Русский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | прокрастина́ция | прокрастина́ции |

| Р. | прокрастина́ции | прокрастина́ций |

| Д. | прокрастина́ции | прокрастина́циям |

| В. | прокрастина́цию | прокрастина́ции |

| Тв. | прокрастина́цией прокрастина́циею |

прокрастина́циями |

| Пр. | прокрастина́ции | прокрастина́циях |

про—крас—ти—на́—ци·я

Существительное, неодушевлённое, женский род, 1-е склонение (тип склонения 7a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -прокрастин-; суффикс: -ациj; окончание: -я.

Произношение

- МФА: [prəkrəsʲtʲɪˈnat͡sɨɪ̯ə]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- неол. психол. отсрочка в принятии важных решений, отлынивание от обязательств, стремление отложить дела или неприятные мысли на потом ◆ А когда возникает конфликт между вашими внутренними страхами допустить ошибку или оказаться несовершенным и внешними требованиями других людей, вы начинаете искать спасения в прокрастинации. Нейл Фьоре, «Лёгкий способ перестать откладывать дела на потом» / перевод с англ. Ольги Терентьевой, 2013 г. ◆ — Прокрастинация. — Что это? — то когда постоянно откладываешь все дела на завтра. Бернар Вербер, «Зеркало Кассандры» / перевод с фр. К. Левиной, 2010 г. ◆ Если я застреваю в прокрастинации, то все, что мне нужно сделать — это включить определенную музыку, и из меня рекой хлынут идеи, уверенность и нужные слова. Бенжамин Харди, «Сила воли не работает: пусть твое окружение работает вместо нее» / перевод с англ. Э.Мельник, 2019 г.

Синонимы

- откладывание, отсрочивание, затягивание, отсрочка, синдром Скарлетт

Антонимы

Гиперонимы

- промедление

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология

Происходит от франц. procrastination, далее из лат. procrastinatio «откладывание, отсрочивание, затягивание» от лат. procrastinare «откладывать, отсрочивать, оттягивать» лат. pro «вперёд, для, за, вместо» + лат. crastinus «завтрашний», далее от лат. cras «завтра».

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

|

Библиография

- прокрастинация // Научно-информационный «Орфографический академический ресурс „Академос“» Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. orfo.ruslang.ru

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

«прокрастинация» — Фонетический и морфологический разбор слова, деление на слоги, подбор синонимов

Фонетический морфологический и лексический анализ слова «прокрастинация». Объяснение правил грамматики.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «прокрастинация» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «прокрастинация».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «прокрастинация» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «прокрастинация»

- 3 Ударение в слове «прокрастинация»

- 4 Фонетическая транскрипция слова «прокрастинация»

- 5 Фонетический разбор слова «прокрастинация» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

- 6 Предложения со словом «прокрастинация»

- 7 Значение слова «прокрастинация»

- 8 Как правильно пишется слово «прокрастинация»

Слоги в слове «прокрастинация» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 6

По слогам: про-кра-сти-на-ци-я

По правилам школьной программы слово «Прокрастинация» можно поделить на слоги разными способами. Допускается вариативность, то есть все варианты правильные. Например, такой:

прок-рас-ти-на-ци-я

По программе института слоги выделяются на основе восходящей звучности:

про-кра-сти-на-ци-я

Ниже перечислены виды слогов и объяснено деление с учётом программы института и школ с углублённым изучением русского языка.

к примыкает к этому слогу, а не к предыдущему, так как не является сонорной (непарной звонкой согласной)

с примыкает к этому слогу, а не к предыдущему, так как не является сонорной (непарной звонкой согласной)

Как перенести слово «прокрастинация»

про—крастинация

прок—растинация

прокра—стинация

прокрас—тинация

прокрасти—нация

прокрастина—ция

Ударение в слове «прокрастинация»

прокрастина́ция — ударение падает на 4-й слог

Фонетическая транскрипция слова «прокрастинация»

[пракраст’ин`ацый’а]

Фонетический разбор слова «прокрастинация» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

| Буква | Звук | Характеристики звука | Цвет |

|---|---|---|---|

| п | [п] | согласный, глухой парный, твёрдый, шумный | п |

| р | [р] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), твёрдый | р |

| о | [а] | гласный, безударный | о |

| к | [к] | согласный, глухой парный, твёрдый, шумный | к |

| р | [р] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), твёрдый | р |

| а | [а] | гласный, безударный | а |

| с | [с] | согласный, глухой парный, твёрдый, шумный | с |

| т | [т’] | согласный, глухой парный, мягкий, шумный | т |

| и | [и] | гласный, безударный | и |

| н | [н] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), твёрдый | н |

| а | [`а] | гласный, ударный | а |

| ц | [ц] | согласный, глухой непарный, твёрдый, шумный | ц |

| и | [ы] | гласный, безударный | и |

| я | [й’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий | я |

| [а] | гласный, безударный |

Число букв и звуков:

На основе сделанного разбора делаем вывод, что в слове 14 букв и 15 звуков.

Буквы: 6 гласных букв, 8 согласных букв.

Звуки: 6 гласных звуков, 9 согласных звуков.

Предложения со словом «прокрастинация»

Анализ помогает мне понять, в чём истинные причины прокрастинации – откладывания важных дел.

Наталья Самоукина, Живой театр тренинга. Технологии, упражнения, игры, сценарии, 2014.

Но большинство людей занимается прокрастинацией и выполняет тысячу неважных, но срочных дел вместо того, чтобы достигать своих главных целей.

Мария Хайнц, Позитивный тайм-менеджмент. Как успевать быть счастливым, 2014.

Со временем моя склонность к прокрастинации стала очевидной.

Брайан Солис, Жизнь на 100%, 2019.

Значение слова «прокрастинация»

Прокрастина́ция (от англ. procrastination — задержка, откладывание; от лат. procrastinatio — с тем же значением, восходит к лат. cras — завтра или лат. crastinus — завтрашний, и лат. pro — для, ради) — в психологии склонность к постоянному откладыванию даже важных и срочных дел, приводящая к жизненным проблемам и болезненным психологическим эффектам. (Википедия)

Как правильно пишется слово «прокрастинация»

Правописание слова «прокрастинация»

Орфография слова «прокрастинация»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «прокрастинация» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Distress is often linked to procrastination

Procrastination is the action of unnecessarily and voluntarily delaying or postponing something despite knowing that there will be negative consequences for doing so. The word has originated from the Latin word procrastinatus, which itself evolved from the prefix pro-, meaning «forward,» and crastinus, meaning «of tomorrow.»[1] Oftentimes, it is a habitual human behaviour.[2] It is a common human experience involving delay in everyday chores or even putting off salient tasks such as attending an appointment, submitting a job report or academic assignment, or broaching a stressful issue with a partner. Although typically perceived as a negative trait due to its hindering effect on one’s productivity often associated with depression, low self-esteem, guilt and inadequacy,[3] it can also be considered a wise response to certain demands that could present risky or negative outcomes or require waiting for new information to arrive.[4]

From a cultural and a social perspective, students from both Western and non-Western cultures are found to exhibit academic procrastination, but for different reasons. Students from Western cultures tend to procrastinate in order to avoid doing worse than they have done before or from failing to learn as much as they should have, whereas students from non-Western cultures tend to procrastinate in order to avoid looking incompetent, or to avoid demonstrating a lack of ability in front of their peers.[5] It is also important to consider how different cultural perspectives of time management can impact procrastination. For example, in cultures that have a multi-active view of time, people tend to place a higher value on making sure a job is done accurately before finishing. In cultures with a linear view of time, people tend to designate a certain amount of time on a task and stop once the allotted time has expired.[6]

A study of behavioral patterns of pigeons through delayed gratification suggests that procrastination is not unique to humans, but can also be observed in some other animals.[7] There are experiments finding clear evidence for «procrastination» among pigeons, which show that pigeons tend to choose a complex but delayed task rather than an easy but hurry-up one.[8]

Etymology[edit]

Latin: procrastinare, pro- (forward), with -crastinus, (until next day) from cras, (tomorrow).

