«Azeri language» redirects here. For the extinct Iranian language, see Old Azeri.

| Azerbaijani | |

|---|---|

| Azeri | |

| Azərbaycan dili, آذربایجان دیلی, Азәрбајҹан дили[note 1] | |

Azerbaijani in Perso-Arabic Nastaliq (Iran), Latin (Azerbaijan), and Cyrillic (Russia). |

|

| Pronunciation | [ɑːzæɾbɑjˈdʒɑn diˈli] |

| Native to |

|

| Region | Iranian Azerbaijan, South Caucasus |

| Ethnicity | Azerbaijanis |

|

Native speakers |

24 million (2022)[2] |

|

Language family |

Turkic

|

|

Early form |

Ajem-Turkic |

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

|

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

Azerbaijan Dagestan (Russia) Organization of Turkic States |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | az |

| ISO 639-2 | aze |

| ISO 639-3 | aze – inclusive codeIndividual codes: azj – North Azerbaijaniazb – South Azerbaijanislq – Salchuqqxq – Qashqai |

| Glottolog | mode1262 |

| Linguasphere | part of 44-AAB-a |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Azerbaijani () or Azeri (), also referred to as Azeri Turkic, Azeri Turkish, or simply Turki/Torki,[b] is a Turkic language from the Oghuz sub-branch spoken primarily by the Azerbaijani people, who live mainly in the Republic of Azerbaijan where the North Azerbaijani variety is spoken, and in the Azerbaijan region of Iran, where the South Azerbaijani variety is spoken.[5][6] Although there is a very high degree of mutual intelligibility between both forms of Azerbaijani, there are significant differences in phonology, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and sources of loanwords.

North Azerbaijani has official status in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Dagestan (a federal subject of Russia), but South Azerbaijani does not have official status in Iran, where the majority of Azerbaijani people live. It is also spoken to lesser varying degrees in Azerbaijani communities of Georgia and Turkey and by diaspora communities, primarily in Europe and North America.

Both Azerbaijani varieties are members of the Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. The standardized form of North Azerbaijani (spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Russia) is based on the Shirvani dialect, while South Azerbaijani uses the Tabrizi dialect as its prestige variety. Since the Republic of Azerbaijan’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Northern Azerbaijani uses the Latin script. South Azerbaijani, on the other hand, has always used and continues to use the Perso-Arabic script. Azerbaijani language is closely related to Gagauz, Qashqai, Crimean Tatar, Turkish, and Turkmen, sharing varying degrees of mutual intelligibility with each of those languages.

Etymology and background[edit]

Historically the language was referred by its native speakers as türk dili or türkcə[7], meaning either «Turkish» or «Turkic». After the establishment of the Azerbaijan SSR,[8] on the order of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the «name of the formal language» of the Azerbaijan SSR was changed from «Turkish» to «Azerbaijani».[8]

History and evolution[edit]

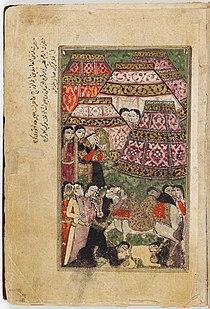

Garden of Pleasures by Fuzûlî in Azerbaijani from 16th century.[9]

Azerbaijani evolved from the Eastern branch of Oghuz Turkic («Western Turkic»)[10] which spread to the Caucasus, in Eastern Europe,[11][12] and northern Iran, in Western Asia, during the medieval Turkic migrations.[13] Persian and Arabic influenced the language, but Arabic words were mainly transmitted through the intermediary of literary Persian.[14] Azerbaijani is, perhaps after Uzbek, the Turkic language upon which Persian and other Iranian languages have exerted the strongest impact—mainly in phonology, syntax, and vocabulary, less in morphology.[15]

The Turkic language of Azerbaijan gradually supplanted the Iranian languages in what is now northwestern Iran, and a variety of languages of the Caucasus and Iranian languages spoken in the Caucasus, particularly Udi and Old Azeri. By the beginning of the 16th century, it had become the dominant language of the region. It was a spoken language in the court of the Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars.

The historical development of Azerbaijani can be divided into two major periods: early (c. 14th to 18th century) and modern (18th century to present). Early Azerbaijani differs from its descendant in that it contained a much larger number of Persian and Arabic loanwords, phrases and syntactic elements. Early writings in Azerbaijani also demonstrate linguistic interchangeability between Oghuz and Kypchak elements in many aspects (such as pronouns, case endings, participles, etc.). As Azerbaijani gradually moved from being merely a language of epic and lyric poetry to being also a language of journalism and scientific research, its literary version has become more or less unified and simplified with the loss of many archaic Turkic elements, stilted Iranisms and Ottomanisms, and other words, expressions, and rules that failed to gain popularity among the Azerbaijani masses.

The Russian annexation of Iran’s territories in the Caucasus through the Russo-Iranian wars of 1804–1813 and 1826-1828 split the language community across two states. Afterwards, the Tsarist administration encouraged the spread of Azerbaijani in eastern Transcaucasia as a replacement for Persian spoken by the upper classes, and as a measure against Persian influence in the region.[16][17]

Between c. 1900 and 1930, there were several competing approaches to the unification of the national language in what is now the Azerbaijan Republic, popularized by scholars such as Hasan bey Zardabi and Mammad agha Shahtakhtinski. Despite major differences, they all aimed primarily at making it easy for semi-literate masses to read and understand literature. They all criticized the overuse of Persian, Arabic, and European elements in both colloquial and literary language and called for a simpler and more popular style.

The Soviet Union promoted the development of the language but set it back considerably with two successive script changes[18] – from the Persian to Latin and then to the Cyrillic script – while Iranian Azerbaijanis continued to use the Persian script as they always had. Despite the wide use of Azerbaijani in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, it became the official language of Azerbaijan only in 1956.[19] After independence, the Republic of Azerbaijan decided to switch back to a modified Latin script.

Azerbaijani literature[edit]

The development of Azerbaijani literature is closely associated with Anatolian Turkish, written in Perso-Arabic script. Examples of its detachment date to the 14th century or earlier.[20][21] Kadi Burhan al-Din, Hesenoghlu, and Imadaddin Nasimi helped to establish Azerbaiijani as a literary language in the 14th century through poetry and other works.[21] The ruler of the Qara Qoyunlu state, Jahanshah, wrote poems in Azerbaijani language with the nickname «Haqiqi».[22][23] Sultan Yaqub, the ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu state, wrote poems in the Azerbaijani language.[24] The ruler and poet Ismail I wrote under the pen name Khatā’ī (which means «sinner» in Persian) during the fifteenth century.[25][26] During the 16th century, the poet, writer and thinker Fuzûlî wrote mainly in Azerbaijani but also translated his poems into Arabic and Persian.[25]

Starting in the 1830s, several newspapers were published in Iran during the reign of the Azerbaijani speaking Qajar dynasty but it is unknown whether any of these newspapers were written in Azerbaijani. In 1875, Akinchi (Əkinçi / اکينچی) («The Ploughman») became the first Azerbaijani newspaper to be published in the Russian Empire. It was started by Hasan bey Zardabi, a journalist and education advocate.[21]

Following the rule of the Qajar dynasty, Iran was ruled by Reza Shah who banned the publication of texts in Azerbaijani.[citation needed] Modern literature in the Republic of Azerbaijan is based on the Shirvani dialect mainly, while in Iranian Azerbaijan, it is based on the Tabrizi dialect.

Mohammad-Hossein Shahriar is an important figure in Azerbaijani poetry. His most important work is Heydar Babaya Salam and it is considered to be a pinnacle of Azerbaijani literature and gained popularity in the Turkic-speaking world. It was translated into more than 30 languages.[27]

In the mid-19th century, Azerbaijani literature was taught at schools in Baku, Ganja, Shaki, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. Since 1845, it has also been taught in the Saint Petersburg State University in Russia. In 2018, Azerbaijani language and literature programs are offered in the United States at several universities, including Indiana University, UCLA, and University of Texas at Austin.[21] The vast majority, if not all Azerbaijani language courses teach North Azerbaijani written in the Latin script and not South Azerbaijani written in the Perso-Arabic script.

Modern literature in the Republic of Azerbaijan is primarily based on the Shirvani dialect, while in the Iranian Azerbaijan region (historic Azerbaijan) it is based on the Tabrizi one.

Lingua franca[edit]

Azerbaijani served as a lingua franca throughout most parts of Transcaucasia except the Black Sea coast, in southern Dagestan,[28][29][30] the Eastern Anatolia Region and all over Iran [31] from the 16th to the early 20th centuries,[32][33] alongside cultural, administrative, court literature, and most importantly official language (along with Azerbaijani) of all these regions, namely Persian.[34] From the early 16th century up to the course of the 19th century, these regions and territories were all ruled by the Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars until the cession of Transcaucasia proper and Dagestan by Qajar Iran to the Russian Empire per the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan and the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay. Per the 1829 Caucasus School Statute, Azerbaijani was to be taught in all district schools of Ganja, Shusha, Nukha (present-day Shaki), Shamakhi, Quba, Baku, Derbent, Yerevan, Nakhchivan, Akhaltsikhe, and Lankaran. Beginning in 1834, it was introduced as a language of study in Kutaisi instead of Armenian. In 1853, Azerbaijani became a compulsory language for students of all backgrounds in all of Transcaucasia with the exception of the Tiflis Governorate.[35]

Dialects of Azerbaijani[edit]

Reza Shah and Kemal Atatürk in Turkey.

