Интервалы в музыке — мера определения соотношения между двумя звуками разной высоты. Несмотря на то, что интервалы можно представить в виде математической (соотношение двух чисел) или акустической (центы) величины, музыкальная теория пошла простым путем, рассчитав музыкальные интервалы на основе звукоряда, в котором главная роль отведена количеству тонов и полутонов между двумя нотами.

Каждый интервал характеризуется собственным звучанием: одни звуки, извлеченные одновременно, в интервале звучат приятно и легко (см. приму, квинту или октаву), в то время как другие — режут слух (см. малую или большую секунду); одни интервалы отличаются «веселым» характером звучания, вторые — грустным.

Интервал всегда состоит из двух звуков, при этом нижний звук называют основанием интервала, а верхний звук — вершиной интервала.

Интервалы в музыке

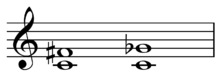

- Прима

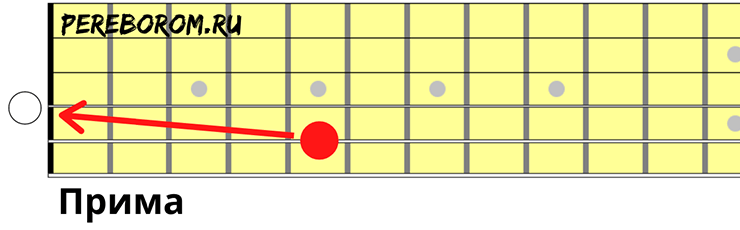

- Малая секунда

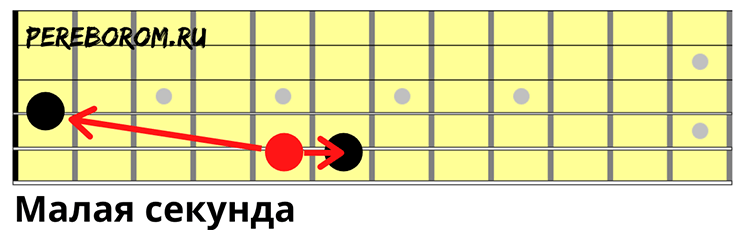

- Большая секунда

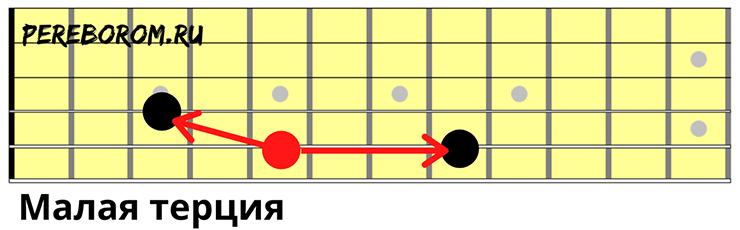

- Малая терция

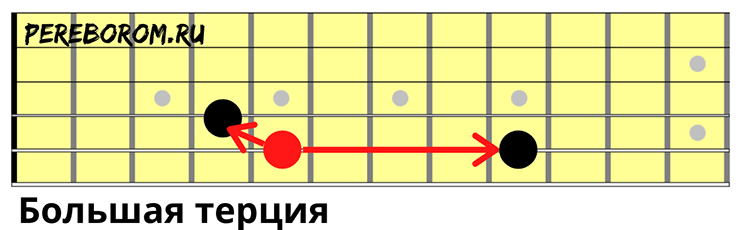

- Большая терция

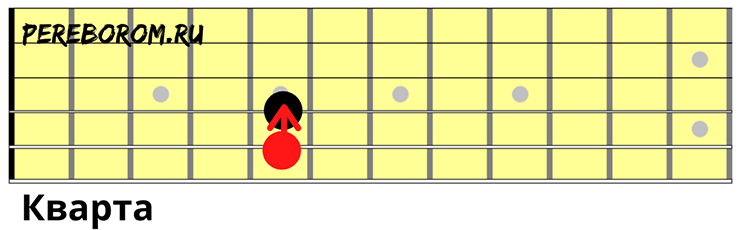

- Чистая кварта

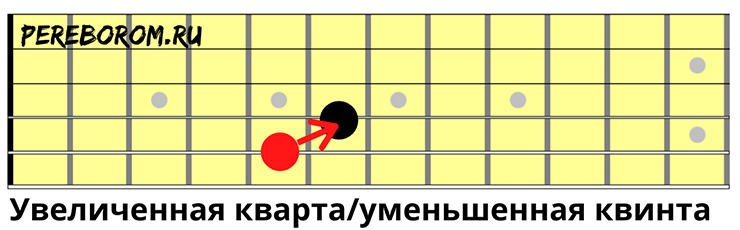

- Увеличенная кварта или уменьшенная квинта

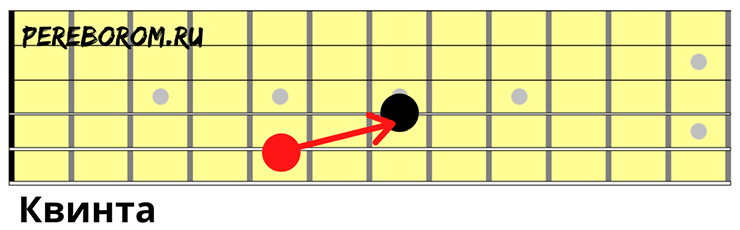

- Чистая квинта

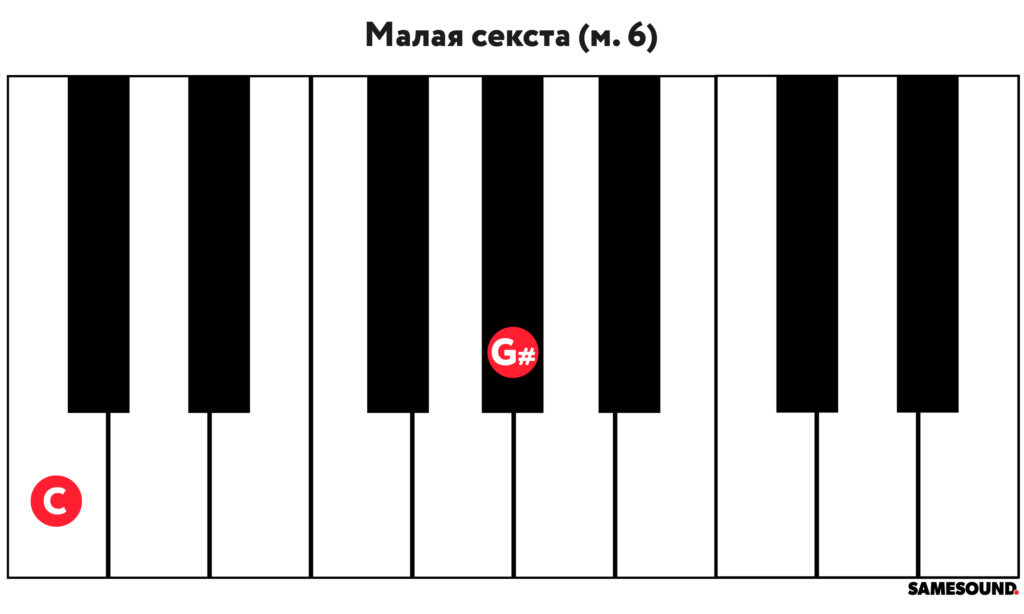

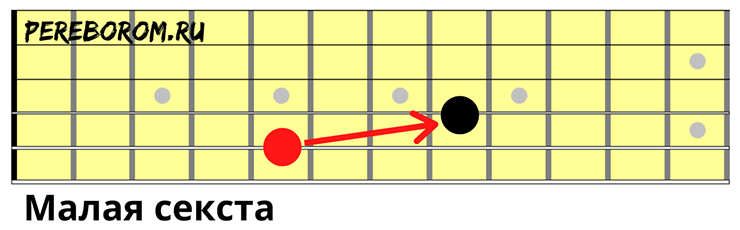

- Малая секста

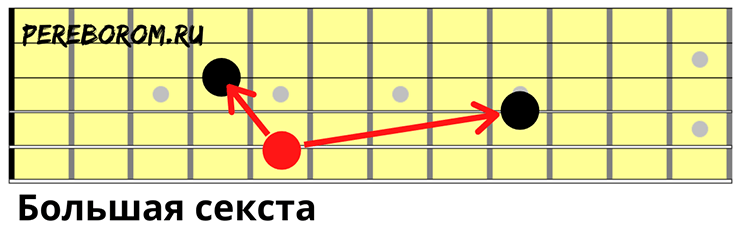

- Большая секста

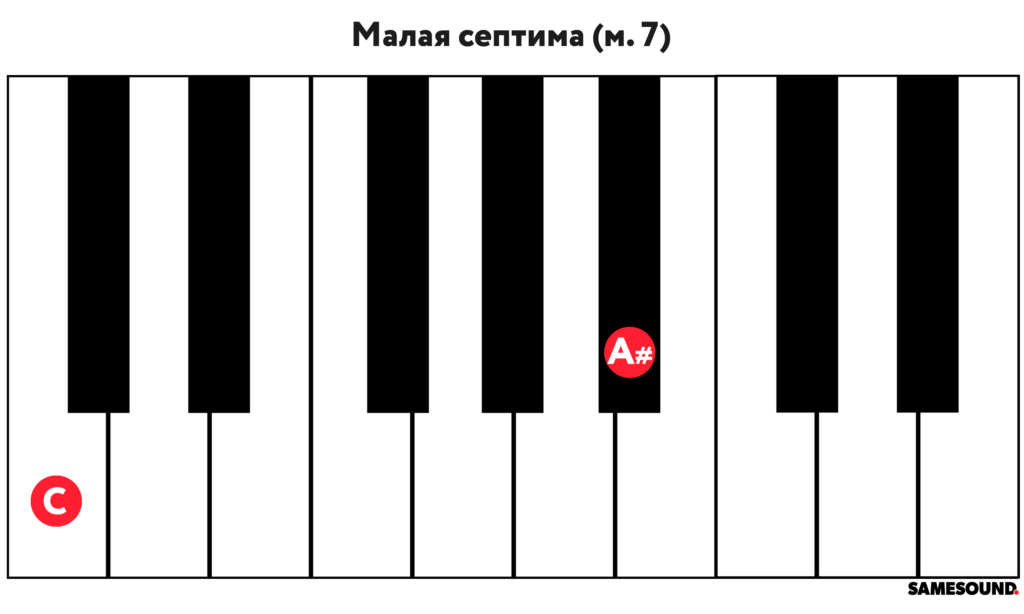

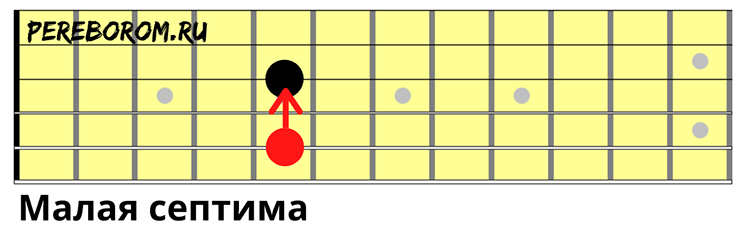

- Малая септима

- Большая септима

- Чистая октава

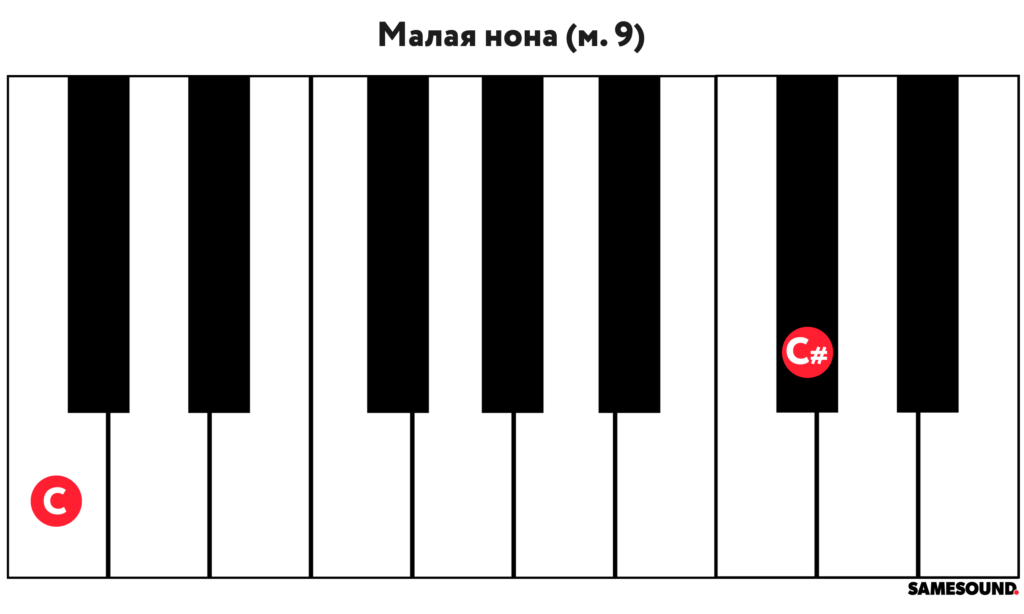

- Малая нона

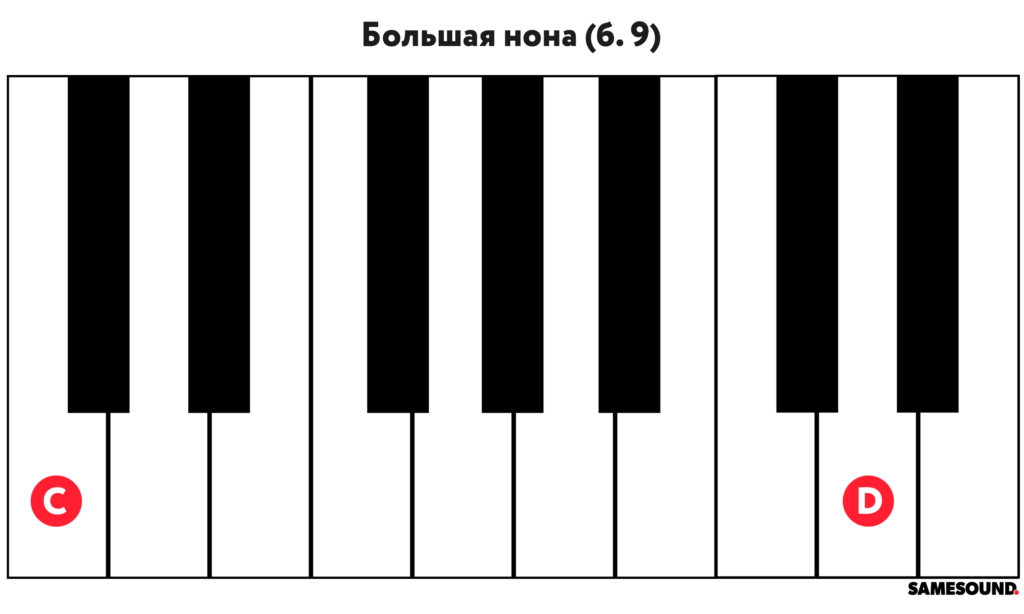

- Большая нона

- Малая децима

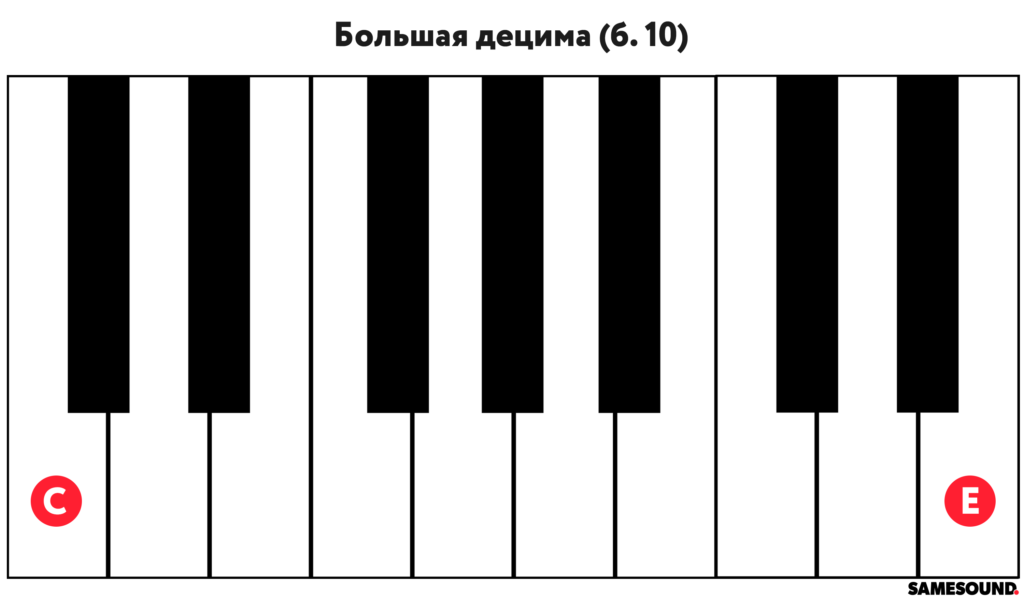

- Большая децима

- Чистая ундецима

- Увеличенная ундецима или уменьшенная дуодецима

- Чистая дуодецима

- Малая терцдецима

- Большая терцдецима

- Малая квартдецима

- Большая квартдецима

- Чистая квинтдецима

Классификация и виды интервалов

Классифицировать и упорядочить интервалы можно по нескольким признакам:

- Особенностям «взятия»;

- Общему количеству ступеней в интервале;

- Качеству интервала;

- Особенностям состава.

Виды музыкальных интервалов по особенностям “взятия”

По методу «взятия» различают два вида интервалов:

- Гармонические интервалы, также называемые вертикальные, в которых звуки извлекаются одновременно;

- Мелодические интервалы или горизонтальные интервалы, звуки которых звучат последовательно.

Виды музыкальных интервалов на основе количества ступеней

Классификация интервалов по количеству ступеней отталкивается от цифрового обозначения, связанного с каждым интервалом:

| Количество ступеней в интервале (цифровое обозначение) | Название интервала на русском | Название интервала на английском |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Прима | Unison |

| 2 | Секунда | Second |

| 3 | Терция | Third |

| 4 | Кварта | Fourth |

| 5 | Квинта | Fifth |

| 6 | Секста | Sixth |

| 7 | Септима | Seventh |

| 8 | Октава | Octave |

| 9 | Нона | Ninth |

| 10 | Децима | Tenth |

| 11 | Ундецима | Eleventh |

| 12 | Дуодецима | Twelfth |

| 13 | Терцдецима | Thirteenth |

| 14 | Квартдецима | Fourteenth |

| 15 | Квинтдецима | Fifteenth |

Виды музыкальных интервалов на основе их качественных характеристик

