Всего найдено: 65

Здравствуйте! У Лопатина читаем: В названиях организаций … оба компонента первого сложного слова пишутся с прописной буквы … если название начинается с прилагательного, образованного от географического названия и пишущегося через дефис. (Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В. В. Лопатина. М., 2006. § 189, примеч. 1.) В этой связи вопрос про слово «Азиатско-т(Т)ихоокеанский». В ваших ответах в названиях организаций, начинающихся на это слово, второй компонент предлагается писать со строчной буквы («Азиатско-тихоокеанский парламентский форум», «Азиатско-тихоокеанское экономическое сотрудничество» — АТЭС, «Азиатско-тихоокеанский банк» и т.д.). Но не являются ли они образованными от названия Азиатско-Тихоокеанского региона, где оба слова пишутся с прописной, и потому подпадающими под вышеприведенный пункт правила, предписывающий начинать оба компонента с заглавной буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы рассуждаете совершенно верно. Однако мы не нашли в нашей базе ответа, в котором рекомендовалось бы писать Азиатско-тихоокеанский. Первые два названия из приведенных Вами упомянуты в вопросе № 258586, где рекомендация дана в соответствии с правилом.

Зарегистрированное название «Азиатско-Тихоокеанский Банк» нарушает правила русской орфографии. Видимо, последнее слово написано с прописной буквы по аналогии с названием на английском языке (Asian-Pacific Bank).

Жизнь (?) как океан – волны накатывают на берег и убегают назад. Нужна ли запятая и почему? Сравнение или устойчивое выражение?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая не нужна, поскольку как океан — это сказуемое.

Здравствуйте, скажите пожалуйста «все океаны», слово «океаны» пишется с большой буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Существительное океан в значении ‘водное пространство Земли’ нарицательное, оно пишется со строчной буквы.

Здравствуйте! Может ли имя собственное выражаться словосочетанием? Например, Тихий океан, Северное полушарие?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Имя собственное может выражаться словосочетанием. Но в Ваших примерах именами собственными являются только слова Тихий и Северное.

Здравствуйте. Подскажите пожалуйста верно ли выражение «сотрудничал в газетах «Тихоокеанская звезда», «Амурская правда»»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: сотрудничал с газетами, был сотрудником газет и т. д.

И все же жду ответа! Первые три вопроса отправлены 4, 11, 26 марта – ответа не было! Снова написали вам -15 апреля, от вас снова нет помощи. Сегодня еще одна попытка (но вопросов стало больше). 1. ИзменениЕ (или изменениЯ?) запасов продуктов в результате истечения срока годности, перевода на центральный склад, отправки заказчику и пр. 2. Ответ на вопрос может быть дан в иной(,) близкой по смыслу формулировке. Нужна ли выделенная запятая? Почему? 3. Строчная или прописная в слове «федеральный»? Провести мероприятие поручено федеральному государственному бюджетному учреждению «ВНИИзолоторедька»; Для создания федеральной государственной информационной системы (ФГИС) «Учет неопознанных объектов» следует приобрести новейшее оборудование. 4. Проверьте, пожалуйста, подпись под статьей – большая буква после двоеточия уместна? «Автор: Пресс-служба Минприроды России». 5. Подтвердите, что название институтов написано неправильно: ВНИИГеосистем (надо – ВНИИгеосистем), ВНИИОкеангеология (надо – ВНИИокеангеология)? 6. Проверьте, пожалуйста, пунктуацию: В Дальневосточном федеральном округе(,) в Магаданской области учтено шесть месторождений.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Корректно: Изменение запасов продуктов в результате истечения срока годности, перевода на центральный склад, отправки заказчику и пр.

2. Пунктуация зависит от смысла. Оборот без запятой в иной близкой по смыслу формулировке означает, что была дана близкая по смыслу формулировка, но есть и другая, тоже близкая по смыслу. Оборот с запятой содержит поясняющее определение и означает ‘в иной, то есть близкой по смыслу формулировке’.

3. Корректно написание слова федеральный со строчной буквы: Провести мероприятие поручено федеральному государственному бюджетному учреждению «ВНИИзолоторедька»; Для создания федеральной государственной информационной системы (ФГИС) «Учет неопознанных объектов» следует приобрести новейшее оборудование.

4. Лучше написать со строчной буквы: Автор: пресс-служба Минприроды России.

5. Приведем правило. В сложносокращенных словах смешанного типа, образованных из инициальных аббревиатур и усеченных основ, инициальная часть обычно пишется прописными буквами, а усеченная — строчными, напр.: НИИхиммаш, ЦНИИчермет, ГлавАПУ, КамАЗ; однако: ГУЛАГ, СИЗО (следственный изолятор), ГОСТ (государственный общероссийский стандарт), РОСТА (Российское телеграфное агентство), Днепрогэс. При этом составные названия, в которых за инициальной частью следует несокращенное слово (слова) в косвенном падеже, пишутся раздельно, напр.: НИИ газа, НИИ постоянного тока.

По правилу нужно писать: ВНИИгеосистем, ВНИИокеангеологии. Однако в уставах организаций могут быть закреплены варианты названий, не соответствующие правилам. Такие названия придется воспроизводить в юридических документах.

6. Корректно: В Дальневосточном федеральном округе, в Магаданской области, учтено шесть месторождений.

Простите, пожалуйста, опять пишу вам по поводу вопроса насчет Королевства Тонга (предыдущий вопрос № 300217). В словаре-справочнике Е.А. Левашова «Географические названия. Прилагательные, образованные от них. Названия жителей» в статье «Тонга» написано следующее: Тонга (гос-во), -и, ж., ед. Президиум Верховного Совета СССР направил телеграмму с поздравлениями и добрыми пожеланиями правительству и народу Тонги в связи с национальным праздником. Изв. 27 июня 1985. Тонга (о-ва — Тихий океан), неизм., мн. Беспорядки, которые прокатились по Меланезийским островам, нашли свой отзвук и на Тонга. ЗР, 1989. То есть, если слово «Тонга» встречается без «Королевства», то оно склоняется. Правильно ли это? Насколько авторитетен этот словарь?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Спорный вопрос. Фиксация Е.А. Левашовым склонения (и несклонения) слова Тонга есть, это означает, что наблюдается колебание грамматической нормы. Названный Вами словарь — авторитетный источник лингвистической информации.

Следует ли обособлять слово «конечно же» в предложении «Ну и конечно же желаю, чтобы деньги текли к вам рекой, любви было море, а счастья — океан!»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нужно обособление: Ну и, конечно же, желаю…

Здравствуйте. Скажите, пожалуйста, нужно ли тире в последней части этих предложений, а если нет, то почему? 1. Не прошло и нескольких дней, как океан покрылся льдом толщиной с ладонь, а земля снегом по щиколотку. 2. Если Игорь был лучшим из этих людей, то Света самой гордой. 3. Широков был более увлечён новыми философскими учениями, а Неверов историей. Заранее большое спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Тире можно поставить. Правило таково.

Тире ставится в неполном предложении, составляющем часть сложного предложения, когда пропущенный член (обычно сказуемое) восстанавливается из предыдущей части фразы и в месте пропуска делается пауза: Ермолай стрелял, как всегда, победоносно; я — довольно плохо; Мир освещается солнцем, а человек — знанием. При отсутствии паузы в месте пропуска члена предложения тире не ставится: Егорушка долго оглядывал его, а он Егорушку; Из нашей батареи только Соленый пойдет на барже, мы же со строевой частью.

Может ли прилагательное быть именем собственным? Например, Индийский (если океан). Или же в данном случае «Индийский» является собственным именем существительным? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В данном случае Индийский — часть собственного наименования.

Здравствуйте, уважаемые сотрудники «Грамоты»! Очень прошу дать ответ на вопрос! Нужна ли точка в конце следующего предложения (после кавычек): Участие в беседе по проблемному вопросу «Почему растения могут обитать в морях и океанах?»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В приведенном примере точка нужна.

Уважаемые сотрудники портала! Срочно-срочно нужен ответ! Что лучше поставить в предложении после слова «плиты» и словосочетания «складчатые пояса»? Назовите и покажите на карте крупнейшие литосферные плиты:/- Евраазиатскую, Индо-Австралийскую, Североамериканскую…; складчатые пояса:/- Тихоокеанский, Альпийско-Гимолайский…

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Назовите и покажите на карте крупнейшие литосферные плиты (Евро-Азиатскую, Индо-Австралийскую, Северо-Американскую), складчатые пояса (Тихоокеанский, Альпийско-Гималайский…).

Как правильно: вглубь океана или в глубь океана?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

«Объяснительный русский орфографический словарь-справочник» (Ин-т русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН; Е. В. Бешенкова и др. М., 2015) сообщает о сочетании (в)глубь следующее:

вглубь 1) пишется слитно как наречие от существительного (глубь), принадлежащего к закрытому ряду слов с пространственным или временным значением (распространиться вглубь и вширь, проблему не решили, а загнали вглубь); 2) закрепившееся слитное написание предлога (зверь забился вглубь норы).

◊ Не путать с сочетанием предлога и существительного, управляющего другим существительным, напр.: в глубь океана; в глубь веков; в глубь души; вникать в глубь, в суть проблемы; в глубь времён; вышел из распахнутых в глубь дома дверей. Поскольку в современном языке данный предлог находится еще в стадии формирования, то разница между сочетанием с предлогом вглубь дома и сочетанием существительных в глубь океана трудно уловима, поэтому в данных сочетаниях вполне возможно вариативное написание. (Статья приведена с некоторыми сокращениями.)

Правильно ли расставлены знаки препинания и возможно ли такое количество скобок в одном предложении? «В частности, результаты могут быть использованы для решения задач оперативной океанологии (прогноза развития опасных гидродинамических процессов, экстремальных волнения и течения), и предупреждения, связанных с ними, возможных аварийных ситуаций, для решения экологических задач (регистрация и прогноз распространения аварийных разливов нефтепродуктов), для наблюдения и предупреждения опасной метеорологической обстановки на море (смерчей, грозовой облачности) и многих других задач».

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: В частности, результаты могут быть использованы для решения задач оперативной океанологии (прогноза развития опасных гидродинамических процессов, экстремальных волнения и течения и предупреждения связанных с ними возможных аварийных ситуаций), экологических задач (регистрации и прогноза распространения аварийных разливов нефтепродуктов), для наблюдения и предупреждения опасной метеорологической обстановки на море (смерчей, грозовой облачности) и в других целях.