Prevalence[edit]

In a study of academic procrastination from the University of Vermont, published in 1984, 46% of the subjects reported that they «always» or «nearly always» procrastinated writing papers, while approximately 30% reported procrastinating studying for exams and reading weekly assignments (by 28% and 30% respectively). Nearly a quarter of the subjects reported that procrastination was a problem for them regarding the same tasks. However, as many as 65% indicated that they would like to reduce their procrastination when writing papers, and approximately 62% indicated the same for studying for exams and 55% for reading weekly assignments.[9]

A 1992 study showed that «52% of surveyed students indicated having a moderate to high need for help concerning procrastination.»[10]

A study done in 2004 showed that 70% of university students categorized themselves as procrastinators while a 1984 study showed that 50% of the students would procrastinate consistently and considered it a major problem in their lives.[11]

In a study performed on university students, procrastination was shown to be greater with tasks that were perceived as unpleasant or as impositions than with tasks for which the student believed they lacked the required skills for accomplishing the task.[12]

Another point of relevance is that of procrastination in industry. A study from the State of the Art journal «The Impact of Organizational and Personal Factors on Procrastination in Employees of a Modern Russian Industrial Enterprise published in the Psychology in Russia», helped to identify the many factors that affected employees’ procrastination habits. Some of which include intensity of performance evaluations, importance of their duty within a company, and their perception and opinions on management and/or upper level decisions.[13]

Behavioral criteria of academic procrastination[edit]

Gregory Schraw, Theresa Wadkins, and Lori Olafson in 2007 proposed three criteria for a behavior to be classified as academic procrastination: it must be counterproductive, needless, and delaying.[14] Steel reviewed all previous attempts to define procrastination, and concluded in a 2007 study that procrastination is «to voluntarily delay an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay.»[15] Sabini and Silver argued that postponement and irrationality are the two key features of procrastination. Delaying a task is not deemed as procrastination, they argue, if there are rational reasons behind the delay.[16] Further, in a study conducted by Pogorskiy and Beckmann, learners’ procrastination is characterised by stable sequential patterns in learners’ web navigation behaviour.[17]

An approach that integrates several core theories of motivation as well as meta-analytic research on procrastination is the temporal motivation theory. It summarizes key predictors of procrastination (expectancy, value, and impulsiveness) into a mathematical equation.[15]

Psychological perspective[edit]

The pleasure principle may be responsible for procrastination; one may prefer to avoid negative emotions by delaying stressful tasks. In 2019, a research conducted by Rinaldi et al. indicated that measurable cognitive impairments may play a role in procrastination.[18] As the deadline for their target of procrastination grows closer, they are more stressed and may, thus, decide to procrastinate more to avoid this stress.[19] Some psychologists cite such behavior as a mechanism for coping with the anxiety associated with starting or completing any task or decision.[20]

Piers Steel indicated in 2010 that anxiety is just as likely to induce people to start working early as late, and that the focus of studies on procrastination should be impulsiveness. That is, anxiety will cause people to delay only if they are impulsive.[21][page needed]

Coping responses[edit]

Negative coping responses of procrastination tend to be avoidant or emotional rather than task-oriented or focused on problem-solving. Emotional and avoidant coping is employed to reduce stress (and cognitive dissonance) associated with delaying intended and important personal goals. This option provides immediate pleasure and is consequently very attractive to impulsive procrastinators, at the point of discovery of the achievable goals at hand.[22][23][page needed] There are several emotion-oriented strategies, similar to Freudian defense mechanisms, coping styles and self-handicapping.

Coping responses of procrastinators include the following:[citation needed]

- Avoidance: Avoiding the location or situation where the task takes place.

- Denial and trivialization: Pretending that procrastinatory behavior is not actually procrastinating, but rather a task which is more important than the avoided one, or that the essential task that should be done is not of immediate importance.

- Distraction: Engaging or immersing oneself in other behaviors or actions to prevent awareness of the task.

- Descending counterfactuality: Comparing consequences of one’s procrastinatory behavior with others’ worse situations.

- Valorisation: Pointing in satisfaction to what one achieved in the meantime while one should have been doing something else.

- Blaming: Delusional attributions to external factors, such as rationalizing that the procrastination is due to external forces beyond one’s control.

- Mocking: Using humor to validate one’s procrastination.

Task- or problem-solving measures are taxing from a procrastinator’s outlook. If such measures are pursued, it is less likely the procrastinator would remain a procrastinator. However, pursuing such measures requires actively changing one’s behavior or situation to prevent and minimize the re-occurrence of procrastination.

In 2006, it was suggested that neuroticism has no direct links to procrastination and that any relationship is fully mediated by conscientiousness.[24]

In 1982, it had been suggested that irrationality was an inherent feature of procrastination. «Putting things off even until the last moment isn’t procrastination if there is a reason to believe that they will take only that moment».[25] Steel et al. explained in 2001, «actions must be postponed and this postponement must represent poor, inadequate, or inefficient planning».[26]

Cultural perspective[edit]

According to Holly McGregor and Andrew Elliot (2002); Christopher Wolters (2003), academic procrastination among portions of undergraduate students has been correlated to «performance-avoidance orientation» which is one factor of the four factor model of achievement orientation.[5] Andrew Elliot and Judith Harackiewicz (1996) showed that students with performance-avoidance orientations tended to be concerned with comparisons to their peers. These students procrastinated as a result of not wanting to look incompetent, or to avoid demonstrating a lack of ability and adopt a facade of competence for a task in front of their peers.[5]

Gregory Arief Liem and Youyan Nie (2008) found that cultural characteristics are shown to have a direct influence on achievement orientation because it is closely aligned with most students’ cultural values and beliefs.[5] Sonja Dekker and Ronald Fischer’s (2008) meta-analysis across thirteen different societies revealed that students from Western cultures tend to be motivated more by «mastery-approach orientation» because the degree of incentive value for individual achievement is strongly reflective of the values of Western culture. By contrast, most students from Eastern cultures have been found to be «performance-avoidance orientated». They often make efforts to maintain a positive image of their abilities, which they display while in front of their peers.[5] In addition, Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama (1991) showed that in non-Western cultures, rather than standing out through their achievements, people tend to be motivated to become part of various interpersonal relationships and to fit in with those that are relevant to them.[5]

Research by Sushila Niles (1998) with Australian students and Sri Lankan students confirmed these differences, revealing that Australian students often pursued more individual goals, whereas Sri Lankan students usually desired more collaborative and social goals.[5] Multiple studies by Kuo-Shu Yang and An-Bang Yu (1987, 1988, 1990) have indicated that individual achievement among most Chinese and Japanese students were measured by a fulfillment of their obligation and responsibility to their family network, not to individual accomplishments.[5] Yang and Yu (1987) have also shown that collectivism and Confucianism are very strong motivators for achievement in many non-Western cultures because of their emphasis on cooperation in the family unit and community.[5] Guided by these cultural values, it is believed that the individual intuitively senses the degree of pressure that differentiates his or her factor of achievement orientation.[5]

Health perspective[edit]

To a certain degree it is normal to procrastinate and it can be regarded as a useful way to prioritize between tasks, due to a lower tendency of procrastination on truly valued tasks.[27] However, excessive procrastination can become a problem and impede normal functioning. When this happens, procrastination has been found to result in health problems, stress,[28] anxiety, a sense of guilt and crisis as well as loss of personal productivity and social disapproval for not meeting responsibilities or commitments. Together these feelings may promote further procrastination and for some individuals procrastination becomes almost chronic. Such procrastinators may have difficulties seeking support due to procrastination itself, but also social stigmas and the belief that task-aversion is caused by laziness, lack of willpower or low ambition. In some cases, problematic procrastination might be a sign of some underlying psychological disorder.[15]

Research on the physiological roots of procrastination have been concerned with the role of the prefrontal cortex,[29] the area of the brain that is responsible for executive brain functions such as impulse control, attention and planning. This is consistent with the notion that procrastination is strongly related to such functions, or a lack thereof. The prefrontal cortex also acts as a filter, decreasing distracting stimuli from other brain regions. Damage or low activation in this area can reduce one’s ability to avert diversions, which results in poorer organization, a loss of attention, and increased procrastination. This is similar to the prefrontal lobe’s role in ADHD, where it is commonly under-activated.[30]

In a 2014 U.S. study surveying procrastination and impulsiveness in fraternal and identical twin pairs, both traits were found to be «moderately heritable». The two traits were not separable at the genetic level (rgenetic = 1.0), meaning no unique genetic influences of either trait alone was found.[31] The authors confirmed three constructs developed from the evolutionary hypothesis that procrastination arose as a by-product of impulsivity: «(a) Procrastination is heritable, (b) the two traits share considerable genetic variation, and (c) goal-management ability is an important component of this shared variation.»[31]

Correlates[edit]

Procrastination has been linked to the complex arrangement of cognitive, affective and behavioral relationships from task desirability to low self esteem and anxiety to depression.[9] A study found that procrastinators were less future-oriented than their non-procrastinator counterparts. This result was hypothesized to be in association with hedonistic perspectives on the present; instead it was found procrastination was better predicted by a fatalistic and hopeless attitude towards life.[32]

