Всего найдено: 26

Подрабатываю копирайтером, заказчик спорит, что правильно «беларуский» писатель. Я написала в статье «белорусский«. Понятно, что Белоруссии нет, теперь Беларусь. Как по-русски правильно написать, кто прав? Заранее благодарна.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нормативно: белорусский.

Как правильно: белАрус или белОрус? белОруССкий или белАруСкий?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: белорус, белорусский, несмотря на то что сейчас официальное название государства – Республика Беларусь. Эти слова образованы от названия Белоруссия, продолжающего существовать в русском языке (пусть и не являющегося официальным).

Эти уральские края. Почему с маленькой буквы- уральские?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Прилагательные, образованные от географических названий, пишутся с прописной буквы, если они являются частью составных наименований — географических и административно-территориальных, индивидуальных имен людей, названий исторических эпох и событий, учреждений, архитектурных и др. памятников, военных округов и фронтов.

В остальных случаях они пишутся со строчной буквы.

Ср., напр.: невские берега, невские набережные и Александр Невский, Невский проспект, Невская битва; донское казачество и Дмитрий Донской, Донской монастырь; московские улицы, кварталы, московский образ жизни и Московская область, Московский вокзал (в Петербурге), Московская государственная консерватория; казанские достопримечательности и Казанский кремль, Казанский университет, Казанский собор (в Петербурге, Москве); северокавказская природа и Северо-Кавказский регион, Северо-Кавказский военный округ; 1-й Белорусский фронт, Потсдамская конференция, Санкт-Петербургский монетный двор, Великая Китайская стена, Большой Кремлёвский дворец.

Добрый вечер ! Подскажите, пожалуйста, сколько корней в слове белорусский?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В современном русском языке в слове белорусский один корень – белорус-.

Какое прилагательное можно образовать от слова «Беларусь»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В русском литературном языке существует только прилагательное белорусский, образованное от слова Белоруссия. Написание белорусский остается единственно правильным (несмотря на то что сейчас официальное название государства – Республика Беларусь, а название Белоруссия неофициальное).

Недавно на одном солидном переводческом сайте встретила слово «беларуский» в качестве названия ветки форума. Резануло. Понятно, что после развала Союза Белоруссия официально называется Республикой Беларусь, и, видимо, этим объясняется хождение в интернете этого прилагательного. Но что думает по этому поводу уважаемая Грамота.ру?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

По-русски правильно: белорусский, белорус. И слово Белоруссия в русском языке никуда не исчезло, оно продолжает употребляться как неофициальное название государства (в официальных текстах – Республика Беларусь).

Как правильно белорусский язык или беларуский?

я думала всегда, что белорусский, но со мной поделились такой статьей: http://gogo.by/news/184/.В самом ли деле, по правилам транслитерации мы должны говорить «беларуский» вместо «белорусский«?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

По-русски правильно: белорусский, белорус. И слово Белоруссия в русском языке никуда не исчезло, оно продолжает употребляться как неофициальное название государства.

Как писать сложное прилагательное «Балто-Белорусский«? Вторая часть слова пишется с прописной?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Обе части прилагательного пишутся со строчных букв: балто-белорусский. Ср. в составе наименования: Балто-белорусская конференция.

Здравствуйте! Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно: «белорусский» или «беларуский»? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Прилагательное — белорусский.

Добрый день!

Вопрос такой: если на письме употребляется название страны — Беларусь, то уместно ли называть народ белАрусами?

Насколько я понимаю, белОрус от БелОруссия.Заранее благодарю

за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нет, по-русски в любом случае правильно: белорус, белорусский.

Существует государство Молдавия. В нём живут молдаване. Однако словарь выдаёт и наличие государства Республика МолдОва. Не было бы логично утверждать, что в нём живут молдОване?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нет, поскольку русское слово молдаване образовано от русского названия страны – Молдавия. Республика Молдова – это название, используемое в официальных документах. Наличие этого официального наименования не отменяет существования в русском языке слова молдаване. Аналогично: Республика Беларусь (официальное название в документах), но белорусский, белорусы (эти слова образованы от слова Белоруссия, которое по-прежнему употребляется в неофициальных текстах).

Вот «нагуглила». Чем опровергните?

Всегда было сложно объяснить россиянину, почему меня коробит от «Белоруссия», почему как-то неправильно выглядит национальность «белорус» и не мог понять почему же мне интуитивно хочется написать «беларуский», если выглядит это слово «с ошибкой».

Согласно нормам русского языка – «БЕЛАРУС»

Одновременно с провозглашением суверенитета БССР в 1991 году – следовало рассмотреть вопрос о названии страны, так как, согласно международным нормам ООН, название страны должно писаться ПО ПРАВИЛАМ ЕЕ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ЯЗЫКА. То есть – в нашем случае – по нормам беларуской мовы. А прежнее название «Белоруссия» — было написанием по нормам русского языка, а не беларуского. В беларуском же должно звучать «Беларусь».

Это было равно крайне важно и для укрепления международного авторитета нашей страны (к тому же – члена-соучредителя ООН) и ее статуса суверенной державы. Ранее в английском, немецком и других языках наше название звучало не как «Белоруссия», а буквально как «БЕЛАЯ РОССИЯ» — то есть, даже не так, как в русском языке. Это «колониальное название» создавало неверные представления о Беларуси как о каком-то «туземном придатке» Российской Федерации, где живут россияне, а не беларусы, и где у народа российское этническое лицо, а не уникальное беларуское.

Существенно и то, что название «Белая Россия» создавало путаницу в иностранных МИДах, особенно стран Африки, Востока и Южной Америки, на что жаловались их представители в ООН.

Верховный Совет БССР 19 сентября 1991 года принял «Закон Белорусской Советской Социалистической Республики о названии Белорусской Советской Социалистической Республики». В этом Законе еще до распада СССР наша БССР была переименована в Республику Беларусь (мой перевод на русский):

«Белорусскую Советскую Социалистическую Республику далее называть «Республика Беларусь», а в укороченных и составных названиях – «Беларусь».

И обращаю внимание на продолжение текста этого Закона:

«Установить, что эти названия транслитеруются на другие языки в соответствии с беларуским звучанием».

Транслитерация (Transliteration) — перевод одной графической системы алфавита в другую, то есть передача букв одной письменности буквами другой. Что означает, например, для русского языка, что в нем нет больше никакой «Белоруссии», а обязана быть только и именно одна «Беларусь».

Сегодня во всех официальных международных мероприятиях (саммиты СНГ, спортивные соревнования, торговые соглашения и пр.) это строго соблюдается: есть только название «Беларусь». В паспортах и прочих документах РБ на русском языке – тоже только «Беларусь», никакой «Белоруссии».

Общероссийский классификатор стран мира OK (MK (ИСО 3166) 004—97) 025-2001 (ОКСМ) (принят и введен в действие постановлением Госстандарта РФ от 14 декабря 2001 г. № 529-ст) тоже категоричен: он предусматривает только формы «Республика Беларусь» и «Беларусь», а какая-то фантастическая «Белоруссия» им не предусмотрена – такой страны не существует.

Главным в Законе о названии страны является пункт о ТРАНСЛИТЕРАЦИИ ее названия на другие языки мира (включая русский). Дело в том, что некоторые страны такого пункта не имеют и потому могут по-разному называться в разных языках: например, в русском нет никакой Норге, а есть Норвегия, вместо Данмарк – Дания, Суоми – Финляндия, Дойчланд – Германия, вместо Летува – Литва. Ни Финляндия, ни Германия, ни Летува не заявляли о том, что их самоназвания Суоми, Дойчланд и Летува транслитеруются на другие языки – и не просили другие страны их отныне называть именно так. А вот Беларусь именно это заявила в своем Законе. И точно так в свое время Персия попросила называть её Ираном, Цейлон – Шри-Ланкой, Берег Слоновой Кости – Кот д’ Ивуаром, Бирма – Мьянмой, Северная Родезия – Замбией, Бенгалия – Бангладеш, Верхняя Вольта – Буркина Фасо. Именно под новыми названиями эти страны известны сегодня во всем мире, в том числе в РФ.

Если бы противники термина «Беларусь» в русском языке показали нам, что Россия пренебрегает этими правилами и продолжает называть Иран Персией, а Шри-Ланку Цейлоном – то в таком случае их мнение имело бы какую-то аргументацию. А в данном случае такая избирательность непонятна: чем же мы хуже Ирана или Шри-Ланки, если в России СМИ и просто россияне не желают признавать наше новое название и упрямо именуют старым несуществующим «Белоруссия»?

Тем не менее термин «Беларусь» все-таки СТАЛ ЯЗЫКОВОЙ РЕАЛИЕЙ русского языка, так как активно используется в ООН (где один из языков – русский) и всем государственным аппаратом РФ: всеми министерствами. Не менее строго следит за использованием термина «Беларусь» телеканал СНГ «Мир» (который равно следит за использованием «Молдова» вместо «Молдавия», «Туркменистан» вместо «Туркмения» и т.п.), а также телепрограммы и печатные СМИ Союзного государства Беларуси и России.

Таким образом, слово «Беларусь» стало частью русской лексики. Причем – используется не столько в быту, сколько в официозе, а это означает тенденцию вытеснения со временем старого слова «Белоруссия» и в разговорном русском. Пишется слово именно через «а», как этого и требует наш Закон о транслитерации названия страны – нигде в официальных документах РФ не используется слово «Белорусь» — ЕГО ПРОСТО НЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ в русском языке.