Качественные виды интервалов вносят уточнения в количественные определения. Именно для уточнения качественных характеристик интервала в название добавляют слова «увеличенный», «уменьшенный», «большой», «малый», «дважды увеличенный», «дважды уменьшенный» и «чистый».

Увеличенный интервал — это интервал, повышенный на полутон, уменьшенный — пониженный на полутон. Дважды увеличенные и уменьшенные интервалы повышаются и понижаются на целый тон.

| Название интервала | Английское обозначение | Краткая запись | Количество полутонов | Увеличенные или уменьшенные интервалы, равные исходному интервалу | Краткая запись увеличенного или уменьшенного интервала |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Чистая прима | Unison | ч. 1 | 0 | Уменьшенная секунда | ум. 2 |

| Малая секунда | Minor Second | м. 2 | 1 | Увеличенная прима | ув. 1 |

| Большая секунда | Major Second | б. 2 | 2 | Уменьшенная терция | ум. 3 |

| Малая терция | Minor Third | м. 3 | 3 | Увеличенная секунда | ув. 2 |

| Большая терция | Major Third | б. 3 | 4 | Уменьшенная кварта | ум. 4 |

| Чистая кварта | Perfect Fourth | ч. 4 | 5 | Увеличенная терция | ув. 3 |

| Увеличенная кварта или уменьшенная квинта | Augmented Fourth / Diminished Fifth | ув. 4 / ум. 5 | 6 | ||

| Чистая квинта | Perfect Fifth | ч. 5 | 7 | Уменьшенная секста | ум. 6 |

| Малая секста | Minor Sixth | м. 6 | 8 | Увеличенная квинта | ув. 5 |

| Большая секста | Major Sixth | б. 6 | 9 | Уменьшенная септима | ум. 7 |

| Малая септима | Minor Seventh | м. 7 | 10 | Увеличенная секста | ув. 6 |

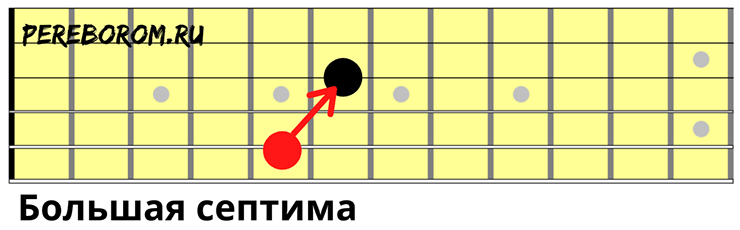

| Большая септима | Major Seventh | б. 7 | 11 | Уменьшенная октава | ум. 8 |

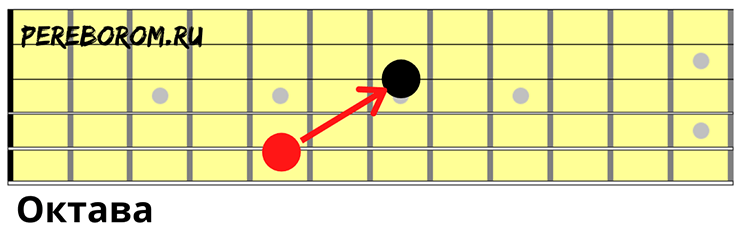

| Чистая октава | Octave | ч. 8 | 12 | Увеличенная септима | ув. 7 |

| Малая нона | Minor Ninth | м. 9 | 13 | Увеличенная октава | ув. 8 |

| Большая нона | Major Ninth | б. 9 | 14 | Уменьшенная децима | ум. 10 |

| Малая децима | Minor Tenth | м. 10 | 15 | Увеличенная нона | ув. 9 |

| Большая децима | Major Tenth | б. 10 | 16 | Уменьшенная ундецима | ум. 11 |

| Чистая ундецима | Perfect Eleventh | ч. 11 | 17 | Увеличенная децима | ув. 10 |

| Увеличенная ундецима или уменьшенная дуодецима | Augmented Eleventh / Diminished Twelfth | ув. 11 / ум. 12 | 18 | ||

| Чистая дуодецима | Perfect Twelfth | ч. 12 | 19 | Уменьшенная терцдецима | ум. 13 |

| Малая терцдецима | Minor Thirteenth | м. 13 | 20 | Увеличенная дуодецима | ув. 12 |

| Большая терцдецима | Major Thirteenth | б. 13 | 21 | Уменьшенная квартдецима | ум. 14 |

| Малая квартдецима | Minor Fourteenth | м. 14 | 22 | Увеличенная терцдецима | ув. 13 |

| Большая квартдецима | Major Fourteenth | б. 14 | 23 | Уменьшенная квинтдецима | ум. 15 |

| Чистая квинтдецима | Perfect Fifteenth | ч. 15 | 24 | Увеличенная квартдецима | ув. 14 |

Виды музыкальных интервалов по особенностям составления

Если же посмотреть на особенности составления, то здесь можно выделить четыре основных вида интервалов:

- Простые;

- Составные;

- Микроинтервалы;

- Особые интервалы.

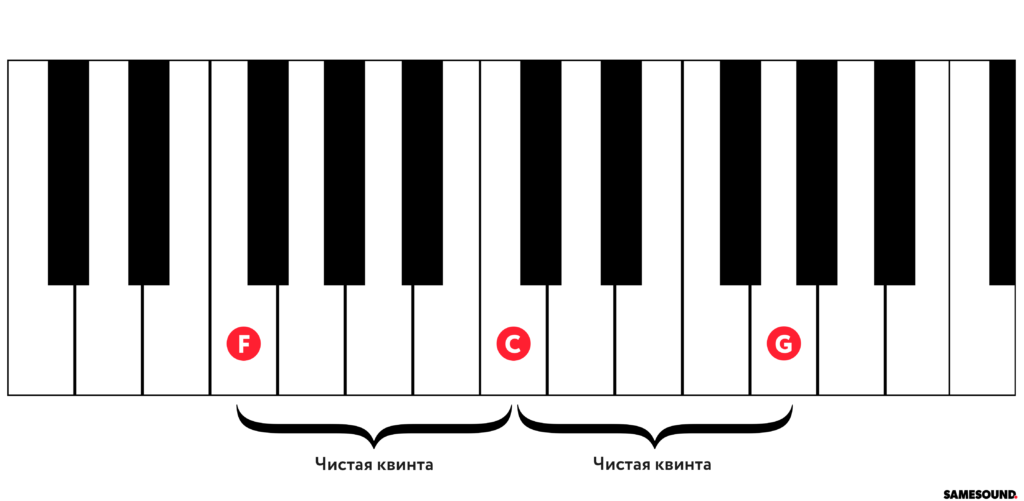

Важно отметить, что строить интервалы можно в обе стороны (как вверх, так и вниз) и от любой ноты — качество и количество промежуточных ступеней (тонов и полутонов) останется неизменным. Так, 5 ступеней вверх от ноты До приведут к образованию квинту с вершиной на ноте Соль, а 5 ступеней вниз образуют квинту с основанием на ноте Фа.

Простые интервалы

Простые интервалы существуют в пределах одной октавы, а их названиями служат порядковые числительные на латыни. Само по себе название интервала отражает количество ступеней между двумя звуками.

