Not to be confused with Czechia.

|

Chechen Republic |

|

|---|---|

|

Republic |

|

| Чеченская Республика / Chechenskaya Respublika | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Chechen | Нохчийн Республика / Noxçiyn Respublika |

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Шатлакхан Илли Şatlaqan İlli «Shatlak’s Song»[3] |

|

|

|

| Coordinates: 43°24′N 45°43′E / 43.400°N 45.717°ECoordinates: 43°24′N 45°43′E / 43.400°N 45.717°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | North Caucasian[1] |

| Economic region | North Caucasus[2] |

| Capital | Grozny |

| Government | |

| • Body | Parliament[4] |

| • Head[4] | Ramzan Kadyrov[5] |

| Area

[6] |

|

| • Total | 17,300 km2 (6,700 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 76th |

| Population

(2021 Census)[7] |

|

| • Total | 1,510,824 |

| • Rank | 31st |

| • Density | 87/km2 (230/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-CE |

| License plates | 95 |

| OKTMO ID | 96000000 |

| Official languages | Russian;[9] Chechen[10] |

Chechnya (Russian: Чечня́, tr. Chechnyá, IPA: [tɕɪtɕˈnʲa]; Chechen: Нохчийчоь, romanized: Noxçiyçö), officially the Chechen Republic,[a] is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, close to the Caspian Sea. The republic forms a part of the North Caucasian Federal District, and shares land borders with the country of Georgia to its south; with the Russian republics of Dagestan, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia-Alania to its east, north, and west; and with Stavropol Krai to its northwest.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Checheno-Ingush ASSR split into two parts: the Republic of Ingushetia and the Chechen Republic. The latter proclaimed the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, which sought independence. Following the First Chechen War of 1994–1996 with Russia, Chechnya gained de facto independence as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, although de jure it remained a part of Russia. Russian federal control was restored in the Second Chechen War of 1999–2009, with Chechen politics being dominated by Akhmad Kadyrov, and later his son Ramzan Kadyrov.[12]

The republic covers an area of 17,300 square kilometres (6,700 square miles), with a population of over 1.5 million residents as of 2021.[7]

It is home to the indigenous Chechens, part of the Nakh peoples, and of primarily Muslim faith. Grozny is the capital and largest city.

History[edit]

Origin of Chechnya’s population[edit]

According to Leonti Mroveli, the 11th-century Georgian chronicler, the word Caucasian is derived from the Nakh ancestor Kavkas.[13]

According to George Anchabadze of Ilia State University:

The Vainakhs are the ancient natives of the Caucasus. It is noteworthy, that according to the genealogical table drawn up by Leonti Mroveli, the legendary forefather of the Vainakhs was «Kavkas», hence the name Kavkasians, one of the ethnicons met in the ancient Georgian written sources, signifying the ancestors of the Chechens and Ingush. As appears from the above, the Vainakhs, at least by name, are presented as the most «Caucasian» people of all the Caucasians (Caucasus – Kavkas – Kavkasians) in the Georgian historical tradition.[14][15]

American linguist Johanna Nichols «has used language to connect the modern people of the Caucasus region to the ancient farmers of the Fertile Crescent» and her research suggests that «farmers of the region were proto-Nakh-Daghestanians.» Nichols stated: «The Nakh–Dagestanian languages are the closest thing we have to a direct continuation of the cultural and linguistic community that gave rise to Western civilisation.»[16]

Prehistory[edit]

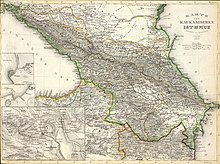

Map of the Caucasian Isthmus

by J. Grassl, 1856

Traces of human settlement dating back to 40,000 BC were found near Lake Kezanoi. Cave paintings, artifacts, and other archaeological evidence indicate continuous habitation for some 8,000 years.[17] People living in these settlements used tools, fire, and clothing made of animal skins.[17]

The Caucasian Epipaleolithic and early Caucasian Neolithic era saw the introduction of agriculture, irrigation, and the domestication of animals in the region.[18] Settlements near Ali-Yurt and Magas, discovered in modern times, revealed tools made out of stone: stone axes, polished stones, stone knives, stones with holes drilled in them, clay dishes etc. Settlements made out of clay bricks were discovered in the plains. In the mountains there were settlements made from stone and surrounded by walls; some of them dated back to 8000 BC.[19] This period also saw the appearance of the wheel (3000 BC), horseback riding, metal works (copper, gold, silver, iron), dishes, armor, daggers, knives and arrow tips in the region. The artifacts were found near Nasare-Cort, Muzhichi, Ja-E-Bortz (alternatively known as Surkha-khi), Abbey-Gove (also known as Nazran or Nasare).[19]

Pre-imperial era[edit]

The German scientist Peter Simon Pallas believed that the Vainakh people (Chechens and Ingush) were the direct descendants from Alania.[20][better source needed] In 1239, the Alania capital of Maghas and the Alan confederacy of the Northern Caucasian highlanders, nations, and tribes was destroyed by Batu Khan (a Mongol leader and a grandson of Genghis Khan).

According to the missionary Pian de Carpine, a part of the Alans had successfully resisted a Mongol siege on a mountain for 12 years:[21]

When they (the Mongols) begin to besiege a fortress, they besiege it for many years, as it happens today with one mountain in the land of the Alans. We believe they have been besieging it for twelve years and

they (the Alans) put up courageous resistance and killed many Tatars, including many noble ones.— Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, report from 1250

This twelve year old siege is not found in any other report, however the Russian historian A.I. Krasnov connected this battle with two Chechen folktales he recorded in 1967 that spoke of an old hunter named Idig who with his companions defended the Dakuoh mountain for 12 years against Tatar-Mongols. He also reported to have found several arrowheads and spears from the 13th century near the very mountain at which the battle took place:[22]

The next year, with the onset of summer, the enemy hordes came again to destroy the highlanders. But even this year they failed to capture the mountain, on which the brave Chechens settled down. The battle lasted twelve years. The main wealth of the Chechens – livestock – was stolen by the enemies. Tired of the long years of hard struggle, the Chechens, believing the assurances of mercy by the enemy, descended from the mountain, but the Mongol-Tatars treacherously killed the majority, and the rest were taken into slavery. This fate was escaped only by Idig and a few of his companions who did not trust the nomads and remained on the mountain. They managed to escape and leave Mount Dakuoh after 12 years of siege.

— Amin Tesaev, The Legend and struggle of the Chechen hero Idig (1238–1250)

In the 14th and 15th centuries, there was frequent warfare between the Chechens, Tamerlan and Tokhtamysh, culminating in the Battle of the Terek River. The Chechen tribes built fortresses, castles, and defensive walls, protecting the mountains from the invaders. Part of the lowland tribes were occupied by Mongols. However, during the mid-14th century a strong Chechen kingdom called Simsir emerged under Khour Ela, a Chechen king that led the Chechen politics and wars. He was in charge of an army of Chechens against the rogue warlord Mamai and defeated him in the Battle of Tatar-tup in 1362. The kingdom of Simsir met its end during the Timurid invasion of the Caucasus, when Khour Ela allied himself with the Golden Horde Khan Tokhtamysh in the Battle of the Terek River. Timur sought to punish the highlanders for their allegiance to Tokhtamysh and as a consequence invaded Simsir in 1395.[23]

The 16th century saw the first Russian involvement in the Caucasus. In 1558, Temryuk of Kabarda sent his emissaries to Moscow requesting help from Ivan the Terrible against the Vainakh tribes. Ivan the Terrible married Temryuk’s daughter Maria Temryukovna. An alliance was formed to gain the ground in the central Caucasus for the expanding Tsardom of Russia against stubborn Vainakh defenders. Chechnya was a nation in the Northern Caucasus that fought against foreign rule continually since the 15th century. Several Chechen leaders such as the 17th century Mehk-Da Aldaman Gheza led the Chechen politics and fought off encroachments of foreign powers. He defended the borders of Chechnya from invasions of Kabardinians and Avars during the Battle of Khachara in 1667.[24]

The Chechens converted over the next few centuries to Sunni Islam, as Islam was associated with resistance to Russian encroachment.[25][26]

Imperial rule[edit]

Peter the Great first sought to increase Russia’s political influence in the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea at the expense of Safavid Persia when he launched the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723. Notable in Chechen history, this particular Russo-Persian War marked the first military encounter between Imperial Russia and the Vainakh. Russian forces succeeded in taking much of the Caucasian territories from Iran for several years.[27]

