This article is about the philosophical reminder of death’s inevitability. For other uses, see Memento mori (disambiguation).

The outer panels of Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque Triptych (c. 1452) show the skull of the patron displayed on the inner panels. The bones rest on a brick, a symbol of his former industry and achievement.[1]

Memento mori (Latin for ‘remember that you [have to] die’[2]) is an artistic or symbolic trope acting as a reminder of the inevitability of death.[2] The concept has its roots in the philosophers of classical antiquity and Christianity, and appeared in funerary art and architecture from the medieval period onwards.

The most common motif is a skull, often accompanied by one or more bones. Often this alone is enough to evoke the trope, but other motifs such as a coffin, hourglass and wilting flowers signify the impermanence of human life. Often these function within a work whose main subject is something else, such as a portrait, but the vanitas is an artistic genre where the theme of death is the main subject. The Danse Macabre and Death personified with a scythe as the Grim Reaper are even more direct evocations of the trope.

Pronunciation and translation[edit]

In English, the phrase is pronounced , mə-MEN-toh MOR-ee.

Memento is the 2nd person singular active imperative of meminī, ‘to remember, to bear in mind’, usually serving as a warning: «remember!» Morī is the present infinitive of the deponent verb morior ‘to die’.[3]

In other words, «remember death» or «remember that you die».[4]

History of the concept[edit]

In classical antiquity[edit]

The philosopher Democritus trained himself by going into solitude and frequenting tombs.[5] Plato’s Phaedo, where the death of Socrates is recounted, introduces the idea that the proper practice of philosophy is «about nothing else but dying and being dead».[6]

The Stoics of classical antiquity were particularly prominent in their use of this discipline, and Seneca’s letters are full of injunctions to meditate on death.[7] The Stoic Epictetus told his students that when kissing their child, brother, or friend, they should remind themselves that they are mortal, curbing their pleasure, as do «those who stand behind men in their triumphs and remind them that they are mortal».[8] The Stoic Marcus Aurelius invited the reader (himself) to «consider how ephemeral and mean all mortal things are» in his Meditations.[9][10]

In some accounts of the Roman triumph, a companion or public slave would stand behind or near the triumphant general during the procession and remind him from time to time of his own mortality or prompt him to «look behind».[11] A version of this warning is often rendered into English as «Remember, Caesar, thou art mortal», for example in Fahrenheit 451.

In Judaism[edit]

Several passages in the Old Testament urge a remembrance of death. In Psalm 90, Moses prays that God would teach his people «to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom» (Ps. 90:12). In Ecclesiastes, the Preacher insists that «It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting, for this is the end of all mankind, and the living will lay it to heart» (Eccl. 7:2). In Isaiah, the lifespan of human beings is compared to the short lifespan of grass: «The grass withers, the flower fades when the breath of the LORD blows on it; surely the people are grass» (Is. 40:7).

In early Christianity[edit]

The expression memento mori developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation of the soul in the afterlife.[12]

The 2nd-century Christian writer Tertullian claimed that during his triumphal procession, a victorious general would have someone (in later versions, a slave) standing behind him, holding a crown over his head and whispering «Respice post te. Hominem te memento» («Look after you [to the time after your death] and remember you’re [only] a man.»). Though in modern times this has become a standard trope, in fact no other ancient authors confirm this, and it may have been Christian moralizing rather than an accurate historical report.[13]

In Europe from the medieval era to the Victorian era[edit]

Dance of Death (replica of 15th century fresco; National Gallery of Slovenia). No matter one’s station in life, the Dance of Death unites all.

Philosophy[edit]

The thought was then utilized in Christianity, whose strong emphasis on divine judgment, heaven, hell, and the salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness.[14] In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the nunc est bibendum (now is the time to drink) theme of classical antiquity. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one’s thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with the memento mori in this context is In omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis (the Vulgate’s Latin rendering of Ecclesiasticus 7:40, «in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.») This finds ritual expression in the rites of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshipers’ heads with the words, «Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust, you shall return.»

Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.[15]

Architecture[edit]

The most obvious places to look for memento mori meditations are in funeral art and architecture. Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is the transi or cadaver tomb, a tomb that depicts the decayed corpse of the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still offer a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. Later, Puritan tomb stones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles. These are among the numerous themes associated with skull imagery.

Another example of memento mori is provided by the chapels of bones, such as the Capela dos Ossos in Évora or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. These are chapels where the walls are totally or partially covered by human remains, mostly bones. The entrance to the Capela dos Ossos has the following sentence: «We bones, lying here bare, await yours.»

Visual art[edit]

Timepieces have been used to illustrate that the time of the living on Earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Public clocks would be decorated with mottos such as ultima forsan («perhaps the last» [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat («they all wound, and the last kills»). Clocks have carried the motto tempus fugit, «time flees». Old striking clocks often sported automata who would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks from Augsburg, Germany, had Death striking the hour. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality. Mary, Queen of Scots owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace, «Pale death knocks with the same tempo upon the huts of the poor and the towers of Kings.»

In the late 16th and through the 17th century, memento mori jewelry was popular. Items included mourning rings,[16] pendants, lockets, and brooches.[17] These pieces depicted tiny motifs of skulls, bones, and coffins, in addition to messages and names of the departed, picked out in precious metals and enamel.[17][18]

During the same period there emerged the artistic genre known as vanitas, Latin for «emptiness» or «vanity». Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies, and hourglasses. In combination, vanitas assemblies conveyed the impermanence of human endeavours and of the decay that is inevitable with the passage of time. See also the themes associated with the image of the skull.

Literature[edit]

Memento mori is also an important literary theme. Well-known literary meditations on death in English prose include Sir Thomas Browne’s Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and Jeremy Taylor’s Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works were part of a Jacobean cult of melancholia that marked the end of the Elizabethan era. In the late eighteenth century, literary elegies were a common genre; Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Edward Young’s Night Thoughts are typical members of the genre.

In the European devotional literature of the Renaissance, the Ars Moriendi, memento mori had moral value by reminding individuals of their mortality.[19]

Music[edit]

Apart from the genre of requiem and funeral music, there is also a rich tradition of memento mori in the Early Music of Europe. Especially those facing the ever-present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemics from the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-given vale of tears with death as a ransom, and they reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgment Day. The following two Latin stanzas (with their English translations) are typical of memento mori in medieval music; they are from the virelai ad mortem festinamus of the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399:

|

Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur, Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus |

Life is short, and shortly it will end; If you do not turn back and become like a child, |

Danse macabre[edit]

The danse macabre is another well-known example of the memento mori theme, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches.

Gallery[edit]

-

Memento mori ring, with enameled skull and «Die to Live» message (between 1500 and 1650, British Museum, London, England)

-

-

Memento mori in the form of a small coffin, 1700s, wax figure on silk in a wooden coffin (Museum Schnütgen, Cologne, Germany)

The salutation of the Hermits of St. Paul of France[edit]

Memento mori was the salutation used by the Hermits of St. Paul of France (1620–1633), also known as the Brothers of Death.[20] It is sometimes claimed that the Trappists use this salutation, but this is not true.[21]

In Puritan America[edit]

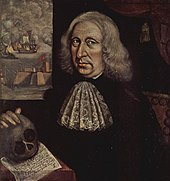

Colonial American art saw a large number of memento mori images due to Puritan influence. The Puritan community in 17th-century North America looked down upon art because they believed that it drew the faithful away from God and, if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records and, as such, they were allowed. Thomas Smith, a 17th-century Puritan, fought in many naval battles and also painted. In his self-portrait, we see these pursuits represented alongside a typical Puritan memento mori with a skull, suggesting his awareness of imminent death.

The poem underneath the skull emphasizes Thomas Smith’s acceptance of death and of turning away from the world of the living:

Why why should I the World be minding, Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

Mexico’s Day of the Dead[edit]

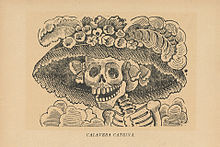

Much memento mori art is associated with the Mexican festival Day of the Dead, including skull-shaped candies and bread loaves adorned with bread «bones».

This theme was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which people from various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

Another manifestation of memento mori is found in the Mexican «Calavera», a literary composition in verse form normally written in honour of a person who is still alive, but written as if that person were dead. These compositions have a comedic tone and are often offered from one friend to another during Day of the Dead.[22]

Contemporary culture[edit]

Roman Krznaric suggests Memento Mori is an important topic to bring back into our thoughts and belief system; «Philosophers have come up with lots of what I call ‘death tasters’ – thought experiments for seizing the day.»