A correlation between procrastination and eveningness was observed where individuals who had later sleeping and waking patterns were more likely to procrastinate.[33] It has been shown that Morningness increases across lifespan and procrastination decreases with age.,[15][34]

Perfectionism[edit]

Traditionally, procrastination has been associated with perfectionism: a tendency to negatively evaluate outcomes and one’s own performance, intense fear and avoidance of evaluation of one’s abilities by others, heightened social self-consciousness and anxiety, recurrent low mood, and «workaholism». However, adaptive perfectionists—egosyntonic perfectionism—were less likely to procrastinate than non-perfectionists, while maladaptive perfectionists, who saw their perfectionism as a problem—egodystonic perfectionism—had high levels of procrastination and anxiety.[35]

In a regression analysis study from 2007, it was found that mild to moderate perfectionists typically procrastinate slightly less than others, with «the exception being perfectionists who were also seeking clinical counseling».[15]

Academic[edit]

According to an Educational Science Professor, Hatice Odaci, academic procrastination is a significant problem during college years in part because many college students lack efficient time management skills in using the Internet. Also, Odaci notes that most colleges provide free and fast twenty-four-hour Internet service which some students are not usually accustomed to, and as a result of irresponsible use or lack of firewalls these students become engulfed in distractions, and thus in procrastination.[36]

Student syndrome is the phenomenon where a student will begin to fully apply themselves to a task only immediately before a deadline. This negates the usefulness of any buffers built into individual task duration estimates. Results from a 2002 study indicate that many students are aware of procrastination and accordingly set binding deadlines long before the date for which a task is due. These self-imposed binding deadlines are correlated with a better performance than without binding deadlines though performance is best for evenly spaced external binding deadlines. Finally, students have difficulties optimally setting self-imposed deadlines, with results suggesting a lack of spacing before the date at which results are due.[37]

In one experiment, participation in online exercises was found to be five times higher in the final week before a deadline than in the summed total of the first three weeks for which the exercises were available. Procrastinators end up being the ones doing most of the work in the final week before a deadline.[26] Additionally, students can delay making important decisions such as “I’ll get my degree out of the way first then worry about jobs and careers when I finish University”.[38]

Other reasons cited on why students procrastinate include fear of failure and success, perfectionist expectations, as well as legitimate activities that may take precedence over school work, such as a job.[39]

Procrastinators have been found to receive worse grades than non-procrastinators. Tice et al. (1997) report that more than one-third of the variation in final exam scores could be attributed to procrastination. The negative association between procrastination and academic performance is recurring and consistent. The students in the study not only received poor academic grades, but they also reported high levels of stress and poor self-health. Howell et al. (2006) found that, though scores on two widely used procrastination scales[9][40] were not significantly associated with the grade received for an assignment, self-report measures of procrastination on the assessment itself were negatively associated with grade.[41]

In 2005, a study conducted by Angela Chu and Jin Nam Choi and published in the Journal of Social Psychology intended to understand task performance among procrastinators with the definition of procrastination as the absence of self-regulated performance, from the 1977 work of Ellis & Knaus. In their study they identified two types of procrastination: the traditional procrastination which they denote as passive, and active procrastination where the person finds enjoyment of a goal-oriented activity only under pressure. The study calls this active procrastination positive procrastination, as it is a functioning state in a self-handicapping environment. In addition, it was observed that active procrastinators have more realistic perceptions of time and perceive more control over their time than passive procrastinators, which is considered a major differentiator between the two types. Due to this observation, active procrastinators are much more similar to non-procrastinators as they have a better sense of purpose in their time use and possess efficient time-structuring behaviors. But surprisingly, active and passive procrastinators showed similar levels of academic performance. The population of the study was college students and the majority of the sample size were women and Asian in origin. Comparisons with chronic pathological procrastination traits were avoided.[42]

Different findings emerge when observed and self-reported procrastination are compared. Steel et al. constructed their own scales based on Silver and Sabini’s «irrational» and «postponement» criteria. They also sought to measure this behavior objectively.[26] During a course, students could complete exam practice computer exercises at their own pace, and during the supervised class time could also complete chapter quizzes. A weighted average of the times at which each chapter quiz was finished formed the measure of observed procrastination, whilst observed irrationality was quantified with the number of practice exercises that were left uncompleted. Researchers found that there was only a moderate correlation between observed and self-reported procrastination (r = 0.35). There was a very strong inverse relationship between the number of exercises completed and the measure of postponement (r = −0.78). Observed procrastination was very strongly negatively correlated with course grade (r = −0.87), as was self-reported procrastination (though less so, r = −0.36). As such, self-reported measures of procrastination, on which the majority of the literature is based, may not be the most appropriate measure to use in all cases. It was also found that procrastination itself may not have contributed significantly to poorer grades. Steel et al. noted that those students who completed all of the practice exercises «tended to perform well on the final exam no matter how much they delayed.»

Procrastination is considerably more widespread in students than in the general population, with over 70 percent of students reporting procrastination for assignments at some point.[43] A 2014 panel study from Germany among several thousand university students found that increasing academic procrastination increases the frequency of seven different forms of academic misconduct, i.e., using fraudulent excuses, plagiarism, copying from someone else in exams, using forbidden means in exams, carrying forbidden means into exams, copying parts of homework from others, fabrication or falsification of data and the variety of academic misconduct. This study argues that academic misconduct can be seen as a means to cope with the negative consequences of academic procrastination such as performance impairment.[44]

Management[edit]

Psychologist William J. Knaus estimated that more than 90% of college students procrastinate.[45] Of these students, 25% are chronic procrastinators and typically abandon higher education (college dropouts).

Perfectionism is a prime cause for procrastination[46] because pursuing unattainable goals (perfection) usually results in failure. Unrealistic expectations destroy self-esteem and lead to self-repudiation, self-contempt, and widespread unhappiness. To overcome procrastination, it is essential to recognize and accept the power of failure without condemning,[47][better source needed] to stop focusing on faults and flaws and to set goals that are easier to achieve.

Behaviors and practices that reduce procrastination:[citation needed]

- Awareness of habits and thoughts that lead to procrastinating.

- Seeking help for self-defeating problems such as fear, anxiety, difficulty in concentrating, poor time management, indecisiveness, and perfectionism.[48]

- Fair evaluation of personal goals, strengths, weaknesses, and priorities.

- Realistic goals and personal positive links between the tasks and the concrete, meaningful goals.[49]

- Structuring and organization of daily activities.[49]

- Modification of one’s environment for that newly gained perspective: the elimination or minimization of noise or distraction; investing effort into relevant matters; and ceasing day-dreaming.[49]

- Disciplining oneself to set priorities.[49]

- Motivation with enjoyable activities, socializing and constructive hobbies.

- Approaching issues in small blocks of time, instead of attempting whole problems at once and risking intimidation.[48]

- To prevent relapse, reinforce pre-set goals based on needs and allow yourself to be rewarded in a balanced way for accomplished tasks.

Making a plan to complete tasks in a rigid schedule format might not work for everyone. There is no hard-and-fast rule to follow such a process if it turns out to be counter-productive. Instead of scheduling, it may be better to execute tasks in a flexible, unstructured schedule which has time slots for only necessary activities.[50]

Piers Steel suggests[51] that better time management is a key to overcoming procrastination, including being aware of and using one’s «power hours» (being a «morning person» or «night owl»). A good approach is to creatively utilize one’s internal circadian rhythms that are best suited for the most challenging and productive work. Steel states that it is essential to have realistic goals, to tackle one problem at a time and to cherish the «small successes». Brian O’Leary supports that «finding a work-life balance…may actually help us find ways to be more productive», suggesting that dedicating leisure activities as motivation can increase one’s efficiency at handling tasks.[52] Procrastination is not a lifelong trait. Those likely to worry can learn to let go, those who procrastinate can find different methods and strategies to help focus and avoid impulses.[53]

After contemplating his own procrastination habits, philosopher John Perry authored an essay entitled «Structured Procrastination»,[54] wherein he proposes a «cheat» method as a safer approach for tackling procrastination: using a pyramid scheme to reinforce the unpleasant tasks needed to be completed in a quasi-prioritized order.