В спорах со мной на эту тему многие российские «тугодумы» соглашались, что слово «Беларусь» стало частью русского языка из-за его использования российским официозом, но все равно упорствовали: мол, это слово «неправильное», а правильно – делать русскую соединительную «о».

Но если слово только ТРАНСЛИТИРУЕТСЯ на русский язык – то о каких же «нормах русского языка» можно говорить? Вот прямая аналогия: французское Кот д’ Ивуар. Почему же никто равно не возмущается и не говорит, что по-русски правильно писать по-старому «Берег Слоновой Кости»? Или беларуский язык – это не такой же иностранный язык, как французский? Или Беларусь – это не суверенное государство, как Кот д’ Ивуар, а часть РФ?

Коль «Беларусь» — языковая реалия русского языка, то как по правилам русского языка должно образовываться название гражданина Беларуси?

Правильно: белАрус.Здесь возражения о соединительной «о» вообще неуместны, так как изначальное слово «Беларусь» образовано не по правилам русского языка. А на этот счет в русском языке свои нормы: корнем слова является в таком случае все слово «Беларусь» (а не два тут корня).

Вместо того чтобы воспринимать слово «Беларусь» как ЗАИМСТВОВАННОЕ из другого языка, россияне по инерции его делят на два корня – что противоречит правилам русского языка о заимствованных словах.

Слово «БЕЛАРУСКИЙ»

Вначале приведу мнения беларуских специалистов в этой теме.

Адам МАЛЬДИС, доктор филологических наук, профессор, почетный председатель Международной ассоциации беларусистов:

«Если слово «Белоруссия» имеет свою традицию (например, газета «Советская Белоруссия»), это одно. Но когда речь идет о названии страны, закрепленном в Конституции и международных документах, тут однозначно — Беларусь. Заключение топонимической комиссии ООН только подтверждает это. На мой взгляд, правильным было бы писать «беларус», а не «белорус», и «беларуский» вместо «белорусский». Думаю, со временем мы к этому придем».

Александр ШАБЛОВСКИЙ, кандидат филологических наук, старший научный сотрудник Института языкознания им. Я. Коласа НАН Беларуси:

«Введение в русскоязычный оборот слова «Беларусь» считаю полностью правомерным и оправданным. Что касается рекомендаций Института русского языка, то у нас в Беларуси свой ориентир — Институт языкознания имени Якуба Коласа. И в этом вопросе мы все придерживаемся совершенно определенной позиции: только Беларусь! Россиянам, естественно, мы диктовать не можем.

Если говорить о производных от слова «Беларусь», то, конечно, последовательным было бы написание «беларус» и «беларуский». Но в этом вопросе мы принимаем позицию российских академиков, которые в своих оценках очень традиционны. Еще в 1933 году выдающийся русский лингвист Евгений Дмитриевич Поливанов писал: «Чем более развит язык, тем меньше он развивается». Потому не знаю, закрепится ли в будущем «беларус» и «беларуский». Ведь для того, чтобы у слова «кофе» в русском языке помимо мужского появился и средний род, потребовалось почти 100 лет! Так это всего лишь род…»

На самом деле слово «белАрус» просто производно от слова «Беларусь» в русском языке – что было показано выше. Но есть и другой аспект темы, который не стали детально раскрывать некоторые русские специалисты. А заключается он в следующем.

Наш Закон 1991 года о введении названия страны Беларусь и его транслитерации на все языки мира означал ОДНОВРЕМЕННО и ИЗМЕНЕНИЕ ВСЕХ СЛОВ В ЯЗЫКАХ МИРА, ПРОИЗВОДНЫХ ОТ НАЗВАНИЯ СТРАНЫ.

То есть, мало изменить название страны с «Белая Россия» (на английском, немецком и пр.) на «Беларусь». Надо еще, чтобы везде изменили название НАРОДА с «белых русских» на «беларусов», а его языка с «белого русского» на «беларуский язык». Это тоже крайне важно – как и само изменение названия страны. Ведь ранее на английском наш язык назывался «белорашен лэнгвич», а теперь стал называться «беларус лэнгвич». Житель БССР был «белорашен», стал «беларус». (Кстати, в Беларуси при преподавании иностранных языков по-прежнему учат советским терминам типа «белорашен», что и устарело, и ошибка, и не соответствует названию страны Беларусь.)

Как видим, СМЕНА ПОНЯТИЙ КАРДИНАЛЬНАЯ. Отныне никакой «рашен»!

С 1991 года во всем мире нас больше не называют с добавкой «рашен»: в энциклопедиях ЕС, США, Китая и прочих стран мира: страна Беларусь, от ее названия производится там название народа и его языка – с корнем «Беларус».

Следуя этому правилу, и в русском языке равно транслитерации подлежит не только слово «Беларусь», но и производные понятия народа этой страны и ее языка – как политическое значение, НЕОТДЕЛИМОЕ от названия страны. Они РАВНО ТРАНСЛИТИРУЮТСЯ в рамках транслитерации названия страны «Беларусь». Таким образом, автоматически подлежат транслитерации слова «беларус» и «беларуский язык».

Это тоже строго в рамках правил русского языка. Равно как слово «Беларусь» является заимствованным транслитерацией в русском языке и не подлежит делению на два корня – точно так заимствованное слово «беларуский» является КОРНЕМ до буквы «к» (согласно правилам русского языка, заимствованные слова являются корнями до своих окончаний).

И, как заимствованное слово русского языка, не подлежит аналогично ни делению на два корня, ни правилу русского языка по удвоению «с» между «с» в корне и суффиксом. Так как этого правила нет в исходом для транслитерации беларуском языке – а транслитерация, напомню, сохраняет нормы грамматики исходного языка СВОЕЙ СТРАНЫ. А главное: само слово «беларуский» — заимствованное, и в нем русский язык не имеет права вычленять суффиксы.

Что касается окончаний (автор статьи в журнале «Родина» утрировал: «ну нет, тогда уж «беларускава»), то вот как раз в этом вопросе, согласно нормам русского языка, должны уже соблюдаться нормы русского языка. Заимствованные в русский язык слова сохраняют свои иностранные корни, но имеют падежные формы уже по русским правилам. Так что и тут «мимо»…

По материалам Вадима Ростова

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Так вопрос-то в чем? Что опровергать? Современное название государства в русском языке: Республика Беларусь. Однако прилагательное пишется по-прежнему: белорусский. И станция метро в Москве «Белорусская».

нужно ли переводить названия улиц с русского языка на белорусский, украинский, если остальной текст написан соответственно на белорусском или украинском языке?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Некоторые названия улиц по традиции перводятся (например, Крещатик, а также улицы, названные в честь известных людей). Но в иных случаях перевод не требуется, достаточно корректной графической передачи.

Несмотря на обилие просмотренных вопросов-ответов по теме, все же задам вопрос: чем логически обусловлена такая, абсолютно противоречащая грамматическим законам, пара, как «БелАрусь — белОрусский«? Не планируется каких-либо сдвигов в этом плане -в пользу правил русской грамматики и элементарной логической последовательности? Или абсурд потихоньку переходит из быта — в лингвистику?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Дело в том, что прилагательное белорусский образовано от слова Белоруссия, а не от слова Беларусь, ставшего частью официального названия страны (Республика Беларусь). Аналогичный пример: Республика Молдова (официальное название), но молдаване (т. к. это слово образовано от русского названия – Молдавия).

Здравствуйте!

Вдогонку к вопросу № 266913.

Прилагательные всё-таки какие будут: белорусские или беларуские?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верное прилагательное: белорусский, белорусские.

Вот как правильно на русском языке написать белОрус или белАрус, белОруССкий или белАруСкий?

Могу быть уверен, что многие сейчас не согласятся с тем, что писать, например слово белОруССкая теперь правильно как белАруСкая. И тот же Word будет не согласен с этим утверждением и подчеркнет при написании слова беларус красной волнистой линией при проверке орфографии. Но подождите, не все так просто. Прочитайте ниже статью, где идет разъяснение и пройдитесь по ссылкам и думаю мнение изменится.

Скопировано отсюда

Вадим РОСТОВ

«Аналитическая газета «Секретные исследования»

Как правильно писать – Белоруссия или Беларусь, белорус или беларус, белорусский или беларуский?

Мы уже обсуждали эту тему в статье «Беларуские национальные реалии» (№10, 2008). Ряд беларуских изданий и писателей сегодня используют термины «беларус» и «беларуский», это стало известно в России – и вызвало там неприятие и издевки. Видимо, из-за того, что в России (да и в Беларуси) многие не понимают самой сути вопроса.