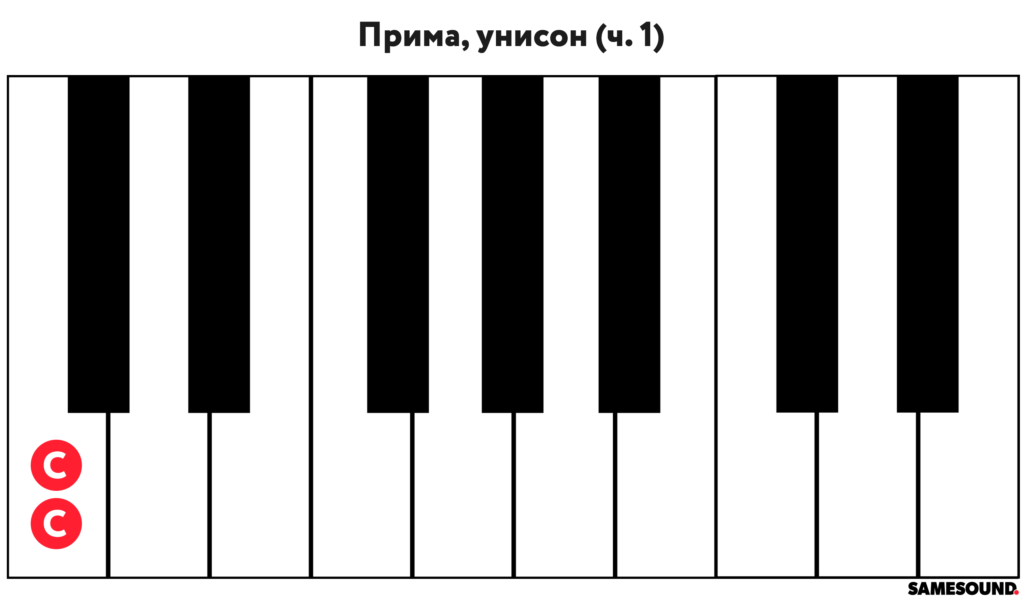

Прима

Прима (англ. Unison) образуется при помощи двух одинаковых звуков, и именно от этой особенности происходит английское название интервала — унисон. Значение слова «Унисон» совпадает со смыслом примы — одновременное звучание двух или более звуков одинаковой высоты.

Так как взять две одинаковых ноты на клавиатуре пианино не представляется возможным, прима обычно отображается двумя последовательными извлечениями звука. Единственный вариант взять одинаковые звуки — использовать два инструмента.

Тем не менее, такое положение вещей не относится к большинству струнных инструментов (гитара, скрипка, виолончель), чей гриф позволяет взять два идентичных звука на разных струнах.

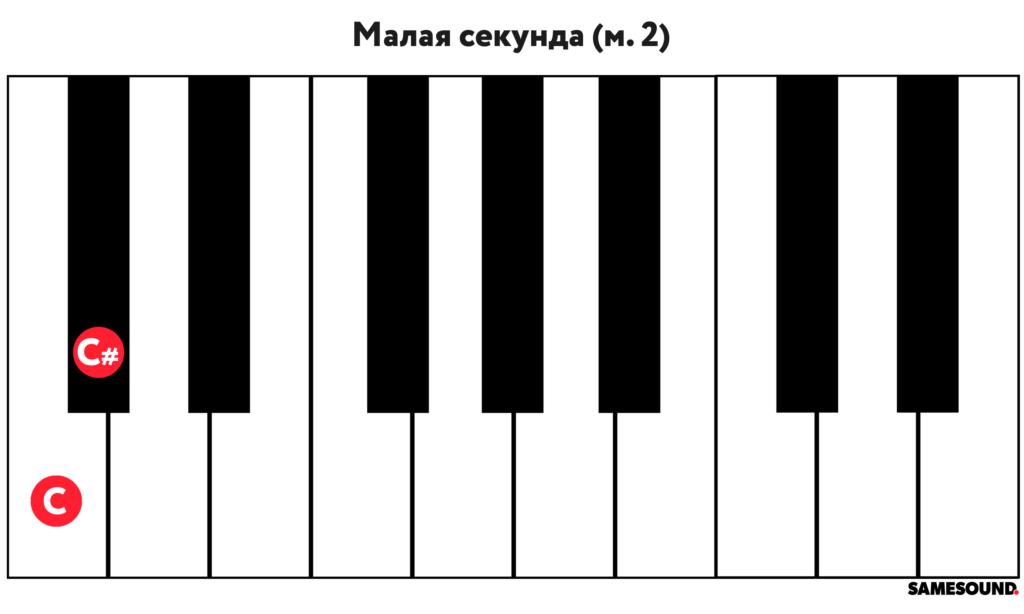

Малая секунда

Второй интервал в музыке — малая секунда (англ. minor second). В основе интервала — два звука, отличающиеся по высоте всего на полтона (вверх или вниз). Малая секунда обозначается буквенно-цифровым сочетанием «м. 2».

Большая секунда

Большая секунда (англ. major second) — интервал, звуки которого отличаются на целый тон. В музыкальной теории большая секунда обозначается «б. 2».

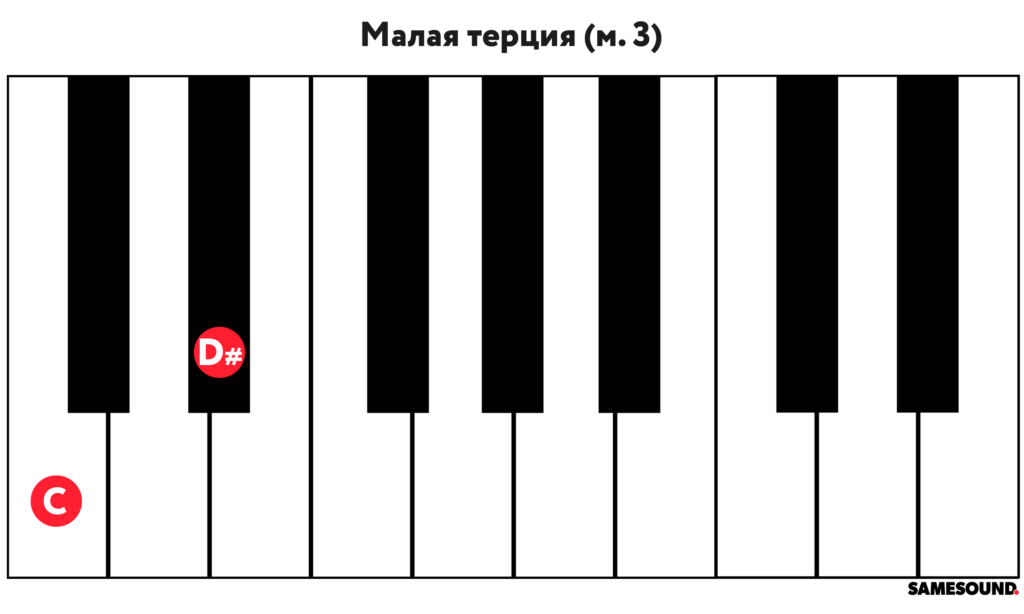

Малая терция

Следующий интервал — малая терция, обозначаемая «м. 3». Малая терция — нижний интервал минорного трезвучия, который в некоторых случаях может заменять минорный аккорд, не изменяя звуковых характеристик.

Большая терция

Большая терция — интервал в три ступени, обозначаемый «б. 3». В отличие от малой, большая терция — нижний интервал мажорного трезвучия. В некоторых случаях, большая терция может заменять мажорный аккорд.

Чистая кварта

Название кварты происходит от латинского слова «quarta» (лат. «четыре» или «четвертый»). В средние века в музыкальной теории звук кварты описывался как четвертый голос от тенора (лат. quarta vox), если вести счет по ступеням звукоряда вверх или вниз. В те времена тенор считался главным и чистым голосом, фундаментом многоголосной музыки.

В современной элементарной теории музыки принято различать несколько видов кварты — чистая, увеличенная и уменьшенная. С точки зрения практического использования, под термином кварта подразумевается чистая кварта, обозначаемая «ч. 4». Из наименования интервала понятно количество ступеней между основанием и вершиной кварты — 4 ступени.

Увеличенная кварта или уменьшенная квинта

Увеличенная кварта (обозначается «ув. 4») равна уменьшенной квинте («ум. 5»). Увеличенная кварта считается важным интервалом в теории музыки — на него опирается вся система мажорно-минорных ладов.

[jaw_panel_box panel_title=”Голос скептика” message_style=”info” ] — А где же здесь тритон?[/jaw_panel_box][jaw_clear]

Голос скептика: «А где же здесь тритон?»У тех, кто хотя бы поверхностно знаком с интервалами и теорией музыки, возникнет закономерный вопрос: “Почему пропустили тритон?”. Если посмотреть внимательнее, то он на месте, где и должен быть.

Тритон – интервал, звуки которого отдалены друг от друга тремя тонами (вверх или вниз). Фактически, тритон – другое название увеличенной кварты или уменьшенной квинты. Чистая кварта состоит из 2,5 тонов (5 полутонов), а чистая квинта из 3,5 тонов (7 полутонов). Увеличение кварты на полутон приведет к образованию увеличенной кварты или тритона, равно как уменьшение квинты на полутон приведет к образованию уменьшенной квинты или тритона.

Как ни крути, расстояние равно трем полным тонам.

Чистая квинта

Квинта — интервал, разница между основанием и вершиной которого составляет пять ступеней. Обозначается «ч. 5».

Малая секста

Секста — интервал в шесть ступеней или четыре тона, обозначающийся «м. 6».

Большая секста

Как и в случае с малой, расстояние между нотами в большой сексте составляет четыре тона. В отличие от малой сексты, между звуками большой сексты располагаются четыре с половиной тоной. В музыкальной теории записывается при помощи буквенно-цифрового обозначения «б. 6».

Малая септима

Септима — седьмой музыкальный интервал, расстояние между основанием и вершиной которого составляет семь ступеней. Между звуками малой септимы располагаются пять тонов, а сам интервал обозначается как «м. 7».

Большая септима

Главное отличие большой септимы от малой заключается в количество звуков между нотами: между основанием и вершиной располагаются пять с половиной тонов (пять тонов + один полутон). Большая септима обозначается как «б. 7».

Октава

Октава — восьмой и последний простой музыкальный интервал, расстояние участниками которого равно восьми ступеням. На слух октава воспринимается как устойчивый музыкальный интервал. Несмотря на то, что основание и вершина интервала очень похожи друг на друга, ноты отчетливо различаются по высоте.

В Древней Греции октаву называли «διὰ πασῶν», что буквально переводится как «через все струны». Свое современное название октава получила в средние века: музыканты использовали слово octavus (восьмая) наряду со словом diapason (диапазон).

В музыкальной теории октава записывается обозначением «ч. 8».

Составные интервалы

Составные интервалы получаются за счет сложения двух простых интервалов. Любые составные интервалы по объему превышают октаву.

Малая нона

Нона — условно девятый интервал, расстояние между звуками которого составляет девять ступеней. Для упрощения запоминания нону рассматривают как секунду через октаву. Исходя из этого, нона, как и секунда, делится на большую и малую, а значит интервал можно рассмотреть как малую секунду через октаву.

Малая нона обозначается как «м. 9».

Большая нона

Большую нону (обозначается «б. 9») может рассматриваться как большая секунда через октаву (б. 2 + ч. 8).

Малая децима

Интервал в музыке, чья ширина составляет десять ступеней, называется децима. Децима, как и другие составные интервалы превышает размером октаву.

С точки зрения состава, малая децима (обозначается «м. 10») представляет собой малую терцию через октаву (октава плюс малая терция), а между основанием и вершиной интервала располагаются пятнадцать полутонов.

Большая децима

Большая децима («б. 10») — это большая терция через октаву. Между звуками интервала находятся шестнадцать полутонов.

Чистая ундецима

Музыкальный интервал шириной в 11 ступеней называется ундецима и обозначается как «ч. 11». Рассмотрение ундецимы в качестве составного интервала позволяет обозначить ее как октаву через кварту. Чистая ундецима состоит из семнадцати полутонов.

С точки зрения гармонии ундецима соответствует кварте, обладая теми же свойствами и особенностями. В джазовой теории музыки ундециму определяют как пятую терцию после основного тона.

Увеличенная ундецима или уменьшенная дуодецима

Увеличенная ундецима (обозначается «ув. 11») равна уменьшенной дуодециме («ум. 12»). Интервалы идентичны по своим качествам увеличенной кварте и уменьшенной квинте, представляя собой сумму из октавы и увеличенной кварты, и октавы и уменьшенной квинты соответственно.

Чистая дуодецима

Двенадцатый музыкальный интервал, шириной в 12 ступеней, называется дуодецима (обозначается «ч. 12»). Дуодецима состоит из октавы и квинты, а в средние века ее называли «diapason cum diapente», что означает «октава с квинтой».

Знаменитый русский композитор Сергей Рахманинов брал чистую дуодециму на клавиатуре фортепиано мизинцем и большим пальцем одной руки.