Здравствуйте, уважаемые специалисты! Пример: На Земле находится шесть частей суши — материков и пять океанов. В такой конструкции обязательно ли закрывать уточняющий оборот? Или можно по Розенталю оставить, как написано? Очень срочно. Заранее благодарю за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Закрывать оборот не обязательно.

Астрономы открывают во Вселенной всё новые и новые объекты: экзопланеты, звёзды, звёздные скопления, галактики, кометы, разнообразные детали рельефа на планетах и спутниках. Найденным объектам дают названия (их уже многие тысячи!), и все эти названия нужно записывать, причём единообразно, по правилам орфографии, чтобы не возникало проблем с поиском и идентификацией однотипных объектов.

Источник: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University.

‹

›

Названия, как известно из школьных учебников по русскому языку, пишутся с заглавной буквы. Но что делать, если в названии не одно слово, а несколько? Писать с заглавной буквы все слова или только первое (туманность Конская голова или туманность Конская Голова)? А если название начинается с непереводимого служебного слова (звезда Ван Маанена или ван Маанена)? В каком случае нужны кавычки (метеорит Челябинск или «Челябинск»)? Как написать название кометы, если её открыли двое или трое учёных — через дефис или через тире (комета Шумейкеров-Леви-9, Шумейкеров — Леви — 9, Шумейкеров — Леви 9)?

Правила, которые изучают в школе, ответов на эти вопросы не дают. Да и не только школьные, но и более полные, например правила, представленные в справочниках Д. Э. Розенталя. Орфографические правила, написанные в прошлом веке на доступном тогда языковом материале, нуждаются в расширении, уточнении, детализации, а может быть, и в исправлении. Этой работой занимаются в Институте русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. Сейчас орфографисты (так именуют лингвистов, которые изучают законы орфографии и фиксируют их в виде правил) ведут подготовку полного, актуального академического описания русской орфографии1.

Изучая космические карты и номенклатуры (классификации космических объектов с перечнями названий), научную и научно-популярную астрономическую литературу, орфографисты обнаружили множество ещё неизвестных лингвистике названий. Интереснейший объект для лингвистических исследований — Луна. За столетия астрономических наблюдений спутника нашей планеты накоплен огромный массив лунных названий.

Но прежде чем открывать лунные карты, познакомимся с тем, как создаются орфографические правила.

Вначале орфографисты исследуют обширный языковой материал в естественной среде обитания — в текстах. Наблюдение за письменной речью позволяет увидеть, какие тенденции написания складываются в языке, какие языковые явления отражаются в выборе пишущих и какие неязыковые факторы влияют на этот выбор. Все явления отдельной области письма (например, орфографии астрономических названий) орфографисты рассматривают с точки зрения их соответствия общей системе письма, полученные данные соотносят с существующими правилами и рекомендациями нормативных словарей и главное — оценивают разные способы написания в коммуникации: насколько они привычны, удобны, значимы для пишущих и читающих.

Только после всестороннего исследования принимаются решения о норме для неустоявшихся, колеблющихся написаний и — при необходимости — об изменении нормы, зафиксированной ранее.

Завершается работа поиском наиболее точных, логически непротиворечивых, полных и лаконичных формулировок правила. При этом тщательно подбираются примеры, которые должны отразить всё разнообразие языкового материала, попадающего в сферу действия правила, и пишутся примечания и комментарии, которые обогащают правила различными уточнениями, разъяснениями, фактами истории данной области письма и отдельных слов.

Теперь посмотрим, какие названия встречаются на картах Луны.

Собственные имена присвоены различным деталям лунной поверхности. По каталогу «Номенклатурный ряд названий лунного рельефа» Государственного астрономического института им. П. К. Штернберга (МГУ)2 это — кратеры, цепочки кратеров, борозды, гряды, пики, горы, равнины, долины, сбросы, места прилунения, мысы, океан, моря, заливы, озёра, болота. В каталоге все термины и названия при них написаны полностью заглавными буквами. А как их нужно писать в тексте? Как правильно: Альпийская Долина или Альпийская долина, Горы Архимеда или горы Архимеда, Океан Бурь или океан Бурь, Море Спокойствия или море Спокойствия? Сразу отметим, что в текстах, отредактированных и вычитанных, встречаются написания терминов и с заглавной буквы, и со строчной. Почему возникают разные варианты и какие рекомендации нужно закрепить в академических правилах орфографии?

В русском письме сложился принцип: со строчной буквы начинаются родовые слова (то есть слова, указывающие на тип названного объекта), с заглавной — названия, которые выделяют предмет из ряда однородных. Этот принцип удобен, так как позволяет различать в тексте собственно название и родовое слово. Вспомним сочетания: город Царское Село, улицы Кузнецкий Мост и Земляной Вал. Слова город, улица указывают на тип объекта, слова Село, Мост, Вал входят в название и используются в нём не в прямом значении (сравните с названиями деревень и сёл: Белое Озеро, Большая Речка, Гнилое Болото, Пруды). Правила написания географических названий, основанные на этом принципе, были закреплены академиком Яковом Карловичем Гротом3 и поддерживаются современным письмом.

Вполне логично расширить действие «географического» правила на внеземные названия. Но применив это правило к названиям лунных объектов, мы увидим, что одни географические термины используются в лунной номенклатуре в соответствии с их значением, а для других такого соответствия нет. Ко второй группе относятся термины океан, море, залив, болото, озеро. Эти «водные» термины называют объекты совсем не водные, поэтому осмысляются как части названия и записываются с заглавной буквы.

В текстах о Луне написание всех терминов — и водных, и неводных — колеблется, однако чаще с заглавной буквы пишут именно водные термины, например: Море Москвы, Море Мечты, Залив Лунника, Залив Согласия, Озеро Справедливости, Болото Эпидемий. Написание их со строчной буквы встречается реже, а вот для остальных, неводных названий — всё наоборот.

Существенно, что в астрономической науке у водных терминов сформировались новые, специальные значения, относящиеся к лунному ландшафту. Например, в книге «Путешествия к Луне»4 находим такие определения: море — тёмная пониженная область; океан — обширная тёмная пониженная область; залив — часть моря, вдающаяся в материк; озеро — тёмная пониженная область меньших размеров; болото — пониженная область, менее тёмная, чем море. Новые, специальные значения как раз и являются основанием для написания терминов со строчной буквы. Теперь понятны лингвистические причины разнонаписаний.

Выявив проблему, оставим её на время и, как требует логика орфографического исследования, обратимся к истории лунной номенклатуры.

Рассмотреть детали рельефа Луны впервые удалось в ХVII веке благодаря изобретению телескопа. Тогда же и начали составлять лунные карты. Тёмные пятна, видимые с Земли и невооружённым глазом, наблюдатели приняли за водные пространства, и итальянский астроном Джованни Баттиста Риччоли дал им названия по предполагаемому влиянию фаз Луны на погоду Земли, например: Mare Sеrenitatis (море Ясности), Mare Nubium (море Облаков), Mare Vaporum (море Паров).

Трудно установить, когда эти названия начали осваиваться русским языком, но письменные источники свидетельствуют, что к середине ХVIII века они уже были известны в России.

В ХIХ веке стало очевидно, что никаких морей и озёр на Луне нет. Но водные термины продолжали использоваться и должны были восприниматься уже как части условного названия.

В «Лекциях по популярной астрономии» Семёна Ильича Зеленого 1850 года утверждается, что лунные моря — «моря сухiя», и написание термина море неустойчиво:

«…странныя, и теперь употребляемыя, названiя — море Кризисовъ, море Плодородiя, море Влажности, Море Ясной погоды, море Облаковъ, и проч. Море Кризисовъ и море Влажности лежатъ отдѣльно и имѣютъ края явственно очертанныя, прочiя большiя моря соединяются съ другими ближайшими на подобiе океанов нашей земли»5 (курсив мой. — Прим. Е. А.).

А в сочинении Германа Йозефа Клейна, изданном в 1900 году, уже орфографически чётко разграничены термины, обозначающие тип объекта и не обозначающие его: «Не слѣдуетъ однако думать, что эти названiя имѣют прямое отношенiе къ характеру обозначенныхъ ими мѣстностей, что в Заливѣ Волненiй часто бушуютъ волны, а надъ Моремъ Дождей постоянно проносятся ливни. В дѣйствительности, всю поверхность луны можно было бы назвать Страной Ясности, такъ какъ надъ ней нѣтъ ни одного облачка. Название ”море” нельзя принимать въ истинномъ смыслѣ этого слова: наблюдатели, слѣдовавшiе за Гевелиемъ, пользуясь болѣе совершенными инструментами, доказали, что на лунѣ нѣтъ морскихъ бассейновъ, и что сѣрыя пятна представляютъ ровныя, болѣе низменныя пространства, на которыхъ расположены холмы, кольцеобразныя горы и кратеры»6. Сравните с другими названиями из разных частей книги: «равнина Альфонса», «валъ Магинуса», «бороздка Гигинуса», «горы Коперника и Аристарха», «гора ”Лагиръ”», но «Болото Сновиденiй»7.

В ХХ веке написание водных терминов с заглавной буквы при названиях Луны было закреплено в орфографических правилах. В наиболее полном справочнике «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» под редакцией Владимира Владимировича Лопатина, вышедшем в самом начале нашего века, читаем: «Так же [по основному правилу] пишутся названия местностей на космических телах, напр.: Болото Гнили, Залив Радуги, Море Дождей, Океан Бурь (на Луне), где слова болото, залив и т. д. употребляются не в своём обычном значении»8. Орфографисты последовали за традицией и практикой письма, в правиле не учтено новое значение водных терминов, появившееся в языке науки.

Но если существуют лингвистические основания для написания водных терминов и с заглавной, и со строчной буквы, то почему в современных текстах заглавная буква появляется у терминов, которые используются на Луне в их прямом значении: равнина, долина, гора, борозда и подобных? На этот вопрос тоже находится ответ.