Например, летом этого года известный московский журнал «Родина» выступил с суровой критикой книги «История имперских отношений: беларусы и русские» (под редакцией А.Е. Тараса), многие главы которой публиковались на страницах нашей газеты. «Изобличающая» эту книгу статья кандидата исторических наук Юрия Борисенка «Как белый аист уткой обернулся» начинается так:

«И дня не проходит в этом чудесном подлунном мире, чтобы кто-нибудь хитроумный не подкинул новое симпатичное словечко. Не знаю точно, как там с диалектами амхарского или суахили, но русскому языку часто достаётся и по нескольку раз на дню. Вот и минский многостаночник гуманитарного фронта (составитель, переводчик и научный редактор в одном лице) Анатолий Ефимович Тарас обогатил намедни великий и могучий одним чудесным существительным и одним не менее увлекательным прилагательным. Бдительная корректура может спать спокойно: в объёмистой книге с загадочным названием «История имперских отношений» «беларусы» и «беларуский» упорно пишутся через «а». Но «жжот» наш герой почему-то только в этом пункте, а ведь так заманчиво продолжить и разослать сию книжицу (третьим, так и быть, изданием) во все школы Российской Федерации, сделать из 300 экземпляров несколько десятков тысяч. Несчастные школьники вмиг освободятся от оков опостылевшего правописания: прогрессивный принцип «беларуского языка» (ну нет, тогда уж «беларускава») «как слышится, так и пишется» расширится неимоверно — сгодятся и классические белорусские «Масква» и «карова», и неологизмы из толщи народной — типа «абразавания», «балонскава працэса» и «ЯГЭ» (к слову, проницательный читатель на пороге лета 2009 года узрит здесь нечто пугающе-сказочное и прав будет: «защекочут до икоты и на дно уволокут», а дно у нашего «абразавания» болотистое, так сразу и не выплывешь)».

На самом деле эти великодержавные издевки выдают безграмотность самого автора статьи в журнале «Родина», так как по нормам русского языка надо писать «беларус», а не «белорус».

СОГЛАСНО НОРМАМ РУССКОГО ЯЗЫКА – «БЕЛАРУС»

Одновременно с провозглашением суверенитета БССР в 1991 году – следовало рассмотреть вопрос о названии страны, так как, согласно международным нормам ООН, название страны должно писаться ПО ПРАВИЛАМ ЕЕ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ЯЗЫКА. То есть – в нашем случае – по нормам беларуской мовы. А прежнее название «Белоруссия» – было написанием по нормам русского языка, а не беларуского. В беларуском же должно звучать «Беларусь».

Это было равно крайне важно и для укрепления международного авторитета нашей страны (к тому же – члена-соучредителя ООН) и ее статуса суверенной державы. Ранее в английском, немецком и других языках наше название звучало не как «Белоруссия», а буквально как «БЕЛАЯ РОССИЯ» – то есть, даже не так, как в русском языке. Это «колониальное название» создавало неверные представления о Беларуси как о каком-то «туземном придатке» Российской Федерации, где живут россияне, а не беларусы, и где у народа российское этническое лицо, а не уникальное беларуское.

Существенно и то, что название «Белая Россия» создавало путаницу в иностранных МИДах, особенно стран Африки, Востока и Южной Америки, на что жаловались их представители в ООН.

Верховный Совет БССР 19 сентября 1991 года принял «Закон Белорусской Советской Социалистической Республики о названии Белорусской Советской Социалистической Республики». В этом Законе еще до распада СССР наша БССР была переименована в Республику Беларусь (мой перевод на русский):

«Белорусскую Советскую Социалистическую Республику далее называть «Республика Беларусь», а в укороченных и составных названиях – «Беларусь».

И обращаю внимание на продолжение текста этого Закона:

«Установить, что эти названия транслитеруются на другие языки в соответствии с беларуским звучанием».

Транслитерация (Transliteration) – перевод одной графической системы алфавита в другую, то есть передача букв одной письменности буквами другой. Что означает, например, для русского языка, что в нем нет больше никакой «Белоруссии», а обязана быть только и именно одна «Беларусь».

Сегодня во всех официальных международных мероприятиях (саммиты СНГ, спортивные соревнования, торговые соглашения и пр.) это строго соблюдается: есть только название «Беларусь». В паспортах и прочих документах РБ на русском языке – тоже только «Беларусь», никакой «Белоруссии».

Общероссийский классификатор стран мира OK (MK (ИСО 3166) 004—97) 025-2001 (ОКСМ) (принят и введен в действие постановлением Госстандарта РФ от 14 декабря 2001 г. № 529-ст) тоже категоричен: он предусматривает только формы «Республика Беларусь» и «Беларусь», а какая-то фантастическая «Белоруссия» им не предусмотрена – такой страны не существует.

Главным в Законе о названии страны является пункт о ТРАНСЛИТЕРАЦИИ ее названия на другие языки мира (включая русский). Дело в том, что некоторые страны такого пункта не имеют и потому могут по-разному называться в разных языках: например, в русском нет никакой Норге, а есть Норвегия, вместо Данмарк – Дания, Суоми – Финляндия, Дойчланд – Германия, вместо Летува – Литва. Ни Финляндия, ни Германия, ни Летува не заявляли о том, что их самоназвания Суоми, Дойчланд и Летува транслитеруются на другие языки – и не просили другие страны их отныне называть именно так. А вот Беларусь именно это заявила в своем Законе. И точно так в свое время Персия попросила называть её Ираном, Цейлон – Шри-Ланкой, Берег Слоновой Кости – Кот д’ Ивуаром, Бирма – Мьянмой, Северная Родезия – Замбией, Бенгалия – Бангладеш, Верхняя Вольта – Буркина Фасо. Именно под новыми названиями эти страны известны сегодня во всем мире, в том числе в РФ.

Если бы противники термина «Беларусь» в русском языке показали нам, что Россия пренебрегает этими правилами и продолжает называть Иран Персией, а Шри-Ланку Цейлоном – то в таком случае их мнение имело бы какую-то аргументацию. А в данном случае такая избирательность непонятна: чем же мы хуже Ирана или Шри-Ланки, если в России СМИ и просто россияне не желают признавать наше новое название и упрямо именуют старым несуществующим «Белоруссия»?

Тем не менее термин «Беларусь» все-таки СТАЛ ЯЗЫКОВОЙ РЕАЛИЕЙ русского языка, так как активно используется в ООН (где один из языков – русский) и всем государственным аппаратом РФ: всеми министерствами. Не менее строго следит за использованием термина «Беларусь» телеканал СНГ «Мир» (который равно следит за использованием «Молдова» вместо «Молдавия», «Туркменистан» вместо «Туркмения» и т.п.), а также телепрограммы и печатные СМИ Союзного государства Беларуси и России.

Таким образом, слово «Беларусь» стало частью русской лексики. Причем – используется не столько в быту, сколько в официозе, а это означает тенденцию вытеснения со временем старого слова «Белоруссия» и в разговорном русском. Пишется слово именно через «а», как этого и требует наш Закон о транслитерации названия страны – нигде в официальных документах РФ не используется слово «Белорусь» – ЕГО ПРОСТО НЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ в русском языке.

В спорах со мной на эту тему многие российские «тугодумы» соглашались, что слово «Беларусь» стало частью русского языка из-за его использования российским официозом, но все равно упорствовали: мол, это слово «неправильное», а правильно – делать русскую соединительную «о».

Но если слово только ТРАНСЛИТИРУЕТСЯ на русский язык – то о каких же «нормах русского языка» можно говорить? Вот прямая аналогия: французское Кот д’ Ивуар. Почему же никто равно не возмущается и не говорит, что по-русски правильно писать по-старому «Берег Слоновой Кости»? Или беларуский язык – это не такой же иностранный язык, как французский? Или Беларусь – это не суверенное государство, как Кот д’ Ивуар, а часть РФ?

Коль «Беларусь» – языковая реалия русского языка, то как по правилам русского языка должно образовываться название гражданина Беларуси? Правильно: белАрус.

Здесь возражения о соединительной «о» вообще неуместны, так как изначальное слово «Беларусь» образовано не по правилам русского языка. А на этот счет в русском языке свои нормы: корнем слова является в таком случае все слово «Беларусь» (а не два тут корня).

Вместо того чтобы воспринимать слово «Беларусь» как ЗАИМСТВОВАННОЕ из другого языка, россияне по инерции его делят на два корня – что противоречит правилам русского языка о заимствованных словах. Таким образом, издевки Юрия Борисенка в журнале «Родина» по поводу слова «беларус» – безграмотны с точки зрения правил русского языка.

А как быть со словом «беларуский»? Напомню, автор статьи на нем изрядно «попрыгал»: «Несчастные школьники вмиг освободятся от оков опостылевшего правописания: прогрессивный принцип «беларуского языка» (ну нет, тогда уж «беларускава») «как слышится, так и пишется» расширится неимоверно — сгодятся и классические белорусские «Масква» и «карова», и неологизмы из толщи народной…»

Давайте и с этим словом разберемся.

СЛОВО «БЕЛАРУСКИЙ»

Вначале приведу мнения беларуских специалистов в этой теме.

Адам МАЛЬДИС, доктор филологических наук, профессор, почетный председатель Международной ассоциации беларусистов:

«Если слово «Белоруссия» имеет свою традицию (например, газета «Советская Белоруссия»), это одно. Но когда речь идет о названии страны, закрепленном в Конституции и международных документах, тут однозначно — Беларусь. Заключение топонимической комиссии ООН только подтверждает это. На мой взгляд, правильным было бы писать «беларус», а не «белорус», и «беларуский» вместо «белорусский». Думаю, со временем мы к этому придем».

Александр ШАБЛОВСКИЙ, кандидат филологических наук, старший научный сотрудник Института языкознания им. Я. Коласа НАН Беларуси:

«Введение в русскоязычный оборот слова «Беларусь» считаю полностью правомерным и оправданным. Что касается рекомендаций Института русского языка, то у нас в Беларуси свой ориентир — Институт языкознания имени Якуба Коласа. И в этом вопросе мы все придерживаемся совершенно определенной позиции: только Беларусь! Россиянам, естественно, мы диктовать не можем.

Если говорить о производных от слова «Беларусь», то, конечно, последовательным было бы написание «беларус» и «беларуский». Но в этом вопросе мы принимаем позицию российских академиков, которые в своих оценках очень традиционны. Еще в 1933 году выдающийся русский лингвист Евгений Дмитриевич Поливанов писал: «Чем более развит язык, тем меньше он развивается». Потому не знаю, закрепится ли в будущем «беларус» и «беларуский». Ведь для того, чтобы у слова «кофе» в русском языке помимо мужского появился и средний род, потребовалось почти 100 лет! Так это всего лишь род…»

На мой взгляд, автор московского журнала «Родина» вообще ничего в вопросе не понял и посчитал, что мы тут просто «переводим» русские слова на «прогрессивный принцип «беларуского языка» (ну нет, тогда уж «беларускава») «как слышится, так и пишется»».

На самом деле слово «белАрус» просто производно от слова «Беларусь» в русском языке – что было показано выше. Но есть и другой аспект темы, который не стали детально раскрывать в приведенных цитатах Адам Мальдис и Александр Шабловский. А заключается он в следующем.

Наш Закон 1991 года о введении названия страны Беларусь и его транслитерации на все языки мира означал ОДНОВРЕМЕННО и ИЗМЕНЕНИЕ ВСЕХ СЛОВ В ЯЗЫКАХ МИРА, ПРОИЗВОДНЫХ ОТ НАЗВАНИЯ СТРАНЫ.

То есть, мало изменить название страны с «Белая Россия» (на английском, немецком и пр.) на «Беларусь». Надо еще, чтобы везде изменили название НАРОДА с «белых русских» на «беларусов», а его языка с «белого русского» на «беларуский язык». Это тоже крайне важно – как и само изменение названия страны. Ведь ранее на английском наш язык назывался «белорашен лэнгвич», а теперь стал называться «беларус лэнгвич». Житель БССР был «белорашен», стал «беларус». (Кстати, в Беларуси при преподавании иностранных языков по-прежнему учат советским терминам типа «белорашен», что и устарело, и ошибка, и не соответствует названию страны Беларусь.)

Как видим, СМЕНА ПОНЯТИЙ КАРДИНАЛЬНАЯ. Отныне никакой «рашен»!

С 1991 года во всем мире нас больше не называют с добавкой «рашен»: в энциклопедиях ЕС, США, Китая и прочих стран мира: страна Беларусь, от ее названия производится там название народа и его языка – с корнем «Беларус».

Следуя этому правилу, и в русском языке равно транслитерации подлежит не только слово «Беларусь», но и производные понятия народа этой страны и ее языка – как политическое значение, НЕОТДЕЛИМОЕ от названия страны. Они РАВНО ТРАНСЛИТИРУЮТСЯ в рамках транслитерации названия страны «Беларусь». Таким образом, автоматически подлежат транслитерации слова «беларус» и «беларуский язык».

Это тоже строго в рамках правил русского языка. Равно как слово «Беларусь» является заимствованным транслитерацией в русском языке и не подлежит делению на два корня – точно так заимствованное слово «беларуский» является КОРНЕМ до буквы «к» (согласно правилам русского языка, заимствованные слова являются корнями до своих окончаний).

И, как заимствованное слово русского языка, не подлежит аналогично ни делению на два корня, ни правилу русского языка по удвоению «с» между «с» в корне и суффиксом. Так как этого правила нет в исходом для транслитерации беларуском языке – а транслитерация, напомню, сохраняет нормы грамматики исходного языка СВОЕЙ СТРАНЫ. А главное: само слово «беларуский» – заимствованное, и в нем русский язык не имеет права вычленять суффиксы.

Что касается окончаний (автор статьи в журнале «Родина» утрировал: «ну нет, тогда уж «беларускава»), то вот как раз в этом вопросе, согласно нормам русского языка, должны уже соблюдаться нормы русского языка. Заимствованные в русский язык слова сохраняют свои иностранные корни, но имеют падежные формы уже по русским правилам. Так что и тут «мимо»…

СМЕНА НАЗВАНИЙ

Международная конференция экспертов ООН по топонимике, состоявшаяся 9-13 октября 2006 года Таллинне, постановила: беларуские названия на иностранных картах ДОЛЖНЫ ПЕРЕДАВАТЬСЯ С НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЙ ФОРМЫ НАПИСАНИЯ. Это значит, что на немецких автодорожных картах вместо Weissrusland (еще не исправленная там для автодорожников калька с Белоруссии) появится Belarus’ (с апострофом, показателем мягкости). Вместо Gomel, Mogilev и Vitebsk — Homiel’, Mahiliou и Viciebsk.

Российские великодержавники могут сколько угодно подтрунивать над «неграмотными» терминами «Беларусь», «беларус» и «беларуский», но, согласно требованиям ООН, на всех автодорожных картах мира – и РФ в том числе – будет не русский вариант названия городов Беларуси, а БЕЛАРУСКИЙ. С беларуского языка. Это уже давно принято, это уже реализуется – к этому надо привыкать.

Конечно, иные товарищи и после этого решения экспертов ООН будут цепляться и настаивать великодержавно, что по-английски ПРАВИЛЬНО писать не Homiel’, а Gomel, не Mahiliou и Viciebsk – а Mogilev и Vitebsk. То есть – в ретрансляции с русского языка, а не с беларуского. А более всего будут выступать против того, чтобы на российских автодорожных картах появились Махилеу, Вицебск и прочее «новое» для русского языка.

Однако это решение ООН обязательно и для России – поэтому там будут изменены на автодорожных картах названия беларуских населенных пунктов в соответствии с их написанием на языке их страны. Не только Беларуси, но и Украины. А в отношении стран Балтии на автодорожных картах на русском языке давно отражаются как раз их местные названия топонимов – примечательный момент (например: не Ковно, а Каунас, не Вильно, а Вильнюс – хотя еще в романе А. Толстого «Гиперболоид инженера Гарина» писалось «Ковно» и «Вильно»).

Но раз не «Ковно», а «Каунас» – то тогда и Махилеу, а не Могилев.

«БЕЛАЯ РУСЬ» – НЕЛЕПЫЙ ТЕРМИН

Теперь о термине «Белая Русь», который сегодня активно используется как якобы синоним «Беларуси». Его эксплуатируют в песнях, в пафосных статьях, в названии водки и общественных объединений. На самом деле Беларусь не расшифровывается как «Белая Русь» – это глубокая ошибка. Ведь точно так мы не ищем корня «Русь» в названиях Пруссия или Боруссия. Во-первых, НИГДЕ ни в одном документе страны не зафиксировано, что термин «Беларусь» может подменяться термином «Белая Русь» – так что такая подмена юридически незаконна. Во-вторых, Беларусь НИКОГДА не была никакой «Русью» – так что с исторической точки зрения такая подмена просто абсурдна.

Русью была Украина – и ее народ назывался русинами. На 70-90 лет Полоцкое государство было захвачено киевскими князьями – но эта оккупация не делает Полоцкое государство «Русью», а наш народ – русинами (то есть украинцами).

К моменту кровавого захвата Полоцка киевским князем Владимиром (Вальдемаром) там правила шведская династия Рогволода. С 1190 в Полоцке правит выбранный полочанами на княжение ятвяг Мингайла или Мигайла, затем его сын Гинвилло (Юрий в православии, умер в Орше в 1199), потом его сын Борис, женатый на дочке поморского (Померании) князя Болеслава. (Любопытная подробность: поморский князь Богуслав I в 1214 году имел печать, которая почти идентична печати ВКЛ «Погоня», а также титуловался как princeps Liuticorum, то есть «князь лютицкий», о чем подробнее в моей статье «Откуда появилась Литва?» в №24 за 2008 г. и №№1, 2, 3 за 2009 г.) Потом княжил его сын Василько. (См. книгу В.У. Ластовского «Короткая история Беларуси», Вильня, 1910.)

Итак, потомки князя Изяслава, рожденного в результате изнасилования Владимиром шведки Рогнеды, правили в Полоцке до 1181 года (при этом уже через 70-90 лет полностью освободились от Киевского ига – то есть от Русского ига). С 1181 по 1190 была Полоцкая Республика. А затем вплоть до вхождения Полоцкого Государства в состав ВКЛ им правили нерусские князья-ятвяги, не имевшие никакой связи с Киевской Русью и не вступавшие в брак с киевскими родами. Учитывая, что князьям Полоцка служили ятвяжско-полоцкие дружины, – то ни о какой «Руси» в Полоцке не может быть и речи.

Никакие Рюриковичи в Полоцке с 1181 года уже не правили. Но раз нет Рюриковичей – то и нет никакой Руси.

Кроме того, я весьма сомневаюсь, что акт изнасилования шведки Рогнеды киевским князем Владимиром – на глазах ее связанных родителей и братьев, которых после изнасилования сей русский князь убил, – якобы являлся АКТОМ ПРИОБЩЕНИЯ ПОЛОЦКА К РУСИ.

Кстати говоря, киевского князя Владимира Русская православная Церковь сделала святым за то, что он затем крестил Русь. Как святым может быть человек, совершивший изнасилование девушки на глазах ее семьи и убивший затем всю ее семью, – удивительная загадка представлений РПЦ о МОРАЛЬНЫХ НОРМАХ…

Сей святой РПЦ и в будущем креститель Руси – бежит сразу при штурме Полоцка насиловать шведскую девственницу, а в результате АКТА рождается сын Изяслав, который хочет своего святого «героического» папашку убить – и едва это не сделал. Но при чем тут беларусы? Один демагог, беларуский профессор «идеологической школы ЦК КПСС» писал, что «брак князя Владимира с Рогнедой нес беларусам древнерусское сознание». Как изнасилование украинским князем шведки может нести беларусам «древнерусское сознание»? Уму не постижимо…

Иные возражают, что Владимир был не украинским князем, а «руським» – но ведь и никаких «беларусов» тогда не было: были только кривичи и ятвяги – западно-балтские племена. От того, что кривичами правили шведы Рогволод и Рогнеда, – они не становились автоматически шведами. И точно так с захватом Полоцка киевлянами – кривичи не стали ни «руськими», ни «украинцами», а с вхождением в состав Речи Посполитой – не стали от этого поляками. Но зато с 1230-х с миграцией к нам поморских лютичей во главе с князьями Булевичами и Рускевичами сначала ятвяги, а затем и кривичи именуют себя ЛИТВИНАМИ и ЛЮТВОЙ-ЛИТВОЙ. Именно эти новые названия заменяют наши старые – Ятва, Дайнова, Крива. И именно с этого периода начинает складываться наш этнос как объединение ятвягов, дайновичей и кривичей. И если, скажем, кто-то кривичей еще может относить к «данникам Древней Руси» (то есть к данникам варягов, ибо кривичи лежали на пути «из варяг в греки»), то вот ни Ятву ятвягов (столицы Новогрудок и Дарагичин в Белосточчине), ни Дайнову дайновичей (столица Лида) – никто в здравом уме «Русью» называть не станет. А ведь это – предки всех нынешних беларусов Минской, Гродненской и Брестской областей!

При первом разделе Речи Посполитой Екатерина II называет захваченный у нас кусок ВКЛ (Полоцк, Витебск, Могилев) новым названием «Белорусская губерния», а остальную часть нынешней Беларуси, захваченную позже, именует «Литовской губернией». То есть – исторической Литвой (до 1840 года). Уже один этот факт именования нас со стороны России – ярко показывает, что даже при царизме большая часть нынешней Беларуси еще называлась Литвой. То есть, в первой половине XIX веке якобы не было нашего народа, а было на территории нынешней Беларуси ДВА РАЗНЫХ народа: в Западной Беларуси (Литовской губернии) продолжали жить литвины ВКЛ, а в Восточной Беларуси (Белорусской губернии) – якобы жили уже «белорусы».

Это – ненаучный нонсенс, который одиозно противоречит тому, что пишет Энциклопедия «Беларусь», Минск, 1995, стр. 529: «Процессы консолидации беларуской народности в беларускую Нацию начались в 16 – начале 17 века».

Простите, о каких процессах может идти речь, если Нация была с разделами Речи Посполитой «разбита» на 70 лет царизмом на две части – «Литву» и «Белоруссию» одноименных губерний? И куда делась литвинская Нация Литовской губернии – Минска, Гродно, Бреста, Вильно? Энциклопедия «забыла», как называлась формируемая беларуская нация «в 16 – начале 17 века». То есть, в эпоху Статутов ВКЛ, в которых нет НИ СЛОВА о каких-то «беларусах», зато все жители территории нынешней Беларуси там именуются только литвинами. На самом деле формировалась нация под другим названием – не беларуская, а литвинская.

Что уже СТРАННО с научной точки зрения. Давайте посмотрим на эту чехарду наших названий в рамках представлений этой же Энциклопедии, которая на стр. 529 указывает, что процесс формирования беларуской нации окончился в 1910-1920-х годах.

Формирование нашей нации шло, примерно, с 1501 по 1920 год. Это 420 лет, из которых наша формируемая нация ВСЯ называлась «литвинами» и «Литвой» 271 год, потом ее ТОЛЬКО восточная часть именовалась в процессе этого формирования нации «беларусами» 148 лет, а ее западная часть именовалась «беларусами» лишь 80 лет.

Как видим, в процессе формирования нашей общей нации Беларуси восточные беларусы назывались «литвинами» всю первую половину этого периода, а западные беларусы назывались «литвинами» более 80% этого периода. Это ясно показывает, что наша нация – формирование которой в последних этапах было исковеркано имперской политикой русификации со стороны царизма – нами создавалась как нация литвинов Литвы, а не как некая нам навязанная российской оккупацией «нация белорусов Белоруссии». Навязанная именно с лишением нас своей Государственности ВКЛ и всех наших прав и свобод, всего нашего исторического и культурного наследия нашей независимой от царизма жизни.

Всю лживость царского термина «Белоруссия», насильно подменившего после наших антироссийских восстаний самоназвания «Литва» и «литвины», выпукло показывает тот факт, что после нашего очередного восстания 1863-1864 годов генерал-губернатор Муравьев запретил и навязанное нам царизмом колониальное название «Белоруссия», вводя вместо него – до февраля 1917 года! – название «Северо-западный край». Это создает уже ТРЕТЬЕ название для нашей нации: «северо-западчане». Что ничем не лучше и ничем не хуже, чем равно царское «белорусы».

А ведь и не удивляет: в ином «историческом раскладе» ныне Энциклопедия «Беларусь» написала бы на стр. 529: «Процессы консолидации северо-западной народности в северо-западную Нацию начались в 16 – начале 17 века». И, мол, наши предки писали и говорили на древне-северо-западном языке. Вроде бы – правда. А по сути – издевательство.

Становится ли от этого историческая Литва – «Русью»? Да нет, конечно! Поэтому абсолютно нелепо Беларусь «раскрывать» термином «Белая Русь», так как в «матрешке» под названием «Беларусь» скрывается никакая не «Русь», а угробленная и русифицированная царизмом ЛИТВА и ее нация литвинов. То есть – наши предки, которые и создавали нашу нацию. Нацию ВКЛ и Литвы – а вовсе не какой-то «Руси» или тем более, России с ее «северо-западными краями».

* * *

Что же касается юридической точки зрения, то ныне популярный (по невежеству) термин «Белая Русь» АБСОЛЮТНО противоречит ДУХУ, СОДЕРЖАНИЮ и СМЫСЛУ Закона Верховного Совета БССР 19 сентября 1991 года о названии страны как Республика Беларусь.

Напомню то, о чем говорилось выше: смысл Закона о нашем новом названии был в том, чтобы нас больше не именовали колониальным названием «Weissrusland», буквально – «Белая Россия» в немецком, английском, французском и прочих языках мира, включая русский. Смысл Закона в том, что мы – не часть «Rusland», а самостоятельное государство Беларусь самостоятельной беларуской нации – соучредителя ООН.

Термин «Белая Русь» – полностью перечеркивает и этот Закон, и все наши усилия быть самостоятельным Государством. Он – калька с «Weissrusland».

Вся беда в том, что беларусы, использующие термин «Белая Русь», в силу, как мне кажется, своих ограниченных знаний на эту тему – просто НЕ ОЩУЩАЮТ и НЕ ПОНИМАЮТ, что тем самым нарушают Закон Верховного Совета БССР 19 сентября 1991 года о названии страны как Республика Беларусь. Они этим термином «Белая Русь» называют беларускую нацию – нацией «белых россиян», а саму Беларусь называют «Weissrusland». Что и есть на немецком языке эта пресловутая «Белая Русь».

Но мы для всего мира – уже давно не Weissrusland, мы – Belarus’. Хотя бы потому, что так название нашей страны пишется на НАШЕМ языке.

Ссылки по теме:

ТАК «БЕЛАРУС» ИЛИ «БЕЛОРУС»?

http://www.my-minsk.ru/novosti-respubliki/6002-tak-belarus-ili-belorus.html

http://www.secret-r.net/forum/viewtopic.php?t=623&

| Belarusian | |

|---|---|

| беларуская мова | |

| Pronunciation | [bʲɛlaˈruskaja ˈmɔva][bʲɛlaˈruskaja] |

| Native to | Belarus |

| Ethnicity | Belarusians |

|

Native speakers |

5.1 million[1] (2009 census) 6.3 million L2 speakers (2009 census)[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Proto-Indo-European

|

|

Writing system |

Cyrillic (Belarusian alphabet) Belarusian Latin alphabet Belarusian Braille |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

|

|

Recognised minority |

|

| Regulated by | National Academy of Sciences of Belarus |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | be |

| ISO 639-2 | bel |

| ISO 639-3 | bel |

| Glottolog | bela1254 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-eb < 53-AAA-e |

Belarusian-speaking world |

|

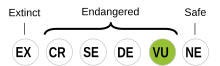

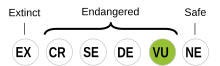

Belarusian is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Belarusian (Belarusian: беларуская мова, romanized: biełaruskaja mova, IPA: [bʲɛlaˈruskaja ˈmɔva]) is an East Slavic language. It is the native language of many Belarusians and one of the two official state languages in Belarus. Additionally, it is spoken in some parts of Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, and Ukraine by Belarusian minorities in those countries.

