| Юлианская дата | Григорианская дата | Разница |

|---|---|---|

| с 1582, 5.10 по 1700, 18.02 | 1582, 15.10 – 1700, 28.02 | 10 дней |

| с 1700, 19.02 по 1800, 18.02 | 1700, 1.03 – 1800, 28.02 | 11 дней |

| с 1800, 19.02 по 1900, 18.02 | 1800, 1.03 – 1900, 28.02 | 12 дней |

| с 1900, 19.02 по 2100, 18.02 | 1900, 1.03 – 2100, 28.02 | 13 дней |

В Европе, начиная с 1582 года, постепенно распространился григорианский календарь. В год введения нового календаря было пропущено 10 дней (вместо 5 октября стали считать 15 октября). В дальнейшем новый календарь пропускал високосы в годах, оканчивающихся на «00», кроме тех случаев, когда первые две цифры такого года образуют число, кратное «4».

В Российском государстве григорианский календарь был введен с 1 февраля 1918 года, которое стало считаться 14 февраля «по новому стилю». Русская Православная Церковь продолжает жить по юлианскому календарю.

* * *

Как правильно переводить исторические даты из старого стиля в новый?

Казалось, бы, всё просто: надо воспользоваться тем правилом, которое действовало в данную эпоху. Например, если событие произошло в XVI–XVII веках, прибавлять 10 дней, если в XVIII веке – 11, в XIX веке – 12, наконец, в XX и XXI веках – 13 дней.

Так и делается обычно в западной литературе, и это вполне справедливо в отношении дат из истории Западной Европы. При этом следует помнить, что переход на григорианский календарь происходил в разных странах в разное время.

Однако ситуация меняется, когда речь заходит о событиях русской истории. В православных странах при датировании того или иного события уделялось внимание не только собственно числу месяца, но и обозначению этого дня в церковном календаре (празднику, памяти святого). Между тем церковный календарь не подвергся никаким изменениям, и Рождество, к примеру, как праздновалось 25 декабря 300 или 200 лет назад, так празднуется в этот же день и теперь. Иное дело, что в гражданском «новом стиле» этот день обозначается как «7 января».

При переводе дат праздников и памятных дней на новый стиль Церковь руководствуется текущим правилом пересчета (+13). При исторических датировках приоритет должен отдаваться юлианской дате, так как именно на нее ориентировались современники.

Примеры

Русский флотоводец Федор Федорович Ушаков скончался 2 октября 1817 года. В Европе этот день обозначался как (2+12=) 14 октября. Однако Русская Церковь празднует память праведного воина Феодора именно 2 октября, что в современном гражданском календаре соответствует (2+13=) 15 октября.

Бородинская битва произошла 26 августа 1812 года. В этот день Церковь празднует Сретение Владимирской иконы Божией Матери в память чудесного избавления от полчищ Тамерлана. Поэтому, хотя в XIX веке 12 юлианское августа соответствовало 7 сентября (и именно этот день закрепился в советской традиции как дата Бородинской битвы), для православных людей славный подвиг русского воинства был совершен в день Сретения – то есть 8 сентября по н.ст.

Строго говоря, «нового стиля» не существовало до февраля 1918 года (просто в разных странах действовали разные календари). Поэтому и говорить о датах «по новому стилю» можно только применительно к современной практике, когда необходимо пересчитать юлианскую дату на гражданский календарь.

Таким образом, даты событий русской истории до 1918 года следует давать по юлианскому календарю, в скобках указывая соответствующую дату современного гражданского календаря — так, как это делается для всех церковных праздников. Например: 25 декабря 1*** г. (7 января н.ст.).

Если же речь идет о дате международного события, датировавшегося уже современниками по двойной дате, такую дату можно указывать через косую черту. Например: 26 августа / 7 сентября 1812 г. (8 сентября н.ст.).

Приблизительное время чтения: 4 мин.

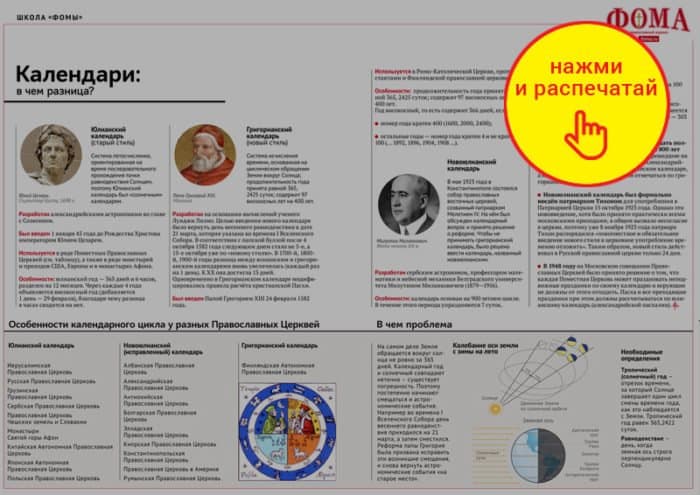

Традиционно в дни рождественских и пасхальных праздников люди задаются вопросом: почему юлианский и григорианский календарь не совпадают, и в чем между ними разница? Мы попытались как можно проще объяснить причину этой, на самом деле, крайне сложной астрономической и математической проблемы.

Юлианский календарь (старый стиль)

Система летосчисления, ориентированная на время последовательного прохождения точки равноденствия Солнцем, поэтому Юлианский календарь был «солнечным» календарем. Юлианский год — 365 дней и 6 часов, разделен на 12 месяцев. Через каждые 4 года объявляется високосный год (добавляется один день — 29 февраля), благодаря чему разница в часах сводится на нет.