На написание неводных терминов влияют, во-первых, соседство в тексте с водными терминами, а во-вторых (и этот фактор представляется более сильным), орфография международных названий. Имена астрономических объектов официально утверждаются Международным астрономическим союзом (МАС). Они записываются латиницей, и для них установлены свои правила орфографии. По этим правилам любые родовые слова (термины) пишутся с заглавной буквы. При передаче названий по-русски астрономы часто ориентируются на написания, принятые МАС, а не на правила русской орфографии. Но это приводит к утрате смыслоразличительной функции прописных и строчных букв, сбивает с толку русскоязычного читателя, воспринимающего слова гора, озеро как слова-понятия, а Гора, Озеро как названия.

Сложившиеся в русском письме принципы написания, имеющие важное смысловое значение, нужно поддерживать — тут у орфографистов сомнений нет. Соответственно, термины, обозначающие части лунной «суши», нужно писать только со строчной буквы (Альпийская долина, горы Архимеда, горы Рифей, кратер Эндимион). Но стоит ли менять орфографическую рекомендацию для водных терминов и предлагать писать их со строчной буквы, учитывая их новое, специальное значение? Этот вопрос лингвистам ещё предстоит решить, разумеется, совместно с астрономами.

Комментарии к статье

1 Академическое описание орфографии возможно в двух формах — словаря и свода правил. Орфографисты, постепенно изучая одну область письма за другой на всём доступном сейчас языковом материале, описывают законы орфографии в виде правил, стремясь к абсолютной точности, полноте, логической непротиворечивости. Также они постоянно пополняют академический «Русский орфографический словарь» (в ряду прочего и астрономическими названиями) и его электронное воплощение — ресурс «Академос» (https://orfo.ruslang.ru).

2 Номенклатурный ряд названий лунного рельефа: каталог / С. Г. Пугачёва, Ж. Ф. Родионова и др.; Государственный астрономический институт им. П. К. Штернберга, МГУ (http: //selena.sai.msu.ru).

3 Спорные вопросы русского правописания от Петра Великого доныне / Я. К. Грот; под ред. Я. К. Грота. — 5-е изд. — М.: URSS, 2010. — С. 307.

4 Путешествия к Луне: [наблюдения, экспедиции, исследования, открытия] / [А. Е. Марков и др.]; ред.-сост. В. Г. Сурдин. — М.: Физматлит, 2009.

5 Лекции по популярной астрономии, читанные публично, с высочайшего разрешения в Морском кадетском корпусе капитан-лейтенантом С. Зеленым с 25 ноября 1843 по 16 марта 1844. — 2-е изд., доп. новейшими открытиями. — Санкт-Петербург: тип. Мор. кадет. корпуса, 1850. — С. 224.

6 Астрономические вечера: С 4-го нем. изд., перераб. самим авт.: Доп. из Араго, Барнарда, Болля… и др. астрономов: Доп. о послед. открытиях, напис. проф. С.-Петерб. ун-та С. П. Глазенапом: Доп. об идеях Ф. Ал. Бредихина, напис. астрономом-наблюдателем Юрьев. ун-та К. Д. Покровским / Клейн. — 3-е изд. рус. пер. — Санкт-Петербург: Знание, 1900. — С. 236.

7 Там же, с. 242—257.

8 Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник: одобрено Орфографической комиссией РАН / отв. ред. В. В. Лопатин; Рос. акад. наук, Отд. историко-филол. наук, Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: Эксмо, 2006 (и след.). — § 178.

Географические наименования пишутся с прописной буквы.

- Так с большой быквы пишутся собственные географические наименования. Например:

Европа, Минск, Волга

В географических наименованиях, состоящих из нескольких слов, все слова пишутся с прописной буквы. Но родовые, то есть указывающие на вид географического объекта, названия, такие как река, океан, остров, мыс, город пишутся со строчной буквы. Например:

Северный Ледовитый океан, пролив Карские Ворота, город Белая Церковь, остров Святой Елены и т. д.

- Географические наименования могут представлять собой обе части географических названий, пишущихся через дефис. Например:

Петропавловск-Камчатский, Восточно-Европейская равнина, Нью-Йорк, Покровское-Глебово, Лас-Вегас, Сан-Франциско.

Служебные слова в середине географических названий пишутся со строчной буквы и соединяются двумя дефисами. Например:

Николаевск-на-Амуре, Франкфурт-на-Майне.

- С большой буквы пишутся полные и сокращенные , официальные и неофициальные названия государств. Например:

Республика Беларусь, Федеративная Республика Германия, Беларусь, Германия.

Неофициальные названия территорий, областей, местностей также пишутся с прописной буквы. Например:

Гомельщина, Подмосковье, Ставрополье

- Названия улиц, площадей, парков, скверов, заповедников также пишутся с большой буквы. Обычно такие названия можно встретить на картах городов и стран. Например:

улица Есенинская, площадь Победы, Михайловский парк

В составных названиях улиц, площадей, парков, скверов все слова (кроме слов улица, площадь и подобных) пишутся с прописной буквы. Например:

улица Новый Арбат, улица Кузнецкий Мост, площадь Никитские Ворота

В перечисленных примерах слова ~мост и ворота пишутся с большой буквы, так как они являются частью названия и без них наименование теряет свій однозначный смысл, то есть, например, нельзя вместо ~“площадь Никитские Ворота” ~ сказать “Прощадь Никитские”. Слова же ~ улица и площадь ~ можно легко убрать без потери смысла, поэтому они при названиях пишутся с маленькой буквы.

Стоит обратить внимание, что слова юг, север, запад, восток являются нарицательными и пишутся со строчной буквы, когда они обозначают стороны света (то есть когда мы ассоциируем их с направлением). Но если они употребляются взамен территориальных названий, то пишутся с прописной буквы. Например:

Туристы двинулись на север. Солнце восходит на востоке.

В данных примерах слова “север” и “восток” являются нарицательными и не входят в часть территориальных названий, поэтому они пишутся со строчной буквы.

Крайний Север, народы Востока

В данных примерах слова “север” и “восток” определяют не стороны света, а конкретные географические регионы, поэтому они являются наименованиями и пишутся с прописной буквы.

Следует запомнить правила правописания астрономических названий

- Индивидуальные астрономические названия, в том числе состоящие из нескольких слов, пишутся с прописной буквы. Например:

Венера, Юпитер, Млечный Путь, Большая Медведица

- Родовые астрономические названия пишутся со строчной буквы. Например:

звезда, созвездие, туманность, планета, комета

- Слова солнце,~ земля, ~луна пишутся с прописной буквы, если обозначают названия небесных тел (или планет). Часто в таких случаях употребляются или могут употребляться слова “планета”, “небесное тело” и подобные. Например:

Луна — спутник Земли.

Расстояние от Земли до Солнца — 150 миллионов километров.

Всем известно, что планета Земля имеет один спутник.

Во всех остальных случаях эти слова пишутся со строчной буквы. Например:

восход солнца, круглая луна, плодородная земля

Стоит обратить внимание, что хоть при восходе солнца или взгляде на круглую луну мы фактически видим планеты или небесные тела, но в данном случае ведём речь не о них самих, а о событиях и явлениях, с ними связанных. В таких случаях мы обычно не употребляем слова “планета” или “небесное тело”.

Повторим

С прописной буквы пишутся:

- Собственные географические наименования. В географических наименованиях, состоящих из нескольких слов, все слова пишутся с прописной буквы (родовые названия река, океан, остров, мыс, город пишутся со строчной).

- С прописной буквы пишутся Обе части географических названий, пишущихся через дефис. Служебные слова в середине географических названий пишутся со строчной буквы и соединяются двумя дефисами

- С прописной буквы пишутся Официальные и неофициальные названия государств.

- С прописной буквы пишутся Неофициальные названия территорий, областей, местностей.

- С прописной буквы пишутся Названия улиц, площадей, парков, скверов.

- С прописной буквы пишутся Все слова в составных названиях улиц, площадей, парков, скверов (кроме слов улица, площадь и подобных).

Слова юг, север, запад, восток являются нарицательными и пишутся со строчной буквы. Но если они употребляются взамен территориальных названий, то пишутся с прописной буквы.

Следует запомнить правила правописания астрономических названий

- Индивидуальные астрономические названия, в том числе состоящие из нескольких слов, пишутся с прописной буквы.

- Родовые астрономические названия пишутся со строчной буквы.

- Слова солнце,~ земля, ~луна пишутся с прописной буквы, если обозначают названия небесных тел (планет). Во всех остальных случаях эти слова пишутся со строчной буквы.

Содержание

- Тихий океан

- Атлантический океан

- Индийский океан

- Южный океан

- Северный Ледовитый океан

- Видео

- Вопрос – Ответ (FAQ)

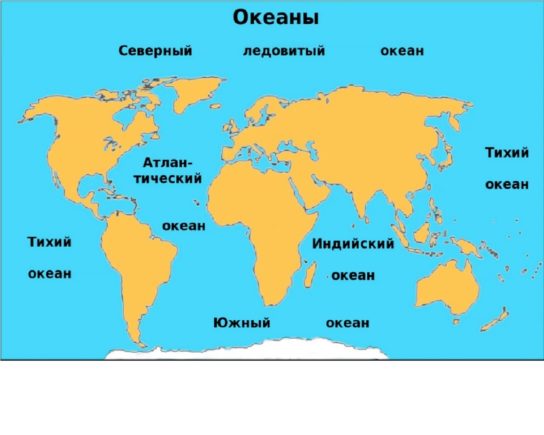

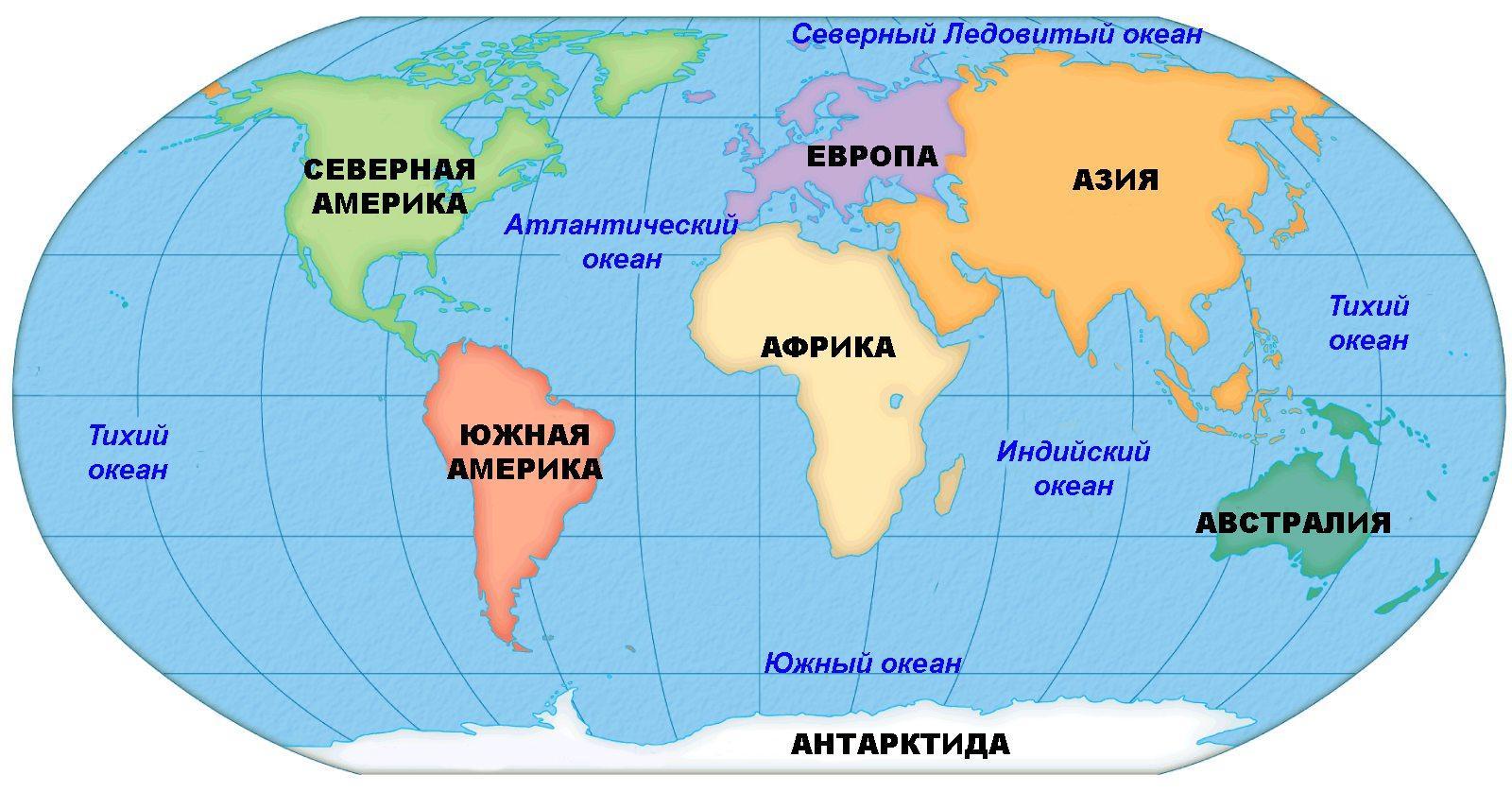

Океан представляет собой крупнейший объект гидросферы и является частью Мирового океана, который покрывает около 71% поверхности нашей планеты. Океаны омывают берега материков, обладают системой циркуляции вод и имеют другие специфические особенности. Океаны мира находятся в постоянном взаимодействии со всеми оболочками Земли.

В некоторых источниках указано, что Мировой океан подразделяется на 4 океана, однако в 2000 году Международной гидрографической организацией был выделен пятый – Южный океан. В этой статье представлен список всех 5 океанов планеты Земля по порядку – от самого большого по площади к наименьшему, с названием, расположением на карте и основными характеристиками.

Тихий океан

Читайте также: Какие материки и страны омывает Тихий океан?

Тихий океан является одним из пяти океанов мира. Это самый большой океан на нашей планете, с площадью 165,25 млн. км². Он простирается от Северного Ледовитого океана на севере до Южного океана на юге, и омывает такие части света, как Азия, Австралия, Северная Америка и Южная Америка, а также ряд тихоокеанских островов.

Из-за большого размера Тихий океан имеет уникальную и разнообразную топографию. Он также играет важную роль в формировании погодных условий во всем мире и современной экономике.

Океаническое дно постоянно изменяется в процессе движения и субдукции тектонических плит. В настоящее время самому старому из известных районов Тихого океана насчитывается около 180 миллионов лет.

С точки зрения геологии, область, окружающая Тихий океан, иногда называется Тихоокеанским вулканическим огненным кольцом. Регион имеет это название, потому что это самая большая в мире область вулканизма и землетрясений. Тихоокеанский регион подвержен бурной геологической деятельности, потому что большая часть его дна находится в зонах субдукции, где границы одних тектонических плит пододвигаются под другие после столкновения. Существуют также некоторые области горячих точек, где магма из мантии Земли вытесняется через земную кору, создавая подводные вулканы, которые в конечном итоге могут образовывать острова и подводные горы.

Тихий океан имеет разнообразный рельеф дна, состоящий из океанических хребтов и глубоководных желобов, которые образовались в горячих точках под поверхностью. Рельеф океана значительно отличается от крупных континентов и островов. Самая глубокая точка Тихого океана называется “Бездной Челленджера”, она расположена в Марианской впадине, на глубине почти 11 тыс. метров. Самым большим островом Тихого океана является Новая Гвинея.

Климат океана сильно варьируется в зависимости от широты, наличия суши и типов воздушных масс, движущихся над его водам. Температура поверхности океана также играет роль в климате, поскольку она влияет на доступность влаги в разных регионах. В окрестностях экватора климат тропический, влажный и теплый в течение большей части года. Крайне северная часть Тихого океана и далеко южная часть – более умеренные, имеют большие сезонные различия в погодных условиях. Кроме того, в некоторых регионах преобладают сезонные пассаты, которые влияют на климат. В Тихом океане также формируются тропические циклоны и тайфуны.

Морские экосистемы Тихого океана практически такие же, как и в других океанах Земли, за исключением местных температур и солености воды. В пелагической зоне океана обитают морские животные, такие как рыбы, морские млекопитающие и планктон. На дне живут беспозвоночные организмы и падальщики. Местообитания коралловых рифов можно найти в солнечных мелководных районах океана вблизи берега. Тихий океан – это среда, в которой обитает наибольшее разнообразие живых организмов на планете.

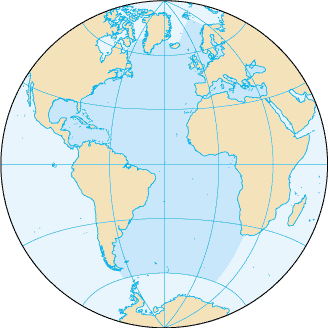

Атлантический океан

Читайте также: Какие материки и страны омывает Атлантический океан?

Атлантический океан является вторым по величине океаном на Земле с общей площадью (с учетом прилегающих морей) 106,46 млн. км². Он занимает около 22% от площади поверхности планеты. Океан имеет удлиненную S-образную форму и простирается между Северной и Южной Америкой на западе, а также Европой, и Африкой – на востоке. На севере он соединяется с Северным Ледовитым океаном, с Тихим океаном на юго-западе, с Индийским океаном на юго-востоке и с Южным океаном на юге. Средняя глубина Атлантического океана составляет 3 736м, а самая глубокая точка расположена в океаническом жёлобе Пуэрто-Рико, на глубине 8 742 м. Атлантический океан имеет наибольшую соленость воды среди всех океанов мира.

Его климат характеризуется теплой или прохладной водой, которая циркулирует в разных течениях. Глубина воды и ветры также оказывают значительное влияние на погодные условия на поверхности океана. Известно, что сильные атлантические ураганы развиваются у побережья Кабо-Верде в Африке, и с августа по ноябрь направляются к Карибскому морю.

Время, когда суперконтинент Пангея распался, около 130 миллионов лет назад, стал началом формирования Атлантического океана. Геологи определили, что он является вторым самым молодым из пяти океанов мира. Этот океан сыграл очень важную роль в соединении Старого Света с недавно исследованной Америкой с конца 15 века.

Главная особенность дна Атлантического океана – подводный горный хребет, называемый Срединно-Атлантическим хребтом, который простирается от Исландии на севере до приблизительно 58° ю. ш. и имеет максимальную ширину около 1600 км. Глубина воды над хребтом в большинстве мест составляет менее 2700 метров, а несколько горных вершин хребта поднимаются над водой, образуя острова.

Атлантический океан впадает в Тихий океан, однако их среды обитания не всегда одинаковые из-за температуры воды, океанических течений, солнечного света, питательных веществ, солености и т.д. В Атлантическом океане есть прибрежные и открытые океанические места обитания. Его прибрежные экосистемы расположены вдоль береговых линий и простираются до континентальных шельфов. Морская флора обычно сосредоточена в верхних слоях вод океана, а ближе к берегам располагаются коралловые рифы, мангровые заросли, леса водорослей и морские травы.

Атлантический океан имеет важное современное значение. Строительство Панамского канала, расположенного в Центральной Америке, позволило крупным судам проходить по водным путям, из Азии через Тихий океан к восточному побережью Северной и Южной Америки через Атлантический океан. Это привело к оживлению торговли между Европой, Азией, Южной Америкой и Северной Америкой. Кроме того, на дне Атлантического океана есть месторождения газа, нефти и драгоценных камней.

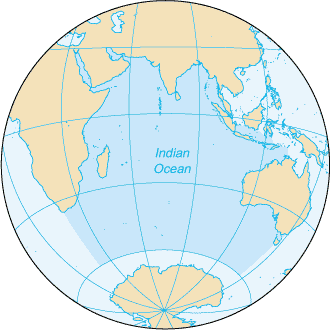

Индийский океан

Читайте также: Какие материки и страны омывает Индийский океан?

Индийский океан является третьим по величине океаном планеты и имеет площадь 70,56 млн. км². Он расположен между Африкой, Азией, Австралией и Южным океаном. Индийский океан имеет среднюю глубину 3 963 м, а Зондский жёлоб является самой глубокой впадиной, с максимальной глубиной 7 258 м. Индийский океан занимает около 20% площади Мирового океана.

Образование этого океана является следствием распада суперконтинента Гондваны, начавшегося около 180 миллионов лет назад. 36 миллионов лет назад Индийский океан принял свою нынешнюю конфигурацию. Хотя он впервые открылся около 140 миллионов лет назад, почти все бассейны Индийского океана имеют возраст менее 80 миллионов лет.