Малая терцдецима

Тринадцатый музыкальный интервал, состоящий из 13 ступеней, называется терцдецимой. Терцдецима представляет собой комбинацию октавы и сексты. Как и секста, терцдецима бывает малой и большой.

В малую терцдециму входят 20 полутонов, а интервал обозначается как «м. 13».

Большая терцдецима

Большая терцдецима состоит из октавы и большой сексты или из 21 полутона. Большая терцдецима записывается буквенно-цифровым обозначением «б. 13».

Малая квартдецима

Квартдецима — четырнадцатый музыкальный интервал, расстояние между основанием и вершиной в которой составляет 14 ступеней. Состоит из октавы и септимы, ввиду чего может быть как малой, так и большой.

Малая квартдецима состоит из 11 тонов (22 полутонов) и обозначается как «м. 14».

Большая квартдецима

Большая квартдецима («б. 14») состоит из чистой октавы и большой септимы. В составе интервала 23 полутона.

Чистая квинтдецима

Чистая квинтдецима («ч. 15») — составной интервал, в который входят две октавы. Между основанием и вершиной квантдецимы располагаются 15 ступеней (12 тонов, 24 полутона). Иногда квартдециму обозначают цифрой 16 (две октавы).

Интервалы в музыке играют очень важную роль. Музыкальные интервалы – первооснова гармонии, «строительный материал» произведения.

Вся музыка сложена из нот, но одна нота – это ещё не музыка – равно, как и любая книга написана буквами, но буквы сами по себе ещё не несут смысла произведения. Если взять смысловые единицы крупнее, то в текстах это будут слова, а в музыкальном произведении – созвучия.

Гармонические и мелодические интервалы

Созвучие двух звуков называется интервалом, причём эти два звука можно сыграть, как вместе, так и по очереди, в первом случае интервал будет называться гармоническим, а во втором – мелодическим.

Что значит гармонический интервал и мелодический интервал? Звуки гармонического интервала берутся одновременно и поэтому сливаются в единое созвучие – гармонию, которая может прозвучать очень мягко, а может и остро, колюче. В мелодических интервалах звуки играются (или поются) по очереди – сначала один, потом другой. Эти интервалы можно сравнить с двумя соединенными звеньями цепочки – из таких звеньев состоит любая мелодия.

Роль интервалов в музыке

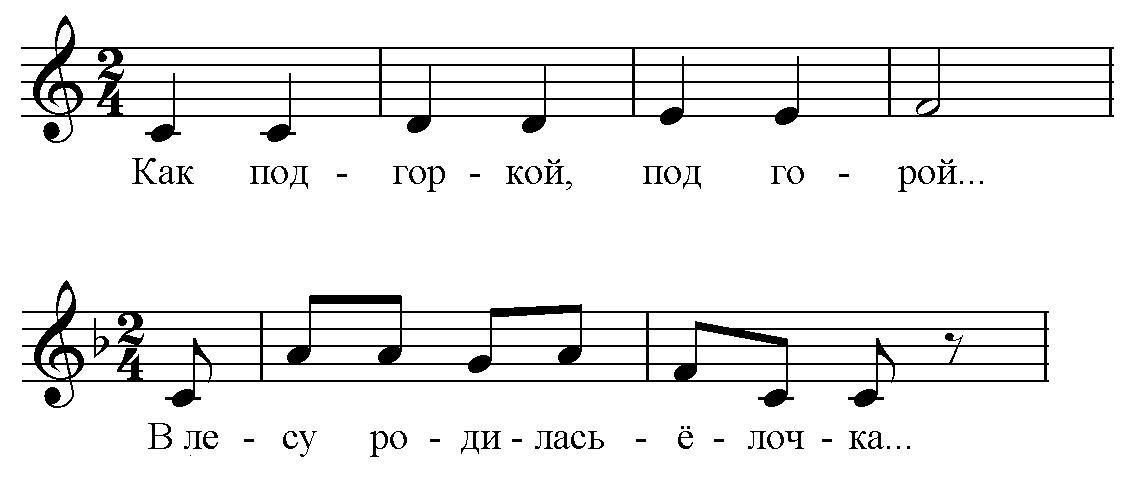

Какова же сущность интервалов в музыке, например, в мелодии? Представим себе две разные мелодии и проанализируем их самое начало: пусть это будут всем известные детские песенки «Как под горкой, под горой» и «В лесу родилась ёлочка».

Давайте сравним начала этих песенок. Обе мелодии начинаются с ноты «до», но совершенно по-разному развиваются дальше. В первой песенке мы слышим, будто мелодия маленькими шажками поднимается по ступенькам – сперва от нотки до к ноте ре, потом от ре к ми и т.д. А вот на первых же словах второй песенки мелодия сразу скачком уходит вверх, как бы перескакивая сразу через несколько ступенек («в лесу» – ход от до к ля). Действительно, между нотами до и ля поместились бы ещё совершенно спокойно ре ми фа и соль.

Движение вверх и вниз по ступенькам и скачком, а также повторение звуков на одной и той же высоте – это всё музыкальные интервалы, из которых, в конечном счёте, складывается общий мелодический рисунок.

Да, кстати. Если вы взялись изучать музыкальные интервалы, то вы наверняка уже знаете ноты и сейчас хорошо меня поняли. Если пока не знаете нот – ознакомьтесь со статьёй «Нотная грамота для начинающих».

Свойства интервалов

Вы уже поняли, что интервал – это некий промежуток, расстояние от одной ноты до другой. Теперь разберёмся, в чём же это расстояние можно измерить, тем более что пришла пора узнать названия интервалов.

Каждый интервал имеет два свойства (или две величины) – это ступеневая и тоновая величина. Ступеневая величина зависит от того, сколько музыкальных ступеней охватывает интервал – одну, две, три и т.д. (причём сами звуки интервала тоже считаются). Ну, а тоновая величина относится к составу конкретных интервалов – подсчитывается точное число тонов (или полутонов), которые умещаются в интервале. Эти свойства иногда называют по-другому – количественная и качественная величина, суть их при этом не меняется.

Музыкальные интервалы – названия

Для названия интервалов применяют числительные на латинском языке, название определяется свойствами интервала. В зависимости от того, сколько ступеней охватывает интервал (то есть от ступеневой или количественной величины), даются названия:

1 – прима

2 – секунда

3 – терция

4 – кварта

5 – квинта

6 – секста

7 – септима

8 – октава.

Для названия интервалов используются эти латинские слова, но для записи всё-таки удобнее применять цифровые обозначения. Например, кварту можно обозначить цифрой 4, сексту – цифрой 6 и т.д.

Интервалы бывают чистыми (ч), малыми (м), большими (б), уменьшёнными (ум) и увеличенными (ув). Эти определения исходят из второго свойства интервала, то есть тонового состава (тоновой или качественной величины). Эти характеристики присоединяются к названию, например: чистая квинта (сокращённо ч5) или малая септима (м7) , большая терция (бз) и т.д.

Чистые интервалы – это чистая прима (ч1), чистая октава (ч8), чистая кварта (ч4) и чистая квинта (ч5). Малыми и большими бывают секунды (м2, б2), терции (м3, б3), сексты (м6, б6) и септимы (м7, б7).

Число тонов в каждом интервале нужно запомнить. Например, в чистых интервалах так: в приме 0 тонов, в октаве 6 тонов, в кварте – 2,5 тона, а в квинте – 3,5 тона. Чтобы повторить тему тонов и полутонов – почитайте статьи «Знаки альтерации» и «Как называются клавиши фортепиано», где эти вопросы подробно рассматриваются.

Интервалы в музыке – итоги

В данной статье, которую можно было бы назвать уроком, мы с вами разобрали интервалы в музыке, выяснили, как они называются, какие имеют свойства, и какую роль играют.

В дальнейшем вас ждёт расширение знаний по этой очень важной теме. Почему она так важна? Да потому что музыкальная теория – это универсальный ключ к пониманию любого музыкального произведения.

Что делать, если у вас не получилось разобраться в теме? Первое – отдохнуть и прочитать всю статью ещё раз сегодня или завтра, второе – поискать информацию на других сайтах, третье – связаться с нами в группе вконтакте или задать свои вопросы в комментариях.

Если всё понятно, то я очень рад! Внизу страницы вы найдёте кнопочки различных соцсетей – поделитесь данной статьёй со своими друзьями! Ну, а после вы можете немного расслабиться и посмотреть прикольное видео – пианист Денис Мацуев импровизирует на тему песенки «В лесу родилась ёлочка» в стилях разных композиторов.

Денис Мацуев “В лесу родилась ёлочка”

Редактор, корректор: Полина Полянская

Что помогает нам измерять расстояние между звуками в музыке?

В этой статье мы с вами изучим интервалы. Тема очень важная и, в то же время, простая. Если вы незнакомы с интервалами, не упустите свой шанс. Итак:

Интервалы

Интервалом называют сочетание двух звуков, взятых одновременно или последовательно. Существуют:

- мелодический интервал. Звуки такого интервала взяты последовательно;

- гармонический интервал. Звуки взяты одновременно.

Поскольку в мелодическом интервале звуки берутся последовательно, то можно встретить восходящее или нисходящее движение. Оба вида интервалов читаются вверх от основания. Нисходящие мелодические читаются вниз, обязательно указывая направление.

| Мелодический интервал | Гармонический интервал |

|---|---|

|

|

| В нотах читаем: ми — ля (восходящий интервал), играем звуки последовательно. | В нотах читаем: ми — ля, играем звуки одновременно. |

Интервалы характеризуются двумя величинами: качественной и количественной:

- количественная величина выражается количеством нот, составляющих интервал (2 звучащие ноты и количество не звучащих нот между ними);

- качественная величина выражается количеством тонов и полутонов, составляющих интервал.

Простые интервалы

Интервалы, которые образуются в пределах одной октавы, называются простыми (за исключением особенного интервала «тритон», который, несмотря ни на что, тоже образуется в пределах одной октавы, но его не причисляют к простым). Таких интервалов 8, каждый имеет своё название. Кстати, названия интервалов — это порядковые числительные на латинском языке. Название интервала показывает количество ступеней между основанием и вершиной интервала. Приводим список всех восьми интервалов. Слева — цифра, справа — латинское название:

| Таблица основных интервалов | ||||||||||||||||||

|

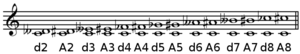

Рисунок 1. Основные интервалы

На рисунке вы видите все 8 простых интервалов. Под нотами цифры обозначают названия интервалов: 1 — прима, 2 — секунда, 3 — терция, 4 — кварта, 5 — квинта, 6 — секста, 7 — септима и 8 — октава. Интервалы на рисунке построены вверх от ноты «до».

Основные интервалы

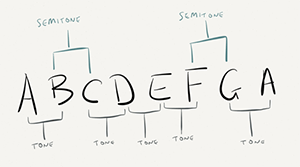

Расстояние между двумя соседними нотами может быть равно как целому тону (например, между «до» и «ре»), так и полутону (например, между «ми» и «фа»). Очевидно, что одной количественной величины не достаточно, чтобы точно определить интервал: между «до» и «ре» — секунда, между «ми» и «фа» — секунда. Но в первом случае между звуками целый тон, а во втором — полутон. Выходит, это разные секунды?

Для того, чтобы обозначить точное расстояние между звуками, к названиям интервалов добавляют уточнения: большой/ малый/ чистый/ уменьшённый/ увеличенный,. Наша секунда может быть большой («до» — «ре» — целый тон) и малой («ми» — «фа» — полутон). Чуть ниже разберёмся, как эти уточнения работают, а сейчас вспомним, что октава состоит из 12-ти звуков. Помните, мы это изучали в разделе «Нотная грамота»? Мы рассматривали 7 основных и 5 производных нот (на клавиатуре фортепиано производные ноты окрашены чёрным цветом)

Рисунок 2. Октава

Теперь посмотрим, как работают «уточнения»: ниже приводим таблицу с названиями интервалов между всеми 12-тью звуками октавы:

| Таблица основных интервалов | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Все вышеперечисленные интервалы и являются основными. Их также называют диатоническими интервалами. Забегая вперёд, отметим, что эти интервалы образуются как между нотами натурального мажора, так и натурального минора (слово «диатонический» означает натуральный минор или мажор).

Напоследок

Название интервала (прима, секунда…) всегда зависит только от нот и не меняется в зависимости от количества полутонов между звуками. Ноты дают название интервалу, количество полутонов уточняет интервал.

Пример: рассмотрим всё ту же секунду, ноты «до» и «ре». Итак, несколько вариантов:

Рисунок 3. Несколько вариантов интервала «секунда»

- «до» — «ре диез» — увеличенная секунда (полтора тона). Энгармонически равна малой терции, но таковой не является (почему?);

-

«до» — «ре» — большая секунда (целый тон);

-

«до» — «ре бемоль», малая секунда (полутон);

-

«до» — «ре дубль бемоль», уменьшённая секунда (0 тонов). Энгармонически равна чистой приме, но называется секундой, поскольку «до» и «ре» — это секунда. Прима — это «до»-«до», «ре»-«ре» и т.д.