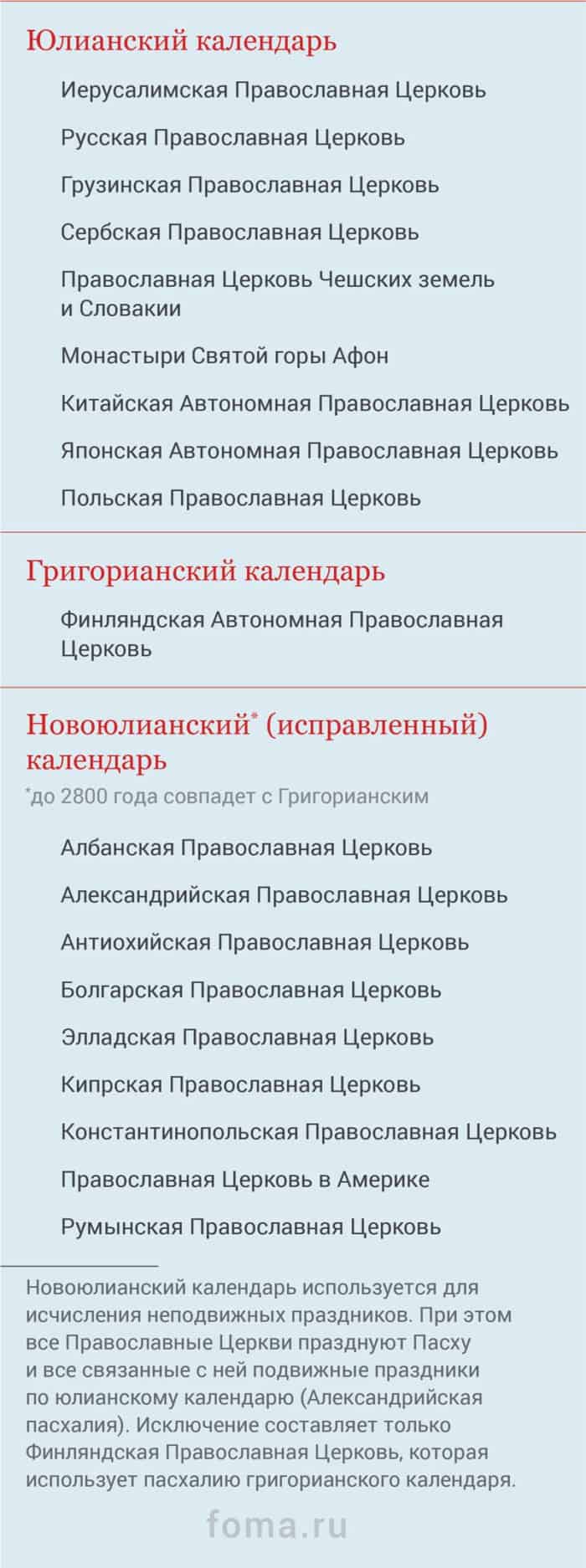

Используется в ряде Поместных Православных Церквей (Иерусалимская, Русская, Сербская, Грузинская, Польская), а также в ряде монастырей и приходов США, Европы и в монастырях Афона.

Разработан александрийскими астрономами во главе с Созигеном. Был введен 1 января 45 года до Рождества Христова императором Юлием Цезарем.

Григорианский календарь (новый стиль)

Система исчисления времени, основанная на циклическом обращении Земли вокруг Солнца; продолжительность года принята равной 365, 2425 суток; содержит 97 високосных лет на 400 лет. Год високосный, то есть содержит 366 дней, если:

- номер года кратен 400 (1600, 2000, 2400);

- остальные годы — номер года кратен 4 и не кратен 100 (… 1892, 1896, 1904, 1908…).

Используется в Римо-Католической Церкви, протестантами и Финляндской православной церковью. Утвержден Папой Григорием XIII 24 февраля 1582 года на основании вычислений ученого Луиджи Лилио. Целью введения нового календаря было вернуть день весеннего равноденствия к дате 21 марта, которая указана во времена I Вселенского Собора. В соответствии с папской буллой после 4 октября 1582 года следующим днем стало не 5-е, а 15-е октября уже по «новому стилю». В 1700-й, 1800-й, 1900-й годы разница между юлианским и григорианским календарями вновь увеличилась (каждый раз на 1 день). К XX она достигла 13 дней.

Одновременно в Григорианском календаре модифицировались правила расчёта христианской Пасхи.

В чем проблема?

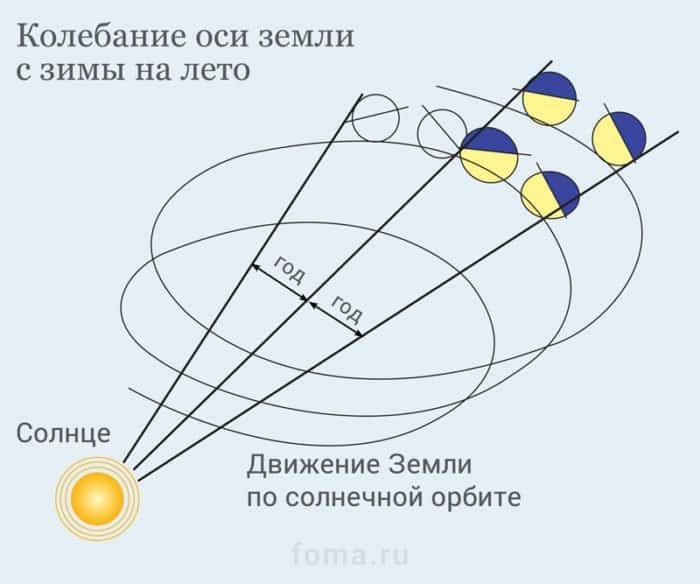

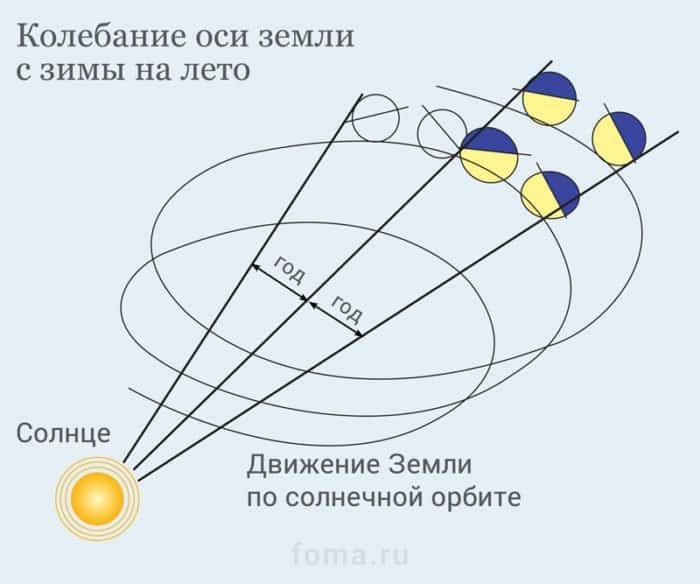

На самом деле Земля обращается вокруг солнца не ровно за 365 дней. Календарный год и солнечный совпадают неточно — существует погрешность. Поэтому постепенно начинают смещаться и астрономические события. Например, во времена I Вселенского Собора день весеннего равноденствия приходился на 21 марта, а затем сместился. Реформа папы Григория была призвана исправить эти возникшие смещения и снова вернуть астрономические события «на старое место».

Необходимые определения

Тропический (солнечный) год — отрезок времени, за который Солнце завершает один цикл смены времени года, как это наблюдается с Земли. Тропический год равен 365,2422 суток.

Равноденствие — день, когда земная ось строго перпендикулярно Солнцу.

Последствия реформы календаря

Принятие григорианского календаря серьезно затянулось, особенно в протестантских странах. В целом протестантские страны переходили на новый календарь постепенно. Последней из них григорианский календарь приняла Англия — в 1752 году.

В России неоднократно обсуждалась тема перехода Церкви на григорианский стиль. Допускался переход при условии, что значительная часть западных христиан перейдет в Православие. Но в целом это считалось нецелесообразным. Последние крупные дебаты относительно перехода на новый стиль проходили в 90-е годы XIX века. Большинство выступало за переход. Однако известный церковный историк Василий Васильевич Болотов был с этим не согласен и приводил два основных аргумента:

а) простота юлианского календаря по сравнению с григорианским. В действительности, крупные астрономы пользовались для своих расчетов именно юлианским календарем вплоть до XX века;

б) возможность перехода не следует из решений I Вселенского Собора (на нем была утверждена Александрийская пасхалия — система вычисления даты Пасхи, которая «работает», то есть обеспечивает точность, только с юлианским годом).