В Северном полушарии он не имеет выхода к морю и не простирается до арктических вод. У него меньше островов и более узкие континентальные шельфы по сравнению с Тихим и Атлантическим океанами. Ниже поверхностных слоев, особенно на севере, вода в океане чрезвычайно низко насыщенная кислородом.

Климат Индийского океана значительно варьируется с севера на юг. Например, муссоны доминируют в северной части, над экватором. С октября по апрель наблюдаются сильные северо-восточные ветра, в то время как с мая по октябрь – южные и западные. Индийский океан также имеет самую теплую погоду из всех пяти океанов мира.

В океанических глубинах содержится около 40% морских запасов нефти в мире, и в настоящее время семь стран добывают полезные ископаемые из этого океана.

Сейшелы – архипелаг в Индийском океане, состоящий из 115 островов, и большинство из них – гранитные острова и коралловые острова. На гранитных островах большая часть видов являются эндемичными, а коралловые острова имеют экосистему коралловых рифов, где биологическое разнообразие морской жизни наибольшее. На территории Индийского океана есть островная фауна, которая включает морских черепах, морских птиц и многих других экзотических животных. Большая часть морской жизни в Индийском океане является эндемичной.

Вся морская экосистема Индийского океана сталкивается с сокращением численности видов, поскольку температура воды продолжают расти, что в свою очередь, приводит к 20%-ному снижению фитопланктона, от которого сильно зависит морская пищевая цепь.

Южный океан

В 2000 году Международная гидрографическая организация выделила пятый, самый молодой океан мира – Южный океан – из южных районов Атлантического, Индийского и Тихого океанов. Новый Южный океан полностью окружает Антарктиду и простирается от ее побережья на север до 60 ° ю. ш. Южный океан на сегодняшний день является четвертым по величине из пяти океанов мира, превышая по площади только Северный Ледовитый океан.

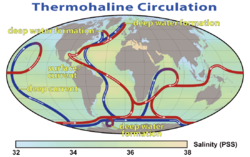

В последние годы большое количество океанографических исследований касалось океанических течений, сначала из-за Эль-Ниньо, а затем из-за более широкого интереса к глобальному потеплению. Одно из исследований определило, что течения вблизи Антарктиды изолируют Южный океан как отдельную экосистему, поэтому его выделили в отдельный, пятый океан.

Площадь Южного океана составляет приблизительно 20,3 млн. км². Самая глубокая точка имеет глубину 7 235 метров и она располагается в Южно-Сандвичевом жёлобе.

Температура воды в Южном океане варьируется от -2° C до +10° C. В нем также находится крупнейшее и самое мощное холодное поверхностное течение на Земле – антарктическое циркумполярное течение, которое движется на восток и в 100 раз превышает поток всех мировых рек.

Несмотря на выделение этого нового океана, вполне вероятно, что дискуссия о количестве океанов будет продолжаться и в будущем. В конце концов, есть только один «Мировой океан», поскольку все 5 (или 4) океана на нашей планете взаимосвязаны друг с другом.

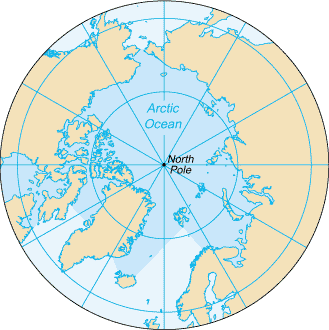

Северный Ледовитый океан

Читайте также: Какие материки и страны омывает Северный Ледовитый океан?

Северный Ледовитый океан является самым маленьким из пяти океанов мира и имеет площадь 14,06 млн. км². Его средняя глубина 1205 м, а самая глубокая точка находится в подводной котловине Нансена, на глубине 4665 м. Северный Ледовитый океан расположен между Европой, Азией и Северной Америкой. Кроме того, большая часть его вод находится к северу от полярного круга. Географический Северный полюс находится в центре Северного Ледовитого океана.

В то время как Южный полюс расположен на континенте, Северный полюс покрыт водой. В течение большей части года Северный Ледовитый океан почти полностью покрыт дрейфующим полярным льдом, который имеет толщину около трех метров. Этот ледник обычно тает в летние месяцы, но лишь частично.

Из-за небольшого размера многие океанографы не считают его океаном. Вместо этого некоторые ученые предпологают, что это море, которое в основном огорожено континентами. Другие считают, что это частично закрытый прибрежный водоем Атлантического океана. Эти теории не широко распространены, и международная гидрографическая организация рассматривает Северный Ледовитый океан как один из пяти океанов мира.

Северный Ледовитый океан имеет самую низкую соленость воды среди всех океанов Земли поскольку низкая скорость испарения и пресная вода, поступающая из ручьев и рек, которые питают океан, разбавляя концентрацию солей в воде.

Полярный климат доминирует в этом океане. Следовательно зимы демонстрируют относительно стабильную погоду с низкими температурами. Наиболее известными характеристиками этого климата являются полярные ночи и полярные дни.

Считается, что в Северном Ледовитом океане может находиться около 25% от общего объема запасов природного газа и нефти на нашей планете. Геологи также установили, что здесь есть значительные месторождения золота и других полезных ископаемых. Обилие нескольких видов китов, рыб и тюленей также делают регион привлекательным для рыбной промышленности.

В Северном Ледовитом океане есть несколько мест обитания животных, включая находящихся под угрозой исчезновения млекопитающих и рыб. Уязвимая экосистема региона является одним из факторов, который делают фауну столь чувствительной к климатическим изменениям. Некоторые из этих видов эндемичные и незаменимые. Летние месяца приносят изобилие фитопланктона, который, в свою очередь, питает зоопланктон, находящийся в основании пищевой цепи, которая в конечном итоге заканчивается крупными наземными и морскими млекопитающими.

Последние разработки в области технологий позволяют ученым изучать глубины океанов мира новыми способами. Эти исследования необходимы, чтобы помочь ученым изучить и, возможно, предотвратить катастрофические последствия изменения климата в этих районах, а также обнаружить новые виды живых организмов.

Видео

Вопрос – Ответ (FAQ)

Какой океан самый большой, а какой самый маленький по площади?

Какой океан самый глубокий, а какой самый мелкий?

Какой океан самый холодный?

Какой океан самый теплый на планете?

Гугломаг

Спрашивай! Не стесняйся!

Задать вопрос

Не все нашли? Используйте поиск по сайту

Все категории

- Фотография и видеосъемка

- Знания

- Другое

- Гороскопы, магия, гадания

- Общество и политика

- Образование

- Путешествия и туризм

- Искусство и культура

- Города и страны

- Строительство и ремонт

- Работа и карьера

- Спорт

- Стиль и красота

- Юридическая консультация

- Компьютеры и интернет

- Товары и услуги

- Темы для взрослых

- Семья и дом

- Животные и растения

- Еда и кулинария

- Здоровье и медицина

- Авто и мото

- Бизнес и финансы

- Философия, непознанное

- Досуг и развлечения

- Знакомства, любовь, отношения

- Наука и техника

0

Названия водоёмов: озёр, океанов, пишутся с большой или маленькой буквы?

Названия водоёмов с какой буквы пишутся с большой или маленькой буквы?

Как пишутся названия водоёмов, с заглавной буквы или строчной, с большой или маленькой?

4 ответа:

1

0

В соответствии с правилами грамматики русского языка имена собственные пишутся с прописной (заглавной, большой) буквы, независимо от того, какое место в предложении они занимают.

К именам собственным относятся:

географичесеие названия (озеро Байкал, материк Евразия);

имена, фамилии, отчества людей, а также их псевдонимы, клички, позывные и т. п. (конструктор Михаил Калашников, певица Валерия);

клички животных (лабрадор Кони);

названия произведений искусства и культуры (храм Казанский собор, симфония Лунная соната);

исторических событий и эпох (Великая Отечественная война, эпоха Возрождения);

сорта састений (роза Фламинго).

0

0

С большой так как у них есть имя собственное например:Байкал или Тихий Океан так пишится

0

0

Конечно же названия водоёмов: озёр, океанов пишутся с большой заглавной буквы. Например, Индийский океан, река Енисей. С большой буквы пишутся названия других географических объектов (города, страны, деревни, сёла, улицы), а также имена, отчества, фамилии людей, клички животных.

0

0

Слово, обозначающее географический объект — река, озеро, море, океан,пишется с маленькой буквы. А само название — Тихий океан, озеро Селигер, река Волга, пишется уже с большой буквы. Это как имя человека, которое всегда пишется с заглавной.

Читайте также

Прилагательное»Непод<wbr />ходящий» пишется слитно потому, что к слову мы можем подобрать синоним без частицы «НЕ».Это синоним- малоподходящий.Приме<wbr />р предложения:»Когда тебе за шестьдесят — это неподходящий возраст, чтобы заводить детей», «Это совершенно неподходящий тебе по размеру костюм».

Слово приоритет обозначает «преимущество, главенство чего-либо». В русской лексике это слово является заимствованным из немецкого языка. А следы происхождения этого слова, если поинтересоваться этим, приведут нас в латинский язык, в котором слово «приор» значит «первый». Вот этим словом можно проверить безударный гласный «о» в слове «приоритет».

Написание буквы «и» в начале слова «приоритет» следует запомнить, как и в этих словарных словах: прилежный, пример, привет (при- не является в них приставкой), примитивный, привилегия, приватный.

В случае затруднения в написании слов с начальным при- заглядываем в орфографический словарь.

Разница между этими двумя словами и написаниями в том, что:

Можно за раз увидеть сто зараз. Можно и зараз увидеть за сто раз. Но в этих предложениях мы видим не только зараз, но и следующее:

«За раз» — раздельное написание подсказывает нам о том, что сказано «за один раз». Это и имеется в виду. Вставка слова «один» является вовсе не искусственной. Она как бы дополняет сокращённое высказывание до полного.

«Зараз» — это одна из грамматических форм имени существительного «зараза»: «множество зараз», «нет этих зараз» и так далее. Пишется слитно.

_

Как известно, слово «зараза» может появиться в предложении не только в значении «инфекция», но и как ругательство («человек, который, подобно инфекции, бесполезен, докучлив и так далее»). В этом смысле множественное число («заразы») становится естественным, у него имеется родительный падеж, который мы и не должны путать с «за раз».

Это из категории грамматики русского языка.

