|

Bangkok กรุงเทพมหานคร |

|

|---|---|

|

Special administrative area |

|

From top, left to right: Wat Benchamabophit, Chao Phraya River skyline, Grand Palace, Giant Swing, traffic on a road in Watthana District, Democracy Monument, and Wat Arun |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

Location within Thailand |

|

| Coordinates: 13°45′09″N 100°29′39″E / 13.75250°N 100.49417°ECoordinates: 13°45′09″N 100°29′39″E / 13.75250°N 100.49417°E[1] | |

| Country | Thailand |

| Region | Central Thailand |

| Settled | c. 15th century |

| Founded as capital | 21 April 1782 |

| Re-incorporated | 13 December 1972 |

| Founded by | King Rama I |

| Governing body | Bangkok Metropolitan Administration |

| Government | |

| • Type | Special administrative area |

| • Governor | Chadchart Sittipunt (Indp.) |

| Area

[1] |

|

| • City | 1,568.737 km2 (605.693 sq mi) |

| • Metro

[2] |

7,761.6 km2 (2,996.8 sq mi) |

| Elevation

[3] |

1.5 m (4.9 ft) |

| Population

(2010 census)[4] |

|

| • City | 8,305,218 |

| • Estimate

(2020)[5] |

10,539,000 |

| • Density | 5,300/km2 (14,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 14,626,225 |

| • Metro density | 1,900/km2 (4,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Bangkokian |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (ICT) |

| Postal code |

10### |

| Area code | 02 |

| ISO 3166 code | TH-10 |

| Website | main.bangkok.go.th |

Bangkok,[a] officially known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon[b] and colloquially as Krung Thep,[c] is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies 1,568.7 square kilometres (605.7 sq mi) in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estimated population of 10.539 million as of 2020, 15.3 percent of the country’s population. Over 14 million people (22.2 percent) lived within the surrounding Bangkok Metropolitan Region at the 2010 census, making Bangkok an extreme primate city, dwarfing Thailand’s other urban centres in both size and importance to the national economy.

Bangkok traces its roots to a small trading post during the Ayutthaya Kingdom in the 15th century, which eventually grew and became the site of two capital cities, Thonburi in 1768 and Rattanakosin in 1782. Bangkok was at the heart of the modernization of Siam, later renamed Thailand, during the late-19th century, as the country faced pressures from the West. The city was at the centre of Thailand’s political struggles throughout the 20th century, as the country abolished absolute monarchy, adopted constitutional rule, and underwent numerous coups and several uprisings. The city, incorporated as a special administrative area under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration in 1972, grew rapidly during the 1960s through the 1980s and now exerts a significant impact on Thailand’s politics, economy, education, media and modern society.

The Asian investment boom in the 1980s and 1990s led many multinational corporations to locate their regional headquarters in Bangkok. The city is now a regional force in finance and business. It is an international hub for transport and health care, and has emerged as a centre for the arts, fashion, and entertainment. The city is known for its street life and cultural landmarks, as well as its red-light districts. The Grand Palace and Buddhist temples including Wat Arun and Wat Pho stand in contrast with other tourist attractions such as the nightlife scenes of Khaosan Road and Patpong. Bangkok is among the world’s top tourist destinations, and has been named the world’s most visited city consistently in several international rankings.

Bangkok’s rapid growth coupled with little urban planning has resulted in a haphazard cityscape and inadequate infrastructure. Despite an extensive expressway network, an inadequate road network and substantial private car usage have led to chronic and crippling traffic congestion, which caused severe air pollution in the 1990s. The city has since turned to public transport in an attempt to solve the problem, operating eight urban rail lines and building other public transit, but congestion still remains a prevalent issue. The city faces long-term environmental threats such as sea level rise due to climate change.

History[edit]

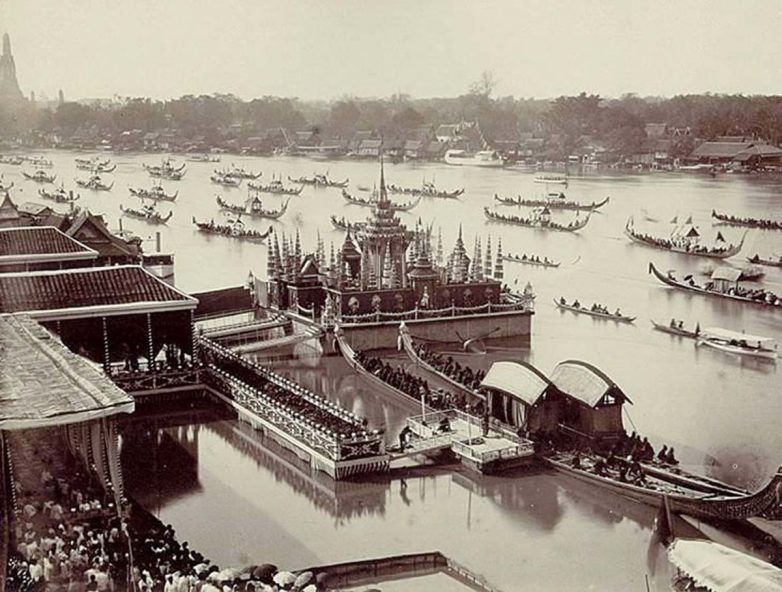

The history of Bangkok dates at least back to the early 15th century, to when it was a village on the west bank of the Chao Phraya River, under the rule of Ayutthaya.[9] Because of its strategic location near the mouth of the river, the town gradually increased in importance. Bangkok initially served as a customs outpost with forts on both sides of the river, and was the site of a siege in 1688 in which the French were expelled from Siam. After the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767, the newly crowned King Taksin established his capital at the town, which became the base of the Thonburi Kingdom. In 1782, King Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I) succeeded Taksin, moved the capital to the eastern bank’s Rattanakosin Island, thus founding the Rattanakosin Kingdom. The City Pillar was erected on 21 April 1782, which is regarded as the date of foundation of Bangkok as the capital.[10]

Bangkok’s economy gradually expanded through international trade, first with China, then with Western merchants returning in the early-to-mid 19th century. As the capital, Bangkok was the centre of Siam’s modernization as it faced pressure from Western powers in the late-19th century. The reigns of Kings Mongkut (Rama IV, r. 1851–68) and Chulalongkorn (Rama V, r. 1868–1910) saw the introduction of the steam engine, printing press, rail transport and utilities infrastructure in the city, as well as formal education and healthcare. Bangkok became the centre stage for power struggles between the military and political elite as the country abolished absolute monarchy in 1932.[11]

Engraving of the city from British diplomat John Crawfurd’s embassy in 1822

As Thailand allied with Japan in World War II, Bangkok was subjected to Allied bombing, but rapidly grew in the post-war period as a result of US aid and government-sponsored investment. Bangkok’s role as a US military R&R destination boosted its tourism industry as well as firmly establishing it as a sex tourism destination. Disproportionate urban development led to increasing income inequalities and migration from rural areas into Bangkok; its population surged from 1.8 million to 3 million in the 1960s.[11]

Following the US withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973, Japanese businesses took over as leaders in investment, and the expansion of export-oriented manufacturing led to growth of the financial market in Bangkok.[11] Rapid growth of the city continued through the 1980s and early 1990s, until it was stalled by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. By then, many public and social issues had emerged, among them the strain on infrastructure reflected in the city’s notorious traffic jams. Bangkok’s role as the nation’s political stage continues to be seen in strings of popular protests, from the student uprisings in 1973 and 1976, anti-military demonstrations in 1992, and frequent street protests since 2006, including those by groups opposing and supporting former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra from 2006 to 2013, and a renewed student-led movement in 2020.[12]

Administration of the city was first formalized by King Chulalongkorn in 1906, with the establishment of Monthon Krung Thep Phra Maha Nakhon (มณฑลกรุงเทพพระมหานคร) as a national subdivision. In 1915, the monthon was split into several provinces, the administrative boundaries of which have since further changed. The city in its current form was created in 1972 with the formation of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), following the merger of Phra Nakhon province on the eastern bank of the Chao Phraya and Thonburi province on the west during the previous year.[10]

Name[edit]

The origin of the name Bangkok (บางกอก, pronounced in Thai as [bāːŋ kɔ̀ːk] (listen)) is unclear. Bang บาง is a Thai word meaning ‘a village on a stream’,[13] and the name might have been derived from Bang Ko (บางเกาะ), ko เกาะ meaning ‘island’, stemming from the city’s watery landscape.[9] Another theory suggests that it is shortened from Bang Makok (บางมะกอก), makok มะกอก being the name of Elaeocarpus hygrophilus, a plant bearing olive-like fruit.[d] This is supported by the former name of Wat Arun, a historic temple in the area, that used to be called Wat Makok.[14] The Romanization «Bangkok» comes from French.[citation needed]

Officially, the town was known as Thonburi Si Mahasamut (ธนบุรีศรีมหาสมุทร, from Pali and Sanskrit, literally ‘city of treasures gracing the ocean’) or Thonburi, according to the Ayutthaya Chronicles.[15] Bangkok was likely a colloquial name, albeit one widely adopted by foreign visitors, who continued to use it to refer to the city even after the new capital’s establishment.

