Для человечества важно распространение и передача различной информации и знаний, поэтому знать, где и когда появилась бумага, интересно всем. Бумага представляет собой войлок, толщина которого около 0,2 мм, производят её из растительных волокон, мелко измельчённых.

Необходимая для современного человека бумага имеет интересную, почти детективную историю.

История возникновения бумаги

До создания бумаги люди пользовались в качестве носителей информации различным материалом:

-

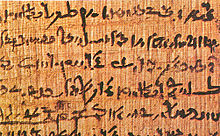

Папирус — применяли в Египте ещё за 4000 лет до нашей эры, использовали обработанные стебли гигантского травянистого многолетнего растения.

-

Пергамент — изготавливали ремесленники Малой Азии с помощью сложнейшей технологии с использованием телячьей кожи. Он отличался большей прочностью, эластичностью и долговечностью.

-

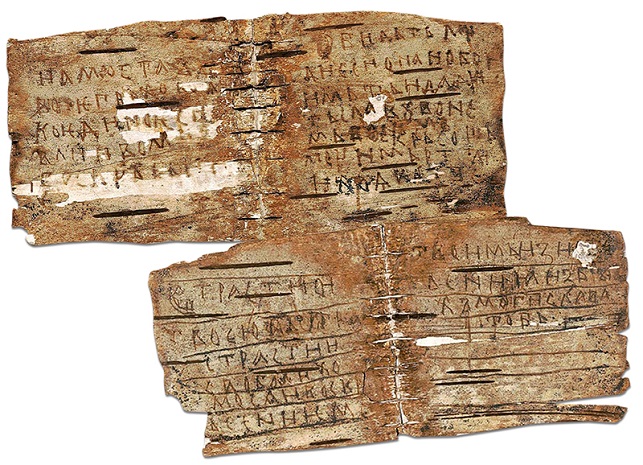

На Руси писали на бересте – берёзовой коре.

-

Древняя история мира содержит примеры письма на глиняных кирпичиках – плитках, деревянных табличках, покрытых воском, для написания на которых использовали палочки – «стили».

Все изобретения, связанные с носителями информации, сохранялись в тайне, так как приносили доход своим производителям. Но самым строжайшим секретом, который долго не был разгадан, было изобретение технологического процесса изготовления бумаги китайцами.

Первая бумага, появившаяся в Китае ещё до нашей эры, изготавливалась из шёлка, а уже позднее из растительных волокон.

610 год известен тем, что в Японию прибыл представитель странствующих буддийских монахов Дан-хо, который и раскрыл секрет получения бумаги и туши. Японские монахи не только переняли секреты производства так нужного для всех материала, но и добились его более высокого качества.

Созданная японскими изобретателями бумага «ваши» является самой прочной в мире. В этой же стране появилось и искусство создания бумажных фигурок — оригами, предназначенное не только для детей.

Затем именно в Японии в VIII веке вслед за бумажными мастерскими появились первые фабрики.

Индийские производители изобрели способ производства бумаги из старого тряпья, которое после смачивания растиралось при помощи мельничных жерновов.

История возникновения бумажного производства содержит многочисленные интересные факты:

-

в восьмом веке арабы, победившие китайцев в сражении, переняли у пленных мастеров секреты состава бумаги;

-

испанские первооткрыватели способствовали распространению бумаги по многим странам мира;

-

персидским путешественником Насир Хосровом в 11 веке было замечено как используют обёрточную бумагу на базаре;

-

к концу 12 века началось появление бумажных мастерских в европейских странах;

-

изготовление бумажной продукции из дерева началось в 19 веке.

Изобретение технологии изготовления бумаги в Китае

Данный материал изобрели в Китае, что подтверждают обрывки бумаги, найденные в гробнице из пещеры Баоцян провинции Шэньси на севере страны. Дата производства этих обрывков относится к 11 веку до нашей эры.

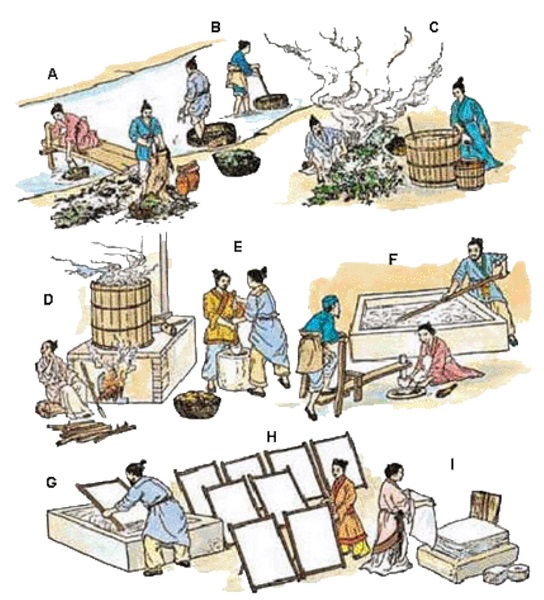

Процесс изготовления проходил следующим образом:

-

После замачивания в воде кору тутового дерева делили: внешний грубый слой шёл на изготовление бумаги низшего класса, из мягкого внутреннего изготавливали тонкую и дорогую.

-

Разделённые волокна варили в чанах, куда добавляли золу или известковое молочко.

-

Сваренную массу промывали, обрабатывали молотками.

-

Размельчённую массу проклеивали растительными соками, разбавленными водой, иногда заменяли сок на крахмальный клейстер.

-

Специальной формой отливали листы.

-

Немного подсушенный лист досушивали на солнце.

Придумал усовершенствованный рецепт производства этого ценного материала Цай Лунь, сановник из Китая – родины бумаги.

До этого момента, а доклад Цай Луня императору был представлен в 105 году, на производство бумаги требовалось много труда и затрат. Обобщив и усовершенствовав известные ранее технологии получения бумаги, он объяснил принцип, образующий листовой материал из отдельных волокон растений.

Цай Лунем было предложено соединить волокна шелковицы с пенькой, тряпками и древесной золой, которые толклись, смешивались с водой и выкладывались на форму для сушки, а так же разглаживались с использованием камней. С применением новой технологии бумажные листы получались более прочные, белоснежный цвет бумаги позволял использовать их для письма.

Будучи незнатного происхождения, Цай Лунь за изобретательность и трудолюбие был поощрён княжеским титулом. Начинал он службу при дворе императора простым евнухом.

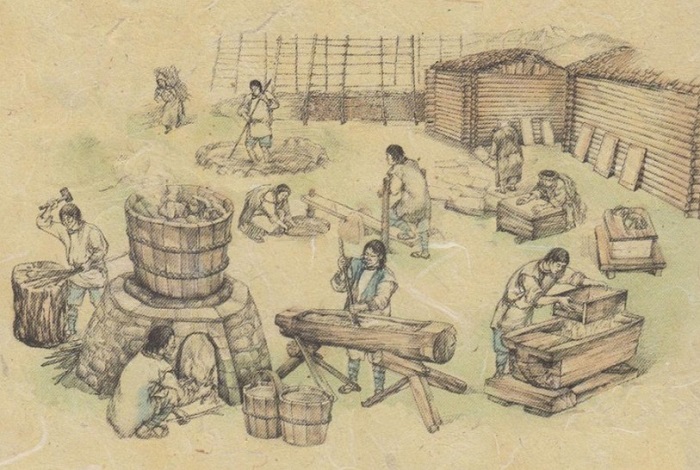

Производство бумаги в России

Собственное российское производство бумаги появилось во времена царя Ивана Грозного. Попытки изготовления этого ценного материала проводились в подмосковном селе Ивантеевка. Планы Ивана Грозного по импортозамещению дорогостоящей бумаги столкнулись с интересами Тевтонского ордена и даже были одной из причин начала Ливонской войны.

Следующим этапом получения собственной российской бумаги было распоряжение патриарха Никона о возведении бумажных мельниц в 17 веке. Начинания патриарха, столкнувшись с финансовыми проблемами, постепенно сошли на нет.

Во времена правления Петра I возросла необходимость в большом количестве бумаги. По указу императора строились бумажные предприятия по европейскому образцу. Был так же издан указ о сборе сырья в виде изношенных полотен и тряпок и запрет в применении заграничной бумаги.

Во времена второй половины 18 века бумаги стало импортироваться в два раза меньше. При императоре Александре I было разрешено открытие частных типографий и рост бумажной продукции увеличился. Тяжёлый труд рабочих на бумажных фабриках и отсталые технологии тормозили увеличение роста продукции. Уже в начале 19 века произошло усовершенствование бумагоделательных машин.

Появились различные сорта бумаги, которые назывались:

-

печатный;

-

рисовальный;

-

сорт писчей бумаги;

-

чертёжный сорт;

-

цветной;

-

упаковочный;

-

обойный;

-

патронный;

-

картон.

Производство зарубежной бумаги превышало производство российской продукции, но уже в 19 веке бумага из России экспортировалась в азиатские страны, в том числе и в Китай.

Реконструкции на целлюлозно-бумажных комбинатах проводились в середине 20 столетия. На современных бумажных комбинатах страны используется высокопроизводительное оборудование.

Из чего делают бумагу в наше время

Изготовлением бумаги занимаются предприятия промышленности, которая так и называется – целлюлозно-бумажная. Эти слова означают, что бумага изготавливается из целлюлозы, то есть из древесины.