Severe and negative impact[edit]

For some people, procrastination can be persistent and tremendously disruptive to everyday life. For these individuals, procrastination may reveal psychiatric disorders. Procrastination has been linked to a number of negative associations, such as depression, irrational behavior, low self-esteem, anxiety and neurological disorders such as ADHD. Others have found relationships with guilt[55] and stress.[28] Therefore, it is important for people whose procrastination has become chronic and is perceived to be debilitating to seek out a trained therapist or psychiatrist to investigate whether an underlying mental health issue may be present.[56]

With a distant deadline, procrastinators report significantly less stress and physical illness than do non-procrastinators. However, as the deadline approaches, this relationship is reversed. Procrastinators report more stress, more symptoms of physical illness, and more medical visits,[28] to the extent that, overall, procrastinators experience more stress and health problems. This can cause quality of life to decrease significantly along with overall happiness. Procrastination also has the ability to increase perfectionism and neuroticism, while decreasing conscientiousness and optimism.[11]

Procrastination can also lead to insomnia, Alisa Hrustic said in Men’s Health that «The procrastinators—people who scored above the median on the survey—were 1.5 to 3 times more likely to have symptoms of insomnia, like severe difficulty falling asleep, than those who scored lower on the test.»[57] Insomnia can even add more problems as a severe and negative impact.

See also[edit]

- Akrasia

- Attention economy

- Attention management

- Avoidance coping

- Avoidant personality disorder

- Bedtime procrastination

- Decision making

- Distraction

- Distributed practice

- Dunning–Kruger effect

- Egosyntonic and egodystonic

- Emotional self-regulation

- Empathy gap

- Hyperbolic discounting

- Law of triviality

- Laziness

- Life skills

- Passive-aggressive behavior

- Postponement of affect

- Precrastination

- Resistance (creativity)

- Restraint bias

- Tardiness (vice)

- Temporal motivation theory

- Time management

- Time perception

- Trait theory

- Work aversion

- Workaholism

- Writer’s block

- Zeigarnik effect

References[edit]

- ^ Karen K. Kirst-Ashman; Grafton H. Hull Jr. (2016). Empowerment Series: Generalist Practice with Organizations and Communities. Cengage Learning. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-305-94329-2.

- ^ Ferrari, Joseph (June 2018). «Delaying Disposing: Examining the Relationship between Procrastination and Clutter across Generations». Current Psychology. (New Brunswick, N.J.) (1046-1310), 37 (2) (2): 426–431. doi:10.1007/s12144-017-9679-4. S2CID 148862313.

- ^ Duru, Erdinç; Balkis, Murat (June 2017) [31 May 2017]. «Procrastination, Self-Esteem, Academic Performance, and Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model». International Journal of Educational Psychology. 6 (2): 97–119. doi:10.17583/ijep.2017.2584 – via ed.gov.

- ^ Bernstein, Peter (1996). Against the Gods: The remarkable story of risk. pp. 15. ISBN 9780471121046.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ganesan; et al. (2014). «Procrastination and the 2 x 2 achievement goal framework in Malaysian undergraduate students» (PDF). Psychology in the Schools. 51 (5): 506–516. doi:10.1002/pits.21760.[dead link]

- ^ Communications, Richard Lewis, Richard Lewis. «How Different Cultures Understand Time». Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ Mazur, James (1998). «Procrastination by Pigeons with Fixed-Interval Response Requirements». Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 69 (2): 185–197. doi:10.1901/jeab.1998.69-185. PMC 1284653. PMID 9540230.

- ^ Mazur, J E (January 1996). «Procrastination by pigeons: preference for larger, more delayed work requirements». Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 65 (1): 159–171. doi:10.1901/jeab.1996.65-159. ISSN 0022-5002. PMC 1350069. PMID 8583195.

- ^ a b c Solomon, LJ; Rothblum (1984). «Academic Procrastination: Frequency and Cognitive-Behavioural Correlates» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-07-29.

- ^ Gallagher, Robert P.; Golin, Anne; Kelleher, Kathleen (1992). «The Personal, Career, and Learning Skills Needs of College Students». Journal of College Student Development. 33 (4): 301–10.

- ^ a b Klingsieck, Katrin B. (January 2013). «Procrastination». European Psychologist. 18 (1): 24–34. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000138. ISSN 1016-9040.

- ^ Norman A. Milgram; Barry Sroloff; Michael Rosenbaum (June 1988). «The Procrastination of Everyday Life». Journal of Research in Personality. 22 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(88)90015-3.

- ^ Barabanshchikova, Valentina V.; Ivanova, Svetlana A.; Klimova, Oxana A. (2018). «The Impact of Organizational and Personal Factors on Procrastination in Employees of a Modern Russian Industrial Enterprise». Psychology in Russia: State of the Art. 11 (3): 69–85. doi:10.11621/pir.2018.0305.

- ^ Schraw, Gregory; Wadkins, Theresa; Olafson, Lori (2007). «Doing the Things We Do: A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination». Journal of Educational Psychology. 99: 12–25. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.12.

- ^ a b c d e Steel, Piers (2007). «The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 133 (1): 65–94. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.2796. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65. PMID 17201571. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-01.

- ^ Sabini, J.; Silver, M. (1982). Moralities of everyday life. p. 128.

- ^ Pogorskiy, Eduard; Beckmann, Jens F. (2022). «Learners’ web navigation behaviour beyond learning management systems: A way into addressing procrastination in online learning?». Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence. 3: 100094. doi:10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100094. S2CID 252131969.

- ^ Rinaldi, Anthony Robert; Roper, Carrie Lurie; Mehm, John (2019). «Procrastination as evidence of executive functioning impairment in college students». Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. 28 (6): 697–706. doi:10.1080/23279095.2019.1684293. ISSN 2327-9095. PMID 31679406. S2CID 207897153.

- ^ Pychyl, T. (20 February 2012). «The real reasons you procrastinate — and how to stop». The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Fiore, Neil A (2006). The Now Habit: A Strategic Program for Overcoming Procrastination and Enjoying Guilt-Free Play. New York: Penguin Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-58542-552-5.

- ^ Steel, Piers (2011). The procrastination equation: how to stop putting things off and start getting stuff done. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-170362-1. OCLC 754770758.

- ^ Gendler, Tamar Szabó (2007). «Self-Deception As Pretense». Philosophical Perspectives. 21: 231–58. doi:10.1111/j.1520-8583.2007.00127.x.

- ^ Gosling, J. (1990). Weakness of the Will. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Lee, Dong-gwi; Kelly, Kevin R.; Edwards, Jodie K. (2006). «A Closer Look at the Relationships Among Trait Procrastination, Neuroticism, and Conscientiousness». Personality and Individual Differences. 40: 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.010.

- ^ Sabini, J. & Silver, M. (1982) Moralities of everyday life, p. 128

- ^ a b c Steel, P.; Brothen, T.; Wambach, C. (2001). «Procrastination and Personality, Performance and Mood». Personality and Individual Differences. 30: 95–106. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00013-1.

- ^ Pavlina, Steve (2010-06-10). «How to Fall in Love with Procrastination». Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Tice, DM; Baumeister, RF (1997). «Longitudinal Study of Procrastination, Performance, Stress, and Health: The Costs and Benefits of Dawdling». Psychological Science. 8 (6): 454–58. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.461.1149. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00460.x. JSTOR 40063233. S2CID 15851848.

- ^ Evans, James R. (8 August 2007). Handbook of Neurofeedback: Dynamics and Clinical Applications. Psychology Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-7890-3360-4. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ Strub, RL (1989). «Frontal Lobe Syndrome in a Patient with Bilateral Globus Pallidus Lesions». Archives of Neurology. 46 (9): 1024–27. doi:10.1001/archneur.1989.00520450096027. PMID 2775008.

- ^ a b Gustavson, Daniel E; Miyake A; Hewitt JK; Friedman NP (4 April 2014). «Genetic Relations Among Procrastination, Impulsivity, and Goal-Management Ability Implications for the Evolutionary Origin of Procrastination». Psychological Science. 25 (6): 1178–88. doi:10.1177/0956797614526260. PMC 4185275. PMID 24705635.

- ^ Jackson, T.; Fritch, A.; Nagasaka, T.; Pope, L. (2003). «Procrastination and Perceptions of Past, Present, and Future». Individual Differences Research. 1: 17–28.

- ^ Digdon, Nancy; Howell, Andrew (2008-12-01). «College Students Who Have an Eveningness Preference Report Lower Self-Control and Greater Procrastination». Chronobiology International. 25 (6): 1029–46. doi:10.1080/07420520802553671. PMID 19005903. S2CID 32980851 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Duffy, JF; Czeisler, CA (2002). «Age-Related Change in the Relationship Between Circadian Period, Circadian Phase, and Diurnal Preference in Humans». Neuroscience Letters. 318 (3): 117–120. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02427-2. PMID 11803113. S2CID 43152568.

- ^ McGarvey, Jason A. (1996). «The Almost Perfect Definition». Archived from the original on 2006-03-13.

- ^ Odaci, Hatice (2011). «Academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination as predictors of problematic internet use in university students». Computers & Education. Elsevier BV. 57 (1): 1109–1113. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.005. ISSN 0360-1315.