When King Rama I established his new capital on the river’s eastern bank, the city inherited Ayutthaya’s ceremonial name, of which there were many variants, including Krung Thep Thawarawadi Si Ayutthaya (กรุงเทพทวารวดีศรีอยุธยา) and Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Si Ayutthaya (กรุงเทพมหานครศรีอยุธยา).[16] Edmund Roberts, visiting the city as envoy of the United States in 1833, noted that the city, since becoming capital, was known as Sia-Yut’hia, and this is the name used in international treaties of the period.[17]

Today, the city is known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon (กรุงเทพมหานคร) or simply Krung Thep (กรุงเทพฯ), a shortening of the ceremonial name which came into use during the reign of King Mongkut. The full name reads as follows:[e][10]

Krungthepmahanakhon Amonrattanakosin Mahintharayutthaya Mahadilokphop Noppharatratchathaniburirom Udomratchaniwetmahasathan Amonphimanawatansathit Sakkathattiyawitsanukamprasit[f]

กรุงเทพมหานคร อมรรัตนโกสินทร์ มหินทรายุธยา มหาดิลกภพ นพรัตนราชธานีบูรีรมย์ อุดมราชนิเวศน์มหาสถาน อมรพิมานอวตารสถิต สักกะทัตติยวิษณุกรรมประสิทธิ์

The name, composed of Pali and Sanskrit root words, translates as:

City of angels, great city of immortals, magnificent city of the nine gems, seat of the king, city of royal palaces, home of gods incarnate, erected by Vishvakarman at Indra’s behest.[18]

The name is listed in Guinness World Records as the world’s longest place name, at 168 letters.[19][g] Many Thais who recall the full name do so because of its use in the 1989 song «Krung Thep Maha Nakhon» by Thai rock band Asanee–Wasan, the lyrics of which consist entirely of the city’s full name, repeated throughout the song.[20]

The city is now officially known in Thai by a shortened form of the full ceremonial name, Krung Thep Maha Nakhon, which is colloquially further shortened to Krung Thep (city of gods). Krung, กรุง is a Thai word of Mon–Khmer origin, meaning ‘capital, king’,[21][verification needed] while thep, เทพ is from Pali/Sanskrit, meaning ‘deity’ or ‘god’ and corresponding to deva.

Government[edit]

The city’s ceremonial name is displayed in front of Bangkok City Hall.

The city of Bangkok is locally governed by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA). Although its boundaries are at the provincial (changwat) level, unlike the other 76 provinces Bangkok is a special administrative area whose governor is directly elected to serve a four-year term. The governor, together with four appointed deputies, form the executive body, who implement policies through the BMA civil service headed by the Permanent Secretary for the BMA. In separate elections, each district elects one or more city councillors, who form the Bangkok Metropolitan Council. The council is the BMA’s legislative body, and has power over municipal ordinances and the city’s budget.[22] The latest gubernatorial election took place on 22 May 2022 after an extended lapse following the 2014 Thai coup d’état, and was won by Chadchart Sittipunt.[23]

Bangkok is divided into fifty districts (khet, equivalent to amphoe in the other provinces), which are further subdivided into 180 sub-districts (khwaeng, equivalent to tambon). Each district is managed by a district director appointed by the governor. District councils, elected to four-year terms, serve as advisory bodies to their respective district directors.

The BMA is divided into sixteen departments, each overseeing different aspects of the administration’s responsibilities. Most of these responsibilities concern the city’s infrastructure, and include city planning, building control, transportation, drainage, waste management and city beautification, as well as education, medical and rescue services.[24] Many of these services are provided jointly with other agencies. The BMA has the authority to implement local ordinances, although civil law enforcement falls under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police Bureau.

The seal of the city shows Hindu god Indra riding in the clouds on Airavata, a divine white elephant known in Thai as Erawan. In his hand Indra holds his weapon, the vajra.[25] The seal is based on a painting done by Prince Naris. The tree symbol of Bangkok is Ficus benjamina.[26] The official city slogan, adopted in 2012, reads:

As built by deities, the administrative centre, dazzling palaces and temples, the capital of Thailand

กรุงเทพฯ ดุจเทพสร้าง เมืองศูนย์กลางการปกครอง วัดวังงามเรืองรอง เมืองหลวงของประเทศไทย[27]

As the capital of Thailand, Bangkok is the seat of all branches of the national government. The Government House, Parliament House and Supreme, Administrative and Constitutional Courts are all in the city. Bangkok is the site of the Grand Palace and Dusit Palace, respectively the official and de facto residence of the king. Most government ministries also have headquarters and offices in the capital.

Geography[edit]

The city of Bangkok is highlighted in this satellite image of the lower Chao Phraya delta. The built-up urban area extends northward and southward into Nonthaburi and Samut Prakan provinces.

Bangkok covers an area of 1,568.7 square kilometres (605.7 sq mi), ranking 69th among the other 76 provinces of Thailand. Of this, about 700 square kilometres (270 sq mi) form the built-up urban area.[1] It is ranked 73rd in the world in terms of land area.[28] The city’s urban sprawl reaches into parts of the six other provinces that it borders, namely, in clockwise order from northwest: Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani, Chachoengsao, Samut Prakan, Samut Sakhon, and Nakhon Pathom. With the exception of Chachoengsao, these provinces, together with Bangkok, form the greater Bangkok Metropolitan Region.[2]

Topography[edit]

Bangkok is situated in the Chao Phraya River delta in Thailand’s central plain. The river meanders through the city in a southerly direction, emptying into the Gulf of Thailand approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of city centre. The area is flat and low-lying, with an average elevation of 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) above sea level.[3][h] Most of the area was originally swampland, which was gradually drained and irrigated for agriculture by the construction of canals (khlong) which took place from the 16th to 19th centuries. The course of the river as it flows through Bangkok has been modified by the construction of several shortcut canals.

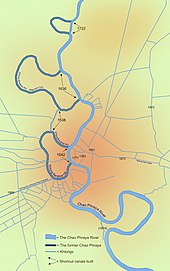

Bangkok’s major canals are shown in this map, detailing the original course of the river and its shortcut canals.

The city’s waterway network served as the primary means of transport until the late 19th century, when modern roads began to be built. Up until then, most people lived near or on the water, leading the city to be known during the 19th century as the «Venice of the East».[29] Many of these canals have since been filled in or paved over, but others still criss-cross the city, serving as major drainage channels and transport routes. Most canals are now badly polluted, although the BMA has committed to the treatment and cleaning up of several canals.[30]

The geology of the Bangkok area is characterized by a top layer of soft marine clay, known as «Bangkok clay», averaging 15 metres (49 ft) in thickness, which overlies an aquifer system consisting of eight known units. This feature has contributed to the effects of subsidence caused by extensive groundwater pumping. First recognized in the 1970s, subsidence soon became a critical issue, reaching a rate of 120 millimetres (4.7 in) per year in 1981. Ground water management and mitigation measures have since lessened the severity of the situation, and the rate of subsidence decreased to 10 to 30 millimetres (0.39 to 1.18 in) per year in the early 2000s, though parts of the city are now 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) below sea level.[31]

Subsidence has resulted in increased flood risk, as Bangkok is already prone to flooding due to its low elevation and an inadequate drainage infrastructure,[32][33] often compounded by blockage from rubbish pollution (especially plastic waste).[34] The city now relies on flood barriers and augmenting drainage from canals by pumping and building drain tunnels, but parts of Bangkok and its suburbs are still regularly inundated. Heavy downpours resulting in urban runoff overwhelming drainage systems, and runoff discharge from upstream areas, are major triggering factors.[35] Severe flooding affecting much of the city occurred in 1995 and 2011. In 2011, most of Bangkok’s northern, eastern and western districts were flooded, in some places for over two months.

Bangkok population density and low elevation coastal zones. Bangkok is especially vulnerable to sea level rise.

