- Î íàñ

- Êóïèòü òóð

- ×åì çàíÿòüñÿ

- Êóäà îòïðàâèòüñÿ

Ôèëëèïèíû, Ôèëèïèíû èëè Ôèëèïèííû: êàê ïðàâèëüíî?

Ôèëèïïèíû äàëåêàÿ ýêçîòè÷åñêàÿ ñòðàíà â Òèõîì îêåàíå è íå êàæäûé â ñîñòîÿíèè ñðàçó âåðíî íàïèñàòü åå íàçâàíèå. Äîâîëüíî ÷àñòî ìîæíî âñòðåòèòü çàãîëîâêè: «Òóðû íà Ôèëëèïèíû» èëè «Îòäûõ íà Ôèëèïèíàõ» è äàæå

«Îòåëè Ôèëèïèíí».

Êàêîé æå èç âàðèàíòîâ: Ôèëëèïèíû, Ôèëèïèíû èëè Ôèëèïèííû âåðåí? È êàê çàïîìíèòü ïðàâèëüíîå íàïèñàíèå?

Èñòîðè÷åñêè íà òåððèòîðèþ ñòðàíû äîëãî ïðåòåíäîâàëè Èñïàíèÿ è Ïîðòóãàëèÿ. Èñïàíöû âçÿëè âåðõ è, ïîýòîìó, íàçâàíèå ñâîå Ôèëèïïèíû ïîëó÷èëè â ÷åñòü èñïàíñêîãî êîðîëÿ (òîãäà åùå ïðèíöà, ïðåñòîëîíàñëåäíèêà) Ôèëèïïà II. Íó à èìÿ Ôèëèïï ïèøåòñÿ ñ äâóìÿ «ï», òàê êàê èìååò ãðå÷åñêèå êîðíè: «ôèë» îò «φιλεω» îçíà÷àåò «ëþáèòü», «èïï» («ιππ») âñå, ÷òî ñâÿçàíî ñ êîíÿìè (ñð. èïïîäðîì). Ïîëó÷àåòñÿ, ÷òî Ôèëèïï ëþáèòåëü ëîøàäåé, à Ôèëèïïèíû çåìëÿ Ôèëèïïà. Ïî-àíãëèéñêè ðåñïóáëèêà íàçûâàåòñÿ «Republic of the Philippines», òîæå ñ äâîéíîé «ï».

Ó íàçâàíèÿ Ôèëèïïèí åñòü êîíêðåòíûé àâòîð è äàòà ïîÿâëåíèÿ. Èñïàíåö Ðóè Ëîïåñ äå Âèëüÿëîáîñ (Ruy López de Villalobos) â õîäå ýêñïåäèöèè 1543 ã. íàçâàë îñòðîâà Ñàìàð è Ëåéòå «Las Islas Filipinas» â ÷åñòü áóäóùåãî ìîíàðõà.

Áûëè è íå ïðèæèâøèåñÿ íàçâàíèÿ: Nueva Castilla (Íîâàÿ Êàñòèëèÿ), Islas del Poniente (Çàïàäíûå îñòðîâà). Ïåðâîîòêðûâàòåëü Ôåðíàí Ìàãåëëàí íàçâàë àðõèïåëàã Îñòðîâàìè Ñâÿòîãî Ëàçàðÿ (Islas de San Lázaro) â ÷åñòü ñâÿòîãî, â äåíü ïàìÿòè êîòîðîãî ýêñïåäèöèÿ äîñòèãëà îñòðîâîâ.

Îôèöèàëüíî ãîñóäàðñòâî Ôèëèïïèíû (ïî-òàãàëüñêè Pilipinas) íàçûâàåòñÿ Ðåñïóáëèêà Ôèëèïïèíû (Republika ng Pilipinas).

Îñòðîâà, çàíèìàåìûå ñòðàíîé, èìåíóþòñÿ Ôèëèïïèíñêèìè îñòðîâàìè èëè Ôèëèïïèíñêèì àðõèïåëàãîì.

Ïîýòè÷åñêè Ôèëèïïèíû ìîãóò íàçâàòü ñòðàíîé ñåìè òûñÿ÷ âîçìîæíîñòåé (èëè ñòðàíîé ñåìè òûñÿ÷ îñòðîâîâ). Òàêæå ìîæíî óñëûøàòü èìÿ îñòðîâà ñàìïàãèòû (ñàìïàãèòà öâåòîê, âèä æàñìèíà, íàöèîíàëüíûé ñèìâîë Ôèëèïïèí). Åùå îäíî óñòîé÷èâîå íàçâàíèå «æåì÷óæèíà þæíûõ ìîðåé» (àíãë. «the Pearl of the Orient Seas»).

íàñòîÿùåå âðåìÿ ìîæíî óñëûøàòü ðåäêî, íî äî 2-é Ìèðîâîé âîéíû Ôèëèïïèíû íàçûâàëèñü àìåðèêàíöàìè «íåïîòîïëÿåìûì àâèàíîñöåì». Àìåðèêàíñêàÿ êîëîíèÿ äåéñòâèòåëüíî ðàññìàòðèâàëàñü (âîçìîæíî è ïðîäîëæàåò ðàññìàòðèâàòüñÿ) â êà÷åñòâå ïëàöäàðìà, ïîçâîëÿþùåãî êîíòðîëèðîâàòü àçèàòñêî-òèõîîêåàíñêèé ðåãèîí. Ñïåñü ñ ÿíêè ñóìåëà ñáèòü ßïîíèÿ, íå ïîòîïèâ, íî ìîëíèåíîñíî çàõâàòèâ «àâèàíîñåö».

Èíîãäà âñòðå÷àåòñÿ íàïèñàíèå íàçâàíèÿ ñòðàíû â íåâåðíîé ðàñêëàäêå: Abkbggbys, Abkkbgbys, Abkbgbys, Abkbgbyys

Åùå ñòî́èò âñïîìíèòü îá óïîòðåáëåíèè ïðåäëîãîâ «â» è «íà» ñ ãåîãðàôè÷åñêèìè íàçâàíèÿìè. Ôèëèïïèíû îñòðîâíîå ãîñóäàðñòâî, çàíèìàþùåå áîëüøîé àðõèïåëàã, è ïðåäëîãè äîëæíû óòî÷íÿòü ïðîñòðàíñòâåííûå ïîíÿòèÿ. Ìîæíî ïðèáûòü «íà Ôèëèïïèíû» (êàê «íà Êóáó», «íà Êàì÷àòêó», «íà Óðàë»), íî íå «â Ôèëèïïèíû». Íî ïðè ýòîì åäèíñòâåííî âåðíûì áóäåò âàðèàíò «â Ðåñïóáëèêó Ôèëèïïèíû», èáî ñëîâî «ðåñïóáëèêà» îäíîçíà÷íî óêàçûâàåò íà ãîñóäàðñòâî, à íå íà îñòðîâà, î ïðåäëîãå «íà» â ñî÷åòàíèè ñ Ðåñïóáëèêîé Ôèëèïïèíû íóæíî çàáûòü.

Åùå ðàç: ïðèëåòåë íà Ôèëèïïèíû, íî â Ðåñïóáëèêó Ôèëèïïèíû.

Êàê çàáðîíèðîâàòü òóð íà Ôèëèïïèíû

Óçíàòü äîïîëíèòåëüíóþ èíôîðìàöèþ è çàáðîíèðîâàòü ñâîé îòäûõ íà ôèëèïïèíñêèõ êóðîðòàõ âû ìîæåòå, îáðàòèâøèñü â îôèñ ìîñêîâñêîãî òóðîïåðàòîðà ïî Ôèëèïïèíàì ÀÑ-òðåâåë.

Çàäàéòå âîïðîñ âàøåìó ýêñïåðòó ïî Ôèëèïïèíàì

филиппи́нский

филиппи́нский (от Филиппи́ны)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова учуянный (прилагательное):

Синонимы к слову «филиппинский»

Предложения со словом «филиппинский»

- На видео филиппинский рок-герой со своей группой The Zoo исполнял песни американской группы Journey.

- Наша компания вышла на филиппинский рынок ещё в 1935 году – за счёт поглощения местного бренда.

- Официант как-то странно пожал плечами и ушёл, а я подумала: «Наверное, это экзотический филиппинский ресторан, где едят руками».

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «филиппинский»

- Филиппинский архипелаг, как parvenu какой-нибудь, еще не имеет права на генеалогическое дерево.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Как написать слово «филиппинский» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «филиппинский»?

фи́ли́ппи́нски́й

Правильное написание — филиппинский, ударение падает на букву: и, безударными гласными являются: и, и, и.

Выделим согласные буквы — филиппинский, к согласным относятся: ф, л, п, н, с, к, й, звонкие согласные: л, н, й, глухие согласные: ф, п, с, к.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 12,

- слогов — 4,

- гласных — 4,

- согласных — 8.

