Загрузить PDF

Загрузить PDF

Японские иероглифы очень красивы и сложны, и вам придется нелегко, если вы решите быстро научиться читать и писать по-японски. Однако несмотря на то, что иероглифов (кандзи) более 50 тысяч, вам не нужно осваивать их все. Большинство носителей японского языка знают лишь фонетическое написание слов и всего около 6000 кандзи. На то, чтобы научиться быстро читать или писать по-японски, могут уйти годы, однако основы японского можно изучить довольно быстро, если вы будете знать, как правильно организовать занятия.

-

1

Начните читать тексты на японском, написанные для детей. Лучше начинать не со сложных текстов, которые потребуют глубокого знания иероглифов, а с книг, которые помогут вам освоить хирагану и катакану.

- Можно начать с переводных книг Диснея. Вы сможете сравнивать перевод с оригинальным текстом, и так вам будет проще уловить структуру предложений.

- Когда будете изучать хирагану, поищите книги Мари Такабаяши. Ее книги для детей написаны полностью с помощью хираганы, однако они не так просты, как кажутся.

- «Гури и Гура» – это еще одна известная детская книжная серия, к которой вы сможете перейти, когда освоите азы. Эти книги помогут вам расширить словарный запас.

- Попробуйте почитать мангу. Когда вам станет легче понимать детские книги, попробуйте взяться за мангу – там тексты будут сложнее.

-

2

Изучите основы японской грамматики и построения предложений. Сначала вам будет сложно читать по-японски, потому что между иероглифами нет пробелов.

- Структура предложений в японском отличается от привычной структуры русского языка. Если по-русски мы говорим «Я пью воду», по-японски это будет звучать как «Я воду пью». После подлежащего или дополнения также должны ставиться определенные символы.

-

3

Беритесь за одну тему за раз. Прочитать первую страницу книги на японском может быть крайне сложно, но не отступайте от своего плана. Слова в тексте могут повторяться, и чем чаще вы будете встречать эти слова, тем быстрее вы будете читать.[1]

- Выбирайте темы, которые вам нравятся. Если вы увлекаетесь музыкой, купите книги на эту тему той сложности, которая соответствует вашему уровню владения языком. Если тема вам интересна, вы будете с большим рвением читать и осваивать язык.

-

4

Не тратьте время на то, чтобы научиться говорить на японском. Если ваша цель – научиться читать и писать быстро, попытки научиться говорить (аудиоуроки или курсы) замедлят ваш прогресс. Можно освоить язык и не говорить на нем. Поскольку в иероглифах заключаются определенные значения, совершенно не важно, умеете вы произносить их или нет. Важно лишь то, знаете ли вы значение иероглифа и то, как его нужно употреблять.

- Лучше не тратить время на улучшение навыков говорения, а посвятить себя изучению кандзи, грамматики и написанию иероглифов.

-

5

Включайте японские субтитры. Смотрите сериалы и фильмы на своем родном языке и включайте японские субтитры. Постепенно вы сможете приглушать звук и читать иероглифы. Сначала читать будет сложно, однако изображение на экране поможет вам понять смысл происходящего.

-

6

Расширяйте свой словарный запас с помощью Дзее Кандзи. Большинство слов в японском языке – это кандзи, заимствованные из китайского. Дзее Кандзи – это список из 2136 китайских иероглифов, которые японское правительство считает самыми важными для понимания японского языка.[2]

- Ведите блог о кандзи. На то чтобы изучить иероглифы, может уйти много лет. С помощью блога вам будет проще возвращаться к пройденному материалу и вспоминать выученные слова.[3]

- Наберитесь терпения. Чтобы освоить кандзи, нужно много времени и усилий.

Реклама

- Ведите блог о кандзи. На то чтобы изучить иероглифы, может уйти много лет. С помощью блога вам будет проще возвращаться к пройденному материалу и вспоминать выученные слова.[3]

-

1

Изучите хирагану. Хирагана – это фонетическое письмо, которое используется в японском языке. Поскольку оно охватывает все звуки, которые есть в языке, на хирагане можно записать все, что угодно.

- В хирагане есть 46 символов.[4]

Они обозначают гласные или гласные в сочетании с согласными.[5]

- Используйте хирагану для записи частиц и выражений либо слов, которые встречаются редко или могут быть неизвестны читателю.[6]

- Сделайте карточки со всеми иероглифами и запишите звуки, которые они обозначают, на обратной стороне. Один или два раза в день пересматривайте все карточки и произносите звуки. Затем попробуйте смотреть на запись звука и записывать соответствующий символ.

- В хирагане есть 46 символов.[4]

-

2

Изучите катакану. Катакана состоит из 46 символов,[7]

которые обозначают те же звуки, что и в хирагане, однако они используются для обозначения таких понятий, как Америка, Моцарт или Хэллоуин.- Поскольку в японском языке нет длинных гласных, все длинные гласные обозначаются тире после символа. К примеру, «ケーキ» – это обозначение английского слова «cake» (пирог). Тире обозначает длинный гласный звук в середине слова.[8]

- Хирагану и катакану можно освоить за несколько недель при ежедневных занятиях по несколько часов.

- Поскольку в японском языке нет длинных гласных, все длинные гласные обозначаются тире после символа. К примеру, «ケーキ» – это обозначение английского слова «cake» (пирог). Тире обозначает длинный гласный звук в середине слова.[8]

-

3

Изучите рукописные шрифты. Буква «а», написанная от руки, выглядит на экране компьютера иначе. Точно так же и в японском языке многие компьютерные шрифты отличаются от рукописных символов.

- Запоминайте. Лучший способ выучить все – это по 30-60 минут в день запоминать и писать иероглифы.

- Проверяйте себя. Чтобы проверить, заучили ли вы хирагану и катакану, попробуйте записать наборы звуков по памяти. Если вы не можете воспроизвести их, начните учить их заново. Составьте список всех японских звуков, затем найдите им соответствия в хирагане и катакане. Тренируйтесь ежедневно до тех пор, пока не сможете вспомнить по 46 символов для каждой азбуки.

-

4

Используйте кандзи, но только тогда, когда это действительно необходимо. Кандзи позволяют сократить объем текста, однако эти иероглифы используются редко даже носителями языка. Вы должны быть уверены, что читатель знает тот или иной иероглиф. Если вы знаете слово, но не знаете соответствующий иероглиф, вы можете записать его фонетически с помощью хираганы.

-

5

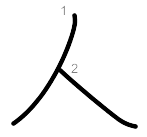

Рисуйте черточки в правильном порядке.[9]

Это может показаться неважным, однако правильный порядок написания черточек может ускорить процесс написания символов, будь то хирагана, катакана или кандзи.- Пишите иероглифы сверху вниз, слева направо.

- Вначале рисуйте горизонтальные черточки, затем вертикальные.

- Проводите черточки от центра в стороны.

- Точки и мелкие черточки следует ставить в конце.

- Изучите правильный наклон для всех черточек.

-

6

Напишите предложение. Оно не должно быть сложным – можно просто написать «Я мальчик» или «Я девочка».

- Пишите на хирагане, если только вам не нужно использовать заимствованные слова. Можно писать либо горизонтально (то есть слева направо, как в русском), или вертикально, что является более традиционным способом (снизу вверх, справа налево).

- Записывайте существительные, прилагательные и глаголы с помощью кандзи. Большинство слов в японском – это кандзи, заимствованные из китайского.[10]

Очень важно следить за тем, чтобы вы всегда использовали именно тот иероглиф, который имеете в виду.

-

7

Не используйте ромадзи. Вам может показаться, что писать японские слова латиницей гораздо проще, однако сами японцы так не делают, и так вы рискуете только запутать читателя.[11]

Поскольку в японском языке много омонимов, ромадзи – не самый удобный способ выражения своих мыслей или чтения. -

8

Чтобы писать быстрее, пишите курсивом или полукурсивом. Когда запомните, в каком порядке изображаются элементы иероглифов, начните писать символы курсивом или полукурсивом. Старайтесь как можно реже отрывать карандаш или ручку от бумаги. Поскольку вы уже знаете, в каком порядке нужно рисовать черточки, вы можете просто слабее давить на ручку между черточками, и символы будут получаться аккуратными.

- Как и в любом другом языке, при письме некоторые символы упрощаются.[12]

Конечно, не стоит делать иероглифы практически нечитаемыми, однако чаще всего контекст позволит читателю правильно понять, что вы хотели сказать.

Реклама

- Как и в любом другом языке, при письме некоторые символы упрощаются.[12]

-

1

Научитесь здороваться. こんにちは означает «здравствуйте». Фраза произносится как конничи ва.

- お早うございます означает «доброе утро», произносится как охайо гозаймасу.

- こんばんは означает «добрый вечер», произносится как конбон ву.

