«Insta» redirects here. For the food delivery service, see Instacart. For the song by Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike, see Instagram (song).

|

||||

| Original author(s) |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Meta Platforms | |||

| Initial release | October 6, 2010; 12 years ago | |||

| Preview release(s) [±] | ||||

|

||||

| Operating system |

|

|||

| Size | 231.3 MB (iOS)[2] 50.22 MB (Android)[3] 50.3 MB (Fire OS) [4] |

|||

| Available in | 32[5] languages | |||

|

List of languages

|

||||

| License | Proprietary software with Terms of Use | |||

| Website | instagram.com |

Instagram[a] is a photo and video sharing social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. The app allows users to upload media that can be edited with filters and organized by hashtags and geographical tagging. Posts can be shared publicly or with preapproved followers. Users can browse other users’ content by tag and location, view trending content, like photos, and follow other users to add their content to a personal feed.[7]

Instagram was originally distinguished by allowing content to be framed only in a square (1:1) aspect ratio of 640 pixels to match the display width of the iPhone at the time. In 2015, this restriction was eased with an increase to 1080 pixels. It also added messaging features, the ability to include multiple images or videos in a single post, and a Stories feature—similar to its main competitor Snapchat—which allowed users to post their content to a sequential feed, with each post accessible to others for 24 hours. As of January 2019, Stories is used by 500 million people daily.[7]

Originally launched for iOS in October 2010 by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, Instagram rapidly gained popularity, with one million registered users in two months, 10 million in a year, and 1 billion by June 2018.[8] In April 2012, Facebook Inc. acquired the service for approximately US$1 billion in cash and stock. The Android version was released in April 2012, followed by a feature-limited desktop interface in November 2012, a Fire OS app in June 2014, and an app for Windows 10 in October 2016. As of October 2015, over 40 billion photos had been uploaded. Although often admired for its success and influence, Instagram has also been criticized for negatively affecting teens’ mental health, its policy and interface changes, its alleged censorship, and illegal and inappropriate content uploaded by users.

History

Instagram icon from 2016 to 2022, when it was updated to include even more saturated colors

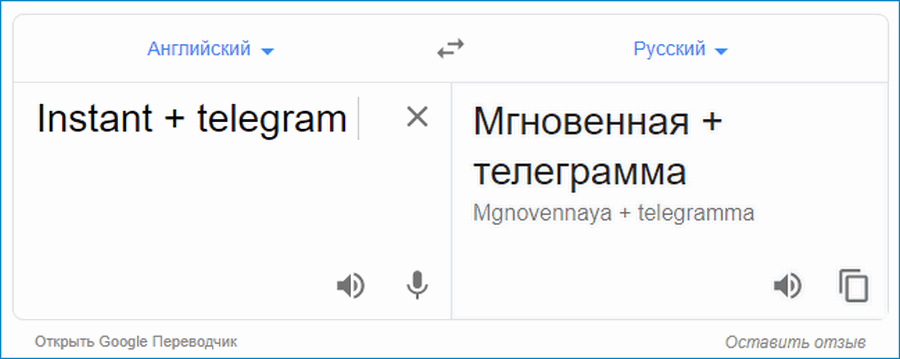

Instagram began development in San Francisco as Burbn, a mobile check-in app created by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger.[9] Realizing that it was too similar to Foursquare, they refocused their app on photo-sharing, which had become a popular feature among its users.[10][11] They renamed it Instagram, a portmanteau of «instant camera» and «telegram».[12]

2010–2011: Beginnings and major funding

On March 5, 2010, Systrom closed a $500,000 seed funding round with Baseline Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz while working on Burbn.[13] Josh Riedel joined the company in October as Community Manager,[14] Shayne Sweeney joined in November as an engineer,[14] and Jessica Zollman joined as a Community Evangelist in August 2011.[14][15]

The first Instagram post was a photo of South Beach Harbor at Pier 38, posted by Mike Krieger at 5:26 p.m. on July 16, 2010.[16][11] Systrom shared his first post, a picture of a dog and his girlfriend’s foot, a few hours later at 9:24 p.m. It has been wrongly attributed as the first Instagram photo due to the earlier letter of the alphabet in its URL.[17][18][better source needed] On October 6, 2010, the Instagram iOS app was officially released through the App Store.[19]

In February 2011, it was reported that Instagram had raised $7 million in Series A funding from a variety of investors, including Benchmark Capital, Jack Dorsey, Chris Sacca (through Capital fund), and Adam D’Angelo.[20] The deal valued Instagram at around $20 million.[21] In April 2012, Instagram raised $50 million from venture capitalists with a $500 million valuation.[22] Joshua Kushner was the second largest investor in Instagram’s Series B fundraising round, leading his investment firm, Thrive Capital, to double its money after the sale to Facebook.[23]

2012–2014: Additional platforms and acquisition by Facebook

On April 3, 2012, Instagram released a version of its app for Android phones,[24][25] and it was downloaded more than one million times in less than one day.[26] The Android app has since received two significant updates: first, in March 2014, which cut the file size of the app by half and added performance improvements;[27][28] then in April 2017, to add an offline mode that allows users to view and interact with content without an Internet connection. At the time of the announcement, it was reported that 80% of Instagram’s 600 million users were located outside the U.S., and while the aforementioned functionality was live at its announcement, Instagram also announced its intention to make more features available offline, and that they were «exploring an iOS version».[29][30][31]

On April 9, 2012, Facebook, Inc. bought Instagram for $1 billion in cash and stock,[32][33][34] with a plan to keep the company independently managed.[35][36][37] Britain’s Office of Fair Trading approved the deal on August 14, 2012,[38] and on August 22, 2012, the Federal Trade Commission in the U.S. closed its investigation, allowing the deal to proceed.[39] On September 6, 2012, the deal between Instagram and Facebook officially closed with a purchase price of $300 million in cash and 23 million shares of stock.[40]

The deal closed just before Facebook’s scheduled initial public offering according to CNN.[37] The deal price was compared to the $35 million Yahoo! paid for Flickr in 2005.[37] Mark Zuckerberg said Facebook was «committed to building and growing Instagram independently.»[37] According to Wired, the deal netted Systrom $400 million.[41]

In November 2012, Instagram launched website profiles, allowing anyone to see user feeds from a web browser with limited functionality,[42] as well as a selection of badges, web widget buttons to link to profiles.[43]

Since the app’s launch it had used the Foursquare API technology to provide named location tagging. In March 2014, Instagram started to test and switch the technology to use Facebook Places.[44][45]

2015–2017: Redesign and Windows app

Instagram headquarters in Menlo Park

In June 2015, the desktop website user interface was redesigned to become more flat and minimalistic, but with more screen space for each photo and to resemble the layout of Instagram’s mobile website.[46][47][48] Furthermore, one row of pictures only has three instead of five photos to match the mobile layout. The slideshow banner[49][50] on the top of profile pages, which simultaneously slide-showed seven picture tiles of pictures posted by the user, alternating at different times in a random order, has been removed. In addition, the formerly angular profile pictures became circular.

In April 2016, Instagram released a Windows 10 Mobile app, after years of demand from Microsoft and the public to release an app for the platform.[51][52] The platform previously had a beta version of Instagram, first released on November 21, 2013, for Windows Phone 8.[53][54][55] The new app added support for videos (viewing and creating posts or stories, and viewing live streams), album posts and direct messages.[56] Similarly, an app for Windows 10 personal computers and tablets was released in October 2016.[57][58] In May, Instagram updated its mobile website to allow users to upload photos, and to add a «lightweight» version of the Explore tab.[59][60]

On May 11, 2016, Instagram revamped its design, adding a black-and-white flat design theme for the app’s user interface, and a less skeuomorphistic, more abstract, «modern» and colorful icon.[61][62][63] Rumors of a redesign first started circulating in April, when The Verge received a screenshot from a tipster, but at the time, an Instagram spokesperson simply told the publication that it was only a concept.[64]

On December 6, 2016, Instagram introduced comment liking. However, unlike post likes, the user who posted a comment does not receive notifications about comment likes in their notification inbox. Uploaders can optionally decide to deactivate comments on a post.[65][66][67]

The mobile web front end allows uploading pictures since May 4, 2017. Image filters and the ability to upload videos were not introduced then.[68][69]

On April 30, 2019, the Windows 10 Mobile app was discontinued, though the mobile website remains available as a progressive web application (PWA) with limited functionality. The app remains available on Windows 10 computers and tablets, also updated to a PWA in 2020.

2018–2019: IGTV, removal of the like counter, management changes

To comply with the GDPR regulations regarding data portability, Instagram introduced the ability for users to download an archive of their user data in April 2018.[70][71][72]

IGTV launched on June 20, 2018, as a standalone video application.

On September 24, 2018, Krieger and Systrom announced in a statement they would be stepping down from Instagram.[73][74] On October 1, 2018, it was announced that Adam Mosseri would be the new head of Instagram.[75][76][77]

During Facebook F8, it was announced that Instagram would, beginning in Canada, pilot the removal of publicly-displayed «like» counts for content posted by other users.[78] Like counts would only be visible to the user who originally posted the content. Mosseri stated that this was intended to have users «worry a little bit less about how many likes they’re getting on Instagram and spend a bit more time connecting with the people that they care about.»[79][80] It has been argued that low numbers of likes in relativity to others could contribute to a lower self-esteem in users.[80][78] The pilot began in May 2019, and was extended to 6 other markets in July.[80][81] The pilot was expanded worldwide in November 2019.[82] Also in July 2019, Instagram announced that it would implement new features designed to reduce harassment and negative comments on the service.[83]

In August 2019, Instagram also began to pilot the removal of the «Following» tab from the app, which had allowed users to view a feed of the likes and comments made by users they follow. The change was made official in October, with head of product Vishal Shah stating that the feature was underused and that some users were «surprised» when they realized their activity was being surfaced in this manner.[84][85]

In October 2019, Instagram introduced a limit on the number of posts visible in page scrolling mode unless logged in. Until this point, public profiles had been available to all users, even when not logged in. Following the change, after viewing a number of posts a pop-up requires the user to log in to continue viewing content.[86][87][88]

2020–present: New features

In March 2020, Instagram launched a new feature called «Co-Watching». The new feature allows users to share posts with each other over video calls. According to Instagram, they pushed forward the launch of Co-Watching in order to meet the demand for virtually connecting with friends and family due to social distancing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[89]

In August 2020, Instagram began a pivot to video, introducing a new feature called «Reels».[90][91][92] The intent was to compete with the video-sharing site TikTok.[92][93][90] Instagram also added suggested posts in August 2020. After scrolling through posts from the past 48 hours, Instagram displays posts related to their interests from accounts they do not follow.[94]

In February 2021, Instagram began testing a new feature called Vertical Stories, said by some sources to be inspired by TikTok.[95] The same month, they also began testing the removal of ability to share feed posts to stories.[96]

In March 2021, Instagram launched a new feature in which four people can go live at once.[97] Instagram also announced that adults would not be allowed to message teens who don’t follow them as part of a series of new child safety policies.[98][99][100][101]

In May 2021, Instagram began allowing users in some regions to add pronouns to their profile page.[102][103]

On October 4, 2021, Facebook had its worst outage since 2008. The outage also affected other platforms owned by Facebook, such as Instagram and WhatsApp.[104][105] Security experts identified the problem as possibly being DNS-related.[106]

On March 17, 2022, Zuckerberg confirmed plans to add non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to the platform.[107]

Features and tools

An original photograph (left) is automatically cropped to a square by Instagram, and has a filter added at the selection of the user (right).

A photo collage of an unprocessed image (top left) modified with the 16 different Instagram filters available in 2011

Users can upload photographs and short videos, follow other users’ feeds,[108] and geotag images with the name of a location.[109] Users can set their account as «private», thereby requiring that they approve any new follower requests.[110] Users can connect their Instagram account to other social networking sites, enabling them to share uploaded photos to those sites.[111] In September 2011, a new version of the app included new and live filters, instant tilt–shift, high-resolution photographs, optional borders, one-click rotation, and an updated icon.[112][113] Photos were initially restricted to a square, 1:1 aspect ratio; since August 2015, the app supports portrait and widescreen aspect ratios as well.[114][115][116] Users could formerly view a map of a user’s geotagged photos. The feature was removed in September 2016, citing low usage.[117][118]

Since December 2016, posts can be «saved» into a private area of the app.[119][120] The feature was updated in April 2017 to let users organize saved posts into named collections.[121][122] Users can also «archive» their posts in a private storage area, out of visibility for the public and other users. The move was seen as a way to prevent users from deleting photos that don’t garner a desired number of «likes» or are deemed boring, but also as a way to limit the «emergent behavior» of deleting photos, which deprives the service of content.[123][124] In August, Instagram announced that it would start organizing comments into threads, letting users more easily interact with replies.[125][126]

Since February 2017, up to ten pictures or videos can be included in a single post, with the content appearing as a swipeable carousel.[127][128] The feature originally limited photos to the square format, but received an update in August to enable portrait and landscape photos instead.[129][130]

In April 2018, Instagram launched its version of a portrait mode called «focus mode,» which gently blurs the background of a photo or video while keeping the subject in focus when selected.[131] In November, Instagram began to support Alt text to add descriptions of photos for the visually impaired. They are either generated automatically using object recognition (using existing Facebook technology) or manually specified by the uploader.[132]

On March 1, 2021, Instagram launched a new feature named Instagram Live «Rooms» Let Four People Go Live Together.[133]

In May 2021, Instagram announced a new accessibility feature for videos on Instagram Reels and Stories to allow creators to place closed captions on their content.[134]

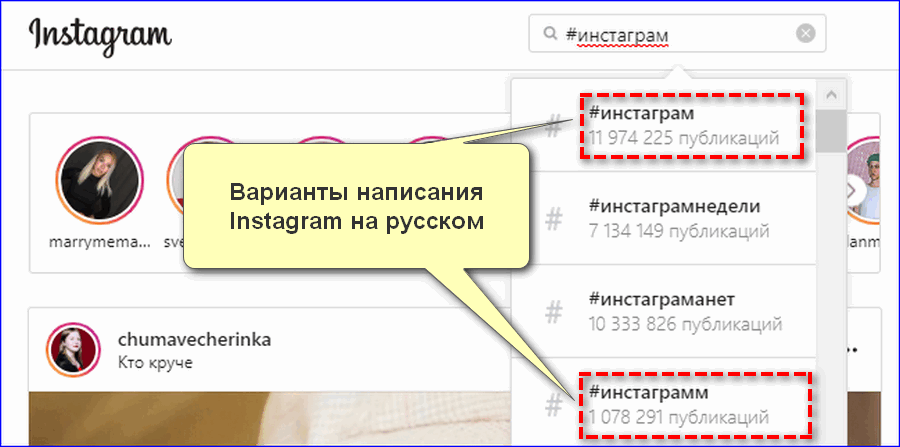

Hashtags

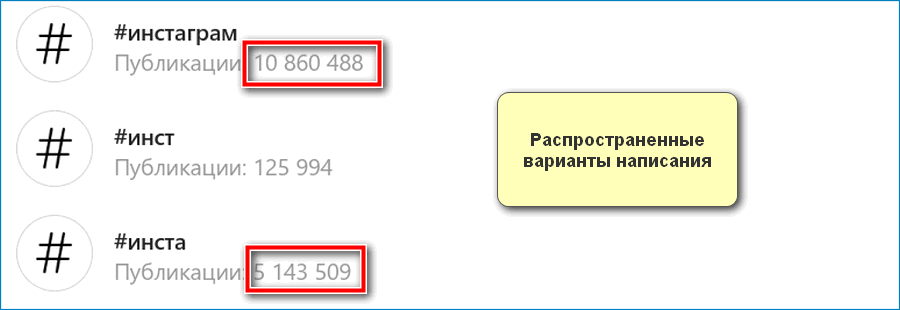

In January 2011, Instagram introduced hashtags to help users discover both photos and each other.[135][136] Instagram encourages users to make tags both specific and relevant, rather than tagging generic words like «photo», to make photographs stand out and to attract like-minded Instagram users.[137]

Users on Instagram have created «trends» through hashtags. The trends deemed the most popular on the platform often highlight a specific day of the week to post the material on. Examples of popular trends include #SelfieSunday, in which users post a photo of their faces on Sundays; #MotivationMonday, in which users post motivational photos on Mondays; #TransformationTuesday, in which users post photos highlighting differences from the past to the present; #WomanCrushWednesday, in which users post photos of women they have a romantic interest in or view favorably, as well as its #ManCrushMonday counterpart centered on men; and #ThrowbackThursday, in which users post a photo from their past, highlighting a particular moment.[138][139]

In December 2017, Instagram began to allow users to follow hashtags, which display relevant highlights of the topic in their feeds.[140][141]

Explore

In June 2012, Instagram introduced «Explore», a tab inside the app that displays popular photos, photos taken at nearby locations, and search.[142] The tab was updated in June 2015 to feature trending tags and places, curated content, and the ability to search for locations.[143] In April 2016, Instagram added a «Videos You Might Like» channel to the tab,[144][145] followed by an «Events» channel in August, featuring videos from concerts, sports games, and other live events,[146][147] followed by the addition of Instagram Stories in October.[148][149] The tab was later expanded again in November 2016 after Instagram Live launched to display an algorithmically curated page of the «best» Instagram Live videos currently airing.[150] In May 2017, Instagram once again updated the Explore tab to promote public Stories content from nearby places.[151]

Photographic filters

Instagram offers a number of photographic filters that users can apply to their images. In February 2012, Instagram added a «Lux» filter, an effect that «lightens shadows, darkens highlights and increases contrast».[152][153] In December 2014, Slumber, Crema, Ludwig, Aden, and Perpetua were five new filters to be added to the Instagram filter family.[154]

Video

Initially a purely photo-sharing service, Instagram incorporated 15-second video sharing in June 2013.[155][156] The addition was seen by some in the technology media as Facebook’s attempt at competing with the then-popular video-sharing application Vine.[157][158] In August 2015, Instagram added support for widescreen videos.[159][160] In March 2016, Instagram increased the 15-second video limit to 60 seconds.[161][162] Albums were introduced in February 2017, which allow up to 10 minutes of video to be shared in one post.[127][128][163]

IGTV

Main article: IGTV

IGTV is a vertical video application launched by Instagram[164] in June 2018. Basic functionality is also available within the Instagram app and website. IGTV allows uploads of up to 10 minutes in length with a file size of up to 650 MB, with verified and popular users allowed to upload videos of up to 60 minutes in length with a file size of up to 5.4 GB.[165] The app automatically begins playing videos as soon as it is launched, which CEO Kevin Systrom contrasted to video hosts where one must first locate a video.[166][167][168]

Reels

In November 2019, it was reported that Instagram had begun to pilot a new video feature known as «Reels» in Brazil, expanding to France and Germany afterwards.[169] It is similar in functionality to the Chinese video-sharing service TikTok, with a focus on allowing users to record short videos set to pre-existing sound clips from other posts.[170] Users could make up to 15 (later 30) second videos using this feature.[171] Reels also integrates with existing Instagram filters and editing tools.[165]

In July 2020, Instagram rolled out Reels to India after TikTok was banned in the country.[172] The following month, Reels officially launched in 50 countries including the United States, Canada and United Kingdom.[173] Instagram has recently introduced a reel button on home page.[174]

On June 17, 2021, Instagram launched full-screen advertisements in Reels. The ads are similar to regular reels and can run up to 30 seconds. They are distinguished from regular content by the «sponsored» tag under the account name.[175]

Instagram Direct

In December 2013, Instagram announced Instagram Direct, a feature that lets users interact through private messaging. Users who follow each other can send private messages with photos and videos, in contrast to the public-only requirement that was previously in place. When users receive a private message from someone they don’t follow, the message is marked as pending and the user must accept to see it. Users can send a photo to a maximum of 15 people.[176][177][178] The feature received a major update in September 2015, adding conversation threading and making it possible for users to share locations, hashtag pages, and profiles through private messages directly from the news feed. Additionally, users can now reply to private messages with text, emoji or by clicking on a heart icon. A camera inside Direct lets users take a photo and send it to the recipient without leaving the conversation.[179][180][181] A new update in November 2016 let users make their private messages «disappear» after being viewed by the recipient, with the sender receiving a notification if the recipient takes a screenshot.[182][183]

In April 2017, Instagram redesigned Direct to combine all private messages, both permanent and ephemeral, into the same message threads.[184][185][186] In May, Instagram made it possible to send website links in messages, and also added support for sending photos in their original portrait or landscape orientation without cropping.[187][188]

In April 2020, Direct became accessible from the Instagram website, allowing users to send direct messages from a web version using WebSocket technology.[189]

In August 2020, Facebook started merging Instagram Direct into Facebook Messenger. After the update (which is rolled out to a segment of the user base) the Instagram Direct icon transforms into Facebook Messenger icon.[190]

In March 2021, a feature was added that prevents adults from messaging users under 18 who do not follow them as part of a series of new child safety policies.[98][99][100]

Instagram Stories

In August 2016, Instagram launched Instagram Stories, a feature that allows users to take photos, add effects and layers, and add them to their Instagram story. Images uploaded to a user’s story expire after 24 hours. The media noted the feature’s similarities to Snapchat.[191][192] In response to criticism that it copied functionality from Snapchat, CEO Kevin Systrom told Recode that «Day One: Instagram was a combination of Hipstamatic, Twitter [and] some stuff from Facebook like the ‘Like’ button. You can trace the roots of every feature anyone has in their app, somewhere in the history of technology». Although Systrom acknowledged the criticism as «fair», Recode wrote that «he likened the two social apps’ common features to the auto industry: Multiple car companies can coexist, with enough differences among them that they serve different consumer audiences». Systrom further stated that «When we adopted [Stories], we decided that one of the really annoying things about the format is that it just kept going and you couldn’t pause it to look at something, you couldn’t rewind. We did all that, we implemented that.» He also told the publication that Snapchat «didn’t have filters, originally. They adopted filters because Instagram had filters and a lot of others were trying to adopt filters as well.»[193][194]

In November, Instagram added live video functionality to Instagram Stories, allowing users to broadcast themselves live, with the video disappearing immediately after ending.[195][150]

In January 2017, Instagram launched skippable ads, where five-second photo and 15-second video ads appear in-between different stories.[196][197][198]

In April 2017, Instagram Stories incorporated augmented reality stickers, a «clone» of Snapchat’s functionality.[199][200][198]

In May 2017, Instagram expanded the augmented reality sticker feature to support face filters, letting users add specific visual features onto their faces.[201][202]

Later in May, TechCrunch reported about tests of a Location Stories feature in Instagram Stories, where public Stories content at a certain location are compiled and displayed on a business, landmark or place’s Instagram page.[203] A few days later, Instagram announced «Story Search», in which users can search for geographic locations or hashtags and the app displays relevant public Stories content featuring the search term.[151][204]

In June 2017, Instagram revised its live-video functionality to allow users to add their live broadcast to their story for availability in the next 24 hours, or discard the broadcast immediately.[205] In July, Instagram started allowing users to respond to Stories content by sending photos and videos, complete with Instagram effects such as filters, stickers, and hashtags.[206][207]

Stories were made available for viewing on Instagram’s mobile and desktop websites in late August 2017.[208][209]

On December 5, 2017, Instagram introduced «Story Highlights»,[210] also known as «Permanent Stories», which are similar to Instagram Stories, but don’t expire. They appear as circles below the profile picture and biography and are accessible from the desktop website as well.

In June 2018, the daily active story users of Instagram had reached 400 million users, and monthly active users had reached 1 billion active users.[211]

Advertising

Emily White joined Instagram as Director of Business Operations in April 2013.[212][213] She stated in an interview with The Wall Street Journal in September 2013 that the company should be ready to begin selling advertising by September 2014 as a way to generate business from a popular entity that had not yet created profit for its parent company.[214] White left Instagram in December 2013 to join Snapchat.[215][216] In August 2014, James Quarles became Instagram’s Global Head of Business and Brand Development, tasked with overseeing advertisement, sales efforts, and developing new «monetization products», according to a spokesperson.[217]

In October 2013, Instagram announced that video and image ads would soon appear in feeds for users in the United States,[218][219] with the first image advertisements displaying on November 1, 2013.[220][221] Video ads followed nearly a year later on October 30, 2014.[222][223] In June 2014, Instagram announced the rollout of ads in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia,[224] with ads starting to roll out that autumn.[225]

In March 2015, Instagram announced it would implement «carousel ads,» allowing advertisers to display multiple images with options for linking to additional content.[226][227] The company launched carousel image ads in October 2015,[228][229] and video carousel ads in March 2016.[230]

In February 2016, Instagram announced that it had 200,000 advertisers on the platform.[231] This number increased to 500,000 by September 2016,[232] and 1 million in March 2017.[233][234]

In May 2016, Instagram launched new tools for business accounts, including business profiles, analytics and the ability to promote posts as ads. To access the tools, businesses had to link a corresponding Facebook page.[235] The new analytics page, known as Instagram Insights, allowed business accounts to view top posts, reach, impressions, engagement and demographic data.[235] Insights rolled out first in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, and expanded to the rest of the world later in 2016.[236][235][237]

In November 2018, Instagram added the ability for business accounts to add product links directing users to a purchase page or to save them to a «shopping list.»[238] In April 2019, Instagram added the option to «Checkout on Instagram,» which allows merchants to sell products directly through the Instagram app.[239]

In March 2020, via a blog post, Instagram announced that they are making major moderation changes in order to decrease the flow of disinformation, hoaxes and fake news regarding COVID-19 on its platform, «We’ll remove COVID-19 accounts from account recommendations, and we are working to remove some COVID-19 related content from Explore unless posted by a credible health organization. We will also start to downrank content in feed and Stories that has been rated false by third-party fact-checkers.»[240]

In June 2021, Instagram launched a native affiliate marketing tool creators can use to earn commissions based on sales. Commission-enabled posts are labeled «Eligible for Commission» on the user side to identify them as affiliate posts. Launch partners included Sephora, MAC, and Kopari.[241]

Stand-alone apps

Instagram has developed and released three stand-alone apps with specialized functionality. In July 2014, it released Bolt, a messaging app where users click on a friend’s profile photo to quickly send an image, with the content disappearing after being seen.[242][243] It was followed by the release of Hyperlapse in August, an iOS-exclusive app that uses «clever algorithm processing» to create tracking shots and fast time-lapse videos.[244][245] Microsoft launched a Hyperlapse app for Android and Windows in May 2015, but there has been no official Hyperlapse app from Instagram for either of these platforms to date.[246] In October 2015, it released Boomerang, a video app that combines photos into short, one-second videos that play back-and-forth in a loop.[247][248]

Third-party services

The popularity of Instagram has led to a variety of third-party services designed to integrate with it, including services for creating content to post on the service and generating content from Instagram photos (including physical print-outs), analytics, and alternative clients for platforms with insufficient or no official support from Instagram (such as in the past, iPads).[249][250]

In November 2015, Instagram announced that effective June 1, 2016, it would end «feed» API access to its platform in order to «maintain control for the community and provide a clear roadmap for developers» and «set up a more sustainable environment built around authentic experiences on the platform», including those oriented towards content creation, publishers, and advertisers. Additionally, third-party clients have been prohibited from using the text strings «insta» or «gram» in their name.[251] It was reported that these changes were primarily intended to discourage third-party clients replicating the entire Instagram experience (due to increasing monetization of the service), and security reasons (such as preventing abuse by automated click farms, and the hijacking of accounts). In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Instagram began to impose further restrictions on its API in 2018.[250][252][253]

For unlimited browsing of public Instagram profiles without having to create an account, as well as for anonymous browsing of someone else’s Stories, has to use the Instagram profiles viewer.[254] Stories are more authentic than typical photos posted as posts because users know that in 24 hours their Stories will disappear if they don’t add them as highlighted[255] (however users can check who saw their Story for 48 hours after it was published[256]). For this reason, they are very valuable for market research.[257]

Fact checking

On December 16, 2019, Facebook announced it would expand its fact checking programs towards Instagram,[258] by using third-party fact-checkers organizations false information is able to be identified, reviewed and labeled as false information. Content when rated as false or partly false is removed from the explore page and hashtag pages, additionally content rated as false or partly false are labeled as such. With the addition of Facebook fact-checking program came the use of image matching technology to find further instances of misinformation. If a piece of content is labeled false or partly false on Facebook or Instagram then duplicates of such content will also be labeled as false.[259]

Algorithm and design changes

In April 2016, Instagram began rolling out a change to the order of photos visible in a user’s timeline, shifting from a strictly chronological order to one determined by an algorithm.[260] Instagram said the algorithm was designed so that users would see more of the photos by users that they liked,[261] but there was significant negative feedback, with many users asking their followers to turn on post notifications in order to make sure they see updates.[262][263][264] The company wrote a tweet to users upset at the prospect of the change, but did not back down,[265] nor provide a way to change it back, which they re-affirmed in 2020.[266][267] However, in December 2021, Adam Mosseri, in a Senate hearing on child safety issues, stated that the company is developing a version of the feed that would show user posts in chronological order.[268] He later clarified the company would introduce two modes: a classic chronological feed and a version of it that would let users pick «favorite» users whose posts would be shown at the top in chronological order while other posts would be mixed in below.[269]

Since 2017, Instagram has employed the ability to reduce the prominence of accounts («shadowbanning») it believes may be generating non-genuine engagement and spam (including excessive use of unneeded hashtags), preventing posts from appearing in search results and in the app’s Explore section. In a now-deleted Facebook post, Instagram wrote that «When developing content, we recommend focusing on your business objective or goal rather than hashtags».[270][271] Instagram has since been accused of extending the practice to censor posts under vague and inconsistent circumstances, particularly in regards to sexually suggestive material.[272]

Instagram caused the userbase to fall into outrage with the December 2018 update.[273][274][275][276][277][excessive citations] They found an attempt to alter the flow of the feed from the traditional vertical scroll to emulate and piggy-back the popularity of their Instagram Stories with a horizontal scroll, by swiping left.[278] Various backtracking statements were released explaining it as a bug, or as a test release that had been accidentally deployed to too large an audience.[276][275]

In November 2020, Instagram replaced the activity feed tab with a new «Shop» tab, moving the activity feed to the top. The «new post» button was also relocated to the top and replaced with a Reels tab[279] The company states that «the Shop tab gives you a better way to connect with brands and creators and discover products you love» and the Reels tab «makes it easier for you to discover short, fun videos from creators all over the world and people just like you.»[280] However, users have not responded well to the change, taking their complaints to Twitter and Reddit, and The New York Times has shunned Reels in particular, saying «Not only does Reels fail in every way as a TikTok clone, but it’s confusing, frustrating and impossible to navigate».[281]

Also in 2020, Instagram rolled out a feature titled «suggested posts», which adds posts from accounts Instagram thinks a user would like to such user’s feed.[282] The feature was met with controversy from both Reddit users[283] from The Verge, which reported that suggested posts would keep users glued to their feed, give Instagram more advertising space, and ultimately harm the mental health of users, while Instagram executive Julian Gutman rebutted, stating the feature was not intended to keep users glued to their screens.[284] Suggested posts received more controversy after Fast Company stated that the feature would be impossible to turn off.[285]

On June 23, 2021, Instagram announced a test change to the «suggested posts» feature. The company will put suggested posts ahead of posts from people that the user is following in the Instagram feed, citing positive reception as the reason for this change.[286]

Scientific studies

Harmful effect on teenage girls’ mental health

Facebook has known for years that its Instagram app is harmful to a number of teenagers, according to research seen by The Wall Street Journal, but the company concealed the knowledge from lawmakers.[287] The internal Facebook presentations seen by the Journal in 2021 show that Instagram is toxic to a sizable percentage of its users, particularly teenage girls. More than 40% of Instagram’s users are under 23 years old. The presentations were seen by the company’s executives and the findings mentioned to Mark Zuckerberg in 2020, but when asked in March 2021 about Instagram’s effect on young people, Zuckerberg defended the company’s plan to launch an Instagram product for children under 13.[287] When asked by senators for its internal findings on the impact of Instagram on youth mental health, Facebook sent a six-page letter that did not include the company’s research. The company told Forbes that its research is «kept confidential to promote frank and open dialogue and brainstorming internally.»[288] In a blog post, Instagram said that the WSJ story «focuses on a limited set of findings and casts them in a negative light.»[289] On September 27, 2021, weeks after the WSJ report was released, Facebook announced that it had «paused» development of Instagram Kids, the Instagram product aimed at children. The company stated it was looking into concerns raised by the regulators and parents. Adam Mosseri stated that the company would return to the project as «[t]he reality is that kids are already online, and we believe that developing age-appropriate experiences designed specifically for them is far better for parents than where we are today.»[290][291] Based on Facebook’s leaked internal research, Instagram has had negative effects on the body image of one in three teenagers.[292] Leaked internal documents also indicate that two thirds of teen girls and 40 percent of teen boys experience negative social comparison, and that Instagram makes 20 percent of the teens feel worse about themselves. According to the leaked research, Instagram has higher impact on appearance comparison than TikTok or Snapchat.[293] 13 percent of British, and 6 percent of US, teenager users with suicidal thoughts could trace them to Instagram use.[292]

Depression, anxiety and stress

Khodarahimi and Fathi found evidence that Instagram users displayed higher levels of depressive and anxious symptoms compared to non-users.[294] However, Frison & Eggermont 2017 found that, among both boys and girls, browsing could predict the presence of depressive symptoms; liking and posting seemed to have no effect.[295] In addition, their study showed that the presence of depressive symptoms in a given user could positively predict that they would make posts.[295] The study showed that the viewing of celebrity and peer pictures could make the moods of women more negative.[295] [296] In a 2021 study, Mun & Kim pointed out that Instagram users with a strong need for approval were more likely to falsely present themselves on their Instagram accounts, which in turn increased the likelihood of depression. However, depression was mitigated by the users’ perception of their own popularity.[297]

Lub & Trub 2015 showed that following more strangers increases social comparisons and depressive symptoms.[298] Multiple studies have found that increasing time spent on Instagram increases social anxiety and anxiety related to personal traits, physical appearance, and high-stress body areas in particular. [299][300][301] Sherlock & Wagstaff 2019 showed that both the number of followers and followees can slightly increase anxiety over personal traits.[302] Additionally, Moujaes & Verrier 2020 observed a connection between online engagement with mothering-based influencers known as InstaMums and anxiety.[303] However, Mackson et al. 2019 suggested beneficial effects of Instagram use on anxiety symptoms.[304][303]

Body image

Instagram users report higher body surveillance (the habitual monitoring of one’s body shape and size),[305] appearance-related pressure,[306] eating-disorder-related-pathology[307] and lower body satisfaction[307] than non-users. Multiple studies have also shown that users who take more selfies before making a post, and those who strategically present themselves by participating in such activities as editing or manipulating selfies, report higher levels of body surveillance and body dissatisfaction, and lower body esteem overall.[308][309][310][311] Tiggermann et al. showed that facial satisfaction can decrease when one spends greater time editing selfies for Instagram. Comments related to appearance on Instagram can lead to higher dissatisfaction with one’s body.[312][313][314][315]

Loneliness and social exclusion

Mackson et al. 2019 found that Instagram users were less lonely than non-users[304] and that Instagram membership predicts lower self-reported loneliness.[311] A 2021 study by Büttner & Rudertb also showed that not being tagged in an Instagram photo triggers the feeling of social exclusion and ostracism, especially for those with higher needs to belong.[316] However, Brailovskaia & Margraf 2018 found a significant positive relationship between Instagram membership and extraversion, life satisfaction, and social support. Their study showed only a marginally significant negative association between Instagram membership and self-conscientiousness.[317] Fioravanti et al. 2020 showed that women who had to take a break from Instagram for seven days reported higher life satisfaction compared to women who continued their habitual pattern of Instagram use. The effects seemed to be specific for women, where no significant differences were observed for men.[318] The relationship between Instagram use and the fear of missing out, or FOMO, has been confirmed in multiple studies.[319][320] Research shows that Instagram browsing predicts social comparison, which generates FOMO, which can ultimately lead to depression.[321]

Alcohol and drug use

There is a small positive correlation between the intensity of one’s Instagram usage and alcohol consumption, with binge drinkers reporting greater intensity of Instagram use than non-binge drinkers.[322] Boyle et al. 2016 found a small to moderate positive relationship between alcohol consumption, enhanced drinking motives, and drinking behavior during college and Instagram usage,[323]

Eating disorders

A comparison of Instagram users with non-users showed that boys with an Instagram account differ from boys without an account in terms of over-evaluation of their shape and weight, skipping meals, and levels of reported disordered eating cognitions. Girls with an Instagram account only differed from girls without an account in terms of skipping meals; they also had a stricter exercise schedule, a pattern not found in boys. This suggests a possible negative effect of Instagram usage on body satisfaction and disordered eating for both boys and girls.[311][324] Several studies identified a small positive relationship between time spent on Instagram and both internalization of beauty and/or muscular ideals and self-objectification.[311][325][326][327] Both Appel et al. 2016 and Feltman et al. 2017 found a positive link between the intensity of Instagram use and both body surveillance and dietary behaviors or disordered eating.[328][327]

Suicide and self-harm

Picardo et al. 2020 examined the relationship between self-harm posts and actual self-harm behaviours offline and found such content had negative emotional effects on some users. The study also reported preliminary evidence of the online posts affecting offline behavior, but stopped short of claiming causality. At the same time, some benefits for those who engage with self-harm content online have been suggested.[329] Instagram has published resources to help users in need of support.[330]

Sharenting risks

Sharenting is when parents post content online, including images, about their children. Instagram is one of the most popular social media channels for sharenting. The hashtag #letthembelittle contains over 10 million images related to children on Instagram. Bare 2020 analysed 300 randomly selected, publicly available images under the hashtag and found that the corresponding images tended to contain children’s personal information, including name, age and location.[331]

Instagram addiction

Sanz-Blas et al. 2019 showed that users who feel that they spend too much time on Instagram report higher levels of «addiction» to Instagram, which in turn was related to higher self-reported levels of stress induced by the app.[332] In a study focusing on the relationship between various psychological needs and «addiction» to Instagram by students, Foroughi et al. 2021 found that the desire for recognition and entertainment were predictors of students’ addiction to Instagram. In addition, the study proved that addiction to Instagram negatively affected academic performance.[333] Additionally, Gezgin & Mihci 2020 found that frequent Instagram usage correlated with smartphone addiction.[334]

Impact on businesses

Instagram can help promote commercial products and services.[335] It can be distinguished from other social media platforms by its focus on visual communication, which can be very effective for business owners.[335] The platform can also lead to high engagement, which is due to its large user base and high growth rates. The platform can also help commercial entities save branding costs, as it can be used for free even for commercial purposes. However, the inherently visual nature of the platform can in some ways be detrimental to the presentation of content.[335]

Governmental response

In September 2022, the Ireland’s Data Protection Commission fined the company $402 million under privacy laws recently adopted by the European Union over how it handled the privacy data of minors.[336][337][338]

User characteristics and behavior

The Instagram app, running on the Android operating system

Users

Following the release in October, Instagram had one million registered users in December 2010.[339][340] In June 2011, it announced that it had 5 million users,[341] which increased to 10 million in September.[342][343] This growth continued to 30 million users in April 2012,[342][24] 80 million in July 2012,[344][345] 100 million in February 2013,[346][347] 130 million in June 2013,[348] 150 million in September 2013,[349][350] 300 million in December 2014,[351][352] 400 million in September 2015,[353][354] 500 million in June 2016,[355][356] 600 million in December 2016,[357][358] 700 million in April 2017,[359][360] and 800 million in September 2017.[361][362]

In June 2011, Instagram passed 100 million photos uploaded to the service.[363][364] This grew to 150 million in August 2011,[365][366] and by June 2013, there were over 16 billion photos on the service.[348] In October 2015, there existed over 40 billion photos.[367]

In October 2016, Instagram Stories reached 100 million active users, two months after launch.[368][369] This increased to 150 million in January 2017,[196][197] 200 million in April, surpassing Snapchat’s user growth,[199][200][198] and 250 million active users in June 2017.[370][205]

In April 2017, Instagram Direct had 375 million monthly users.[184][185][186]

Demographics

As of 2014, Instagram’s users are divided equally with 50% iPhone owners and 50% Android owners. While Instagram has a neutral gender-bias format, 68% of Instagram users are female while 32% are male. Instagram’s geographical use is shown to favor urban areas as 17% of US adults who live in urban areas use Instagram while only 11% of adults in suburban and rural areas do so. While Instagram may appear to be one of the most widely used sites for photo sharing, only 7% of daily photo uploads, among the top four photo-sharing platforms, come from Instagram. Instagram has been proven to attract the younger generation with 90% of the 150 million users under the age of 35. From June 2012 to June 2013, Instagram approximately doubled their number of users. With regards to income, 15% of US Internet users who make less than $30,000 per year use Instagram, while 14% of those making $30,000 to $50,000, and 12% of users who make more than $50,000 per year do so.[371] With respect to the education demographic, respondents with some college education proved to be the most active on Instagram with 23%. Following behind, college graduates consist of 18% and users with a high school diploma or less make up 15%. Among these Instagram users, 24% say they use the app several times a day.[372]

User behavior

Ongoing research continues to explore how media content on the platform affects user engagement. Past research has found that media which show peoples’ faces receive more ‘likes’ and comments and that using filters that increase warmth, exposure, and contrast also boosts engagement.[373] Users are more likely to engage with images that depict fewer individuals compared to groups and also are more likely to engage with content that has not been watermarked, as they view this content as less original and reliable compared to user-generated content.[374] Recently Instagram has come up with an option for users to apply for a verified account badge; however, this does not guarantee every user who applies will get the verified blue tick.[375]

The motives for using Instagram among young people are mainly to look at posts, particularly for the sake of social interactions and recreation. In contrast, the level of agreement expressed in creating Instagram posts was lower, which demonstrates that Instagram’s emphasis on visual communication is widely accepted by young people in social communication.[376]

Performative activism

Starting in June 2020, Instagram was more widely used as a platform for social justice movements including the Black Lives Matter movement.[377][378] This has changed how people address activism, created a lack of consistency in protest, and is not widely accepted.[379][380] Most notably in 2020, Shirien Damra shared an illustration and tribute she made of George Floyd after his murder, and it resulted in more than 3.4 million «likes», followed by many offline reproductions of the illustration.[381][382] Instagram-based activism (as well as other social media) has been criticized and dismissed for being performative, reductionist, and overly focused on aesthetics.[379]

Reception

Awards

Instagram was the runner-up for «Best Mobile App» at the 2010 TechCrunch Crunchies in January 2011.[383] In May 2011, Fast Company listed CEO Kevin Systrom at number 66 in «The 100 Most Creative People in Business in 2011».[384] In June 2011, Inc. included co-founders Systrom and Krieger in its 2011 «30 Under 30» list.[9]

Instagram won «Best Locally Made App» in the SF Weekly Web Awards in September 2011.[385] 7x7Magazine’s September 2011 issue featured Systrom and Krieger on the cover of their «The Hot 20 2011» issue.[386] In December 2011, Apple Inc. named Instagram the «App of the Year» for 2011.[387] In 2015, Instagram was named No. 1 by Mashable on its list of «The 100 best iPhone apps of all time,» noting Instagram as «one of the most influential social networks in the world.»[388] Instagram was listed among Time‘s «50 Best Android Applications for 2013» list.[389]

Mental health

In May 2017, a survey conducted by the United Kingdom’s Royal Society for Public Health, featuring 1,479 people aged 14–24, asking them to rate social media platforms depending on anxiety, depression, loneliness, bullying and body image, concluded that Instagram was the «worst for young mental health». Some have suggested it may contribute to digital dependence, whist this same survey noticed its positive effects, including self-expression, self-identity, and community building. In response to the survey, Instagram stated that «Keeping Instagram a safe and supportive place for young people was a top priority».[390][391] The company filters out the reviews and accounts. If some of the accounts violate Instagram’s community guidelines, it will take action, which could include banning them.[392]

In 2017, researchers from Harvard University and University of Vermont demonstrated a machine learning tool that successfully outperformed general practitioners’ diagnostic success rate for depression. The tool used color analysis, metadata components, and face detection of users’ feeds.[393]

In 2019, Instagram began to test the hiding of like counts for posts made by its users, with the feature later made available to everyone.

Correlations have been made between Instagram content and dissatisfaction with one’s body, as a result of people comparing themselves to other users. In a recent survey half of the applicants admitted to photo editing behavior which has been linked with concerns over body image.[394]

In October 2021, CNN published an article and interviews on two young women, Ashlee Thomas and Anastasia Vlasova, saying Instagram endangered their lives due to it having toxic effects on their diets.[395]

In response to abusive and negative comments on users’ photos, Instagram has made efforts to give users more control over their posts and accompanying comments field. In July 2016, it announced that users would be able to turn off comments for their posts, as well as control the language used in comments by inputting words they consider offensive, which will ban applicable comments from showing up.[396][397] After the July 2016 announcement, the ability to ban specific words began rolling out early August to celebrities,[398] followed by regular users in September.[399] In December, the company began rolling out the abilities for users to turn off the comments and, for private accounts, remove followers.[400][401]

In June 2017, Instagram announced that it would automatically attempt to filter offensive, harassing, and «spammy» comments by default. The system is built using a Facebook-developed deep learning algorithm known as DeepText (first implemented on the social network to detect spam comments), which utilizes natural-language processing techniques, and can also filter by user-specified keywords.[402][403][392]

In September 2017, the company announced that public users would be able to limit who can comment on their content, such as only their followers or people they follow. At the same time, it updated its automated comment filter to support additional languages.[404][405]

In July 2019, the service announced that it would introduce a system to proactively detect problematic comments and encourage the user to reconsider their comment, as well as allowing users the ability to «restrict» others’ abilities to communicate with them, citing that younger users felt the existing block system was too much of an escalation.[83]

An April 2022 study by the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that Instagram failed to act on 90% of abusive direct messages (DMs) sent to five high-profile women, despite the DMs being reported to moderators. The participants of the study included actress Amber Heard, journalist Bryony Gordon, television presenter Rachel Riley, activist Jamie Klingler and magazine founder Sharan Dhaliwal. Instagram disputed many of the study’s conclusions.[406][407][408]

Culture

On August 9, 2012, English musician Ellie Goulding released a new music video for her song «Anything Could Happen.» The video only contained fan-submitted Instagram photographs that used various filters to represent words or lyrics from the song, and over 1,200 different photographs were submitted.[409]

Security

In August 2017, reports surfaced that a bug in Instagram’s developer tools had allowed «one or more individuals» to gain access to the contact information, specifically email addresses and phone numbers, of several high-profile verified accounts, including its most followed user, Selena Gomez. The company said in a statement that it had «fixed the bug swiftly» and was running an investigation.[410][411] However, the following month, more details emerged, with a group of hackers selling contact information online, with the affected number of accounts in the «millions» rather than the previously assumed limitation on verified accounts. Hours after the hack, a searchable database was posted online, charging $10 per search.[412] The Daily Beast was provided with a sample of the affected accounts, and could confirm that, while many of the email addresses could be found with a Google search in public sources, some did not return relevant Google search results and thus were from private sources.[413] The Verge wrote that cybersecurity firm RepKnight had found contact information for multiple actors, musicians, and athletes,[412] and singer Selena Gomez’s account was used by the hackers to post naked photos of her ex-boyfriend Justin Bieber. The company admitted that «we cannot determine which specific accounts may have been impacted», but believed that «it was a low percentage of Instagram accounts», though TechCrunch stated in its report that six million accounts were affected by the hack, and that «Instagram services more than 700 million accounts; six million is not a small number».[414]

In 2019, Apple pulled an app that let users stalk people on Instagram by scraping accounts and collecting data.[415]

Iran has DPI blocking for Instagram.[416]

Content ownership

On December 17, 2012, Instagram announced a change to its Terms of Service policy, adding the following sentence:[417]

To help us deliver interesting paid or sponsored content or promotions, you agree that a business or other entity may pay us to display your username, likeness, photos (along with any associated metadata), and/or actions you take, in connection with paid or sponsored content or promotions, without any compensation to you.

There was no option for users to opt out of the changed Terms of Service without deleting their accounts before the new policy went into effect on January 16, 2013.[418] The move garnered severe criticism from users,[419][420] prompting Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom to write a blog post one day later, announcing that they would «remove» the offending language from the policy. Citing misinterpretations about its intention to «communicate that we’d like to experiment with innovative advertising that feels appropriate on Instagram», Systrom also stated that it was «our mistake that this language is confusing» and that «it is not our intention to sell your photos». Furthermore, he wrote that they would work on «updated language in the terms to make sure this is clear».[421][419]

The policy change and its backlash caused competing photo services to use the opportunity to «try to lure users away» by promoting their privacy-friendly services,[422] and some services experienced substantial gains in momentum and user growth following the news.[423] On December 20, Instagram announced that the advertising section of the policy would be reverted to its original October 2010 version.[424] The Verge wrote about that policy as well, however, noting that the original policy gives the company right to «place such advertising and promotions on the Instagram Services or on, about, or in conjunction with your Content», meaning that «Instagram has always had the right to use your photos in ads, almost any way it wants. We could have had the exact same freakout last week, or a year ago, or the day Instagram launched».[417]

The policy update also introduced an arbitration clause, which remained even after the language pertaining to advertising and user content had been modified.[425]

Facebook acquisition as a violation of US antitrust law

Columbia Law School professor Tim Wu has given public talks explaining that Facebook’s 2012 purchase of Instagram was a felony.[426] A New York Post article published on February 26, 2019, reported that «the FTC had uncovered [a document] by a high-ranking Facebook executive who said the reason the company was buying Instagram was to eliminate a potential competitor».[427] As Wu explains, this is a violation of US antitrust law (see monopoly). Wu stated that this document was an email directly from Mark Zuckerberg, whereas the Post article had stated that their source had declined to say whether the high-ranking executive was the CEO. The article reported that the FTC «has formed a task force to review «anticompetitive conduct» in the tech world amid concerns that tech companies are growing too powerful. The task force will look at «the full panoply of remedies» if it finds «competitive harm,» FTC competition bureau director Bruce Hoffman told reporters.»

Algorithmic advertisement with a rape threat

In 2016, Olivia Solon, a reporter for The Guardian, posted a screenshot to her Instagram profile of an email she had received containing threats of rape and murder towards her. The photo post had received three likes and countless comments, and in September 2017, the company’s algorithms turned the photo into an advertisement visible to Solon’s sister. An Instagram spokesperson apologized and told The Guardian that «We are sorry this happened – it’s not the experience we want someone to have. This notification post was surfaced as part of an effort to encourage engagement on Instagram. Posts are generally received by a small percentage of a person’s Facebook friends.» As noted by the technology media, the incident occurred at the same time parent company Facebook was under scrutiny for its algorithms and advertising campaigns being used for offensive and negative purposes.[428][429]

Human exploitation

In May 2021, The Washington Post published a report detailing a «black market» of unlicensed employment agents luring migrant workers from Africa and Asia into indentured servitude as maids in Persian Gulf countries, and using Instagram posts containing their personal information (including in some cases, passport numbers) to market them. Instagram deleted 200 accounts that had been reported by the Post, and a spokesperson stated that Instagram took this activity «extremely seriously», disabled 200 accounts found by the Post to be engaging in these activities, and was continuing to work on systems to automatically detect and disable accounts engaging in human exploitation.[430]

July 2022 Updates

In July 2022, Instagram announced a set of updates which immediately received widespread backlash from its userbase. The changes included a feed more focused on Instagram’s content algorithms, full-screen photo and video posts, and changing the format of all of its videos to Reels. The primary criticisms for these updates was Instagram being more like TikTok, instead of photo sharing. The backlash originated from an Instagram post and Change.org petition created by photographer Tati Bruening (under the username @illumitati) on July 23, 2022, featuring the statement “Make Instagram Instagram again. (stop trying to be tiktok i just want to see cute photos of my friends.) Sincerely, everyone.”. The post and petition gained mainstream attention after influencers Kylie Jenner and Kim Kardashian reposted the Instagram post; subsequently, the original post gained over 2 million likes on Instagram and over 275,000 signatures on Change.org.[431][432][433] Instagram walked back the update on July 28, with Meta saying “We recognize that changes to the app can be an adjustment, and while we believe that Instagram needs to evolve as the world changes, we want to take the time to make sure we get this right.»[434]

Censorship and restricted content

Illicit drugs

Instagram has been the subject of criticism due to users publishing images of drugs they are selling on the platform. In 2013, the BBC discovered that users, mostly located in the United States, were posting images of drugs they were selling, attaching specific hashtags, and then completing transactions via instant messaging applications such as WhatsApp. Corresponding hashtags have been blocked as part of the company’s response and a spokesperson engaged with the BBC explained:[435][436]

Instagram has a clear set of rules about what is and isn’t allowed on the site. We encourage people who come across illegal or inappropriate content to report it to us using the built-in reporting tools next to every photo, video or comment, so we can take action. People can’t buy things on Instagram, we are simply a place where people share photos and videos.

However, new incidents of illegal drug trade have occurred in the aftermath of the 2013 revelation, with Facebook, Inc., Instagram’s parent company, asking users who come across such content to report the material, at which time a «dedicated team» reviews the information.[437]

In 2019, Facebook announced that influencers are no longer able to post any vape, tobacco products, and weapons promotions on Facebook and Instagram.[438]

Women’s bodies

In October 2013, Instagram deleted the account of Canadian photographer Petra Collins after she posted a photo of herself in which a very small area of pubic hair was visible above the top of her bikini bottom. Collins claimed that the account deletion was unfounded because it broke none of Instagram’s terms and conditions.[439] Audra Schroeder of The Daily Dot further wrote that «Instagram’s terms of use state users can’t post «pornographic or sexually suggestive photos,» but who actually gets to decide that? You can indeed find more sexually suggestive photos on the site than Collins’, where women show the side of «femininity» the world is «used to» seeing and accepting.»[440] Nick Drewe of The Daily Beast wrote a report the same month focusing on hashtags that users are unable to search for, including #sex, #bubblebutt, and #ballsack, despite allowing #faketits, #gunsforsale and #sexytimes, calling the discrepancy «nonsensical and inconsistent».[441]

Similar incidents occurred in January 2015, when Instagram deleted Australian fashion agency Sticks and Stones Agency’s account because of a photograph including pubic hair sticking out of bikini bottoms,[442] and March 2015, when artist and poet Rupi Kaur’s photos of menstrual blood on clothing were removed, prompting a rallying post on her Facebook and Tumblr accounts with the text «We will not be censored», gaining over 11,000 shares.[443]

The incidents have led to a #FreetheNipple campaign, aimed at challenging Instagram’s removal of photos displaying women’s nipples. Although Instagram has not made many comments on the campaign,[444] an October 2015 explanation from CEO Kevin Systrom highlighted Apple’s content guidelines for apps published through its App Store, including Instagram, in which apps must designate the appropriate age ranking for users, with the app’s current rating being 12+ years of age. However, this statement has also been called into question due to other apps with more explicit content allowed on the store, the lack of consequences for men exposing their bodies on Instagram, and for inconsistent treatment of what constitutes inappropriate exposure of the female body.[445][446]

Iranian government bribed moderators $9,000 to delete Masih Alinejad anti-Islamic women rules account.[447]

Censorship by countries

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

Censorship of Instagram has occurred in several different countries.

United States

On January 11, 2020, Instagram and its parent company Facebook, Inc. are removing posts «that voice support for slain Iranian commander Qassem Soleimani to comply with US sanctions».[448]

On October 30, 2020, Instagram temporarily removed the «recent» tab on hashtag pages to prevent the spread of misinformation regarding the 2020 United States presidential election.[449] On January 7, 2021, United States President Donald Trump was banned from Instagram «indefinitely». Zuckerberg stated «We believe the risks of allowing the President to continue to use our service during this period are simply too great.»[450]

A few days after Facebook changed its name to Meta, an Australian artist and technologist, Thea-Mai Baumann, had lost access to her @metaverse Instagram handle. Bauman tried to reclaim her access for a month, without success. Only after The New York Times published the story and contacted Meta’s PR department, was the access restored.[451]

China

Instagram has been blocked by China following the 2014 Hong Kong protests as many confrontations with police and incidents occurring during the protests were recorded and photographed. Hong Kong and Macau were not affected as they are part of special administrative regions of China.[452]

Turkey

Turkey is also known for its strict Internet censorship and periodically blocks social media including Instagram.[453]

North Korea

A few days after a fire incident that happened in the Koryo Hotel in North Korea on June 11, 2015, authorities began to block Instagram to prevent photos of the incident from being spread out.[454]

Iran

As of February 2022, Instagram is one of the last freely available global social media sites in Iran.[455] Instagram is popular among Iranians because it is seen as an outlet for freedom and a «window to the world.»[456]

Still, Iran has sentenced several citizens to prison for posts made on their Instagram accounts.[457] The Iranian government also blocked Instagram periodically during anti-government protests.[458] In July 2021, Instagram temporarily censored videos with the phrase «death to Khamenei».[459]

Cuba

The Cuban government blocked access to several social media platforms, including Instagram, to curb the spread of information during the 2021 Cuban protests.[460]

Russia

On March 11, 2022, Russia announced it would ban Instagram due to alleged «calls for violence against Russian troops» on the platform during the ongoing 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[461] On March 14, the ban took effect, with almost 80 million users losing access to Instagram.[462]

Statistics

As of January 07, 2023, the most followed person is Portuguese professional footballer Cristiano Ronaldo with over 530 million followers.[463] As of January 07, 2023, the most-liked photo on Instagram is a carousel of photos from footballer Lionel Messi celebrating winning the 2022 FIFA World Cup, The post has over 74 million likes.[464]

Instagram was the fourth most downloaded mobile app of the 2010s.[463]

In popular culture

- Social Animals (documentary film): A documentary film about three teenagers growing up on Instagram

- Instagram model: a term for models who gain their success as a result of the large number of followers they have on Instagram

- Instapoetry: a style of poetry which formed by sharing images of short poems by poets on Instagram.

- Instagram Pier: a cargo working area in Hong Kong that gained its nickname due to its popularity on Instagram

System

Instagram is written in Python.[465]

Instagram artificial intelligence (AI) describes content for visually impaired people that use screen readers.[466]

See also

- List of social networking services

- Criticism of Facebook

- Dronestagram

- Internet celebrity

- Instagram face

- Pheed

- Pixnet

- Social media and suicide

- Timeline of social media

Explanatory notes

- ^ The name is often colloquially abbreviated as IG, Insta, or the Gram.[6]

References

- ^ a b «Instagram APKs». APKMirror.

- ^ «Instagram». App Store.

- ^ «Instagram APKs». APKMirror.

- ^ «Amazon.com: Instagram: Appstore for Android». Amazon.

- ^ «Instagram». App Store. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ For example:Edwards, Erica B.; Esposito, Jennifer (2019). «Reading social media intersectionally». Intersectional Analysis as a Method to Analyze Popular Culture: Clarity in the Matrix. Futures of Data Analysis in Qualitative Research. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-55700-2. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

Instagram (IG) is a photo sharing app created in October of 2010 allowing users to share photos and videos.

- ^ a b «Instagram Stories is Now Being Used by 500 Million People Daily». Social Media Today. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ «Instagram hits 1 billion monthly users, up from 800M in September». TechCrunch. June 20, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Lagorio, Christine (June 27, 2011). «Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, Founders of Instagram». Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini; Perlroth, Nicole; Wortham, Jenna (April 13, 2012). «Behind Instagram’s Success, Networking the Old Way». The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ a b «Take a Look Back at Instagram’s First Posts, Six Years Ago». Time. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ «5 Of The Most Popular Instagram Accounts». Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ Siegler, MG (March 5, 2010). «Burbn’s Funding Goes Down Smooth. Baseline, Andreessen Back Stealthy Location Startup». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c Shontell, Alyson (April 9, 2012). «Meet The 13 Lucky Employees And 9 Investors Behind $1 Billion Instagram». Business Insider. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Beltrone, Gabriel (July 29, 2011). «Instagram Surprises With Fifth Employee». Adweek. Beringer Capital. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ «Instagram post by Mike Krieger • Jul 16, 2010 at 5:26pm UTC». Instagram. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ «Instagram post by Kevin Systrom • Jul 16, 2010 at 9:24pm UTC». Instagram.

- ^ «Here’s The First Instagram Photo Ever». Time.

- ^ Siegler, MG (October 6, 2010). «Instagram Launches with the Hope of Igniting Communication Through Images». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Siegler, MG (February 2, 2011). «Instagram Filters Through Suitors To Capture $7 Million in Funding Led By Benchmark». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Markowitz, Eric (April 10, 2012). «How Instagram Grew From Foursquare Knock-Off to $1 Billion Photo Empire». Inc. Mansueto Ventures. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Tsotsis, Alexia (April 9, 2012). «Right Before Acquisition, Instagram Closed $50M at A$500M Valuation From Sequoia, Thrive, Greylock And Benchmark». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ «The 26-Year-Old VC Who Cashed In On Instagram». Forbes. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Tsotsis, Alexia (April 3, 2012). «With Over 30 Million Users on iOS, Instagram Finally Comes To Android». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Houston, Thomas (April 3, 2012). «Instagram for Android now available». The Verge. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Blagdon, Jeff (April 4, 2012). «Instagram for Android breaks 1 million downloads in less than a day». The Verge. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Bell, Karissa (March 11, 2014). «Instagram Releases Faster, More Responsive Android App». Mashable. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Cohen, David (March 11, 2014). «Twice As Quick, Half As Large: Instagram Updates Android App». Adweek. Beringer Capital. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Constine, Josh (April 18, 2017). «Instagram on Android gets offline mode». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ O’Kane, Sean (April 19, 2017). «Instagram for Android now works offline». The Verge. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Ghoshal, Abhimanyu (April 19, 2017). «Instagram now works offline on Android». The Next Web. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Upbin, Bruce (April 9, 2012). «Facebook Buys Instagram For $1 Billion. Smart Arbitrage». Forbes. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Rusli, Evelyn M. (April 9, 2012). «Facebook Buys Instagram for $1 Billion». The New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Oreskovic, Alexei; Shih, Gerry (April 10, 2012). «Facebook to buy Instagram for $1 billion». Reuters. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Constine, Josh; Cutler, Kim-Mai (April 9, 2012). «Facebook Buys Instagram For $1 Billion, Turns Budding Rival into Its Standalone Photo App». TechCrunch. AOL. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Houston, Thomas (April 9, 2012). «Facebook to buy Instagram for $1 billion». The Verge. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Segall, Laurie (April 9, 2012). «Facebook acquires Instagram for $1 billion». CNNMoney. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ «Facebook’s Instagram bid gets go-ahead from the OFT». BBC. August 14, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Oreskovic, Alexei (August 22, 2012). «FTC clears Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram». Reuters. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Protalinski, Emil (April 23, 2012). «Facebook buying Instagram for $300 million, 23 million shares». ZDNet. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (April 9, 2012). «Exclusive: Facebook Deal Nets Instagram CEO $400 Million». Wired. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Hamburger, Ellis (November 5, 2012). «Instagram launches web profiles, but maintains clear focus on mobile». The Verge. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ «Instagram Launches Embeddable «Badges» To Help You Promote Your Beautiful Profile On The Web». TechCrunch. November 21, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Carr, Austin (March 25, 2014). «Instagram Testing Facebook Places Integration To Replace Foursquare». Fast Company. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Steele, Billy (March 25, 2014). «Instagram is testing Facebook Places integration for location tagging». Engadget. AOL. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (June 9, 2015). «Instagram is launching a redesigned website with bigger photos». The Verge. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Lopez, Napier (June 9, 2015). «Instagram for the Web is getting a cleaner, flatter redesign». The Next Web. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Shadman, Aadil (June 11, 2015). «Instagram on Web Just Got a Major Design Overhaul». propakistani.pk.

- ^ «Pre-2015 Instagram website layout screenshot».

- ^ «Pre-June-2015 Instagram website layout screenshot with «slideshow banner»«.

- ^ Warren, Tom (March 6, 2013). «Nokia wants Instagram for Windows Phone, piles pressure on with #2InstaWithLove». The Verge. Retrieved April 8, 2017.