Вся бумажная промышленность в мире использует это сырьё, так как прежнего сырья, состоящего из различных тканей, не хватает.

Много веков человечество использует бумагу самыми разнообразными способами. Без неё ни обойтись не только в типографиях, но и во многих других видах жизнедеятельности людей. Это, наверное, самый многофункциональный материал в мире.

В таком виде, как мы ее привыкли видеть, бумага появилась далеко не сразу. Отсчитывать историю возникновения бумаги, скорее всего, можно с изготовления папируса. Папирус начали изготавливать в Древнем Египте около 3,5 тысяч лет назад.

Технология изготовления папируса была очень непростой: из нижней части стебля извлекали сердцевину, потом ее разрезали ножом на тонкие полоски. Приготовленные таким образом полоски 2-3 дня набухали в свежей воде, после чего подвергались прокатыванию деревянной скалкой, затем процедуру повторяли еще несколько раз, пока полоски не становились полупрозрачными. После чего их укладывали друг на друга, обезвоживали и сушили под прессом. Далее следовал процесс разглаживания почти готового папируса камнем.

Из-за достаточно сложной технологии изготовления, папирус был дорогим материалом. Несмотря на это, папирус в качестве материала для письма, использовали еще несколько веков.

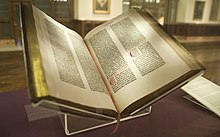

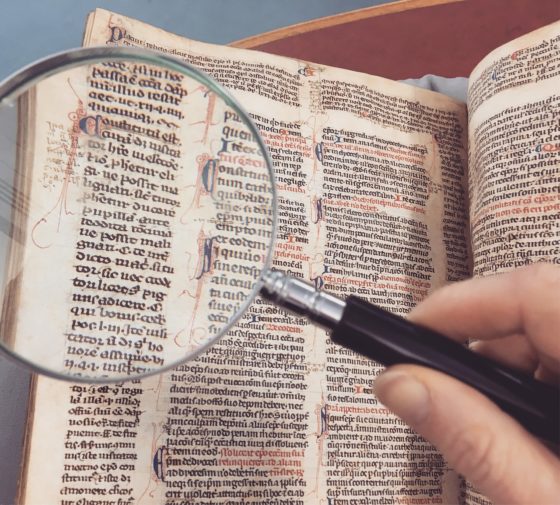

Другим материалом, используемым для письма, был изобретенный во II-м веке пергамент, названный в честь города Пергама, где его начали производить. Изготовление пергамента было сложным процессом, а материалом для его изготовления служили кожи молодых домашних животных. Стоил пергамент невероятно дорого.

Но все это были предшественники настоящей бумаги, изобретенной в Китае в 105 году нашей эры. Эту дату принято считать датой изобретения бумаги.

Китаец Цай Лунь предложил технологию производства бумаги из отдельных волокон путём их обезвоживания на сетке. Бумагу изготавливали практически из любого растительного сырья, придавали нужный размер и толщину, а для более длительного хранения пропитывали специальными веществами.

От китайцев технологию производства бумаги переняли арабы, победившие китайцев в сражении 751 года. Однако нельзя не признать большого вклада арабов в усовершенствование технологии производства бумаги и в улучшении ее качества.

В Европе история развития бумаги заняла еще больше времени. Впервые бумагу в Европе начали выпускать в Испании, и достигли в этом процесс большого совершенства. Бумага, произведенная в Испании, была столь превосходного качества, что ее охотно приобретали во многих странах.

Дальнейшая история развития бумаги и бумажного производства развивалась преимущественно в Европе. В 1154 году бумага появилась в Италии, потом в Венгрии, Англии, в 1565 году — в России, затем в Голландии и Швеции.

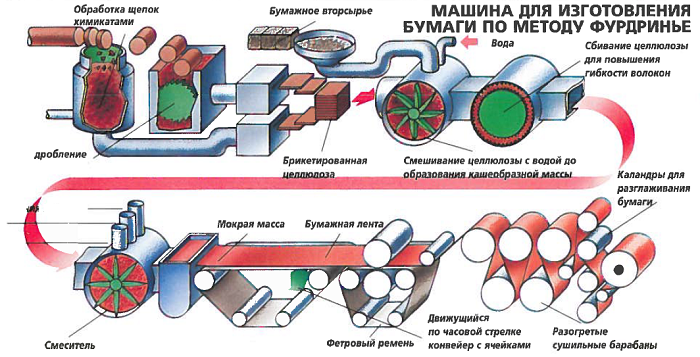

Изобретение печатного станка оказало огромное влияние на развитие и совершенствование технологий производства бумаги. Во второй половине XVII века был изобретен размалывающий аппарат. Он назывался ролл. Применение размалывающих аппаратов способствовало значительному увеличению объемов производства бумаги. В 1799 году в истории изобретения бумаги произошло другое важное событие. Француз Робер разработал технологию, в которой впервые процесс отлива бумаги был механизирован при помощи непрерывно движущейся сетки.

История бумаги в России.

В Древней Руси для письма использовали бересту — внешнюю часть березовой коры. Бумага собственного производства появилась во времена царствования Ивана Грозного — во второй половине XVI века.

Массовое бумажное производство бумаги в России началось по приказу Петра I. В 1721 году был издан указ, согласно которому в официальном делопроизводстве разрешалось использовать только отечественную бумагу. Для производства бумаги использовали всякое ненужное тряпье, веревки.

Производство бумаги продолжало совершенствоваться и в последствии. В настоящее время это высокопроизводительный, полностью автоматизированный процесс.

Возникновение бумаги

Происхождение бумаги было обусловлено появлением письменности – ведь помимо изобретения алфавита и грамматики, необходимо было на чем-то писать. Впрочем, в том виде, в котором мы привыкли, бумага появилась не сразу. Пожалуй, что можно сказать, что история возникновения бумаги началась с того, что в древнем Египте около 3,5 тысяч лет назад начали изготавливать папирус.

Основным материалом для изготовления папируса были трехгранные стебли тростника, достигавшие 5-ти метровой высоты. Впрочем, для приготовления папируса применяли только нижнюю часть стебля длиной около 60 сантиметров. Ее освобождали от наружного зеленого слоя, а сердцевину белого цвета извлекали и разрезали на тонкие полоски ножом. После этого полученные полоски 2-3 дня выдерживали в свежей воде для набухания и удаления растворимых веществ. Далее размягченные полоски прокатывали деревянной скалкой по доске и помещали в воду на сутки, опять прокатывали и снова клали в воду. В результате этих операций полоски приобретали кремовый оттенок и становились полупрозрачными. Далее полоски укладывали друг на друга, обезвоживали под прессом, сушили и разглаживали камнем.

Как видно, технология первой бумаги была достаточно сложной, а потому папирусы были дороги. Кроме того, они были не очень долговечны и требовали бережного отношения к себе.

Несмотря на это, вплоть до V-го века папирус оставался основным материалом для письма, и лишь в X веке от него практически полностью отказались.

Параллельно с развитием папируса началось развитие другого материала, который оказал большое влияние на историю бумаги. Этим материалом стал придуманный во II-м веке до нашей эры в Малой Азии пергамент. Свое название он получил из-за места, где началось его производство – города Пергама Пергамского царства. Любопытно, что появление пергамента во многом обусловлено тем, что Египет, опасаясь соперничества Пергамской библиотеки, для защиты статуса Александрийской библиотеки, как крупнейшей, организовал то, что впоследствии будут называть торговым эмбарго – запретил вывоз папируса за пределы Египта.

Пергамент получали путем особой, весьма сложной обработки кож молодых животных – телят, ягнят, козлов и ослов. В отличие от папируса, пергамент был значительно прочнее, эластичнее, долговечнее и на нем можно было писать с обеих сторон.

Однако у него был большой и очень серьезный недостаток – изготовление пергамента было очень трудным процессом, а потому этот материал был чудовищно дорог. Настолько дорог, что для того, чтобы написать новые документы, иногда приходилось смывать чернила со старых пергаментов.

Кстати, такие многоразовые пергаменты называются палимпсестами, иногда ученым удается восстановить то, что на них было изначально написано. Так в 1926 году стал широко известен Лейденский палимпсест, на котором сначала были нанесены тексты Софокла, а потом смыты и заменены на религиозный текст.

Однако настоящим началом истории бумаги принято считать 105 год нашей эры, а родиной – Китай. Хотя это и не совсем верно, ведь появление бумаги в Китае произошло гораздо раньше.

Тем не менее, именно Цай Лунь обобщил и усовершенствовал уже известные способы изготовления бумаги и предложил технологический принцип производства бумаги – образование листового материала из отдельных волокон путём их обезвоживания на сетке из предварительно сильно разбавленной волокнистой суспензии. Происхождение бумаги во многом было обусловлено тем, что для ее производства годились практически любое растительное сырье и отходы: лубяные волокна тутового дерева и ивы, побеги бамбука, солому, траву, мох, водоросли, всякое тряпьё, конопляные очёсы, паклю.

На рубеже II и III веков новой эры бумага, изготовленная из растительных волокон, уже не считалась в Китае редким материалом. Дальнейшим шагом в истории развитии бумаги стало ее полное вытеснение из употребления деревянных дощечек в III веке, которые ранее использовались для письма. Бумагу изготавливали нужного размера, цвета, толщины и пропитывали специальными веществами для более длительного хранения.