These thought experiments are powerful to get us re-oriented back to death into current awareness and living with spontaneity. Albert Camus stated «Come to terms with death, thereafter anything is possible.» Jean-Paul Sartre expressed that life is given to us early, and is shortened at the end, all the while taken away at every step of the way, emphasizing that the end is only the beginning every day.[23]

Similar concepts in other religions and cultures[edit]

In Buddhism[edit]

The Buddhist practice maraṇasati meditates on death. The word is a Pāli compound of maraṇa ‘death’ (an Indo-European cognate of Latin mori) and sati ‘awareness’, so very close to memento mori. It is first used in early Buddhist texts, the suttapiṭaka of the Pāli Canon, with parallels in the āgamas of the «Northern» Schools.

In Japanese Zen and samurai culture[edit]

In Japan, the influence of Zen Buddhist contemplation of death on indigenous culture can be gauged by the following quotation from the classic treatise on samurai ethics, Hagakure:[24]

The Way of the Samurai is, morning after morning, the practice of death, considering whether it will be here or be there, imagining the most sightly way of dying, and putting one’s mind firmly in death. Although this may be a most difficult thing, if one will do it, it can be done. There is nothing that one should suppose cannot be done.[25]

In the annual appreciation of cherry blossom and fall colors, hanami and momijigari, it was philosophized that things are most splendid at the moment before their fall, and to aim to live and die in a similar fashion.[citation needed]

In Tibetan Buddhism[edit]

Tibetan Citipati mask depicting Mahākāla. The skull mask of Citipati is a reminder of the impermanence of life and the eternal cycle of life and death.

In Tibetan Buddhism, there is a mind training practice known as Lojong. The initial stages of the classic Lojong begin with ‘The Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind’, or, more literally, ‘Four Contemplations to Cause a Revolution in the Mind’.[citation needed] The second of these four is the contemplation on impermanence and death. In particular, one contemplates that;

- All compounded things are impermanent.

- The human body is a compounded thing.

- Therefore, death of the body is certain.

- The time of death is uncertain and beyond our control.

There are a number of classic verse formulations of these contemplations meant for daily reflection to overcome our strong habitual tendency to live as though we will certainly not die today.

Lalitavistara Sutra[edit]

The following is from the Lalitavistara Sūtra, a major work in the classical Sanskrit canon:

|

अध्रुवं त्रिभवं शरदभ्रनिभं नटरङ्गसमा जगिर् ऊर्मिच्युती। गिरिनद्यसमं लघुशीघ्रजवं व्रजतायु जगे यथ विद्यु नभे॥ |

The three worlds are fleeting like autumn clouds. Beings are ablaze with the sufferings of sickness and old age, |

The Udānavarga[edit]

A very well known verse in the Pali, Sanskrit and Tibetan canons states [this is from the Sanskrit version, the Udānavarga:

|

सर्वे क्षयान्ता निचयाः पतनान्ताः समुच्छ्रयाः | |

All that is acquired will be lost |

Shantideva, Bodhicaryavatara[edit]

Shantideva, in the Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra ‘Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’ reflects at length:

|

कृताकृतापरीक्षोऽयं मृत्युर्विश्रम्भघातकः। अप्रिया न भविष्यन्ति प्रियो मे न भविष्यति। तत्तत्स्मरणताम याति यद्यद्वस्त्वनुभयते। रात्रिन्दिवमविश्राममायुषो वर्धते व्ययः। यमदूतैर्गृहीतस्य कुतो बन्धुः कुतः सुह्रत्। पुण्यमेकं तदा त्राणं मया तच्च न सेवितम्॥ |

Death does not differentiate between tasks done and undone. My enemies will not remain, nor will my friends remain. Whatever is experienced will fade to a memory. Day and night, a life span unceasingly diminishes, For a person seized by the messengers of Death, |

In more modern Tibetan Buddhist works[edit]

In a practice text written by the 19th century Tibetan master Dudjom Lingpa for serious meditators, he formulates the second contemplation in this way:[28][29]

On this occasion when you have such a bounty of opportunities in terms of your body, environment, friends, spiritual mentors, time, and practical instructions, without procrastinating until tomorrow and the next day, arouse a sense of urgency, as if a spark landed on your body or a grain of sand fell in your eye. If you have not swiftly applied yourself to practice, examine the births and deaths of other beings and reflect again and again on the unpredictability of your lifespan and the time of your death, and on the uncertainty of your own situation. Meditate on this until you have definitively integrated it with your mind… The appearances of this life, including your surroundings and friends, are like last night’s dream, and this life passes more swiftly than a flash of lightning in the sky. There is no end to this meaningless work. What a joke to prepare to live forever! Wherever you are born in the heights or depths of saṃsāra, the great noose of suffering will hold you tight. Acquiring freedom for yourself is as rare as a star in the daytime, so how is it possible to practice and achieve liberation? The root of all mind training and practical instructions is planted by knowing the nature of existence. There is no other way. I, an old vagabond, have shaken my beggar’s satchel, and this is what came out.

The contemporary Tibetan master, Yangthang Rinpoche, in his short text ‘Summary of the View, Meditation, and Conduct’:[30]

|

།ཁྱེད་རྙེད་དཀའ་བ་མི་ཡི་ལུས་རྟེན་རྙེད། །སྐྱེ་དཀའ་བའི་ངེས་འབྱུང་གི་བསམ་པ་སྐྱེས། །མཇལ་དཀའ་བའི་མཚན་ལྡན་གྱི་བླ་མ་མཇལ། །འཕྲད་དཀའ་བ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་དང་འཕྲད། |

You have obtained a human life, which is difficult to find, |

The Tibetan Canon also includes copious materials on the meditative preparation for the death process and intermediate period bardo between death and rebirth. Amongst them are the famous «Tibetan Book of the Dead», in Tibetan Bardo Thodol, the «Natural Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo».

In Islam[edit]

The «remembrance of death» (Arabic: تذكرة الموت, Tadhkirat al-Mawt; deriving from تذكرة, tadhkirah, Arabic for memorandum or admonition), has been a major topic of Islamic spirituality since the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in Medina. It is grounded in the Qur’an, where there are recurring injunctions to pay heed to the fate of previous generations.[31] The hadith literature, which preserves the teachings of Muhammad, records advice for believers to «remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures.»[32] Some Sufis have been called «ahl al-qubur,» the «people of the graves,» because of their practice of frequenting graveyards to ponder on mortality and the vanity of life, based on the teaching of Muhammad to visit graves.[33] Al-Ghazali devotes to this topic the last book of his «The Revival of the Religious Sciences».[34]

Iceland[edit]

The Hávamál («Sayings of the High One»), a 13th-century Icelandic compilation poetically attributed to the god Odin, includes two sections – the Gestaþáttr and the Loddfáfnismál – offering many gnomic proverbs expressing the memento mori philosophy, most famously Gestaþáttr number 77:

|

Deyr fé, |

Animals die, |

See also[edit]

- Gerascophobia (fear of aging)

- Gerontophobia (fear of elderly people)

- Carpe diem

- Et in Arcadia ego

- Mono no aware

- Mortality salience

- Sic transit gloria mundi

- Tempus fugit

- Terror management theory

- Ubi sunt

- Vanitas

- YOLO (aphorism)

References[edit]

- ^ Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. 89. ISBN 1904449247

- ^ a b Literally ‘remember (that you have) to die’, Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, June 2001.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, ss.vv.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, s.v.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Book IX, Chapter 7, Section 38

- ^ Phaedo, 64a4.

- ^ See his Moral Letters to Lucilius.

- ^ Discourses of Epictetus, 3.24.

- ^ Henry Albert Fischel, Rabbinic Literature and Greco-Roman Philosophy: A Study of Epicurea and Rhetorica in Early Midrashic Writings, E. J. Brill, 1973, p. 95.

- ^ Marcus Aurelius, Meditations IV. 48.2.

- ^ Beard, Mary: The Roman Triumph, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 2007. (hardcover), pp. 85–92.

- ^ «Final Farewell: The Culture of Death and the Afterlife». Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 2010-06-06. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph, Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 0674032187, pp. 85–92

- ^ Christian Dogmatics, Volume 2 (Carl E. Braaten, Robert W. Jenson), page 583

- ^ See Jeremy Taylor, Holy Living and Holy Dying.

- ^ Taylor, Gerald; Scarisbrick, Diana (1978). Finger Rings From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. Ashmolean Museum. p. 76. ISBN 0900090545.