Bangkok’s coastal location makes it particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels due to global warming and climate change. A study by the OECD has estimated that 5.138 million people in Bangkok may be exposed to coastal flooding by 2070, the seventh highest figure among the world’s port cities.[36]: 8 There are fears that the city may be submerged by 2030.[37][38][39] A study published in October 2019 in Nature Communications corrected earlier models of coastal elevations[40] and concluded that up to 12 million Thais—mostly in the greater Bangkok metropolitan area—face the prospect of annual flooding events.[41][42] This is compounded by coastal erosion, which is an issue in the gulf coastal area, a small length of which lies within Bangkok’s Bang Khun Thian District. Tidal flat ecosystems existed on the coast, however, many have been reclaimed for agriculture, aquaculture, and salt works.[43]

There are no mountains in Bangkok. The closest mountain range is the Khao Khiao Massif, about 40 km (25 mi) southeast of the city. Phu Khao Thong, the only hill in the metropolitan area, originated with a very large chedi that King Rama III (1787–1851) built at Wat Saket. The chedi collapsed during construction because the soft soil could not support its weight. Over the next few decades, the abandoned mud-and-brick structure acquired the shape of a natural hill and became overgrown with weeds. The locals called it phu khao (ภูเขา), as if it were a natural feature.[44] In the 1940s, enclosing concrete walls were added to stop the hill from eroding.[45]

Climate[edit]

Like most of Thailand, Bangkok has a tropical savanna climate (Aw) under the Köppen climate classification and is under the influence of the South Asian monsoon system. The city experiences three seasons: hot, rainy, and cool, although temperatures are fairly hot year-round, ranging from an average low of 22.0 °C (71.6 °F) in December to an average high of 35.4 °C (95.7 °F) in April. The rainy season begins with the arrival of the southwest monsoon around mid-May. September is the wettest month, with an average rainfall of 334.3 millimetres (13.16 in). The rainy season lasts until October, when the dry and cool northeast monsoon takes over until February. The hot season is generally dry, but also sees occasional summer storms.[46] The surface magnitude of Bangkok’s urban heat island has been measured at 2.5 °C (4.5 °F) during the day and 8.0 °C (14 °F) at night.[47] The highest recorded temperature of Bangkok metropolis was 40.1 °C (104.2 °F) in March 2013,[48] and the lowest recorded temperature was 9.9 °C (49.8 °F) in January 1955.[49]

The Climate Impact Group at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies projected severe weather impacts on Bangkok caused by climate change. It found that Bangkok in 1960 had 193 days at or above 32 °C. In 2018, Bangkok can expect 276 days at or above 32 °C. The group forecasts a rise by 2100 to, on average, 297 to 344 days at or above 32 °C.[50]

| Climate data for Bangkok Metropolis (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.6 (99.7) |

38.8 (101.8) |

40.1 (104.2) |

40.2 (104.4) |

39.7 (103.5) |

38.3 (100.9) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.8 (101.8) |

37.1 (98.8) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 13.3 (0.52) |

20.0 (0.79) |

42.1 (1.66) |

91.4 (3.60) |

247.7 (9.75) |

157.1 (6.19) |

175.1 (6.89) |

219.3 (8.63) |

334.3 (13.16) |

292.1 (11.50) |

49.5 (1.95) |

6.3 (0.25) |

1,648.2 (64.89) |

| Average rainy days | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 6.6 | 16.4 | 16.3 | 17.4 | 19.6 | 21.2 | 17.7 | 5.8 | 1.1 | 129.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 75 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 79 | 78 | 70 | 66 | 73 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

22 (72) |

20 (68) |

23 (74) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.5 | 249.9 | 269.0 | 256.7 | 216.4 | 178.0 | 171.8 | 160.3 | 154.9 | 198.1 | 234.2 | 262.0 | 2,623.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 78 | 75 | 73 | 68 | 55 | 45 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 56 | 71 | 76 | 60 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 11 |

| Source 1: Thai Meteorological Department,[51] humidity (1981–2010): RID;[52] Rainfall (1981–2010): RID[53] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV),[54] Time and Date (dewpoints, 2005-2015),[55] NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[56] |

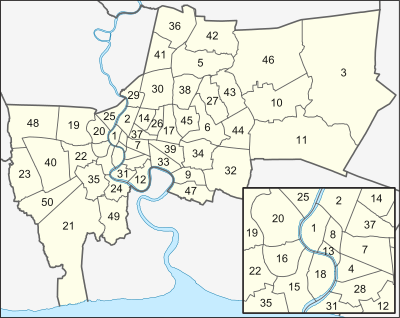

Districts[edit]

Bangkok’s fifty districts serve as administrative subdivisions under the authority of the BMA. Thirty-five of these districts lie to the east of the Chao Phraya, while fifteen are on the western bank, known as the Thonburi side of the city. The fifty districts, arranged by district code, are:[57]

- Phra Nakhon district

- Dusit district

- Nong Chok district

- Bang Rak district

- Bang Khen district

- Bang Kapi district

- Pathum Wan district

- Pom Prap Sattru Phai district

- Phra Khanong district

- Min Buri district

- Lat Krabang district

- Yan Nawa district

- Samphanthawong district

- Phaya Thai district

- Thon Buri district

- Bangkok Yai district

- Huai Khwang district

- Khlong San district

- Taling Chan district

- Bangkok Noi district

- Bang Khun Thian district

- Phasi Charoen district

- Nong Khaem district

- Rat Burana district

- Bang Phlat district

- Din Daeng district

- Bueng Kum district

- Sathon district

- Bang Sue district

- Chatuchak district

- Bang Kho Laem district

- Prawet district

- Khlong Toei district

- Suan Luang district

- Chom Thong district

- Don Mueang district

- Ratchathewi district

- Lat Phrao district

- Watthana district

- Bang Khae district

- Lak Si district

- Sai Mai district

- Khan Na Yao district

- Saphan Sung district

- Wang Thonglang district

- Khlong Sam Wa district

- Bang Na district

- Thawi Watthana district

- Thung Khru district

- Bang Bon district

Cityscape[edit]

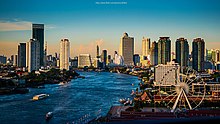

View of the Chao Phraya River as it passes through Bang Kho Laem and Khlong San districts

Bangkok’s districts often do not accurately represent the functional divisions of its neighbourhoods or land usage. Although urban planning policies date back to the commission of the «Litchfield Plan» in 1960, which set out strategies for land use, transportation and general infrastructure improvements, zoning regulations were not fully implemented until 1992. As a result, the city grew organically throughout the period of its rapid expansion, both horizontally as ribbon developments extended along newly built roads, and vertically, with increasing numbers of high rises and skyscrapers being built in commercial areas.[58]

The city has grown from its original centre along the river into a sprawling metropolis surrounded by swaths of suburban residential development extending north and south into neighbouring provinces. The highly populated and growing cities of Nonthaburi, Pak Kret, Rangsit and Samut Prakan are effectively now suburbs of Bangkok. Nevertheless, large agricultural areas remain within the city proper at its eastern and western fringes, and a small number of forest area is found within the city limits: 3,887 rai (6.2 km2; 2.4 sq mi), amounting to 0.4 percent of city area.[59] Land use in the city consists of 23 percent residential use, 24 percent agriculture, and 30 percent used for commerce, industry, and government.[1] The BMA’s City Planning Department (CPD) is responsible for planning and shaping further development. It published master plan updates in 1999 and 2006, and a third revision is undergoing public hearings in 2012.[60]

The Royal Plaza in Dusit District was inspired by King Chulalongkorn’s visits to Europe.

Bangkok’s historic centre remains the Rattanakosin Island in Phra Nakhon District.[61] It is the site of the Grand Palace and the City Pillar Shrine, primary symbols of the city’s founding, as well as important Buddhist temples. Phra Nakhon, along with the neighbouring Pom Prap Sattru Phai and Samphanthawong Districts, formed what was the city proper in the late 19th century. Many traditional neighbourhoods and markets are found here, including the Chinese settlement of Sampheng.[61] The city was expanded toward Dusit District in the early 19th century, following King Chulalongkorn’s relocation of the royal household to the new Dusit Palace. The buildings of the palace, including the neoclassical Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall, as well as the Royal Plaza and Ratchadamnoen Avenue which leads to it from the Grand Palace, reflect the heavy influence of European architecture at the time. Major government offices line the avenue, as does the Democracy Monument. The area is the site of the country’s seat of power as well as the city’s most popular tourist landmarks.[61]

In contrast with the low-rise historic areas, the business district on Si Lom and Sathon Roads in Bang Rak and Sathon Districts teems with skyscrapers. It is the site of many of the country’s major corporate headquarters, but also of some of the city’s red-light districts. The Siam and Ratchaprasong areas in Pathum Wan are home to some of the largest shopping malls in Southeast Asia. Numerous retail outlets and hotels also stretch along Sukhumvit Road leading southeast through Watthana and Khlong Toei Districts. More office towers line the streets branching off Sukhumvit, especially Asok Montri, while upmarket housing is found in many of its sois (‘alley’ or ‘lane’).