- ^ Ariely, Dan; Wertenbroch, Klaus (2002). «Procrastination, Deadlines, and Performance: Self-Control by Precommitment» (PDF). Psychological Science. 13 (3): 219–224. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00441. PMID 12009041. S2CID 3025329. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-02-15.

- ^ «Procrastinating on your graduate job search? | Careers Perspectives from the University of Bath Careers Service».

- ^ «Procrastination». writingcenter.unc.edu. The Writing Center at UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ^ Tuckman, Bruce W. (1991). «The Development and Concurrent Validity of the Procrastination Scale». Educational and Psychological Measurement. SAGE Publications. 51 (2): 473–480. doi:10.1177/0013164491512022. ISSN 0013-1644. S2CID 145707625.

- ^ Howell, AJ; Watson, DC; Powell, RA; Buro, K (2006). «Academic Procrastination: The Pattern and Correlates of Behavioral Postponement». Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (8): 1519–30. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.023.

- ^ Hsin Chun Chu, Angela; Nam Choi, Jin (2005). «Rethinking Procrastination: Positive Effects of «Active» Procrastination Behavior on Attitudes and Performance». The Journal of Social Psychology. 145 (3): 245–64. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.502.2444. doi:10.3200/socp.145.3.245-264. PMID 15959999. S2CID 2705082.

- ^ «Getting Around to Procrastination». Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Patrzek, J.; Sattler, S.; van Veen, F.; Grunschel, C.; Fries, S. (2014). «Investigating the Effect of Academic Procrastination on the Frequency and Variety of Academic Misconduct: A Panel Study». Studies in Higher Education. 40 (6): 1–16. doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.854765. S2CID 144324180.

- ^ Ellis and Knaus, 1977

- ^ Hillary Rettig (2011). The 7 Secrets of the Prolific: The Definitive Guide to Overcoming Procrastination, Perfectionism, and Writer’s Block

- ^ James Prochaska, 1995

- ^ a b «How I Miraculously Overcame Procrastination By Applying These 6 Steps». Dating Reporter’s Blog. Retrieved 2021-02-27.

- ^ a b c d Macan, Therese Hoff (1994). «Time management: Test of a process model». Journal of Applied Psychology. 79 (3): 381–391. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.4283. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.381. ISSN 0021-9010.

- ^ Burka, J.; Yuen, L.M. (2007). Procrastination: Why You Do It, What to Do About It Now. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-7382-1130-5.

- ^ The Procrastination Equation, 2012

- ^ «Work-Life: Is Productivity in the Balance?». HBS Working Knowledge. 2004-07-05. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ^ «5 Ways to Finally Stop Procrastinating». Psychology Today. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ Perry, John (February 23, 1996). «How to Procrastinate and Still Get Things Done». The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Pychyl, TA; Lee, JM; Thibodeau, R; Blunt, A (2000). «Five Days of Emotion: An Experience Sampling Study of Undergraduate Student Procrastination (special issue)». Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 15: 239–254.

- ^ Lay, CH; Schouwenburg, HC (1993). «Trait procrastination, time management, and academic behavior». Trait Procrastination, Time Management, and Academic Behavior. 8 (4): 647–62.

- ^ Hrustic, Alisa (2016-07-13). «How Procrastination Literally Keeps You Up At Night». Men’s Health. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

Further reading[edit]

Procrastination[edit]

- We’re Sorry This Is Late … We Really Meant To Post It Sooner: Research Into Procrastination Shows Surprising Findings; Gregory Harris; ScienceDaily.com; Jan. 10, 2007 (their source)

- Why We Procrastinate And How To Stop; ScienceDaily.com; Jan. 12, 2009

- Perry, John (2012). The Art of Procrastination: A Guide to Effective Dawdling, Lollygagging and Postponing. New York: Workman. ISBN 978-0761171676

- Santella, Andrew (2018). Soon: An Overdue History of Procrastination, from Leonardo and Darwin to You and Me. Dey Street Books. ISBN 978-0062491596.

Impulse control[edit]

- Look Before You Leap: New Study Examines Self-Control; ScienceDaily.com; June 2, 2008

Motivation[edit]

- Steel, Piers; König, Cornelius J (2006). «Integrating Theories of Motivation» (PDF). Academy of Management Review. 31 (4): 889–913. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.196.3227. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.22527462. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-17.

External links[edit]

- CalPoly – Procrastination

Distress is often linked to procrastination

Procrastination is the action of unnecessarily and voluntarily delaying or postponing something despite knowing that there will be negative consequences for doing so. The word has originated from the Latin word procrastinatus, which itself evolved from the prefix pro-, meaning «forward,» and crastinus, meaning «of tomorrow.»[1] Oftentimes, it is a habitual human behaviour.[2] It is a common human experience involving delay in everyday chores or even putting off salient tasks such as attending an appointment, submitting a job report or academic assignment, or broaching a stressful issue with a partner. Although typically perceived as a negative trait due to its hindering effect on one’s productivity often associated with depression, low self-esteem, guilt and inadequacy,[3] it can also be considered a wise response to certain demands that could present risky or negative outcomes or require waiting for new information to arrive.[4]

From a cultural and a social perspective, students from both Western and non-Western cultures are found to exhibit academic procrastination, but for different reasons. Students from Western cultures tend to procrastinate in order to avoid doing worse than they have done before or from failing to learn as much as they should have, whereas students from non-Western cultures tend to procrastinate in order to avoid looking incompetent, or to avoid demonstrating a lack of ability in front of their peers.[5] It is also important to consider how different cultural perspectives of time management can impact procrastination. For example, in cultures that have a multi-active view of time, people tend to place a higher value on making sure a job is done accurately before finishing. In cultures with a linear view of time, people tend to designate a certain amount of time on a task and stop once the allotted time has expired.[6]

A study of behavioral patterns of pigeons through delayed gratification suggests that procrastination is not unique to humans, but can also be observed in some other animals.[7] There are experiments finding clear evidence for «procrastination» among pigeons, which show that pigeons tend to choose a complex but delayed task rather than an easy but hurry-up one.[8]

Etymology[edit]

Latin: procrastinare, pro- (forward), with -crastinus, (until next day) from cras, (tomorrow).

Prevalence[edit]

In a study of academic procrastination from the University of Vermont, published in 1984, 46% of the subjects reported that they «always» or «nearly always» procrastinated writing papers, while approximately 30% reported procrastinating studying for exams and reading weekly assignments (by 28% and 30% respectively). Nearly a quarter of the subjects reported that procrastination was a problem for them regarding the same tasks. However, as many as 65% indicated that they would like to reduce their procrastination when writing papers, and approximately 62% indicated the same for studying for exams and 55% for reading weekly assignments.[9]

A 1992 study showed that «52% of surveyed students indicated having a moderate to high need for help concerning procrastination.»[10]

A study done in 2004 showed that 70% of university students categorized themselves as procrastinators while a 1984 study showed that 50% of the students would procrastinate consistently and considered it a major problem in their lives.[11]

In a study performed on university students, procrastination was shown to be greater with tasks that were perceived as unpleasant or as impositions than with tasks for which the student believed they lacked the required skills for accomplishing the task.[12]

Another point of relevance is that of procrastination in industry. A study from the State of the Art journal «The Impact of Organizational and Personal Factors on Procrastination in Employees of a Modern Russian Industrial Enterprise published in the Psychology in Russia», helped to identify the many factors that affected employees’ procrastination habits. Some of which include intensity of performance evaluations, importance of their duty within a company, and their perception and opinions on management and/or upper level decisions.[13]

Behavioral criteria of academic procrastination[edit]

Gregory Schraw, Theresa Wadkins, and Lori Olafson in 2007 proposed three criteria for a behavior to be classified as academic procrastination: it must be counterproductive, needless, and delaying.[14] Steel reviewed all previous attempts to define procrastination, and concluded in a 2007 study that procrastination is «to voluntarily delay an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay.»[15] Sabini and Silver argued that postponement and irrationality are the two key features of procrastination. Delaying a task is not deemed as procrastination, they argue, if there are rational reasons behind the delay.[16] Further, in a study conducted by Pogorskiy and Beckmann, learners’ procrastination is characterised by stable sequential patterns in learners’ web navigation behaviour.[17]

An approach that integrates several core theories of motivation as well as meta-analytic research on procrastination is the temporal motivation theory. It summarizes key predictors of procrastination (expectancy, value, and impulsiveness) into a mathematical equation.[15]

Psychological perspective[edit]