As the Russians took control of the Caspian corridor and moved into Persian-ruled Dagestan, Peter’s forces ran into mountain tribes. Peter sent a cavalry force to subdue them, but the Chechens routed them.[27] In 1732, after Russia already ceded back most of the Caucasus to Persia, now led by Nader Shah, following the Treaty of Resht, Russian troops clashed again with Chechens in a village called Chechen-aul along the Argun River.[27] The Russians were defeated again and withdrew, but this battle is responsible for the apocryphal story about how the Nokchi came to be known as «Chechens»-the people ostensibly named for the place the battle had taken place. The name Chechen was however already used since as early as 1692.[27]

Under intermittent Persian rule since 1555, in 1783 the eastern Georgians of Kartl-Kakheti led by Erekle II and Russia signed the Treaty of Georgievsk. According to this treaty, Kartl-Kakheti received protection from Russia, and Georgia abjured any dependence on Iran.[28] In order to increase its influence in the Caucasus and to secure communications with Kartli and other Christian regions of the Transcaucasia which it considered useful in its wars against Persia and Turkey, the Russian Empire began conquering the Northern Caucasus mountains. The Russian Empire used Christianity to justify its conquests, allowing Islam to spread widely because it positioned itself as the religion of liberation from tsardom, which viewed Nakh tribes as «bandits».[29] The rebellion was led by Mansur Ushurma, a Chechen Naqshbandi (Sufi) sheikh—with wavering military support from other North Caucasian tribes. Mansur hoped to establish a Transcaucasus Islamic state under sharia law. He was unable to fully achieve this because in the course of the war he was betrayed by the Ottomans, handed over to Russians, and executed in 1794.[30]

Following the forced ceding of the current territories of Dagestan, most of Azerbaijan, and Georgia by Persia to Russia, following the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813 and its resultant Treaty of Gulistan, Russia significantly widened its foothold in the Caucasus at the expense of Persia.[31] Another successful Caucasus war against Persia several years later, starting in 1826 and ending in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay, and a successful war against Ottoman Turkey in 1828 and 1829, enabled Russia to use a much larger portion of its army in subduing the natives of the North Caucasus.

The resistance of the Nakh tribes never ended and was a fertile ground for a new Muslim-Avar commander, Imam Shamil, who fought against the Russians from 1834 to 1859 (see Murid War). In 1859, Shamil was captured by Russians at aul Gunib. Shamil left Baysangur of Benoa,[32] a Chechen with one arm, one eye, and one leg, in charge of command at Gunib. Baysangur broke through the siege and continued to fight Russia for another two years until he was captured and killed by Russians. The Russian tsar hoped that by sparing the life of Shamil, the resistance in the North Caucasus would stop, but it did not. Russia began to use a colonization tactic by destroying Nakh settlements and building Cossack defense lines in the lowlands. The Cossacks suffered defeat after defeat and were constantly attacked by mountaineers, who were robbing them of food and weaponry.

The tsarists’ regime used a different approach at the end of the 1860s. They offered Chechens and Ingush to leave the Caucasus for the Ottoman Empire (see Muhajir (Caucasus)). It is estimated that about 80% of Chechens and Ingush left the Caucasus during the deportation. It weakened the resistance which went from open warfare to insurgent warfare. One of the notable Chechen resistance fighters at the end of the 19th century was a Chechen abrek Zelimkhan Gushmazukaev and his comrade-in-arms Ingush abrek Sulom-Beck Sagopshinski. Together they built up small units which constantly harassed Russian military convoys, government mints, and government post-service, mainly in Ingushetia and Chechnya. Ingush aul Kek was completely burned when the Ingush refused to hand over Zelimkhan. Zelimkhan was killed at the beginning of the 20th century. The war between Nakh tribes and Russia resurfaced during the times of the Russian Revolution, which saw the Nakh struggle against Anton Denikin and later against the Soviet Union.

On 21 December 1917, Ingushetia, Chechnya, and Dagestan declared independence from Russia and formed a single state: «United Mountain Dwellers of the North Caucasus» (also known as the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus) which was recognized by major world powers. The capital of the new state was moved to Temir-Khan-Shura (Dagestan).[33][34] Tapa Tchermoeff, a prominent Chechen statesman, was elected the first prime minister of the state. The second prime minister elected was Vassan-Girey Dzhabagiev, an Ingush statesman, who also was the author of the constitution of the republic in 1917, and in 1920 he was re-elected for the third term. In 1921 the Russians attacked and occupied the country and forcefully absorbed it into the Soviet state. The Caucasian war for independence restarted, and the government went into exile.[35]

Soviet rule[edit]

During Soviet rule, Chechnya and Ingushetia were combined to form the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In the 1930s, Chechnya was flooded with many Ukrainians fleeing from a famine. As a result, many of the Ukrainians settled in Chechen-Ingush ASSR permanently and survived the famine.[36]

Although over 50,000 Chechens and over 12,000 Ingush were fighting against Nazi Germany on the front line (including Heroes of the USSR: Abukhadzhi Idrisov, Khanpasha Nuradilov, Movlid Visaitov), and although Nazi German troops advanced as far as the Ossetian ASSR city of Ordzhonikidze and the Chechen-Ingush ASSR city of Malgobek after capturing half of the Caucasus in less than a month, Chechens and Ingush were falsely accused as Nazi supporters and entire nations were deported during Operation Lentil to the Kazakh SSR (later Kazakhstan) in 1944 near the end of World War II where over 60% of Chechen and Ingush populations perished.[37][38] American historian Norman Naimark writes:

Troops assembled villagers and townspeople, loaded them onto trucks – many deportees remembered that they were Studebakers, fresh from Lend-Lease deliveries over the Iranian border – and delivered them at previously designated railheads. …Those who could not be moved were shot. …[A] few fighters aside, the entire Chechen and Ingush nations, 496,460 people, were deported from their homeland.[39]

The deportation was justified by the materials prepared by NKVD officer Bogdan Kobulov accusing Chechens and Ingush in a mass conspiracy preparing rebellion and providing assistance to the German forces. Many of the materials were later proven to be fabricated.[40] Even distinguished Red Army officers who fought bravely against Germans (e.g. the commander of 255th Separate Chechen-Ingush regiment Movlid Visaitov, the first to contact American forces at Elbe river) were deported.[41] There is a theory that the real reason why Chechens and Ingush were deported was the desire of Russia to attack Turkey, an anti-communist country, as Chechens and Ingush could impede such plans.[29] In 2004, the European Parliament recognized the deportation of Chechens and Ingush as an act of genocide.[42]

The territory of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was divided between Stavropol Krai (where Grozny Okrug was formed), the Dagestan ASSR, the North Ossetian ASSR, and the Georgian SSR.

The Chechens and Ingush were allowed to return to their land after 1956 during de-Stalinisation under Nikita Khrushchev[37] when the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was restored but with both the boundaries and ethnic composition of the territory significantly changed. There were many (predominantly Russian) migrants from other parts of the Soviet Union, who often settled in the abandoned family homes of Chechens and Ingushes. The republic lost its Prigorodny District which transferred to North Ossetian ASSR but gained predominantly Russian Naursky District and Shelkovskoy District that is considered the homeland for Terek Cossacks.

The Russification policies towards Chechens continued after 1956, with Russian language proficiency required in many aspects of life to provide Chechens better opportunities for advancement in the Soviet system.[29]

On 26 November 1990, the Supreme Council of Chechen-Ingush ASSR adopted the «Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Chechen-Ingush Republic». This declaration was part of the reorganisation of the Soviet Union. This new treaty was to be signed 22 August 1991, which would have transformed 15 republic states into more than 80. The 19–21 August 1991 Soviet coup d’état attempt led to the abandonment of this reorganisation.[43]

With the impending dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, an independence movement, the Chechen National Congress, was formed, led by ex-Soviet Air Force general and new Chechen President Dzhokhar Dudayev. It campaigned for the recognition of Chechnya as a separate nation. This movement was opposed by Boris Yeltsin’s Russian Federation, which argued that Chechnya had not been an independent entity within the Soviet Union—as the Baltic, Central Asian, and other Caucasian States had—but was part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and hence did not have a right under the Soviet constitution to secede. It also argued that other republics of Russia, such as Tatarstan, would consider seceding from the Russian Federation if Chechnya were granted that right. Finally, it argued that Chechnya was a major hub in the oil infrastructure of Russia and hence its secession would hurt the country’s economy and energy access.[citation needed]

In the ensuing decade, the territory was locked in an ongoing struggle between various factions, usually fighting unconventionally.

Chechen Wars[edit]

The First Chechen War took place from 1994 to 1996, when Russian forces attempted to regain control over Chechnya, which had declared independence in November 1991. Despite overwhelming numerical superiority in men, weaponry, and air support, the Russian forces were unable to establish effective permanent control over the mountainous area due to numerous successful full-scale battles and insurgency raids. The Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis in 1995 shocked the Russian public.

In April 1996 the first democratically elected president of Chechnya, Dzhokhar Dudayev, was killed by Russian forces using a booby trap bomb and a missile fired from a warplane after he was located by triangulating the position of a satellite phone he was using.[44]

The widespread demoralisation of the Russian forces in the area and a successful offensive to re-take Grozny by Chechen rebel forces led by Aslan Maskhadov prompted Russian President Boris Yeltsin to declare a ceasefire in 1996, and sign a peace treaty a year later that saw a withdrawal of Russian forces.[45]

After the war, parliamentary and presidential elections took place in January 1997 in Chechnya and brought to power new President Aslan Maskhadov, chief of staff and prime minister in the Chechen coalition government, for a five-year term. Maskhadov sought to maintain Chechen sovereignty while pressing the Russian government to help rebuild the republic, whose formal economy and infrastructure were virtually destroyed.[46] Russia continued to send money for the rehabilitation of the republic; it also provided pensions and funds for schools and hospitals. Nearly half a million people (40% of Chechnya’s prewar population) had been internally displaced and lived in refugee camps or overcrowded villages.[47][page needed] There was an economic downturn. Two Russian brigades were permanently stationed in Chechnya.[47]

In lieu of the devastated economic structure, kidnapping emerged as the principal source of income countrywide, procuring over US$200 million during the three-year independence of the chaotic fledgling state,[48] although victims were rarely killed.[49] In 1998, 176 people were kidnapped, 90 of whom were released, according to official accounts. President Maskhadov started a major campaign against hostage-takers, and on 25 October 1998, Shadid Bargishev, Chechnya’s top anti-kidnapping official, was killed in a remote-controlled car bombing. Bargishev’s colleagues then insisted they would not be intimidated by the attack and would go ahead with their offensive. Political violence and religious extremism, blamed on «Wahhabism», was rife. In 1998, Grozny authorities declared a state of emergency. Tensions led to open clashes between the Chechen National Guard and Islamist militants, such as the July 1998 confrontation in Gudermes.

The War of Dagestan began on 7 August 1999, during which the Islamic International Peacekeeping Brigade (IIPB) began an unsuccessful incursion into the neighboring Russian republic of Dagestan in favor of the Shura of Dagestan which sought independence from Russia.[50] In September, a series of apartment bombs that killed around 300 people in several Russian cities, including Moscow, were blamed on the Chechen separatists.[37] Some journalists contested the official explanation, instead blaming the Russian Secret Service for blowing up the buildings to initiate a new military campaign against Chechnya.[51] In response to the bombings, a prolonged air campaign of retaliatory strikes against the Ichkerian regime and a ground offensive that began in October 1999 marked the beginning of the Second Chechen War. Much better organized and planned than in the first Chechen War, the Russian armed forces took control of most regions. The Russian forces used brutal force, killing 60 Chechen civilians during a mop-up operation in Aldy, Chechnya on 5 February 2000. After the re-capture of Grozny in February 2000, the Ichkerian regime fell apart.[52]

Post-war reconstruction and insurgency[edit]

Chechen rebels continued to fight Russian troops and conduct terrorist attacks.[53][page needed] In October 2002, 40–50 Chechen rebels seized a Moscow theater and took about 900 civilians hostage.[37] The crisis ended with 117 hostages and up to 50 rebels dead, mostly due to an unknown aerosol pumped into the building by Russian special forces to incapacitate the people inside.[54][55][56]

In response to the increasing terrorism, Russia tightened its grip on Chechnya and expanded its anti-terrorist operations throughout the region. Russia installed a pro-Russian Chechen regime. In 2003, a referendum was held on a constitution that reintegrated Chechnya within Russia but provided limited autonomy. According to the Chechen government, the referendum passed with 95.5% of the votes and almost 80% turnout.[57] The Economist was skeptical of the results, arguing that «few outside the Kremlin regard the referendum as fair».[58]

In September 2004, separatist rebels occupied a school in the town of Beslan, North Ossetia, demanding recognition of the independence of Chechnya and a Russian withdrawal. 1,100 people (including 777 children) were taken hostage. The attack lasted three days, resulting in the deaths of over 331 people, including 186 children.[37][59][60][61] After the 2004 school siege, Russian president Vladimir Putin announced sweeping security and political reforms, sealing borders in the Caucasus region and revealing plans to give the central government more power. He also vowed to take tougher action against domestic terrorism, including preemptive strikes against Chechen separatists.[37] In 2005 and 2006, separatist leaders Aslan Maskhadov and Shamil Basayev were killed.

Since 2007, Chechnya has been governed by Ramzan Kadyrov. Kadyrov’s rule has been characterized by high-level corruption, a poor human rights record, widespread use of torture, and a growing cult of personality.[62][63] Allegations of anti-gay purges in Chechnya were initially reported on 1 April 2017.

In April 2009, Russia ended its counter-terrorism operation and pulled out the bulk of its army.[64] The insurgency in the North Caucasus continued even after this date. The Caucasus Emirate had fully adopted the tenets of a Salafist jihadist group through its strict adherence to the Sunni Hanbali obedience to the literal interpretation of the Quran and the Sunnah.[65]

In June 2022, the US State Department advised citizens not to travel to Chechnya, due to terrorism, kidnapping, and risk of civil unrest.[66]

Geography[edit]

The mountains in the area Sharoy

Situated in the eastern part of the North Caucasus in Eastern Europe, Chechnya is surrounded on nearly all sides by Russian Federal territory. In the west, it borders North Ossetia and Ingushetia, in the north, Stavropol Krai, in the east, Dagestan, and to the south, Georgia. Its capital is Grozny. Chechnya is well known for being mountainous, but it is in fact split between the more flat areas north of the Terek, and the highlands south of the Terek.

- Area: 17,300 km2 (6680 sq mi)

- Borders:

- Internal:

- Dagestan (NE)

- Ingushetia (W)

- North Ossetia–Alania (W)

- Stavropol Krai (NW)

- Foreign:

- Georgia (Kakheti and Mtskheta-Mtianeti) (S)

- Internal:

Rivers:

- Terek

- Sunzha

- Argun

Climate[edit]

Despite a relatively small territory, Chechnya is characterized by a significant variety of climate conditions. The average temperature in Grozny is 11.2 °C (52.1 °F).[67]

Cities and towns with over 20,000 people[edit]

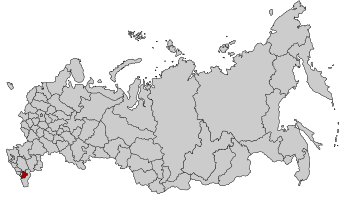

Map of Chechen Republic (Chechnya)

- Grozny (capital)

- Shali

- Urus-Martan

- Gudermes

- Argun

Administrative divisions[edit]

The Chechen Republic is divided into 15 districts and 3 cities of republican significance.

Informal divisions[edit]

There are no true districts of Chechnya, but the different dialects of the Chechen language informally define different districts. The main dialects are:

Grozny, also known as the Dzhokhar dialect, is the dialect of people who live in and in some towns around Grozny.

Naskhish, a dialect spoken to the northeast of Chechnya. The most notable difference in this dialect is the addition of the letters «ȯ», «ј» and «є»

Day, pronounced like the word ‘die’ is spoken in a small section of the south, around and in the town of Day.

There are other dialects which are believed to define districts, but because these areas are so isolated, not much research has been done on these areas.

Demographics[edit]

Chechen World War II veterans during celebrations on the 66th anniversary of victory in the Great Patriotic War

According to the 2021 Census, the population of the republic is 1,510,824,[7] up from 1,268,989 in the 2010 Census.[68]

As of the 2021 Census,[69] Chechens at 1,456,792 make up 96.4% of the republic’s population. Other groups include Russians (18,225, or 1.2%), Kumyks (12,184, or 0.8%) and a host of other small groups, each accounting for less than 0.5% of the total population. The Armenian community, which used to number around 15,000 in Grozny alone, has dwindled to a few families.[70] The Armenian church of Grozny was demolished in 1930. The birth rate was 25.41 in 2004. (25.7 in Achkhoi Martan, 19.8 in Groznyy, 17.5 in Kurchaloi, 28.3 in Urus Martan and 11.1 in Vedeno).

At the end of the Soviet era, ethnic Russians (including Cossacks) comprised about 23% of the population (269,000 in 1989), but now Russians number only about 16,400 people (about 1.2% of the population) and still some emigration is happening.

The languages used in the Republic are Chechen and Russian. Chechen belongs to the Vaynakh or North-central Caucasian language family, which also includes Ingush and Batsb. Some scholars place it in a wider North Caucasian languages.

Life expectancy[edit]

Despite its difficult past, Chechnya has a high life expectancy, one of the highest in Russia. But the pattern of life expectancy is unusual, and in according to numerous statistics, Chechnya stands out from the overall picture. In 2020 Chechnya had the deepest fall in life expectancy, but in 2021 it had the biggest rise. Chechnya has the highest excess of life expectancy in rural areas over cities.[71][72]

| 2019 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| Average: | 75.9 years | 73.0 years |

| Male: | 73.6 years | 70.5 years |

| Female: | 78.0 years | 75.3 years |

-

Life expectancy at birth in Chechnya

-

Life expectancy with calculated differences

-

Life expectancy in Chechnya in comparison with neighboring regions of the country

-

Interactive chart of comparison of male and female life expectancy for 2021. Open the original svg-file in a separate window and hover over a bubble to highlight it.

Settlements[edit]

|

Largest cities or towns in Chechnya 2010 Russian Census |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Administrative Division | Pop. | ||

Grozny  Urus-Martan |

1 | Grozny | City of republic significance of Grozny | 271,573 |  Shali  Gudermes |

| 2 | Urus-Martan | Urus-Martanovsky District | 49,070 | ||

| 3 | Shali | Shalinsky District | 47,708 | ||

| 4 | Gudermes | Gudermessky District | 45,631 | ||

| 5 | Argun | Town of republic significance of Argun | 29,525 | ||

| 6 | Kurchaloy | Kurchaloyevsky District | 22,723 | ||

| 7 | Achkhoy-Martan | Achkhoy-Martanovsky District | 20,172 | ||

| 8 | Tsotsi-Yurt | Kurchaloyevsky District | 18,306 | ||

| 9 | Bachi-Yurt | Kurchaloyevsky District | 16,485 | ||

| 10 | Goyty | Urus-Martanovsky District | 16,177 |

Vital statistics[edit]

Ethnolinguistic groups in the Caucasus region

- Source: Fedstat (Суммарный коэффициент рождаемости) Archived 2 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine

| Average population (x 1000) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Total fertility rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 1,117 | 27,774 | 7,194 | 20 580 | 24.9 | 6.4 | 18.4 | |

| 2004 | 1,133 | 28,496 | 6,347 | 22,149 | 25.2 | 5.6 | 19.5 | |

| 2005 | 1,150 | 28,652 | 5,857 | 22,795 | 24.9 | 5.1 | 19.8 | |

| 2006 | 1,167 | 27,989 | 5,889 | 22,100 | 24.0 | 5.0 | 18.9 | |

| 2007 | 1,187 | 32,449 | 5,630 | 26,819 | 27.3 | 4.7 | 22.6 | 3.18 |

| 2008 | 1,210 | 35,897 | 5,447 | 30,450 | 29.7 | 4.5 | 25.2 | 3.44 |

| 2009 | 1,235 | 36,523 | 6,620 | 29,903 | 29.6 | 5.4 | 24.2 | 3.41 |

| 2010 | 1,260 | 37,753 | 7,042 | 30,711 | 30.0 | 5.6 | 24.4 | 3.45 |

| 2011 | 1,289 | 37,335 | 6,810 | 30,525 | 28.9 | 5.3 | 23.6 | 3.36 |

| 2012 | 1,314 | 34,385 | 7,192 | 27,193 | 26.2 | 5.5 | 20.7 | 3.08 |

| 2013 | 1,336 | 32,963 | 6,581 | 26,382 | 24.7 | 4.9 | 19.8 | 2.93 |

| 2014 | 1,358 | 32,949 | 6,864 | 26,085 | 24.3 | 5.1 | 19.2 | 2.91 |

| 2015 | 1,383 | 32,057 | 6,728 | 25,329 | 23.2 | 4.9 | 18.3 | 2.80 |

| 2016 | 1,404 | 29,893 | 6,630 | 23,263 | 21.3 | 4.7 | 16.6 | 2.62 |

| 2017 | 1,425 | 29,890 | 6,586 | 23,304 | 21.0 | 4.6 | 16.4 | 2.73 |

| 2018 | 1,444 | 29,883 | 6,430 | 23,453 | 20.6 | 4.4 | 16.2 | 2.60 |

| 2019 | 1,467 | 28,145 | 6,357 | 21,788 | 19.2 | 4.3 | 14.9 | 2.58 |

| 2020 | 1,488 | 30,111 | 9,188 | 20,923 | 20.2 | 6.2 | 14.0 | 2.57 |

| 2021 | 1,509 | 30,345 | 8,904 | 21,441 | 20.1 | 5.9 | 14.2 | 2.60 |

Ethnic groups[edit]

(in the territory of modern Chechnya)[73][unreliable source]

| Ethnic group |

1926 Census | 1939 Census2 | 1959 Census2 | 1970 Census | 1979 Census | 1989 Census | 2002 Census | 2010 Census | 2021 Census1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Chechens | 293,298 | 67.3% | 360,889 | 58.0% | 238,331 | 39.7% | 499,962 | 54.7% | 602,223 | 60.1% | 715,306 | 66.0% | 1,031,647 | 93.5% | 1,206,551 | 95.3% | 1,456,792 | 96.4% |

| Russians | 103,271 | 23.5% | 213,354 | 34.3% | 296,794 | 49.4% | 327,701 | 35.8% | 307,079 | 30.6% | 269,130 | 24.8% | 40,645 | 3.7% | 24,382 | 1.9% | 18,225 | 1.2% |

| Kumyks | 2,217 | 0.5% | 3,575 | 0.6% | 6,865 | 0.8% | 7,808 | 0.8% | 9,591 | 0.9% | 8,883 | 0.8% | 12,221 | 1.0% | 12,184 | 0.8% | ||

| Avars | 830 | 0.2% | 2,906 | 0.5% | 4,196 | 0.5% | 4,793 | 0.5% | 6,035 | 0.6% | 4,133 | 0.4% | 4,864 | 0.4% | 4,079 | 0.3% | ||

| Nogais | 162 | 0.0% | 1,302 | 0.2% | 5,503 | 0.6% | 6,079 | 0.6% | 6,885 | 0.6% | 3,572 | 0.3% | 3,444 | 0.3% | 2,819 | 0.2% | ||

| Ingushes | 798 | 0.2% | 4,338 | 0.7% | 3,639 | 0.6% | 14,543 | 1.6% | 20,855 | 2.1% | 25,136 | 2.3% | 2,914 | 0.3% | 1,296 | 0.1% | 1,100 | 0.1% |

| Ukrainians | 11,474 | 2.6% | 8,614 | 1.4% | 11,947 | 2.0% | 11,608 | 1.3% | 11,334 | 1.1% | 11,884 | 1.1% | 829 | 0.1% | 13,716 | 1.1% | 15,625 | 1.0% |

| Armenians | 5,978 | 1.4% | 8,396 | 1.3% | 12,136 | 2.0% | 13,948 | 1.5% | 14,438 | 1.4% | 14,666 | 1.4% | 424 | 0.0% | ||||

| Others | 18,840 | 4.13% | 18,646 | 3.0% | 37,550 | 6.3% | 30,057 | 3.3% | 27,621 | 2.8% | 25,800 | 2.4% | 10,639 | 1.0% | ||||

| 1 2,515 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[74]|2 Note that practically all Chechen and Ingush people were deported to Central Asia or killed in 1944. They were, however, allowed to return to the Northern Caucasus in 1957 by Nikita Khrushchev. See Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush |

Religion[edit]

Islam[edit]

Islam is the predominant religion in Chechnya, practiced by 95% of those polled in Grozny in 2010.[75] Most of the population follows either the Shafi’i or the Hanafi schools of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence).[76] The Shafi’i school of jurisprudence has a long tradition among the Chechens, and thus it remains the most practiced.[77][78] Many Chechens are also Sufis, of either the Qadiri or Naqshbandi orders.

Following the end of the Soviet Union, there has been an Islamic revival in Chechnya, and in 2011 it was estimated that there were 465 mosques, including the Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque in Grozny accommodating 10,000 worshippers, as well 31 madrasas, including an Islamic university named Kunta-haji and a Center of Islamic Medicine in Grozny which is the largest such institution in Europe.[79]

Christianity[edit]

From the 11th to 13th centuries (i.e. before Mongol invasions of Durdzuketia), there was a mission of Georgian Orthodox missionaries to the Nakh peoples. Their success was limited, though a couple of highland teips did convert (conversion was largely by teip). However, during the Mongol invasions, these Christianized teips gradually reverted to paganism, perhaps due to the loss of trans-Caucasian contacts as the Georgians fought the Mongols and briefly fell under their dominion.

The once-strong Russian minority in Chechnya, mostly Terek Cossacks and estimated as numbering approximately 25,000 in 2012, are predominantly Russian Orthodox, although currently only one church exists in Grozny. In August 2011, Archbishop Zosima of Vladikavkaz and Makhachkala performed the first mass baptism ceremony in the history of the Chechen Republic in the Terek River of Naursky District in which 35 citizens of Naursky and Shelkovsky districts were converted to Orthodoxy.[80] As of 2020, there are eight Orthodox churches in Chechnya, the largest is the temple of the Archangel Michael in Grozny.

Politics[edit]

Since 1990, the Chechen Republic has had many legal, military, and civil conflicts involving separatist movements and pro-Russian authorities. Today, Chechnya is a relatively stable federal republic, although there is still some separatist movement activity. Its regional constitution entered into effect on 2 April 2003, after an all-Chechen referendum was held on 23 March 2003. Some Chechens were controlled by regional teips, or clans, despite the existence of pro- and anti-Russian political structures.

Regional government[edit]

Chechnya and Caucasus map

The former separatist religious leader (mufti) Akhmad Kadyrov, looked upon as a traitor by many separatists, was elected president with 83% of the vote in an internationally monitored election on 5 October 2003. Incidents of ballot stuffing and voter intimidation by Russian soldiers and the exclusion of separatist parties from the polls were subsequently reported by Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) monitors. On 9 May 2004, Kadyrov was assassinated in Grozny football stadium by a landmine explosion that was planted beneath a VIP stage and detonated during a parade, and Sergey Abramov was appointed acting prime minister after the incident. However, since 2005 Ramzan Kadyrov (son of Akhmad Kadyrov) has been the caretaker prime minister, and in 2007 was appointed as the new president. Many allege he is the wealthiest and most powerful man in the republic, with control over a large private militia (the Kadyrovites). The militia, which began as his father’s security force, has been accused of killings and kidnappings by human rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch.

Separatist government[edit]

Ichkeria was a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation between 1991 and 2010.[81] Former president of Georgia Zviad Gamsakhurdia deposed in a military coup of 1991 and a participant of the Georgian Civil War, recognized the independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria in 1993.[82] Diplomatic relations with Ichkeria were also established by the partially recognised Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan under the Taliban government on 16 January 2000. This recognition ceased with the fall of the Taliban in 2001.[83] However, despite Taliban recognition, there were no friendly relations between the Taliban and Ichkeria—Maskhadov rejected their recognition, stating that the Taliban were illegitimate.[84] Ichkeria also received vocal support from the Baltic countries, a group of Ukrainian nationalists, and Poland; Estonia once voted to recognize, but the act never was followed through due to pressure applied by both Russia and the EU.[84][85][86]

The president of this government was Aslan Maskhadov, the foreign minister was Ilyas Akhmadov, who was the spokesman for Maskhadov. Aslan Maskhadov had been elected in an internationally monitored election in 1997 for four years, which took place after signing a peace agreement with Russia. In 2001 he issued a decree prolonging his office for one additional year; he was unable to participate in the 2003 presidential election since separatist parties were barred by the Russian government, and Maskhadov faced accusations of terrorist offenses in Russia. Maskhadov left Grozny and moved to the separatist-controlled areas of the south at the onset of the Second Chechen War. Maskhadov was unable to influence a number of warlords who retain effective control over Chechen territory, and his power was diminished as a result. Russian forces killed Maskhadov on 8 March 2005, and the assassination of Maskhadov was widely criticized since it left no legitimate Chechen separatist leader with whom to conduct peace talks. Akhmed Zakayev, deputy prime minister and a foreign minister under Maskhadov, was appointed shortly after the 1997 election and is currently living under asylum in England. He and others chose Abdul Khalim Saidullayev, a relatively unknown Islamic judge who was previously the host of an Islamic program on Chechen television, to replace Maskhadov following his death. On 17 June 2006, it was reported that Russian special forces killed Abdul Khalim Saidullayev in a raid in the Chechen town of Argun.

The successor of Saidullayev became Doku Umarov. On 31 October 2007, Umarov abolished the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and its presidency and in its place proclaimed the Caucasus Emirate with himself as its Emir.[87] This change of status has been rejected by many Chechen politicians and military leaders who continue to support the existence of the republic.

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian parliament voted to recognize the «Chechen republic of Ichkeria as territory temporarily occupied by the Russian Federation».[88]

Human rights[edit]

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Center reports that after hundreds of thousands of ethnic Russians and Chechens fled their homes following inter-ethnic and separatist conflicts in Chechnya in 1994 and 1999, more than 150,000 people still remain displaced in Russia today.[89]

Human rights groups criticized the conduct of the 2005 parliamentary elections as unfairly influenced by the central Russian government and military.[90]

In 2006 Human Rights Watch reported that pro-Russian Chechen forces under the command of Ramzan Kadyrov, as well as federal police personnel, used torture to get information about separatist forces. «If you are detained in Chechnya, you face a real and immediate risk of torture. And there is little chance that your torturer will be held accountable», said Holly Cartner, Director of the Europe and Central Asia division of the Human Rights Watch.[91]

In 2009, the US government financed American organization Freedom House included Chechnya in the «Worst of the Worst» list of most repressive societies in the world, together with Burma, North Korea, Tibet, and others.[92]

On 1 February 2009, The New York Times released extensive evidence to support allegations of consistent torture and executions under the Kadyrov government. The accusations were sparked by the assassination in Austria of a former Chechen rebel who had gained access to Kadyrov’s inner circle, 27-year-old Umar Israilov.[93]

On 1 July 2009, Amnesty International released a detailed report covering the human rights violations committed by the Russian Federation against Chechen citizens. Among the most prominent features was that those abused had no method of redress against assaults, ranging from kidnapping to torture, while those responsible were never held accountable. This led to the conclusion that Chechnya was being ruled without law, being run into further devastating destabilization.[94]

On 10 March 2011, Human Rights Watch reported that since Chechenization, the government has pushed for enforced Islamic dress code.[95] The president Ramzan Kadyrov is quoted as saying «I have the right to criticize my wife. She doesn’t [have the right to criticize me]. With us [in Chechen society], a wife is a housewife. A woman should know her place. A woman should give her love to us [men]… She would be [man’s] property. And the man is the owner. Here, if a woman does not behave properly, her husband, father, and brother are responsible. According to our tradition, if a woman fools around, her family members kill her… That’s how it happens, a brother kills his sister or a husband kills his wife… As a president, I cannot allow for them to kill. So, let women not wear shorts…».[96] He has also openly defended honor killings on several occasions.[97]

On 9 July 2017, Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta reported that a number of people were subject to an extrajudicial execution on the night of 26 January 2017. It published 27 names of the people known to be dead, but stressed that the list is «not all [of those killed]»; the newspaper asserted that 50 people may have been killed in the execution.[98] Some of the dead were gay, but not all; the deaths appeared to have been triggered by the death of a policeman,[98] and according to the author of the report, Elena Milashina, were executed for alleged terrorism.[99]

In December 2021, up to 50 family members of critics of the Kadyrov government were abducted in a wave of mass kidnappings beginning on 22 December.[100]

LGBT rights[edit]

On 1 September 1997, Criminal Code reportedly being implemented in the Chechen Republic-Ichkeriya, Article 148 punishes «anal sexual intercourse between a man and a woman or a man and a man». For first- and second-time offenders, the punishment is caning. A third conviction leads to the death penalty, which can be carried out in a number of ways including stoning or beheading.[101]

In 2017, it was reported by Novaya Gazeta and human rights groups that Chechen authorities had set up concentration camps, one of which is in Argun, where gay men are interrogated and subjected to physical violence.[102][103][104][105] On 27 June 2018, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe noted «cases of abduction, arbitrary detention and torture … with the direct involvement of Chechen law enforcement officials and on the orders of top-level Chechen authorities»[106] and expressed dismay «at the statements of Chechen and Russian public officials denying the existence of LGBTI people in the Chechen Republic».[106] Kadyrov’s spokesman Alvi Karimov told Interfax that gay people «simply do not exist in the republic» and made an approving reference to honor killings by family members «if there were such people in Chechnya».[107] In a 2021 Council of Europe report into anti-LGBTI hate crimes, rapporteur Foura ben Chikha described the «state-sponsored attacks carried out against LGBTI people in Chechnya in 2017» as «the single most egregious example of violence against LGBTI people in Europe that has occurred in decades».[108]

On 11 January 2019, it was reported that another ‘gay purge’ had begun in the country in December 2018, with several gay men and women being detained.[109][110][111][112] The Russian LGBT Network believes that around 40 people were detained and two killed.[113][114]

Economy[edit]

Grozny in 2013, with the «Heart of Chechnya» Mosque on the right

During the war, the Chechen economy fell apart.[115] In 1994, the separatists planned to introduce a new currency, but the change did not occur due to the re-taking of Chechnya by Russian troops in the Second Chechen War.[115]

The economic situation in Chechnya has improved considerably since 2000. According to the New York Times, major efforts to rebuild Grozny have been made, and improvements in the political situation have led some officials to consider setting up a tourism industry, though there are claims that construction workers are being irregularly paid and that poor people have been displaced.[116]

Chechnya’s unemployment was 67% in 2006 and fell to 21.5% in 2014.[117]

Total revenue of the budget of Chechnya for 2017 was 59.2 billion rubles. Of these, 48.5 billion rubles were grants from the federal budget of the Russian Federation.

In late 1970s, Chechnya produced up to 20 million tons of oil annually, production declined sharply to approximately 3 million tons in the late 1980s, and to below 2 million tons before 1994, first (1994–1996) second Russian invasion of Chechnya (1999) inflicted material damage on the oil-sector infrastructure, oil production decreased to 750,000 tons in 2001 only to increase to 2 million tons in 2006, by 2012 production was 1 million tons.[118]

References[edit]

- ^ Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №849 от 13 мая 2000 г. «О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе». Вступил в силу 13 мая 2000 г. Опубликован: «Собрание законодательства РФ», No. 20, ст. 2112, 15 мая 2000 г. (President of the Russian Federation. Decree #849 of May 13, 2000 On the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in a Federal District. Effective as of May 13, 2000.).

- ^ Госстандарт Российской Федерации. №ОК 024-95 27 декабря 1995 г. «Общероссийский классификатор экономических регионов. 2. Экономические районы», в ред. Изменения №5/2001 ОКЭР. (Gosstandart of the Russian Federation. #OK 024-95 December 27, 1995 Russian Classification of Economic Regions. 2. Economic Regions, as amended by the Amendment #5/2001 OKER. ).

- ^ Decree #164

- ^ a b Constitution, Article 5.1

- ^ Official website of the Chechen Republic. Ramzan Akhmatovich Kadyrov Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (21 May 2004). «Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)». Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ a b c «Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации». Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ «Об исчислении времени». Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Official throughout the Russian Federation according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- ^ Constitution of the Chechen Republic, Article 10.1

- ^ Law #4071-1

- ^ «Ramzan Kadyrov: Putin’s key Chechen ally». BBC. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ The work of Leonti Mroveli: «The history of the Georgian Kings» dealing with the history of Georgia and the Caucasus since ancient times to the 5th century AD, is included in medieval code of Georgian annals «Kartlis Tskhovreba».

- ^ «Caucasian Knot | An Essay on the History of the Vainakh People. On the origin of the Vainakhs». Eng.kavkaz-uzel.ru. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ «Microsoft Word – 4C04B861-0826-0853BD.doc» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Wuethrich, Bernice (19 May 2000). «Peering into the Past, With Words». Science. 288 (5469): 1158. doi:10.1126/science.288.5469.1158. S2CID 82205296.;Bernice Wuethrich, «Science» 2000: Vol. 288 no. 5469 p. 1158

- ^ a b Jaimoukha, Amjad M. (1 March 2005). The Chechens: a handbook (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ Bernice Wuethrich (19 May 2000). «Peering into the Past, With Words». Science. 288 (5469): 1158. doi:10.1126/science.288.5469.1158. S2CID 82205296.

- ^ a b N.D. Kodzoev. History of Ingush nation.

- ^ «Ингушетия.Ru • Авторские Материалы». Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Tesaev, Amin (2020). «К личности и борьбе чеченского героя идига (1238–1250 гг.)».

- ^ Krasnov, A.I. «Копье Тебулос-Мта». Вокруг света. 9: 29.

- ^ Tesaev, Amin (2018). «Симсим». РЕФЛЕКСИЯ. 2: 61–67.

- ^ «Предводитель Гази Алдамов, или Алдаман ГIеза (Амин Тесаев) / Проза.ру». proza.ru.

- ^ Tsaroïeva, Mariel (2005). Anciennes croyances des Ingouches et des Tchétchènes: peuples du Caucase du Nord (in French). Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 978-2-7068-1792-2.

- ^ Ilyasov, Lecha; Ziya Bazhayev Charity Foundation (2009). The Diversity of the Chechen Culture: From Historical Roots to the Present (PDF). UNESCO Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. ISBN 978-5-904549-02-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d Schaefer, Robert W. (2010). The Insurgency in Chechnya and the North Caucasus: From Gazavat to Jihad. ISBN 9780313386343. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (20 December 2011). Iran at War: 1500–1988. ISBN 9781780962214. Retrieved 25 December 2014.[dead link]

- ^ a b c «The Ingush People». Linguistics.berkeley.edu. 28 November 1992. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ John Frederick Baddeley, The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus, London, Curzon Press, 1999, p. 49.

- ^ Cohen, Ariel (1998). Russian Imperialism: Development and Crisis. ISBN 9780275964818. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ «человек из камня БАЙСАНГУР БЕНОЕВСКИЙ». 10 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Общественное движение ЧЕЧЕНСКИЙ КОМИТЕТ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО СПАСЕНИЯ». Savechechnya.com. 24 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ «Вассан-Гирей Джабагиев». Vainah.info. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Umarova, Amina. «Chechnya’s Forgotten Children of the Holodomor». Rferl.org. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Lieven, Dominic. Russia: Chechnya. Microsoft Encarta 2008. Microsoft Corporation.

- ^ «Remembering Stalin’s deportations». BBC News. 23 February 2004. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 2001, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev Time of darkness, Moscow, 2003, ISBN 5-85646-097-9, pages 205–206 (Russian: Яковлев А. Сумерки. Москва: Материк 2003 г.)

- ^ «DEFENSE OF THE MOTHERLAND IS EVERY MUSLIM’S DUTY». RIA Novosti. 5 May 2005.

- ^ «Chechnya: European Parliament recognizes the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944». Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

- ^ James Hughes. «The Peace Process in Chechnya», contained in Richard Sakwa’s Chechnya: From Past to Future. Page 271.

- ^ «‘Dual attack’ killed president». BBC. 21 April 1999. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ «F&P RFE/RL Archive». friends-partners.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ «Chechnya, reference article by Freedom House publications». Archived from the original on 14 July 2009.

- ^ a b Alex Goldfarb and Marina Litvinenko. «Death of a Dissident: The Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and the Return of the KGB.» Free Press, New York, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4165-5165-2.

- ^ Tishkov, Valery. Chechnya: Life in a War-Torn Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, p. 114.

- ^ «Four Western hostages beheaded in Chechnya». CNN. Archived from the original on 3 December 2002.

- ^ Moscow again plans wider war in Dagestan CNN Retrieved on 23 April 2013

- ^ Context of ‘September 13, 1999: Second Moscow Apartment Bombing Kills 118; Chechen Rebels Blamed’ Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 23 April 2013

- ^ «Gay Chechens flee threats, beatings and exorcism». BBC News. 5 April 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Andrew Meier (2005) Chechnya: To the Heart of a Conflict. New York: W.W. Norton

- ^ «Gas ‘killed Moscow hostages’«. BBC News. 27 October 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ «Moscow court begins siege claims», BBC News, 24 December 2002

- ^ «Moscow hostage relatives await news». BBC News. 27 October 2002. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ Aris, Ben (24 March 2003). «Boycott call in Chechen poll ignored». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ The Economist (25 March 2003). «Putin’s proposition». The Economist. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ «August 31, 2006: Beslan – Two Years On». Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009. Retrieved on 24 April 2013

- ^ Putin meets angry Beslan mothers BBC Retrieved on 23 April 2013

- ^ The children of Beslan five years on BBC Retrieved on 23 April 2013

- ^ «Ramzan Kadyrov: The warrior king of Chechnya». The Independent. 4 January 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ «Kadyrov’s Power and Cult of Personality Grows». The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ «Russia ‘ends Chechnya operation’«. BBC News. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ «Salafist-Takfiri Jihadism: the Ideology of the Caucasus Emirate». ict.org.il. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ «Russia Travel Advisory». travel.state.gov.

- ^ Climate of Chechnya. Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ «Национальный состав населения». Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Ishkhanyan, Vahan. «The case for Chechnya». Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ «Демографический ежегодник России» [The Demographic Yearbook of Russia] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat). Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ «Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни при рождении» [Life expectancy at birth]. Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System of Russia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ «НАСЕЛЕНИЕ ЧЕЧНИ». Ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ «Перепись-2010: русских становится больше». Perepis-2010.ru. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ В Чечне наблюдается высокая степень религиозной нетерпимости [High degree of religious intolerance observed in Chechnya]. Caucasus Times. Caucasus Times poll (in Russian). 16 May 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ McDermott, Roger. «Shafi’i and Hanafi schools of jurisprudence in Chechnya». Jamestown.org. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam (9 November 2009). Religion and Politics in Russia: A Reader. ISBN 9780765629319.