Bangkok lacks a single distinct central business district. Instead, the areas of Siam and Ratchaprasong serve as a «central shopping district» containing many of the bigger malls and commercial areas in the city, as well as Siam Station, the only transfer point between the city’s two elevated train lines.[62] The Victory Monument in Ratchathewi District is among its most important road junctions, serving over 100 bus lines as well as an elevated train station. From the monument, Phahonyothin and Ratchawithi / Din Daeng Roads respectively run north and east linking to major residential areas. Most of the high-density development areas are within the 113-square-kilometre (44 sq mi) area encircled by the Ratchadaphisek inner ring road. Ratchadaphisek is lined with businesses and retail outlets, and office buildings also cluster around Ratchayothin Intersection in Chatuchak District to the north. Farther from the city centre, most areas are primarily mid- or low-density residential. The Thonburi side of the city is less developed, with fewer high rises. With the exception of a few secondary urban centres, Thonburi, in the same manner as the outlying eastern districts, consists mostly of residential and rural areas.

While most of Bangkok’s streets are fronted by vernacular shophouses, the largely unrestricted building euphoria of the 1980s has transformed the city into an urban area of skyscrapers and high rises of contrasting and clashing styles.[63] There are 581 skyscrapers over 90 metres (300 feet) tall in the city. Bangkok was ranked as the world’s eighth tallest city in 2016.[64] As a result of persistent economic disparity, many slums have emerged in the city. In 2000 there were over one million people living in about 800 informal settlements.[65] Some settlements are squatted such as the large slums in Khlong Toei District. In total there were 125 squatted areas.[65]

Parks and green zones[edit]

Bangkok has several parks, although these amount to a per capita total park area of only 1.82 square metres (19.6 sq ft) in the city proper. Total green space for the entire city is moderate, at 11.8 square metres (127 sq ft) per person. In the more densely built-up areas of the city these numbers are as low as 1.73 and 0.72 square metres (18.6 and 7.8 sq ft) per person.[66] More recent numbers claim that there is 3.3 square metres (36 sq ft) of green space per person,[67] compared to an average of 39 square metres (420 sq ft) in other cities across Asia. In Europe, London has 33.4 m2 of green space per head.[68] Bangkokians thus have 10 times less green space than is standard in the region’s urban areas.[69] Green belt areas include about 700 square kilometres (270 sq mi) of rice paddies and orchards on the eastern and western edges of the city, although their primary purpose is to serve as flood detention basins rather than to limit urban expansion.[70] Bang Kachao, a 20-square-kilometre (7.7 sq mi) conservation area on an oxbow of the Chao Phraya, lies just across the southern riverbank districts, in Samut Prakan province. A master development plan has been proposed to increase total park area to 4 square metres (43 sq ft) per person.[66]

Bangkok’s largest parks include the centrally located Lumphini Park near the Si Lom–Sathon business district with an area of 57.6 hectares (142 acres), the 80-hectare (200-acre) Suanluang Rama IX in the east of the city, and the Chatuchak–Queen Sirikit–Wachirabenchathat park complex in northern Bangkok, which has a combined area of 92 hectares (230 acres).[71] More parks are expected to be created through the Green Bangkok 2030 project, which aims to leave the city with 10 square metres (110 sq ft) of green space per person, including 30% of the city having tree cover.[72]

Demography[edit]

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 1919 | 437,294 |

| 1929 | 713,384 |

| 1937 | 890,453 |

| 1947 | 1,178,881 |

| 1960 | 2,136,435 |

| 1970 | 3,077,361 |

| 1980 | 4,697,071 |

| 1990 | 5,882,411 |

| 2000 | 6,355,144 |

| 2010 | 8,305,218 |

| Source: National Statistical Office (1919–2000,[73] 2010[4]) |

The city of Bangkok has a population of 8,305,218 according to the 2010 census, or 12.6 percent of the national population,[4] while 2020 estimates place the figure at 10.539 million (15.3 percent).[5] Roughly half are internal migrants from other Thai provinces;[48] population registry statistics recorded 5,676,648 residents belonging to 2,959,524 households in 2018.[74] Much of Bangkok’s daytime population commutes from surrounding provinces in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region, the total population of which is 14,626,225 (2010 census).[4] Bangkok is a cosmopolitan city; the census showed that it is home to 567,120 expatriates from Asian countries (including 71,024 Chinese and 63,069 Japanese nationals), 88,177 from Europe, 32,241 from the Americas, 5,856 from Oceania and 5,758 from Africa. Migrants from neighbouring countries include 216,528 Burmese, 72,934 Cambodians and 52,498 Lao.[75] In 2018, numbers show that there are 370,000 international migrants registered with the Department of Employment, more than half of them migrants from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.[48]

Following its establishment as capital city in 1782, Bangkok grew only slightly throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. British diplomat John Crawfurd, visiting in 1822, estimated its population at no more than 50,000.[76] As a result of Western medicine brought by missionaries as well as increased immigration from both within Siam and overseas, Bangkok’s population gradually increased as the city modernized in the late 19th century. This growth became even more pronounced in the 1930s, following the discovery of antibiotics. Although family planning and birth control were introduced in the 1960s, the lowered birth rate was more than offset by increased migration from the provinces as economic expansion accelerated. Only in the 1990s have Bangkok’s population growth rates decreased, following the national rate. Thailand had long since become highly centralized around the capital. In 1980, Bangkok’s population was fifty-one times that of Hat Yai and Songkhla, the second-largest urban centre at the time, making it the world’s most prominent primate city.[77][78]

The majority of Bangkok’s population identify as Thai,[i] although details on the city’s ethnic make-up are unavailable, as the national census does not document race.[j] Bangkok’s cultural pluralism dates back to the early days of its founding: several ethnic communities were formed by immigrants and forced settlers including the Khmer, northern Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, Mon and Malay.[10] Most prominent were the Chinese, who played major roles in the city’s trade and became the majority of Bangkok’s population—estimates include up to three-fourths in 1828 and almost half in the 1950s.[82][k] Chinese immigration was restricted from the 1930s and effectively ceased after the Chinese Revolution in 1949. Their prominence subsequently declined as younger generations of Thai Chinese integrated and adopted a Thai identity. Bangkok is still nevertheless home to a large Chinese community, with the greatest concentration in Yaowarat, Bangkok’s Chinatown.

Religion in Bangkok

Not Religious and Unknown (0.2%)

Other (0.29%)

The majority (93 percent) of the city’s population is Buddhist, according to the 2010 census. Other religions include Islam (4.6 percent), Christianity (1.9 percent), Hinduism (0.3 percent), Sikhism (0.1 percent) and Confucianism (0.1 percent).[84]

Apart from Yaowarat, Bangkok also has several other distinct ethnic neighbourhoods. The Indian community is centred in Phahurat, where the Gurdwara Siri Guru Singh Sabha, founded in 1933, is located. Ban Khrua on Saen Saep Canal is home to descendants of the Cham who settled in the late 18th century. Although the Portuguese who settled during the Thonburi period have ceased to exist as a distinct community, their past is reflected in Santa Cruz Church, on the west bank of the river. Likewise, Assumption Cathedral on Charoen Krung Road is among many European-style buildings in the Old Farang Quarter, where European diplomats and merchants lived in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Nearby, the Haroon Mosque is the centre of a Muslim community. Newer expatriate communities exist along Sukhumvit Road, including the Japanese community near Soi Phrom Phong and Soi Thong Lo, and the Arab and North African neighbourhood along Soi Nana. Sukhumvit Plaza, a mall on Soi Sukhumvit 12, is popularly known as Korea Town.

Economy[edit]

MahaNakhon, the city’s tallest building from 2016 to 2018, stands among the skyscrapers of Sathon Road, one of Bangkok’s main financial districts.

