elen khvichia

Знаток

(281),

закрыт

12 лет назад

Какое окончание в слове «Эйфелева (я)». Как правильно говорить и писать «Эйфелева (я) башня»?

Ответов: 11

Как ни странно, часто приходилось слышать, что люди говорят :»Эйфелевая башня». И пишут точно так же. Конечно же, это не правильно.

Давайте сначала взглянем на это знаменитое сооружение.

А теперь давайте разберемся, откуда пошло название башни.

Главным конструктором символа Парижа был Гюстав Эйфель, вот в честь него башня и названа.

Башня (чья?)Эйфелева.

Вот например:

Картина (чья?) Врубеля. Мы же не говорим Врубилевая картина. Так почему же мы говорим Эйфелевая башня ?

Правильный вариант :

Эйфелева башня .

3

Нравится

Поскольку само название архаично и появилось во второй половине 19 века, то тогда использовался вариант образования названий от имен собственных с помощью добавления «-ов/-ова». Поэтому правильно Эйфелева башня. Ср.: Брюсова башня, Макарова гора, Монахов пруд и т. д. Для современного русского языка такие способы словообразования нехарактерны. Если бы башню построили лет на 100 позже, то называлась бы она «вышка ЭйфЕля», или на английский манер — Эйфель-тауэр.

2

Нравится

Знаменитую на весь мир башню-символ Парижа задумал, сделал расчёты и соорудил инженер Эйфель. И её называют его именем. Значит, по логике, чья башня? Эйфелева, т. е. его. Если-же сказать, Эйфелевая, то это будет означать — какая.

Выходит, правильно сказать Эйфелева…

1

Нравится

Самая знаменитая башня мира названа в честь главного конструктора Гюстава Эйфеля. Следовательно, к слову «башня» необходимо ставить вопрос: чья? Ответ: Эйфелева.

Если бы мы справышавали: какая, ответ был бы: эйфелевая. Только не совсем понятно было бы значение.

Правильное написание: Эйфелева башня.

1

Нравится

Визитной карточкой города Парижа является металлическая ажурная башня, открытая ко Всемирной выставке в начале прошлого столетия. Её конструктором был инженер Эйфель. Его детище было названо в его честь.

Башня чья? Эйфелева.

С помощью суффикса -ев-/-ов образуются притяжательные прилагательные, например:

В.И. Даль — Далев словарь;

Чингизхан — Чингизханово войско;

Перун — Перуновы стрелы:

Пифагор — Пифагорова теорема.

Сделаем правильный выбор в пользу написания Эйфелева башня с окончанием -а, так как существительное «башня» имеет категорию женского рода.

Нравится

Поисковик в Яндексе упорно не хотел даже вводить запрос «Эйфелевая», из чего сразу можно было сделать вывод, что писать и говорить так совершенно неправильно.

Башня (чья?) Эйфелева. Для справки: возведена Гюставом Эйфелем в дню выставки в Париже (1889 год). Название изначально у нее было другое — «300-метровая башня».

Кстати говоря, как только не изгаляются над названием этой монументальной железной конструкции! Встречаются, помимо «Эйфелевая», следующие варианты: «Эфилевская», «Эльфивая», Эфелейвая» и т. д.

4

Нравится

Конечно же правильно-Эйфелева башня. Очень красивое сооружение, недооцененное сразу же после постройки. Сегодня это самая узнаваемая достопримечательность Парижа. Названа в честь конструктора Гюстава Эйфеля, который называл ее просто «300 метровая башня»

1

Нравится

конструктор ЭйфЕль, значит ЭйфЕлева башня

Нравится

Правильным названием главной достопримечательности Франции является Эйфелева башня, без буквы «я» на конце.

Своё название она получила благодаря своему архитектору, который её создал, а именно Гюставу Эйфелю.

Нравится

Тут всё просто, задайте вопрос, чья это башня?

Ответ Эйфелева (фамилия её создателя), значит так и будет правильно Эйфелева, а не как-то иначе.

Остальные варианты, иногда встречаются, но всё больше в разговорной речи и они ошибочные.

1

Нравится

Она не может быть «Эйфелевая» ведь она не из «эйфеля» изготовлена, а из стали. Она «Эйфелева башня» потому как отвечает на вопрос «чья?» а не «из чего?» или «какая?»

И крайне ошибочно называют ее Эйфелевая, слышал это не раз, и даже от дикторов — слух режет.

По такому же принципу зовется к примеру «Адамово яблоко» а не «Адамовое яблоко»

Нравится

1

4 ответа:

2

0

Эйфелева или «Эйфелевая» башня?

Чтобы выбрать правильное написание данного имени собственного, вспомню, что знаменитую башню, состоящую из более 1500 металлических конструкций, создал французский инженер Эйфель в конце девятнадцатого века (1889 г.), то есть более ста лет назад, к открытию международной выставки. Предполагалось, что она простоит ровно столько, сколько продлится выставка. Но потом её не стали разбирать, а начали использовать как радиомачту. И эта ажурная башня, несмотря на тяжеловесность её составляющих деталей (7 тысяч тонн), настолько полюбилась парижанам, что её «забыли» разобрать. Несколько раз возникал вопрос о том, чтобы её разобрать, но так и не дошли руки. Так и украшает она центр Парижа до сих пор и является визитной карточкой столицы Франции, как и Колизей — Рима.

А в выборе написания руководствуюсь тем, что задам вопрос:

башня чья? Эйфелева, то есть принадлежит Эйфелю.

Правильно пишется Эйфелева башня, так как в этом названии используется притяжательное прилагательное с суффиксом -ев-.

Аналогично:

Даль — Далев слоарь;

Чингисхан — Чингисханово войско.

1

0

Эйфелева башня называется так по имени ее создателя Гюстава Эйфеля. Эйфелева — это притяжательное прилагательное, указывающее на принадлежность определенному лицу, по аналогии «мамина шляпа», «папино пальто». Просто сейчас притяжательное прилагателное Эйфелева стало именем собственным.

1

0

Символ Парижа был построен инженером по фамилии Эйфель и многократно уничтожался в разных фантастических произведениях. В реальности эту башню однажды продали на металлолом, но это было лишь удачной аферой мошенников.

На самом деле никто Эйфелеву башню сносить не собирается, потому что представить себе столицу Франции без этого сооружения сейчас невозможно.

Правильно ее называть используя притяжательное прилагательное Эйфелева, как башня, которая принадлежит творчеству Эйфеля.

0

0

Чтобы узнать правильный ответ,достаточно просто набрать в википедии : Эйфелева башня и он вам выдаст правильное правописание. Так вот, правильное правописание :Эйфелева башня.Почему?Потому что название башни пишется и произносится именно так.

Читайте также

«Породистые» — это прилагательное. А окончание имен прилагательных определяется по вопросу от имени существительного. Какое окончание будет в вопросе, такое окончание будет и в прилагательном. Главное существительное для слова «породистые» — «собаки». Зададим вопрос: собаки (какие?). В вопросе окончание -ие, значит, и в прилагательном окончание -ие (-ые).

Поэтому ответ: Три породистые собаки.

Правильно будет «конкурентоспособный» (без дефиса).

Объяснить можно тем, что -н- является суффиксом — например, прилагательного «конкурентный», — и не относится к корню, поэтому в образовании слова «конкурентоспособный» не участвует.

Аббревиатура ГОСТ представляет собой слово, образованное из начальных звуков слов, которые входят в исходное словосочетание: ГОсударственный СТандарт = ГОСТ.

Заметьте, ведущее (опорное) слово в этой аббревиатуре стандарт представляет собой имя существительное мужского рода.

По существующим правилам русского языка аббревиатуры склоняются, если они заканчиваются словом мужского рода.

Поэтому правильно говорить (естественно, и писать): изделия сделаны по ГОСТу, выполнены в соответствии с ГОСТом.

Также склоняются, например, такие аббревиатуры звукового характера с опорным словом мужского рода, как МХАТ, ГАБТ.

Чтобы правильно просклонять числительное восемьсот, сразу определим, что по сооставу оно является сложным, а это значит, что изменяются оба корня слова и внутри окажется одно из окончаний, вот такие чудеса.

В парадигме склонения этого количественного числительного особый интерес представляет форма родительного падежа, в образовании которой часто бывают морфологические ошибки. Как правильно сказать или написать, нет чего? восьмисот книг или восьмиста книг?