Ещё немножко: «до» — «до-диез» — это увеличенная прима, а «до» — «ре-бемоль», это малая секунда. В обоих случаях между звуками полутон, то есть эти интервалы энгармонически равны.

Наглядный пример

Для лучшего усвоения материала предлагаем следующую программу (ваш браузер должен поддерживать flash). Выбирайте, какой интервал нужно построить, укажите его основу. Программа сама построит интервал и покажет его вам как на клавиатуре фортепиано, так и на нотном стане. Под белыми клавишами вы увидите номера ступеней, задействованных в интервале. Успехов!

Итог

Вы познакомились с интервалами. Названия интервалов будут употребляться довольно часто, поэтому стоит запомнить таблицу основных интервалов.

Интервал – это созвучие двух нот. На уроках сольфеджио учат определять интервалы на слух, пропевают их, строят от каждой ноты.

Узнавать интервалы по их окраске важно, но для этого не обязательно учиться в музыкальной школе.

В этой статье мы поговорим о том, как строить интервалы и запоминать их звучание, чтобы отличать друг от друга.

Содержание статьи:

- Разновидности интервалов

- Простые интервалы

- Количественная и качественная величина интервала

- Тритон — Кварта или Квинта

- Увеличенный и уменьшенные интервалы

- Составные интервалы

- Как запоминать и отличать интервалы

Разновидности интервалов

Как мы уже сказали, интервалом в музыке называют соотношение двух звуков по высоте. Но прежде чем начать отличать и запоминать интервалы, нужно разобраться какими они бывают, в каком виде их можно встретить.

Интервалы могут быть гармоническими или мелодическими. Гармоническими называются те, в которых обе ноты звучат одновременно:

Мелодические – такие интервалы, в которых ноты звучат последовательно одна за другой:

Интервалы бывают простые и составные. Простые интервалы те, где оба звука лежат в пределах одной октавы. Составные интервалы — такие, в которых два звука отдалены друг от друга на октаву и более. Теперь подробнее поговорим об этом.

Простые интервалы

Простых интервалов всего 8. Каждый из них обозначается цифрой от 1 до 8 и имеет свое латинское название:

- 1 – прима

- 2 – секунда

- 3 – терция

- 4 – кварта

- 5 – квинта

- 6 – секста

- 7 – септима

- 8 – октава

Переводятся эти названия просто: Прима – первая, Секунда – вторая и так далее. Каждый интервал можно строить от любой ноты вверх или вниз. Давайте детально рассмотрим простые интервалы.

Прима – интервал, который обозначается цифрой 1. Эта цифра говорит, что оба звука интервала располагаются на одной ступени. В нотной записи Прима выглядит как две ноты, расположенные на одной высоте, например. До – До, Ми – Ми.

Секунда – интервал, который обозначается цифрой 2 и это говорит нам, что Секунда объединяет две ступени. Звуки этого интервала находятся на двух соседних нотах: До – Ре, Ми – Фа, Ля – Си и так далее:

Терция — вмещает 3 ступени. Первый звук находится на расстоянии трех ступеней от второго. Например: До – Ми, Фа – Ля, Си – Ре.

Кварта – обозначается цифрой 4 и охватывает 4 ступени:

Квинта охватывает 5 ступеней. Один звук будет являться первой ступенью, второй звук – пятой:

Секста – обозначается цифрой 6, охватывает 6 ступеней:

Септима – предпоследний интервал из ряда простых, его ширина равна 7 ступеням:

Октава – интервал последний среди простых. Октава очень похожа на Приму, только звуки повторяются на разной высоте, например Ре – Ре, Соль – Соль:

На первый взгляд все прозрачно и предельно понятно, но есть нюанс, о котором необходимо поговорить.

Изучение интервалов — дело непростое, но успех во многом зависит от преподавателя. Я смело могу рекомендовать вам Ирину Машковскую — талантливого педагога для детей и взрослых. На ее Ютуб канале вы найдете массу полезного.

Качественная величина интервала

До этого момента мы строили интервалы только между белыми клавишами, но ноты могут быть понижены или повышены знаками альтерации, в следствие чего появится интервал между белой и черной клавишами. Об этом и поговорим.

Как мы выяснили, каждый интервал охватывает какое-то количество ступеней. Но кроме ступеней, каждый интервал охватывает еще и определенное количество полутонов . Рассмотрим подробнее Секунду: посчитаем количество полутонов между нотами До и Ре:

Получилось 2 полутона (1 тон). Можно было бы сделать вывод, что Секунда состоит из двух полутонов. Но как тогда назвать интервал, который состоит из нот До и Ре бемоль?

Количество полутонов теперь равно 1, а ступеней по-прежнему 2. Раз количество ступеней не изменилось, значит и этот интервал — Секунда. Но два этих интервала звучат по-разному, хотя и носят одно название:

До-Ре:

До-Ре бемоь:

Чтобы их можно было отличать друг от друга, им присвоили характеризующие слова. Так интервал До-Ре получил название «Большая Секунда», а интервал До – Ре бемоль — «Малая Секунда».

То же самое происходит и с другими интервалами – при одинаковом количестве ступеней они могут иметь разное количество полутонов, а, следовательно и разные названия.

Малыми или Большими бывают только Секунды, Терции, Сексты и Септимы.

Остались следующие интервалы: Прима, Кварта, Квинта, Октава. Все они также имеют характеризующее слово – «Чистая». Полное название этих интервалов «Чистая прима», «Чистая кварта» и т.д. Слово «Чистая» появилось из-за физических свойств волны звука, которыми обладают эти интервалы. Не будем вдаваться в подробности, а просто запомним это.

Теперь посмотрите на таблицу и обратите внимание на интервал, о котором мы ничего не говорили прежде:

Тритон

Новый интервал – «Тритон». Он так называется потому, что охватывает целых три тона, что равно 6 полутонам. Давайте построим Тритон от ноты Фа: получим ноты Фа – Си.

Количество ступеней в этом интервале равно 4, что характерно для Кварты. Но прежде чем сделаем вывод, послушаем как он звучит:

Звучание не характерно для Кварты, не смотря на расстояние между звуками в 4 ступени.

А теперь отсчитаем 3 тона от ноты Си. Получились те же ноты, но в другом порядке — Си – Фа.

Вот как звучит этот тритон:

Теперь количество ступеней равно 5, что свойственно Квинте, но звучание не квинтовое. Так что это за интервал такой: Кварта, Квинта или Тритон? Чтобы разобраться в этом, нам надо затронуть еще одно понятие.

Увеличенные и уменьшенные интервалы

Увеличенным можно сделать Чистый или Большой интервал. Для этого нужно прибавить к нему полтона. Тем самым мы изменим качественную величину, но количество ступеней оставим прежним. Для примера возьмем Большую Секунду До-Ре:

Чтобы из Большой Секунды сделать Увеличенную, нужно прибавить к ней полтона. Повысим ноту Ре и получим интервал До-Ре диез. Количество ступеней по-прежнему равно 2, но качественная величина равна 1.5 тонам:

Теперь послушаем эту Увеличенную Секунду.

Вы слышите? Она звучит как Малая Терция. Отсюда можно сделать вывод, что определить на слух увеличенный или уменьшенный интервал невозможно. Но надо помнить, что называть интервал нужно так, как написано в нотах – Увеличенным или Уменьшенным. Но если задача определить интервал на слух, то называть его будем в соответствии с его звучанием.

Уменьшенные интервалы

Уменьшенными могут быть Чистые или Малые интервалы. Принцип тот же: чтобы сделать интервал Уменьшенным, нужно его сжать на полтона. Если у Малой Терции Си-Ре отнять полтона, то мы получим ноты Си-Ре бемоль. Количество ступеней по-прежнему равно 3, что соответствует Терции, но звучать она будет, как Большая Секунда.

Теперь вернемся к интервалу Фа-Си. Мы выяснили, что между этими нотами расстояние 4 ступени, и по логике это Кварта, но звучит она по-другому. Думаю, вы уже догадались, что интервал Фа-Си — это Увеличенная Кварта. Однако ее звучание очень характерное и не похоже на другие интервалы, поэтому для нее придумали отдельный термин – «Тритон».

Поменяем ноты Фа и Си местами — получим интервал Си-Фа. Он охватывает 5 ступеней, что свойственно Квинте, но звучит как Тритон. Не трудно догадаться, что интервал Си-Фа – это Уменьшенная Квинта.

Вывод: Когда мы видим в нотах интервал из 3 тонов, мы можем определить что это – Увеличенная Кварта, или Уменьшенная Квинта. Если интервал только слышим, можно сделать один вывод – это Тритон.

Составные интервалы

Составными называются такие интервалы, которые состоят из двух простых – Октавы и еще одного любого простого интервала. Составных интервалов всего 7 и все они шире Октавы. Так же как и простые интервалы, составные получили свои названия на латинском языке, а их перевод обозначает количество ступеней, которые они охватывают:

- 9 – Нона (интервал в 9 ступеней)

- 10 – Децима (10 ступеней)

- 11 – Ундецима (11 ступеней)

- 12 – Дуодецима (12 ступеней)

- 13 – Терцдецима (13 ступеней)

- 14 – Квартдецима (14 ступеней)

- 15 – Квинтдецима (15 ступеней)

Рассмотрим эти интервалы подробнее.

Нона – интервал из 9 ступеней. Проще будет считать, прибавляя к Октаве второй интервал: возьмем Октаву До-До и прибавим Секунду:

Так как мы использовали Большую Секунду, то получилась Большая Нона.

Чтобы сделать Малую Нону, к Октаве будем добавлять Малую Секунду:

Децима – Октава + Терция. Децима так же может быть Большой и Малой.

Ундецима – Октава + Кварта.

Дуодецима — Октава + Квинта.

Терцдецима — Октава + Секста.

Квартдецима – Октава + Септима.

Квинтдецима – Октава + Октава.

Как видите, составные интервалы так же делятся на Большие, Малые и Чистые. Таким же способом, добавляя полтона или отнимая, можно получить Увеличенный или Уменьшенный составной интервал.

А теперь послушайте, как звучат составные интервалы:

Как научиться отличать интервалы

Может быть вам сейчас кажется, что отличать интервалы на слух способны только «избранные». Но это не так, поверьте. Все мы более-менее в равных условиях, потому что за музыкальный слух отвечает конкретная часть мозга. Она есть у каждого, но у некоторых людей более развита. Тем не менее, музыкальный слух – это скорее навык, чем дар. Его можно тренировать и развивать, а при правильном подходе результат появится довольно скоро.

Чтобы научиться отличать интервалы на слух, нужно проделать несколько шагов. И первое что мы сделаем — поделим интервалы на 2 группы: консонирующие и диссонирующие. Напомню, что консонанс — это приятный звук, который хорошо «ложится на ухо». Диссонанс – резкий, неприятный звук.

Первый шаг.

Учимся отличать диссонанс от консонанса на слух. взгляните на таблицу и сравните звучание этих интервалов.

Консонансы:

Диссонансы:

Второй шаг.

Учимся определять как близко друг к другу расположены звуки. Сравните несколько интервалов с разной степенью удаленностью звуков.

Секунда — звуки тесно связаны друг с другом:

Кварта — звуки удалены друг от друга на среднее расстояние:

Септима — звуки расположены очень широко:

Третий шаг.

Придумываем ассоциации. Лучше всего, если вы сможете закрепить за конкретным интервалом знакомую песню или мелодию. Например, песенка «В лесу родилась елочка», начинается с Большой Сексты:

А гимн Российской Федерации начинается с Кварты:

Такие ассоциации можно подобрать практически к каждому интервалу. Я предложу вам свои ассоциации, но вы можете использовать свои.

Прима – Свадебный марш

Малая Секунда – «К Элизе»

Большая Секунда – «Вальс собачек»

Малая Терция – «Оле-Оле»

Большая Терция – «Чижик Пыжик»

Чистая Кварта – «В траве сидел кузнечик» , Гимн РФ

Чистая Квинта – Танец маленьких лебедей

Малая Секста – «Прекрасное далеко»

Большая Секста – «В лесу родилась елочка»

Малая Септима – Танго

Большая Септима – «Sleepy Shores»

Чистая Октава – «Утиные истории»

Если у вас возникает какая-то своя ассоциация при звучании интервалов, это даже лучше. Это не обязательно должна быть какая-то часть популярной песни. Возможны и другие фантазии. Например, в музыкальной школе предлагают представить ёжика, когда звучит Малая Секунда. Она и правда «колючая», поэтому это сравнение хорошо работает. Терции похожи на голос кукушки. Большая Терция – веселая кукушка, а Малая – грустная…

Заключение

Чтобы научиться слышать и отличать интервалы, нужно:

- Услышать консонанс это или диссонанс

- Близко звуки расположены или широко

- Привязать ассоциацию к каждому интервалу и привыкнуть к ней.

- Тренировать слух на гармонических и мелодических интервалах

Я надеюсь, данная статься принесла вам пользу и теперь вы знаете что такое интервалы в музыке, а так же поняли как научиться их отличать и запоминать.

