1

Гончаров

Новый русско-английский словарь > Гончаров

2

Гончаров

Русско-английский словарь Wiktionary > Гончаров

3

Иван Гончаров

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Иван Гончаров

4

астма гончаров

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > астма гончаров

5

бронхит гончаров

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > бронхит гончаров

6

астма гончаров

Русско-английский экологический словарь > астма гончаров

7

В-235

ДО СЕДЫХ ВОЛОС (дожить и т. п.)

PrepP

Invar

adv

fixed

WO

(of a person) (to have lived

etc

) until old age

till one goes (grows) gray

till one’s hair turns (begins to turn) gray

into (one’s) old age.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > В-235

8

Г-82

НАВОСТРИТЬ ГЛАЗА на кого-что

highly coll

VP

subj

: human to look attentively, watchfully (at

s.o.

or

sth.

): X навострил глаза на Y-a — X gazed intently at Y

X fixed his eyes on Y

X was all eyes.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Г-82

9

Г-100

ТАРАЩИТЬ (ВЫТАРАЩИТЬ, ПУЧИТЬ, ВЫПУЧИТЬ, ВЫКАТЫВАТЬ/ВЫКАТИТЬ) ГЛАЗА (на кого-что)

highly coll

ПИЛИТЬ (ВЫПЯЛИТЬ, ЛУПИТЬ, ВЫ ЛУПИТЬ) ГЛАЗА

substand

ПИЛИТЬ (ВЫПЯЛИТЬ, ПУЧИТЬ, ВЫПУЧИТЬ, ЛУПИТЬ, ВЫЛУПИТЬ) ЗЕНКИ (БЕЛЬМА)

substand

, rude

VP

subj

: human to look (at

s.o.

or

sth.

) intently, raptly, opening one’s eyes wide

X таращил глаза на Y-a » X was staring at Y (, wide-eyed)

X was gawking at Y

X’s eyes were popping (bugging) out (of X’s head)

X’s eyes were bulging (goggling, bugging) (with fright (in disbelief

etc

))

(

usu.

of looking at

s.o.

or

sth.

one wants

often used when making advances to a person of the opposite sex) X was eyeing (ogling) Y

(in questions and

Neg

Imper) ты что пялишь глаза? » why are you staring like that?

her eyes are popping out, she realizes we’re talking about her, but she can’t make it out…» (3a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Г-100

10

Г-126

В ГЛАЗАХ чьих, кого

PrepP

Invar

the resulting

PrepP

is sent

adv

according to

s.o.

‘s perception or opinion

in

s.o.

‘s eyes (estimation, opinion)

as

s.o.

sees it

(in limited contexts)

s.o.

looks on

s.o. sth.

as (on)…

to

s.o.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Г-126

11

Д-25

ДАРОМ ЧТО

coll

subord Conj

, concessive) notwithstanding (the fact that): (even) though

although

despite (in spite of) (the fact that (

s.o.

‘s doing

sth. etc

))

(in limited contexts) it doesn’t matter that…

I (you

etc

) may…but

даром что профессор (умный и т. п.) = professor (intelligent

etc

) or not

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Д-25

12

Д-133

TO ЛИ ДЕЛО

coll

,

approv

(

Invar

subj-compl

with бытьв (

subj

: any noun), pres only, or Particle

initial position only

fixed

WO

or

sth.

is entirely different from, and better than, someone or something else (used to express approval, a positive evaluation of the person, thing

etc

that is about to be named as opposed to the one named previously): то ли дело X = X is quite another matter

X is a different story

thing X

thing X is quite a different thing

X is not like that at all

X is not at all like

NP

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Д-133

13

З-201

СКАЛИТЬ ЗУБЫ

substand

VP

subj

: human to react to

sth.

s.o.

‘s behavior, words

etc

) by smiling, laughing

etc

(sometimes as a form of mockery): что зубы скалишь? — what are you grinning (laughing, smiling, snickering, smirking

etc

) at?

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > З-201

14

М-271

ЧТО ЕСТЬ (БЫЛО) МОЧИ (СИЛЫ, СИЛ)

ВО ВСЮ МОЧЬ

ИЗО ВСЕЙ МОЧИ all

coll

AdvP

or

PrepP

these forms only

adv

(

intensif

)

more often used with

impfv

verbs

fixed

WO

1. (to do

sth.

) with the utmost possible exertion, intensity

with all one’s might

as hard as one can

for all one is worth.

2. бежать, мчаться и т. п. — (to run, race

etc

) very fast

at full (top) speed

(at) full tilt

for all one is worth

as fast as one can

as fast as onefc legs can carry one.

3. кричать, орать, гудеть и т. п. М-271 (to shout, yell, blare

etc

) very loudly

at the top of one’s voice (lungs)

with all one’s (its) might

(of a radio, television

etc

) (at) full blast.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > М-271

15

Н-177

НА ШИРОКУЮ НОГУ

coll

НА БОЛЬШУЮ НОГУ

obs

PrepP

these forms only

adv

fixed

WO

1. жить, поставить что -ит.п. Also: НА БАРСКУЮ НОГУ

obs

(to live, set up one’s household

etc

) luxuriously, sparing no expense

in grand (high) style

on a grand scale

(in limited contexts) he (she

etc

) really knows how to live!

2. организовать, поставить что и т. п. Н-177 (to organize, set up

sth. etc

) grandly, expansively, impressively

etc

on a grand (large, big) scale

in a big way.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Н-177

16

Т-144

…ДА И ТОЛЬКО

coll

(used as Particle

Invar

fixed

WO

1. used when calling or describing some person, thing

etc

by some name to show that the person, thing

etc

has all the applicable characteristics of that name: (a) real (regular, sheer, total)

NP

(a)

NP

, pure and simple

a

NP

NP

2. used to add emphasis to the named action

one just (simply) (does

sth.

).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Т-144

17

Ч-180

ЧТO Ж(Е)

coll

(Particle

Invar

1. Also: ЧЕГО Ж(Е)

highly coll

ЧТО (ЖЕ) ЗТО

coll

(used in questions and

subord

clauses) for what reason?: why?

what for?

how come?

2. used to introduce questions, often rhetorical ones, or exclamations (when the question or exclamation is positively phrased, a negative response is expected

when the question or exclamation is negatively phrased, a confirmation or expression of agreement is expected)

what

(and) so

(in limited contexts) you don’t expect (think)?

3. used in a dialogue to induce one’s interlocutor to answer a question or give an explanation

well

now

(and) what about it?

(and) what of it?

(in limited contexts)…I suppose.

4. Also: НУ ЧТО Ж(Е)

coll

used to introduce a remark expressing concession, agreement

well (then)

all right then.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Ч-180

18

Ч-182

ЧТО ЗА…

coll

(Particle

Invar

1. (used in questions and

obj

or

subj

clauses) used when asking the interlocutor to describe the character, personality

etc

of the named person(s), or the nature, characteristics

etc

of the named thing

what kind (sort) of (a)

NP

what is (

s.o. sth.

) like?

what is (

s.o. sth.

)?

2. (used in exclamations expressing the speaker’s feeling about or emotional reaction to some person, thing, or phenomenon) (

s.o.

or

sth.

is) very (pretty, nice, revolting

etc

): what a

NP

!

what a beautiful (terrible

etc

)

NP

(he (it

etc

)) is such a

NP

(he (she

etc

)) is such an exquisite (beautiful

etc

)

NP

(when the Russian

NP

is translated by an

AdjP

) how

AdjP

.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Ч-182

19

Ч-191

ЧТО ТЫ (ВЫ)!

ДА ЧТО ТЫ (ВЫ)! all

coll

Interj

these forms only)

1. used to express surprise, bewilderment, fright

etc

you don’t say (so)!

what do you mean!

good Lord!

how can that be!

really!

is that so!

2. Also: НУ ЧТО ТЫ (ВЫ)!

coll

used to express a skeptical or sarcastic reaction to the interlocutor’s statement

come (go) on!

oh come!

good Lord (,…indeed)!

what are you talking about!

the things you say!

(in limited contexts) oh, get away with you!

3. Also: НУ (НЕТ,) ЧТО ТЫ (ВЫ)!

coll

used to express one’s disagreement with or a denial of some statement, or as a negative answer to a question

what do you mean!

what are you saying!

what are you talking about!

(no,) not at all

(no,) itfe out of the question

good heavens, no!

certainly not

of course not.

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Ч-191

20

бог весть

I

• БОГ <ГОСПОДЬ, АЛЛАХ> (ЕГО <тебя и т.п.> ЗНАЕТ < ВЕДАЕТ>; БОГ ВЕСТЬall

coll

[

VPsubj

; these forms only;

usu.

the main clause in a complex

sent

or

indep. sent

; fixed

WO

]

=====

⇒ no one knows, it is impossible (for

s.o.

) to know:

— God <(the) Lord, heaven, goodness> (only) knows;

— God alone knows.

♦ «Кто же я таков, по твоему разумению?» — «Бог тебя знает; но кто бы ты ни был, ты шутишь опасную шутку» (Пушкин 2). «And who am I then, in your opinion?» «God only knows; but whoever you may be, you’re playing a dangerous game» (2a).

♦…Он ездит и в свет, и читает: когда он успевает — бог весть (Гончаров 1)….There was his social life and his reading-heaven only knows how he found the time! (1b).

♦ Родители его были дворяне, но столбовые или личные — бог ведает (Гоголь 3). God alone knows whether his parents, who were of the nobility, were so by descent or personal merit (3d).

II

[

VPsubj

; these forms only; fixed

WO

]

=====

1. [

usu.

the main clause in a complex

sent

; when

foll. by

an

Adv

, may be used as

adv

]

⇒ no one knows (who, what, how

etc

):

— God <(the) Lord, heaven, goodness> (only) knows (who <what, how etc>).

♦ Выкопали всё, разузнали его [Чичикова] прежнюю историю. Бог весть, откуда всё это пронюхали… (Гоголь 3). Everything was dug up and all the past history of his [Chichikov’s] life became known. God only knows how they got on the scent of it… (3a).

♦ Бог весть, почему нервничали встречавшие (Свирский 1). Heaven knows why the reception party should have been so nervous (1a).

♦ Дом Обломовых был когда-то богат и знаменит в своей стороне, но потом, бог знает отчего, всё беднел, мельчал… (Гончаров 1). The Oblomov family had once been rich and famous in its part of the country, but afterwards, goodness only knows why, it had grown poorer, lost all its influence… (1a).

2. [used as

NP

(when

foll. by

кто, что),

AdjP

(when

foll. by

какой), or

AdvP

(when

foll. by

где, куда

etc

)]

⇒ used to express a strong emotional reaction-anger, indignation, bewilderment

etc

:

— God <(the) Lord, heaven, goodness> (only) knows (who <what, how etc>)!;

— what sort < kind> of (a) [

NP

] is he (she, that etc)!;

— [in limited contexts;

— said with ironic intonation] some [

NP

] (I must say)!

♦ «Да ведь она тоже мне двоюродная тётка». — «Она вам тётка ещё бог знает какая: с мужниной стороны…» (Гоголь 3). «But, you know, she is a cousin of mine.» «What sort of a cousin is she to you…only on your husband’s side…» (3d).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > бог весть

См. также в других словарях:

-

Гончаров — Иван Александрович (1812 1891) знаменитый русский писатель. Р. в богатой купеческой семье, в Симбирске. В 1831 поступил в Московский университет, в 1834 его окончил и начал службу в канцелярии симбирского губернатора. С 1835 служил в Министерстве … Литературная энциклопедия

-

Гончаров И.А. — Гончаров И.А. Гончаров Иван Александрович (1812 1891) Русский писатель. Афоризмы, цитаты Гончаров И.А. биография • Литература язык, выражающий все, что страна думает, чего желает, что она знает и чего хочет и должна знать. • Глупая красота не… … Сводная энциклопедия афоризмов

-

Гончаров — Гончаров. 2. употр. при восклицании в знач. вот (см. вот во 2 знач.). Ай, конь хваленый! то то диво! Крылов. То то было радости! Салтыков Щедрин. То то дядюшка! То то отец родной! Фонвизин. Б То же в знач. поэтому то, вот почему. То то я заметила … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

Гончаров — Гончаров, Иван Александрович Гончаров, Леонид Георгиевич … Морской биографический словарь

-

ГОНЧАРОВ — Андрей Александрович (родился в 1918), режиссер, педагог. С 1958 главный режиссер Московского драматического театра, с 1967 Московского театра имени Владимира Маяковского. Для Гончарова характерны яркая, энергичная режиссура, стремление к… … Современная энциклопедия

-

Гончаров — Гончаров: Гончаров, Андрей Александрович (1918 2001) режиссёр Гончаров, Андрей Дмитриевич (1903 1979) художник график Гончаров, Борис Прокопьевич (род. 1934) литературовед Гончаров, Валерий Владимирович (род. 1977) … … Википедия

-

Гончаров — I Гончаров Андрей Александрович (р. 2.1.1918, село Синицы Московской области), советский режиссёр, народный артист СССР (1977). Член КПСС с 1943. В 1941 окончил ГИТИС. Работал в 1 м фронтовом театре ВТО, Московском театре Сатиры (1944 51) … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

ГОНЧАРОВ — 1. ГОНЧАРОВ Андрей Александрович (род. 1918), режиссёр, народный артист СССР (1977), Герой Социалистического Труда (1987). Работал (с 1942) в Московском театре сатиры, Московском театре им. М. Н. Ермоловой. С 1958 главный режиссёр Московского… … Русская история

-

ГОНЧАРОВ — [Гончар, Ганчар] Иосиф Семенович (3.11.1796 (1793?), сел. Сарикёй (тур. Сарыкёй), Добруджа, ныне Румыния 1879 (1880?), г. Хвалынск Саратовской губ.), атаман некрасовцев, старообрядческий деятель, способствовал учреждению Белокриницкой иерархии.… … Православная энциклопедия

-

Гончаров — Иван Александрович (1812– 1891) выдающийся русский писатель. Родился в Симбирске (ныне Ульяновск) в семье зажиточного купца. После окончания словесного отделения Московского университета поступает в качестве переводчика на службу в департамент… … Вся Япония

-

Гончаров Ив. Ал.-др. — ГОНЧАРОВ Ив. Ал. др. (1812 91) писатель. Род. в Симбирске в купеч. семье. Окончил словесный ф т Моск. ун та (1834) Служил чиновником на родине, затем в С. Петербурге. С 1835 сблизился с семьей художника Н. А. Майкова, был дом. учителем его детей… … Российский гуманитарный энциклопедический словарь

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «гончаров» на английский

Goncharov

potters

Goncearov

pottery

Сергей Михайлович гончаров (1862 — 1935) был членом семьи Натальи Николаевны Гончаровой, жены великого русского поэта, Александра Сергеевича Пушкина.

Sergey Mikhailovich Goncharov (1862-1935) belonged to the family of Natalia Nikolaevna Goncharova, spouse of Russian great poet Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin.

Общественность будет также иметь возможность участвовать в семинарах и посещать лекции гончаров.

The public will also have the opportunity to participate in workshops and attend lectures of potters.

Об участии местных гончаров в этом производстве свидетельствуют также клейма мастеров с галльскими именами.

Participation of local potters in this production is demonstrated also by brands of masters with Gallic names.

Я работала в мастерской, где было несколько гончаров.

and so I worked in a shop where there were several potters.

мастер-классах гончаров и рисовальщиц, кузнецов;

master classes of potters and draftsmen, blacksmiths;

По этой причине его мелодии часто называют «soleares alfareras» (солеарес гончаров).

For this reason, these styles are often called «soleares alfareras» (potters‘ soleares).

Вы также можете смотреть гончаров и стеклодувов на работе в своих студиях.

You can also watch potters and glassblowers at work in their studios.

Гончарный круг был изобретен около 7000 лет назад и стал выбором для многих гончаров.

The potter’s wheel was invented about 7000 years ago and has become the method of choice for many potters.

Посетив ее, вы узнаете, как добывают жемчуг, увидите за работой ткачей и гончаров, посетите настоящий восточный базар.

Having visited this place, you’ll learn how to extract pearls, see the work of the weavers and potters, and will visit real bazaar.

Каждую субботу и воскресение ярмарка становится домом для сотен художников, ювелиров, гончаров и других мастеров.

Every weekend the fair becomes home to hundreds of artists, jewelers, potters and other craftsmen.

У викторианских гончаров была большая дешевая рабочая сила.

Victorian potters had a large cheap labour force.

Огромные успехи в изготовлении горшков были результатом терпеливых проб и ошибок тысяч гончаров за тысячи лет.

The immense strides in the making of pots were the result of patient trial and error by thousands of potters over thousands of years.

После 36 туров у «гончаров» в активе 30 очков и предпоследнее 19-е место в турнирной таблице английского футбольного первенства.

After 36 rounds the potters in the asset 30 points and the penultimate 19th place in the standings of the English football championship.

Майя были одинаково квалифицированны в качестве ткачей и гончаров.

The Maya were equally skilled as weavers and potters.

Те, кто преуспел, были среди первых американских гончаров студии.

Those who succeeded were among America’s first studio potters.

Создание мягкого фарфора начинается во время первых попыток европейских гончаров копировать китайский фарфор при помощи смесей глины и фритты.

Soft-paste porcelains date back from the early attempts by European potters to replicate Chinese porcelain by using mixtures of clay and frit.

11.00 — 17.00 — Выставка-ярмарка народных умельцев с мастер-классами гончаров, вышивальщиц и других.

At 11.00 — 17.00 Exhibition-fair of folk craftsmen with master classes of potters, embroiderers, etc.

В целом в экспозиции представлены изделия примерно двадцати латгальских гончаров.

The exhibition will display works of about 20 Latgalian potters.

Уникальное переплетение различных видов искусств привлекло более тысячи скульпторов, гончаров, писателей, режиссеров, композиторов, деятелей культуры со всех континентов.

The amalgamation of these art forms has attracted more than a thousand sculptors, potters, writers, directors, composers and other cultural workers from all continents.

Целый район города занят мастерскими местных гончаров, которые с утра до вечера изготовляют кувшины, горшки, вазы, подсвечники, копилки и прочие глиняные изделия.

The whole district of the city is occupied by the workshops of local potters who, from morning to evening, make jugs, pots, vases, candlesticks, piggy banks and other clay products.

Результатов: 432. Точных совпадений: 432. Затраченное время: 73 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

|

Ivan Goncharov |

|

|---|---|

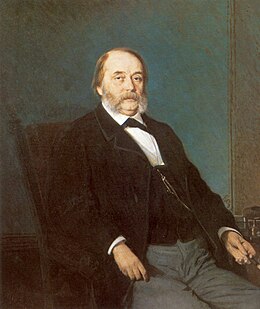

Portrait of Goncharov by Ivan Kramskoi,1874 |

|

| Born | Ivan Aleksandrovich Goncharov 18 June 1812 Simbirsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 27 September 1891 (aged 79) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University (1835) |

| Period | 1847–1871 |

| Notable works | The Same Old Story (1847) Oblomov (1859) The Precipice (1869) |

| Signature | |

|

Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov (,[1] also ;[2] Russian: Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Гончаро́в, tr. Iván Aleksándrovich Goncharóv, IPA: [ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪkˈsandrəvʲɪdʑ ɡənʲtɕɪˈrof]; 18 June [O.S. 6 June] 1812 – 27 September [O.S. 15 September] 1891[3]) was a Russian novelist best known for his novels The Same Old Story (1847), Oblomov (1859), and The Precipice (1869, also translated as Malinovka Heights). He also served in many official capacities, including the position of censor.

Goncharov was born in Simbirsk into the family of a wealthy merchant; as a reward for his grandfather’s military service, they were elevated to gentry status.[4] He was educated at a boarding school, then the Moscow College of Commerce, and finally at Moscow State University. After graduating, he served for a short time in the office of the Governor of Simbirsk, before moving to Saint Petersburg where he worked as government translator and private tutor, while publishing poetry and fiction in private almanacs. Goncharov’s first novel, A Common Story, was published in Sovremennik in 1847.

Goncharov’s second and best-known novel, Oblomov, was published in 1859 in Otechestvennye zapiski. His third and final novel, The Precipice, was published in Vestnik Evropy in 1869. He also worked as a literary and theatre critic. Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote a memoir called An Uncommon Story, in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost Ivan Turgenev, of having plagiarized his works and prevented him from achieving European fame. The memoir was published in 1924. Fyodor Dostoevsky, among others, considered Goncharov an author of high stature. Anton Chekhov is quoted as stating that Goncharov was «…ten heads above me in talent.»

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Ivan Goncharov was born in Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk). His father Alexander Ivanovich Goncharov was a wealthy grain merchant and a state official who served several terms as mayor of Simbirsk.[5] The family’s big stone manor in the town center occupied a large area and had all the characteristics of a rural manor, with huge barns (packed with wheat and flour) and numerous stables.[6] Alexander Ivanovich died when Ivan was seven years old. He was educated first by his mother, Avdotya Matveevna, and then his godfather Nikolay Nikolayevich Tregubov, a nobleman and a former Russian Navy officer.[5]

Tregubov, a man of liberal views and a secret Masonic lodge member,[6] who knew some of the Decembrists personally, and who was one of the most popular men amongst the Simbirsk intelligentsia, was a major early influence upon Goncharov, who particularly enjoyed his seafaring stories.[7] With Tregubov around, Goncharov’s mother could focus on domestic affairs. «His servants, cabmen, the whole household merged with ours; it was a single family. All the practical issues were now mother’s, and she proved to be an excellent housewife; all the official duties were his,» Ivan Goncharov remembered.[6]

Education[edit]

Plaque on the house in 20 Goncharova street in Ulyanovsk where Goncharov was born in 1812

In 1820–1822 Goncharov studied at a private boarding-school owned by Rev. Fyodor S. Troitsky. It was here that he learned the French and German languages and started reading European writers, borrowing books from Troitsky’s vast library.[5] In August 1822 Ivan was sent to Moscow and entered the College of Commerce. There he spent eight unhappy years, detesting the low quality of education and the severe discipline, taking solace in self-education. «My first humanitarian and moral teacher was Nikolai Karamzin,» he remembered. Then Pushkin came as a revelation; the serial publication of his poem Evgeny Onegin captured the young man’s imagination.[6] In 1830, Goncharov decided to quit the college and in 1831 (having missed one year because of a cholera outbreak in Moscow) he enrolled in Moscow State University’s Philology Faculty to study literature, arts, and architecture.[7]

At the University, with its atmosphere of intellectual freedom and lively debate, Goncharov’s spirit thrived. One episode proved to be especially memorable: when his then idol Alexander Pushkin arrived as a guest lecturer to have a public debate with professor Mikhail T. Katchenovsky on the authenticity of The Tale of Igor’s Campaign. «It was as if sunlight lit up the auditorium. I was enchanted by his poetry at the time…it was his genius that formed my aesthetic ideas – although the same, I think, could be said of all the young people of the time who were interested in poetry,» Goncharov wrote.[8] Unlike Alexander Herzen, Vissarion Belinsky, or Nikolay Ogaryov, his fellow Moscow University students, Goncharov remained indifferent to the ideas of political and social change that were gaining popularity at the time. Reading and translating were his main occupations. In 1832, the Telescope magazine published two chapters of Eugene Sue’s novel Atar-Gull (1831), translated by Goncharov. This was his debut publication.[7]

In 1834, Goncharov graduated from the University and returned home to enter the chancellery of Simbirsk governor A. M. Zagryazhsky. A year later, he moved to Saint Petersburg and started working as a translator at the Finance Ministry’s Foreign commerce department. Here, in the Russian capital, he became friends with the Maykov family and tutored both Apollon Maykov and Valerian Maykov in the Latin language and in Russian literature.[6] He became a member of the elitist literary circle based in the Maykovs’ house and attended by writers like Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Dmitry Grigorovich. The Maykovs’ almanac Snowdrop featured many of Goncharov’s poems, but he soon stopped dabbling in poetry altogether. Some of those early verses were later incorporated into the novel A Common Story as Aduev’s writings, a sure sign that the author had stopped taking them seriously.[6][7]

Literary career[edit]

Goncharov’s first piece of prose appeared in an issue of Snowdrop, a satirical novella called Evil Illness (1838), ridiculing romantic sentimentalism and fantasizing. Another novella, A Fortunate Blunder, a «high-society drama» in the tradition set by Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoevsky, and Vladimir Sollogub,[6] tinged with comedy, appeared in another privately published almanac, Moonlit Nights, in 1839.[7] In 1842 Goncharov wrote an essay called Ivan Savvich Podzhabrin, a natural school psychological sketch. Published in Sovremennik six years later, it failed to make any impact, being very much a period piece, but later scholars reviewed it positively, as something in the vein of the Nikolay Gogol-inspired genre known as the «physiological essay», marked by a fine style and precision in depicting the life of the common man in the city.[7] In the early 1840s Goncharov worked on a novel called The Old People, but the manuscript has been lost.[6]

The Same Old Story[edit]

Goncharov’s first novel, The Same Old Story, was published in Sovremennik in 1847. It dealt with the conflict between the excessive romanticism of a young Russian nobleman who has recently arrived in Saint Petersburg from the provinces, and the sober pragmatism of the emerging commercial class of the capital. The Same Old Story polarized critics and made its author famous. The novel was a direct response to Vissarion Belinsky’s call for exposing a new type, that of the complacent romantic, common at the time; it was lavishly praised by the famous critic as one of the best Russian books of the year.[6] The term aduyevschina (after the novel’s protagonist Aduyev) became popular with reviewers who saw it as synonymous with vain romantic aspirations. Leo Tolstoy, who liked the novel, used the same word to describe social egotism and the inability of some people to see beyond their immediate interests.[7]

In 1849 Sovremennik published Oblomov’s Dream, an extract from Goncharov’s future second novel Oblomov, (known under the working title The Artist at the time), which worked well on its own as a short story. Again it was lauded by the Sovremennik staff. Slavophiles, while giving the author credit for being a fine stylist, reviled the irony aimed at patriarchal Russian ways.[9] The novel itself, though, appeared only ten years later, preceded by some extraordinary events in Goncharov’s life.[7]

In 1852 Goncharov embarked on a long journey through England, Africa, Japan, and back to Russia, on board the frigate Pallada, as a secretary for Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin, whose mission was to inspect Alaska and other distant outposts of the Empire, and also to establish trade relations with Japan. The log-book which it was Goncharov’s duty to keep served as a basis for his future book. He returned to Saint Petersburg on 25 February 1855, after traveling through Siberia and the Urals, this continental leg of the journey lasting six months. Goncharov’s travelogue, Frigate «Pallada» («Pallada» is the Russian spelling of «Pallas»), began to appear, first in Otechestvennye Zapiski (April 1855), then in The Sea Anthology and other magazines.[6]

In 1858 Frigate «Pallada» was published as a separate book; it received favourable reviews and became very popular. For the mid-19th century Russian readership the book came as a revelation, providing new insights into the world, hitherto unknown. Goncharov, a well-read man and a specialist in the history and economics of the countries he visited, proved to be a competent and insightful writer.[6] He warned against seeing his work as any kind of political or social statement, insisting it was a subjective piece of writing, but critics praised the book as a well-balanced, unbiased report, containing valuable ethnographic material, but also some social critique. Again, the anti-romantic tendency prevailed: it was seen as part of the polemic with those Russian authors who tended to romanticize the «pure and unspoiled» life of the uncivilized world. According to Nikolay Dobrolyubov, The Frigate Pallada «bore the hallmark of a gifted epic novelist.»[7]

Oblomov[edit]

Title page of the 1915 English translation of Oblomov

Throughout the 1850s Goncharov worked on his second novel, but the process was slow for many reasons. In 1855 he accepted the post of censor in the Saint Petersburg censorship committee. In this capacity, he helped publish important works by Ivan Turgenev, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Pisemsky, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a fact that brought resentment from some of his bosses. According to Pisemsky, Goncharov was officially reprimanded for permitting his novel A Thousand Souls to be published. Despite all this, Goncharov became the target of many satires and received a negative mention in Herzen’s Kolokol. «One of the best Russian authors shouldn’t have taken this sort of job upon himself,» critic Aleksander Druzhinin wrote in his diary.[6] In 1856, as the official publishing policy hardened, Goncharov quit.[7]

In the summer of 1857 Goncharov went to Marienbad for medical treatment. There he wrote Oblomov, almost in its entirety. «It might seem strange, even impossible that in the course of one month the whole of the novel might be written… But it’d been growing in me for several years, so what I had to do then was just sit and write everything down,» he later remembered.[6] Goncharov’s second novel Oblomov was published in 1859 in Otechestvennye Zapiski. It had evolved from the earlier «Oblomov’s Dream», which was later incorporated into the finished novel as Chapter 9. The novel caused much discussion in the Russian press, introduced another new term, oblomovshchina, to the literary lexicon and is regarded as a Russian classic.[7]

In his essay What Is Oblomovshchina? Nikolay Dobrolyubov provided an ideological background for the type of Russia’s ‘new man’ exposed by Goncharov. The critic argued that, while several famous classic Russian literary characters – Onegin, Pechorin, and Rudin – bore symptoms of the ‘Oblomov malaise’, for the first time one single feature, that of social apathy, a self-destructive kind of laziness and unwillingness to even try and lift the burden of all-pervading inertia, had been brought to the fore and subjected to a thorough analysis.[6]

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, among others, considered Goncharov a noteworthy author of high stature. Anton Chekhov is quoted as stating that Goncharov was «…ten heads above me in talent.»[10] Turgenev, who fell out with Goncharov after the latter accused him of plagiarism (specifically of having used some of the characters and situations from The Precipice, whose plan Goncharov had disclosed to him in 1855, in Home of the Gentry and On the Eve), nevertheless declared: «As long as there is even one Russian alive, Oblomov will be remembered!»[11]

The Precipice[edit]

A moderate conservative[12] at heart, Goncharov greeted the Emancipation reform of 1861, embraced the well-publicized notion of the government’s readiness to «be at the helm of [social] progress», and found himself in opposition to the revolutionary democrats. In the summer of 1862 he became an editor of Severnaya Potchta (The Northern Post), an official newspaper of the Interior Ministry, and a year later returned to the censorship committee.[6]

In this second term Goncharov proved to be a harsh censor: he created serious problems for Nekrasov’s Sovremennik and Russkoye Slovo, where Dmitry Pisarev was now a leading figure. Openly condemning ‘nihilistic’ tendencies and what he called «pathetic, imported doctrines of materialism, socialism, and communism», Goncharov found himself the target of heavy criticism.[6] In 1863 he became a member of the State Publishing Council and two years later joined the Russian government’s Department of Publishing. All the while he was working on his third novel, The Precipice, which came out in extracts: Sophia Nikolayevna Belovodova (a piece he himself was later skeptical about), Grandmother and Portrait.[7]

In 1867, Goncharov retired from his censorial position to devote himself entirely to writing The Precipice, a book he later called «my heart’s child», which took him twenty years to finish. Towards the end of this tormenting process Goncharov spoke of the novel as a «burden» and an «insurmountable task» that blocked his development and made him unable to advance as a writer. In a letter to Turgenev he confessed that, after finishing Part Three, he had toyed with the idea of abandoning the whole project.[6]

In 1869 The Precipice, a story of the romantic rivalry among three men, condemning nihilism as subverting the religious and moral values of Russia, was published in Vestnik Evropy.[7] Later critics came to see it as the final part of a trilogy, each part introducing a character typical of Russian high society of a certain period: first Aduev, then Oblomov, and finally Raisky, a gifted man, his artistic development halted by «lack of direction». According to scholar S. Mashinsky, as a social epic, The Precipice was superior to both A Common Story and Oblomov.[6]

The novel had considerable success, but the leftist press turned against its author. Saltykov-Shchedrin in Otechestvennye Zapiski («The Street Philosophy», 1869), compared it unfavorably to Oblomov. While the latter «had been driven by ideas assimilated by its author from the best men of the 1840s», The Precipice featured «a bunch of people wandering to and fro without any sense of direction, their lines of action having neither beginning nor end,» according to the critic.[7] Yevgeny Utin in Vestnik Evropy argued that Goncharov, like all writers of his generation, had lost touch with the new Russia.[13] The controversial character Mark Volokhov, as leftist critics saw it, had been concocted to condemn ‘nihilism’ again, thus making the whole novel ‘tendentious’. Yet, as Vladimir Korolenko later wrote, «Volokhov and all things related to him will be forgotten, as Gogol’s Correspondence has been forgotten, while Goncharov’s huge characters will remain in history, towering over all of those spiteful disputes of old.»[6]

Later years[edit]

Goncharov planned a fourth novel, set in the 1870s, but it failed to materialize. Instead he became a prolific critic, providing numerous theater and literature reviews; his «Myriad of Agonies» (Milyon terzaniy, 1871) is still regarded as one of the best essays on Alexandr Griboyedov’s Woe from Wit.[7] Goncharov also wrote short stories: his Servants of an Old Age cycle as well as «The Irony of Fate», «Ukha» and others, described the life of rural Russia. In 1880 the first edition of The Complete Works of Goncharov was published. After the writer’s death, it became known that he had burnt many later manuscripts.[7]

Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote an unusual memoir called An Uncommon Story, in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost Ivan Turgenev, of having plagiarized his works and prevented him from achieving European fame. Some critics claimed that the book was the product of an unstable mind,[14] while others praised it as an eye-opening, if controversial piece of writing.[15] It wasn’t published until 1924.[16]

Goncharov, who never married, spent his last days absorbed in lonely and bitter recriminations because of the negative criticism some of his work had received.[17] He died in Saint Petersburg on 27 September 1891, of pneumonia.[citation needed] He was buried at the Novoye Nikolskoe Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. In 1956 his ashes were moved to the Volkovo Cemetery in Leningrad.[18]

Selected bibliography[edit]

- The Same Old Story (Обыкновенная история, 1847)[19]

- Ivan Savich Podzhabrin (1848)[20]

- Frigate «Pallada» (Фрегат «Паллада», 1858)

- «Oblomov’s Dream. An Episode from an Unfinished Novel», short story, later Chapter 9 in the 1859 novel as «Oblomov’s Dream» («Сон Обломова», 1849)[21]

- Oblomov (1859)[22]

- The Precipice (Обрыв, 1869)[23]

References[edit]

- ^ «Goncharov, Ivan». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.[dead link]

- ^ «Goncharov». Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Goncharov, Ivan Alexandrovich» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Oblomov, Penguin Classics, 2005. p. ix.

- ^ a b c Potanin, G.N. «Remembering I.A.Goncharov. Commentaries. Pp. 263–265». I.A.Goncharov Remembered by Contemporaries. Leningrad, 1969. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Mashinsky, S. Goncharov and His Legacy. Foreword to The Works of I.A.Goncharov in 6 Volumes. Ogonyok’s Library. Pravda Publishers. Moscow, 1972. Pp. 3–54

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p «I.A.Goncharov. Biobibliography». Russian Writers. Biobibliographical dictionary. Ed. P.A.Nikolayev. Vol.1 Moscow, Prosveshcheniye Publishers. 1990. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Goncharov, I.A. The Works of… Moscow, 1980. Vol. 7. P. 241).

- ^ Moskvityanin. 1849. No.11. Vol.1. Section 4.

- ^ Gayla Diment’s introduction to Stephen Pearl’s translation of Oblomov. New York: Bunim & Brown, 2006)

- ^ Quoted in N. F. Budanova’s «The confessions of Goncharov. The Unfinished Story. Literaturnoe Nasledstvo, 102 (2000), p. 202.

- ^ Pritchett, V.S. (7 March 1974). «Saint of Inertia». New York Review of Books.

- ^ Utin, Ye.I. Literature Debates of Our Times. Vestnik Evropy. 1869, No. 11.

- ^ «Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov». Gale Encyclopedia of Biography. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ «The Uncommon Story. The True Facts. Preface be ed. N.F.Budanova». feb-web.ru. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ D. S. Mirsky, A History of Russian Literature (New York: Vintage, 1958)

- ^ Cornwell, Neil; Christian, Nicole (1998). Reference Guide to Russian Literature. Taylor & Francis. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-884964-10-7.

- ^ Ward, Charles Alexander (1989). Moscow and Leningrad: Writers, painters, musicians and their gathering places. K. G. Saur Verlag GmbH. p. 89. ISBN 9783598108341. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Goncharov, Ivan Aleksandrovich (27 September 2018). «A common story, a novel». London, London Book Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Moser, Charles (30 April 1992). The Cambridge History of Russian Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780521425674. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Stilman, Leon (1 January 1948). «Oblomovka Revisited». American Slavic and East European Review. 7 (1): 45–77. doi:10.2307/2492118. JSTOR 2492118.

- ^ Goncharov, Ivan Aleksandrovich (27 September 2018). «Oblomov». Macmillan – via Google Books.

- ^ Goncharov, Ivan Aleksandrovich (27 September 2018). «The precipice». London, Hodder and Stoughton – via Internet Archive.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Works by Ivan Aleksandrovich Goncharov at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ivan Goncharov at Internet Archive

- Works by Ivan Goncharov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Petri Liukkonen. «Ivan Goncharov». Books and Writers

Мой отец занимается керамикой.

Он ‘гончар‘.

Твой отец гончар?

My father makes pottery.

He’s a ‘potter‘.

Your father is a potter?

Он ‘гончар’.

Твой отец гончар?

Да.

He’s a ‘potter’.

Your father is a potter?

Yes.

У фарфора Kiyomizu гончар и художник — разные.

Гончар создаёт фарфор, а художник рисует на нём по отдельности.

То есть сначала гончар, а потом художник.

For Kiyomizu porcelain, its potter is different from its painter.

The potter makes the porcelain, and the painter paints on it separately.

So there’s a porcelain maker, and then a painter.

‘Kiyomiz’ чего?

У фарфора Kiyomizu гончар и художник — разные.

Гончар создаёт фарфор, а художник рисует на нём по отдельности.

‘Kiyomiz’ what?

For Kiyomizu porcelain, its potter is different from its painter.

The potter makes the porcelain, and the painter paints on it separately.

Гончар создаёт фарфор, а художник рисует на нём по отдельности.

То есть сначала гончар, а потом художник.

— По отдельности.

The potter makes the porcelain, and the painter paints on it separately.

So there’s a porcelain maker, and then a painter.

— Separately.

Спортивное телосложение чёрного, буддистская концентрация!

«Крадущийся гончар!»

Потом он идёт на крупнейший турнир и он играет в городе Сент-Андрус, где блять и изобрели этот спорт!

Black athletic ability, Buddhist concentration.

Crouching Potter.

And then he goes to the British Open, and he plays at Saint Andrews, where they fucking invented the sport.

Куртизанка понимала, что ее сына будут считать угрозой для трона, и королева подослала евнуха, чтобы тотубил сына куртизанки.

Тогда был праздникДевали, и все гончары пришли ко дворцу с кувшинами.

Тогда куртизанка упросила одного из гончаров тайком вынести ее ребенка в пустом кувшине.

The courtesan knew that her son would be considered a threat to the throne, so… the eunuchs would be dispatched to kill her child. She was determined to save him.

It was Diwali, and the potters came to gift their vessels.

Suddenly, the courtesan had an idea. She… begged one of the potters to smuggle her baby out in an unused urn.

Слова, слова, слова…

Прежде у меня был дар… из слов ваять любовь, как тот гончар -горшки из глины …

Любовь, что потрясает основы империй, любовь, над которой не властен даже огонь преисподней… шесть пенсов за строчку,…

Words, words, words.

Once, I had the gift. I could make love out of words as a potter makes cups of clay.

Love that overthrows empires. Love that binds two hearts together, come hellfire and brimstone.

Тогда был праздникДевали, и все гончары пришли ко дворцу с кувшинами.

Тогда куртизанка упросила одного из гончаров тайком вынести ее ребенка в пустом кувшине.

И она больше никогда не видела своего сына?

It was Diwali, and the potters came to gift their vessels.

Suddenly, the courtesan had an idea. She… begged one of the potters to smuggle her baby out in an unused urn.

Did the courtesan see her son again?

Вверх.

Я гончар.

Я захватываю тебя, а ты бери меня за голову.

Go up.

I’m a mugger.

I’m gonna grab you, now grab the back of my head.

О, нет-нет, это одна из моих работ.

Я продаю их в паре магазинов, я гончар.

То есть, руками работать умеешь?

Oh, no, no, it is one of my pieces.

I sell them in a few stores, I’m a potter.

So you’re good with your hands?

Чем-то острым.

Как соус тартар в печи гончара.

Это твой запах лжи.

And tangy.

Like… tartar sauce in a potter‘s kiln.

That’s your lying stench.

Возможно, это была гончарная глина.

Гончары используют …

Проволокой пользуются, чтобы срезать глину с гончарного круга.

It may have been potter’s clay.

Potters use a…

Potters use a wire to cut their work from the wheel.

Какая ты зануда, Прислужник.

Именно такая глина и нужна гончару.

Я чую героя.

You’re such a pill, Minion.

A potter couldn’t ask for finer clay.

I smell a hero.

Пока другие дети играли в семью, мы занимались лепкой.

Ваш парень стал гончаром?

Он стал гончаром, но не моим парнем.

While the other children played house, we played pottery.

Did your boyfriend become a potter?

He did become a potter, but he didn’t become my boyfriend.

Но ничто не происходит так, как я того хочу.

Знаешь, почему ты, а не твой брат, стал гончаром?

Потому что ты похож на меня.

But things just don’t happen the way I wish them to.

Do you know why you became a potter setting all things aside?

It’s because you are like me.

Ваш парень стал гончаром?

Он стал гончаром, но не моим парнем.

Не нужно меня жалеть.

Did your boyfriend become a potter?

He did become a potter, but he didn’t become my boyfriend.

There’s no need to feel sorry for me.

Дурак что ли?

Я гончар.

Мое колесо сломалось.

Are you stupid?

I’m a potter.

My wheel broke.

Каково твоё ремесло?

Я гончар, о царь.

А ты, аркадиец, каково твоё ремесло?

What is your profession?

I’m a potter, sir.

And you, Arcadian. What is your profession?

Я думал, что в Библии можно найти женщин носящих горшки… в Библии много подобных слов.

Горшок гончара.

Да, древние понятия модернизируются, но когда речь идёт об авто, английский выигрывает.

That’s what I wondered. That you would find in the Bible, women carrying pots and all kinds of… You know, pots, and lots of words like that in the Bible.

Potters‘ vessel.

You’ll see modernisation of ancient terms. But usually when it comes to cars, the English wins.

Нет признаков злоупотребления наркотиками или алкоголем.

Он не курильщик, шахтёр или гончар—это саркоидоз.

Начните давать ему кортикостероиды и метотрексат. Если это лекарственно-устойчивый вирус, и мы дадим ему стероиды—

We’re gonna have to do a pneumon.

No sign of drug or alcohol abuse. He’s not a smoker, a coal miner, or a potter—it’s sarcoidosis.

Start him on corticosteroids and methotrexate.

Карен?

Ну, думаю, что пойду, наконец на курсы гончаров.

И… буду есть, что захочется, и ни о чем не заботиться.

Karen?

Okay, well, I think I’m finally gonna take that pottery class.

And… Well, I’m gonna eat whatever I want, and totally not even care. Just…

Профессионально играл… Был коневодом.

Работал гончаром.

Делал горшки какое-то время.

Professional gambler… horse breeder.

Potter.

I made pots for a while.

Или буду делать подсвечники.

♪ Может, я буду гончаром ♪

♪ Или учителем, как в Welcome Back, Kotter ♪

Or a candlestick maker.

♪ Maybe I’ll be a potter ♪

♪ Or a teacher like Welcome Back, Kotter ♪

Показать еще

Мастер-классах гончаров и рисовальщиц, кузнецов;

Master classes of potters and draftsmen, blacksmiths;

Творческих конкурсах гончаров и кузнецов;

Creative competitions of potters and smiths;

Дмитрий Гончаров Член Совета директоров Нет.

Dmitri Gontcharov Member of the Board of Directors No.

По этой причине его мелодии

часто называют« soleares alfareras» солеарес гончаров.

For this reason,

these styles are often called»soleares alfareras» potters‘ soleares.

Час- Открытие выставок и коллектив гончаров гостей- Парати Дом культуры.

H- Opening of exhibitions and collective of potters guests- Paraty House of Culture.

Gonchrov in his contemporaries’ memoirs.

Dawn, Our Correspondent.

Международный конгресс гончаров в Таллинне.

VEUKO(International Congress of Potters) in Tallinn.

В ее основе лежали современные инновационные подходы и

древние традиции гончаров Сардинии.

It was based on modern innovative approaches and

Общественность будет также иметь возможность участвовать в семинарах и

The public will also have the opportunity to participate in workshops and

Как художник- монументалист Гончаров участвовал в оформлении станций Московского метрополитена, павильонов ВДНХ

и советских павильонов на международных выставках.

As a muralist Goncharov participated in the design of the stations of the Moscow Metro,

pavilions ENEA and Soviet pavilions at international exhibitions.

Тогда куртизанка упросила одного из гончаров тайком вынести ее ребенка в пустом кувшине.

The courtesan had an idea. she begged one of the potters to smuggle her baby out in an unused urn.

Лючия Споялэ, Председатель Национального бюро статистики, Молдова-

Александр Гончаров, Главный эксперт, Росстат, Российская Федерация Введение в Обмен статистическими данными и метаданными( ОСДМ)- Страны.

Lucia Spoiala, Chairman, National Bureau of Statistics, Moldova-

Alexander Goncharov, Chief Expert, Rosstat, Russian Federation.

Такие прозаики, как Тургеньев, Гончаров, Толстой развили в своих произведениях тему философской самозабвенной любви,

созданной А. С. Пушкиным.

Such prose writers, as Turgenev, Goncharov, Tolstoy in their works developed the theme of philosophical selfless love,

which was created by Alexander Pushkin.

Г-н Гончаров в качестве судьи председательствовал при рассмотрении по первой инстанции целого ряда сложных уголовных дел, в том числе

дел, связанных с транснациональной преступностью.

Mr. Gontšarov presided as a first instance judge over numerous complicated criminal trials,

including transnational crimes.

Уникальное переплетение различных видов

искусств привлекло более тысячи скульпторов, гончаров, писателей, режиссеров,

композиторов, деятелей культуры со всех континентов.

The amalgamation of these art forms

has attracted more than a thousand sculptors, potters, writers, directors,

composers and other cultural workers from all continents.

От Berstett вы можете посетить многочисленные живописные деревни; Дорога вина,

деревни Гончаров: Soufflenheim и Betschdorf, линии Мажино.

From Berstett, you can visit numerous picturesque villages; the road of the wine,

the villages of potters: Soufflenheim and Betschdorf, the Maginot line.

Дмитрий Гончаров, подготовивший в соавторстве с Полом Скедсму(

Институт Фритьофа Нансена) доклад» Деполитизация российского гражданского общества?

Dmitry Goncharov, Professor at the Department of Political Science,

who presented the report‘Towards a Depolitization of Russian Civil Society?

Защитники Алексей Гончаров Геннадий Окинка Дмитрий Бербинский Ион

Арабаджи Анатолий Боештян Штефан Оанца 18 Эдуард Валуца.

Defenders Alexei Goncearov Ghenadie Ochinca Dumitru Berbinschi Ion

Arabadji Anatol Boestean Ştefan Oanţa 18.

В этом качестве г-н Гончаров отвечал за поддержку обвинения по уголовным делам различной степени сложности.

In this capacity Mr. Gontšarov was responsible for the prosecution of criminal cases of varying complexity.

Защитники Алексей Гончаров Дмитрий Кузнецов Сергей Литвинчук 2

Евгений Огородник Сергей Орлов 5 Николай Орловский Денис Палий Иван Харламов Леонид Шарф Жустиче Ампах Энор Браймах Андрей Бурковский.

Defenders Alexei Goncearov Dumitru Cuznetov Serghei Litvinciuc 2

Eugen Ogorodnic Sergiu Orlov 5 Denis Palii Ion Harlamov Leonid Sarf Justice Ampah Enor Braimah Andrei Burcovschi.

По линии этого проекта г-н Гончаров выступал несколько раз на различных международных конференциях см. ниже.

In the framework of this project, Mr. Gontšarov delivered several speeches during various international conferences see below.

Делегацию, в которую вошел Президент Российского союза туриндустрии Сергей Шпилько,

возглавил заместитель руководителя Росграницы Владимир Гончаров.

The delegation, where one of the members is Sergey Shpilko, president of the Russian Union of tourist industry,

is lead by the vice-leader of the Russian Border Vladimir Goncharov.

Просматриваются прерывистые цепочки улиц и кварталов ремесленников, в которых сохранились остатки глиняных печей и отвалы бракованной продукции стеклодувов,

There come into view the outlines of street network and artisan quarters with extant parts of the clay kilns and production dumps of glass-blowers,

Г-н Гончаров также провел ряд совещаний

и семинаров в Генеральной прокуратуре Казахстана и Верховном суде Казахстана, посвященных опыту Эстонии в использовании альтернативных форм в уголовном процессе.

Mr. Gontšarov also conducted several meetings

and workshops in the Prosecutor General’s Office of Kazakhstan and Supreme Court of Kazakhstan on Estonia’s experience in alternative forms in criminal procedure.

Депутатский корпус тесно сотрудничает с Министерством внутренних дел- об этом свидетельствуют принятые законы, регламентирующие деятельность правоохранительных органов »,-

The deputy corps works side by side with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as evidenced by the laws enacted to regulate the activities of law enforcement agencies,

Перевод для «гончаров» на английский

- Примеры

- Подобные фразы

Примеры перевода

-

potter

-

ceramist

(кузнецы, гончары, гриоты и т.д.)

(blacksmiths, potters, griots, etc.)

Они включают ремесленников по металлу (или «кузнецов»), гончаров, музыкантов/бардов (или «гриотов»), кожевников, ткачей, цирюльников/парикмахеров и других.

They include metalworkers (or «blacksmiths»), potters, musicians/bards (or «griots»), leatherworkers, weavers, barbers/hairdressers and others.

— оказания консультативной и финансовой поддержки гончарам и красильщицам в некоторых туристических районах (Дженне, Дуру и Энде).

— Assisting female potters and dyers at certain tourist sites by providing advice and financial support (Djenné, Dourou and Enndé).

Это дало мне возможность отождествить себя с сельским населением, гончарами, предпринимателями, коммерсантами и присоединиться к их усилиям, направленным на создание достойного будущего для себя самих и своих семей.

That enabled me to identify with rural people, potters, industrialists and tradespeople in their efforts to build a decent future for themselves and their families.

c) женщины-гончары, представляющие «Отраслевой совет женщин Санто-Доминго-де-Гусман», Санто-Доминго-де-Гусман, департамент Сонсонте;

(c) Santo Domingo de Guzmán, Sonsonate: Women potters of the «Women’s sectoral board of Santo Domingo de Guzmán»;

67. Брук Айеле описывает представителей фуга «в основном как гончаров, представляющих низшую касту ремесленников в группе камбата и других смежных этнических группах»17.

67. Bruk Ayele describes the Fuga as «mainly potters who are a lowcaste occupational group in Kambata and other neighbouring ethnic groups».

Кроме того, в бедных общинах, например в деревне гончаров и в районе «АюнХилван» в Каире, производятся принудительные выселения без предоставления альтернативного жилища или компенсации.

Furthermore, forced evictions without alternative housing or compensation being provided have been occurring in poor communities like the potters‘ village and the «Ayn Hilwan» area in Cairo.

Индейцы племени лукаян считались прекрасными землепашцами, искусными гончарами, ткачами хлопковых тканей, опытными ныряльщиками и умелыми мореплавателями, выходящими в море на выдолбленных из ствола дерева каноэ собственной конструкции.

The Lucayans were considered excellent farmers, good potters, weavers of cotton fibres, expert divers and skilled navigators in dugout canoes of their own invention.

Среди женщин также немало успешных художников и графиков, сценаристов и актеров, гончаров и певцов, и в 2001 году женщины-писатели получили большую часть премий на церемонии вручения премий Северной территории в области литературы.

Other successful practitioners include visual and graphic artists, playwrights and actors, potters and singers, while female writers won the majority of awards in the 2001 NT Literary Awards.

Твой отец гончар?

Your father is a potter?

Я гончар, о царь.

I’m a potter, sir.

Ваш парень стал гончаром?

Did your boyfriend become a potter?

Может, я буду гончаром

Maybe I’ll be a potter

Именно такая глина и нужна гончару.

A potter couldn’t ask for finer clay.

Как соус тартар в печи гончара.

Like… tartar sauce in a potter‘s kiln.

У фарфора Kiyomizu гончар и художник — разные.

For Kiyomizu porcelain, its potter is different from its painter.

Он стал гончаром, но не моим парнем.

He did become a potter, but he didn’t become my boyfriend.

Я продаю их в паре магазинов, я гончар.

I sell them in a few stores, I’m a potter.

Знаешь, почему ты, а не твой брат, стал гончаром?

Do you know why you became a potter setting all things aside?

На севере живут гончары.

There are potters in the north.

– А я Мондамей, гончар.

And I am Mondamay, the potter.

– Или фантастически искусный гончар.

Or a fantastically skillful potter.

Поэт, инженер, гончар?

Poet, engineer, potter?

заведения гончаров и сукновалов;

potters’ and fullers’ shops;

Возможно, у гончара были враги.

Perhaps the potter had enemies.

Стефани была не слишком искусным гончаром.

Stephanie was not an expert potter.

Гончар, человек набожный, перекрестился.

The potter, a pious man, crossed himself.

Жалкая внешность гончара была обманчива.

The potter‘s seedy appearance was deceiving;

– Осторожно, – предупредил гончар, – там крысы.

«Careful!» the potter warned. «There are rats down there.»

263. В программе профессиональной подготовки приняли участие в общей сложности 55 человек, из которых 48 были представителями РАЕ (из них 19 женщин, или 39,5%); они прошли обучение таким профессиям, как горничная, гигиенист, санитар, гончар и подсобный рабочий в садах и виноградниках.

263. Qualification programme included a total of 55 persons, of which 48 were members of RAE population (of whom 19 women or 39.5 per cent) who were trained in occupations of maid, hygienist, utility hygiene, ceramist and assistant worker in the orchards and vineyards.