Арабская система счисления сейчас процветает повсюду, и ее использование — это некий стандарт. Это неудивительно: десятичная, позиционная система записи чисел очень удобна и логично устроена. С момента ее изобретения все остальные менее продвинутые вариации отошли на второй план. Тем не менее полностью они не исчезли: римской системой записи цифровых знаков мы пользуемся и по сей день, причем чаще, чем нам кажется.

Несмотря на то что мы пользуемся арабской системой счисления, периодически все же приходится набирать на клавиатуре римские цифры. Они иногда используются для записи веков, нумерования правителей или томов в книгах. Встречаются они и в неожиданных местах: при указании группы крови, валентности в химии или времени на механических часах. Одним словом, они все еще актуальны.

Содержание:

- Способы

- Конвертер

- Латинские буквы

- ASCII-коды

- Программные команды

- Видео

Способы

Конвертер

Если вам совсем лень разбираться, как набрать римские цифры на клавиатуре, воспользуйтесь одним из заботливо написанных специально для вас конвертеров. Вы легко найдете его по соответствующему запросу в поисковой системе. Пригодится он и скрупулезным, но осторожным людям, которым нужно записать длинное и сложное число.

Латинские буквы

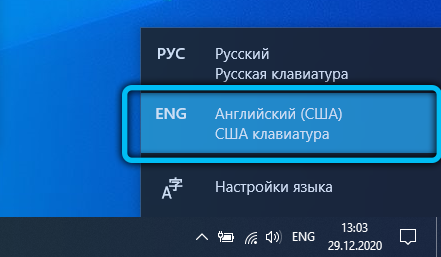

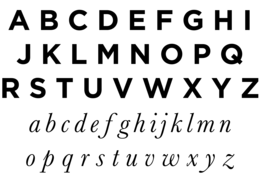

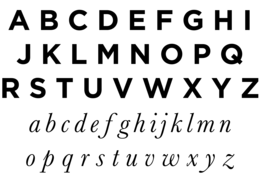

Присмотритесь повнимательнее к римским цифрам. Они вам ничего не напоминают? Правильно, это всем нам знакомый латинский алфавит! Благодаря этому все их можно без труда набрать на английской клавиатуре (или другой, на которой раскладка с латиницей). Переключившись на иноязычную раскладку, вы сможете вводить любое римское число.

Римская система счисления — непозиционная, то есть каждая цифра в ней равна тому числу, которое она обозначает. Соответственно, чтобы написать длинное число, может понадобиться несколько раз употребить одну и ту же цифру. К счастью, есть определенные правила группировки, которыми тоже можно воспользоваться. Их мы рассмотрим далее.

Цифры от 1 до 3 не представляют сложности: I, II, III. Все они образованы с помощью буквы i из латиницы.

Цифра 4 чуть более сложна: здесь нужно задействовать математику. Специального обозначения для нее у римлян нет, зато есть обозначение для пятерки — V, а четверку получаем, отняв от нее единицу, что выражается перестановкой ее слева от пятерки: IV. Справа — прибавляем, слева — отнимаем. Все просто.

По этому же правилу получаем цифры 6 (VI), 7 (VII), 8 (VIII).

Для девятки используется уже новая буква — X, обозначающая 10. От нее мы, опять же, отнимаем единицу, чтобы вышло девять — IX. Думаю, на этом принцип стал вам понятен.

Для записи более крупных чисел нам понадобятся еще буквы, поэтому держите:

- 50 — L;

- 100 — C;

- 500 — D;

- 1000 — M.

Теперь вы сможете напечатать на клавиатуре любое римское число.

ASCII-коды

ASCII — это стандартная таблица символов Windows, в которой каждому символу отведен собственный цифровой код. Даже если вы не находите нужных знаков на клавиатуре (или их там и правда нет), вы сможете ввести их без посторонней помощи, ниоткуда их не копируя, если помните их номер наизусть. Для этого зажмите клавишу Alt и, не отпуская ее, введите цифры по порядку. Не предлагаем вам заучивать коды всех римских цифр, то есть латинских букв, а лучше приведем их здесь:

- I = 73;

- V = 86;

- X = 88;

- L = 76;

- C = 67;

- D = 68;

- M = 77.

Зачем это все, если можно просто переключиться на английскую раскладку? На самом деле, такая информация не помешает, если по каким-то причинам вы не можете на нее переключиться или у вас попросту установлен только русский язык на компьютере. Конечно, писать длинные числа таким образом будет несладко, а вот пару-тройку символов — самое то!

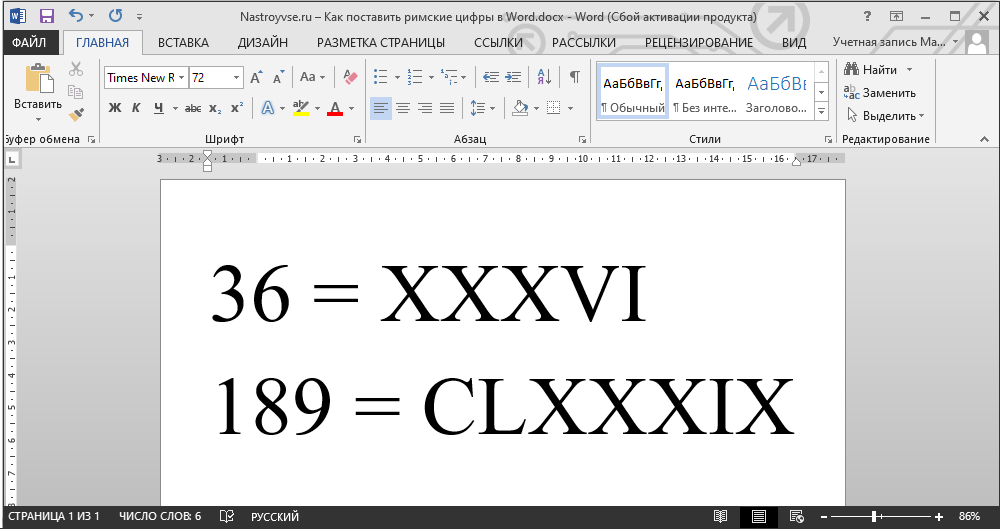

Программные команды

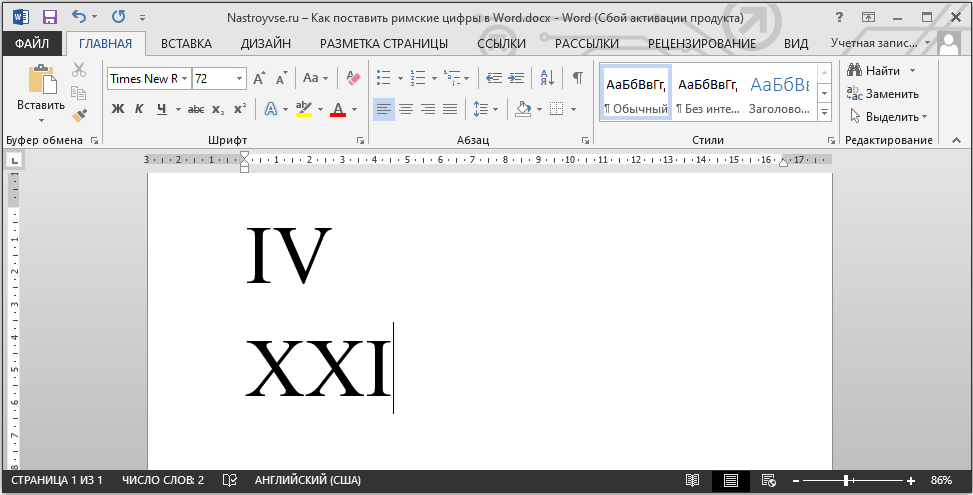

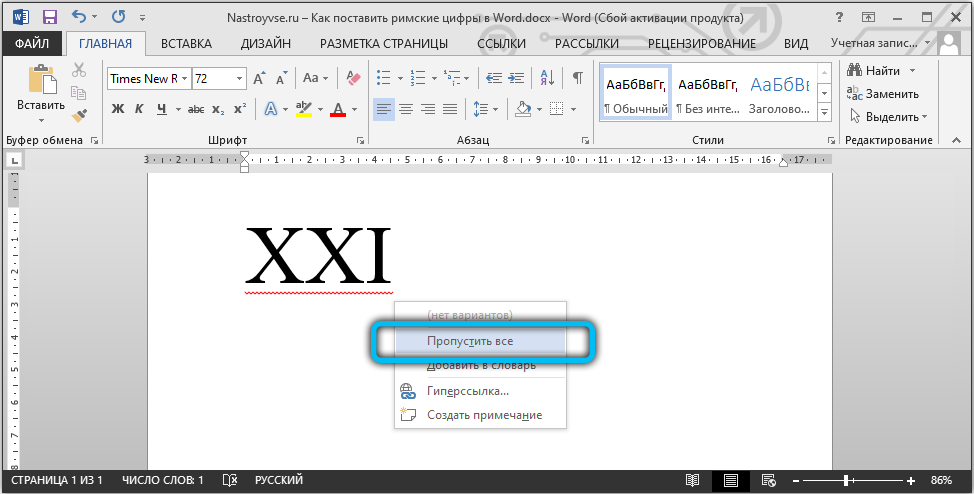

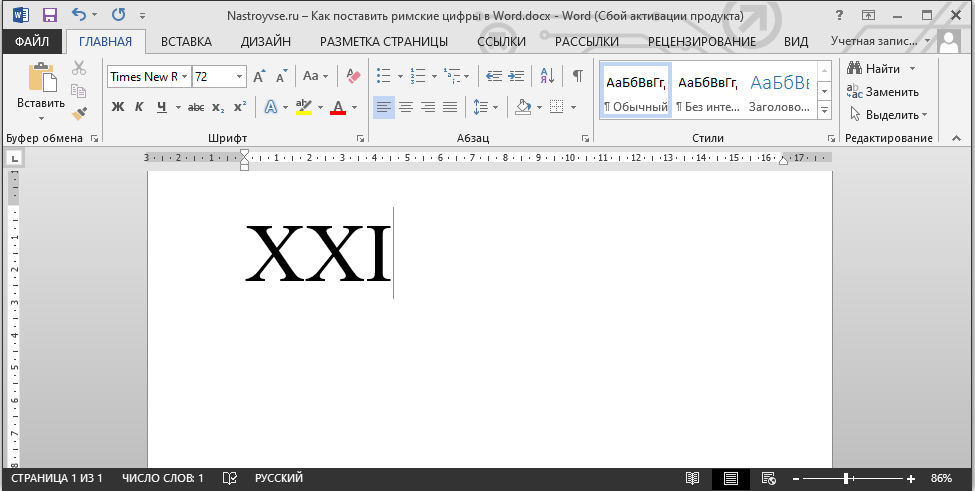

В привычных нам программных продуктах есть немало неизвестных нам функций, которые порой и показались бы нужными, да не знает о них почти никто, кроме производителя и тех, кому они жизненно необходимы. Не выделяется на их фоне и Microsoft Word. Оказывается, в нем есть специальная команда, при включении которой обычные арабские цифры будут превращаться в римские.