Bangkok is the economic centre of Thailand, and the heart of the country’s investment and development. In 2010, the city had an economic output of 3.142 trillion baht (US$98.34 billion), contributing 29.1 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). This amounted to a per-capita GDP value of 456,911 baht ($14,301), almost three times the national average of 160,556 baht ($5,025). The Bangkok Metropolitan Region had a combined output of 4.773 trillion baht ($149.39 billion), or 44.2 percent of GDP.[85] Bangkok’s economy ranked as the sixth among Asian cities in terms of per-capita GDP, after Singapore, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Osaka–Kobe and Seoul, as of 2010.[86][needs update]

Wholesale and retail trade is the largest sector in the city’s economy, contributing 24 percent of Bangkok’s gross provincial product. It is followed by manufacturing (14.3 percent); real estate, renting and business activities (12.4 percent); transport and communications (11.6 percent); and financial intermediation (11.1 percent). Bangkok alone accounts for 48.4 percent of Thailand’s service sector, which in turn constitutes 49 percent of GDP. When the Bangkok Metropolitan Region is considered, manufacturing is the most significant contributor at 28.2 percent of the gross regional product, reflecting the density of industry in the Bangkok’s neighbouring provinces.[87] The automotive industry based around Greater Bangkok is the largest production hub in Southeast Asia.[88] Tourism is also a significant contributor to Bangkok’s economy, generating 427.5 billion baht ($13.38 billion) in revenue in 2010.[89]

The Siam area is home to multiple shopping centres catering to both the middle and upper classes and tourists.

The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) is on Ratchadaphisek Road in inner Bangkok. The SET, together with the Market for Alternative Investment (MAI) has 648 listed companies as of the end of 2011, with a combined market capitalization of 8.485 trillion baht ($267.64 billion).[90] Due to the large amount of foreign representation, Thailand has for several years been a mainstay of the Southeast Asian economy and a centre of Asian business. The Globalization and World Cities Research Network ranks Bangkok as an «Alpha -» world city, and it is ranked 59th in Z/Yen’s Global Financial Centres Index 11.[91][92]

Bangkok is home to the headquarters of all of Thailand’s major commercial banks and financial institutions, as well as the country’s largest companies. Many multinational corporations base their regional headquarters in Bangkok due to the lower cost of labour and operations relative to other major Asian business centres. Seventeen Thai companies are listed on the Forbes 2000, all of which are based in the capital,[93] including PTT, the only Fortune Global 500 company in Thailand.[94]

Income inequality is a major issue in Bangkok, especially between relatively unskilled lower-income immigrants from rural provinces and neighbouring countries, and middle-class professionals and business elites. Although absolute poverty rates are low—only 0.64 percent of Bangkok’s registered residents were living under the poverty line in 2010, compared to a national average of 7.75 percent—economic disparity is still substantial.[95] The city has a Gini coefficient of 0.48, indicating a high level of inequality.[96]

Tourism[edit]

Bangkok is one of the world’s top tourist destinations. Of 162 cities worldwide, MasterCard ranked Bangkok as the top destination city by international visitor arrivals in its Global Destination Cities Index 2018, ahead of London, with just over 20 million overnight visitors in 2017.[97] This was a repeat of its 2017 ranking (for 2016).[98][99] Euromonitor International ranked Bangkok fourth in its Top City Destinations Ranking for 2016.[100] Bangkok was also named «World’s Best City» by Travel + Leisure magazine’s survey of its readers for four consecutive years, from 2010 to 2013.[101]

As the main gateway through which visitors arrive in Thailand, Bangkok is visited by the majority of international tourists to the country. Domestic tourism is also prominent. The Department of Tourism recorded 26,861,095 Thai and 11,361,808 foreign visitors to Bangkok in 2010. Lodgings were made by 15,031,244 guests, who occupied 49.9 percent of the city’s 86,687 hotel rooms.[89] Bangkok also topped the list as the world’s most popular tourist destinations in 2017 rankings.[102][103][104][105]

Bangkok’s multi-faceted sights, attractions and city life appeal to diverse groups of tourists. Royal palaces and temples as well as several museums constitute its major historical and cultural tourist attractions. Shopping and dining experiences offer a wide range of choices and prices. The city is also famous for its dynamic nightlife. Although Bangkok’s sex tourism scene is well known to foreigners, it is usually not openly acknowledged by locals or the government.

Khao San Road is lined by budget accommodation, shops and bars catering to tourists.

Among Bangkok’s well-known sights are the Grand Palace and major Buddhist temples, including Wat Phra Kaew, Wat Pho, and Wat Arun. The Giant Swing and Erawan Shrine demonstrate Hinduism’s deep-rooted influence in Thai culture. Vimanmek Mansion in Dusit Palace is famous as the world’s largest teak building, while the Jim Thompson House provides an example of traditional Thai architecture. Other major museums include the Bangkok National Museum and the Royal Barge National Museum. Cruises and boat trips on the Chao Phraya and the canals of Thonburi offer views of some of the city’s traditional architecture and ways of life on the waterfront.[106]

Shopping venues, many of which are popular with both tourists and locals, range from the shopping centres and department stores concentrated in Siam and Ratchaprasong to the sprawling Chatuchak Weekend Market. Taling Chan Floating Market is among the few such markets in Bangkok. Yaowarat is known for its shops as well as street-side food stalls and restaurants, which are also found throughout the city. Khao San Road has long been famous as a destination for backpacker tourism, with its budget accommodation, shops and bars attracting visitors from all over the world.

Bangkok has a reputation overseas as a major destination in the sex industry. Although prostitution is technically illegal and is rarely openly discussed in Thailand, it commonly takes place among massage parlours, saunas and hourly hotels, serving foreign tourists as well as locals. Bangkok has acquired the nickname «Sin City of Asia» for its level of sex tourism.[107]

Issues often encountered by foreign tourists include scams, overcharging and dual pricing. In a survey of 616 tourists visiting Thailand, 7.79 percent reported encountering a scam, the most common of which was the gem scam, in which tourists are tricked into buying overpriced jewellery.[108]

Among Bangkok’s well-known sights

Culture[edit]

The culture of Bangkok reflects its position as Thailand’s centre of wealth and modernisation. The city has long been the portal of entry of Western concepts and material goods, which have been adopted and blended with Thai values to various degrees by its residents. This is most evident in the lifestyles of the expanding middle class. Conspicuous consumption serves as a display of economic and social status, and shopping centres are popular weekend hangouts.[109] Ownership of electronics and consumer products such as mobile phones is ubiquitous. This has been accompanied by a degree of secularism, as religion’s role in everyday life has rather diminished. Although such trends have spread to other urban centres, and, to a degree, the countryside, Bangkok remains at the forefront of social change.

A distinct feature of Bangkok is the ubiquity of street vendors selling goods ranging from food items to clothing and accessories. It has been estimated that the city may have over 100,000 hawkers. While the BMA has authorised the practice in 287 sites, the majority of activity in another 407 sites takes place illegally. Although they take up pavement space and block pedestrian traffic, many of the city’s residents depend on these vendors for their meals, and the BMA’s efforts to curb their numbers have largely been unsuccessful.[110]

In 2015, however, the BMA, with support from the National Council for Peace and Order (Thailand’s ruling military junta), began cracking down on street vendors in a bid to reclaim public space. Many famous market neighbourhoods were affected, including Khlong Thom, Saphan Lek, and the flower market at Pak Khlong Talat. Nearly 15,000 vendors were evicted from 39 public areas in 2016.[111] While some applauded the efforts to focus on pedestrian rights, others have expressed concern that gentrification would lead to the loss of the city’s character and adverse changes to people’s way of life.[112][113]

Festivals and events[edit]

The residents of Bangkok celebrate many of Thailand’s annual festivals. During Songkran on 13–15 April, traditional rituals as well as water fights take place throughout the city. Loi Krathong, usually in November, is accompanied by the Golden Mount Fair. New Year celebrations take place at many venues, the most prominent being the plaza in front of CentralWorld. Observances related to the royal family are held primarily in Bangkok. Wreaths are laid at King Chulalongkorn’s equestrian statue in the Royal Plaza on 23 October, which is King Chulalongkorn Memorial Day. The present king’s and queen’s birthdays, respectively on 5 December and 12 August, are marked as Thailand’s national Father’s Day and national Mother’s Day. These national holidays are celebrated by royal audiences on the day’s eve, in which the king or queen gives a speech, and public gatherings on the day of the observance. The king’s birthday is also marked by the Royal Guards’ parade.