Формы слова: филиппи́нский (от Филиппи́ны).

Правильное написание слова Филиппины:

Филиппины

Крутая NFT игра. Играй и зарабатывай!

Количество букв в слове: 9

Слово состоит из букв:

Ф, И, Л, И, П, П, И, Н, Ы

Правильный транслит слова: Фilippini

Написание с не правильной раскладкой клавиатуры: Фbkbggbys

Тест на правописание

Синонимы слова Филиппины

- Страна семи тысяч островов

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — Филиппины

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — ЖАЛЮЗИ?

Слово состоит из букв:

Ф,

И,

Л,

И,

П,

П,

И,

Н,

Ы,

Похожие слова:

филиппе

филиппика

филиппики

филиппинец

филиппинский

филиппо

Филиппов

Филиппова

филиппови

Филиппович

Рифма к слову Филиппины

спины, причины, величины, потемкины, перекладины, магазины, развалины, березины, кончины, дисциплины, дружины, глубины, чины, середины, екатерины, тишины, вины, фрейлины, лопатины, половины, казакины, хворостины, глины, лины, ангины, длины, истины, кузины, машины, мины, плотины, перины, картины, вотчины, ширины, десятины, дубины, ужины, лучины, рытвины, именины, баранины, родины, мужчины, дядюшкины, водомоины, воины, илагины, говядины, карагины, вызваны, наказаны, развязаны, названы, деланы, аны, разосланы, стаканы, образованы, переданы, дианы, прорваны, курганы, даны, партизаны, сделаны, званы, нарисованы, связаны, застланы, обвязаны, отрезаны, поданы, взволнованы, обязаны, завязаны, розданы, посланы, облагодетельствованы, диваны, потребованы, преданы, высланы, балаганы, призваны, обдерганы, изуродованы, тараканы, планы, основаны, чемоданы, отосланы, сказаны, привязаны, барабаны, заделаны, разрезаны, преобразованы, отданы, сосланы

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

Разбор слова «филиппины»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «филиппины» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «филиппины» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «филиппины».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «филиппины» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «филиппины»

- 3 Синонимы слова «филиппины»

- 4 Значение слова «филиппины»

- 5 Склонение слова «филиппины» по подежам

- 6 Как правильно пишется слово «филиппины»

- 7 Ассоциации к слову «филиппины»

Слоги в слове «филиппины» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 4

По слогам: фи-ли-ппи-ны

По правилам школьной программы слово «филиппины» можно поделить на слоги разными способами. Допускается вариативность, то есть все варианты правильные. Например, такой:

фи-лип-пи-ны

По программе института слоги выделяются на основе восходящей звучности:

фи-ли-ппи-ны

Ниже перечислены виды слогов и объяснено деление с учётом программы института и школ с углублённым изучением русского языка.

сдвоенные согласные пп не разбиваются при выделении слогов и парой отходят к следующему слогу

Как перенести слово «филиппины»

фи—липпины

филип—пины

филиппи—ны

Синонимы слова «филиппины»

1. страна

2. страна семи тысяч островов

Значение слова «филиппины»

1. государство в Юго-Восточной Азии (Викисловарь)

Склонение слова «филиппины» по подежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Единственное числоЕд.ч. | Множественное числоМн.ч. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Именительный | что? | Не имеет единственного числа | Филиппины |

| Родительный | чего? | Филиппин | |

| Дательный | чему? | Филиппинам | |

| Винительный | что? | Филиппины | |

| Творительный | чем? | Филиппинами | |

| Предложный | о чём? | Филиппинах |

Как правильно пишется слово «филиппины»

Правописание слова «филиппины»

Орфография слова «филиппины»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «филиппины» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «филиппины»

-

Индонезия

-

Таиланд

-

Гвинея

-

Сингапур

-

Индия

-

Вьетнам

-

Пакистан

-

Зеландия

-

Корея

-

Гонконг

-

Венесуэла

-

Куба

-

Австралия

-

Чили

-

Япония

-

Панама

-

Китай

-

Азия

-

Мексика

-

Перу

-

Марокко

-

Исландия

-

Колумбия

-

Люксембург

-

Аргентина

-

Архипелаг

-

Бразилия

-

Таджикистан

-

Иран

-

Монголия

-

Узбекистан

-

Конго

-

Тунис

-

Аравия

-

Словакия

-

Хорватия

-

Нидерланды

-

Бельгия

-

Кнр

-

Канада

-

Чехия

-

Норвегия

-

Ирак

-

Мальта

-

Куб

-

Албания

-

Эстония

-

Франция

-

Португалия

-

Ареал

-

Епархия

-

Афганистан

-

Ямайка

-

Сирия

-

Румыния

-

Индий

-

Испания

-

Босния

-

Турция

-

Швеция

-

Кипр

-

Самар

-

Сербия

-

Шанхай

-

Финляндия

-

Греция

-

Африка

-

Венгрия

-

Германия

-

Казахстан

-

Швейцария

-

Мехико

-

Остров

-

Великобритания

-

Алжир

-

Японец

-

Чехословакия

-

Австрия

-

Токио

-

Вторжение

-

Латвия

-

Полуостров

-

Победительница

-

Македония

-

Ливия

-

Авианосец

-

Тихоокеанский

-

Саудовский

-

Азиатский

-

Карибский

-

Весовой

-

Голландский

-

Тропический

-

Сборный

-

Юго-восточный

-

Японский

-

Испанский

-

Южный

-

Католический

-

Оккупировать

Содержание

- 1 Русский

- 1.1 Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

- 1.2 Произношение

- 1.3 Семантические свойства

- 1.3.1 Значение

- 1.3.2 Синонимы

- 1.3.3 Антонимы

- 1.3.4 Гиперонимы

- 1.3.5 Гипонимы

- 1.4 Родственные слова

- 1.5 Этимология

- 1.6 Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- 1.7 Перевод

- 1.8 Библиография

Русский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | — | Филиппи́ны |

| Р. | — | Филиппи́н |

| Д. | — | Филиппи́нам |

| В. | — | Филиппи́ны |

| Тв. | — | Филиппи́нами |

| Пр. | — | Филиппи́нах |

Фи—лип—пи́—ны

Существительное, неодушевлённое, женский род, 1-е склонение (тип склонения мн. <ж 1a> по классификации А. А. Зализняка); формы ед. ч. не используются.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: -Филиппин-; окончание: -ы.

Произношение

- МФА: [fʲɪlʲɪˈpʲinɨ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- государство в Юго-Восточной Азии ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

- —

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- страна, государство

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

|

Библиография

Coordinates: 13°N 122°E / 13°N 122°E

|

Republic of the Philippines Republika ng Pilipinas (Filipino) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Motto: Maka-Diyos, Maka-tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa[1] «For God, People, Nature, and Country» |

|

| Anthem: Lupang Hinirang «Chosen Land» |

|

| Great Seal

|

|

|

|

|

| Capital | Manila (de jure) 14°35′N 120°58′E / 14.583°N 120.967°E Metro Manila[a] (de facto) |

| Largest city | Quezon City 14°38′N 121°02′E / 14.633°N 121.033°E |

| Official languages |

|

| Recognized regional languages |

19 languages

|

|

National sign language |

Filipino Sign Language |

|

Other recognized languages[b] |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2010[5]) |

|

| Religion

(2015)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Filipino (masculine and neutral) Filipina (feminine) Pinoy Philippine |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

|

• President |

Bongbong Marcos |

|

• Vice President |

Sara Duterte |

|

• Senate President |

Migz Zubiri |

|

• House Speaker |

Martin Romualdez |

|

• Chief Justice |

Alexander Gesmundo |

| Legislature | Congress |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

House of Representatives |

| Independence

from the United States |

|

|

• Independence from the Spanish Empire declared |

June 12, 1898 |

|

• Spanish cession to the United States |

December 10, 1898 |

|

• Commonwealth status with the United States |

November 15, 1935 |

|

• Independence from the United States granted |

July 4, 1946 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) (72nd) |

|

• Water (%) |

0.61[6] (inland waters) |

|

• Total land area |

298,170 km2 (115,120 sq mi) |

| Population | |

|

• 2020 census |

109,035,343[7] |

|

• Density |

336/km2 (870.2/sq mi) (47th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 116th |

| Currency | Philippine peso (₱) (PHP) |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (PST) |

| Date format | mm/dd/yyyy |

| Driving side | right[c] |

| Calling code | +63 |

| ISO 3166 code | PH |

| Internet TLD | .ph |

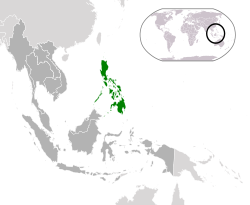

The Philippines (; Filipino: Pilipinas),[13] officially the Republic of the Philippines (Filipino: Republika ng Pilipinas),[d] is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. It is situated in the western Pacific Ocean and consists of around 7,641 islands that are broadly categorized under three main geographical divisions from north to south: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The Philippines is bounded by the South China Sea to the west, the Philippine Sea to the east, and the Celebes Sea to the southwest. It shares maritime borders with Taiwan to the north, Japan to the northeast, Palau to the east and southeast, Indonesia to the south, Malaysia to the southwest, Vietnam to the west, and China to the northwest. The Philippines covers an area of 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) and, as of 2021, it had a population of around 109 million people, making it the world’s thirteenth-most populous country. The Philippines has diverse ethnicities and cultures throughout its islands. Manila is the country’s capital, while the largest city is Quezon City; both lie within the urban area of Metro Manila.

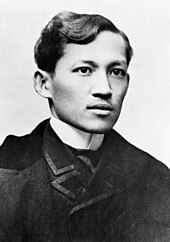

Negritos, some of the archipelago’s earliest inhabitants, were followed by successive waves of Austronesian peoples. Adoption of animism, Hinduism and Islam established island-kingdoms called Kedatuan, Rajahnates, and Sultanates. The arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer leading a fleet for Spain, marked the beginning of Spanish colonization. In 1543, Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos named the archipelago Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip II of Spain. Spanish settlement through Mexico, beginning in 1565, led to the Philippines becoming ruled by the Spanish Empire for more than 300 years. During this time, Catholicism became the dominant religion, and Manila became the western hub of trans-Pacific trade. In 1896, the Philippine Revolution began, which then became entwined with the 1898 Spanish–American War. Spain ceded the territory to the United States, while Filipino revolutionaries declared the First Philippine Republic. The ensuing Philippine–American War ended with the United States establishing control over the territory, which they maintained until the Japanese invasion of the islands during World War II. Following liberation, the Philippines became independent in 1946. Since then, the unitary sovereign state has often had a tumultuous experience with democracy, which included the overthrow of a decades-long dictatorship by a nonviolent revolution.

The Philippines is an emerging market and a newly industrialized country whose economy is transitioning from being agriculture centered to services and manufacturing centered. It is a founding member of the United Nations, World Trade Organization, ASEAN, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and the East Asia Summit. The location of the Philippines as an island country on the Pacific Ring of Fire that is close to the equator makes it prone to earthquakes and typhoons. The country has a variety of natural resources and is home to a globally significant level of biodiversity.

Etymology

Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos, during his expedition in 1542, named the islands of Leyte and Samar «Felipinas» after Philip II of Spain, then the Prince of Asturias. Eventually the name «Las Islas Filipinas» would be used to cover the archipelago’s Spanish possessions.[14] Before Spanish rule was established, other names such as Islas del Poniente (Islands of the West) and Ferdinand Magellan’s name for the islands, San Lázaro, were also used by the Spanish to refer to islands in the region.[15][16][17][18]

During the Philippine Revolution, the Malolos Congress proclaimed the establishment of the República Filipina or the Philippine Republic. From the period of the Spanish–American War (1898) and the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) until the Commonwealth period (1935–1946), American colonial authorities referred to the country as The Philippine Islands, a translation of the Spanish name.[19] The United States began the process of changing the reference to the country from The Philippine Islands to The Philippines, specifically when it was mentioned in the Philippine Autonomy Act or the Jones Law.[20] The full official title, Republic of the Philippines, was included in the 1935 constitution as the name of the future independent state,[21] it is also mentioned in all succeeding constitutional revisions.[22][23]

History

Prehistory (pre–900)

There is evidence of early hominins living in what is now the Philippines as early as 709,000 years ago.[24] A small number of bones from Callao Cave potentially represent an otherwise unknown species, Homo luzonensis, that lived around 50,000 to 67,000 years ago.[25][26] The oldest modern human remains found on the islands are from the Tabon Caves of Palawan, U/Th-dated to 47,000 ± 11–10,000 years ago.[27] The Tabon Man is presumably a Negrito, who were among the archipelago’s earliest inhabitants, descendants of the first human migrations out of Africa via the coastal route along southern Asia to the now sunken landmasses of Sundaland and Sahul.[28]

The first Austronesians reached the Philippines from Taiwan at around 2200 BC, settling the Batanes Islands and northern Luzon. From there, they rapidly spread southwards to the rest of the islands of the Philippines and Southeast Asia.[29][30] This population assimilated with the existing Negritos resulting in the modern Filipino ethnic groups which display various ratios of genetic admixture between Austronesian and Negrito groups.[31] Genetic signatures also indicate the possibility of migration of Austroasiatic, Papuan, and South Asian people.[32] Jade artifacts have been found dated to 2000 BC,[33][34] with the lingling-o jade items crafted in Luzon made using raw materials originating from Taiwan.[35] By 1000 BC, the inhabitants of the archipelago had developed into four kinds of social groups: hunter-gatherer tribes, warrior societies, highland plutocracies, and port principalities.[36]

Early states (900–1565)

The earliest known surviving written record found in the Philippines is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription.[37] By the 14th century, several the large coastal settlements had emerged as trading centers and became the focal point of societal changes.[38] Some polities had exchanges with other states across Asia.[39][40] Trade with China is believed to have begun during the Tang dynasty, and grew more extensive during the Song dynasty,[41] and by the second millennium some polities participated in the tributary system of China.[42][39] Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices, began to spread within the Philippines during the 10th century, likely via the Hindu Majapahit Empire.[43][38][44] By the 15th century, Islam was established in the Sulu Archipelago and spread from there.[45]

Polities founded in the Philippines from the 10th–16th centuries include Maynila,[46] Tondo, Namayan, Pangasinan, Cebu, Butuan, Maguindanao, Lanao, Sulu, and Ma-i.[47] The early polities were typically made up of three-tier social structures: a nobility class, a class of «freemen», and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen.[38][39] Among the nobility were leaders called «Datus», responsible for ruling autonomous groups called «barangay» or «dulohan».[38] When these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement[38] or a geographically looser alliance,[39] the more esteemed among them would be recognized as a «paramount datu»,[38][36] rajah, or sultan[48] which headed the community state.[49] Warfare developed and escalated during the 14th to 16th centuries,[50] and throughout these periods population density is thought to have been low,[51] which was also caused by the frequency of typhoons and the Philippines’ location on the Pacific Ring of Fire.[52] In 1521, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the area, claimed the islands for Spain and was then killed by Lapulapu’s fighters at the Battle of Mactan.[53]

Spanish and American Colonial rule (1565–1946)

Colonization began when Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi arrived from Mexico in 1565.[54][55]: 20–23 The Spanish forces brought by Legazpi’s five ships were a mix of Spaniards and Novohispanics (Mexicans) from New Spain (modern Mexico).[56][57][58][59][60]: 97–98 [61][62] Many Filipinos were brought back to New Spain as slaves and forced crew.[63] In 1571, Spanish Manila became the capital of the Spanish East Indies,[64] which encompassed Spanish territories in Asia and the Pacific.[65][66] The Spanish successfully invaded the different local states by employing the principle of divide and conquer,[67] bringing most of what is now the Philippines into a single unified administration.[68][69] Disparate barangays were deliberately consolidated into towns, where Catholic missionaries were more easily able to convert the inhabitants to Christianity.[60]: 53, 68 [70] From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Mexico City-based Viceroyalty of New Spain, and later administered from Madrid following the Mexican War of Independence.[71] Manila was the western hub of the trans-Pacific trade.[72] Manila galleons were constructed in Bicol and Cavite.[73][74]

During its rule, Spain quelled various indigenous revolts,[75] as well as defending against external military challenges.[76][77][failed verification] War against the Dutch from the west, in the 17th century, together with conflict with the Muslims in the south nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.[78]

Administration of the Philippine islands was considered a drain on the economy of New Spain,[76] and there were debates to abandon it or trade it for other territory. However, this was opposed because of economic potential, security, and the desire to continue religious conversion in the islands and the surrounding region.[79][80] The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy provided by the Spanish Crown,[76] which averaged 250,000 pesos[81] and was usually paid through the provision of 75 tons of silver bullion being sent from the Americas.[82] British forces occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764 during the Seven Years’ War, with Spanish rule restored through the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[55]: 81–83 The Spanish considered their war with the Muslims in Southeast Asia an extension of the Reconquista.[83] The Spanish–Moro conflict lasted for several hundred years. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Spain conquered portions of Mindanao and Jolo,[84] and the Moro Muslims in the Sultanate of Sulu formally recognized Spanish sovereignty.[85][86]

In the 19th century, Philippine ports opened to world trade, and shifts started occurring within Filipino society.[87][88] Shifts in social identity occurred, with the term Filipino changing from referring to Spaniards born in the Philippines to a term encompassing all people in the archipelago.[89][90]

Revolutionary sentiments were stoked in 1872 after three activist Catholic priests were executed on weak pretences.[91][92][93] This would inspire a propaganda movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, and Mariano Ponce, lobbying for political reforms in the Philippines. Rizal was executed on December 30, 1896, on charges of rebellion. This radicalized many who had previously been loyal to Spain.[94] As attempts at reform met with resistance, Andrés Bonifacio in 1892 established the militant secret society called the Katipunan, who sought independence from Spain through armed revolt.[95]

The Katipunan started the Philippine Revolution in 1896.[96] Internal disputes led to an election in which Bonifacio lost his position and Emilio Aguinaldo was elected as the new leader of the revolution.[97]: 145–147 In 1897, the Pact of Biak-na-Bato brought about the exile of the revolutionary leadership to Hong Kong. In 1898, the Spanish–American War began and reached the Philippines. Aguinaldo returned, resumed the revolution, and declared independence from Spain on June 12, 1898.[60]: 112–113 The First Philippine Republic was established on January 21, 1899.[98]

The islands had been ceded by Spain to the United States along with Puerto Rico and Guam as a result of the latter’s victory in the Spanish–American War in 1898.[99][100] As it became increasingly clear the United States would not recognize the First Philippine Republic, the Philippine–American War broke out.[101] The war resulted in the deaths of 250,000 to 1 million civilians, mostly because of famine and disease.[102] Many Filipinos were also moved by the Americans to concentration camps, where thousands died.[103][104] After the defeat of the First Philippine Republic in 1902, an American civilian government was established through the Philippine Organic Act.[105] American forces continued to secure and extend their control over the islands, suppressing an attempted extension of the Philippine Republic,[97]: 200–202 [106] securing the Sultanate of Sulu,[107] and establishing control over interior mountainous areas that had resisted Spanish conquest.[108]

Cultural developments strengthened the continuing development of a national identity,[109][110] and Tagalog began to take precedence over other local languages.[60]: 121 Governmental functions were gradually devolved to Filipinos under the Taft Commission[111] and in 1935 the Philippines was granted Commonwealth status with Manuel Quezon as president and Sergio Osmeña as vice president.[112] Quezon’s priorities were defence, social justice, inequality and economic diversification, and national character.[111] Tagalog was designated the national language,[113] women’s suffrage was introduced,[114] and land reform mooted.[115][116]

During World War II the Japanese Empire invaded,[117] and the Second Philippine Republic, under Jose P. Laurel, was established as a puppet state.[118][119] From 1942 the Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by large-scale underground guerrilla activity.[120][121][122] Atrocities and war crimes were committed during the war, including the Bataan Death March and the Manila massacre.[123][124] Allied troops defeated the Japanese in 1945. It is estimated that over one million Filipinos had died by the end of the war.[125][126] On October 11, 1945, the Philippines became one of the founding members of the United Nations.[127][128] On July 4, 1946, the Philippines was officially recognized by the United States as an independent nation through the Treaty of Manila, during the presidency of Manuel Roxas.[128][129][130]

Independence (1946–present)

Efforts to end the Hukbalahap Rebellion began during Elpidio Quirino’s term,[131] however, it was only during Ramon Magsaysay’s presidency that the movement was suppressed.[132] Magsaysay’s successor, Carlos P. Garcia, initiated the Filipino First Policy,[133] which was continued by Diosdado Macapagal, with celebration of Independence Day moved from July 4 to June 12, the date of Emilio Aguinaldo’s declaration,[134][135] and pursuit of a claim on the eastern part of North Borneo.[136][137]

In 1965, Macapagal lost the presidential election to Ferdinand Marcos. Early in his presidency, Marcos initiated numerous infrastructure projects[138] but, together with his wife Imelda, was accused of corruption and embezzling billions of dollars in public funds.[139] Nearing the end of his last constitutionally-allowed term, Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972.[140][141] This period of his rule was characterized by political repression, censorship, and human rights violations.[142]

Numerous monopolies controlled by crony businessmen were established in key industries, including logging, coconuts, bananas, telephones, and broadcasting;[143] a sugar monopoly led to a famine on the island of Negros.[143] Marcos’ heavy borrowing early in his presidency resulted in numerous economic crashes, capped by a massive recession in the early 1980s which culminated in the economy contracting by 7.3% in both 1984 and 1985.[144][143]

On August 21, 1983, Marcos’ chief rival, opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr., was assassinated on the tarmac at Manila International Airport. Marcos called a snap presidential election in 1986.[145] Marcos was proclaimed the winner, but the results were widely regarded as fraudulent.[146] The resulting protests led to the People Power Revolution,[147] which forced Marcos and his allies to flee to Hawaii, and Aquino’s widow, Corazon Aquino, was installed as president.[145][148]

The return of democracy and government reforms beginning in 1986 were hampered by national debt, government corruption, and coup attempts.[149][150] A communist insurgency[151][152] and a military conflict with Moro separatists persisted,[153] while the administration also faced a series of disasters, including the sinking of the MV Doña Paz in December 1987,[154][undue weight? – discuss] and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991.[155][156] Aquino was succeeded by Fidel V. Ramos, whose economic performance, at 3.6% growth rate,[157][158] was overshadowed by the onset of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[159][160]

Ramos’ successor, Joseph Estrada, was overthrown by the 2001 EDSA Revolution and succeeded by his vice president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, on January 20, 2001.[161] Arroyo’s 9-year administration was marked by economic growth[162] but was tainted by corruption and political scandals.[163][164] On November 23, 2009, 34 journalists and several civilians were killed in Maguindanao.[165][166]

Economic growth continued during Benigno Aquino III’s administration, which pushed for good governance and transparency.[167][168] In 2015, a shootout in Mamasapano resulted in the death of 44 members of the Philippine National Police-Special Action Force, which caused a delay in the passage of the Bangsamoro Organic Law.[169][170]

Former Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte won the 2016 presidential election, becoming the first president from Mindanao.[171][172] Duterte launched an anti-drug campaign[173][174] and an infrastructure program.[175][176] The implementation in 2018 of the Bangsamoro Organic Law led to the creation of the autonomous Bangsamoro region in Mindanao.[177][178] In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic reached the country[179][180] causing the gross domestic product to shrink by 9.5%, the country’s worst annual economic performance since records began in 1947.[181]

Marcos’ son, Bongbong Marcos, won the 2022 presidential election, together with Duterte’s daughter, Sara Duterte, as vice president.[182]

Geography

Topography of the Philippines

The Philippines is an archipelago composed of about 7,640 islands,[183][184] covering a total area, including inland bodies of water, of around 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 sq mi),[185][186] with cadastral survey data suggesting it may be larger.[187] The exclusive economic zone of the Philippines covers 2,263,816 km2 (874,064 sq mi).[188] Its 36,289 kilometers (22,549 mi) coastline gives it the world’s fifth-longest coastline.[189] It is located between 116° 40′, and 126° 34′ E longitude and 4° 40′ and 21° 10′ N latitude and is bordered by the Philippine Sea to the east,[190][191] the South China Sea to the west,[192] and the Celebes Sea to the south.[193] The island of Borneo is located a few hundred kilometers southwest,[194] and Taiwan is located directly to the north. Sulawesi is located to the southwest, and Palau is located to the east of the islands.[195][196]

The highest mountain is Mount Apo, measuring up to 2,954 meters (9,692 ft) above sea level and located on the island of Mindanao.[197] Running east of the archipelago, the Philippine Trench extends 10,540-meter (34,580 ft) down at the Emden Deep.[198][199][200] The longest river is the Cagayan River in northern Luzon, measuring about 520 kilometers (320 mi).[201] Manila Bay,[202] upon the shore of which the capital city of Manila lies, is connected to Laguna de Bay,[203] the largest lake in the Philippines, by the Pasig River.[204] The Puerto Princesa Subterranean River, which runs 8.2 kilometers (5.1 mi) underground through a karst landscape before reaching the ocean, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[205]

Situated on the western fringes of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines experiences frequent seismic and volcanic activity.[206] The Philippine region is seismically active and has been progressively constructed by plates converging towards each other in multiple directions.[207][208][209] Around five earthquakes are registered daily, though most are too weak to be felt.[210][209] The last major earthquakes were the 1976 Moro Gulf earthquake and the 1990 Luzon earthquake.[211] There are many active volcanoes such as Mayon, Mount Pinatubo, and Taal Volcano.[212] The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991 produced the second largest terrestrial eruption of the 20th century.[213] The Philippines is the world’s second-biggest geothermal energy producer behind the United States, with 18% of the country’s electricity needs being met by geothermal power.[214]

The country has valuable[215] mineral deposits as a result of its complex geologic structure and high level of seismic activity.[216][217] The Philippines is thought to have the second-largest gold deposits after South Africa, along with a large amount of copper deposits,[218] and the world’s largest deposits of palladium.[219] Other minerals include chromite, nickel, and zinc. Despite this, a lack of law enforcement, poor management, opposition because of the presence of indigenous communities, and past instances of environmental damage and disaster have resulted in these mineral resources remaining largely untapped.[218][220]

Biodiversity

The Philippines is a megadiverse country.[221][222] Eight major types of forests are distributed throughout the Philippines; dipterocarp, beach forest, pine forest, molave forest, lower montane forest, upper montane or mossy forest, mangroves, and ultrabasic forest.[223] As of 2021, the Philippines has 7 million hectares of forest cover, according to official estimates, though experts contend that the actual figure is likely much lower.[224] Deforestation, often the result of illegal logging, is an acute problem in the Philippines. Forest cover has declined from 70% of the Philippines’s total land area in 1900 to about 18.3% in 1999.[225] With an estimated 13,500 plant species in the country, 3,200 of which are unique to the islands,[226] Philippine rainforests have an array of flora,[227] including many rare types of orchids[228] and rafflesia.[229]

Around 1,100 land vertebrate species can be found in the Philippines including over 100 mammal species and 243 bird species not thought to exist elsewhere.[226][230] The Philippines has among the highest rates of discovery in the world with sixteen new species of mammals discovered in the last ten years. Because of this, the rate of endemism for the Philippines has risen and likely will continue to rise.[231] Parts of its marine waters contain the highest diversity of shorefish species in the world.[232]

Large reptiles include the Philippine crocodile[233] and saltwater crocodile.[234] The largest crocodile in captivity, known locally as Lolong, was captured in the southern island of Mindanao,[235] and died on February 10, 2013, from pneumonia and cardiac arrest.[236] The national bird, known as the Philippine eagle, has the longest body of any eagle; it generally measures 86 to 102 cm (2.82 to 3.35 ft) in length and weighs 4.7 to 8.0 kg (10.4 to 17.6 lb).[237][238] The Philippine eagle is part of the family Accipitridae and is endemic to the rainforests of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao.[239] The Philippines has the third highest number of endemic birds in the world (behind Indonesia and Australia) with 243 endemics. Notable birds include the Celestial monarch, flame-templed babbler, Red-vented cockatoo, Whiskered pitta, Sulu hornbill, Rufous hornbill, Luzon bleeding-heart and the Flame-breasted fruit dove.[230]

Philippine maritime waters produce unique and diverse marine life[240] and is an important part of the Coral Triangle ecoregion.[241][242] The total number of corals and marine fish species in this ecoregion is estimated at 500 and 2,400 respectively.[226] New records[243][244] and species discoveries continue.[245][246][247] The Tubbataha Reef in the Sulu Sea was declared a World Heritage Site in 1993.[248] Philippine waters also sustain the cultivation of fish, crustaceans, oysters, and seaweeds.[249] One species of oyster, Pinctada maxima, produces pearls that are naturally golden in color.[250] Pearls have been declared a «national gem».[251]

Climate

The Philippines has a tropical maritime climate that is usually hot and humid. There are three seasons: a hot dry season from March to May; a rainy season from June to November; and a cool dry season from December to February. The southwest monsoon lasts from May to October and the northeast monsoon from November to April. Temperatures usually range from 21 °C (70 °F) to 32 °C (90 °F). The coolest month is January; the warmest is May.[252]

The average yearly temperature is around 26.6 °C (79.9 °F). In considering temperature, location in terms of latitude and longitude is not a significant factor, and temperatures at sea level tend to be in the same range. Altitude usually has more of an impact. The average annual temperature of Baguio at an elevation of 1,500 meters (4,900 ft) above sea level is 18.3 °C (64.9 °F), making it a popular destination during hot summers.[252] Annual rainfall measures as much as 5,000 millimeters (200 in) in the mountainous east coast section but less than 1,000 millimeters (39 in) in some of the sheltered valleys.[253]

Sitting astride the typhoon belt, the islands experience 15–20 typhoons annually from July to October,[253] with around 19 typhoons[254] entering the Philippine area of responsibility in a typical year and 8 or 9 making landfall.[255][256] Historically typhoons were sometimes referred to as baguios.[257] The wettest recorded typhoon to hit the Philippines dropped 2,210 millimeters (87 in) in Baguio from July 14 to 18, 1911.[258] The Philippines is highly exposed to climate change and is among the world’s ten countries that are most vulnerable to climate change risks.[259]

Government and politics

The Philippines has a democratic government in the form of a constitutional republic with a presidential system.[260] The president functions as both head of state and head of government[261] and is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[260] The president is elected by direct election for a single six-year term.[262] The president appoints and presides over the cabinet.[263]: 213–214 The bicameral Congress is composed of the Senate, serving as the upper house, with members elected to a six-year term, and the House of Representatives, serving as the lower house, with members elected to a three-year term.[264] Philippine politics tends to be dominated by those with well-known names, such as members of political dynasties or celebrities.[265][266]

Senators are elected at-large[264] while the representatives are elected from both legislative districts and through sectoral representation.[263]: 162–163 The judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court, composed of a chief justice as its presiding officer and fourteen associate justices,[267] all of whom are appointed by the president from nominations submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council.[260]

There have been attempts to change the government to a federal, unicameral, or parliamentary government since the Ramos administration.[268] There is a significant amount of corruption in the Philippines,[269][270][271] which some historians attribute to the system of governance put in place during the Spanish colonial period.[272]

Foreign relations

As a founding and active member of the United Nations,[273] the country has been elected to the Security Council.[274] Carlos P. Romulo was a former president of the United Nations General Assembly.[275][276] The country is an active participant in peacekeeping missions, particularly in East Timor.[277][278] Over 10 million Filipinos live and work overseas.[279][280]

The Philippines is a founding and active member of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations).[281] It has hosted several summits and is an active contributor to the direction and policies of the bloc.[282][283] It is also a member of the East Asia Summit,[284] the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Group of 24, and the Non-Aligned Movement.[285][286][287] The country is also seeking to obtain observer status in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.[288][289]

The Philippines has a long relationship with the United States, covering economics, security, and people-to-people relations.[290] A Mutual Defense Treaty between the two countries was signed in 1951 and supplemented with the 1999 Visiting Forces Agreement and the 2016 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.[291] The Philippines supported American policies during the Cold War and participated in the Korean and Vietnam wars.[292][293] In 2003 the Philippines was designated a major non-NATO ally.[294] Under President Duterte, ties with the United States have weakened[295] with military purchases instead coming from China and Russia,[296][297] while Duterte states that the Philippines will no longer participate in any U.S.-led wars.[298] In 2021, it was revealed the United States would defend the Philippines including the South China Sea.[299]

The Philippines attaches great importance to its relations with China and has established significant cooperation with the country.[300][301][302][303][304][305] Japan is the biggest bilateral contributor of official development assistance to the country.[306][307][308] Although historical tensions exist because of the events of World War II, much of the animosity has faded.[309] Historical and cultural ties continue to affect relations with Spain.[310][311] Relations with Middle Eastern countries are shaped by the high number of Filipinos working in these countries,[312] and by issues related to the Muslim minority in the Philippines;[313] concerns have been raised regarding issues such as domestic abuse and war affecting[314][315] the approximately 2.5 million overseas Filipino workers in the region.[316]

The Philippines has claims in the Spratly Islands which overlap with claims by China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Vietnam. The largest of its controlled islands in Thitu Island, which contains the Philippines’s smallest village.[317][318] The Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012, where China took control of the shoal from the Philippines, led to an international arbitration case[319] which the Philippines eventually won[320] but China had rejected,[321] and has made the shoal a prominent symbol in the wider dispute.[322]

Military

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) consist of three branches: the Philippine Air Force, the Philippine Army, and the Philippine Navy.[323] The AFP is a volunteer force.[324] Civilian security is handled by the Philippine National Police under the Department of the Interior and Local Government.[325][326] As of 2018, $2.843 billion,[327] or 1.1 percent of GDP is spent on military forces.[328] As of 2021, this number has increased to $4.40 billion.[329]

In Bangsamoro, the largest separatist organizations, the Moro National Liberation Front and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, were engaging the government politically in the 2000s.[330] Other more militant groups like the Abu Sayyaf have kidnapped foreigners for ransom, particularly in the Sulu Archipelago.[332][333][334][335] Their presence decreased through successful security provided by the Philippine government.[336][337] The Communist Party of the Philippines and its military wing, the New People’s Army, have been waging guerrilla warfare against the government since the 1970s, reaching its apex in 1986, when communist guerrillas gained control of a fifth of the country’s territory before significantly dwindling militarily and politically after the return of democracy in 1986.[338][339]

Administrative divisions

The Philippines is governed as a unitary state, with the exception of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM),[340] although there have been several steps towards decentralization within the unitary framework.[341][342] A 1991 law devolved some powers to local governments.[343] The country is divided into 17 regions, 82 provinces, 146 cities, 1,488 municipalities, and 42,036 barangays.[344] Regions other than Bangsamoro serve primarily to organize the provinces of the country for administrative convenience.[345] As of 2015, Calabarzon was the most populated region while the National Capital Region (NCR) was the most densely populated.[346]

Administrative map of the Philippines

| Designation | Name | Regional center | Area[346] | Population (as of 2015)[347] |

% of Population | Population density[346] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCR | National Capital Region | Manila | 619.54 km2 (239.21 sq mi) | 12,877,253 | 12.75% | 20,785/km2 (53,830/sq mi) |

| Region I | Ilocos Region | San Fernando (La Union) | 12,964.62 km2 (5,005.67 sq mi) | 5,026,128 | 4.98% | 388/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| CAR | Cordillera Administrative Region | Baguio | 19,818.12 km2 (7,651.82 sq mi) | 1,722,006 | 1.71% | 87/km2 (230/sq mi) |

| Region II | Cagayan Valley | Tuguegarao | 29,836.88 km2 (11,520.08 sq mi) | 3,451,410 | 3.42% | 116/km2 (300/sq mi) |

| Region III | Central Luzon | San Fernando (Pampanga) | 22,014.63 km2 (8,499.90 sq mi) | 11,218,177 | 11.11% | 512/km2 (1,330/sq mi) |

| Region IV-A | Calabarzon | Calamba | 16,576.26 km2 (6,400.13 sq mi) | 14,414,774 | 14.27% | 870/km2 (2,300/sq mi) |

| Region IV-B | Mimaropa | Calapan | 29,606.25 km2 (11,431.04 sq mi) | 2,963,360 | 2.93% | 100/km2 (260/sq mi) |

| Region V | Bicol Region | Legazpi City | 18,114.47 km2 (6,994.04 sq mi) | 5,796,989 | 5.74% | 320/km2 (830/sq mi) |

| Region VI | Western Visayas | Iloilo City | 20,778.29 km2 (8,022.54 sq mi) | 7,536,383 | 7.46% | 363/km2 (940/sq mi) |

| Region VII | Central Visayas | Cebu City | 15,872.58 km2 (6,128.44 sq mi) | 7,396,898 | 7.33% | 466/km2 (1,210/sq mi) |

| Region VIII | Eastern Visayas | Tacloban | 23,234.78 km2 (8,971.00 sq mi) | 4,440,150 | 4.40% | 191/km2 (490/sq mi) |

| Region IX | Zamboanga Peninsula | Pagadian[348] | 16,904.03 km2 (6,526.68 sq mi) | 3,629,783 | 3.59% | 215/km2 (560/sq mi) |

| Region X | Northern Mindanao | Cagayan de Oro | 20,458.51 km2 (7,899.07 sq mi) | 4,689,302 | 4.64% | 229/km2 (590/sq mi) |

| Region XI | Davao Region | Davao City | 20,433.38 km2 (7,889.37 sq mi) | 4,893,318 | 4.85% | 239/km2 (620/sq mi) |

| Region XII | Soccsksargen | Koronadal | 22,610.08 km2 (8,729.80 sq mi) | 4,245,838 | 4.20% | 188/km2 (490/sq mi) |

| Region XIII | Caraga | Butuan | 21,120.56 km2 (8,154.69 sq mi) | 2,596,709 | 2.57% | 123/km2 (320/sq mi) |

| BARMM | Bangsamoro | Cotabato City | 36,826.95 km2 (14,218.96 sq mi) | 4,080,825 | 4.04% | 111/km2 (290/sq mi) |

Demographics

The Commission on Population estimated the country’s population to be 107,190,081 as of December 31, 2018, based on the latest population census of 2015 conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority.[349] The population increased from 1990 to 2008 by approximately 28 million, a 45% growth in that time frame.[350] The first official census in the Philippines was carried out in 1877 and recorded a population of 5,567,685.[351]

A third of the population resides in Metro Manila and its immediately neighboring regions.[352] The 2.34% average annual population growth rate between 1990 and 2000 decreased to an estimated 1.90% for the 2000–2010 period.[353] Government attempts to reduce population growth have been a contentious issue.[354] The population’s median age is 22.7 years with 60.9% aged from 15 to 64 years old.[6] Life expectancy at birth is 69.4 years, 73.1 years for females and 65.9 years for males.[355] Poverty incidence dropped to 18.1% in 2021[356] from 25.2% in 2012.[357]

The capital city of the Philippines is Manila and the most populous city is Quezon City, both within the single urban area of Metro Manila.[358] Metro Manila is the most populous of the 3 defined metropolitan areas in the Philippines[359] and the 5th most populous in the world.[360] Census data from 2015 showed it had a population of 12,877,253 constituting almost 13% of the national population.[361] Including suburbs in the adjacent provinces (Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, and Rizal) of Greater Manila, the population is around 23,088,000.[360] Across the country, the Philippines has a total urbanization rate of 51.2%.[361] Metro Manila’s gross regional product was estimated as of 2021 to be ₱6.158 trillion (at constant 2020 prices).[362]

Ethnic groups

Dominant ethnic groups by province

There is substantial ethnic diversity with the Philippines, a product of the seas and mountain ranges dividing the archipelago along with significant foreign influences.[261] According to the 2010 census, 24.4% of Filipinos are Tagalog, 11.4% Visayans/Bisaya (excluding Cebuano, Hiligaynon and Waray), 9.9% Cebuano, 8.8% Ilocano, 8.4% Hiligaynon, 6.8% Bikol, 4% Waray, and 26.2% are «others»,[6][363] which can be broken down further to yield more distinct nontribal groups like the Moro, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Ibanag, and Ivatan.[364] There are also indigenous peoples[365] like the Igorot, the Lumad, the Mangyan, and the tribes of Palawan.[366]

Negritos are considered among the earliest inhabitants of the islands.[367] These minority aboriginal settlers are an Australoid group and are left over from the first human migration out of Africa to Australia and were likely displaced by later waves of migration.[368] At least some Negritos in the Philippines have Denisovan admixture in their genomes.[369][370] Ethnic Filipinos generally belong to several Southeast Asian ethnic groups classified linguistically as part of the Austronesian or Malayo-Polynesian speaking people.[365] There is some uncertainty over the origin of this Austronesian speaking population. It is likely that ancestors related to Taiwanese aborigines brought their language and mixed with existing populations in the area.[371][372] The Lumad and Sama-Bajau ethnic groups have ancestral affinity with the Austroasiatic Mlabri and Htin peoples of mainland Southeast Asia. There was a westward expansion of Papuan ancestry from Papua New Guinea to eastern Indonesia and Mindanao detected among the Blaan and Sangir.[32]

Under Spanish rule there was some immigration from elsewhere in the empire, especially from the Spanish Americas.[373][57][374] According to the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Research Program on Genes, Environment, and Health (RPGEH), a substantial proportion of Filipinos sampled have «modest» amounts of European descent consistent with older admixture.[375] In addition to this, the National Geographic project concluded in 2016 that people living in the Philippine archipelago carried genetic markers in the following percentages: 53% Southeast Asia and Oceania, 36% Eastern Asia, 5% Southern Europe, 3% Southern Asia, and 2% Native American[376] (From Latin America).[57]

A map that shows all ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines.

Chinese Filipinos are mostly the descendants of immigrants from Fujian in China after 1898,[377] numbering around 2 million, although there are an estimated 20% of Filipinos who have partial Chinese ancestry, stemming from precolonial and colonial Chinese migrants.[378] While a distinct minority, Chinese Filipinos are well integrated into Filipino society.[261][379] As of 2015, there are 220,000 to 600,000 American citizens living in the country.[380] There are also up to 250,000 Amerasians scattered across the cities of Angeles, Manila, and Olongapo.[381] Other important non-indigenous minorities include Indians[382][383] and Arabs.[384] There are also Japanese people, which include escaped Christians (Kirishitan) who fled the persecutions of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu.[385] The descendants of mixed-race couples are known as Tisoy.[386]

Languages

| Language | Speakers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tagalog | 24.44 % | 22,512,089 | |

| Cebuano | 21.35 % | 19,665,453 | |

| Ilokano | 8.77 % | 8,074,536 | |

| Hiligaynon | 8.44 % | 7,773,655 | |

| Waray | 3.97 % | 3,660,645 | |

| Other local languages/dialects | 26.09 % | 24,027,005 | |

| Other foreign languages/dialects | 0.09 % | 78,862 | |

| Not reported/not stated | 0.01 % | 6,450 | |

| TOTAL | 92,097,978 | ||

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority |

Ethnologue lists 186 individual languages in the Philippines, 182 of which are living languages, while 4 no longer have any known speakers. Most native languages are part of the Philippine branch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, which is a branch of the Austronesian language family.[365][388] In addition, various Spanish-based creole varieties collectively called Chavacano exist.[389] There are also many Philippine Negrito languages that have unique vocabularies that survived Austronesian acculturation.[390]

Filipino and English are the official languages of the country.[391] Filipino is a standardized version of Tagalog, spoken mainly in Metro Manila.[392] Both Filipino and English are used in government, education, print, broadcast media, and business, with third local languages often being used at the same time.[393] The Philippine constitution provides for the promotion of Spanish and Arabic on a voluntary and optional basis.[391] Spanish, which was widely used as a lingua franca in the late nineteenth century, has since declined greatly in use,[394] although Spanish loanwords are still present today in Philippine languages,[395][396] while Arabic is mainly taught in Islamic schools in Mindanao.[397]

Nineteen regional languages act as auxiliary official languages used as media of instruction: Aklanon, Bikol, Cebuano, Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Ibanag, Ilocano, Ivatan, Kapampangan, Kinaray-a, Maguindanao, Maranao, Pangasinan, Sambal, Surigaonon, Tagalog, Tausug, Waray, and Yakan.[4] Other indigenous languages such as, Cuyonon, Ifugao, Itbayat, Kalinga, Kamayo, Kankanaey, Masbateño, Romblomanon, Manobo, and several Visayan languages are prevalent in their respective provinces.[398] Article 3 of Republic Act No. 11106 declared the Filipino Sign Language as the national sign language of the Philippines, specifying that it shall be recognized, supported and promoted as the medium of official communication in all transactions involving the deaf, and as the language of instruction of deaf education.[399][400]

Religion

The Philippines is a secular state which protects freedom of religion. Christianity is the dominant faith,[401][402] shared by about 89% of the population.[403] As of 2013, the country had the world’s third largest Roman Catholic population, and was the largest Christian nation in Asia.[404] Census data from 2015 found that about 79.53% of the population professed Catholicism.[405] Around 37% of the population regularly attend Mass. 29% of self-identified Catholics consider themselves very religious.[406] An independent Catholic church, the Philippine Independent Church, has around 756,225 adherents.[405] Protestants were 9.13% of the population in 2015.[407] 2.64% of the population are members of Iglesia ni Cristo.[405] The combined following of the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches comes to 2.42% of the total population.[405][408]

Islam is the second largest religion. The Muslim population of the Philippines was reported as 6.01% of the total population according to census returns in 2015.[405] Conversely, a 2012 report by the National Commission of Muslim Filipinos stated that about 10,700,000 or 11% of Filipinos are Muslims.[401] The majority of Muslims live in Mindanao and nearby islands.[402][409] Most practice Sunni Islam under the Shafi’i school.[410]

The percentage of combined positive atheist and agnostic people in the Philippines was about 3% of the population as of 2008.[411] The 2015 Philippine Census reported the religion of about 0.02% of the population as «none».[405] A 2014 survey by Gallup International Association reported that 21% of its respondents identify as «not a religious person».[412] Around 0.24% of the population practice indigenous Philippine folk religions,[405] whose practices and folk beliefs are often syncretized with Christianity and Islam.[413][414] Buddhism is practiced by around 0.03% of the population,[405] concentrated among Filipinos of Chinese descent.[415]

Health

In 2016, 63.1% of healthcare came from private expenditures while 36.9% was from the government (12.4% from the national government, 7.1% from the local government, and 17.4% from social health insurance).[416] Total health expenditure share in GDP for the year 2021 was 6%.[417] Per capita health expenditure in 2021 was ₱9,839.23, higher than the ₱8,511.52 in 2020.[418] The budget allocation for Healthcare in 2019 was ₱98.6 billion[419] and had an increase in budget in 2014 with a record high in the collection of taxes from the House Bill 5727 (commonly known as Sin tax Bill).[420]

There were 101,688 hospital beds in the country in 2016, with government hospital beds accounting for 47% and private hospital beds for 53%.[421]

In 2009, there were an estimated 90,370 physicians or 1 per every 833 people, 480,910 nurses and 43,220 dentists.[422] Retention of skilled practitioners is a problem; seventy percent of nursing graduates go overseas to work.[423] Since 1967, the Philippines had become the largest global supplier of nurses for export.[424] The Philippines suffers a triple burden of high levels of communicable diseases, high levels of non-communicable diseases, and high exposure to natural disasters.[425]

In 2018, there were 1,258 hospitals licensed by the Department of Health, of which 433 (34%) were government-run and 825 (66%) private.[426] A total of 20,065 barangay health stations and 2,590 rural health units provide primary care services throughout the country as of 2016.[427] Cardiovascular diseases account for more than 35% of all deaths.[428][429] 9,264 cases of HIV were reported for the year 2016, with 8,151 being asymptomatic cases.[430] At the time the country was considered a low-HIV-prevalence country, with less than 0.1% of the adult population estimated to be HIV-positive.[431] HIV/AIDS cases increased from 12,000 in 2005[432] to 39,622 as of 2016, with 35,957 being asymptomatic cases.[430]

There is improvement in patients access to medicines due to Filipinos’ growing acceptance of generic drugs, with 6 out of 10 Filipinos already using generics.[433] While the country’s universal health care implementation is underway as spearheaded by the state-owned Philippine Health Insurance Corporation,[434] most healthcare-related expenses are either borne out of pocket[435] or through health maintenance organization (HMO)-provided health plans. The enactment of the Universal Health Care Act in 2019 by President Rodrigo Duterte facilitated the automatic enrollment of all Filipinos in the national health insurance program; as of March 2022, 94.79 million individuals were covered by these plans.[436]

Education

As of 2019, the Philippines had a basic literacy rate of 93.8% among five years old or older,[437] and a functional literacy rate of 91.6% among ages 10 to 64.[438] Education takes up a significant proportion of the national budget. In the 2020 budget, education was allocated PHP17.1 billion from the PHP4.1 trillion budget.[439]

The Commission on Higher Education lists 2,180 higher education institutions, among which 607 are public and 1,573 are private.[440] Primary and secondary schooling is divided between a 6-year elementary period, a 4-year junior high school period, and a 2-year senior high school period.[441][442][443] The Department of Education covers elementary, secondary, and non-formal education.[444] The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority administers middle-level education training and development.[445][446] The Commission on Higher Education was created in 1994 to, among other functions, formulate and recommend development plans, policies, priorities, and programs on higher education and research.[447] In 2004, madaris were mainstreamed in 16 regions nationwide, mainly in Muslim areas in Mindanao under the auspices and program of the Department of Education.[448]

Public universities are all non-sectarian entities and are classified as State Universities and Colleges or Local Colleges and Universities.[440] The University of the Philippines, a system of eight constituent universities, is the national university system of the Philippines.[449] The country’s top ranked universities are as follows: University of the Philippines, Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle University, and University of Santo Tomas.[450][451][452] The University of Santo Tomas, established in 1611, has the oldest extant university charter in the Philippines and Asia.[453][454]

Economy

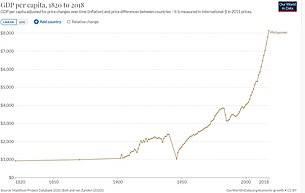

Real GDP per capita development of the Philippines

A proportional representation of Philippines exports, 2019

In 2020, the Philippine economy produced an estimated gross domestic product (nominal) of $367.4 billion.[455] Primary exports in 2019 included integrated circuits, office machinery/parts, insulated wiring, semiconductors, transformers; major trading partners included China (16%), United States (15%), Japan (13%), Hong Kong (12%), Singapore (7%), Germany (5%).[6] Its unit of currency is the Philippine peso (₱[456] or PHP[457]).[458]

A newly industrialized country,[459][460] the Philippine economy has been transitioning from one based upon agriculture to an economy with more emphasis upon services and manufacturing.[459] Of the country’s 2018 labor force of around 43.46 million, the agricultural sector employed 24.3%,[461] and accounted for 8.1% of 2018 GDP.[462] The industrial sector employed around 19% of the workforce and accounted for 34.1% of GDP, while 57% of the workers involved in the services sector were responsible for 57.8% of GDP.[462][463]

The unemployment rate as of October 2019, stands at 4.5%.[464] The inflation rate eased to 1.7% in August 2019.[465] Gross international reserves as of October 2022 are $94.074 billion.[466] The debt-to-GDP ratio continues to decline to 37.6% as of the second quarter of 2019[467][468] from a record high of 78% in 2004.[469] The country is a net importer[470] but is also a creditor nation.[471] Manila hosts the headquarters of the Asian Development Bank.[472]

Filipinos planting rice. Agriculture employs 23% of the Filipino workforce as of 2020.[473]

The 1997 Asian financial crisis affected the economy, resulting in a lingering decline of the value of the peso and falls in the stock market. The effects on the Philippines was not as severe as other Asian nations because of the fiscal conservatism of the government, partly as a result of decades of monitoring and fiscal supervision from the International Monetary Fund, in comparison to the massive spending of its neighbors on the rapid acceleration of economic growth.[157]

Remittances from overseas Filipinos contribute significantly to the Philippine economy;[474] in 2021, it reached a record US$34 billion, accounting for 8.9% of the national GDP.[475] Regional development is uneven, with Luzon – Metro Manila in particular – gaining most of the new economic growth at the expense of the other regions.[476][477]

Service industries such as tourism[478] and business process outsourcing (BPO) have been identified as areas with some of the best opportunities for growth for the country.[479] The business process outsourcing industry is composed of eight sub-sectors, namely, knowledge process outsourcing and back offices, animation, call centers, software development, game development, engineering design, and medical transcription.[480] In 2010, the Philippines was reported as having eclipsed India as the main center of BPO services in the world.[481][482][483]

Science and technology

The Department of Science and Technology is the governing agency responsible for the development of coordination of science and technology-related projects in the Philippines.[484] Research organizations in the country include the International Rice Research Institute,[485] which focuses on the development of new rice varieties and rice crop management techniques.[486] The Philippines bought its first satellite in 1996.[487] In 2016, the Philippines first micro-satellite, Diwata-1, was launched aboard the United States’ Cygnus spacecraft.[488]

The Philippines has a high concentration of cellular phone users.[489] Text messaging is a popular form of communication and, in 2007, the nation sent an average of one billion SMS messages per day.[490] The country has a high level of mobile financial services utilization.[491] The Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company, commonly known as PLDT, is a formerly nationalized telecommunications provider.[489] It is also the largest company in the country.[492] The National Telecommunications Commission is the agency responsible for the supervision, adjudication and control over all telecommunications services throughout the country.[493]

Tourism

Limestone cliffs of El Nido, Palawan.

The tourism sector contributed 5.2% of the country’s GDP in 2021, lower than the 12.7% recorded in 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic,[494] and provided 5.7 million jobs in 2019.[495] 8,260,913 international visitors arrived from January to December 2019, up by 15.24% for the same period in 2018.[496] 58.62% (4,842,774) of these came from East Asia, 15.84% (1,308,444) came from North America, and 6.38% (526,832) came from other ASEAN countries.[497] The island of Boracay, popular for its beaches, was named as the best island in the world by Travel + Leisure in 2012.[498] The Philippines is a popular retirement destination for foreigners because of its climate and low cost of living.[499]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Transportation in the Philippines is facilitated by road, air, rail and waterways. As of December 2018, there are 210,528 kilometers (130,816 mi) of roads in the Philippines, with only 65,101 kilometers (40,452 mi) of roads paved.[500] The 919-kilometer (571 mi) Strong Republic Nautical Highway, an integrated set of highway segments and ferry routes covering 17 cities, was established in 2003.[501] The Pan-Philippine Highway connects the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao, forming the backbone of land-based transportation in the country.[502] Roads are the dominant form of transport, carrying 98% of people and 58% of cargo. A network of expressways extends from the capital to other areas of Luzon.[503] The 8.25-kilometer (5.13 mi) Cebu–Cordova Link Expressway in Cebu opened in April 2022.[504] Traffic is a significant issue facing the country, especially within Manila and on arterial roads connecting to the capital.[505]

Public transport in the country include buses, jeepneys, UV Express, TNVS, Filcab, taxis, and tricycles.[506][507] Jeepneys are a popular and iconic public utility vehicle.[508] Jeepneys and other public utility vehicles which are older than 15 years are being phased out gradually in favor of a more efficient and environmentally friendly Euro 4 compliant vehicles.[509][510]

Despite wider historical use, rail transportation in the Philippines is limited, being confined to transporting passengers within Metro Manila, and the provinces of Laguna and Quezon,[511] with a separate short track in the Bicol Region.[512] There are plans to revive freight rail to reduce road congestion.[513][514] As of 2019, the country had a railway footprint of only 79 kilometers, which it had plans to expand up to 244 kilometers.[515][516] Metro Manila is served by three rapid transit lines: LRT Line 1, LRT Line 2 and MRT Line 3.[517][518][519] The PNR South Commuter Line transports passengers between Metro Manila and Laguna.[520] Railway lines that are under construction include the 22.8-kilometer (14.2 mi) MRT Line 7 (2020),[521] the 35-kilometer (22 mi) Metro Manila Subway (2025),[522] and the 109-kilometer (68 mi) PNR North–South Commuter Railway which is divided into several phases, with partial operations to begin in 2022.[523] The civil airline industry is regulated by the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines.[524]

Philippine Airlines is Asia’s oldest commercial airline still operating under its original name.[525][526] Cebu Pacific is the countries leading low-cost carrier.[527]

As an archipelago, inter-island travel using watercraft is often necessary.[528] Boats have always been important to societies in the Philippines.[529][530] Most boats are double-outrigger vessels, which can reach up to 30 meters (98 ft) in length, known as banca[531]/bangka,[532] parao, prahu, or balanghay. A variety of boat types are used throughout the islands, such as dugouts (baloto) and house-boats like the lepa-lepa.[530] Terms such as bangka and baroto are also used as general names for a variety of boat types.[532] Modern ships use plywood in place of logs and motor engines in place of sails.[531] These ships are used both for fishing and for inter-island travel.[532] The principal seaports of Manila, Batangas, Subic Bay, Cebu, Iloilo, Davao, Cagayan de Oro, General Santos, and Zamboanga form part of the ASEAN Transport Network.[533][534] The Pasig River Ferry serves the cities of Manila, Makati, Mandaluyong, Pasig and Marikina in Metro Manila.[535][536]

Water supply and sanitation

In 2015, it was reported by the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation that 74% of the population had access to improved sanitation, and that «good progress» had been made between 1990 and 2015.[537] As of 2016, 96% of Filipino households have an improved source of drinking water, and 92% of households had sanitary toilet facilities, although connections of these toilet facilities to appropriate sewerage systems remain largely insufficient especially in rural and urban poor communities.[538]

Culture

There is significant cultural diversity across the islands, reinforced by the fragmented geography of the country.[539] The cultures within Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago developed in a particularly distinct manner, since they had very limited Spanish influence and greater influence from nearby Islamic regions.[540] Despite this, a national identity emerged in the 19th century, the development of which is represented by shared national symbols and other cultural and historical touchstones.[539]

One of the most visible Hispanic legacies is the prevalence of Spanish names and surnames among Filipinos; a Spanish name and surname, however, does not necessarily denote Spanish ancestry. This peculiarity, unique among the people of Asia, came as a result of a colonial edict by Governor-General Narciso Clavería y Zaldua, which ordered the systematic distribution of family names and implementation of Hispanic nomenclature on the population.[541] The names of many locations are also Spanish or stem from Spanish roots and origins.[542]

There is a substantial American influence on modern Filipino culture.[261] The common use of the English language is an example of the American impact on Philippine society. It has contributed to the influence of American pop cultural trends.[543] This affinity is seen in Filipinos’ consumption of fast food and American film and music.[544] American global fast-food chain stalwarts have entered the market, but local fast-food chains like Goldilocks[545] and most notably Jollibee, the leading fast-food chain in the country, have emerged and compete successfully against foreign chains.[546]

Nationwide festivals include Ati-Atihan, Dinagyang, Moriones and Sinulog.[547][548][549]

Values

As a general description, the distinct value system of Filipinos is rooted primarily in personal alliance systems, especially those based in kinship, obligation, friendship, religion (particularly Christianity), and commercial relationships.[550] Filipino values are, for the most part, centered around maintaining social harmony, motivated primarily by the desire to be accepted within a group. The main sanction against diverging from these values are the concepts of «Hiya«, roughly translated as ‘a sense of shame’,[551] and «Amor propio» or ‘self-esteem’.[552] Social approval, acceptance by a group, and belonging to a group are major concerns. Caring about what others will think, say or do, are strong influences on social behavior among Filipinos.[553] Other elements of the Filipino value system are optimism about the future, pessimism about present situations and events, concern and care for other people, the existence of friendship and friendliness, the habit of being hospitable, religious nature, respectfulness to self and others, respect for the female members of society, the fear of God, and abhorrence of acts of cheating and thievery.[554][555]

Architecture

Colonial houses in Vigan.

Spanish architecture has left an imprint in the Philippines in the way many towns were designed around a central square or plaza mayor, but many of the buildings bearing its influence were demolished during World War II.[46] Four Philippine baroque churches are included in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the San Agustín Church in Manila, Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte, Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Santa María) Church in Ilocos Sur, and Santo Tomás de Villanueva Church in Iloilo.[556] Vigan in Ilocos Sur is known for the many Hispanic-style houses and buildings preserved there.[557]

American rule introduced new architectural styles. This led to the construction of government buildings and Art Deco theaters. During the American period, some semblance of city planning using the architectural designs and master plans by Daniel Burnham was done on the portions of the city of Manila. Part of the Burnham plan was the construction of government buildings that resembled Greek or Neoclassical architecture.[558] In Iloilo, structures from both the Spanish and American periods can still be seen, especially in Calle Real.[559] Certain areas of the country like Batanes have slight differences as both Spanish and Filipino ways of architecture assimilated differently because of the climate. Limestone was used as a building material, with houses being built to withstand typhoons.[560]

Music and dance

Cariñosa, a Hispanic era dance for traditional Filipino courtship.