Azerbaijani is one of the Oghuz languages within the Turkic language family. Ethnologue classifies North Azerbaijani (spoken mainly in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Russia) and South Azerbaijani (spoken in Iran, Iraq, and Syria) as separate languages with «significant differences in phonology, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and loanwords.»[3] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) also considers Northern and Southern Azerbaijani to be distinct languages.[36]

Svante Cornell wrote in his 2001 book Small Nations and Great Powers that «it is certain that Russian and Iranian words (sic), respectively, have entered the vocabulary on either side of the Araxes river, but this has not occurred to an extent that it could pose difficulties for communication».[37] There are numerous dialects, with 21 North Azerbaijani dialects and 11 South Azerbaijani dialects identified by Ethnologue.[3][4]

Four varieties have been accorded ISO 639-3 language codes: North Azerbaijani, South Azerbaijani, Salchuq, and Qashqai. The Glottolog 4.1 database classifies North Azerbaijani, with 20 dialects, and South Azerbaijani, with 13 dialects, under the Modern Azeric family, a branch of Central Oghuz.[38]

In the northern dialects of the Azerbaijani language, linguists find traces of the influence of the Khazar language.[39]

According to the Linguasphere Observatory, all Oghuz languages form part of a single «outer language» of which North and South Azerbaijani are «inner languages».[citation needed]

North Azerbaijani[edit]

Azerbaijani-language road sign.

North Azerbaijani,[3] or Northern Azerbaijani, is the official language of the Republic of Azerbaijan. It is closely related to modern-day Istanbul Turkish, the official language of Turkey. It is also spoken in southern Dagestan, along the Caspian coast in the southern Caucasus Mountains and in scattered regions throughout Central Asia. As of 2011, there are some 9.23 million speakers of North Azerbaijani including 4 million monolingual speakers (many North Azerbaijani speakers also speak Russian, as is common throughout former USSR countries).[3]

The Shirvan dialect as spoken in Baku is the basis of standard Azerbaijani. Since 1992, it has been officially written with a Latin script in the Republic of Azerbaijan, but the older Cyrillic script was still widely used in the late 1990s.[40]

Ethnologue lists 21 North Azerbaijani dialects: Quba, Derbend, Baku, Shamakhi, Salyan, Lankaran, Qazakh, Airym, Borcala, Terekeme, Qyzylbash, Nukha, Zaqatala (Mugaly), Qabala, Yerevan, Nakhchivan, Ordubad, Ganja, Shusha (Karabakh), Karapapak.[3]

South Azerbaijani[edit]

South Azerbaijani,[4] or Iranian Azerbaijani,[c] is widely spoken in Iranian Azerbaijan and, to a lesser extent, in neighboring regions of Turkey and Iraq, with smaller communities in Syria. In Iran, the Persian word for Azerbaijani is borrowed as Torki «Turkic».[4] In Iran, it is spoken mainly in East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil and Zanjan. It is also widely spoken in Tehran and across Tehran Province, as Azerbaijanis form by far the largest minority in the city and the wider province,[42] comprising about 1⁄6[43][44] of its total population. The CIA World Factbook reports that in 2010, the percentage of Iranian Azerbaijani speakers at around 16 percent of the Iranian population, or approximately 13 million people worldwide,[45] and ethnic Azeris form by far the second largest ethnic group of Iran, thus making the language also the second most spoken language in the nation. Ethnologue reports 10.9 million Iranian Azerbaijani in Iran in 2016 and 13,823,350 worldwide.[4]

Dialects of South Azerbaijani include: Aynallu (Inallu, Inanlu), Qarapapaq, Tabrizi, Qashqai, Afshari (Afsar, Afshar), Shahsavani (Shahseven), Muqaddam, Baharlu (Kamesh), Nafar, Qaragözlü, Pishaqchi (Bıçaqçı), Bayatlu, Qajar, Marandli.[4]

Comparison with other Turkic languages[edit]

Azerbaijani and Turkish[edit]

North and South Azerbaijani speakers and Turkish speakers can communicate with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Turkish soap operas are very popular with Azeris in both Iran and Azerbaijan. Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran (who spoke South Azerbaijani) met with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of Turkey (who spoke Turkish) in 1934; the two were filmed speaking their respective language to each other and communicated effectively.[46][47]

Speakers of Turkish and Azerbaijani can, to an extent, communicate with each other as both languages have substantial variation and are to a degree mutually intelligible, though it is easier for a speaker of Azerbaijani to understand Turkish than the other way around.[48]

In a 2011 study, 30 Turkish participants were tested to determine how well they understood written and spoken Azerbaijani. It was found that even though Turkish and Azerbaijani are typologically similar languages, on the part of Turkish speakers the intelligibility is not as high as is estimated.[49] In a 2017 study, Iranian Azerbaijanis scored in average 56% of receptive intelligibility in spoken language of Turkish.[50]

Azerbaijani exhibits a similar stress pattern to Turkish but simpler in some respects. Azerbaijani is a strongly stressed and partially stress-timed language, unlike Turkish which is weakly stressed and syllable-timed.

Below are some words with different pronunciations in Azerbaijani and Turkish but have the same meaning in both languages:

| Azerbaijani | Turkish | English |

|---|---|---|

| ayaqqabı/başmaq | ayakkabı | shoes |

| ayaq | ayak | foot |

| kitab | kitap | book |

| qan | kan | blood |

| qaz | kaz | goose |

| qaş | kaş | eyebrow |

| qar | kar | snow |

| daş | taş | stone |

Azerbaijani and Turkmen[edit]

The 1st person personal pronoun is mən in Azerbaijani just as men in Turkmen, whereas it is ben in Turkish. The same is true for demonstrative pronouns bu, where sound b is replaced with sound m. For example: bunun>munun/mının, muna/mına, munu/munı, munda/mında, mundan/mından.[51] This is observed in the Turkmen literary language as well, where the demonstrative pronoun bu undergoes some changes just as in: munuñ, munı, muña, munda, mundan, munça.[52] b>m replacement is encountered in many dialects of the Turkmen language and may be observed in such words as: boyun>moyın in Yomut — Gunbatar dialect, büdüremek>müdüremek in Ersari and Stavropol Turkmens’ dialects, bol>mol in Karakalpak Turkmens’ dialects, buzav>mizov in Kirac dialects.[53]

Here are some words from the Swadesh list to compare Azerbaijani with Turkmen:[54]

| Azerbaijani | Turkmen | English |

|---|---|---|

| mən | men | I, me |

| sən | sen | you |

| haçan | haçan | when |

| başqa | başga | other |

| it, köpək | it, köpek | dog |

| dəri | deri | skin, leather |

| yumurta | ýumurtga | egg |

| ürək | ýürek | heart |

| eşitmək | eşitmek | to hear |

Oghuric[edit]

Azerbaijani dialects share paradigms of verbs in some tenses with the Chuvash language,[39] on which linguists also rely in the study and reconstruction of the Khazar language.[39]

Phonology[edit]

Phonotactics[edit]

Azerbaijani phonotactics is similar to that of other Oghuz Turkic languages, except:

- Trimoraic syllables with long vowels are permissible.

- There is an ongoing metathesis of neighboring consonants in a word.[55] Speakers tend to reorder consonants in the order of decreasing sonority and back-to-front (for example, iləri becomes irəli, köprü becomes körpü, topraq becomes torpaq). Some of the metatheses are so common in the educated speech that they are reflected in orthography (all the above examples are like that). This phenomenon is more common in rural dialects but observed even in educated young urban speakers, but noticeably absent from some Southern dialects.

- Intramorpheme /q/ becomes /x/.

Consonants[edit]

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ŋ) | |||||||||||

| Stop/Affricate | p | b | t | d | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | c | ɟ | (k) | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | x | ɣ | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||||||||||

| Flap | ɾ |

- The sound [k] is used only in loanwords; the historical unpalatalized [k] became voiced to [ɡ].

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are realised as [t͡s] and [d͡z] respectively in the areas around Tabriz and to the west, south and southwest of Tabriz (including Kirkuk in Iraq); in the Nakhchivan and Ayrum dialects, in Cəbrayil and some Caspian coastal dialects;.[56]

- Sounds /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ may also be recognized as separate phonemic sounds in the Tabrizi and southern dialects.[57]

- In most dialects of Azerbaijani, /c/ is realized as [ç] when it is found in the syllabic coda or is preceded by a voiceless consonant (as in çörək [t͡ʃøˈɾæç] – «bread»; səksən [sæçˈsæn] – «eighty»).

- /w/ exists in the Kirkuk dialect as an allophone of /v/ in Arabic loanwords.

- In the Baku subdialect, /ov/ may be realised as [oʊ], and /ev/ and /øv/ as [øy], e.g. qovurma /ɡovurˈmɑ/ → *qourma [ɡoʊrˈmɑ], sevda /sevˈdɑ/ → *söüda [søyˈdɑ], dövran /døvˈrɑn/ → *döüran [døyˈrɑn], as well as with surnames ending in -ov or -ev (borrowed from Russian).[58]

- In colloquial speech, /x/ is usually pronounced as [χ]

Dialect consonants[edit]

- Dz dz—[d͡z]

- Ć ć—[t͡s]

- Ŋ ŋ—[ŋ]

- Q̇ q̇—[ɢ]

- Ð ð—[ð][citation needed]

- W w—[w, ɥ]

Examples:

- [d͡z]—dzan [d͡zɑn̪]

- [t͡s]—ćay [t͡sɑj]

- [ŋ]—ataŋın [ʔɑt̪ɑŋən̪]

- [ɢ]—q̇ar [ɢɑɾ]

- [ð]—əðəli [ʔæðæl̪ɪ]

- [w]—dowşan [d̪ɔːwʃɑn̪]

- [ɥ]—töwlə [t̪œːɥl̪æ]

Vowels[edit]

The vowels of the Azerbaijani are, in alphabetical order,[59][60] a /ɑ/, e /e/, ə /æ/, ı /ɯ/, i /i/, o /o/, ö /ø/, u /u/, ü /y/. There are no diphthongs in standard Azerbaijani when two vowels come together; when that occurs in some Arabic loanwords, diphthong is removed by either syllable separation at V.V boundary or fixing the pair as VC/CV pair, depending on the word.

South Azerbaijani vowel chart, from Mokari & Werner (2016:509)

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| Close | i | y | ɯ | u |

| Mid | e | ø | o | |

| Open | æ | ɑ |

|

This section needs expansion with: complete vowel allophonies. You can help by adding to it. (December 2018) |

The typical phonetic quality of South Azerbaijani vowels is as follows:

- /i, u, æ/ are close to cardinal [i, u, a].[61]

- The F1 and F2 formant frequencies overlap for /œ/ and /ɯ/. Their acoustic quality is more or less close-mid central [ɵ, ɘ]. The main role in the distinction of two vowels is played by the different F3 frequencies in audition,[62] and rounding in articulation. Phonologically, however, they are more distinct: /œ/ is phonologically a mid front rounded vowel, the front counterpart of /o/ and the rounded counterpart of /e/. /ɯ/ is phonologically a close back unrounded vowel, the back counterpart of /i/ and the unrounded counterpart of /u/.

- The other mid vowels /e, o/ are closer to close-mid [e, o] than open-mid [ɛ, ɔ].[61]

- /ɑ/ is phonetically near-open back [ɑ̝].[61]

Writing systems[edit]

Before 1929, Azerbaijani was written only in the Perso-Arabic alphabet, an impure abjad that does not represent all vowels (without diacritical marks). In Iran, Azerbaijani is still written in a modified form of the Persian alphabet that the newspaper Varlıq (started in 1979 by Javad Heyat) set the standard for.[63] Varlıq (وارلیق) wrote in a reformed Perso-Arabic alphabet that represents all vowels with the exception of «Ə» as elucidated further by the newspaper’s editor in a language guide written for Iranian Azerbaijanis titled «Türk dili yazı quralları» published in 2001.[63] Varlıq’s standard of writing is today canonized by the official Persian–Azeri Turkish dictionary in Iran titled «lugat name-ye Turki-ye Azarbayjani«.[64]

In 1929–1938 a Latin alphabet was in use for North Azerbaijani (although it was different from the one used now), from 1938 to 1991 the Cyrillic script was used, and in 1991 the current Latin alphabet was introduced, although the transition to it has been rather slow.[65] For instance, until an Aliyev decree on the matter in 2001,[66] newspapers would routinely write headlines in the Latin script, leaving the stories in Cyrillic.[67] The transition has also resulted in some misrendering of İ as Ì.[68][69] In Dagestan, Azerbaijani is still written in Cyrillic script.

The Azerbaijani Latin alphabet is based on the Turkish Latin alphabet, which in turn was based on former Azerbaijani Latin alphabet because of their linguistic connections and mutual intelligibility. The letters Әə, Xx, and Qq are available only in Azerbaijani for sounds which do not exist as separate phonemes in Turkish.

| Old Latin (1929–1938 version; no longer in use; replaced by 1991 version) |

Official Latin (Azerbaijan since 1991) |

Cyrillic (1958 version, still official in Dagestan) |

Perso-Arabic (Iran; Azerbaijan until 1929) |

IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | А а | آ / ـا | /ɑ/ | |

| B в | B b | Б б | ب | /b/ |

| Ç ç | C c | Ҹ ҹ | ج | /dʒ/ |

| C c | Ç ç | Ч ч | چ | /tʃ/ |

| D d | Д д | د | /d/ | |

| E e | Е е | ئ | /e/ | |

| Ə ə | Ә ә | ا / َ / ە | /æ/ | |

| F f | Ф ф | ف | /f/ | |

| G g | Ҝ ҝ | گ | /ɟ/ | |

| Ƣ ƣ | Ğ ğ | Ғ ғ | غ | /ɣ/ |

| H h | Һ һ | ح / ه | /h/ | |

| X x | Х х | خ | /x/ | |

| Ь ь | I ı | Ы ы | ؽ | /ɯ/ |

| I i | İ i | И и | ی | /i/ |

| Ƶ ƶ | J j | Ж ж | ژ | /ʒ/ |

| K k | К к | ک | /k/, /c/ | |

| Q q | Г г | ق | /ɡ/ | |

| L l | Л л | ل | /l/ | |

| M m | М м | م | /m/ | |

| N n | Н н | ن | /n/ | |

| Ꞑ ꞑ[70] | — | — | ݣ / نگ | /ŋ/ |

| O o | О о | وْ | /o/ | |

| Ɵ ɵ | Ö ö | Ө ө | ؤ | /ø/ |

| P p | П п | پ | /p/ | |

| R r | Р р | ر | /r/ | |

| S s | С с | ث / س / ص | /s/ | |

| Ş ş | Ш ш | ش | /ʃ/ | |

| T t | Т т | ت / ط | /t/ | |

| U u | У у | ۇ | /u/ | |

| Y y | Ü ü | Ү ү | ۆ | /y/ |

| V v | В в | و | /v/ | |

| J j | Y y | Ј ј | ی | /j/ |

| Z z | З з | ذ / ز / ض / ظ | /z/ | |

| — | ʼ | ع | /ʔ/ |

Northern Azerbaijani, unlike Turkish, respells foreign names to conform with Latin Azerbaijani spelling, e.g. Bush is spelled Buş and Schröder becomes Şröder. Hyphenation across lines directly corresponds to spoken syllables, except for geminated consonants which are hyphenated as two separate consonants as morphonology considers them two separate consonants back to back but enunciated in the onset of the latter syllable as a single long consonant, as in other Turkic languages.[citation needed]

Vocabulary[edit]

Interjections[edit]

Some samples include:

Secular:

- Of («Ugh!»)

- Tez Ol («Be quick!»)

- Tez olun qızlar mədrəsəyə («Be quick girls, to school!», a slogan for an education campaign in Azerbaijan)

Invoking deity:

- implicitly:

- Aman («Mercy»)

- Çox şükür («Much thanks»)

- explicitly:

- Allah Allah (pronounced as Allahallah) («Goodness gracious»)

- Hay Allah; Vallah «By God [I swear it]».

- Çox şükür allahım («Much thanks my god»)

Formal and informal[edit]

Azerbaijani has informal and formal ways of saying things. This is because there is a strong tu-vous distinction in Turkic languages like Azerbaijani and Turkish (as well as in many other languages). The informal «you» is used when talking to close friends, relatives, animals or children. The formal «you» is used when talking to someone who is older than you or someone for whom you would like to show respect (a professor, for example).

As in many Turkic languages, personal pronouns can be omitted, and they are only added for emphasis. Since 1992 North Azerbaijani has used a phonetic writing system, so pronunciation is easy: most words are pronounced exactly as they are spelled.

| Category | English | North Azerbaijani (in Latin script) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic expressions | yes | hə /hæ/ (informal), bəli (formal) |

| no | yox /jox/ (informal), xeyr (formal) | |

| hello | salam /sɑlɑm/ | |

| goodbye | sağ ol /ˈsɑɣ ol/ | |

| sağ olun /ˈsɑɣ olun/ (formal) | ||

| good morning | sabahınız xeyir /sɑbɑhɯ(nɯ)z xejiɾ/ | |

| good afternoon | günortanız xeyir /ɟynoɾt(ɑn)ɯz xejiɾ/ | |

| good evening | axşamın xeyir /ɑxʃɑmɯn xejiɾ/ | |

| axşamınız xeyir /ɑxʃɑmɯ(nɯ)z xejiɾ/ | ||

| Colours | black | qara /ɡɑɾɑ/ |

| blue | göy /ɟøj/ | |

| brown | qəhvəyi / qonur | |

| grey | boz /boz/ | |

| green | yaşıl /jaʃɯl/ | |

| orange | narıncı /nɑɾɯnd͡ʒɯ/ | |

| pink | çəhrayı

/t͡ʃæhɾɑjɯ/ |

|

| purple | bənövşəyi

/bænøvʃæji/ |

|

| red | qırmızı /ɡɯɾmɯzɯ/ | |

| white | ağ /ɑɣ/ | |

| yellow | sarı /sɑɾɯ/ |

Numbers[edit]

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 0 | sıfır /ˈsɯfɯɾ/ |

| 1 | bir /biɾ/ |

| 2 | iki /ici/ |

| 3 | üç /yt͡ʃ/ |

| 4 | dörd /døɾd/ |

| 5 | beş /beʃ/ |

| 6 | altı /ɑltɯ/ |

| 7 | yeddi /jed:i/ |

| 8 | səkkiz /sæc:iz/ |

| 9 | doqquz /doɡ:uz/ |

| 10 | on /on/ |

For numbers 11–19, the numbers literally mean «10 one, 10 two» and so on.

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 20 | iyirmi /ijiɾmi/ [d] |

| 30 | otuz /otuz/ |

| 40 | qırx /ɡɯɾx/ |

| 50 | əlli /ælli/ |

Greater numbers are constructed by combining in tens and thousands larger to smaller in the same way, without using a conjunction in between.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Former Cyrillic spelling used in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic.