Sanam Luang is the site of the Thai Kite, Sport and Music Festival, usually held in March, and the Royal Ploughing Ceremony which takes place in May. The Red Cross Fair at the beginning of April is held at Suan Amporn and the Royal Plaza, and features numerous booths offering goods, games and exhibits. The Chinese New Year (January–February) and Vegetarian Festival (September–October) are celebrated widely by the Chinese community, especially in Yaowarat.[114]

Bangkok was designated as the World Book Capital for the year 2013 by UNESCO.[115]

Bangkok’s first Thai International Gay Pride Festival took place on October 31, 1999.[116] Pride Parades have also been held in Bangkok, with the first official parade held in 2022 under the name «Bangkok Naruemit Pride Parade». Pride Parades were announced to be a part of Bangkok’s «12 monthly festivals» in 2022.[117]

Media[edit]

Bangkok is the centre of Thailand’s media industry. All national newspapers, broadcast media and major publishers are based in the capital. Its 21 national newspapers had a combined daily circulation of about two million in 2002. These include the mass-oriented Thai Rath, Khao Sod and Daily News, the first of which currently prints a million copies per day,[118] as well as the less sensational Matichon and Krungthep Thurakij. The Bangkok Post and The Nation are the two national English language dailies. Foreign publications including The Asian Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, The Straits Times and the Yomiuri Shimbun also have operations in Bangkok.[119] The large majority of Thailand’s more than 200 magazines are published in the capital, and include news magazines as well as lifestyle, entertainment, gossip and fashion-related publications.

Bangkok is also the hub of Thailand’s broadcast television. All six national terrestrial channels, Channels 3, 5 and 7, Modernine, NBT and Thai PBS, have headquarters and main studios in the capital. GMM Grammy is Thailand’s largest mass-media conglomerate is also headquartered in Bangkok as well. With the exception of local news segments broadcast by the NBT, all programming is done in Bangkok and repeated throughout the provinces. However, this centralised model is weakening with the rise of cable television, which has many local providers. There are numerous cable and satellite channels based in Bangkok. TrueVisions is the major subscription television provider in Bangkok and Thailand, and it also carries international programming. Bangkok was home to 40 of Thailand’s 311 FM radio stations and 38 of its 212 AM stations in 2002.[119] Broadcast media reform stipulated by the 1997 Constitution has been progressing slowly, although many community radio stations have emerged in the city.

Likewise, Bangkok has dominated the Thai film industry since its inception. Although film settings normally feature locations throughout the country, the city is home to all major film studios in Thailand such as GDH 559 (GMM Grammy’s film production subsidiary), Sahamongkol Film International and Five Star Production. Bangkok has dozens of cinemas and multiplexes, and the city hosts two major film festivals annually, the Bangkok International Film Festival and the World Film Festival of Bangkok.

Art[edit]

Traditional Thai art, long developed within religious and royal contexts, continues to be sponsored by various government agencies in Bangkok, including the Department of Fine Arts’ Office of Traditional Arts. The SUPPORT Foundation in Chitralada Palace sponsors traditional and folk handicrafts. Various communities throughout the city still practice their traditional crafts, including the production of khon masks, alms bowls, and classical musical instruments. The National Gallery hosts permanent collection of traditional and modern art, with temporary contemporary exhibits. Bangkok’s contemporary art scene has slowly grown from relative obscurity into the public sphere over the past two decades. Private galleries gradually emerged to provide exposure for new artists, including the Patravadi Theatre and H Gallery. The centrally located Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, opened in 2008 following a fifteen-year lobbying campaign, is now the largest public exhibition space in the city.[120] There are also many other art galleries and museums, including the privately owned Museum of Contemporary Art.

The city’s performing arts scene features traditional theatre and dance as well as Western-style plays. Khon and other traditional dances are regularly performed at the National Theatre and Salachalermkrung Royal Theatre, while the Thailand Cultural Centre is a newer multi-purpose venue which also hosts musicals, orchestras and other events. Numerous venues regularly feature a variety of performances throughout the city.

Sport[edit]

As is the national trend, association football and Muay Thai dominate Bangkok’s spectator sport scene.[121] Muangthong United, Bangkok United, BG Pathum United, Port and Police Tero are major Thai League clubs based in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region,[122][123] while the Rajadamnern and Lumpini stadiums are the main kickboxing venues.

While sepak takraw can be seen played in open spaces throughout the city, football and other modern sports are now the norm. Western sports introduced during the reign of King Chulalongkorn were originally only available to the privileged, and such status is still associated with certain sports. Golf is popular among the upwardly mobile, and there are several courses in Bangkok. Horse racing, highly popular at the mid-20th century, still takes place at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club.

There are many public sporting facilities located throughout Bangkok. The two main centres are the National Stadium complex, which dates to 1938, and the newer Hua Mak Sports Complex, which was built for the 1998 Asian Games. Bangkok had also hosted the games in 1966, 1970 and 1978; the most of any city. The city was the host of the inaugural Southeast Asian Games in 1959, the 2007 Summer Universiade and the 2012 FIFA Futsal World Cup.

Transport[edit]

Streetlamps and headlights illuminate the Makkasan Interchange of the expressway. The system sees a traffic of over 1.5 million vehicles per day.[124]

Although Bangkok’s canals historically served as a major mode of transport, they have long since been surpassed in importance by land traffic. Charoen Krung Road, the first to be built by Western techniques, was completed in 1864. Since then, the road network has vastly expanded to accommodate the sprawling city. A complex elevated expressway network and Don Mueang Tollway helps bring traffic into and out of the city centre, but Bangkok’s rapid growth has put a large strain on infrastructure, and traffic jams have plagued the city since the 1990s. Although rail transport was introduced in 1893 and trams served the city from 1888 to 1968, it was only in 1999 that Bangkok’s first rapid transit system began operation. Older public transport systems include an extensive bus network and boat services which still operate on the Chao Phraya and two canals. Taxis appear in the form of cars, motorcycles, and «tuk-tuk» auto rickshaws.

Bangkok is connected to the rest of the country through the national highway and rail networks, as well as by domestic flights to and from the city’s two international airports. Its centuries-old maritime transport of goods is still conducted through Khlong Toei Port.

The BMA is largely responsible for overseeing the construction and maintenance of the road network and transport systems through its Public Works Department and Traffic and Transportation Department. However, many separate government agencies are also in charge of the individual systems, and much of transport-related policy planning and funding is contributed to by the national government.

Roads[edit]

Road-based transport is the primary mode of travel in Bangkok. Due to the city’s organic development, its streets do not follow an organized grid structure. Forty-eight major roads link the different areas of the city, branching into smaller streets and lanes (soi) which serve local neighbourhoods. Eleven bridges over the Chao Phraya link the two sides of the city, while several expressway and motorway routes bring traffic into and out of the city centre and link with nearby provinces.

Bangkok’s rapid growth in the 1980s resulted in sharp increases in vehicle ownership and traffic demand, which have since continued—in 2006 there were 3,943,211 in-use vehicles in Bangkok, of which 37.6 percent were private cars and 32.9 percent were motorcycles.[125] These increases, in the face of limited carrying capacity, caused severe traffic congestion evident by the early 1990s. The extent of the problem is such that the Thai Traffic Police has a unit of officers trained in basic midwifery in order to assist deliveries which do not reach hospital in time.[126] While Bangkok’s limited road surface area (8 percent, compared to 20–30 percent in most Western cities) is often cited as a major cause of its traffic jams, other factors, including high vehicle ownership rate relative to income level, inadequate public transport systems, and lack of transportation demand management, also play a role.[127] Efforts to alleviate the problem have included the construction of intersection bypasses and an extensive system of elevated highways, as well as the creation of several new rapid transit systems. The city’s overall traffic conditions, however, remain poor.

Traffic has been the main source of air pollution in Bangkok, which reached serious levels in the 1990s. But efforts to improve air quality by improving fuel quality and enforcing emission standards, among others, had visibly ameliorated the problem by the 2000s. Atmospheric particulate matter levels dropped from 81 micrograms per cubic metre in 1997 to 43 in 2007.[128] However, increasing vehicle numbers and a lack of continued pollution-control efforts threatens a reversal of the past success.[129] In January–February 2018, weather conditions caused bouts of haze to cover the city, with particulate matter under 2.5 micrometres (PM2.5) rising to unhealthy levels for several days on end.[130][131]

Although the BMA has created thirty signed bicycle routes along several roads totalling 230 kilometres (140 mi),[132] cycling is still largely impractical, especially in the city centre. Most of these bicycle lanes share the pavement with pedestrians. Poor surface maintenance, encroachment by hawkers and street vendors, and a hostile environment for cyclists and pedestrians, make cycling and walking unpopular methods of getting around in Bangkok.

Buses and taxis[edit]

Many buses, minibuses and taxis share the streets with private vehicles at Victory Monument, a major public transport hub.