Ну а на сегодня все. Если возникли вопросы, пишите в комментариях, вместе найдем решение. Подписывайтесь на мой youtube канал и добавляйтесь в группу вконтакте. До новых встреч!

Вы узнаете, что такое музыкальный интервал и как его использовать в композициях. Кроме того, разберем все виды и характеристики звучания. Покажу, как использовать обращение. Также будут таблицы, примеры и обозначения.

Содержание:

- Определение

- Простые интервалы

- Составные

- Дополнительные виды:

- Большие и малые

- Чистые

- Увеличенные и уменьшенные

- Построение интервалов

- Обращение

- Характерность

- Вывод

Музыкальный интервал

Музыкальный интервал — это расстояние между двумя нотами или звуками. Если ноты берутся одновременно, то это гармонический интервал. А если последовательно, то мелодический.

Нижний звук является основанием интервала, а верхний, его вершиной.

Чтобы определить расстояние между двумя нотами, нужно посчитать количество ступеней между ними.

И не важно где. На нотном стане или клавиатуре фортепиано. Мы просто считаем линейки и промежутки между двумя нотами.

Минимальная единица измерения по высоте между нотами один полутон. Два полутона составляют один тон.

Поэтому полутон, это универсальная единица измерения в музыке по высоте. И именно он равняется одному ладу на гитаре или одной клавише фортепиано.

В теории музыки интервалы принято называть латинскими названиями цифр. Например, если есть расстояние в 5 нот, то такой интервал называется Quinta. С латинского переводится, как пятый.

Таким образом, название подскажет, сколько ступеней присутствует внутри интервала.

Таблица интервалов в музыке

Для наглядности ниже вы можете посмотреть подробные таблицы интервалов в музыке. При желании, можете сделать шпаргалку по сольфеджио. Это пригодиться для запоминания как для детей, так и для взрослых.

| Простые интервалы | ||||

| Название интервала | Обозначение | Кол-во тонов | Кол-во ступеней | Тип |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Чистая прима | ч. 1 | 0 | 1 | Совершенный консонанс |

| Увеличенная прима | ув. 1 | 0,5 | 1 | Диссонанс |

| Уменьшенная секунда | ум. 2 | 0 | 2 | Совершенный консонанс |

| Малая секунда | м. 2 | 0,5 | 2 | Диссонанс |

| Большая секунда | б. 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Увеличенная секунда | ув. 2 | 1,5 | 2 | Несовершенный консонанс |

| Уменьшенная терция | ум. 3 | 1 | 3 | Диссонанс |

| Малая терция | м. 3 | 1,5 | 3 | Несовершенный консонанс |

| Большая терция | б. 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| Увеличенная терция | ув. 3 | 2,5 | 3 | Весьма совершенный консонанс |

| Уменьшенная кварта | ум. 4 | 2 | 4 | Несовершенный консонанс |

| Чистая кварта | ч. 4 | 2,5 | 4 | Весьма совершенный консонанс |

| Увеличенная кварта | ув. 4 | 3 | 4 | Диссонанс (другое название — тритон) |

| Уменьшенная квинта | ум. 5 | 3 | 5 | |

| Чистая квинта | ч. 5 | 3,5 | 5 | Весьма совершенный консонанс |

| Увеличенная квинта | ув. 5 | 4 | 5 | Несовершенный консонанс |

| Уменьшенная секста | ум. 6 | 3,5 | 6 | Весьма совершенный консонанс |

| Малая секста | м. 6 | 4 | 6 | Несовершенный консонанс |

| Большая секста | б. 6 | 4,5 | 6 | |

| Увеличенная секста | ув. 6 | 5 | 6 | Диссонанс |

| Уменьшенная септима | ум. 7 | 4,5 | 7 | Несовершенный консонанс |

| Малая септима | м. 7 | 5 | 7 | Диссонанс |

| Большая септима | б. 7 | 5,5 | 7 | |

| Увеличенная септима | ув. 7 | 6 | 7 | Совершенный консонанс |

| Уменьшенная октава | ум. 8 | 5,5 | 8 | Диссонанс |

| Чистая октава | ч. 8 | 6 | 8 | Совершенный консонанс |

Есть еще и составные типы. Их реже используют. Однако о них мы тоже будем вести речь.

| Составные интервалы | ||||

| Название | Обозначение | Кол-во тонов | Кол-во ступеней | Тип |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Чистая октава | ч. 8 | 6 | 8 | Консонанс |

| Увеличенная октава | ув. 8 | 6,5 | 8 | |

| Уменьшенная нона | ум. 9 | 6 | 9 | Диссонанс |

| Малая нона | м. 9 | 6,5 | 9 | |

| Большая нона | б. 9 | 7 | 9 | |

| Увеличенная нона | ув. 9 | 7,5 | 9 | |

| Уменьшенная децима | ум. 10 | 7 | 10 | Консонанс |

| Малая децима | м. 10 | 7,5 | 10 | |

| Большая децима | б. 10 | 8 | 10 | |

| Увеличенная децима | ув. 10 | 8,5 | 10 | |

| Уменьшенная ундецима | ум. 11 | 2 | 4 | Консонанс |

| Чистая ундецима | ч. 11 | 2,5 | 4 | |

| Увеличенная ундецима | ув. 11 | 3 | 4 | |

| Уменьшенная дуодецима | ум. 12 | 3 | 5 | Консонанс |

| Чистая дуодецима | ч. 12 | 3,5 | 5 | |

| Увеличенная дуодецима | ув. 12 | 4 | 5 | |

| Уменьшенная терцдецима | ум. 13 | 3,5 | 6 | Консонанс |

| Малая терцдецима | м. 13 | 4 | 6 | |

| Большая терцдецима | б. 13 | 4,5 | 6 | |

| Увеличенная терцдецима | ув. 13 | 5 | 6 | |

| Уменьшенная квартдецима | ум. 14 | 4,5 | 7 | Диссонанс |

| Малая квартдецима | м. 14 | 5 | 7 | |

| Большая квартдецима | б. 14 | 5,5 | 7 | |

| Увеличенная квартдецима | ув. 14 | 6 | 7 | |

| Уменьшенная квинтдецима | ум. 15 | 5,5 | 8 | Консонанс |

| Чистая квинтдецима | ч. 15 | 6 | 8 |

Простые интервалы

Простые интервалы находятся в пределах одной октавы. Ступенчатая величина определяется количеством охватываемых ступеней. В пределах октавы есть 8 ступеней.

Тоновая величина определяется количеством заключенных тонов. Она тоже нужна поскольку ступенчатая величина интервала определяет приблизительное расстояние.

К примеру, секунда До — Ре составляет целый тон. А секунда Ми — Фа составляет полутона.

Между основными ступенями звукоряда есть следующие интервалы.

Давайте посмотрим на основные.

Сначала идут две ноты одной высоты. Такой интервал называется «Prima» (прима) или «Unison» (унисон). Нота, расположенная на ступень выше, дает интервал в секунду. Поэтому и называется «Secunda» (секунда).

Следующая ступень даст интервал в терцию «Tertia» (три ступени).

Далее идет кварта «Quarta», то есть четыре ступени. Затем квинта «Quinta», то есть пять ступеней. Потом секста «Sexta», то есть шесть ступеней. После нее идет септима «Septima» с семью ступенями.

Наконец, возвращаясь к первоначальной ноте октавой выше, получаем интервал в октаву. Отсюда и название «Octave».

Все это простые диатонические интервалы. Они принадлежат одной тональности. В данном случае, ноте «До».

Но при одинаковой ступеневой величине, один и тот же интервал в музыке может иметь разное количество тонов. Поэтому интервалы могут быть большие, малые и чистые. А также увеличенные и уменьшенные.

Секунды, терции, сексты и септимы могут быть как малыми, так и большими.

А примы, кванты, квинты и октавы являются чистыми или совершенными интервалами. Они никогда не могут быть большими или малыми.

Секунда

Секунда (лат. Secunda — вторая) — это интервал в две ступени. Такой звук приземленный, прижимистый. Его используют в частях, которые должны подогревать и готовить слушателя к чему-то важному.

Часто используют в хип-хоп культуре во время читки рэпа.

Интервал секунда в музыке может быть большим (б) и малым (м). Характеристика звучания тут разная. Большая очень приземленная и прижимистая. Она четкая, структурированная и конкретная.

Маленькая кажется грустной. Может создавать большой нагнетающий эффект при использовании фригийского лада.

Терция

Терция (лат. tertia — третья) — это музыкальный интервал в три ступени. Она гармоничная и легко воспринимается.

Часто используется в классической музыке. Это такой добрый и успокаивающий интервал. Он всегда создает уютное сочетание и состояние слушателя.

Очень гармоничный. Часто присутствует в музыке Моцарта.

Бывает большая (б) и малая (м) терция. Большая всегда звучит радостно, а малая грустно.

Этот музыкальный интервал в 3 ступени определяет, как будет звучать аккорд. Кстати, он тоже состоит из терции.

Самая первая терция стоит в низу аккорда. Она определяет, насколько аккорд будет звучать грустно или весело.

Кварта

Кварта (лат. quarta — четвертая) — интервал в четыре ступени. Он очень динамичный и яркий. Звучит кричаще.

Очень похожа на фанфары потому что они звучат торжественно.

Интервал Тритон

Интервал тритон находится между квартой и квинтой.

В средние века он являлся дьявольским интервалом. За его использование в то время могли запросто сжечь на костре. В 19 веке его еще называли «Черт в музыке» (от лат. diabolus in musica).

Почему он является таким страшным?

Дело в том, что он является сильным диссонансом. То есть не строящимся интервалом. Находится прямо по середине в пределах одной октавы. Также он обращается сам на себя.

Вот почему его не любили в средние века.

Сейчас его используют, когда нужно передать что-то таинственное, секретное и ужасное. Считается, что у него очень плохая энергетика.

Часто используется в heavy metal.

Квинта

Квинта (лат. quinta — пятая) — это интервал в пять ступеней. Хорошо подойдет для неземного восприятия, которое не вяжется с чем-то бытовым и простым.

Используют в тех композициях, где нужно создать больше драматизма. Можно использовать в эпичных моментах. Он звучит широко, таинственно и пространственно.

Секста

Секста (от лат. sexta — шестая) — это расстояние в шесть нот. Она очень масштабная и большая. За счет этого создается важность какого-то события.

Есть большая (б) и малая секста (м). За счет них произведения получают более серьезное восприятие.

Септима

Септима (лат. septima — седьмая) — это музыкальный интервал в 7 ступеней. Очень плохой с точки зрения гармонии. Звучит не приятно. Бывает большим и малым.

Используется в аккордах. Например, в септаккордах на крайнем расстоянии между нотами. Но если внутрь добавить несколько нот, то аккорд будет звучать симпатично.

Септима звучит грязно. Можно использовать в тех случаях, когда хотите взбунтовать нервную систему слушателя.

Однако можно вовремя переключить ее на более устойчивую ноту. Например, на тонику на первую ступень. Тогда будет хороший результат.

Октава

Октава (лат. octava — восьмая) — это музыкальный интервал в восемь ступеней. Повторяется один и тот же звук через диапазон.

К примеру, у нас есть на первой ступени нота. Далее мы ее просто повторяем в следующем диапазоне (октаве).

Это чистый интервал. Поэтому его легко использовать во многих музыкальных композициях. За счет расстояния в 8 ступеней достигается масштабность и объемность звучания.

К примеру, у нас идет звук конкретного инструмента. Нам он кажется слишком плоским и простым. Как сделать так, чтобы обогатить его звучание и придать объем?

Можно добавить к нему еще одну ступеньку на октаву выше или ниже. Это зависит от того, чего именно нужно достичь.

Если нужна полнота звучания, то лучше добавлять снизу. Так получим хороший и насыщенный звук инструмента.

Если хотим увеличить тембровку и создать новые обертона, то можно добавить октаву сверху. В итоге, получим яркий, четкий и насыщенный звук.

Большинство музыкантов ограничиваются использованием интервалов в пределах одной октавы. Это то, что мы рассмотрели ранее.

Но возникает необходимость играть чуть выше октавы.

Составные интервалы

Стоит сказать, что составные интервалы состоят из простых с добавлением одной или нескольких октав.

Такой вид может быть большим, малым, либо чистым, как соответствующий ему простой интервал.

Выходя за пределы октавы, первый встречный интервал будет охватывать девять ступеней. Он называется нона (Nona). Это секунда + октава.

Далее идет децима (Decima) или терция + октава. Затем ундецима (Undecima).

А вот двенадцати ступеневой интервал (Duodecimus) на практике не используется. Интервал в сексту + октава имеет название терцдецима (Tredecimus). Тут охват в 13 ступеней.

Однако, на практике расстояние шире 13 ступеней тоже не используют.

В принципе, его можно увеличивать до бесконечности. Но в этом нет большого смысла. Поскольку если мы пишем мелодию, то часто используем диапазон одной октавы.

Психологически так легче воспринимать ноты. Они идут последовательно и не имеют большой разброс.