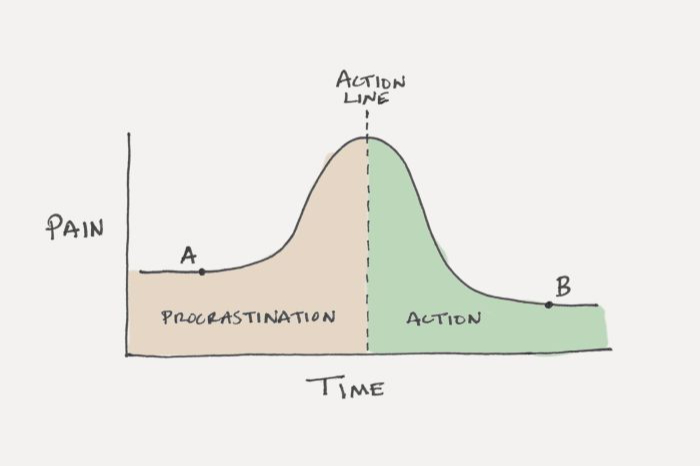

The pleasure principle may be responsible for procrastination; one may prefer to avoid negative emotions by delaying stressful tasks. In 2019, a research conducted by Rinaldi et al. indicated that measurable cognitive impairments may play a role in procrastination.[18] As the deadline for their target of procrastination grows closer, they are more stressed and may, thus, decide to procrastinate more to avoid this stress.[19] Some psychologists cite such behavior as a mechanism for coping with the anxiety associated with starting or completing any task or decision.[20]

Piers Steel indicated in 2010 that anxiety is just as likely to induce people to start working early as late, and that the focus of studies on procrastination should be impulsiveness. That is, anxiety will cause people to delay only if they are impulsive.[21][page needed]

Coping responses[edit]

Negative coping responses of procrastination tend to be avoidant or emotional rather than task-oriented or focused on problem-solving. Emotional and avoidant coping is employed to reduce stress (and cognitive dissonance) associated with delaying intended and important personal goals. This option provides immediate pleasure and is consequently very attractive to impulsive procrastinators, at the point of discovery of the achievable goals at hand.[22][23][page needed] There are several emotion-oriented strategies, similar to Freudian defense mechanisms, coping styles and self-handicapping.

Coping responses of procrastinators include the following:[citation needed]

- Avoidance: Avoiding the location or situation where the task takes place.

- Denial and trivialization: Pretending that procrastinatory behavior is not actually procrastinating, but rather a task which is more important than the avoided one, or that the essential task that should be done is not of immediate importance.

- Distraction: Engaging or immersing oneself in other behaviors or actions to prevent awareness of the task.

- Descending counterfactuality: Comparing consequences of one’s procrastinatory behavior with others’ worse situations.

- Valorisation: Pointing in satisfaction to what one achieved in the meantime while one should have been doing something else.

- Blaming: Delusional attributions to external factors, such as rationalizing that the procrastination is due to external forces beyond one’s control.

- Mocking: Using humor to validate one’s procrastination.

Task- or problem-solving measures are taxing from a procrastinator’s outlook. If such measures are pursued, it is less likely the procrastinator would remain a procrastinator. However, pursuing such measures requires actively changing one’s behavior or situation to prevent and minimize the re-occurrence of procrastination.

In 2006, it was suggested that neuroticism has no direct links to procrastination and that any relationship is fully mediated by conscientiousness.[24]

In 1982, it had been suggested that irrationality was an inherent feature of procrastination. «Putting things off even until the last moment isn’t procrastination if there is a reason to believe that they will take only that moment».[25] Steel et al. explained in 2001, «actions must be postponed and this postponement must represent poor, inadequate, or inefficient planning».[26]

Cultural perspective[edit]

According to Holly McGregor and Andrew Elliot (2002); Christopher Wolters (2003), academic procrastination among portions of undergraduate students has been correlated to «performance-avoidance orientation» which is one factor of the four factor model of achievement orientation.[5] Andrew Elliot and Judith Harackiewicz (1996) showed that students with performance-avoidance orientations tended to be concerned with comparisons to their peers. These students procrastinated as a result of not wanting to look incompetent, or to avoid demonstrating a lack of ability and adopt a facade of competence for a task in front of their peers.[5]

Gregory Arief Liem and Youyan Nie (2008) found that cultural characteristics are shown to have a direct influence on achievement orientation because it is closely aligned with most students’ cultural values and beliefs.[5] Sonja Dekker and Ronald Fischer’s (2008) meta-analysis across thirteen different societies revealed that students from Western cultures tend to be motivated more by «mastery-approach orientation» because the degree of incentive value for individual achievement is strongly reflective of the values of Western culture. By contrast, most students from Eastern cultures have been found to be «performance-avoidance orientated». They often make efforts to maintain a positive image of their abilities, which they display while in front of their peers.[5] In addition, Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama (1991) showed that in non-Western cultures, rather than standing out through their achievements, people tend to be motivated to become part of various interpersonal relationships and to fit in with those that are relevant to them.[5]

Research by Sushila Niles (1998) with Australian students and Sri Lankan students confirmed these differences, revealing that Australian students often pursued more individual goals, whereas Sri Lankan students usually desired more collaborative and social goals.[5] Multiple studies by Kuo-Shu Yang and An-Bang Yu (1987, 1988, 1990) have indicated that individual achievement among most Chinese and Japanese students were measured by a fulfillment of their obligation and responsibility to their family network, not to individual accomplishments.[5] Yang and Yu (1987) have also shown that collectivism and Confucianism are very strong motivators for achievement in many non-Western cultures because of their emphasis on cooperation in the family unit and community.[5] Guided by these cultural values, it is believed that the individual intuitively senses the degree of pressure that differentiates his or her factor of achievement orientation.[5]

Health perspective[edit]

To a certain degree it is normal to procrastinate and it can be regarded as a useful way to prioritize between tasks, due to a lower tendency of procrastination on truly valued tasks.[27] However, excessive procrastination can become a problem and impede normal functioning. When this happens, procrastination has been found to result in health problems, stress,[28] anxiety, a sense of guilt and crisis as well as loss of personal productivity and social disapproval for not meeting responsibilities or commitments. Together these feelings may promote further procrastination and for some individuals procrastination becomes almost chronic. Such procrastinators may have difficulties seeking support due to procrastination itself, but also social stigmas and the belief that task-aversion is caused by laziness, lack of willpower or low ambition. In some cases, problematic procrastination might be a sign of some underlying psychological disorder.[15]

Research on the physiological roots of procrastination have been concerned with the role of the prefrontal cortex,[29] the area of the brain that is responsible for executive brain functions such as impulse control, attention and planning. This is consistent with the notion that procrastination is strongly related to such functions, or a lack thereof. The prefrontal cortex also acts as a filter, decreasing distracting stimuli from other brain regions. Damage or low activation in this area can reduce one’s ability to avert diversions, which results in poorer organization, a loss of attention, and increased procrastination. This is similar to the prefrontal lobe’s role in ADHD, where it is commonly under-activated.[30]

In a 2014 U.S. study surveying procrastination and impulsiveness in fraternal and identical twin pairs, both traits were found to be «moderately heritable». The two traits were not separable at the genetic level (rgenetic = 1.0), meaning no unique genetic influences of either trait alone was found.[31] The authors confirmed three constructs developed from the evolutionary hypothesis that procrastination arose as a by-product of impulsivity: «(a) Procrastination is heritable, (b) the two traits share considerable genetic variation, and (c) goal-management ability is an important component of this shared variation.»[31]

Correlates[edit]

Procrastination has been linked to the complex arrangement of cognitive, affective and behavioral relationships from task desirability to low self esteem and anxiety to depression.[9] A study found that procrastinators were less future-oriented than their non-procrastinator counterparts. This result was hypothesized to be in association with hedonistic perspectives on the present; instead it was found procrastination was better predicted by a fatalistic and hopeless attitude towards life.[32]

A correlation between procrastination and eveningness was observed where individuals who had later sleeping and waking patterns were more likely to procrastinate.[33] It has been shown that Morningness increases across lifespan and procrastination decreases with age.,[15][34]

Perfectionism[edit]

Traditionally, procrastination has been associated with perfectionism: a tendency to negatively evaluate outcomes and one’s own performance, intense fear and avoidance of evaluation of one’s abilities by others, heightened social self-consciousness and anxiety, recurrent low mood, and «workaholism». However, adaptive perfectionists—egosyntonic perfectionism—were less likely to procrastinate than non-perfectionists, while maladaptive perfectionists, who saw their perfectionism as a problem—egodystonic perfectionism—had high levels of procrastination and anxiety.[35]

In a regression analysis study from 2007, it was found that mild to moderate perfectionists typically procrastinate slightly less than others, with «the exception being perfectionists who were also seeking clinical counseling».[15]

Academic[edit]