Новоюлианский календарь

В мае 1923 года в Константинополе состоялся собор православных восточных церквей, созванный патриархом Мелетием IV. На нём был обсужден календарный вопрос и принято решение о реформе. Чтобы не принимать григорианский календарь, было решено ввести календарь, названный новоюлианским. Этот календарь был разработан сербским астрономом, профессором математики и небесной механики Белградского университета Милутином Миланковичем (1879–1956).

Этот календарь основан на 900 летнем цикле. В течение этого периода упраздняются 7 суток.

Год считается високосным, если:

- его номер без остатка делится на 4 и не делится на 100 или

- его номер делится на 900 с остатком 200 или 600.

Всего на 900 лет приходится 682 простых и 218 високосных годов (в юлианском 400-летнем цикле имеется 300 простых и 100 високосных, в григорианском — 303 простых и 97 високосных годов).

Новоюлианский календарь будет совпадать полностью с григорианским в последующие 800 лет (до 2800 года). Православные Церкви, перешедшие на новоюлианский календарь, сохранили Александрийскую пасхалию, основанную на юлианском календаре, а непереходящие праздники стали отмечаться по григорианским датам.

Новоюлианский календарь был формально введён патриархом Тихоном для употребления в Патриаршей Церкви 15 октября 1923 года. Однако это нововведение, хотя было принято практически всеми московскими приходами, в общем вызвало несогласие в церкви, поэтому уже 8 ноября 1923 года патриарх Тихон распорядился «повсеместное и обязательное введение нового стиля в церковное употребление временно отложить». Таким образом, новый стиль действовал в Русской православной церкви только 24 дня.

В 1948 году на Московском совещании Православных Церквей было принято решение о том, что каждая Поместная Церковь может праздновать неподвижные праздники по своему календарю и верующие не должны от этого отходить. Пасха и все преходящие праздники при этом должны рассчитываться по юлианскому календарь (александрийской пасхалии).

Читайте также:

Об указе Петра I: как в России начали «толкаться» Новый год и Рождество

Как вычислили дачу Рождества? История одного Дня рождения

Откуда на Руси пошла традиция праздновать Новый год, и можно ли праздновать его верующим людям?

This article is about the 18th-century changes in calendar conventions used by Great Britain and its colonies, together with a brief explanation of usage of the term in other contexts. For a more general discussion of the equivalent transitions in other countries, see Adoption of the Gregorian calendar.

Issue 9198 of The London Gazette, covering the calendar change in Great Britain. The issue spans the changeover: the date heading reads: «From Tuesday September 1, O.S. to Saturday September 16, N.S. 1752».[1]

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 1582 and 1923.

In England, Wales, Ireland and Britain’s American colonies, there were two calendar changes, both in 1752. The first adjusted the start of a new year from Lady Day (25 March) to 1 January (which Scotland had done from 1600), while the second discarded the Julian calendar in favour of the Gregorian calendar, removing 11 days from the September 1752 calendar to do so.[2][3] To accommodate the two calendar changes, writers used dual dating to identify a given day by giving its date according to both styles of dating.

For countries such as Russia where no start of year adjustment took place, O.S. and N.S. simply indicate the Julian and Gregorian dating systems.

Britain and its colonies or possessions[edit]

In the Kingdom of Great Britain and its possessions, the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 introduced two concurrent changes to the calendar. The first, which applied to England, Wales, Ireland and the British colonies, changed the start of the year from 25 March to 1 January with effect from «the day after 31 December 1751».[4][a] (Scotland had already made this aspect of the changes, on 1 January 1600.)[5][6] The second (in effect[b]) adopted the Gregorian calendar in place of the Julian calendar. Thus «New Style» can either refer to the start of year adjustment, or to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, or to the combination of the two.

Start of year adjustment[edit]

When recording British history, it is usual to quote the date as originally recorded at the time of the event, but with the year number adjusted to start on 1 January.[7] The latter adjustment may be needed because the start of the civil calendar year was not always 1 January and was altered at different times in different countries.[c] From 1155 to 1752, the civil or legal year in England began on 25 March (Lady Day);[8][9] so for example, the execution of Charles I was recorded at the time in Parliament as happening on 30 January 1648 (Old Style).[10] In newer English language texts this date is usually shown as «30 January 1649» (New Style).[11] The corresponding date in the Gregorian calendar is 9 February 1649, the date by which his contemporaries in some parts of continental Europe would have recorded his execution.

The O.S./N.S. designation is particularly relevant for dates which fall between the start of the «historical year» (1 January) and the legal start date, where different. This was 25 March in England, Wales, Ireland and the colonies until 1752 and until 1600 in Scotland.

In Britain, 1 January was celebrated as the New Year festival from as early as the 13th century, despite the recorded (civil) year not incrementing until 25 March,[12][d] but the «year starting 25th March was called the Civil or Legal Year, although the phrase Old Style was more commonly used».[3] To reduce misunderstandings about the date, it was normal even in semi-official documents such as parish registers to place a statutory new year heading after 24 March (for example «1661») and another heading from the end of the following December, 1661/62, a form of dual dating to indicate that in the following twelve weeks or so, the year was 1661 Old Style but 1662 New Style.[15] Some more modern sources, often more academic ones (e.g. the History of Parliament) also use the 1661/62 style for the period between 1 January and 24 March for years before the introduction of the New Style calendar in England.[16]

Adoption of the Gregorian calendar[edit]

Through the enactment of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Kingdom of Ireland and the British Empire (including much of what is now the eastern part of the United States and Canada) adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, by which time it was necessary to correct by 11 days. Wednesday, 2 September 1752, was followed by Thursday, 14 September 1752. Claims that rioters demanded «Give us our eleven days» grew out of a misinterpretation of a painting by William Hogarth.[2]

Other countries[edit]

Beginning in October of 1582, the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian in Catholic countries. This change was implemented subsequently in Protestant and Eastern Orthodox countries, usually at much later dates and, in the latter case, only as the civil calendar. Consequently, when Old Style and New Style notation is encountered, the British adoption date is not necessarily intended. The ‘start of year’ change and the calendar system change were not always adopted concurrently. Similarly, civil and religious adoption may not have happened at the same time or even at all. In the case of Eastern Europe, for example, all of those assumptions would be incorrect.

Greece[edit]

Other countries in Eastern Orthodoxy eventually adopted Gregorian (or new style) dating for their civil calendars but most of these continue to use the Julian calendar for religious purposes. Greece was the last to do so, in 1923.[17] There is a 13-day difference between Old Style and New Style dates in modern Greek history.