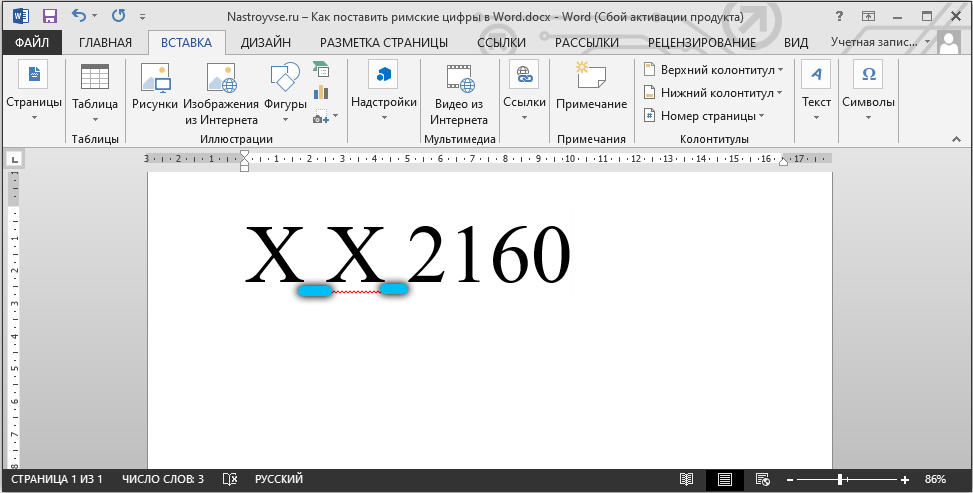

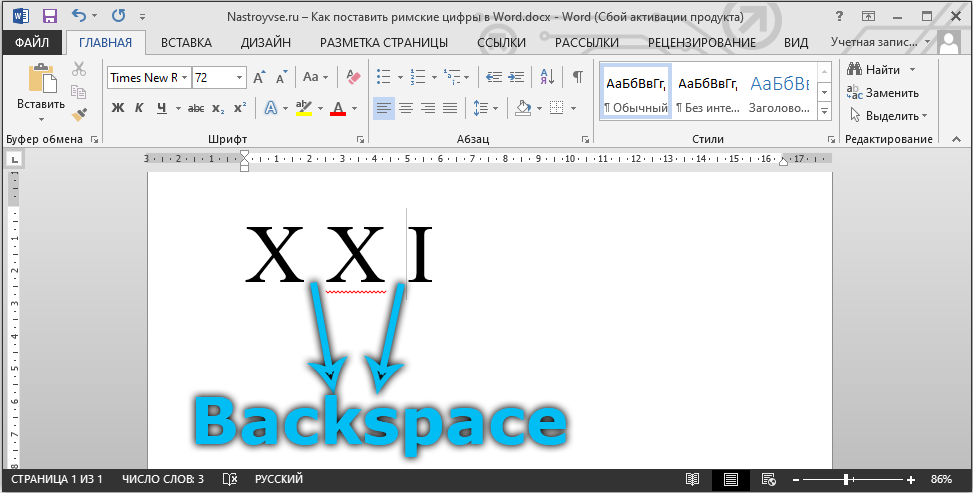

Это магическое действие легко осуществить, совершив следующие действия:

- Кликните по участку документа, где должно быть римское число.

- Нажмите комбинацию Ctrl+F9. Это нужно для вызова поля для кода. Оно будет залито серым цветом, а справа и слева будут находиться фигурные скобки.

- Введите следующую команду, заменив слова «арабское число» на необходимое вам:

=арабское число*ROMAN

Теперь остается только нажать F9, чтобы команда заработала и цифры превратились в римские.

Резюмируя вышесказанное: набирать на клавиатуре римские цифры не так-то сложно! Советуем вам освоить их набор на английской клавиатуре, если приходится часто этим заниматься. Если же в повседневной жизни это вам не нужно, можете воспринимать эту статью как ознакомительную.

Видео

Посмотрите, как можно напечатать римские цифры в Ворде.

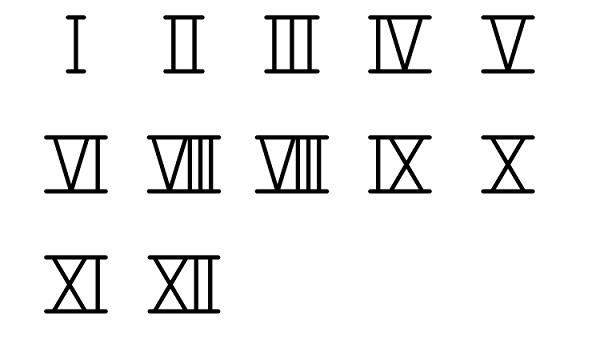

Выучить их несложно:

- 1 = I

- 5 = V

- 10 = X

- 50 = L

- 100 = C

- 500 = D

- 1000 = M

Все цифры от 1 до 100 (остальные по аналогии) можно посмотреть в таблице:

| I | 1 | XXVI | 26 | LI | 51 | LXXVI | 76 |

| II | 2 | XXVII | 27 | LII | 52 | LXXVII | 77 |

| III | 3 | XXVIII | 28 | LIII | 53 | LXXVIII | 78 |

| IV | 4 | XXIX | 29 | LIV | 54 | LXXIX | 79 |

| V | 5 | XXX | 30 | LV | 55 | LXXX | 80 |

| VI | 6 | XXXI | 31 | LVI | 56 | LXXXI | 81 |

| VII | 7 | XXXII | 32 | LVII | 57 | LXXXII | 82 |

| VIII | 8 | XXXIII | 33 | LVIII | 58 | LXXXIII | 83 |

| IX | 9 | XXXIV | 34 | LIX | 59 | LXXXIV | 84 |

| X | 10 | XXXV | 35 | LX | 60 | LXXXV | 85 |

| XI | 11 | XXXVI | 36 | LXI | 61 | LXXXVI | 86 |

| XII | 12 | XXXVII | 37 | LXII | 62 | LXXXVII | 87 |

| XIII | 13 | XXXVIII | 38 | LXIII | 63 | LXXXVIII | 88 |

| XIV | 14 | XXXIX | 39 | LXIV | 64 | LXXXIX | 89 |

| XV | 15 | XL | 40 | LXV | 65 | XC | 90 |

| XVI | 16 | XLI | 41 | LXVI | 66 | XCI | 91 |

| XVII | 17 | XLII | 42 | LXVII | 67 | XCII | 92 |

| XVIII | 18 | XLIII | 43 | LXVIII | 68 | XCIII | 93 |

| XIX | 19 | XLIV | 44 | LXIX | 69 | XCIV | 94 |

| XX | 20 | XLV | 45 | LXX | 70 | XCV | 95 |

| XXI | 21 | XLVI | 46 | LXXI | 71 | XCVI | 96 |

| XXII | 22 | XLVII | 47 | LXXII | 72 | XCVII | 97 |

| XXIII | 23 | XLVIII | 48 | LXXIII | 73 | XCVIII | 98 |

| XXIV | 24 | XLIX | 49 | LXXIV | 74 | XCIX | 99 |

| XXV | 25 | L | 50 | LXXV | 75 | C | 100 |

Где на клавиатуре римские цифры?

Отдельная нумерационная линейка на клавиатурах отсутствует. По своей сути римские цифры – это буквы латинского алфавита. Соответственно, для проставления нумерации мы переключаем раскладку на латиницу, чтобы вставить соответствующие буквы в верхнем регистре.

Как написать на клавиатуре персонального компьютера или ноутбука на операционной системе Windows?

Для перехода на латинский алфавит нам потребуется переключение раскладки клавиатуры на английскую версию. Это можно сделать так: в английской раскладке нажмите CapsLock и набирайте любые латинские буквы сразу в верхнем регистре.

Как набрать в Ворде (текстовый редактор Microsoft Office Word)?

Чтобы поставить римские цифры в текстовой программе Ворд, мы нажимаем заглавные буквы в английской версии, набирая нужное число.

Как ввести в тексте?

Для ввода цифр в римской системе используются следующие комбинации:

|

Комбинация клавиш |

Описание |

|

Shift+Ш (I) нужное количество раз |

I, II, III |

|

Shift+Ш (I)+М (V) нужное количество раз |

IV, V, VI, VII, VIII |

|

Shift+Ч (Х)+Ш (I) |

X, IX, X |

|

Shift+Д (L) |

L |

|

Shift+Ь (M) |

M |

|

Shift+C |

C |

Некоторые буквы аналогичны русским (М, С), их можно напечатать и в русской версии раскладки.