According to an Educational Science Professor, Hatice Odaci, academic procrastination is a significant problem during college years in part because many college students lack efficient time management skills in using the Internet. Also, Odaci notes that most colleges provide free and fast twenty-four-hour Internet service which some students are not usually accustomed to, and as a result of irresponsible use or lack of firewalls these students become engulfed in distractions, and thus in procrastination.[36]

Student syndrome is the phenomenon where a student will begin to fully apply themselves to a task only immediately before a deadline. This negates the usefulness of any buffers built into individual task duration estimates. Results from a 2002 study indicate that many students are aware of procrastination and accordingly set binding deadlines long before the date for which a task is due. These self-imposed binding deadlines are correlated with a better performance than without binding deadlines though performance is best for evenly spaced external binding deadlines. Finally, students have difficulties optimally setting self-imposed deadlines, with results suggesting a lack of spacing before the date at which results are due.[37]

In one experiment, participation in online exercises was found to be five times higher in the final week before a deadline than in the summed total of the first three weeks for which the exercises were available. Procrastinators end up being the ones doing most of the work in the final week before a deadline.[26] Additionally, students can delay making important decisions such as “I’ll get my degree out of the way first then worry about jobs and careers when I finish University”.[38]

Other reasons cited on why students procrastinate include fear of failure and success, perfectionist expectations, as well as legitimate activities that may take precedence over school work, such as a job.[39]

Procrastinators have been found to receive worse grades than non-procrastinators. Tice et al. (1997) report that more than one-third of the variation in final exam scores could be attributed to procrastination. The negative association between procrastination and academic performance is recurring and consistent. The students in the study not only received poor academic grades, but they also reported high levels of stress and poor self-health. Howell et al. (2006) found that, though scores on two widely used procrastination scales[9][40] were not significantly associated with the grade received for an assignment, self-report measures of procrastination on the assessment itself were negatively associated with grade.[41]

In 2005, a study conducted by Angela Chu and Jin Nam Choi and published in the Journal of Social Psychology intended to understand task performance among procrastinators with the definition of procrastination as the absence of self-regulated performance, from the 1977 work of Ellis & Knaus. In their study they identified two types of procrastination: the traditional procrastination which they denote as passive, and active procrastination where the person finds enjoyment of a goal-oriented activity only under pressure. The study calls this active procrastination positive procrastination, as it is a functioning state in a self-handicapping environment. In addition, it was observed that active procrastinators have more realistic perceptions of time and perceive more control over their time than passive procrastinators, which is considered a major differentiator between the two types. Due to this observation, active procrastinators are much more similar to non-procrastinators as they have a better sense of purpose in their time use and possess efficient time-structuring behaviors. But surprisingly, active and passive procrastinators showed similar levels of academic performance. The population of the study was college students and the majority of the sample size were women and Asian in origin. Comparisons with chronic pathological procrastination traits were avoided.[42]

Different findings emerge when observed and self-reported procrastination are compared. Steel et al. constructed their own scales based on Silver and Sabini’s «irrational» and «postponement» criteria. They also sought to measure this behavior objectively.[26] During a course, students could complete exam practice computer exercises at their own pace, and during the supervised class time could also complete chapter quizzes. A weighted average of the times at which each chapter quiz was finished formed the measure of observed procrastination, whilst observed irrationality was quantified with the number of practice exercises that were left uncompleted. Researchers found that there was only a moderate correlation between observed and self-reported procrastination (r = 0.35). There was a very strong inverse relationship between the number of exercises completed and the measure of postponement (r = −0.78). Observed procrastination was very strongly negatively correlated with course grade (r = −0.87), as was self-reported procrastination (though less so, r = −0.36). As such, self-reported measures of procrastination, on which the majority of the literature is based, may not be the most appropriate measure to use in all cases. It was also found that procrastination itself may not have contributed significantly to poorer grades. Steel et al. noted that those students who completed all of the practice exercises «tended to perform well on the final exam no matter how much they delayed.»

Procrastination is considerably more widespread in students than in the general population, with over 70 percent of students reporting procrastination for assignments at some point.[43] A 2014 panel study from Germany among several thousand university students found that increasing academic procrastination increases the frequency of seven different forms of academic misconduct, i.e., using fraudulent excuses, plagiarism, copying from someone else in exams, using forbidden means in exams, carrying forbidden means into exams, copying parts of homework from others, fabrication or falsification of data and the variety of academic misconduct. This study argues that academic misconduct can be seen as a means to cope with the negative consequences of academic procrastination such as performance impairment.[44]

Management[edit]

Psychologist William J. Knaus estimated that more than 90% of college students procrastinate.[45] Of these students, 25% are chronic procrastinators and typically abandon higher education (college dropouts).

Perfectionism is a prime cause for procrastination[46] because pursuing unattainable goals (perfection) usually results in failure. Unrealistic expectations destroy self-esteem and lead to self-repudiation, self-contempt, and widespread unhappiness. To overcome procrastination, it is essential to recognize and accept the power of failure without condemning,[47][better source needed] to stop focusing on faults and flaws and to set goals that are easier to achieve.

Behaviors and practices that reduce procrastination:[citation needed]

- Awareness of habits and thoughts that lead to procrastinating.

- Seeking help for self-defeating problems such as fear, anxiety, difficulty in concentrating, poor time management, indecisiveness, and perfectionism.[48]

- Fair evaluation of personal goals, strengths, weaknesses, and priorities.

- Realistic goals and personal positive links between the tasks and the concrete, meaningful goals.[49]

- Structuring and organization of daily activities.[49]

- Modification of one’s environment for that newly gained perspective: the elimination or minimization of noise or distraction; investing effort into relevant matters; and ceasing day-dreaming.[49]

- Disciplining oneself to set priorities.[49]

- Motivation with enjoyable activities, socializing and constructive hobbies.

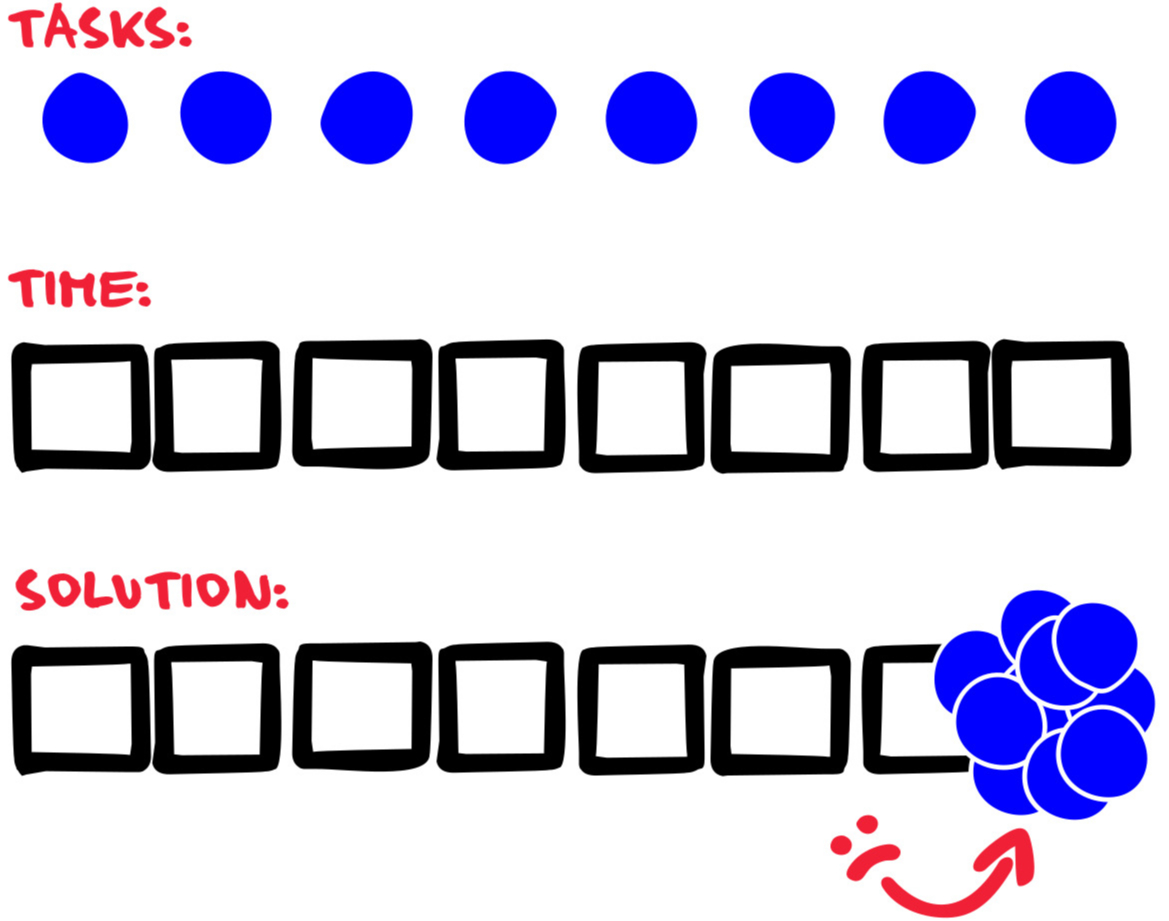

- Approaching issues in small blocks of time, instead of attempting whole problems at once and risking intimidation.[48]

- To prevent relapse, reinforce pre-set goals based on needs and allow yourself to be rewarded in a balanced way for accomplished tasks.