Romania[edit]

Romania officially adopted the Gregorian calendar on 1 April 1919, which became 14 April 1919. This was commemorated in 2019 by the National Bank of Romania through the release of a commemorative coin of 10 silver lei.[18]

Russia[edit]

In Russia, new style dates came into use in early 1918, when 31 January 1918 was followed by 14 February 1918: there is a 13-day difference between Old Style and New Style dates since 1 March 1900.[19]

It is common in English-language publications to use the familiar Old Style and/or New Style terms to discuss events and personalities in other countries, especially with reference to the Russian Empire and the very beginning of Soviet Russia. For example, in the article «The October (November) Revolution,» the Encyclopædia Britannica uses the format of «25 October (7 November, New Style)» to describe the date of the start of the revolution.[20]

The Americas[edit]

The European colonies of the Americas adopted the new style calendar when their mother countries did. In what is now the continental United States, the French and Spanish possessions did so about 130 years earlier than the British colonies. In practice, however, most surviving written records of what is now Canada and the United States are from the 20 mainland British colonies, where the British Calendar Act of 1751 was applied twenty-four years before the United States declared independence. Canadian records also include documents of New France that reflect the New Style, as France adopted it in 1582, but the language used in the record is likely to be a good indicator of which calendar was being used for the dates given. The same logic applies to the Caribbean islands.

In Alaska, the change took place after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. Friday, 6 October 1867 was followed by Friday, 18 October. Instead of 12 days, only 11 were skipped, and the day of the week was repeated on successive days, because at the same time the International Date Line was moved, from following Alaska’s eastern border with Yukon to following its new western border, now with Russia.[21]

Transposition of historical event dates and possible date conflicts[edit]

Usually, the mapping of New Style dates onto Old Style dates with a start of year adjustment works well with little confusion for events before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar. For example, the Battle of Agincourt is well known to have been fought on 25 October 1415, which is Saint Crispin’s Day. However, for the period between the first introduction of the Gregorian calendar on 15 October 1582 and its introduction in Britain on 14 September 1752, there can be considerable confusion between events in Continental Western Europe and in British domains. Events in Continental Western Europe are usually reported in English-language histories by using the Gregorian calendar. For example, the Battle of Blenheim is always given as 13 August 1704. However, confusion occurs when an event involves both. For example, William III of England arrived at Brixham in England on 5 November (Julian calendar), after he had set sail from the Netherlands on 11 November (Gregorian calendar) 1688.[22]

The Battle of the Boyne in Ireland took place a few months later on 1 July 1690 (Julian calendar). That maps to 11 July (Gregorian calendar), conveniently close to the Julian date of the subsequent (and more decisive) Battle of Aughrim on 12 July 1691 (Julian). The latter battle was commemorated annually throughout the 18th century on 12 July,[23] following the usual historical convention of commemorating events of that period within Great Britain and Ireland by mapping the Julian date directly onto the modern Gregorian calendar date (as happens, for example, with Guy Fawkes Night on 5 November). The Battle of the Boyne was commemorated with smaller parades on 1 July. However, both events were combined in the late 18th century,[23] and continue to be celebrated as «The Twelfth».

Because of the differences, British writers and their correspondents often employed two dates, which is called dual dating, more or less automatically. Letters concerning diplomacy and international trade thus sometimes bore both Julian and Gregorian dates to prevent confusion. For example, Sir William Boswell wrote to Sir John Coke from The Hague a letter dated «12/22 Dec. 1635».[22] In his biography of John Dee, The Queen’s Conjurer, Benjamin Woolley surmises that because Dee fought unsuccessfully for England to embrace the 1583/84 date set for the change, «England remained outside the Gregorian system for a further 170 years, communications during that period customarily carrying two dates».[24] In contrast, Thomas Jefferson, who lived while the British Isles and colonies eventually converted to the Gregorian calendar, instructed that his tombstone bear his date of birth by using the Julian calendar (notated O.S. for Old Style) and his date of death by using the Gregorian calendar.[25] At Jefferson’s birth, the difference was eleven days between the Julian and Gregorian calendars and so his birthday of 2 April in the Julian calendar is 13 April in the Gregorian calendar. Similarly, George Washington is now officially reported as having been born on 22 February 1732, rather than on 11 February 1731/32 (Julian calendar).[26]

There is some evidence that the calendar change was not easily accepted. Many British people continued to celebrate their holidays «Old Style» well into the 19th century,[e] a practice that the author Karen Bellenir considered to reveal a deep emotional resistance to calendar reform.[27]

Differences between Julian and Gregorian dates[edit]

The change arose from the realisation that the correct figure for the number of days in a year is not 365.25 (365 days 6 hours) as assumed by the Julian calendar but slightly less (c. 365.242 days): the Julian calendar has too many leap years. The consequence was that the basis for the calculation of the date of Easter, as decided in the 4th century, had drifted from reality. The Gregorian calendar reform also dealt with the accumulated difference between these figures, between the years 325 and 1582 by skipping 10 days to set the ecclesiastical date of the equinox to be 21 March, the median date of its occurrence at the time of the First Council of Nicea in 325.

Countries that adopted the Gregorian calendar after 1699 needed to skip the additional day for each subsequent new century that the Julian calendar had added since then. When the British Empire did so in 1752, the gap had grown to eleven days;[f] when Russia did so (as its civil calendar) in 1918, thirteen days needed to be skipped.

Other notations[edit]

The Latin equivalents, which are used in many languages, are stili veteris (genitive) or stilo vetere (ablative), abbreviated st.v. and respectively meaning «(of) old style» and «(in) old style», and stili novi or stilo novo, abbreviated st.n. and meaning «(of/in) new style».[28] The Latin abbreviations may be capitalised differently by different users, e.g., St.n. or St.N. for stili novi.[28] There are equivalents for these terms in other languages as well, such as the German a.St. («alten Stils» for O.S.).

See also[edit]

- Dual dating

- Difference between Gregorian and Julian calendar dates (ready-reckoner)

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Act has to use this formulation since «1 January 1752» was still ambiguous.

- ^ The Calendar Act does not mention Pope Gregory

- ^ British official legal documents of the 16th and 17th centuries were usually dated by the regnal year of the monarch. As these commence on the day and date of the monarch’s accession, they normally span two consecutive calendar years and have to be calculated accordingly, but the resultant dates should be unambiguous.

- ^ For example, see the Diary of Samuel Pepys for 31 December 1661: «I sat down to end my journell for this year, …»,[13] which is immediately followed by an entry dated «1 January 1661/62″.[14] This is an example of the dual dating system which had become common at the time.

- ^ See also Little Christmas.

- ^ Because 1600 was a leap year in both calendars, only one extra leap day (in 1700) needed to be added to the reckoning

References[edit]

- ^ «The London Gazette |From Tuesday September 1 O.S. to Saturday September 16 N.S. 1752». London Gazette (9198): 1. 1 September 1752.

- ^ a b Poole 1995, pp. 95–139.

- ^ a b Spathaky, Mike Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian Calendar. «Before 1752, parish registers, in addition to a new year heading after 24th March showing, for example ‘1733’, had another heading at the end of the following December indicating ‘1733/4’. This showed where the Historical Year 1734 started even though the Civil Year 1733 continued until 24th March. … We as historians have no excuse for creating ambiguity and must keep to the notation described above in one of its forms. It is no good writing simply 20th January 1745, for a reader is left wondering whether we have used the Civil or the Historical Year. The date should either be written 20th January 1745 OS (if indeed it was Old Style) or as 20th January 1745/6. The hyphen (1745-6) is best avoided as it can be interpreted as indicating a period of time.»

- ^ Bond 1875, page 91.