Нумерация списка

Для проставления автоматической нумерации воспользуйтесь панелью инструментов – нам нужен раздел «Абзац» и функция нумерованного списка (не с точками или комбинированный). Далее выбирайте соответствующий вариант нумерации с римскими обозначениями. Можно ввести подпункты с числовой или символической нумерацией.

Как напечатать в экселе (табличный редактор Microsoft Office Excel)?

Аналогично включают раскладку клавиатуры на английский вариант и набирают буквы в верхнем регистре (см. п. 2). Есть еще вариант «Вставка символа» через меню «Вставка», где можно скопировать из алфавита соответствующую букву, но это займет больше времени.

Как сделать римские цифры в PowerPoint (редактор презентаций)?

Так как римские цифры – это текст, здесь потребуется функция вставки текста из панели инструментов. Нажав на нее, вы создадите рабочее окно, где можно набирать англоязычные цифры.

Если требуется автоматическая нумерация пунктов для текста, активируют меню списков и выбирают вариант с римскими обозначениями, его легко найти из предлагаемых.

Как ввести на телефоне?

Андроид (Самсунг и другие).

Андроид – популярнейшая в мире операционная система, так как подходит для большинства смартфонов. Здесь набор римских цифр осуществляется через английскую раскладку. Нажимаем иконку с изображением глобуса, затем зажимаем клавишу Shift для повышения регистра – и можно набирать цифры.

Айфон

Операционная система iOs упрощена до предела, но принцип набора римских символов на клавиатуре айфона тот же. Нажимаем в телефонной клавиатуре иконку с изображением глобуса, затем зажимаем клавишу Shift для повышения регистра – и можно набирать символы.

Как набрать на планшете (Айпад и др.)?

В англоязычной раскладке устанавливаем написание заглавными буквами через клавишу Shift и набираем буквы на клавиатуре.

Как напечатать в Опен офис?

Принцип аналогичен работе в процессоре Microsoft Word. Здесь можно скопировать буквы из набора в меню или писать вручную буквы английским текстом.

Ручной набор на макбуке или аймаке (MacOS)

Если нажать на клавиатуре Макбука комбинацию Command + Пробел, то можно переключить на английский язык, латиница станет доступной для набора.

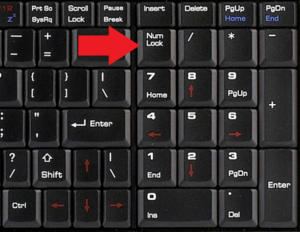

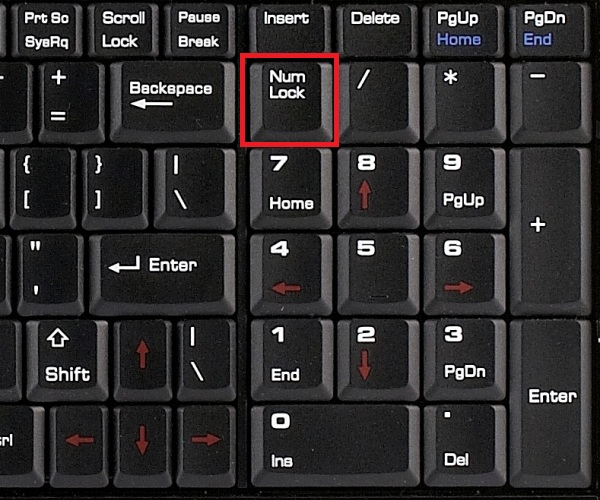

Как набрать, используя ASCII-коды?

Это не самый удобный и современный способ набора нужного символа на ПК, но им тоже иногда требуется воспользоваться, когда работаете через комп. Для этой цели потребуется включение дополнительной клавиатуры NumLock. Затем используется параллельное нажатие клавиши Alt и цифр на нумпаде. Как только символ отобразится на экране, клавишу Alt надо отпустить, затем нажать для ввода следующего.

Используются такие комбинации:

|

Комбинация клавиш |

Описание |

|

Alt+73 |

I |

|

Alt+86 |

V |

|

Alt+88 |

X |

|

Alt+76 |

L |

|

Alt+67 |

C |

|

Alt+68 |

D |

|

Alt+77 |

M |

Теперь вы знаете, как можно пронумеровать текст разными способами и на разных видах клавиатуры. Пользуйтесь тем, который наиболее удобен, чтобы четко и красиво пронумеровать любой список, проставить исторические даты и элегантно оформить документ в соответствии с нормативами, стандартами и общепринятыми требованиями!

Здравствуйте, друзья! Сегодня, в рамках рубрики «Компьютерная грамотность», я расскажу как напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры. Несмотря на то, что пользуемся мы в основном арабскими цифрами, римские цифры иногда всё-таки нам могут потребоваться. Например, на том же сайте госуслуг. Отчего-то в некоторых формах в полях заполнения требуют ввести именно римские цифры.

Напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры не так уж и сложно. Ниже я покажу три способа того, как именно это можно сделать. Первый способ подойдёт тем, кому печатать на клавиатуре римские цифры приходится часто. А второй способ подойдёт для тех, кому печатать римские цифры на клавиатуре приходится достаточно редко. Или по какой-то причине раскладка клавиатуры не переключается на английский язык. Ну, а третий способ для тех, кто не хочет по какой-либо причине, как говориться, заморачиваться с первыми двумя способами.

Содержание

- Как напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры

- Первый способ

- Второй способ

- Как напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры. Третий способ.

Как напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры

Первый способ

Переключите раскладку клавиатуры на английский язык. Можете нажать клавишу Caps Lock или нажать и удерживать клавишу Shift. Как вам удобней. Это делается потому что, как мы все помним, римские цифры пишутся заглавными латинскими буквами. А теперь просто вспоминаем как они выглядят и ориентируемся на то, что написано ниже.

Римская цифра 1 выглядит как заглавная латинская i. Соответственно, для того чтобы напечатать римскую цифру 1, мы набираем на клавиатуре в английской раскладке I. Для того, чтобы набрать 2 или 3 мы соответственно набираем заглавное I два или три раза.

Для того чтобы набрать римскую 4 набираем заглавную I и потом заглавную V (она как раз является римской цифрой 5). Получится IV. Потому же принципу набираются все римские цифры до 9. Для того чтобы напечатать 9, набираем I и дальше X. Получится римская 9 — IX.

Я думаю, что принцип вы поняли. Поэтому не буду показывать каждое число. Просто напомню, как выглядят основные римские цифры.

- 1 — I

- 5 — V

- 10 — X

- 50 — L

- 100 — C

- 500 — D

- 1000 — M

Соответственно, все остальные числа набираются комбинациями добавляемыми к этим цифрам. Если вам нужно, то вот вам таблица.

Второй способ

Этот способ заключается в наборе комбинаций цифр в правом дополнительном блоке с цифрами. Он более трудоёмкий, но если у вас не переключается раскладка на английский язык, то можно им воспользоваться.

Зажимаете клавишу Alt и, не отпуская ёё, вводите комбинации цифр.

- I — 73

- V — 86

- X — 88

- L — 76

- C — 67

- D — 68

- M — 77

Но, повторюсь, этот способ крайне неудобен.

Как напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры. Третий способ.

Это самый простой способ. Правда, тут римские числа на клавиатуре не набираются. Я предлагаю вам воспользоваться онлайн конвертером чисел. Да-да. Есть и такие. Всё очень-очень просто. Пишите в поле ввода обычными арабскими цифрами нужное вам число. Нажимаете кнопку «Конвертировать».

В том же поле появится нужное вам число только уже римскими цифрами. Вы просто его копируете и вставляете туда, куда вам нужно. Находится этот замечательный онлайн конвертер чисел вот по этой ссылке.

На этом у меня сегодня всё. Как напечатать на клавиатуре римские цифры я вам рассказал. Всем удачи и до встречи!

For the Latin script originally used by the ancient Romans to write Latin, see Latin alphabet.

| Latin

Roman |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c. 700 BC – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

Official script in: 132 sovereign states

Co-official script in: 15 sovereign states

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

|

Child systems |

|

|

Sister systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

See Latin characters in Unicode |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern Italy (Magna Grecia). It was adopted by the Etruscans and subsequently by the Romans. Several Latin-script alphabets exist, which differ in graphemes, collation and phonetic values from the classical Latin alphabet.

The Latin script is the basis of the International Phonetic Alphabet, and the 26 most widespread letters are the letters contained in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

Latin script is the basis for the largest number of alphabets of any writing system[1] and is the

most widely adopted writing system in the world. Latin script is used as the standard method of writing for most Western and Central, and some Eastern, European languages as well as many languages in other parts of the world.

Name[edit]

The script is either called Latin script or Roman script, in reference to its origin in ancient Rome (though some of the capital letters are Greek in origin). In the context of transliteration, the term «romanization» (British English: «romanisation») is often found.[2][3] Unicode uses the term «Latin»[4] as does the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).[5]

The numeral system is called the Roman numeral system, and the collection of the elements is known as the Roman numerals. The numbers 1, 2, 3 … are Latin/Roman script numbers for the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.

History[edit]

Old Italic alphabet[edit]

| Letters | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | A | B | C | D | E | V | Z | H | Θ | I | K | L | M | N | E | O | P | Ś | Q | R | S | T | Y | X | Φ | Ψ | F |

Archaic Latin alphabet[edit]

| As Old Italic | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Latin | A | B | C | D | E | F | Z | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X |

The letter ⟨C⟩ was the western form of the Greek gamma, but it was used for the sounds /ɡ/ and /k/ alike, possibly under the influence of Etruscan, which might have lacked any voiced plosives. Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the letter ⟨Z⟩ – unneeded to write Latin properly – was replaced with the new letter ⟨G⟩, a ⟨C⟩ modified with a small horizontal stroke, which took its place in the alphabet. From then on, ⟨G⟩ represented the voiced plosive /ɡ/, while ⟨C⟩ was generally reserved for the voiceless plosive /k/. The letter ⟨K⟩ was used only rarely, in a small number of words such as Kalendae, often interchangeably with ⟨C⟩.