- ^ a b «Memento Mori». Antique Jewelry University. Lang Antiques. n.d. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Bond, Charlotte (December 5, 2018). «Somber «Memento Mori» Jewelry Commissioned to Help People Mourn». The Vintage News. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Michael John Brennan, ed., The A–Z of Death and Dying: Social, Medical, and Cultural Aspects, ISBN 1440803447, s.v. «Memento Mori», p. 307f and s.v. «Ars Moriendi», p. 44

- ^ F. McGahan, «Paulists», The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Paulists

- ^ E. Obrecht, «Trappists», The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Trappists

- ^ Stanley Brandes. «Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond». Chapter 5: The Poetics of Death. John Wiley & Sons, 2009

- ^ Macdonald, Fiona. «What it really means to ‘Seize the day’«. BBC. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ «Hagakure: Book of the Samurai». www.themathesontrust.org. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ «A Buddhist Guide to Death, Dying and Suffering». www.urbandharma.org. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ «84000 Reading Room | The Play in Full». 84000 Translating The Words of The Budda.

- ^ Udānavarga, 1:22.

- ^ «Foolish Dharma of an Idiot Clothed in Mud and Feathers, in ‘Dujdom Lingpa’s Visions of the Great Perfection, Volume 1’, B. Alan Wallace (translator), Wisdom Publications».

An oral commentary by the translator is available on YouTube - ^ «Natural Liberation | Wisdom Publications». Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ The English text is available here. Archived 2018-05-14 at the Wayback Machine The Tibetan text is available here. Oral Commentary by a student of Rinpoche, B. Alan Wallace, is available here.

- ^ For instance, sura «Yasin», 36:31, «Have they not seen how many generations We destroyed before them, which indeed returned not unto them?».

- ^ «Riyad as-Salihin 579 – The Book of Miscellany – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)». sunnah.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ «Sunan Abi Dawud 3235 – Funerals (Kitab Al-Jana’iz) – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)». sunnah.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Al-Ghazali on Death and the Afterlife, tr. by T.J. Winter. Cambridge, Islamic Texts Society, 1989.

External links[edit]

Media related to Memento mori at Wikimedia Commons

This article is about the philosophical reminder of death’s inevitability. For other uses, see Memento mori (disambiguation).

The outer panels of Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque Triptych (c. 1452) show the skull of the patron displayed on the inner panels. The bones rest on a brick, a symbol of his former industry and achievement.[1]

Memento mori (Latin for ‘remember that you [have to] die’[2]) is an artistic or symbolic trope acting as a reminder of the inevitability of death.[2] The concept has its roots in the philosophers of classical antiquity and Christianity, and appeared in funerary art and architecture from the medieval period onwards.

The most common motif is a skull, often accompanied by one or more bones. Often this alone is enough to evoke the trope, but other motifs such as a coffin, hourglass and wilting flowers signify the impermanence of human life. Often these function within a work whose main subject is something else, such as a portrait, but the vanitas is an artistic genre where the theme of death is the main subject. The Danse Macabre and Death personified with a scythe as the Grim Reaper are even more direct evocations of the trope.

Pronunciation and translation[edit]

In English, the phrase is pronounced , mə-MEN-toh MOR-ee.

Memento is the 2nd person singular active imperative of meminī, ‘to remember, to bear in mind’, usually serving as a warning: «remember!» Morī is the present infinitive of the deponent verb morior ‘to die’.[3]

In other words, «remember death» or «remember that you die».[4]

History of the concept[edit]

In classical antiquity[edit]

The philosopher Democritus trained himself by going into solitude and frequenting tombs.[5] Plato’s Phaedo, where the death of Socrates is recounted, introduces the idea that the proper practice of philosophy is «about nothing else but dying and being dead».[6]

The Stoics of classical antiquity were particularly prominent in their use of this discipline, and Seneca’s letters are full of injunctions to meditate on death.[7] The Stoic Epictetus told his students that when kissing their child, brother, or friend, they should remind themselves that they are mortal, curbing their pleasure, as do «those who stand behind men in their triumphs and remind them that they are mortal».[8] The Stoic Marcus Aurelius invited the reader (himself) to «consider how ephemeral and mean all mortal things are» in his Meditations.[9][10]

In some accounts of the Roman triumph, a companion or public slave would stand behind or near the triumphant general during the procession and remind him from time to time of his own mortality or prompt him to «look behind».[11] A version of this warning is often rendered into English as «Remember, Caesar, thou art mortal», for example in Fahrenheit 451.

In Judaism[edit]

Several passages in the Old Testament urge a remembrance of death. In Psalm 90, Moses prays that God would teach his people «to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom» (Ps. 90:12). In Ecclesiastes, the Preacher insists that «It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting, for this is the end of all mankind, and the living will lay it to heart» (Eccl. 7:2). In Isaiah, the lifespan of human beings is compared to the short lifespan of grass: «The grass withers, the flower fades when the breath of the LORD blows on it; surely the people are grass» (Is. 40:7).

In early Christianity[edit]

The expression memento mori developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation of the soul in the afterlife.[12]

The 2nd-century Christian writer Tertullian claimed that during his triumphal procession, a victorious general would have someone (in later versions, a slave) standing behind him, holding a crown over his head and whispering «Respice post te. Hominem te memento» («Look after you [to the time after your death] and remember you’re [only] a man.»). Though in modern times this has become a standard trope, in fact no other ancient authors confirm this, and it may have been Christian moralizing rather than an accurate historical report.[13]

In Europe from the medieval era to the Victorian era[edit]

Dance of Death (replica of 15th century fresco; National Gallery of Slovenia). No matter one’s station in life, the Dance of Death unites all.

Philosophy[edit]

The thought was then utilized in Christianity, whose strong emphasis on divine judgment, heaven, hell, and the salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness.[14] In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the nunc est bibendum (now is the time to drink) theme of classical antiquity. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one’s thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with the memento mori in this context is In omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis (the Vulgate’s Latin rendering of Ecclesiasticus 7:40, «in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.») This finds ritual expression in the rites of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshipers’ heads with the words, «Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust, you shall return.»

Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.[15]

Architecture[edit]

The most obvious places to look for memento mori meditations are in funeral art and architecture. Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is the transi or cadaver tomb, a tomb that depicts the decayed corpse of the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still offer a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. Later, Puritan tomb stones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles. These are among the numerous themes associated with skull imagery.

Another example of memento mori is provided by the chapels of bones, such as the Capela dos Ossos in Évora or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. These are chapels where the walls are totally or partially covered by human remains, mostly bones. The entrance to the Capela dos Ossos has the following sentence: «We bones, lying here bare, await yours.»

Visual art[edit]

Timepieces have been used to illustrate that the time of the living on Earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Public clocks would be decorated with mottos such as ultima forsan («perhaps the last» [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat («they all wound, and the last kills»). Clocks have carried the motto tempus fugit, «time flees». Old striking clocks often sported automata who would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks from Augsburg, Germany, had Death striking the hour. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality. Mary, Queen of Scots owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace, «Pale death knocks with the same tempo upon the huts of the poor and the towers of Kings.»

In the late 16th and through the 17th century, memento mori jewelry was popular. Items included mourning rings,[16] pendants, lockets, and brooches.[17] These pieces depicted tiny motifs of skulls, bones, and coffins, in addition to messages and names of the departed, picked out in precious metals and enamel.[17][18]

During the same period there emerged the artistic genre known as vanitas, Latin for «emptiness» or «vanity». Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies, and hourglasses. In combination, vanitas assemblies conveyed the impermanence of human endeavours and of the decay that is inevitable with the passage of time. See also the themes associated with the image of the skull.

Literature[edit]

Memento mori is also an important literary theme. Well-known literary meditations on death in English prose include Sir Thomas Browne’s Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and Jeremy Taylor’s Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works were part of a Jacobean cult of melancholia that marked the end of the Elizabethan era. In the late eighteenth century, literary elegies were a common genre; Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Edward Young’s Night Thoughts are typical members of the genre.

In the European devotional literature of the Renaissance, the Ars Moriendi, memento mori had moral value by reminding individuals of their mortality.[19]

Music[edit]

Apart from the genre of requiem and funeral music, there is also a rich tradition of memento mori in the Early Music of Europe. Especially those facing the ever-present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemics from the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-given vale of tears with death as a ransom, and they reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgment Day. The following two Latin stanzas (with their English translations) are typical of memento mori in medieval music; they are from the virelai ad mortem festinamus of the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399:

|

Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur, Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus |

Life is short, and shortly it will end; If you do not turn back and become like a child, |

Danse macabre[edit]

The danse macabre is another well-known example of the memento mori theme, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches.