Слова, которые начинающиеся на «пол-«, могут писаться и слитно, и через дефис, и раздельно.

А вот если слова, которые начинаются на «полу-» всегда пишется слитно.

правильно будет «полудУрок«.

А ещё можно сказать и «полудурАк» — что означает наполовину дурак. А чтоб не обидеть собеседника — можно сказать и «полуумный»

Начнем с того, что перед нами мощный — прилагательное как часть речи, образовалось оно, как и многие другие прилагательные, от существительного мощь. Существительное женского рода, с мягким знаком на конце, который при написании прилагательного не сохраняется.

Нас интересует правописание с не. Как известно, у прилагательных оно зависит от наличия противопоставления с союзом а, возможности подобрать синонимы, в которых бы отсутствовало не-), наличия сочетаний совсем не …, либо ничуть не …., либо вовсе не …, либо далеко не ….

Совсем немощный (слабенький, болезный) старичок.

Этот взрыв был не мощный, а слабый.

Взрыв был совсем не мощный.

Водная оболочка планеты Земля, окружающая все материки, а также острова покрывает около 71% всей поверхности планеты. Существует условное разделение мирового океана на части. Сегодня Мировой океан разделён на 5 океанов. В Международной географической организации к четырём известным океанам Тихому, Индийскому, Северному Ледовитому и Атлантическому, в 2000 году было решено выделить и добавить Южный океан.

Тихий океан

Тихий океан расстилается в западном направлении между двумя материками Австралией и Евразией, в сторону востока между Северной и Южной Америкой, а на юге омывает Антарктиду.

Своё название океан получил в то время, когда Ф. Магеллан совершал кругосветное путешествие и пересекал Тихий океан. В этот период была прекрасная погода, не было ветра, и водная гладь была спокойной. И путешественник назвал его «Тихим».

Тихий океан является самым старшим по возрасту, наибольшим по площади, а также по глубине. Его площадь равна 178 684 000 квадратных километров, глубина имеет среднее значение около 4000 метров. Через воды Тихого океана в районе 180-го меридиана есть линия, которая соответствует перемене даты.

Тихий океан ещё называют «Великим». Ведь он занимает треть нашей планеты. По форме Тихий океан напоминает овал, а в экваториальной части он является наиболее широким.

Область, которую окружает Тихий океан, уникальна и разнообразна по своей топографии. Геологи называют область, окружающую Тихий океан ― вулканическое огненное кольцо. Она получила такое название, потому что в ней происходят постоянные землетрясения и извержение вулканов. На дне океана много точек, где извергаются подводные вулканы, за счёт магмы, вытесняемой из мантии Земли. Дно Тихого океана состоит из хребтов и жёлобов, которые находятся на большой глубине.

Климатические условия зависят от того, на какой широте находятся воды океана, какой рядом материк и тип воздушных масс. В районе экватора преобладает тропический климат. Там большую часть года тепло и влажно.

Видео про Великий Тихий океан

В северной и южной частях климатические условия ближе к умеренным. Есть районы, в которых постоянно дуют ветры (пассаты), влияющие на климат. Также Тихий океан является местом образования тайфунов и тропических циклонов. Но вода в нём прозрачная и чистая, она поражает своим тёмно-синим цветом. Температура в основном находится в районе 25 градусов. В водах океана обитают и рыбы, и млекопитающие, и планктон. На морском дне обосновались беспозвоночные животные организмы и падальщики.

В мелководных районах Тихого океана имеется много коралловых рифов. Недалеко от Австралии расположен самый крупный на земле Большой риф, который создали океанские организмы.

- Экологические проблемы Тихого океана

- История Тихого океана

Атлантический океан

Второй по величине океан на земном шаре ― Атлантический. Океан очевидно назван по имени героя из древнегреческой мифологии Атланта. Если учитывать прилегающие моря, то его площадь составляет 106 460 000 квадратных километров. Это почти 22% от площади всей нашей планеты. Форма океана зигзагообразная.

Расположен он в восточной части между Европой и Африкой, со стороны запада между Северной и Южной Америкой. В северной части Атлантический океан воссоединяется с Северным Ледовитым и разделяет Исландию и Гренландию. Со стороны юга он граничит с тремя океанами: Тихим, Индийским и Южным.

Среднее значение глубины около 4000 метров, а самой глубокой точкой является жёлоб Пуэрто-Рико ― 8 605 метров. Атлантический океан самый солёный по сравнению с другими океанами. Воды океана циркулируют в различных течениях, поэтому вода в одних частях тёплая, а в других ― прохладная. Климатические условия находятся в прямой зависимости от глубины и ветров. У побережья Африки в осенний период формируются сильные ураганные ветры. Со стороны юга на океан постоянно действует тропический сухой ветер, поэтому небо всегда покрыто красивыми ватными облаками. На Атлантике отсутствуют циклоны. Вода имеет тёмно-голубой оттенок, а в районе Африки и у южных берегов Бразилии приобретает ярко-зелёный цвет.

Интересные факты про Атлантический океан

Экваториальная часть отличается круглогодичной жаркой погодой, и вода в прибрежных зонах имеет мутный цвет. Очевидно из впадающих сюда многочисленных рек.

Разнообразие флоры и фауны удивляет обилием: хищные и летучие рыбы, акулы, мангровые заросли, огромное количество водорослей и морских трав. Растительность в основном располагается в верхних слоях океанических вод.

Главной достопримечательностью Атлантики является Срединно-Атлантический хребет. Его ширина примерно 1600 километров и он в основном находится под водой. Надводный слой равен примерно 2500 метров. Частично вершины хребта образуют надводные острова.

В Атлантический океан стекается пресная воды всех рек, поэтому вода в нём малосолёная. Поэтому кораллов в нём нет. Широченный пролив Атлантического океана находится между двумя полярными областями планеты. Он впадает в Тихий океан, но обитатели их сред отличаются из-за отличия в температурах. На дне Атлантики найдены газовые и нефтяные месторождения и драгоценные камни.

- Экологические проблемы Атлантического океана

- История Атлантического океана

Индийский океан

Третий по величине океан на земном шаре ― Индийский океан. Его площадь составляет 70 560 000 квадратных километров. Воды океана расположены между следующими материками: Африка, Азия, Австралия. Средняя глубина океана чуть меньше 4000 метров. Самая глубокая впадина, носящая название Зондского жёлоба, имеет глубину 7258 метров.

Северная часть Индийского океана похожа на море, она резко врезается в береговую часть. А в Южном полушарии он имеет самую большую ширину. Всего площадь океана составляет в пределах 20% от площади, занимаемой Мировым океаном.

Климатические условия в Индийском океане меняются при передвижении от северного направления к южному. В северной области преобладают муссоны. В зимнее время сухой воздух устремляется к материку Евразия, а летом двигается в сторону океанических вод. Из всех океанов мира погодные условия в Индийском океане являются самыми тёплыми. Приливы, возникающие на севере океана в основном слабые. Но если возникает одиночная волна, то она развивает очень большую скорость (до 20 км/ч), высота её может достигать 7-10 метров.

В Индийском океане есть архипелаг, в котором насчитывается 115 островов. Есть гранитные острова, а также коралловые, на которых живут наиболее разнообразные морские обитатели. Островные представители фауны Индийского океана: морские черепахи, морские птицы и многие другие экзотические животные. Большинство животного мира является эндемичным, то есть ограничивается географическим местом обитания и численностью.

Жуткие волны в Индийском океане

В Индийском океане наблюдается постоянное сокращение видов животного и растительного мира. Это связано с тем, что температура воды возрастает, что приводит к вымиранию планктона, в результате чего происходит нарушение пищевой цепи. Воды Индийского океана отличаются чистотой и прозрачностью. Их оттенок очень красив: он расположен в диапазоне от тёмно-голубого до лазоревого цвета.

Оказывается, морепродукты и рыбу человечеству поставляет именно Индийский океан. В глубинах океана имеется большое количество нефтяных запасов, полезных ископаемых, жемчуга, а в прибрежных районах много драгоценных камней.

- Экологические проблемы Индийского океана

- История Индийского океана

Северный Ледовитый океан

Самую маленькую площадь из имеющихся на нашей планете океанов имеет Северный Ледовитый океан. Она равна 14 060 000 квадратных километров. Среднее значение глубины океана примерно 1205 метров. Наибольшее значение самой глубокой впадины ― 4665 метров. Располагается Северный Ледовитый океан между Евразией и Северной Америкой, а основная масса воды сосредоточена около полюса. В самом центре океана находится точка Географического Северного полюса.

Большую часть года океан почти весь покрыт льдом, толщина которого примерно три метра. Летом льды частично тают. Здесь преобладает полярный климат и низкие температуры воздуха. Наиболее высокой является температура равная минус 20 градусов. Но даже при таких низких температурах, западная область океана не покрывается ледяными глыбами.

Обновляют и пополняют Северный Ледовитый океан воды, поступающие из Тихого и Атлантического океанов. Благодаря этому он получает тёплую воду и обладает способностью обогревать морских обитателей. Самая известная характеристика климата ― наличие полярных дней и ночей.

Интересные факты про Северный Ледовитый океан

В Северном Ледовитом океане самое низкое содержание соли по сравнению с другими океанами планеты. Это связано с низкой скоростью испарения холодной воды и поступлением пресной воды из рек и ручьёв, разбавляющих концентрацию соли.

Среди живых организмов имеются водоросли, которые удивительным способом приспособились к жизни в очень холодной воде, а также на льдинах. В воде обитают такие рыбы, как навага, палтус и треска. Привычными жителями Северного Ледовитого океана являются киты, тюлени и моржи.

Баренцево море богато планктоном, который в летний сезон собирает птиц и там образуются целые птичьи базары. Вдоль берегов океана геологи нашли месторождения нефти и природного газа, а также золота.

- Животные Северного Ледовитого океана

- Экологические проблемы Северного Ледовитого океана

- История Северного Ледовитого океана

Южный океан

Самым молодым океаном на Земле является Южный океан. Его официальное отделение произошло в 2000 году по решению Международной гидрографической организации. Но в атласах и на картах он так подписывался ещё в двадцатом веке.