Другой по-настоящему большой вехой в истории развития бумаги стало появление «летающих монет» в IX веке все в том же Китае – бумажных денег. Следует отметить, что в Европе это произошло намного позже.

Кстати, именно Китай стал местом происхождения туалетной бумаги. В Европе это новшество прижилось значительно позже.В течение многих веков китайцы были единственными, кто владел секретами изготовления бумаги, а потому они ревностно оберегали эту технологию.

Однако в 751 году произошло сражение, в котором арабы победили китайцев, и смогли пленить нескольких бумажных мастеров. От них арабы смогли перенять опыт по производству бумаги и потом усовершенствовали его, что оказало большое влияние на историю бумаги.

Первым некитайским центром развития бумажного производства стал Самарканд, далее в 800 году бумагу появляется в Багдаде, в 1100 – в Каире,а в 1300 – в Венеции. Почти 300 лет потребовалось для того, чтобы бумага из Ирака смогла попасть в Египет.

История появления бумаги в Европе была еще длиннее. Первые бумажные мельницы появились в Испании в X веке, а уже через 100 лет в Толедо и Шативе вырабатывали бумагу столь высокого качества, что ее охотно покупали во многих странах. В начале XII века произведения некоторых итальянских поэтов были уже написаны на превосходной белой бумаге.

Дальнейшая история развития бумаги и бумажного производства развивалась преимущественно в Европе. Вскоре, большую конкуренцию итальянцам стали составлять французы. Из Франции бумажное производство двинулось в Англию, Голландию и на восток – в Германию, Польшу, Московскую Русь.

Несомненно, огромное влияние на историю развития бумаги оказало изобретение печатного станка. В XV-XVI веках темпы производства бумаги растут, и внедряются новые технологии ее производства.

История развития бумаги шла, и во второй половине XVII века был придуман ролл – размалывающий аппарат. Трудно представить себе более значимую веху в истории изобретения бумаги, ведь применение таких аппаратов позволило сильно увеличить объемы производства.

В конце XVIII века при помощи роллов уже производили гораздо большие объемы бумажной массы, однако отлив вручную бумаги сильно тормозил производственный рост. Поэтому в 1799 произошло другое важное в истории изобретения бумаги событие – француз Н. Л. Робер придумал машину для изготовления бумаги, механизировав отлив бумаги при помощи использования непрерывно движущейся сетки.

История развития бумаги и бумажного производства продолжалась, и в 1806 братья Г. и С.Фурдринье, которые приобрели патенты Робера и продолжили работать над машиной по отливу в Англии, запатентовали свою машину по производству бумаги.

К середине XIX века это машина, претерпев ряд изменений, превратилась в достаточно сложный агрегат, который работа непрерывно и по большей степени автоматически.

В XX веке производство бумаги – это уже крупная высокомеханизированная промышленная отрасль с непрерывно-поточной схемой в технологии производства, большими по мощности теплоэлектрическими станциями и достаточно сложными химическими цехами по изготовлению полуфабрикатов из волокон.

Современные технологии сильно изменили мир. По мере распространения телевидения, компьютеров и интернета регулярно предрекается смерть книг, журналов и газет. Однако, несмотря на прогнозы, и книги, и журналы, и газеты все еще живы, а это значит, что история бумаги продолжается! Более того, современное применение бумаги настолько разнообразно, что можно уверенно утверждать, – эта история закончится не скоро.

Источник -pultus ucoz ru/publ/ehto_interesno/proiskhozhdenie_veshhej/vozniknovenie_bumagi/15-1-0-105

В наши дни бумагу изготавливают во всем мире. Ежедневно мы используем ее, когда читаем газеты, журналы и книги, дети обучаются в школе по учебникам из бумаги, пишут в тетрадях, выполненных из этого же материала.

Список можно продолжать бесконечно, но кому же мы обязаны ее появлением? Кто и когда придумал бумагу?

Когда была изобретена бумага?

По общепринятой версии, бумага была изобретена в 105 году нашей эры. Однако сам материал для письма возник задолго до этого. Одной из самых ранних письменных принадлежностей в истории человечества был папирус, который жители Древнего Египта изготавливали из растения семейства осоковых.

Сегодня в музеях, посвященных египтологии, можно увидеть старинные иконографии с изображением папируса, датируемые III тысячелетием до нашей эры. Впоследствии для письма использовали шелковые ткани, производимые из бракованных коконов шелкопряда, а затем – пеньку, которую делали из конопляных волокон.

В 105 году произошел настоящий прорыв в бумажной индустрии, благодаря которому весь мир получил возможность писать на бумаге.

Кто изобрел бумагу?

Создателем бумаги стал китайский евнух Цай Лунь, служивший при императоре из династии Хань. Будущий изобретатель родился в городе Гуйян (ныне – Лэйян), в 75 году поступил в императорский дворец, а в 89 году получил должность в учреждении, которое занималось перезарядкой оружия.

К тому времени документы в Китае писались на бамбуке или костях животных. Они имели большой вес и были неудобными для перевозки, поэтому в стране появилась необходимость придумать что-нибудь более легкое. Правда, был еще шелк, но стоил он дорого и по определению не мог получить широкое распространение. По этой причине изобретение Цай Луня пришлось весьма кстати.

Существует легенда, что вдохновение для создания бумаги евнух обрел во время наблюдения за бумажными осами. Эти насекомые способны самостоятельно делать материал, похожий на бумагу, путем пережевывания древесных волокон и смачивания их своей клейкой слюной.

Историки не исключают, что на самом деле бумагу изобрел кто-то из более низких слоев общества, а Цай Лунь лишь присвоил себе результаты его труда. Как бы там ни было, но в 105 году евнух представил свое изобретение императору Хэ-ди, за что получил наивысшую похвалу.

Как была изобретена бумага?

В соответствии с китайскими летописями, чтобы получить бумагу, Цай Лунь использовал в своей работе древесную золу, пеньку, волокна тутового дерева и старье тряпье. Все ингредиенты он тщательно измельчил и перемешал с водой.

Дополнительно изобретатель создал специальное приспособление в виде деревянной рамки с бамбуковым ситом внутри, на которое выложил полученную смесь и выставил для просушки на солнце. Затем высушенный материал был разглажен камнями. В итоге получились тонкие, плотные листы, на которых было удобно делать записи.

С течением времени процесс был запущен в массовое производство. Бумагу изготавливали на водяных мельницах, но перед просушкой на солнце клали под пресс и подвергали сильному сжатию. В некоторых случаях в чаны с бумажным сырьем добавляли клей, благодаря чему при письме на таких листах чернила не растекались.

Древняя бумага была не совсем качественной и включала в себя цельные древесные волокна и даже кусочки тряпок, однако со временем китайская технология изготовления была усовершенствована и получила признание во всем мире.

Когда бумага попала в другие страны?

Распространение бумаги за пределы Китая продвигалось достаточно сложно. Долгое время техника ее изготовления держалась в секрете, но к VII столетию первые бумажные листы появились в Японии и Корее, а в IX веке – в арабских странах.

Европейцы смогли воспользоваться настоящей бумагой только в XI–XII столетиях. В эпоху Ренессанса в моду вошли бумажные обои, а к XV веку, в связи с появлением книгопечатания, в большинстве европейских государств уже существовали многочисленные бумажные фабрики.

( 38 оценок, среднее 4.29 из 5 )

В европейских языках понятие «бумага» связано с корнем слова папирус — растения, из которого в прошлом изготавливался бумагоподобный материал, используемый древними египтянами, греками, римлянами. Например, бумага по-английски — the paper, по-немецки — das papier, по-французски — le papier.

Датой рождения бумаги считается 105 г н.э., когда советник китайского императора Цай Лунь обобщил и усовершенствовал уже имеющиеся способы изготовления бумагоподобных материалов. Ранее в Китае в качестве материалов для письма в основном использовали бамбук, пеньку, шелк.

Цай Луню после многих опытов удалось впервые открыть основной технологический принцип создания бумаги: формирование листового материала осаждением и переплетением на сетке измельченных тонких волокон, разбавленных ранее водой. Он также усовершенствовал процесс изготовления бумаги, когда заменил плоские камни ступкой с пестом, а также применил для отлива листа сетчатую форму. Получать бумагу стало возможным из различных видов волокнистого сырья. Эти новшества положили начало производству бумаги – более доступной и дешевой в сравнении с предыдущими материалами для письма.

Позднее процесс изготовления бумаги усовершенствовали: для повышения прочности начали добавлять клей, крахмал и естественные красители.

В III веке н.э. бумага из растительных волокон уже не являлась в Китае редким материалом и почти полностью вытеснила из употребления деревянные дощечки, которые ранее применялись для письма. Бумагу производили необходимого размера, цвета, а также пропитывали специальными веществами для увеличения срока хранения.

В бумажную массу стали добавлять побеги бамбука, либо тростник. В IV веке уже существовало несколько сортов бумаги. Технология производства усложнилась. Сначала сырье долго промывали и вымачивали. Затем варили с добавлением извести и золы. После этого сырье тщательно измельчали деревянными билами в больших ручных ступах. Получившаяся кашицеобразная бумажная масса разводилась водой, размешивалась и выливалась на сетку из проволоки или бамбуковых волокон. Для получения гладкой бумаги на сетке равномерно распределяли бумажную массу. Готовые листы перед просушиванием отжимали между кусками сукна.

