Версия для печати

Отправить ссылку

Как правильно: Мюнхаузен или Мюнхгаузен?

5 октября 2016 11:37

Администрация города Екатеринбурга в рамках проекта «Екатеринбург говорит правильно» обращается к вопросу о корректности написания фамилии: «Мюнхаузен» или «Мюнхгаузен».

По данным справочно-информационного портала «Русский язык», оба варианта зафиксированы словарями русского языка и энциклопедиями. Написание «Мюнхгаузен» соответствует правилам передачи немецких имен собственных на русский язык: буквосочетание chh (Münchhausen) передается на русский язык как «хг».

Вариант «Мюнхаузен» — традиционный для русского языка, вошедший в культуру благодаря переводам К. И. Чуковского, который именно так передал фамилию барона.

Таким образом, правильно: как говорил барон Мюнхаузен (и Мюнхгаузен), улыбайтесь, господа, улыбайтесь.

Фото www.yandex.ru

Ключевые слова:

русский язык

Комментариев пока нет Написать?

Материалы по теме

|

Как правильно: цифры рознятся или разнятся? 12 октября 2016 11:54 |

|

Как попросить счет в заведении общепита: посчитайте или рассчитайте нас? 11 октября 2016 11:22 |

|

Как правильно: подвигнуть к подвигу или на подвиг? 10 октября 2016 11:49 |

|

Как правильно: полигрАфия или полиграфИя? 7 октября 2016 11:39 |

|

Как правильно: олЕнина или оленИна? 6 октября 2016 12:17 |

|

Как правильно: маркИрованный или маркирОванный список? 4 октября 2016 11:27 |

|

Как правильно: скрепя сердце, скрепя сердцем или скрепив сердце? 3 октября 2016 11:25 |

|

Как правильно: отдавать отчет в своих действиях или своим действиям? 30 сентября 2016 11:20 |

|

Как правильно: активировать или активизировать деятельность? 29 сентября 2016 12:03 |

|

Как правильно: идентичный чему или идентичный с чем? 28 сентября 2016 11:15 |

This article is about the literary character. For other uses, see Münchhausen.

| Baron Munchausen | |

|---|---|

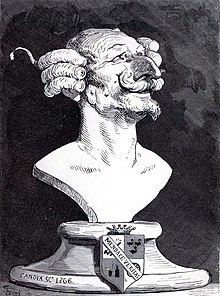

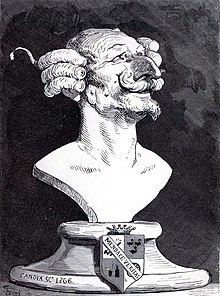

Gustave Doré’s portrait of Baron Munchausen |

|

| First appearance | Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia (1785) |

| Created by | Rudolf Erich Raspe |

| Portrayed by |

|

| Voiced by |

|

| Based on | Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen (1720–1797) |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | Lügenbaron («Baron of Lies») |

| Title | Baron |

| Nationality | German |

Baron Munchausen (;[1][2][a] German: [ˈmʏnçˌhaʊzn̩]) is a fictional German nobleman created by the German writer Rudolf Erich Raspe in his 1785 book Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. The character is loosely based on a real baron, Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen.

Born in Bodenwerder, Electorate of Hanover, the real-life Münchhausen fought for the Russian Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739. Upon retiring in 1760, he became a minor celebrity within German aristocratic circles for telling outrageous tall tales based on his military career. After hearing some of Münchhausen’s stories, Raspe adapted them anonymously into literary form, first in German as ephemeral magazine pieces and then in English as the 1785 book, which was first published in Oxford by a bookseller named Smith. The book was soon translated into other European languages, including a German version expanded by the poet Gottfried August Bürger. The real-life Münchhausen was deeply upset at the development of a fictional character bearing his name, and threatened legal proceedings against the book’s publisher. Perhaps fearing a libel suit, Raspe never acknowledged his authorship of the work, which was only established posthumously.

The fictional Baron’s exploits, narrated in the first person, focus on his impossible achievements as a sportsman, soldier, and traveller; for instance: riding on a cannonball, fighting a forty-foot crocodile, and travelling to the Moon. Intentionally comedic, the stories play on the absurdity and inconsistency of Munchausen’s claims, and contain an undercurrent of social satire. The earliest illustrations of the character, perhaps created by Raspe himself, depict Munchausen as slim and youthful, although later illustrators have depicted him as an older man, and have added the sharply beaked nose and twirled moustache that have become part of the character’s definitive visual representation. Raspe’s book was a major international success, becoming the core text for numerous English, continental European, and American editions that were expanded and rewritten by other writers. The book in its various revised forms remained widely read throughout the 19th century, especially in editions for young readers.

Versions of the fictional Baron have appeared on stage, screen, radio, and television, as well as in other literary works. Though the Baron Munchausen stories are no longer well-known in many English-speaking countries, they are still popular in continental Europe. The character has inspired numerous memorials and museums, and several medical conditions and other concepts are named after him.

Historical figure[edit]

The real-life Münchhausen circa 1740, as a cuirassier in Riga, by G. Bruckner

Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen was born on 11 May 1720 in Bodenwerder, Electorate of Hanover.[5] He was a younger son of the «Black Line» of Rinteln-Bodenwerder, an aristocratic family in the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg.[6] His cousin, Gerlach Adolph von Münchhausen,[7] was the founder of the University of Göttingen and later the Prime Minister of the Electorate of Hanover.[8] Münchhausen started as a page to Anthony Ulrich II of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and followed his employer to the Russian Empire during the Russo-Austro–Turkish War (1735–39).[5] In 1739, he was appointed a cornet in the Russian cavalry regiment, the Brunswick-Cuirassiers.[5] On 27 November 1740, he was promoted to lieutenant.[6] He was stationed in Riga, but participated in two campaigns against the Turks in 1740 and 1741. In 1744 he married Jacobine von Dunten, and in 1750 he was promoted to Rittmeister (cavalry captain).[5]

In 1760 Münchhausen retired to live as a Freiherr at his estates in Bodenwerder, where he remained until his death in 1797.[5][9] It was there, especially at parties given for the area’s aristocrats, that he developed a reputation as an imaginative after-dinner storyteller, creating witty and highly exaggerated accounts of his adventures in Russia. Over the ensuing thirty years, his storytelling abilities gained such renown that he frequently received visits from travelling nobles wanting to hear his tales.[10] One guest described Münchhausen as telling his stories «cavalierly, indeed with military emphasis, yet without any concession to the whimsicality of the man of the world; describing his adventures as one would incidents which were in the natural course of events».[11] Rather than being considered a liar, Münchhausen was seen as an honest man.[5] As another contemporary put it, Münchhausen’s unbelievable narratives were designed not to deceive, but «to ridicule the disposition for the marvellous which he observed in some of his acquaintances».[12]

Münchhausen’s wife Jacobine von Dunten died in 1790.[13] In January 1794, Münchhausen married Bernardine von Brunn, fifty-seven years his junior.[13] Von Brunn reportedly took ill soon after the marriage and spent the summer of 1794 in the spa town of Bad Pyrmont, although contemporary gossip claimed that she spent her time dancing and flirting.[13] Von Brunn gave birth to a daughter, Maria Wilhemina, on 16 February 1795, nine months after her summer trip. Münchhausen filed an official complaint that the child was not his, and spent the last years of his life in divorce proceedings and alimony litigation.[13] Münchhausen died childless on 22 February 1797.[5]

Fictionalization[edit]

The Baron entertaining guests, from a series of postcards by Oskar Herrfurth.

The fictionalized character was created by a German writer, scientist, and con artist, Rudolf Erich Raspe.[14][15] Raspe probably met Hieronymus von Münchhausen while studying at the University of Göttingen,[7] and may even have been invited to dine with him at the mansion at Bodenwerder.[14] Raspe’s later career mixed writing and scientific scholarship with theft and swindling; when the German police issued advertisements for his arrest in 1775, he fled continental Europe and settled in England.[16]

In his native German language, Raspe wrote a collection of anecdotes inspired by Münchhausen’s tales, calling the collection «M-h-s-nsche Geschichten» («M-h-s-n Stories»).[17] It remains unclear how much of Raspe’s material comes directly from the Baron, but the majority of the stories are derived from older sources,[18] including Heinrich Bebel’s Facetiæ (1508) and Samuel Gotthold Lange’s Deliciæ Academicæ (1765).[19] «M-h-s-nsche Geschichten» appeared as a feature in the eighth issue of the Vade mecum für lustige Leute (Handbook for Fun-loving People), a Berlin humor magazine, in 1781. Raspe published a sequel, «Noch zwei M-Lügen» («Two more M-Fibs»), in the tenth issue of the same magazine in 1783.[17] The hero and narrator of these stories was identified only as «M-h-s-n», keeping Raspe’s inspiration partly obscured while still allowing knowledgeable German readers to make the connection to Münchhausen.[20] Raspe’s name did not appear at all.[17]

In 1785, while supervising mines at Dolcoath in Cornwall, Raspe adapted the Vade mecum anecdotes into a short English-language book, this time identifying the narrator of the book as «Baron Munchausen».[21] Other than the anglicization of Münchhausen to «Munchausen», Raspe this time made no attempt to hide the identity of the man who had inspired him, though he still withheld his own name.[22]

Portrait of Rudolf Erich Raspe, creator of the fictional Baron

This English edition, the first version of the text in which Munchausen appeared as a fully developed literary character,[23] had a circuitous publication history. It first appeared anonymously as Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, a 49-page book in 12mo size, published in Oxford by the bookseller Smith in late 1785 and sold for a shilling.[24] A second edition released early the following year, retitled Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Sporting Adventures of Baron Munnikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen, added five more stories and four illustrations; though the book was still anonymous, the new text was probably by Raspe, and the illustrations may have been his work as well.[25]

By May 1786, Raspe no longer had control over the book, which was taken over by a different publisher, G. Kearsley.[26][b] Kearsley, intending the book for a higher-class audience than the original editions had been, commissioned extensive additions and revisions from other hands, including new stories, twelve new engravings, and much rewriting of Raspe’s prose. This third edition was sold at two shillings, twice the price of the original, as Gulliver Revived, or the Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures of Baron Munikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen.[27]

Kearsley’s version was a marked popular success. Over the next few years, the publishing house issued further editions in quick succession, adding still more non-Raspe material along the way; even the full-length Sequel to the Adventures of Baron Munchausen, again not by Raspe and originally published in 1792 by a rival printer, was quickly subsumed into the body of stories. In the process of revision, Raspe’s prose style was heavily modified; instead of his conversational language and sportsmanlike turns of phrase, Kearsley’s writers opted for a blander and more formal tone imitating Augustan prose.[28] Most ensuing English-language editions, including even the major editions produced by Thomas Seccombe in 1895 and F. J. Harvey Darton in 1930, reproduce one of the rewritten Kearsley versions rather than Raspe’s original text.[29]

At least ten editions or translations of the book appeared before Raspe’s death in 1794.[30] Translations of the book into French, Spanish, and German were published in 1786.[22] The text reached the United States in 1805, expanded to include American topical satire by an anonymous Federalist writer, probably Thomas Green Fessenden.[31]

Gottfried August Bürger translated the book into German, and was often assumed to be its author.

The first German translation, Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, was made by the German Romantic poet Gottfried August Bürger. Bürger’s text is a close translation of Smith’s second edition, but also includes an interpolated story, based on a German legend called «The Six Wonderful Servants». Two new engravings were added to illustrate the interpolated material.[32] The German version of the stories proved to be even more popular than the English one.[33] A second German edition in 1788 included heavily altered material from an expanded Kearsley edition, and an original German sequel, Nachtrag zu den wunderbaren Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, was published in 1789. After these publications, the English and Continental versions of the Raspe text continued to diverge, following increasingly different traditions of included material.[34]

Raspe, probably for fear of a libel suit from the real-life Baron von Münchhausen, never admitted his authorship of the book.[35] It was often credited to Bürger,[19] sometimes with an accompanying rumor that the real-life Baron von Münchhausen had met Bürger in Pyrmont and dictated the entire work to him.[36] Another rumor, which circulated widely soon after the German translation was published, claimed that it was a competitive collaboration by three University of Göttingen scholars—Bürger, Abraham Gotthelf Kästner, and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg—with each of the three trying to outdo one another by writing the most unbelievable tale.[37] The scholar Johann Georg Meusel correctly credited Raspe for the core text, but mistakenly asserted that Raspe had written it in German and that an anonymous translator was responsible for the English version.[36] Raspe’s authorship was finally proven in 1824 by Bürger’s biographer, Karl Reinhard.[38][c]

In the first few years after publication, German readers widely assumed that the real-life Baron von Münchhausen was responsible for the stories.[22] According to witnesses, Münchhausen was deeply angry that the book had dragged his name into public consciousness and insulted his honor as a nobleman. Münchhausen became a recluse, refusing to host parties or tell any more stories,[22] and he attempted without success to bring legal proceedings against Bürger and the publisher of the translation.[40]

Publication history[edit]

The following tables summarize the early publication history of Raspe’s text, from 1785 to 1800. Unless otherwise referenced, information in the tables comes from the Munchausen bibliography established by John Patrick Carswell.[41]

| Raspe’s English text | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Edition | Title on title page | Publication | Contents |

| First | Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. Humbly dedicated and recommended to Country Gentlemen; and, if they please, to be repeated as their own, after a Hunt, at Horse Races, in Watering Places, and other such polite Assemblies, round the bottle and fireside | Oxford: Smith, 1786 [actually late 1785][d] | Adaptations by Raspe of fifteen of the sixteen anecdotes from «M-h-s-nsche Geschichten» and both of the anecdotes from «Noch zwei M-Lügen». |

| Second | Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Sporting Adventures of Baron Munnikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen; as he relates them over a Bottle when surrounded by his Friends. A New Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with four Views, engraved from the Baron’s own drawings | Oxford: Smith, [April] 1786 | Same as the First Edition, plus five new stories probably by Raspe and four illustrations possibly also by Raspe. |

| Third | Gulliver Revived, or the singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures of Baron Munikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen. The Third Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Views, engraved from the original designs | Oxford: G. Kearsley, [May] 1786 | Same stories and engravings as the Second Edition, plus new non-Raspe material and twelve new engravings. Many alterations are made to Raspe’s original text. |

| Fourth | Gulliver Revived containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, and on the Atlantic Ocean: Also an Account of a Voyage into the Moon, with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in that Planet, which are here called the Human Species, by Baron Munchausen. The Fourth Edition. Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Sixteen explanatory Views, engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, [July] 1786 | Same stories as the Third Edition, plus new material not by Raspe, including the cannonball ride, the journey with Captain Hamilton, and the Baron’s second trip to the Moon. Further alterations to Raspe’s text. Eighteen engravings, though only sixteen are mentioned on the title page. |

| Fifth | Gulliver Revived, containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Etna into the South Sea: Also an Account of a Voyage to the Moon and Dog Star, with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are here called the Human Species, by Baron Munchausen. The Fifth Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with a variety of explanatory Views, engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, 1787 | Same contents as the Fourth Edition, plus the trips to Ceylon (added at the beginning) and Mount Etna (at the end), and a new frontispiece. |

| Sixth | Gulliver Revived or the Vice of Lying properly exposed; containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Etna into the South Sea: also an Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species by Baron Munchausen. The Sixth Edition. Considerably enlarged and ornamented with a variety of explanatory Views engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, 1789[e] | Same contents as the Fifth Edition, plus a «Supplement» about a ride on an eagle and a new frontispiece. |

| Seventh | The Seventh Edition, Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Twenty Explanatory Engravings, from Original Designs. Gulliver Revived: or, the Vice of Lying properly exposed. Containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Aetna, into the South Sea. Also, An Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star; with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species. By Baron Munchausen | London: C. and G. Kearsley, 1793 | Same as the Sixth Edition. |

| Eighth | The Eighth Edition, Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Twenty Explanatory Engravings, from Original Designs. Gulliver Revived: or, the Vice of Lying properly exposed. Containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Aetna, into the South Sea. Also, An Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star; with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species. By Baron Munchausen | London: C. and G. Kearsley, 1799 | Same as the Sixth Edition. |

| Early Munchausen translations and sequels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Title | Publication | Contents |

| German | Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, feldzüge und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen wie er dieselben bey der Flasche im Zirkel seiner Freunde zu Erzählen pflegt. Aus dem Englischen nach der neuesten Ausgabe übersetzt, hier und da erweitert und mit noch mehr Küpfern gezieret | London [actually Göttingen]: [Johann Christian Dieterich,] 1786 | Gottfried August Bürger’s free translation of the English Second Edition, plus new material added by Bürger. Four illustrations from the English Second Edition and three new ones. |

| French | Gulliver ressuscité, ou les voyages, campagnes et aventures extraordinaires du Baron de Munikhouson | Paris: Royez, 1787 | Slightly modified translation of the English Fifth Edition. |

| German | Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, feldzüge und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen, wie er dieselben bey der Flasche im Zirkel seiner Freunde zu Erzählen pflegt. Aus dem Englischen nach der neuesten Ausgabe übersetzt, hier und da erweitert und mit noch mehr Küpfern gezieret. Zweite vermehrte Ausgabe | London [actually Göttingen]: [Johann Christian Dieterich,] 1788 | Same as previous German edition, plus a translation of the new material from the English Fifth Edition, greatly revised. |

| German | Nachtrag zu den wunderbaren Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen, wie er dieselben bey der Flasch Wein im Zirkel seiner Freunde selbst zu erzählen pflegt. Mit Küpferrn | Copenhagen, 1789 | Original German sequel, sharply satirizing the Baron. Includes twenty-three engravings and an «Elegy on the Death of Herr von Münchhausen» (though the real-life Baron had not yet died). |

| English | A Sequel to the Adventures of Baron Munchausen humbly dedicated to Mr Bruce the Abyssinian Traveller, As the Baron conceives that it may be of some service to him making another expedition into Abyssinia; but if this does not delight Mr Bruce, the Baron is willing to fight him on any terms he pleases | [London:] H. D. Symonds, 1792 [a second edition was published 1796] | Original English sequel, satirizing the travels of James Bruce. Includes twenty engravings. This Sequel was often printed alongside the Raspe text as «Volume Two of the Baron’s Travels». |

Fictional character[edit]

The fictional Baron Munchausen is a braggart soldier, most strongly defined by his comically exaggerated boasts about his own adventures.[44] All of the stories in Raspe’s book are told in first-person narrative, with a prefatory note explaining that «the Baron is supposed to relate these extraordinary Adventures over his Bottle, when surrounded by his Friends».[45] The Baron’s stories imply him to be a superhuman figure who spends most of his time either getting out of absurd predicaments or indulging in equally absurd moments of gentle mischief.[46] In some of his best-known stories, the Baron rides a cannonball, travels to the Moon, is swallowed by a giant fish in the Mediterranean Sea, saves himself from drowning by pulling up on his own hair, fights a forty-foot crocodile, enlists a wolf to pull his sleigh, and uses laurel tree branches to fix his horse when the animal is accidentally cut in two.[19]

In the stories he narrates, the Baron is shown as a calm, rational man, describing what he experiences with simple objectivity; absurd happenings elicit, at most, mild surprise from him, and he shows serious doubt about any unlikely events he has not witnessed himself.[47] The resulting narrative effect is an ironic tone, encouraging skepticism in the reader[48] and marked by a running undercurrent of subtle social satire.[46] In addition to his fearlessness when hunting and fighting, he is suggested to be a debonair, polite gentleman given to moments of gallantry, with a scholarly penchant for knowledge, a tendency to be pedantically accurate about details in his stories, and a deep appreciation for food and drink of all kinds.[49] The Baron also provides a solid geographical and social context for his narratives, peppering them with topical allusions and satire about recent events; indeed, many of the references in Raspe’s original text are to historical incidents in the real-life Münchhausen’s military career.[50]

Because the feats the Baron describes are overtly implausible, they are easily recognizable as fiction,[51] with a strong implication that the Baron is a liar.[44] Whether he expects his audience to believe him varies from version to version; in Raspe’s original 1785 text, he simply narrates his stories without further comment, but in the later extended versions he is insistent that he is telling the truth.[52] In any case, the Baron appears to believe every word of his own stories, no matter how internally inconsistent they become, and he usually appears tolerantly indifferent to any disbelief he encounters in others.[53]

Illustrations for the stories

-

The Baron returns from the Moon: illustration, possibly by Raspe, for the second edition of the book

-

The anonymous 1792 portrait of the Baron

-

The Baron rides a half-horse, illustrated by George Cruikshank

-

The Baron picks up a carriage, illustrated by Theodor Hosemann

-

The Baron retrieved from the whale, illustrated by Gustave Doré

Illustrators of the Baron stories have included Thomas Rowlandson, Alfred Crowquill, George Cruikshank, Ernst Ludwig Riepenhausen, Theodor Hosemann, Adolf Schrödter, Gustave Doré, William Strang,[54] W. Heath Robinson,[55] and Ronald Searle.[56] The Finnish-American cartoonist Klaus Nordling featured the Baron in a weekly Baron Munchausen comic strip from 1935 to 1937,[57] and in 1962, Raspe’s text was adapted for Classics Illustrated #146 (British series), with both interior and cover art by the British cartoonist Denis Gifford.[58]

In the first published illustrations, which may have been drawn by Raspe himself, the Baron appears slim and youthful.[59] For the 1792 Sequel to the Adventures of Baron Munchausen, an anonymous artist drew the Baron as a dignified but tired old soldier whose face is marred by injuries from his adventures; this illustration remained the standard portrait of the Baron for about seventy years, and its imagery was echoed in Cruikshank’s depictions of the character. Doré, illustrating a Théophile Gautier fils translation in 1862, retained the sharply beaked nose and twirled moustache from the 1792 portrait, but gave the Baron a healthier and more affable appearance; the Doré Baron became the definitive visual representation for the character.[60]

The relationship between the real and fictional Barons is complex. On the one hand, the fictional Baron Munchausen can be easily distinguished from the historical figure Hieronymus von Münchhausen;[4] the character is so separate from his namesake that at least one critic, the writer W. L. George, concluded that the namesake’s identity was irrelevant to the general reader,[61] and Richard Asher named Munchausen syndrome using the anglicized spelling so that the disorder would reference the character rather than the real person.[4] On the other hand, Münchhausen remains strongly connected to the character he inspired, and is still nicknamed the Lügenbaron («Baron of Lies») in German.[22] As the Munchausen researcher Bernhard Wiebel has said, «These two barons are the same and they are not the same.»[62]

Critical and popular reception[edit]

Statue of Munchausen in Bodenwerder

Reviewing the first edition of Raspe’s book in December 1785, a writer in The Critical Review commented appreciatively:[63]

This is a satirical production calculated to throw ridicule on the bold assertions of some parliamentary declaimers. If rant may be best foiled at its own weapons, the author’s design is not ill-founded; for the marvellous has never been carried to a more whimsical and ludicrous extent.[63][f]

At around the same time, English Review was less approving: «We do not understand how a collection of lies can be called a satire on lying, any more than the adventures of a woman of pleasure can be called a satire on fornication.»[64]

W. L. George described the fictional Baron as a «comic giant» of literature, describing his boasts as «splendid, purposeless lie[s] born of the joy of life».[65] Théophile Gautier fils highlighted that the Baron’s adventures are endowed with an «absurd logic pushed to the extreme and which backs away from nothing».[66] According to an interview, Jules Verne relished reading the Baron stories as a child, and used them as inspiration for his own adventure novels.[67] Thomas Seccombe commented that «Munchausen has undoubtedly achieved [a permanent place in literature] … The Baron’s notoriety is universal, his character proverbial, and his name as familiar as that of Mr. Lemuel Gulliver, or Robinson Crusoe.»[68]

Steven T. Byington wrote that «Munchausen’s modest seat in the Valhalla of classic literature is undisputed», comparing the stories to American tall tales and concluding that the Baron is «the patriarch, the perfect model, the fadeless fragrant flower, of liberty from accuracy».[69] The folklore writer Alvin Schwartz cited the Baron stories as one of the most important influences on the American tall tale tradition.[70] In a 2012 study of the Baron, the literary scholar Sarah Tindal Kareem noted that «Munchausen embodies, in his deadpan presentation of absurdities, the novelty of fictionality [and] the sophistication of aesthetic illusion», adding that the additions to Raspe’s text made by Kearsley and others tend to mask these ironic literary qualities by emphasizing that the Baron is lying.[52]

By the beginning of the 19th century, Kearsley’s phenomenally popular version of Raspe’s book had spread to abridged chapbook editions for young readers, who soon became the main audience for the stories.[71] The book, especially in its adaptations for children, remained widely popular throughout the century.[72] It was translated into nearly all languages spoken in Europe;[73] Robert Southey referred to it as «a book which everybody knows, because all boys read it».[71] Notable later translations include Gautier’s French rendering[59] and Korney Chukovsky’s popular Russian adaptation.[74] By the 1850s, Munchausen had come into slang use as a verb meaning «to tell extravagantly untruthful pseudo-autobiographical stories».[75] Robert Chambers, in an 1863 almanac, cited the iconic 1792 illustration of the Baron by asking rhetorically:

Who is there that has not, in his youth, enjoyed The Surprising Travels and Adventures of Baron Munchausen in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, &c. a slim volume—all too short, indeed—illustrated by a formidable portrait of the baron in front, with his broad-sword laid over his shoulder, and several deep gashes on his manly countenance? I presume they must be few.[72]

Though Raspe’s book is no longer widely read by English-speakers,[76] the Munchausen stories remain popular in Europe, especially in Germany and in Russia.[77]

In culture[edit]

Literature[edit]

As well as the many augmented and adapted editions of Raspe’s text, the fictional Baron has occasionally appeared in other standalone works.[78] In 1838–39, Karl Leberecht Immermann published the long novel Münchhausen: Eine Geschichte in Arabesken (Münchhausen: A History of Arabesques)[79] as an homage to the character, and Adolf Ellissen’s Munchausens Lügenabenteur, an elaborate expansion of the stories, appeared in 1846.[73] In his 1886 philosophical treatise Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche uses one of the Baron’s adventures, the one in which he rescues himself from a swamp, as a metaphor for belief in complete metaphysical free will; Nietzsche calls this belief an attempt «to pull oneself up into existence by the hair, out of the swamps of nothingness».[80] Another philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, references the same adventure in a diary entry from 11.4.1937; his note records his having dreamt saying «But let us talk in our mother tongue, and not believe that we must pull ourselves out of the swamp by our own hair; that was – thank God – only a dream, after all. To God alone be praise!»[81]

In the late 19th century, the Baron appeared as a character in John Kendrick Bangs’s comic novels A House-Boat on the Styx, Pursuit of the House-Boat, and The Enchanted Type-Writer.[82] Shortly after, in 1901, Bangs published Mr. Munchausen, a collection of new Munchausen stories, closely following the style and humor of the original tales.[78] Hugo Gernsback’s second novel, Baron Münchhausen’s New Scientific Adventures, put the Baron character in a science fiction setting; the novel was serialized in The Electrical Experimenter from May 1915 to February 1917.[83]

Pierre Henri Cami’s character Baron de Crac, a French soldier and courtier under Louis XV,[84] is an imitation of the Baron Munchausen stories.[85] In 1998,[86] the British game designer James Wallis used the Baron character to create a multi-player storytelling game, The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen, in which players improvise Munchausen-like first-person stories while overcoming objections and other interruptions from opponents.[87] The American writer Peter David had the Baron narrate an original short story, «Diego and the Baron», in 2018.[88]

Stage and audio[edit]

For radio, Jack Pearl (right) and Cliff Hall (left) played the Baron and his disbelieving foil Charlie, respectively.

Sadler’s Wells Theatre produced the pantomime Baron Munchausen; or, Harlequin’s Travels in London in 1795, starring the actor-singer-caricaturist Robert Dighton as the Baron;[89] another pantomime based on the Raspe text, Harlequin Munchausen, or the Fountain of Love, was produced in London in 1818.[75] Herbert Eulenberg made the Baron the main character of a 1900 play, Münchhausen,[90] and the Expressionist writer Walter Hasenclever turned the stories into a comedy, Münchhausen,[79] in 1934.[91] Grigori Gorin used the Baron as the hero of his 1976 play That Very Munchausen;[92] a film version was made in 1980.[93] Baron Prášil, a Czech musical about the Baron, opened in 2010 in Prague.[94][g] The following year, the National Black Light Theatre of Prague toured the United Kingdom with a nonmusical production of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen.[95]

In 1932, the comedy writer Billy Wells adapted Baron Munchausen for a radio comedy routine starring the comedians Jack Pearl and Cliff Hall.[96] In the routine, Pearl’s Baron would relate his unbelievable experiences in a thick German accent to Hall’s «straight man» character, Charlie. When Charlie had had enough and expressed disbelief, the Baron would invariably retort: «Vass you dere, Sharlie?»[97] The line became a popular and much-quoted catchphrase, and by early 1933 The Jack Pearl Show was the second most popular series on American radio (after Eddie Cantor’s program).[97] Pearl attempted to adapt his portrayal to film in Meet the Baron in 1933, playing a modern character mistaken for the Baron,[97] but the film was not a success.[96] Pearl’s popularity gradually declined between 1933 and 1937, though he attempted to revive the Baron character several times before ending his last radio series in 1951.[98]

For a 1972 Caedmon Records recording of some of the stories,[99][100] Peter Ustinov voiced the Baron. A review in The Reading Teacher noted that Ustinov’s portrayal highlighted «the braggadocio personality of the Baron», with «self-adulation … plainly discernible in the intonational innuendo».[101]

Film[edit]

The Baron travels underwater, illustrated by Gottfried Franz.

The early French filmmaker Georges Méliès, who greatly admired the Baron Munchausen stories,[66] filmed Baron Munchausen’s Dream in 1911. Méliès’s short silent film, which has little in common with the Raspe text, follows a sleeping Baron through a surrealistic succession of intoxication-induced dreams.[102] Méliès may also have used the Baron’s journey to the moon as an inspiration for his well-known 1902 film A Trip to the Moon.[66] In the late 1930s, he planned to collaborate with the Dada artist Hans Richter on a new film version of the Baron stories, but the project was left unfinished at his death in 1938.[103] Richter attempted to complete it the following year, taking on Jacques Prévert, Jacques Brunius, and Maurice Henry as screenwriters, but the beginning of the Second World War put a permanent halt to the production.[104]

The French animator Émile Cohl produced a version of the stories using silhouette cutout animation in 1913; other animated versions were produced by Richard Felgenauer in Germany in 1920, and by Paul Peroff in the United States in 1929.[104] Colonel Heeza Liar, the protagonist of the first animated cartoon series in cinema history, was created by John Randolph Bray in 1913 as an amalgamation of the Baron and Teddy Roosevelt.[105] The Italian director Paolo Azzurri filmed The Adventures of Baron Munchausen in 1914,[106] and the British director F. Martin Thornton made a short silent film featuring the Baron, The New Adventures of Baron Munchausen, the following year.[107] In 1940, the Czech director Martin Frič filmed Baron Prášil, starring the comic actor Vlasta Burian as a 20th-century descendant of the Baron.[108][g]

For the German film studio U.F.A. GmbH’s 25th anniversary in 1943, Joseph Goebbels hired the filmmaker Josef von Báky to direct Münchhausen, a big-budget color film about the Baron.[109] David Stewart Hull describes Hans Albers’s Baron as «jovial but somewhat sinister»,[110] while Tobias Nagle writes that Albers imparts «a male and muscular zest for action and testosterone-driven adventure».[111] A German musical comedy, Münchhausen in Afrika, made as a vehicle for the Austrian singing star Peter Alexander, appeared in 1957.[112] Karel Zeman’s 1961 Czech film The Fabulous Baron Munchausen commented on the Baron’s adventures from a contemporary perspective, highlighting the importance of the poetic imagination to scientific achievement; Zeman’s stylized mise-en-scène, based on Doré’s illustrations for the book, combined animation with live-action actors, including Miloš Kopecký as the Baron.[113]

In the Soviet Union, in 1929, Daniil Cherkes released a cartoon, Adventures of Munchausen.[114][115][116] Soviet Soyuzmultfilm released a 16-minute stop-motion animation Adventures of Baron Munchausen in 1967, directed by Anatoly Karanovich.[117] Another Soviet animated version was produced as a series of short films, Munchausen’s Adventures, in 1973 and 1974.[118] The French animator Jean Image filmed The Fabulous Adventures of the Legendary Baron Munchausen in 1979,[106] and followed it with a 1984 sequel, Moon Madness.[119]

Oleg Yankovsky appeared as the Baron in the 1979 Russian television film The Very Same Munchhausen, directed by Mark Zakharov from Grigori Gorin’s screenplay, produced and released by Mosfilm. The film, a satirical commentary on Soviet censorship and social mores, imagines an ostracized Baron attempting to prove the truth of his adventures in a disbelieving and conformity-driven world.[93]

In 1988, Terry Gilliam adapted the Raspe stories into a lavish Hollywood film, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, with the British stage actor and director John Neville in the lead role. Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, described Neville’s Baron as a man who «seems sensible and matter-of-fact, as anyone would if they had spent a lifetime growing accustomed to the incredible».[120]

The German actor Jan Josef Liefers starred in a 2012 two-part television film titled Baron on the Cannonball [de]; according to a Spiegel Online review, his characterization of the Baron strongly resembled Johnny Depp’s performance as Jack Sparrow in the Pirates of the Caribbean film series.[121]

Legacy[edit]

Memorials[edit]

Latvian commemorative coin of 2005

In 2004, a fan club calling itself Munchausen’s Grandchildren was founded in the Russian city of Kaliningrad (formerly Königsberg). The club’s early activities included identifying «historical proofs» of the fictional Baron’s travels through Königsberg, such as a jackboot supposedly belonging to the Baron[122] and a sperm whale skeleton said to be that of the whale in whose belly the Baron was trapped.[123]

On 18 June 2005, to celebrate the 750th anniversary of Kaliningrad, a monument to the Baron was unveiled as a gift from Bodenwerder, portraying the Baron’s cannonball ride.[124] Bodenwerder sports a Munchausen monument in front of its Town Hall,[77] as well as a Munchausen museum including a large collection of illustrated editions of the stories.[125] Another Munchausen Museum (Minhauzena Muzejs) exists in Duntes Muiža, Liepupe parish, Latvia,[126] home of the real Baron’s first wife;[127] the couple had lived in the town for six years, before moving back to the baronial estate in Hanover.[77] In 2005, to mark the real-life Baron’s 285th birthday, the National Bank of Latvia issued a commemorative silver coin.[77]

Nomenclature[edit]

In 1951, the British physician Richard Asher published an article in The Lancet describing patients whose factitious disorders led them to lie about their own states of health. Asher proposed to call the disorder «Munchausen’s syndrome», commenting: «Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always travelled widely; and their stories, like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful. Accordingly, the syndrome is respectfully dedicated to the baron, and named after him».[19] The disease is now usually referred to as Munchausen syndrome.[128] The name has spawned two other coinages: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, in which illness is feigned by caretakers rather than patients,[19] and Munchausen by Internet, in which illness is feigned online.[129]

In 1968, Hans Albert coined the term Münchhausen trilemma to describe the philosophical problem inherent in having to derive conclusions from premises; those premises have to be derived from still other premises, and so on forever, leading to an infinite regress interruptible only by circular logic or dogmatism. The problem is named after the similarly paradoxical story in which the Baron saves himself from being drowned in a swamp by pulling on his own hair.[130] The same story also inspired the mathematical term Munchausen number, coined by Daan van Berkel in 2009 to describe numbers whose digits, when raised to their own powers, can be added together to form the number itself (for example, 3435 = 33 + 44 + 33 + 55).[131]

Subclass ATU1889 of the Aarne–Thompson–Uther classification system, a standard index of folklore, was named «Münchhausen Tales» in tribute to the stories.

[132] In 1994, a main belt asteroid was named 14014 Münchhausen in honor of both the real and the fictional Baron.[133]

Notes and references[edit]

Explanatory footnotes[edit]

- ^ The German name for both the fictional character and his historical namesake is Münchhausen. The simplified spelling Munchausen, with one h and no umlaut, is standard in English when discussing the fictional character, as well as the medical conditions named for him.[3][4]

- ^ Both booksellers worked in Oxford and used the same London address, 46 Fleet Street, so it is possible that Kearsley had also been involved in some capacity with publication of the first and second editions.[26]

- ^ Nonetheless, no known edition of the book credited Raspe on its title page until John Patrick Carswell’s 1948 Cresset Press edition.[39]

- ^ An Irish edition issued soon after (Dublin: P. Byrne, 1786) has the same text but is reset and introduces a few new typographical errors.[42]

- ^ A pirated reprint, with all the engravings except the new frontispiece, appeared the next year (Hamburgh: B. G. Hoffmann, 1790).[43]

- ^ At the time, «ludicrous» was not a negative term; rather, it suggested that humor in the book was sharply satirical.[40]

- ^ a b Among Czech speakers, the fictional Baron is usually called Baron Prášil.[104]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Cambridge University Press 2015.

- ^ «Munchausen, Baron», Lexico UK English Dictionary, Oxford University Press[dead link]

- ^ Olry 2002, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Fisher 2006, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e f g Krause 1886, p. 1.

- ^ a b Carswell 1952b, p. xxvii.

- ^ a b Carswell 1952b, p. xxv.

- ^ Levi 1998, p. 177.

- ^ Olry 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Fisher 2006, p. 251.

- ^ Carswell 1952b, pp. xxvii–xxviii.

- ^ Kareem 2012, pp. 495–496.

- ^ a b c d Meadow & Lennert 1984, p. 555.

- ^ a b Seccombe 1895, p. xxii.

- ^ Carswell 1952b, p. x.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ^ a b c Blamires 2009, §3.

- ^ Krause 1886, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Olry 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §8.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. xix.

- ^ a b c d e Fisher 2006, p. 252.

- ^ Carswell 1952b, pp. xxvi–xxvii.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Carswell 1952a, p. 167.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Carswell 1952b, pp. xxxi–xxxii.

- ^ Carswell 1952b, p. xxxvii.

- ^ Olry 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Gudde 1942, p. 372.

- ^ Carswell 1952b, p. xxx.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §5.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, p. 171.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §6–7.

- ^ a b Seccombe 1895, p. xi.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. x.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. xii.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §4.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 491.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, pp. 164–175.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Carswell 1952a, p. 173.

- ^ a b George 1918, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 488.

- ^ a b Fisher 2006, p. 253.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 484.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §12–13.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 492.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 485.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, pp. xxxv–xxxvi.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §29.

- ^ Raspe 1969.

- ^ Holtz 2011.

- ^ Jones 2011, p. 352.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 500.

- ^ Kareem 2012, pp. 500–503.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Wiebel 2011.

- ^ a b Seccombe 1895, p. vi.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 496.

- ^ George 1918, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Lefebvre 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Compère, Margot & Malbrancq 1998, p. 232.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. v.

- ^ Byington 1928, pp. v–vi.

- ^ Schwartz 1990, p. 105.

- ^ a b Blamires 2009, §24.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 503.

- ^ a b Carswell 1952b, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Balina, Goscilo & Lipovet︠s︡kiĭ 2005, p. 247.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 504.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 486.

- ^ a b c d Baister & Patrick 2007, p. 159.

- ^ a b Blamires 2009, §30.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski 2007, p. 78.

- ^ Nietzsche 2000, p. 218.

- ^ Wittgenstein 2003.

- ^ Bangs 1895, p. 27; Bangs 1897, p. 27; Bangs 1899, p. 34.

- ^ Westfahl 2007, p. 209.

- ^ Cami 1926.

- ^ George 1918, p. 175.

- ^ Wardrip-Fruin 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Mitchell & McGee 2009, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Bold Venture Press 2018.

- ^ Sadler’s Wells 1795, p. 2.

- ^ Eulenberg 1900.

- ^ Furness & Humble 1991, p. 114.

- ^ Balina, Goscilo & Lipovet︠s︡kiĭ 2005, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b Hutchings 2004, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Košatka 2010.

- ^ Czech Centre London 2011.

- ^ a b Erickson 2014, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Erickson 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Erickson 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Baron Munchausen: Eighteen Truly Tall Tales by Raspe and Others. Retold by Doris Orgel, Read by Peter Ustinov.

Caedmon Records (TC 1409), 1972. Format: LP Record - ^ Baron Munchausen: Eighteen Truly Tall Tales by Raspe and Others. Read by Peter Ustinov, Retold by Doris Orgel. Collins-Caedmon (SirH70), 1972. Format: Audio Cassette.

- ^ Knight 1973, p. 119.

- ^ Zipes 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Ezra 2000, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Sadoul & Morris 1972, p. 25.

- ^ Shull & Wilt 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b Zipes 2010, p. 408.

- ^ Young 1997, p. 441.

- ^ Česká televize.

- ^ Hull 1969, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Hull 1969, p. 254.

- ^ Nagle 2010, p. 269.

- ^ Arndt & von Brisinski 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Hames 2009, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Cartoon on Animator.ru

- ^ Cartoon on youtube

- ^ Cartoon on youtube with english subs

- ^ Venger & Reisner, «Adventures of Baron Munghausen» [sic].

- ^ Venger & Reisner, «Munchausen’s Adventures».

- ^ Willis 1984, p. 184.

- ^ Ebert 1989.

- ^ Hass 2012.

- ^ Викторова 2004.

- ^ Волошина & Захаров 2006.

- ^ Kaliningrad-Aktuell 2005.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §32.

- ^ Munchausen’s Museum – Minhauzena Pasaule

- ^ Baister & Patrick 2007, p. 154.

- ^ Fisher 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Feldman 2000.

- ^ Apel 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Olry & Haines 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Ziolkowski 2007, p. 77.

- ^ NASA 2013.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Apel, Karl-Otto (2001), The Response of Discourse Ethics to the Moral Challenge of the Human Situation as Such and Especially Today, Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, ISBN 978-90-429-0978-6

- Arndt, Susan; von Brisinski, Marek Spitczok (2006), Africa, Europe and (Post)Colonialism: Racism, Migration and Diaspora in African Literatures, Bayreuth. Germany: Breitinger

- Baister, Stephen; Patrick, Chris (2007), Latvia: The Bradt Travel Guide, Chalfont St. Peter, Buckinghamshire: Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 978-1-84162-201-9

- Balina, Marina; Goscilo, Helena; Lipovet︠s︡kiĭ, M. N. (2005), Politicizing Magic: An Anthology of Russian and Soviet Fairy Tales, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, ISBN 978-0-8101-2032-7

- Bangs, John Kendrick (1895), House-Boat on the Styx: Being Some Account of the Divers Doings of the Associated Shades, New York: Harper & Bros., ISBN 9781404708037

- Bangs, John Kendrick (1897), The Pursuit of the House-Boat: Being Some Further Account of the Divers Doings of the Associated Shades, Under the Leadership of Sherlock Holmes, Esq., New York: Harper & Bros.

- Bangs, John Kendrick (1899), The Enchanted Typewriter, New York: Harper & Bros., ISBN 9780598867315

- Blamires, David (2009), «The Adventures of Baron Munchausen», Telling Tales: The Impact of Germany on English Children’s Books 1780–1918, OBP collection, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: Open Book Publishers, pp. 8–21, ISBN 9781906924119

- Bold Venture Press (2018), «Zorro and the Little Devil», Bold Venture Press, archived from the original on 16 July 2018, retrieved 17 September 2018

- Byington, Steven T. (1928), «Preface», Baron Munchausen’s Narratives of His Marvelous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, Boston: Ginn and Co., pp. v–viii

- Cambridge University Press (2015), «English pronunciation of ‘Munchausen’s syndrome’«, Cambridge Dictionaries Online, retrieved 4 April 2015

- Cami, Pierre-Henri (1926), Les Aventures sans pareilles du baron de Crac (in French), Paris: Hachette

- Carswell, John Patrick (1952a), «Bibliography», in Raspe, Rudolf Erich (ed.), The Singular Adventures of Baron Munchausen, New York: Heritage Press, pp. 164–175

- Carswell, John Patrick (1952b), «Introduction», in Raspe, Rudolf Erich (ed.), The Singular Adventures of Baron Munchausen, New York: Heritage Press, pp. ix–xxxviii

- Česká televize, «Když Burian prášil», Ceskatelevize.cz (in Czech), retrieved 22 March 2015

- Compère, Daniel; Margot, Jean-Michel; Malbrancq, Sylvie (1998), Entretiens avec Jules Verne (in French), Geneva: Slatkine

- Czech Centre London (2011), «The National Black Light Theatre of Prague: The Adventures of Baron Munchausen», Czechcentres.cz, retrieved 23 March 2015

- Ebert, Roger (10 March 1989), «The Adventures of Baron Munchausen», RogerEbert.com, retrieved 3 January 2015

- Erickson, Hal (2014), From Radio to the Big Screen: Hollywood Films Featuring Broadcast Personalities and Programs, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-7757-9

- Eulenberg, Herbert (1900), Münchhausen: Ein Deutsches Schauspiel (in German), Berlin: Sassenbach

- Ezra, Elizabeth (2000), Georges Méliès, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-5395-1

- Feldman, M. D. (July 2000), «Munchausen by Internet: detecting factitious illness and crisis on the Internet», Southern Medical Journal, 93 (7): 669–672, doi:10.1097/00007611-200093070-00006, PMID 10923952

- Fisher, Jill A. (Spring 2006), «Investigating the Barons: narrative and nomenclature in Munchausen syndrome», Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 49 (2): 250–262, doi:10.1353/pbm.2006.0024, PMID 16702708, S2CID 12418075

- Furness, Raymond; Humble, Malcolm (1991), A Companion to Twentieth-Century German Literature, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-15057-6

- George, W. L. (1918), «Three Comic Giants: Munchausen», Literary Chapters, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, pp. 168–182

- Gudde, Edwin G. (January 1942), «An American Version of Munchausen», American Literature, 13 (4): 372–390, doi:10.2307/2920590, JSTOR 2920590

- Hames, Peter (2009), Czech and Slovak Cinema: Theme and Tradition, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- Hass, Daniel (24 December 2012), «ARD-Zweiteiler «Baron Münchhausen»: Müssen Sie sehen! Großartiger Film!», Spiegel Online (in German), retrieved 24 March 2015

- Holtz, Allan (6 May 2011), «Obscurity of the Day: Baron Munchausen», Stripper’s Guide, retrieved 24 March 2015

- Hull, David Stewart (1969), Film in the Third Reich: A Study of the German Cinema, 1933–1945, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

- Hutchings, Stephen C. (2004), Russian Literary Culture in the Camera Age: The Word As Image, London: RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 978-1-134-40051-5

- Jones, William B. (2011), Classics Illustrated: A Cultural History, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-8840-7

- Kaliningrad-Aktuell (22 June 2005), «Münchhausen-Denkmal in Kaliningrad eingeweiht», Russland-Aktuell (in German), retrieved 24 March 2015

- Kareem, Sarah Tindal (May 2012), «Fictions, Lies, and Baron Munchausen’s Narrative«, Modern Philology, 109 (4): 483–509, doi:10.1086/665538, JSTOR 10.1086/665538, S2CID 162337428

- Knight, Lester N. (October 1973), «The Story of Peter Pan; Baron Munchausen: Eighteen Truly Tall Tales by Raspe and Others by Raspe», The Reading Teacher, 27 (1): 117, 119, JSTOR 20193416

- Košatka, Pavel (1 March 2010), «Komplexní recenze nového muzikálového hitu «Baron Prášil»«, Muzical.cz (in Czech), retrieved 4 January 2015

- Krause, Karl Ernst Hermann (1886), «Münchhausen, Hieronimus Karl Friedrich Freiherr von», Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), vol. 23, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 1–5

- Lefebvre, Thierry (2011), «A Trip to the Moon: A Composite Film», in Solomon, Matthew (ed.), Fantastic Voyages of the Cinematic Imagination: Georges Méliès’s Trip to the Moon, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, pp. 49–64, ISBN 978-1-4384-3581-7

- Levi, Claudia (1998), «Georgia Augustus University of Göttingen», in Summerfield, Carol J.; Devine, Mary Elizabeth (eds.), International Dictionary of University Histories, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, pp. 177–180, ISBN 978-1-134-26217-5

- Meadow, Roy; Lennert, Thomas (October 1984), «Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy or Polle Syndrome: Which Term is Correct?», Pediatrics, 74 (4): 554–556, doi:10.1542/peds.74.4.554, PMID 6384913

- Mitchell, Alex; McGee, Kevin (2009), «Designing Storytelling Games That Encourage Narrative Play», in Iurgel, Ido; Zagalo, Nelson; Petta, Paolo (eds.), Interactive Storytelling: Second Joint International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2009, Guimarães, Portugal, December 9-11, 2009: Proceedings, Berlin: Springer, pp. 98–108, ISBN 978-3-642-10642-2

- Nagle, Tobias (2010), «Projecting Desire, Rewriting Cinematic Memory: Gender and German Reconstruction in Michael Haneke’s Fraulein«, in Grundmann, Roy (ed.), A Companion to Michael Haneke, Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 263–278, ISBN 978-1-4443-2061-9

- NASA (2013), «14014 Munchhausen (1994 AL16)», JPL Small-Body Database Browser, retrieved 3 February 2015

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (2000), Basic Writings of Nietzsche, trans. and ed. Walter Kaufmann, New York: Modern Library, ISBN 978-0-307-41769-5

- Olry, R. (June 2002), «Baron Munchhausen and the Syndrome Which Bears His Name: History of an Endearing Personage and of a Strange Mental Disorder» (PDF), Vesalius, VIII (1): 53–57, retrieved 2 January 2015

- Olry, Régis; Haines, Duane E. (2013), «Historical and Literary Roots of Münchhausen Syndromes: As Intriguing as the Syndromes Themselves», in Finger, Stanley; Boller, François; Stiles, Anne (eds.), Literature, Neurology, and Neuroscience, Burlington: Elsevier Science, pp. 123–142, ISBN 978-0-444-63387-3

- Raspe, R. E. (1969), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, illustrated by Ronald Searle, New York: Pantheon Books

- Sadler’s Wells (1795), Songs, Recitatives, &c. in the Entertainment Baron Munchausen; or, Harlequin’s Travels, London: Sadler’s Wells Theatre

- Sadoul, Georges; Morris, Peter (1972), Dictionary of Films, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-02152-5

- Schwartz, Alvin (1990), Whoppers: Tall Tales and Other Lies, New York: Harper Trophy, ISBN 0-06-446091-6

- Seccombe, Thomas (1895), «Introduction», The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen, London: Lawrence and Bullen, pp. v–xxxvi

- Shull, Michael S.; Wilt, David E. (2004), Doing Their Bit: Wartime American Animated Short Films, 1939–1945, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-1555-7

- Venger, I.; Reisner, G. I., Russian Animation in Letter and Figures, retrieved 1 May 2015

- Викторова, Людмила (25 May 2004), В Калининграде живут «внучата Мюнхгаузена», BBC Russian (in Russian), BBC, retrieved 24 March 2015

- Волошина, Татьяна; Захаров, Александр (2006), Мюнхгаузен в Кёнигсберге, Внучата Мюнхгаузена (in Russian), retrieved 24 March 2015

- Wardrip-Fruin, Noah (2009), Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- Westfahl, Gary (2007), Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-3079-6

- Wiebel, Bernhard (September 2011), «Munchausen – the difference between live and literature», Munchausen-Library, retrieved 27 October 2016

- Willis, Donald C. (1984), Horror and Science Fiction Films, vol. III, Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-1723-4

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (2003), Ludwig Wittgenstein: Public and Private Occasions, ed. James Klagge & Alfred Nordmann, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

- Young, R. G. (1997), The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film: Ali Baba to Zombies, New York: Applause, ISBN 978-1-55783-269-6

- Ziolkowski, Jan M. (2007), Fairy Tales from Before Fairy Tales: The Medieval Latin Past of Wonderful Lies, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0472025220

- Zipes, Jack (2010), The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-85395-2

External links[edit]

- Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia (Raspe’s original 1785 text) at Wikisource

- The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen at Standard Ebooks

- The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen (Thomas Seccombe’s edition of a Kearsley text) at Project Gutenberg

The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Münchhausen (Gottfried August Bürger’s translation) at Project Gutenberg (in German)

- The Munchausen Museum in Latvia

- The Munchausen Library in Zurich

This article is about the literary character. For other uses, see Münchhausen.

| Baron Munchausen | |

|---|---|

Gustave Doré’s portrait of Baron Munchausen |

|

| First appearance | Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia (1785) |

| Created by | Rudolf Erich Raspe |

| Portrayed by |

|

| Voiced by |

|

| Based on | Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen (1720–1797) |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | Lügenbaron («Baron of Lies») |

| Title | Baron |

| Nationality | German |

Baron Munchausen (;[1][2][a] German: [ˈmʏnçˌhaʊzn̩]) is a fictional German nobleman created by the German writer Rudolf Erich Raspe in his 1785 book Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. The character is loosely based on a real baron, Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen.

Born in Bodenwerder, Electorate of Hanover, the real-life Münchhausen fought for the Russian Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739. Upon retiring in 1760, he became a minor celebrity within German aristocratic circles for telling outrageous tall tales based on his military career. After hearing some of Münchhausen’s stories, Raspe adapted them anonymously into literary form, first in German as ephemeral magazine pieces and then in English as the 1785 book, which was first published in Oxford by a bookseller named Smith. The book was soon translated into other European languages, including a German version expanded by the poet Gottfried August Bürger. The real-life Münchhausen was deeply upset at the development of a fictional character bearing his name, and threatened legal proceedings against the book’s publisher. Perhaps fearing a libel suit, Raspe never acknowledged his authorship of the work, which was only established posthumously.

The fictional Baron’s exploits, narrated in the first person, focus on his impossible achievements as a sportsman, soldier, and traveller; for instance: riding on a cannonball, fighting a forty-foot crocodile, and travelling to the Moon. Intentionally comedic, the stories play on the absurdity and inconsistency of Munchausen’s claims, and contain an undercurrent of social satire. The earliest illustrations of the character, perhaps created by Raspe himself, depict Munchausen as slim and youthful, although later illustrators have depicted him as an older man, and have added the sharply beaked nose and twirled moustache that have become part of the character’s definitive visual representation. Raspe’s book was a major international success, becoming the core text for numerous English, continental European, and American editions that were expanded and rewritten by other writers. The book in its various revised forms remained widely read throughout the 19th century, especially in editions for young readers.

Versions of the fictional Baron have appeared on stage, screen, radio, and television, as well as in other literary works. Though the Baron Munchausen stories are no longer well-known in many English-speaking countries, they are still popular in continental Europe. The character has inspired numerous memorials and museums, and several medical conditions and other concepts are named after him.

Historical figure[edit]

The real-life Münchhausen circa 1740, as a cuirassier in Riga, by G. Bruckner

Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen was born on 11 May 1720 in Bodenwerder, Electorate of Hanover.[5] He was a younger son of the «Black Line» of Rinteln-Bodenwerder, an aristocratic family in the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg.[6] His cousin, Gerlach Adolph von Münchhausen,[7] was the founder of the University of Göttingen and later the Prime Minister of the Electorate of Hanover.[8] Münchhausen started as a page to Anthony Ulrich II of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and followed his employer to the Russian Empire during the Russo-Austro–Turkish War (1735–39).[5] In 1739, he was appointed a cornet in the Russian cavalry regiment, the Brunswick-Cuirassiers.[5] On 27 November 1740, he was promoted to lieutenant.[6] He was stationed in Riga, but participated in two campaigns against the Turks in 1740 and 1741. In 1744 he married Jacobine von Dunten, and in 1750 he was promoted to Rittmeister (cavalry captain).[5]

In 1760 Münchhausen retired to live as a Freiherr at his estates in Bodenwerder, where he remained until his death in 1797.[5][9] It was there, especially at parties given for the area’s aristocrats, that he developed a reputation as an imaginative after-dinner storyteller, creating witty and highly exaggerated accounts of his adventures in Russia. Over the ensuing thirty years, his storytelling abilities gained such renown that he frequently received visits from travelling nobles wanting to hear his tales.[10] One guest described Münchhausen as telling his stories «cavalierly, indeed with military emphasis, yet without any concession to the whimsicality of the man of the world; describing his adventures as one would incidents which were in the natural course of events».[11] Rather than being considered a liar, Münchhausen was seen as an honest man.[5] As another contemporary put it, Münchhausen’s unbelievable narratives were designed not to deceive, but «to ridicule the disposition for the marvellous which he observed in some of his acquaintances».[12]

Münchhausen’s wife Jacobine von Dunten died in 1790.[13] In January 1794, Münchhausen married Bernardine von Brunn, fifty-seven years his junior.[13] Von Brunn reportedly took ill soon after the marriage and spent the summer of 1794 in the spa town of Bad Pyrmont, although contemporary gossip claimed that she spent her time dancing and flirting.[13] Von Brunn gave birth to a daughter, Maria Wilhemina, on 16 February 1795, nine months after her summer trip. Münchhausen filed an official complaint that the child was not his, and spent the last years of his life in divorce proceedings and alimony litigation.[13] Münchhausen died childless on 22 February 1797.[5]

Fictionalization[edit]

The Baron entertaining guests, from a series of postcards by Oskar Herrfurth.

The fictionalized character was created by a German writer, scientist, and con artist, Rudolf Erich Raspe.[14][15] Raspe probably met Hieronymus von Münchhausen while studying at the University of Göttingen,[7] and may even have been invited to dine with him at the mansion at Bodenwerder.[14] Raspe’s later career mixed writing and scientific scholarship with theft and swindling; when the German police issued advertisements for his arrest in 1775, he fled continental Europe and settled in England.[16]

In his native German language, Raspe wrote a collection of anecdotes inspired by Münchhausen’s tales, calling the collection «M-h-s-nsche Geschichten» («M-h-s-n Stories»).[17] It remains unclear how much of Raspe’s material comes directly from the Baron, but the majority of the stories are derived from older sources,[18] including Heinrich Bebel’s Facetiæ (1508) and Samuel Gotthold Lange’s Deliciæ Academicæ (1765).[19] «M-h-s-nsche Geschichten» appeared as a feature in the eighth issue of the Vade mecum für lustige Leute (Handbook for Fun-loving People), a Berlin humor magazine, in 1781. Raspe published a sequel, «Noch zwei M-Lügen» («Two more M-Fibs»), in the tenth issue of the same magazine in 1783.[17] The hero and narrator of these stories was identified only as «M-h-s-n», keeping Raspe’s inspiration partly obscured while still allowing knowledgeable German readers to make the connection to Münchhausen.[20] Raspe’s name did not appear at all.[17]

In 1785, while supervising mines at Dolcoath in Cornwall, Raspe adapted the Vade mecum anecdotes into a short English-language book, this time identifying the narrator of the book as «Baron Munchausen».[21] Other than the anglicization of Münchhausen to «Munchausen», Raspe this time made no attempt to hide the identity of the man who had inspired him, though he still withheld his own name.[22]

Portrait of Rudolf Erich Raspe, creator of the fictional Baron

This English edition, the first version of the text in which Munchausen appeared as a fully developed literary character,[23] had a circuitous publication history. It first appeared anonymously as Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, a 49-page book in 12mo size, published in Oxford by the bookseller Smith in late 1785 and sold for a shilling.[24] A second edition released early the following year, retitled Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Sporting Adventures of Baron Munnikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen, added five more stories and four illustrations; though the book was still anonymous, the new text was probably by Raspe, and the illustrations may have been his work as well.[25]

By May 1786, Raspe no longer had control over the book, which was taken over by a different publisher, G. Kearsley.[26][b] Kearsley, intending the book for a higher-class audience than the original editions had been, commissioned extensive additions and revisions from other hands, including new stories, twelve new engravings, and much rewriting of Raspe’s prose. This third edition was sold at two shillings, twice the price of the original, as Gulliver Revived, or the Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures of Baron Munikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen.[27]

Kearsley’s version was a marked popular success. Over the next few years, the publishing house issued further editions in quick succession, adding still more non-Raspe material along the way; even the full-length Sequel to the Adventures of Baron Munchausen, again not by Raspe and originally published in 1792 by a rival printer, was quickly subsumed into the body of stories. In the process of revision, Raspe’s prose style was heavily modified; instead of his conversational language and sportsmanlike turns of phrase, Kearsley’s writers opted for a blander and more formal tone imitating Augustan prose.[28] Most ensuing English-language editions, including even the major editions produced by Thomas Seccombe in 1895 and F. J. Harvey Darton in 1930, reproduce one of the rewritten Kearsley versions rather than Raspe’s original text.[29]

At least ten editions or translations of the book appeared before Raspe’s death in 1794.[30] Translations of the book into French, Spanish, and German were published in 1786.[22] The text reached the United States in 1805, expanded to include American topical satire by an anonymous Federalist writer, probably Thomas Green Fessenden.[31]

Gottfried August Bürger translated the book into German, and was often assumed to be its author.

The first German translation, Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, was made by the German Romantic poet Gottfried August Bürger. Bürger’s text is a close translation of Smith’s second edition, but also includes an interpolated story, based on a German legend called «The Six Wonderful Servants». Two new engravings were added to illustrate the interpolated material.[32] The German version of the stories proved to be even more popular than the English one.[33] A second German edition in 1788 included heavily altered material from an expanded Kearsley edition, and an original German sequel, Nachtrag zu den wunderbaren Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, was published in 1789. After these publications, the English and Continental versions of the Raspe text continued to diverge, following increasingly different traditions of included material.[34]

Raspe, probably for fear of a libel suit from the real-life Baron von Münchhausen, never admitted his authorship of the book.[35] It was often credited to Bürger,[19] sometimes with an accompanying rumor that the real-life Baron von Münchhausen had met Bürger in Pyrmont and dictated the entire work to him.[36] Another rumor, which circulated widely soon after the German translation was published, claimed that it was a competitive collaboration by three University of Göttingen scholars—Bürger, Abraham Gotthelf Kästner, and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg—with each of the three trying to outdo one another by writing the most unbelievable tale.[37] The scholar Johann Georg Meusel correctly credited Raspe for the core text, but mistakenly asserted that Raspe had written it in German and that an anonymous translator was responsible for the English version.[36] Raspe’s authorship was finally proven in 1824 by Bürger’s biographer, Karl Reinhard.[38][c]

In the first few years after publication, German readers widely assumed that the real-life Baron von Münchhausen was responsible for the stories.[22] According to witnesses, Münchhausen was deeply angry that the book had dragged his name into public consciousness and insulted his honor as a nobleman. Münchhausen became a recluse, refusing to host parties or tell any more stories,[22] and he attempted without success to bring legal proceedings against Bürger and the publisher of the translation.[40]

Publication history[edit]

The following tables summarize the early publication history of Raspe’s text, from 1785 to 1800. Unless otherwise referenced, information in the tables comes from the Munchausen bibliography established by John Patrick Carswell.[41]

| Raspe’s English text | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Edition | Title on title page | Publication | Contents |

| First | Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. Humbly dedicated and recommended to Country Gentlemen; and, if they please, to be repeated as their own, after a Hunt, at Horse Races, in Watering Places, and other such polite Assemblies, round the bottle and fireside | Oxford: Smith, 1786 [actually late 1785][d] | Adaptations by Raspe of fifteen of the sixteen anecdotes from «M-h-s-nsche Geschichten» and both of the anecdotes from «Noch zwei M-Lügen». |

| Second | Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Sporting Adventures of Baron Munnikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen; as he relates them over a Bottle when surrounded by his Friends. A New Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with four Views, engraved from the Baron’s own drawings | Oxford: Smith, [April] 1786 | Same as the First Edition, plus five new stories probably by Raspe and four illustrations possibly also by Raspe. |

| Third | Gulliver Revived, or the singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures of Baron Munikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen. The Third Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Views, engraved from the original designs | Oxford: G. Kearsley, [May] 1786 | Same stories and engravings as the Second Edition, plus new non-Raspe material and twelve new engravings. Many alterations are made to Raspe’s original text. |

| Fourth | Gulliver Revived containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, and on the Atlantic Ocean: Also an Account of a Voyage into the Moon, with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in that Planet, which are here called the Human Species, by Baron Munchausen. The Fourth Edition. Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Sixteen explanatory Views, engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, [July] 1786 | Same stories as the Third Edition, plus new material not by Raspe, including the cannonball ride, the journey with Captain Hamilton, and the Baron’s second trip to the Moon. Further alterations to Raspe’s text. Eighteen engravings, though only sixteen are mentioned on the title page. |

| Fifth | Gulliver Revived, containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Etna into the South Sea: Also an Account of a Voyage to the Moon and Dog Star, with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are here called the Human Species, by Baron Munchausen. The Fifth Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with a variety of explanatory Views, engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, 1787 | Same contents as the Fourth Edition, plus the trips to Ceylon (added at the beginning) and Mount Etna (at the end), and a new frontispiece. |

| Sixth | Gulliver Revived or the Vice of Lying properly exposed; containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Etna into the South Sea: also an Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species by Baron Munchausen. The Sixth Edition. Considerably enlarged and ornamented with a variety of explanatory Views engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, 1789[e] | Same contents as the Fifth Edition, plus a «Supplement» about a ride on an eagle and a new frontispiece. |

| Seventh | The Seventh Edition, Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Twenty Explanatory Engravings, from Original Designs. Gulliver Revived: or, the Vice of Lying properly exposed. Containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Aetna, into the South Sea. Also, An Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star; with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species. By Baron Munchausen | London: C. and G. Kearsley, 1793 | Same as the Sixth Edition. |

| Eighth | The Eighth Edition, Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Twenty Explanatory Engravings, from Original Designs. Gulliver Revived: or, the Vice of Lying properly exposed. Containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Aetna, into the South Sea. Also, An Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star; with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species. By Baron Munchausen | London: C. and G. Kearsley, 1799 | Same as the Sixth Edition. |

| Early Munchausen translations and sequels | |||

|---|---|---|---|