Making a plan to complete tasks in a rigid schedule format might not work for everyone. There is no hard-and-fast rule to follow such a process if it turns out to be counter-productive. Instead of scheduling, it may be better to execute tasks in a flexible, unstructured schedule which has time slots for only necessary activities.[50]

Piers Steel suggests[51] that better time management is a key to overcoming procrastination, including being aware of and using one’s «power hours» (being a «morning person» or «night owl»). A good approach is to creatively utilize one’s internal circadian rhythms that are best suited for the most challenging and productive work. Steel states that it is essential to have realistic goals, to tackle one problem at a time and to cherish the «small successes». Brian O’Leary supports that «finding a work-life balance…may actually help us find ways to be more productive», suggesting that dedicating leisure activities as motivation can increase one’s efficiency at handling tasks.[52] Procrastination is not a lifelong trait. Those likely to worry can learn to let go, those who procrastinate can find different methods and strategies to help focus and avoid impulses.[53]

After contemplating his own procrastination habits, philosopher John Perry authored an essay entitled «Structured Procrastination»,[54] wherein he proposes a «cheat» method as a safer approach for tackling procrastination: using a pyramid scheme to reinforce the unpleasant tasks needed to be completed in a quasi-prioritized order.

Severe and negative impact[edit]

For some people, procrastination can be persistent and tremendously disruptive to everyday life. For these individuals, procrastination may reveal psychiatric disorders. Procrastination has been linked to a number of negative associations, such as depression, irrational behavior, low self-esteem, anxiety and neurological disorders such as ADHD. Others have found relationships with guilt[55] and stress.[28] Therefore, it is important for people whose procrastination has become chronic and is perceived to be debilitating to seek out a trained therapist or psychiatrist to investigate whether an underlying mental health issue may be present.[56]

With a distant deadline, procrastinators report significantly less stress and physical illness than do non-procrastinators. However, as the deadline approaches, this relationship is reversed. Procrastinators report more stress, more symptoms of physical illness, and more medical visits,[28] to the extent that, overall, procrastinators experience more stress and health problems. This can cause quality of life to decrease significantly along with overall happiness. Procrastination also has the ability to increase perfectionism and neuroticism, while decreasing conscientiousness and optimism.[11]

Procrastination can also lead to insomnia, Alisa Hrustic said in Men’s Health that «The procrastinators—people who scored above the median on the survey—were 1.5 to 3 times more likely to have symptoms of insomnia, like severe difficulty falling asleep, than those who scored lower on the test.»[57] Insomnia can even add more problems as a severe and negative impact.

See also[edit]

- Akrasia

- Attention economy

- Attention management

- Avoidance coping

- Avoidant personality disorder

- Bedtime procrastination

- Decision making

- Distraction

- Distributed practice

- Dunning–Kruger effect

- Egosyntonic and egodystonic

- Emotional self-regulation

- Empathy gap

- Hyperbolic discounting

- Law of triviality

- Laziness

- Life skills

- Passive-aggressive behavior

- Postponement of affect

- Precrastination

- Resistance (creativity)

- Restraint bias

- Tardiness (vice)

- Temporal motivation theory

- Time management

- Time perception

- Trait theory

- Work aversion

- Workaholism

- Writer’s block

- Zeigarnik effect

References[edit]

- ^ Karen K. Kirst-Ashman; Grafton H. Hull Jr. (2016). Empowerment Series: Generalist Practice with Organizations and Communities. Cengage Learning. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-305-94329-2.

- ^ Ferrari, Joseph (June 2018). «Delaying Disposing: Examining the Relationship between Procrastination and Clutter across Generations». Current Psychology. (New Brunswick, N.J.) (1046-1310), 37 (2) (2): 426–431. doi:10.1007/s12144-017-9679-4. S2CID 148862313.

- ^ Duru, Erdinç; Balkis, Murat (June 2017) [31 May 2017]. «Procrastination, Self-Esteem, Academic Performance, and Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model». International Journal of Educational Psychology. 6 (2): 97–119. doi:10.17583/ijep.2017.2584 – via ed.gov.

- ^ Bernstein, Peter (1996). Against the Gods: The remarkable story of risk. pp. 15. ISBN 9780471121046.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ganesan; et al. (2014). «Procrastination and the 2 x 2 achievement goal framework in Malaysian undergraduate students» (PDF). Psychology in the Schools. 51 (5): 506–516. doi:10.1002/pits.21760.[dead link]

- ^ Communications, Richard Lewis, Richard Lewis. «How Different Cultures Understand Time». Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ Mazur, James (1998). «Procrastination by Pigeons with Fixed-Interval Response Requirements». Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 69 (2): 185–197. doi:10.1901/jeab.1998.69-185. PMC 1284653. PMID 9540230.

- ^ Mazur, J E (January 1996). «Procrastination by pigeons: preference for larger, more delayed work requirements». Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 65 (1): 159–171. doi:10.1901/jeab.1996.65-159. ISSN 0022-5002. PMC 1350069. PMID 8583195.

- ^ a b c Solomon, LJ; Rothblum (1984). «Academic Procrastination: Frequency and Cognitive-Behavioural Correlates» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-07-29.

- ^ Gallagher, Robert P.; Golin, Anne; Kelleher, Kathleen (1992). «The Personal, Career, and Learning Skills Needs of College Students». Journal of College Student Development. 33 (4): 301–10.

- ^ a b Klingsieck, Katrin B. (January 2013). «Procrastination». European Psychologist. 18 (1): 24–34. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000138. ISSN 1016-9040.

- ^ Norman A. Milgram; Barry Sroloff; Michael Rosenbaum (June 1988). «The Procrastination of Everyday Life». Journal of Research in Personality. 22 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(88)90015-3.

- ^ Barabanshchikova, Valentina V.; Ivanova, Svetlana A.; Klimova, Oxana A. (2018). «The Impact of Organizational and Personal Factors on Procrastination in Employees of a Modern Russian Industrial Enterprise». Psychology in Russia: State of the Art. 11 (3): 69–85. doi:10.11621/pir.2018.0305.

- ^ Schraw, Gregory; Wadkins, Theresa; Olafson, Lori (2007). «Doing the Things We Do: A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination». Journal of Educational Psychology. 99: 12–25. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.12.

- ^ a b c d e Steel, Piers (2007). «The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 133 (1): 65–94. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.2796. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65. PMID 17201571. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-01.

- ^ Sabini, J.; Silver, M. (1982). Moralities of everyday life. p. 128.

- ^ Pogorskiy, Eduard; Beckmann, Jens F. (2022). «Learners’ web navigation behaviour beyond learning management systems: A way into addressing procrastination in online learning?». Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence. 3: 100094. doi:10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100094. S2CID 252131969.

- ^ Rinaldi, Anthony Robert; Roper, Carrie Lurie; Mehm, John (2019). «Procrastination as evidence of executive functioning impairment in college students». Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. 28 (6): 697–706. doi:10.1080/23279095.2019.1684293. ISSN 2327-9095. PMID 31679406. S2CID 207897153.

- ^ Pychyl, T. (20 February 2012). «The real reasons you procrastinate — and how to stop». The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Fiore, Neil A (2006). The Now Habit: A Strategic Program for Overcoming Procrastination and Enjoying Guilt-Free Play. New York: Penguin Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-58542-552-5.

- ^ Steel, Piers (2011). The procrastination equation: how to stop putting things off and start getting stuff done. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-170362-1. OCLC 754770758.

- ^ Gendler, Tamar Szabó (2007). «Self-Deception As Pretense». Philosophical Perspectives. 21: 231–58. doi:10.1111/j.1520-8583.2007.00127.x.

- ^ Gosling, J. (1990). Weakness of the Will. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Lee, Dong-gwi; Kelly, Kevin R.; Edwards, Jodie K. (2006). «A Closer Look at the Relationships Among Trait Procrastination, Neuroticism, and Conscientiousness». Personality and Individual Differences. 40: 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.010.