Южный океан является условно обозначенным стечением южных областей трёх океанов: Тихого, Атлантического и Индийского. Он полностью омывает Антарктиду. А вот западные и восточные границы Южного океана пока ещё точно не обозначены. По площади он занимает четвёртое место. Она примерно равна 20 300 000 квадратных километров. Наибольшая глубина составляет 8264 метра (впадина Метеора).

В водах Южного океана имеется много островов. Большинство из них образовано в результате извержения вулканов, поэтому у них преобладает горный рельеф. Острова представляют собой хребты, котловины и небольшие поднятия.

Южный океан – есть ли такой?

Климат нельзя отнести к очень холодному, но он и не является тёплым. В среднем температура воды находится в диапазоне от -2 до +10 градусов. В районе Антарктиды постоянно дуют сильные ветры. Поэтому вдоль берега не образуется ледяной покров в течение всего зимнего сезона.

Южный океан насыщен айсбергами, которые плавают в нём круглый год. Некоторые айсберги имеют очень большие размеры. Их длина может достигать до 400 метров. Громадные ледяные глыбы иногда становятся причиной кораблекрушений.

Отличительной особенностью Южного океана является наличие в нём крупнейшего и очень мощного холодного поверхностного течения. Оно называется антарктическим циркумполярным течением, которое движется в восточном направлении, и превышает в сто раз потоки всех вместе взятых рек мира.

Климатические условия Южного океана являются суровыми. Несмотря на это, в нём достаточно активно развиваются живые организмы. Околополярное место благоприятно для развития фитопланктона. Рельефность дна океана не совсем благоприятна для обмена между фауной и флорой. А обитатели имеют непосредственную зависимость от условий. Здесь существует более 180 видов диатомовых водорослей. В Южном океане обитает довольно много зоопланктона, иглокожих, губок, криля, рыб из семейства Нототениевых. Главными обитателями Южного океана являются пингвины.

Видео про Южный океан

Почему Южный океан выделили отдельно? Океанографические исследования по изучению течений в океанах показали, что около Антарктиды имеются необычные явления, связанные с грядущим глобальным потеплением. Поэтому океан решили выделить как особую экологическую систему и назвали пятым океаном.

Но в учёном мире ещё продолжается дискуссия о количестве океанов на нашей планете. Независимо от указанных океанов на карте, на земном шаре имеется один Мировой океан. Все океаны Земли непосредственно связаны друг с другом и образуют единую систему.

Карта океанов мира

Вернуться к списку правил

ПРАВИЛА УПОТРЕБЛЕНИЯ ПРОПИСНЫХ И СТРОЧНЫХ БУКВ В ГЕОГРАФИЧЕСКИХ И АДМИНИСТРАТИВНО-ТЕРРИТОРИАЛЬНЫХ НАЗВАНИЯХ

Дата публикации 30 декабря 2021г.

Структура правил

Правило. В названиях природных географических объектов, явлений и условных линий и точек на поверхности планеты с прописной буквы пишутся все слова и соединенные дефисом части слов, кроме служебных слов внутри названия и слова имени (им.) (Гольфстрим). Пишутся со строчной буквы родовые наименования (номенклатурные термины), не входящие в состав названия (течение Гольфстрим).

Примечание 1. О структуре названий и терминов (однословные и неоднословные) и их порядке (Чёрное море, море Лаптевых).

Примечание 2. О типах слов, входящих в географическое название: 1) существительные, значение которых не соответствует роду названного географического объекта (Голодная Губа (озеро)), 2) несамостоятельные иноязычные родовые наименования (Рио-Гранде (рио ‘река’)), 3) существительные с уменьш. суф., образованные от родовых наименований (Красное Озерко (озеро)); 4) существительные, называющие титулы, звания, профессии, должности и под. (Адмирала Кузнецова (хребет)), 5) прилагательные (Верхняя Тунгуска (река)), 6) числительные (Первое Скитское (озеро), Аслыкуль 1-е (озеро)).

Примечание 3. О разных функциях родовых терминов.

Правило. В официальных (полных и кратких) названиях современных государств все слова и соединенные дефисом части слов пишутся с прописной буквы, кроме служебных слов (Российская Федерация, Республика Маршалловы Острова, Республика Кот-д’Ивуар).

Примечание. О написании неофициальных названий государств, а также официальных и неофициальных названий объединений государств (Древняя Русь, Российская империя, Прикаспийские страны, Страна кленового листа).

Правило 1. В официальных названиях территориальных и административно-территориальных единиц, населенных пунктов (регионов, краев, областей, округов, провинций, земель, штатов, городов и под.) с прописной буквы пишутся все слова и соединенные дефисом части слов (Восточная Европа, Санкт-Петербург), кроме служебных слов внутри названия и слов имени (им.), лет, км (Ростов-на-Дону, село им. Мичурина). Пишутся со строчной буквы слова, указывающие на тип административно-территориальной единицы, не входящие в состав названия (родовые наименования) (Красноярский край, район Южное Бутово, рабочий посёлок Чистоозёрное).

Исключение-подправило. Написание названий населенных пунктов, включающих наименование объекта-ориентира (посёлок Дома отдыха, деревня Кирпичный завод).

Примечание 1. О структуре названий и терминов (однословные и неоднословные) и их порядке.

Примечание 2. О типах слов, входящих в административное название: 1) существительные, значение которых не соответствует типу названного объекта (Большой Улус (деревня)), 2) исторические, устаревшие и иноязычные слова, называющие тип населенного пункта (Сергиев Посад (город)), 3) существительные во множественном числе или с уменьшительными суффиксами, образованные от родовых наименований (Лесной Городок (посёлок)); 6) числительные и др.

Примечание 3. О разных функциях родовых терминов.

Примечание 4. О написании названий территориальных зон с особыми экономическими, правовыми и др. характеристиками.

Примечание 5. О границах применения правила и написании названий по традиции.

Правило 2. В неофициальных, образных названиях городов с прописной буквы пишется первое слово и собственные имена (Первопрестольная (о Москве), Вечный город (о Риме).

Правило. В названиях улично-дорожной сети населенных пунктов и транспортной инфраструктуры с прописной буквы пишутся все слова и соединенные дефисом части слов, кроме служебных слов внутри названия и слов имени (им.), года, лет, км. Пишутся со строчной буквы слова, указывающие на тип называемого объекта, не входящие в состав названия (родовые наименования) (набережная Гребного канала, московский международный аэропорт Внуково).

Исключение-подправило 1. Написание названий, включающих наименование объекта-ориентира в род. падеже (площадь Трёх вокзалов).

Исключение-подправило 2. Написание названий станций метро, остановок общественного транспорта.

Примечание 1. О структуре названий и терминов (однословные и неоднословные) и их порядке.

Примечание 2. О типах слов, входящих в названия улично-дорожной сети населенных пунктов и объектов транспортной инфраструктуры: 1) существительные, значение которых не соответствует типу названного объекта (Кузнецкий Мост (улица)), 2) слова, обозначающие титулы, звания, профессии, должности и под. (улица Генерал-Фельдмаршала Румянцева), 3) условные названия организаций, заключенные в кавычки (улица Газеты «Комсомольская правда»), 4) числительные.

Примечание 3. О разных функциях родовых терминов.

Примечание 4. О написании названий автомобильных магистралей.

Примечание 5. О написании названий зон с особыми экономическими, правовыми и др. характеристиками.

Примечание 6. О написании названий по традиции.

Примечание 7. О границах применения правила.

Предварительные замечания

Написание географических названий закрепляется традицией местного употребления и юридическими документами, например законодательными актами субъектов РФ, Государственным каталогом географических названий. При этом естественно, что конкретные названия, появившиеся и закрепившиеся в разные периоды истории, могут не соответствовать современным правилам. Орфографические словари и справочники лишь фиксируют уже имеющиеся названия, поскольку лингвисты не имеют правовых возможностей для их перекодификации.

В последние десятилетия в России, как и во всем мире, продолжается масштабная работа по стандартизации написания названий географических объектов. В Федеральной службе государственной регистрации, кадастра и картографии и сейчас непрерывно идет коррекция Государственного каталога географических названий. Одним из обязательных требований при изменении старых названий или фиксации новых является их соответствие правилам русской орфографии.

Единственным официально утвержденным в настоящее время текстом правил являются «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» 1956 г. Со времени опубликования этих правил реальное написание топонимов и на картах, и в официальных документах, и в письменных текстах других типов постепенно подравнивалось под введенные нормы. Однако неисчислимость самого материала, разнообразие структурно-орфографических типов названий привели к необходимости дополнить утвержденные правила в специальных инструкциях для картографов.

В 1961 г. вышел справочник «Правила написания на картах географических названий СССР» (2-е изд. 1967 г.), в котором общие правила написания топонимов были существенно дополнены. Впоследствии эти правила вошли в «Практическое руководство по наименованию и переименованию географических объектов СССР» 1987 г. В 2006 г. вышел академический справочник «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации», в котором раздел о написании топонимов был значительно расширен по сравнению с Правилами 1956 г. Однако и эти справочники не внесли полной определенности в некоторые случаи выбора написания, также остались спорные типы написаний, допускающие двоякое толкование, остались и вообще не отраженные в справочниках типы написаний, например названия населенных пунктов, созданных при каких-либо организациях и включающих в себя названия этих организаций.

Предлагаемые ниже правила были разработаны на основе анализа реального современного употребления топонимов разных типов в разнообразных источниках: в орфографических и топонимических словарях, в обладающих юридической силой каталогах, реестрах, классификаторах; в региональных и общегосударственных документах, публицистических и художественных текстах, на бумажных и электронных картах. Для определения исторической направленности изменений написания топонимов были проанализированы исторические словари и научная литература, описывающая историческую динамику изменения и современные тенденции. В результате была обозначена и подтверждена основная тенденция в наименовании топонимических объектов – к расширению области действия правила 1956 г., это касается и реальной практики письма и нормативных рекомендаций в разных источниках. Одновременно были выявлены типы наименований, в которых неоднозначно понимается структура топонима: какое слово является родовым термином, а какое – именем собственным[1]. В случае возможности двоякой семантической интерпретации нормативное решение о выборе написания принималось Орфографической комиссией РАН.

Правила рекомендованы Орфографической комиссией РАН (2020 г.).