Classical Latin alphabet[edit]

After the Roman conquest of Greece in the 1st century BC, Latin adopted the Greek words ⟨Y⟩ and ⟨Z⟩ (or readopted, in the latter case) to write Greek loanwords, placing them at the end of the alphabet. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters did not last. Thus it was during the classical Latin period that the Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:Italic text

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name (majus) | á | bé | cé | dé | é | ef | gé | há | ꟾ | ká | el | em | en | ó | pé | qv́ | er | es | té | v́ | ix | ꟾ graeca | zéta |

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ix | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation (IPA) | aː | beː | keː | deː | eː | ɛf | ɡeː | haː | iː | kaː | ɛl | ɛm | ɛn | oː | peː | kuː | ɛr | ɛs | teː | uː | iks | iː ˈɡraeka | ˈdzeːta |

Medieval and later developments[edit]

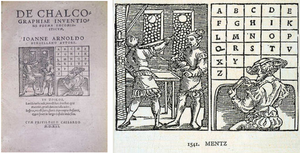

De chalcographiae inventione (1541, Mainz) with the 23 letters. J, U and W are missing.

It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter ⟨W⟩ (originally a ligature of two ⟨V⟩s) was added to the Latin alphabet, to represent sounds from the Germanic languages which did not exist in medieval Latin, and only after the Renaissance did the convention of treating ⟨I⟩ and ⟨U⟩ as vowels, and ⟨J⟩ and ⟨V⟩ as consonants, become established. Prior to that, the former had been merely allographs of the latter.[citation needed]

With the fragmentation of political power, the style of writing changed and varied greatly throughout the Middle Ages, even after the invention of the printing press. Early deviations from the classical forms were the uncial script, a development of the Old Roman cursive, and various so-called minuscule scripts that developed from New Roman cursive, of which the insular script developed by Irish literati & derivations of this, such as Carolingian minuscule were the most influential, introducing the lower case forms of the letters, as well as other writing conventions that have since become standard.

The languages that use the Latin script generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized, whereas Modern English writers and printers of the 17th and 18th century frequently capitalized most and sometimes all nouns[6] – e.g. in the preamble and all of the United States Constitution – a practice still systematically used in Modern German.

ISO basic Latin alphabet[edit]

| Uppercase Latin alphabet | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase Latin alphabet | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

The use of the letters I and V for both consonants and vowels proved inconvenient as the Latin alphabet was adapted to Germanic and Romance languages. W originated as a doubled V (VV) used to represent the Voiced labial–velar approximant /w/ found in Old English as early as the 7th century. It came into common use in the later 11th century, replacing the letter wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩, which had been used for the same sound. In the Romance languages, the minuscule form of V was a rounded u; from this was derived a rounded capital U for the vowel in the 16th century, while a new, pointed minuscule v was derived from V for the consonant. In the case of I, a word-final swash form, j, came to be used for the consonant, with the un-swashed form restricted to vowel use. Such conventions were erratic for centuries. J was introduced into English for the consonant in the 17th century (it had been rare as a vowel), but it was not universally considered a distinct letter in the alphabetic order until the 19th century.

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

Spread[edit]

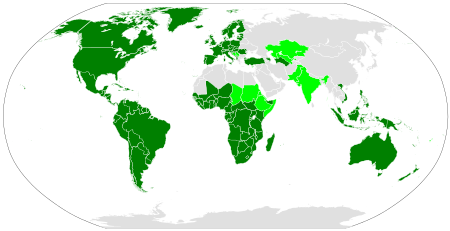

The distribution of the Latin script. The dark green areas show the countries where the Latin script is the sole main script. Light green shows countries where Latin co-exists with other scripts. Latin-script alphabets are sometimes extensively used in areas coloured grey due to the use of unofficial second languages, such as French in Algeria and English in Egypt, and to Latin transliteration of the official script, such as pinyin in China.

The Latin alphabet spread, along with Latin, from the Italian Peninsula to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet.

Middle Ages[edit]

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted by the peoples of Northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets) or Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian.

The Latin script also came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism. The speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted Cyrillic along with Orthodox Christianity. The Serbian language uses both scripts, with Cyrillic predominating in official communication and Latin elsewhere, as determined by the Law on Official Use of the Language and Alphabet.[7]

Since the 16th century[edit]

As late as 1500, the Latin script was limited primarily to the languages spoken in Western, Northern, and Central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of Eastern and Southeastern Europe mostly used Cyrillic, and the Greek alphabet was in use by Greek-speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic script was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Through European colonization the Latin script has spread to the Americas, Oceania, parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, in forms based on the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, German and Dutch alphabets.

It is used for many Austronesian languages, including the languages of the Philippines and the Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. Latin letters served as the basis for the forms of the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah; however, the sound values are completely different.[citation needed]

Under Portuguese missionary influence, a Latin alphabet was devised for the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters. The Latin-based alphabet replaced the Chinese characters in administration in the 19th century with French rule.

Since 19th century[edit]

In the late 19th century, the Romanians switched to the Latin alphabet, which they had used until the Council of Florence in 1439,[8] primarily because Romanian is a Romance language. The Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and their Church, increasingly influenced by Russia after the fall of Byzantine Greek Constantinople in 1453 and capture of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, had begun promoting the Slavic Cyrillic.

Since 20th century[edit]

In 1928, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s reforms, the new Republic of Turkey adopted a Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing a modified Arabic alphabet. Most of the Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and others, had their writing systems replaced by the Latin-based Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s; but, in the 1940s, all were replaced by Cyrillic.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, three of the newly independent Turkic-speaking republics, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, as well as Romanian-speaking Moldova, officially adopted Latin alphabets for their languages. Kyrgyzstan, Iranian-speaking Tajikistan, and the breakaway region of Transnistria kept the Cyrillic alphabet, chiefly due to their close ties with Russia.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of Kurds replaced the Arabic script with two Latin alphabets. Although only the official Kurdish government uses an Arabic alphabet for public documents, the Latin Kurdish alphabet remains widely used throughout the region by the majority of Kurdish-speakers.

In 1957, the People’s Republic of China introduced a script reform to the Zhuang language, changing its orthography from Sawndip, a writing system based on Chinese, to a Latin script alphabet that used a mixture of Latin, Cyrillic, and IPA letters to represent both the phonemes and tones of the Zhuang language, without the use of diacritics. In 1982 this was further standardised to use only Latin script letters.

With the collapse of the Derg and subsequent end of decades of Amharic assimilation in 1991, various ethnic groups in Ethiopia dropped the Geʽez script, which was deemed unsuitable for languages outside of the Semitic branch.[9] In the following years the Kafa,[10] Oromo,[11] Sidama,[12] Somali,[12] and Wolaitta[12] languages switched to Latin while there is continued debate on whether to follow suit for the Hadiyya and Kambaata languages.[13]

21st century[edit]

On 15 September 1999 the authorities of Tatarstan, Russia, passed a law to make the Latin script a co-official writing system alongside Cyrillic for the Tatar language by 2011.[14] A year later, however, the Russian government overruled the law and banned Latinization on its territory.[15]

In 2015, the government of Kazakhstan announced that a Kazakh Latin alphabet would replace the Kazakh Cyrillic alphabet as the official writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.[16] There are also talks about switching from the Cyrillic script to Latin in Ukraine,[17] Kyrgyzstan,[18][19] and Mongolia.[20] Mongolia, however, has since opted to revive the Mongolian script instead of switching to Latin.[21]

In October 2019, the organization National Representational Organization for Inuit in Canada (ITK) announced that they will introduce a unified writing system for the Inuit languages in the country. The writing system is based on the Latin alphabet and is modeled after the one used in the Greenlandic language.[22]

On 12 February 2021 the government of Uzbekistan announced it will finalize the transition from Cyrillic to Latin for the Uzbek language by 2023. Plans to switch to Latin originally began in 1993 but subsequently stalled and Cyrillic remained in widespread use.[23][24]

At present the Crimean Tatar language uses both Cyrillic and Latin. The use of Latin was originally approved by Crimean Tatar representatives after the Soviet Union’s collapse[25] but was never implemented by the regional government. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 the Latin script was dropped entirely. Nevertheless Crimean Tatars outside of Crimea continue to use Latin and on 22 October 2021 the government of Ukraine approved a proposal endorsed by the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People to switch the Crimean Tatar language to Latin by 2025.[26]

In July 2020, 2.6 billion people (36% of the world population) use the Latin alphabet.[27]

International standards[edit]

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage.

As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

National standards[edit]

The DIN standard DIN 91379 specifies a subset of Unicode letters, special characters, and sequences of letters and diacritic signs to allow the correct representation of names and to simplify data exchange in Europe. This specification supports all official languages of European Union countries (thus also Greek and Cyrillic for Bulgarian) as well as the official languages of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, and also the German minority languages. To allow the transliteration of names in other writing systems to the Latin script according to the relevant ISO standards all necessary combinations of base letters and diacritic signs are provided.[28]

Efforts are being made to further develop it into a European CEN standard.[29]

As used by various languages[edit]

In the course of its use, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use in new languages, sometimes representing phonemes not found in languages that were already written with the Roman characters. To represent these new sounds, extensions were therefore created, be it by adding diacritics to existing letters, by joining multiple letters together to make ligatures, by creating completely new forms, or by assigning a special function to pairs or triplets of letters. These new forms are given a place in the alphabet by defining an alphabetical order or collation sequence, which can vary with the particular language.