Gallery[edit]

-

Memento mori ring, with enameled skull and «Die to Live» message (between 1500 and 1650, British Museum, London, England)

-

-

Memento mori in the form of a small coffin, 1700s, wax figure on silk in a wooden coffin (Museum Schnütgen, Cologne, Germany)

The salutation of the Hermits of St. Paul of France[edit]

Memento mori was the salutation used by the Hermits of St. Paul of France (1620–1633), also known as the Brothers of Death.[20] It is sometimes claimed that the Trappists use this salutation, but this is not true.[21]

In Puritan America[edit]

Colonial American art saw a large number of memento mori images due to Puritan influence. The Puritan community in 17th-century North America looked down upon art because they believed that it drew the faithful away from God and, if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records and, as such, they were allowed. Thomas Smith, a 17th-century Puritan, fought in many naval battles and also painted. In his self-portrait, we see these pursuits represented alongside a typical Puritan memento mori with a skull, suggesting his awareness of imminent death.

The poem underneath the skull emphasizes Thomas Smith’s acceptance of death and of turning away from the world of the living:

Why why should I the World be minding, Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

Mexico’s Day of the Dead[edit]

Much memento mori art is associated with the Mexican festival Day of the Dead, including skull-shaped candies and bread loaves adorned with bread «bones».

This theme was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which people from various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

Another manifestation of memento mori is found in the Mexican «Calavera», a literary composition in verse form normally written in honour of a person who is still alive, but written as if that person were dead. These compositions have a comedic tone and are often offered from one friend to another during Day of the Dead.[22]

Contemporary culture[edit]

Roman Krznaric suggests Memento Mori is an important topic to bring back into our thoughts and belief system; «Philosophers have come up with lots of what I call ‘death tasters’ – thought experiments for seizing the day.»

These thought experiments are powerful to get us re-oriented back to death into current awareness and living with spontaneity. Albert Camus stated «Come to terms with death, thereafter anything is possible.» Jean-Paul Sartre expressed that life is given to us early, and is shortened at the end, all the while taken away at every step of the way, emphasizing that the end is only the beginning every day.[23]

Similar concepts in other religions and cultures[edit]

In Buddhism[edit]

The Buddhist practice maraṇasati meditates on death. The word is a Pāli compound of maraṇa ‘death’ (an Indo-European cognate of Latin mori) and sati ‘awareness’, so very close to memento mori. It is first used in early Buddhist texts, the suttapiṭaka of the Pāli Canon, with parallels in the āgamas of the «Northern» Schools.

In Japanese Zen and samurai culture[edit]

In Japan, the influence of Zen Buddhist contemplation of death on indigenous culture can be gauged by the following quotation from the classic treatise on samurai ethics, Hagakure:[24]

The Way of the Samurai is, morning after morning, the practice of death, considering whether it will be here or be there, imagining the most sightly way of dying, and putting one’s mind firmly in death. Although this may be a most difficult thing, if one will do it, it can be done. There is nothing that one should suppose cannot be done.[25]

In the annual appreciation of cherry blossom and fall colors, hanami and momijigari, it was philosophized that things are most splendid at the moment before their fall, and to aim to live and die in a similar fashion.[citation needed]

In Tibetan Buddhism[edit]

Tibetan Citipati mask depicting Mahākāla. The skull mask of Citipati is a reminder of the impermanence of life and the eternal cycle of life and death.

In Tibetan Buddhism, there is a mind training practice known as Lojong. The initial stages of the classic Lojong begin with ‘The Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind’, or, more literally, ‘Four Contemplations to Cause a Revolution in the Mind’.[citation needed] The second of these four is the contemplation on impermanence and death. In particular, one contemplates that;

- All compounded things are impermanent.

- The human body is a compounded thing.

- Therefore, death of the body is certain.

- The time of death is uncertain and beyond our control.

There are a number of classic verse formulations of these contemplations meant for daily reflection to overcome our strong habitual tendency to live as though we will certainly not die today.

Lalitavistara Sutra[edit]

The following is from the Lalitavistara Sūtra, a major work in the classical Sanskrit canon:

|

अध्रुवं त्रिभवं शरदभ्रनिभं नटरङ्गसमा जगिर् ऊर्मिच्युती। गिरिनद्यसमं लघुशीघ्रजवं व्रजतायु जगे यथ विद्यु नभे॥ |

The three worlds are fleeting like autumn clouds. Beings are ablaze with the sufferings of sickness and old age, |

The Udānavarga[edit]

A very well known verse in the Pali, Sanskrit and Tibetan canons states [this is from the Sanskrit version, the Udānavarga:

|

सर्वे क्षयान्ता निचयाः पतनान्ताः समुच्छ्रयाः | |

All that is acquired will be lost |

Shantideva, Bodhicaryavatara[edit]

Shantideva, in the Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra ‘Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’ reflects at length:

|

कृताकृतापरीक्षोऽयं मृत्युर्विश्रम्भघातकः। अप्रिया न भविष्यन्ति प्रियो मे न भविष्यति। तत्तत्स्मरणताम याति यद्यद्वस्त्वनुभयते। रात्रिन्दिवमविश्राममायुषो वर्धते व्ययः। यमदूतैर्गृहीतस्य कुतो बन्धुः कुतः सुह्रत्। पुण्यमेकं तदा त्राणं मया तच्च न सेवितम्॥ |

Death does not differentiate between tasks done and undone. My enemies will not remain, nor will my friends remain. Whatever is experienced will fade to a memory. Day and night, a life span unceasingly diminishes, For a person seized by the messengers of Death, |

In more modern Tibetan Buddhist works[edit]

In a practice text written by the 19th century Tibetan master Dudjom Lingpa for serious meditators, he formulates the second contemplation in this way:[28][29]

On this occasion when you have such a bounty of opportunities in terms of your body, environment, friends, spiritual mentors, time, and practical instructions, without procrastinating until tomorrow and the next day, arouse a sense of urgency, as if a spark landed on your body or a grain of sand fell in your eye. If you have not swiftly applied yourself to practice, examine the births and deaths of other beings and reflect again and again on the unpredictability of your lifespan and the time of your death, and on the uncertainty of your own situation. Meditate on this until you have definitively integrated it with your mind… The appearances of this life, including your surroundings and friends, are like last night’s dream, and this life passes more swiftly than a flash of lightning in the sky. There is no end to this meaningless work. What a joke to prepare to live forever! Wherever you are born in the heights or depths of saṃsāra, the great noose of suffering will hold you tight. Acquiring freedom for yourself is as rare as a star in the daytime, so how is it possible to practice and achieve liberation? The root of all mind training and practical instructions is planted by knowing the nature of existence. There is no other way. I, an old vagabond, have shaken my beggar’s satchel, and this is what came out.

The contemporary Tibetan master, Yangthang Rinpoche, in his short text ‘Summary of the View, Meditation, and Conduct’:[30]

|

།ཁྱེད་རྙེད་དཀའ་བ་མི་ཡི་ལུས་རྟེན་རྙེད། །སྐྱེ་དཀའ་བའི་ངེས་འབྱུང་གི་བསམ་པ་སྐྱེས། །མཇལ་དཀའ་བའི་མཚན་ལྡན་གྱི་བླ་མ་མཇལ། །འཕྲད་དཀའ་བ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་དང་འཕྲད། |

You have obtained a human life, which is difficult to find, |

The Tibetan Canon also includes copious materials on the meditative preparation for the death process and intermediate period bardo between death and rebirth. Amongst them are the famous «Tibetan Book of the Dead», in Tibetan Bardo Thodol, the «Natural Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo».

In Islam[edit]

The «remembrance of death» (Arabic: تذكرة الموت, Tadhkirat al-Mawt; deriving from تذكرة, tadhkirah, Arabic for memorandum or admonition), has been a major topic of Islamic spirituality since the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in Medina. It is grounded in the Qur’an, where there are recurring injunctions to pay heed to the fate of previous generations.[31] The hadith literature, which preserves the teachings of Muhammad, records advice for believers to «remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures.»[32] Some Sufis have been called «ahl al-qubur,» the «people of the graves,» because of their practice of frequenting graveyards to ponder on mortality and the vanity of life, based on the teaching of Muhammad to visit graves.[33] Al-Ghazali devotes to this topic the last book of his «The Revival of the Religious Sciences».[34]

Iceland[edit]

The Hávamál («Sayings of the High One»), a 13th-century Icelandic compilation poetically attributed to the god Odin, includes two sections – the Gestaþáttr and the Loddfáfnismál – offering many gnomic proverbs expressing the memento mori philosophy, most famously Gestaþáttr number 77:

|

Deyr fé, |

Animals die, |

See also[edit]

- Gerascophobia (fear of aging)

- Gerontophobia (fear of elderly people)

- Carpe diem

- Et in Arcadia ego

- Mono no aware

- Mortality salience

- Sic transit gloria mundi

- Tempus fugit

- Terror management theory

- Ubi sunt

- Vanitas

- YOLO (aphorism)

References[edit]

- ^ Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. 89. ISBN 1904449247

- ^ a b Literally ‘remember (that you have) to die’, Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, June 2001.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, ss.vv.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, s.v.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Book IX, Chapter 7, Section 38

- ^ Phaedo, 64a4.