Чтобы выбрать правильный вариант, изменим рассматриваемое числительное по падежам:

и.п. что? восемь-сот_ книг

р.п. полка для чего? для восьм-и-сот_ книг

д.п. иду к чему? к восьм-и-ст-ам книгам

в.п. переберу что? восемь_сот_ книг

т.п. интересуюсь чем? восемь-ю-ст-ами книг-ами

п.п. поведаю о чем? о восьм-и-ст-ах книгах.

Слово «стеклянный» пишется с двумя буквами НН, т.к. является исключением

На чтение 3 мин Просмотров 27 Опубликовано 15.12.2021

Иногда слово пишут с ошибками не потому, что не знают правила, а потому, что не знают истории предмета, который оно называет. Да, это вполне реально, если обратиться к словам «Эйфелевая» или «Эйфелева» башня.

Как пишется правильно: «Эйфелевая» или «Эйфелева» башня?

Многие считают, что первое слово — обычное прилагательное, и поэтому присоединяют окончание —АЯ. Действительно, башня (какая?) Эйфелевая — рассуждают они.

Однако это неверно. Первое слово — не качественное, а притяжательное прилагательное. Оно образовано от фамилии архитектора, спроектировавшего это сооружение. Поэтому башня (чья?) Эйфелева.

Это притяжательное прилагательное образовано с помощью суффикса -ОВ- аналогично словам отцов ремень, купцов дом. В форме женского рода имеется окончание -А: старикова дочь, Эйфелева башня.

Примеры предложений для тренировки

- Первоочередным пунктом нашего плана посещения достопримечательностей Парижа была Эйфелева башня — символ города.

- Эйфелева башня возвышается над Парижем и притягивает к себе, как магнит, всех туристов.

Неправильное написание

БА́ШНЯ, -и, род. мн. —шен, дат. —шням, ж. 1. Высокое строение круглой, четырехгранной или многогранной формы, стоящее отдельно или являющееся частью здания. Кремлевские башни. Телевизионная башня. Силосная башня.

Все значения слова «башня»

-

Довольно много величественных зданий – церкви, музеи, Эйфелева башня – в общем, типичный путеводитель.

-

Он выяснил, что люди, чтобы ориентироваться в сложных средах и составить внутреннюю ментальную карту устройства города, опираются на весьма специфические элементы дизайна – сочетание указателей (Эйфелева башня); границ, которые должны быть чётко обозначены видимыми поверхностями (линии фасадов вдоль парижских бульваров); и демаркированные пути, которые связывают основные пункты, или узлы, такие как площади, скверы и большие перекрёстки.

-

Пирамиды стоят долго, Эйфелева башня так долго не простоит.

- (все предложения)

- башенка

- донжон

- шпиль

- купол

- пилон

- (ещё синонимы…)

- Париж

- башня

- достопримечательность

- француз

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- Разбор по составу слова «башня»

| The Eiffel Tower | |

|---|---|

|

La tour Eiffel |

|

Seen from the Champ de Mars |

|

|

|

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1889 to 1930[I] | |

| General information | |

| Type | Observation tower Broadcasting tower |

| Location | 7th arrondissement, Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48°51′29.6″N 2°17′40.2″E / 48.858222°N 2.294500°ECoordinates: 48°51′29.6″N 2°17′40.2″E / 48.858222°N 2.294500°E |

| Construction started | 28 January 1887; 135 years ago |

| Completed | 15 March 1889; 133 years ago |

| Opening | 31 March 1889; 133 years ago |

| Owner | City of Paris, France |

| Management | Société d’Exploitation de la Tour Eiffel (SETE) |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 300 m (984 ft)[1] |

| Tip | 330 m (1,083 ft) |

| Top floor | 276 m (906 ft)[1] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3[2] |

| Lifts/elevators | 8[2] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Stephen Sauvestre |

| Structural engineer | Maurice Koechlin Émile Nouguier |

| Main contractor | Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel |

| Website | |

| toureiffel.paris/en | |

| References | |

| I. ^ «Eiffel Tower». Emporis. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. |

The Eiffel Tower ( EYE-fəl; French: tour Eiffel [tuʁ‿ɛfɛl] (listen)) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed «La dame de fer» (French for «Iron Lady»), it was constructed from 1887 to 1889 as the centerpiece of the 1889 World’s Fair. Although initially criticised by some of France’s leading artists and intellectuals for its design, it has since become a global cultural icon of France and one of the most recognisable structures in the world.[3] The Eiffel Tower is the most visited monument with an entrance fee in the world: 6.91 million people ascended it in 2015. It was designated a monument historique in 1964, and was named part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site («Paris, Banks of the Seine») in 1991.[4]

The tower is 330 metres (1,083 ft) tall,[5] about the same height as an 81-storey building, and the tallest structure in Paris. Its base is square, measuring 125 metres (410 ft) on each side. During its construction, the Eiffel Tower surpassed the Washington Monument to become the tallest human-made structure in the world, a title it held for 41 years until the Chrysler Building in New York City was finished in 1930. It was the first structure in the world to surpass both the 200-metre and 300-metre mark in height. Due to the addition of a broadcasting aerial at the top of the tower in 1957, it is now taller than the Chrysler Building by 5.2 metres (17 ft). Excluding transmitters, the Eiffel Tower is the second tallest free-standing structure in France after the Millau Viaduct.

The tower has three levels for visitors, with restaurants on the first and second levels. The top level’s upper platform is 276 m (906 ft) above the ground – the highest observation deck accessible to the public in the European Union. Tickets can be purchased to ascend by stairs or lift to the first and second levels. The climb from ground level to the first level is over 300 steps, as is the climb from the first level to the second, making the entire ascent a 600 step climb. Although there is a staircase to the top level, it is usually accessible only by lift.

History

Origin

The design of the Eiffel Tower is attributed to Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, two senior engineers working for the Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel. It was envisioned after discussion about a suitable centerpiece for the proposed 1889 Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair to celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution. Eiffel openly acknowledged that inspiration for a tower came from the Latting Observatory built in New York City in 1853.[6] In May 1884, working at home, Koechlin made a sketch of their idea, described by him as «a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top, joined together by metal trusses at regular intervals».[7] Eiffel initially showed little enthusiasm, but he did approve further study, and the two engineers then asked Stephen Sauvestre, the head of the company’s architectural department, to contribute to the design. Sauvestre added decorative arches to the base of the tower, a glass pavilion to the first level, and other embellishments.

The new version gained Eiffel’s support: he bought the rights to the patent on the design which Koechlin, Nougier, and Sauvestre had taken out, and the design was put on display at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in the autumn of 1884 under the company name. On 30 March 1885, Eiffel presented his plans to the Société des Ingénieurs Civils; after discussing the technical problems and emphasising the practical uses of the tower, he finished his talk by saying the tower would symbolise

[n]ot only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France’s gratitude.[8]

Little progress was made until 1886, when Jules Grévy was re-elected as president of France and Édouard Lockroy was appointed as minister for trade. A budget for the exposition was passed and, on 1 May, Lockroy announced an alteration to the terms of the open competition being held for a centrepiece to the exposition, which effectively made the selection of Eiffel’s design a foregone conclusion, as entries had to include a study for a 300 m (980 ft) four-sided metal tower on the Champ de Mars.[8] (A 300-metre tower was then considered a herculean engineering effort). On 12 May, a commission was set up to examine Eiffel’s scheme and its rivals, which, a month later, decided that all the proposals except Eiffel’s were either impractical or lacking in details.

After some debate about the exact location of the tower, a contract was signed on 8 January 1887. Eiffel signed it acting in his own capacity rather than as the representative of his company, the contract granting him 1.5 million francs toward the construction costs: less than a quarter of the estimated 6.5 million francs. Eiffel was to receive all income from the commercial exploitation of the tower during the exhibition and for the next 20 years. He later established a separate company to manage the tower, putting up half the necessary capital himself.[9]

The Crédit Industriel et Commercial (C.I.C.) helped finance the construction of the Eiffel Tower. According to a New York Times investigation into France’s colonial legacy in Haiti, at the time of the tower’s construction, the bank was acquiring funds from predatory loans related to the Haiti indemnity controversy – a debt forced upon Haiti by France to pay for slaves lost following the Haitian Revolution – and transferring Haiti’s wealth into France. The Times reported that the C.I.C. benefited from a loan that required the Haitian Government to pay the bank and its partner nearly half of all taxes the Haitian government collected on exports, writing that by «effectively choking off the nation’s primary source of income», the C.I.C. «left a crippling legacy of financial extraction and dashed hopes — even by the standards of a nation with a long history of both.»[10]

Artists’ protest

Caricature of Gustave Eiffel comparing the Eiffel tower to the Pyramids, published in Le Temps, February 14, 1887.

The proposed tower had been a subject of controversy, drawing criticism from those who did not believe it was feasible and those who objected on artistic grounds. Prior to the Eiffel Tower’s construction, no structure had ever been constructed to a height of 300 m, or even 200 m for that matter,[11] and many people believed it was impossible. These objections were an expression of a long-standing debate in France about the relationship between architecture and engineering. It came to a head as work began at the Champ de Mars: a «Committee of Three Hundred» (one member for each metre of the tower’s height) was formed, led by the prominent architect Charles Garnier and including some of the most important figures of the arts, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod and Jules Massenet. A petition called «Artists against the Eiffel Tower» was sent to the Minister of Works and Commissioner for the Exposition, Adolphe Alphand, and it was published by Le Temps on 14 February 1887:

We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection … of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower … To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years … we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.[12]

Gustave Eiffel responded to these criticisms by comparing his tower to the Egyptian pyramids: «My tower will be the tallest edifice ever erected by man. Will it not also be grandiose in its way? And why would something admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris?»[13] These criticisms were also dealt with by Édouard Lockroy in a letter of support written to Alphand, sardonically saying,[14] «Judging by the stately swell of the rhythms, the beauty of the metaphors, the elegance of its delicate and precise style, one can tell this protest is the result of collaboration of the most famous writers and poets of our time», and he explained that the protest was irrelevant since the project had been decided upon months before, and construction on the tower was already under way.

Indeed, Garnier was a member of the Tower Commission that had examined the various proposals, and had raised no objection. Eiffel was similarly unworried, pointing out to a journalist that it was premature to judge the effect of the tower solely on the basis of the drawings, that the Champ de Mars was distant enough from the monuments mentioned in the protest for there to be little risk of the tower overwhelming them, and putting the aesthetic argument for the tower: «Do not the laws of natural forces always conform to the secret laws of harmony?»[15]

Some of the protesters changed their minds when the tower was built; others remained unconvinced.[16] Guy de Maupassant supposedly ate lunch in the tower’s restaurant every day because it was the one place in Paris where the tower was not visible.[17]

By 1918, it had become a symbol of Paris and of France after Guillaume Apollinaire wrote a nationalist poem in the shape of the tower (a calligram) to express his feelings about the war against Germany.[18] Today, it is widely considered to be a remarkable piece of structural art, and is often featured in films and literature.

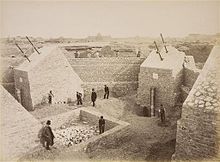

Construction

Work on the foundations started on 28 January 1887.[19] Those for the east and south legs were straightforward, with each leg resting on four 2 m (6.6 ft) concrete slabs, one for each of the principal girders of each leg. The west and north legs, being closer to the river Seine, were more complicated: each slab needed two piles installed by using compressed-air caissons 15 m (49 ft) long and 6 m (20 ft) in diameter driven to a depth of 22 m (72 ft)[20] to support the concrete slabs, which were 6 m (20 ft) thick. Each of these slabs supported a block of limestone with an inclined top to bear a supporting shoe for the ironwork.

Each shoe was anchored to the stonework by a pair of bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long. The foundations were completed on 30 June, and the erection of the ironwork began. The visible work on-site was complemented by the enormous amount of exacting preparatory work that took place behind the scenes: the drawing office produced 1,700 general drawings and 3,629 detailed drawings of the 18,038 different parts needed.[21] The task of drawing the components was complicated by the complex angles involved in the design and the degree of precision required: the position of rivet holes was specified to within 1 mm (0.04 in) and angles worked out to one second of arc.[22] The finished components, some already riveted together into sub-assemblies, arrived on horse-drawn carts from a factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret and were first bolted together, with the bolts being replaced with rivets as construction progressed. No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit, it was sent back to the factory for alteration. In all, 18,038 pieces were joined together using 2.5 million rivets.[19]

At first, the legs were constructed as cantilevers, but about halfway to the first level construction was paused to create a substantial timber scaffold. This renewed concerns about the structural integrity of the tower, and sensational headlines such as «Eiffel Suicide!» and «Gustave Eiffel Has Gone Mad: He Has Been Confined in an Asylum» appeared in the tabloid press.[23] At this stage, a small «creeper» crane designed to move up the tower was installed in each leg. They made use of the guides for the lifts which were to be fitted in the four legs. The critical stage of joining the legs at the first level was completed by the end of March 1888.[19] Although the metalwork had been prepared with the utmost attention to detail, provision had been made to carry out small adjustments to precisely align the legs; hydraulic jacks were fitted to the shoes at the base of each leg, capable of exerting a force of 800 tonnes, and the legs were intentionally constructed at a slightly steeper angle than necessary, being supported by sandboxes on the scaffold. Although construction involved 300 on-site employees,[19] due to Eiffel’s safety precautions and the use of movable gangways, guardrails and screens, only one person died.[24]

-

18 July 1887:

The start of the erection of the metalwork -

7 December 1887:

Construction of the legs with scaffolding -

20 March 1888:

Completion of the first level -

15 May 1888:

Start of construction on the second stage -

21 August 1888:

Completion of the second level -

26 December 1888:

Construction of the upper stage -

15 March 1889:

Construction of the cupola

Lifts

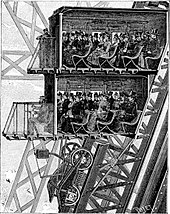

The Roux, Combaluzier & Lepape lifts during construction. Note the drive sprockets and chain in the foreground.

Equipping the tower with adequate and safe passenger lifts was a major concern of the government commission overseeing the Exposition. Although some visitors could be expected to climb to the first level, or even the second, lifts clearly had to be the main means of ascent.[25]

Constructing lifts to reach the first level was relatively straightforward: the legs were wide enough at the bottom and so nearly straight that they could contain a straight track, and a contract was given to the French company Roux, Combaluzier & Lepape for two lifts to be fitted in the east and west legs.[26] Roux, Combaluzier & Lepape used a pair of endless chains with rigid, articulated links to which the car was attached. Lead weights on some links of the upper or return sections of the chains counterbalanced most of the car’s weight. The car was pushed up from below, not pulled up from above: to prevent the chain buckling, it was enclosed in a conduit. At the bottom of the run, the chains passed around 3.9 m (12 ft 10 in) diameter sprockets. Smaller sprockets at the top guided the chains.[26]

The Otis lifts originally fitted in the north and south legs

Installing lifts to the second level was more of a challenge because a straight track was impossible. No French company wanted to undertake the work. The European branch of Otis Brothers & Company submitted a proposal but this was rejected: the fair’s charter ruled out the use of any foreign material in the construction of the tower. The deadline for bids was extended but still no French companies put themselves forward, and eventually the contract was given to Otis in July 1887.[27] Otis were confident they would eventually be given the contract and had already started creating designs.[citation needed]

The car was divided into two superimposed compartments, each holding 25 passengers, with the lift operator occupying an exterior platform on the first level. Motive power was provided by an inclined hydraulic ram 12.67 m (41 ft 7 in) long and 96.5 cm (38.0 in) in diameter in the tower leg with a stroke of 10.83 m (35 ft 6 in): this moved a carriage carrying six sheaves. Five fixed sheaves were mounted higher up the leg, producing an arrangement similar to a block and tackle but acting in reverse, multiplying the stroke of the piston rather than the force generated. The hydraulic pressure in the driving cylinder was produced by a large open reservoir on the second level. After being exhausted from the cylinder, the water was pumped back up to the reservoir by two pumps in the machinery room at the base of the south leg. This reservoir also provided power to the lifts to the first level.[citation needed]

The original lifts for the journey between the second and third levels were supplied by Léon Edoux. A pair of 81 m (266 ft) hydraulic rams were mounted on the second level, reaching nearly halfway up to the third level. One lift car was mounted on top of these rams: cables ran from the top of this car up to sheaves on the third level and back down to a second car. Each car travelled only half the distance between the second and third levels and passengers were required to change lifts halfway by means of a short gangway. The 10-ton cars each held 65 passengers.[28]

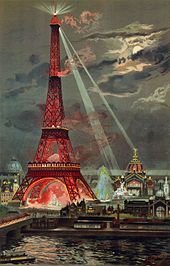

Inauguration and the 1889 exposition

View of the 1889 World’s Fair

The main structural work was completed at the end of March 1889 and, on 31 March, Eiffel celebrated by leading a group of government officials, accompanied by representatives of the press, to the top of the tower.[16] Because the lifts were not yet in operation, the ascent was made by foot, and took over an hour, with Eiffel stopping frequently to explain various features. Most of the party chose to stop at the lower levels, but a few, including the structural engineer, Émile Nouguier, the head of construction, Jean Compagnon, the President of the City Council, and reporters from Le Figaro and Le Monde Illustré, completed the ascent. At 2:35 pm, Eiffel hoisted a large Tricolour to the accompaniment of a 25-gun salute fired at the first level.[29]

There was still work to be done, particularly on the lifts and facilities, and the tower was not opened to the public until nine days after the opening of the exposition on 6 May; even then, the lifts had not been completed. The tower was an instant success with the public, and nearly 30,000 visitors made the 1,710-step climb to the top before the lifts entered service on 26 May.[30]

Tickets cost 2 francs for the first level, 3 for the second, and 5 for the top, with half-price admission on Sundays,[31] and by the end of the exhibition there had been 1,896,987 visitors.[3]

After dark, the tower was lit by hundreds of gas lamps, and a beacon sent out three beams of red, white and blue light. Two searchlights mounted on a circular rail were used to illuminate various buildings of the exposition. The daily opening and closing of the exposition were announced by a cannon at the top.[citation needed]

Illumination of the tower at night during the exposition

On the second level, the French newspaper Le Figaro had an office and a printing press, where a special souvenir edition, Le Figaro de la Tour, was made. There was also a pâtisserie.[citation needed]

At the top, there was a post office where visitors could send letters and postcards as a memento of their visit. Graffitists were also catered for: sheets of paper were mounted on the walls each day for visitors to record their impressions of the tower. Gustave Eiffel described some of the responses as vraiment curieuse («truly curious»).[32]

Famous visitors to the tower included the Prince of Wales, Sarah Bernhardt, «Buffalo Bill» Cody (his Wild West show was an attraction at the exposition) and Thomas Edison.[30] Eiffel invited Edison to his private apartment at the top of the tower, where Edison presented him with one of his phonographs, a new invention and one of the many highlights of the exposition.[33] Edison signed the guestbook with this message:

To M Eiffel the Engineer the brave builder of so gigantic and original specimen of modern Engineering from one who has the greatest respect and admiration for all Engineers including the Great Engineer the Bon Dieu, Thomas Edison.

Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years. It was to be dismantled in 1909, when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris. The City had planned to tear it down (part of the original contest rules for designing a tower was that it should be easy to dismantle) but as the tower proved to be valuable for radio telegraphy, it was allowed to remain after the expiry of the permit, and from 1910 it also became part of the International Time Service.[34]

Eiffel made use of his apartment at the top of the tower to carry out meteorological observations, and also used the tower to perform experiments on the action of air resistance on falling bodies.[35]

Subsequent events

For the 1900 Exposition Universelle, the lifts in the east and west legs were replaced by lifts running as far as the second level constructed by the French firm Fives-Lille. These had a compensating mechanism to keep the floor level as the angle of ascent changed at the first level, and were driven by a similar hydraulic mechanism as the Otis lifts, although this was situated at the base of the tower. Hydraulic pressure was provided by pressurised accumulators located near this mechanism.[27] At the same time the lift in the north pillar was removed and replaced by a staircase to the first level. The layout of both first and second levels was modified, with the space available for visitors on the second level. The original lift in the south pillar was removed 13 years later.[citation needed]

On 19 October 1901, Alberto Santos-Dumont, flying his No.6 airship, won a 100,000-franc prize offered by Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe for the first person to make a flight from St. Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back in less than half an hour.[36]

Many innovations took place at the Eiffel Tower in the early 20th century. In 1910, Father Theodor Wulf measured radiant energy at the top and bottom of the tower. He found more at the top than expected, incidentally discovering what are known today as cosmic rays.[37] Two years later, on 4 February 1912, Austrian tailor Franz Reichelt died after jumping from the first level of the tower (a height of 57 m) to demonstrate his parachute design.[38] In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, a radio transmitter located in the tower jammed German radio communications, seriously hindering their advance on Paris and contributing to the Allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne.[39] From 1925 to 1934, illuminated signs for Citroën adorned three of the tower’s sides, making it the tallest advertising space in the world at the time.[40] In April 1935, the tower was used to make experimental low-resolution television transmissions, using a shortwave transmitter of 200 watts power. On 17 November, an improved 180-line transmitter was installed.[41]

On two separate but related occasions in 1925, the con artist Victor Lustig «sold» the tower for scrap metal.[42] A year later, in February 1926, pilot Leon Collet was killed trying to fly under the tower. His aircraft became entangled in an aerial belonging to a wireless station.[43] A bust of Gustave Eiffel by Antoine Bourdelle was unveiled at the base of the north leg on 2 May 1929.[44] In 1930, the tower lost the title of the world’s tallest structure when the Chrysler Building in New York City was completed.[45] In 1938, the decorative arcade around the first level was removed.[46]

Upon the German occupation of Paris in 1940, the lift cables were cut by the French. The tower was closed to the public during the occupation and the lifts were not repaired until 1946.[47] In 1940, German soldiers had to climb the tower to hoist a swastika-centered Reichskriegsflagge,[48] but the flag was so large it blew away just a few hours later, and was replaced by a smaller one.[49] When visiting Paris, Hitler chose to stay on the ground. When the Allies were nearing Paris in August 1944, Hitler ordered General Dietrich von Choltitz, the military governor of Paris, to demolish the tower along with the rest of the city. Von Choltitz disobeyed the order.[50] On 25 August, before the Germans had been driven out of Paris, the German flag was replaced with a Tricolour by two men from the French Naval Museum, who narrowly beat three men led by Lucien Sarniguet, who had lowered the Tricolour on 13 June 1940 when Paris fell to the Germans.[47]

A fire started in the television transmitter on 3 January 1956, damaging the top of the tower. Repairs took a year, and in 1957, the present radio aerial was added to the top.[51] In 1964, the Eiffel Tower was officially declared to be a historical monument by the Minister of Cultural Affairs, André Malraux.[52] A year later, an additional lift system was installed in the north pillar.[53]

According to interviews, in 1967, Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau negotiated a secret agreement with Charles de Gaulle for the tower to be dismantled and temporarily relocated to Montreal to serve as a landmark and tourist attraction during Expo 67. The plan was allegedly vetoed by the company operating the tower out of fear that the French government could refuse permission for the tower to be restored in its original location.[54]

In 1982, the original lifts between the second and third levels were replaced after 97 years in service. These had been closed to the public between November and March because the water in the hydraulic drive tended to freeze. The new cars operate in pairs, with one counterbalancing the other, and perform the journey in one stage, reducing the journey time from eight minutes to less than two minutes. At the same time, two new emergency staircases were installed, replacing the original spiral staircases. In 1983, the south pillar was fitted with an electrically driven Otis lift to serve the Jules Verne restaurant.[citation needed] The Fives-Lille lifts in the east and west legs, fitted in 1899, were extensively refurbished in 1986. The cars were replaced, and a computer system was installed to completely automate the lifts. The motive power was moved from the water hydraulic system to a new electrically driven oil-filled hydraulic system, and the original water hydraulics were retained solely as a counterbalance system.[53] A service lift was added to the south pillar for moving small loads and maintenance personnel three years later.[citation needed]

Robert Moriarty flew a Beechcraft Bonanza under the tower on 31 March 1984.[55] In 1987, A.J. Hackett made one of his first bungee jumps from the top of the Eiffel Tower, using a special cord he had helped develop. Hackett was arrested by the police.[56] On 27 October 1991, Thierry Devaux, along with mountain guide Hervé Calvayrac, performed a series of acrobatic figures while bungee jumping from the second floor of the tower. Facing the Champ de Mars, Devaux used an electric winch between figures to go back up to the second floor. When firemen arrived, he stopped after the sixth jump.[57]

The tower is the focal point of New Year’s Eve and Bastille Day (14 July) celebrations in Paris.

For its «Countdown to the Year 2000» celebration on 31 December 1999, flashing lights and high-powered searchlights were installed on the tower. During the last three minutes of the year, the lights were turned on starting from the base of the tower and continuing to the top to welcome 2000 with a huge fireworks show. An exhibition above a cafeteria on the first floor commemorates this event. The searchlights on top of the tower made it a beacon in Paris’s night sky, and 20,000 flashing bulbs gave the tower a sparkly appearance for five minutes every hour on the hour.[58]

The lights sparkled blue for several nights to herald the new millennium on 31 December 2000. The sparkly lighting continued for 18 months until July 2001. The sparkling lights were turned on again on 21 June 2003, and the display was planned to last for 10 years before they needed replacing.[59]

The tower received its 200,000,000th guest on 28 November 2002.[60] The tower has operated at its maximum capacity of about 7 million visitors per year since 2003.[61] In 2004, the Eiffel Tower began hosting a seasonal ice rink on the first level.[62] A glass floor was installed on the first level during the 2014 refurbishment.[63]

Design

Material

The Eiffel Tower from below

The puddle iron (wrought iron) of the Eiffel Tower weighs 7,300 tonnes,[64] and the addition of lifts, shops and antennae have brought the total weight to approximately 10,100 tonnes.[65] As a demonstration of the economy of design, if the 7,300 tonnes of metal in the structure were melted down, it would fill the square base, 125 metres (410 ft) on each side, to a depth of only 6.25 cm (2.46 in) assuming the density of the metal to be 7.8 tonnes per cubic metre.[66] Additionally, a cubic box surrounding the tower (324 m × 125 m × 125 m) would contain 6,200 tonnes of air, weighing almost as much as the iron itself. Depending on the ambient temperature, the top of the tower may shift away from the sun by up to 18 cm (7 in) due to thermal expansion of the metal on the side facing the sun.[67]

Wind considerations

When it was built, many were shocked by the tower’s daring form. Eiffel was accused of trying to create something artistic with no regard to the principles of engineering. However, Eiffel and his team – experienced bridge builders – understood the importance of wind forces, and knew that if they were going to build the tallest structure in the world, they had to be sure it could withstand them. In an interview with the newspaper Le Temps published on 14 February 1887, Eiffel said:

Is it not true that the very conditions which give strength also conform to the hidden rules of harmony? … Now to what phenomenon did I have to give primary concern in designing the Tower? It was wind resistance. Well then! I hold that the curvature of the monument’s four outer edges, which is as mathematical calculation dictated it should be … will give a great impression of strength and beauty, for it will reveal to the eyes of the observer the boldness of the design as a whole.[68]

He used graphical methods to determine the strength of the tower and empirical evidence to account for the effects of wind, rather than a mathematical formula. Close examination of the tower reveals a basically exponential shape.[69] All parts of the tower were overdesigned to ensure maximum resistance to wind forces. The top half was even assumed to have no gaps in the latticework.[70] In the years since it was completed, engineers have put forward various mathematical hypotheses in an attempt to explain the success of the design. The most recent, devised in 2004 after letters sent by Eiffel to the French Society of Civil Engineers in 1885 were translated into English, is described as a non-linear integral equation based on counteracting the wind pressure on any point of the tower with the tension between the construction elements at that point.[69]

The Eiffel Tower sways by up to 9 cm (3.5 in) in the wind.[71]

Accommodation

Gustave Eiffel’s apartment

When originally built, the first level contained three restaurants – one French, one Russian and one Flemish — and an «Anglo-American Bar». After the exposition closed, the Flemish restaurant was converted to a 250-seat theatre. A promenade 2.6-metre (8 ft 6 in) wide ran around the outside of the first level. At the top, there were laboratories for various experiments, and a small apartment reserved for Gustave Eiffel to entertain guests, which is now open to the public, complete with period decorations and lifelike mannequins of Eiffel and some of his notable guests.[72]

In May 2016, an apartment was created on the first level to accommodate four competition winners during the UEFA Euro 2016 football tournament in Paris in June. The apartment has a kitchen, two bedrooms, a lounge, and views of Paris landmarks including the Seine, Sacré-Cœur, and the Arc de Triomphe.[73]

Passenger lifts

The arrangement of the lifts has been changed several times during the tower’s history. Given the elasticity of the cables and the time taken to align the cars with the landings, each lift, in normal service, takes an average of 8 minutes and 50 seconds to do the round trip, spending an average of 1 minute and 15 seconds at each level. The average journey time between levels is 1 minute. The original hydraulic mechanism is on public display in a small museum at the base of the east and west legs. Because the mechanism requires frequent lubrication and maintenance, public access is often restricted. The rope mechanism of the north tower can be seen as visitors exit the lift.[74]

Engraved names

Names engraved on the tower

Gustave Eiffel engraved on the tower the names of 72 French scientists, engineers and mathematicians in recognition of their contributions to the building of the tower. Eiffel chose this «invocation of science» because of his concern over the artists’ protest. At the beginning of the 20th century, the engravings were painted over, but they were restored in 1986–87 by the Société Nouvelle d’exploitation de la Tour Eiffel, a company operating the tower.[75]

Aesthetics

The tower is painted in three shades: lighter at the top, getting progressively darker towards the bottom to complement the Parisian sky.[76] It was originally reddish brown; this changed in 1968 to a bronze colour known as «Eiffel Tower Brown».[77] In what is expected to be a temporary change, the tower is being painted gold in commemoration of the upcoming 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris.[78][79]

The only non-structural elements are the four decorative grill-work arches, added in Sauvestre’s sketches, which served to make the tower look more substantial and to make a more impressive entrance to the exposition.[80]

A pop-culture movie cliché is that the view from a Parisian window always includes the tower.[81] In reality, since zoning restrictions limit the height of most buildings in Paris to seven storeys, only a small number of tall buildings have a clear view of the tower.[82]

Maintenance

Maintenance of the tower includes applying 60 tons of paint every seven years to prevent it from rusting. The tower has been completely repainted at least 19 times since it was built. Lead paint was still being used as recently as 2001 when the practice was stopped out of concern for the environment.[59][83]

Panorama of Paris and its suburbs from the top of the Eiffel Tower

Tourism

Transport

The nearest Paris Métro station is Bir-Hakeim and the nearest RER station is Champ de Mars-Tour Eiffel.[84] The tower itself is located at the intersection of the quai Branly and the Pont d’Iéna.

Popularity

Number of visitors per year between 1889 and 2004

More than 300 million people have visited the tower since it was completed in 1889.[85] [3] In 2015, there were 6.91 million visitors.[86] The tower is the most-visited paid monument in the world.[87] An average of 25,000 people ascend the tower every day which can result in long queues.[88]

Restaurants

The tower has two restaurants: Le 58 Tour Eiffel on the first level, and Le Jules Verne, a gourmet restaurant with its own lift on the second level. This restaurant has one star in the Michelin Red Guide. It was run by the multi-Michelin star chef Alain Ducasse from 2007 to 2017.[89] As of May 2019, it is managed by three-star chef Frédéric Anton.[90] It owes its name to the famous science-fiction writer Jules Verne. Additionally, there is a champagne bar at the top of the Eiffel Tower.

From 1937 until 1981, there was a restaurant near the top of the tower. It was removed due to structural considerations; engineers had determined it was too heavy and was causing the tower to sag.[91] This restaurant was sold to an American restaurateur and transported to New York and then New Orleans. It was rebuilt on the edge of New Orleans’ Garden District as a restaurant and later event hall.[92]

Replicas

As one of the most iconic landmarks in the world, the Eiffel Tower has been the inspiration for the creation of many replicas and similar towers. An early example is Blackpool Tower in England. The mayor of Blackpool, Sir John Bickerstaffe, was so impressed on seeing the Eiffel Tower at the 1889 exposition that he commissioned a similar tower to be built in his town. It opened in 1894 and is 158.1 m (518 ft) tall.[93] Tokyo Tower in Japan, built as a communications tower in 1958, was also inspired by the Eiffel Tower.[94]

There are various scale models of the tower in the United States, including a half-scale version at the Paris Las Vegas, Nevada, one in Paris, Texas built in 1993, and two 1:3 scale models at Kings Island, located in Mason, Ohio, and Kings Dominion, Virginia, amusement parks opened in 1972 and 1975 respectively. Two 1:3 scale models can be found in China, one in Durango, Mexico that was donated by the local French community, and several across Europe.[95]

In 2011, the TV show Pricing the Priceless on the National Geographic Channel speculated that a full-size replica of the tower would cost approximately US$480 million to build.[96] This would be more than ten times the cost of the original (nearly 8 million in 1890 Francs; ~US$40 million in 2018 dollars).

Communications

The tower has been used for making radio transmissions since the beginning of the 20th century. Until the 1950s, sets of aerial wires ran from the cupola to anchors on the Avenue de Suffren and Champ de Mars. These were connected to longwave transmitters in small bunkers. In 1909, a permanent underground radio centre was built near the south pillar, which still exists today. On 20 November 1913, the Paris Observatory, using the Eiffel Tower as an aerial, exchanged wireless signals with the United States Naval Observatory, which used an aerial in Arlington County, Virginia. The object of the transmissions was to measure the difference in longitude between Paris and Washington, D.C.[97] Today, radio and digital television signals are transmitted from the Eiffel Tower.

FM radio

| Frequency | kW | Service |

|---|---|---|

| 87.8 MHz | 10 | France Inter |

| 89.0 MHz | 10 | RFI Paris |

| 89.9 MHz | 6 | TSF Jazz |

| 90.4 MHz | 10 | Nostalgie |

| 90.9 MHz | 4 | Chante France |

Digital television

A television antenna was first installed on the tower in 1957, increasing its height by 18.7 m (61.4 ft). Work carried out in 2000 added a further 5.3 m (17.4 ft), giving the current height of 324 m (1,063 ft).[59] Analogue television signals from the Eiffel Tower ceased on 8 March 2011.

| Frequency | VHF | UHF | kW | Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 182.25 MHz | 6 | — | 100 | Canal+ |

| 479.25 MHz | — | 22 | 500 | France 2 |

| 503.25 MHz | — | 25 | 500 | TF1 |

| 527.25 MHz | — | 28 | 500 | France 3 |

| 543.25 MHz | — | 30 | 100 | France 5 |

| 567.25 MHz | — | 33 | 100 | M6 |

Illumination copyright

The Eiffel Tower illuminated in 2015

The tower and its image have been in the public domain since 1993, 70 years after Eiffel’s death.[98] In June 1990 a French court ruled that a special lighting display on the tower in 1989 to mark the tower’s 100th anniversary was an «original visual creation» protected by copyright. The Court of Cassation, France’s judicial court of last resort, upheld the ruling in March 1992.[99] The Société d’Exploitation de la Tour Eiffel (SETE) now considers any illumination of the tower to be a separate work of art that falls under copyright.[100] As a result, the SNTE alleges that it is illegal to publish contemporary photographs of the lit tower at night without permission in France and some other countries for commercial use.[101][102] For this reason, it is often rare to find images or videos of the lit tower at night on stock image sites,[103] and media outlets rarely broadcast images or videos of it.[104]

The imposition of copyright has been controversial. The Director of Documentation for what was then called the Société Nouvelle d’exploitation de la Tour Eiffel (SNTE), Stéphane Dieu, commented in 2005: «It is really just a way to manage commercial use of the image, so that it isn’t used in ways [of which] we don’t approve».[105] SNTE made over €1 million from copyright fees in 2002.[106] However, it could also be used to restrict the publication of tourist photographs of the tower at night, as well as hindering non-profit and semi-commercial publication of images of the illuminated tower.[107]

The copyright claim itself has never been tested in courts to date, according to a 2014 article in the Art Law Journal, and there has never been an attempt to track down millions of people who have posted and shared their images of the illuminated tower on the Internet worldwide. It added, however, that permissive situation may arise on commercial use of such images, like in a magazine, on a film poster, or on product packaging.[108]

French doctrine and jurisprudence allows pictures incorporating a copyrighted work as long as their presence is incidental or accessory to the subject being represented,[109] a reasoning akin to the de minimis rule. Therefore, SETE may be unable to claim copyright on photographs of Paris which happen to include the lit tower.

Height changes

The pinnacle height of the Eiffel Tower has changed multiple times over the years as described in the chart below.[110]

| From | To | Height m | Height ft | Type of addition | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 | 1957 | 312.27 | 1,025 | Flagpole | Architectural height of 300 m 984 ft. Tallest freestanding structure in the world until surpassed by the Chrysler Building in 1930. Tallest tower in the world until surpassed by the KCTV Broadcast Tower in 1956. |

| 1957 | 1991 | 320.75 | 1,052 | Antenna | Broadcast antenna added in 1957 which made it the tallest tower in the world until the Tokyo Tower was completed the following year in 1958. |

| 1991 | 1994 | 317.96 | 1,043 | Antenna change | |

| 1994 | 2000 | 318.7 | 1,046 | Antenna change | |

| 2000 | 2022 | 324 | 1,063 | Antenna change | |

| 2022 | Current | 330 | 1,083 | Antenna change | Digital radio antenna hoisted on March 15, 2022.[111] |

Taller structures

The Eiffel Tower was the world’s tallest structure when completed in 1889, a distinction it retained until 1929 when the Chrysler Building in New York City was topped out.[112] The tower also lost its standing as the world’s tallest tower to the Tokyo Tower in 1958 but retains its status as the tallest freestanding (non-guyed) structure in France.

Lattice towers taller than the Eiffel Tower

| Name | Pinnacle height | Year | Country | Town | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tokyo Skytree | 634 m (2,080 ft) | 2011 | Japan | Tokyo | |

| Kyiv TV Tower | 385 m (1,263 ft) | 1973 | Ukraine | Kyiv | |

| Dragon Tower | 336 m (1,102 ft) | 2000 | China | Harbin | |

| Tokyo Tower | 333 m (1,093 ft) | 1958 | Japan | Tokyo | |

| WITI TV Tower | 329.4 m (1,081 ft) | 1962 | United States | Shorewood, Wisconsin | |

| St. Petersburg TV Tower | 326 m (1,070 ft) | 1962 | Russia | Saint Petersburg |

Structures in France taller than the Eiffel Tower

| Name | Pinnacle height | Year | Structure type | Town | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longwave transmitter Allouis | 350 m (1,150 ft) | 1974 | Guyed mast | Allouis | |

| HWU transmitter | 350 m (1,150 ft) | 1971 | Guyed mast | Rosnay | Military VLF transmitter; multiple masts |

| Viaduc de Millau | 343 m (1,125 ft) | 2004 | Bridge pillar | Millau | |

| TV Mast Niort-Maisonnay | 330 m (1,080 ft) | 1978 | Guyed mast | Niort | |

| Transmitter Le Mans-Mayet | 342 m (1,122 ft) | 1993 | Guyed mast | Mayet | |

| La Regine transmitter | 330 m (1,080 ft) | 1973 | Guyed mast | Saissac | Military VLF transmitter |

| Transmitter Roumoules | 330 m (1,080 ft) | 1974 | Guyed mast | Roumoules | Spare transmission mast for longwave; insulated against ground |

See also

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the Paris region

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the world

- List of tallest towers in the world

- List of tallest freestanding structures in the world

- List of tallest freestanding steel structures

- List of transmission sites

- Lattice tower

- Eiffel Tower, 1909–1928 painting series by Robert Delaunay

References

Notes

- ^ a b «Eiffel Tower». CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- ^ a b «Eiffel Tower». Emporis. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b c SETE. «The Eiffel Tower at a glance». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Clayson, S. Hollis (26 February 2020), «Eiffel Tower», Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/obo/9780190922467-0014, ISBN 978-0-19-092246-7, retrieved 14 November 2021

- ^ Reuters (15 March 2022). «Eiffel Tower grows six metres after new antenna attached». Reuters. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Engineering News and American Railway Journal. Vol. 22. G. H. Frost. 1889. p. 482.

- ^ Harvie, p. 78.

- ^ a b Loyrette, p. 116.

- ^ Loyrette, p. 121.

- ^ Apuzzo, Matt; Méheut, Constant; Gebrekidan, Selam; Porter, Catherine (20 May 2022). «How a French Bank Captured Haiti». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ «Diagrams — SkyscraperPage.com». skyscraperpage.com.

- ^ Loyrette, p. 174.

- ^ Paul Souriau; Manon Souriau (1983). The Aesthetics of Movement. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-87023-412-9.

- ^ Harvie, p. 99.

- ^ Loyrette, p. 176.

- ^ a b «The Eiffel Tower». News. The Times. No. 32661. London. 1 April 1889. col B, p. 5.

- ^ Jill Jonnes (2009). Eiffel’s Tower: And the World’s Fair where Buffalo Bill Beguiled Paris, the Artists Quarreled, and Thomas Edison Became a Count. Viking. pp. 163–64. ISBN 978-0-670-02060-7.

- ^ Guillaume Apollinaire (1980). Anne Hyde Greet (ed.). Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War (1913–1916). University of California Press. pp. 411–414. ISBN 978-0-520-01968-3.

- ^ a b c d SETE. «Origins and construction of the Eiffel Tower». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ Loyrette, p. 123.

- ^ Loyrette, p. 148.

- ^ Eiffel, G; The Eiffel TowerPlate X

- ^ Harvie, p. 110.

- ^ «Construction of the Eiffel Tower». wonders-of-the-world.net.

- ^ Vogel, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Vogel, p. 28.

- ^ a b Vogel, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Eiffel, Gustave (1900). La Tour de Trois Cents Mètres (in French). Paris: Société des imprimeries Lemercier. pp. 171–3.

- ^ Harvie, pp. 122–23.

- ^ a b SETE. «The Eiffel Tower during the 1889 Exposition Universelle». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Harvie, pp. 144–45.

- ^ Eiffel, Gustave (1900). La Tour de Trois Cents Mètres. Paris: Lemercier. p. 335.

- ^ Jill Jonnes (23 May 2009). «Thomas Edison at the Eiffel Tower». Wonders and Marvels. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ Michelin Paris: Tourist Guide (5 ed.). Michelin Tyre Public Limited. 1985. p. 52. ISBN 9782060135427.

- ^ Watson, p. 829.

- ^ «M. Santos Dumont’s Balloon». News. The Times. No. 36591. London. 21 October 1901. col A, p. 4.

- ^ Theodor Wulf. Physikalische Zeitschrift. Contains results of the four-day-long observation done by Theodor Wulf at the top of the Eiffel Tower in 1910.

- ^ «L’inventeur d’un parachute se lance de le tour Eiffel et s’écrase sur le sol». Le Petit Parisien (in French). 5 February 1912. p. 1. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (1994). August 1914. Papermac. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-333-30516-4.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (31 March 2018). «40 fascinating facts about the Eiffel Tower». The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Stephen Herbert (2004). A History of Early Television. Vol. 2. Taylor & Francis. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-415-32667-4.

- ^ Piers Letcher (2003). Eccentric France: The Bradt Guide to Mad, Magical and Marvellous France. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-84162-068-8.

- ^ «An air tragedy». The Sunday Times. Perth, WA. 28 February 1926. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Harriss, p. 178.

- ^ Claudia Roth Pierpont (18 November 2002). «The Silver Spire: How two men’s dreams changed the skyline of New York». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012.

- ^ Harriss, p. 195.

- ^ a b Harriss, pp. 180–84.

- ^ «HD Stock Video Footage – The Germans unfurl Nazi flags at the captured Palace of Versailles and Eiffel Tower during the Battle of France». www.criticalpast.com.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (4 February 2016). «Eiffel Tower: 40 fascinating facts». The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Carlo D’Este (2003). Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life. Henry Holt and Company. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-8050-5687-7.

- ^ SETE. «The major events». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Harriss, p. 215.

- ^ a b SETE. «The Eiffel Tower’s lifts». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Nick Auf der Maur (15 September 1980). «How this city nearly got the Eiffel Tower». The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Robert J. Moriarty. «A Bonanza in Paris». Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ Jano Gibson (27 February 2007). «Extreme bid to stretch bungy record». Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ «Tour Eiffel». Thierry Devaux (in French). Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ SETE. «The Eiffel Tower’s illuminations». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ a b c SETE. «All you need to know about the Eiffel Tower» (PDF). Official Eiffel Tower website. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ «The Eiffel Tower». France.com. 23 October 2003. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Denis Cosnard (21 April 2014). «Eiffel Tower renovation work aims to take profits to new heights». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Darwin Porter; Danforth Prince; G. McDonald; H. Mastrini; S. Marker; A. Princz; C. Bánfalvy; A. Kutor; N. Lakos; S. Rowan Kelleher (2006). Frommer’s Europe (9th ed.). Wiley. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-471-92265-0.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower gets glass floor in refurbishment project». BBC News. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ David A. Hanser (2006). Architecture of France. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-313-31902-0.

- ^ DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Europe. Dorling Kindersley. 2012. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-4093-8577-6.

- ^ Harriss, p. 60.

- ^ Harriss, p. 231.

- ^ SETE. «Debate and controversy surrounding the Eiffel Tower». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ a b «Elegant shape of Eiffel Tower solved mathematically by University of Colorado professor». Science Daily. 7 January 2005. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Watson, p. 807.

- ^ SETE. «FAQ: History/Technical». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Caitlin Morton (31 May 2015). «There is a secret apartment at the top of the Eiffel Tower». Architectural Digest. Conde Nast. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Mary Papenfuss (20 May 2016). «Tourists have the chance to get an Eiffel of the view by staying in the Tower for a night». International Business Times. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Eiffel Tower, Paris, France hisour.com. Retrieved 29 August 2021

- ^ SETE (2010). «The Eiffel Tower Laboratory». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ SETE. «The Eiffel Tower gets beautified» (PDF). Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ SETE. «Painting the Eiffel Tower». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Oliver, Huw. «The Eiffel Tower is being painted gold for the 2024 Olympics». Time Out Worldwide. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower receives €50m makeover to make it look more golden for the Olympics». The Independent. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ «History: Development of clear span buildings – Exhibition buildings». Architectural Teaching Resource. Tata Steel Europe, Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ «The Eiffel Tower». France.com. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower (Paris ( 7 th ), 1889)». Structurae. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Bavelier, Ariane (3 December 2013). «Coup de pinceau sur la tour Eiffel». Lefigaro. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ SETE. «Getting to the Eiffel Tower». Official Eiffel Tower website. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ [1]

- ^ «Number of Eiffel Tower visitors falls in wake of Paris attacks». France 24. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Jean-Michel Normand (23 July 2007). «Tour Eiffel et souvenirs de Paris». Le Monde. France. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower reopens to tourists after rare closure for 2-day strike». Fox News. Associated Press. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Dali Wiederhoft. «Eiffel Tower: Sightseeing, restaurants, links, transit». Bonjour Paris. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower in Paris». Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Marcus, Frances Frank (10 December 1986). «New Orleans’s ‘Eiffel Tower’«. The New York Times. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Jabari (15 September 2015). «Where you can find pieces of the Eiffel Tower in New Orleans». WGNO. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ «The Blackpool Tower». History Extra. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ «The red and white Eiffel Tower of Tokyo». KLM. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Todd van Luling (19 August 2013). «The most legit Eiffel Tower replicas you didn’t know existed». Huffpost Travel. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower». Pricing the Priceless. Season 1. Episode 3. 9 May 2011. National Geographic Channel (Australia).

- ^ «Paris time by wireless». The New York Times. 22 November 1913. p. 1.

- ^ «Why it’s actually illegal to take pictures of Eiffel Tower at night». The Jakarta Post. 9 December 2017.

- ^ «Cour de cassation 3 mars 1992, Jus Luminum n°J523975» (in French). Jus Luminum. Archived from the original on 16 November 2009.

- ^ Jimmy Wales (3 July 2015). «If you want to keep sharing photos for free, read this». The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ «The Eiffel Tower image rights». Société d’Exploitation de la Tour Eiffel. 31 March 2021.

- ^ Hugh Morris (24 June 2015). «Freedom of panorama: EU proposal could mean holiday snaps breach copyright». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Nicholls, Will (14 October 2017). «Why Photos of the Eiffel Tower at Night are Illegal». PetaPixel. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Cuttle, Jade (1 July 2019). «Why Photos of the Eiffel Tower at Night are Illegal». The Culture Trip. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower: Repossessed». Fast Company. 2 February 2005. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ James Arnold (16 May 2003). «Are things looking up for the Eiffel Tower?». BBC News. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Steve Schlackman (16 November 2014). «Do night photos of the Eiffel Tower violate copyright?». Artrepreneur Art Law Journal. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Larsen, Stephanie (13 March 2017). «Is it Illegal to Take Photographs of the Eiffel Tower at Night?». Snopes. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Notions Fondamentales Du Droit D’auteur (in French). World Intellectual Property Organization. 2002. p. 277. ISBN 978-92-805-1013-3.

La représentation d’une œuvre située dans un lieu public n’est licite que lorsqu’elle est accessoire par rapport au sujet principal représenté ou traité

- ^ «Eiffel Tower, Paris — SkyscraperPage.com». skyscraperpage.com.

- ^ «Eiffel Tower grows six metres after new antenna attached». reuters.com. 15 March 2022.

- ^ Chrysler (14 June 2004). «Chrysler Building – Piercing the Sky». CBS Forum. CBS Team. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

Bibliography

- Chanson, Hubert (2009). «Hydraulic engineering legends Listed on the Eiffel Tower». In Jerry R. Rogers (ed.). Great Rivers History: Proceedings and Invited Papers for the EWRI Congress and Great Rivers History Symposium. American Society of Civil Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7844-1032-5.

- Frémy, Dominique (1989). Quid de la tour Eiffel. R. Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-06488-7.

- The Engineer: The Paris Exhibition. Vol. XLVII. London: Office for Advertisements and Publication. 3 May 1889.

- Harriss, Joseph (1975). The Eiffel Tower: Symbol of an Age. London: Paul Elek. ISBN 0236400363.

- Harvie, David I. (2006). Eiffel: The Genius Who Reinvented Himself. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-3309-7.

- Jonnes, Jill (2009). Eiffel’s Tower: The Thrilling Story Behind Paris’s Beloved Monument …. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-05251-8.

- Loyrette, Henri (1985). Eiffel, un Ingenieur et Son Oeuvre. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-0631-7.

- Musée d’Orsay (1989). 1889: la Tour Eiffel et l’Exposition Universelle. Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Ministère de la Culture, de la Communication, des Grands Travaux et du Bicentenaire. ISBN 978-2-7118-2244-7.

- Vogel, Robert M. (1961). «Elevator Systems of the Eiffel Tower, 1889». United States National Museum Bulletin. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. 228: 20–21.

- Watson, William (1892). Paris Universal Exposition: Civil Engineering, Public Works, and Architecture. Washington, D.C.: Government Publishing Office.

External links

- Official website

- Eiffel Tower at Structurae

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Washington Monument |

World’s tallest structure 1889–1931 312 m (1,024 ft)[1] |

Succeeded by

Chrysler Building |

| World’s tallest tower 1889–1956 |

Succeeded by

KCTV Broadcast Tower |

|

| Preceded by

KCTV Broadcast Tower |

World’s tallest tower 1957–1958 |

Succeeded by

Tokyo Tower |

- ^ «Official website–figures». 30 October 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

| The Eiffel Tower | |

|---|---|

|

La tour Eiffel |

|

Seen from the Champ de Mars |

|

|

|

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1889 to 1930[I] | |

| General information | |

| Type | Observation tower Broadcasting tower |

| Location | 7th arrondissement, Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48°51′29.6″N 2°17′40.2″E / 48.858222°N 2.294500°ECoordinates: 48°51′29.6″N 2°17′40.2″E / 48.858222°N 2.294500°E |

| Construction started | 28 January 1887; 135 years ago |

| Completed | 15 March 1889; 133 years ago |

| Opening | 31 March 1889; 133 years ago |

| Owner | City of Paris, France |

| Management | Société d’Exploitation de la Tour Eiffel (SETE) |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 300 m (984 ft)[1] |

| Tip | 330 m (1,083 ft) |

| Top floor | 276 m (906 ft)[1] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3[2] |

| Lifts/elevators | 8[2] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Stephen Sauvestre |

| Structural engineer | Maurice Koechlin Émile Nouguier |

| Main contractor | Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel |

| Website | |

| toureiffel.paris/en | |

| References | |

| I. ^ «Eiffel Tower». Emporis. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. |

The Eiffel Tower ( EYE-fəl; French: tour Eiffel [tuʁ‿ɛfɛl] (listen)) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed «La dame de fer» (French for «Iron Lady»), it was constructed from 1887 to 1889 as the centerpiece of the 1889 World’s Fair. Although initially criticised by some of France’s leading artists and intellectuals for its design, it has since become a global cultural icon of France and one of the most recognisable structures in the world.[3] The Eiffel Tower is the most visited monument with an entrance fee in the world: 6.91 million people ascended it in 2015. It was designated a monument historique in 1964, and was named part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site («Paris, Banks of the Seine») in 1991.[4]

The tower is 330 metres (1,083 ft) tall,[5] about the same height as an 81-storey building, and the tallest structure in Paris. Its base is square, measuring 125 metres (410 ft) on each side. During its construction, the Eiffel Tower surpassed the Washington Monument to become the tallest human-made structure in the world, a title it held for 41 years until the Chrysler Building in New York City was finished in 1930. It was the first structure in the world to surpass both the 200-metre and 300-metre mark in height. Due to the addition of a broadcasting aerial at the top of the tower in 1957, it is now taller than the Chrysler Building by 5.2 metres (17 ft). Excluding transmitters, the Eiffel Tower is the second tallest free-standing structure in France after the Millau Viaduct.

The tower has three levels for visitors, with restaurants on the first and second levels. The top level’s upper platform is 276 m (906 ft) above the ground – the highest observation deck accessible to the public in the European Union. Tickets can be purchased to ascend by stairs or lift to the first and second levels. The climb from ground level to the first level is over 300 steps, as is the climb from the first level to the second, making the entire ascent a 600 step climb. Although there is a staircase to the top level, it is usually accessible only by lift.

History

Origin

The design of the Eiffel Tower is attributed to Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, two senior engineers working for the Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel. It was envisioned after discussion about a suitable centerpiece for the proposed 1889 Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair to celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution. Eiffel openly acknowledged that inspiration for a tower came from the Latting Observatory built in New York City in 1853.[6] In May 1884, working at home, Koechlin made a sketch of their idea, described by him as «a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top, joined together by metal trusses at regular intervals».[7] Eiffel initially showed little enthusiasm, but he did approve further study, and the two engineers then asked Stephen Sauvestre, the head of the company’s architectural department, to contribute to the design. Sauvestre added decorative arches to the base of the tower, a glass pavilion to the first level, and other embellishments.

The new version gained Eiffel’s support: he bought the rights to the patent on the design which Koechlin, Nougier, and Sauvestre had taken out, and the design was put on display at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in the autumn of 1884 under the company name. On 30 March 1885, Eiffel presented his plans to the Société des Ingénieurs Civils; after discussing the technical problems and emphasising the practical uses of the tower, he finished his talk by saying the tower would symbolise

[n]ot only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France’s gratitude.[8]

Little progress was made until 1886, when Jules Grévy was re-elected as president of France and Édouard Lockroy was appointed as minister for trade. A budget for the exposition was passed and, on 1 May, Lockroy announced an alteration to the terms of the open competition being held for a centrepiece to the exposition, which effectively made the selection of Eiffel’s design a foregone conclusion, as entries had to include a study for a 300 m (980 ft) four-sided metal tower on the Champ de Mars.[8] (A 300-metre tower was then considered a herculean engineering effort). On 12 May, a commission was set up to examine Eiffel’s scheme and its rivals, which, a month later, decided that all the proposals except Eiffel’s were either impractical or lacking in details.

After some debate about the exact location of the tower, a contract was signed on 8 January 1887. Eiffel signed it acting in his own capacity rather than as the representative of his company, the contract granting him 1.5 million francs toward the construction costs: less than a quarter of the estimated 6.5 million francs. Eiffel was to receive all income from the commercial exploitation of the tower during the exhibition and for the next 20 years. He later established a separate company to manage the tower, putting up half the necessary capital himself.[9]

The Crédit Industriel et Commercial (C.I.C.) helped finance the construction of the Eiffel Tower. According to a New York Times investigation into France’s colonial legacy in Haiti, at the time of the tower’s construction, the bank was acquiring funds from predatory loans related to the Haiti indemnity controversy – a debt forced upon Haiti by France to pay for slaves lost following the Haitian Revolution – and transferring Haiti’s wealth into France. The Times reported that the C.I.C. benefited from a loan that required the Haitian Government to pay the bank and its partner nearly half of all taxes the Haitian government collected on exports, writing that by «effectively choking off the nation’s primary source of income», the C.I.C. «left a crippling legacy of financial extraction and dashed hopes — even by the standards of a nation with a long history of both.»[10]

Artists’ protest