- ^

- The written language of the Iraqi Turkmen is based on Istanbul Turkish using the modern Turkish alphabet.

- Professor Christiane Bulut has argued that publications from Azerbaijan often use expressions such as «Azerbaijani (dialects) of Iraq» or «South Azerbaijani» to describe Iraqi Turkmen dialects «with political implications»; however, in Turcological literature, closely related dialects in Turkey and Iraq are generally referred to as «eastern Anatolian» or «Iraq-Turkic/-Turkman» dialects, respectively.[1]

- ^ These latter two are more often used in Iranian Azerbaijan.

- ^ Since Azerbaijan’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, northern Azerbaijani uses the Latin alphabet. Iranian Azerbaijani, on the other hand, has always used and continues to use Arabic script.[41]

- ^ /iɾmi/ is also found in standard speech.

References[edit]

- ^ Bulut, Christiane (2018b), «The Turkic varieties of Iran», in Haig, Geoffrey; Khan, Geoffrey (eds.), The Languages and Linguistics of Western Asia: An Areal Perspective, Walter de Gruyter, p. 398, ISBN 978-3-11-042168-2

- ^ Azerbaijani language at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ a b c d e f g «Azerbaijani, North». Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f «Azerbaijani, South». Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Nemat Rahmati, Korkut Buğday: Aserbaidschanisch Lehrbuch. Unter Berücksichtigung des Nord- und Südaserbaidschanischen. = Aserbaidschanisch. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-03840-3.

- ^ Rahmati, Nemat (1998). Aserbaidschanisch Lehrbuch : unter Berücksichtigung des Nord- und Südaserbaidschanischen. Korkut M. Buğday. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-03840-3. OCLC 40415729.

- ^ «Türk dili, yoxsa azərbaycan dili? (Turkish language or Azerbaijani language?)». BBC (in Azerbaijani). 9 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b «AZERBAIJAN». Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2-3. 1987. pp. 205–257.

- ^ «From the Harvard Art Museums’ collections Illustrated manuscript of the Hadiqat al-Su’ada (Garden of the Blessed) by Fuzuli». harvardartmuseums.org.

- ^ «The Turkic Languages», Osman Fikri Sertkaya (2005) in Turks – A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600-1600, London ISBN 978-1-90397-356-1

- ^ Wright, Sue; Kelly, Helen (1998). Ethnicity in Eastern Europe: Questions of Migration, Language Rights and Education. Multilingual Matters Ltd. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-85359-243-0.

- ^ Bratt Paulston, Christina; Peckham, Donald (1 October 1998). Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe. Multilingual Matters Ltd. pp. 98–115. ISBN 978-1-85359-416-8.

- ^ L. Johanson, «AZERBAIJAN ix. Iranian Elements in Azeri Turkish» in Encyclopædia Iranica [1].

- ^ John R. Perry, «Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic» in Csató et al. (2005) Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, p. 97: «It is generally understood that the bulk of the Arabic vocabulary in the central, contiguous Iranic, Turkic and Indic languages was originally borrowed into literary Persian between the ninth and thirteenth centuries CE…»

- ^ electricpulp.com. «AZERBAIJAN ix. Iranian Elements in Azeri Turki – Encyclopaedia Iranica».

- ^ Tonoyan, Artyom (2019). «On the Caucasian Persian (Tat) Lexical Substratum in the Baku Dialect of Azerbaijani. Preliminary Notes». Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 169 (2): 368 (note 4). doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.169.2.0367.

- ^ Karpat, K. (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. Oxford University Press. p. 295.

- ^ «Alphabet Changes in Azerbaijan in the 20th Century». Azerbaijan International. Spring 2000. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Language Commission Suggested to Be Established in National Assembly. Day.az. 25 January 2011.

- ^ Johanson, L. (6 April 2010). Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Öztopcu, Kurtulus. «Azeri / Azerbaijani». American Association of Teachers of Turkic Languages. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Iranica. Azeri Literature in Iran The 15th century saw the beginning of a more important period in the history of the Azeri Turkish literature. The position of the literary language was reinforced under the Qarāqoyunlu (r. 1400-68), who had their capital in Tabriz. Jahānšāh (r. 1438-68) himself wrote lyrical poems in Turkish using the pen name of «Ḥaqiqi».

- ^ V. Minorsky. Jihān-Shāh Qara-Qoyunlu and His Poetry (Turkmenica, 9). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. — Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies, 1954. — V.16, p . 272, 283: «It is somewhat astonishing that a sturdy Turkman like Jihan-shah should have been so restricted in his ways of expression. Altogether the language of the poems belongs to the group of the southern Turkman dialects which go by the name of Azarbayjan Turkish.»; «As yet nothing seems to have been published on the Br. Mus. manuscript Or. 9493, which contains the bilingual collection of poems of Haqiqi, i.e. of the Qara-qoyunlu sultan Jihan-shah (A.D. 1438—1467).»

- ^ «AZERBAIJAN x. Azeri Literature [1988]». Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_eiro_com_11092. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ a b G. Doerfer, «Azeri Turkish», Encyclopaedia Iranica, viii, Online Edition, p. 246.

- ^ Mark R.V. Southern. Mark R V Southern (2005) Contagious couplings: transmission of expressives in Yiddish echo phrases, Praeger, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-31306-844-7

- ^ «Greetings to Heydar Baba». umich.edu. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ Pieter Muysken, «Introduction: Conceptual and methodological issues in areal linguistics», in Pieter Muysken (2008) From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics, p. 30-31 ISBN 978-90-272-3100-0 [2]

- ^ Viacheslav A. Chirikba, «The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund» in Muysken, p. 74

- ^ Lenore A. Grenoble (2003) Language Policy in the Soviet Union, p. 131 ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3 [3]

- ^ Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie. Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. – Elsevier, 2009. – С. 110–113. – ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7. An Azerbaijanian koine´ functioned for centuries as a lingua franca, serving trade and intergroup communication all over Persia, in the Caucasus region and in southeastern Dagestan. Its transregional validity continued at least until the 18th century.

- ^ [4] Nikolai Trubetzkoy (2000) Nasledie Chingiskhana, p. 478 Agraf, Moscow ISBN 978-5-77840-082-5 (Russian)

- ^ J. N. Postgate (2007) Languages of Iraq, p. 164, British School of Archaeology in Iraq ISBN 978-0-903472-21-0

- ^ Homa Katouzian (2003) Iranian history and politics, Routledge, pg 128: «Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability»

- ^ «Date of the Official Instruction of Oriental Languages in Russia» by N.I.Veselovsky. 1880. in W.W. Grigorieff ed. (1880) Proceedings of the Third Session of the International Congress of Orientalists, Saint Petersburg (Russian)

- ^ Salehi, Mohammad; Neysani, Aydin (2017). «Receptive intelligibility of Turkish to Iranian-Azerbaijani speakers». Cogent Education. 4 (1): 3. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2017.1326653. S2CID 121180361.

Northern and Southern Azerbaijani are considered distinct languages by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (…)

- ^ A study of Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, author Svante E.Cornell, 2001, page 22 (ISBN 978-0-203-98887-9)

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin (2019). «Linguistics». In Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin (eds.). Modern Azeric. Glottolog 4.1. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3554959. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ a b c «Khazar language». Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian).

- ^ Schönig (1998), pg. 248.

- ^ , Mokari & Werner 2017, p. 207.

- ^ «Azeris». World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ «Iran-Azeris». Library of Congress Country Studies. December 1987. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ International Business Publications (2005). Iran: Country Study Guide. International Business Publications. ISBN 978-0-7397-1476-8.

- ^ «The World Factbook». Cia.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Yelda, Rami (2012). A Persian Odyssey: Iran Revisited. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4772-0291-3., p. 33

- ^ Mafinezam, Alidad; Mehrabi, Aria (2008). Iran and Its Place Among Nations. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99926-1., p. 57

- ^ Azerbaijani (Azeri), UNESCO

- ^ Sağın-Şimşek Ç, König W. Receptive multilingualism and language understanding: Intelligibility of Azerbaijani to Turkish speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism. 2012;16(3):315-331. doi:10.1177/1367006911426449

- ^ Salehi, Mohammad; Neysani, Aydin (2017). «Receptive intelligibility of Turkish to Iranian-Azerbaijani speakers». Cogent Education. 4 (1): 10. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2017.1326653. S2CID 121180361.

- ^ Shiraliyev M. Fundamentals of Azerbaijan dialectology. Baku, 2008. p.76

- ^ Kara M. Turkmen Grammar. Ankara, 2005. p.231

- ^ Berdiev R.; S. Kurenov; K. Shamuradov; S. Arazkuliyev (1970). Essay on the Dialects of the Turkmen Language. Ashgabat. p. 116.

- ^ «Swadesh list, compare the Azerbaijani language and the Turkmen language». Lingiustics.

- ^ Kök 2016, pp. 406–30.

- ^ Persian Studies in North America by Mohammad Ali Jazayeri

- ^ Mokari & Werner (2017), p. 209.

- ^ Shiraliyev, Mammadagha. The Baku Dialect. Azerbaijan SSR Academy of Sciences Publ.: Baku, 1957; p. 41

- ^ Householder and Lotfi. Basic Course in Azerbaijani. 1965.

- ^ Shiralyeva (1971)

- ^ a b c Mokari & Werner (2016), p. 509.

- ^ Mokari & Werner 2016, p. 514.