- ^ See his Moral Letters to Lucilius.

- ^ Discourses of Epictetus, 3.24.

- ^ Henry Albert Fischel, Rabbinic Literature and Greco-Roman Philosophy: A Study of Epicurea and Rhetorica in Early Midrashic Writings, E. J. Brill, 1973, p. 95.

- ^ Marcus Aurelius, Meditations IV. 48.2.

- ^ Beard, Mary: The Roman Triumph, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 2007. (hardcover), pp. 85–92.

- ^ «Final Farewell: The Culture of Death and the Afterlife». Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 2010-06-06. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph, Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 0674032187, pp. 85–92

- ^ Christian Dogmatics, Volume 2 (Carl E. Braaten, Robert W. Jenson), page 583

- ^ See Jeremy Taylor, Holy Living and Holy Dying.

- ^ Taylor, Gerald; Scarisbrick, Diana (1978). Finger Rings From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. Ashmolean Museum. p. 76. ISBN 0900090545.

- ^ a b «Memento Mori». Antique Jewelry University. Lang Antiques. n.d. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Bond, Charlotte (December 5, 2018). «Somber «Memento Mori» Jewelry Commissioned to Help People Mourn». The Vintage News. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Michael John Brennan, ed., The A–Z of Death and Dying: Social, Medical, and Cultural Aspects, ISBN 1440803447, s.v. «Memento Mori», p. 307f and s.v. «Ars Moriendi», p. 44

- ^ F. McGahan, «Paulists», The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Paulists

- ^ E. Obrecht, «Trappists», The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Trappists

- ^ Stanley Brandes. «Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond». Chapter 5: The Poetics of Death. John Wiley & Sons, 2009

- ^ Macdonald, Fiona. «What it really means to ‘Seize the day’«. BBC. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ «Hagakure: Book of the Samurai». www.themathesontrust.org. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ «A Buddhist Guide to Death, Dying and Suffering». www.urbandharma.org. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ «84000 Reading Room | The Play in Full». 84000 Translating The Words of The Budda.

- ^ Udānavarga, 1:22.

- ^ «Foolish Dharma of an Idiot Clothed in Mud and Feathers, in ‘Dujdom Lingpa’s Visions of the Great Perfection, Volume 1’, B. Alan Wallace (translator), Wisdom Publications».

An oral commentary by the translator is available on YouTube - ^ «Natural Liberation | Wisdom Publications». Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ The English text is available here. Archived 2018-05-14 at the Wayback Machine The Tibetan text is available here. Oral Commentary by a student of Rinpoche, B. Alan Wallace, is available here.

- ^ For instance, sura «Yasin», 36:31, «Have they not seen how many generations We destroyed before them, which indeed returned not unto them?».

- ^ «Riyad as-Salihin 579 – The Book of Miscellany – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)». sunnah.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ «Sunan Abi Dawud 3235 – Funerals (Kitab Al-Jana’iz) – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)». sunnah.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Al-Ghazali on Death and the Afterlife, tr. by T.J. Winter. Cambridge, Islamic Texts Society, 1989.

External links[edit]

Media related to Memento mori at Wikimedia Commons

Правильно ли сказал учитель?

Автор vyukov, июля 15, 2014, 12:35

0 Пользователи и 1 гость просматривают эту тему.

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Учитель по латинскому говорил что Momento more — помни обычаи, а помни о смерти momento mori , а везде написано memento mori помни о смерти как правильно подскажите?

Centum Satәm

-

- Сообщения: 4,569

- Записан

Помни о смерти memento mori букв. «помни умирать»

Только не

momento

ἔχουσιν οἱ βίοι τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἡδονὰς καὶ λύπας· ὅπου ὑπερβάλλουσιν αἱ ἡδοναὶ τὰς λύπας͵ τοῦτον τὸν βίον ἡδίω κεκρίκαμεν

θνητῶν μηδεὶς μηδένα ὄλβιον κρίνῃ͵ πρὶν αὐτὸν εὖ τελευτήσαντα ἲδῃ

ΔΕΙΝΗ ΑΝΑΓΚΗ ΠΑΝΤΑ ΚΡΑΤΥΝΕΙ

Neve aliquid nostri post mortem posse relinqui…

Mors sola fatetur quantula sint hominum corpuscula

Vertaler

-

- Сообщения: 11,433

- Vielzeller

- Записан

Во-первых, не надо путать глагольную форму mementō ‘помни, не забудь’ с именной формой mōmentō ‘движению, движением’.

Во-вторых, meminī употребляется с аккузативом (mōrem) или генитивом (mōris), но не с аблативом (mōre).

Mementō morī — дословно ‘не забудь умереть’.

Стрч прст в крк и вынь сухим.

RNK

-

- Сообщения: 321

- Записан

Иногда доводится слышать в шутку: «Моменто мори — лови момент!»

ḲelHä weṭei ʕaḲun kähla / ḳaλai palhʌ-ḳʌ na wetä / śa da ʔa-ḳʌ ʔeja ʔälä / ja-ḳo pele ṭuba wete

Georgos Therapon

-

- Сообщения: 4,036

- Записан

Про глагол memini в словаре Дворецкого написано:

Цитироватьmeminisse alicujus rei или aliquid (редко de aliqua re) – помнить о чем-либо (что-либо)

Поэтому «помни обычаи» можно перевести как «memento morum» или «memento mores», или, как допустимый, но редкий вариант, «memento de moribus».

«Помни обычай» можно перевести как «memento moris», «memento morem», или «memento de more». Что же касается «memento more», то это уже «кухонная латынь».

Глагол memini является одним из глаголов sentiendi et declarandi и может иметь в качестве дополнения оборот accusativus cum infinitivo. Следовательно, можно сказать memento te mori (помни, что ты умрешь). Если опустить местоимение te, то получится memento mori, что переводят как «помни о смерти».

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Извините, если я туплю уважаемые филологи, но получается с правильной орфографией, это выражение будет выглядеть так memento te mori — помни что ты умрешь?

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Вы говорите что memento mori — это кухонная латынь, уважаемый в Чехии в городе Кутна Гора есть целая галерея «MEMENTO MORI». Украшения часовни XVII века, с таким рисунком, это тоже кухонный перевод? Я просто хочу понять а как оно на самом деле)? Извините за мою назойливость)

Vertaler

-

- Сообщения: 11,433

- Vielzeller

- Записан

Respice post te! Hominem te esse memento! Memento mori!

Действительно, получается, один раз tē уже сказано, и третья фраза была сильно эллиптической.

«Оглянись! Вспомни, что ты человек! И что умрёшь — вспомни!»

Далее любители заковыристых латинских выражений берут последние слова «что умрёшь — (вс)помни» и используют его в несколько другом значении и в других целях.

Стрч прст в крк и вынь сухим.

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Не совсем вас понял объясните пожалуйста, если не затруднит)

Vertaler

-

- Сообщения: 11,433

- Vielzeller

- Записан

Отредактировал сообщение. Смысл в том, что фраза mementō morī звучит близко к русскому «что умрёшь — (вс)помни», настолько же ситуативно и настолько же коряво вне контекста. Насколько я понял.

Стрч прст в крк и вынь сухим.

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Но в общем грамматически данное выражение построено правильно и перевод помни умрешь , скажем в 90% будет переведено именно так memento more)?

Vertaler

-

- Сообщения: 11,433

- Vielzeller

- Записан

Цитата: vyukov от июля 15, 2014, 15:03

Но в общем грамматически данное выражение построено правильно и перевод помни умрешь , скажем в 90% будет переведено именно так memento more)?

Да, только с долгим -i на конце, с показателем пассивного инфинитива.

И да, «помни: умрёшь» — тоже хороший вариант перевода на русский.

Стрч прст в крк и вынь сухим.

agrammatos

-

- Сообщения: 1,238

- …я споткнулся о камень, Это к завтраму всё заживёт

- Записан

Цитата: Georgos Therapon от июля 15, 2014, 13:44

Что же касается «memento more», то это уже «кухонная латынь».

Цитата: vyukov от июля 15, 2014, 14:36Вы говорите что memento mori — это кухонная латынь

vyukov, простите меня, но мне кажется, что Georgos говорил совсем о другой фразе, а не о той, которую приводите Вы… … …

Якби ви вчились так, як треба,

То й мудрість би була своя.