Bangkok has an extensive bus network providing local transit services within the Greater Bangkok area. The Bangkok Mass Transit Authority (BMTA) operates a monopoly on bus services, with substantial concessions granted to private operators. Buses, minibus vans, and song thaeo operate on a total of 470 routes throughout the region.[133] A separate bus rapid transit system owned by the BMA has been in operation since 2010. Known simply as the BRT, the system currently consists of a single line running from the business district at Sathon to Ratchaphruek on the western side of the city. The Transport Co., Ltd. is the BMTA’s long-distance counterpart, with services to all provinces operating out of Bangkok.

Taxis are ubiquitous in Bangkok, and are a popular form of transport. As of August 2012, there are 106,050 cars, 58,276 motorcycles and 8,996 tuk-tuk motorized tricycles cumulatively registered for use as taxis.[134] Meters have been required for car taxis since 1992, while tuk-tuk fares are usually negotiated. Motorcycle taxis operate from regulated ranks, with either fixed or negotiable fares, and are usually employed for relatively short journeys.

Despite their popularity, taxis have gained a bad reputation for often refusing passengers when the requested route is not to the driver’s convenience.[135] Motorcycle taxis were previously unregulated, and subject to extortion by organized crime gangs. Since 2003, registration has been required for motorcycle taxi ranks, and drivers now wear distinctive numbered vests designating their district of registration and where they are allowed to accept passengers.

Several ride hailing super-apps operate within the city, including Grab (offering car and motorbike options),[136] and AirAsia in 2022.[137][138] The Estonian company Bolt launched airport transfer and ride hailing services in 2020. Ride sharing startup MuvMi launched in 2018, and operates an electric tuk-tuk service in 9 areas across the city.[139][140]

Rail systems[edit]

Bangkok is the location of Hua Lamphong Railway Station, the main terminus of the national rail network operated by the State Railway of Thailand (SRT). In addition to long-distance services, the SRT also operates a few daily commuter trains running from and to the outskirts of the city during the rush hour.

Bangkok is served by four rapid transit systems: the BTS Skytrain, the MRT, the SRT Red Lines, and the elevated Airport Rail Link. Although proposals for the development of rapid transit in Bangkok had been made since 1975,[141] it was only in 1999 that the BTS finally began operation.

The BTS consists of two lines, Sukhumvit and Silom, with 59 stations along 68.25 kilometres (42.41 mi).[142] The MRT opened for use in July 2004, and currently consists of two lines, the Blue Line and Purple Line with 53 stations along 70.6 kilometres (43.9 mi). The Airport Rail Link, opened in August 2010, connects the city centre to Suvarnabhumi Airport to the east. Its eight stations span a distance of 28.6 kilometres (17.8 mi). The SRT Red Lines (Commuter) opened in 2021, and consists of two lines, The SRT Dark Red Line and SRT Light Red Line with currently 14 stations along 41 kilometres (25 mi).

Although initial passenger numbers were low and their service area was limited to the inner city until the 2016 opening of the Purple Line, which serves the Nonthaburi area, these systems have become indispensable to many commuters. The BTS reported an average of 600,000 daily trips in 2012,[143] while the MRT had 240,000 passenger trips per day.[144]

As of September 2020, construction work is ongoing to extend the city-wide transit system’s reach, including the construction of the Light Red grade-separated commuter rail line. The entire Mass Rapid Transit Master Plan in Bangkok Metropolitan Region consists of eight main lines and four feeder lines totaling 508 kilometres (316 mi) to be completed by 2029. In addition to rapid transit and heavy rail lines, there have been proposals for several monorail systems.

Water transport[edit]

Although much diminished from its past prominence, water-based transport still plays an important role in Bangkok and the immediate upstream and downstream provinces. Several water buses serve commuters daily. The Chao Phraya Express Boat serves thirty-four stops along the river, carrying an average of 35,586 passengers per day in 2010, while the smaller Khlong Saen Saep boat service serves twenty-seven stops on Saen Saep Canal with 57,557 daily passengers. Long-tail boats operate on fifteen regular routes on the Chao Phraya, and passenger ferries at thirty-two river crossings served an average of 136,927 daily passengers in 2010.[145]

Bangkok Port, popularly known by its location as Khlong Toei Port, was Thailand’s main international port from its opening in 1947 until it was superseded by the deep-sea Laem Chabang Port in 1991. It is primarily a cargo port, though its inland location limits access to ships of 12,000 deadweight tonnes or less. The port handled 11,936,855 tonnes (13,158,130 tons) of cargo in the first eight months of the 2010 fiscal year, about 22 percent the total of the country’s international ports.[146][147]

Airports[edit]

Bangkok is one of Asia’s busiest air transport hubs. Two commercial airports serve the city, the older Don Mueang International Airport and the newer Suvarnabhumi Airport. Suvarnabhumi, which replaced Don Mueang as Bangkok’s main airport after its opening in 2006, served 52,808,013 passengers in 2015,[148] making it the world’s 20th busiest airport by passenger volume. This volume exceeded its designed capacity of 45 million passengers. Don Mueang reopened for domestic flights in 2007,[149] and resumed international service focusing on low-cost carriers in October 2012.[150] Suvarnabhumi is undergoing expansion to increase its capacity to 60 million passengers by 2019 and 90 million by 2021.[151]

Health and education[edit]

Education[edit]

Bangkok has long been the centre of modern education in Thailand. The first schools in the country were established here in the later 19th century, and there are now 1,351 schools in the city.[152] The city is home to the country’s five oldest universities, Chulalongkorn, Thammasat, Kasetsart, Mahidol and Silpakorn, founded between 1917 and 1943. The city has since continued its dominance, especially in higher education; the majority of the country’s universities, both public and private, are located in Bangkok or the Metropolitan Region. Chulalongkorn and Mahidol are the only Thai universities to appear in the top 500 of the QS World University Rankings.[153] King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, also located in Bangkok, is the only Thai university in the top 400 of the 2012–13 Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[154]

Over the past few decades the general trend of pursuing a university degree has prompted the founding of new universities to meet the needs of Thai students. Bangkok became not only a place where immigrants and provincial Thais go for job opportunities, but also for a chance to receive a university degree. Ramkhamhaeng University emerged in 1971 as Thailand’s first open university; it now has the highest enrolment in the country. The demand for higher education has led to the founding of many other universities and colleges, both public and private. While many universities have been established in major provinces, the Greater Bangkok region remains home to the greater majority of institutions, and the city’s tertiary education scene remains over-populated with non-Bangkokians. The situation is not limited to higher education, either. In the 1960s, 60 to 70 percent of 10- to 19-year-olds who were in school had migrated to Bangkok for secondary education. This was due to both a lack of secondary schools in the provinces and perceived higher standards of education in the capital.[155] Although this discrepancy has since largely abated, tens of thousands of students still compete for places in Bangkok’s leading schools. Education has long been a prime factor in the centralization of Bangkok and will play a vital role in the government’s efforts to decentralize the country.

Healthcare[edit]

Much of Thailand’s medical resources are disproportionately concentrated in the capital. In 2000, Bangkok had 39.6 percent of the country’s doctors and a physician-to-population ratio of 1:794, compared to a median of 1:5,667 among all provinces.[156] The city is home to 42 public hospitals, five of which are university hospitals, as well as 98 private hospitals and 4,063 registered clinics.[dead link][157] The BMA operates nine public hospitals through its Medical Service Department, and its Health Department provides primary care through sixty-eight community health centres. Thailand’s universal healthcare system is implemented through public hospitals and health centres as well as participating private providers.

Research-oriented medical school affiliates such as Siriraj, King Chulalongkorn Memorial and Ramathibodi Hospitals are among the largest in the country, and act as tertiary care centres, receiving referrals from distant parts of the country. Lately, especially in the private sector, there has been much growth in medical tourism, with hospitals such as Bumrungrad and Bangkok Hospital, among others, providing services specifically catering to foreigners. An estimated 200,000 medical tourists visited Thailand in 2011, making Bangkok the most popular global destination for medical tourism.[158]

Crime and safety[edit]

Bangkok has a relatively moderate crime rate when compared to urban counterparts around the world.[159] Traffic accidents are a major hazard[160] while natural disasters are rare. Intermittent episodes of political unrest and occasional terrorist attacks have resulted in losses of life.

Although the crime threat in Bangkok is relatively low, non-confrontational crimes of opportunity such as pick-pocketing, purse-snatching, and credit card fraud occur with frequency.[159] Bangkok’s growth since the 1960s has been followed by increasing crime rates partly driven by urbanisation, migration, unemployment and poverty. By the late 1980s, Bangkok’s crime rates were about four times that of the rest of the country. The police have long been preoccupied with street crimes ranging from housebreaking to assault and murder.[161] The 1990s saw the emergence of vehicle theft and organized crime, particularly by foreign gangs.[162] Drug trafficking, especially that of ya ba methamphetamine pills, is also chronic.[163][164]

According to police statistics, the most common complaint received by the Metropolitan Police Bureau in 2010 was housebreaking, with 12,347 cases. This was followed by 5,504 cases of motorcycle thefts, 3,694 cases of assault and 2,836 cases of embezzlement. Serious offences included 183 murders, 81 gang robberies, 265 robberies, 1 kidnapping and 9 arson cases. Offences against the state were by far more common, and included 54,068 drug-related cases, 17,239 cases involving prostitution and 8,634 related to gambling.[165] The Thailand Crime Victim Survey conducted by the Office of Justice Affairs of the Ministry of Justice found that 2.7 percent of surveyed households reported a member being victim of a crime in 2007. Of these, 96.1 percent were crimes against property, 2.6 percent were crimes against life and body, and 1.4 percent were information-related crimes.[166]

Political demonstrations and protests are common in Bangkok. The historic uprisings of 1973, 1976 and 1992 are infamously known for the deaths from military suppression. Most events since then have been peaceful, but the series of major protests since 2006 have often turned violent. Demonstrations during March–May 2010 ended in a crackdown in which 92 were killed, including armed and unarmed protesters, security forces, civilians and journalists. Terrorist incidents have also occurred in Bangkok, most notably the bombing in 2015 at the Erawan shrine, which killed 20, and also a series of bombings on the 2006–07 New Year’s Eve.

Traffic accidents are a major hazard in Bangkok. There were 37,985 accidents in the city in 2010, resulting in 16,602 injuries and 456 deaths as well as 426.42 million baht in damages. However, the rate of fatal accidents is much lower than in the rest of Thailand. While accidents in Bangkok amounted to 50.9 percent of the entire country, only 6.2 percent of fatalities occurred in the city.[167] Another serious public health hazard comes from Bangkok’s stray dogs. Up to 300,000 strays are estimated to roam the city’s streets,[168] and dog bites are among the most common injuries treated in the emergency departments of the city’s hospitals. Rabies is prevalent among the dog population, and treatment for bites pose a heavy public burden.[l]

Calls to move the capital[edit]

Bangkok is faced with multiple problems—including congestion, and especially subsidence and flooding—which have raised the issue of moving the nation’s capital elsewhere. The idea is not new: during World War II Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram planned unsuccessfully to relocate the capital to Phetchabun. In the 2000s, the Thaksin Shinawatra administration assigned the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) to formulate a plan to move the capital to Nakhon Nayok province. The 2011 floods revived the idea of moving government functions from Bangkok. In 2017, the military government assigned NESDC to study the possibility of moving government offices from Bangkok to Chachoengsao province in the east.[170][171][172]

International relations[edit]

Protesters in front of the United Nations Building during the 2009 Bangkok Climate Change Conference. Bangkok is home to several UN offices.

The city’s formal international relations are managed by the International Affairs Division of the BMA. Its missions include partnering with other major cities through sister city or friendship agreements, participation and membership in international organizations, and pursuing cooperative activities with the many foreign diplomatic missions based in the city.[173]

International participation[edit]

Bangkok is a member of several international organizations and regional city government networks, including the Asian Network of Major Cities 21, the Japan-led Asian-Pacific City Summit, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, the ESCAP-sponsored Regional Network of Local Authorities for Management of Human Settlements in Asia and Pacific (CITYNET), Japan’s Council of Local Authorities for International Relations, the World Association of the Major Metropolises and Local Governments for Sustainability, among others.[173]

With its location at the heart of mainland Southeast Asia and as one of Asia’s hubs of transportation, Bangkok is home to many international and regional organizations. Among others, Bangkok is the seat of the Secretariat of the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), as well as the Asia-Pacific regional offices of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), and the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF).[174]

City partnerships[edit]

Bangkok has made sister city or friendship agreements with:[175]

Aichi Prefecture, Japan (2012)[176]

Ankara, Turkey (2012)[177]

Astana, Kazakhstan (2004)[178]

Beijing, China (1993)[179]

Brisbane, Australia (1997)[180]

Budapest, Hungary (1997)[181]

Busan, South Korea (2011)[182]

Chaozhou, China (2005)[183][184]

Chengdu, China (2017)[185]

Chongqing, China (2011)[186]

Daegu, South Korea (2017)[187]

Dalian, China (2016)[188]

Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan (2006)[189]

Guangzhou, China (2009)[190][191]

Hanoi, Vietnam (2004)[192]

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (2015)[193]

Huế, Vietnam (2016)[194]

Jakarta, Indonesia (2002)[195]

Lausanne, Switzerland (2009)[196]

Lisbon, Portugal (2016)[197]

Manila, Philippines (1997)[198][199]

Moscow, Russia (1997)[200]

Penang Island, Malaysia (2012)[201]

Porto, Portugal (2016)[202]

Phnom Penh, Cambodia (2013)[203]

Saint Petersburg, Russia (1997)[204][205]

Seoul, South Korea (2006)[206]

Shandong, China (2013)[207]

Shanghai, China (2012)[208]

Shenzhen, China (2015)[209]

Tehran, Iran (2012)[210]

Tianjin, China (2012)[211]

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (2017)[212]

Vientiane, Laos (2004)[213]

Washington, D.C., United States (1962, 2002)[214][215]

Wuhan, China (2013)[216]

See also[edit]

- Outline of Bangkok

- Thai people

- World’s largest cities

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ ,[6][7] [7][8]

- ^ กรุงเทพมหานคร, pronounced [krūŋ tʰêːp mahǎː nákʰɔ̄ːn] (

listen), where the phrase «Maha Nakhon» literally translates to «large (or great) city»

- ^

Thai pronunciation (help·info)

- ^ Two plants are known in Thai by the name makok: E. hygrophilus (makok nam, ‘water makok‘) and Spondias pinnata (makok pa, ‘jungle makok‘). The species that grew in the area was likely makok nam.

- ^ While this ceremonial name is generally believed, based on writings by the Somdet Phra Wannarat (Kaeo), to have originally been given by King Rama I and later modified by King Mongkut, it did not come into use until the latter reign.[16]

- ^ This ceremonial name uses two ancient Indian languages, Pāli and Sanskrit, prefaced with the only one Thai word, Krung, which means ‘capital’. According to the romanisation of these languages, it can actually be written as Krung-dēva mahā nagara amara ratanakosindra mah indr āyudhyā mahā tilaka bhava nava ratana rāja dhānī purī ramya uttama rājanivēsana mah āsthāna amara vimāna avatāra sthitya shakrasdattiya viṣṇu karma prasiddhi

(listen) (help·info).

- ^ In contrast to the 169-letter-long transcription provided above in this article, the form recorded in the Guinness World Records is missing the first letter «h» in Amonphimanawatansathit, resulting in a word 168 letters long.

- ^ The BMA gives an elevation figure of 2.31 metres (7 ft 7 in).[1]

- ^ Thai ethnicity is rather a question of cultural identity than of genetic origin.[79] Many people in Bangkok who self-identify as Thai have at least some Chinese ancestry.[80]

- ^ An introductory publication by the BMA gives a figure of 80 percent Thai, 10 percent Chinese and 10 percent other, although this is likely a rough estimate.[81]

- ^ By one recent estimate, at least 60 percent of the city’s residents are of Chinese descent.[83]

- ^ A 1993 study found dog bites to constitute 5.3 percent of injuries seen at Siriraj Hospital’s emergency department.[169]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Thavisin et al. (eds) 2006, p. 24. Reproduced in «Geography of Bangkok». BMA website. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ a b Tangchonlatip, Kanchana (2007). «กรุงเทพมหานคร: เมืองโตเดี่ยวตลอดกาลของประเทศไทย» [Bangkok: Thailand’s forever primate city]. In Thongthai, Varachai; Punpuing, Sureeporn (eds.). ประชากรและสังคม 2550 [Population and society 2007]. Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Institute for Population and Social Research. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ a b Sinsakul, Sin (August 2000). «Late Quaternary geology of the Lower Central Plain, Thailand». Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 18 (4): 415–426. Bibcode:2000JAESc..18..415S. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(99)00075-9.

- ^ a b c d «Table 1 Population by sex, household by type of household, changwat and area» (PDF). The 2010 Population and Housing Census: Whole Kingdom. popcensus.nso.go.th. National Statistical Office. 2012. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ a b «Thailand». The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ «Bangkok». British and World English Dictionary. Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ a b «Definition of «Bangkok»«. Collins English Dictionary (online). HarperCollins. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ «Bangkok». US English Dictionary. Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.