Before Belarus gained independence in 1991, the language was only known in English as Byelorussian or Belorussian, the compound term retaining the English-language name for the Russian language in its second part, or alternatively as White Russian. Following independence, it became known as Belarusan and since 1995 as Belarusian in English.[5][6]

As one of the East Slavic languages, Belarusian shares many grammatical and lexical features with other members of the group. To some extent, Russian, Rusyn, Ukrainian, and Belarusian retain a degree of mutual intelligibility. Its predecessor stage is known in Western academia as Ruthenian (14th to 17th centuries), in turn descended from what is referred to in modern linguistics as Old East Slavic (10th to 13th centuries).

In the first Belarus Census of 1999, the Belarusian language was declared as a «language spoken at home» by about 3,686,000 Belarusian citizens (36.7% of the population).[7][8] About 6,984,000 (85.6%) of Belarusians declared it their «mother tongue». Other sources, such as Ethnologue, put the figure at approximately 2.5 million active speakers.[6][9] According to a study done by the Belarusian government in 2009, 72% of Belarusians speak Russian at home, while Belarusian is actively used by only 11.9% of Belarusians (others speak a mixture of Russian and Belarusian, known as Trasianka). Approximately 29.4% of Belarusians can write, speak, and read Belarusian, while 52.5% can only read and speak it.[10] In the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, the Belarusian language is stated to be vulnerable.[11]

Names[edit]

There are a number of names under which the Belarusian language has been known, both contemporary and historical. Some of the most dissimilar are from the Old Belarusian period.

Official, romanised[edit]

- Belarusian (also spelled Belarusan,[12] (;[13] Belarussian) – derived from the name of the country «Belarus», officially approved for use abroad by the Belarusian MFA (c. 1992) and promoted since then.

- Byelorussian (also spelled Belorussian, Bielorussian) – derived from the Russian-language name of the country «Byelorussia» (Russian: Белоруссия), used officially (in the Russian language) in the times of the USSR (1922–1991) and, later, in the Russian Federation[citation needed].

- White Ruthenian (and its equivalents in other languages) – literally, a word-by-word translation of the parts of the composite word Belarusian. The term «White Ruthenian» with reference to language has appeared in English-language texts since at least 1921.[14]

Alternative[edit]

- Great Lithuanian (вялікалітоўская (мова)) – proposed and used by Yan Stankyevich since the 1960s, intended to part with the «diminishing tradition of having the name related to the Muscovite tradition of calling the Belarusian lands» and to pertain to the «great tradition of Belarusian statehood».

- Kryvian or Krivian (крывіцкая/крывічанская/крыўская (мова), Polish: język krewicki) – derived from the name of the Slavonic tribe Krivichi, one of the main tribes in the foundations of the forming of the Belarusian nation. Created and used in the 19th century by Belarusian Polish-speaking writers Jaroszewicz, Narbut, Rogalski, Jan Czeczot. Strongly promoted by Vacłaŭ Łastoŭski.

Vernacular[edit]

- Simple (простая (мова)) or local (тутэйшая (мова)) – used mainly in times preceding the common recognition of the existence of the Belarusian language, and nation in general. Supposedly, the term can still be encountered up to the end of the 1930s, e.g., in Western Belarus.

- Simple Black Ruthenian (Russian: простой чернорусский) – used in the beginning of the 19th century by the Russian researcher Baranovski and attributed to contemporary vernacular Belarusian.[15]

Phonology[edit]

Although closely related to other East Slavic languages, especially Ukrainian, Belarusian phonology is distinct in a number of ways. The phoneme inventory of the modern Belarusian language consists of 45 to 54 phonemes: 6 vowels and 39 to 48 consonants, depending on how they are counted. When the nine geminate consonants are excluded as mere variations, there are 39 consonants, and excluding rare consonants further decreases the count. The number 48 includes all consonant sounds, including variations and rare sounds, which may be phonetically distinct in the modern Belarusian language.

Alphabet[edit]

The Belarusian alphabet is a variant of the Cyrillic script, which was first used as an alphabet for the Old Church Slavonic language. The modern Belarusian form was defined in 1918, and consists of thirty-two letters. Before that, Belarusian had also been written in the Belarusian Latin alphabet (Łacinka / Лацінка), the Belarusian Arabic alphabet (by Lipka Tatars) and the Hebrew alphabet (by Belarusian Jews).[16] The Glagolitic script was used, sporadically, until the 11th or 12th century.

There are several systems of romanizing (transliterating) written Belarusian texts; see Romanization of Belarusian. The Belarusian Latin alphabet is rarely used.

Grammar[edit]

Standardized Belarusian grammar in its modern form was adopted in 1959, with minor amendments in 1985 and 2008. It was developed from the initial form set down by Branisłaŭ Taraškievič (first printed in Vilnius, 1918), and it is mainly based on the Belarusian folk dialects of Minsk-Vilnius region. Historically, there have been several other alternative standardized forms of Belarusian grammar.

Belarusian grammar is mostly synthetic and partly analytic, and overall quite similar to Russian grammar. Belarusian orthography, however, differs significantly from Russian orthography in some respects, due to the fact that it is a phonetic orthography that closely represents the surface phonology, whereas Russian orthography represents the underlying morphophonology.

The most significant instance of this is found in the representation of vowel reduction, and in particular akanje, the merger of unstressed /a/ and /o/, which exists in both Russian and Belarusian. Belarusian always spells this merged sound as ⟨a⟩, whereas Russian uses either ⟨a⟩ or ⟨o⟩, according to what the «underlying» phoneme is (determined by identifying the related words where the vowel is being stressed or, if no such words exist, by written tradition, mostly but not always conforming to etymology). This means that Belarusian noun and verb paradigms, in their written form, have numerous instances of alternations between written ⟨a⟩ and ⟨o⟩, whereas no such alternations exist in the corresponding written paradigms in Russian. This can significantly complicate the foreign speakers’ task of learning these paradigms; on the other hand, though, it makes spelling easier for native speakers.

An example illustrating the contrast between the treatment of akanje in Russian and Belarusian orthography is the spelling of the word for “products; food”:

- In Ukrainian: продукти (pronounced “produkty”, IPA: [proˈduktɪ])

- In Russian: продукты (pronounced “pradukty”, IPA: [prɐˈduktɨ])

- In Belarusian: прадукты (pronounced “pradukty”, IPA: [praˈduktɨ])

Ethnographic Map of Slavic and Baltic Languages

Dialects[edit]

Dialects

North-Eastern

Middle

South-Western

West Polesian

Lines

Area of Belarusian language (1903, Karski)[17]

Eastern border of western group of Russian dialects (1967, Zaharova, Orlova)

Border between Belarusian and Russian or Ukrainian (1980, Bevzenk)

Besides the standardized lect, there are two main dialects of the Belarusian language, the North-Eastern and the South-Western. In addition, there is a transitional Middle Belarusian dialect group and the separate West Polesian dialect group.

The North-Eastern and the South-Western dialects are separated by a hypothetical line Ashmyany–Minsk–Babruysk–Homyel, with the area of the Middle Belarusian dialect group placed on and along this line.

The North-Eastern dialect is chiefly characterized by the «soft sounding R» (мякка-эравы) and «strong akanye» (моцнае аканне), and the South-Western dialect is chiefly characterized by the «hard sounding R» (цвёрда-эравы) and «moderate akanye» (умеранае аканне).

The West Polesian dialect group is separated from the rest of the country by the conventional line Pruzhany–Ivatsevichy–Telekhany–Luninyets–Stolin.

Classification and relationship to other languages[edit]

There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility among the Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian languages.[18]

Within East Slavic, the Belarusian language is most closely related to Ukrainian.[19]

History[edit]

The modern Belarusian language was redeveloped on the base of the vernacular spoken remnants of the Ruthenian language, surviving in the ethnic Belarusian territories in the 19th century. The end of the 18th century (the times of the Divisions of Commonwealth) is the usual conventional borderline between the Ruthenian and Modern Belarusian stages of development.

By the end of the 18th century, (Old) Belarusian was still common among the minor nobility in eastern part, in the territory of present-day Belarus, of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (hereafter GDL). Jan Czeczot in the 1840s had mentioned that even his generation’s grandfathers preferred speaking (Old) Belarusian.[20] According to A. N. Pypin, the Belarusian language was spoken in some areas among the minor nobility during the 19th century.[21] In its vernacular form, it was the language of the smaller town dwellers and of the peasantry and it had been the language of oral folklore. Teaching in Belarusian was conducted mainly in schools run by the Basilian order.

The development of Belarusian in the 19th century was strongly influenced by the political conflict in the territories of the former GDL, between the Russian Imperial authorities, trying to consolidate their rule over the «joined provinces», and the Polish and Polonized nobility, trying to bring back its pre-Partitions rule[22] (see also Polonization in times of Partitions).

One of the important manifestations of this conflict was the struggle for ideological control over the educational system. The Polish and Russian languages were being introduced and re-introduced, while the general state of the people’s education remained poor until the very end of the Russian Empire.[23]

In summary, the first two decades of the 19th century had seen the unprecedented prosperity of Polish culture and language in the former GDL lands, and had prepared the era of such famous Polish writers as Adam Mickiewicz and Władysław Syrokomla. The era had seen the effective completion of the Polonization of the lowest level of the nobility, the further reduction of the area of use of contemporary Belarusian, and the effective folklorization of Belarusian culture.[24]

Due both to the state of the people’s education and to the strong positions of Polish and Polonized nobility, it was only after the 1880s–1890s that the educated Belarusian element, still shunned because of «peasant origin», began to appear in state offices.[25]

In 1846, ethnographer Pavel Shpilevskiy prepared a Belarusian grammar (using the Cyrillic alphabet) on the basis of the folk dialects of the Minsk region. However, the Russian Academy of Sciences refused to print his submission, on the basis that it had not been prepared in a sufficiently scientific manner.

From the mid-1830s ethnographic works began to appear, and tentative attempts to study the language were instigated (e.g. Shpilevskiy’s grammar). The Belarusian literary tradition began to re-form, based on the folk language, initiated by the works of Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich. See also: Jan Czeczot, Jan Barszczewski.[26]

At the beginning of the 1860s, both the Russian and Polish parties in Belarusian lands had begun to realise that the decisive role in the upcoming conflicts was shifting to the peasantry, overwhelmingly Belarusian. So a large amount of propaganda appeared, targeted at the peasantry and written in Belarusian;[27] notably, the anti-Russian, anti-Tsarist, anti-Eastern Orthodox «Manifesto» and the first newspaper Mużyckaja prauda (Peasants’ Truth) (1862–1863) by Konstanty Kalinowski, and anti-Polish, anti-Revolutionary, pro-Orthodox booklets and poems (1862).[28]

The advent of the all-Russian «narodniki» and Belarusian national movements (late 1870s–early 1880s) renewed interest in the Belarusian language (See also: Homan (1884), Bahushevich, Yefim Karskiy, Dovnar-Zapol’skiy, Bessonov, Pypin, Sheyn, Nasovič). The Belarusian literary tradition was also renewed (see also: F. Bahushevich). It was in these times that F. Bahushevich made his famous appeal to Belarusians: «Do not forsake our language, lest you pass away» (Belarusian: Не пакідайце ж мовы нашай, каб не ўмёрлі).

The first dictionary of the modern Belarusian language authored by Nasovič was published in 1870. In the editorial introduction to the dictionary, it is noted that:

“The Belarusian local tongue, which dominates a vast area from the Nioman and the Narew to the Upper Volga and from the Western Dvina to the Prypiac and the Ipuc and which is spoken by inhabitants of the North-Western and certain adjacent provinces, or those lands that were in the past settled by the Kryvic tribe, has long attracted the attention of our philologists because of those precious remains of the ancient [Ruthenian] language that survived in that tongue”.[29]

In course of the 1897 Russian Empire Census, about 5.89 million people declared themselves speakers of Belarusian.

The end of the 19th century, however, still showed that the urban language of Belarusian towns remained either Polish or Russian. The same census showed that towns with a population greater than 50,000 had fewer than a tenth Belarusian speakers. This state of affairs greatly contributed to a perception that Belarusian was a «rural» and «uneducated» language.

However, the census was a major breakthrough for the first steps of the Belarusian national self-awareness and identity, since it clearly showed to the Imperial authorities and the still-strong Polish minority that the population and the language were neither Polish nor Russian.

| Total Population | Belarusian (Beloruskij) | Russian (Velikoruskij) | Polish (Polskij) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vilna | 1,591,207 | 891,903 | 78,623 | 130,054 |

| Vitebsk | 1,489,246 | 987,020 | 198,001 | 50,377 |

| Grodno | 1,603,409 | 1,141,714 | 74,143 | 161,662 |

| Minsk | 2,147,621 | 1,633,091 | 83,999 | 64,617 |

| Mogilev | 1,686,764 | 1,389,782 | 58,155 | 17,526 |

| Smolensk | 1,525,279 | 100,757 | 1,397,875 | 7,314 |

| Chernigov | 2,297,854 | 151,465 | 495,963 | 3,302 |

| Privislinsky Krai | 9,402,253 | 29,347 | 335,337 | 6,755,503 |

| All Empire | 125,640,021 | 5,885,547 | 55,667,469 | 7,931,307 |

| * See also: Administrative-territorial division of Belarus and bordering lands in 2nd half 19 cent. (right half-page) Archived 2019-09-30 at the Wayback Machine and Ethnic composition of Belarus and bordering lands (prep. by Mikola Bich on the basis of 1897 data) Archived 2019-09-30 at the Wayback Machine |

1900s–1910s[edit]

The rising influence of Socialist ideas advanced the emancipation of the Belarusian language still further (see also: Belarusian Socialist Assembly, Circle of Belarusian People’s Education and Belarusian Culture, Belarusian Socialist Lot, Socialist Party «White Russia», Alaiza Pashkievich, Nasha Dolya). The fundamental works of Yefim Karskiy marked a turning point in the scientific perception of Belarusian. The ban on publishing books and papers in Belarusian was officially removed (25 December 1904). The unprecedented surge of national feeling in the 20th century, especially among the workers and peasants, particularly after the events of 1905,[30] gave momentum to the intensive development of Belarusian literature and press (See also: Naša niva, Yanka Kupala, Yakub Kolas).

Grammar[edit]

During the 19th and early 20th century, there was no normative Belarusian grammar. Authors wrote as they saw fit, usually representing the particularities of different Belarusian dialects. The scientific groundwork for the introduction of a truly scientific and modern grammar of the Belarusian language was laid down by the linguist Yefim Karskiy.

By the early 1910s, the continuing lack of a codified Belarusian grammar was becoming intolerably obstructive in the opinion of uniformitarian prescriptivists. Then Russian academician Shakhmatov, chair of the Russian language and literature department of St. Petersburg University, approached the board of the Belarusian newspaper Naša niva with a proposal that a Belarusian linguist be trained under his supervision in order to be able to create documentation of the grammar. Initially, the famous Belarusian poet Maksim Bahdanovich was to be entrusted with this work. However, Bahdanovich’s poor health (tuberculosis) precluded his living in the climate of St. Petersburg, so Branislaw Tarashkyevich, a fresh graduate of the Vilnya Liceum No. 2, was selected for the task.

In the Belarusian community, great interest was vested in this enterprise. The already famous Belarusian poet Yanka Kupala, in his letter to Tarashkyevich, urged him to «hurry with his much-needed work». Tarashkyevich had been working on the preparation of the grammar during 1912–1917, with the help and supervision of Shakhmatov and Karskiy. Tarashkyevich had completed the work by the autumn of 1917, even moving from the tumultuous Petrograd of 1917 to the relative calm of Finland in order to be able to complete it uninterrupted.

By the summer of 1918, it became obvious that there were insurmountable problems with the printing of Tarashkyevich’s grammar in Petrograd: a lack of paper, type and qualified personnel. Meanwhile, his grammar had apparently been planned to be adopted in the workers’ and peasants’ schools of Belarus that were to be set up, so Tarashkyevich was permitted to print his book abroad. In June 1918, he arrived in Vilnius, via Finland. The Belarusian Committee petitioned the administration to allow the book to be printed. Finally, the first edition of the «Belarusian grammar for schools» was printed (Vil’nya, 1918).

There existed at least two other contemporary attempts at codifying the Belarusian grammar. In 1915, Rev. Balyaslaw Pachopka had prepared a Belarusian grammar using the Latin script. Belarusian linguist S. M. Nyekrashevich considered Pachopka’s grammar unscientific and ignorant of the principles of the language. But Pachopka’s grammar was reportedly taught in an unidentified number of schools, from 1918 for an unspecified period. Another grammar was supposedly jointly prepared by A. Lutskyevich and Ya. Stankyevich, and differed from Tarashkyevich’s grammar somewhat in the resolution of some key aspects.

1914–1917[edit]

On 22 December 1915, Paul von Hindenburg issued an order on schooling in German Army-occupied territories in the Russian Empire (Ober Ost), banning schooling in Russian and including the Belarusian language in an exclusive list of four languages made mandatory in the respective native schooling systems (Belarusian, Lithuanian, Polish, Yiddish). School attendance was not made mandatory, though. Passports at this time were bilingual, in German and in one of the «native languages».[31] Also at this time, Belarusian preparatory schools, printing houses, press organs were opened (see also: Homan (1916)).

1917–1920[edit]

After the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, the Belarusian language became an important factor in political activities in the Belarusian lands (see also: Central Council of Belarusian Organisations, Great Belarusian Council, First All-Belarusian Congress, Belnatskom). In the Belarusian People’s Republic, Belarusian was used as the only official language (decreed by Belarusian People’s Secretariat on 28 April 1918). Subsequently, in the Belarusian SSR, Belarusian was decreed to be one of the four (Belarusian, Polish, Russian, and Yiddish) official languages (decreed by Central Executive Committee of BSSR in February 1921).

1920–1930[edit]

Soviet Belarus[edit]

A decree of 15 July 1924 confirmed that the Belarusian, Russian, Yiddish and Polish languages had equal status in Soviet Belarus.[32]

In the BSSR, Tarashkyevich’s grammar had been officially accepted for use in state schooling after its re-publication in unchanged form, first in 1922 by Yazep Lyosik under his own name as Practical grammar. Part I, then in 1923 by the Belarusian State Publishing House under the title Belarusian language. Grammar. Ed. I. 1923, also by «Ya. Lyosik».

In 1925, Lyosik added two new chapters, addressing the orthography of compound words and partly modifying the orthography of assimilated words. From this point on, Belarusian grammar had been popularized and taught in the educational system in that form. The ambiguous and insufficient development of several components of Tarashkyevich’s grammar was perceived to be the cause of some problems in practical usage, and this led to discontent with the grammar.

In 1924–25, Lyosik and his brother Anton Lyosik prepared and published their project of orthographic reform, proposing a number of radical changes. A fully phonetic orthography was introduced. One of the most distinctive changes brought in was the principle of akanye (Belarusian: а́канне), wherein unstressed «o», pronounced in both Russian and Belarusian as /a/, is written as «а».

The Belarusian Academic Conference on Reform of the Orthography and Alphabet was convened in 1926. After discussions on the project, the Conference made resolutions on some of the problems. However, the Lyosik brothers’ project had not addressed all the problematic issues, so the Conference was not able to address all of those.

As the outcome of the conference, the Orthographic Commission was created to prepare the project of the actual reform. This was instigated on 1 October 1927, headed by S. Nyekrashevich, with the following principal guidelines of its work adopted:

- To consider the resolutions of the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926) non-mandatory, although highly competent material.

- To simplify Tarashkyevich’s grammar where it was ambiguous or difficult in use, to amend it where it was insufficiently developed (e.g., orthography of assimilated words), and to create new rules if absent (orthography of proper names and geographical names).

During its work in 1927–29, the Commission had actually prepared the project for spelling reform. The resulting project had included both completely new rules and existing rules in unchanged and changed forms, some of the changes being the work of the Commission itself, and others resulting from the resolutions of the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926), re-approved by the Commission.

Notably, the use of the Ь (soft sign) before the combinations «consonant+iotified vowel» («softened consonants»), which had been previously denounced as highly redundant (e.g., in the proceedings of the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926)), was cancelled. However, the complete resolution of the highly important issue of the orthography of unstressed Е (IE) was not achieved.

Both the resolutions of the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926) and the project of the Orthographic Commission (1930) caused much disagreement in the Belarusian academic environment. Several elements of the project were to be put under appeal in the «higher (political) bodies of power».

West Belarus[edit]

In West Belarus, under Polish rule, the Belarusian language was at a disadvantage. Schooling in the Belarusian language was obstructed, and printing in Belarusian experienced political oppression.[33]

The prestige of the Belarusian language in the Western Belarus during the period hinged significantly on the image of the BSSR being the «true Belarusian home».[34][verification needed] This image, however, was strongly disrupted by the «purges» of «national-democrats» in BSSR (1929–30) and by the subsequent grammar reform (1933).

Tarashkyevich’s grammar was re-published five times in Western Belarus. However, the 5th edition (1929) (reprinted verbatim in Belarus in 1991 and often referred to) was the version diverging from the previously published one, which Tarashkyevich had prepared disregarding the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926) resolutions. (Тарашкевіч 1991, Foreword)

1930s[edit]

Soviet Belarus[edit]

In 1929–30, the Communist authorities of Soviet Belarus made a series of drastic crackdowns against the supposed «national-democratic counter-revolution» (informally «nats-dems» (Belarusian: нац-дэмы)). Effectively, entire generations of Socialist Belarusian national activists in the first quarter of the 20th century were wiped out of political, scientific and social existence. Only the most famous cult figures (e.g. Yanka Kupala) were spared.

However, a new power group in Belarusian science quickly formed during these power shifts, under the virtual leadership of the Head of the Philosophy Institute of the Belarusian Academy of Sciences, academician S. Ya. Vol’fson (С. Я. Вольфсон). The book published under his editorship, Science in Service of Nats-Dems’ Counter-Revolution (1931), represented the new spirit of political life in Soviet Belarus.

1933 reform of Belarusian grammar[edit]

The Reform of Belarusian Grammar (1933) had been brought out quite unexpectedly, supposedly [Stank 1936], with the project published in the central newspaper of the Belarusian Communist Party (Zviazda) on 1933-06-28 and the decree of the Council of People’s Commissars (Council of Ministers) of BSSR issued on 1933-08-28, to gain the status of law on 1933-09-16.

There had been some post-facto speculations, too, that the 1930 project of the reform (as prepared by people who were no longer seen as politically «clean»), had been given for the «purification» to the «nats-dems» competition in the Academy of Sciences, which would explain the «block» nature of the differences between the 1930 and 1933 versions. Peculiarly, Yan Stankyevich in his notable critique of the reform [Stank 1936] failed to mention the 1930 project, dating the reform project to 1932.

The reform resulted in the grammar officially used, with further amendments, in Byelorussian SSR and modern Belarus. Sometimes this grammar is called the official grammar of the Belarusian language, to distinguish it from the pre-reform grammar, known as the classic grammar or Taraškievica. It is also known as narkamauka, after the word narkamat, a Belarusian abbreviation for People’s Commissariat (ministry). The latter term bears a derogatory connotation.

The officially announced causes for the reform were:

- The pre-1933 grammar was maintaining artificial barriers between the Russian and Belarusian languages.

- The reform was to cancel the influences of the Polonisation corrupting the Belarusian language.

- The reform was to remove the archaisms, neologisms and vulgarisms supposedly introduced by the «national-democrats».

- The reform was to simplify the grammar of the Belarusian language.

The reform had been accompanied by a fervent press campaign directed against the «nats-dems not yet giving up.»

The decree had been named On Changing and Simplifying Belarusian Spelling («Аб зменах і спрашчэнні беларускага правапісу»), but the bulk of the changes had been introduced into the grammar. Yan Stankyevich in his critique of the reform talked about 25 changes, with one of them being strictly orthographical and 24 relating to both orthography and grammar. [Stank 1936]

Many of the changes in the orthography proper («stronger principle of AH-ing,» «no redundant soft sign,» «uniform nye and byez«) were, in fact, simply implementations of earlier proposals made by people who had subsequently suffered political suppression (e.g., Yazep Lyosik, Lastowski, Nyekrashevich, 1930 project).[35][36] [Padluzhny 2004]

The morphological principle in the orthography had been strengthened, which also had been proposed in 1920s.[35]

The «removal of the influences of the Polonisation» had been represented, effectively, by the:

- Reducing the use of the «consonant+non-iotified vowel» in assimilated Latinisms in favour of «consonant+iotified vowel,» leaving only Д, Т, Р unexceptionally «hard.»

- Changing the method of representing the sound «L» in Latinisms to another variant of the Belarusian sound Л (of 4 variants existing), rendered with succeeding non-iotified vowels instead of iotified.

- Introducing the new preferences of use of the letters Ф over Т for theta, and В over Б for beta, in Hellenisms. [Stank 1936]

The «removing of the artificial barriers between the Russian and Belarusian languages» (virtually the often-quoted «Russification of the Belarusian language», which may well happen to be a term coined by Yan Stankyevich) had, according to Stankyevich, moved the normative Belarusian morphology and syntax closer to their Russian counterparts, often removing from use the indigenous features of the Belarusian language. [Stank 1936]

Stankyevich also observed that some components of the reform had moved the Belarusian grammar to the grammars of other Slavonic languages, which would hardly be its goal. [Stank 1936]

West Belarus[edit]

In West Belarus, there had been some voices raised against the reform, chiefly by the non-Communist/non-socialist wing of the Belarusian national scene. Yan Stankyevich was named to the Belarusian Scientific Society, Belarusian National Committee and Society of the Friends of Belarusian Linguistics at Wilno University. Certain political and scientific groups and figures went on using the pre-reform orthography and grammar, however, thus multiplying and differing versions.

However, the reformed grammar and orthography had been used, too, for example during the process of Siarhei Prytytski in 1936.

Second World War[edit]

During the Occupation of Belarus by Nazi Germany (1941–1944), the Belarusian collaborationists influenced newspapers and schools to use the Belarusian language. This variant did not use any of the post-1933 changes in vocabulary, orthography and grammar. Much publishing in Belarusian Latin script was done. In general, in the publications of the Soviet partisan movement in Belarus, the normative 1934 grammar was used.

Post Second World War[edit]

After the Second World War, several major factors influenced the development of the Belarusian language. The most important was the implementation of the «rapprochement and unification of Soviet people» policy, which resulted by the 1980s in the Russian language effectively and officially assuming the role of the principal means of communication, with Belarusian relegated to a secondary role. The post-war growth in the number of publications in the Belarusian language in BSSR drastically lagged behind those in Russian. The use of Belarusian as the main language of education was gradually limited to rural schools and humanitarian faculties. The BSSR counterpart of the USSR law «On strengthening of ties between school and real life and on the further development of popular education in the USSR» (1958), adopted in 1959, along with introduction of a mandatory 8-year school education, made it possible for the parents of pupils to opt for non-mandatory studying of the «second language of instruction,» which would be Belarusian in a Russian language school and vice versa. However, for example in the 1955/56 school year, there were 95% of schools with Russian as the primary language of instruction, and 5% with Belarusian as the primary language of instruction.[37]

That was the source of concern for the nationally minded and caused, for example, the series of publications by Barys Sachanka in 1957–61 and the text named «Letter to a Russian Friend» by Alyaksyey Kawka (1979). The BSSR Communist party leader Kirill Mazurov made some tentative moves to strengthen the role of Belarusian language in the second half of the 1950s.[38]

After the beginning of Perestroika and the relaxing of political control in the late 1980s, a new campaign in support of the Belarusian language was mounted in BSSR, expressed in the «Letter of 58» and other publications, producing a certain level of popular support and resulting in the BSSR Supreme Soviet ratifying the «Law on Languages» («Закон аб мовах«; 26 January 1990) requiring the strengthening of the role of Belarusian in state and civic structures.

1959 reform of grammar[edit]