/ Тарас Шевченко/

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Извините пожалуйста, все понял, увидел, это моя ситуативная невнимательность

vyukov

-

- Сообщения: 52

- Записан

Извините за то что трачу ваше время, последний вопрос

Vertaler

-

- Сообщения: 11,433

- Vielzeller

- Записан

Цитата: vyukov от июля 15, 2014, 15:18

Извините за то что трачу ваше время, последний вопрос, получается что полный вариант был бы memento te mori соответственно, более правильный перевод — по правилам перевода инфинитивных оборотов — «помни, что ты умрешь».

Да.

Только что друг сказал, что его учитель латыни когда-то долго объяснял что-то про это выражение, что именно — он не помнит, но tē там присутствовало. Так что такая трактовка — не наша местная выдумка.

Стрч прст в крк и вынь сухим.

Neeraj

-

- Сообщения: 5,309

- Neeraj

- Записан

Вспомнилось… ὡς αἰεὶ κρυεροῖο παρεσταότος θανάτοιο μνώεο Помни непрестанно страшную смерть, как будто она у тебя перед глазами отсюда

Centum Satәm

-

- Сообщения: 4,569

- Записан

ἔχουσιν οἱ βίοι τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἡδονὰς καὶ λύπας· ὅπου ὑπερβάλλουσιν αἱ ἡδοναὶ τὰς λύπας͵ τοῦτον τὸν βίον ἡδίω κεκρίκαμεν

θνητῶν μηδεὶς μηδένα ὄλβιον κρίνῃ͵ πρὶν αὐτὸν εὖ τελευτήσαντα ἲδῃ

ΔΕΙΝΗ ΑΝΑΓΚΗ ΠΑΝΤΑ ΚΡΑΤΥΝΕΙ

Neve aliquid nostri post mortem posse relinqui…

Mors sola fatetur quantula sint hominum corpuscula

Georgos Therapon

-

- Сообщения: 4,036

- Записан

Цитата: Centum Satәm от июля 15, 2014, 19:01

Цитата: Vertaler от июля 15, 2014, 15:06

И да, «помни: умрёшь» — тоже хороший вариант перевода на русский.Откуда там будущее время взялось?

Я думаю, что дословный перевод должен быть «помни, что умираешь», а замена настоящего на будущее совершенное – это литературная обработка: если умираешь, значит, умрешь.

Centum Satәm

-

- Сообщения: 4,569

- Записан

ἔχουσιν οἱ βίοι τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἡδονὰς καὶ λύπας· ὅπου ὑπερβάλλουσιν αἱ ἡδοναὶ τὰς λύπας͵ τοῦτον τὸν βίον ἡδίω κεκρίκαμεν

θνητῶν μηδεὶς μηδένα ὄλβιον κρίνῃ͵ πρὶν αὐτὸν εὖ τελευτήσαντα ἲδῃ

ΔΕΙΝΗ ΑΝΑΓΚΗ ΠΑΝΤΑ ΚΡΑΤΥΝΕΙ

Neve aliquid nostri post mortem posse relinqui…

Mors sola fatetur quantula sint hominum corpuscula

Centum Satәm

-

- Сообщения: 4,569

- Записан

Цитата: Georgos Therapon от июля 16, 2014, 07:25

Я думаю, что дословный перевод должен быть «помни, что умираешь», а замена настоящего на будущее совершенное – это литературная обработка: если умираешь, значит, умрешь.

Мне кажется, римлянин никогда бы так не сказал: «memento mori». Явно какая-та средневековая ученая латынь.

Будущее время тут не подходит по смыслу, т.к. смысл именно в том, что «умирание» происходит в настоящее время, hoc et nunc, а не то, что оно произойдет когда-нибудь в будущем.

«Помни о том, что ты в каждое мгновение находишься в состоянии умирания»

ἔχουσιν οἱ βίοι τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἡδονὰς καὶ λύπας· ὅπου ὑπερβάλλουσιν αἱ ἡδοναὶ τὰς λύπας͵ τοῦτον τὸν βίον ἡδίω κεκρίκαμεν

θνητῶν μηδεὶς μηδένα ὄλβιον κρίνῃ͵ πρὶν αὐτὸν εὖ τελευτήσαντα ἲδῃ

ΔΕΙΝΗ ΑΝΑΓΚΗ ΠΑΝΤΑ ΚΡΑΤΥΝΕΙ

Neve aliquid nostri post mortem posse relinqui…

Mors sola fatetur quantula sint hominum corpuscula

Flamen

-

- Сообщения: 140

- Записан

«Я думаю, что дословный перевод должен быть

«помни, что умираешь», а замена настоящего

на будущее совершенное – это литературная

обработка: если умираешь, значит, умрешь.»

Скорее «помни о смерти»; другими словами, помни о бренности человеского существования.

Зачем придумывать заковыристые переводы, когда можно сделать по-проще.

И я не смогу поверить в написание memento te mori пока не увижу пример.

«Нужно изучать чтобы знать, знать чтобы понимать, понимать чтобы судить».

«Все есть движение, и кроме движения нет ничего».

Centum Satәm

-

- Сообщения: 4,569

- Записан

…Tamquam semper uicturi uiuitis, numquam uobis fragilitas uestra succurrit, non obseruatis quantum iam temporis transierit; uelut ex pleno et abundanti perditis, cum interim fortasse ille ipse qui alicui uel homini uel rei donatur

dies ultimus sit

. Omnia tamquam mortales timetis, omnia tamquam immortales concupiscitis…

…Non exiguum temporis habemus, sed

multum perdidimus

. Satis longa uita et in maximarum rerum consummationem large data est, si tota bene collocaretur; sed ubi per luxum ac neglegentiam diffluit, ubi nulli bonae rei impenditur, ultima demum necessitate cogente,

quam ire non intelleximus transisse sentimus

. 4 Ita est: non accipimus breuem uitam sed fecimus, nec inopes eius sed prodigi sumus. Sicut amplae et regiae opes, ubi ad malum dominum peruenerunt, momento dissipantur, at quamuis modicae, si bono custodi traditae sunt, usu crescunt:

ita aetas nostra bene disponenti multum patet…

.

http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/sen/sen.brevita.shtml

ἔχουσιν οἱ βίοι τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἡδονὰς καὶ λύπας· ὅπου ὑπερβάλλουσιν αἱ ἡδοναὶ τὰς λύπας͵ τοῦτον τὸν βίον ἡδίω κεκρίκαμεν

θνητῶν μηδεὶς μηδένα ὄλβιον κρίνῃ͵ πρὶν αὐτὸν εὖ τελευτήσαντα ἲδῃ

ΔΕΙΝΗ ΑΝΑΓΚΗ ΠΑΝΤΑ ΚΡΑΤΥΝΕΙ

Neve aliquid nostri post mortem posse relinqui…

Mors sola fatetur quantula sint hominum corpuscula

Georgos Therapon

-

- Сообщения: 4,036

- Записан

Цитата: Flamen от июля 16, 2014, 10:20

Зачем придумывать заковыристые переводы, когда можно сделать по-проще.

Полностью согласен, что придумывать от себя ничего нельзя, но надо стараться максимально точно передать мысль автора. А чтобы понять мысль, надо в первую очередь разобраться с синтаксисом.

Цитата: Flamen от июля 16, 2014, 10:20

И я не смогу поверить в написание memento te mori пока не увижу пример.

Так в это верить и не надо. В грамматике написано, что глагол memini может управлять инфинитивным оборотом. Если здесь инфинитивный оборот, а его логического подлежащего в аккузативе при инфинитиве нет, тогда можно делать вывод, что это подлежащее в эллипсисе, а какое это подлежащее конкретно – бог его знает: может, te, может, omnia, может, еще что-то …

Flamen

-

- Сообщения: 140

- Записан

«Satis longa uita et in maximarum

rerum consummationem large data est, si tota

bene collocaretur; sed ubi per luxum ac

neglegentiam diffluit, ubi nulli bonae rei

impenditur, ultima demum necessitate cogente,

quam ire non intelleximus transisse sentimus . «

Сенека хорошо говорит, и латынь его мне нравится.

Согласен с Вами и я, Georgos, но в данном случае прямой, дословный перевод нисколько не искажает ни смысла ни мысли.

memento это повелительная форма memini в первом лице единственном числе; переводим «помни» и точка.

Далее, mori это творительный падеж от mors; мы знаем, что у латинского ablativus широкий диапазон применения поскольку он объединил в себе три падежа, и мы можем поставить вопрос отталкиваясь от глагола: помнить о чем, о ком? о смерти.

А тут большинство следуя каким-то непонятным метаморфозам превращают mori то в глагол, то в причастие, да еще прикрепляют не к месту и союз взятый из воздуха.

«Нужно изучать чтобы знать, знать чтобы понимать, понимать чтобы судить».