В течение столетий только китайцы владели секретами производства бумаги, потому и хранили данную технологию в тайне. Бумагу продавали за большие деньги, обменивали на дорогие ткани и металл. В Китае в IX веке появились первые бумажные деньги фэй-тянь, которые прозвали «летающими монетами». Также китайцами была изобретена и туалетная бумага. Научились изготавливать бумагу также из специально обработанных ветхих тряпок. На рубеже X-XI веков китайцы из уплотненной бумаги начали изготавливать игральные карты. Со временем китайская бумага проникла и в другие страны.

В 610 году странствующий буддийский монах Дан-хо приехал в Японию и передал секрет производства бумаги и туши. Японским мастерам со временем удалось создать бумагу более высокого качества. Японскую бумагу называли ВАСИ: ВА – иное чтение иероглифа Ямато, обозначающего Японию, а СИ – это бумага. Китайская бумага в Японии получила название КАРА-ГАМИ. Мастера в Японии не отцеживали волокнистую пульпу через неподвижное сито, как делалось китайцами, а непрерывно покачивали его, заставляя бумажную массу оседать равномернее. Вторым нововведением стало применение сока водного растения ТОРО-АОИ в качестве отличного средства для проклеивания бумажного листа. В VIII веке растущие потребности императорского двора, монастырей и храмов привели к буму производства бумаги и появлению множества больших и малых мастерских, которые выпускали 180 видов бумаги. В Японии возникло Оригами — искусство складывания из бумаги прекрасных фигурок. В VII веке секрет производства бумаги стал известен и в Корее.

В Индии нашли способ создания бумаги из тряпок, парусины, сетей и канатов. Данное сырье смачивали водой, а потом растирали между мельничными жерновами.

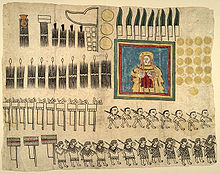

В 751 году арабы одержали победу над китайцами в Таласской битве, а также захватили в плен несколько китайских бумажных мастеров, от которых переняли технологию производства бумаги. Благодаря этому Самарканд стал крупным центром бумажного производства. Около 800 года арабский халиф Гарун аль-Рашид с помощью китайских мастеров организовал производство бумаги в Багдаде. Позднее в Дамаске и Каире также появились мастерские по изготовлению бумаги. К XI веку Арабский мир и Индия активно использовали в различных сферах бумагу, которая постепенно вытеснила папирус и пергамент. Из-за недостатка лубяного сырья арабы использовали при производстве бумаги хлопок. В IX веке собственную бумагу создали майя в Америке.

В IX-XI веках бумага начинает проникать в Европу через Испанию, Византию и Италию. Первоначально ее покупали у арабов. В X веке в Испании появляются первые бумажные мельницы, которые через столетие выпускают бумагу довольно высокого качества. В XII веке собственные бумажные мастера появляются в Италии и Франции. В XIII-XV веках производство бумаги освоили в других странах Европы: Венгрии, Германии, Англии, Польше и пр. Более грубая европейская бумага оказалась белее восточной, а также склеивалась животным клеем. В Европе в качестве сырья для изготовления бумаги использовали дерево, кору, солому, размолотые тряпки и т. п. Применение толчеи улучшило качество бумажной массы. Для разравнивания бумажной массы начали также использовать клиновые прессы. Итальянцы изобрели водяные знаки. В XIV веке улучшился контроль над качеством бумажной массы, процессами лощения и проклейки. Началось производство игральных карт, появились рекламные плакаты.

В различных странах для производства бумаги часто использовались мельницы. Водяное колесо приводило в движение вал, механическая энергия которого расходовалась на измельчение сырья для бумажной массы. К металлическому сетчатому черпаку прикреплялся проволокой какой-нибудь знак, который затем проявлялся на бумажной массе после высыхания.

Изобретение в XV веке книгопечатания способствовало значительному росту производства бумаги.

До XVI века в Московскую Русь бумаги завозили в основном из европейских стран. При царе Иване Грозном в середине XVI века наладили собственное производство.

В Голландии в 1670 году был изобретен ролл (голлендер), предназначенный для размола бумажной массы. Данный аппарат оказался в три раза более производительным, чем ранее применявшаяся толчея, а также повысил качество бумаги.

В 1770 году английский фабрикант Дж. Ватман предложил новую бумажную форму, обеспечивающую листы бумаги без следов сетки.

Сохранявшийся до конца XVIII века ручной отлив (вычерпывание) бумаги в значительной мере тормозил производственный рост. Только в 1799 году француз Н. Л. Робер изобрел бумагоделательную машину с механизированным отливом бумаги с помощью непрерывно движущейся сетки. Производительность новой машины достигала 100 килограммов в сутки.

С начала XIX века начинается машинный этап развития производства бумаги. В 1804 г. первую бумагоделательную машину, которую усовершенствовали братьями Фурдринье и Донкиным, установили в Англии.

Первые бумагоделательные машины производили только формование бумажного полотна, а также его прессование, но сушилась бумага все еще на воздухе. В 1823 г. к бумагоделательной машине присоединили сушильную часть. В ее сушильных цилиндрах с целью обогрева их поверхности установили жаровни с углем. Позднее удалось осуществить обогрев цилиндров паром. В 1825 г. под сеткой были установлены отсасывающие ящики, разрежение в которых осуществлялось при помощи вакуум-насоса. В последующие десятилетия многие детали конструкции бумагоделательных машин были в значительной степени усовершенствованы. Благодаря этому уже к середине XIX века бумагоделательные машины превратились сложные агрегаты, которые работали непрерывно и автоматически. От выпуска листовой бумаги теперь можно было перейти к ее производству в рулонах.

В 1846 г. саксонский инженер Фельтер изобрел дефибрер — аппарат для получения механической древесной массы. В 1850-х гг. англичанами и французами были открыты натронный и сульфитный методы варки целлюлозы. С середины XIX века в качестве сырья для производства бумаги в основном используется механическая древесная масса, а также химическая древесная целлюлоза хвойных пород.

В XX веке производство бумаги стало крупной высокомеханизированной отраслью промышленности с непрерывной поточной схемой в технологии производства, мощными теплоэлектрическими станциями и сложными химическими цехами по выпуску полуфабрикатов из волокон.

Бумагоделательные машины, созданные с учетом последних достижений научно-технического прогресса, представляют собой образцы высокопроизводительных аппаратов. На большинстве новых машин осуществляется двухсеточное формование, установлены автоматические системы управления технологическим процессом, которые обеспечивают эффективную работу машины на высоких скоростях.

В последние десятилетия в бумажной промышленности ведущую роль все больше занимают огромные корпорации и трансконтинентальные промышленные группы. Разрабатываются новые специализированные сорта бумаги. Проводятся исследования направленные на создание новых технологий, позволяющих уменьшить объемы промышленных выбросов.

.jpg)

Paper is a thin nonwoven material traditionally made from a combination of milled plant and textile fibres. The first paper-like plant-based writing sheet was papyrus in Egypt (4th Century BC), but the first true paper, the first true papermaking process was documented in China during the Eastern Han period (25–220 AD), traditionally attributed to the court official Cai Lun. This plant-puree conglomerate produced by pulp mills and paper mills was used for writing, drawing, and money. During the 8th century, Chinese paper making spread to the Islamic world, replacing papyrus. By the 11th century, papermaking was brought to Europe, where it replaced animal-skin-based parchment and wood panels. By the 13th century, papermaking was refined with paper mills using waterwheels in Spain. Later improvements to the papermaking process came in 19th century Europe with the invention of wood-based papers.

Although there were precursors such as papyrus in the Mediterranean world and amate in the pre-Columbian Americas, these are not considered true paper.[2] Nor is true parchment considered paper:[a] used principally for writing, parchment is heavily prepared animal skin that predates paper and possibly papyrus. In the 20th century with the advent of plastic manufacture, some plastic «paper» was introduced, as well as paper-plastic laminates, paper-metal laminates, and papers infused or coated with different substances to produce special properties.

Precursors[edit]

In contrast to paper, papyrus has an uneven surface that visibly retains the original structure of the ribbon-like strips that make it up. As the papyrus is worked, it tends to break apart along the seams, leading to long linear cracks and eventually falling apart.[2]

Papyrus[edit]

The word «paper» is etymologically derived from papyrus, Ancient Greek for the Cyperus papyrus plant. Papyrus is a thick, paper-like material produced from the pith of the Cyperus papyrus plant which was used in ancient Egypt and other Mediterranean societies for writing long before paper was used in China.[3]

Papyrus is prepared by cutting off thin ribbon-like strips of the interior of the Cyperus papyrus, and then laying out the strips side-by-side to make a sheet. A second layer is then placed on top, with the strips running perpendicular to the first. The two layers are then pounded together into a sheet. The result is very strong, but has an uneven surface, especially at the edges of the strips. When used in scrolls, repeated rolling and unrolling causes the strips to come apart again, typically along vertical lines. This effect can be seen in many ancient papyrus documents.[4]

Paper contrasts with papyrus in that the plant material is broken down through maceration or disintegration before the paper is pressed. This produces a much more even surface, and no natural weak direction in the material which falls apart over time.[4]

Papyrus was used in Egypt as early as the third millennium before Christ, and was made from the inner bark of the papyrus plant (Cyperus papyrus). The bark was split into pieces which were placed crosswise in several layers with an adhesive between them, and then pressed and dried into a thin sheet which was polished for writing.» Scholars of both East and West have sometimes taken it for granted that paper and papyrus were of the same nature; they have confused them as identical, and so have questioned the Chinese origin of papermaking. This confusion resulted partly from the derivation of the word paper, papier, or papel from papyrus and partly from ignorance about the nature of paper itself. Papyrus is made by lamination of natural plants, while paper is manufactured from fibres whose properties have been changed by maceration or disintegration.[5]

— Tsien Tsuen-hsuin

Paper in China[edit]

Earliest known extant paper fragment unearthed at Fangmatan, circa 179 BCE

Oldest paper book, Pi Yu Jing, composed of six different materials, circa 256 CE

The world’s earliest known printed book (using woodblock printing), the Diamond Sutra of 868, shows the widespread availability and practicality of paper in China.

Archaeological evidence of papermaking predates the traditional attribution given to Cai Lun,[6] an imperial eunuch official of the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), thus the exact date or inventor of paper cannot be deduced. The earliest extant paper fragment was unearthed at Fangmatan in Gansu province, and was likely part of a map, dated to 179–141 BCE.[7] Fragments of paper have also been found at Dunhuang dated to 65 BCE and at Yumen pass, dated to 8 BCE.[8]

The invention traditionally attributed to Cai Lun, recorded hundreds of years after it took place, is dated to 105 CE. The innovation is a type of paper made of mulberry and other bast fibres along with fishing nets, old rags, and hemp waste which reduced the cost of paper production, which prior to this, and later, in the West, depended solely on rags.[8][9][2]

Techniques[edit]

During the Shang (1600–1050 BCE) and Zhou (1050–256 BCE) dynasties of ancient China, documents were ordinarily written on bone or bamboo (on tablets or on bamboo strips sewn and rolled together into scrolls), making them very heavy, awkward to use, and hard to transport. The light material of silk was sometimes used as a recording medium, but was normally too expensive to consider. The Han dynasty Chinese court official Cai Lun (c. 50–121 CE) is credited as the inventor of a method of papermaking (inspired by wasps and bees) using rags and other plant fibers in 105 CE.[2] However, the discovery of specimens bearing written Chinese characters in 2006 at Fangmatan in north-east China’s Gansu Province suggests that paper was in use by the ancient Chinese military more than 100 years before Cai, in 8 BCE, and possibly much earlier as the map fragment found at the Fangmatan tomb site dates from the early 2nd century BCE.[7] It therefore would appear that «Cai Lun’s contribution was to improve this skill systematically and scientifically, fix a recipe for papermaking».[10]

Cai Lun’s biography in the Twenty-Four Histories says:[11]

- In ancient times writings and inscriptions were generally made on tablets of bamboo or on pieces of silk called chih. But silk being costly and bamboos heavy they were not convenient to use. Tshai Lun then initiated the idea of making paper from the bark of trees, remnants of hemp, rags of cloth and fishing nets. He submitted the process to the emperor in the first year of Yuan-Hsing (105 CE) and received praise for his ability. From this time, paper has been in use everywhere and is universally called the paper of Marquis Tshai.

The production process may have originated from the practice of pounding and stirring rags in water, after which the matted fibres were collected on a mat. The bark of paper mulberry was particularly valued and high quality paper was developed in the late Han period using the bark of tán (檀; sandalwood). Although bark paper emerged during the Han dynasty, the predominant material used for paper was hemp until the Tang dynasty when rattan and mulberry bark paper gradually prevailed. After the Tang dynasty, rattan paper declined because it required specific growing areas, was slow in growth, and had a long regeneration cycle. The most prestigious kind of bark paper was known as Chengxintang Paper, which emerged during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, and was only used for imperial purposes. Ouyang Xiu described it as shiny, elaborate, smooth, and elastic.[12] In the Eastern Jin period a fine bamboo screen-mould treated with insecticidal dye for permanence was used in papermaking. After printing was popularized during the Song dynasty the demand for paper grew substantially. The supply of bark could not keep up with the demand for paper, resulting in the invention of new kinds of paper using bamboo during the Song dynasty.[13] In the year 1101, 1.5 million sheets of paper were sent to the capital.[11]

Uses[edit]

Open, it stretches; closed, it rolls up. it can be contracted or expanded; hidden away or displayed.[8]

— Fu Xian

Among the earliest known uses of paper was padding and wrapping delicate bronze mirrors according to archaeological evidence dating to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han from the 2nd century BCE.[14] Padding doubled as both protection for the object as well as the user in cases where poisonous «medicine» were involved, as mentioned in the official history of the period.[14] Although paper was used for writing by the 3rd century CE,[15] paper continued to be used for wrapping (and other) purposes. Toilet paper was used in China from around the late 6th century.[16] In 589, the Chinese scholar-official Yan Zhitui (531–591) wrote: «Paper on which there are quotations or commentaries from Five Classics or the names of sages, I dare not use for toilet purposes».[16] An Arab traveler who visited China wrote of the curious Chinese tradition of toilet paper in 851, writing: «… [the Chinese] do not wash themselves with water when they have done their necessities; but they only wipe themselves with paper».[16]

During the Tang dynasty (618–907) paper was folded and sewn into square bags to preserve the flavor of tea. In the same period, it was written that tea was served from baskets with multi-colored paper cups and paper napkins of different size and shape.[14] During the Song dynasty (960–1279) the government produced the world’s first known paper-printed money, or banknote (see Jiaozi and Huizi). Paper money was bestowed as gifts to government officials in special paper envelopes.[16] During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the first well-documented European in Medieval China, the Venetian merchant Marco Polo remarked how the Chinese burned paper effigies shaped as male and female servants, camels, horses, suits of clothing and armor while cremating the dead during funerary rites.[17]

Impact of paper[edit]

According to Timothy Hugh Barrett, paper played a pivotal role in early Chinese written culture, and a «strong reading culture seems to have developed quickly after its introduction, despite political fragmentation.»[18] Indeed, the introduction of paper had immense consequences for the book world. It meant books would no longer have to be circulated in small sections or bundles, but in their entirety. Books could now be carried by hand rather than transported by cart. As a result, individual collections of literary works increased in the following centuries.[19]

Textual culture seems to have been more developed in the south by the early 5th century, with individuals owning collections of several thousand scrolls. In the north an entire palace collection might have been only a few thousand scrolls in total.[20] By the early 6th century, scholars in both the north and south were capable of citing upwards of 400 sources in commentaries on older works.[21] A small compilation text from the 7th century included citations to over 1,400 works.[22]

The personal nature of texts was remarked upon by a late 6th century imperial librarian. According to him, the possession of and familiarity with a few hundred scrolls was what it took to be socially accepted as an educated man.[23]

According to Endymion Wilkinson, one consequence of the rise of paper in China was that «it rapidly began to surpass the Mediterranean empires in book production.»[8] During the Tang dynasty, China became the world leader in book production. In addition the gradual spread of woodblock printing from the late Tang and Song further boosted their lead ahead of the rest of the world.[24]

From the fourth century CE to about 1500, the biggest library collections in China were three to four times larger than the largest collections in Europe. The imperial government book collections in the Tang numbered about 5,000 to 6,000 titles (89,000 juan) in 721. The Song imperial collections at their height in the early twelfth century may have risen to 4,000 to 5,000 titles. These are indeed impressive numbers, but the imperial libraries were exceptional in China and their use was highly restricted. Only very few libraries in the Tang and Song held more than one or two thousand titles (a size not even matched by the manuscript collections of the grandest of the great cathedral libraries in Europe).[25]

— Endymion Wilkinson

However, despite the initial advantage afforded to China by the paper medium, by the 9th century its spread and development in the Middle East had closed the gap between the two regions. Between the 9th to early 12th centuries, libraries in Cairo, Baghdad, and Cordoba held collections larger than even the ones in China, and dwarfed those in Europe. From about 1500 the maturation of paper making and printing in Southern Europe also had an effect in closing the gap with the Chinese. The Venetian Domenico Grimani’s collection numbered 15,000 volumes by the time of his death in 1523. After 1600, European collections completely overtook those in China. The Bibliotheca Augusta numbered 60,000 volumes in 1649 and surged to 120,000 in 1666. In the 1720s the Bibliothèque du Roi numbered 80,000 books and the Cambridge University 40,000 in 1715. After 1700, libraries in North America also began to overtake those of China, and toward the end of the century, Thomas Jefferson’s private collection numbered 4,889 titles in 6,487 volumes. The European advantage only increased further into the 19th century as national collections in Europe and America exceeded a million volumes while a few private collections, such as that of Lord Acton, reached 70,000.[25]

European book production began to catch up with China after the introduction of the mechanical printing press in the mid fifteenth century. Reliable figures of the number of imprints of each edition are as hard to find in Europe as they are in China, but one result of the spread of printing in Europe was that public and private libraries were able to build up their collections and for the first time in over a thousand years they began to match and then overtake the largest libraries in China.[24]

— Endymion Wilkinson

Paper became central to the three arts of China – poetry, painting, and calligraphy. In later times paper constituted one of the ‘Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio,’ alongside the brush, the ink, and the inkstone.[26]

«Five Oxen» by Han Huang (723–787), the earliest paper scroll painting of note by an identified artist

Paper in Asia[edit]

After its origin in central China, the production and use of paper spread steadily. It is clear that paper was used at Dunhuang by 150 CE, in Loulan in the modern-day province of Xinjiang by 200, and in Turpan by 399. Paper was concurrently introduced in Japan sometime between the years 280 and 610.[27]

Eastern Asia[edit]

Paper spread to Vietnam in the 3rd century, to Korea in the 4th century, and to Japan in the 5th century. The paper of Korea was famed for being glossy white and was especially prized for painting and calligraphy. It was among the items commonly sent to China as tribute. The Koreans spread paper to Japan possibly as early as the 5th century but the Buddhist monk Damjing’s trip to Japan in 610 is often cited as the official beginning of papermaking there.[19]

Islamic world[edit]

Origin[edit]

Paper was used in Central Asia by the 8th century but its origin is not clear. According to the 11th century Persian historian, Al-Thaʽālibī, Chinese prisoners captured at the Battle of Talas in 751 introduced paper manufacturing to Samarkand.[28][29] However there are no contemporary Arab sources for this battle. A Chinese prisoner, Du Huan, who later returned to China reported weavers, painters, goldsmiths, and silversmiths among the prisoners taken, but no papermakers. According to Al-Nadim, a writer in Baghdad during the 10th century, Chinese craftsmen made paper in Khorasan:[30]

Then there is the Khurasani paper made of flax, which some say appeared in the days of the Umayyads, while others say it was during the Abbasid regime. Some say that it was an ancient product and others say that it is recent. It is stated that craftsmen from China made it in Khurasan in the form of Chinese paper.[30]

— Al-Nadim

According to Jonathan Bloom – a scholar of Islamic and Asian Art with a focus on paper and printing, the connection between Chinese prisoners and the introduction of paper in Central Asia is «unlikely to be factual». Archaeological evidence shows that paper was already known and used in Samarkand decades before 751 CE. Seventy-six texts in Sogdian, Arabic, and Chinese have also been found near Panjakent, likely predating the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. Bloom argues that based on differences in Chinese and Central Asian papermaking techniques and materials, the story of Chinese papermakers directly introducing paper to Central Asia is probably metaphorical. Chinese paper was mostly made of bast fibers while Islamic paper was primarily made of waste material like rags.[30][31] The paper-making innovations in Central Asia may be pre-Islamic, probably aided by the Buddhist merchants and monks of China and Central Asia. The Islamic civilization helped spread paper and paper-making into the Middle East after the 8th-century, from where it arrived into Europe centuries later, and then to many other parts of the world. A historical remnant of this legacy is the continued use of the word «ream» to count bundles of paper, a word derived from Arabic rizma (bundle, bale).[30]

Shift from parchment to paper[edit]

During the 8th century, paper started to replace parchment as the primary writing material for administrative uses in Baghdad, the capital of Abbasids. According to Ibn Khaldun, a renowned Muslim historiographer, parchment was rare, and a great increase in the number of correspondents throughout Islamic territories, resulted in an order issued by Al-Fadl ibn Yahya, the Abbasid’s Grand Vizier, for the manufacture of paper to replace parchment.[32]

There are records of paper being made at Gilgit in Pakistan by the sixth century, in Samarkand by 751, in Baghdad by 793, in Egypt by 900, and in Fes, Morocco around 1100, in Syria e.g. Damascus, and Aleppo, in Andalusia around 12th century, in Persia e.g. Maragheh by 13th century, Isfahan by 14th century, Ghazvin and Kerman, in India e.g. Dowlat Abad by the 16th century.[33] A Persian geography book written by an unknown author in the 10th century, Hodud al-Alam, is the oldest known manuscripts mentioning papermaking industry in Samarkand. The writer stated that the city was famous for paper manufacturing and the product was exported to many other cities as a high-quality item.[34] Samarkand kept its reputation for papermaking over few centuries even once the industry spread across other Islamic areas. For instance, it is said that some Ministers in Egypt preferred ordering their required paper to Samarkand from which the paper was transported all the way to Egypt.[35]

In Baghdad, particular neighborhoods were allocated to paper manufacturing [36] and in Bazaar paper merchants and sellers owned distinct sectors being called Paper Market or Suq al-Warraqin, a street which was lined with more than 100 paper and booksellers’ shops.[37] In 1035 a Persian traveler, Nasir Khusraw, visiting markets in Cairo noted that vegetables, spices and hardware were wrapped in paper for the customers.[38] In the 12th century one street named «Kutubiyyin» or book sellers Morocco as it contained more than 100 bookshops.[39]

The expansion of public and private libraries and illustrated books within Islamic lands was one of the notable outcomes of the drastic increase in the availability of paper.[40] However, paper was still an upmarket good given the remarkable required inputs e.g. primary materials and labours to produce the item in the absence of advanced mechanical machinery. In one accountIbn al-Bawwab, a Persian calligrapher and illuminator, had been promised by the Sultan to be given precious garments in response to his services. When the Sultan deferred delivering the promised clothes, he instead proposed taking the papers stored in the Sultan’s library as his present.[35]

In another account, the hospitality of a Minister in Baghdad, Ibn Al-Forat, had been described by his generosity in freely giving away papers to his guests or visitors.[41]

Types of paper[edit]

A wide range of papers with distinctive properties and varying places of origin were manufactured and utilised across Islamic domains. Papers were typically named based on several criteria:

- Origins (e.g.Isfahani, Baghdadi, Halabi, Mesri, Samarkandi, Dowlat Abadi, Shami, Charta Damascena),

- Sizes (Solsan, Nesfi,…),

- People who have supported the paper development (e.g. Nuhi, Talhi, Jafari, Mamuni, Mansouri).[42]

Paper primary materials[edit]

Bast (hemp and flax), cotton, and old rags and ropes were the major input materials for producing the pulp. Sometimes a mixture of materials was also used for pulp making, such as cotton and hemp, or flax and hemp.[43][44] Other uncommon primary materials such as fig tree bark are also reported in some manuscripts.[45]

Papermaking process[edit]

Very few sources have mentioned the methods, phases and applied tools in the papermaking process though. A painting from an illustrated book in Persian has depicted different stages and required tools of the traditional workflow. The painting has distinguished two major phases of the papermaking process:

- Pulp making and pulp dewatering: water power mill mixes linen wastes (Karbas) and rags, as the primary materials of papermaking, with water. They are well beaten in stone pits. In the next step, the watery pulp is poured into a piece of fabric, tied around two workers’ waists, to get initially dewatered and probably homogenised and purified. Once the pulp is dewatered into a considerable extent it passes through the next treatment phase.

- Paper final treatments: this phase consists of several consequent steps e.g moulding the pulp with a square laid with wire-like lines (dipping the mould in the vat containing pulp), pressing, sizing, drying and polishing. Each step in this phase is undertaken by a particular device. For instance, in the drying process, the paper was stuck to the wall with the use of horsehair.

Traditional paper making process-Oriental Paper

A manuscript from the 13th century has also elaborated the process of papermaking. This text shows how papermakers were undertaking multiple steps to produce high-quality paper. This papermaking instruction or recipe is a chapter under the title of al-kâghad al-baladî (local paper) from the manuscript of al-Mukhtara’fî funûn min al-ṣunan attributed to al-Malik al-Muẓaffar, a Yemeni ruler of Rasulids. The bark of fig trees, as the main source of papermaking in this recipe, went through frequent cycles of soaking, beating and drying. The process was taking 12 days to produced 100 sheets of high-quality paper. During the pulping stage, the beaten fibres were transformed into different sizes of Kubba (cubes) which they were used as standard scales to manufacture a certain number of sheets. The dimensions were determined based on three citrus fruit: limun (lemon), utrunja (orange) and narenja (Tangerine). A summarized version of this detailed process is as below. Each individual phase was repeated several times.

- Soaking paper in a pool

- Dewatering paper through squeezing and pressing

- Making balls from the pulp

- Pressing the balls

- Drying the paper by sticking them to the wall and exposing the final product into the sun[45]

Paper properties[edit]

Near Eastern paper is mainly characterized by sizing with a variety of starches such as rice, katira, wheat and white sorghum. Rice and white sorghum were more widely used.[46][45] Paper usually was placed on a hard surface and a smooth device called mohreh was used to rub the starch against the paper until it became perfectly shiny.[47]

The laborious process of papermaking was refined and machinery was designed for bulk manufacturing of paper. Production began in Baghdad, where a method was invented to make a thicker sheet of paper, which helped transform papermaking from an art into a major industry.[48] The use of water-powered pulp mills for preparing the pulp material used in papermaking dates back to Samarkand in the 8th century.[49] The use of human/animal-powered paper mills has also been identified in Abbasid-era Baghdad during 794–795,[50] though this should not be confused with later water-powered paper mills (see Paper mills section below). The Muslims also introduced the use of trip hammers (human- or animal-powered) in the production of paper, replacing the traditional Chinese mortar and pestle method. In turn, the trip hammer method was later employed by the Chinese.[51] Historically, trip hammers were often powered by a water wheel, and are known to have been used in China as long ago as 40 BCE or maybe even as far back as the Zhou Dynasty (1050 BCE–221 BCE),[52] though the trip hammer is not known to have been used in Chinese papermaking until after its use in Muslim papermaking.[51]

By the 9th century, Muslims were using paper regularly, although for important works like copies of the revered Qur’an, vellum was still preferred.[53] Advances in book production and bookbinding were introduced.[54][unreliable source]

In Muslim countries they made books lighter—sewn with silk and bound with leather-covered paste boards; they had a flap that wrapped the book up when not in use. As paper was less reactive to humidity, the heavy boards were not needed.

Since the First Crusade in 1096, paper manufacturing in Damascus had been interrupted by wars, but its production continued in two other centres. Egypt continued with the thicker paper, while Iran became the center of the thinner papers. Papermaking was diffused across the Islamic world, from where it travelled further toward west into Europe.[55] Paper manufacture was introduced to India in the 13th century by Arab merchants, where it almost wholly replaced traditional writing materials.[53]

Indian subcontinent[edit]

The Weber manuscripts (above) were discovered in Kucha (Xinjiang, China), now preserved in the Bodleian Library (Oxford). They are a collection of 9 manuscript fragments, originally created on paper, and dated to the 5th to 6th century CE. Four were on Nepalese-origin paper (above: upper, off-white), others on Central Asian paper (lower, brown). Eight in good Sanskrit language written in two scripts, one in grammatically poor, mixed Sanskrit and Pali.[56][57]

The evidence of paper use on the Indian subcontinent appears first in the second half of the 7th century.[19][58] Its use is mentioned by 7th– and 8th-century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim memoirs as well as some Indian Buddhists, as Kakali and Śaya – likely Indian transliteration of Chinese Zhǐ (tsie).[58][59] Yijing wrote about the practice of priests and laypeople in India printing Buddha image on silk or paper, and worshipping these images. Elsewhere in his memoir, I-Ching wrote that Indians use paper to make hats, to reinforce their umbrellas and for sanitation.[58] Xuangzang mentions carrying 520 manuscripts from India back to China in 644 CE, but it is unclear if any of these were on paper.[60]

Thin sheets of birch bark and specially treated palm-leaves remained the preferred writing surface for literary works through late medieval period in most of India.[60] The earliest Sanskrit paper manuscript found is a paper copy of the Shatapatha Brahmana in Kashmir, dated to 1089, while the earliest Sanskrit paper manuscripts in Gujarat are dated between 1180 and 1224.[61] Some of oldest surviving paper manuscripts have been found in Jain temples of Gujarat and Rajasthan, and paper use by Jain scribes is traceable to around 12th-century.[60] According to the historical trade-related archives such as Cairo Geniza found in the synagogues of the Middle East, Jewish merchants – such as Ben Yiju originally from Tunisia who moved to India – imported large quantities of paper into ports of Gujarat, Malabar coast and other parts of India by the 11th-century to partly offset the goods they exported from India.[62][63]

According to Irfan Habib, it is reasonable to presume that paper manufacturing reached Sindh (now part of south Pakistan) before 11th-century with the start of Arab rule in Sindh.[61] Fragments of Arabic manuscripts found in the Sindhi city ruins of Mansura, which was destroyed circa 1030, confirm the use of paper in Sindh.[61] Amir Khusrau of Delhi Sultanate mentions paper-making operations in 1289.[61]

In the 15th century, Chinese traveler Ma Huan praised the quality of paper in Bengal, describing it as white paper that is made from «bark of a tree» and is as «glossy and smooth as deer’s skin».[64] The use of tree bark as a raw material for paper suggests that the paper manufacturing in the eastern states of India may have come directly from China, rather than Sultanates formed by West Asian or Central Asian conquests.[61] Paper technology likely arrived in India from China through Tibet and Nepal around mid-7th century, when Buddhist monks freely traveled, exchanged ideas and goods between Tibet and Buddhist centers in India.[58] This exchange is evidenced by the Indian talapatra binding methods that were adopted by Chinese monasteries such as at Tunhuang for preparing sutra books from paper. Most of the earliest surviving sutra books in Tibetan monasteries are on Chinese paper strips held together with Indian manuscript binding methods.[65] Further, the analysis of the woodblock book covers of these historic manuscripts has confirmed that it was made of tropical wood indigenous to India, not Tibet.[60]

Paper in Europe[edit]

The oldest known paper document in Europe is the Mozarab Missal of Silos from the 11th century,[66] probably using paper made in the Islamic part of the Iberian Peninsula. They used hemp and linen rags as a source of fiber. The first recorded paper mill in the Iberian Peninsula was in Xàtiva in 1056.[67][68]

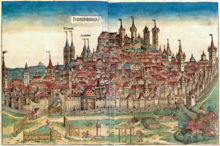

Papermaking reached Europe as early as 1085 in Toledo and was firmly established in Xàtiva, Spain by 1150. During the 13th century mills were established in Amalfi, Fabriano, and Treviso, Italy, and other Italian towns by 1340. Papermaking then spread further northwards, with evidence of paper being made in Troyes, France by 1348, in Holland sometime around 1340–1350, and in Nuremberg, Germany by 1390 in a mill set up by Ulman Stromer.[69] This was just about the time when the woodcut printmaking technique was transferred from fabric to paper in the old master print and popular prints. There was a paper mill in Switzerland by 1432 and the first mill in England was set up by John Tate around 1490 near Hertford,[70][71] but the first commercially successful paper mill in Britain did not occur before 1588 when John Spilman set up a mill near Dartford in Kent.[72] During this time, paper making spread to Austria by 1469,[73] to Poland by 1491, to Russia by 1576, to the Netherlands by 1586, to Denmark by 1596, and to Sweden by 1612.[33]

Arab prisoners who settled in a town called Borgo Saraceno in the Italian Province of Ferrara introduced Fabriano artisans in the Province of Ancona[clarification needed] the technique of making paper by hand. At the time they were renowned for their wool-weaving and manufacture of cloth. Fabriano papermakers considered the process of making paper by hand an art form and were able to refine the process to successfully compete with parchment which was the primary medium for writing at the time. They developed the application of stamping hammers to reduce rags to pulp for making paper, sizing paper by means of animal glue, and creating watermarks in the paper during its forming process. The Fabriano used glue obtained by boiling scrolls or scraps of animal skin to size the paper; it is suggested that this technique was recommended by the local tanneries. The introduction of the first European watermarks in Fabriano was linked to applying metal wires on a cover laid against the mould which was used for forming the paper.[74]

They adapted the waterwheels from the fuller’s mills to drive a series of three wooden hammers per trough. The hammers were raised by their heads by cams fixed to a waterwheel’s axle made from a large tree trunk.[75][76]

Americas[edit]

Amate is similar to modern paper but has a more fibrous texture.

In the Americas, archaeological evidence indicates that a similar bark-paper writing material was used by the Maya no later than the 5th century CE.[77] Called amatl or amate, it was in widespread use among Mesoamerican cultures until the Spanish conquest. The earliest sample of amate was found at Huitzilapa near the Magdalena Municipality, Jalisco, Mexico, belonging to the shaft tomb culture. It is dated to 75 BCE.[78]

The production of amate is much more similar to paper than papyrus. The bark material is soaked in water, or in modern methods boiled, so that it breaks down into a mass of fibres. They are then laid out in a frame and pressed into sheets. It is a true paper product in that the material is not in its original form, but the base material has much larger fibres than those used in modern papers. As a result, amate has a rougher surface than modern paper, and may dry into a sheet with hills and valleys as the different length fibres shrink.

European papermaking spread to the Americas first in Mexico by 1575 and then in Philadelphia by 1690.[33]

United States[edit]

The American paper industry began with the establishment of the first paper mill in British America in 1690 by William Rittenhouse of Philadelphia with the help of Pennsylvania’s first printer, William Bradford. For two decades it would remain the only mill in the colonies, and for the next two centuries the city would remain the preeminent center of paper manufacturing and publishing. The first paper mills relied solely on rag paper production, with cotton rags generally imported from Europe. However by the mid-19th century the sulfite process had begun to proliferate in other regions with better access to wood pulp, and by 1880, America had become the largest producer of paper goods in the world. While the Delaware Valley remained an important region in paper production and publishing through the late nineteenth century, Philadelphia was overtaken by regions using these new processes which had greater access to water power and wood pulp.[79]

The earliest of these mills were centered in New England and Upstate New York, the latter of which became home to International Paper, the largest pulp and paper company in the world, which held a 20% market share in 2017,[80] and at its peak produced more than 60% of the continent’s newsprint in 1898, before an industry shift to Canada.[81] Chief among papermaking cities in New England and the world was Holyoke, Massachusetts, at one time making 80% of the writing paper of the United States and home to the ill-fated American Writing Paper Company, the world’s largest producer of fine papers by 1920.[82][83] By 1885 the Paper City, as it is still called, produced 190 tons per day, more than twice Philadelphia’s capacity.[84] Quickly it became a hub of paper machinery and turbine technology, host to the largest paper mills in the world in the 1890s, and D. H. & A. B. Tower, the largest paper mill engineering firm in the United States in the 19th century.[85] The Tower Brothers and their associates would be responsible for designing mills on five continents.[86] In the United States the firm supported the Berkshires’ paper industry, building the first mills used to make U.S. currency by the Crane Company, as well as the first sulfite process mills of Kimberly Clark in Wisconsin, allowing the company to be the first west of the Appalachians to adopt the process, with access to vast forest resources.[87][88]

The pulp and paper industry continued to develop in other regions, including California, Ohio’s Miami Valley, with centers in Dayton, Hamilton, and Cincinnati, as well as regions of the South, like Texas and Georgia, the latter being home to Georgia Pacific and WestRock, the 2nd and 3rd respective largest paper producers in the United States today.[80][89] Wisconsin’s industry nevertheless endured and as of 2019 it had far and away the most paper manufacturers in the country, with 34 such enterprises. While only smaller specialty manufacturers remained in Pennsylvania and New England, New York retained 28 mills, followed by Georgia with 20, Michigan with 17, and Alabama with 16 respectively.[90]

Paper mills[edit]

The Nuremberg paper mill, the building complex at the lower right corner, in 1493. Due to their noise and smell, paper mills were required by medieval law to be erected outside the city perimeter.

The use of human and animal powered mills was known to Chinese and Muslim papermakers. However, the evidence for water-powered paper mills is elusive among both prior to the 11th century.[91][92][93][94] Scholars have identified paper mills, likely human or animal powered, in Abbasid-era Baghdad during 794–795.[50]

It is evident that throughout the Islamic lands e.g. Iran, Syria (Hama and Damascus), and North Africa (Egypt and Tripoli) water power mills were extensively used to beat the flax and rag wastes to prepare the paper pulp [95]

The Water mill was built under Abd al-Rahman II in Córdoba

Donald Hill has identified a possible reference to a water-powered paper mill in Samarkand, in the 11th-century work of the Persian scholar Abu Rayhan Biruni, but concludes that the passage is «too brief to enable us to say with certainty» that it refers to a water-powered paper mill.[96] This is seen by Halevi as evidence of Samarkand first harnessing waterpower in the production of paper, but notes that it is not known if waterpower was applied to papermaking elsewhere across the Islamic world at the time.[97] Burns remains sceptical, given the isolated occurrence of the reference and the prevalence of manual labour in Islamic papermaking elsewhere prior to the 13th century.[98]

Clear evidence of a water-powered paper mill dates to 1282 in the Spanish Kingdom of Aragon.[99] A decree by the Christian king Peter III addresses the establishment of a royal «molendinum», a proper hydraulic mill, in the paper manufacturing centre of Xàtiva.[99] The crown innovation was operated by the Muslim Mudéjar community in the Moorish quarter of Xàtiva,[100] though it appears to have been resented by sections of the local Muslim papermakering community; the document guarantees them the right to continue the way of traditional papermaking by beating the pulp manually and grants them the right to be exempted from work in the new mill.[99] Paper making centers began to multiply in the late 13th century in Italy, reducing the price of paper to one sixth of parchment and then falling further; paper making centers reached Germany a century later.[101]

The first paper mill north of the Alps was established in Nuremberg by Ulman Stromer in 1390; it is later depicted in the lavishly illustrated Nuremberg Chronicle.[102] From the mid-14th century onwards, European paper milling underwent a rapid improvement of many work processes.[103]

Fiber sources[edit]

Before the industrialisation of the paper production the most common fibre source was recycled fibres from used textiles, called rags. The rags were from hemp, linen and cotton.[104] It was not until the introduction of wood pulp in 1843 that paper production was not dependent on recycled materials from ragpickers.[104] It was not realized at the time how unstable wood pulp paper is.

A means of removing printing inks from paper, allowing it to be re-used, was invented by German jurist Justus Claproth in 1774.[104] Today this process is called deinking.

19th-century advances in papermaking[edit]

Although cheaper than vellum, paper remained expensive, at least in book-sized quantities, through the centuries, until the advent of steam-driven paper making machines in the 19th century, which could make paper with fibres from wood pulp. Although older machines pre-dated it, the Fourdrinier papermaking machine became the basis for most modern papermaking. Nicholas Louis Robert of Essonnes, France, was granted a patent for a continuous paper making machine in 1799. At the time he was working for Leger Didot with whom he quarrelled over the ownership of the invention. Didot sent his brother-in-law, John Gamble, to meet Sealy and Henry Fourdrinier, stationers of London, who agreed to finance the project. Gamble was granted British patent 2487 on 20 October 1801. With the help particularly of Bryan Donkin, a skilled and ingenious mechanic, an improved version of the Robert original was installed at Frogmore Paper Mill, Hertfordshire, in 1803, followed by another in 1804. A third machine was installed at the Fourdriniers’ own mill at Two Waters. The Fourdriniers also bought a mill at St Neots intending to install two machines there and the process and machines continued to develop.

However, experiments with wood showed no real results in the late 18th century and at the start of the 19th century. By 1800, Matthias Koops (in London, England) further investigated the idea of using wood to make paper, and in 1801 he wrote and published a book titled Historical account of the substances which have been used to describe events, and to convey ideas, from the earliest date, to the invention of paper.[105] His book was printed on paper made from wood shavings (and adhered together). No pages were fabricated using the pulping method (from either rags or wood). He received financial support from the royal family to make his printing machines and acquire the materials and infrastructure needed to start his printing business. But his enterprise was short lived. Only a few years following his first and only printed book (the one he wrote and printed), he went bankrupt. The book was very well done (strong and had a fine appearance), but it was very costly.[106][107][108]

Then in the 1830s and 1840s, two men on two different continents took up the challenge, but from a totally new perspective. Both Friedrich Gottlob Keller and Charles Fenerty began experiments with wood but using the same technique used in paper making; instead of pulping rags, they thought about pulping wood. And at about the same time, by mid-1844, they announced their findings. They invented a machine which extracted the fibres from wood (exactly as with rags) and made paper from it. Charles Fenerty also bleached the pulp so that the paper was white. This started a new era for paper making. By the end of the 19th-century almost all printers in the western world were using wood instead of rags to make paper.[109]

Together with the invention of the practical fountain pen and the mass-produced pencil of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th-century economy and society in industrialized countries. With the introduction of cheaper paper, schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction, and newspapers became gradually available by 1900. Cheap wood based paper also meant that keeping personal diaries or writing letters became possible[clarification needed] and so, by 1850, the clerk, or writer, ceased to be a high-status job.[citation needed]

Unfortunately, early wood-based paper deteriorated as time passed, meaning that much of the output of newspapers and books from this period either has disintegrated or is in poor condition; some has been photographed or digitized (scanned). The acid nature of the paper, caused by the use of alum, produced what has been called a slow fire, slowly converting the paper to ash. Documents needed to be written on more expensive rag paper. In the 2nd half of the 20th century cheaper acid-free paper based on wood was developed, and it was used for hardback and trade paperback books. However, paper that has not been de-acidified was still cheaper, and remains in use (2020) for mass-market paperback books, newspapers, and in underdeveloped countries.

Determining provenance[edit]

Determining the provenance of paper is a complex process that can be done in a variety of ways. The easiest way is using a known sheet of paper as an exemplar. Using known sheets can produce an exact identification. Next, comparing watermarks with those contained in catalogs or trade listings can yield useful results. Inspecting the surface can also determine age and location by looking for distinct marks from the production process. Chemical and fiber analysis can be used to establish date of creation and perhaps location.[110][page needed]

See also[edit]

- Kaghaz

- History of origami

- Paperless office

Notes[edit]

- ^ Confusingly, parchment paper is a treated paper used in baking, and unrelated to true parchment.

References[edit]

- ^ 香港臨時市政局 [Provisional Urban Council]; 中國歷史博物館聯合主辦 [Hong Kong Museum of History] (1998). «Zàozhǐ» 造纸 [Papermaking]. Tian gong kai wu: Zhongguo gu dai ke ji wen wu zhan 天工開物 中國古代科技文物展 [Heavenly Creations: Gems of Ancient Chinese Inventions] (in Chinese and English). Hong Kong: 香港歷史博物館 [Hong Kong Museum of History]. p. 60. ISBN 978-962-7039-37-2. OCLC 41895821.

- ^ a b c d Barrett 2008, p. 34.

- ^

«Papyrus definition». Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2008-11-20. - ^ a b Tsien 1985, p. 38

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 2

- ^ a b

David Buisseret (1998), Envisaging the City, U Chicago Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-226-07993-6 - ^ a b c d Wilkinson 2012, p. 908.

- ^ Papermaking. (2007). In: Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ «New Evidence suggests longer paper making history in China». World Archeological Congress. August 2006. Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- ^ a b

Tsien 1985, p. 40 uses Wade-Giles transcription - ^ Lu 2015, p. 175-177.

- ^ Lu 2015, p. 178-179.

- ^ a b c Tsien 1985, p. 122

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 1

- ^ a b c d Tsien 1985, p. 123

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 105

- ^ Barrett 2008, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 2012, p. 909.

- ^ Barrett 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Barrett 2008, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Barrett 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Barrett 2008, p. 39.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2012, p. 935.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2012, p. 934.

- ^ Barrett 2008, p. 40.

- ^ DeVinne, Theo. L. The Invention of Printing. New York: Francis Hart & Co., 1876. p. 134

- ^ Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. (pp 58) ISBN 0-471-29198-6

- ^ Quraishi, Silim «A survey of the development of papermaking in Islamic Countries», Bookbinder, 1989 (3): 29–36.

- ^ a b c d Bloom, Jonathan (2001). Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 8–10, 42–45. ISBN 0-300-08955-4.