Содержание

- Правитель Вавилона

- Успехи Хаммурапи

- Великий строитель

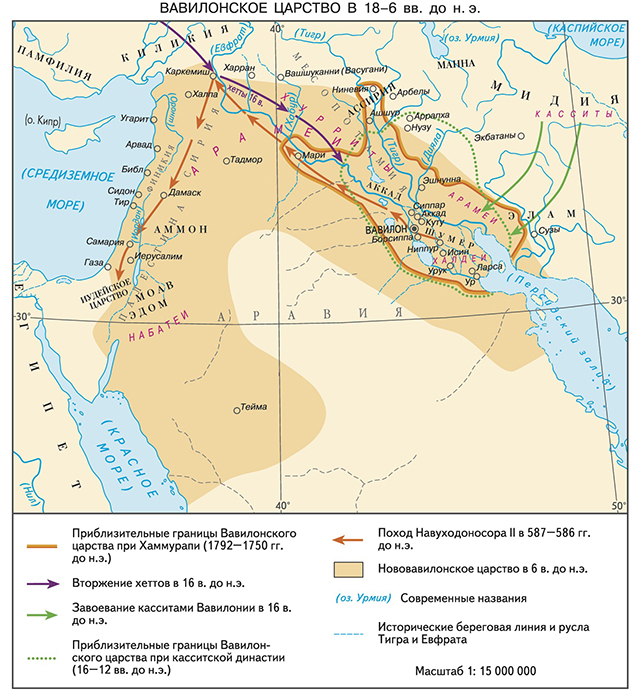

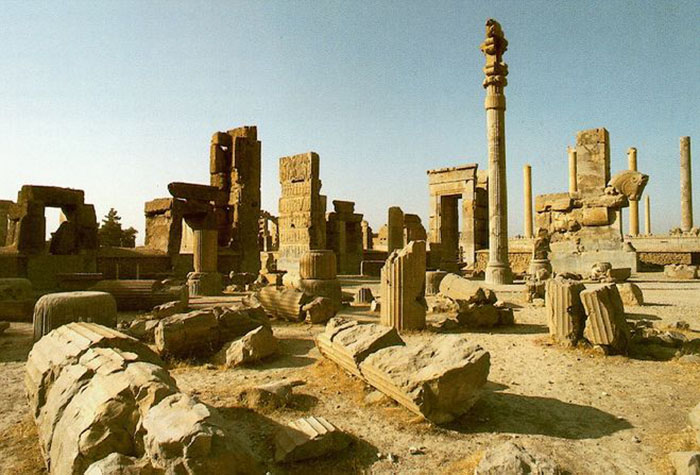

Память о прекрасном и величественной городе Вавилоне жива и в наши дни. Он появился там, где реки Тигр и Евфрат подходят наиболее близко друг к другу. Вавилонское царство прошло долгий путь от своего зарождения до запустения и распада, но время величия Вавилона связано с человеком, имя которого сохранилось в веках.

Могущественный правитель, мудрый царь Хаммурапи, сумел превратить Вавилон в главный торговый и политический центр Ближнего Востока. Этого правителя неслучайно называют великим строителем — Хаммурапи посвятил укреплению и развитию своего города многие годы. Кроме того, при нём были существенно расширены границы царства. А что же известно о жизни Хаммурапи?

Правитель Вавилона

О дате рождения знаменитого царя Хаммурапи историкам ничего не известно. Его правление началось примерно в 1790-х годах до нашей эры и продолжалось 43 года, а потому можно предположить, что на момент своего восшествия на вавилонский престол он был очень молод. Происхождение правителя тоже остаётся загадкой, которую частично может раскрыть его имя. Согласно одним предположениям. “Хамму-рапи” переводится как “предок-целитель”. А вот сторонники другой версии считают, что произносилось царское имя как “Хамму-раби” и переводилось как “великий предок”.

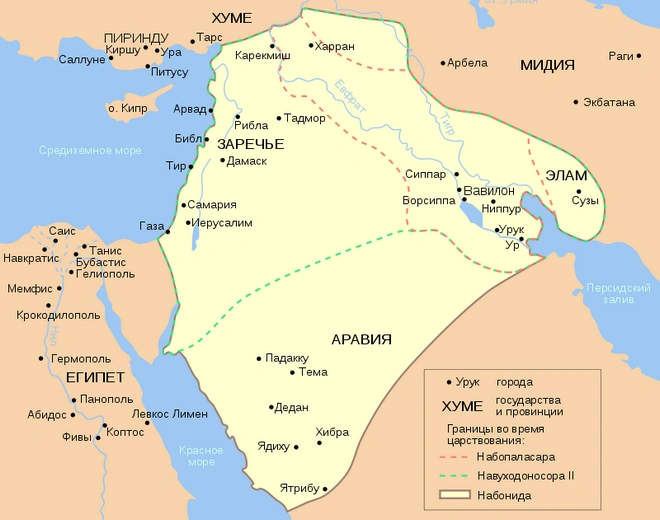

Став одним из самых молодых правителей Вавилонского царства, Хаммурапи вряд ли считал себя счастливцем. На тот момент его владения были весьма скромными и включали в себя всего семь крупных городов. А вот окружали Вавилонию грозные соседи — воинственные царства Ларсы, Эшнунны и Шамши-Адада I. Нельзя сказать, что начало правления Хаммурапи было успешно. Не имея опыта, он начал противостояние с Ларсой. Но после первых побед последовала череда поражений, а захваченные войсками Хаммурапи территории вновь были возвращены под контроль Ларсы.

Успехи Хаммурапи

Однако вавилонский царь умел не только стойко переносить удары судьбы, но и исправлять собственные ошибки. Война с Ларсой продолжалась три десятилетия и завершилась победой Хаммурапи, который стал властителем всего Шумера и был провозглашён “царем четырех стран света”. Он расширил границы своего государства, превратив Вавилонское царство в поистине великую державу, с интересами которой теперь считались даже самые воинственные соседи.

При Хаммурапи Вавилон действительно стал самым влиятельным государством Древнего мира, но это было не только заслугой военных успехов правителя. Мудрый царь умело сочетал мощь своей армии, дипломатическое искусство и умение укреплять границы своего молодого государства. Хаммурапи был величайшим политиком своего времени и очень дальновидным человеком. Понимая, что союз с одним из соседей выгоден, он заключал его, однако не поступался своими интересами. Но если со временем царь чувствовал, что проку от взаимной поддержки мало, с лёгкостью разрывал дипломатические отношения.

Великий строитель

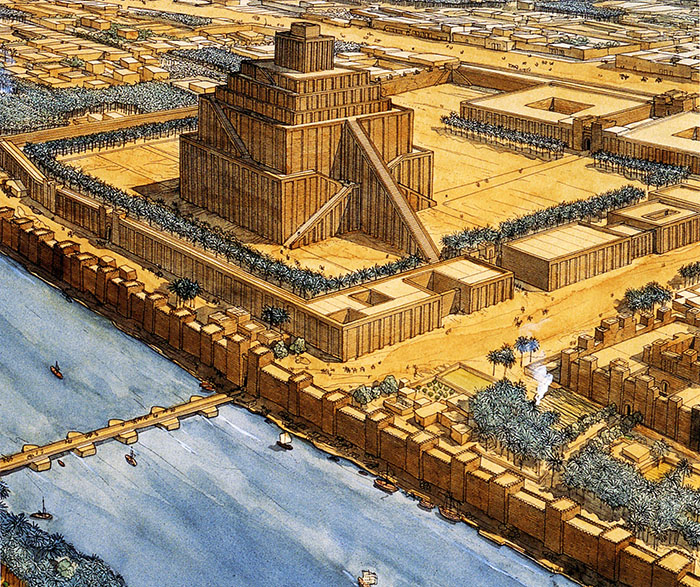

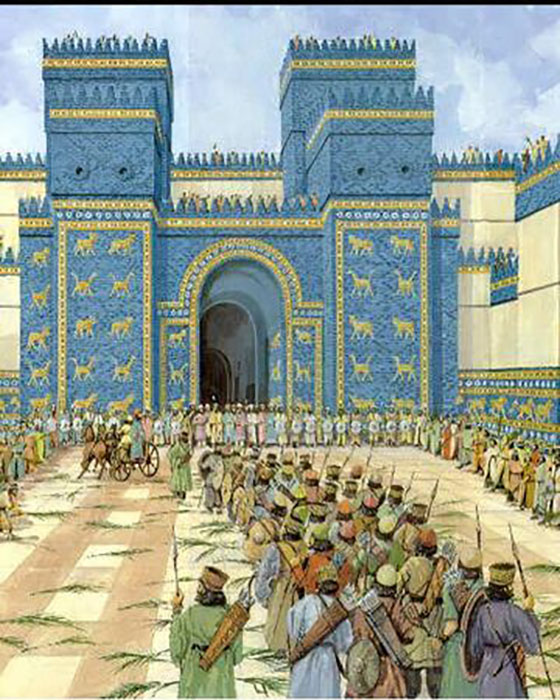

Хаммурапи мечтал укрепить Вавилон, превратив его в неприступную крепость. Он стал первым вавилонским царём, который возвёл защитные стены вокруг города. Кроме того, не забывал правитель и об авторитете среди подданных. За время своего правления он четырежды аннулировал долги народа, строил мосты и прокладывал новые дороги на подвластных землях.

При Хаммурапи был вырыт большой оросительный канал, что позволило уберечь Вавилонское царство от наводнений. При этом царь заявлял, что все его дела — лишь выполнение обязательств перед богами. Говоря современным языком, Хаммурапи знал, что такое грамотный пиар. При этом он не прикрывался ложной скромностью, прямо указывая на собственные заслуги. В “Истории цивилизации” Уилла Дюранта приводятся слова, сказанные царём после строительства оросительного канала:

“Берега Евфрата с обеих сторон я превратил в возделываемые земли. Я насыпал кучи зерна, я обеспечил землю безупречной водой… Разрознённых людей я собрал и обеспечил пастбищами и водой. Я дал им всё, я выпас их в изобилии и поселил в мирных жилищах”.

Хаммурапи правил Вавилонским царством на протяжении 43 лет. Он стал создателем Кодекса законов, заложившего основы правовой базы на территории Шумера. Несмотря на то, что некоторые законы Хаммурапи могут показаться современному человеку варварскими, есть среди них и те, которые не теряют актуальности по сей день — например, принцип презумпции невиновности или выплаты алиментов. К сожалению, последние годы царя были омрачены болезнью. Воспользовавшись слабостью правителя, его сын Самсу-илуна захватил престол ещё при жизни Хаммурапи, которому жить оставалось совсем недолго. Однако продолжить дела великого правителя Вавилона его последователям так и не удалось — никто не смог превзойти великого Хаммурапи.

В том месте, где реки Евфрат и Тигр подходят ближе всего друг к другу, когда-то существовал прекрасный город Вавилон, сумевший превратиться из небольшой территориальной общины в столицу великого Вавилонского царства.

За время своего существования он не раз подвергался разрушениям, набегам, захватам и окончательно опустел во II столетии, однако слава его сохранилась до наших дней. Своим величием Вавилон во многом обязан человеку по имени Хаммурапи, который смог превратить его в важнейший экономический и культурный центр Ближнего Востока.

Кто такой Хаммурапи? Чем он знаменит и что сделал для своего государства?

Кто такой Хаммурапи?

Хаммурапи – самый известный из вавилонских правителей. Дата его рождения до сих пор не установлена, но ученые сходятся во мнении, что во время восхождения на престол он был достаточно молод. Не знают историки и точного происхождения его имени.

Некоторые исследователи склоняются к прочтению «Хамму-раби», что означает «предок велик». Другие полагают, что царя называли «Хамму-рапи», то есть «предок-целитель».

Когда Хаммурапи начал править в Вавилонии, его государство было весьма скромным и помимо столицы включало только несколько небольших городов на расстоянии до 80 км. События его 43-летнего правления дошли до нас благодаря принятой в Месопотамии традиции называть годы по каким-либо деяниям правителей.

Начало царствования Хаммурапи ознаменовалось установлением так называемой «справедливости» (прощения долгов всем жителям), поэтому второй год его правления получил название «год справедливости Хаммурапи».

Когда правил Хаммупапи?

Считается, что Хаммурапи правил в период с 1793 по 1750 год до нашей эры. Его восхождение на трон проходило по наследственному принципу, то есть предшественником царя был его отец Син-мубаллит. К моменту начала его правления Вавилония существовала менее одного столетия и была окружена тремя грозными государствами – Шамши-Адад, Эшнунна и Ларса.

Сведения о первых 15 годах царствования Хаммурапи достаточно ограничены. Известно только, что он активно занимался строительством и несколько раз пытался расширить свои территории за счет соседних стран. Истинная слава пришла к нему только с 30-го года правления, когда царь совершил несколько победоносных походов и значительно увеличил размеры Вавилонского царства.

Чем прославился Хаммурапи?

Всю свою жизнь Хаммурапи стремился возвеличить Вавилонию и сделать ее самым могущественным центром Востока. На пути к поставленной цели он сумел покорить многие государства в окрестностях Вавилона, но наткнулся на жесткое сопротивление со стороны Римсина, правителя Ларсы.

Борьба между царствами длилась на протяжении 30 лет и, наконец, в 1762 году до нашей эры Ларса сдалась, а Римсин был изгнан за ее пределы. После победы Хаммурапи стал единоличным правителем всего Шумера и назывался «царем четырех стран света».

Наряду с военными победами, он прославился как мудрый правитель, создавший строго централизованную и упорядоченную систему власти. Царь придавал большое значение хозяйственным делам в своем государстве, вникал во все вопросы, проводил судебные и административные реформы.

Его законодательная деятельность была грандиозна по своим масштабам и до сих пор производит впечатление на историков. Во время своего правления Хаммурапи издал Кодекс законов, которые служили правосудию и позволяли поддерживать порядок в стране.

Какие законы ввел Хаммурапи?

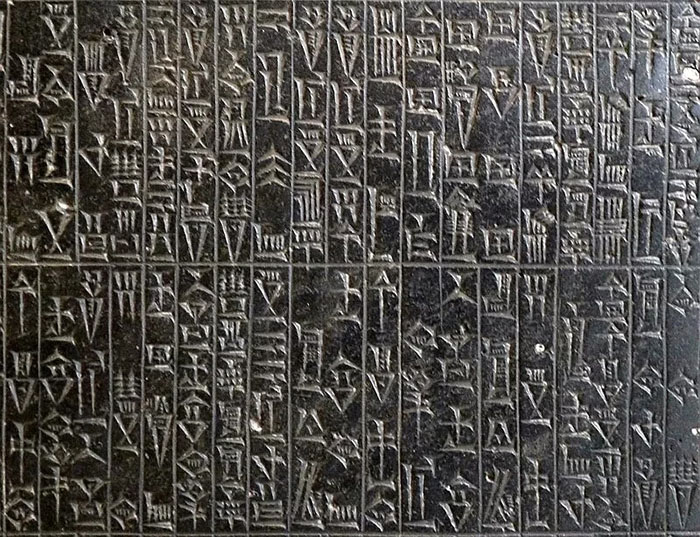

Законник Хаммурапи включал в себя 282 статьи и был высечен на камне на 35-ый год его царствования. Камень стоял на главной площади и напоминал горожанам, что никто не может отговориться незнанием законов. Спустя 600 лет Кодекс вывезли в Сузы, где позднее его обнаружили археологи. До нас дошли только 247 записей, поскольку остальные были стерты с течением времени.

Согласно законам Хаммурапи, господствующая роль в вавилонской семье отводилась мужу. Он мог распоряжаться своим семейством, а при необходимости продавать детей любому, кто захочет их купить.

Жена имела право на развод, но только в том случае, если муж занимался прелюбодеянием, необоснованно обвинял ее в неверности или покидал семью. Все дети наследовали имущество родителей в равных долях, независимо от пола.

В уголовном производстве предусматривалось правило равноправия. Если сын ударил отца, ему отрубали руку, если человек кому-то выколол глаз, ему тоже выкалывали глаз.

В целом же Кодекс законов Хаммурапи дает историкам более полное понимание жизни в Древней Месопотамии и выступает важнейшим источником древневосточного права, которого люди придерживались до II столетия нашей эры.

( 36 оценок, среднее 4.25 из 5 )

| King of Babylon | |

|---|---|

| šakkanakki Bābili šar Bābili |

|

Stylised version of the star of Shamash[a] |

|

Last native king |

|

| Details | |

| First monarch | Sumu-abum |

| Last monarch | Nabonidus (last native king) Shamash-eriba or Nidin-Bel (last native rebel) Artabanus III (last foreign ruler attested as king) Artabanus IV (last Parthian king in Babylonia) |

| Formation | c. 1894 BC |

| Abolition | 539 BC (last native king) 484 BC or 336/335 BC (last native rebel) AD 81 (last foreign ruler attested as king) AD 224 (last Parthian king in Babylonia) |

| Appointer | Various:

|

The king of Babylon (Akkadian: šakkanakki Bābili, later also šar Bābili) was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th century BC to its fall in the 6th century BC. For the majority of its existence as an independent kingdom, Babylon ruled most of southern Mesopotamia, composed of the ancient regions of Sumer and Akkad. The city experienced two major periods of ascendancy, when Babylonian kings rose to dominate large parts of the Ancient Near East: the First Babylonian Empire (or Old Babylonian Empire, c. 1894/1880–1595 BC) and the Second Babylonian Empire (or Neo-Babylonian Empire, 626–539 BC). Babylon was ruled by Hammurabi, who created Hammurabi’s code.

Many of Babylon’s kings were of foreign origin. Throughout the city’s nearly two-thousand year history, it was ruled by kings of native Babylonian (Akkadian), Amorite, Kassite, Elamite, Aramean, Assyrian, Chaldean, Persian, Greek and Parthian origin. A king’s cultural and ethnic background does not appear to have been important for the Babylonian perception of kingship, the important matter instead being whether the king was capable of executing the duties traditionally ascribed to the Babylonian king: establishing peace and security, upholding justice, honouring civil rights, refraining from unlawful taxation, respecting religious traditions, constructing temples, providing gifts to the gods in the temples and maintaining cultic order. Babylonian revolts of independence during the times the city was ruled by foreign empires probably had little to do with the rulers of these empires not being Babylonians and more to do with the rulers rarely visiting Babylon and failing to partake in the city’s rituals and traditions.

Babylon’s last native king was Nabonidus, who reigned from 556 to 539 BC. Nabonidus’s rule was ended through Babylon being conquered by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire. Though early Achaemenid kings continued to place importance on Babylon and continued using the title ‘king of Babylon’, later Achaemenid rulers being ascribed the title is probably only something done by the Babylonians themselves, with the kings themselves having abandoned it. Babylonian scribes continued to recognise rulers of the empires that controlled Babylonia as their kings until the time of the Parthian Empire, when Babylon was gradually abandoned. Though Babylon never regained independence after the Achaemenid conquest, there were several attempts by the Babylonians to drive out their foreign rulers and re-establish their kingdom, possibly as late as 336/335 BC under the rebel Nidin-Bel.

Introduction[edit]

Royal titles[edit]

Three different attested spellings in Neo-Babylonian Akkadian cuneiform for the title ‘king of Babylon’ (šar Bābili). The topmost rendition follows the Antiochus cylinder, the other two follow building inscriptions by Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC).

Throughout the city’s long history, various titles were used to designate the ruler of Babylon and its kingdom, the most common titles being ‘viceroy of Babylon’, ‘king of Karduniash’ and ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’.[2] Use of one of the titles did not mean that the others could not be used simultaneously. For instance, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 729–727 BC in Babylon), used all three of the aforementioned titles.[3]

- Viceroy (or governor) of Babylon (šakkanakki Bābili)[4] – emphasises the political dominion of Babylon itself.[2] For much of the city’s history, its rulers referred to themselves as viceroys or governors, rather than kings. The reason for this was that Babylon’s true king was formally considered to be its national deity, Marduk. By not explicitly claiming the royal title, Babylonian rulers thus showed reverence to the city’s god.[5] The reign of the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) has been noted as a particular break in this tradition,[5] as he assumed the title king of Babylon (šar Bābili),[6] which may have contributed to widespread negative reception of him in Babylonia.[5] However, šar Bābili is recorded as being used in some inscriptions from before Sennacherib’s time, such as in the inscriptions of his father and predecessor Sargon II (r. 710–705 BC in Babylon), who used it interchangeably with šakkanakki Bābili.[4] Though Sennacherib’s successors would primarily use šakkanakki Bābili,[7] there are likewise examples of them instead using šar Bābili.[8] The titles would also be used interchangeably by the later Neo-Babylonian kings.[9]

- King of Karduniash (šar Karduniaš)[10] – refers to rule of southern Mesopotamia as a whole.[2] ‘Karduniash’ was the Kassite name for the Babylonian kingdom, and the title ‘king of Karduniash’ was introduced by the city’s third dynasty (the Kassites).[11] The title continued to be used long after the Kassites had lost control of Babylon, for instance as late as under the native king Nabu-shuma-ukin I (r. c. 900–888 BC)[12] and the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC).[7]

- King of Sumer and Akkad (šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi)[13] – refers to rule of southern Mesopotamia as a whole.[2] A title originally used by the kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112–2004 BC), centuries prior to Babylon’s foundation. The title was used by kings to connect themselves to the culture and legacy of the Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations,[14] as well as to lay claim to the political hegemony achieved during the ancient Akkadian Empire. The title was also a geographical one, in that southern Mesopotamia was typically divided into the two regions Sumer (the south) and Akkad (the north), meaning that ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’ referred to rulership over the entire country.[11] The title was used by the Babylonian kings until the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC, and was also assumed by Cyrus the Great, who conquered Babylon and ruled Babylonia until his death in 530 BC.[15]

Role and legitimacy[edit]

The Babylonian kings derived their right to rule from divine appointment by Babylon’s patron deity Marduk and through consecration by the city’s priests.[16] Marduk’s main cult image (often conflated with the god himself), the statue of Marduk, was prominently used in the coronation rituals for the kings, who received their crowns «out of the hands» of Marduk during the New Year’s festival, symbolizing them being bestowed with kingship by the deity.[17] The king’s rule and his role as Marduk’s vassal on Earth were reaffirmed annually at this time of year, when the king entered the Esagila, Babylon’s main cult temple, alone on the fifth day of the New Year’s Festival each year and met with the high priest. The high priest removed the regalia from the king, slapped him across the face and made him kneel before Marduk’s statue. The king would then tell the statue that he had not oppressed his people and that he had maintained order throughout the year, whereafter the high priest would reply (on behalf of Marduk) that the king could continue to enjoy divine support for his rule, returning the royal regalia.[18] Through being a patron of Babylon’s temples, the king extended his generosity towards the Mesopotamian gods, who in turn empowered his rule and lent him their authority.[16]

Babylonian kings were expected to establish peace and security, uphold justice, honor civil rights, refrain from unlawful taxation, respect religious traditions and maintain cultic order. None of the king’s responsibilities and duties required him to be ethnically or even culturally Babylonian. Any foreigner sufficiently familiar with the royal customs of Babylonia could adopt the title, though they might then require the assistance of the native priesthood and the native scribes. Ethnicity and culture does not appear to have been important in the Babylonian perception of kingship: many foreign kings enjoyed support from the Babylonians and several native kings were despised.[19] That the rule of some foreign kings was not supported by the Babylonians probably has little to do with their ethnic or cultural background, but rather that they were perceived as not properly executing the traditional duties of the Babylonian king.[20]

Dynasties[edit]

The name of Babylon’s first dynasty (palû Babili, simply ‘dynasty of Babylon’) in Neo-Babylonian Akkadian cuneiform

As with other monarchies, the kings of Babylon are grouped into a series of royal dynasties, a practice started by the ancient Babylonians themselves in their king lists.[21][22] The generally accepted Babylonian dynasties should not be understood as familial groupings in the same vein as the term is commonly used by historians for ruling families in later kingdoms and empires. Though Babylon’s first dynasty did form a dynastic grouping where all monarchs were related, the dynasties of the first millennium BC, notably the Dynasty of E, did not constitute a series of coherent familial relationships at all. In a Babylonian sense, the term dynasty, rendered as palû or palê, related to a sequence of monarchs from the same ethnic or tribal group (i.e. the Kassite dynasty), the same region (i.e. the dynasties of the Sealand) or the same city (i.e. the dynasties of Babylon and Isin).[22] In some cases, kings known to be genealogically related, such as Eriba-Marduk (r. c. 769–760 BC) and his grandson Marduk-apla-iddina II (r. 722–710 BC and 703 BC), were separated into different dynasties, the former designated as belonging to the Dynasty of E and the latter as belonging to the (Third) Sealand dynasty.[23]

Sources[edit]

Among all the different types of documents uncovered through excavations in Mesopotamia, the most important for reconstructions of chronology and political history are king-lists and chronicles, grouped together under the term ‘chronographic texts’. Mesopotamian king lists are of special importance when reconstructing the sequences of monarchs, as they are collections of royal names and regnal dates, also often with additional information such as the relations between the kings, arranged in a table format. In terms of Babylonian rulers, the main document is the Babylonian King List (BKL), a group of three independent documents: Babylonian King List A, B, and C. In addition to the main Babylonian King Lists, there are also additional king-lists that record rulers of Babylon.[24]

- Babylonian King List A (BKLa, BM 33332)[25] — created at some point after the foundation of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Babylonian King List A records the kings of Babylon from the beginning of Babylon’s first dynasty under Sumu-abum (r. c. 1894–1881 BC) to Kandalanu (r. 648–627 BC). The end of the tablet is broken off, suggesting that it originally listed rulers after Kandalanu as well, possibly also listing the kings of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. All dynasties are separated by horizontal lines, under which subscript records a sum of the regnal years of each dynasty, and the number of kings the dynasties produced. Written in Neo-Babylonian script.[26]

- Babylonian King List B (BKLb, BM 38122)[25] — date of origin uncertain, written in Neo-Babylonian script. Babylonian King List B records the kings of Babylon’s first dynasty, and the kings of the First Sealand dynasty, with subscripts recording the number of kings and their summed up reigns in these dynasties. Regnal years are recorded for the kings of the first dynasty, but omitted for the kings of the Sealand dynasty. The regnal years used for the kings are inconsistent with their actual reign lengths, possibly due to the author having copied the list from a document where the years had been lost or damaged. The list records genealogical information for all but two of the kings of the first dynasty, but only for two of the kings of the Sealand dynasty. Because the document is essentially two lists for two dynasties, it is possible that it was copied and extracted from longer king lists in the late period for some unknown purpose.[26]

- Babylonian King List C (BKLc)[27] — a short text,[28] written in Neo-Babylonian script.[26] King List C is important as a source on the second dynasty of Isin, as the first seven lines of the preserved nine lines of text provide a portion of the sequence of kings of this dynasty and their dates. The corresponding section in Babylonian King List A is incompletely preserved.[28] As the list ends with the Isin dynasty’s seventh king, Marduk-shapik-zeri (r. c. 1081–1069 BC), it is possible that it was written during the reign of his successor, Adad-apla-iddina (r. c. 1068–1047 BC).[26] Its short length and unusual shape (being curved rather than flat)[28] means that it might have been a practice tablet used by a young Babylonian student.[26]

- Synchronistic King List (ScKL)[29] — a collection of individual tablets and examplars. The Synchronistic King List features two columns, and records the kings of Babylon and Assyria together, with kings recorded next to each other presumably being contemporaries. Unlike most of the other documents, this list generally omits regnal years and any genealogical information, but it also differs in including many of the chief scribes under the Assyrian and Babylonian kings. The tablet with the earliest known portion of the list begins with the Assyrian king Erishum I (uncertain regnal dates) and the Babylonian king Sumu-la-El (r. c. 1880–1845 BC). The latest known portion ends with Ashur-etil-ilani (r. 631–627 BC) in Assyria and Kandalanu in Babylon. As it is written in Neo-Assyrian script, it might have been created near the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[30]

- Uruk King List (UKL, IM 65066)[27] — the preserved portion of this king list records rulers from Kandalanu in the Assyrian period to Seleucus II Callinicus (r. 246–225 BC) in the Seleucid period.[27]

- Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period (BM 35603)[27] — written at Babylon at some point after 141 BC, recording rulers from the start of Hellenistic rule in Babylonia under Alexander the Great (r. 331–323 in Babylon),[31] to the end of Seleucid rule under Demetrius II Nicator (r. 145–141 BC in Babylon) and the conquest of Babylonia by the Parthian Empire.[32] Entries before Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305–281 BC) and after Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175–164 BC) are damaged and fragmentary.[33]

As years in Babylon were named after the current king, and the current year of their reign, date formulas in economic, astronomical and literary cuneiform texts written in Babylonia also provide highly important and useful chronological data.[34][35]

Kingship after the Neo-Babylonian Empire[edit]

In addition to the king lists described above, cuneiform inscriptions and tablets confidently establish that the Babylonians continued to recognise the foreign rulers of Babylonia as their legitimate monarchs after the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and throughout the rule of the Achaemenid (539–331 BC), Argead (331–310 BC), and Seleucid (305–141 BC) empires, as well as well into the rule of the Parthian Empire (141 BC – AD 224).[36]

Early Achaemenid kings greatly respected Babylonian culture and history, and regarded Babylonia as a separate entity or kingdom united with their own kingdom in something akin to a personal union.[17] Despite this, the Babylonians would grow to resent Achaemenid rule, just as they had resented Assyrian rule during the time their country was under the rule of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (722–626 BC).[17] Babylonian resentment of the Achaemenids likely had little to do with the Achaemenids being foreigners, but rather that the Achaemenid kings were perceived to not be capable of executing the duties of the Babylonian king properly, in line with established Babylonian tradition. This perception then led to frequent Babylonian revolts, an issue experienced by both the Assyrians and the Achaemenids. Since the capitals of the Assyrian and Achaemenid empires were elsewhere, these foreign kings did not regularly partake in the city’s rituals (meaning that they could not be celebrated in the same way that they traditionally were) and they rarely performed their traditional duties to the Babylonian cults through constructing temples and presenting cultic gifts to the city’s gods. This failure might have been interpreted as the kings thus not having the necessary divine endorsement to be considered true kings of Babylon.[37]

The standard regnal title used by the early Achaemenid kings, not only in Babylon but throughout their empire, was ‘king of Babylon and king of the lands’. The Babylonian title was gradually abandoned by the Achaemenid king Xerxes I (r. 486–465 BC), after he had to put down a major Babylonian uprising. Xerxes also divided the previously large Babylonian satrapy into smaller sub-units and, according to some sources, damaged the city itself in an act of retribution.[17] The last Achaemenid king whose own royal inscriptions officially used the title ‘king of Babylon’ was Xerxes I’s son and successor Artaxerxes I (r. 465–424 BC).[38] After Artaxerxes I’s rule there are few examples of monarchs themselves using the title, though the Babylonians continued to ascribe it to their rulers. The only known official explicit use of ‘king of Babylon’ by a king during the Seleucid period can be found in the Antiochus cylinder, a clay cylinder containing a text wherein Antiochus I Soter (r. 281–261 BC) calls himself, and his father Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305–281 BC), by the title ‘king of Babylon’, alongside various other ancient Mesopotamian titles and honorifics.[39] The Seleucid kings continued to respect Babylonian traditions and culture, with several Seleucid kings recorded as having «given gifts to Marduk» in Babylon and the New Year’s Festival still being recorded as a contemporary event.[40][41][42] One of the last times the festival is known to have been celebrated was in 188 BC, under the Seleucid king Antiochus III (r. 222–187 BC), who prominently partook in the rituals.[42] From the Hellenistic period (i. e. the rule of the Greek Argeads and Seleucids) onwards, Greek culture became established in Babylonia, but per Oelsner (2014), the Hellenistic culture «did not deeply penetrate the ancient Babylonian culture, that persisted to exist in certain domains and areas until the 2nd c. AD».[43]

Under the Parthian Empire, Babylon was gradually abandoned as a major urban centre and the old Babylonian culture diminished.[44] The nearby and newer imperial capitals cities of Seleucia and later Ctesiphon overshadowed the ancient city and became the seats of power in the region.[45] Babylon was still important in the first century or so of Parthian rule,[44] and cuneiform tablets continued to recognise the rule of the Parthian kings.[46] The standard title formula applied to the Parthian kings in Babylonian documents was «ar-ša-kâ lugal.lugal.meš» (Aršakâ šar šarrāni, «Arsaces, king of kings»).[47] Several tablets from the Parthian period also in their date formulae mention the queen of the incumbent Parthian king, alongside the king, the first time women were officially recognised as monarchs of Babylon.[48] The few documents that survive from Babylon in the Parthian period indicate a growing sense of alarm and alienation in Babylon as the Parthian kings were mostly absent from the city and the Babylonians noticed their culture slowly slipping away.[49]

When exactly Babylon was abandoned is unclear. The Roman author Pliny the Elder wrote in AD 50 that proximity to Seleucia had turned Babylon into a «barren waste» and during their campaigns in the east, Roman emperors Trajan (in AD 115) and Septimius Severus (in AD 199) supposedly found the city destroyed and deserted. Archaeological evidence and the writings of Abba Arikha (c. AD 219) indicate that at least the temples of Babylon may still have been active in the early 3rd century.[45] If any remnants of the old Babylonian culture still existed at that point, they would have been decisively wiped out as the result of religious reforms in the early Sasanian Empire c. AD 230.[50]

Due to a shortage of sources, and the timing of Babylon’s abandonment being unknown, the last ruler recognised by the Babylonians as king is not known. The latest known cuneiform tablet is W22340a, found at Uruk and dated to AD 79/80. The tablet preserves the word LUGAL (king), indicating that the Babylonians by this point still recognised a king.[51] At this time, Babylonia was ruled by the Parthian rival king (i. e. usurper) Artabanus III.[52] Modern historians are divided on where the line of monarchs ends. Spar and Lambert (2005) did not include any rulers beyond the first century AD in their list of kings recognised by the Babylonians,[36] but Beaulieu (2018) considered ‘Dynasty XIV of Babylon’ (his designation for the Parthians as rulers of the city) to have lasted until the end of Parthian rule of Babylonia in the early 3rd century AD.[53]

Names in cuneiform[edit]

The list below includes the names of all the kings in Akkadian, as well as how the Akkadian names were rendered in cuneiform signs. Up until the reign of Burnaburiash II (r. c. 1359–1333 BC) of the Kassite dynasty (Dynasty III), Sumerian was the dominant language for use in inscriptions and official documents, with Akkadian eclipsing it under the reign of Kurigalzu II (r. c. 1332–1308 BC), and thereafter replacing Sumerian in inscriptions and documents.[54] For consistency purposes, and because several kings and their names are known only from king lists,[55] which were written in Akkadian centuries after Burnaburiash II’s reign, this list solely uses Akkadian, rather than Sumerian, for the royal names, though this is anachronistic for rulers before Burnaburiash II.

It is not uncommon for there to be several different spellings of the same name in Akkadian, even when referring to the same individual.[56][57] To examplify this, the table below presents two ways the name of Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC) was spelt in Akkadian (Nabû-kudurri-uṣur). The list of kings below uses more concise spellings when possible, primarily based on the renditions of names in date formulae and king lists.

| Concise spelling (king lists) | Elaborate spelling (building inscriptions) |

|---|---|

Nabû — kudurri — uṣur[58] |

Na — bi — um — ku — du — ur — ri — u — ṣu — ur[59] |

Even if the same spelling is used, there were also several different scripts of cuneiform signs: a name, even if spelt the same, looks considerably different in Old Babylonian signs compared to Neo-Babylonian signs or Neo-Assyrian signs.[60] The table below presents different variants, depending on the signs used, of the name Antiochus in Akkadian (Antiʾukusu). The list of kings below uses Neo-Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian signs, given that those scripts are the signs primarily used in the king lists.

| Date formulae (Neo-Babylonian signs) | Antiochus cylinder[b] | Antiochus cylinder (Neo-Babylonian signs) | Antiochus cylinder (Neo-Assyrian signs) |

|---|---|---|---|

An — ti — ʾ — i — ku — su[62] |

An — ti — ʾ — ku — us[63] |

An — ti — ʾ — ku — us[64] |

An — ti — ʾ — ku — us[64] |

Dynasty I (Amorite), 1894–1595 BC[edit]

Per BKLb, the native name for this dynasty was simply palû Babili (‘dynasty of Babylon’).[65] To differentiate it from the other dynasties that later ruled Babylon, modern historians often refer to this dynasty as the ‘First Dynasty of Babylon’.[65] Some historians refer to this dynasty as the ‘Amorite dynasty’[66] on account of the kings being of Amorite descent.[67] While the king list gives a regnal length of 31 years for the final king, Samsu-Ditana, the destruction layer at Babylon is dated to his 26th year and no later sources have been found.[68]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumu-abum[c] | Šumu-abum |

c. 1894 BC | c. 1881 BC | First king of Babylon in BKLa and BKLb | [70] |

| Sumu-la-El | Šumu-la-El |

c. 1880 BC | c. 1845 BC | Unclear succession | [70] |

| Sabium | Sabūm |

c. 1844 BC | c. 1831 BC | Son of Sumu-la-El | [70] |

| Apil-Sin | Apil-Sîn |

c. 1830 BC | c. 1813 BC | Son of Sabium | [70] |

| Sin-Muballit | Sîn-Muballit |

c. 1812 BC | c. 1793 BC | Son of Apil-Sin | [70] |

| Hammurabi | Ḫammu-rāpi |

c. 1792 BC | c. 1750 BC | Son of Sin-Muballit | [70] |

| Samsu-iluna | Šamšu-iluna |

c. 1749 BC | c. 1712 BC | Son of Hammurabi | [70] |

| Abi-Eshuh | Abī-Ešuḫ |

c. 1711 BC | c. 1684 BC | Son of Samsu-iluna | [70] |

| Ammi-Ditana | Ammi-ditāna |

c. 1683 BC | c. 1647 BC | Son of Abi-Eshuh | [70] |

| Ammi-Saduqa | Ammi-Saduqa |

c. 1646 BC | c. 1626 BC | Son of Ammi-Ditana | [70] |

| Samsu-Ditana | Šamšu-ditāna |

c. 1625 BC | c. 1595 BC | Son of Ammi-Saduqa | [70] |

Dynasty II (1st Sealand), 1725–1475 BC[edit]

Both BKLa and BKLb refer to this dynasty as palû Urukug (‘dynasty of Urukug’). Presumably, the city of Urukug was the dynasty’s point of origin. Some literary sources refer to some of the kings of this dynasty as ‘kings of the Sealand’, and thus modern historians refer to it as a dynasty of the Sealand. The designation as the first Sealand dynasty differentiates it from Dynasty V, which the Babylonians actually referred to as a ‘dynasty of the Sealand’.[65] This dynasty overlaps with Dynasty I and Dynasty III, with these kings actually ruling the region south of Babylon (the Sealand) rather than Babylon itself.[22] For instance, the king Gulkishar of this dynasty was actually a contemporary of Dynasty I’s last king, Samsu-Ditana.[71] It is possible that the dynasty was included in Babylon’s dynastic history by later scribes either because it controlled Babylon for a time, because it controlled or strongly influenced parts of Babylonia or because it was the most stable power of its time in Babylonia.[72] The dates listed below are highly uncertain, and follow the timespan listed for the dynasty in Beaulieu (2018), c. 1725–1475 BC, with the individual dates based the lengths of the reigns of the kings, also as given by Beaulieu (2018).[73]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilum-ma-ili | Ilum-ma-ilī |

c. 1725 BC | ?? | Unclear succession | [74] |

| Itti-ili-nibi | Itti-ili-nībī |

?? | Unclear succession | [74] | |

| …[d] | — [e] |

?? | Unclear succession | [75] | |

| Damqi-ilishu | Damqi-ilišu |

[26 years(?)] | Unclear succession | [74] | |

| Ishkibal | Iškibal |

[15 years] | Unclear succession | [74] | |

| Shushushi | Šušši |

[24 years] | Brother of Ishkibal | [74] | |

| Gulkishar | Gulkišar |

[55 years] | Unclear succession | [74] | |

| mDIŠ-U-EN[f] | [Uncertain reading] |

?? | Unclear succession | [74] | |

| Peshgaldaramesh | Pešgaldarameš |

c. 1599 BC | c. 1549 BC | Son of Gulkishar | [74] |

| Ayadaragalama | Ayadaragalama |

c. 1548 BC | c. 1520 BC | Son of Peshgaldaramesh | [74] |

| Akurduana | Akurduana |

c. 1519 BC | c. 1493 BC | Unclear succession | [74] |

| Melamkurkurra | Melamkurkurra |

c. 1492 BC | c. 1485 BC | Unclear succession | [74] |

| Ea-gamil | Ea-gamil |

c. 1484 BC | c. 1475 BC | Unclear succession | [74] |

Dynasty III (Kassite), 1729–1155 BC[edit]

The entry for this dynasty’s name in BKLa is lost, but other Babylonian sources refer to it as palû Kasshi (‘dynasty of the Kassites’).[76] The reconstruction of the sequence and names of the early rulers of this dyansty, the kings before Karaindash, is difficult and controversial. The king lists are damaged at this point and the preserved portions seem to contradict each other: for instance, BKLa has a king in-between Kashtiliash I and Abi-Rattash, omitted in the Synchronistic King List, whereas the Synchronistic King List includes Kashtiliash II, omitted in BKLa, between Abi-Rattash and Urzigurumash. It also seems probable that the earliest kings ascribed to this dynasty in king lists did not actually rule Babylon, but were added as they were ancestors of the later rulers.[77] Babylonia was not fully consolidated and reunified until the reign of Ulamburiash, who defeated Ea-gamil, the last king of the first Sealand dynasty.[71]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gandash | Gandaš |

c. 1729 BC | c. 1704 BC | Unclear succession | [78] |

| Agum I | Agum |

c. 1703 BC | c. 1682 BC | Son of Gandash | [78] |

| Kashtiliash I | Kaštiliašu |

c. 1681 BC | c. 1660 BC | Son of Agum I | [78] |

| …[g] | — [h] |

c. 1659 BC | ?? | Unclear succession | [78] |

| Abi-Rattash | Abi-Rattaš |

?? | Son of Kashtiliash I | [80] | |

| Kashtiliash II | Kaštiliašu |

?? | Unclear succession | [80] | |

| Urzigurumash | Ur-zigurumaš |

?? | Descendant of Abi-Rattash (?)[i] | [80] | |

| Agum II[j] | Agum-Kakrime |

?? | Son of Urzigurumash | [80] | |

| Harba-Shipak | Ḫarba-Šipak |

?? | Unclear succession | [80] | |

| Shipta’ulzi | Šipta’ulzi |

?? | Unclear succession | [80] | |

| …[k] | — [l] |

?? | Unclear succession | [82] | |

| Burnaburiash I | Burna-Buriaš |

c. 1530 BC | c. 1500 BC | Unclear succession, earliest Kassite ruler confidently attested as ruling Babylon itself | [83] |

| Ulamburiash | Ulam-Buriaš |

[c. 1475 BC] | Son of Burnaburiash I (?), reunified Babylonia through defeating Ea-gamil, the last king of the first Sealand dynasty | [84] | |

| Kashtiliash III | Kaštiliašu |

?? | Son of Burnaburiash I (?) | [80] | |

| Agum III | Agum |

?? | Son of Kashtiliash III | [80] | |

| Kadashman-Sah[m] | Kadašman-Šaḥ |

?? | Unclear succession, co-ruler with Agum III? | [86] | |

| Karaindash | Karaindaš |

[c. 1415 BC] | Unclear succession | [80] | |

| Kadashman-Harbe I | Kadašman-Ḫarbe |

[c. 1400 BC] | Son of Karaindash (?) | [87] | |

| Kurigalzu I | Kuri-Galzu |

?? | Son of Kadashman-harbe I | [80] | |

| Kadashman-Enlil I | Kadašman-Enlil |

c. 1374 BC | c. 1360 BC | Son of Kurigalzu I (?)[n] | [80] |

| Burnaburiash II | Burna-Buriaš |

c. 1359 BC | c. 1333 BC | Son of Kadashman-Enlil I (?) | [80] |

| Kara-hardash | Kara-ḫardaš |

c. 1333 BC | c. 1333 BC | Son of Burnaburiash II (?) | [80] |

| Nazi-Bugash | Nazi-Bugaš |

c. 1333 BC | c. 1333 BC | Usurper, unrelated to other kings | [80] |

| Kurigalzu II | Kuri-Galzu |

c. 1332 BC | c. 1308 BC | Son of Burnaburiash II | [80] |

| Nazi-Maruttash | Nazi-Maruttaš |

c. 1307 BC | c. 1282 BC | Son of Kurigalzu II | [80] |

| Kadashman-Turgu | Kadašman-Turgu |

c. 1281 BC | c. 1264 BC | Son of Nazi-Maruttash | [80] |

| Kadashman-Enlil II | Kadašman-Enlil |

c. 1263 BC | c. 1255 BC | Son of Kadashman-Turgu | [80] |

| Kudur-Enlil | Kudur-Enlil |

c. 1254 BC | c. 1246 BC | Son of Kadashman-Enlil II | [80] |

| Shagarakti-Shuriash | Šagarakti-Šuriaš |

c. 1245 BC | c. 1233 BC | Son of Kudur-Enlil | [80] |

| Kashtiliash IV | Kaštiliašu |

c. 1232 BC | c. 1225 BC | Son of Shagarakti-Shuriash | [80] |

| Enlil-nadin-shumi[o] | Enlil-nādin-šumi |

c. 1224 BC | c. 1224 BC | Unclear succession | [80] |

| Kadashman-Harbe II[o] | Kadašman-Ḫarbe |

c. 1223 BC | c. 1223 BC | Unclear succession | [80] |

| Adad-shuma-iddina[o] | Adad-šuma-iddina |

c. 1222 BC | c. 1217 BC | Unclear succession | [80] |

| Adad-shuma-usur | Adad-šuma-uṣur |

c. 1216 BC | c. 1187 BC | Son of Kashtiliash IV (?) | [80] |

| Meli-Shipak | Meli-Šipak |

c. 1186 BC | c. 1172 BC | Son of Adad-shuma-usur | [80] |

| Marduk-apla-iddina I | Marduk-apla-iddina |

c. 1171 BC | c. 1159 BC | Son of Meli-Shipak | [80] |

| Zababa-shuma-iddin | Zababa-šuma-iddina |

c. 1158 BC | c. 1158 BC | Unclear succession | [80] |

| Enlil-nadin-ahi | Enlil-nādin-aḫe |

c. 1157 BC | c. 1155 BC | Unclear succession | [80] |

Dynasty IV (2nd Isin), 1153–1022 BC[edit]

Per BKLa, the native name of this dynasty was palû Ishin (‘dynasty of Isin’). Presumably, the city of Isin was the dynasty’s point of origin. Modern historians refer to this dynasty as the second dynasty of Isin to differentiate it from the ancient Sumerian dynasty of Isin.[65] Previous scholarship assumed that the first king of this dynasty, Marduk-kabit-ahheshu, ruled for the first years of his reign concurrently with the last Kassite king, but recent research suggests that this was not the case. This list follows the revised chronology of the kings of this dynasty, per Beaulieu (2018), which also means revising the dates of subsequent dynasties.[90]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marduk-kabit-ahheshu | Marduk-kabit-aḫḫēšu |

c. 1153 BC | c. 1136 BC | Unclear succession | [91] |

| Itti-Marduk-balatu | Itti-Marduk-balāṭu |

c. 1135 BC | c. 1128 BC | Son of Marduk-kabit-ahheshu | [91] |

| Ninurta-nadin-shumi | Ninurta-nādin-šumi |

c. 1127 BC | c. 1122 BC | Relative of Itti-Marduk-balatu (?)[p] | [91] |

| Nebuchadnezzar I | Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

c. 1121 BC | c. 1100 BC | Son of Ninurta-nadin-shumi | [91] |

| Enlil-nadin-apli | Enlil-nādin-apli |

c. 1099 BC | c. 1096 BC | Son of Nebuchadnezzar I | [91] |

| Marduk-nadin-ahhe | Marduk-nādin-aḫḫē |

c. 1095 BC | c. 1078 BC | Son of Ninurta-nadin-shumi, usurped the throne from Enlil-nadin-apli | [91] |

| Marduk-shapik-zeri | Marduk-šāpik-zēri |

c. 1077 BC | c. 1065 BC | Son of Marduk-nadin-ahhe (?)[q] | [91] |

| Adad-apla-iddina | Adad-apla-iddina |

c. 1064 BC | c. 1043 BC | Usurper, unrelated to previous kings | [94] |

| Marduk-ahhe-eriba | Marduk-aḫḫē-erība |

c. 1042 BC | c. 1042 BC | Unclear succession | [91] |

| Marduk-zer-X | Marduk-zēra-[—][r] |

c. 1041 BC | c. 1030 BC | Unclear succession | [91] |

| Nabu-shum-libur | Nabû-šumu-libūr |

c. 1029 BC | c. 1022 BC | Unclear succession | [91] |

Dynasty V (2nd Sealand), 1021–1001 BC[edit]

Per BKLa, the native name of this dynasty was palû tamti (‘dynasty of the Sealand’). Modern historians call it the second Sealand dynasty in order to distinguish it from Dynasty II.[65]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simbar-shipak | Simbar-Šipak |

c. 1021 BC | c. 1004 BC | Probably of Kassite descent, unclear succession | [96] |

| Ea-mukin-zeri | Ea-mukin-zēri |

c. 1004 BC | c. 1004 BC | Probably of Kassite descent (Bit-Hashmar clan), usurped the throne from Simbar-Shipak | [96] |

| Kashshu-nadin-ahi | Kaššu-nādin-aḫi |

c. 1003 BC | c. 1001 BC | Probably of Kassite descent, son of Simbar-shipak (?) | [96] |

Dynasty VI (Bazi), 1000–981 BC[edit]

BKLa refers to this dynasty as palû Bazu (‘dynasty of Baz’) and the Dynastic Chronicle calls it palû Bīt-Bazi (‘dynasty of Bit-Bazi’). The Bit-Bazi were a clan attested already in the Kassite period. It is likely that the dynasty derives its name either from the city of Baz, or from descent from Bazi, the legendary founder of that city.[97]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eulmash-shakin-shumi | Eulmaš-šākin-šumi |

c. 1000 BC | c. 984 BC | Possibly of Kassite descent (Bit-Bazi clan), unclear succession | [96] |

| Ninurta-kudurri-usur I | Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur |

c. 983 BC | c. 981 BC | Possibly of Kassite descent (Bit-Bazi clan), unclear succession | [96] |

| Shirikti-shuqamuna | Širikti-šuqamuna |

c. 981 BC | c. 981 BC | Possibly of Kassite descent (Bit-Bazi clan), brother of Ninurta-kudurri-usur I | [96] |

Dynasty VII (Elamite), 980–975 BC[edit]

BKLa dynastically separates Mar-biti-apla-usur from other kings with horizontal lines, marking him as belonging to a dynasty of his own. The Dynastic Chronicle also groups him by himself, and refers to his dynasty (containing only him) as the palû Elamtu (‘dynasty of Elam’).[98]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar-biti-apla-usur | Mār-bīti-apla-uṣur |

c. 980 BC | c. 975 BC | Described as having Elamite ancestry, unclear succession | [96] |

Dynasty VIII (E), 974–732 BC[edit]

Per BKLa, the native name of this dynasty was palû E (‘dynasty of E’). The meaning of ‘E’ is not clear, but it is likely a reference to the city of Babylon, meaning that the name should be interpreted as ‘dynasty of Babylon’. The time of the dynasty of E was a time of great instability and the unrelated kings grouped together under this dynasty even belonged to completely different ethnic groups. Another Babylonian historical work, the Dynastic Chronicle (though it is preserved only fragmentarily), breaks this dynasty up into a succession of brief, smaller, dynasties.[99]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nabu-mukin-apli | Nabû-mukin-apli |

c. 974 BC | c. 939 BC | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] |

| Ninurta-kudurri-usur II | Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur |

c. 939 BC | c. 939 BC | Babylonian, son of Nabu-mukin-apli | [100] |

| Mar-biti-ahhe-iddina | Mār-bῑti-aḫḫē-idinna |

c. 938 BC | ?? | Babylonian, son of Nabu-mukin-apli | [100] |

| Shamash-mudammiq | Šamaš-mudammiq |

?? | c. 901 BC[s] | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] |

| Nabu-shuma-ukin I | Nabû-šuma-ukin |

c. 900 BC[s] | c. 887 BC[t] | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] |

| Nabu-apla-iddina | Nabû-apla-iddina |

c. 886 BC[t] | c. 853 BC[t] | Babylonian, son of Nabu-shuma-ukin I | [100] |

| Marduk-zakir-shumi I | Marduk-zâkir-šumi |

c. 852 BC[t][u] | c. 825 BC[u] | Babylonian, son of Nabu-apla-iddina | [100] |

| Marduk-balassu-iqbi | Marduk-balāssu-iqbi |

c. 824 BC[u] | 813 BC[v] | Babylonian, son of Marduk-zakir-shumi I | [100] |

| Baba-aha-iddina | Bāba-aḫa-iddina |

813 BC[v] | 812 BC[v] | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] |

| Babylonian interregnum (at least four years)[w][x] | |||||

| Ninurta-apla-X | Ninurta-apla-[—][y] |

?? | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] | |

| Marduk-bel-zeri | Marduk-bēl-zēri |

?? | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] | |

| Marduk-apla-usur | Marduk-apla-uṣur |

?? | c. 769 BC[z] | Chaldean chief of an uncertain tribe, unclear succession | [100] |

| Eriba-Marduk | Erība-Marduk |

c. 769 BC[z] | c. 760 BC[z] | Chaldean chief of the Bit-Yakin tribe, unclear succession | [100] |

| Nabu-shuma-ishkun | Nabû-šuma-iškun |

c. 760 BC[z] | 748 BC | Chaldean chief of the Bit-Dakkuri tribe, unclear succession | [100] |

| Nabonassar | Nabû-nāṣir |

748 BC | 734 BC | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] |

| Nabu-nadin-zeri | Nabû-nādin-zēri |

734 BC | 732 BC | Babylonian, son of Nabonassar | [100] |

| Nabu-shuma-ukin II | Nabû-šuma-ukin |

732 BC | 732 BC | Babylonian, unclear succession | [100] |

- note: Babylonian King List A records the names of 17 kings of the dynasty of E, but it states afterwards that the dynasty comprised 22 kings. The discrepancy might be explainable as a scribal error, but it is also possible that there were further kings in the sequence. The list is broken at critical points, and it is possible that five additional kings, whose names thus do not survive, could be inserted between the end of the Babylonian interregnum and the reign of Ninurta-apla-X.[107] Lists of Babylonian rulers by modern historians tend to list Ninurta-apla-X as the first king to rule after Baba-aha-iddina’s deposition.[100]

Dynasty IX (Assyrian), 732–626 BC[edit]

‘Dynasty IX’ is used to, broadly speaking, refer to the rulers of Babylonia during the time it was ruled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, including Assyrian kings of both the Adaside dynasty and the subsequent Sargonid dynasty, as well as various non-dynastic vassal and rebel kings. They are often grouped together as a dynasty by modern scholars as BKLa does not use lines to separate the rulers, used elsewhere in the list to separate dynasties.[22] BKLa also assigns individual dynastic labels to some of the kings, though thus not in the same fashion as is done for the more concrete earlier dynasties.[22] The palê designation associated with each king (they are recorded in the list up until Mushezib-Marduk) is included in the table below and follows Fales (2014).[108]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | palê | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nabu-mukin-zeri | Nabû-mukin-zēri |

732 BC | 729 BC | palê Šapî ‘Dynasty of Shapi’ |

Chaldean chief of the Bit-Amukkani tribe, usurped the throne | [109] |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | Tukultī-apil-Ešarra |

729 BC | 727 BC | palê Baltil ‘Dynasty of [Assur]’ |

King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — conquered Babylon | [109] |

| Shalmaneser V | Salmānu-ašarēd |

727 BC | 722 BC | King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — son of Tiglath-Pileser III | [109] | |

| Marduk-apla-iddina II (First reign) |

Marduk-apla-iddina |

722 BC | 710 BC | palê Tamti ‘Dynasty of the Sealand’ |

Chaldean chief of the Bit-Yakin tribe, proclaimed king upon Shalmaneser V’s death | [109] |

| Sargon II | Šarru-kīn |

710 BC | 705 BC | palê Ḫabigal ‘Dynasty of [Hanigalbat]’ |

King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — son of Tiglath-Pileser III (?) | [109] |

| Sennacherib (First reign) |

Sîn-ahhe-erība |

705 BC | 703 BC | King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — son of Sargon II | [109] | |

| Marduk-zakir-shumi II | Marduk-zâkir-šumi |

703 BC | 703 BC | A Arad-Ea ‘Son [descendant] of Arad-Ea’ |

Babylonian rebel of the Arad-Ea family, rebel king | [109] |

| Marduk-apla-iddina II (Second reign) |

Marduk-apla-iddina |

703 BC | 703 BC | ERÍN Ḫabi ‘Soldier of [Hanigalbat?]’ |

Chaldean chief of the Bit-Yakin tribe, retook the throne | [109] |

| Bel-ibni | Bel-ibni |

703 BC | 700 BC | palê E ‘Dynasty of E’ |

Babylonian vassal king of the Rab-bānî family, appointed by Sennacherib | [109] |

| Ashur-nadin-shumi | Aššur-nādin-šumi |

700 BC | 694 BC | palê Ḫabigal ‘Dynasty of [Hanigalbat]’ |

Son of Sennacherib, appointed as vassal king by his father | [109] |

| Nergal-ushezib | Nergal-ušezib |

694 BC | 693 BC | palê E ‘Dynasty of E’ |

Babylonian rebel of the Gaḫal kin family, rebel king | [109] |

| Mushezib-Marduk | Mušezib-Marduk |

693 BC | 689 BC | Chaldean chief of the Bit-Dakkuri tribe, rebel king | [109] | |

| Sennacherib[aa] (Second reign) |

Sîn-ahhe-erība |

689 BC | 20 October 681 BC |

King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — retook Babylon | [113] | |

| Esarhaddon | Aššur-aḫa-iddina |

December 681 BC |

1 November 669 BC |

King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — son of Sennacherib | [114] | |

| Ashurbanipal[ab] (First reign) |

Aššur-bāni-apli |

1 November 669 BC |

March 668 BC |

King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — son of Esarhaddon | [110] | |

| Shamash-shum-ukin | Šamaš-šuma-ukin |

March 668 BC |

648 BC | Son of Esarhaddon, designated by his father as heir to Babylon, invested as vassal king by Ashurbanipal | [110] | |

| Ashurbanipal[ac] (Second reign) |

Aššur-bāni-apli |

648 BC | 646 BC | King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — retook Babylon after rebellion by Shamash-shum-ukin | [116] | |

| Kandalanu | Kandalānu |

647 BC | 627 BC | Appointed as vassal king by Ashurbanipal | [110] | |

| Sin-shumu-lishir[ad] | Sîn-šumu-līšir |

626 BC | 626 BC | Usurper in the Neo-Assyrian Empire — recognised in Babylonia | [110] | |

| Sinsharishkun[ad] | Sîn-šar-iškun |

626 BC | 626 BC | King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — son of Ashurbanipal | [110] |

Dynasty X (Chaldean), 626–539 BC[edit]

The native name for this dynasty does not appear in any sources, as the kings of Dynasty X are only listed in king lists made during the Hellenistic period, when the concept of dynasties ceased being used by Babylonians chronographers to describe Babylonian history. Modern historians typically refer to the dynasty as the ‘Neo-Babylonian dynasty’, as these kings ruled the Neo-Babylonian Empire, or the ‘Chaldean dynasty’, after the presumed ethnic origin of the royal line.[22] The Dynastic Chronicle, a later document, refers to Nabonidus as the founder and only king of the ‘dynasty of Harran’ (palê Ḫarran), and may also indicate a dynastic change with Neriglissar’s accession, but much of the text is fragmentary.[118][119]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nabopolassar | Nabû-apla-uṣur |

22/23 November 626 BC |

July 605 BC |

Babylonian rebel, defeated Sinsharishkun | [120] |

| Nebuchadnezzar II | Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

August 605 BC |

7 October 562 BC |

Son of Nabopolassar | [120] |

| Amel-Marduk | Amēl-Marduk |

7 October 562 BC |

August 560 BC |

Son of Nebuchadnezzar II | [120] |

| Neriglissar | Nergal-šar-uṣur |

August 560 BC |

April 556 BC |

Son-in-law of Nebuchadnezzar II, usurped the throne | [120] |

| Labashi-Marduk | Lâbâši-Marduk |

April 556 BC |

June 556 BC |

Son of Neriglissar | [120] |

| Nabonidus | Nabû-naʾid |

25 May 556 BC |

13 October 539 BC |

Son-in-law of Nebuchadnezzar II (?), usurped the throne | [121] |

Babylon under foreign rule, 539 BC – AD 224[edit]

The concept of dynasties ceased being used in king-lists made after the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, meaning that the native Babylonian designations for the ruling dynasties of the foreign empires that succeeded the Chaldean kings are unknown.[22]

Dynasty XI (Achaemenid), 539–331 BC[edit]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrus II the Great | Kuraš |

29 October 539 BC |

August 530 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — conquered Babylon | [122] |

| Cambyses II | Kambuzīa |

August 530 BC |

April 522 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Cyrus II | [122] |

| Bardiya | Barzia |

April/May 522 BC |

29 September 522 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Cyrus II or an impostor | [122] |

| Nebuchadnezzar III | Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

3 October 522 BC |

December 522 BC |

Babylonian rebel of the Zazakku family, claimed to be a son of Nabonidus | [123] |

| Darius I the Great (First reign) |

Dariamuš |

December 522 BC |

25 August 521 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — distant relative of Cyrus II | [122] |

| Nebuchadnezzar IV | Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

25 August 521 BC |

27 November 521 BC |

Babylonian rebel of Armenian descent, claimed to be a son of Nabonidus | [124] |

| Darius I the Great (Second reign) |

Dariamuš |

27 November 521 BC |

November 486 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — retook Babylon | [122] |

| Xerxes I the Great (First reign) |

Aḥšiaršu |

November 486 BC |

July 484 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Darius I | [122] |

| Shamash-eriba | Šamaš-eriba |

July 484 BC |

October 484 BC |

Babylonian rebel | [125] |

| Bel-shimanni | Bêl-šimânni |

July 484 BC |

August 484 BC |

Babylonian rebel | [125] |

| Xerxes I the Great (Second reign) |

Aḥšiaršu |

October 484 BC |

465 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire — retook Babylon | [122] |

| Artaxerxes I | Artakšatsu |

465 BC | December 424 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Xerxes I | [122] |

| Xerxes II | — [ae] |

424 BC | 424 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Artaxerxes I | [122] |

| Sogdianus | — [ae] |

424 BC | 423 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire — illegitimate son of Artaxerxes I | [122] |

| Darius II | Dariamuš |

February 423 BC |

c. April 404 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — illegitimate son of Artaxerxes I | [122] |

| Artaxerxes II | Artakšatsu |

c. April 404 BC |

359/358 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Darius II | [122] |

| Artaxerxes III | Artakšatsu |

359/358 BC | 338 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Artaxerxes II | [122] |

| Artaxerxes IV | Artakšatsu |

338 BC | 336 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire — son of Artaxerxes III | [122] |

| Nidin-Bel | Nidin-Bêl |

336 BC | 336/335 BC | Babylonian rebel (?), attested only in the Uruk King List, alternatively a scribal error | [126] |

| Darius III | Dariamuš |

336/335 BC | October 331 BC |

King of the Achaemenid Empire — grandson of Artaxerxes II | [122] |

Dynasty XII (Argead), 331–305 BC[edit]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander III the Great | Aliksandar |

October 331 BC |

11 June 323 BC |

King of Macedon — conquered the Achaemenid Empire | [127] |

| Philip III Arrhidaeus | Pilipsu |

11 June 323 BC |

317 BC[af] | King of Macedon — brother of Alexander III | [129] |

| Antigonus I Monophthalmus[ag] | Antigunusu |

317 BC | 309/308 BC | King of the Antigonid Empire — general (Diadochus) of Alexander III | [132] |

| Alexander IV | Aliksandar |

316 BC | 310 BC[ah] | King of Macedon — son of Alexander III | [134] |

Dynasty XIII (Seleucid), 305–141 BC[edit]

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seleucus I Nicator | Siluku |

305 BC[ai] | September 281 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — general (Diadochus) of Alexander III | [134] |

| Antiochus I Soter | Antiʾukusu |

294 BC[aj] | 2 June 261 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Seleucus I | [136] |

| Seleucus[ak] | Siluku |

281 BC | 266 BC | Joint-king of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus I | [137] |

| Antiochus II Theos | Antiʾukusu |

266 BC[aj] | July 246 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus I | [136] |

| Seleucus II Callinicus | Siluku |

July 246 BC |

225 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus II | [136] |

| Seleucus III Ceraunus | Siluku |

225 BC | 223 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Seleucus II | [138] |

| Antiochus III the Great | Antiʾukusu |

223 BC | 3 July 187 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Seleucus II | [138] |

| Antiochus[al] | Antiʾukusu |

210 BC | 192 BC | Joint-king of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus III | [140] |

| Seleucus IV Philopator | Siluku |

189 BC[aj] | 3 September 175 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus III | [141] |

| Antiochus IV Epiphanes | Antiʾukusu |

3 September 175 BC |

164 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus III | [142] |

| Antiochus[al] | Antiʾukusu |

175 BC | 170 BC | Joint-king of the Seleucid Empire — son of Seleucus IV | [143] |

| Antiochus V Eupator | Antiʾukusu |

164 BC | 162 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Antiochus IV | [144] |

| Demetrius I Soter (First reign) |

Dimitri |

c. January 161 BC[am] |

c. January 161 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Seleucus IV | [146] |

| Timarchus | — [an] |

c. January 161 BC[ao] |

c. May 161 BC[ao] |

Rebel satrap (vassal governor) under the Seleucids — captured and briefly ruled Babylonia | [147] |

| Demetrius I Soter (Second reign) |

Dimitri |

c. May 161 BC |

150 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — reconquered Babylonia | [148] |

| Alexander Balas | Aliksandar |

150 BC | 146 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — supposedly son of Antiochus IV | [149] |

| Demetrius II Nicator | Dimitri |

146 BC | 141 BC | King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Demetrius I | [150] |

Dynasty XIV (Arsacid), 141 BC – AD 224[edit]

- note: The chronology of the Parthian kings, especially in the early period, is disputed on account of a lack of sources. The chronology here, which omits several rival kings and usurpers, primarily follows Shayegan (2011),[151] Dąbrowa (2012)[152] and Daryaee (2012).[153] For alternate interpretations, see the List of Parthian monarchs.

| King | Akkadian | Reigned from | Reigned until | Succession | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mithridates I | Aršakâ[ap] |

141 BC | 132 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — conquered Babylonia | [156] |

| Phraates II (First reign) |

Aršakâ |

132 BC | July 130 BC |

King of the Parthian Empire — son of Mithridates I | [157] |

| Rinnu[aq] | Ri-[—]-nu[ar] |

132 BC | July 130 BC |

Mother and regent for Phraates II, who was a minor at the time of his accession | [157] |

| Antiochus VII Sidetes | Antiʾukusu |

July 130 BC |

November 129 BC |

King of the Seleucid Empire — son of Demetrius I, conquered Babylonia | [160] |

| Phraates II (Second reign) |

Aršakâ |

November 129 BC |

128/127 BC[as] | King of the Parthian Empire — reconquered Babylonia | [162] |

| Ubulna[at] | Ubulna |

November 129 BC |

128/127 BC | Unclear identity, associated with Phraates II – probably his queen | [162] |

| Hyspaosines | Aspasinē |

128/127 BC[as] | November 127 BC |

King of Characene — captured Babylon in the wake of Antiochus VII Sidetes’s campaign | [163] |

| Artabanus I | Aršakâ |

November 127 BC |

124 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — brother of Mithridates I, conquered Babylonia | [164] |

| Mithridates II | Aršakâ |

124 BC | 91 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Artabanus I | [165] |

| Gotarzes I | Aršakâ |

91 BC | 80 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Mithridates II | [166] |

| Asi’abatar[at] | Aši’abatum |

91 BC | 80 BC | Wife (queen) of Gotarzes I | [166] |

| Orodes I | Aršakâ |

80 BC | 75 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Mithridates II or Gotarzes I | [167] |

| Ispubarza[at] | Isbubarzâ | 80 BC | 75 BC | Sister-wife (queen) of Orodes I | [168] |

| Sinatruces | Aršakâ |

75 BC | 69 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son or brother of Mithridates I | [169] |

| Phraates III | Aršakâ |

69 BC | 57 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Sinatruces | [170] |

| Piriustana[at] | Piriustanâ | 69 BC | ?? | Wife (queen) of Phraates III | [171] |

| Teleuniqe[at] | Ṭeleuniqê | ?? | 57 BC | Wife (queen) of Phraates III | [171] |

| Orodes II | Aršakâ |

57 BC | 38 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Phraates III | [172] |

| Phraates IV | Aršakâ |

38 BC | 2 BC | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Orodes II | [173] |

| Phraates V[au] | Aršakâ |

2 BC | AD 4 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Phraates IV | [174] |

| Orodes III | Aršakâ |

AD 4 | AD 6 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Phraates IV (?) | [175] |

| Vonones I | Aršakâ |

AD 6 | AD 12 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Phraates IV | [176] |

| Artabanus II | Aršakâ |

AD 12 | AD 38 | King of the Parthian Empire — grandson of Phraates IV (?) | [177] |

| Vardanes I | Aršakâ |

AD 38 | AD 46 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Artabanus II | [177] |

| Gotarzes II | Aršakâ |

AD 38 | AD 51 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Artabanus II | [177] |

| Vonones II | Aršakâ |

AD 51 | AD 51 | King of the Parthian Empire — grandson of Phraates IV (?) | [178] |

| Vologases I | Aršakâ |

AD 51 | AD 78 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Vonones II or Artabanus II | [156] |

| Pacorus II | Aršakâ |

AD 78 | AD 110 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Vologases I | [179] |

| Artabanus III[av] | Aršakâ |

AD 79/80 | AD 81 | Rival king of the Parthian Empire (against Pacorus II) — son of Vologases I | [180] |

| Osroes I | — [aw] |

AD 109 | AD 129 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Pacorus II | [181] |

| Vologases III | — [aw] |

AD 110 | AD 147 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Pacorus II | [182] |

| Parthamaspates | — [aw] |

AD 116 | AD 117 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Osroes I | [183] |

| Vologases IV | — [aw] |

AD 147 | AD 191 | King of the Parthian Empire — grandson of Pacorus II | [183] |

| Vologases V | — [aw] |

AD 191 | AD 208 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Vologases IV | [184] |

| Vologases VI | — [aw] |

AD 208 | AD 216/228 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Vologases V | [185] |

| Artabanus IV | — [aw] |

AD 216 | AD 224 | King of the Parthian Empire — son of Vologases V | [186] |

See also[edit]

- List of Assyrian kings – for the Assyrian kings

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties – for other dynasties and kingdoms in ancient Mesopotamia

Notes[edit]

- ^ The star of Shamash was often used as a standard in southern Mesopotamia from the Akkadian period down to the Neo-Babylonian period.[1]

- ^ The Antiochus cylinder is written in Babylonian cuneiform, though with some unorthodox and strange choices of signs. Its rendition of the name Antiochus is featured here, alongside transcriptions of the same spelling of Antiochus, but with ordinary Babylonian and Assyrian signs, to illustrate the differences.[61]

- ^ Sumu-abum was the first king of Babylon according to Babylonian King Lists A and B. There is no contemporary evidence for his rule in Babylon; the earliest ruler who there is textual evidence of in Babylon itself is Sin-Muballit, the fifth king according to the king lists. Sumu-abum is contemporarily attested as a ruler of the cities Dilbat, Sippar and Kisurra, but some evidence seems to suggest that he and Sumu-la-El (his supposed successor) were contemporaries. Later rulers of Babylon’s first dynasty referred to Sumu-la-El, rather than Sumu-abum, as the founder of their dynasty. It is possible that Sumu-abum did not rule Babylon, but for some reason was inserted in later traditions into the city’s dynastic history. Perhaps Sumu-la-El ruled Babylon as a vassal of Sumu-abum, who might have ruled a larger group of territories.[69]

- ^ No king list includes a king between Itti-ili-nibi and Damqi-ilishu, and Babylonian King List A states that Dynasty II had 11 kings, speaking against the existence of this figure. The existence of an unknown king here is thus very speculative, based on the presence of the sign AŠ between lines 5 and 6 of BKLa, between Itti-ili-nibi and Damqi-ilishu, which might be a reference to a king between them, as the same sign later in the list has been seen by some scholars as evidence of an attestation of another unknown king, attested in the Synchronistic King List but unattested in other sources.[75]

- ^ Name not preserved.[75]

- ^ Omitted in Babylonian King Lists A and B, only being included in the Synchronistic King List. The reading of the signs making up his name is not certain.[73] The issue derives from the poor quality early photographs of the tablet and its subsequent deteriorating condition. The presence of the sign AŠ between lines 10 and 11 of BKLa, between Gulkishar and Peshgaldaramesh might be a reference to a king between them.[75] Given that he only appears in one source, and BKLa states that there were 11 kings of this dynasty, his existence is not certain. Perhaps he was a real king who reigned very briefly.[75]

- ^ Babylonian King List A adds a king between Kashtiliash I and Abi-Rattash, but the list is damaged and the name is not preserved. The Synchronistic King List omits this figure.[79]

- ^ Name not preserved.[79]

- ^ One possible reading of an inscription by Agum II indicates that Abi-Rattash was an ancestor of Agum II’s father Urzigurumash.[81]

- ^ As Agum II explicitly refers to Urzigurumash as his father in his own inscriptions, Beaulieu (2018) placed him as Urzigurumash’s direct successor.[79] Chen (2020) placed him later, as the direct predecessor of Burnaburiash I.[66]

- ^ There being a king between Shipta’ulzi and Burnaburiash I is indicated by both Babylonian King List A and the Synchronistic King List, but as both texts are damaged, neither list preserves the name of this ruler. Historically, the fragments left have been interpreted as suggesting that this king’s name was Agum, but this reading has been abandoned by modern scholars.[79]

- ^ Name not preserved.[79]

- ^ Kadashman-Sah does not appear in king lists. The only evidence of his existence are tablets that are dated to the reign of ‘Agum and Kadashman-Sah’, suggesting that he was a king, and that there was some form of co-rulership. It is possible that he was a transitional ruler with only local power.[85]

- ^ There are no sources that directly indicate a familial connection between Kadashman-Enlil I and Kurigalzu I, but Kadashman-Enlil I’s presumed son, Burnaburiash II, refers to Kurigalzu I as his ancestor in a letter.[88]

- ^ a b c Kashtiliash IV was deposed by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I c. 1225 BC. The Bablyonian Chronicles describe Tukulti-Ninurta I as destroying Babylon’s walls and incorporating the city into his empire for seven years until the Babylonians rebelled and placed Kashtiliash IV’s son, Adad-shuma-usur, on the throne. Babylonian King List A contradicts this, listing three rulers between Kashtiliash IV and Adad-shuma-usur. As the reigns of these three kings add up to just a little less than seven years, scholars have historically interpreted this to mean that these three kings were appointed vassals of Tukulti-Ninurta I. The Babylonian Chronicles seem to suggest that Adad-shuma-usur ruled in the south of Bablyonia concurrently with Tukulti-Ninurta controlling the north (and Babylon itself). Beaulieu (2018) suggests the possibility that these three kings were contemporary rivals, rather than successors of one another, and that Adad-shuma-usur did succeed Kashtiliash IV directly, but only in the south, and only took control of Babylon late in his reign.[89]

- ^ A family link between Ninurta-nadin-shumi and his immediate predecessors cannot be proven from the sources, but the only definitely attested break in family succession to the throne in this dynasty was the accession of Adad-apla-iddina, who is explicitly designated as an usurper in the sources.[92]

- ^ Marduk-shapik-zeri was once believed to be attested as Marduk-nadin-ahhe’s son, but the reading of the relevant text is uncertain–it cannot be proven, or disproven, that Marduk-shapik-zeri was Marduk-nadin-ahhe’s son.[93] The only definitely attested break in family succession to the throne in this dynasty was the accession of Adad-apla-iddina, who is explicitly designated as an usurper in the sources.[92]

- ^ The name of this king has not survived in its complete form in any source. The ‘X’ in his name was inserted by modern historians to mark the missing portion. The reading of the second element of his name, zēra, is not fully certain. According to Brinkman (1968), there are many possibilities for what the full name was (based on known Babylonian names with the same first two elements), including: Marduk-zēra-ibni, Marduk-zēra-iddina, Marduk-zēra-iqīša, Marduk-zēra-uballiṭ, Marduk-zēra-ukīn, Marduk-zēra-uṣur, Marduk-zēra-ušallim and Marduk-zēra-līšir.[95]

- ^ a b Shamash-mudammiq is described as having been defeated by the Assyrian king Adad-nirari II c. 901 BC.[101]

- ^ a b c d Beaulieu (2018) states that Nabu-apla-iddina’s 31st year as king was c. 855 BC.[101] Chen (2020) ascribes Nabu-apla-iddina a 33-year reign.[66]

- ^ a b c Chen (2020) ascribes Marduk-zakir-shumi I a 27-year reign.[66]

- ^ a b c Marduk-balassu-iqbi was deposed by the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad V in 813 BC. Less than a year later, in 812 BC, Shamshi-Adad deposed Marduk-balassu-iqbi’s successor, Baba-aha-iddina.[102]

- ^ After Baba-aha-iddina was taken to Assyria as a captive by the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad V in 812 BC, Babylonia entered into an interregnum lasting several (at least four) years, which the chronicles describe as a period when there was «no king in the land». The chief claimants to royal power in Babylonia at this time was the Assyrians. Though they did not claim the title ‘king of Babylon’, Shamshi-Adad V took the title ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’ after his victory in 812 BC and Shamshi-Adad’s son and successor, Adad-nirari III, claimed that ‘all the kings of Chaldea’ were his vassals and that he had received tribute, as well as sacrificial meals (a Babylonian royal prerogative) at Babylon. The Babylonian crown had thus, at least nominally, been taken over by the Assyrians, though as Assyria was in a weakened state its kings were unable to fully exploit the situation.[103]

- ^ Some of the Chaldean tribes during this time also either claimed royal Babylonian power, or asserted their own independence. A seal from the time of the interregnum depicts the chief of the Bit-Yakin tribe (and father of the later king Eriba-Marduk), Marduk-shakin-shumi, in the traditional Babylonian royal garbs. There is also a contract tablet known that describes a weight being sent to the ‘palace of Nabu-shumu-lishir, descendant of Dakkuru’. Nabu-shumu-lishir of the Bit-Dakkuri tribe’s claim to reside in a ‘palace’ was equivalent to claiming to be a king.[103]

- ^ Ninurta-apla-X is only known from Babylonian King List A, where his name is broken off and incompletely preserved. The ‘X’ in his name was inserted by modern historians to mark the missing portion.[104][105] The second element of the name, apla, is not a fully certain reading.[105] According to Brinkman (1968), the full name might have been Ninurta-apla-uṣur or something similar.[105]

- ^ a b c d Beaulieu (2018) writes that Eriba-Marduk’s ninth and last year as king was c. 760 BC.[106]

- ^ Recognising Sennacherib as the king of Babylon from 689 to 681 BC is the norm in modern lists of Babylonian kings.[110] Babylon was destroyed at this time and many contemporary Babylonian documents, such as chronicles, refer to Sennacherb’s second reign in Babylonia as a «kingless period» without a king in the land.[111] Babylonian King List A nevertheless includes Sennacherib as the king of this period, listing his second reign as taking place between the downfall of Mushezib-Marduk and the accession of Esarhaddon.[112]

- ^ Though Shamash-shum-ukin was the legitimate successor of Esarhaddon to the Babylonian throne, appointed by his father, he was not formally invested as such until the spring after his father’s death. Lists of kings of Babylon by modern historians typically regard Ashurbanipal, Esarhaddon’s successor in Assyria, as the ruler of Babylon during this brief ‘interregnum’.[110] The Uruk King List lists Ashurbanipal as Shamash-shum-ukin’s predecessor, but also lists him as ruling simultaneously with his brother, giving his reign as 669–647 BC.[115] In contrast, Babylonian King List A omits Ashurbanipal entirely, listing Shamash-shum-ukin as the direct successor of Esarhaddon, and Kandalanu as the direct successor of Shamash-shum-ukin.[112]

- ^ Ashurbanipal is again not recorded by the Babylonian King List A as ruler between Shamash-shum-ukin and Kandalanu,[112] and is not recorded as such in lists by modern historians either.[110] Ashurbanipal did however rule Babylonia from the defeat of Shamash-shum-ukin in the summer of 648 BC to Kandalanu’s appointment in 647 BC. Date formulae from Babylonia during this time are dated to Ashurbanipal’s rule, and indicate that the transfer of power to Kandalanu was gradual. Tablets were still dated to Ashurbanipal around the end of 647 BC at Borsippa, and as late as the spring of 646 BC at Dilbat. After 646 BC, tablets in Babylonia are exclusively dated to Kandalanu’s reign.[116]