«Все есть движение, и кроме движения нет ничего».

Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Memento mori» в других словарях:

Memento Mori — (film) Pour les articles homonymes, voir Memento mori (homonymie). Memento Mori Titre original Yeogo goedam II (여고괴담 두번째 이야기 :메멘토 모리) Réalisation Kim Tae yong Min Kyu dong Acteurs principaux Lee You … Wikipédia en Français

memento mori — [memɛ̃tomɔʀi] n. m. invar. ÉTYM. 1903; expression latine signifiant « souviens toi que tu es mortel ». ❖ ♦ Objet de piété, tête de mort (en ivoire, rongée par des serpents ou des vers), qui aide à se pénétrer de l idée de néant. || Des memento… … Encyclopédie Universelle

Memento mori — Me*men to mo ri [L.] Lit., remember to die, i.e., that you must die; a warning to be prepared for death; an object, as a death s head or a personal ornament, usually emblematic, used as a reminder of death. [Webster 1913 Suppl.] … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

Memento mori — С латинского: (мэмэнто мори) Помни о смерти. Выражение стало известно как формула приветствия, которым обменивались при встрече друг с другом монахи ордена траппистов, основанного в 1148 г. Его члены принимали на себя обет молчания, чтобы целиком … Словарь крылатых слов и выражений

memento mori — лат. (мэмэнто мори) помни о смерти. Толковый словарь иностранных слов Л. П. Крысина. М: Русский язык, 1998 … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

Memento mori — (lat.), Denk an den Tod! … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

Meménto mori — (lat., »Gedenke des Todes«), Wahlspruch einiger Mönchsorden, z. B. der Kamaldulenser … Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon

Memento mori — Memento mori, lat. = gedenke, daß du sterben mußt … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

memento mori — reminder of death, 1590s, Latin, lit. remember that you must die … Etymology dictionary

memento mori — ► NOUN (pl. same) ▪ an object kept as a reminder that death is inevitable. ORIGIN Latin, remember (that you have) to die … English terms dictionary

memento mori — [mə men′tō mōr′ē, mə men′tō mōr′ī] [L, remember that you must die] any reminder of death … English World dictionary

Источник

10 самых известных латинских изречений

«Латынь из моды вышла ныне», — написал Александр Сергеевич Пушкин в «Евгении Онегине». И ошибся — латинские выражения часто мелькают в нашей речи до сих пор! «Деньги не пахнут», «хлеба и зрелищ», «в здоровом теле здоровый дух»… Все мы используем эти афоризмы, некоторым из которых по двадцать веков! Мы выбрали 10 самых-самых известных.

1. Ab ovo

По римским обычаям обед начинался с яиц и заканчивался фруктами. Именно отсюда принято выводить выражение «с яйца» или на латыни «ab ovo», означающее «с самого начала». Именно они, яйца и яблоки, упомянуты в сатирах Горация. Но тот же римский поэт Квинт Гораций Флакк затуманивает картинку, когда употребляет выражение «ab ovo» в «Науке поэзии», по отношению к слишком затянутому предисловию. И здесь смысл другой: начать с незапамятных времен. И яйца другие: Гораций приводит в пример рассказ о Троянской войне, начатый с яиц Леды. Из одного яйца, снесенного этой мифологической героиней от связи с Зевсом в образе Лебедя, явилась на свет Елена Прекрасная. А ее похищение, как известно из мифологии, стало поводом к Троянской войне.

2. O tempora! O mores!

21 октября 63 года до нашей эры консул Цицерон произнес в Сенате пламенную речь, и она имела для Древнего Рима судьбоносное значение. Накануне Цицерон получил сведения о намерениях вождя плебса и молодежи Луция Сергия Катилины совершить переворот и убийство самого Марка Туллия Цицерона. Планы получили огласку, замыслы заговорщиков были сорваны. Катилину выслали из Рима и объявил врагом государства. А Цицерону, напротив, устроили триумф и наградили титулом «отец отечества». Так вот, это противостояние Цицерона и Катилины обогатило наш с вами язык: именно в речах против Катилины Цицерон впервые употребил выражение «O tempora! O mores!», что по-русски значит «О времена! О нравы!».

3. Feci quod potui faciant meliora potentes

Feci quod potui faciant meliora potentes, то есть «Я сделал всё, что мог, пусть те, кто могут, сделают лучше». Изящная формулировка не затеняет сути: вот мои достижения, судите, говорит некто, подводя итоги своей деятельности. Впрочем, почему некто? В истоке выражения обнаруживаются вполне конкретные люди — римские консулы. Это у них бытовала словесная формула, которой они заканчивали свою отчетную речь, когда передавали полномочия преемникам. Это были не именно эти слова — отточенность фраза приобрела в поэтическом пересказе. И именно в этом, законченном виде, она выбита на надгробной плите знаменитого польского философа и писателя Станислава Лема.

4. Panem et circenses

Этот народ уж давно, с той поры, как свои голоса мы

Не продаем, все заботы забыл, и Рим, что когда-то

Все раздавал: легионы, и власть, и ликторов связки,

Сдержан теперь и о двух лишь вещах беспокойно мечтает:

Хлеба и зрелищ!

В оригинале 10-й сатиры древнеримского поэта-сатирика Ювенала стоит «panem et circenses», то есть «хлеба и цирковых игр». Живший в I веке нашей эры Децим Юний Ювенал правдиво описал нравы современного ему римского общества. Чернь требовала еды и развлечений, политики с удовольствием развращали плебс подачками и покупали таким образом поддержку. Рукописи не горят, и в изложении Ювенала клич римской черни времен Октавиана Августа, Нерона и Траяна, преодолел толщу веков и по- прежнему означает нехитрые потребности бездумных людей, которых легко купить политику-популисту.

5. Pecunianonolet

Всем известно, что деньги не пахнут. Гораздо меньше народу знает, кто сказал эту знаменитую фразу, и откуда вдруг выплыла тема запахов. Между тем, афоризму почти двадцать веков: согласно римскому историку Гаю Светонию Транквиллу, «Pecunia non olet» — это ответ римского же императора Веспасиана, правившего в I веке нашей эры, на упрек его сына Тита. Отпрыск упрекнул Веспасиана в том, что он ввел налог на общественные уборные. Веспасиан поднес к носу сына деньги, полученные в качестве этого налога, и спросил, пахнут ли они. Тит ответил отрицательно. «И все-таки они из мочи», — констатировал Веспасиан. И таким образом снабдил оправданием всех любителей нечистых доходов.

6. Memento mori

Когда римский полководец возвращался с поля сражения в столицу, его встречала ликующая толпа. Триумф мог бы вскружить ему голову, но римляне предусмотрительно включили в сценарий государственного раба с одной-единственной репликой. Он стоял за спиной военачальника, держал над его головой золотой венок и время от времени повторял: «Memento mori». То есть: «Помни о смерти». «Помни, что смертен, — заклинали триумфатора римляне, — помни, что ты — человек, и тебе придется умирать. Слава преходяща, а жизнь не вечна». Есть, правда, версия, что настоящая фраза звучала так: «Respice post te! Hominem te memento! Memento mori», в переводе: «Обернись! Помни, что ты — человек! Помни о смерти». В таком виде фразу обнаружили в «Апологетике» раннехристианского писателя Квинта Септимия Флоренса Тертуллиана, жившего на рубеже II и III веков. «Моментально в море» — пошутили в фильме «Кавказская пленница».

7. Mens sana in corpore sano

Когда мы хотим сказать, что только физически здоровый человек энергичен и может многое совершить, мы часто употребляем формулу: «в здоровом теле здоровый дух». А ведь её автор имел в виду совсем другое! В своей десятой сатире римский поэт Децим Юний Ювенал написал:

Надо молить, чтобы ум был здравым в теле здоровом.

Бодрого духа проси, что не знает страха пред смертью,

Что почитает за дар природы предел своей жизни,

Что в состоянье терпеть затрудненья какие угодно…

Таким образом, римский сатирик никак не связывал здоровье ума и духа со здоровьем тела. Скорее, он был уверен, что гора мышц не способствует бодрости духа и живости ума. Кто же подредактировал текст, созданный во II веке нашей эры? Английский философ Джон Локк повторил фразу Ювенала в своей работе «Мысли о воспитании», придав ей вид афоризма и полностью исказив смысл. Популярным этот афоризм сделал Жан-Жак Руссо: он вставил его в книгу «Эмиль, или О воспитании».

8. Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto

Во II веке до нашей эры римский комедиограф Публий Теренций Афр представил публике ремейк комедии греческого писателя Менандра, жившего в IV веке до нашей эры. В комедии под названием «Самоистязатель» старик Меденем упрекает старика Хремета в том, что он вмешивается в чужие дела и пересказывает сплетни.

