, ме’йя уи уа’хид

- 102 — ми’йя ва итни’н, ме’йя уи этни’йн

- 103 — ми’йя ва тале’та, ме’йя уи таля’та

- 104 — ми’йя ва арба’а, ме’йя уи арба’а

- 105 — ми’йя ва ха’мса, ме’йя уи ха’мса

- 106 — ми’йя ва сы’тта, ме’йя уи си’тта

- 107 — ми’йя ва са’баа, ме’йя уи са’баа

- 108 — ми’йя ва тамэ’ния, ме’йя уи тама’ния

- 109 — ми’йя ва ты’сса, ме’йя уи ти’съа

- 110 — ми’йя ва а’шэра, мейя уи ашра

- 120 — ми’йя ва эшри’н, мейя уи ашрин

- 130 — ми’йя ва талети’н, мейя уи талятин

- 140 — ми’йя ва арбаи’н, мейя уи арбаи’н

- 150 — ми’йя ва хамси’н, мейя уи хамсин

- 160 — ми’йя ва сытти’н, мейя уи ситтин

- 170 — ми’йя ва сабаи’н, мейя уи сабаи’н

- 180 — ми’йя ва тамэни’н, мейя уи тамани’н

- 190 — ми’йя ва тиссаи’н, мейя уи тисъаи’н

- 200 — митти’н, мите’йн

- 201 — митти’н ва ва’хид, мите’йн уи уахид

- 202 — митти’н ва итни’н, мите’йн уи этни’йн

- …

В сложных комбинациях после второй сотни происходит перенос связующего предлога-элемента «уау», «ва», «уи», «уа» и последующего числительного единиц-десятков за пределы числительного сотен-тысяч:

355 — ту’льту ме’йя хамса ва хамси’н

2216 — альфе’йн мите’йн уау ситта’шар

4555 — арба’а тале’ф хомсуме’йя ха’мса уау хамси’н

5555 — хамс тале’ф хомсуме’йя ха’мса ва хамси’н

6890 — сит тале’ф то’му ми’йя уау тисъаи’н

Формы порядковых числительных

- первый — авва’ль, ауа’ль

- первая — у’ля

- второй — та’ни, тэ’ни

- вторая — та’ния

- третий — та’лит

- третья — та’льта

- четвертый — ра’би

- четвертая — ра’биа

- пятый — ха’мис

- пятая — ха’миса

- шестой — са’тис, са’дис

- шестая — са’тса, са’дса, са’диса

- седьмой — са’би

- седьмая — са’биа

- восьмой — та’мин

- восьмая — та’мина, та’мна

- девятый — та’съи, та’си

- девятая — та’съиа, та’сиа

- десятый — а’шир

- десятая — а’шира

- 11-й — ха’ди ашир

- 11-я — ха’дия а’шира

- 12-й — та’ни а’шир

- 12-я — та’ния а’шира

- 13-й — та’лят а’шир, та’лит а’шир

- 13-я — та’лята а’шира, та’лита а’шира

- 14-й — ра’би а’шир

- 14-я — ра’биа а’шира

- 15-й — ха’мис а’шир

- 15-я — ха’миса а’шира

- 16-й — са’тис а’шир, са’дис а’шир

- 16-я — са’тиса а’шира, са’диса а’шира

- 17-й — са’би а’шир

- 17-я — са’биа а’шира

- 18-й — та’мин а’шир

- 18-я — та’мина а’шира

- 19-й — та’съи а’шир, та’си а’шир

- 19-я — та’съиа а’шира, та’сиа а’шира

- …

Дальнейшие числительные по аналогичной схеме.

В десятках женского рода окончание не меняется, изменяются только единицы:

- 21-й — ха’ди уи ашри’н, та’ни у ашри’н

- 21-я — ха’дия уи ашри’н, та’ния у ашри’н

- 22-й — та’ни уи ашри’н, та’ни у ашри’н

- 22-я — та’ниа уи ашри’н, та’ния у ашри’н

- 23-й — та’лит уи ашри’н, та’лит у ашри’н

- 23-я — та’лита уи ашри’н, та’лита у ашри’н

- …

Примечание:

Порядковое числительное «сатиса» — «шестая» может произноситься как «сатса», «тамина» «восьмая» — как «тамна», то есть происходит упущение гласного звука.

Порядковые числительные применяются в качестве вводных слов:

- во-первых — а’вваллян, а’уаллян

- во-вторых — тани’ян

- в-третьих — тали’тян

- в-четвертых — раби’ан

- в-пятых — хамси’ан

- в-шестых — сади’сан, сати’сан

- в-седьмых — саби’ан

- в–восьмых — тами’нан

- в девятых — таси’ан, тисъан

- в-десятых — аши’ран

- в-одиннадцатых — ха’дия аши’ран

Для полноты обзора арабских цифр и египетских числительных назову ещё дробные:

- четверть — ро’ба

- половина — нос

Ну и конечно же важнейшая арабская цифра 0 — ноль — цифр, пишется как наша точка.

Создатель блога Египет web, Олег.

Видеоролик для арабских детей: Арабские цифры от 1 до 10.

Цифры по египетски от 0 до 1000.

Цифры и буквы являются народным достоянием и имеют большую историю во всех народах мира. Самые распространенные на сегодняшний день числовые знаки — это арабские и римские. И те, и другие используют для создания списков в русском языке, для счета предметов и для математических вычислений. Из этой статьи вы узнаете все об арабских цифрах в диапазоне от 1 до 10.

Содержание

- История появления арабских цифр

- Откуда взялись современные числовые знаки от 1 до 10

- Особенности арабской цифры 0 (ноль)

- Использование нуля в расчетах

История появления арабских цифр

Арабские числовые знаки были выдуманы и записаны в Индии, произошло это около 5 века. В это время был определен отсчет чисел при перечислении. Отправной точкой был ноль (оригинальное название шунья). Это число позволило сформировать нынешний порядок чисел при счете. Популяризацией арабских цифр занимался индийский ученый того времени Абу Аль-Хорезми, который создал несколько книг на эту тему. От одной из них произошло сегодняшнее название школьного предмета — алгебра. Предоставленный ученым способ записи числовых значений использовал десятичную систему.

Археологи находили разные работы древних математиков и археологов, которые использовали арабские цифры для своих работ. Эти работы были созданы предположительно в 8-9 веке. Сегодня большинство арабских стран используют отличительную от привычной всем записи чисел в европейских и других регионах. Более того, на Востоке принято писать порядок чисел с права налево.

Существует множество мнений, что в формировании цифр арабского происхождения, которыми пользуемся сегодня мы — 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, были использованы не только арабские цифры древней Индии. Посмотрев на таблицу арабских цифр в диапазоне от 1 до 10 старого и нового представления, можно найти множество сходств. Например, 1, 2, 3, 4 в начальном представлении — это те же знаки, только повернутые на 90 градусов.

Читайте также: Рандомайзер чисел онлайн.

Откуда взялись современные числовые знаки от 1 до 10

Зарождение арабских цифр относят к древней южной Индии. Во многих древних странах, когда еще не было письма, использовались для счета палочки. Одна палочка обозначала 1, две — 2 и так далее. Такой способ записи навеян зарубками. Именно отсюда и происходят числа в римском представлении (для цифр 1, 2, 3). Индийские цифры позаимствовали некоторые элементы буквы из разных стран того времени.

В цифрах встречаются признаки букв арамейского, греческого и финикийского алфавитов. Предположительно числовые знаки начали зарождаться во 2 веке до нашей эры, в то время, когда существовало Индо-греческое царство.

В отличие от счета в русском языке — один (1), два (2), три (3), арабские цифры имеют свое название:

- 1 (один) — 1 Уахид;

- 2 (два) — 2 Итнан;

- 3 (три) — 3 Талата;

- 4 (четыре) — 4 Арба-а;

- 5 (пять) — 5 Хамиза;

- 6 (шесть) — 6 Ситта;

- 7 (семь) — 7 Саба-а;

- 8 (восемь) — 8 Таманиа;

- 9 (девять) — 9 Тизза;

- 10 (десять) — 10 Ашара.

Особенности арабской цифры 0 (ноль)

Ноль понимается как отсутствие числового значения или разряда. Ноль — очень полезная цифра хотя бы тем, что позволяет производить вычисления в столбик. Ни в одной другой числовой системе нет возможности это сделать. Чтобы убедиться в этом, попробуйте сделать расчет в столбик, используя римские цифры. Ноль придумали тоже индийцы и названа была эта цифра «сунья». На индийском значит — «пустой». В древних арабских странах этот знак еще называли cifra.

Российский математик и педагог Магницкий называет ноль также — цифра или ничто. Часто её название использовали для первой страницы книг. Есть и другие источники, в которых можно найти старое название 0 — цифра. Чаще всего оно встречается в рукописях русских и европейских ученых 17-18 века.

Это может быть полезным: Лучшие генераторы случайных чисел для конкурса.

Использование нуля в расчетах

Детей в школе учат начинать отсчет с единицы. Но большинство программистов используют вычисления, где отсчет всегда начинается с нуля. Такая запись всех 10 чисел удобна тем, что для их представления используется только 1 символ. А экономия в программировании является неотъемлемой его частью. Если мы начнем отсчет с нуля, записывать цифру 10 нам не нужно. Её место занимает девятка.

Ноль обладает другими интересными свойствами при взаимодействии с числами. Так, если вы попытаетесь прибавить к нулю или отнять ноль от какого-нибудь числа — оно не изменится. Когда производится умножение на это число — вы получите 0 во всех случаях. При возведении каждого числа в ноль, получится единица. А также на ноль (0) нельзя разделить другое целое или дробное число.

Существует Закон Бенфорда. Если не вдаваться в подробности с рассмотрением формул и таблиц, он гласит, что в реальной жизни цифры от 1 до 4 встретить гораздо вероятнее, чем цифры от 5 до 9. Сюда можно отнести номера домов улиц, различную статистику и тому подобное. Есть у этого закона и практическое применение. Используя его, можно проверять бухгалтерские отчетности, результаты голосований, подсчет расходов.

В некоторых американских штатах несоответствие каких-либо расчетов по Закону Бенфорда является уликой, имеющей вес в судебном процессе. Все расчеты по этому закону производятся в десятичной системе. Таким образом, арабские цифры в границе от 1 до 10 являются самыми распространенными во всем мире.