Letters[edit]

Some examples of new letters to the standard Latin alphabet are the Runic letters wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨Þ þ⟩, and the letter eth ⟨Ð/ð⟩, which were added to the alphabet of Old English. Another Irish letter, the insular g, developed into yogh ⟨Ȝ ȝ⟩, used in Middle English. Wynn was later replaced with the new letter ⟨w⟩, eth and thorn with ⟨th⟩, and yogh with ⟨gh⟩. Although the four are no longer part of the English or Irish alphabets, eth and thorn are still used in the modern Icelandic alphabet, while eth is also used by the Faroese alphabet.

Some West, Central and Southern African languages use a few additional letters that have sound values similar to those of their equivalents in the IPA. For example, Adangme uses the letters ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩, and Ga uses ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩, ⟨Ŋ ŋ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩. Hausa uses ⟨Ɓ ɓ⟩ and ⟨Ɗ ɗ⟩ for implosives, and ⟨Ƙ ƙ⟩ for an ejective. Africanists have standardized these into the African reference alphabet.

Dotted and dotless I — ⟨İ i⟩ and ⟨I ı⟩ — are two forms of the letter I used by the Turkish, Azerbaijani, and Kazakh alphabets.[30] The Azerbaijani language also has ⟨Ə ə⟩, which represents the near-open front unrounded vowel.

Multigraphs[edit]

A digraph is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters in sequence. Examples are ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩, ⟨rh⟩, ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨th⟩ in English, and ⟨ij⟩, ⟨ee⟩, ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨ei⟩ in Dutch. In Dutch the ⟨ij⟩ is capitalized as ⟨IJ⟩ or the ligature ⟨IJ⟩, but never as ⟨Ij⟩, and it often takes the appearance of a ligature ⟨ij⟩ very similar to the letter ⟨ÿ⟩ in handwriting.

A trigraph is made up of three letters, like the German ⟨sch⟩, the Breton ⟨c’h⟩ or the Milanese ⟨oeu⟩. In the orthographies of some languages, digraphs and trigraphs are regarded as independent letters of the alphabet in their own right. The capitalization of digraphs and trigraphs is language-dependent, as only the first letter may be capitalized, or all component letters simultaneously (even for words written in title case, where letters after the digraph or trigraph are left in lowercase).

Ligatures[edit]

A ligature is a fusion of two or more ordinary letters into a new glyph or character. Examples are ⟨Æ æ⟩ (from ⟨AE⟩, called «ash»), ⟨Œ œ⟩ (from ⟨OE⟩, sometimes called «oethel»), the abbreviation ⟨&⟩ (from Latin: et, lit. ‘and’, called «ampersand»), and ⟨ẞ ß⟩ (from ⟨ſʒ⟩ or ⟨ſs⟩, the archaic medial form of ⟨s⟩, followed by an ⟨ʒ⟩ or ⟨s⟩, called «sharp S» or «eszett»).

Diacritics[edit]

A diacritic, in some cases also called an accent, is a small symbol that can appear above or below a letter, or in some other position, such as the umlaut sign used in the German characters ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ or the Romanian characters ă, â, î, ș, ț. Its main function is to change the phonetic value of the letter to which it is added, but it may also modify the pronunciation of a whole syllable or word, indicate the start of a new syllable, or distinguish between homographs such as the Dutch words een (pronounced [ən]) meaning «a» or «an», and één, (pronounced [e:n]) meaning «one». As with the pronunciation of letters, the effect of diacritics is language-dependent.

English is the only major modern European language that requires no diacritics for its native vocabulary[note 1]. Historically, in formal writing, a diaeresis was sometimes used to indicate the start of a new syllable within a sequence of letters that could otherwise be misinterpreted as being a single vowel (e.g., “coöperative”, “reëlect”), but modern writing styles either omit such marks or use a hyphen to indicate a syllable break (e.g. “cooperative”, “re-elect”). [note 2][31]

Collation[edit]

Some modified letters, such as the symbols ⟨å⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ö⟩, may be regarded as new individual letters in themselves, and assigned a specific place in the alphabet for collation purposes, separate from that of the letter on which they are based, as is done in Swedish. In other cases, such as with ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ in German, this is not done; letter-diacritic combinations being identified with their base letter. The same applies to digraphs and trigraphs. Different diacritics may be treated differently in collation within a single language. For example, in Spanish, the character ⟨ñ⟩ is considered a letter, and sorted between ⟨n⟩ and ⟨o⟩ in dictionaries, but the accented vowels ⟨á⟩, ⟨é⟩, ⟨í⟩, ⟨ó⟩, ⟨ú⟩, ⟨ü⟩ are not separated from the unaccented vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩.

Capitalization[edit]

The languages that use the Latin script today generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized; whereas Modern English of the 18th century had frequently all nouns capitalized, in the same way that Modern German is written today, e.g. German: Alle Schwestern der alten Stadt hatten die Vögel gesehen, lit. ‘All of the sisters of the old city had seen the birds’.

Romanization[edit]

Words from languages natively written with other scripts, such as Arabic or Chinese, are usually transliterated or transcribed when embedded in Latin-script text or in multilingual international communication, a process termed Romanization.

Whilst the Romanization of such languages is used mostly at unofficial levels, it has been especially prominent in computer messaging where only the limited seven-bit ASCII code is available on older systems. However, with the introduction of Unicode, Romanization is now becoming less necessary. Note that keyboards used to enter such text may still restrict users to Romanized text, as only ASCII or Latin-alphabet characters may be available.

See also[edit]

- List of languages by writing system#Latin script

- Western Latin character sets (computing)

- European Latin Unicode subset (DIN 91379)

- Latin letters used in mathematics

- Latin omega

Notes[edit]

- ^ In formal English writing, however, diacritics are often preserved on many loanwords, such as «café», «naïve», «façade», «jalapeño» or the German prefix «über-«.

- ^ As an example, an article containing a diaeresis in «coöperate» and a cedilla in «façade» as well as a circumflex in the word «crêpe»: Grafton, Anthony (23 October 2006). «Books: The Nutty Professors, The history of academic charisma». The New Yorker.

- ^ Alongside Chinese and Tamil

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Haarmann 2004, p. 96.

- ^ «Search results | BSI Group». Bsigroup.com. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «Romanisation_systems». Pcgn.org.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «ISO 15924 – Code List in English». Unicode.org. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ «Search – ISO». Iso.org. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521530330 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Zakon O Službenoj Upotrebi Jezika I Pisama» (PDF). Ombudsman.rs. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ «Descriptio_Moldaviae». La.wikisource.org. 1714. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Smith, Lahra (2013). «Review of Making Citizens in Africa: Ethnicity, Gender, and National Identity in Ethiopia«. African Studies. 125 (3): 542–544. doi:10.1080/00083968.2015.1067017. S2CID 148544393 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Pütz, Martin (1997). Language Choices: Conditions, constraints, and consequences. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 216. ISBN 9789027275844.

- ^ Gemeda, Guluma (18 June 2018). «The History and Politics of the Qubee Alphabet». Ayyaantuu. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Yohannes, Mekonnen (2021). «Language Policy in Ethiopia: The Interplay Between Policy and Practice in Tigray Regional State». Language Policy. 24: 33. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63904-4. ISBN 978-3-030-63903-7. S2CID 234114762 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Pasch, Helma (2008). «Competing scripts: The Introduction of the Roman Alphabet in Africa» (PDF). International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 191: 8 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Andrews, Ernest (2018). Language Planning in the Post-Communist Era: The Struggles for Language Control in the New Order in Eastern Europe, Eurasia and China. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-319-70926-0.

- ^ Faller, Helen (2011). Nation, Language, Islam: Tatarstan’s Sovereignty Movement. Central European University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-963-9776-84-5.

- ^ Kazakh language to be converted to Latin alphabet – MCS RK. Inform.kz (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ «Klimkin welcomes discussion on switching to Latin alphabet in Ukraine». UNIAN (27 March 2018).

- ^ «Moscow Bribes Bishkek to Stop Kyrgyzstan From Changing to Latin Alphabet». The Jamestown Organization (12 October 2017).

- ^ «Kyrgyzstan: Latin (alphabet) fever takes hold». Eurasianet (13 September 2019).

- ^ «Russian Influence in Mongolia is Declining». Global Security Review (2 March 2019). 2 March 2019.

- ^ Tang, Didi (20 March 2020). «Mongolia abandons Soviet past by restoring alphabet». The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ «Canadian Inuit Get Common Written Language». High North News (8 October 2019).

- ^ Sands, David (12 February 2021). «Latin lives! Uzbeks prepare latest switch to Western-based alphabet». The Washington Times. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ «Uzbekistan Aims For Full Transition To Latin-Based Alphabet By 2023». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (2007). Ukraine — Crimea — Russia: Triangle of Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-3-8382-5761-7.

- ^ «Cabinet approves Crimean Tatar alphabet based on Latin letters». Ukrinform. 22 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ «The world’s scripts and alphabets». WorldStandards. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ «DIN 91379:2022-08: Characters and defined character sequences in Unicode for the electronic processing of names and data exchange in Europe, with CD-ROM». Beuth Verlag. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^

Koordinierungsstelle für IT-Standards (KoSIT). «String.Latin+ 1.2: eine kommentierte und erweiterte Fassung der DIN SPEC 91379. Inklusive einer umfangreichen Liste häufig gestellter Fragen. Herausgegeben von der Fachgruppe String.Latin. (zip, 1.7 MB)» [String.Latin+ 1.2: Commented and extended version of DIN SPEC 91379.] (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2022. - ^ «Localize Your Font: Turkish i». Glyphs. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ «The New Yorker’s odd mark — the diaeresis». 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

Sources[edit]

- Haarmann, Harald (2004). Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

Further reading[edit]

- Boyle, Leonard E. 1976. «Optimist and recensionist: ‘Common errors’ or ‘common variations.'» In Latin script and letters A.D. 400–900: Festschrift presented to Ludwig Bieler on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Edited by John J. O’Meara and Bernd Naumann, 264–74. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Morison, Stanley. 1972. Politics and script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. Oxford: Clarendon.

External links[edit]

- Unicode collation chart—Latin letters sorted by shape

- Diacritics Project – All you need to design a font with correct accents

For the Latin script originally used by the ancient Romans to write Latin, see Latin alphabet.

| Latin

Roman |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c. 700 BC – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

Official script in: 132 sovereign states

Co-official script in: 15 sovereign states

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

|

Child systems |

|

|

Sister systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

See Latin characters in Unicode |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern Italy (Magna Grecia). It was adopted by the Etruscans and subsequently by the Romans. Several Latin-script alphabets exist, which differ in graphemes, collation and phonetic values from the classical Latin alphabet.

The Latin script is the basis of the International Phonetic Alphabet, and the 26 most widespread letters are the letters contained in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

Latin script is the basis for the largest number of alphabets of any writing system[1] and is the

most widely adopted writing system in the world. Latin script is used as the standard method of writing for most Western and Central, and some Eastern, European languages as well as many languages in other parts of the world.

Name[edit]

The script is either called Latin script or Roman script, in reference to its origin in ancient Rome (though some of the capital letters are Greek in origin). In the context of transliteration, the term «romanization» (British English: «romanisation») is often found.[2][3] Unicode uses the term «Latin»[4] as does the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).[5]

The numeral system is called the Roman numeral system, and the collection of the elements is known as the Roman numerals. The numbers 1, 2, 3 … are Latin/Roman script numbers for the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.

History[edit]

Old Italic alphabet[edit]

| Letters | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | A | B | C | D | E | V | Z | H | Θ | I | K | L | M | N | E | O | P | Ś | Q | R | S | T | Y | X | Φ | Ψ | F |

Archaic Latin alphabet[edit]

| As Old Italic | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Latin | A | B | C | D | E | F | Z | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X |

The letter ⟨C⟩ was the western form of the Greek gamma, but it was used for the sounds /ɡ/ and /k/ alike, possibly under the influence of Etruscan, which might have lacked any voiced plosives. Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the letter ⟨Z⟩ – unneeded to write Latin properly – was replaced with the new letter ⟨G⟩, a ⟨C⟩ modified with a small horizontal stroke, which took its place in the alphabet. From then on, ⟨G⟩ represented the voiced plosive /ɡ/, while ⟨C⟩ was generally reserved for the voiceless plosive /k/. The letter ⟨K⟩ was used only rarely, in a small number of words such as Kalendae, often interchangeably with ⟨C⟩.

Classical Latin alphabet[edit]

After the Roman conquest of Greece in the 1st century BC, Latin adopted the Greek words ⟨Y⟩ and ⟨Z⟩ (or readopted, in the latter case) to write Greek loanwords, placing them at the end of the alphabet. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters did not last. Thus it was during the classical Latin period that the Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:Italic text

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name (majus) | á | bé | cé | dé | é | ef | gé | há | ꟾ | ká | el | em | en | ó | pé | qv́ | er | es | té | v́ | ix | ꟾ graeca | zéta |

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ix | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation (IPA) | aː | beː | keː | deː | eː | ɛf | ɡeː | haː | iː | kaː | ɛl | ɛm | ɛn | oː | peː | kuː | ɛr | ɛs | teː | uː | iks | iː ˈɡraeka | ˈdzeːta |

Medieval and later developments[edit]

De chalcographiae inventione (1541, Mainz) with the 23 letters. J, U and W are missing.

It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter ⟨W⟩ (originally a ligature of two ⟨V⟩s) was added to the Latin alphabet, to represent sounds from the Germanic languages which did not exist in medieval Latin, and only after the Renaissance did the convention of treating ⟨I⟩ and ⟨U⟩ as vowels, and ⟨J⟩ and ⟨V⟩ as consonants, become established. Prior to that, the former had been merely allographs of the latter.[citation needed]

With the fragmentation of political power, the style of writing changed and varied greatly throughout the Middle Ages, even after the invention of the printing press. Early deviations from the classical forms were the uncial script, a development of the Old Roman cursive, and various so-called minuscule scripts that developed from New Roman cursive, of which the insular script developed by Irish literati & derivations of this, such as Carolingian minuscule were the most influential, introducing the lower case forms of the letters, as well as other writing conventions that have since become standard.

The languages that use the Latin script generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized, whereas Modern English writers and printers of the 17th and 18th century frequently capitalized most and sometimes all nouns[6] – e.g. in the preamble and all of the United States Constitution – a practice still systematically used in Modern German.

ISO basic Latin alphabet[edit]

| Uppercase Latin alphabet | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase Latin alphabet | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

The use of the letters I and V for both consonants and vowels proved inconvenient as the Latin alphabet was adapted to Germanic and Romance languages. W originated as a doubled V (VV) used to represent the Voiced labial–velar approximant /w/ found in Old English as early as the 7th century. It came into common use in the later 11th century, replacing the letter wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩, which had been used for the same sound. In the Romance languages, the minuscule form of V was a rounded u; from this was derived a rounded capital U for the vowel in the 16th century, while a new, pointed minuscule v was derived from V for the consonant. In the case of I, a word-final swash form, j, came to be used for the consonant, with the un-swashed form restricted to vowel use. Such conventions were erratic for centuries. J was introduced into English for the consonant in the 17th century (it had been rare as a vowel), but it was not universally considered a distinct letter in the alphabetic order until the 19th century.

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

Spread[edit]

The distribution of the Latin script. The dark green areas show the countries where the Latin script is the sole main script. Light green shows countries where Latin co-exists with other scripts. Latin-script alphabets are sometimes extensively used in areas coloured grey due to the use of unofficial second languages, such as French in Algeria and English in Egypt, and to Latin transliteration of the official script, such as pinyin in China.

The Latin alphabet spread, along with Latin, from the Italian Peninsula to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet.

Middle Ages[edit]

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted by the peoples of Northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets) or Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian.

The Latin script also came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism. The speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted Cyrillic along with Orthodox Christianity. The Serbian language uses both scripts, with Cyrillic predominating in official communication and Latin elsewhere, as determined by the Law on Official Use of the Language and Alphabet.[7]

Since the 16th century[edit]

As late as 1500, the Latin script was limited primarily to the languages spoken in Western, Northern, and Central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of Eastern and Southeastern Europe mostly used Cyrillic, and the Greek alphabet was in use by Greek-speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic script was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Through European colonization the Latin script has spread to the Americas, Oceania, parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, in forms based on the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, German and Dutch alphabets.

It is used for many Austronesian languages, including the languages of the Philippines and the Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. Latin letters served as the basis for the forms of the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah; however, the sound values are completely different.[citation needed]

Under Portuguese missionary influence, a Latin alphabet was devised for the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters. The Latin-based alphabet replaced the Chinese characters in administration in the 19th century with French rule.

Since 19th century[edit]

In the late 19th century, the Romanians switched to the Latin alphabet, which they had used until the Council of Florence in 1439,[8] primarily because Romanian is a Romance language. The Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and their Church, increasingly influenced by Russia after the fall of Byzantine Greek Constantinople in 1453 and capture of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, had begun promoting the Slavic Cyrillic.

Since 20th century[edit]

In 1928, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s reforms, the new Republic of Turkey adopted a Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing a modified Arabic alphabet. Most of the Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and others, had their writing systems replaced by the Latin-based Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s; but, in the 1940s, all were replaced by Cyrillic.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, three of the newly independent Turkic-speaking republics, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, as well as Romanian-speaking Moldova, officially adopted Latin alphabets for their languages. Kyrgyzstan, Iranian-speaking Tajikistan, and the breakaway region of Transnistria kept the Cyrillic alphabet, chiefly due to their close ties with Russia.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of Kurds replaced the Arabic script with two Latin alphabets. Although only the official Kurdish government uses an Arabic alphabet for public documents, the Latin Kurdish alphabet remains widely used throughout the region by the majority of Kurdish-speakers.

In 1957, the People’s Republic of China introduced a script reform to the Zhuang language, changing its orthography from Sawndip, a writing system based on Chinese, to a Latin script alphabet that used a mixture of Latin, Cyrillic, and IPA letters to represent both the phonemes and tones of the Zhuang language, without the use of diacritics. In 1982 this was further standardised to use only Latin script letters.

With the collapse of the Derg and subsequent end of decades of Amharic assimilation in 1991, various ethnic groups in Ethiopia dropped the Geʽez script, which was deemed unsuitable for languages outside of the Semitic branch.[9] In the following years the Kafa,[10] Oromo,[11] Sidama,[12] Somali,[12] and Wolaitta[12] languages switched to Latin while there is continued debate on whether to follow suit for the Hadiyya and Kambaata languages.[13]

21st century[edit]

On 15 September 1999 the authorities of Tatarstan, Russia, passed a law to make the Latin script a co-official writing system alongside Cyrillic for the Tatar language by 2011.[14] A year later, however, the Russian government overruled the law and banned Latinization on its territory.[15]

In 2015, the government of Kazakhstan announced that a Kazakh Latin alphabet would replace the Kazakh Cyrillic alphabet as the official writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.[16] There are also talks about switching from the Cyrillic script to Latin in Ukraine,[17] Kyrgyzstan,[18][19] and Mongolia.[20] Mongolia, however, has since opted to revive the Mongolian script instead of switching to Latin.[21]

In October 2019, the organization National Representational Organization for Inuit in Canada (ITK) announced that they will introduce a unified writing system for the Inuit languages in the country. The writing system is based on the Latin alphabet and is modeled after the one used in the Greenlandic language.[22]

On 12 February 2021 the government of Uzbekistan announced it will finalize the transition from Cyrillic to Latin for the Uzbek language by 2023. Plans to switch to Latin originally began in 1993 but subsequently stalled and Cyrillic remained in widespread use.[23][24]

At present the Crimean Tatar language uses both Cyrillic and Latin. The use of Latin was originally approved by Crimean Tatar representatives after the Soviet Union’s collapse[25] but was never implemented by the regional government. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 the Latin script was dropped entirely. Nevertheless Crimean Tatars outside of Crimea continue to use Latin and on 22 October 2021 the government of Ukraine approved a proposal endorsed by the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People to switch the Crimean Tatar language to Latin by 2025.[26]

In July 2020, 2.6 billion people (36% of the world population) use the Latin alphabet.[27]

International standards[edit]

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage.

As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

National standards[edit]

The DIN standard DIN 91379 specifies a subset of Unicode letters, special characters, and sequences of letters and diacritic signs to allow the correct representation of names and to simplify data exchange in Europe. This specification supports all official languages of European Union countries (thus also Greek and Cyrillic for Bulgarian) as well as the official languages of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, and also the German minority languages. To allow the transliteration of names in other writing systems to the Latin script according to the relevant ISO standards all necessary combinations of base letters and diacritic signs are provided.[28]

Efforts are being made to further develop it into a European CEN standard.[29]

As used by various languages[edit]

In the course of its use, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use in new languages, sometimes representing phonemes not found in languages that were already written with the Roman characters. To represent these new sounds, extensions were therefore created, be it by adding diacritics to existing letters, by joining multiple letters together to make ligatures, by creating completely new forms, or by assigning a special function to pairs or triplets of letters. These new forms are given a place in the alphabet by defining an alphabetical order or collation sequence, which can vary with the particular language.

Letters[edit]

Some examples of new letters to the standard Latin alphabet are the Runic letters wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨Þ þ⟩, and the letter eth ⟨Ð/ð⟩, which were added to the alphabet of Old English. Another Irish letter, the insular g, developed into yogh ⟨Ȝ ȝ⟩, used in Middle English. Wynn was later replaced with the new letter ⟨w⟩, eth and thorn with ⟨th⟩, and yogh with ⟨gh⟩. Although the four are no longer part of the English or Irish alphabets, eth and thorn are still used in the modern Icelandic alphabet, while eth is also used by the Faroese alphabet.

Some West, Central and Southern African languages use a few additional letters that have sound values similar to those of their equivalents in the IPA. For example, Adangme uses the letters ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩, and Ga uses ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩, ⟨Ŋ ŋ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩. Hausa uses ⟨Ɓ ɓ⟩ and ⟨Ɗ ɗ⟩ for implosives, and ⟨Ƙ ƙ⟩ for an ejective. Africanists have standardized these into the African reference alphabet.

Dotted and dotless I — ⟨İ i⟩ and ⟨I ı⟩ — are two forms of the letter I used by the Turkish, Azerbaijani, and Kazakh alphabets.[30] The Azerbaijani language also has ⟨Ə ə⟩, which represents the near-open front unrounded vowel.

Multigraphs[edit]

A digraph is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters in sequence. Examples are ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩, ⟨rh⟩, ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨th⟩ in English, and ⟨ij⟩, ⟨ee⟩, ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨ei⟩ in Dutch. In Dutch the ⟨ij⟩ is capitalized as ⟨IJ⟩ or the ligature ⟨IJ⟩, but never as ⟨Ij⟩, and it often takes the appearance of a ligature ⟨ij⟩ very similar to the letter ⟨ÿ⟩ in handwriting.

A trigraph is made up of three letters, like the German ⟨sch⟩, the Breton ⟨c’h⟩ or the Milanese ⟨oeu⟩. In the orthographies of some languages, digraphs and trigraphs are regarded as independent letters of the alphabet in their own right. The capitalization of digraphs and trigraphs is language-dependent, as only the first letter may be capitalized, or all component letters simultaneously (even for words written in title case, where letters after the digraph or trigraph are left in lowercase).

Ligatures[edit]

A ligature is a fusion of two or more ordinary letters into a new glyph or character. Examples are ⟨Æ æ⟩ (from ⟨AE⟩, called «ash»), ⟨Œ œ⟩ (from ⟨OE⟩, sometimes called «oethel»), the abbreviation ⟨&⟩ (from Latin: et, lit. ‘and’, called «ampersand»), and ⟨ẞ ß⟩ (from ⟨ſʒ⟩ or ⟨ſs⟩, the archaic medial form of ⟨s⟩, followed by an ⟨ʒ⟩ or ⟨s⟩, called «sharp S» or «eszett»).

Diacritics[edit]

A diacritic, in some cases also called an accent, is a small symbol that can appear above or below a letter, or in some other position, such as the umlaut sign used in the German characters ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ or the Romanian characters ă, â, î, ș, ț. Its main function is to change the phonetic value of the letter to which it is added, but it may also modify the pronunciation of a whole syllable or word, indicate the start of a new syllable, or distinguish between homographs such as the Dutch words een (pronounced [ən]) meaning «a» or «an», and één, (pronounced [e:n]) meaning «one». As with the pronunciation of letters, the effect of diacritics is language-dependent.

English is the only major modern European language that requires no diacritics for its native vocabulary[note 1]. Historically, in formal writing, a diaeresis was sometimes used to indicate the start of a new syllable within a sequence of letters that could otherwise be misinterpreted as being a single vowel (e.g., “coöperative”, “reëlect”), but modern writing styles either omit such marks or use a hyphen to indicate a syllable break (e.g. “cooperative”, “re-elect”). [note 2][31]

Collation[edit]

Some modified letters, such as the symbols ⟨å⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ö⟩, may be regarded as new individual letters in themselves, and assigned a specific place in the alphabet for collation purposes, separate from that of the letter on which they are based, as is done in Swedish. In other cases, such as with ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ in German, this is not done; letter-diacritic combinations being identified with their base letter. The same applies to digraphs and trigraphs. Different diacritics may be treated differently in collation within a single language. For example, in Spanish, the character ⟨ñ⟩ is considered a letter, and sorted between ⟨n⟩ and ⟨o⟩ in dictionaries, but the accented vowels ⟨á⟩, ⟨é⟩, ⟨í⟩, ⟨ó⟩, ⟨ú⟩, ⟨ü⟩ are not separated from the unaccented vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩.

Capitalization[edit]

The languages that use the Latin script today generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized; whereas Modern English of the 18th century had frequently all nouns capitalized, in the same way that Modern German is written today, e.g. German: Alle Schwestern der alten Stadt hatten die Vögel gesehen, lit. ‘All of the sisters of the old city had seen the birds’.

Romanization[edit]

Words from languages natively written with other scripts, such as Arabic or Chinese, are usually transliterated or transcribed when embedded in Latin-script text or in multilingual international communication, a process termed Romanization.

Whilst the Romanization of such languages is used mostly at unofficial levels, it has been especially prominent in computer messaging where only the limited seven-bit ASCII code is available on older systems. However, with the introduction of Unicode, Romanization is now becoming less necessary. Note that keyboards used to enter such text may still restrict users to Romanized text, as only ASCII or Latin-alphabet characters may be available.

See also[edit]

- List of languages by writing system#Latin script

- Western Latin character sets (computing)

- European Latin Unicode subset (DIN 91379)

- Latin letters used in mathematics

- Latin omega

Notes[edit]

- ^ In formal English writing, however, diacritics are often preserved on many loanwords, such as «café», «naïve», «façade», «jalapeño» or the German prefix «über-«.

- ^ As an example, an article containing a diaeresis in «coöperate» and a cedilla in «façade» as well as a circumflex in the word «crêpe»: Grafton, Anthony (23 October 2006). «Books: The Nutty Professors, The history of academic charisma». The New Yorker.

- ^ Alongside Chinese and Tamil

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Haarmann 2004, p. 96.

- ^ «Search results | BSI Group». Bsigroup.com. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «Romanisation_systems». Pcgn.org.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «ISO 15924 – Code List in English». Unicode.org. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ «Search – ISO». Iso.org. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521530330 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Zakon O Službenoj Upotrebi Jezika I Pisama» (PDF). Ombudsman.rs. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ «Descriptio_Moldaviae». La.wikisource.org. 1714. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Smith, Lahra (2013). «Review of Making Citizens in Africa: Ethnicity, Gender, and National Identity in Ethiopia«. African Studies. 125 (3): 542–544. doi:10.1080/00083968.2015.1067017. S2CID 148544393 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Pütz, Martin (1997). Language Choices: Conditions, constraints, and consequences. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 216. ISBN 9789027275844.

- ^ Gemeda, Guluma (18 June 2018). «The History and Politics of the Qubee Alphabet». Ayyaantuu. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Yohannes, Mekonnen (2021). «Language Policy in Ethiopia: The Interplay Between Policy and Practice in Tigray Regional State». Language Policy. 24: 33. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63904-4. ISBN 978-3-030-63903-7. S2CID 234114762 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Pasch, Helma (2008). «Competing scripts: The Introduction of the Roman Alphabet in Africa» (PDF). International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 191: 8 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Andrews, Ernest (2018). Language Planning in the Post-Communist Era: The Struggles for Language Control in the New Order in Eastern Europe, Eurasia and China. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-319-70926-0.

- ^ Faller, Helen (2011). Nation, Language, Islam: Tatarstan’s Sovereignty Movement. Central European University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-963-9776-84-5.

- ^ Kazakh language to be converted to Latin alphabet – MCS RK. Inform.kz (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ «Klimkin welcomes discussion on switching to Latin alphabet in Ukraine». UNIAN (27 March 2018).

- ^ «Moscow Bribes Bishkek to Stop Kyrgyzstan From Changing to Latin Alphabet». The Jamestown Organization (12 October 2017).