Неужто мало дела у тебя, Хремет?

В чужое дело входишь! Да тебя оно

Совсем и не касается.

Хремет оправдывается:

Я — человек!

Не чуждо человеческое мне ничто.

Довод Хремета услышали и повторяют больше двух тысячелетий. Фраза «Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto», то есть «Я человек, и ничто человеческое мне не чуждо», вошла в нашу речь. И означает обычно, что любой, даже высокоинтеллектуальный человек носит в себе все слабости человеческой природы.

9. Veni, vidi, vici

2 августа по нынешнему календарю 47 года до нашей эры Гай Юлий Цезарь одержал победу недалеко от понтийского города Зела над царем боспорского государства Фарнаком. Фарнак нарвался сам: после недавней победы над римлянами он был самоуверен и отчаянно храбр. Но фортуна изменила черноморцам: армию Фарнака разгромили, укрепленный лагерь взяли штурмом, сам Фарнак еле успел унести ноги. Отдышавшись после недолгого сражения, Цезарь написал другу Матию в Рим письмо, в котором сообщил о победе буквально в трех словах: «Пришел, увидел, победил». «Veni, vidi, vici», если по-латыни.

10. In vino veritas

И это латинские перепевы греческой философской мысли! Фразу «Вино — милое детя, оно же — правда» приписывают Алкею, творившему на рубеже VII — VI веков до нашей эры. За Алкеем ее повторил в XIV книге «Естественной истории» Плиний Старший: «По пословице — истина в вине». Древнеримский писатель-энциклопедист хотел подчеркнуть, что вино развязывает языки, и тайное выходит наружу. Суждение Плиния Старшего подтверждает, кстати сказать, русская народная мудрость: «Что у трезвого на уме, то у пьяного на языке». Но в погоне за красным словцом, Гай Плиний Секунд и обрезал пословицу, которая на латыни длиннее и означает совсем иное. «In vino veritas, in aqua sanitas», то есть в вольном переводе с латыни «Истина, может, и в вине, но здоровье — в воде».

Источник

memento mori

1 Memento mori

2 Memento mori

3 Помни о смерти

См. также в других словарях:

Memento Mori — (film) Pour les articles homonymes, voir Memento mori (homonymie). Memento Mori Titre original Yeogo goedam II (여고괴담 두번째 이야기 :메멘토 모리) Réalisation Kim Tae yong Min Kyu dong Acteurs principaux Lee You … Wikipédia en Français

memento mori — [memɛ̃tomɔʀi] n. m. invar. ÉTYM. 1903; expression latine signifiant « souviens toi que tu es mortel ». ❖ ♦ Objet de piété, tête de mort (en ivoire, rongée par des serpents ou des vers), qui aide à se pénétrer de l idée de néant. || Des memento… … Encyclopédie Universelle

Memento mori — Me*men to mo ri [L.] Lit., remember to die, i.e., that you must die; a warning to be prepared for death; an object, as a death s head or a personal ornament, usually emblematic, used as a reminder of death. [Webster 1913 Suppl.] … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

Memento mori — С латинского: (мэмэнто мори) Помни о смерти. Выражение стало известно как формула приветствия, которым обменивались при встрече друг с другом монахи ордена траппистов, основанного в 1148 г. Его члены принимали на себя обет молчания, чтобы целиком … Словарь крылатых слов и выражений

memento mori — лат. (мэмэнто мори) помни о смерти. Толковый словарь иностранных слов Л. П. Крысина. М: Русский язык, 1998 … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

Memento mori — (lat.), Denk an den Tod! … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

Meménto mori — (lat., »Gedenke des Todes«), Wahlspruch einiger Mönchsorden, z. B. der Kamaldulenser … Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon

Memento mori — Memento mori, lat. = gedenke, daß du sterben mußt … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

memento mori — reminder of death, 1590s, Latin, lit. remember that you must die … Etymology dictionary

memento mori — ► NOUN (pl. same) ▪ an object kept as a reminder that death is inevitable. ORIGIN Latin, remember (that you have) to die … English terms dictionary

memento mori — [mə men′tō mōr′ē, mə men′tō mōr′ī] [L, remember that you must die] any reminder of death … English World dictionary

Источник

memento mori

1 memento mori

2 Memento mori

3 memento mori

4 memento mori

5 memento mori

6 memento mori

7 memento vivere

См. также в других словарях:

Memento Mori — (film) Pour les articles homonymes, voir Memento mori (homonymie). Memento Mori Titre original Yeogo goedam II (여고괴담 두번째 이야기 :메멘토 모리) Réalisation Kim Tae yong Min Kyu dong Acteurs principaux Lee You … Wikipédia en Français

memento mori — [memɛ̃tomɔʀi] n. m. invar. ÉTYM. 1903; expression latine signifiant « souviens toi que tu es mortel ». ❖ ♦ Objet de piété, tête de mort (en ivoire, rongée par des serpents ou des vers), qui aide à se pénétrer de l idée de néant. || Des memento… … Encyclopédie Universelle

Memento mori — Me*men to mo ri [L.] Lit., remember to die, i.e., that you must die; a warning to be prepared for death; an object, as a death s head or a personal ornament, usually emblematic, used as a reminder of death. [Webster 1913 Suppl.] … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

Memento mori — С латинского: (мэмэнто мори) Помни о смерти. Выражение стало известно как формула приветствия, которым обменивались при встрече друг с другом монахи ордена траппистов, основанного в 1148 г. Его члены принимали на себя обет молчания, чтобы целиком … Словарь крылатых слов и выражений

memento mori — лат. (мэмэнто мори) помни о смерти. Толковый словарь иностранных слов Л. П. Крысина. М: Русский язык, 1998 … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

Memento mori — (lat.), Denk an den Tod! … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

Meménto mori — (lat., »Gedenke des Todes«), Wahlspruch einiger Mönchsorden, z. B. der Kamaldulenser … Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon

Memento mori — Memento mori, lat. = gedenke, daß du sterben mußt … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

memento mori — reminder of death, 1590s, Latin, lit. remember that you must die … Etymology dictionary

memento mori — ► NOUN (pl. same) ▪ an object kept as a reminder that death is inevitable. ORIGIN Latin, remember (that you have) to die … English terms dictionary

memento mori — [mə men′tō mōr′ē, mə men′tō mōr′ī] [L, remember that you must die] any reminder of death … English World dictionary

Источник

Что значит мементо мори

Мементо мори (Memento mori) можно дословно перевести как наставление никогда не забывать о смерти. Это латинское выражение быстро стало крылатой фразой, которая нередко встречается даже в настоящее время.

Историческая справка

Принято считать, что корни этого выражения растут еще из Древнего Рима. Именно тогда, во время победных шествий после разгрома врагов, за спиной командира армии ставили одного из рабов, который должен был регулярно напоминать гордому военачальнику о том, что он лишь человек. И несмотря на величие и завоеванные сокровища, он смертен, как и все остальные.

Позже выражение «Мементо мори» перебралось из зловещих предупреждений в одну из форм приветствия. Этими словами встречали друг друга монахи ордена отшельников. Они называли себя паулинами, в честь святого Павла – первого христианского монаха-отшельника.

Отражение в искусстве

Возможно, в тот непростой временной период людям необходимо было направить негативную энергию на что-то безобидное, например, мрачную, но при этом изысканную атрибутику смерти.

Почти два века спустя в моду вошли своеобразные траурные украшения, которые было принято использовать в знак траура по покойному родственнику или близкому другу.

В США крылатая фраза «Мементо мори» получила свою долю популярности благодаря пуританским влияниям. Пуритане, особенно в расцвет интереса к смерти в Европе, считали, что искусство – гиблое дело, и оно не приближает к Богу, а отдаляет от него. Они всячески избегали любого вмешательства в свою жизнь со стороны искусства, однако в их общине были разрешены портреты, считавшиеся историческими записями.

Известно, что один из известных протестантов Томас Смит не только отличился участием во многих морских сражениях, но также увлекался живописью. На своих картинах он нередко оставлял знаковые символы «Мементо мори», в частности, на автопортрете автора можно увидеть один из типичных символов смерти – череп.

Часто «Мементо мори» напрямую связывают с Днем мертвых в Мексике, ведь во время этого празднества можно увидеть различную атрибутику смерти. В том числе сладкие закуски, например, конфеты в форме черепов, или хлебцы, принявшие форму костей.

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как правильно пишется momento mori или memento mori, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как правильно пишется momento mori или memento mori», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

Содержание

- memento mori

- См. также в других словарях:

- momento mori

- См. также в других словарях:

- memento mori

- См. также в других словарях: