Tux the penguin, the mascot of Linux[1] |

|

| Developer | Community contributors, Linus Torvalds |

|---|---|

| Written in | C, assembly languages, and others |

| OS family | Unix-like |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | September 17, 1991; 31 years ago |

| Repository | git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/ |

| Marketing target | Cloud computing, embedded devices, mainframe computers, mobile devices, personal computers, servers, supercomputers |

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Platforms | Alpha, ARC, ARM, C-Sky, Hexagon, IA-64, LoongArch, m68k, Microblaze, MIPS, Nios II, OpenRISC, PA-RISC, PowerPC, RISC-V, s390, SuperH, SPARC, x86, Xtensa |

| Kernel type | Monolithic |

| Userland | GNU[a], BusyBox[b] |

| Default user interface |

|

| License | GPLv2[9][c]) |

| Articles in the series | |

| Linux kernel Linux distribution |

Linux ( LEE-nuuks or LIN-uuks)[11] is a family of open-source Unix-like operating systems based on the Linux kernel,[12] an operating system kernel first released on September 17, 1991, by Linus Torvalds.[13][14][15] Linux is typically packaged as a Linux distribution, which includes the kernel and supporting system software and libraries, many of which are provided by the GNU Project. Many Linux distributions use the word «Linux» in their name, but the Free Software Foundation uses the name «GNU/Linux» to emphasize the importance of GNU software, causing some controversy.[16][17]

Popular Linux distributions[18][19][20] include Debian, Fedora Linux, and Ubuntu, the latter of which itself consists of many different distributions and modifications, including Lubuntu and Xubuntu. Commercial distributions include Red Hat Enterprise Linux and SUSE Linux Enterprise. Desktop Linux distributions include a windowing system such as X11 or Wayland, and a desktop environment such as GNOME or KDE Plasma. Distributions intended for servers may omit graphics altogether, or include a solution stack such as LAMP. Because Linux is freely redistributable, anyone may create a distribution for any purpose.[21]

Linux was originally developed for personal computers based on the Intel x86 architecture, but has since been ported to more platforms than any other operating system.[22] Because of the dominance of the Linux-based Android on smartphones, Linux, including Android, has the largest installed base of all general-purpose operating systems, as of May 2022.[23][24][25] Although Linux is, as of November 2022, used by only around 2.6 percent of desktop computers,[26] the Chromebook, which runs the Linux kernel-based ChromeOS, dominates the US K–12 education market and represents nearly 20 percent of sub-$300 notebook sales in the US.[27] Linux is the leading operating system on servers (over 96.4% of the top 1 million web servers’ operating systems are Linux),[28] leads other big iron systems such as mainframe computers, and is used on all of the world’s 500 fastest supercompters[d] (since November 2017, having gradually displaced all competitors).[29][30][31]

Linux also runs on embedded systems, i.e. devices whose operating system is typically built into the firmware and is highly tailored to the system. This includes routers, automation controls, smart home devices, video game consoles,[32] televisions (Samsung and LG Smart TVs),[33][34][35] automobiles (Tesla, Audi, Mercedes-Benz, Hyundai and Toyota),[36] and spacecraft (Falcon 9 rocket, Dragon crew capsule and the Perseverance rover).[37][38]

Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free and open-source software collaboration. The source code may be used, modified and distributed commercially or non-commercially by anyone under the terms of its respective licenses, such as the GNU General Public License (GPL). The Linux kernel, for example, is licensed under the GPLv2.[e]

History[edit]

Precursors[edit]

The Unix operating system was conceived and implemented in 1969, at AT&T’s Bell Labs, in the United States by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna.[40] First released in 1971, Unix was written entirely in assembly language, as was common practice at the time. In 1973, in a key pioneering approach, it was rewritten in the C programming language by Dennis Ritchie (with the exception of some hardware and I/O routines). The availability of a high-level language implementation of Unix made its porting to different computer platforms easier.[41]

Due to an earlier antitrust case forbidding it from entering the computer business, AT&T licensed the operating system’s source code as a trade secret to anyone who asked. As a result, Unix grew quickly and became widely adopted by academic institutions and businesses. In 1984, AT&T divested itself of its regional operating companies, and was released from its obligation not to enter the computer business; freed of that obligation, Bell Labs began selling Unix as a proprietary product, where users were not legally allowed to modify it.[42][43]

Onyx Systems began selling early microcomputer-based Unix workstations in 1980. Later, Sun Microsystems, founded as a spin-off of a student project at Stanford University, also began selling Unix-based desktop workstations in 1982. While Sun workstations didn’t utilize commodity PC hardware like Linux was later developed for, it represented the first successful commercial attempt at distributing a primarily single-user microcomputer that ran a Unix operating system.[44][45]

With Unix increasingly «locked in» as a proprietary product, the GNU Project, started in 1983 by Richard Stallman, had the goal of creating a «complete Unix-compatible software system» composed entirely of free software. Work began in 1984.[46] Later, in 1985, Stallman started the Free Software Foundation and wrote the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL) in 1989. By the early 1990s, many of the programs required in an operating system (such as libraries, compilers, text editors, a command-line shell, and a windowing system) were completed, although low-level elements such as device drivers, daemons, and the kernel, called GNU Hurd, were stalled and incomplete.[47]

MINIX was created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum, a computer science professor, and released in 1987 as a minimal Unix-like operating system targeted at students and others who wanted to learn operating system principles. Although the complete source code of MINIX was freely available, the licensing terms prevented it from being free software until the licensing changed in April 2000.[48]

Although not released until 1992, due to legal complications, development of 386BSD, from which NetBSD, OpenBSD and FreeBSD descended, predated that of Linux.

Linus Torvalds has stated on separate occasions that if the GNU kernel or 386BSD had been available at the time (1991), he probably would not have created Linux.[49][50]

Creation[edit]

While attending the University of Helsinki in the fall of 1990, Torvalds enrolled in a Unix course.[51] The course utilized a MicroVAX minicomputer running Ultrix, and one of the required texts was Operating Systems: Design and Implementation by Andrew S. Tanenbaum. This textbook included a copy of Tanenbaum’s MINIX operating system. It was with this course that Torvalds first became exposed to Unix. In 1991, he became curious about operating systems.[52] Frustrated by the licensing of MINIX, which at the time limited it to educational use only,[48] he began to work on his own operating system kernel, which eventually became the Linux kernel.

Torvalds began the development of the Linux kernel on MINIX and applications written for MINIX were also used on Linux. Later, Linux matured and further Linux kernel development took place on Linux systems.[53] GNU applications also replaced all MINIX components, because it was advantageous to use the freely available code from the GNU Project with the fledgling operating system; code licensed under the GNU GPL can be reused in other computer programs as long as they also are released under the same or a compatible license. Torvalds initiated a switch from his original license, which prohibited commercial redistribution, to the GNU GPL.[54] Developers worked to integrate GNU components with the Linux kernel, creating a fully functional and free operating system.[55]

Naming[edit]

5.25-inch floppy disks holding a very early version of Linux

Linus Torvalds had wanted to call his invention «Freax«, a portmanteau of «free», «freak», and «x» (as an allusion to Unix). During the start of his work on the system, some of the project’s makefiles included the name «Freax» for about half a year. Initially, Torvalds considered the name «Linux» but dismissed it as too egotistical.[56]

To facilitate development, the files were uploaded to the FTP server (ftp.funet.fi) of FUNET in September 1991. Ari Lemmke, Torvalds’ coworker at the Helsinki University of Technology (HUT) who was one of the volunteer administrators for the FTP server at the time, did not think that «Freax» was a good name, so he named the project «Linux» on the server without consulting Torvalds.[56] Later, however, Torvalds consented to «Linux».

According to a newsgroup post by Torvalds,[11] the word «Linux» should be pronounced ( LIN-uuks) with a short ‘i’ as in ‘print’ and ‘u’ as in ‘put’. To further demonstrate how the word «Linux» should be pronounced, he included an audio guide (listen (help·info)) with the kernel source code.[57] However, in this recording, he pronounces ‘Linux’ ( LEEN-uuks) with a short but close front unrounded vowel.

Commercial and popular uptake[edit]

Ubuntu, a popular Linux distribution

Adoption of Linux in production environments, rather than being used only by hobbyists, started to take off first in the mid-1990s in the supercomputing community, where organizations such as NASA started to replace their increasingly expensive machines with clusters of inexpensive commodity computers running Linux. Commercial use began when Dell and IBM, followed by Hewlett-Packard, started offering Linux support to escape Microsoft’s monopoly in the desktop operating system market.[58]

Today, Linux systems are used throughout computing, from embedded systems to virtually all supercomputers,[31][59] and have secured a place in server installations such as the popular LAMP application stack. Use of Linux distributions in home and enterprise desktops has been growing.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66] Linux distributions have also become popular in the netbook market, with many devices shipping with customized Linux distributions installed, and Google releasing their own ChromeOS designed for netbooks.

Linux’s greatest success in the consumer market is perhaps the mobile device market, with Android being the dominant operating system on smartphones and very popular on tablets and, more recently, on wearables. Linux gaming is also on the rise with Valve showing its support for Linux and rolling out SteamOS, its own gaming-oriented Linux distribution, and later the Steam Deck platform. Linux distributions have also gained popularity with various local and national governments, such as the federal government of Brazil.[67]

Current development[edit]

Greg Kroah-Hartman is the lead maintainer for the Linux kernel and guides its development.[68] William John Sullivan is the executive director of the Free Software Foundation,[69] which in turn supports the GNU components.[70] Finally, individuals and corporations develop third-party non-GNU components. These third-party components comprise a vast body of work and may include both kernel modules and user applications and libraries.

Linux vendors and communities combine and distribute the kernel, GNU components, and non-GNU components, with additional package management software in the form of Linux distributions.

Design[edit]

Many open source developers agree that the Linux kernel was not designed but rather evolved through natural selection. Torvalds considers that although the design of Unix served as a scaffolding, «Linux grew with a lot of mutations – and because the mutations were less than random, they were faster and more directed than alpha-particles in DNA.»[71] Eric S. Raymond considers Linux’s revolutionary aspects to be social, not technical: before Linux, complex software was designed carefully by small groups, but «Linux evolved in a completely different way. From nearly the beginning, it was rather casually hacked on by huge numbers of volunteers coordinating only through the Internet. Quality was maintained not by rigid standards or autocracy but by the naively simple strategy of releasing every week and getting feedback from hundreds of users within days, creating a sort of rapid Darwinian selection on the mutations introduced by developers.»[72] Bryan Cantrill, an engineer of a competing OS, agrees that «Linux wasn’t designed, it evolved», but considers this to be a limitation, proposing that some features, especially those related to security,[73] cannot be evolved into, «this is not a biological system at the end of the day, it’s a software system.»[74]

A Linux-based system is a modular Unix-like operating system, deriving much of its basic design from principles established in Unix during the 1970s and 1980s. Such a system uses a monolithic kernel, the Linux kernel, which handles process control, networking, access to the peripherals, and file systems. Device drivers are either integrated directly with the kernel, or added as modules that are loaded while the system is running.[75]

The GNU userland is a key part of most systems based on the Linux kernel, with Android being the notable exception. The Project’s implementation of the C library works as a wrapper for the system calls of the Linux kernel necessary to the kernel-userspace interface, the toolchain is a broad collection of programming tools vital to Linux development (including the compilers used to build the Linux kernel itself), and the coreutils implement many basic Unix tools. The project also develops Bash, a popular CLI shell. The graphical user interface (or GUI) used by most Linux systems is built on top of an implementation of the X Window System.[76] More recently, the Linux community seeks to advance to Wayland as the new display server protocol in place of X11. Many other open-source software projects contribute to Linux systems.

| User mode | User applications | bash, LibreOffice, GIMP, Blender, 0 A.D., Mozilla Firefox, … | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System components | init daemon: OpenRC, runit, systemd… |

System daemons: polkitd, smbd, sshd, udevd… |

Window manager: X11, Wayland, SurfaceFlinger (Android) |

Graphics: Mesa, AMD Catalyst, … |

Other libraries: GTK, Qt, EFL, SDL, SFML, FLTK, GNUstep, … |

| C standard library | fopen, execv, malloc, memcpy, localtime, pthread_create… (up to 2000 subroutines)glibc aims to be fast, musl aims to be lightweight, uClibc targets embedded systems, bionic was written for Android, etc. All aim to be POSIX/SUS-compatible. |

||||

| Kernel mode | Linux kernel | stat, splice, dup, read, open, ioctl, write, mmap, close, exit, etc. (about 380 system calls)The Linux kernel System Call Interface (SCI), aims to be POSIX/SUS-compatible[77] |

|||

| Process scheduling subsystem |

IPC subsystem |

Memory management subsystem |

Virtual files subsystem |

Network subsystem |

|

| Other components: ALSA, DRI, evdev, klibc, LVM, device mapper, Linux Network Scheduler, Netfilter Linux Security Modules: SELinux, TOMOYO, AppArmor, Smack |

|||||

| Hardware (CPU, main memory, data storage devices, etc.) |

Installed components of a Linux system include the following:[76][78]

- A bootloader, for example GNU GRUB, LILO, SYSLINUX or systemd-boot. This is a program that loads the Linux kernel into the computer’s main memory, by being executed by the computer when it is turned on and after the firmware initialization is performed.

- An init program, such as the traditional sysvinit and the newer systemd, OpenRC and Upstart. This is the first process launched by the Linux kernel, and is at the root of the process tree: in other terms, all processes are launched through init. It starts processes such as system services and login prompts (whether graphical or in terminal mode).

- Software libraries, which contain code that can be used by running processes. On Linux systems using ELF-format executable files, the dynamic linker that manages the use of dynamic libraries is known as ld-linux.so. If the system is set up for the user to compile software themselves, header files will also be included to describe the interface of installed libraries. Besides the most commonly used software library on Linux systems, the GNU C Library (glibc), there are numerous other libraries, such as SDL and Mesa.

- C standard library is the library needed to run C programs on a computer system, with the GNU C Library being the standard. For embedded systems, alternatives such as the musl, EGLIBC (a glibc fork once used by Debian) and uClibc (which was designed for uClinux) have been developed, although the last two are no longer maintained. Android uses its own C library, Bionic.

- Basic Unix commands, with GNU coreutils being the standard implementation. Alternatives exist for embedded systems, such as the copyleft BusyBox, and the BSD-licensed Toybox.

- Widget toolkits are the libraries used to build graphical user interfaces (GUIs) for software applications. Numerous widget toolkits are available, including GTK and Clutter developed by the GNOME project, Qt developed by the Qt Project and led by The Qt Company, and Enlightenment Foundation Libraries (EFL) developed primarily by the Enlightenment team.

- A package management system, such as dpkg and RPM. Alternatively packages can be compiled from binary or source tarballs.

- User interface programs such as command shells or windowing environments.

User interface[edit]

The user interface, also known as the shell, is either a command-line interface (CLI), a graphical user interface (GUI), or controls attached to the associated hardware, which is common for embedded systems. For desktop systems, the default user interface is usually graphical, although the CLI is commonly available through terminal emulator windows or on a separate virtual console.

CLI shells are text-based user interfaces, which use text for both input and output. The dominant shell used in Linux is the Bourne-Again Shell (bash), originally developed for the GNU project. Most low-level Linux components, including various parts of the userland, use the CLI exclusively. The CLI is particularly suited for automation of repetitive or delayed tasks and provides very simple inter-process communication.

On desktop systems, the most popular user interfaces are the GUI shells, packaged together with extensive desktop environments, such as KDE Plasma, GNOME, MATE, Cinnamon, LXDE, Pantheon and Xfce, though a variety of additional user interfaces exist. Most popular user interfaces are based on the X Window System, often simply called «X». It provides network transparency and permits a graphical application running on one system to be displayed on another where a user may interact with the application; however, certain extensions of the X Window System are not capable of working over the network.[79] Several X display servers exist, with the reference implementation, X.Org Server, being the most popular.

Server distributions might provide a command-line interface for developers and administrators, but provide a custom interface towards end-users, designed for the use-case of the system. This custom interface is accessed through a client that resides on another system, not necessarily Linux based.

Several types of window managers exist for X11, including tiling, dynamic, stacking and compositing. Window managers provide means to control the placement and appearance of individual application windows, and interact with the X Window System. Simpler X window managers such as dwm, ratpoison, i3wm, or herbstluftwm provide a minimalist functionality, while more elaborate window managers such as FVWM, Enlightenment or Window Maker provide more features such as a built-in taskbar and themes, but are still lightweight when compared to desktop environments. Desktop environments include window managers as part of their standard installations, such as Mutter (GNOME), KWin (KDE) or Xfwm (xfce), although users may choose to use a different window manager if preferred.

Wayland is a display server protocol intended as a replacement for the X11 protocol; as of 2022, it has received relatively wide adoption.[80] Unlike X11, Wayland does not need an external window manager and compositing manager. Therefore, a Wayland compositor takes the role of the display server, window manager and compositing manager. Weston is the reference implementation of Wayland, while GNOME’s Mutter and KDE’s KWin are being ported to Wayland as standalone display servers. Enlightenment has already been successfully ported since version 19.[81]

Video input infrastructure[edit]

Linux currently has two modern kernel-userspace APIs for handling video input devices: V4L2 API for video streams and radio, and DVB API for digital TV reception.[82]

Due to the complexity and diversity of different devices, and due to the large number of formats and standards handled by those APIs, this infrastructure needs to evolve to better fit other devices. Also, a good userspace device library is the key of the success for having userspace applications to be able to work with all formats supported by those devices.[83][84]

Development[edit]

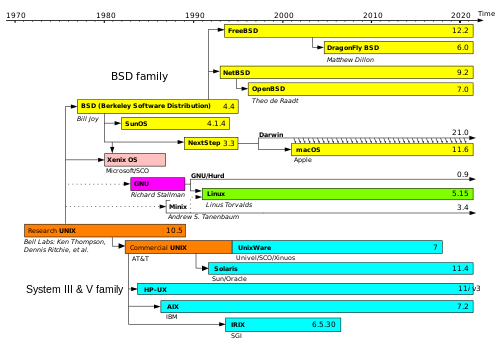

Simplified history of Unix-like operating systems. Linux shares similar architecture and concepts (as part of the POSIX standard) but does not share non-free source code with the original Unix or MINIX.

The primary difference between Linux and many other popular contemporary operating systems is that the Linux kernel and other components are free and open-source software. Linux is not the only such operating system, although it is by far the most widely used.[85] Some free and open-source software licenses are based on the principle of copyleft, a kind of reciprocity: any work derived from a copyleft piece of software must also be copyleft itself. The most common free software license, the GNU General Public License (GPL), is a form of copyleft, and is used for the Linux kernel and many of the components from the GNU Project.[86]

Linux-based distributions are intended by developers for interoperability with other operating systems and established computing standards. Linux systems adhere to POSIX,[87] SUS,[88] LSB, ISO, and ANSI standards where possible, although to date only one Linux distribution has been POSIX.1 certified, Linux-FT.[89][90]

Free software projects, although developed through collaboration, are often produced independently of each other. The fact that the software licenses explicitly permit redistribution, however, provides a basis for larger-scale projects that collect the software produced by stand-alone projects and make it available all at once in the form of a Linux distribution.

Many Linux distributions manage a remote collection of system software and application software packages available for download and installation through a network connection. This allows users to adapt the operating system to their specific needs. Distributions are maintained by individuals, loose-knit teams, volunteer organizations, and commercial entities. A distribution is responsible for the default configuration of the installed Linux kernel, general system security, and more generally integration of the different software packages into a coherent whole. Distributions typically use a package manager such as apt, yum, zypper, pacman or portage to install, remove, and update all of a system’s software from one central location.[91]

[edit]

A distribution is largely driven by its developer and user communities. Some vendors develop and fund their distributions on a volunteer basis, Debian being a well-known example. Others maintain a community version of their commercial distributions, as Red Hat does with Fedora, and SUSE does with openSUSE.[92][93]

In many cities and regions, local associations known as Linux User Groups (LUGs) seek to promote their preferred distribution and by extension free software. They hold meetings and provide free demonstrations, training, technical support, and operating system installation to new users. Many Internet communities also provide support to Linux users and developers. Most distributions and free software / open-source projects have IRC chatrooms or newsgroups. Online forums are another means for support, with notable examples being LinuxQuestions.org and the various distribution specific support and community forums, such as ones for Ubuntu, Fedora, and Gentoo. Linux distributions host mailing lists; commonly there will be a specific topic such as usage or development for a given list.

There are several technology websites with a Linux focus. Print magazines on Linux often bundle cover disks that carry software or even complete Linux distributions.[94][95]

Although Linux distributions are generally available without charge, several large corporations sell, support, and contribute to the development of the components of the system and of free software. An analysis of the Linux kernel in 2017 showed that well over 85% of the code developed by programmers who are being paid for their work, leaving about 8.2% to unpaid developers and 4.1% unclassified.[96] Some of the major corporations that provide contributions include Intel, Samsung, Google, AMD, Oracle and Facebook.[97] A number of corporations, notably Red Hat, Canonical and SUSE, have built a significant business around Linux distributions.

The free software licenses, on which the various software packages of a distribution built on the Linux kernel are based, explicitly accommodate and encourage commercialization; the relationship between a Linux distribution as a whole and individual vendors may be seen as symbiotic. One common business model of commercial suppliers is charging for support, especially for business users. A number of companies also offer a specialized business version of their distribution, which adds proprietary support packages and tools to administer higher numbers of installations or to simplify administrative tasks.

Another business model is to give away the software to sell hardware. This used to be the norm in the computer industry, with operating systems such as CP/M, Apple DOS and versions of Mac OS prior to 7.6 freely copyable (but not modifiable). As computer hardware standardized throughout the 1980s, it became more difficult for hardware manufacturers to profit from this tactic, as the OS would run on any manufacturer’s computer that shared the same architecture.

Programming on Linux[edit]

Most programming languages support Linux either directly or through third-party community based ports.[98] The original development tools used for building both Linux applications and operating system programs are found within the GNU toolchain, which includes the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) and the GNU Build System. Amongst others, GCC provides compilers for Ada, C, C++, Go and Fortran. Many programming languages have a cross-platform reference implementation that supports Linux, for example PHP, Perl, Ruby, Python, Java, Go, Rust and Haskell. First released in 2003, the LLVM project provides an alternative cross-platform open-source compiler for many languages. Proprietary compilers for Linux include the Intel C++ Compiler, Sun Studio, and IBM XL C/C++ Compiler. BASIC in the form of Visual Basic is supported in such forms as Gambas, FreeBASIC, and XBasic, and in terms of terminal programming or QuickBASIC or Turbo BASIC programming in the form of QB64.

A common feature of Unix-like systems, Linux includes traditional specific-purpose programming languages targeted at scripting, text processing and system configuration and management in general. Linux distributions support shell scripts, awk, sed and make. Many programs also have an embedded programming language to support configuring or programming themselves. For example, regular expressions are supported in programs like grep and locate, the traditional Unix MTA Sendmail contains its own Turing complete scripting system, and the advanced text editor GNU Emacs is built around a general purpose Lisp interpreter.

Most distributions also include support for PHP, Perl, Ruby, Python and other dynamic languages. While not as common, Linux also supports C# (via Mono), Vala, and Scheme. Guile Scheme acts as an extension language targeting the GNU system utilities, seeking to make the conventionally small, static, compiled C programs of Unix design rapidly and dynamically extensible via an elegant, functional high-level scripting system; many GNU programs can be compiled with optional Guile bindings to this end. A number of Java virtual machines and development kits run on Linux, including the original Sun Microsystems JVM (HotSpot), and IBM’s J2SE RE, as well as many open-source projects like Kaffe and JikesRVM.

GNOME and KDE are popular desktop environments and provide a framework for developing applications. These projects are based on the GTK and Qt widget toolkits, respectively, which can also be used independently of the larger framework. Both support a wide variety of languages. There are a number of Integrated development environments available including Anjuta, Code::Blocks, CodeLite, Eclipse, Geany, ActiveState Komodo, KDevelop, Lazarus, MonoDevelop, NetBeans, and Qt Creator, while the long-established editors Vim, nano and Emacs remain popular.[99]

Hardware support[edit]

Linux is ubiquitously found on various types of hardware.

The Linux kernel is a widely ported operating system kernel, available for devices ranging from mobile phones to supercomputers; it runs on a highly diverse range of computer architectures, including the hand-held ARM-based iPAQ and the IBM mainframes System z9 or System z10.[100] Specialized distributions and kernel forks exist for less mainstream architectures; for example, the ELKS kernel fork can run on Intel 8086 or Intel 80286 16-bit microprocessors, while the µClinux kernel fork may run on systems without a memory management unit. The kernel also runs on architectures that were only ever intended to use a manufacturer-created operating system, such as Macintosh computers[101][102] (with both PowerPC and Intel processors), PDAs, video game consoles, portable music players, and mobile phones.

Linux has a reputation of supporting old hardware very well by maintaining standardized drivers for a long time.[103] There are several industry associations and hardware conferences devoted to maintaining and improving support for diverse hardware under Linux, such as FreedomHEC. Over time, support for different hardware has improved in Linux, resulting in any off-the-shelf purchase having a «good chance» of being compatible.[104]

In 2014, a new initiative was launched to automatically collect a database of all tested hardware configurations.[105]

Uses[edit]

[edit]

Many quantitative studies of free/open-source software focus on topics including market share and reliability, with numerous studies specifically examining Linux.[106] The Linux market is growing, and the Linux operating system market size is expected to see a growth of 19.2% by 2027, reaching $15.64 billion, compared to $3.89 billion in 2019.[107] Analysts and proponents attribute the relative success of Linux to its security, reliability, low cost, and freedom from vendor lock-in.[108][109]

- Desktops and laptops

- According to web server statistics (that is, based on the numbers recorded from visits to websites by client devices), as of May 2022, the estimated market share of Linux on desktop computers is around 2.5%. In comparison, Microsoft Windows has a market share of around 75.5%, while macOS covers around 14.9%.[26]

- Web servers

- W3Cook publishes stats that use the top 1,000,000 Alexa domains,[110] which as of May 2015 estimate that 96.55% of web servers run Linux, 1.73% run Windows, and 1.72% run FreeBSD.[111]

- W3Techs publishes stats that use the top 10,000,000 Alexa domains and the top 1,000,000 Tranco domains, updated monthly[112] and as of November 2020 estimate that Linux is used by 39% of the web servers, versus 21.9% being used by Microsoft Windows.[113] 40.1% used other types of Unix.[114]

- IDC’s Q1 2007 report indicated that Linux held 12.7% of the overall server market at that time;[115] this estimate was based on the number of Linux servers sold by various companies, and did not include server hardware purchased separately that had Linux installed on it later.

- Mobile devices

- Android, which is based on the Linux kernel, has become the dominant operating system for smartphones. In July 2022, 71.9% of smartphones accessing the internet worldwide used Android.[116] Android is also a popular operating system for tablets, being responsible for more than 60% of tablet sales as of 2013.[117] According to web server statistics, as of October 2021 Android has a market share of about 71%, with iOS holding 28%, and the remaining 1% attributed to various niche platforms.[118]

- Film production

- For years Linux has been the platform of choice in the film industry. The first major film produced on Linux servers was 1997’s Titanic.[119][120] Since then major studios including DreamWorks Animation, Pixar, Weta Digital, and Industrial Light & Magic have migrated to Linux.[121][122][123] According to the Linux Movies Group, more than 95% of the servers and desktops at large animation and visual effects companies use Linux.[124]

- Use in government

- Linux distributions have also gained popularity with various local and national governments. News of the Russian military creating its own Linux distribution has also surfaced, and has come to fruition as the G.H.ost Project.[125] The Indian state of Kerala has gone to the extent of mandating that all state high schools run Linux on their computers.[126][127] China uses Linux exclusively as the operating system for its Loongson processor family to achieve technology independence.[128] In Spain, some regions have developed their own Linux distributions, which are widely used in education and official institutions, like gnuLinEx in Extremadura and Guadalinex in Andalusia. France and Germany have also taken steps toward the adoption of Linux.[129] North Korea’s Red Star OS, developed since 2002, is based on a version of Fedora Linux.[130]

Copyright, trademark, and naming[edit]

Linux kernel is licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL), version 2. The GPL requires that anyone who distributes software based on source code under this license must make the originating source code (and any modifications) available to the recipient under the same terms.[131] Other key components of a typical Linux distribution are also mainly licensed under the GPL, but they may use other licenses; many libraries use the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), a more permissive variant of the GPL, and the X.Org implementation of the X Window System uses the MIT License.

Torvalds states that the Linux kernel will not move from version 2 of the GPL to version 3.[132][133] He specifically dislikes some provisions in the new license which prohibit the use of the software in digital rights management.[134] It would also be impractical to obtain permission from all the copyright holders, who number in the thousands.[135]

A 2001 study of Red Hat Linux 7.1 found that this distribution contained 30 million source lines of code.[136] Using the Constructive Cost Model, the study estimated that this distribution required about eight thousand person-years of development time. According to the study, if all this software had been developed by conventional proprietary means, it would have cost about US$1.64 billion[137] to develop in 2021 in the United States.[136] Most of the source code (71%) was written in the C programming language, but many other languages were used, including C++, Lisp, assembly language, Perl, Python, Fortran, and various shell scripting languages. Slightly over half of all lines of code were licensed under the GPL. The Linux kernel itself was 2.4 million lines of code, or 8% of the total.[136]

In a later study, the same analysis was performed for Debian version 4.0 (etch, which was released in 2007).[138] This distribution contained close to 283 million source lines of code, and the study estimated that it would have required about seventy three thousand man-years and cost US$9.16 billion[137] (in 2021 dollars) to develop by conventional means.

The name «Linux» is also used for a laundry detergent made by Swiss company Rösch.[139]

In the United States, the name Linux is a trademark registered to Linus Torvalds.[10] Initially, nobody registered it, but on August 15, 1994, William R. Della Croce, Jr. filed for the trademark Linux, and then demanded royalties from Linux distributors. In 1996, Torvalds and some affected organizations sued him to have the trademark assigned to Torvalds, and, in 1997, the case was settled.[140] The licensing of the trademark has since been handled by the Linux Mark Institute (LMI). Torvalds has stated that he trademarked the name only to prevent someone else from using it. LMI originally charged a nominal sublicensing fee for use of the Linux name as part of trademarks,[141] but later changed this in favor of offering a free, perpetual worldwide sublicense.[142]

The Free Software Foundation (FSF) prefers GNU/Linux as the name when referring to the operating system as a whole, because it considers Linux distributions to be variants of the GNU operating system initiated in 1983 by Richard Stallman, president of the FSF.[16][17] They explicitly take no issue over the name Android for the Android OS, which is also an operating system based on the Linux kernel, as GNU is not a part of it.

A minority of public figures and software projects other than Stallman and the FSF, notably Debian (which had been sponsored by the FSF up to 1996),[143] also use GNU/Linux when referring to the operating system as a whole.[144][145][146] Most media and common usage, however, refers to this family of operating systems simply as Linux, as do many large Linux distributions (for example, SUSE Linux and Red Hat Enterprise Linux). By contrast, Linux distributions containing only free software use «GNU/Linux» or simply «GNU», such as Trisquel GNU/Linux, Parabola GNU/Linux-libre, BLAG Linux and GNU, and gNewSense.

As of May 2011, about 8% to 13% of the lines of code of the Linux distribution Ubuntu (version «Natty») is made of GNU components (the range depending on whether GNOME is considered part of GNU); meanwhile, 6% is taken by the Linux kernel, increased to 9% when including its direct dependencies.[147]

See also[edit]

- Comparison of Linux distributions

- Comparison of open source and closed source

- Comparison of operating systems

- Comparison of X Window System desktop environments

- Criticism of Linux

- Linux Documentation Project

- Linux From Scratch

- Linux Software Map

- List of Linux distributions

- List of games released on Linux

- List of operating systems

- Loadable kernel module

- Usage share of operating systems

- Timeline of operating systems

Notes[edit]

- ^ GNU is the primary userland used in nearly all Linux distributions.[2][3][4] The GNU userland contains system daemons, user applications, the GUI, and various libraries. GNU Core utilities are an essential part of most distributions. Most Linux distributions use the X Window system.[5] Other components of the userland, such as the widget toolkit, vary with the specific distribution, desktop environment, and user configuration.[6]

- ^ BusyBox is an alternative userland used in many embedded Linux distributions. BusyBox replaces most GNU Core utilities.[7] One notable Desktop distribution using BusyBox is Alpine Linux[8]

- ^ The name «Linux» itself is a trademark owned by Linus Torvalds.[10] and administered by the Linux Mark Institute.

- ^ As measured by the TOP500 list, which uses HPL to measure computational power.

- ^ The license excepts system calls, as any program calling on the kernel is considered a derivative work; without this exception the GPL would apply to such programs.[39][21]

References[edit]

- ^ Linux Online (2008). «Linux Logos and Mascots». Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- ^ «GNU Userland». Archived from the original on March 8, 2016.

- ^ «Unix Fundamentals — System Administration for Cyborgs». Archived from the original on October 5, 2016.

- ^ «Operating Systems — Introduction to Information and Communication Technology». Archived from the original on February 21, 2016.

- ^ «The X Window System». Archived from the original on January 20, 2016.

- ^ «PCLinuxOS Magazine — HTML». Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Busybox about page». busybox.net.

- ^ «The Alpine Linux about page». alpinelinux.org.

- ^ «The Linux Kernel Archives: Frequently asked questions». kernel.org. September 2, 2014. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b «U.S. Reg No: 1916230». United States Patent and Trademark Office. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2006.

- ^ a b «Re: How to pronounce Linux?». Newsgroup: comp.os.linux. April 23, 1992. Usenet: 1992Apr23.123216.22024@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Eckert, Jason W. (2012). Linux+ Guide to Linux Certification (Third ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning. p. 33. ISBN 978-1111541538. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

The shared commonality of the kernel is what defines a system’s membership in the Linux family; the differing OSS applications that can interact with the common kernel are what differentiate Linux distributions.

- ^ «Twenty Years of Linux according to Linus Torvalds». ZDNet. April 13, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Linus Benedict Torvalds (October 5, 1991). «Free minix-like kernel sources for 386-AT». Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ «What Is Linux: An Overview of the Linux Operating System». Medium. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ a b «GNU/Linux FAQ». Gnu.org. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ a b «Linux and the GNU System». Gnu.org. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ DistroWatch. «DistroWatch.com: Put the fun back into computing. Use Linux, BSD». distrowatch.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ himanshu, Swapnil. «Best Linux distros of 2016: Something for everyone». CIO. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ «10 Top Most Popular Linux Distributions of 2016». www.tecmint.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ a b «What is Linux?». Opensource.com. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Barry Levine (August 26, 2013). «Linux’ 22th [sic] Birthday Is Commemorated — Subtly — by Creator». Simpler Media Group, Inc. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

Originally developed for Intel x86-based PCs, Torvalds’ «hobby» has now been released for more hardware platforms than any other OS in history.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ McPherson, Amanda (December 13, 2012). «What a Year for Linux: Please Join us in Celebration». Linux Foundation. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Linux Devices (November 28, 2006). «Trolltech rolls «complete» Linux smartphone stack». Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ a b «Desktop Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols. «Chromebook shipments leap by 67 percent». ZDNet. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ «OS Market Share and Usage Trends». W3Cook.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2015.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (2017). «Linux totally dominates supercomputers». ZDNet (published November 14, 2017). Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Thibodeau, Patrick (2009). «IBM’s newest mainframe is all Linux». Computerworld (published December 9, 2009). Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ^ a b Lyons, Daniel (March 15, 2005). «Linux rules supercomputers». Forbes. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ IBM (October 2001). «Linux Watch (WatchPad)». Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Eric Brown (March 29, 2019). «Linux continues advance in smart TV market». linuxgizmos.com. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ «Sony Open Source Code Distribution Service». Sony Electronics. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ «Sharp Liquid Crystal Television Instruction Manual» (PDF). Sharp Electronics. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols (January 4, 2019). «It’s a Linux-powered car world». ZDNet. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ «From Earth to orbit with Linux and SpaceX | ZDNet». www.zdnet.com.

- ^ «Linux on Mars!». IT PRO. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ «Linux kernel licensing rules». Linux kernel documentation.

- ^ Ritchie, D.M. (October 1984), «The UNIX System: The Evolution of the UNIX Time-sharing System», AT&T Bell Laboratories Technical Journal, 63 (8): 1577, doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1984.tb00054.x,

However, UNIX was born in 1969 …

- ^ Meeker, Heather (September 21, 2017). «Open source licensing: What every technologist should know». Opensource.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ Michael Vetter (August 10, 2021). Acquisitions and Open Source Software Development. Springer Nature. p. 13. ISBN 978-3-658-35084-0. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Christopher Tozzi (August 11, 2017). For Fun and Profit: A History of the Free and Open Source Software Revolution. MIT Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-262-03647-4. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Eric, S. Raymond (October 1999). The Cathedral and the Bazaar. Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly & Associates, Inc. p. 12. ISBN 0-596-00108-8. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

In 1982, a group of Unix hackers from Stanford and Berkeley founded Sun Microsystems on the belief that Unix running on relatively inexpensive 68000-based hardware would prove a winning combination for a wide variety of applications. They were right, and their vision set the pattern for an entire industry. While still priced out of reach of most individuals, workstations were cheap for corporations and universities; networks of them (one to a user) rapidly replaced the older VAXes and other time-sharing systems

- ^ Lazzareschi, Carla (January 31, 1988). «Sun Microsystems Is Blazing a Red-Hot Trail in Computers: $300-Million AT&T; Deal Moves Firm to Set Sights on IBM». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ «About the GNU Project – Initial Announcement». Gnu.org. June 23, 2008. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ Christopher Tozzi (August 23, 2016). «Open Source History: Why Did Linux Succeed?». Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ a b «MINIX is now available under the BSD license». minix1.woodhull.com. April 9, 2000. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ «Linus vs. Tanenbaum debate». Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Linksvayer, Mike (1993). «The Choice of a GNU Generation – An Interview With Linus Torvalds». Meta magazine. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ Moody, Glyn (August 1, 1997). «The Greatest OS That (N)ever Was». Wired. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. «What would you like to see most in minix?». Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 1991Aug25.205708.9541@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (October 14, 1992). «Chicken and egg: How was the first linux gcc binary created??». Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 1992Oct12.100843.26287@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (January 5, 1992). «Release notes for Linux v0.12». Linux Kernel Archives. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

The Linux copyright will change: I’ve had a couple of requests to make it compatible with the GNU copyleft, removing the «you may not distribute it for money» condition. I agree. I propose that the copyright be changed so that it confirms to GNU ─ pending approval of the persons who have helped write code. I assume this is going to be no problem for anybody: If you have grievances («I wrote that code assuming the copyright would stay the same») mail me. Otherwise, The GNU copyleft takes effect since the first of February. If you do not know the gist of the GNU copyright ─ read it.

- ^ «Overview of the GNU System». Gnu.org. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Torvalds, Linus and Diamond, David, Just for Fun: The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary, 2001, ISBN 0-06-662072-4

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (March 1994). «Index of /pub/linux/kernel/SillySounds». Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ Garfinkel, Simson; Spafford, Gene; Schwartz, Alan (2003). Practical UNIX and Internet Security. O’Reilly. p. 21.

- ^ Santhanam, Anand; Vishal Kulkarni (March 1, 2002). «Linux system development on an embedded device». DeveloperWorks. IBM. Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ Galli, Peter (August 8, 2007). «Vista Aiding Linux Desktop, Strategist Says». eWEEK. Ziff Davis Enterprise Inc. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ Paul, Ryan (September 3, 2007). «Linux market share set to surpass Win 98, OS X still ahead of Vista». Ars Technica. Ars Technica, LLC. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ Beer, Stan (January 23, 2007). «Vista to play second fiddle to XP until 2009: Gartner». iTWire. iTWire. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ «Operating System Marketshare for Year 2007». Market Share. Net Applications. November 19, 2007. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ «Vista slowly continues its growth; Linux more aggressive than Mac OS during the summer». XiTiMonitor. AT Internet/XiTi.com. September 24, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ «Global Web Stats». W3Counter. Awio Web Services LLC. November 10, 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ «June 2004 Zeitgeist». Google Press Center. Google Inc. August 12, 2004. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ McMillan, Robert (October 10, 2003). «IBM, Brazilian government launch Linux effort». www.infoworld.com. IDG News Service. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ «About Us — The Linux Foundation». Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ «The Free Software Foundation Management». Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ «Free software is a matter of liberty, not price — Free Software Foundation — working together for free software». Fsf.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Email correspondence on the Linux Kernel development mailing list Linus Torvalds (November 30, 2001). «Re: Coding style, a non-issue». kernel.org.

- ^ Raymond, Eric S. (2001). O’Reilly, Tim (ed.). The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary (Second ed.). O’Reilly & Associates. p. 16. ISBN 0-596-00108-8.

- ^ «You have to design it you cannot asymptotically reach Security.» Cantrill 2017

- ^ The Cantrill Strikes Back | BSD Now 117. Jupiter Broadcasting. November 26, 2015. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ «Why is Linux called a monolithic kernel?». stackoverflow.com. 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ a b «Anatomy of a Linux System» (PDF). O’Reilly. July 23–26, 2001. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ «Admin Guide README». git.kernel.org.

- ^ M. Tim Jones (May 31, 2006). «Inside the Linux boot process». IBM Developer Works. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ Jake Edge (June 8, 2013). «The Wayland Situation: Facts About X vs. Wayland (Phoronix)». LWN.net. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Matthew (May 6, 2022). «Announcing Fedora 36». Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Diener, Derrik (December 6, 2016). «What Is Wayland and What Does It Means for Linux Users». www.maketecheasier.com/. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ «Linux TV: Television with Linux». linuxtv.org. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ Jonathan Corbet (October 11, 2006). «The Video4Linux2 API: an introduction». LWN.net. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ «Part I. Video for Linux Two API Specification». Chapter 7. Changes. linuxtv.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ Operating System Market Share (November 2009). «Operating System Market Share». Archived from the original on January 25, 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ «gnu.org». www.gnu.org. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ «POSIX.1 (FIPS 151-2) Certification». Archived from the original on February 26, 2012.

- ^ «How source code compatible is Debian with other Unix systems?». Debian FAQ. the Debian project. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011.

- ^ Eissfeldt, Heiko (August 1, 1996). «Certifying Linux». Linux Journal. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016.

- ^ «The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ – Compatibility issues». Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^

- ^ «Get Fedora». getfedora.org. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ design, Cynthia Sanchez: front-end and UI, Zvezdana Marjanovic: graphic. «The makers’ choice for sysadmins, developers and desktop users». openSUSE. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Linux Format. «Linux Format DVD contents». Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ linux-magazine.com. «Current Issue». Archived from the original on January 10, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ «State of Linux Kernel Development 2017». Linux Foundation. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ «State of Linux Kernel Development 2017». Linux Foundation. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ «gfortran — the GNU Fortran compiler, part of GCC». GNU GCC. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ Brockmeier, Joe. «A survey of Linux Web development tools». Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ^ Advani, Prakash (February 8, 2004). «If I could re-write Linux». freeos.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Das, Ankush (January 21, 2021). «Finally! Linux Runs Gracefully On Apple M1 Chip». It’s FOSS News. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ Jimenez, Jorge (October 8, 2021). «Developers finally get Linux running on an Apple M1-powered Mac». PC Gamer. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ Proven, Liam (November 10, 2022). «OpenPrinting keeps old printers working, even on Windows». The Register. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Bruce Byfield (August 14, 2007). «Is my hardware Linux-compatible? Find out here». Linux.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ «Linux Hardware». Linux Hardware Project. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Wheeler, David A. «Why Open Source Software/Free Software (OSS/FS)? Look at the Numbers!». Archived from the original on April 5, 2006. Retrieved April 1, 2006.

- ^ «Linux Operating System Market Size, Share and Forecast [2020-2027]». www.fortunebusinessinsights.com. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ «The rise and rise of Linux». Computer Associates International. October 10, 2005. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007.

- ^ Jeffrey S. Smith. «Why customers are flocking to Linux». IBM. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008.

- ^ «W3Cook FAQ». W3Cook.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ «OS Market Share and Usage Trends». W3Cook.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ «Technologies Overview — methodology information». W3Techs.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ «Linux vs. Windows usage statistics, November 2021». w3techs.com. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ «Usage Statistics and Market Share of Unix for Websites, November 2021». w3techs.com. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ «─ IDC Q1 2007 report». Linux-watch.com. May 29, 2007. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ «Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Egham (March 3, 2014). «Gartner Says Worldwide Tablet Sales Grew 68 Percent in 2013, With Android Capturing 62 Percent of the Market». Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ «Mobile/Tablet Operating System Market Share». Netmarketshare.com. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Daryll. «Linux Helps Bring Titanic to Life». Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ Rowe, Robin. «Linux and Star Trek». Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ «Industry of Change: Linux Storms Hollywood». Archived from the original on April 11, 2009. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ^ «Tux with Shades, Linux in Hollywood». Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ^ «Weta Digital – Jobs». Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ «LinuxMovies.org – Advancing Linux Motion Picture Technology». Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ «LV: Minister: «Open standards improve efficiency and transparency»«. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ «Linux Spreads its Wings in India». Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ «Kerala shuts windows, schools to use only Linux». March 4, 2008. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- ^ «China’s Microprocessor Dilemma». Microprocessor Report. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ Krane, Jim (November 30, 2001). «Some countries are choosing Linux systems over Microsoft». Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ «North Korea’s ‘paranoid’ computer operating system revealed». The Guardian. December 27, 2015. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ «GNU General Public License, version 2». GNU Project. June 2, 1991. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (January 26, 2006). «Re: GPL V3 and Linux ─ Dead Copyright Holders». Linux Kernel Mailing List. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (September 25, 2006). «Re: GPLv3 Position Statement». Linux Kernel Mailing List. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014.

- ^ Brett Smith (July 29, 2013). «Neutralizing Laws That Prohibit Free Software — But Not Forbidding DRM». A Quick Guide to GPLv3. GNU Project. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ «Keeping an Eye on the Penguin». Linux-watch.com. February 7, 2006. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Wheeler, David A (July 29, 2002). «More Than a Gigabuck: Estimating GNU/Linux’s Size». Archived from the original on April 21, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2006.

- ^ a b Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). «What Was the U.S. GDP Then?». MeasuringWorth. Retrieved January 1, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ^ Amor, Juan José; et al. (June 17, 2007). «Measuring Etch: the size of Debian 4.0». Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- ^ «There Is a Linux Detergent Out There and It’s Trademarked». Linux.com. June 19, 2015. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ «Linux Timeline». Linux Journal. May 31, 2006. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013.

- ^ Neil McAllister (September 5, 2005). «Linus gets tough on Linux trademark». InfoWorld. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ «Linux Mark Institute». Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

LMI has restructured its sublicensing program. Our new sublicense agreement is: Free – approved sublicense holders pay no fees; Perpetual – sublicense terminates only in breach of the agreement or when your organization ceases to use its mark; Worldwide – one sublicense covers your use of the mark anywhere in the world

- ^ Richard Stallman (April 28, 1996). «The FSF is no longer sponsoring Debian». tech-insider.org. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ «TiVo ─ GNU/Linux Source Code». Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- ^ «About Debian». debian.org. December 8, 2013. Archived from the original on January 23, 2014. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Andrew D. Balsa; et al. (October 17, 2009). «The linux-kernel mailing list FAQ». vger.kernel.org. Archived from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

…we have tried to use the word «Linux» or the expression «Linux kernel» to designate the kernel, and GNU/Linux to designate the entire body of GNU/GPL’ed OS software,… …many people forget that the linux kernel mailing list is a forum for discussion of kernel-related matters, not GNU/Linux in general…

- ^ Côrte-Real, Pedro (May 31, 2011). «How much GNU is there in GNU/Linux?». Split Perspective. Archived from the original on February 7, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014. (self-published data)

External links[edit]

- Linux at Curlie

- Graphical map of Linux Internals

- Linux kernel website and archives

- The History of Linux in GIT Repository Format 1992–2010

Tux the penguin, the mascot of Linux[1] |

|

| Developer | Community contributors, Linus Torvalds |

|---|---|

| Written in | C, assembly languages, and others |

| OS family | Unix-like |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | September 17, 1991; 31 years ago |

| Repository | git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/ |

| Marketing target | Cloud computing, embedded devices, mainframe computers, mobile devices, personal computers, servers, supercomputers |

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Platforms | Alpha, ARC, ARM, C-Sky, Hexagon, IA-64, LoongArch, m68k, Microblaze, MIPS, Nios II, OpenRISC, PA-RISC, PowerPC, RISC-V, s390, SuperH, SPARC, x86, Xtensa |

| Kernel type | Monolithic |

| Userland | GNU[a], BusyBox[b] |

| Default user interface |

|

| License | GPLv2[9][c]) |

| Articles in the series | |

| Linux kernel Linux distribution |

Linux ( LEE-nuuks or LIN-uuks)[11] is a family of open-source Unix-like operating systems based on the Linux kernel,[12] an operating system kernel first released on September 17, 1991, by Linus Torvalds.[13][14][15] Linux is typically packaged as a Linux distribution, which includes the kernel and supporting system software and libraries, many of which are provided by the GNU Project. Many Linux distributions use the word «Linux» in their name, but the Free Software Foundation uses the name «GNU/Linux» to emphasize the importance of GNU software, causing some controversy.[16][17]

Popular Linux distributions[18][19][20] include Debian, Fedora Linux, and Ubuntu, the latter of which itself consists of many different distributions and modifications, including Lubuntu and Xubuntu. Commercial distributions include Red Hat Enterprise Linux and SUSE Linux Enterprise. Desktop Linux distributions include a windowing system such as X11 or Wayland, and a desktop environment such as GNOME or KDE Plasma. Distributions intended for servers may omit graphics altogether, or include a solution stack such as LAMP. Because Linux is freely redistributable, anyone may create a distribution for any purpose.[21]

Linux was originally developed for personal computers based on the Intel x86 architecture, but has since been ported to more platforms than any other operating system.[22] Because of the dominance of the Linux-based Android on smartphones, Linux, including Android, has the largest installed base of all general-purpose operating systems, as of May 2022.[23][24][25] Although Linux is, as of November 2022, used by only around 2.6 percent of desktop computers,[26] the Chromebook, which runs the Linux kernel-based ChromeOS, dominates the US K–12 education market and represents nearly 20 percent of sub-$300 notebook sales in the US.[27] Linux is the leading operating system on servers (over 96.4% of the top 1 million web servers’ operating systems are Linux),[28] leads other big iron systems such as mainframe computers, and is used on all of the world’s 500 fastest supercompters[d] (since November 2017, having gradually displaced all competitors).[29][30][31]

Linux also runs on embedded systems, i.e. devices whose operating system is typically built into the firmware and is highly tailored to the system. This includes routers, automation controls, smart home devices, video game consoles,[32] televisions (Samsung and LG Smart TVs),[33][34][35] automobiles (Tesla, Audi, Mercedes-Benz, Hyundai and Toyota),[36] and spacecraft (Falcon 9 rocket, Dragon crew capsule and the Perseverance rover).[37][38]

Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free and open-source software collaboration. The source code may be used, modified and distributed commercially or non-commercially by anyone under the terms of its respective licenses, such as the GNU General Public License (GPL). The Linux kernel, for example, is licensed under the GPLv2.[e]

History[edit]

Precursors[edit]

The Unix operating system was conceived and implemented in 1969, at AT&T’s Bell Labs, in the United States by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna.[40] First released in 1971, Unix was written entirely in assembly language, as was common practice at the time. In 1973, in a key pioneering approach, it was rewritten in the C programming language by Dennis Ritchie (with the exception of some hardware and I/O routines). The availability of a high-level language implementation of Unix made its porting to different computer platforms easier.[41]

Due to an earlier antitrust case forbidding it from entering the computer business, AT&T licensed the operating system’s source code as a trade secret to anyone who asked. As a result, Unix grew quickly and became widely adopted by academic institutions and businesses. In 1984, AT&T divested itself of its regional operating companies, and was released from its obligation not to enter the computer business; freed of that obligation, Bell Labs began selling Unix as a proprietary product, where users were not legally allowed to modify it.[42][43]

Onyx Systems began selling early microcomputer-based Unix workstations in 1980. Later, Sun Microsystems, founded as a spin-off of a student project at Stanford University, also began selling Unix-based desktop workstations in 1982. While Sun workstations didn’t utilize commodity PC hardware like Linux was later developed for, it represented the first successful commercial attempt at distributing a primarily single-user microcomputer that ran a Unix operating system.[44][45]

With Unix increasingly «locked in» as a proprietary product, the GNU Project, started in 1983 by Richard Stallman, had the goal of creating a «complete Unix-compatible software system» composed entirely of free software. Work began in 1984.[46] Later, in 1985, Stallman started the Free Software Foundation and wrote the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL) in 1989. By the early 1990s, many of the programs required in an operating system (such as libraries, compilers, text editors, a command-line shell, and a windowing system) were completed, although low-level elements such as device drivers, daemons, and the kernel, called GNU Hurd, were stalled and incomplete.[47]

MINIX was created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum, a computer science professor, and released in 1987 as a minimal Unix-like operating system targeted at students and others who wanted to learn operating system principles. Although the complete source code of MINIX was freely available, the licensing terms prevented it from being free software until the licensing changed in April 2000.[48]

Although not released until 1992, due to legal complications, development of 386BSD, from which NetBSD, OpenBSD and FreeBSD descended, predated that of Linux.

Linus Torvalds has stated on separate occasions that if the GNU kernel or 386BSD had been available at the time (1991), he probably would not have created Linux.[49][50]

Creation[edit]

While attending the University of Helsinki in the fall of 1990, Torvalds enrolled in a Unix course.[51] The course utilized a MicroVAX minicomputer running Ultrix, and one of the required texts was Operating Systems: Design and Implementation by Andrew S. Tanenbaum. This textbook included a copy of Tanenbaum’s MINIX operating system. It was with this course that Torvalds first became exposed to Unix. In 1991, he became curious about operating systems.[52] Frustrated by the licensing of MINIX, which at the time limited it to educational use only,[48] he began to work on his own operating system kernel, which eventually became the Linux kernel.

Torvalds began the development of the Linux kernel on MINIX and applications written for MINIX were also used on Linux. Later, Linux matured and further Linux kernel development took place on Linux systems.[53] GNU applications also replaced all MINIX components, because it was advantageous to use the freely available code from the GNU Project with the fledgling operating system; code licensed under the GNU GPL can be reused in other computer programs as long as they also are released under the same or a compatible license. Torvalds initiated a switch from his original license, which prohibited commercial redistribution, to the GNU GPL.[54] Developers worked to integrate GNU components with the Linux kernel, creating a fully functional and free operating system.[55]

Naming[edit]

5.25-inch floppy disks holding a very early version of Linux

Linus Torvalds had wanted to call his invention «Freax«, a portmanteau of «free», «freak», and «x» (as an allusion to Unix). During the start of his work on the system, some of the project’s makefiles included the name «Freax» for about half a year. Initially, Torvalds considered the name «Linux» but dismissed it as too egotistical.[56]

To facilitate development, the files were uploaded to the FTP server (ftp.funet.fi) of FUNET in September 1991. Ari Lemmke, Torvalds’ coworker at the Helsinki University of Technology (HUT) who was one of the volunteer administrators for the FTP server at the time, did not think that «Freax» was a good name, so he named the project «Linux» on the server without consulting Torvalds.[56] Later, however, Torvalds consented to «Linux».

According to a newsgroup post by Torvalds,[11] the word «Linux» should be pronounced ( LIN-uuks) with a short ‘i’ as in ‘print’ and ‘u’ as in ‘put’. To further demonstrate how the word «Linux» should be pronounced, he included an audio guide (listen (help·info)) with the kernel source code.[57] However, in this recording, he pronounces ‘Linux’ ( LEEN-uuks) with a short but close front unrounded vowel.

Commercial and popular uptake[edit]

Ubuntu, a popular Linux distribution

Adoption of Linux in production environments, rather than being used only by hobbyists, started to take off first in the mid-1990s in the supercomputing community, where organizations such as NASA started to replace their increasingly expensive machines with clusters of inexpensive commodity computers running Linux. Commercial use began when Dell and IBM, followed by Hewlett-Packard, started offering Linux support to escape Microsoft’s monopoly in the desktop operating system market.[58]

Today, Linux systems are used throughout computing, from embedded systems to virtually all supercomputers,[31][59] and have secured a place in server installations such as the popular LAMP application stack. Use of Linux distributions in home and enterprise desktops has been growing.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66] Linux distributions have also become popular in the netbook market, with many devices shipping with customized Linux distributions installed, and Google releasing their own ChromeOS designed for netbooks.

Linux’s greatest success in the consumer market is perhaps the mobile device market, with Android being the dominant operating system on smartphones and very popular on tablets and, more recently, on wearables. Linux gaming is also on the rise with Valve showing its support for Linux and rolling out SteamOS, its own gaming-oriented Linux distribution, and later the Steam Deck platform. Linux distributions have also gained popularity with various local and national governments, such as the federal government of Brazil.[67]

Current development[edit]

Greg Kroah-Hartman is the lead maintainer for the Linux kernel and guides its development.[68] William John Sullivan is the executive director of the Free Software Foundation,[69] which in turn supports the GNU components.[70] Finally, individuals and corporations develop third-party non-GNU components. These third-party components comprise a vast body of work and may include both kernel modules and user applications and libraries.

Linux vendors and communities combine and distribute the kernel, GNU components, and non-GNU components, with additional package management software in the form of Linux distributions.

Design[edit]

Many open source developers agree that the Linux kernel was not designed but rather evolved through natural selection. Torvalds considers that although the design of Unix served as a scaffolding, «Linux grew with a lot of mutations – and because the mutations were less than random, they were faster and more directed than alpha-particles in DNA.»[71] Eric S. Raymond considers Linux’s revolutionary aspects to be social, not technical: before Linux, complex software was designed carefully by small groups, but «Linux evolved in a completely different way. From nearly the beginning, it was rather casually hacked on by huge numbers of volunteers coordinating only through the Internet. Quality was maintained not by rigid standards or autocracy but by the naively simple strategy of releasing every week and getting feedback from hundreds of users within days, creating a sort of rapid Darwinian selection on the mutations introduced by developers.»[72] Bryan Cantrill, an engineer of a competing OS, agrees that «Linux wasn’t designed, it evolved», but considers this to be a limitation, proposing that some features, especially those related to security,[73] cannot be evolved into, «this is not a biological system at the end of the day, it’s a software system.»[74]

A Linux-based system is a modular Unix-like operating system, deriving much of its basic design from principles established in Unix during the 1970s and 1980s. Such a system uses a monolithic kernel, the Linux kernel, which handles process control, networking, access to the peripherals, and file systems. Device drivers are either integrated directly with the kernel, or added as modules that are loaded while the system is running.[75]

The GNU userland is a key part of most systems based on the Linux kernel, with Android being the notable exception. The Project’s implementation of the C library works as a wrapper for the system calls of the Linux kernel necessary to the kernel-userspace interface, the toolchain is a broad collection of programming tools vital to Linux development (including the compilers used to build the Linux kernel itself), and the coreutils implement many basic Unix tools. The project also develops Bash, a popular CLI shell. The graphical user interface (or GUI) used by most Linux systems is built on top of an implementation of the X Window System.[76] More recently, the Linux community seeks to advance to Wayland as the new display server protocol in place of X11. Many other open-source software projects contribute to Linux systems.

| User mode | User applications | bash, LibreOffice, GIMP, Blender, 0 A.D., Mozilla Firefox, … | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|