Другие виды интервалов в музыке

Выше вы узнали, что основные виды интервалов в музыке делятся на простые и составные. Но есть дополнительные типы, о которых стоит упомянуть ниже.

Большие и малые интервалы

Интервалы могут быть большими «б» и малыми «м». Таким образом, расстояние между До и Ре ♭ — малая секунда (м2). А между До и Ре натуральной — большая секунда (б 2).

Между До и Ми ♭ будет интервал в малую терцию (м 3). До и Ми натуральное образуют большую терцию (б 3). Интервал в кварту является чистым (ч 4).

Но если поднимем верхнюю ноту кварты на полутон, то получим увеличенную кварту (ув). Она называется тритоном. Потому что между нотами До и Соль бемоль три тона.

Далее добираемся до пятой ступени, образуя чистую квинту (ч 5). Затем идет малая секста (м 6). А До и Ля натуральные образуют большую сексту (б 6).

После идет малая (м 7) и большая септима (б 7). Затем чистая октава (ч 8).

Давайте вернемся к прошлой схеме (картинке) «Главные музыкальные интервалы». Посмотрим, какие у нас были интервалы в диатонической гамме.

В гамме До мажор мы имеем большую секунду. На рисунке обозначено, как Second. Затем идет большая терция, чистая кварта и чистая квинта. Далее большая секста, большая септима и чистая октава.

То есть все другие интервалы не участвуют в формировании диатонической гаммы. Но здесь их можно встретить если отчитывать не от ноты До, а от других ступеней.

Например, можно найти малую секунду (м 2) между седьмой ступенью и восьмой. Между ними полутон, но две ступени.

Малая терция (м 3) между третьей ступенью и пятой. То есть между Ми и Соль.

Большую терцию (б 3) мы можем найти между первой и третьей ступенью.

А между третьей ступенью и восьмой у нас малая секста (м 6). То есть между Ми и До.

В итоге, гамма содержит в себе все возможные интервалы. Но если будем добавлять полутона по ступенькам последовательно, то получим то, как на картинке «Главные музыкальные интервалы»

Чистые интервалы

Чистые интервалы при исполнении звучат слитно (мягко). При обращении они тоже образуют чистые интервалы. Поэтому их еще называют консонирующими.

Слитность звучания обусловлена тем, что гармоники двух нот тесно связаны друг с другом.

В диатонической гамме все кварты, квинты, примы и октавы являются чистыми.

Увеличенные и уменьшенные интервалы

Слова уменьшенный или увеличенный могут прибавляться к названию интервала. Они означают его расширение или сужение на хроматический полутон.

Если интервал большой и малый, но не чистый, тогда уменьшается малый, а увеличивается большой. Например, увеличенная секунда составляет 1,5 тона, а уменьшенная ноль тонов.

Возможны также дважды увеличенные и уменьшенные интервалы.

Например, нужно построить дважды увеличенную кварту. В таком случае, от основания До отсчитываем 3 ступени и получаем вершину Фа.

Дважды увеличенная кварта составляет 3,5 тона. А интервал До — Фа 2,5 тона. Тогда вершиной дважды увеличенной кварты будет Фа дубль диез.

Ниже показаны видоизмененные интервалы.

Если возьмем чистую квинту и сузим ее на полутон, то получим уменьшенную квинту (ум.5). Увеличивая на полутон чистую кварту, получаем увеличенную кварту (ув.4).

Эти две ноты одинаковые. Поэтому их еще называют энгармоническими. Потому что Соль бимоль и Фа диез, это одна и та же высота.

Увеличивая квинту, получаем увеличенную квинту (ув.5). Понижая шестую ступень, получаем уменьшенную сексту (ув.6). Но чаще всего такой интервал мы называем увеличенной квинтой.

А дальше идет пример пониженной второй ступени. Теоретически, мы получаем уменьшенную секунду (ум.2). Но на практике, применяем название малая секунда (м.2).

Тоже самое и с терцией.

Понятие уменьшенная терция на практике не применяется. Такая комбинация тонов обычно называется малой терцией (м.3).

В общем, если в чистый интервал добавлен полутон, то он становится увеличенным. А если из чистого расстояния вычли полутон, то такой интервал становится уменьшенным.

Как построить музыкальные интервалы

Чтобы построить музыкальные интервалы от заданной ноты, нужно установить ступеневую величину. То есть отсчитать требуемое количество ступеней. А затем отрегулировать если это нужно, тоновую величину расстояния знаком альтерации.

К примеру, нужно построить большую терцию от основания До диез.

В таком случае, отсчитываем две ступени и получаем вершину Ми. А поскольку большая терция составляет два тона, вершиной интервала должен быть звук Ми диез.

Можно построить малую терцию от основания До. Тогда отсчитываем две ступени и получаем вершину Ми. И поскольку малая терция имеет 1,5 тона, вершиной будет звук Ми бимоль.

Обращение интервалов

Если нужно сделать обращение интервалов, то достаточно передвинуть одну из нот в другую октаву. Причем сделать так чтобы верхняя нота стала нижней, а нижняя верхней.

В результате получается другой интервал, который в сумме с исходным составляет октаву.

Обращением является вычитание из октавы первоначального расстояния. Оба этих интервала являются взаимообратимыми.

Если мы вычтем название исходного интервала из девяти, то получим название обращенного. Например, между До и Ля расстояние в сексту (6 ступеней).

Для того чтобы узнать, какой интервал мы получим при обращении сексты, вычтем шесть из девяти. В итоге, получим три ступени или терцию между Ля и До.

Между До и Си интервал в септиму. 9 — 7 = 2. Поэтому между Си и До интервал в секунду.

Это правило работает во всем диапазоне.

Качество интервалов при обращении сменяется на противоположное. Исключение лишь составляют чистые. Последние всегда обращаются в чистые.

Большой интервал обращается в малый. А малый всегда обращается в большой. Например, обращение большой сексты в малую терцию.

И возьмем, к примеру, расстояние в малую терцию между Ми и Соль. Давайте я перенесу основание интервала Ми на октаву выше. В итоге, это будет большая секста.

Увеличенный интервал обращается в уменьшенный, а уменьшенный в увеличенный.

Итак, интервалы определяются охватом ступеней. То есть внутри малой секунды всегда две ступени, но при этом один полутон. А внутри большой секунды тоже две ступени, но уже два полутона.

Малая терция охватывает три ступени, но при этом три полутона. Четыре полутона дают большую терцию. Пять полутонов дают чистую кварту и так далее.

Ступеневой охват дает прима, секунда, терции и так далее. А тоновый охват определяет, будет ли интервал малым или большим, чистым, увеличенным или уменьшенным.

Пара взаимообратимых интервалов в ступеневых величинах выглядят так. Секунда и септима. Терция и секста. Кварта и квинта.

Равенством интервалов по их тоновой величине при различных названиях, называется энгармонизмом интервалов.

Например, увеличенная кварта и уменьшенная квинта энгармонически равны.

Также интервалы делятся на консонансы (мягкие на слух) и диссонансы (резкие).

Характерные интервалы

Характерные интервалы — это те расстояния между нотами, которые встречаются только в гармоническом мажоре или миноре.

То есть характерны только для гармонического вида лада. А также содержат в себе ступени, характерные только для него.

Ниже представлена таблица характерных интервалов.

| Название | Сокращенное обозначение | Ступени | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Гарм. мажор | Гарм. минор | ||

| Уменьшенная септима | ум. 7 | Ⅶ | Ⅶ |

| Увеличенная секунда | ув. 2 | Ⅵ | Ⅵ |

| Уменьшенная кварта | ум. 4 | Ⅲ | Ⅶ |

| Увеличенная квинта | ув. 5 | Ⅵ | Ⅲ |

Гармонический мажор

Ниже можно увидеть гамму натурального мажора в тональности До мажор.

А в гармоническом мажоре понижается 6 ступень, что вносит в мажор частичку минорной гаммы. Это придает ей особый минорный оттенок.

В гармоническом мажоре в результате понижения шестой ступени появляются характерные для гармонического лада интервалы.

Первый из них, является ярким признаком лада. Это увеличенная секунда. Строится она на шестой пониженной ступени Ля бимоль — Си.

Разрешается в чистую кварту от пятой. Поскольку Ля бимоль обращается в Соль, а Си в До.

Далее обращение увеличенной секунды в уменьшенную септиму, которая строится на 7 ступени Си — Ля бимоль. Она разрешается в чистую квинту от первой.

Следующая пара, у которых тоже пониженная шестая ступень. Это уменьшенная кварта от третьей Ми — Ля бимоль, которая разрешается в малую терцию от третьей.

Ля бимоль разрешается в Соль. А Ми остается на месте, так как это устойчивый звук.

И четвертый интервал, это обращение уменьшенной кварты. Это увеличенная квинта, которая строится на шестой пониженной ступени Ля бимоль — Ми.

Разрешается она в большую сексту от пятой.

Гармонический минор

А теперь давайте рассмотрим гармонический минор. Ниже гамма натурального минора в тональности Ля минор.

А в гармоническом миноре повышается седьмая ступень. Это придает ему большую остроту тяготения в тонику.

В результате повышения 7 ступени в гармоническом миноре тоже появляются четыре характерных интервала. Первый из них, это увеличенная секунда на 6 ступени Фа — Соль диез. Она разрешается в чистую кварту от пятой.

Далее обращение увеличенной секунды. Это уменьшенная септима, которая строится на повышенной 7 ступени Соль диез — Фа. Разрешается в чистую квинту от первой.

Следующая пара характерных интервалов, это уменьшенная кварта от 7 ступени Соль диез — До. Разрешается в малую терцию от первой.

И обращение уменьшенной кварты в увеличенную квинту от третьей До — Соль диез. Разрешается в большую сексту от третьей.

Таким образом, в гармоническом мажоре и миноре существует по четыре характерных интервала.

Еще одно замечание!

Во всех характерных интервалах содержится повышенная или пониженная ступень. И она характерная для гармонического мажора или минора.

Для мажора, это пониженная 6 ступень. А для минора — повышенная седьмая.

В заключение, подытожим правила построения характерных интервалов для гармонического мажора и минора.

Снизу прямоугольниками выделено в каком ладу (мажоре или миноре) строятся интервалы. Левая часть к мажору. Правая к минору. А центральная часть к обеим одновременно.

То есть увеличенная секунда и уменьшенная септима строятся от 6 и 7 ступеней, как в гармоническом мажоре и миноре. А вот ступени с увеличенной квинтой и уменьшенной квартой, в мажоре и миноре различаются.

Заключение

Теперь вы знаете, что такое интервалы в музыке. По сути, это главная составляющая всей музыкальной гармонии. Красота песни во многом заключается в их правильном подборе.

Ведь вся мелодия состоит из разных расстояний между звуками.

На самом деле интервалов не так много. И у каждого есть своя персональная характеристика звучания. Если вы ее знаете, то сможете грамотно внедрить подходящий вид в нужную часть композиции.

Например, у нас начало мелодии. Есть серединная часть и та, которая подготавливает слушателя. Также есть кульминационная часть, ради которой слушается вся композиция.

Получается, что для каждой части идет индивидуальная задача. Но те интервалы, которые используются в различных частях, будут восприниматься по-разному.

В кульминационной части можно психологически неверно поставить интервал, который отвечает не тем эмоциям. В таком случае, вы испортите весь трек.

Есть и те, которые звучат приземленно. Их легко использовать в каких-то не нагружаемых эмоциональных композициях.

Конечно же, в разных мелодиях мы фактически можем использовать все интервалы. Но на эмоциональные части композиции лучше брать те, которые максимально точно передают эмоциональное содержание.

Есть интервалы, которые не будут звучать так роскошно и эпично. Потому что изначально они имеют другую характеристику звучания. И если такой тип вы засунете в кульминационную часть, то потом не сможете получить эффект масштабности.

[ratings]

Melodic and harmonic intervals.

In music theory, an interval is a difference in pitch between two sounds.[1]

An interval may be described as horizontal, linear, or melodic if it refers to successively sounding tones, such as two adjacent pitches in a melody, and vertical or harmonic if it pertains to simultaneously sounding tones, such as in a chord.[2][3]

In Western music, intervals are most commonly differences between notes of a diatonic scale. Intervals between successive notes of a scale are also known as scale steps. The smallest of these intervals is a semitone. Intervals smaller than a semitone are called microtones. They can be formed using the notes of various kinds of non-diatonic scales. Some of the very smallest ones are called commas, and describe small discrepancies, observed in some tuning systems, between enharmonically equivalent notes such as C♯ and D♭. Intervals can be arbitrarily small, and even imperceptible to the human ear.

In physical terms, an interval is the ratio between two sonic frequencies. For example, any two notes an octave apart have a frequency ratio of 2:1. This means that successive increments of pitch by the same interval result in an exponential increase of frequency, even though the human ear perceives this as a linear increase in pitch. For this reason, intervals are often measured in cents, a unit derived from the logarithm of the frequency ratio.

In Western music theory, the most common naming scheme for intervals describes two properties of the interval: the quality (perfect, major, minor, augmented, diminished) and number (unison, second, third, etc.). Examples include the minor third or perfect fifth. These names identify not only the difference in semitones between the upper and lower notes but also how the interval is spelled. The importance of spelling stems from the historical practice of differentiating the frequency ratios of enharmonic intervals such as G–G♯ and G–A♭.[4]

Size[edit]

Example: Perfect octave on C in equal temperament and just intonation: 2/1 = 1200 cents.

The size of an interval (also known as its width or height) can be represented using two alternative and equivalently valid methods, each appropriate to a different context: frequency ratios or cents.

Frequency ratios[edit]

The size of an interval between two notes may be measured by the ratio of their frequencies. When a musical instrument is tuned using a just intonation tuning system, the size of the main intervals can be expressed by small-integer ratios, such as 1:1 (unison), 2:1 (octave), 5:3 (major sixth), 3:2 (perfect fifth), 4:3 (perfect fourth), 5:4 (major third), 6:5 (minor third). Intervals with small-integer ratios are often called just intervals, or pure intervals.

Most commonly, however, musical instruments are nowadays tuned using a different tuning system, called 12-tone equal temperament. As a consequence, the size of most equal-tempered intervals cannot be expressed by small-integer ratios, although it is very close to the size of the corresponding just intervals. For instance, an equal-tempered fifth has a frequency ratio of 27⁄12:1, approximately equal to 1.498:1, or 2.997:2 (very close to 3:2). For a comparison between the size of intervals in different tuning systems, see § Size of intervals used in different tuning systems.

Cents[edit]

The standard system for comparing interval sizes is with cents. The cent is a logarithmic unit of measurement. If frequency is expressed in a logarithmic scale, and along that scale the distance between a given frequency and its double (also called octave) is divided into 1200 equal parts, each of these parts is one cent. In twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET), a tuning system in which all semitones have the same size, the size of one semitone is exactly 100 cents. Hence, in 12-TET the cent can be also defined as one hundredth of a semitone.

Mathematically, the size in cents of the interval from frequency f1 to frequency f2 is

Main intervals[edit]

The table shows the most widely used conventional names for the intervals between the notes of a chromatic scale. A perfect unison (also known as perfect prime)[5] is an interval formed by two identical notes. Its size is zero cents. A semitone is any interval between two adjacent notes in a chromatic scale, a whole tone is an interval spanning two semitones (for example, a major second), and a tritone is an interval spanning three tones, or six semitones (for example, an augmented fourth).[a] Rarely, the term ditone is also used to indicate an interval spanning two whole tones (for example, a major third), or more strictly as a synonym of major third.

Intervals with different names may span the same number of semitones, and may even have the same width. For instance, the interval from D to F♯ is a major third, while that from D to G♭ is a diminished fourth. However, they both span 4 semitones. If the instrument is tuned so that the 12 notes of the chromatic scale are equally spaced (as in equal temperament), these intervals also have the same width. Namely, all semitones have a width of 100 cents, and all intervals spanning 4 semitones are 400 cents wide.

The names listed here cannot be determined by counting semitones alone. The rules to determine them are explained below. Other names, determined with different naming conventions, are listed in a separate section. Intervals smaller than one semitone (commas or microtones) and larger than one octave (compound intervals) are introduced below.

| Number of semitones |

Minor, major, or perfect intervals |

Short | Augmented or diminished intervals |

Short | Widely used alternative names |

Short | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Perfect unison | P1 | Diminished second | d2 | |||

| 1 | Minor second | m2 | Augmented unison | A1 | Semitone, half tone, half step | S | |

| 2 | Major second | M2 | Diminished third | d3 | Tone, whole tone, whole step | T | |

| 3 | Minor third | m3 | Augmented second | A2 | Trisemitone | ||

| 4 | Major third | M3 | Diminished fourth | d4 | |||

| 5 | Perfect fourth | P4 | Augmented third | A3 | |||

| 6 | Diminished fifth | d5 | Tritone | TT | |||

| Augmented fourth | A4 | ||||||

| 7 | Perfect fifth | P5 | Diminished sixth | d6 | |||

| 8 | Minor sixth | m6 | Augmented fifth | A5 | |||

| 9 | Major sixth | M6 | Diminished seventh | d7 | |||

| 10 | Minor seventh | m7 | Augmented sixth | A6 | |||

| 11 | Major seventh | M7 | Diminished octave | d8 | |||

| 12 | Perfect octave | P8 | Augmented seventh | A7 |

Interval number and quality[edit]

In Western music theory, an interval is named according to its number (also called diatonic number) and quality. For instance, major third (or M3) is an interval name, in which the term major (M) describes the quality of the interval, and third (3) indicates its number.

Number[edit]

The number of an interval is the number of letter names or staff positions (lines and spaces) it encompasses, including the positions of both notes forming the interval. For instance, the interval C–G is a fifth (denoted P5) because the notes from C to the G above it encompass five letter names (C, D, E, F, G) and occupy five consecutive staff positions, including the positions of C and G. The table and the figure above show intervals with numbers ranging from 1 (e.g., P1) to 8 (e.g., P8). Intervals with larger numbers are called compound intervals.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between staff positions and diatonic-scale degrees (the notes of diatonic scale).[b]

This means that interval numbers can also be determined by counting diatonic scale degrees, rather than staff positions, provided that the two notes that form the interval are drawn from a diatonic scale. Namely, C–G is a fifth because in any diatonic scale that contains C and G, the sequence from C to G includes five notes. For instance, in the A♭-major diatonic scale, the five notes are C–D♭–E♭–F–G (see figure). This is not true for all kinds of scales. For instance, in a chromatic scale, the notes from C to G are eight (C–C♯–D–D♯–E–F–F♯–G). This is the reason interval numbers are also called diatonic numbers, and this convention is called diatonic numbering.

If one adds any accidentals to the notes that form an interval, by definition the notes do not change their staff positions. As a consequence, any interval has the same interval number as the corresponding natural interval, formed by the same notes without accidentals. For instance, the intervals C–G♯ (spanning 8 semitones) and C♯–G (spanning 6 semitones) are fifths, like the corresponding natural interval C–G (7 semitones).

Notice that interval numbers represent an inclusive count of encompassed staff positions or note names, not the difference between the endpoints. In other words, one starts counting the lower pitch as one, not zero. For that reason, the interval C–C, a perfect unison, is called a prime (meaning «1»), even though there is no difference between the endpoints. Continuing, the interval C–D is a second, but D is only one staff position, or diatonic-scale degree, above C. Similarly, C–E is a third, but E is only two staff positions above C, and so on. As a consequence, joining two intervals always yields an interval number one less than their sum. For instance, the intervals C–E and E–G are thirds, but joined together they form a fifth (C–G), not a sixth. Similarly, a stack of three thirds, such as C–E, E–G, and G–B, is a seventh (C–B), not a ninth.

This scheme applies to intervals up to an octave (12 semitones). For larger intervals, see § Compound intervals below.

Quality[edit]

The name of any interval is further qualified using the terms perfect (P), major (M), minor (m), augmented (A), and diminished (d). This is called its interval quality. It is possible to have doubly diminished and doubly augmented intervals, but these are quite rare, as they occur only in chromatic contexts. The quality of a compound interval is the quality of the simple interval on which it is based. Some other qualifiers like neutral, subminor, and supermajor are used for non-diatonic intervals.

Perfect[edit]

Perfect intervals are so-called because they were traditionally considered perfectly consonant,[6]

although in Western classical music the perfect fourth was sometimes regarded as a less than perfect consonance, when its function was contrapuntal.[vague] Conversely, minor, major, augmented or diminished intervals are typically considered less consonant, and were traditionally classified as mediocre consonances, imperfect consonances, or dissonances.[6]

Within a diatonic scale[b] all unisons (P1) and octaves (P8) are perfect. Most fourths and fifths are also perfect (P4 and P5), with five and seven semitones respectively. One occurrence of a fourth is augmented (A4) and one fifth is diminished (d5), both spanning six semitones. For instance, in a C-major scale, the A4 is between F and B, and the d5 is between B and F (see table).

By definition, the inversion of a perfect interval is also perfect. Since the inversion does not change the pitch class of the two notes, it hardly affects their level of consonance (matching of their harmonics). Conversely, other kinds of intervals have the opposite quality with respect to their inversion. The inversion of a major interval is a minor interval, the inversion of an augmented interval is a diminished interval.

Major and minor[edit]

As shown in the table, a diatonic scale[b] defines seven intervals for each interval number, each starting from a different note (seven unisons, seven seconds, etc.). The intervals formed by the notes of a diatonic scale are called diatonic. Except for unisons and octaves, the diatonic intervals with a given interval number always occur in two sizes, which differ by one semitone. For example, six of the fifths span seven semitones. The other one spans six semitones. Four of the thirds span three semitones, the others four. If one of the two versions is a perfect interval, the other is called either diminished (i.e. narrowed by one semitone) or augmented (i.e. widened by one semitone). Otherwise, the larger version is called major, the smaller one minor. For instance, since a 7-semitone fifth is a perfect interval (P5), the 6-semitone fifth is called «diminished fifth» (d5). Conversely, since neither kind of third is perfect, the larger one is called «major third» (M3), the smaller one «minor third» (m3).

Within a diatonic scale,[b] unisons and octaves are always qualified as perfect, fourths as either perfect or augmented, fifths as perfect or diminished, and all the other intervals (seconds, thirds, sixths, sevenths) as major or minor.

Augmented and diminished[edit]

Augmented and diminished intervals on C. d2 (help·info),

A2 (help·info),

d3 (help·info),

A3 (help·info),

d4 (help·info),

A4 (help·info),

d5 (help·info),

A5 (help·info),

d6 (help·info),

A6 (help·info),

d7 (help·info),

A7 (help·info),

d8 (help·info),

A8 (help·info)

Augmented intervals are wider by one semitone than perfect or major intervals, while having the same interval number (i.e., encompassing the same number of staff positions): they are wider by a chromatic semitone. Diminished intervals, on the other hand, are narrower by one semitone than perfect or minor intervals of the same interval number: they are narrower by a chromatic semitone. For instance, an augmented third such as C–E♯ spans five semitones, exceeding a major third (C–E) by one semitone, while a diminished third such as C♯–E♭ spans two semitones, falling short of a minor third (C–E♭) by one semitone.

The augmented fourth (A4) and the diminished fifth (d5) are the only augmented and diminished intervals that appear in diatonic scales[b] (see table).

Example[edit]

Neither the number, nor the quality of an interval can be determined by counting semitones alone. As explained above, the number of staff positions must be taken into account as well.

For example, as shown in the table below, there are four semitones between A♭ and B♯, between A and C♯, between A and D♭, and between A♯ and E, but

- A♭–B♯ is a second, as it encompasses two staff positions (A, B), and it is doubly augmented, as it exceeds a major second (such as A–B) by two semitones.

- A–C♯ is a third, as it encompasses three staff positions (A, B, C), and it is major, as it spans 4 semitones.

- A–D♭ is a fourth, as it encompasses four staff positions (A, B, C, D), and it is diminished, as it falls short of a perfect fourth (such as A–D) by one semitone.

- A♯-E

is a fifth, as it encompasses five staff positions (A, B, C, D, E), and it is triply diminished, as it falls short of a perfect fifth (such as A–E) by three semitones.

| Number of semitones |

Interval name | Staff positions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 4 | doubly augmented second (AA2) | A♭ | B♯ | |||

| 4 | major third (M3) | A | C♯ | |||

| 4 | diminished fourth (d4) | A | D♭ | |||

| 4 | triply diminished fifth (ddd5) | A♯ | E |

Shorthand notation[edit]

Intervals are often abbreviated with a P for perfect, m for minor, M for major, d for diminished, A for augmented, followed by the interval number. The indications M and P are often omitted. The octave is P8, and a unison is usually referred to simply as «a unison» but can be labeled P1. The tritone, an augmented fourth or diminished fifth is often TT. The interval qualities may be also abbreviated with perf, min, maj, dim, aug. Examples:

- m2 (or min2): minor second,

- M3 (or maj3): major third,

- A4 (or aug4): augmented fourth,

- d5 (or dim5): diminished fifth,

- P5 (or perf5): perfect fifth.

Inversion[edit]

Major 13th (compound Major 6th) inverts to a minor 3rd by moving the bottom note up two octaves, the top note down two octaves, or both notes one octave

A simple interval (i.e., an interval smaller than or equal to an octave) may be inverted by raising the lower pitch an octave or lowering the upper pitch an octave. For example, the fourth from a lower C to a higher F may be inverted to make a fifth, from a lower F to a higher C.

There are two rules to determine the number and quality of the inversion of any simple interval:[7]

- The interval number and the number of its inversion always add up to nine (4 + 5 = 9, in the example just given).

- The inversion of a major interval is a minor interval, and vice versa; the inversion of a perfect interval is also perfect; the inversion of an augmented interval is a diminished interval, and vice versa; the inversion of a doubly augmented interval is a doubly diminished interval, and vice versa.