- ^ Steele 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Bond 1875, xvii–xviii: original text of the Scottish decree.

- ^ e.g. Woolf, Daniel (2003). The Social Circulation of the Past: English Historical Culture 1500–1730. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xiii. ISBN 0-19-925778-7.

Dates are Old Style, but the year is calculated from 1 January. On occasion, where clarity requires it, dates are written 1687/8.

- ^ Nørby, Toke. The Perpetual Calendar: What about England? Version 29 February 2000.

- ^ Gerard 1908.

- ^ «House of Commons Journal Volume 8, 9 June 1660 (Regicides)». British History Online. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ Death warrant of Charles I web page of the UK National Archives. A demonstration of New Style, meaning Julian calendar with a start of year adjustment.

- ^ Pollard, A. F. (1940). «New Year’s Day and Leap Year in English History». The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 55 (218): 180–185. doi:10.1093/ehr/lv.ccxviii.177. JSTOR 553864. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel. «Tuesday 31 December 1661». www.pepysdiary.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel. «Wednesday 1 January 1661/62». www.pepysdiary.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Spathaky, Mike Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian Calendar. «An oblique stroke is by far the most usual indicator, but sometimes the alternative final figures of the year are written above and below a horizontal line, as in a fraction, thus:

. Very occasionally a hyphen is used, as 1733-34.»

- ^ See for example this biographical entry: Lancaster, Henry (2010). «Chocke, Alexander II (1593/4–1625), of Shalbourne, Wilts.; later of Hungerford Park, Berks». In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (eds.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Blegen, Carl W. (25 December 2013) [n.d.]. Vogeikoff-Brogan, Natalia (ed.). «An Odd Christmas». From the Archivist’s Notebook. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Alexander, Michael (3 April 2019). «Romania: Centenary anniversary of adopting the Gregorian calendar depicted on new silver coins». Coin Update.

- ^ S. I. Seleschnikow: Wieviel Monde hat ein Jahr? (Aulis-Verlag, Leipzig/Jena/Berlin 1981, p. 149), which is a German translation of С. И. Селешников: История календаря и хронология (Издательство «Наука», Moscow 1977). The relevant chapter is available online here: История календаря в России и в СССР (Calendar history in Russia and the USSR). (in Russian)

- ^ EB online 2017.

- ^ Dershowitz, Nachum; Reingold, Edward M. (2008). Calendrical Calculations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780521885409.

- ^ a b Cheney & Jones 2000, p. 19.

- ^ a b Lenihan, Pádraig (2003). 1690 Battle of the Boyne. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0-7524-2597-8.

- ^ Baker, John. «Why Bacon, Oxford and Other’s Weren’t Shakespeare». Archived from the original on 4 April 2005.) uses the quote by Benjamin Woolley and cites The Queen’s Conjurer, The Science and Magic of Dr. John Dee, Adviser to Queen Elizabeth I, page 173.

- ^ «Old Style (O.S.)». monticello.org. June 1995. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (18 January 2006). «What’s Benjamin Franklin’s Birthday?». Slate. Retrieved 8 February 2013. (Both Franklin’s and Washington’s confusing birth dates are clearly explained.)

- ^ Bellenir, Karen (2004). Religious Holidays and Calendars. Detroit: Omnigraphics. p. 33.

- ^ a b Lenz, Rudolf; Uwe Bredehorn; Marek Winiarczyk (2002). Abkürzungen aus Personalschriften des XVI. bis XVIII. Jahrhunderts (3 ed.). Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 210. ISBN 3-515-08152-6.

Sources[edit]

- Bond, John James (1875). Handy Book of Rules and Tables for Verifying Dates With the Christian Era Giving an Account of the Chief Eras and Systems Used by Various Nations…’. London: George Bell & Sons. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Cheney, C. R.; Jones, Michael, eds. (2000). A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History (PDF). Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks. Vol. 4 (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0-521-77095-8.

- Gerard, John (1908). «General Chronology § Beginning of the year» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Parliament of Ireland (1750). «Calendar (New Style) Act, 1750». Government of Ireland. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Philip, Alexander (1921). The Calendar: its history, structure and improvement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9781107640214.

- Russia: The October (November) Revolution (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Steele, Duncan (2000). Marking Time: the epic quest to invent the perfect calendar. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471404217.

- Poole, Robert (1995). «‘Give us our eleven days!’: calendar reform in eighteenth-century England». Past & Present. Oxford Academic. 149 (1): 95–139. doi:10.1093/past/149.1.95. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Details of conversion for many countries

- Side-by-side Old style–New style reference

- Time to Take Note: The 1752 Calendar Change

- Calendar Converter – Date converter for many systems, from John Walker

- Calendar converter to ancient Attic, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian by Academy of Episteme

This article is about the 18th-century changes in calendar conventions used by Great Britain and its colonies, together with a brief explanation of usage of the term in other contexts. For a more general discussion of the equivalent transitions in other countries, see Adoption of the Gregorian calendar.

Issue 9198 of The London Gazette, covering the calendar change in Great Britain. The issue spans the changeover: the date heading reads: «From Tuesday September 1, O.S. to Saturday September 16, N.S. 1752».[1]

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 1582 and 1923.

In England, Wales, Ireland and Britain’s American colonies, there were two calendar changes, both in 1752. The first adjusted the start of a new year from Lady Day (25 March) to 1 January (which Scotland had done from 1600), while the second discarded the Julian calendar in favour of the Gregorian calendar, removing 11 days from the September 1752 calendar to do so.[2][3] To accommodate the two calendar changes, writers used dual dating to identify a given day by giving its date according to both styles of dating.

For countries such as Russia where no start of year adjustment took place, O.S. and N.S. simply indicate the Julian and Gregorian dating systems.

Britain and its colonies or possessions[edit]

In the Kingdom of Great Britain and its possessions, the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 introduced two concurrent changes to the calendar. The first, which applied to England, Wales, Ireland and the British colonies, changed the start of the year from 25 March to 1 January with effect from «the day after 31 December 1751».[4][a] (Scotland had already made this aspect of the changes, on 1 January 1600.)[5][6] The second (in effect[b]) adopted the Gregorian calendar in place of the Julian calendar. Thus «New Style» can either refer to the start of year adjustment, or to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, or to the combination of the two.

Start of year adjustment[edit]

When recording British history, it is usual to quote the date as originally recorded at the time of the event, but with the year number adjusted to start on 1 January.[7] The latter adjustment may be needed because the start of the civil calendar year was not always 1 January and was altered at different times in different countries.[c] From 1155 to 1752, the civil or legal year in England began on 25 March (Lady Day);[8][9] so for example, the execution of Charles I was recorded at the time in Parliament as happening on 30 January 1648 (Old Style).[10] In newer English language texts this date is usually shown as «30 January 1649» (New Style).[11] The corresponding date in the Gregorian calendar is 9 February 1649, the date by which his contemporaries in some parts of continental Europe would have recorded his execution.

The O.S./N.S. designation is particularly relevant for dates which fall between the start of the «historical year» (1 January) and the legal start date, where different. This was 25 March in England, Wales, Ireland and the colonies until 1752 and until 1600 in Scotland.

In Britain, 1 January was celebrated as the New Year festival from as early as the 13th century, despite the recorded (civil) year not incrementing until 25 March,[12][d] but the «year starting 25th March was called the Civil or Legal Year, although the phrase Old Style was more commonly used».[3] To reduce misunderstandings about the date, it was normal even in semi-official documents such as parish registers to place a statutory new year heading after 24 March (for example «1661») and another heading from the end of the following December, 1661/62, a form of dual dating to indicate that in the following twelve weeks or so, the year was 1661 Old Style but 1662 New Style.[15] Some more modern sources, often more academic ones (e.g. the History of Parliament) also use the 1661/62 style for the period between 1 January and 24 March for years before the introduction of the New Style calendar in England.[16]

Adoption of the Gregorian calendar[edit]

Through the enactment of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Kingdom of Ireland and the British Empire (including much of what is now the eastern part of the United States and Canada) adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, by which time it was necessary to correct by 11 days. Wednesday, 2 September 1752, was followed by Thursday, 14 September 1752. Claims that rioters demanded «Give us our eleven days» grew out of a misinterpretation of a painting by William Hogarth.[2]

Other countries[edit]

Beginning in October of 1582, the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian in Catholic countries. This change was implemented subsequently in Protestant and Eastern Orthodox countries, usually at much later dates and, in the latter case, only as the civil calendar. Consequently, when Old Style and New Style notation is encountered, the British adoption date is not necessarily intended. The ‘start of year’ change and the calendar system change were not always adopted concurrently. Similarly, civil and religious adoption may not have happened at the same time or even at all. In the case of Eastern Europe, for example, all of those assumptions would be incorrect.

Greece[edit]

Other countries in Eastern Orthodoxy eventually adopted Gregorian (or new style) dating for their civil calendars but most of these continue to use the Julian calendar for religious purposes. Greece was the last to do so, in 1923.[17] There is a 13-day difference between Old Style and New Style dates in modern Greek history.

Romania[edit]

Romania officially adopted the Gregorian calendar on 1 April 1919, which became 14 April 1919. This was commemorated in 2019 by the National Bank of Romania through the release of a commemorative coin of 10 silver lei.[18]

Russia[edit]

In Russia, new style dates came into use in early 1918, when 31 January 1918 was followed by 14 February 1918: there is a 13-day difference between Old Style and New Style dates since 1 March 1900.[19]

It is common in English-language publications to use the familiar Old Style and/or New Style terms to discuss events and personalities in other countries, especially with reference to the Russian Empire and the very beginning of Soviet Russia. For example, in the article «The October (November) Revolution,» the Encyclopædia Britannica uses the format of «25 October (7 November, New Style)» to describe the date of the start of the revolution.[20]

The Americas[edit]

The European colonies of the Americas adopted the new style calendar when their mother countries did. In what is now the continental United States, the French and Spanish possessions did so about 130 years earlier than the British colonies. In practice, however, most surviving written records of what is now Canada and the United States are from the 20 mainland British colonies, where the British Calendar Act of 1751 was applied twenty-four years before the United States declared independence. Canadian records also include documents of New France that reflect the New Style, as France adopted it in 1582, but the language used in the record is likely to be a good indicator of which calendar was being used for the dates given. The same logic applies to the Caribbean islands.

In Alaska, the change took place after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. Friday, 6 October 1867 was followed by Friday, 18 October. Instead of 12 days, only 11 were skipped, and the day of the week was repeated on successive days, because at the same time the International Date Line was moved, from following Alaska’s eastern border with Yukon to following its new western border, now with Russia.[21]

Transposition of historical event dates and possible date conflicts[edit]

Usually, the mapping of New Style dates onto Old Style dates with a start of year adjustment works well with little confusion for events before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar. For example, the Battle of Agincourt is well known to have been fought on 25 October 1415, which is Saint Crispin’s Day. However, for the period between the first introduction of the Gregorian calendar on 15 October 1582 and its introduction in Britain on 14 September 1752, there can be considerable confusion between events in Continental Western Europe and in British domains. Events in Continental Western Europe are usually reported in English-language histories by using the Gregorian calendar. For example, the Battle of Blenheim is always given as 13 August 1704. However, confusion occurs when an event involves both. For example, William III of England arrived at Brixham in England on 5 November (Julian calendar), after he had set sail from the Netherlands on 11 November (Gregorian calendar) 1688.[22]

The Battle of the Boyne in Ireland took place a few months later on 1 July 1690 (Julian calendar). That maps to 11 July (Gregorian calendar), conveniently close to the Julian date of the subsequent (and more decisive) Battle of Aughrim on 12 July 1691 (Julian). The latter battle was commemorated annually throughout the 18th century on 12 July,[23] following the usual historical convention of commemorating events of that period within Great Britain and Ireland by mapping the Julian date directly onto the modern Gregorian calendar date (as happens, for example, with Guy Fawkes Night on 5 November). The Battle of the Boyne was commemorated with smaller parades on 1 July. However, both events were combined in the late 18th century,[23] and continue to be celebrated as «The Twelfth».

Because of the differences, British writers and their correspondents often employed two dates, which is called dual dating, more or less automatically. Letters concerning diplomacy and international trade thus sometimes bore both Julian and Gregorian dates to prevent confusion. For example, Sir William Boswell wrote to Sir John Coke from The Hague a letter dated «12/22 Dec. 1635».[22] In his biography of John Dee, The Queen’s Conjurer, Benjamin Woolley surmises that because Dee fought unsuccessfully for England to embrace the 1583/84 date set for the change, «England remained outside the Gregorian system for a further 170 years, communications during that period customarily carrying two dates».[24] In contrast, Thomas Jefferson, who lived while the British Isles and colonies eventually converted to the Gregorian calendar, instructed that his tombstone bear his date of birth by using the Julian calendar (notated O.S. for Old Style) and his date of death by using the Gregorian calendar.[25] At Jefferson’s birth, the difference was eleven days between the Julian and Gregorian calendars and so his birthday of 2 April in the Julian calendar is 13 April in the Gregorian calendar. Similarly, George Washington is now officially reported as having been born on 22 February 1732, rather than on 11 February 1731/32 (Julian calendar).[26]

There is some evidence that the calendar change was not easily accepted. Many British people continued to celebrate their holidays «Old Style» well into the 19th century,[e] a practice that the author Karen Bellenir considered to reveal a deep emotional resistance to calendar reform.[27]

Differences between Julian and Gregorian dates[edit]

The change arose from the realisation that the correct figure for the number of days in a year is not 365.25 (365 days 6 hours) as assumed by the Julian calendar but slightly less (c. 365.242 days): the Julian calendar has too many leap years. The consequence was that the basis for the calculation of the date of Easter, as decided in the 4th century, had drifted from reality. The Gregorian calendar reform also dealt with the accumulated difference between these figures, between the years 325 and 1582 by skipping 10 days to set the ecclesiastical date of the equinox to be 21 March, the median date of its occurrence at the time of the First Council of Nicea in 325.

Countries that adopted the Gregorian calendar after 1699 needed to skip the additional day for each subsequent new century that the Julian calendar had added since then. When the British Empire did so in 1752, the gap had grown to eleven days;[f] when Russia did so (as its civil calendar) in 1918, thirteen days needed to be skipped.

Other notations[edit]

The Latin equivalents, which are used in many languages, are stili veteris (genitive) or stilo vetere (ablative), abbreviated st.v. and respectively meaning «(of) old style» and «(in) old style», and stili novi or stilo novo, abbreviated st.n. and meaning «(of/in) new style».[28] The Latin abbreviations may be capitalised differently by different users, e.g., St.n. or St.N. for stili novi.[28] There are equivalents for these terms in other languages as well, such as the German a.St. («alten Stils» for O.S.).

See also[edit]

- Dual dating

- Difference between Gregorian and Julian calendar dates (ready-reckoner)

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Act has to use this formulation since «1 January 1752» was still ambiguous.

- ^ The Calendar Act does not mention Pope Gregory

- ^ British official legal documents of the 16th and 17th centuries were usually dated by the regnal year of the monarch. As these commence on the day and date of the monarch’s accession, they normally span two consecutive calendar years and have to be calculated accordingly, but the resultant dates should be unambiguous.

- ^ For example, see the Diary of Samuel Pepys for 31 December 1661: «I sat down to end my journell for this year, …»,[13] which is immediately followed by an entry dated «1 January 1661/62″.[14] This is an example of the dual dating system which had become common at the time.

- ^ See also Little Christmas.

- ^ Because 1600 was a leap year in both calendars, only one extra leap day (in 1700) needed to be added to the reckoning

References[edit]

- ^ «The London Gazette |From Tuesday September 1 O.S. to Saturday September 16 N.S. 1752». London Gazette (9198): 1. 1 September 1752.

- ^ a b Poole 1995, pp. 95–139.

- ^ a b Spathaky, Mike Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian Calendar. «Before 1752, parish registers, in addition to a new year heading after 24th March showing, for example ‘1733’, had another heading at the end of the following December indicating ‘1733/4’. This showed where the Historical Year 1734 started even though the Civil Year 1733 continued until 24th March. … We as historians have no excuse for creating ambiguity and must keep to the notation described above in one of its forms. It is no good writing simply 20th January 1745, for a reader is left wondering whether we have used the Civil or the Historical Year. The date should either be written 20th January 1745 OS (if indeed it was Old Style) or as 20th January 1745/6. The hyphen (1745-6) is best avoided as it can be interpreted as indicating a period of time.»

- ^ Bond 1875, page 91.

- ^ Steele 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Bond 1875, xvii–xviii: original text of the Scottish decree.

- ^ e.g. Woolf, Daniel (2003). The Social Circulation of the Past: English Historical Culture 1500–1730. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xiii. ISBN 0-19-925778-7.

Dates are Old Style, but the year is calculated from 1 January. On occasion, where clarity requires it, dates are written 1687/8.

- ^ Nørby, Toke. The Perpetual Calendar: What about England? Version 29 February 2000.

- ^ Gerard 1908.

- ^ «House of Commons Journal Volume 8, 9 June 1660 (Regicides)». British History Online. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ Death warrant of Charles I web page of the UK National Archives. A demonstration of New Style, meaning Julian calendar with a start of year adjustment.

- ^ Pollard, A. F. (1940). «New Year’s Day and Leap Year in English History». The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 55 (218): 180–185. doi:10.1093/ehr/lv.ccxviii.177. JSTOR 553864. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel. «Tuesday 31 December 1661». www.pepysdiary.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel. «Wednesday 1 January 1661/62». www.pepysdiary.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021.

- ^ Spathaky, Mike Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian Calendar. «An oblique stroke is by far the most usual indicator, but sometimes the alternative final figures of the year are written above and below a horizontal line, as in a fraction, thus:

. Very occasionally a hyphen is used, as 1733-34.»

- ^ See for example this biographical entry: Lancaster, Henry (2010). «Chocke, Alexander II (1593/4–1625), of Shalbourne, Wilts.; later of Hungerford Park, Berks». In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (eds.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Blegen, Carl W. (25 December 2013) [n.d.]. Vogeikoff-Brogan, Natalia (ed.). «An Odd Christmas». From the Archivist’s Notebook. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Alexander, Michael (3 April 2019). «Romania: Centenary anniversary of adopting the Gregorian calendar depicted on new silver coins». Coin Update.

- ^ S. I. Seleschnikow: Wieviel Monde hat ein Jahr? (Aulis-Verlag, Leipzig/Jena/Berlin 1981, p. 149), which is a German translation of С. И. Селешников: История календаря и хронология (Издательство «Наука», Moscow 1977). The relevant chapter is available online here: История календаря в России и в СССР (Calendar history in Russia and the USSR). (in Russian)

- ^ EB online 2017.

- ^ Dershowitz, Nachum; Reingold, Edward M. (2008). Calendrical Calculations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780521885409.

- ^ a b Cheney & Jones 2000, p. 19.

- ^ a b Lenihan, Pádraig (2003). 1690 Battle of the Boyne. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0-7524-2597-8.

- ^ Baker, John. «Why Bacon, Oxford and Other’s Weren’t Shakespeare». Archived from the original on 4 April 2005.) uses the quote by Benjamin Woolley and cites The Queen’s Conjurer, The Science and Magic of Dr. John Dee, Adviser to Queen Elizabeth I, page 173.

- ^ «Old Style (O.S.)». monticello.org. June 1995. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (18 January 2006). «What’s Benjamin Franklin’s Birthday?». Slate. Retrieved 8 February 2013. (Both Franklin’s and Washington’s confusing birth dates are clearly explained.)

- ^ Bellenir, Karen (2004). Religious Holidays and Calendars. Detroit: Omnigraphics. p. 33.

- ^ a b Lenz, Rudolf; Uwe Bredehorn; Marek Winiarczyk (2002). Abkürzungen aus Personalschriften des XVI. bis XVIII. Jahrhunderts (3 ed.). Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 210. ISBN 3-515-08152-6.

Sources[edit]

- Bond, John James (1875). Handy Book of Rules and Tables for Verifying Dates With the Christian Era Giving an Account of the Chief Eras and Systems Used by Various Nations…’. London: George Bell & Sons. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Cheney, C. R.; Jones, Michael, eds. (2000). A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History (PDF). Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks. Vol. 4 (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0-521-77095-8.

- Gerard, John (1908). «General Chronology § Beginning of the year» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Parliament of Ireland (1750). «Calendar (New Style) Act, 1750». Government of Ireland. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Philip, Alexander (1921). The Calendar: its history, structure and improvement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9781107640214.

- Russia: The October (November) Revolution (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Steele, Duncan (2000). Marking Time: the epic quest to invent the perfect calendar. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471404217.

- Poole, Robert (1995). «‘Give us our eleven days!’: calendar reform in eighteenth-century England». Past & Present. Oxford Academic. 149 (1): 95–139. doi:10.1093/past/149.1.95. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Details of conversion for many countries

- Side-by-side Old style–New style reference

- Time to Take Note: The 1752 Calendar Change

- Calendar Converter – Date converter for many systems, from John Walker

- Calendar converter to ancient Attic, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian by Academy of Episteme

|

|

Конвертер датКонвертер дат григорианского и юлианского календарей онлайнКонвертер переводит даты в григорианский и юлианский календари и вычисляет юлианскую дату; Григорианский календарьЮлианский календарьЛатинская версияРимская версияЮлианская дата (дни)Примечания

Первые числа месяца определяют, отсчитывая дни от предстоящих Нон, по прошествии Нон — от Ид, после Ид — от предстоящих Календ. При этом используется предлог ante ‘до’ c винительным падежом (accusatīvus): 22 августа 80 г. н. э. = за 11 дней до сентябрьских Календ: a. d. XI Kal. Sept. (сокращенная форма); ante diem undecĭmum Kalendas Septembres (полная форма). Порядковое числительное согласуется с формой diem, то есть ставится в винительный падеж единственного числа мужского рода (accusatīvus singulāris masculīnum). Таким образом, числительные принимают следующие формы:

Если день попадает на Календы, Ноны или Иды, то название этого дня (Kalendae, Nonae, Idūs) и название месяца ставится в творительный падеж множественного числа женского рода (ablatīvus plurālis feminīnum), например: 1-го февраля — Kalendis Februariis; 15-го марта — Idĭbus Martiis; 5-го апреля — Nonis Aprilĭbus. День, непосредственно предшествующий Календам, Нонам или Идам, обозначается словом pridie (‘накануне’) с винительным падежом множественного числа женского рода (accusatīvus plurālis feminīnum): 31-го января — pridie Kalendas Februarias; 14-го марта — pridie Idūs Martias; 4-го апреля — pridie Nonas Aprīles. Таким образом, прилагательные-названия месяцев могут принимать следующие формы:

|

Традиционно в дни рождественских и пасхальных праздников люди задаются вопросом: почему юлианский и григорианский календарь не совпадают, и в чем между ними разница? Мы попытались как можно проще объяснить причину этой, на самом деле, крайне сложной астрономической и математической проблемы.

Юлианский календарь (старый стиль)

Система летосчисления, ориентированная на время последовательного прохождения точки равноденствия Солнцем, поэтому Юлианский календарь был «солнечным» календарем. Юлианский год — 365 дней и 6 часов, разделен на 12 месяцев. Через каждые 4 года объявляется високосный год (добавляется один день — 29 февраля), благодаря чему разница в часах сводится на нет.

Используется в ряде Поместных Православных Церквей (Иерусалимская, Русская, Сербская, Грузинская, Польская), а также в ряде монастырей и приходов США, Европы и в монастырях Афона.

Разработан александрийскими астрономами во главе с Созигеном. Был введен 1 января 45 года до Рождества Христова императором Юлием Цезарем.

Григорианский календарь (новый стиль)

Система исчисления времени, основанная на циклическом обращении Земли вокруг Солнца; продолжительность года принята равной 365, 2425 суток; содержит 97 високосных лет на 400 лет. Год високосный, то есть содержит 366 дней, если:

- номер года кратен 400 (1600, 2000, 2400);

- остальные годы — номер года кратен 4 и не кратен 100 (… 1892, 1896, 1904, 1908…).

Используется в Римо-Католической Церкви, протестантами и Финляндской православной церковью. Утвержден Папой Григорием XIII 24 февраля 1582 года на основании вычислений ученого Луиджи Лилио. Целью введения нового календаря было вернуть день весеннего равноденствия к дате 21 марта, которая указана во времена I Вселенского Собора. В соответствии с папской буллой после 4 октября 1582 года следующим днем стало не 5-е, а 15-е октября уже по «новому стилю». В 1700-й, 1800-й, 1900-й годы разница между юлианским и григорианским календарями вновь увеличилась (каждый раз на 1 день). К XX она достигла 13 дней.

Одновременно в Григорианском календаре модифицировались правила расчёта христианской Пасхи.

В чем проблема?

На самом деле Земля обращается вокруг солнца не ровно за 365 дней. Календарный год и солнечный совпадают неточно — существует погрешность. Поэтому постепенно начинают смещаться и астрономические события. Например, во времена I Вселенского Собора день весеннего равноденствия приходился на 21 марта, а затем сместился. Реформа папы Григория была призвана исправить эти возникшие смещения и снова вернуть астрономические события «на старое место».

Последствия реформы календаря

Принятие григорианского календаря серьезно затянулось, особенно в протестантских странах. В целом протестантские страны переходили на новый календарь постепенно. Последней из них григорианский календарь приняла Англия — в 1752 году.

В России неоднократно обсуждалась тема перехода Церкви на григорианский стиль. Допускался переход при условии, что значительная часть западных христиан перейдет в Православие. Но в целом это считалось нецелесообразным. Последние крупные дебаты относительно перехода на новый стиль проходили в 90-е годы XIX века. Большинство выступало за переход. Однако известный церковный историк Василий Васильевич Болотов был с этим не согласен и приводил два основных аргумента:

а) простота юлианского календаря по сравнению с григорианским. В действительности, крупные астрономы пользовались для своих расчетов именно юлианским календарем вплоть до XX века;

б) возможность перехода не следует из решений I Вселенского Собора (на нем была утверждена Александрийская пасхалия — система вычисления даты Пасхи, которая «работает», то есть обеспечивает точность, только с юлианским годом).

Новоюлианский календарь

В мае 1923 года в Константинополе состоялся собор православных восточных церквей, созванный патриархом Мелетием IV. На нём был обсужден календарный вопрос и принято решение о реформе. Чтобы не принимать григорианский календарь, было решено ввести календарь, названный новоюлианским. Этот календарь был разработан сербским астрономом, профессором математики и небесной механики Белградского университета Милутином Миланковичем (1879–1956).

Этот календарь основан на 900 летнем цикле. В течение этого периода упраздняются 7 суток.

Год считается високосным, если:

- его номер без остатка делится на 4 и не делится на 100 или

- его номер делится на 900 с остатком 200 или 600.

Всего на 900 лет приходится 682 простых и 218 високосных годов (в юлианском 400-летнем цикле имеется 300 простых и 100 високосных, в григорианском — 303 простых и 97 високосных годов).

Новоюлианский календарь будет совпадать полностью с григорианским в последующие 800 лет (до 2800 года). Православные Церкви, перешедшие на новоюлианский календарь, сохранили Александрийскую пасхалию, основанную на юлианском календаре, а непереходящие праздники стали отмечаться по григорианским датам.

Новоюлианский календарь был формально введён патриархом Тихоном для употребления в Патриаршей Церкви 15 октября 1923 года. Однако это нововведение, хотя было принято практически всеми московскими приходами, в общем вызвало несогласие в церкви, поэтому уже 8 ноября 1923 года патриарх Тихон распорядился «повсеместное и обязательное введение нового стиля в церковное употребление временно отложить». Таким образом, новый стиль действовал в Русской православной церкви только 24 дня.

В 1948 году на Московском совещании Православных Церквей было принято решение о том, что каждая Поместная Церковь может праздновать неподвижные праздники по своему календарю и верующие не должны от этого отходить. Пасха и все преходящие праздники при этом должны рассчитываться по юлианскому календарь (александрийской пасхалии).

Фома