- ^ Mairbek Vatchagaev (8 September 2006). «The Kremlin’s War on Islamic Education in the North Caucasus». Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Chechnya Weekly, Volume 7, Issue 34 (8 September 2006)

- ^ Nazgul A. Mingisheva and Yesbossyn M. Smagulov, «Chechnya» in Mark Juergensmeyer and Wade Clark Roof, Encyclopedia of Global Religion, Volume 1, SAGE, 2012, p. 193

- ^ Interfax Information Services Group. «Chechnya saw the first mass baptism in its today’s history». Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ «UNPO: Chechen Republic of Ichkeria». unpo.org. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ in 1993, ex –President of Georgia Zviad Gamsakhurdia recognized Chechnya’s independence.., Archived 21 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Are Chechens in Afghanistan? Archived 7 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine – By Nabi Abdullaev, 14 December 2001, Moscow Times

- ^ a b Kullberg, Anssi. «The Background of Chechen Independence Movement III: The Secular Movement». The Eurasian politician. 1 October 2003

- ^ Kari Takamaa and Martti Koskenneimi. The Finnish Yearbook of International Law. p147

- ^ Kuzio, Taras. «The Chechen crisis and the ‘near abroad‘«. Central Asian Survey, Volume 14, Issue 4 1995, pages 553–572

- ^ «What is Hidden Behind the Idea of the Caucasian Emirate?» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Reuters (18 October 2022). «Ukraine lawmakers brand Chechnya ‘Russian-occupied’ in dig at Kremlin». Reuters. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Government efforts help only some IDPs rebuild their lives, IDMC, 13 August 2007 Archived 21 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chechnya Holds Parliamentary Vote, Morning Edition, NPR, 28 November 2005.

- ^ Human Rights Watch:Chechnya: Research Shows Widespread and Systematic Use of Torture

- ^ Worst of the Worst: The World’s Most Repressive Societies Archived 10 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Freedom House, March 2009

- ^ Chivers, C. J. (31 January 2009). «Slain Exile Detailed Cruelty of the Ruler of Chechnya». The New York Times.

- ^ Amnesty International:Russian Federation Rule Without Law: Human Rights violations in the North Caucasus Archived 3 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 1 July 2009.

- ^ Human Rights Watch:»You Dress According to Their Rules» Enforcement of an Islamic Dress Code for Women in Chechnya Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 10 March 2011

- ^ правды», Александр ГАМОВ | Сайт «Комсомольской (24 September 2008). «Рамзан КАДЫРОВ: «Россия – это матушка родная»«. KP.RU – сайт «Комсомольской правды» (in Russian). Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Chechen President Kadyrov Defends Honor Killings Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine The St. Petersburg Times 3 March 2009

- ^ a b Milashina, Elena (9 July 2017). «Это была казнь. В ночь на 26 января в Грозном расстреляли десятки людей». Novaya Gazeta. Moscow. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ «Who Is Afraid of Navalny, Killings in Chechnya, Trump-Putin Meeting». Institute of Modern Russia. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ «Dozens of relatives of government critics reportedly kidnapped in Chechnya». OC Media. 28 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ «Amnesty International working against laws punishing sexual relations between men». Amnesty International. 21 August 1997.

- ^ «Chechnya police arrest 100 suspected gay men, three killed: report». The Globe and Mail. Associated Press. 3 April 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ Duffy, Nick (10 April 2017). «Chechnya has opened concentration camps for gay men». PinkNews. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ Armstrong, Kathy (10 April 2017). «Over 100 people allegedly sent to ‘concentration camps’ for gay men in Chechnya». Irish Independent. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ Gordienko, Irina; Elena Milashina (4 April 2017). Расправы над чеченскими геями [Massacres of Chechen gays (18+)]. Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ a b «Persecution of LGBTI people in the Chechen Republic (Russian Federation), Resolution 2230 (2018)». Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 27 June 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (13 April 2017). «Chechens tell of prison beatings and electric shocks in anti-gay purge: ‘They called us animals’«. The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ ben Chikha, Foura (21 September 2021). «Combating rising hate against LGBTI people in Europe» (PDF). Council of Europe Committee on Equality and Non-Discrimination. pp. 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ Vasilyeva, Nataliya (11 January 2019). «Reports: several gay men and women detained in Chechnya». Associated Press. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Damshenas, Sam (11 January 2019). «Chechnya has reportedly launched a new ‘gay purge’«. Gay Times. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Carroll, Oliver (11 January 2019). «Chechnya launches new gay ‘purge’, reports say». The Independent. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ «Новой газете» стало известно о новых преследованиях геев в Чечне [Novaya Gazeta learned of new persecution of gays in Chechnya]. Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). 11 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ «New wave of persecution against LGBT people in Chechnya: around 40 people detained, at least two killed». Российская ЛГБТ-сеть (in Russian). 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Ingber, Sasha (14 January 2019). «Activists Say 40 Detained And 2 Dead in Gay Purge in Chechnya». NPR. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ a b Russell, John (2007). Gammer, Moshe; Lokshina, Tanya; Thomas, Ray; Mayer, Mary; Dunlop, John B. (eds.). «Chechnya: Russia’s ‘War on Terror’ or ‘War of Terror’?». Europe-Asia Studies. 59 (1): 163–168. doi:10.1080/09668130601072761. JSTOR 20451332. S2CID 153481090.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (30 April 2008). «Chechnya’s Capital Rises From the Ashes, Atop Hidden Horrors». The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ «Chechnya, Republic of Unemployment rate, 1990-2014 — knoema.com». Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ «Does Chechnya Stand To Lose Out From Russian-Azerbaijani Oil Agreement?». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Russian: Чече́нская Респу́блика, romanized: Chechenskaya Respublika; Chechen: Нохчийн Республика, romanized: Noxçiyn Respublika

Sources[edit]

- Президент Чеченской Республики. Указ №164 от 15 июля 2004 г. «О государственном гимне Чеченской Республики». Вступил в силу после одобрения Государственным Советом Чеченской Республики и официального опубликования. Опубликован: БД «Консультант-Плюс». (President of the Chechen Republic. Decree #164 of 15 July 2004 On the State Anthem of the Chechen Republic. Effective as of after the ratification by the State Council of the Chechen Republic and subsequent official publication.).

- Референдум. 23 марта 2003 г. «Конституция Чеченской Республики», в ред. Конституционного закона №1-РКЗ от 30 сентября 2014 г. «О внесении изменений в Конституцию Чеченской Республики». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования по результатам голосования на референдуме Чеченской Республики. (Referendum. March 23, 2003 Constitution of the Chechen Republic, as amended by the Constitutional Law #1-RKZ of September 30, 2014 On Amending the Constitution of the Chechen Republic. Effective as of the day of the official publication in accordance with the results of the referendum of the Chechen Republic.).

- President of the Russian Federation. Law #4071-1 of 10 December 1992 On Amending Article 71 of the Constitution (Basic Law) of the Russian Federation–Russia. Effective as of 10 January 1993..

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, Scott. The Man Who Tried to Save the World. ISBN 0-385-48666-9

- Babchenko, Arkady. One Soldier’s War in Chechnya. Portobello, London ISBN 978-1-84627-039-0

- Baiev, Khassan. The Oath: A Surgeon Under Fire. ISBN 0-8027-1404-8

- Bennigsen-Broxup, Marie. The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance Towards the Muslim World. ISBN 1-85065-069-1

- Bird, Chris. To Catch a Tartar: Notes from the Caucasus. ISBN 0-7195-6506-5

- Bornstein, Yvonne and Ribowsky, Mark. «Eleven Days of Hell: My True Story of Kidnapping, Terror, Torture And Historic FBI & KGB Rescue» AuthorHouse, 2004. ISBN 1-4184-9302-3.

- Conrad, Roy. Roy Conrad. Grozny. A few days…

- Dunlop, John B. Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict ISBN 0-521-63619-1

- Evangelista, Mathew. The Chechen Wars: Will Russia Go the Way of the Soviet Union?. ISBN 0-8157-2499-3.

- Gall, Charlotta & de Waal, Thomas. Chechnya: A Small Victorious War. ISBN 0-330-35075-7

- Gall, Carlotta, and de Waal, Thomas Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus ISBN 0-8147-3132-5

- Goltz, Thomas. Chechnya Diary : A War Correspondent’s Story of Surviving the War in Chechnya. M E Sharpe (2003). ISBN 0-312-268-74-2

- Hasanov, Zaur. The Man of the Mountains. ISBN 099304445X (facts based novel on growing influence of the radical Islam during 1st and 2nd Chechnya wars)

- Khan, Ali. The Chechen Terror: The Play within the Play

- Khlebnikov, Paul. Razgovor s varvarom (Interview with a barbarian). ISBN 5-89935-057-1.

- Lieven, Anatol. Chechnya : Tombstone of Russian Power ISBN 0-300-07881-1

- Mironov, Vyacheslav. Ya byl na etoy voyne. (I was in this war) Biblion – Russkaya Kniga, 2001. Partial translation available online[dead link].

- Mironov, Vyacheslav. Vyacheslav Mironov. Assault on Grozny Downtown

- Mironov, Vyacheslav. Vyacheslav Mironov. I was in that war.

- Oliker, Olga Russia’s Chechen Wars 1994–2000: Lessons from Urban Combat. ISBN 0-8330-2998-3. (A strategic and tactical analysis of the Chechen Wars.)

- Pelton, Robert Young. Hunter Hammer and Heaven, Journeys to Three World’s Gone Mad (ISBN 1-58574-416-6)

- Politkovskaya, Anna. A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya ISBN 0-226-67432-0

- Rasizade, Alec. Chechnya: the Achilles heel of Russia. = Contemporary Review (Oxford) in three parts: 1) April 2005 issue, volume 286, number 1671, pages 193–197; 2) May 2005 issue, volume 286, number 1672, pages 277–284; 3) June 2005 issue, volume 286, number 1673, pages 327–332.

- Seirstad, Asne. The Angel of Grozny. ISBN 978-1-84408-395-4

- Wood, Tony. Chechnya: The Case For Independence Book review in The Independent, 2007

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chechnya.

- Official website of the Republic of Chechnya (in Russian)

- Chechnya at Curlie

- AlertNet Chechnya and the North Caucasus at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 September 2012)

- «Chechnya’s Hidden War». Frontline / World Dispatches. USA: Public Broadcasting Service. 22 March 2010. (video)

- Islamist Extremism in Chechnya: A Threat to U.S. Homeland?: Joint Hearing before the Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats and the Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, First Session, April 26, 2013

- (in English) Chechnya Guide Archived 20 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

Not to be confused with Czechia.

|

Chechen Republic |

|

|---|---|

|

Republic |

|

| Чеченская Республика / Chechenskaya Respublika | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Chechen | Нохчийн Республика / Noxçiyn Respublika |

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Шатлакхан Илли Şatlaqan İlli «Shatlak’s Song»[3] |

|

|

|

| Coordinates: 43°24′N 45°43′E / 43.400°N 45.717°ECoordinates: 43°24′N 45°43′E / 43.400°N 45.717°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | North Caucasian[1] |

| Economic region | North Caucasus[2] |

| Capital | Grozny |

| Government | |

| • Body | Parliament[4] |

| • Head[4] | Ramzan Kadyrov[5] |

| Area

[6] |

|

| • Total | 17,300 km2 (6,700 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 76th |

| Population

(2021 Census)[7] |

|

| • Total | 1,510,824 |

| • Rank | 31st |

| • Density | 87/km2 (230/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-CE |

| License plates | 95 |

| OKTMO ID | 96000000 |

| Official languages | Russian;[9] Chechen[10] |

Chechnya (Russian: Чечня́, tr. Chechnyá, IPA: [tɕɪtɕˈnʲa]; Chechen: Нохчийчоь, romanized: Noxçiyçö), officially the Chechen Republic,[a] is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, close to the Caspian Sea. The republic forms a part of the North Caucasian Federal District, and shares land borders with the country of Georgia to its south; with the Russian republics of Dagestan, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia-Alania to its east, north, and west; and with Stavropol Krai to its northwest.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Checheno-Ingush ASSR split into two parts: the Republic of Ingushetia and the Chechen Republic. The latter proclaimed the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, which sought independence. Following the First Chechen War of 1994–1996 with Russia, Chechnya gained de facto independence as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, although de jure it remained a part of Russia. Russian federal control was restored in the Second Chechen War of 1999–2009, with Chechen politics being dominated by Akhmad Kadyrov, and later his son Ramzan Kadyrov.[12]

The republic covers an area of 17,300 square kilometres (6,700 square miles), with a population of over 1.5 million residents as of 2021.[7]

It is home to the indigenous Chechens, part of the Nakh peoples, and of primarily Muslim faith. Grozny is the capital and largest city.

History[edit]

Origin of Chechnya’s population[edit]

According to Leonti Mroveli, the 11th-century Georgian chronicler, the word Caucasian is derived from the Nakh ancestor Kavkas.[13]

According to George Anchabadze of Ilia State University:

The Vainakhs are the ancient natives of the Caucasus. It is noteworthy, that according to the genealogical table drawn up by Leonti Mroveli, the legendary forefather of the Vainakhs was «Kavkas», hence the name Kavkasians, one of the ethnicons met in the ancient Georgian written sources, signifying the ancestors of the Chechens and Ingush. As appears from the above, the Vainakhs, at least by name, are presented as the most «Caucasian» people of all the Caucasians (Caucasus – Kavkas – Kavkasians) in the Georgian historical tradition.[14][15]

American linguist Johanna Nichols «has used language to connect the modern people of the Caucasus region to the ancient farmers of the Fertile Crescent» and her research suggests that «farmers of the region were proto-Nakh-Daghestanians.» Nichols stated: «The Nakh–Dagestanian languages are the closest thing we have to a direct continuation of the cultural and linguistic community that gave rise to Western civilisation.»[16]

Prehistory[edit]

Map of the Caucasian Isthmus

by J. Grassl, 1856

Traces of human settlement dating back to 40,000 BC were found near Lake Kezanoi. Cave paintings, artifacts, and other archaeological evidence indicate continuous habitation for some 8,000 years.[17] People living in these settlements used tools, fire, and clothing made of animal skins.[17]

The Caucasian Epipaleolithic and early Caucasian Neolithic era saw the introduction of agriculture, irrigation, and the domestication of animals in the region.[18] Settlements near Ali-Yurt and Magas, discovered in modern times, revealed tools made out of stone: stone axes, polished stones, stone knives, stones with holes drilled in them, clay dishes etc. Settlements made out of clay bricks were discovered in the plains. In the mountains there were settlements made from stone and surrounded by walls; some of them dated back to 8000 BC.[19] This period also saw the appearance of the wheel (3000 BC), horseback riding, metal works (copper, gold, silver, iron), dishes, armor, daggers, knives and arrow tips in the region. The artifacts were found near Nasare-Cort, Muzhichi, Ja-E-Bortz (alternatively known as Surkha-khi), Abbey-Gove (also known as Nazran or Nasare).[19]

Pre-imperial era[edit]

The German scientist Peter Simon Pallas believed that the Vainakh people (Chechens and Ingush) were the direct descendants from Alania.[20][better source needed] In 1239, the Alania capital of Maghas and the Alan confederacy of the Northern Caucasian highlanders, nations, and tribes was destroyed by Batu Khan (a Mongol leader and a grandson of Genghis Khan).

According to the missionary Pian de Carpine, a part of the Alans had successfully resisted a Mongol siege on a mountain for 12 years:[21]

When they (the Mongols) begin to besiege a fortress, they besiege it for many years, as it happens today with one mountain in the land of the Alans. We believe they have been besieging it for twelve years and

they (the Alans) put up courageous resistance and killed many Tatars, including many noble ones.— Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, report from 1250

This twelve year old siege is not found in any other report, however the Russian historian A.I. Krasnov connected this battle with two Chechen folktales he recorded in 1967 that spoke of an old hunter named Idig who with his companions defended the Dakuoh mountain for 12 years against Tatar-Mongols. He also reported to have found several arrowheads and spears from the 13th century near the very mountain at which the battle took place:[22]

The next year, with the onset of summer, the enemy hordes came again to destroy the highlanders. But even this year they failed to capture the mountain, on which the brave Chechens settled down. The battle lasted twelve years. The main wealth of the Chechens – livestock – was stolen by the enemies. Tired of the long years of hard struggle, the Chechens, believing the assurances of mercy by the enemy, descended from the mountain, but the Mongol-Tatars treacherously killed the majority, and the rest were taken into slavery. This fate was escaped only by Idig and a few of his companions who did not trust the nomads and remained on the mountain. They managed to escape and leave Mount Dakuoh after 12 years of siege.

— Amin Tesaev, The Legend and struggle of the Chechen hero Idig (1238–1250)

In the 14th and 15th centuries, there was frequent warfare between the Chechens, Tamerlan and Tokhtamysh, culminating in the Battle of the Terek River. The Chechen tribes built fortresses, castles, and defensive walls, protecting the mountains from the invaders. Part of the lowland tribes were occupied by Mongols. However, during the mid-14th century a strong Chechen kingdom called Simsir emerged under Khour Ela, a Chechen king that led the Chechen politics and wars. He was in charge of an army of Chechens against the rogue warlord Mamai and defeated him in the Battle of Tatar-tup in 1362. The kingdom of Simsir met its end during the Timurid invasion of the Caucasus, when Khour Ela allied himself with the Golden Horde Khan Tokhtamysh in the Battle of the Terek River. Timur sought to punish the highlanders for their allegiance to Tokhtamysh and as a consequence invaded Simsir in 1395.[23]