- お休みなさい означает «спокойной ночи», произносится как оясуми насай.

- さようなら означает «до свидания», произносится как сайонара.

-

2

Говорите спасибо как можно чаще. ありがとうございます означает «большое спасибо», произносится как аригато гозаймасу.

- Если кто-то благодарит вас, ответьте. どういたしまして означает «пожалуйста», произносится как до иташимашите.

-

3

Спросите человека, как у него дела. お元気ですか означает «как дела?», произносится как огенки десу ка?

- Если кто-то спрашивает, как у вас дела, ответьте, что все хорошо. 元気です означает «все хорошо», произносится как генки десу.

-

4

Представьтесь. 私の名前は означает «меня зовут …», произносится как ваташи но намае ва.

-

5

Запомните направления движения.[13]

Важно знать, как попасть туда, куда вам нужно.- ますぐ(масугу) означает «вперед».

- 右(миги) означает «направо».

- 左(хидари) означает «налево».

Реклама

Советы

- Подберите подходящее время для занятий. Одним лучше заниматься утром, другим вечером перед сном.

- Поищите словарь с латиницей – он может пригодиться вам, однако не стоит полностью полагаться на латиницу.

- Поищите нужные вам книги к библиотеке и книжных магазинах.

- Если записаться на курсы, вы быстрее освоите язык, однако там много внимания будет уделяться устной речи.

- Используйте приложения для изучения японского языка.

- Поищите человека, который хорошо владеет языком, возможно, даже носителя японского языка. Скорее всего, он с радостью поможет вам.

- Постарайтесь заниматься там, где вас не будет ничего отвлекать.

- Занимайтесь понемногу, но часто, и вы добьетесь желаемого результата.

Реклама

Что вам понадобится

- Тетрадь

- Словарь

Об этой статье

Эту страницу просматривали 70 538 раз.

Была ли эта статья полезной?

Японский язык: хирагана, каткана, иероглифы кандзи. Наша статья расскажет про японское письмо и подскажет начинающим, как выучить японские иероглифы и азбуки.

Konnichiwa, дорогие друзья! Начиная изучение японского языка, вы сразу сталкиваетесь с двумя слоговыми азбуками и иероглифами. Давайте разберем, что же такое катакана и хирагана, как они связаны с кандзи, откуда все они появились и чем различаются.

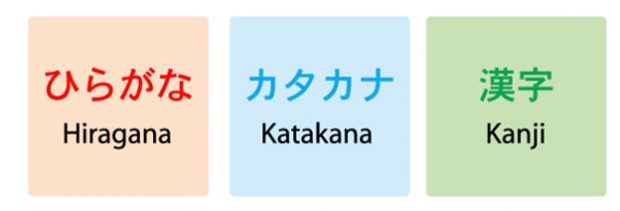

В японском языке существует три системы письменности. Многие в начале изучения допускают большую ошибку, называя алфавиты иероглифами, хотя на самом деле это совсем разные вещи.

Исторически так сложилось, что в Японии используют две слоговые азбуки: хирагану и катакану. Они сосуществуют с иероглифами, которые по-японски называются кандзи.

Несколько тысяч лет назад у японцев был устный язык, но совсем не было письменности. Чтобы это исправить они позаимствовали систему письма у соседней страны — Китая.

Китайские иероглифы — это идеограммы, указывающие на значение слова. Фонетически каждый из них обозначает слог. Японцы же решили использовать их звучание без привязки к смыслу. Иными словами, японские слова начали записывать иероглифами, подходящими по фонетическому звучанию. Позднее буддийскими монахами были придуманы сами азбуки как способ упрощенного чтения и написания кандзи.

Японские азбуки (и письмо в целом) разделялись по гендерному принципу. Изучение китайских букв было доступно очень ограниченной части мужского населения. Хираганой пользовались преимущественно женщины, катаканой в основном — мужчины. Они между собой и отличаются тем, что у первой азбуки буквы с плавными очертаниями, а у второй они, наоборот, более угловатые.

Несмотря на то, что хирагана считалась женской азбукой, ее изучали далеко не все женщины, а только особы, приближенные к императорскому двору или из высшего общества. Катакана же — это азбука, которой пользовались мужчины в качестве скорописи, а позднее записывали ей служебные части слов.

Слоговые азбуки

Теперь мы рассмотрим, где и когда используются эти алфавиты. Называется японская слоговая азбука 4-мя буквами: кана. Она же, в свою очередь, разделяется на два вида. Структура каны отличается тем, что, если в русском азбука — это буквы, то в японском — слоги. Каждый отдельный слог называется мора.

В таблице ниже представлена хирагана. Ее сразу можно определить по мягкому написанию слогов, выделяющихся своими плавными изгибами. Используется она для записи слов японского происхождения, обозначения различных грамматических частиц, предлогов и изменяемых окончаний.

| а

あ |

и

い |

у

う |

э

え |

о

お |

| ка

か |

ки

き |

ку

く |

кэ

け |

ко

こ |

| са

さ |

си

し |

су

す |

сэ

せ |

со

そ |

| та

た |

ти

ち |

цу

つ |

тэ

て |

то

と |

| на

な |

ни

に |

ну

ぬ |

нэ

ね |

но

の |

| ха

は |

хи

ひ |

фу

ふ |

хэ

へ |

хо

ほ |

| ма

ま |

ми

み |

му

む |

мэ

め |

мо

も |

| я

や |

ю

ゆ |

ё

よ |

||

| ра

ら |

ри

り |

ру

る |

рэ

れ |

ро

ろ |

| ва

わ |

н

ん |

во/о

を |

Как мы видим, у второй азбуки написание букв более угловатое. В современном японском катакана применяется в заимствованных словах, или гайрайго. Также она используется для записи иностранных имен и географических названий мест, городов, рек и т.д.

Иногда этой же азбукой пишутся некоторые японские слова, но делается это только ради моды или для того, чтобы акцентировать внимание на чем-то. В европейских языках для этого служит курсив, подчеркивание и жирное выделение.

Так, например, если хотят выделить слово, в рекламе или просто в статье, то применяется катакана. Это делается от того, что, как правило, иероглифы выделять очень сложно или практически невозможно.

| а

ア |

и

イ |

у

ウ |

э

エ |

о

オ |

| ка

カ |

ки

キ |

ку

ク |

кэ

ケ |

ко

コ |

| са

サ |

си

シ |

су

ス |

сэ

セ |

со

ソ |

| та

タ |

ти

チ |

цу

ツ |

тэ

テ |

то

ト |

| на

ナ |

ни

ニ |

ну

ヌ |

нэ

ネ |

но

ノ |

| ха

ハ |

хи

ヒ |

фу

フ |

хэ

ヘ |

хо

ホ |

| ма

マ |

ми

ミ |

му

ム |

мэ

メ |

мо

モ |

| я

ヤ |

ю

ユ |

ё

ヨ |

||

| ра

ラ |

ри

リ |

ру

ル |

рэ

レ |

ро

ロ |

| ва

ワ |

н

ン |

о

ヲ |

В таблицах представлены 46 основных слогов японских азбук. Также есть еще и дополнительные моры, образующиеся при помощи разных приемов, которые мы подробно разобрали в статье, посвященной различиям хираганы и катаканы.

Наша школа хочет вам помочь скорее научиться читать и писать по-японски! У нас есть для вас два замечательных недельных курса по хирагане и катакане.

Японские иероглифы кандзи

Сейчас кандзи используются при записи основ слов. Поэтому так важно знать все три вида письменности, чтобы пользоваться языком в полной мере.

Не стоит забывать, что кандзи просто пишутся по-другому, а звуки такие же, как в двух других азбуках.

Японские иероглифы для начинающих кажутся непосильной задачей. Во-первых, из-за их количества, ведь их больше 2 тысяч. Во-вторых, из-за сложности прочтения. Поэтому в отличие от хираганы и катаканы выучить кандзи японские будет сложнее.

Каждый иероглиф имеет одно или несколько прочтений: онъёми, или японская интерпретация китайского произношения иероглифа, и кунъёми, основанное на произношении исконно японских слов. То, как будет читаться кандзи, зависит от контекста в котором он находится: от сочетания с другими кандзи или его места в предложении.

Однако есть много вещей, которые помогут в изучении. Например, порядок штрихов. Возможно, вы уже знаете, что кандзи пишутся в определенной последовательности, которую очень важно запомнить. Не только для того, чтобы было легче различать написанные от руки знаки, но и потому что это поможет при их заучивании.

Иероглифы лучше учить последовательно. В Японии для этого существует целая система, которая называется кёику. В нее входят кандзи, которые преподают детям в начальной школе. Для каждого года обучения есть отдельный список. Например, таблица кандзи снизу соответствует первому классу. Это основные японские иероглифы для начинающих с переводом, которые необходимо знать для дальнейшего изучения языка.

| Кандзи | Значение | Онъёми | Кунъёми |

| 一 | один | いち

ити |

ひと

хито |

| 二 | два | に

ни |

ふた

фута |

| 三 | три | さん

сан |

み

ми |

| 四 | четыре | し

си |

よ

ё |

| 五 | пять | ご

го |

いつ

ицу |

| 六 | шесть | ろく

року |

む

му |

| 七 | семь | しち

сити |

なな

нана |

| 八 | восемь | はち

хати |

や

я |

| 九 | девять | きゅう

кю: |

ここの

коконо |

| 十 | десять | じゅう

дзю: |

とお

то: |

| 百 | сто | ひゃく

хяку |

もも

момо |

| 千 | тысяча | せん

сэн |

ち

ти |

| 上 | наверху | じょう

дзё: |

うえ

уэ |

| 下 | низ | か

ка |

した

сита |

| 左 | левый | さ

са |

ひだり

хидари |

| 右 | правый | う

у |

みぎ

миги |

| 中 | середина | ちゅう

тю: |

なか

нака |

| 大 | большой | だい

дай |

おお

о: |

| 小 | маленький, наименьший по размеру | しょう

сё: |

ちいさい

ти:сай |

| 月 | луна | げつ

гэцу |

つき

цуки |

| 日 | солнце | にち

нити |

か

ка |

| 年 | год | ねん

нэн |

とし

тоси |

| 早 | ранний | そう

со: |

はやい

хаяй |

| 木 | дерево | もく

моку |

き

ки |

| 林 | лес | りん

рин |

はやし

хаяси |

| 山 | гора | さん

сан |

やま

яма |

| 川 | река | せん

сэн |

かわ

кава |

| 土 | земля | ど

до |

つち

цути |

| 空 | пустота | くう

ку: |

から

кара |

| 田 | рисовое поле | でん

дэн |

た

та |

| 天 | небеса | てん

тэн |

あめ

амэ |

| 生 | необработанный | しょう

сё: |

なま

нама |

| 花 | цветок | か

ка |

はな

хана |

| 草 | трава | そう

со: |

くさ

куса |

| 虫 | насекомое | ちゅう

тю: |

むし

муси |

| 犬 | собака | けん

кэн |

いぬ

ину |

| 人 | человек | じん

дзин |

ひと

хито |

| 名 | имя | みょう

мё: |

な

на |

| 女 | женщина | にょ

нё |

おんな

онна |

| 男 | мужчина | だん

дан |

おとこ

отоко |

| 子 | ребёнок | し

си |

こ

ко |

| 目 | глаз | もく

моку |

め

мэ |

| 耳 | ухо | じ

дзи |

みみ

мими |

| 口 | рот | こう

ко: |

くち

кути |

| 手 | рука | しゅ

сю |

て

тэ |

| 足 | стопа | そく

соку |

あし

аси |

| 見 | видеть | けん

кэн |

みる

миру |

| 音 | звук | おん

он |

おと

ото |

| 力 | сила | りき

рики |

ちから

тикара |

| 気 | душа | き

ки |

いき

ики |

| 円 | круг | えん

эн |

まる

мару |

| 入 | входить | にゅう

ню: |

いる

иру |

| 出 | выходить | しゅつ

сюцу |

でる

дэру |

| 立 | вставать | りつ

рицу |

たつ

тацу |

| 休 | отдых | きゅう

кю: |

やすむ

ясуму |

| 先 | конец | せん

сэн |

さき

саки |

| 夕 | вечер | せき

сэки |

ゆう

ю: |

| 本 | книга | ほん

хон |

もと

мото |

| 文 | текст | もん

мон |

ふみ

фуми |

| 字 | символ | じ

дзи |

あざ

адза |

| 学 | учёба | がく

гаку |

まなぶ

манабу |

| 校 | школа | こう

ко: |

かせ

касэ |

| 村 | деревня | そん

сон |

むら

мура |

| 町 | город | ちょう

тё: |

まち

мати |

| 森 | лес | しん

син |

もり

мори |

| 正 | верный | せい

сэй |

ただしい

тадаси: |

| 水 | вода | すい

суй |

みず

мидзу |

| 火 | огонь | か

ка |

ひ

хи |

| 玉 | драгоценный камень | ぎょく

гёку |

たま

тама |

| 王 | правитель | おう

о: |

おおきみ

о:кими |

| 石 | камень | しゃく

сяку |

いし

иси |

| 竹 | бамбук | ちく

тику |

たけ

такэ |

| 糸 | нить | し

си |

いと

ито |

| 貝 | моллюск | ばい

бай |

かい

кай |

| 車 | любое транспортное средство на колёсах | しゃ

ся |

くるま

курума |

| 金 | золото | きん

кин |

かね

канэ |

| 雨 | дождь | う

у |

あめ

амэ |

| 赤 | красный цвет | しゃく

сяку |

あか

ака |

| 青 | голубой цвет | せい

сэй |

あお

ао |

| 白 | белый цвет | びゃく

бяку |

しろ

сиро |

Как выучить японские иероглифы?

Именно иероглифы пугают новичков в японском. Но выучить их определенно возможно. Это даже не так сложно, как кажется! Однако для этого потребуется какое-то время. Не стоит торопиться и пытаться запомнить сотни кандзи за один день.

Изучать один за другим японский кандзи для начинающих — плохая идея. В отличие от двух других систем письменности, эти символы лучше учить сразу в контексте. То есть надо сосредоточить внимание не просто на одном иероглифе, а на целых словах, где он используется.

Разберем это на примере одних из самых простых иероглифов японских. Возьмем два кандзи из таблицы выше:

- 日 — день/солнце. Онъёми: «ничи», кунъёми: «хи», «ка».

- 本 — основа/книга. Онъёми: «хон», кунъёми: «мото».

Вместо того, чтобы заучивать каждое звучание по отдельности легче выучить слово, где используются эти кандзи: 日本 (нихон) — Япония.

Пытаться запоминать одиночные прочтения может оказаться неэффективным по нескольким причинам:

- Вы не будете знать, в каких случаях какой вариант используется. Например, выучив онъёми и кунъёми 本, вы все еще не будете знать, как читается слово 大本 (о:мото) — корень.

- Вы их быстро забудете.

Еще один хороший способ, как запомнить японские иероглифы — это мнемоника. С помощью ассоциаций можно выучить не только сами кандзи, но и полные слова. Например, та же “Япония” в Западной культуре известна как “Страна Восходящего Солнца”. Это выражение и является мнемоникой для запоминания 日本: 日 (солнце) + 本 (основа) = “основа солнца” или “там, где начинается солнце”.

Это наиболее эффективные варианты, чтобы учить японские иероглифы кандзи. В учебниках по изучению кандзи всегда даются примеры слов для каждого символа. Также в них часто можно найти картинки, которые помогают выстроить ассоциацию между иероглифом и его значением.

Если не повторять иероглифы, то они быстро забудутся. Поэтому каждый день выделяйте хотя бы 30 минут для их повторения.

Хирагана, катакана, кандзи — японский язык в целом — вещи непростые, но интересные. Каждый элемент — это отдельный необычный мир, исследовать который можно разными способами.

Итак, сегодня мы выяснили, что японские буквы были скопированы с китайских иероглифов, а затем развились в два отдельных алфавита. Хирагана и катакана являются базовыми системами письменности, выучив которые можно будет приступать к изучению кандзи.

Теперь, если в сканвордах встретите вопросы наподобие нижеперечисленных, то точно будете знать на них ответы:

- угловатая японская азбука (8 букв);

- основная японская азбука (8 букв);

- японская азбука (4 буквы) или раздел японской азбуки (4 буквы);

- японская буква (4 буквы);

- японский иероглиф (5 букв).

Вы же их знаете? Напишите в комментариях!

А что еще интересного знаете о японских слоговых азбуках и иероглифах вы? Также поделитесь своими знаниями в комментариях! До новых встреч!

Последняя и самая известная сторона японской письменности — кандзи.

Кандзи — китайские иероглифы, адаптированные для японского языка.

Большая часть японских слов пишется в кандзи, но звуки те же, что в хирагане и катакане.

Порядок штрихов

С самого начала изучения уделяйте внимание правильному порядку и направлению линий, чтобы избежать вредных привычек.

Часто изучающие не видят смысла в порядке штрихов, если результат тот же.

Но они упускают из виду то, что существуют тысячи символов и не всегда они пишутся так тщательно как выглядят на печати.

Правильный порядок штрихов помогает узнать иероглифы, даже если вы пишите быстро или от руки.

Простейшие символы, называемые радикалами, часто используются как компоненты сложных символов.

Как только вы выучите порядок штрихов радикалов и привыкните к принципу, вы обнаружите, что несложно угадать правильный порядок для большинства кандзи.

Чаще всего штрихи наносятся из левого верхнего угла в правый нижний.

Это означает, что горизонтальные черты обычно рисуют слева направо, а вертикальные — сверху вниз.

В любом случае когда вы сомневаетесь в порядке штрихов, сверьтесь со словарем кандзи.

Кандзи в лексиконе

В современном японском используется немногим более 2 тысяч иероглифов, и запоминание каждого по отдельности не работает так хорошо как с хираганой.

Эффективная стратегия овладения кандзи — изучение с новыми словами с большим контекстом.

Так для закрепления в памяти мы связываем символ с контекстной информацией.

Кандзи используются для представления реальных слов, поэтому сосредоточьтесь на словах и лексике, а не на самих символах.

Вы увидите, как работают кандзи, выучив несколько распространенных иероглифов и слов из данного параграфа.

Чтения кандзи

Первый кандзи, который мы изучим —「人」, иероглиф для понятия «человек».

Это простой символ из двух черт, каждая из которых наносится сверху вниз.

Возможно вы заметили, что символ из шрифта не всегда похож на рукописную версию ниже.

Это еще один важный повод сверяться с порядком штрихов.

|

Значение: человек; личность |

| Кунъёми: ひと | |

| Онъёми: ジン |

Кандзи в японском языке имеют одно или несколько чтений, которые делят на две категории: кунъёми (или кун, или кунное чтение) и онъёми (или он, или онное чтение). Кунъёми — японское чтение иероглифа, в то время как онъёми основано на оригинальном китайском произношении.

В основном кунъёми используется для слов из одного символа. В качестве примера — слово со значением «человек»:

人 【ひと】 — человек

Кунъёми также используется для исконно японских слов, включая большинство прилагательных и глаголов.

Онъёми в большинстве случаев используется для слов, пришедших из китайского языка, часто из двух или более кандзи. По этой причине онъёми часто записывается катаканой. Больше примеров последует по мере изучения кандзи. Один очень полезный пример онъёми — присоединение 「人」 к названиям стран для описания национальности.

Примеры:

- アメリカ人 【アメリカ・じん】 — американец

- フランス人 【ふらんす・じん】 — француз

Хотя у большинства иероглифов нет множества кунъёми или онъёми, у наиболее распространенных кандзи, вроде 「人」, много чтений. Здесь я буду приводить только чтения, применимые к изучаемым словам. Изучение чтений без контекста в виде слов создает ненужную путаницу, поэтому я не рекомендую учить все чтения сразу.

Теперь, после знакомства с общей идеей, давайте изучим чуть больше слов и сопутствующие им кандзи. Красные точки на диаграммах порядка черт демонстрируют, где начинается каждый штрих.

- 日本 【に・ほん】 — Япония

- 本 【ほん】 — книга

| 日 | Значение: солнце; день |

| Онъёми: ニ |

| 本 | Значение: основа, источник; книга |

| Онъёми: ホン |

- 学生 【がく・せい】 — учащийся

- 先生 【せん・せい】 — учитель

| 学 | Значение: учение; знания; наука |

| Онъёми: ガク |

| 先 | Значение: впереди; предшествование, превосходство |

| Онъёми: セン |

| 生 | Значение: жизнь |

| Онъёми: セイ |

- 高い 【たか・い】 — высокий; дорогой

- 学校 【がっ・こう】 — школа

- 高校 【こう・こう】 — старшая школа (третья ступень обучения, эквивалентна 10–12 классам у нас)

| 高 | Значение: высокий; дорогой |

| Кунъёми: たか・い | |

| Онъёми: コウ |

| 校 | Значение: школа |

| Онъёми: コウ |

- 小さい 【ちい・さい】 — маленький

- 大きい 【おお・きい】 — большой

- 小学校 【しょう・がっ・こう】 — начальная школа (первая ступень обучения, соответствует 1–6 классам у нас)

- 中学校 【ちゅう・がっ・こう】 — средняя школа (вторая ступень обучения, 7–9 класс у нас)

- 大学 【だい・がく】 — колледж; университет

- 小学生 【しょう・がく・せい】 — учащийся начальной школы

- 中学生 【ちゅう・がく・せい】 — учащийся средней школы

- 大学生 【だい・がく・せい】 — студент

| 小 | Значение: маленький |

| Кунъёми: ちい・さい | |

| Онъёми: ショウ |

| 中 | Значение: середина; внутри |

| Онъёми: チュウ |

| 大 | Значение: большой |

| Кунъёми: おお・きい | |

| Онъёми: ダイ |

- 国 【くに】 — страна

- 中国 【ちゅう・ごく】 — Китай

- 中国人 【ちゅう・ごく・じん】 — китаец

| 国 | Значение: страна |

| Кунъёми: くに | |

| Онъёми: コク |

- 日本語 【に・ほん・ご】 — японский язык

- 中国語 【ちゅう・ごく・ご】 — китайский язык

- 英語 【えい・ご】 — английский язык

- フランス語 【フランス・ご】 — французский язык

- スペイン語 【スペイン・ご】 — испанский язык

| 英 | Значение: Англия |

| Онъёми: エイ |

| 語 | Значение: язык |

| Онъёми: ゴ |

Только с 14 символами мы изучили более 25 слов — от Китая до школьника!

Кандзи обычно воспринимаются как основное препятствие в изучении, но их легко превратить в ценный инструмент, если изучать вместе со словами.

Окуригана и изменение чтений

Вы могли заметить, что некоторые слова оканчиваются хираганой, например 「高い」 или 「大きい」.

Так как это прилагательные, сопровождающая хирагана, называемая окуриганой, нужна для различных преобразований без влияния на кандзи.

Запоминайте, где именно заканчивается кандзи и начинается хирагана.

Не надо писать 「大きい」 как 「大い」.

Вы также могли заметить, что чтения кандзи по отдельности не соответствуют чтениям в некоторых словах.

Например, 「学校」 читается как 「がっこう」, а не 「がくこう」.

Чтения часто так трансформируются для облегчения произношения.

В идеале проверяйте чтение каждого нового для вас слова.

К счастью, с помощью онлайн- и электронных словарей поиск новых кандзи не представляет трудностей.

Руководство по поиску кандзи (англ.)

Разные кандзи для похожих слов

Кандзи часто используется для создания нюансов или придания иного оттенка значению слова.

Для некоторых слов важно использовать правильный кандзи в нужной ситуации.

Например, прилагательное「あつい」 — «горячий» — при описании климата пишут как 「暑い」, а если речь о горячем объекте или человеке —「熱い」.

| 暑 | Значение: горячий (только для описания климата) |

| Кунъёми: あつ・い |

| 熱 | Значение: жар; лихорадка |

| Кунъёми: あつ・い |

В других случаях, хотя и применяются кандзи, верные для всех значений выбранного слова, автор вправе выбирать иероглифы с узким значением, соответственно стилю.

В примерах данной книги обычно используются общие и простые кандзи.

Подробности об использовании разных кандзи для одного и того же слова вас ждут в руководстве по изучению слов (англ.).

This article is about the modern writing system and its history. For an overview of the entire language, see Japanese language. For the use of Latin letters to write Japanese, see Romanization of Japanese.

| Japanese | |

|---|---|

Japanese novel using kanji kana majiri bun (text with both kanji and kana), the most general orthography for modern Japanese. Ruby characters (or furigana) are also used for kanji words (in modern publications these would generally be omitted for well-known kanji). The text is in the traditional tategaki («vertical writing») style; it is read down the columns and from right to left, like traditional Chinese. Published in 1908. |

|

| Script type |

mixed logographic (kanji), syllabic (hiragana and katakana) |

|

Time period |

4th century AD to present |

| Direction | When written vertically, Japanese text is written from top to bottom, with multiple columns of text progressing from right to left. When written horizontally, text is almost always written left to right, with multiple rows progressing downward, as in standard English text. In the early to mid-1900s, there were infrequent cases of horizontal text being written right to left, but that style is very rarely seen in modern Japanese writing.[citation needed] |

| Languages | Japanese language Ryukyuan languages |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(See kanji and kana)

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Jpan (413), Japanese (alias for Han + Hiragana + Katakana) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode range |

U+4E00–U+9FBF Kanji U+3040–U+309F Hiragana U+30A0–U+30FF Katakana |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.[1][2]

Several thousand kanji characters are in regular use, which mostly originate from traditional Chinese characters. Others made in Japan are referred to as “Japanese kanji” (和製漢字, wasei kanji; also known as “country’s kanji” 国字, kokuji). Each character has an intrinsic meaning (or range of meanings), and most have more than one pronunciation, the choice of which depends on context. Japanese primary and secondary school students are required to learn 2,136 jōyō kanji as of 2010.[3] The total number of kanji is well over 50,000, though few if any native speakers know anywhere near this number.[4]

In modern Japanese, the hiragana and katakana syllabaries each contain 46 basic characters, or 71 including diacritics. With one or two minor exceptions, each different sound in the Japanese language (that is, each different syllable, strictly each mora) corresponds to one character in each syllabary. Unlike kanji, these characters intrinsically represent sounds only; they convey meaning only as part of words. Hiragana and katakana characters also originally derive from Chinese characters, but they have been simplified and modified to such an extent that their origins are no longer visually obvious.

Texts without kanji are rare; most are either children’s books — since children tend to know few kanji at an early age — or early electronics such as computers, phones, and video games, which could not display complex graphemes like kanji due to both graphical and computational limitations.[5]

To a lesser extent, modern written Japanese also uses initialisms from the Latin alphabet, for example in terms such as «BC/AD», «a.m./p.m.», «FBI», and «CD». Romanized Japanese is most frequently used by foreign students of Japanese who have not yet mastered kana, and by native speakers for computer input.

Use of scripts[edit]

Kanji[edit]

Kanji (漢字) are logographic characters (based on traditional ones) taken from Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese.

It is known from archaeological evidence that the first contacts that the Japanese had with Chinese writing took place in the 1st century AD, during the late Yayoi period. However, the Japanese people of that era probably had little to no comprehension of the script, and they would remain relatively illiterate until the 5th century AD in the Kofun period, when writing in Japan became more widespread.

They are used to write most content words of native Japanese or (historically) Chinese origin, which include the following:

- most nouns, such as 川 (kawa, «river») and 学校 (gakkō, «school»)

- the stems of most verbs and adjectives, such as 見 in 見る (miru, «see») and 白 in 白い (shiroi, «white»)

- the stems of many adverbs, such as 速 in 速く (hayaku, «quickly») and 上手 as in 上手に (jōzu ni, «masterfully»)

- most Japanese personal names and place names, such as 田中 (Tanaka) and 東京 (Tōkyō). (Certain names may be written in hiragana or katakana, or some combination of these, plus kanji.)

Some Japanese words are written with different kanji depending on the specific usage of the word—for instance, the word naosu (to fix, or to cure) is written 治す when it refers to curing a person, and 直す when it refers to fixing an object.

Most kanji have more than one possible pronunciation (or «reading»), and some common kanji have many. These are broadly divided into on’yomi, which are readings that approximate to a Chinese pronunciation of the character at the time it was adopted into Japanese, and kun’yomi, which are pronunciations of native Japanese words that correspond to the meaning of the kanji character. However, some kanji terms have pronunciations that correspond to neither the on’yomi nor the kun’yomi readings of the individual kanji within the term, such as 明日 (ashita, «tomorrow») and 大人 (otona, «adult»).

Unusual or nonstandard kanji readings may be glossed using furigana. Kanji compounds are sometimes given arbitrary readings for stylistic purposes. For example, in Natsume Sōseki’s short story The Fifth Night, the author uses 接続って for tsunagatte, the gerundive -te form of the verb tsunagaru («to connect»), which would usually be written as 繋がって or つながって. The word 接続, meaning «connection», is normally pronounced setsuzoku.

Kana[edit]

Hiragana[edit]

Hiragana (平仮名) emerged as a manual simplification via cursive script of the most phonetically widespread kanji among those who could read and write during the Heian period (794-1185). The main creators of the current hiragana were ladies of the Japanese imperial court, that used the script in the writing of personal communications and literature.

Hiragana is used to write the following:

- okurigana (送り仮名)—inflectional endings for adjectives and verbs—such as る in 見る (miru, «see») and い in 白い (shiroi, «white»), and respectively た and かった in their past tense inflections 見た (mita, «saw») and 白かった (shirokatta, «was white»).

- various function words, including most grammatical particles, or postpositions (joshi (助詞))—small, usually common words that, for example, mark sentence topics, subjects and objects or have a purpose similar to English prepositions such as «in», «to», «from», «by» and «for».

- miscellaneous other words of various grammatical types that lack a kanji rendition, or whose kanji is obscure, difficult to typeset, or considered too difficult to understand for the context (such as in children’s books).

- Furigana (振り仮名)—phonetic renderings of kanji placed above or beside the kanji character. Furigana may aid children or non-native speakers or clarify nonstandard, rare, or ambiguous readings, especially for words that use kanji not part of the jōyō kanji list.

There is also some flexibility for words with common kanji renditions to be instead written in hiragana, depending on the individual author’s preference (all Japanese words can be spelled out entirely in hiragana or katakana, even when they are normally written using kanji). Some words are colloquially written in hiragana and writing them in kanji might give them a more formal tone, while hiragana may impart a softer or more emotional feeling.[6] For example, the Japanese word kawaii, the Japanese equivalent of «cute», can be written entirely in hiragana as in かわいい, or with kanji as 可愛い.

Some lexical items that are normally written using kanji have become grammaticalized in certain contexts, where they are instead written in hiragana. For example, the root of the verb 見る (miru, «see») is normally written with the kanji 見 for the mi portion. However, when used as a supplementary verb as in 試してみる (tameshite miru) meaning «to try out», the whole verb is typically written in hiragana as みる, as we see also in 食べてみる (tabete miru, «try to eat [it] and see»).

Katakana[edit]

Katakana (片仮名) emerged around the 9th century, in the Heian period, when Buddhist monks created a syllabary derived from Chinese characters to simplify their reading, using portions of the characters as a kind of shorthand. The origin of the alphabet is attributed to the monk Kūkai.

Katakana is used to write the following:

- transliteration of foreign words and names, such as コンピュータ (konpyūta, «computer») and ロンドン (Rondon, «London»). However, some foreign borrowings that were naturalized may be rendered in hiragana, such as たばこ (tabako, «tobacco»), which comes from Portuguese. See also Transcription into Japanese.

- commonly used names of animals and plants, such as トカゲ (tokage, «lizard»), ネコ (neko, «cat») and バラ (bara, «rose»), and certain other technical and scientific terms, such as mineral names

- occasionally, the names of miscellaneous other objects whose kanji are rare, such as ローソク (rōsoku, «candle»)

- onomatopoeia, such as ワンワン (wan-wan, «woof-woof»), and other sound symbolism

- emphasis, much like italicisation in European languages.

Katakana can also be used to impart the idea that words are spoken in a foreign or otherwise unusual accent; for example, the speech of a robot.

Rōmaji[edit]

The first contact of the Japanese with the Latin alphabet occurred in the 16th century, during the Muromachi period, when they had contact with Portuguese navigators, the first European people to visit the Japanese islands. The earliest Japanese romanization system was based on Portuguese orthography. It was developed around 1548 by a Japanese Catholic named Anjirō.

The Latin alphabet is used to write the following:

- Latin-alphabet acronyms and initialisms, such as NATO or UFO

- Japanese personal names, corporate brands, and other words intended for international use (for example, on business cards, in passports, etc.)

- foreign names, words, and phrases, often in scholarly contexts

- foreign words deliberately rendered to impart a foreign flavour, for instance, in commercial contexts

- other Japanized words derived or originated from foreign languages, such as Jリーグ (jei rīgu, «J. League»), Tシャツ (tī shatsu, «T-shirt») or B級グルメ (bī-kyū gurume, «B-rank gourmet [cheap and local cuisines]»)

Arabic numerals[edit]

Arabic numerals (as opposed to traditional kanji numerals) are often used to write numbers in horizontal text, especially when numbering things rather than indicating a quantity, such as telephone numbers, serial numbers and addresses. Arabic numerals were introduced in Japan probably at the same time as the Latin alphabet, in the 16th century during the Muromachi period, the first contact being via Portuguese navigators. These numerals did not originate in Europe, as the Portuguese inherited them during the Arab occupation of the Iberian peninsula. See also Japanese numerals.

Hentaigana[edit]

Hentaigana (変体仮名), a set of archaic kana made obsolete by the Meiji reformation, are sometimes used to impart an archaic flavor, like in items of food (esp. soba).

Additional mechanisms[edit]

Jukujikun refers to instances in which words are written using kanji that reflect the meaning of the word though the pronunciation of the word is entirely unrelated to the usual pronunciations of the constituent kanji. Conversely, ateji refers to the employment of kanji that appear solely to represent the sound of the compound word but are, conceptually, utterly unrelated to the signification of the word.

Examples[edit]

Sentences are commonly written using a combination of all three Japanese scripts: kanji (in red), hiragana (in purple), and katakana (in orange), and in limited instances also include

Latin alphabet characters (in green) and Arabic numerals (in black):

Tシャツを3枚購入しました。

The same text can be transliterated to the Latin alphabet (rōmaji), although this will generally only be done for the convenience of foreign language speakers:

Tīshatsu o san—mai kōnyū shimashita.

Translated into English, this reads:

I bought 3 T-shirts.

All words in modern Japanese can be written using hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji, while only some have Kanji. Words that have no dedicated kanji may still be written with kanji by employing either ateji (like in man’yogana, から = 可良) or jukujikun, like in the title of とある科学の超電磁砲 (超電磁砲 being used to represent レールガン).

| Kanji | Hiragana | Katakana | Rōmaji | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 私 | わたし | ワタシ | watashi | I, me |

| 金魚 | きんぎょ | キンギョ | kingyo | goldfish |

| 煙草 or 莨 | たばこ | タバコ | tabako | tobacco, cigarette |

| 東京 | とうきょう | トーキョー | tōkyō | Tokyo, literally meaning «eastern capital» |

| none | です | デス | desu | is, am, to be (hiragana, of Japanese origin); death (katakana, of English origin) |

Although rare, there are some words that use all three scripts in the same word. An example of this is the term くノ一 (rōmaji: kunoichi), which uses a hiragana, a katakana, and a kanji character, in that order. It is said that if all three characters are put in the same kanji «square», they all combine to create the kanji 女 (woman/female). Another example is 消しゴム (rōmaji: keshigomu) which means «eraser», and uses a kanji, a hiragana, and two katakana characters, in that order.

Statistics[edit]

A statistical analysis of a corpus of the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun from the year 1993 (around 56.6 million tokens) revealed:[7]

|

|

Collation[edit]

Collation (word ordering) in Japanese is based on the kana, which express the pronunciation of the words, rather than the kanji. The kana may be ordered using two common orderings, the prevalent gojūon (fifty-sound) ordering, or the old-fashioned iroha ordering. Kanji dictionaries are usually collated using the radical system, though other systems, such as SKIP, also exist.

Direction of writing[edit]

Traditionally, Japanese is written in a format called tategaki (縦書き), which was inherited from traditional Chinese practice. In this format, the characters are written in columns going from top to bottom, with columns ordered from right to left. After reaching the bottom of each column, the reader continues at the top of the column to the left of the current one.

Modern Japanese also uses another writing format, called yokogaki (横書き). This writing format is horizontal and reads from left to right, as in English.

A book printed in tategaki opens with the spine of the book to the right, while a book printed in yokogaki opens with the spine to the left.

Spacing and punctuation[edit]

Japanese is normally written without spaces between words, and text is allowed to wrap from one line to the next without regard for word boundaries. This convention was originally modelled on Chinese writing, where spacing is superfluous because each character is essentially a word in itself (albeit compounds are common). However, in kana and mixed kana/kanji text, readers of Japanese must work out where word divisions lie based on an understanding of what makes sense. For example, あなたはお母さんにそっくりね。 must be mentally divided as あなた は お母さん に そっくり ね。 (Anata wa okaasan ni sokkuri ne, «You’re just like your mother»). In rōmaji, it may sometimes be ambiguous whether an item should be transliterated as two words or one. For example, 愛する, «to love», composed of 愛 (ai, «love») and する (suru, «to do», here a verb-forming suffix), is variously transliterated as aisuru or ai suru.

Words in potentially unfamiliar foreign compounds, normally transliterated in katakana, may be separated by a punctuation mark called a nakaguro (中黒, «middle dot») to aid Japanese readers. For example, ビル・ゲイツ (Bill Gates). This punctuation is also occasionally used to separate native Japanese words, especially in concatenations of kanji characters where there might otherwise be confusion or ambiguity about interpretation, and especially for the full names of people.

The Japanese full stop (。) and comma (、) are used for similar purposes to their English equivalents, though comma usage can be more fluid than is the case in English. The question mark (?) is not used in traditional or formal Japanese, but it may be used in informal writing, or in transcriptions of dialogue where it might not otherwise be clear that a statement was intoned as a question. The exclamation mark (!) is restricted to informal writing. Colons and semicolons are available but are not common in ordinary text. Quotation marks are written as 「 … 」, and nested quotation marks as 『 … 』. Several bracket styles and dashes are available.

History of the Japanese script[edit]

Importation of kanji[edit]

Japan’s first encounters with Chinese characters may have come as early as the 1st century AD with the King of Na gold seal, said to have been given by Emperor Guangwu of Han in AD 57 to a Japanese emissary.[8] However, it is unlikely that the Japanese became literate in Chinese writing any earlier than the 4th century AD.[8]

Initially Chinese characters were not used for writing Japanese, as literacy meant fluency in Classical Chinese, not the vernacular. Eventually a system called kanbun (漢文) developed, which, along with kanji and something very similar to Chinese grammar, employed diacritics to hint at the Japanese translation. The earliest written history of Japan, the Kojiki (古事記), compiled sometime before 712, was written in kanbun. Even today Japanese high schools and some junior high schools teach kanbun as part of the curriculum.

The development of man’yōgana[edit]

No full-fledged script for written Japanese existed until the development of man’yōgana (万葉仮名), which appropriated kanji for their phonetic value (derived from their Chinese readings) rather than their semantic value. Man’yōgana was initially used to record poetry, as in the Man’yōshū (万葉集), compiled sometime before 759, whence the writing system derives its name. Some scholars claim that man’yōgana originated from Baekje, but this hypothesis is denied by mainstream Japanese scholars.[9][10] The modern kana, namely hiragana and katakana, are simplifications and systemizations of man’yōgana.

Due to the large number of words and concepts entering Japan from China which had no native equivalent, many words entered Japanese directly, with a similar pronunciation to the original Chinese. This Chinese-derived reading is known as on’yomi (音読み), and this vocabulary as a whole is referred to as Sino-Japanese in English and kango (漢語) in Japanese. At the same time, native Japanese already had words corresponding to many borrowed kanji. Authors increasingly used kanji to represent these words. This Japanese-derived reading is known as kun’yomi (訓読み). A kanji may have none, one, or several on’yomi and kun’yomi. Okurigana are written after the initial kanji for verbs and adjectives to give inflection and to help disambiguate a particular kanji’s reading. The same character may be read several different ways depending on the word. For example, the character 行 is read i as the first syllable of iku (行く, «to go»), okona as the first three syllables of okonau (行う, «to carry out»), gyō in the compound word gyōretsu (行列, «line» or «procession»), kō in the word ginkō (銀行, «bank»), and an in the word andon (行灯, «lantern»).

Some linguists have compared the Japanese borrowing of Chinese-derived vocabulary as akin to the influx of Romance vocabulary into English during the Norman conquest of England. Like English, Japanese has many synonyms of differing origin, with words from both Chinese and native Japanese. Sino-Japanese is often considered more formal or literary, just as latinate words in English often mark a higher register.

Script reforms[edit]

Meiji period[edit]

The significant reforms of the 19th century Meiji era did not initially impact the Japanese writing system. However, the language itself was changing due to the increase in literacy resulting from education reforms, the massive influx of words (both borrowed from other languages or newly coined), and the ultimate success of movements such as the influential genbun itchi (言文一致) which resulted in Japanese being written in the colloquial form of the language instead of the wide range of historical and classical styles used previously. The difficulty of written Japanese was a topic of debate, with several proposals in the late 19th century that the number of kanji in use be limited. In addition, exposure to non-Japanese texts led to unsuccessful proposals that Japanese be written entirely in kana or rōmaji. This period saw Western-style punctuation marks introduced into Japanese writing.[11]

In 1900, the Education Ministry introduced three reforms aimed at improving the process of education in Japanese writing:

- standardization of hiragana, eliminating the range of hentaigana then in use;

- restriction of the number of kanji taught in elementary schools to about 1,200;

- reform of the irregular kana representation of the Sino-Japanese readings of kanji to make them conform with the pronunciation.

The first two of these were generally accepted, but the third was hotly contested, particularly by conservatives, to the extent that it was withdrawn in 1908.[12]

Pre–World War II[edit]

The partial failure of the 1900 reforms combined with the rise of nationalism in Japan effectively prevented further significant reform of the writing system. The period before World War II saw numerous proposals to restrict the number of kanji in use, and several newspapers voluntarily restricted their kanji usage and increased usage of furigana; however, there was no official endorsement of these, and indeed much opposition. However, one successful reform was the standardization of hiragana, which involved reducing the possibilities of writing down Japanese morae down to only one hiragana character per morae, which led to labeling all the other previously used hiragana as hentaigana and discarding them in daily use.[13]

Post–World War II[edit]

The period immediately following World War II saw a rapid and significant reform of the writing system. This was in part due to influence of the Occupation authorities, but to a significant extent was due to the removal of traditionalists from control of the educational system, which meant that previously stalled revisions could proceed. The major reforms were:

- gendai kanazukai (現代仮名遣い)—alignment of kana usage with modern pronunciation, replacing the old historical kana usage (1946);

- promulgation of various restricted sets of kanji:

- tōyō kanji (当用漢字) (1946), a collection of 1850 characters for use in schools, textbooks, etc.;

- kanji to be used in schools (1949);

- an additional collection of jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字), which, supplementing the tōyō kanji, could be used in personal names (1951);

- simplifications of various complex kanji letter-forms shinjitai (新字体).

At one stage, an advisor in the Occupation administration proposed a wholesale conversion to rōmaji, but it was not endorsed by other specialists and did not proceed.[14]

In addition, the practice of writing horizontally in a right-to-left direction was generally replaced by left-to-right writing. The right-to-left order was considered a special case of vertical writing, with columns one character high[clarification needed], rather than horizontal writing per se; it was used for single lines of text on signs, etc. (e.g., the station sign at Tokyo reads 駅京東).

The post-war reforms have mostly survived, although some of the restrictions have been relaxed. The replacement of the tōyō kanji in 1981 with the 1,945 jōyō kanji (常用漢字)—a modification of the tōyō kanji—was accompanied by a change from «restriction» to «recommendation», and in general the educational authorities have become less active in further script reform.[15]

In 2004, the jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字), maintained by the Ministry of Justice for use in personal names, was significantly enlarged. The jōyō kanji list was extended to 2,136 characters in 2010.

Romanization[edit]

There are a number of methods of rendering Japanese in Roman letters. The Hepburn method of romanization, designed for English speakers, is a de facto standard widely used inside and outside Japan. The Kunrei-shiki system has a better correspondence with Japanese phonology, which makes it easier for native speakers to learn. It is officially endorsed by the Ministry of Education and often used by non-native speakers who are learning Japanese as a second language.[citation needed] Other systems of romanization include Nihon-shiki, JSL, and Wāpuro rōmaji.

Lettering styles[edit]

- Shodō

- Edomoji

- Minchō

- East Asian sans-serif typeface

Variant writing systems[edit]

- Gyaru-moji

- Hentaigana

- Man’yōgana

See also[edit]

- Genkō yōshi (graph paper for writing Japanese)

- Iteration mark (Japanese duplication marks)

- Japanese typographic symbols (non-kana, non-kanji symbols)

- Japanese Braille

- Japanese language and computers

- Japanese manual syllabary

- Chinese writing system

- Okinawan writing system

- Kaidā glyphs (Yonaguni)

- Ainu language § Writing

- Siddhaṃ script (Indic alphabet used for Buddhist scriptures)

References[edit]

- ^ Serge P. Shohov (2004). Advances in Psychology Research. Nova Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-59033-958-9.

- ^ Kazuko Nakajima (2002). Learning Japanese in the Network Society. University of Calgary Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-55238-070-3.

- ^ «Japanese Kanji List». www.saiga-jp.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ «How many Kanji characters are there?». japanese.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ «How To Play (and comprehend!) Japanese Games». GBAtemp.net -> The Independent Video Game Community. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ^ Joseph F. Kess; Tadao Miyamoto (1 January 1999). The Japanese Mental Lexicon: Psycholinguistics Studies of Kana and Kanji Processing. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 90-272-2189-8.

- ^ Chikamatsu, Nobuko; Yokoyama, Shoichi; Nozaki, Hironari; Long, Eric; Fukuda, Sachio (2000). «A Japanese logographic character frequency list for cognitive science research». Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 32 (3): 482–500. doi:10.3758/BF03200819. PMID 11029823. S2CID 21633023.

- ^ a b Miyake (2003:8).

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2002). 韓国人の日本偽史―日本人はビックリ! (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-402716-7.

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2007). 韓vs日「偽史ワールド」 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-387703-9.

- ^ Twine, 1991

- ^ Seeley, 1990

- ^ Hashi (25 January 2012). «Hentaigana: How Japanese Went from Illegible to Legible in 100 Years». Tofugu. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ^ Unger, 1996

- ^ Gottlieb, 1996

Sources[edit]

- Gottlieb, Nanette (1996). Kanji Politics: Language Policy and Japanese Script. Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7103-0512-5.

- Habein, Yaeko Sato (1984). The History of the Japanese Written Language. University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 0-86008-347-0.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo (2003). Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-30575-6.

- Seeley, Christopher (1984). «The Japanese Script since 1900». Visible Language. XVIII. 3: 267–302.

- Seeley, Christopher (1991). A History of Writing in Japan. University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2217-X.

- Twine, Nanette (1991). Language and the Modern State: The Reform of Written Japanese. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00990-1.

- Unger, J. Marshall (1996). Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan: Reading Between the Lines. OUP. ISBN 0-19-510166-9.

External links[edit]

- The Modern Japanese Writing System: an excerpt from Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan, by J. Marshall Unger.

- The 20th Century Japanese Writing System: Reform and Change by Christopher Seeley

- Japanese Hiragana Conversion API by NTT Resonant

- Japanese Morphological Analysis API by NTT Resonant

This article is about the modern writing system and its history. For an overview of the entire language, see Japanese language. For the use of Latin letters to write Japanese, see Romanization of Japanese.

| Japanese | |

|---|---|

Japanese novel using kanji kana majiri bun (text with both kanji and kana), the most general orthography for modern Japanese. Ruby characters (or furigana) are also used for kanji words (in modern publications these would generally be omitted for well-known kanji). The text is in the traditional tategaki («vertical writing») style; it is read down the columns and from right to left, like traditional Chinese. Published in 1908. |

|

| Script type |

mixed logographic (kanji), syllabic (hiragana and katakana) |

|

Time period |

4th century AD to present |

| Direction | When written vertically, Japanese text is written from top to bottom, with multiple columns of text progressing from right to left. When written horizontally, text is almost always written left to right, with multiple rows progressing downward, as in standard English text. In the early to mid-1900s, there were infrequent cases of horizontal text being written right to left, but that style is very rarely seen in modern Japanese writing.[citation needed] |

| Languages | Japanese language Ryukyuan languages |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(See kanji and kana)

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Jpan (413), Japanese (alias for Han + Hiragana + Katakana) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode range |

U+4E00–U+9FBF Kanji U+3040–U+309F Hiragana U+30A0–U+30FF Katakana |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.[1][2]

Several thousand kanji characters are in regular use, which mostly originate from traditional Chinese characters. Others made in Japan are referred to as “Japanese kanji” (和製漢字, wasei kanji; also known as “country’s kanji” 国字, kokuji). Each character has an intrinsic meaning (or range of meanings), and most have more than one pronunciation, the choice of which depends on context. Japanese primary and secondary school students are required to learn 2,136 jōyō kanji as of 2010.[3] The total number of kanji is well over 50,000, though few if any native speakers know anywhere near this number.[4]

In modern Japanese, the hiragana and katakana syllabaries each contain 46 basic characters, or 71 including diacritics. With one or two minor exceptions, each different sound in the Japanese language (that is, each different syllable, strictly each mora) corresponds to one character in each syllabary. Unlike kanji, these characters intrinsically represent sounds only; they convey meaning only as part of words. Hiragana and katakana characters also originally derive from Chinese characters, but they have been simplified and modified to such an extent that their origins are no longer visually obvious.

Texts without kanji are rare; most are either children’s books — since children tend to know few kanji at an early age — or early electronics such as computers, phones, and video games, which could not display complex graphemes like kanji due to both graphical and computational limitations.[5]

To a lesser extent, modern written Japanese also uses initialisms from the Latin alphabet, for example in terms such as «BC/AD», «a.m./p.m.», «FBI», and «CD». Romanized Japanese is most frequently used by foreign students of Japanese who have not yet mastered kana, and by native speakers for computer input.

Use of scripts[edit]

Kanji[edit]

Kanji (漢字) are logographic characters (based on traditional ones) taken from Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese.

It is known from archaeological evidence that the first contacts that the Japanese had with Chinese writing took place in the 1st century AD, during the late Yayoi period. However, the Japanese people of that era probably had little to no comprehension of the script, and they would remain relatively illiterate until the 5th century AD in the Kofun period, when writing in Japan became more widespread.

They are used to write most content words of native Japanese or (historically) Chinese origin, which include the following:

- most nouns, such as 川 (kawa, «river») and 学校 (gakkō, «school»)

- the stems of most verbs and adjectives, such as 見 in 見る (miru, «see») and 白 in 白い (shiroi, «white»)

- the stems of many adverbs, such as 速 in 速く (hayaku, «quickly») and 上手 as in 上手に (jōzu ni, «masterfully»)

- most Japanese personal names and place names, such as 田中 (Tanaka) and 東京 (Tōkyō). (Certain names may be written in hiragana or katakana, or some combination of these, plus kanji.)

Some Japanese words are written with different kanji depending on the specific usage of the word—for instance, the word naosu (to fix, or to cure) is written 治す when it refers to curing a person, and 直す when it refers to fixing an object.

Most kanji have more than one possible pronunciation (or «reading»), and some common kanji have many. These are broadly divided into on’yomi, which are readings that approximate to a Chinese pronunciation of the character at the time it was adopted into Japanese, and kun’yomi, which are pronunciations of native Japanese words that correspond to the meaning of the kanji character. However, some kanji terms have pronunciations that correspond to neither the on’yomi nor the kun’yomi readings of the individual kanji within the term, such as 明日 (ashita, «tomorrow») and 大人 (otona, «adult»).

Unusual or nonstandard kanji readings may be glossed using furigana. Kanji compounds are sometimes given arbitrary readings for stylistic purposes. For example, in Natsume Sōseki’s short story The Fifth Night, the author uses 接続って for tsunagatte, the gerundive -te form of the verb tsunagaru («to connect»), which would usually be written as 繋がって or つながって. The word 接続, meaning «connection», is normally pronounced setsuzoku.

Kana[edit]

Hiragana[edit]

Hiragana (平仮名) emerged as a manual simplification via cursive script of the most phonetically widespread kanji among those who could read and write during the Heian period (794-1185). The main creators of the current hiragana were ladies of the Japanese imperial court, that used the script in the writing of personal communications and literature.

Hiragana is used to write the following:

- okurigana (送り仮名)—inflectional endings for adjectives and verbs—such as る in 見る (miru, «see») and い in 白い (shiroi, «white»), and respectively た and かった in their past tense inflections 見た (mita, «saw») and 白かった (shirokatta, «was white»).

- various function words, including most grammatical particles, or postpositions (joshi (助詞))—small, usually common words that, for example, mark sentence topics, subjects and objects or have a purpose similar to English prepositions such as «in», «to», «from», «by» and «for».

- miscellaneous other words of various grammatical types that lack a kanji rendition, or whose kanji is obscure, difficult to typeset, or considered too difficult to understand for the context (such as in children’s books).

- Furigana (振り仮名)—phonetic renderings of kanji placed above or beside the kanji character. Furigana may aid children or non-native speakers or clarify nonstandard, rare, or ambiguous readings, especially for words that use kanji not part of the jōyō kanji list.

There is also some flexibility for words with common kanji renditions to be instead written in hiragana, depending on the individual author’s preference (all Japanese words can be spelled out entirely in hiragana or katakana, even when they are normally written using kanji). Some words are colloquially written in hiragana and writing them in kanji might give them a more formal tone, while hiragana may impart a softer or more emotional feeling.[6] For example, the Japanese word kawaii, the Japanese equivalent of «cute», can be written entirely in hiragana as in かわいい, or with kanji as 可愛い.

Some lexical items that are normally written using kanji have become grammaticalized in certain contexts, where they are instead written in hiragana. For example, the root of the verb 見る (miru, «see») is normally written with the kanji 見 for the mi portion. However, when used as a supplementary verb as in 試してみる (tameshite miru) meaning «to try out», the whole verb is typically written in hiragana as みる, as we see also in 食べてみる (tabete miru, «try to eat [it] and see»).

Katakana[edit]

Katakana (片仮名) emerged around the 9th century, in the Heian period, when Buddhist monks created a syllabary derived from Chinese characters to simplify their reading, using portions of the characters as a kind of shorthand. The origin of the alphabet is attributed to the monk Kūkai.

Katakana is used to write the following:

- transliteration of foreign words and names, such as コンピュータ (konpyūta, «computer») and ロンドン (Rondon, «London»). However, some foreign borrowings that were naturalized may be rendered in hiragana, such as たばこ (tabako, «tobacco»), which comes from Portuguese. See also Transcription into Japanese.

- commonly used names of animals and plants, such as トカゲ (tokage, «lizard»), ネコ (neko, «cat») and バラ (bara, «rose»), and certain other technical and scientific terms, such as mineral names

- occasionally, the names of miscellaneous other objects whose kanji are rare, such as ローソク (rōsoku, «candle»)

- onomatopoeia, such as ワンワン (wan-wan, «woof-woof»), and other sound symbolism

- emphasis, much like italicisation in European languages.

Katakana can also be used to impart the idea that words are spoken in a foreign or otherwise unusual accent; for example, the speech of a robot.

Rōmaji[edit]

The first contact of the Japanese with the Latin alphabet occurred in the 16th century, during the Muromachi period, when they had contact with Portuguese navigators, the first European people to visit the Japanese islands. The earliest Japanese romanization system was based on Portuguese orthography. It was developed around 1548 by a Japanese Catholic named Anjirō.

The Latin alphabet is used to write the following:

- Latin-alphabet acronyms and initialisms, such as NATO or UFO

- Japanese personal names, corporate brands, and other words intended for international use (for example, on business cards, in passports, etc.)

- foreign names, words, and phrases, often in scholarly contexts

- foreign words deliberately rendered to impart a foreign flavour, for instance, in commercial contexts

- other Japanized words derived or originated from foreign languages, such as Jリーグ (jei rīgu, «J. League»), Tシャツ (tī shatsu, «T-shirt») or B級グルメ (bī-kyū gurume, «B-rank gourmet [cheap and local cuisines]»)

Arabic numerals[edit]

Arabic numerals (as opposed to traditional kanji numerals) are often used to write numbers in horizontal text, especially when numbering things rather than indicating a quantity, such as telephone numbers, serial numbers and addresses. Arabic numerals were introduced in Japan probably at the same time as the Latin alphabet, in the 16th century during the Muromachi period, the first contact being via Portuguese navigators. These numerals did not originate in Europe, as the Portuguese inherited them during the Arab occupation of the Iberian peninsula. See also Japanese numerals.

Hentaigana[edit]

Hentaigana (変体仮名), a set of archaic kana made obsolete by the Meiji reformation, are sometimes used to impart an archaic flavor, like in items of food (esp. soba).

Additional mechanisms[edit]

Jukujikun refers to instances in which words are written using kanji that reflect the meaning of the word though the pronunciation of the word is entirely unrelated to the usual pronunciations of the constituent kanji. Conversely, ateji refers to the employment of kanji that appear solely to represent the sound of the compound word but are, conceptually, utterly unrelated to the signification of the word.

Examples[edit]

Sentences are commonly written using a combination of all three Japanese scripts: kanji (in red), hiragana (in purple), and katakana (in orange), and in limited instances also include

Latin alphabet characters (in green) and Arabic numerals (in black):

Tシャツを3枚購入しました。

The same text can be transliterated to the Latin alphabet (rōmaji), although this will generally only be done for the convenience of foreign language speakers:

Tīshatsu o san—mai kōnyū shimashita.

Translated into English, this reads:

I bought 3 T-shirts.

All words in modern Japanese can be written using hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji, while only some have Kanji. Words that have no dedicated kanji may still be written with kanji by employing either ateji (like in man’yogana, から = 可良) or jukujikun, like in the title of とある科学の超電磁砲 (超電磁砲 being used to represent レールガン).

| Kanji | Hiragana | Katakana | Rōmaji | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 私 | わたし | ワタシ | watashi | I, me |

| 金魚 | きんぎょ | キンギョ | kingyo | goldfish |

| 煙草 or 莨 | たばこ | タバコ | tabako | tobacco, cigarette |

| 東京 | とうきょう | トーキョー | tōkyō | Tokyo, literally meaning «eastern capital» |

| none | です | デス | desu | is, am, to be (hiragana, of Japanese origin); death (katakana, of English origin) |

Although rare, there are some words that use all three scripts in the same word. An example of this is the term くノ一 (rōmaji: kunoichi), which uses a hiragana, a katakana, and a kanji character, in that order. It is said that if all three characters are put in the same kanji «square», they all combine to create the kanji 女 (woman/female). Another example is 消しゴム (rōmaji: keshigomu) which means «eraser», and uses a kanji, a hiragana, and two katakana characters, in that order.

Statistics[edit]

A statistical analysis of a corpus of the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun from the year 1993 (around 56.6 million tokens) revealed:[7]

|

|

Collation[edit]

Collation (word ordering) in Japanese is based on the kana, which express the pronunciation of the words, rather than the kanji. The kana may be ordered using two common orderings, the prevalent gojūon (fifty-sound) ordering, or the old-fashioned iroha ordering. Kanji dictionaries are usually collated using the radical system, though other systems, such as SKIP, also exist.

Direction of writing[edit]

Traditionally, Japanese is written in a format called tategaki (縦書き), which was inherited from traditional Chinese practice. In this format, the characters are written in columns going from top to bottom, with columns ordered from right to left. After reaching the bottom of each column, the reader continues at the top of the column to the left of the current one.

Modern Japanese also uses another writing format, called yokogaki (横書き). This writing format is horizontal and reads from left to right, as in English.

A book printed in tategaki opens with the spine of the book to the right, while a book printed in yokogaki opens with the spine to the left.

Spacing and punctuation[edit]