Правила кодифицируют норму, отражающую системные орфографические явления. Они призваны отвечать на вопрос, как рекомендуется писать названия представленных в правиле типов. Таким образом, данные правила в большей степени предписывают норму написания и, значит, направлены на упорядочение письма, а не описывают существующую орфографическую реальность, так как исчислить все исключения из правил, закрепленные традицией и/или официальными документами, на данном этапе невозможно. Неисчислимость материала обуславливает одну такую особенность правил написания топонимов, как отсутствие списков исключений.

Рекомендация для пользователей

Правила § 3 и § 4 следует применять при первой фиксации наименования или при переименовании какого-либо объекта. Они представляют общеязыковую норму написания названий территориальных, административно-территориальных единиц, населенных пунктов, объектов улично-дорожной сети и транспортной инфраструктуры и используют критерии выбора написания, сформулированные в Правилах 1956 г. В правилах не отражена та часть местных наименований, написание которых правилам не соответствует (то есть не приводится список исключений), так как не представляется возможным выявить все случаи, закрепленные традицией или официальными документами.

Например, наблюдается варьирование употребления прописной/строчной буквы во вторых компонентах названий, выраженных родовыми наименованиями, значение которых не соответствует типу называемого объекта. Так, название поселка может передаваться и как Дальнее поле, и как Дальнее Поле (Ульяновская область), в одних регионах зафиксированы названия деревень Клубоковская Выставка (Архангельская область) и Малая Выставка (Псковская область), а в других – Грибошинский выставок, Захаровский выставок, Ушкинский выставок (Кировская область). Также может варьироваться написание постпозитивных определительных компонентов топонимов, напр.: деревня Буда-первая / Буда Первая (Каужская область), село Амуши большое / Амуши Большое (Республика Дагестан). Во всех этих случаях следование правилу требует употребления во втором компоненте прописной буквы и дефиса (Буда-Первая, Амуши-Большое). Один из проспектов Архангельска называется Обводный канал, здесь употребление строчной буквы в слове канал не соответствует требованию правил писать прописную, если существительное – родовой термин не указывает на тип обозначаемого объекта, как, например, в названиях (улица) Чёрная Дорога, (площадь) Васильевский Спуск и под.

ПРАВИЛА УПОТРЕБЛЕНИЯ ПРОПИСНЫХ И СТРОЧНЫХ БУКВ В ГЕОГРАФИЧЕСКИХ И АДМИНИСТРАТИВНО-ТЕРРИТОРИАЛЬНЫХ НАЗВАНИЯХ

Правила составлены Е. В. Арутюновой, Е. В. Бешенковой, О. Е. Ивановой

§ 1. Названия природных географических объектов

Правило. В названиях природных географических объектов, явлений (океанов, морей, рек, озер, материков, островов, гор, равнин, течений и под.) и условных линий и точек на поверхности планеты (меридианов, полюсов и др.) с прописной буквы пишутся все слова и соединенные дефисом части слов (Южная Америка, Тянь-Шань, Эль-Ниньо), кроме служебных слов[2] внутри названия и слова имени (им.) (Па-де-Кале, Абд-эль-Кури, залив им. Максима Горького). Пишутся со строчной буквы родовые наименования (номенклатурные термины), не входящие в состав названия (Восточно-Европейская равнина, Северный Ледовитый океан, озеро Байкал, река Ангара, озеро Под Быком, море Лаптевых).

Примеры:

• полушария земные, полюсы географические, меридианы и т. п.: Восточное полушарие, Западное полушарие, Гринвичский меридиан, Пулковский меридиан, Северный полюс, Южный полюс, Северный тропик (тропик Рака), Южный тропик (тропик Козерога), Северный полярный круг, Южный полярный круг;

• материки и их части, острова, полуострова, архипелаги, мысы, мели и т. п.: Австралия, Антарктида, Африка, Евразия, Северная Америка, Южная Америка, Европа, Азия, Океания, Сибирь, Голарктическая область, Канадский Арктический архипелаг, остров Новая Гвинея, остров Шикотан, Васильевский остров, остров Святой Елены, полуостров Святой Нос, остров Пасхи, Новосибирские острова, мыс Край Света, мыс Доброй Надежды, Большой Барьерный риф, Большая Багамская банка;

• океаны, моря, заливы, губы, проливы, течения, впадины и т. п.: Атлантический, Индийский, Северный Ледовитый, Тихий океаны, Адриатическое море, Обское море[3], Чёрное море, море Лаптевых, Восточно-Китайское море, Бейсугский лиман, Мессинский пролив, Онежская губа, Онежское озеро, Марианская впадина, Северо-Американская котловина, Новогебридский жёлоб, залив Благополучия, пролив Лаперуза, Первый Курильский пролив, течение Западных Ветров;

• горы, равнины, пустыни, низменности и т. п.: Алтай, Альпы, Анды, Большой Кавказ, Малый Кавказ, Гималаи, Кордильеры, Пиренеи, Саяны, Трансантарктические горы, Тянь-Шань, Урал, Большая Курильская гряда, Главный Кавказский хребет, хребет Академии Наук, горный массив Сьерра-де-ла-Деманда, Арбуканский голец, пик Ането, сопка Сапог, вулкан Везувий, гора Фудзияма, перевал Трёх Пагод, ледник Северный Энгильчек, шельфовый ледник Ларсена, Восточно-Европейская равнина, Среднесибирское плоскогорье, Северо-Байкальское нагорье, Западно-Сибирская низменность, плато Устюрт, пустыня Сахара, Большая Песчаная пустыня, долина Архыз;

• реки, водопады, озера, болота и т. п.: Амазонка, Амударья, Амур, Ангара, Волга, Ганг, Миссисипи, Обь, Белый Нил, озеро Байкал, озеро Большой Вагильский Туман, Большое Стромилово болото, Васюганские болота, водопад Кивач;

• другие географические объекты: система пещер Моравский Крас, Новоафонская пещера, Беловежская пуща, Владимирское ополье, Куликово поле, Лазурный берег, Волго-Донское междуречье, Нижний Траянов вал, котловина Больших Озёр, Донецкий угольный бассейн, Западно-Канадский нефтегазоносный бассейн, Западно-Сибирский артезианский бассейн, Капская складчатая зона, Курская магнитная аномалия, Охотско-Чукотский вулканогенный пояс, Тихоокеанское вулканическое огненное кольцо;

• географические явления: Северо-Тихоокеанское течение, течение Гольфстрим, ураган Катрина, ураган Новая Англия, тайфун Хагибис;

• названия с дефисным написанием: Ай-Петри (гора), Вест-Индия (острова), Гранд-Фолс (водопад), Диего-Гарсия (остров), Иссык-Куль (озеро), Кара-Богаз-Гол (залив), Лонг-Айленд (остров), Рио-Гранде (река), Сан-Педро (вулкан), Санта-Мария (остров), Сент-Килда (архипелаг), Сердце-Камень (мыс), Сихотэ-Алинь (горный хребет), Шри-Ланка (остров), Индо-Гангская равнина, Онон-Аргунская степь, Северо-Германская низменность, Урало-Тянь-Шаньская складчатая область; Ильмень-озеро, Москва-река, Сапун-гора, Согне-фьорд[4];

• названия со служебными словами: Де-Лонга (острова), Ла-Манш (пролив), Эс-Саадия (озеро); Абд-эль-Кури (остров), Па-де-Кале (пролив), Охос-дель-Саладо (вулкан), Рио-Браво-дель-Норте (река), Тристан-да-Кунья (остров), Шатт-эль-Араб (река).

Примечание 1. По структуре названия могут быть однословными (Австралия, Урал, Ямал) и неоднословными (Моравский Крас, Новая Гвинея). Термины также могут быть однословными (море, остров, гора, долина) и неоднословными (угольный бассейн, бассейн реки, горный массив, южная гряда массива, нефтеносный шельф, шельфовый ледник). Название может стоять перед термином (Беловежская пуща, Капская складчатая зона, Большое Стромилово болото), после него в форме им. падежа (архипелаг Новая Земля, горный массив Сьерра-де-ла-Деманда, сопка Сапог) или род. падежа (залив Благополучия, мыс Доброй Надежды).

Примечание 2. В состав географического названия могут входить слова разных типов, напр.:

• существительные, в том числе географические термины, значение которых не соответствует роду названного географического объекта, напр.: Адамов Мост (цепь скал и отмелей), Большой Бассейн (плоскогорье), Ветреный Пояс (кряж), Голодная Губа (озеро), (острова) Зелёного Мыса, Золотой Рог (бухта), Золотые Ворота (пролив), Огненная Земля[5] (архипелаг), (острова) Комсомольской Правды[6], Лосиный Остров (природная зона в Москве), Старик-Камень (гора), Тёплый Ключ (ручей), Чёрная Сопка (река), Тихая Сосна (река), Чешский Лес (горы), Долина Царей (территория в Египте – некрополь фараонов)[7];

• иноязычные родовые наименования, не употребляющиеся в русском языке как самостоятельные существительные, напр.: Иссык-Куль (куль ‘озеро’), Кара-Богаз-Гол (богаз ‘проход’, пролив, гол ‘озеро’), Поперечная Вулканическая Сьерра (сьерра ‘горная цепь’), Рио-Гранде (рио ‘река’), Сноуи-Ривер (ривер ‘река’), Тянь-Шань (шань ‘гора’);

• существительные с уменьшительными суффиксами, образованные от родовых наименований, напр.: Большая Речка (река), Кривая Речка (река), Сосновая Горка (гора), Таёжный Ручеёк (ручей), Красное Озерко (озеро);

• существительные, называющие титулы, звания, профессии, должности и под., напр.: (пролив) Адмирала Кузнецова, (хребет) Академика Обручева, (острова) Земля Королевы Шарлотты, (остров) Принца Уэльского, (мыс) Капитана Джеральда;

• прилагательные, в том числе слова Верхняя, Нижняя в названиях отдельных рек, напр.: (залив) Святого Лаврентия, (горы) Низкие Татры, (горы) Монгольский Алтай, (река) Верхняя Таймыра, (река) Верхняя Тунгуска, (река) Нижняя Тунгуска, (река) Средняя Терсь (ср.: верхняя Волга[8], верхняя Лена, верхняя Припять, нижняя Ока, нижний Дон как указание на участок течения реки);

• порядковые числительные, напр.: Вторая (падь), Двадцать Первыи Километр (падь), Первое Скитское (озеро), Макариха Вторая (грива), Прямой I (перекат), Аслыкуль 1-е (озеро)[9].