- ^ «Kyrgyzstan: Latin (alphabet) fever takes hold». Eurasianet (13 September 2019).

- ^ «Russian Influence in Mongolia is Declining». Global Security Review (2 March 2019). 2 March 2019.

- ^ Tang, Didi (20 March 2020). «Mongolia abandons Soviet past by restoring alphabet». The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ «Canadian Inuit Get Common Written Language». High North News (8 October 2019).

- ^ Sands, David (12 February 2021). «Latin lives! Uzbeks prepare latest switch to Western-based alphabet». The Washington Times. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ «Uzbekistan Aims For Full Transition To Latin-Based Alphabet By 2023». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (2007). Ukraine — Crimea — Russia: Triangle of Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-3-8382-5761-7.

- ^ «Cabinet approves Crimean Tatar alphabet based on Latin letters». Ukrinform. 22 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ «The world’s scripts and alphabets». WorldStandards. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ «DIN 91379:2022-08: Characters and defined character sequences in Unicode for the electronic processing of names and data exchange in Europe, with CD-ROM». Beuth Verlag. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^

Koordinierungsstelle für IT-Standards (KoSIT). «String.Latin+ 1.2: eine kommentierte und erweiterte Fassung der DIN SPEC 91379. Inklusive einer umfangreichen Liste häufig gestellter Fragen. Herausgegeben von der Fachgruppe String.Latin. (zip, 1.7 MB)» [String.Latin+ 1.2: Commented and extended version of DIN SPEC 91379.] (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2022. - ^ «Localize Your Font: Turkish i». Glyphs. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ «The New Yorker’s odd mark — the diaeresis». 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

Sources[edit]

- Haarmann, Harald (2004). Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

Further reading[edit]

- Boyle, Leonard E. 1976. «Optimist and recensionist: ‘Common errors’ or ‘common variations.'» In Latin script and letters A.D. 400–900: Festschrift presented to Ludwig Bieler on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Edited by John J. O’Meara and Bernd Naumann, 264–74. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Morison, Stanley. 1972. Politics and script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. Oxford: Clarendon.

External links[edit]

- Unicode collation chart—Latin letters sorted by shape

- Diacritics Project – All you need to design a font with correct accents

В процессе работы с текстовым редактором Microsoft Word пользователям приходится сталкиваться с разнообразными заданиями и трудностями. Некоторые из них могут быть достаточно банальными. Довольно часто пользователи интересуются, как поставить римские цифры в Word. Этому вопросу и посвящена данная статья. Давайте разбираться. Поехали!

Римские буквы на латинской раскладке

Чтобы написать римские цифры, можно использовать сразу 7 латинских букв. Они записываются в определённой последовательности, что продиктовано соответствующими правилами.

Речь идёт о таких цифрах на латинской раскладке, которые являются аналогом римских символов:

- I означает 1;

- V используется как 5;

- X — это 10;

- L — 50;

- C — 100;

- D — 500;

- M — это 1000.

Если поставить III подряд, это будет 3. А VIII означает уже 8.

Есть специальные правила, которые позволяют разобраться в правилах написания римских букв с помощью латиницы. Используются большие прописные буквы.

Довольно простой метод. Но в основном используется при знании принципов расстановки символов в римских цифрах. Допустим, далеко не все знают, как правильно написать 1947. Поэтому есть и альтернативные решения.

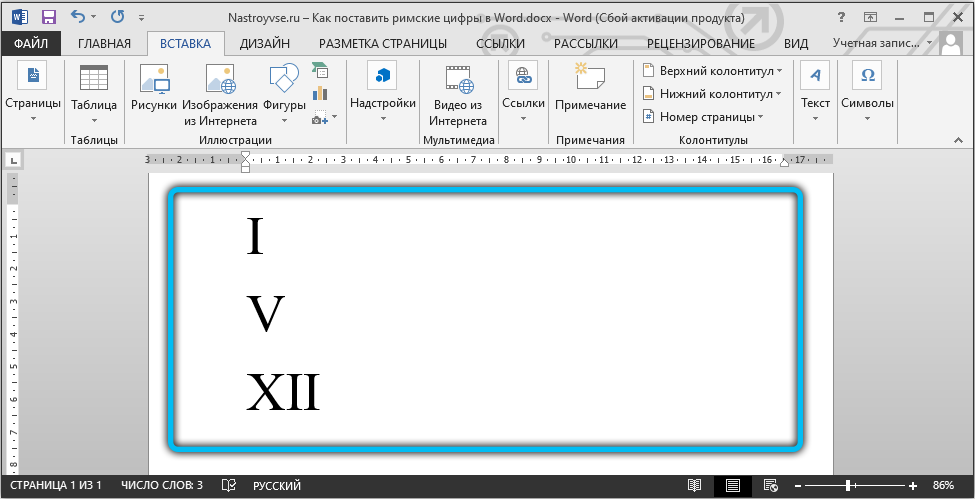

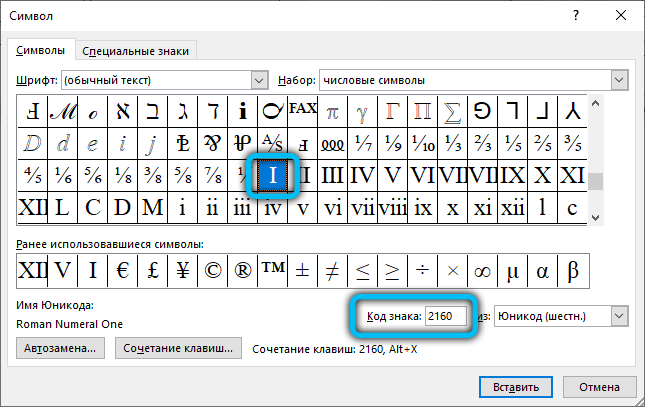

Использование символов

Если вы не хотите использовать латиницу для записи римским символов, тогда можно воспользоваться возможностями встроенной библиотеки текстового редактора Word. Она есть во всех версиях этого приложения.

Для этого нужно сделать следующее:

Аналогичное действие с выделением и вставкой повторяйте для всех последующих необходимых символов.

Преимущество метода в сравнении с предыдущим заключается в том, что здесь цифры римского значения можно вставлять за один раз.

Минус в самом процессе вставки. Приходится открывать множество разных окон, чтобы попасть в нужное меню. Но многим такой вариант подходит.

Будьте внимательными, поскольку набор римских цифр в библиотеке доступен не для всех шрифтов, которые предлагает редактор Word. Если вы выполнили эту инструкцию, но римских чисел и цифр там не оказалось, тогда нужно сделать следующее. Закройте это окно, поменяйте шрифт в текстовом редакторе и повторите процедуру.

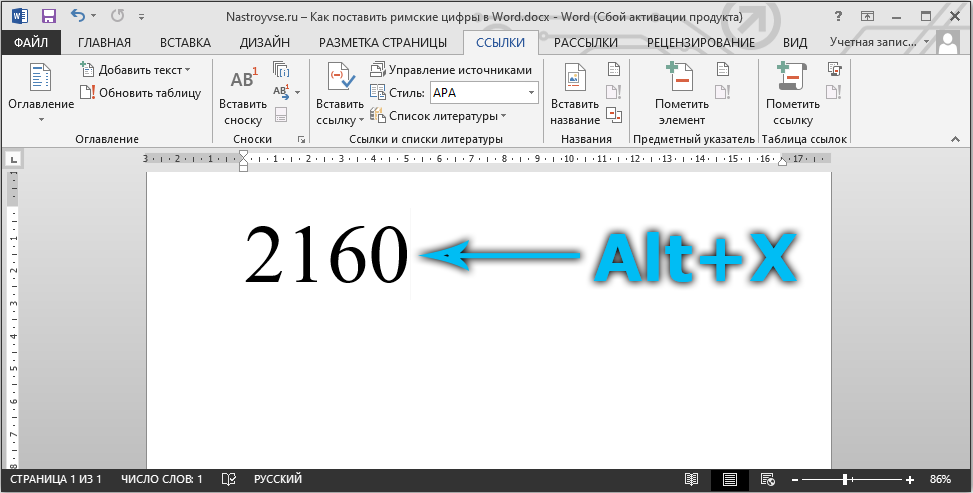

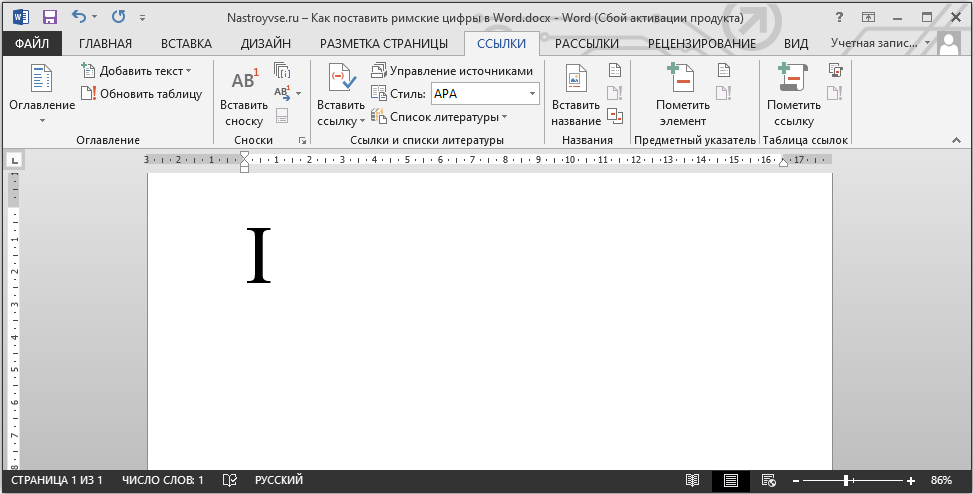

Преобразование кода