This article is about the fashion designer. For the company, see Dior.

|

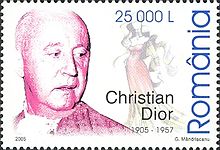

Christian Dior |

|

|---|---|

Dior in 1954 |

|

| Born | 21 January 1905

Granville, France |

| Died | 24 October 1957 (aged 52)

Montecatini Terme, Tuscany, Italy |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Callian, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, France[1] |

| Alma mater | Sciences Po |

| Label | Christian Dior |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Christian Ernest Dior (French: [kʁistjɑ̃ djɔʁ]; 21 January 1905 – 24 October 1957) was a French fashion designer, best known as the founder of one of the world’s top fashion houses, Christian Dior SE, which is now owned by parent company LVMH. His fashion houses are known all around the world, specifically «on five continents in only a decade» (Sauer[2]). He was the second child of a family of seven, born to Maurice Dior and Madeleine Martin, in the town of Granville.

Dior’s artistic skills led to his employment and design for various well-known fashion icons in attempts to preserve the fashion industry during World War II. Post-war, he founded and established the Dior fashion house, with his collection of the «New Look» revolutionising women’s dress and contributing to the reestablishment of Paris as the centre of the fashion world.

Throughout his lifetime, he won numerous awards for Best Costume Design. Upon his death in 1957, various contemporary icons paid tribute to his life and work.

Early life[edit]

The Christian Dior Home and Museum in Granville, France

Christian Dior was born in Granville, a seaside town on the coast of Normandy, France. He was the second of five children born to Maurice Dior, a wealthy fertilizer manufacturer (the family firm was Dior Frères), and his wife, formerly Madeleine Martin. He had four siblings: Raymond (father of Françoise Dior), Jacqueline, Bernard, and Catherine Dior.[3] When Christian was about five years old, the family moved to Paris, but still returned to the Normandy coast for summer holidays.

Dior’s family had hoped he would become a diplomat, but Dior was artistic and wished to be involved in art.[4] To make money, he sold his fashion sketches outside his house for about 10 cents each. In 1928, Dior left school and received money from his father to finance a small art gallery, where he and a friend sold art by the likes of Pablo Picasso. The gallery was closed three years later, following the deaths of Dior’s mother and brother, as well as financial trouble during the Great Depression that resulted in his father losing control of the family business.

From 1937, Dior was employed by the fashion designer Robert Piguet, who gave him the opportunity to design for three Piguet collections.[5][6] Dior would later say that «Robert Piguet taught me the virtues of simplicity through which true elegance must come.»[7][8] One of his original designs for Piguet, a day dress with a short, full skirt called «Cafe Anglais», was particularly well received.[5][6] Whilst at Piguet, Dior worked alongside Pierre Balmain, and was succeeded as house designer by Marc Bohan – who would, in 1960, become head of design for Christian Dior Paris.[6] Dior left Piguet when he was called up for military service.

In 1942, when Dior left the army, he joined the fashion house of Lucien Lelong, where he and Balmain were the primary designers. For the duration of World War II, Dior, as an employee of Lelong – who labored to preserve the French fashion industry during wartime for economic and artistic reasons — designed dresses for the wives of Nazi officers and French collaborators, as did other fashion houses that remained in business during the war, including Jean Patou, Jeanne Lanvin, and Nina Ricci.[9][10] His sister, Catherine (1917–2008), served as a member of the French Resistance, was captured by the Gestapo, and sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she was incarcerated until her liberation in May 1945.[11] In 1947, he named his debut fragrance, Miss Dior in tribute to his sister.

The Dior fashion house[edit]

In 1946, Marcel Boussac, a successful entrepreneur known as the richest man in France, invited Dior to design for Philippe et Gaston, a Paris fashion house launched in 1925.[12] Dior refused, wishing to make a fresh start under his own name rather than reviving an old brand.[13] On 8 December 1946, with Boussac’s backing, Dior founded his fashion house. The name of the line of his first collection, presented on 12 February 1947,[14] was Corolle (literally the botanical term corolla or circlet of flower petals in English). The phrase New Look was coined for it by Carmel Snow, the editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar.[15][16]

Despite being called «New», it was clearly drawn from styles of the Edwardian era.[17][18] The New Look merely refined and crystallized trends in skirt shape and waistline that had been burgeoning in high fashion since the late 1930s.[19][20] Dior’s designs were more voluptuous than the boxy, fabric-conserving shapes of the recent World War II styles, influenced by the wartime rationing of fabric.[21]

Dior was a master at creating shapes and silhouettes. Dior was quoted as saying: «I have designed flower women.»[citation needed] His look employed fabrics lined predominantly with percale, boned, bustier-style bodices, hip padding, wasp-waisted corsets, and petticoats that made his dresses flare out from the waist, giving his models a very curvaceous form.[citation needed]

Initially, women protested because his designs covered up their legs, which they had been unused to because of the previous limitations on fabric. Some of the backlash to Dior’s designs was also due to the amount of fabric used in a single dress or suit. Gabrielle «Coco» Chanel said of the «New Look»: «Look how ridiculous these women are, wearing clothes by a man who doesn’t know women, never had one, and dreams of being one.»[citation needed] During one photo shoot in a Paris market, the models were attacked by female vendors over this profligacy, but opposition ceased as the wartime shortages ended.[citation needed]

The «New Look» revolutionized women’s dress and reestablished Paris as the centre of the fashion world after World War II,[22][23] as well as making Dior a virtual arbiter of fashion for much of the following decade.[24] Each season featuring a newly titled Dior «line», in the manner of 1947’s «Corolle» line, that would then be trumpeted in the fashion press: the Envol and Cyclone/Zigzag lines in 1948; the Trompe l’Oeil and Mid-Century lines in 1949; the Vertical and Oblique lines in 1950; the Naturelle/Princesse and Longue lines in 1951; the Sinueuse and Profilėe lines in 1952; the Tulipe and Vivante lines in 1953; the Muguet/Lily of the Valley line and H-Line in 1954; the A-Line and Y-Line in 1955; the Flèche/Arrow and Aimant/Magnet lines in 1956; and the Libre/Free and Fuseau/Spindle lines in 1957,[25][26] followed by successor Yves Saint Laurent’s Trapeze line in 1958.[27][28]

In 1955, the 19-year-old Yves Saint Laurent became Dior’s design assistant. Christian Dior later met with Yves Saint Laurent’s mother, Lucienne Mathieu-Saint Laurent, in 1957, to tell her that he had chosen Saint Laurent to succeed him at Dior. She indicated later that she had been confused by the remark, as Dior was only 52 at the time.[29]

Death[edit]

Christian Dior died of a sudden heart attack while on vacation in Montecatini, Italy, on 24 October 1957 in the late afternoon while playing a game of cards.[30][31] He was survived by Jacques Benita, a North African singer three decades his junior,[32][33] the last of a number of discreet male lovers.[33][34]

Awards and honors[edit]

Dior on a Romanian stamp (2005)

Dior was nominated for the 1955 Academy Award for Best Costume Design in black and white for the Terminal Station directed by Vittorio De Sica (1953). Dior was also nominated in 1967 for a BAFTA for Best British Costume (Colour) for the Arabesque directed by Stanley Donen (1966).[35] Nominated in 1986 for his contributions to the 1985 film, Bras de fer, he was up for Best Costume Design (Meilleurs costumes) during the 11th Cesar Awards.[36]

Cultural references[edit]

A novella by Paul Gallico, Mrs ‘Arris Goes to Paris (1958, UK title Flowers for Mrs Harris), tells the story of a London charwoman who falls in love with her employer’s couture wardrobe and goes to Paris to purchase a Dior ballgown. A perfume named Christian Dior is used in Haruki Murakami’s novel The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle as an influential symbol placed at critical plot points throughout. The English singer-songwriter Morrissey released a song titled «Christian Dior» as a B-side to his 2006 single «In the Future When All’s Well». Kanye West released a song titled «Christian Dior Denim Flow» in 2010. West mentioned the Dior brand in three other songs: «Devil in a New Dress», «Stronger», and «Barry Bonds».[37]

The late American rapper Pop Smoke released a song titled «Dior» in July 2019. Pop Smoke also mentioned the Dior brand in other songs, including «Enjoy Yourself»: «Shopping up in Saks Fifth with a cup of Actavis to get Christian Dior; Look, I be all up in the stores (Oh, oh).»[38]

In 2016, book publisher Assouline introduced an ongoing series devoted to each designer of the couture house of Dior. Published titles include Dior by Christian Dior,[39] Dior by YSL,[40] Dior by Marc Bohan,[41] and Dior by Gianfranco Ferre.[42]

See also[edit]

- Château de La Colle Noire

References[edit]

- ^ Var: Côte d’Azur, Verdon, by Dominique Auzias, Jean-Paul Labourdette, Nouvelles éditions de l’Université, 1 January 2010, pg 150

- ^ «The History of the House of Dior». 20 November 2018.

- ^ Pochna, M-F. (1996). Christian Dior: The Man Who Made the World Look New p. 5, Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-340-7.

- ^ Pochna, Marie-France (1996). Christian Dior: The Man Who Made the World Look New (1st English language ed.). New York: Arcade Pub. p. 207. ISBN 1-55970-340-7.

- ^ a b Marly, Diana de (1990). Christian Dior. London: B.T. Batsford. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7134-6453-5.

Dior designed three collections while at Piguet’s, and the most famous dress he created then was the Cafe Anglais

- ^ a b c Pochna, Marie-France (1996). Christian Dior: The Man Who Made the World Look New. Translated by Savill, Joanna (1st English language ed.). New York: Arcade Pub. pp. 62, 72, 74, 80, 102. ISBN 978-1-55970-340-6.

Robert Piguet.

- ^ Grainger, Nathalie (2010). Quintessentially Perfume. London: Quintessentially Pub. Ltd. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-9558270-6-8.

- ^ Picken, Mary Brooks; Dora Loues Miller (1956). Dressmakers of France: The Who, How, and why of the French Couture. Harper. p. 105.

- ^ Jayne Sheridan, Fashion, Media, Promotion: The New Black Magic (John Wiley & Sons, 2010), p. 44.

- ^ Yuniya Kawamura, The Japanese Revolution in Fashion (Berg Publishers, 2004), page 46. As quoted in the book, Lelong was a leading force in keeping the French fashion industry from being forcibly moved to Berlin, arguing, «You can impose anything upon us by force, but Paris couture cannot be uprooted, neither as a whole or in any part. Either it stays in Paris, or it does not exist. It is not within the power of any nation to steal fashion creativity, for not only does it function quite spontaneously, also it is the product of a tradition maintained by a large body of skilled men and women in a variety of crafts and trades.» Kawamura explains that the survival of the French fashion industry was critical to the survival of France, stating, «Export of a single dress by a leading couturier enabled the country to buy ten tons of coal, and a liter of perfume was worth two tons of petrol» (page 46).

- ^ Sereny, Gitta (2002). The Healing Wound: Experiences and Reflections, Germany, 1938–2001. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-393-04428-9.

- ^ Palmer, Alexandra (Spring 2010). «Dior’s Scandalous New Look». ROM Magazine. Royal Ontario Museum. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Pochna, Marie-France (1996). Christian Dior: The Man Who Made the World Look New. Translated by Savill, Joanna (1st English language ed.). New York: Arcade Pub. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-1-55970-340-6.

- ^ Company History at Dior’s website Archived 7 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morris, Bernadine (29 July 1976). «A Revolutionary Saint Laurent Showing». The New York Times: 65. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

[T]he collection Christian Dior showed in 1947 … was Edwardian

- ^ Mulvagh, Jane (1988). «1946-1956». Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. pp. 180–181. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

Dior’s New Look was still relying on old-fashioned underpinnings like boned corsetry … Fashion … reviv[ed] the mock-Edwardian style first presented in the late thirties. … [Dior’s] tighter waists, longer, fuller skirts and more pronounced hips were in fact the maximization of an old style

- ^ Morris, Bernadine (29 July 1976). «A Revolutionary Saint Laurent Showing». The New York Times: 65. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

[T]he collection Christian Dior showed in 1947 … was Edwardian

- ^ Mulvagh, Jane (1988). «1946-1956». Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. pp. 180–181. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

Dior’s New Look was still relying on old-fashioned underpinnings like boned corsetry … Fashion … reviv[ed] the mock-Edwardian style first presented in the late thirties. … [Dior’s] tighter waists, longer, fuller skirts and more pronounced hips were in fact the maximization of an old style

- ^ Mulvagh, Jane (1988). «1947». Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 194. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

[T]he trend towards longer skirts, smaller waists and feminine lines had begun in the late thirties and was seen in America in the early forties; hence Dior was not the originator of this mode, but its rejuvenator and popularist.

- ^ Cunningham, Bill (1 March 1988). «Fashionating Rhythm». Details. New York, NY: Details Publishing Corp. VI (8): 121. ISSN 0740-4921.

Each of the major fashion changes that mark a season is the result of a series of creative designers adding essential elements to the overall picture. The eventual credit for the genius is often given to the designer who articulated the look with commercial success, such as Dior achieved with his 1947 New Look, although it had been seen in small prototypes at Balenciaga in the early Forties and at other Paris houses just before the war.

- ^ Grant, L. (22 September 2007). «Light at the end of the tunnel». The Guardian, Life & Style. London. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Morris, Bernadine (14 April 1981). «How Paris Kept Position in Fashion». The New York Times: B19. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

Dior’s bombshell brought manufacturers as well as store buyers rushing back to the City of Light as they sought to interpret his inspirational designs for their own clients….Throughout the 1950’s, Paris was acclaimed as the source of fashion, and Dior’s success helped stave off the development of other independent style centers for at least a decade.

- ^ «Christian Dior – Fashionsizzle». fashionsizzle.com. 12 January 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Howell, Georgina (1978). «1948-1959». In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 204. ISBN 0-14-004955-X.

Women obeyed Paris because of Christian Dior.

- ^ Howell, Georgina (1978). «1947, 1948-1959». In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 198, 204, 221–245. ISBN 0-14-004955-X.

page range covering mention of Dior line names

- ^ Mulvagh, Jane (1988). «1946-1956». Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, The Penguin Group. pp. 194–248. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

page range covering mention of Dior line names

- ^ Howell, Georgina (1978). «1958». In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 0-14-004955-X.

- ^ Mulvagh, Jane (1988). «1958». Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, The Penguin Group. pp. 251–252. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

- ^ «Christian Dior». British Vogue. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ «Died. Christian Dior, 52». Time. 4 November 1957. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- ^ In French: Grunebaum, Karine (30 January 2013). ««J’ai vu mourir Christian Dior» par Francis Huster». parismatch.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Zotoff, Lucy (25 December 2015). «Revolutions in fashion: Christian Dior». Haute Couture News. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ a b Blanks, Tim (18 August 2002). «The Last Temptation of Christian». New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Du Plessix Gray, Francine (27 October 1996). «Prophets of Seduction». New Yorker. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ «1967 Film British Costume Design – Colour | BAFTA Awards». Awards.bafta.org. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ «Awards – Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma». Academie-cinema.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Kim, Soo-Young (18 June 2013). «The Complete History of Kanye West’s Brand References in Lyrics». Complex. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Pop Smoke (Ft. KAROL G) – Enjoy Yourself, retrieved 24 January 2021

- ^ Saillard, Olivier (2016). Dior by Christian Dior. New York, USA: Assouline. p. 504.

- ^ Benaim, Laurence (2017). Dior by YSL. New York, USA: Assouline. p. 300.

- ^ Hanover, Jerome (2018). Dior by Marc Bohan. New York, USA: Assouline. p. 496.

- ^ Fury, Alexander (2019). Dior by Gianfranco Ferre. New York, USA: Assouline. p. 320.

Further reading[edit]

- Charleston, Beth Duncuff (October 2004). «Christian Dior (1905–1957)». Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Based on original work by Harold Koda.

- Dior, Christian (1957). Christian Dior and I. New York: Dutton.

- Garcia-Moreau, Guillaume, Le château de La Colle Noire, un art de vivre en Provence, Dior, 2018. Read online

- Martin, Richard; Koda, Harold (1996). Christian Dior. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-822-5.

External links[edit]

- Photos of Dior and Samples of New Look Fashion

- «Interactive timeline of couture houses and couturier biographies». Victoria and Albert Museum. 29 July 2015.

- Documentary film Christian Dior, The Man Behind The Myth

- Christian Dior at Chicago History Museum Digital Collections Archived 15 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

|

|

Headquarters in Paris, France |

|

| Type | Public (Societas Europaea)[1] |

|---|---|

|

Traded as |

|

| ISIN | FR0000130403 |

| Industry | Luxury goods |

| Founded | 16 December 1946; 76 years ago |

| Founder | Christian Dior |

| Headquarters | 30 Avenue Montaigne Paris, France[2] |

|

Number of locations |

210 |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

Bernard Arnault (chairman) Antoine Arnault (vice-chairman & CEO)[3] Maria Grazia Chiuri (creative director) Kim Jones (creative director)[4] |

| Products | Clothing, cosmetics, fashion accessories, jewelry, perfumes, spirits, watches, wines |

| Services | Department stores |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

163,309 (2019)[5] |

| Divisions |

|

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | dior.com |

Christian Dior SE (French: [kʁistjɑ̃ djɔʁ]),[1] commonly known as Dior (stylized DIOR), is a French luxury fashion house[2] controlled and chaired by French businessman Bernard Arnault, who also heads LVMH, the world’s largest luxury group. Dior itself holds 42.36% shares and 59.01% of voting rights within LVMH.[7][8]

The company was founded in 1946 by French fashion designer Christian Dior, who was originally from Normandy. This brand sells only shoes and clothing that can only be bought in Dior stores. Haute couture is under the Christian Dior Couture division. Pietro Beccari has been the CEO of Christian Dior Couture since 2018.[9]

History[edit]

Founding[edit]

The House of Dior was established on 16 December 1946[10][6] at 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris. However, the current Dior corporation celebrates «1947» as the opening year.[6] Dior was financially backed by wealthy businessman Marcel Boussac.[6][11] Boussac had originally invited Dior to design for Philippe et Gaston, but Dior refused, wishing to make a fresh start under his own name rather than reviving an old brand.[12] The new couture house became a part of «a vertically integrated textile business» already operated by Boussac.[11] Its capital was at FFr 6 million and workforce at 80 employees.[11] The company was really a vanity project for Boussac and was a «majorly owned affiliate of Boussac Saint-Freres S.A. Nevertheless, Dior was allowed a then-unusual great part in his namesake label (legal leadership, a non-controlling stake in the firm, and one-third of pretax profits) despite Boussac’s reputation as a «control freak». Dior’s creativity also negotiated him a good salary.[11]

«New Look» [edit]

«Bar» suit, 1947, displayed in Moscow, 2011

On 12 February 1947, Christian Dior launched his first fashion collection for Spring–Summer 1947. The show of «90 models of his first collection on six mannequins» was presented in the salons of the company’s headquarters at 30 Avenue Montaigne.[6] Originally, the two lines were named «Corolle» and «Huit».[6] However, the new collection went down in fashion history as the «New Look» after the editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar Carmel Snow exclaimed, «It’s such a new look!»[6][11] The New Look was a revolutionary era for women at the end of the 1940s.[13] When the collection was presented, the editor in chief also showed appreciation by saying; «It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian!»[13] The debut collection of Christian Dior is credited with having revived the fashion industry of France.[14] Along with that, the New Look brought back the spirit of haute couture in France as it was considered glamorous and young-looking.[15] «We were witness to a revolution in fashion and to a revolution in showing fashion as well.»[16]

The silhouette was characterized by a small, nipped-in waist and a full skirt falling below mid-calf length, which emphasized the bust and hips, as epitomized by the ‘Bar’ suit from the first collection.[17][18] The collection overall showcased more stereotypically feminine designs in contrast to the popular fashions of wartime, with full skirts, tight waists, and soft shoulders. Dior retained some of the masculine aspects as they continued to hold popularity through the early 1940s, but he also wanted to include more feminine style.[19]

The New Look became extremely popular, its full-skirted silhouette influencing other fashion designers well into the 1950s, and Dior gained a number of prominent clients from Hollywood, the United States, and the European aristocracy. As a result, Paris, which had fallen from its position as the capital of the fashion world after World War II, regained its preeminence.[20][21] The New Look was welcomed in western Europe as a refreshing antidote to the austerity of wartime and de-feminizing uniforms, and was embraced by stylish women such as Princess Margaret in the UK.[citation needed] According to Harold Koda, Dior credited Charles James with inspiring The New Look.[22] Dior’s designs from the «New Look» did not only affect the designers in the 1950s, but also more recent designers in the 2000s, including Thom Browne, Miuccia Prada, and Vivienne Westwood. Dior’s evening dresses from that time are still referred to by many designers, and they have been seen in different wedding themed catwalks with multiple layers of fabric building up below the small waist (Jojo, 2011). Examples include Vivienne Westwood’s Ready-to-Wear Fall/Winter 2011 and Alexander McQueen’s Ready to Wear Fall/Winter 2011 (Jojo, 2011).[citation needed]

Not everyone was pleased with the New Look, however. Some considered the amount of material to be wasteful, especially after years of cloth rationing.[23] Feminists in particular were outraged, feeling that these corseted designs were restrictive and regressive, and that they took away a woman’s independence.[24] There were several protest groups against the designs including, the League of Broke Husbands, made up of 30,000 men who were against the costs associated with the amount of fabric needed for such designs. Fellow designer Coco Chanel remarked, «Only a man who never was intimate with a woman could design something that uncomfortable.»[21] Despite such protests, the New Look was highly influential, continuing to inform the work of other designers and fashion well into the 21st century.[14] For the 60th anniversary of the New Look in 2007, John Galliano revisited it for his Spring-Summer collection for Dior.[25] Galliano used the wasp waist and rounded shoulders, modernised and updated with references to origami and other Japanese influences.[25] In 2012 Raf Simons revisited the New Look for his debut haute couture collection for Dior, wishing to update its ideas for the 21st century in a minimalist but also sensual and sexy manner.[14][26] Simons’s work for Dior retained the luxurious fabrics and silhouette, but encouraged self-respect for the woman’s body and liberation of expression.[26] The design process for this collection, which was produced in only eight weeks, is documented in Dior and I, presenting Simons’s use of technology and modernist re-interpretations.[27]

Dior[edit]

Available references contradict themselves whether Christian Dior Parfums was established in 1947 or 1948. The Dior corporation itself lists the founding of Christian Dior Parfums as 1947, with the launch of its first perfume, Miss Dior.[6] Dior revolutionized the perfumery industry with the launch of the highly popular Miss Dior parfum, which was named after Catherine Dior (Christian Dior’s sister).[6] Christian Dior Ltd owned 25%, manager of Coty perfumes held 35%, and Boussac owned 40% of the perfume business, headed by Serge Heftler Louiche.[6] Pierre Cardin was made head of the Dior workshop from 1947 until 1950. In 1948, a New York City Christian Dior Parfums branch was established—this could be the cause of establishment-date issue.[6] The modern Dior corporation also notes that «a luxury ready-to-wear house is established in New York at the corner of 5th Avenue and 57th Street, the first of its kind,» in 1948.[6] In 1949, the «Diorama» perfume is released and[6] by 1949, the New Look line alone made a profit FFr 12.7 million.[11]

Expansion, and death of Christian Dior[edit]

Expansion from France began by the end of 1949 with the opening of a Christian Dior boutique in New York City. By the end of the year, Dior fashions made up 75% of Paris’s fashion exports and 5% of France’s total export revenue.[11]

In 1949, Douglas Cox from Melbourne, Australia, travelled to Paris to meet with Christian Dior to discuss the possibility of having Dior pieces made for the Australian market. Christian Dior and Douglas Cox signed a contract for Dior to produce original designs and for Douglas Cox to create them in his Flinders Lane workshop.[28] A young Jill Walker, still in her mid teens, was one of the many workers for Douglas Cox, a couture label now in the headlines in Australian newspapers almost daily. Jill would go onto forming a couture legacy in Melbourne with popular labels such as Jinoel and Marti with husband Noel Kemelfield.[29] The agreement between Dior and Douglas Cox really put Australian dressmaking on the global stage, yet ultimately the 60 Dior models proved to be too avant-garde for the conservative Australian taste. Douglas Cox was unable to continue the contract beyond the single 1949 season making these Dior-Cox couture pieces some of the most rare collectors items in Australian couture.[30]

In 1950, Jacques Rouët, the general manager of Dior Ltd, devised a licensing program to place the now-renowned name of «Christian Dior» visibly on a variety of luxury goods.[11] It was placed first on neckties[6] and soon was applied to hosiery, furs, hats, gloves, handbags, jewelry, lingerie, and scarves.[11] Members of the French Chamber of Couture denounced it as a degrading action for the haute-couture image. Nevertheless, licensing became a profitable move and began a trend to continue «for decades to come»,[11] which all couture houses followed.[6]

Also in 1950, Christian Dior was the exclusive designer of Marlene Dietrich’s dresses in the Alfred Hitchcock film Stage Fright. In 1951, Dior released his first book, Je Suis Couturier (I am a Couturier) through publishers Editions du Conquistador. Despite the company’s strong European following, more than half of its revenue was generated in the United States by this time.[11] Christian Dior Models Limited was created in London in 1952.[6] An agreement was made between the Sydney label House of Youth for Christian Dior New York models.[6] Los Gobelinos in Santiago, Chile, made an agreement with Dior for Christian Dior Paris Haute Couture.[6] The first Dior shoe line was launched in 1953 with the aid of Roger Vivier. The company operated firmly established locations in Mexico, Cuba, Canada, and Italy by the end of 1953.[11] As popularity of Dior goods grew, so did counterfeiting.[11] This illegal business was supported by women who could not afford the luxury goods.

By the mid-1950s, the House of Dior operated a well-respected fashion empire.[11] The first Dior boutique was established in 1954 at 9 Counduit Street. In honour of Princess Margaret and the Duchess of Marlborough, a Dior fashion show was held at the Blenheim Palace in 1954 as well. Christian Dior launched more highly successful fashion lines between the years of 1954 and 1957.[11] However, none came as close to the profound effect of the New Look.[11] Dior opened the Grande Boutique on the corner between Avenue Montaigne and Rue François Ier in 1955.[6] The first Dior lipstick was also released in 1955.[6] 100,000 garments had been sold by the time of the company’s 10th anniversary in 1956.[11] Actress Ava Gardner had 14 dresses created for her in 1956 by Christian Dior for the Mark Robson film The Little Hut.

Christian Dior appeared on the cover of TIME dated 4 March 1957. The designer soon afterwards died from a third heart attack on 24 October 1957.[6][11] The captivating impact of Dior’s creative fashion genius earned him recognition as one of history’s greatest fashion figures.[11] Kevin Almond for Contemporary Fashion wrote that «by the time Dior died his name had become synonymous with taste and luxury.»[11]

Dior without Christian Dior: 1957 through the 1970s[edit]

The death of the head designer left the House of Dior in chaos, and general manager Jacques Rouët considered shutting down operation worldwide. This possibility was not received graciously by Dior licensees and the French fashion industry; the Maison Dior was too important to the financial stability of the industry to allow such an action. To bring the label back on its feet, Rouët promoted the 21-year-old Yves Saint-Laurent to Artistic Director the same year.[11] Laurent had joined the House’s family in 1955 after being picked out by the original designer himself for the position of the first ever and only Head Assistant.[6][11] Laurent initially proved to have been the most appropriate choice after the debut of his first collection for Dior (the mention of Dior from this moment on refers to the company) in 1958.[11] The clothes were as meticulously made and perfectly proportioned as Dior’s in the same exquisite fabrics, but their young designer made them softer, lighter and easier to wear. Saint Laurent was hailed as a national hero. Emboldened by his success, his designs became more daring, culminating in the 1960 Beat Look inspired by the existentialists in the Saint-Germain des Près cafés and jazz clubs. His 1960 bohemian look was harshly criticized, and even more in Women’s Wear Daily.[11] Marcel Boussac was furious, and in the spring, when Saint Laurent was called up to join the French army—which forced him to leave the House of Dior—the Dior management raised no objection. Saint-Laurent left after the completion of six Dior collections.[6]

Christian Dior Haute Couture suit designed by Marc Bohan, spring/summer 1973.

Adnan Ege Kutay Collection

Laurent was replaced at Dior by designer Marc Bohan in late 1960. Bohan instilled his conservative style on the collections. He was credited by Rebecca Arnold as the man who kept the Dior label «at the forefront of fashion while still producing wearable, elegant clothes,» and Women’s Wear Daily, not surprisingly, claimed that he «rescued the firm.»[11] Bohan’s designs were very well esteemed by prominent social figures. Actress Elizabeth Taylor ordered twelve Dior dresses from Bohan’s Spring-Summer 1961 collection featuring the «Slim Look». The Dior perfume «Diorling» was released in 1963 and the men’s fragrance «Eau Sauvage» was released in 1966.[6] Bohan’s assistant Philippe Guibourgé launches the first French ready-to-wear collection «Miss Dior» in 1967. This is not to be confused with the already existing New York Ready-to-Wear store established in 1948. Designed by Bohan, «Baby Dior» opens its first boutique in 1967 at 28 Avenue Montaigne. The Christian Dior Coordinated Knit line is released in 1968 and management of the Fashion Furs Department of Christian Dior is taken by Frédéric Castet.[6] This year as well, Dior Parfums was sold to Moët-Hennessy (which would itself become LVMH) due to Boussac’s ailing textile company (the still-owner of Dior).[6][11] This, however, had no effect on the House of Dior operations, and so the Christian Dior Cosmetics business was born in 1969 with the creation of an exclusive line.

Following this, Bohan launched the first Christian Dior Homme clothing line in 1970. A new Dior boutique at Parly II was decorated by Gae Aulenti and the «Diorella» perfume was released in 1972. Christian Dior Ready-to-Wear Fur Collection was created in France in 1973, and then manufactured under license in the United States, Canada, and Japan.[6] The first Dior watch «Black Moon» was released in 1975 in collaboration with licensee Benedom. Dior haute-couture graced the bodies of Princess Grace of Monaco, Nicaraguan First Lady Hope Portocarrero, Princess Alexandra of Yugoslavia, and Lady Pamela Hicks (Lord Mountbatten of Burma’s younger daughter) for the wedding of The Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer. In 1978, the Boussac Group filed for bankruptcy and so its assets (including those of Christian Dior) were purchased by the Willot Group under the permission of the Paris Trade Court.[6] The perfume «Dioressence» was released in 1979.[6]

Arrival of businessman Arnault[edit]

A simple Dior Haute Couture evening gown designed by Marc Bohan, from the Spring 1983 collection

In 1980, Dior released the men’s fragrance «Jules».[6] After the Willot Group went into bankruptcy in 1981, Bernard Arnault and his investment group purchased it for «one symbolic franc» in December 1984.[6][11] The Dior perfume «Poison» was launched in 1985. That same year, Arnault became chairman, chief executive officer, and managing director of the company.[6] On assuming leadership, Arnault did away with the company’s mediocre textile operations, to focus on the Bon Marché department store and Christian Dior Couture. Operations for Christian Dior drastically changed for the better under Arnault. He repositioned it as the holding company Christian Dior S.A. of the Dior Couture fashion business.[11] On the 40th anniversary of Dior’s first collection, the Paris Fashion Museum dedicated an exhibition to Christian Dior.[6] In 1988, Arnault’s Christian Dior S.A.’s took a 32% equity stake into the share capital of Moët-Hennessy • Louis Vuitton through its subsidiary Jacques Rober, creating what would become one of the leading and most influential luxury goods companies in the world. Under this milestone merger, the operations of Christian Dior Couture and Christian Dior Parfums were once again united. Italian-born Gianfranco Ferré replaced Bohan as head designer in 1989.[11] The first such non-Frenchman, Ferré left behind traditional Dior associations of flirtation and romance, and introduced concepts and a style described as «refined, sober and strict.»[11] Ferré headed design for Haute Couture, Haute Fourrure, Women’s Ready-to-Wear, Ready-to-Wear Furs and Women’s Accessories collections. His first collection was awarded the Dé d’Or in 1989.[6] That year, a boutique was opened in Hawaii and the LVMH stake by Jacques Rober rose to 44%.[6]

Further Dior boutiques were opened in 1990 in upscale New York City, Los Angeles, and Tokyo shopping districts. The stake in LVMH rose again, to 46%.[6] Another collection of watches named «Bagheera» – inspired by the round design of the «Black Moon» watches – was also released in 1990. Having fired the company’s managing executive Beatrice Bongbault in December 1990, Arnault took up that position until September 1991, when he placed former Bon Marché president Phillipe Vindry at the post.[11] In 1991, Christian Dior was listed on the spot market and then on the Paris Stock Exchange’s monthly settlement market, and the perfume «Dune» was launched.[6] Vindry dropped ready-to-wear prices by 10%. Still, a wool suit from Dior would come with a price label of USD 1,500.[11] 1990 revenue for Dior was USD 129.3 million, with a net income of $22 million.[11] Dior was now reorganized into three categories: 1) women’s ready-to-wear, lingerie, and children’s wear 2) accessories and jewelry 3) menswear. Licensees and franchised boutiques were starting to be reduced, to increase the company’s control over brand product. Licensing was in fact reduced by nearly half because Arnault and Vindry opted «for quality and exclusivity over quantity and accessibility.»[11] Wholly company-owned boutiques now opened in Hong Kong, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Cannes, and Waikiki, adding to its core stores located in New York City, Hawaii, Paris and Geneva. This held a potential to increase direct sales and profit margins while maintaining high-profile locations.»[11] In 1992, Dior Homme was placed under the artistic direction of Patrick Lavoix, and the «Miss Dior» perfume was relaunched.[6] Francois Baufume succeeded Vindry in 1993 and continued to reduce licenses of the Dior name.[11]

Leather gloves by Christian Dior

The production of Dior Haute Couture was spun off into a subsidiary named Christian Dior Couture in 1995.[6] Also, the «La Parisienne» watch model was released – embodied in the watch «Parisian Chic». By that year, revenue for the label rose to USD 177 million, with a net income of USD 26.9 million.[11] Under the influence of Anna Wintour, editor and chief of Vogue, CEO Arnault appointed British designer John Galliano to replace Gianfranco Ferré in 1997 (Galliano on CBS News: «without Anna Wintour I would certainly not be at the house of Dior»).[6][31] This choice of a British designer, once again instead of a French one, is said to have «ruffled some French feathers». Arnault himself stated that he «would have preferred a Frenchman», but that «talent has no nationality».[11] He even compared Galliano to Christian Dior himself, noting that «Galliano has a creative talent very close to that of Christian Dior. He has the same extraordinary mixture of romanticism, feminism, and modernity that symbolised Monsieur Dior. In all of his creations – his suits, his dresses – one finds similarities to the Dior style.»[11] Galliano sparked further interest in Dior with somewhat controversial fashion shows, such as «Homeless Show» (models dressed in newspapers and paper bags) or «S&M Show».[11] Meanwhile, Dior licenses were being reduced further by new president and CEO Sidney Toledano.[11] On 15 October 1997, the Dior headquarters store on Avenue Montaigne was reopened –it had been closed and remodeled by Peter Marino – in a celebrity-studded event including Nicole Kidman, Demi Moore and Jacques Chirac. That year, Christian Dior Couture also took over all thirteen boutique franchises from Japan’s Kanebo.[6]

In May 1998, another Dior boutique was opened in Paris. This time the store opened its doors on the Left Bank, Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Also this year, Victoire de Castellane became lead designer of Dior Fine Jewellery and the first Dior Fine Jewellery boutique opened in New York City. Paris itself would witness the opening of the first Parisian Dior Fine Jewellery boutique the following year, at 28 Avenue Montaigne.[6] The perfume «J’adore» was released in 1999,[6] and on 5 October 1999, Galliano released the Dior Spring-Summer 2000 ready-to-wear fashion show, debuting the new Saddle bag. In the same year, Dior’s long watch partner Benedom joined the LVMH group. In 2000, Galliano’s leadership was extended to Ready to wear, accessories, advertising and communications. The first campaign under his leadership was photographed by Nick Knight and featured two women simulating intercourse.

While other brands in the late 1990s, notably Gucci,[32] had resorted to porn chic as a mean to draw attention, Dior ads had such an impact that porn chic became a trend in most fashion ads. Galliano ignited the escalation of porno chic advertisements, which culminated with Ungaro’s zoophilic ads,[33] shot by Mario Sorrenti, and Gucci’s ads, which featured a model with pubic hair shaped like the signature Gucci logo. As a matter of fact, it is considered that Galliano had revolutionized Dior more through his advertising campaigns than through his designs.[34][35]

On 17 July 2000, Dior Homme lead designer Patrick Lavoix was replaced by Hedi Slimane. Notable Dior releases that year were watches such as the distinctive «Malice», which features bracelets made of «CD» links, as well as the «Riva». Hedi left Dior Homme in 2007 and replaced by Kris Van Assche.

21st century[edit]

In 2001, the Dior Homme boutique on 30 Avenue Montaigne reopened with a new «contemporary masculine concept» instilled by its designer Hedi Slimane. Slimane used this concept in the creation of his first Dior Homme collection.[6] Soon, Dior Homme gained prominent male clientele including Brad Pitt and Mick Jagger.[11]

John Galliano then began to release his own Dior watches in 2001, beginning with the «Chris 47 Aluminum» line, marking a new era in Dior watch design. Next, the «Malice» and «Riva» watches were redesigned with precious stones to create the «Malice Sparkling» and «Riva Sparkling» spin-off collections. Inspired by the Spring-Summer 2002 Ready-to-Wear collection, Dior released the «Dior 66» watch, breaking many feminine traditional expectations in design.

The Dior flagship boutique in the upscale Ginza shopping district of Tokyo. First opened in 2004.

The men’s fragrance «Higher» was released in 2001, followed by the perfume «Addict» in 2002. The company then opened Milan’s first Dior Homme boutique on 20 February 2002. By 2002, 130 locations were in full operation.[11] On 3 June 2002, Slimane was presented with the «International Designer of the Year» award by the CFDA. Until 2002, Kanebo was the Christian Dior ready-to-wear license holder in Japan and, when the license expired, Christian Dior was able to profitable directly sell its ready-to-wear and accessories in its own boutiques.[36] The «Chris 47 Steel» watch was released in 2003 as a cousin of the original «Chris 47 Aluminum». Bernard Arnault, Hélène Mercier-Arnault, and Sidney Toledano witnessed the opening of the Dior flagship boutique in the Omotesandō district of Tokyo on 7 December 2003. The second Dior flagship store was opened in the upscale Ginza shopping district of Tokyo in 2004.[6] An exclusive Dior Homme boutique was opened also that year in Paris on Rue Royale, and it presented the entire Dior Homme collection. A second Dior Fine Jewelry boutique in Paris was opened at 8 Place Vendôme.[6] A Christian Dior boutique was opened in Moscow after the company took control of licensed operations of its Moscow agent.[6]

The designer of Dior Fine Jewelry Victoire de Castellane launched her own watch named «Le D de Dior» (French: «The D of Dior»). signifying the entrance of Dior watches into its collection of fine Jewelry. This watch was designed for women but made use of many design features which are typically thought of as masculine. Slimane next released a watch for the Dior Homme collection called «Chiffre Rouge.» This special watch included the signature look of Dior Homme: «Watch design and technology match each other inseparably, to create the perfect expression of Dior Homme’s artistic excellence and to increase the watchmaking legitimacy of Dior timepieces.» De Castellane then launched her second line of watches called «La Baby de Dior». The design for this line was meant to be more feminine with more of a «jewelry look.»

The «Miss Dior Chérie» perfume and the «Dior Homme» fragrance were released in 2005.[6] Galliano released his «Dior Christal» watches in which he combined steel and blue sapphires to create a «creative and innovative collection.» Christian Dior S.A. then celebrated the 13th anniversary of Dior Watches in 2005, and, in April of that year, its «Chiffre Rouge» collection was recognized by the World Watches and Jewelry Show in Basel, Switzerland. Also in the year, the fashion house also celebrated the 100th anniversary of the birthday of designer Christian Dior.[6] An exhibition, «Christian Dior: Man of the Century,» was held in the Dior Museum in Granville, Normandy.

In 2006, the Dior watch booth was dedicated to the Dior Canework. This pattern was made by designer Christian Dior and based on the Napoleon III chairs used in his fashion shows.

In 2007, Kris Van Assche was appointed as the new artistic director of Dior Homme. Van Assche presented his first collection later that year.[6] The 60th Anniversary of the founding of the Maison Dior was officially celebrated in 2007 as well.[6]

By February 2011, the House of Dior was in scandal after accusations of John Galliano making anti-Semitic remarks made international headlines: the company found itself in a «public relations nightmare.»[37] Galliano was fired in March and the scheduled presentation of his Fall-Winter 2011/2012 ready-to-wear collection went ahead without him, amid the controversy, on 4 March.[38] Before the start of the show, chief executive Sydney Toledano gave a sentimental speech on the values of Christian Dior and alluded to the family’s ties to The Holocaust.[39] The show closed with the staff of the atelier coming out to accept applause in the absence of their artistic director. (The previous January 2011 presentation of Spring-Summer 2011 haute-couture was the last appearance of Galliano on the Dior runway.) The company went on ahead and appointed Bill Gaytten as head designer interim in absence of artistic director.[40] Gaytten had worked under Galliano for Dior and for the John Galliano label. The first haute-couture collection (for the Fall-Winter 2011 season) under Gaytten’s management was presented in July and was received with mainly negative reviews.[41][42] Meanwhile, speculation remained for months as it was unknown who would be selected to replace Galliano. During its 13-month period of having no artistic director, Dior began undergoing subtle changes in its designs as the influence of the theatrical and flamboyant Galliano faded. The all-new resigned dior.com was launched in late 2011.

There is a subtext to this New New Look that goes beyond respect for the house’s esteemed founder. In one fell swoop, John Galliano has been all but removed from the Dior history books. By making a visual connection between his era and that of Christian Dior himself, Raf Simons has redrawn the line of succession. The unimpeachable codes of Dior are illustrated for a new generation; the bias-cut dresses and Kabuki styling of Galliano downgraded to a footnote.

—Critic surmising the meaning of Simons’ premier collection for Dior[43]

On 23 January 2012, Gaytten presented his second haute-couture collection (for the Spring-Summer 2012 season) for Dior and it was much better received than his first collection.[44]

Belgian designer Raf Simons was announced, on 11 April 2012, as the new artistic director of Christian Dior. Simons was known for his minimalist designs,[43] and this contrasted against the dramatic previous designs of Dior under Galliano. Furthermore, Simons was seen to have emerged as a «dark horse» amid the names of other designers who were considered high contenders.[37] To emphasize the appropriate choice of Simons as the right designer, the company ostentatiously made comparisons between Simons and the original designer Christian Dior.[45] Reportedly, Bernard Arnault and fellow executives at Dior and LVMH were keen to move Dior from the Galliano years.[37] Simons spent much time in the Dior archives[46] and familiarizing himself with haute-couture (as he had no previous background in that niche of fashion).[37] Simons was then scheduled to debut his designs in July. Meanwhile, Gaytten’s Spring-Summer 2012 haute-couture collection was presented as the first Dior haute-couture show ever to be held in China on 14 April in Shanghai;[47] and it was a mark of the company’s devotion to its presence in the Chinese market.

The show was the last presentation by Gaytten for Dior, and he remained as head designer for the John Galliano label.[48]

On 3 May, the Dior: Secret Garden – Versailles promotional film was launched.[49]

It was highly buzzed about throughout various industry and social media sources as it was a display of Dior through its transition. Simons presented his first ever collection for the company – the Fall-Winter 2012 haute-couture collection – on 2 July. A major highlight of the fall-winter 2012 haute-couture shows,[37][46][50] the collection was called by the company as «the new couture» and made reference to the start of a new Dior through the work of Simons «wiping the [haute couture] slate clean and starting again from scratch.»[51] The designer’s collection «made more references to Mr Dior than to the house of Dior»[43] with pieces harkening back to themes Dior’s post-WWII designs introduced to fashion.[37] Simons, who rarely makes himself available for interviews, gave an interview published by the company through its Dior Mag online feature.[52] While previous runway presentations under Galliano were held at the Musée Rodin, Simons’ show was held at a private residence, near the Arc de Triomphe, with the address only disclosed to select top-clients, celebrities, journalists, and other personnel exclusively invited in a discreet affair.[53] High-profile figures in attendance included designers Azzedine Alaïa,[37][46] Pierre Cardin,[37][54] Alber Elbaz (Lanvin designer),[37][43][46] Diane von Fürstenberg,[37][43][54] Marc Jacobs,[37][43][54] Christopher Kane,[37][43] Olivier Theyskens,[46] Riccardo Tisci,[37][54] Donatella Versace;[37][43][46][54] and Princess Charlene of Monaco,[37] actresses Marion Cotillard,[37] Mélanie Laurent,[37] Jennifer Lawrence,[37] Sharon Stone; film producer Harvey Weinstein;[46] and Dior chairman Arnault with his daughter.[37] Live satellite feed of the show was provided on DiorMag online and Twitter was also implemented for real time communication.[53] By then, it was also known that the company had purchased the Parisian embroidery firm Maison Vermont sometime earlier in 2012.[43]

In March 2015 it was announced that Rihanna was chosen as the official spokeswoman for Dior; this makes her the first black woman to take the spokeswoman position at Dior.[55] In 2015, Israeli model Sofia Mechetner was chosen to be the new face of Dior.[56]

In 2016, Maria Grazia Chiuri was named the women’s artistic director for Dior.[57]

In April 2016 a new Dior flagship boutique opened in San Francisco, with a party hosted by Jaime King.[58]

In 2017, Dior renovated and expanded its Madrid store. The brand celebrated the opening of the new boutique in a masked ball attended by a number of Spanish celebrities like Alejandro Gómez Palomo.[59]

In March 2018, Kim Jones was named the men’s artistic director for the house.[60] Under his management Dior has made several high profile streetwear collaborations. Jones first show for Dior featured American artist and designer Brian Donnelly aka KAWS. Thereafter followed collaborations with Raymond Pettibon, 1017 ALYX 9SM, Yoon Ahn, Hajime Sorayama, Daniel Arsham, Sacai and most recently Shawn Stussy, creator of the legendary streetwear brand Stüssy.[61]

In October 2019, Dior apologized to China for using a map of China that excluded Taiwan.[62]

On 11 March 2022, 30 Avenue Montaigne has once again opened its doors to the public.[63] The property was closed for two years for a major renovation led by architect Peter Marino.[63] Historically, 30 Avenue Montaigne is the place where Christian Dior showcased his first collection.[63]

Celebrity «ambassadors»[edit]

Dior has created strong partnerships with Hollywood celebrities and social media influencers, working closely with these individuals to reach more demographics and re-establish its identity as a new, modern brand, despite the fact that it has been around for a while.[64] This has allowed the brand to portray a more populist image and attract a wider audience.[65] The brand has worked with and dressed contemporary style icons like Jennifer Lawrence and Lupita Nyong’o, who may resonate with millennials.[66] Dior has effectively implemented social media into their marketing communication strategy, in which images and videos from campaigns are shared on both the official Dior profile, and on the celebrity ambassadors’ social media pages.

An example of this success is seen in the Secret Garden campaign featuring Rihanna.[67] In this campaign, Rihanna is seen dancing to a song from her album (Only If For a Night) through a hall of mirrors.[68] By being associated with Rihanna’s song, the company created a sense of association with her brand, which was beneficial to the company as she was ranked as the most marketable celebrity in 2016.[69] Despite the reach not being completely suitable to the Dior target audience, collaborating with the likes of Rihanna allows the company to engage with more of the market, as Rihanna’s social media following is four times larger than that of the fashion house.[65]

Below are some of the celebrity ambassadors who have fronted Dior campaigns:

- Isabelle Adjani: Poison perfume (1985–1990s)[70]

- Carla Bruni: Lady Dior handbag (1996)[71]

- Milla Jovovich: Hypnotic Poison perfume (1999–2000)[72]

- Charlize Theron: J’Adore Dior perfume (2004–present)

- Sharon Stone: Capture skincare (2005–present)[73]

- Monica Bellucci: Dior cosmetics (2006–2010),[74][75] Lady Dior handbag (2006–2007), Hypnotic Poison perfume (2009–2010)[76]

- Eva Green: Midnight Poison (2007–2008)[77]

- Marion Cotillard: Lady Dior handbag (2008–2017),[78][79] Miss Dior handbag (2011)[80]

- Jude Law: Dior Homme fragrance (2008–2012)[81]

- Natalie Portman: Miss Dior fragrance, Dior cosmetics (2010–present)[82][83]

- Mélanie Laurent: Hypnotic Poison perfume (2011–present)[84]

- Mila Kunis: Miss Dior handbag (2012)[85]

- Jennifer Lawrence: Miss Dior handbag (2012–present),[86] Joy by Dior fragrance (2018–present)[87]

- Robert Pattinson: Dior Homme fragrance (2013–present)[88]

- Rihanna: Diorama bag, J’adore Dior perfume, Dior sunglasses (2015–present)[89][90]

- Johnny Depp: Dior Sauvage fragrance (2015–present)[91]

- Angelababy: DiorAmour collection (2017–present)[92]

- Cara Delevingne: DIOR Addict Stellar Shine Lipstick. BE DIOR. BE PINK. (2019)[93][94]

- Kim Jisoo: Dior Global Fashion Muse (2020–present); Dior Global Ambassador for Fashion and Beauty (2021–present)[95]

- Yara Shahidi: Dior Global Brand Ambassador (2021–present); Face of Dior for Fashion and Cosmetics (2021–present)[96][97]

- Oh Se-hun: Dior Global Ambassador (2021–present); Face of Dior for Fashion (2021–present)[98]

- Kylian Mbappé brand ambassador of the men’s collection including Sauvage fragrance[99]

Fashion shows[edit]

| Fashion show | Date | Models in order of appearance | Soundtrack | Theme | Creative director |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring 2020 Ready-to-Wear | 20 January 2020 | Maria Grazia Chiuri | |||

| Pre-Fall 2020 | 11 December 2019 | ||||

| Spring 2017 Ready-to-Wear | 30 September 2016 | ||||

| Resort 2017 | 31 May 2016 | Serge Ruffieux & Lucie Meier | |||

| Fall 2016 Ready-to-Wear | 4 March 2016 | ||||

| Spring 2003 Couture | 19 January 2003 | John Galliano | |||

| Spring 2001 Ready-to-Wear | — | ||||

| Fall 2000 Couture | 28 July 2000 | ||||

| Fall 2000 Ready-to-Wear | 28 February 2000 | ||||

| Spring 2000 Ready-to-Wear | — | ||||

| Fall 1999 Couture | 19 July 1999 | ||||

| Spring 1998 Couture | — |

Financial data[edit]

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 29.881 | 30.984 | 35.081 | 37.968 | 43.666 |

| Net Income | 3.926 | 3.883 | 6.165 | 4.164 | 5.753 |

| Assets | 55.555 | 61.161 | 60.030 | 62.904 | 72.762 |

| Employees | 2535 | 2780 | 3033 | 3100 | 3800 |

Criticism[edit]

2000s[edit]

In 2000, Galliano’s collection inspired by homeless people drew criticism, but also attention, to the house of Dior.[101]

2010s[edit]

In early 2011, scandal arose when John Galliano was accused of making anti-semitic comments after drinking in Paris. Footage was released of the designer under the influence of alcohol saying «I love Hitler» and «People like you would be dead today. Your mothers, your forefathers would be fucking gassed and dead» to a non-Jewish woman.[102] In France, it is against the law to make anti-semitic remarks, and is punishable by up to six months in prison.[102] On 1 March 2011, Christian Dior officially announced that it had fired Galliano amidst the controversy.[103]

Plagiarism and cultural appropriation controversies[edit]

2017[edit]

In 2017, Dior was accused of cultural appropriation by directly plagiarizing a Bihor coat, a traditional Romanian vest, by using the same colour and patterns in its pre-fall collection; Dior had presented it as their original designs without giving any credit to the people of Bihor nor crediting the Romanian people as source of inspiration.[104][105] As a result, Romanian people were outraged and to fight against this cultural appropriation, a compaign was launched by Romanian fashion magazine Beau Monde who then recruited native craftsmen and fashion designers from Bihor to create a new line of fashion.[104] The cover of the Beau Monde magazine read:[105]

Don’t let traditions go out of stock. Support the fashion from Bihor and buy authentic creations from Bihorcouture.com

— Beau Monde

Thus, the online platform named Bihor Couture was launched; Bihor Couture also publicly shamed Dior for «theft» and sold original artisan-made versions of the traditional Romanian vest.[104]

2022[edit]

In April 2022, Dior released a new midi-skirt in Seoul, Dior’s art director Maria Grazia Chiuri described the 2022 Fall collection design was inspired by school uniform (including pleated skirts), also in honour of Catherine Dior.[106] This new skirt was plain black wrap-around skirt which was made of two panels of fabric which was sewn to the waistband of the skirt; it featured four flat panels with no pleats (one at each side of each panel of fabric) and pleats; it was constructed in an overlapping fashion such that there was two overlapping flat surface at the back and front and side pleats when worn.[107][106] On its official website page, this skirt was described as «a hallmark Dior silhouette, the mid-length skirt is updated with a new elegant and modern variation […]».[108]

Three month later, this skirt was noticed by some Hanfu enthusiasts, who criticized it as being created by copying the mamianqun design.[109] They also indicated that this skirt have the exact same cut and construction as the mamianqun with only its length being the difference from the orthodox-style and historical mamianqun of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD).[106][110] It was, however, noted by Chinese netizens that the 21st modified, modern version of the mamianqun, also included midi-mamianqun, had been designed in the past years by Chinese Hanfu designers.[111][110]

Dior decided to stop this sale in Mainland China to avoid controversy. On July 23, about 50 Chinese overseas students in Paris, France, made a protest in front of a Dior flagship store at the Champs-Élysée,[112][113] they used the slogan «Dior, Stop Cultural Appropriation» and «This is a traditional Chinese dress» written with a mixture of French and English;[114] they also called for other overseas students from the United Kingdom and the United States for relay, the Communist Youth League of China also expressed support for this protest.[115] There are also more than 10 Chinese democratic activists lifted banners writing «Skirt Rights Is Bigger Than Human Rights» etc. for anti-ptotest. And both sides started a conflict with each other. Chinese news media initially have no mention for anti-protest but focused on cultural embezzling accuse.[116] Chinese network also spread a theory that the democracy activists were composed by Taiwanese.[117]

Some French news media commented this was largely due to Dior does not describe its origin for sale with transparency, most criticize views argued that Dior did not respect to Chinese traditions.[118] According to the Journal du Luxe, a French news media, the adoption of the mamianqun cut and construction design by Dior was not the main issue of the debate and critics but rather on the absence of transparency surrounding the origins of the inspirations behind the skirt design.[118] Some Chinese netizens also criticized Dior on Weibo with comments, such as «Was Dior inspired by Taobao?»[119] while another Instagram user commented on the official Dior account:[118]

«Les références culturelles à notre pays [Chine] sont plus que bienvenues mais cela ne signifie pas pour autant que vous pouvez détourner notre culture et nier le fait que cette jupe est chinoise !»

[transl. »Taking cultural references from our country [i.e. China] is more than welcomed; however, this does not meaning that you can appropriate our culture and deny the fact that this skirt is Chinese !»].— Instagram user, in Journal du Luxe, Dior : une polémique entre appropriation et transparence culturelle, published on July 21st 2022

Dior was accused of cultural appropriation for a second time in July 2022 for due to its usage of pattern print which looks like the huaniaotu (Chinese: 花鸟图; lit. ‘bird-and-flower painting’) into its 2022 autumn and winter ready-to-wear collection having introduced it as being Dior’s signature motif Jardin d’Hiver, which was inspired by Christian Dior’s wall murals;[120] the huaniaotu is a traditional Chinese painting theme which belong to the Chinese scholar-artist style in Chinese painting and originated in the Tang dynasty.[121]

Ownership and shareholdings[edit]

At the end of 2010, the only declared major shareholder in Christian Dior S.A. was Groupe Arnault SAS, the family holding company of Bernard Arnault. The group’s control amounted to 69.96% of Dior’s stock and 82.86% of its voting rights.[122] The remaining shares are considered free float.[122]

Christian Dior S.A. held 42.36% of the shares of LVMH and 59.01% of its voting rights at the end of 2010. Arnault held an additional 5.28% of shares and 4.65% of votes directly.[7]

Creative directors[edit]

- Christian Dior – 1946–1957

- Yves Saint Laurent – 1957–1960

- Marc Bohan – 1960–1989

- Gianfranco Ferré – 1989–1997

- John Galliano – 1997–2011

- Bill Gaytten – 2011–2012

- Raf Simons – 2012–2015

- Serge Ruffieux & Lucie Meier 2015–2016

- Maria Grazia Chiuri (women’s) – 2016–present

- Hedi Slimane (men’s) – 2000–2007

- Kris Van Assche (men’s) – 2007–2018

- Kim Jones (men’s) – 2018–present

Retail locations[edit]

The company operates a total of 210 locations as of September 2010[citation needed]:

- Asia: 109

- Africa: 1 (Casablanca, Morocco)

- Caribbean: 1 (San Juan, Puerto Rico)

- Europe: 45

- Central America (Panama): 1

- Middle East: 8

- North America (Canada, Mexico, and the United States): 48

- Oceania: 6

- South America (Brazil, Argentina): 4

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Christian Dior SE – bylaws» (PDF). dior-finance.com. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b «Christian Dior». Infogreffe. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ «Pietro Beccari». The Business of Fashion. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Paton, Elizabeth (19 March 2018). «Dior Confirms Kim Jones as Men’s Wear Artistic Director». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f «Christian Dior Annual Report». Christian Dior SE. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Company History at Dior’s website Archived 7 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b «LVMH – Reference Document 2010» (PDF). LVMH. pp. 241–242. Retrieved 29 May 2011.[permanent dead link] Financière Jean Goujon, «a wholly owned subsidiary of Christian Dior», held 42.36% of capital and 59.01% of voting rights within the company at the end of 2010.

- ^ Gay Forden, Sara; Bauerova, Ladka (5 February 2009). «LVMH Cuts Store Budget After Profit Misses Estimates». Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Godfrey Deeny (8 November 2017). «Sidney Toledano quitte Christian Dior et sera remplacé par Pietro Beccari». Fashion Network.

- ^ «Christian Dior», by Bibby Sowray, Vogue magazine, 5 April 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq «History of Christian Dior S.A.» fundinguniverse.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ Pochna, Marie-France; Savill, Joanna (translator) (1996). Christian Dior : the man who made the world look new (1st English language ed.). New York: Arcade Pub. Dior was reportedly introduced to Boussac by Jean Choplin, the founder of AIESEC and marketing director of Boussac. pp. 90–92. ISBN 9781559703406.

- ^ a b Dior. (1947). The New Look, a legend. Retrieved, from http://www.dior.com/couture/en_hk/the-house-of-dior/the-story-of-dior/the-new-look-revolution Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Mistry, Meenal (1 March 2012). «Spring’s new look: Sixty-five years ago, Christian Dior started a revolution that’s still influencing the designers of today». Harper’s Bazaar.

- ^ Palmer, A., & Palmer, A. (2009). Dior.

- ^ Best, K. (2017). The history of fashion journalism. London: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- ^ «The Golden Age of Couture – Exhibition Highlights: ‘Bar’ Suit & Hat – Christian Dior». Victoria & Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ «Christian Dior: «Bar» suit» (C.I.58.34.30_C.I.69.40) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/C.I.58.34.30_C.I.69.40 Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. (October 2006) (Accessed 13 February 2014).

- ^ Sessions, D. (26 June 2017). «1940s Fashion History for Women and Men». Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Sebba, Anne (29 June 2016). «How Haute Couture rescued war torn Paris». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b Zotoff, Lucy (25 December 2015). «Revolutions in Fashion: Christian Dior». Haute Couture News. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Feitelberg, Rosemary (11 February 2014). «The Costume Institute Previews ‘Charles James: Beyond Fashion’«. WWD. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ The United Kingdom endured severe rationing for many years after World War II ended. According to the Imperial War Museum, the government stopped clothes rationing in March 1949.

- ^ Tomes, Jan (10 February 2017). «The New Look: How Christian Dior revolutionized fashion 70 year [sic] ago». Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b Alexander, Hilary (23 January 2007). «Galliano’s new look at the New Look». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ a b Menkes, Suzy (28 September 2012). «At Dior, a Triumph of 21st Century Modernism». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Lemire, Christy. «Dior and I Movie Review & Film Summary (2015)». Roger Ebert. Ebert Digital. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ «The Age – Google News Archive Search». news.google.com.

- ^ Singer, Melissa (4 June 2016). «Photographer in race to document ‘living history’ of Melbourne fashions of the 1950s». The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ «The Sydney Morning Herald – Google News Archive Search». news.google.com.

- ^ «Anna Wintour, Behind The Shades». CBS News. 14 May 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Tom Ford’s latest Gucci shocker is approved by the Advertising Standards Authority (Vogue.com UK) Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Vogue.co.uk (27 February 2003). Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ «Image». Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ The CROWD blog Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Thecrowdblog.blogspot.com. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Vilnet Interview Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Thecrowdmagazine.com. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Chevalier, Michel (2012). Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-17176-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Horyn, Cathy (2 July 2012). «Past, Prologue, Dior». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Moss, Hilary (4 March 2011). «Dior Autumn/Winter 2011 Show Goes on Without John Galliano (PHOTOS)». Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ «Sidney Toledano’s emotional speech at Christian Dior show». The Daily Telegraph. London. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ A New Era, Vogue.co.uk, 27 June 2011, archived from the original on 16 September 2016, retrieved 2 September 2016

- ^ Thakur, Monami (15 April 2012). «Bill Gaytten’s Spring Summer 12 Haute Couture Shanghai Show for Dior [Pictures]». International Business Times. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Odell, Amy (5 July 2011). «Dior Couture Suffers Without John Galliano». New York. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cartner-Morley, Jess (2 July 2012). «Raf Simons puts doubts at rest with first show at Christian Dior». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Cowels, Charlotte (23 January 2012). «Bill Gaytten’s Dior Couture Show Was Much Better Than Last Season’s». New York. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ «Welcome Mr Simons». Christian Dior. 11 April 2012. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Givhan, Robin (2 July 2012). «Raf Simons Debuts at Christian Dior With Couture Collection». The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ «Night Falls Over Shanghai». Christian Dior. 15 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Bergin, Olivia (16 April 2012). «LVMH chief Sidney Toledano on how the stars have aligned at Dior, as Bill Gaytten bows out in China». London: Telegraph UK. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ «Secret Garden». Christian Dior. 3 May 2012. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ «Simons Changes Face Christian Dior Couture». Calgary Herald. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ «The New Couture». Christian Dior. 3 July 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ «After Show». Christian Dior. 3 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b «Live». Christian Dior. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Adamson, Thomas. «Raf Simons changes the face of Christian Dior in couture day 1». Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Avery Thompson (14 March 2015). «Rihanna’s Dior Campaign: Singer Is First Black Woman To Be Face of Iconic Brand». Hollywood Life. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ How a 14-year-old Israeli became the new face of Christian Dior Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine By Ruth Eglash, The Washington Post Sunday, 12 July 2015

- ^ «Dior’s feminist designer awarded French Legion of Honour». The Independent. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ Matthews, Damion (23 April 2016). «See What Happened at Dior’s San Francisco Premiere». SFLUXE. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Diderich, Joelle (23 November 2017). «Dior Celebrates Reopening of Madrid Store». WWD. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Paton, Elizabeth (19 March 2018). «Dior Confirms Kim Jones as Men’s Wear Artistic Director». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ «Dior Collaborations: A Full Timeline». Highsnobiety. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «The NBA landed in hot water after the Houston Rockets GM supported the Hong Kong protests. Here are other times Western brands caved to China after offending the Communist Party». Business Insider. 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b c «Dior’s 30 Avenue Montaigne reopens». gulfnews.com. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ «Why Gucci’s Digital Strategy Is Working». Centric Digital. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b Scott, Mark (1 December 2015). «Luxury Brands and the Social Campaign». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ «Red Carpet Retrospective: Dior». Vogue. 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ «Here’s Your First Look at Rihanna’s Groundbreaking Dior Campaign». InStyle.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ Iredale, Jessica (13 May 2015). «Rihanna’s ‘Secret Garden’ Campaign for Dior Set to Debut». WWD. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ «How Rihanna became the most brand savvy celebrity». wgsn.com/blogs. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ «From Isabelle Adjani to Rihanna: 30 years of Dior ambassadors». Yahoo. 16 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Iconic bags – Lady Dior». Trendissimo. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ «Christian Dior – Milla Jovovich». Milla Jovovich Official Website. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Sharon Stone is confirmed as the new face of Christian Dior». British Vogue. 4 October 2005. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Bellissimo Bellucci». MiNDFOOD. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Rouge Dior at Rinascente». Vogue. 21 September 2010.

- ^ «Advertising Campaigns > Dior». La Bellucci. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ «Eva Green’s Midnight Poison Dior Fragrance ad campaign». Sassy Bella. 4 July 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ «Marion Cotillard’s Next Role: Dior Bag Lady». People. 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «2017 Cannes Film Festival: Marion Cotillard on Supporting Young Designers». WWD. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ «Marion Cotillard for Miss Dior Handbags Fall 2011». Luxuo. 9 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Jude Law is new face at Christian Dior». Marie Claire. 4 April 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Miss Dior Chérie with Natalie Portman Perfume». 29 July 2013. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ «Natalie Portman Signs With Christian Dior». British Vogue. 7 June 2010. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ «Dior Taps Mélanie Laurent for Hypnotic Poison Campaign». FashionEtc.com. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2016.