- ^ a b Azeri Arabic Turk standard of writing; authored by Dr. Javad Heyat; 2001 http://www.azeri.org/Azeri/az_arabic/azturk_standard.pdf

- ^ Ameli, Seyed Hassan (2021). لغتنامه ترکی آذربایجانی: حروف آ (جلد ۱ (in Persian and Azerbaijani). Mohaghegh Ardabili. ISBN 978-600-344-624-3.

- ^ Dooley, Ian (6 October 2017). «New Nation, New Alphabet: Azerbaijani Children’s Books in the 1990s». Cotsen Children’s Library (in English and Azerbaijani). Princeton University WordPress Service. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

Through the 1990s and early 2000s Cyrillic script was still in use for newspapers, shops, and restaurants. Only in 2001 did then president Heydar Aliyev declare «a mandatory shift from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet» … The transition has progressed slowly.

- ^ Peuch, Jean-Christophe (1 August 2001). «Azerbaijan: Cyrillic Alphabet Replaced By Latin One». Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Monakhov, Yola (31 July 2001). «Azerbaijan Changes Its Alphabet». Getty Images. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Khomeini, Ruhollah (15 March 1997). Translated by Dilənçi, Piruz. «Ayətulla Homeynì: «… Məscìd ìlə mədrəsədən zar oldum»«. Müxalifət (in Azerbaijani and Persian). Baku. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Yahya, Harun. «Global Impact of the Works of Harun Yahya V2». Secret Beyond Matter. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Excluded from the alphabet in 1938

Bibliography[edit]

- Brown, Keith, ed. (24 November 2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-054784-8.

- Kök, Ali (2016). «Modern Oğuz Türkçesi Diyalektlerinde Göçüşme» [Migration in Modern Oghuz Turkish Dialects]. 21. Yüzyılda Eğitim Ve Toplum Eğitim Bilimleri Ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi (in Turkish). 5 (15). ISSN 2147-0928.

- Mokari, Payam Ghaffarvand; Werner, Stefan (2016), Dziubalska-Kolaczyk, Katarzyna (ed.), «An acoustic description of spectral and temporal characteristics of Azerbaijani vowels», Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 52 (3), doi:10.1515/psicl-2016-0019, S2CID 151826061

- Mokari, Payam Ghaffarvand; Werner, Stefan (2017). «Azerbaijani». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 47 (2): 207. doi:10.1017/S0025100317000184. S2CID 232347049.

- Sinor, Denis (1969). Inner Asia. History-Civilization-Languages. A syllabus. Bloomington. pp. 71–96. ISBN 978-0-87750-081-0.

External links[edit]

- A blog on Azerbaijani language resources and translations

- (in Russian) A blog about the Azerbaijani language and lessons

- azeri.org, Azerbaijani literature and English translations.

- Online bidirectional Azerbaijani-English Dictionary [broken as of 2022]

- Learn Azerbaijani at learn101.org.

- Pre-Islamic roots

- Azerbaijan-Turkish language in Iran by Ahmad Kasravi.

- including sound file.

- Azerbaijani<>Turkish dictionary (Pamukkale University)

- Azerbaijan Language with Audio

- Azerbaijani thematic vocabulary

- AzConvert, an open source Azerbaijani transliteration program.

- Azerbaijani Alphabet and Language in Transition, the entire issue of Azerbaijan International, Spring 2000 (8.1) at azer.com.

- Editorial

- Chart: Four Alphabet Changes in Azerbaijan in the 20th century

- Chart: Changes in the Four Azerbaijan Alphabet Sequence in the 20th century

- Baku’s Institute of Manuscripts: Early Alphabets in Azerbaijan

«Azeri language» redirects here. For the extinct Iranian language, see Old Azeri.

| Azerbaijani | |

|---|---|

| Azeri | |

| Azərbaycan dili, آذربایجان دیلی, Азәрбајҹан дили[note 1] | |

Azerbaijani in Perso-Arabic Nastaliq (Iran), Latin (Azerbaijan), and Cyrillic (Russia). |

|

| Pronunciation | [ɑːzæɾbɑjˈdʒɑn diˈli] |

| Native to |

|

| Region | Iranian Azerbaijan, South Caucasus |

| Ethnicity | Azerbaijanis |

|

Native speakers |

24 million (2022)[2] |

|

Language family |

Turkic

|

|

Early form |

Ajem-Turkic |

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

|

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

Azerbaijan Dagestan (Russia) Organization of Turkic States |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | az |

| ISO 639-2 | aze |

| ISO 639-3 | aze – inclusive codeIndividual codes: azj – North Azerbaijaniazb – South Azerbaijanislq – Salchuqqxq – Qashqai |

| Glottolog | mode1262 |

| Linguasphere | part of 44-AAB-a |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Azerbaijani () or Azeri (), also referred to as Azeri Turkic, Azeri Turkish, or simply Turki/Torki,[b] is a Turkic language from the Oghuz sub-branch spoken primarily by the Azerbaijani people, who live mainly in the Republic of Azerbaijan where the North Azerbaijani variety is spoken, and in the Azerbaijan region of Iran, where the South Azerbaijani variety is spoken.[5][6] Although there is a very high degree of mutual intelligibility between both forms of Azerbaijani, there are significant differences in phonology, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and sources of loanwords.

North Azerbaijani has official status in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Dagestan (a federal subject of Russia), but South Azerbaijani does not have official status in Iran, where the majority of Azerbaijani people live. It is also spoken to lesser varying degrees in Azerbaijani communities of Georgia and Turkey and by diaspora communities, primarily in Europe and North America.

Both Azerbaijani varieties are members of the Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. The standardized form of North Azerbaijani (spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Russia) is based on the Shirvani dialect, while South Azerbaijani uses the Tabrizi dialect as its prestige variety. Since the Republic of Azerbaijan’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Northern Azerbaijani uses the Latin script. South Azerbaijani, on the other hand, has always used and continues to use the Perso-Arabic script. Azerbaijani language is closely related to Gagauz, Qashqai, Crimean Tatar, Turkish, and Turkmen, sharing varying degrees of mutual intelligibility with each of those languages.

Etymology and background[edit]

Historically the language was referred by its native speakers as türk dili or türkcə[7], meaning either «Turkish» or «Turkic». After the establishment of the Azerbaijan SSR,[8] on the order of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the «name of the formal language» of the Azerbaijan SSR was changed from «Turkish» to «Azerbaijani».[8]

History and evolution[edit]

Garden of Pleasures by Fuzûlî in Azerbaijani from 16th century.[9]

Azerbaijani evolved from the Eastern branch of Oghuz Turkic («Western Turkic»)[10] which spread to the Caucasus, in Eastern Europe,[11][12] and northern Iran, in Western Asia, during the medieval Turkic migrations.[13] Persian and Arabic influenced the language, but Arabic words were mainly transmitted through the intermediary of literary Persian.[14] Azerbaijani is, perhaps after Uzbek, the Turkic language upon which Persian and other Iranian languages have exerted the strongest impact—mainly in phonology, syntax, and vocabulary, less in morphology.[15]

The Turkic language of Azerbaijan gradually supplanted the Iranian languages in what is now northwestern Iran, and a variety of languages of the Caucasus and Iranian languages spoken in the Caucasus, particularly Udi and Old Azeri. By the beginning of the 16th century, it had become the dominant language of the region. It was a spoken language in the court of the Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars.

The historical development of Azerbaijani can be divided into two major periods: early (c. 14th to 18th century) and modern (18th century to present). Early Azerbaijani differs from its descendant in that it contained a much larger number of Persian and Arabic loanwords, phrases and syntactic elements. Early writings in Azerbaijani also demonstrate linguistic interchangeability between Oghuz and Kypchak elements in many aspects (such as pronouns, case endings, participles, etc.). As Azerbaijani gradually moved from being merely a language of epic and lyric poetry to being also a language of journalism and scientific research, its literary version has become more or less unified and simplified with the loss of many archaic Turkic elements, stilted Iranisms and Ottomanisms, and other words, expressions, and rules that failed to gain popularity among the Azerbaijani masses.

The Russian annexation of Iran’s territories in the Caucasus through the Russo-Iranian wars of 1804–1813 and 1826-1828 split the language community across two states. Afterwards, the Tsarist administration encouraged the spread of Azerbaijani in eastern Transcaucasia as a replacement for Persian spoken by the upper classes, and as a measure against Persian influence in the region.[16][17]

Between c. 1900 and 1930, there were several competing approaches to the unification of the national language in what is now the Azerbaijan Republic, popularized by scholars such as Hasan bey Zardabi and Mammad agha Shahtakhtinski. Despite major differences, they all aimed primarily at making it easy for semi-literate masses to read and understand literature. They all criticized the overuse of Persian, Arabic, and European elements in both colloquial and literary language and called for a simpler and more popular style.

The Soviet Union promoted the development of the language but set it back considerably with two successive script changes[18] – from the Persian to Latin and then to the Cyrillic script – while Iranian Azerbaijanis continued to use the Persian script as they always had. Despite the wide use of Azerbaijani in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, it became the official language of Azerbaijan only in 1956.[19] After independence, the Republic of Azerbaijan decided to switch back to a modified Latin script.

Azerbaijani literature[edit]

The development of Azerbaijani literature is closely associated with Anatolian Turkish, written in Perso-Arabic script. Examples of its detachment date to the 14th century or earlier.[20][21] Kadi Burhan al-Din, Hesenoghlu, and Imadaddin Nasimi helped to establish Azerbaiijani as a literary language in the 14th century through poetry and other works.[21] The ruler of the Qara Qoyunlu state, Jahanshah, wrote poems in Azerbaijani language with the nickname «Haqiqi».[22][23] Sultan Yaqub, the ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu state, wrote poems in the Azerbaijani language.[24] The ruler and poet Ismail I wrote under the pen name Khatā’ī (which means «sinner» in Persian) during the fifteenth century.[25][26] During the 16th century, the poet, writer and thinker Fuzûlî wrote mainly in Azerbaijani but also translated his poems into Arabic and Persian.[25]

Starting in the 1830s, several newspapers were published in Iran during the reign of the Azerbaijani speaking Qajar dynasty but it is unknown whether any of these newspapers were written in Azerbaijani. In 1875, Akinchi (Əkinçi / اکينچی) («The Ploughman») became the first Azerbaijani newspaper to be published in the Russian Empire. It was started by Hasan bey Zardabi, a journalist and education advocate.[21]

Following the rule of the Qajar dynasty, Iran was ruled by Reza Shah who banned the publication of texts in Azerbaijani.[citation needed] Modern literature in the Republic of Azerbaijan is based on the Shirvani dialect mainly, while in Iranian Azerbaijan, it is based on the Tabrizi dialect.

Mohammad-Hossein Shahriar is an important figure in Azerbaijani poetry. His most important work is Heydar Babaya Salam and it is considered to be a pinnacle of Azerbaijani literature and gained popularity in the Turkic-speaking world. It was translated into more than 30 languages.[27]

In the mid-19th century, Azerbaijani literature was taught at schools in Baku, Ganja, Shaki, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. Since 1845, it has also been taught in the Saint Petersburg State University in Russia. In 2018, Azerbaijani language and literature programs are offered in the United States at several universities, including Indiana University, UCLA, and University of Texas at Austin.[21] The vast majority, if not all Azerbaijani language courses teach North Azerbaijani written in the Latin script and not South Azerbaijani written in the Perso-Arabic script.

Modern literature in the Republic of Azerbaijan is primarily based on the Shirvani dialect, while in the Iranian Azerbaijan region (historic Azerbaijan) it is based on the Tabrizi one.

Lingua franca[edit]

Azerbaijani served as a lingua franca throughout most parts of Transcaucasia except the Black Sea coast, in southern Dagestan,[28][29][30] the Eastern Anatolia Region and all over Iran [31] from the 16th to the early 20th centuries,[32][33] alongside cultural, administrative, court literature, and most importantly official language (along with Azerbaijani) of all these regions, namely Persian.[34] From the early 16th century up to the course of the 19th century, these regions and territories were all ruled by the Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars until the cession of Transcaucasia proper and Dagestan by Qajar Iran to the Russian Empire per the 1813 Treaty of Gulistan and the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay. Per the 1829 Caucasus School Statute, Azerbaijani was to be taught in all district schools of Ganja, Shusha, Nukha (present-day Shaki), Shamakhi, Quba, Baku, Derbent, Yerevan, Nakhchivan, Akhaltsikhe, and Lankaran. Beginning in 1834, it was introduced as a language of study in Kutaisi instead of Armenian. In 1853, Azerbaijani became a compulsory language for students of all backgrounds in all of Transcaucasia with the exception of the Tiflis Governorate.[35]

Dialects of Azerbaijani[edit]

Reza Shah and Kemal Atatürk in Turkey.

Azerbaijani is one of the Oghuz languages within the Turkic language family. Ethnologue classifies North Azerbaijani (spoken mainly in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Russia) and South Azerbaijani (spoken in Iran, Iraq, and Syria) as separate languages with «significant differences in phonology, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and loanwords.»[3] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) also considers Northern and Southern Azerbaijani to be distinct languages.[36]

Svante Cornell wrote in his 2001 book Small Nations and Great Powers that «it is certain that Russian and Iranian words (sic), respectively, have entered the vocabulary on either side of the Araxes river, but this has not occurred to an extent that it could pose difficulties for communication».[37] There are numerous dialects, with 21 North Azerbaijani dialects and 11 South Azerbaijani dialects identified by Ethnologue.[3][4]

Four varieties have been accorded ISO 639-3 language codes: North Azerbaijani, South Azerbaijani, Salchuq, and Qashqai. The Glottolog 4.1 database classifies North Azerbaijani, with 20 dialects, and South Azerbaijani, with 13 dialects, under the Modern Azeric family, a branch of Central Oghuz.[38]

In the northern dialects of the Azerbaijani language, linguists find traces of the influence of the Khazar language.[39]

According to the Linguasphere Observatory, all Oghuz languages form part of a single «outer language» of which North and South Azerbaijani are «inner languages».[citation needed]

North Azerbaijani[edit]

Azerbaijani-language road sign.

North Azerbaijani,[3] or Northern Azerbaijani, is the official language of the Republic of Azerbaijan. It is closely related to modern-day Istanbul Turkish, the official language of Turkey. It is also spoken in southern Dagestan, along the Caspian coast in the southern Caucasus Mountains and in scattered regions throughout Central Asia. As of 2011, there are some 9.23 million speakers of North Azerbaijani including 4 million monolingual speakers (many North Azerbaijani speakers also speak Russian, as is common throughout former USSR countries).[3]

The Shirvan dialect as spoken in Baku is the basis of standard Azerbaijani. Since 1992, it has been officially written with a Latin script in the Republic of Azerbaijan, but the older Cyrillic script was still widely used in the late 1990s.[40]

Ethnologue lists 21 North Azerbaijani dialects: Quba, Derbend, Baku, Shamakhi, Salyan, Lankaran, Qazakh, Airym, Borcala, Terekeme, Qyzylbash, Nukha, Zaqatala (Mugaly), Qabala, Yerevan, Nakhchivan, Ordubad, Ganja, Shusha (Karabakh), Karapapak.[3]

South Azerbaijani[edit]

South Azerbaijani,[4] or Iranian Azerbaijani,[c] is widely spoken in Iranian Azerbaijan and, to a lesser extent, in neighboring regions of Turkey and Iraq, with smaller communities in Syria. In Iran, the Persian word for Azerbaijani is borrowed as Torki «Turkic».[4] In Iran, it is spoken mainly in East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil and Zanjan. It is also widely spoken in Tehran and across Tehran Province, as Azerbaijanis form by far the largest minority in the city and the wider province,[42] comprising about 1⁄6[43][44] of its total population. The CIA World Factbook reports that in 2010, the percentage of Iranian Azerbaijani speakers at around 16 percent of the Iranian population, or approximately 13 million people worldwide,[45] and ethnic Azeris form by far the second largest ethnic group of Iran, thus making the language also the second most spoken language in the nation. Ethnologue reports 10.9 million Iranian Azerbaijani in Iran in 2016 and 13,823,350 worldwide.[4]

Dialects of South Azerbaijani include: Aynallu (Inallu, Inanlu), Qarapapaq, Tabrizi, Qashqai, Afshari (Afsar, Afshar), Shahsavani (Shahseven), Muqaddam, Baharlu (Kamesh), Nafar, Qaragözlü, Pishaqchi (Bıçaqçı), Bayatlu, Qajar, Marandli.[4]

Comparison with other Turkic languages[edit]

Azerbaijani and Turkish[edit]

North and South Azerbaijani speakers and Turkish speakers can communicate with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Turkish soap operas are very popular with Azeris in both Iran and Azerbaijan. Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran (who spoke South Azerbaijani) met with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of Turkey (who spoke Turkish) in 1934; the two were filmed speaking their respective language to each other and communicated effectively.[46][47]

Speakers of Turkish and Azerbaijani can, to an extent, communicate with each other as both languages have substantial variation and are to a degree mutually intelligible, though it is easier for a speaker of Azerbaijani to understand Turkish than the other way around.[48]

In a 2011 study, 30 Turkish participants were tested to determine how well they understood written and spoken Azerbaijani. It was found that even though Turkish and Azerbaijani are typologically similar languages, on the part of Turkish speakers the intelligibility is not as high as is estimated.[49] In a 2017 study, Iranian Azerbaijanis scored in average 56% of receptive intelligibility in spoken language of Turkish.[50]

Azerbaijani exhibits a similar stress pattern to Turkish but simpler in some respects. Azerbaijani is a strongly stressed and partially stress-timed language, unlike Turkish which is weakly stressed and syllable-timed.

Below are some words with different pronunciations in Azerbaijani and Turkish but have the same meaning in both languages:

| Azerbaijani | Turkish | English |

|---|---|---|

| ayaqqabı/başmaq | ayakkabı | shoes |

| ayaq | ayak | foot |

| kitab | kitap | book |

| qan | kan | blood |

| qaz | kaz | goose |

| qaş | kaş | eyebrow |

| qar | kar | snow |

| daş | taş | stone |

Azerbaijani and Turkmen[edit]

The 1st person personal pronoun is mən in Azerbaijani just as men in Turkmen, whereas it is ben in Turkish. The same is true for demonstrative pronouns bu, where sound b is replaced with sound m. For example: bunun>munun/mının, muna/mına, munu/munı, munda/mında, mundan/mından.[51] This is observed in the Turkmen literary language as well, where the demonstrative pronoun bu undergoes some changes just as in: munuñ, munı, muña, munda, mundan, munça.[52] b>m replacement is encountered in many dialects of the Turkmen language and may be observed in such words as: boyun>moyın in Yomut — Gunbatar dialect, büdüremek>müdüremek in Ersari and Stavropol Turkmens’ dialects, bol>mol in Karakalpak Turkmens’ dialects, buzav>mizov in Kirac dialects.[53]

Here are some words from the Swadesh list to compare Azerbaijani with Turkmen:[54]

| Azerbaijani | Turkmen | English |

|---|---|---|

| mən | men | I, me |

| sən | sen | you |

| haçan | haçan | when |

| başqa | başga | other |

| it, köpək | it, köpek | dog |

| dəri | deri | skin, leather |

| yumurta | ýumurtga | egg |

| ürək | ýürek | heart |

| eşitmək | eşitmek | to hear |

Oghuric[edit]

Azerbaijani dialects share paradigms of verbs in some tenses with the Chuvash language,[39] on which linguists also rely in the study and reconstruction of the Khazar language.[39]

Phonology[edit]

Phonotactics[edit]

Azerbaijani phonotactics is similar to that of other Oghuz Turkic languages, except:

- Trimoraic syllables with long vowels are permissible.

- There is an ongoing metathesis of neighboring consonants in a word.[55] Speakers tend to reorder consonants in the order of decreasing sonority and back-to-front (for example, iləri becomes irəli, köprü becomes körpü, topraq becomes torpaq). Some of the metatheses are so common in the educated speech that they are reflected in orthography (all the above examples are like that). This phenomenon is more common in rural dialects but observed even in educated young urban speakers, but noticeably absent from some Southern dialects.

- Intramorpheme /q/ becomes /x/.

Consonants[edit]

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ŋ) | |||||||||||

| Stop/Affricate | p | b | t | d | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | c | ɟ | (k) | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | x | ɣ | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||||||||||

| Flap | ɾ |

- The sound [k] is used only in loanwords; the historical unpalatalized [k] became voiced to [ɡ].

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are realised as [t͡s] and [d͡z] respectively in the areas around Tabriz and to the west, south and southwest of Tabriz (including Kirkuk in Iraq); in the Nakhchivan and Ayrum dialects, in Cəbrayil and some Caspian coastal dialects;.[56]

- Sounds /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ may also be recognized as separate phonemic sounds in the Tabrizi and southern dialects.[57]

- In most dialects of Azerbaijani, /c/ is realized as [ç] when it is found in the syllabic coda or is preceded by a voiceless consonant (as in çörək [t͡ʃøˈɾæç] – «bread»; səksən [sæçˈsæn] – «eighty»).

- /w/ exists in the Kirkuk dialect as an allophone of /v/ in Arabic loanwords.

- In the Baku subdialect, /ov/ may be realised as [oʊ], and /ev/ and /øv/ as [øy], e.g. qovurma /ɡovurˈmɑ/ → *qourma [ɡoʊrˈmɑ], sevda /sevˈdɑ/ → *söüda [søyˈdɑ], dövran /døvˈrɑn/ → *döüran [døyˈrɑn], as well as with surnames ending in -ov or -ev (borrowed from Russian).[58]

- In colloquial speech, /x/ is usually pronounced as [χ]

Dialect consonants[edit]

- Dz dz—[d͡z]

- Ć ć—[t͡s]

- Ŋ ŋ—[ŋ]

- Q̇ q̇—[ɢ]

- Ð ð—[ð][citation needed]

- W w—[w, ɥ]

Examples:

- [d͡z]—dzan [d͡zɑn̪]

- [t͡s]—ćay [t͡sɑj]

- [ŋ]—ataŋın [ʔɑt̪ɑŋən̪]

- [ɢ]—q̇ar [ɢɑɾ]

- [ð]—əðəli [ʔæðæl̪ɪ]

- [w]—dowşan [d̪ɔːwʃɑn̪]

- [ɥ]—töwlə [t̪œːɥl̪æ]

Vowels[edit]

The vowels of the Azerbaijani are, in alphabetical order,[59][60] a /ɑ/, e /e/, ə /æ/, ı /ɯ/, i /i/, o /o/, ö /ø/, u /u/, ü /y/. There are no diphthongs in standard Azerbaijani when two vowels come together; when that occurs in some Arabic loanwords, diphthong is removed by either syllable separation at V.V boundary or fixing the pair as VC/CV pair, depending on the word.

South Azerbaijani vowel chart, from Mokari & Werner (2016:509)

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| Close | i | y | ɯ | u |

| Mid | e | ø | o | |

| Open | æ | ɑ |

|

This section needs expansion with: complete vowel allophonies. You can help by adding to it. (December 2018) |

The typical phonetic quality of South Azerbaijani vowels is as follows:

- /i, u, æ/ are close to cardinal [i, u, a].[61]

- The F1 and F2 formant frequencies overlap for /œ/ and /ɯ/. Their acoustic quality is more or less close-mid central [ɵ, ɘ]. The main role in the distinction of two vowels is played by the different F3 frequencies in audition,[62] and rounding in articulation. Phonologically, however, they are more distinct: /œ/ is phonologically a mid front rounded vowel, the front counterpart of /o/ and the rounded counterpart of /e/. /ɯ/ is phonologically a close back unrounded vowel, the back counterpart of /i/ and the unrounded counterpart of /u/.

- The other mid vowels /e, o/ are closer to close-mid [e, o] than open-mid [ɛ, ɔ].[61]

- /ɑ/ is phonetically near-open back [ɑ̝].[61]

Writing systems[edit]

Before 1929, Azerbaijani was written only in the Perso-Arabic alphabet, an impure abjad that does not represent all vowels (without diacritical marks). In Iran, Azerbaijani is still written in a modified form of the Persian alphabet that the newspaper Varlıq (started in 1979 by Javad Heyat) set the standard for.[63] Varlıq (وارلیق) wrote in a reformed Perso-Arabic alphabet that represents all vowels with the exception of «Ə» as elucidated further by the newspaper’s editor in a language guide written for Iranian Azerbaijanis titled «Türk dili yazı quralları» published in 2001.[63] Varlıq’s standard of writing is today canonized by the official Persian–Azeri Turkish dictionary in Iran titled «lugat name-ye Turki-ye Azarbayjani«.[64]

In 1929–1938 a Latin alphabet was in use for North Azerbaijani (although it was different from the one used now), from 1938 to 1991 the Cyrillic script was used, and in 1991 the current Latin alphabet was introduced, although the transition to it has been rather slow.[65] For instance, until an Aliyev decree on the matter in 2001,[66] newspapers would routinely write headlines in the Latin script, leaving the stories in Cyrillic.[67] The transition has also resulted in some misrendering of İ as Ì.[68][69] In Dagestan, Azerbaijani is still written in Cyrillic script.

The Azerbaijani Latin alphabet is based on the Turkish Latin alphabet, which in turn was based on former Azerbaijani Latin alphabet because of their linguistic connections and mutual intelligibility. The letters Әə, Xx, and Qq are available only in Azerbaijani for sounds which do not exist as separate phonemes in Turkish.

| Old Latin (1929–1938 version; no longer in use; replaced by 1991 version) |

Official Latin (Azerbaijan since 1991) |

Cyrillic (1958 version, still official in Dagestan) |

Perso-Arabic (Iran; Azerbaijan until 1929) |

IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | А а | آ / ـا | /ɑ/ | |

| B в | B b | Б б | ب | /b/ |

| Ç ç | C c | Ҹ ҹ | ج | /dʒ/ |

| C c | Ç ç | Ч ч | چ | /tʃ/ |

| D d | Д д | د | /d/ | |

| E e | Е е | ئ | /e/ | |

| Ə ə | Ә ә | ا / َ / ە | /æ/ | |

| F f | Ф ф | ف | /f/ | |

| G g | Ҝ ҝ | گ | /ɟ/ | |

| Ƣ ƣ | Ğ ğ | Ғ ғ | غ | /ɣ/ |

| H h | Һ һ | ح / ه | /h/ | |

| X x | Х х | خ | /x/ | |

| Ь ь | I ı | Ы ы | ؽ | /ɯ/ |

| I i | İ i | И и | ی | /i/ |

| Ƶ ƶ | J j | Ж ж | ژ | /ʒ/ |

| K k | К к | ک | /k/, /c/ | |

| Q q | Г г | ق | /ɡ/ | |

| L l | Л л | ل | /l/ | |

| M m | М м | م | /m/ | |

| N n | Н н | ن | /n/ | |

| Ꞑ ꞑ[70] | — | — | ݣ / نگ | /ŋ/ |

| O o | О о | وْ | /o/ | |

| Ɵ ɵ | Ö ö | Ө ө | ؤ | /ø/ |

| P p | П п | پ | /p/ | |

| R r | Р р | ر | /r/ | |

| S s | С с | ث / س / ص | /s/ | |

| Ş ş | Ш ш | ش | /ʃ/ | |

| T t | Т т | ت / ط | /t/ | |

| U u | У у | ۇ | /u/ | |

| Y y | Ü ü | Ү ү | ۆ | /y/ |

| V v | В в | و | /v/ | |

| J j | Y y | Ј ј | ی | /j/ |

| Z z | З з | ذ / ز / ض / ظ | /z/ | |

| — | ʼ | ع | /ʔ/ |

Northern Azerbaijani, unlike Turkish, respells foreign names to conform with Latin Azerbaijani spelling, e.g. Bush is spelled Buş and Schröder becomes Şröder. Hyphenation across lines directly corresponds to spoken syllables, except for geminated consonants which are hyphenated as two separate consonants as morphonology considers them two separate consonants back to back but enunciated in the onset of the latter syllable as a single long consonant, as in other Turkic languages.[citation needed]

Vocabulary[edit]

Interjections[edit]

Some samples include:

Secular:

- Of («Ugh!»)

- Tez Ol («Be quick!»)

- Tez olun qızlar mədrəsəyə («Be quick girls, to school!», a slogan for an education campaign in Azerbaijan)

Invoking deity:

- implicitly:

- Aman («Mercy»)

- Çox şükür («Much thanks»)

- explicitly:

- Allah Allah (pronounced as Allahallah) («Goodness gracious»)

- Hay Allah; Vallah «By God [I swear it]».

- Çox şükür allahım («Much thanks my god»)

Formal and informal[edit]

Azerbaijani has informal and formal ways of saying things. This is because there is a strong tu-vous distinction in Turkic languages like Azerbaijani and Turkish (as well as in many other languages). The informal «you» is used when talking to close friends, relatives, animals or children. The formal «you» is used when talking to someone who is older than you or someone for whom you would like to show respect (a professor, for example).

As in many Turkic languages, personal pronouns can be omitted, and they are only added for emphasis. Since 1992 North Azerbaijani has used a phonetic writing system, so pronunciation is easy: most words are pronounced exactly as they are spelled.

| Category | English | North Azerbaijani (in Latin script) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic expressions | yes | hə /hæ/ (informal), bəli (formal) |

| no | yox /jox/ (informal), xeyr (formal) | |

| hello | salam /sɑlɑm/ | |

| goodbye | sağ ol /ˈsɑɣ ol/ | |

| sağ olun /ˈsɑɣ olun/ (formal) | ||

| good morning | sabahınız xeyir /sɑbɑhɯ(nɯ)z xejiɾ/ | |

| good afternoon | günortanız xeyir /ɟynoɾt(ɑn)ɯz xejiɾ/ | |

| good evening | axşamın xeyir /ɑxʃɑmɯn xejiɾ/ | |

| axşamınız xeyir /ɑxʃɑmɯ(nɯ)z xejiɾ/ | ||

| Colours | black | qara /ɡɑɾɑ/ |

| blue | göy /ɟøj/ | |

| brown | qəhvəyi / qonur | |

| grey | boz /boz/ | |

| green | yaşıl /jaʃɯl/ | |

| orange | narıncı /nɑɾɯnd͡ʒɯ/ | |

| pink | çəhrayı

/t͡ʃæhɾɑjɯ/ |

|

| purple | bənövşəyi

/bænøvʃæji/ |

|

| red | qırmızı /ɡɯɾmɯzɯ/ | |

| white | ağ /ɑɣ/ | |

| yellow | sarı /sɑɾɯ/ |

Numbers[edit]

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 0 | sıfır /ˈsɯfɯɾ/ |

| 1 | bir /biɾ/ |

| 2 | iki /ici/ |

| 3 | üç /yt͡ʃ/ |

| 4 | dörd /døɾd/ |

| 5 | beş /beʃ/ |

| 6 | altı /ɑltɯ/ |

| 7 | yeddi /jed:i/ |

| 8 | səkkiz /sæc:iz/ |

| 9 | doqquz /doɡ:uz/ |

| 10 | on /on/ |

For numbers 11–19, the numbers literally mean «10 one, 10 two» and so on.

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 20 | iyirmi /ijiɾmi/ [d] |

| 30 | otuz /otuz/ |

| 40 | qırx /ɡɯɾx/ |

| 50 | əlli /ælli/ |

Greater numbers are constructed by combining in tens and thousands larger to smaller in the same way, without using a conjunction in between.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Former Cyrillic spelling used in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic.

- ^

- The written language of the Iraqi Turkmen is based on Istanbul Turkish using the modern Turkish alphabet.

- Professor Christiane Bulut has argued that publications from Azerbaijan often use expressions such as «Azerbaijani (dialects) of Iraq» or «South Azerbaijani» to describe Iraqi Turkmen dialects «with political implications»; however, in Turcological literature, closely related dialects in Turkey and Iraq are generally referred to as «eastern Anatolian» or «Iraq-Turkic/-Turkman» dialects, respectively.[1]

- ^ These latter two are more often used in Iranian Azerbaijan.

- ^ Since Azerbaijan’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, northern Azerbaijani uses the Latin alphabet. Iranian Azerbaijani, on the other hand, has always used and continues to use Arabic script.[41]

- ^ /iɾmi/ is also found in standard speech.

References[edit]

- ^ Bulut, Christiane (2018b), «The Turkic varieties of Iran», in Haig, Geoffrey; Khan, Geoffrey (eds.), The Languages and Linguistics of Western Asia: An Areal Perspective, Walter de Gruyter, p. 398, ISBN 978-3-11-042168-2

- ^ Azerbaijani language at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ a b c d e f g «Azerbaijani, North». Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f «Azerbaijani, South». Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Nemat Rahmati, Korkut Buğday: Aserbaidschanisch Lehrbuch. Unter Berücksichtigung des Nord- und Südaserbaidschanischen. = Aserbaidschanisch. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-03840-3.

- ^ Rahmati, Nemat (1998). Aserbaidschanisch Lehrbuch : unter Berücksichtigung des Nord- und Südaserbaidschanischen. Korkut M. Buğday. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-03840-3. OCLC 40415729.

- ^ «Türk dili, yoxsa azərbaycan dili? (Turkish language or Azerbaijani language?)». BBC (in Azerbaijani). 9 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b «AZERBAIJAN». Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2-3. 1987. pp. 205–257.

- ^ «From the Harvard Art Museums’ collections Illustrated manuscript of the Hadiqat al-Su’ada (Garden of the Blessed) by Fuzuli». harvardartmuseums.org.

- ^ «The Turkic Languages», Osman Fikri Sertkaya (2005) in Turks – A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600-1600, London ISBN 978-1-90397-356-1

- ^ Wright, Sue; Kelly, Helen (1998). Ethnicity in Eastern Europe: Questions of Migration, Language Rights and Education. Multilingual Matters Ltd. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-85359-243-0.

- ^ Bratt Paulston, Christina; Peckham, Donald (1 October 1998). Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe. Multilingual Matters Ltd. pp. 98–115. ISBN 978-1-85359-416-8.

- ^ L. Johanson, «AZERBAIJAN ix. Iranian Elements in Azeri Turkish» in Encyclopædia Iranica [1].

- ^ John R. Perry, «Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic» in Csató et al. (2005) Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, p. 97: «It is generally understood that the bulk of the Arabic vocabulary in the central, contiguous Iranic, Turkic and Indic languages was originally borrowed into literary Persian between the ninth and thirteenth centuries CE…»

- ^ electricpulp.com. «AZERBAIJAN ix. Iranian Elements in Azeri Turki – Encyclopaedia Iranica».

- ^ Tonoyan, Artyom (2019). «On the Caucasian Persian (Tat) Lexical Substratum in the Baku Dialect of Azerbaijani. Preliminary Notes». Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 169 (2): 368 (note 4). doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.169.2.0367.

- ^ Karpat, K. (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. Oxford University Press. p. 295.

- ^ «Alphabet Changes in Azerbaijan in the 20th Century». Azerbaijan International. Spring 2000. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Language Commission Suggested to Be Established in National Assembly. Day.az. 25 January 2011.

- ^ Johanson, L. (6 April 2010). Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Öztopcu, Kurtulus. «Azeri / Azerbaijani». American Association of Teachers of Turkic Languages. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Iranica. Azeri Literature in Iran The 15th century saw the beginning of a more important period in the history of the Azeri Turkish literature. The position of the literary language was reinforced under the Qarāqoyunlu (r. 1400-68), who had their capital in Tabriz. Jahānšāh (r. 1438-68) himself wrote lyrical poems in Turkish using the pen name of «Ḥaqiqi».

- ^ V. Minorsky. Jihān-Shāh Qara-Qoyunlu and His Poetry (Turkmenica, 9). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. — Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies, 1954. — V.16, p . 272, 283: «It is somewhat astonishing that a sturdy Turkman like Jihan-shah should have been so restricted in his ways of expression. Altogether the language of the poems belongs to the group of the southern Turkman dialects which go by the name of Azarbayjan Turkish.»; «As yet nothing seems to have been published on the Br. Mus. manuscript Or. 9493, which contains the bilingual collection of poems of Haqiqi, i.e. of the Qara-qoyunlu sultan Jihan-shah (A.D. 1438—1467).»

- ^ «AZERBAIJAN x. Azeri Literature [1988]». Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_eiro_com_11092. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ a b G. Doerfer, «Azeri Turkish», Encyclopaedia Iranica, viii, Online Edition, p. 246.

- ^ Mark R.V. Southern. Mark R V Southern (2005) Contagious couplings: transmission of expressives in Yiddish echo phrases, Praeger, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-31306-844-7

- ^ «Greetings to Heydar Baba». umich.edu. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ Pieter Muysken, «Introduction: Conceptual and methodological issues in areal linguistics», in Pieter Muysken (2008) From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics, p. 30-31 ISBN 978-90-272-3100-0 [2]

- ^ Viacheslav A. Chirikba, «The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund» in Muysken, p. 74

- ^ Lenore A. Grenoble (2003) Language Policy in the Soviet Union, p. 131 ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3 [3]

- ^ Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie. Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. – Elsevier, 2009. – С. 110–113. – ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7. An Azerbaijanian koine´ functioned for centuries as a lingua franca, serving trade and intergroup communication all over Persia, in the Caucasus region and in southeastern Dagestan. Its transregional validity continued at least until the 18th century.

- ^ [4] Nikolai Trubetzkoy (2000) Nasledie Chingiskhana, p. 478 Agraf, Moscow ISBN 978-5-77840-082-5 (Russian)

- ^ J. N. Postgate (2007) Languages of Iraq, p. 164, British School of Archaeology in Iraq ISBN 978-0-903472-21-0

- ^ Homa Katouzian (2003) Iranian history and politics, Routledge, pg 128: «Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability»