«Qazaqstan» redirects here. For the Kazakh state television broadcaster, see Qazaqstan (channel).

|

Republic of Kazakhstan

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem |

|

| Anthem: Менің Қазақстаным (Kazakh) Menıñ Qazaqstanym «My Kazakhstan» |

|

|

|

| Capital | Astana 51°10′N 71°26′E / 51.167°N 71.433°E |

| Largest city | Almaty 43°16′39″N 76°53′45″E / 43.27750°N 76.89583°E |

| Official languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2021)[1] |

|

| Religion

(2021)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Kazakhstani[a] |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic |

|

• President |

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev |

|

• Prime Minister |

Älihan Smaiylov |

| Legislature | Parliament |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

Majilis |

| Formation | |

|

• Kazakh Khanate |

1465 |

|

• Alash Autonomy |

13 December 1917 |

|

• Kirghiz ASSR |

26 August 1920 |

|

• Kazakh ASSR |

19 June 1925 |

|

• Kazakh SSR |

5 December 1936 |

|

• Declaration of sovereignty |

25 October 1990 |

|

• Reconstituted as the Republic of Kazakhstan |

10 December 1991 |

|

• Independence from USSR |

16 December 1991 |

|

• Recognised |

26 December 1991 |

|

• Current constitution |

30 August 1995 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

2,724,900 km2 (1,052,100 sq mi) (9th) |

|

• Water (%) |

1.7 |

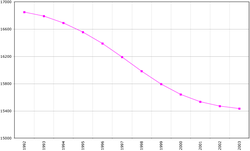

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

19,398,331[3] (64th) |

|

• Density |

7/km2 (18.1/sq mi) (236th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 56th |

| Currency | Tenge (₸) (KZT) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 / +6 (West / East) |

| Date format | yyyy.dd.mm[b] |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +997 (+7-6xx, +7-7xx will operate in tandem with +997 until 2025.) |

| ISO 3166 code | KZ |

| Internet TLD |

|

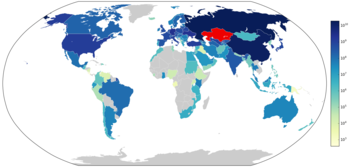

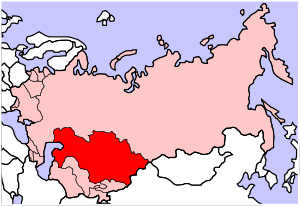

Kazakhstan,[c] officially the Republic of Kazakhstan,[d] is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe.[e] It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbekistan to the south, and Turkmenistan to the southwest, with a coastline along the Caspian Sea. Its capital is Astana, known as Nur-Sultan from 2019 to 2022. Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, was the country’s capital until 1997. Kazakhstan is the world’s largest landlocked country, the largest and northernmost Muslim-majority country by land area, and the ninth-largest country in the world. It has a population of 19 million people, and one of the lowest population densities in the world, at fewer than 6 people per square kilometre (15 people per square mile).

The country dominates Central Asia economically and politically, generating 60 percent of the region’s GDP, primarily through its oil and gas industry; it also has vast mineral resources.[9] Officially, it is a democratic, secular, unitary, constitutional republic with a diverse cultural heritage,[10] and has the highest Human Development Index ranking in the region. Kazakhstan is a member state of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Eurasian Economic Union, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the Organization of Turkic States, and the International Organization of Turkic Culture.

The territory of Kazakhstan has historically been inhabited by nomadic groups and empires. In antiquity, the ancient Iranian nomadic Scythians inhabited the land, and the Achaemenid Persian Empire expanded towards the southern territory of the modern country. Turkic nomads, who trace their ancestry to many Turkic states such as the First Turkic Khaganate and the Second Turkic Khaganate, have inhabited the country from as early as the 6th century. In the 13th century, the territory was subjugated by the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan. In the 15th century, as a result of disintegration of Golden Horde, the Kazakh Khanate was established on much of the lands that would later form the territory of modern Kazakhstan.

By the 18th century, Kazakh Khanate disintegrated into three jüz which were absorbed and conquered by the Russian Empire; by the mid-19th century, the Russians nominally ruled all of Kazakhstan as part of the Russian Empire and liberated all of the slaves that the Kazakhs had captured in 1859.[11] Following the 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent outbreak of the Russian Civil War, the territory of Kazakhstan was reorganized several times. In 1936, it was established as the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic within the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan was the last of the Soviet republics to declare independence during the dissolution of the Soviet Union from 1988 to 1991. Human rights organizations have described the Kazakh government as authoritarian, and regularly describe Kazakhstan’s human rights situation as poor.

Etymology

The English word Kazakh, meaning a member of the Kazakh people, derives from Russian: казах.[12] The native name is Kazakh: қазақ, romanized: qazaq. It might originate from the Turkic word verb qaz-, ‘to wander’, reflecting the Kazakhs’ nomadic culture.[13] The term ‘Cossack’ is of the same origin.[13] The Persian suffix -stan means «land» or «place of», so Kazakhstan (Kazakh: Қазақстан, romanized: Qazaqstan) can be literally translated as «land of the wanderers».

In Turko-Persian sources, the term Özbek-Qazaq first appeared during the middle of the 16th century, in the Tarikh-i-Rashidi by Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a Chagatayid prince of Kashmir. In this manuscript, the author locates Kazakh in the eastern part of Desht-i Qipchaq.[14] According to Vasily Bartold, the Kazakhs likely began using that name during the 15th century.[15]

Though Kazakh traditionally referred only to ethnic Kazakhs, including those living in China, Russia, Turkey, Uzbekistan and other neighbouring countries, the term is increasingly being used to refer to any inhabitant of Kazakhstan, including residents of other ethnicities.[16]

History

Approximate extent of Scythia in the 1st century BC

Kazakhstan has been inhabited since the Paleolithic era.[17] The Botai culture (3700–3100 BC) is credited with the first domestication of horses. The Botai population derived most of their ancestry from a deeply European-related population known as Ancient North Eurasians, while also displaying some Ancient East Asian admixture.[18] Pastoralism developed during the Neolithic, as the region’s climate and terrain are best suited to a nomadic lifestyle. The population was Caucasoid during the Bronze and Iron Age period.[19][20]

The Kazakh territory was a key constituent of the Eurasian trading Steppe Route, the ancestor of the terrestrial Silk Roads. Archaeologists believe that humans first domesticated the horse (i.e., ponies) in the region’s vast steppes. During recent prehistoric times, Central Asia was inhabited by groups such as the possibly Indo-European Afanasievo culture,[21] later early Indo-Iranian cultures such as Andronovo,[22] and later Indo-Iranians such as the Saka and Massagetae.[23][24] Other groups included the nomadic Scythians and the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the southern territory of the modern country. The Andronovo and Srubnaya cultures, precursors to the peoples of the Scythian cultures, were found to harbor mixed ancestry from the Yamnaya Steppe herders and peoples of the Central European Middle Neolithic.[25]

In 329 BC, Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army fought in the Battle of Jaxartes against the Scythians along the Jaxartes River, now known as the Syr Darya along the southern border of modern Kazakhstan.

Cuman-Kipchak and Golden Horde

The main migration of Turkic peoples occurred between the 5th and 11th centuries when they spread across most of Central Asia. The Turkic peoples slowly replaced and assimilated the previous Iranian-speaking locals, turning the population of Central Asia from largely Iranian, into primarily of East Asian descent.[26]

The first Turkic Khaganate was founded by Bumin in 552 on the Mongolian Plateau and quickly spread west toward the Caspian Sea. The Göktürks drove before them various peoples: Xionites, Uar, Oghurs and others. These seem to have merged into the Avars and Bulgars. Within 35 years the eastern half and the Western Turkic Khaganate were independent. The Western Khaganate reached its peak in the early 7th century.

The Cumans entered the steppes of modern-day Kazakhstan around the early 11th century, where they later joined with the Kipchak and established the vast Cuman-Kipchak confederation. While ancient cities Taraz (Aulie-Ata) and Hazrat-e Turkestan had long served as important way-stations along the Silk Road connecting Asia and Europe, true political consolidation began only with the Mongol rule of the early 13th century. Under the Mongol Empire, the first strictly structured administrative districts (Ulus) were established. After the division of the Mongol Empire in 1259, the land that would become modern-day Kazakhstan was ruled by the Golden Horde, also known as the Ulus of Jochi. During the Golden Horde period, a Turco-Mongol tradition emerged among the ruling elite wherein Turkicised descendants of Genghis Khan followed Islam and continued to reign over the lands.

Kazakh Khanate

In 1465, the Kazakh Khanate emerged as a result of the dissolution of the Golden Horde. Established by Janibek Khan and Kerei Khan, it continued to be ruled by the Turco-Mongol clan of Tore (Jochid dynasty).

Throughout this period, traditional nomadic life and a livestock-based economy continued to dominate the steppe. In the 15th century, a distinct Kazakh identity began to emerge among the Turkic tribes. This was followed by the Kazakh War of Independence, where the Khanate gained its sovereignty from the Shaybanids. The process was consolidated by the mid-16th century with the appearance of the Kazakh language, culture, and economy.

Approximate areas occupied by the three Kazakh jüz in the early 20th century.

Nevertheless, the region was the focus of ever-increasing disputes between the native Kazakh emirs and the neighbouring Persian-speaking peoples to the south. At its height, the Khanate would rule parts of Central Asia and control Cumania. The Kazakh Khanate’s territories would expand deep into Central Asia. By the early 17th century, the Kazakh Khanate was struggling with the impact of tribal rivalries, which had effectively divided the population into the Great, Middle and Little (or Small) hordes (jüz). Political disunion, tribal rivalries, and the diminishing importance of overland trade routes between east and west weakened the Kazakh Khanate. The Khiva Khanate used this opportunity and annexed the Mangyshlak Peninsula. Uzbek rule there lasted two centuries until the Russian arrival.

During the 17th century, the Kazakhs fought the Oirats, a federation of western Mongol tribes, including the Dzungar.[27] The beginning of the 18th century marked the zenith of the Kazakh Khanate. During this period the Little Horde participated in the 1723–1730 war against the Dzungar Khanate, following their «Great Disaster» invasion of Kazakh territory. Under the leadership of Abul Khair Khan, the Kazakhs won major victories over the Dzungar at the Bulanty River in 1726 and at the Battle of Añyraqai in 1729.[28]

Ablai Khan participated in the most significant battles against the Dzungar from the 1720s to the 1750s, for which he was declared a «batyr» («hero») by the people. The Kazakhs suffered from the frequent raids against them by the Volga Kalmyks. The Kokand Khanate used the weakness of Kazakh jüzs after Dzungar and Kalmyk raids and conquered present Southeastern Kazakhstan, including Almaty, the formal capital in the first quarter of the 19th century. Also, the Emirate of Bukhara ruled Shymkent before the Russians gained dominance.[29]

Russian Kazakhstan

Map of the Kazakh Territory in 1903

Kazakh woman in wedding clothes, 19th century

In the first half of the 18th century, the Russian Empire constructed the Irtysh line, a series of forty-six forts and ninety-six redoubts, including Omsk (1716), Semipalatinsk (1718), Pavlodar (1720), Orenburg (1743) and Petropavlovsk (1752),[30] to prevent Kazakh and Oirat raids into Russian territory.[31] In the late 18th century the Kazakhs took advantage of Pugachev’s Rebellion, which was centred on the Volga area, to raid Russian and Volga German settlements.[citation needed] In the 19th century, the Russian Empire began to expand its influence into Central Asia. The «Great Game» period is generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. The tsars effectively ruled over most of the territory belonging to what is now the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The Russian Empire introduced a system of administration and built military garrisons and barracks in its effort to establish a presence in Central Asia in the so-called «Great Game» for dominance in the area against the British Empire, which was extending its influence from the south in India and Southeast Asia. Russia built its first outpost, Orsk, in 1735. Russia introduced the Russian language in all schools and governmental organisations.

Russia’s efforts to impose its system aroused the resentment of the Kazakh people, and, by the 1860s, some Kazakhs resisted its rule. Russia had disrupted the traditional nomadic lifestyle and livestock-based economy, and people were suffering from hunger and starvation, with some Kazakh tribes being decimated. The Kazakh national movement, which began in the late 19th century, sought to preserve the native language and identity by resisting the attempts of the Russian Empire to assimilate and stifle Kazakh culture.

From the 1890s onward, ever-larger numbers of settlers from the Russian Empire began colonizing the territory of present-day Kazakhstan, in particular, the province of Semirechye. The number of settlers rose still further once the Trans-Aral Railway from Orenburg to Tashkent was completed in 1906. A specially created Migration Department (Переселенческое Управление) in St. Petersburg oversaw and encouraged the migration to expand Russian influence in the area. During the 19th century, about 400,000 Russians immigrated to Kazakhstan, and about one million Slavs, Germans, Jews, and others immigrated to the region during the first third of the 20th century.[32] Vasile Balabanov was the administrator responsible for the resettlement during much of this time.

The competition for land and water that ensued between the Kazakhs and the newcomers caused great resentment against colonial rule during the final years of the Russian Empire. The most serious uprising, the Central Asian revolt, occurred in 1916. The Kazakhs attacked Russian and Cossack settlers and military garrisons. The revolt resulted in a series of clashes and in brutal massacres committed by both sides.[33] Both sides resisted the communist government until late 1919.

Kazakh SSR

Stanitsa Sofiiskaya, Talgar. 1920s

Following the collapse of central government in Petrograd in November 1917, the Kazakhs (then in Russia officially referred to as «Kirghiz») experienced a brief period of autonomy (the Alash Autonomy) before eventually succumbing to the Bolsheviks′ rule. On 26 August 1920, the Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) was established. The Kirghiz ASSR included the territory of present-day Kazakhstan, but its administrative centre was the mainly Russian-populated town of Orenburg. In June 1925, the Kirghiz ASSR was renamed the Kazak ASSR and its administrative centre was transferred to the town of Kyzylorda, and in April 1927 to Alma-Ata.

Soviet repression of the traditional elite, along with forced collectivisation in the late 1920s and 1930s, brought famine and high fatalities, leading to unrest (see also: Famine in Kazakhstan of 1932–33).[34][35] During the 1930s, some members of the Kazakh intelligentsia were executed – as part of the policies of political reprisals pursued by the Soviet government in Moscow.

On 5 December 1936, the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (whose territory by then corresponded to that of modern Kazakhstan) was detached from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and made the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, a full union republic of the USSR, one of eleven such republics at the time, along with the Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic.

The republic was one of the destinations for exiled and convicted persons, as well as for mass resettlements, or deportations affected by the central USSR authorities during the 1930s and 1940s, such as approximately 400,000 Volga Germans deported from the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in September–October 1941, and then later the Greeks and Crimean Tatars. Deportees and prisoners were interned in some of the biggest Soviet labour camps (the Gulag), including ALZhIR camp outside Astana, which was reserved for the wives of men considered «enemies of the people».[36] Many moved due to the policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union and others were forced into involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet-German War (1941–1945) led to an increase in industrialisation and mineral extraction in support of the war effort. At the time of Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, however, Kazakhstan still had an overwhelmingly agricultural economy. In 1953, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev initiated the Virgin Lands Campaign designed to turn the traditional pasturelands of Kazakhstan into a major grain-producing region for the Soviet Union. The Virgin Lands policy brought mixed results. However, along with later modernisations under Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev (in power 1964–1982), it accelerated the development of the agricultural sector, which remains the source of livelihood for a large percentage of Kazakhstan’s population. Because of the decades of privation, war and resettlement, by 1959 the Kazakhs had become a minority in the country, making up 30 percent of the population. Ethnic Russians accounted for 43 percent.[37]

In 1947, the USSR government, as part of its atomic bomb project, founded an atomic bomb test site near the north-eastern town of Semipalatinsk, where the first Soviet nuclear bomb test was conducted in 1949. Hundreds of nuclear tests were conducted until 1989 with adverse consequences for the nation’s environment and population.[38] The Anti-nuclear movement in Kazakhstan became a major political force in the late 1980s.

In December 1986, mass demonstrations by young ethnic Kazakhs, later called the Jeltoqsan riot, took place in Almaty to protest the replacement of the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR Dinmukhamed Konayev with Gennady Kolbin from the Russian SFSR. Governmental troops suppressed the unrest, several people were killed, and many demonstrators were jailed.[39] In the waning days of Soviet rule, discontent continued to grow and found expression under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost («openness»).

Independence

The Monument of Independence, Republic Square, Almaty

On 25 October 1990, Kazakhstan declared its sovereignty on its territory as a republic within the Soviet Union. Following the August 1991 aborted coup attempt in Moscow, Kazakhstan declared independence on 16 December 1991, thus becoming the last Soviet republic to declare independence. Ten days later, the Soviet Union itself ceased to exist.

Kazakhstan’s communist-era leader, Nursultan Nazarbayev, became the country’s first President. Nazarbayev ruled in an authoritarian manner. An emphasis was placed on converting the country’s economy to a market economy while political reforms lagged behind economic advances. By 2006, Kazakhstan was generating 60 percent of the GDP of Central Asia, primarily through its oil industry.[9]

In 1997, the government moved the capital to Astana, renamed Nur-Sultan on 23 March 2019,[40] from Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, where it had been established under the Soviet Union.[41]

In March 2019, Nazarbayev resigned 29 years after taking office. However, he continued to lead the influential security council and held the formal title Leader of the Nation.[42] Kassym-Jomart Tokayev succeeded Nazarbayev as the President of Kazakhstan. His first official act was to rename the capital after his predecessor.[43] In June 2019, the new president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, won Kazakhstan’s presidential election.[44]

In January 2022, the country plunged into political unrest following a spike in fuel prices.[45] In consequence, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev took over as head of the powerful Security Council, removing his predecessor Nursultan Nazarbayev from the post.[46] In September 2022, the name of the country’s capital was changed back to Astana from Nur-Sultan.[47]

Geography

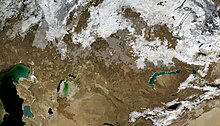

Satellite image of Kazakhstan (November 2004)

As it extends across both sides of the Ural River, considered the dividing line separating Europe and Asia, Kazakhstan is one of only two landlocked countries in the world that has territory in two continents (the other is Azerbaijan).

With an area of 2,700,000 square kilometres (1,000,000 sq mi) – equivalent in size to Western Europe – Kazakhstan is the ninth-largest country and largest landlocked country in the world. While it was part of the Russian Empire, Kazakhstan lost some of its territory to China’s Xinjiang province,[48] and some to Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan autonomous republic during Soviet years.

It shares borders of 6,846 kilometres (4,254 mi) with Russia, 2,203 kilometres (1,369 mi) with Uzbekistan, 1,533 kilometres (953 mi) with China, 1,051 kilometres (653 mi) with Kyrgyzstan, and 379 kilometres (235 mi) with Turkmenistan. Major cities include Astana, Almaty, Karagandy, Shymkent, Atyrau, and Oskemen. It lies between latitudes 40° and 56° N, and longitudes 46° and 88° E. While located primarily in Asia, a small portion of Kazakhstan is also located west of the Urals in Eastern Europe.[49]

Kazakhstan’s terrain extends west to east from the Caspian Sea to the Altay Mountains and north to south from the plains of Western Siberia to the oases and deserts of Central Asia. The Kazakh Steppe (plain), with an area of around 804,500 square kilometres (310,600 sq mi), occupies one-third of the country and is the world’s largest dry steppe region. The steppe is characterised by large areas of grasslands and sandy regions. Major seas, lakes and rivers include Lake Balkhash, Lake Zaysan, the Charyn River and gorge, the Ili, Irtysh, Ishim, Ural and Syr Darya rivers, and the Aral Sea until it largely dried up in one of the world’s worst environmental disasters.[50]

The Charyn Canyon is 80 kilometres (50 mi) long, cutting through a red sandstone plateau and stretching along the Charyn River gorge in northern Tian Shan («Heavenly Mountains», 200 km (124 mi) east of Almaty) at 43°21′1.16″N 79°4′49.28″E / 43.3503222°N 79.0803556°E. The steep canyon slopes, columns and arches rise to heights of between 150 and 300 metres (490 and 980 feet). The inaccessibility of the canyon provided a safe haven for a rare ash tree, Fraxinus sogdiana, which survived the Ice Age there and has now also grown in some other areas.[citation needed] Bigach crater, at 48°30′N 82°00′E / 48.500°N 82.000°E, is a Pliocene or Miocene asteroid impact crater, 8 km (5 mi) in diameter and estimated to be 5±3 million years old.

Kazakhstan’s Almaty region is also home to the Mynzhylky mountain plateau.

Natural resources

Kazakhstan has an abundant supply of accessible mineral and fossil fuel resources. Development of petroleum, natural gas, and mineral extractions has attracted most of the over $40 billion in foreign investment in Kazakhstan since 1993 and accounts for some 57 percent of the nation’s industrial output (or approximately 13 percent of gross domestic product). According to some estimates,[51] Kazakhstan has the second largest uranium, chromium, lead, and zinc reserves; the third largest manganese reserves; the fifth largest copper reserves; and ranks in the top ten for coal, iron, and gold. It is also an exporter of diamonds. Perhaps most significant for economic development, Kazakhstan also has the 11th largest proven reserves of both petroleum and natural gas.[52]

In total, there are 160 deposits with over 2.7 billion tonnes (2.7 billion long tons) of petroleum. Oil explorations have shown that the deposits on the Caspian shore are only a small part of a much larger deposit. It is said that 3.5 billion tonnes (3.4 billion long tons) of oil and 2.5 billion cubic metres (88 billion cubic feet) of gas could be found in that area. Overall the estimate of Kazakhstan’s oil deposits is 6.1 billion tonnes (6.0 billion long tons). However, there are only three refineries within the country, situated in Atyrau,[53] Pavlodar, and Shymkent. These are not capable of processing the total crude output, so much of it is exported to Russia. According to the US Energy Information Administration, Kazakhstan was producing approximately 1,540,000 barrels (245,000 m3) of oil per day in 2009.[54]

Kazakhstan also possesses large deposits of phosphorite. Two of the largest deposits include the Karatau basin with 650 million tonnes of P2O5 and the Chilisai deposit of the Aqtobe phosphorite basin located in northwestern Kazakhstan, with resources of 500–800 million tonnes of 9 percent ore.[55][56]

On 17 October 2013, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) accepted Kazakhstan as «EITI Compliant», meaning that the country has a basic and functional process to ensure the regular disclosure of natural resource revenues.[57]

Climate

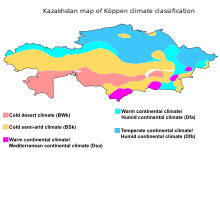

Kazakhstan map of Köppen climate classification

Kazakhstan has an «extreme» continental climate, with hot summers and very cold winters. Indeed, Astana is the second coldest capital city in the world after Ulaanbaatar. Precipitation varies between arid and semi-arid conditions, the winter being particularly dry.[58]

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almaty | 30/18 | 86/64 | 0/−8 | 33/17 |

| Shymkent | 32/17 | 91/66 | 4/−4 | 39/23 |

| Karaganda | 27/14 | 80/57 | −8/−17 | 16/1 |

| Astana | 27/15 | 80/59 | −10/−18 | 14/−1 |

| Pavlodar | 28/15 | 82/59 | −11/−20 | 12/−5 |

| Aktobe | 30/15 | 86/61 | −8/−16 | 17/2 |

Wildlife

There are ten nature reserves and ten national parks in Kazakhstan that provide safe haven for many rare and endangered plants and animals. Common plants are Astragalus, Gagea, Allium, Carex and Oxytropis; endangered plant species include native wild apple (Malus sieversii), wild grape (Vitis vinifera) and several wild tulip species (e.g., Tulipa greigii) and rare onion species Allium karataviense, also Iris willmottiana and Tulipa kaufmanniana.[60][61] Kazakhstan had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.23/10, ranking it 26th globally out of 172 countries.[62]

Common mammals include the wolf, red fox, corsac fox, moose, argali (the largest species of sheep), Eurasian lynx, Pallas’s cat, and snow leopards, several of which are protected.

Kazakhstan’s Red Book of Protected Species lists 125 vertebrates including many birds and mammals, and 404 plants including fungi, algae and lichens.[63]

Government and politics

Political system

Officially, Kazakhstan is a democratic, secular, constitutional unitary republic; Nursultan Nazarbayev led the country from 1991 to 2019.[64][65] He was succeeded by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.[66][67] The president may veto legislation that has been passed by the parliament and is also the commander in chief of the armed forces. The prime minister chairs the cabinet of ministers and serves as Kazakhstan’s head of government. There are three deputy prime ministers and sixteen ministers in the cabinet.[68]

Kazakhstan has a bicameral parliament composed of the Majilis (the lower house) and senate (the upper house).[69] Single-mandate districts popularly elect 107 seats in the Majilis; there also are ten members elected by party-list vote. The senate has 48 members. Two senators are selected by each of the elected assemblies (mäslihats) of Kazakhstan’s sixteen principal administrative divisions (fourteen regions plus the cities of Astana, Almaty, and Shymkent). The president appoints the remaining fifteen senators. Majilis deputies and the government both have the right of legislative initiative, though the government proposes most legislation considered by the parliament.

In 2020, Freedom House rated Kazakhstan as a «consolidated authoritarian regime», stating that freedom of speech is not respected and «Kazakhstan’s electoral laws do not provide for free and fair elections.»[70]

Political reforms

Reforms have begun to be implemented after the election of Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in June 2019. Tokayev supports a culture of opposition, public assembly, and loosening rules on forming political parties.[71] In June 2019, on the initiative of the President of Kazakhstan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev the National Council of Public Trust have been established as a platform in which wider society can discuss different views and strengthen the national conversation regarding government policies and reforms.[72] In July 2019, the President of Kazakhstan announced a concept of a ‘listening state’ that quickly and efficiently responds to all constructive requests of the country’s citizens.[73] A law will be passed to allow representatives from other parties to hold Chair positions on some Parliamentary committees, to foster alternative views and opinions.[when?] The minimum membership threshold needed to register a political party will be reduced from 40,000 to 20,000 members.[72] Special places for peaceful rallies in central areas will be allocated and a new draft law outlining the rights and obligations of organisers, participants and observers will be passed.[72] In an effort to increase public safety, President Tokayev has strengthened the penalties for those who commit crimes against individuals.[72]

On 17 September 2022, Tokayev signed a decree that limits presidential tenure to one term of seven years.[74] He furthermore announced the preparation of a new reform package to “decentralize” and “distribute” power between government institutions, such as ministries and regional heads. The reform package also seeks to modify the electoral system and increase the decision-making authorities of Kazakhstan’s regions.[75] The powers of the parliament were expanded at the expense of those of the president, whose relative are now also barred from holding government positions, while the Constitutional Court was restored and the death penalty abolished.[75][76]

Elections

Elections to the Majilis in September 2004, yielded a lower house dominated by the pro-government Otan Party, headed by President Nazarbayev. Two other parties considered sympathetic to the president, including the agrarian-industrial bloc AIST and the Asar Party, founded by President Nazarbayev’s daughter, won most of the remaining seats. The opposition parties which were officially registered and competed in the elections won a single seat. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe was monitoring the election, which it said fell short of international standards.[77]

On 4 December 2005, Nursultan Nazarbayev was re-elected in an apparent landslide victory. The electoral commission announced that he had won over 90% of the vote. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) concluded the election did not meet international standards despite some improvements in the administration of the election.[78]

On 17 August 2007, elections to the lower house of parliament were held and a coalition led by the ruling Nur-Otan party, which included the Asar Party, the Civil Party of Kazakhstan, and the Agrarian Party, won every seat with 88% of the vote. None of the opposition parties has reached the benchmark 7% level of the seats. Opposition parties made accusations of serious irregularities in the election.[79][80]

In 2010, president Nazarbayev rejected a call from supporters to hold a referendum to keep him in office until 2020. He insisted on presidential elections for a five-year term. In a vote held on 3 April 2011, president Nazarbayev received 95.54% of the vote with 89.9% of registered voters participating.[81] In March 2011, Nazarbayev outlined the progress made toward democracy by Kazakhstan.[82] As of 2010, Kazakhstan was reported on the Democracy Index by The Economist as an authoritarian regime.

On 26 April 2015, the fifth presidential election was held in Kazakhstan.[83] Nursultan Nazarbayev was re-elected with 97.7% of votes.[84]

On 19 March 2019, Nazarbayev announced his resignation from the presidency.[85] Kazakhstan’s senate speaker Kassym-Jomart Tokayev became acting president after Nursultan Nazarbayev’s resignation.[86] Later, Tokayev won the 2019 presidential election that was held on 9 June.[87]

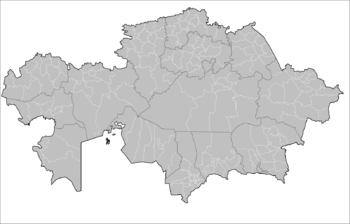

Administrative divisions

Kazakhstan is divided into seventeen regions (Kazakh: облыстар, oblystar; Russian: области, oblasti) plus three cities (Almaty, Astana and Shymkent) which are independent of the region in which they are situated. The regions are subdivided into 177 districts (Kazakh: аудандар, audandar; Russian: районы, rayony).[88] The districts are further subdivided into rural districts at the lowest level of administration, which include all rural settlements and villages without an associated municipal government.[89]

The cities of Almaty and Astana have status «state importance» and do not belong to any region. The city of Baikonur has a special status because it is being leased until 2050 to Russia for the Baikonur cosmodrome.[90] In June 2018 the city of Shymkent became a «city of republican significance».[91]

Each region is headed by an äkim (regional governor) appointed by the president. District äkimi are appointed by regional akims. Kazakhstan’s government relocated its capital from Almaty, established under the Soviet Union, to Astana on 10 December 1997.[92]

Municipal divisions

Municipalities exist at each level of administrative division in Kazakhstan. Cities of republican, regional, and district significance are designated as urban inhabited localities; all others are designated rural.[89] At the highest level are the cities of Almaty and Astana, which are classified as cities of republican significance on the administrative level equal to that of a region.[88] At the intermediate level are cities of regional significance on the administrative level equal to that of a district. Cities of these two levels may be divided into city districts.[88] At the lowest level are cities of district significance, and over two-thousand villages and rural settlements (aul) on the administrative level equal to that of rural districts.[88]

Urban centres

|

Largest cities or towns in Kazakhstan [1] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Almaty  Astana |

1 | Almaty | Almaty | 1,854,656 |  Shymkent  Karaganda |

| 2 | Astana | Astana | 1,078,384 | ||

| 3 | Shymkent | Turkistan | 1,009,086 | ||

| 4 | Karaganda | Karagandy | 497,712 | ||

| 5 | Aktobe | Aktobe | 487,994 | ||

| 6 | Taraz | Jambyl | 357,791 | ||

| 7 | Pavlodar | Pavlodar | 333,989 | ||

| 8 | Oskemen | East Kazakhstan | 331,614 | ||

| 9 | Semey | East Kazakhstan | 323,138 | ||

| 10 | Atyrau | Atyrau | 269,720 |

Foreign relations

Kazakhstan is a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Economic Cooperation Organization and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. The nations of Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan established the Eurasian Economic Community in 2000, to revive earlier efforts to harmonise trade tariffs and to create a free trade zone under a customs union. On 1 December 2007, it was announced that Kazakhstan had been chosen to chair the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe for the year 2010. Kazakhstan was elected a member of the UN Human Rights Council for the first time on 12 November 2012.[93]

Kazakhstan is also a member of the United Nations, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, Turkic Council, and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). It is an active participant in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation Partnership for Peace program.[94]

In 1999, Kazakhstan had applied for observer status at the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. The official response of the Assembly was that because Kazakhstan is partially located in Europe,[95][96] it could apply for full membership, but that it would not be granted any status whatsoever at the council until its democracy and human rights records improved.

Since independence in 1991, Kazakhstan has pursued what is known as the «multivector foreign policy» (Kazakh: көпвекторлы сыртқы саясат), seeking equally good relations with its two large neighbours, Russia and China, as well as with the United States and the rest of the Western world.[97][98] Russia leases approximately 6,000 square kilometres (2,317 sq mi) of territory enclosing the Baikonur Cosmodrome space launch site in south central Kazakhstan, where the first man was launched into space as well as Soviet space shuttle Buran and the well-known space station Mir.

On 11 April 2010, presidents Nazarbayev and Obama met at the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington, D.C., and discussed strengthening the strategic partnership between the United States and Kazakhstan. They pledged to intensify bilateral co-operation to promote nuclear safety and non-proliferation, regional stability in Central Asia, economic prosperity, and universal values.[99]

In April 2011, Obama called Nazarbayev and discussed many cooperative efforts regarding nuclear security, including securing nuclear material from the BN-350 reactor. They reviewed progress on meeting goals that the two presidents established during their bilateral meeting at the Nuclear Security Summit in 2010.[100] Since 2014 the Kazakhstani government has been bidding for a non-permanent member seat on the UN Security Council for 2017–2018.[101] On 28 June 2016 Kazakhstan was elected as a non-permanent member to serve on the UN Security Council for a two-year term.[102]

Kazakhstan has supported UN peacekeeping missions in Haiti, Western Sahara, and Côte d’Ivoire.[103] In March 2014, the Ministry of Defense chose 20 Kazakhstani military men as observers for the UN peacekeeping missions. The military personnel, ranking from captain to colonel, had to go through specialised UN training; they had to be fluent in English and skilled in using specialised military vehicles.[103]

In 2014, Kazakhstan gave Ukraine humanitarian aid during the conflict with Russian-backed rebels. In October 2014, Kazakhstan donated $30,000 to the International Committee of the Red Cross’s humanitarian effort in Ukraine. In January 2015, to help the humanitarian crisis, Kazakhstan sent $400,000 of aid to Ukraine’s southeastern regions.[104] President Nazarbayev said of the war in Ukraine, «The fratricidal war has brought true devastation to eastern Ukraine, and it is a common task to stop the war there, strengthen Ukraine’s independence and secure territorial integrity of Ukraine.»[105] Experts believe that no matter how the Ukraine crisis develops, Kazakhstan’s relations with the European Union will remain normal.[106] It is believed that Nazarbayev’s mediation is positively received by both Russia and Ukraine.[106]

Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement on 26 January 2015: «We are firmly convinced that there is no alternative to peace negotiations as a way to resolve the crisis in south-eastern Ukraine.»[107] In 2018, Kazakhstan signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[108]

On 6 March 2020, the Concept of the Foreign Policy of Kazakhstan for 2020–2030 was announced. The document outlines the following main points:

- An open, predictable and consistent foreign policy of the country, which is progressive in nature and maintains its endurance by continuing the course of the First President – the country at a new stage of development;

- Protection of human rights, development of humanitarian diplomacy and environmental protection;

- Promotion of the country’s economic interests in the international arena, including the implementation of state policy to attract investment;

- Maintaining international peace and security;

- Development of regional and multilateral diplomacy, which primarily involves strengthening mutually beneficial ties with key partners – Russia, China, the United States, Central Asian states and the EU countries, as well as through multilateral structures – the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Commonwealth of Independent States, and others.[109]

Kazakhstan’s memberships of international organisations include:

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

- Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

- Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council

- Individual Partnership Action Plan, with NATO, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro

- Turkic Council and the TÜRKSOY community. (The national language, Kazakh, is related to the other Turkic languages, with which it shares cultural and historical ties)

- United Nations

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

- UNESCO, where Kazakhstan is a member of its World Heritage Committee[110]

- Nuclear Suppliers Group as a participating government

- World Trade Organization[111]

- Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC)[112]

Based on these principles, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Kazakhstan has increasingly pursued an independent foreign policy, defined by its own foreign policy objectives and ambitions[113][114] through which the country attempts to balance its relations with «all the major powers and an equally principled aversion towards excessive dependence in any field upon any one of them, while also opening the country up economically to all who are willing to invest there.»[115]

Military

Most of Kazakhstan’s military was inherited from the Soviet Armed Forces’ Turkestan Military District. These units became the core of Kazakhstan’s new military. It acquired all the units of the 40th Army (the former 32nd Army) and part of the 17th Army Corps, including six land-force divisions, storage bases, the 14th and 35th air-landing brigades, two rocket brigades, two artillery regiments, and a large amount of equipment that had been withdrawn from over the Urals after the signing of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. Since the late 20th century, the Kazakhstan Army has focused on expanding the number of its armoured units. Since 1990, armoured units have expanded from 500 to 1,613 in 2005.

The Kazakh air force is composed mostly of Soviet-era planes, including 41 MiG-29s, 44 MiG-31s, 37 Su-24s and 60 Su-27s. A small naval force is maintained on the Caspian Sea.[116]

Kazakhstan sent 29 military engineers to Iraq to assist the US post-invasion mission in Iraq.[117] During the second Iraq War, Kazakhstani troops dismantled 4 million mines and other explosives, helped provide medical care to more than 5,000 coalition members and civilians, and purified 718 cubic metres (25,400 cu ft) of water.[118]

Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee (UQK) was established on 13 June 1992. It includes the Service of Internal Security, Military Counterintelligence, Border Guard, several Commando units, and Foreign Intelligence (Barlau). The latter is considered the most important part of KNB. Its director is Nurtai Abykayev.

Since 2002, the joint tactical peacekeeping exercise «Steppe Eagle» has been hosted by the Kazakhstan government. «Steppe Eagle» focuses on building coalitions and gives participating nations the opportunity to work together. During the Steppe Eagle exercises, the KAZBAT peacekeeping battalion operates within a multinational force under a unified command within multidisciplinary peacekeeping operations, with NATO and the U.S. Military.[119]

In December 2013, Kazakhstan announced it will send officers to support United Nations Peacekeeping forces in Haiti, Western Sahara, Ivory Coast and Liberia.[120]

Human rights

The Economist Intelligence Unit has consistently ranked Kazakhstan as an «authoritarian regime» in its Democracy Index, ranking it 128th out of 167 countries for 2020.[121][122]

Kazakhstan was ranked 122th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index for 2022; previously it ranked 155th for 2021.[123]

Kazakhstan’s human rights situation has been described as poor by independent observers. In its 2015 report of human rights in the country, Human Rights Watch said that «Kazakhstan heavily restricts freedom of assembly, speech, and religion.»[124] It has also described the government as authoritarian.[125] In 2014, authorities closed newspapers, jailed or fined dozens of people after peaceful but unsanctioned protests, and fined or detained worshipers for practising religion outside state controls. Government critics, including opposition leader Vladimir Kozlov, remained in detention after unfair trials. In mid-2014, Kazakhstan adopted new criminal, criminal executive, criminal procedural, and administrative codes, and a new law on trade unions, which contain articles restricting fundamental freedoms and are incompatible with international standards. Torture remains common in places of detention.»[126] However, Kazakhstan has achieved significant progress in reducing the prison population.[127] The 2016 Human Rights Watch report commented that Kazakhstan «took few meaningful steps to tackle a worsening human rights record in 2015, maintaining a focus on economic development over political reform.»[128] Some critics of the government have been arrested for allegedly spreading false information about the COVID-19 pandemic in Kazakhstan.[129] Various police reforms, like creation of local police service and zero-tolerance policing, aimed at bringing police closer to local communities have not improved cooperation between police and ordinary citizens.[130]

According to a U.S. government report released in 2014, in Kazakhstan:

The law does not require police to inform detainees that they have the right to an attorney, and police did not do so. Human rights observers alleged that law enforcement officials dissuaded detainees from seeing an attorney, gathered evidence through preliminary questioning before a detainee’s attorney arrived, and in some cases used corrupt defense attorneys to gather evidence. […][131]

The law does not adequately provide for an independent judiciary. The executive branch sharply limited judicial independence. Prosecutors enjoyed a quasi-judicial role and had the authority to suspend court decisions. Corruption was evident at every stage of the judicial process. Although judges were among the most highly paid government employees, lawyers and human rights monitors alleged that judges, prosecutors, and other officials solicited bribes in exchange for favorable rulings in the majority of criminal cases.[131]

Kazakhstan’s global rank in the World Justice Project’s 2015 Rule of Law Index was 65 out of 102; the country scored well on «Order and Security» (global rank 32/102), and poorly on «Constraints on Government Powers» (global rank 93/102), «Open Government» (85/102) and «Fundamental Rights» (84/102, with a downward trend marking a deterioration in conditions).[132]

The ABA Rule of Law Initiative of the American Bar Association has programs to train justice sector professionals in Kazakhstan.[133][134]

Kazakhstan’s Supreme Court has taken steps to modernise and to increase transparency and oversight over the country’s legal system. With funding from the US Agency for International Development, the ABA Rule of Law Initiative began a new program in April 2012 to strengthen the independence and accountability of Kazakhstan’s judiciary.[135]

In an effort to increase transparency in the criminal justice and court system, and improve human rights, Kazakhstan intended to digitise all investigative, prosecutorial and court records by 2018.[136] Many criminal cases are closed before trial on the basis of reconciliation between the defendant and the victim because they simplify the work of the law-enforcement officers, release the defendant from punishment, and pay little regard to the victim’s rights.[137]

Homosexuality has been legal in Kazakhstan since 1997, although it is still socially unacceptable in most areas.[138] Discrimination against LGBT people in Kazakhstan is widespread.[139][140]

Economy

GDP per capita development, since 1973

A proportional representation of Kazakhstan exports, 2019

Kazakhstan’s economy, supported by rising oil output and prices, grew at an average of 8 percent per year until 2013, before suffering a slowdown in 2014 and 2015.[141] Kazakhstan was the first former Soviet Republic to repay all of its debt to the International Monetary Fund, 7 years ahead of schedule.[142]

Kazakhstan has a GDP of $179.332 billion and an annual growth rate of 4.5 percent. Per capita, Kazakhstan’s GDP stands at $9,686.[143]

Kazakhstan’s increased role in global trade and central positioning on the new Silk Road gave the country the potential to open its markets to billions of people.[144] Kazakhstan joined the World Trade Organization in 2015.[145]

Buoyed by high world crude oil prices, GDP growth figures were between 8.9 percent and 13.5 percent from 2000 to 2007 before decreasing to 1 to 3 percent in 2008 and 2009, and then rising again from 2010.[146] Other major exports of Kazakhstan include wheat, textiles, and livestock. Kazakhstan is a leading exporter of uranium.[147][148]

Kazakhstan’s economy grew by 4.6 percent in 2014.[149] The country experienced a slowdown in economic growth from 2014 sparked by falling oil prices and the effects of the Ukrainian crisis.[150] The country devalued its currency by 19 percent in February 2014.[151] Another 22 percent devaluation occurred in August 2015.[152]

Kazakhstan’s government continued to follow a conservative fiscal policy by controlling budget spending and accumulating oil revenue savings in its Oil Fund – Samruk-Kazyna. The global financial crisis forced Kazakhstan to increase its public borrowing to support the economy. Public debt increased to 13.4 per cent in 2013 from 8.7 per cent in 2008. Between 2012 and 2013, the government achieved an overall fiscal surplus of 4.5 per cent.[153]

Since 2002, Kazakhstan has sought to manage strong inflows of foreign currency without sparking inflation. Inflation has not been under strict control, however, registering 6.6 percent in 2002, 6.8 percent in 2003, and 6.4 percent in 2004.

In March 2002, the U.S. Department of Commerce granted Kazakhstan market economy status under US trade law. This change in status recognised substantive market economy reforms in the areas of currency convertibility, wage rate determination, openness to foreign investment, and government control over the means of production and allocation of resources.

Kazakhstan weathered the global financial crisis[citation needed] by combining fiscal relaxation with monetary stabilisation. In 2009, the government introduced large-scale support measures such as the recapitalisation of banks and support for the real estate and agricultural sectors, as well as for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The total value of the stimulus programs amounted to $21 billion, or 20 per cent of the country’s GDP, with $4 billion going to stabilise the financial sector.[154] During the global economic crisis, Kazakhstan’s economy contracted by 1.2 percent in 2009, while the annual growth rate subsequently increased to 7.5 percent and 5 percent in 2011 and 2012, respectively.[141]

In September 2002, Kazakhstan became the first country in the CIS to receive an investment grade credit rating from a major international credit rating agency.[155] By late December 2003, Kazakhstan’s gross foreign debt was about $22.9 billion. Total governmental debt was $4.2 billion, 14 percent of GDP. There has been a reduction in the ratio of debt to GDP. The ratio of total governmental debt to GDP was 21.7 percent in 2000, 17.5 percent in 2001, and 15.4 percent in 2002. In 2019, it rose to 19.2 percent.[156]

Economic growth, combined with earlier tax and financial sector reforms, has dramatically improved government finance from the 1999 budget deficit level of 3.5 percent of GDP to a deficit of 1.2 percent of GDP in 2003. Government revenues grew from 19.8 percent of GDP in 1999 to 22.6 percent of GDP in 2001, but decreased to 16.2 percent of GDP in 2003. In 2000, Kazakhstan adopted a new tax code in an effort to consolidate these gains.

On 29 November 2003, the Law on Changes to Tax Code which reduced tax rates was adopted. The value added tax fell from 16% to 15%, the social tax, payable by all employers, from 21 percent to 20 percent, and the personal income tax, from 30 percent to 20 percent. On 7 July 2006, the personal income tax was reduced even further to a flat rate of 5 percent for personal income in the form of dividends and 10 percent for other personal income. Kazakhstan furthered its reforms by adopting a new land code on 20 June 2003, and a new customs code on 5 April 2003.

A map of Kazakhstan’s imports, 2013

Energy has been the leading economic sector. Production of crude oil and natural gas condensate from the oil and gas basins of Kazakhstan amounted to 79.2 million tonnes (77.9 million long tons; 87.3 million short tons) in 2012 up from 51.2 million tonnes (50.4 million long tons; 56.4 million short tons) in 2003. Kazakhstan raised oil and gas condensate exports to 44.3 million tons in 2003, 13 percent higher than in 2002. Gas production in Kazakhstan in 2003, amounted to 13.9 billion cubic metres (490 billion cubic feet), up 22.7 percent compared to 2002, including natural gas production of 7.3 billion cubic metres (260 billion cubic feet). Kazakhstan holds about 4 billion tonnes (3.9 billion long tons; 4.4 billion short tons) of proven recoverable oil reserves and 2,000 cubic kilometres (480 cubic miles) of gas. Kazakhstan is the 19th largest oil-producing nation in the world.[157] Kazakhstan’s oil exports in 2003, were valued at more than $7 billion, representing 65 percent of overall exports and 24 percent of the GDP. Major oil and gas fields and recoverable oil reserves are Tengiz with 7 billion barrels (1.1 billion cubic metres); Karachaganak with 8 billion barrels (1.3 billion cubic metres) and 1,350 cubic kilometres (320 cubic miles) of natural gas; and Kashagan with 7 to 9 billion barrels (1.4 billion cubic metres).

KazMunayGas (KMG), the national oil and gas company, was created in 2002 to represent the interests of the state in the oil and gas industry. The Tengiz Field was jointly developed in 1993 as a 40-year Tengizchevroil venture between Chevron Texaco (50 percent), US ExxonMobil (25 percent), KazMunayGas (20 percent), and LukArco (5 percent).[158] The Karachaganak natural gas and gas condensate field is being developed by BG, Agip, ChevronTexaco, and Lukoil.[159] Also Chinese oil companies are involved in Kazakhstan’s oil industry.[160]

Kazakhstan instituted a pension reform program in 1998. By January 2012, the pension assets were about $17 billion (KZT 2.5 trillion). There are 11 saving pension funds in the country. The State Accumulating Pension Fund, the only state-owned fund, was privatised in 2006. The country’s unified financial regulatory agency oversees and regulates pension funds. The growing demand of pension funds for investment outlets triggered the development of the debt securities market. Pension fund capital is being invested almost exclusively in corporate and government bonds, including the government of Kazakhstan Eurobonds. The government of Kazakhstan was studying a project to create a unified national pension fund and transfer all the accounts from the private pension funds into it.[161]

The Kazakh National Bank introduced deposit insurance in a campaign to strengthen the banking sector. Several major foreign banks had branches in Kazakhstan, including RBS, Citibank, and HSBC. Kookmin and UniCredit both entered Kazakhstan’s financial services market through acquisitions and stake-building.[citation needed]

According to the 2010–11 World Economic Forum in Global Competitiveness Report, Kazakhstan was ranked 72nd in the world in economic competitiveness.[162] One year later, the Global Competitiveness Report ranked Kazakhstan 50th in most competitive markets.[163]

In 2012, Kazakhstan attracted $14 billion of foreign direct investment inflows into the country at a 7 percent growth rate.[164] In 2018, $24 billion of FDI was directed into Kazakhstan, a significant increase since 2012.[165]

Kazakhstan climbed to 41st on the 2018 Economic Freedom Index published by The Wall Street Journal and The Heritage Foundation.[166]

Kazakhstan’s economy grew at an average of 8 percent per year over the past decade on the back of hydrocarbon exports.[141] Despite the lingering uncertainty of the global economy, Kazakhstan’s economy has been stable. GDP growth in January–September 2013 was 5.7 percent, according to preliminary calculations of the Ministry Economy and Budget Planning.[167]

From January to September 2014 Kazakhstan’s GDP grew at 4 percent.[168] According to the results from the first half of the year, the current account surplus is $6.6 billion, a figure two times higher than that of the first half of 2013.[168] According to the Chairman of the National Bank of Kazakhstan, Kairat Kelimbetov, the increase was caused by a trade surplus of 17.4 per cent, or approximately US$22.6 billion.[168] The overall inflation rate for 2014 is forecasted at 7.4 percent.[168]

China is one of the main economic and trade partners of Kazakhstan. In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in which Kazakhstan functions as a transit hub.[169]

Foreign trade

Kazakhstan’s foreign trade turnover in 2018 was $93.5 billion, which is 19.7 percent more compared to 2017. Export in 2018 reached $67 billion (up 25.7 percent in comparison to 2017) and import was $32.5 billion (up 9.9 percent in comparison to 2017).[170] Exports accounted for 40.1 percent of Kazakhstan’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018. Kazakhstan exports 800 products to 120 countries.[171]

Agriculture

Agriculture accounts for approximately 5 percent of Kazakhstan’s GDP.[90] Grain, potatoes, grapes, vegetables, melons and livestock are the most important agricultural commodities. Agricultural land occupies more than 846,000 square kilometres (327,000 sq mi). The available agricultural land consists of 205,000 km2 (79,000 sq mi) of arable land and 611,000 km2 (236,000 sq mi) of pasture and hay land. Over 80 percent of the country’s total area is classified as agricultural land, including almost 70 percent occupied by pasture. Its arable land has the second highest availability per inhabitant (1.5 hectares).[172]

Chief livestock products are dairy products, leather, meat, and wool. The country’s major crops include wheat, barley, cotton, and rice. Wheat exports, a major source of hard currency, rank among the leading commodities in Kazakhstan’s export trade. In 2003 Kazakhstan harvested 17.6 million tons of grain in gross, 2.8% higher compared to 2002. Kazakhstani agriculture still has many environmental problems from mismanagement during its years in the Soviet Union. Some Kazakh wine is produced in the mountains to the east of Almaty.[173]

Kazakhstan is thought to be one of the places that the apple originated, particularly the wild ancestor of Malus domestica, Malus sieversii.[174] It has no common name in English, but is known in its native Kazakhstan as alma. The region where it is thought to originate is called Almaty: «rich with apple».[175] This tree is still found wild in the mountains of Central Asia, in southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Xinjiang in China.

Infrastructure

Map of Kazakhstan railway network

Train 22 Kyzylorda – Semipalatinsk, hauled by a Kazakhstan Temir Zholy 2TE10U diesel locomotive. Picture taken near Aynabulak, Kazakhstan

Railways provide 68 percent of all cargo and passenger traffic to over 57 percent of the country. There are 15,333 km (9,527 mi) in common carrier service, excluding industrial lines.[176]15,333 km (9,527 mi) of 1,520 mm (4 ft 11+27⁄32 in) gauge, 4,000 km (2,500 mi) electrified, in 2012.[176] Most cities are connected by railroad; high-speed trains go from Almaty (the southernmost city) to Petropavl (the northernmost city) in about 18 hours.

Kazakhstan Temir Zholy (KTZ) is the national railway company. KTZ cooperates with French locomotive manufacturer Alstom in developing Kazakhstan’s railway infrastructure. Alstom has more than 600 staff and two joint ventures with KTZ and its subsidiary in Kazakhstan.[177] In July 2017, Alstom opened its first locomotive repairing centre in Kazakhstan. It is the only repairing centre in Central Asia and the Caucasus.[178]

As the Kazakhstani rail system was designed during the Soviet era, rail routes reflected the goals of Soviet planning. This has caused anomalies such as the route from Oral to Aktobe now passes briefly through Russian territory.[citation needed]

Astana Nurly Zhol railway station, the most modern railway station in Kazakhstan, was opened in Astana on 31 May 2017. The opening of the station coincided with the start of the Expo 2017 international exhibition. According to Kazakhstan Railways (KTZ), the 120,000m2 station was expected to be used by 54 trains and would have the capacity to handle 35,000 passengers a day.[179]

There is a small 8.56 km (5.32 mi) metro system in Almaty. Second and third metro lines were planned for the future. The second line would intersect with the first line at Alatau and Zhibek Zholy stations.[180] In May 2011, the construction of the second phase of the Almaty Metro line 1 began. The general contractor is Almatymetrokurylys. More[when?] than 300 m (980 ft) of tunnels on the extension project have been excavated. The extension includes five new stations and will connect the downtown area of Almaty with Kalkaman in the suburbs. Its length will be 8.62 km (5.36 mi).[181] The construction is divided into 3 phases. The first phase (the current[when?] phase) will be the addition of two stations: Sairan and Moscow, a length of 2.7 km (1.7 mi).[181] For more details see: Almaty Metro.There was a tram system of 10 lines which operated from 1937 to 2015.[182]

The Astana Metro system has been under construction, but was abandoned at one point in 2013.[183] In May 2015, an agreement was signed for the project to be resumed.[184] There is an 86 km (53 mi) tram network, which began service in 1965 with, as of 2012, 20 regular and three special routes.[185]

The Khorgos Gateway dry port is one of Kazakhstan’s primary dry ports for handling trans-Eurasian trains, which travel more than 9,000 km (5,600 mi) between China and Europe. The Khorgos Gateway dry port is surrounded by Khorgos Eastern Gate SEZ which officially commenced operations in December 2016.[186]

In 2009 the European Commission blacklisted all Kazakh air carriers with a sole exception of Air Astana.[187] Thereafter, Kazakhstan took measures to modernise and revamp its air safety oversight. In 2016 the European air safety authorities removed all Kazakh airlines from the blacklist, saying there was «sufficient evidence of compliance» with international standards by Kazakh Airlines and the Civil Aviation Committee.[188]

Tourism

Kazakhstan is the ninth-largest country by area and the largest landlocked country in the world. As of 2014, tourism accounted for 0.3 percent of Kazakhstan’s GDP, but the government had plans to increase it to 3 percent by 2020.[189][190] According to the World Economic Forum’s Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report of 2017, travel and tourism industry GDP in Kazakhstan was $3.08 billion or only 1.6 percent of total GDP. The WEF ranked Kazakhstan 80th in its 2019 report.[191]

In 2017, Kazakhstan ranked 43rd in the number of tourist arrivals. In 2014, The Guardian described tourism in Kazakhstan as, «hugely underdeveloped», despite the country’s mountain, lake and desert landscapes.[192] Factors hampering an increase in tourism were said to include high prices, «shabby infrastructure,» «poor service» and the difficulties of travel in a large underdeveloped country.[192] Even for Kazakhs, going for holiday abroad may have cost only half the price of taking a holiday in Kazakhstan.[192]

The Kazakh Government, long characterised as authoritarian with a history of human rights abuses and suppression of political opposition,[9] in 2015 issued a «Tourism Industry Development Plan 2020.» It aimed to establish five tourism clusters in Kazakhstan: Astana city, Almaty city, East Kazakhstan, South Kazakhstan, and West Kazakhstan Oblasts. It also sought investment of $4 billion and the creation of 300,000 new jobs in the tourism industry by 2020.[193][192]

Kazakhstan has offered a permanent visa-free regime for up to 90 days to citizens of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Russia and Ukraine, and for up to 30 days to citizens of Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Serbia, South Korea, Tajikistan, Turkey, UAE and Uzbekistan. It also established a visa-free regime for citizens of 54 countries, including the European Union and OECD member states, the U.S., Japan, Mexico, Australia and New Zealand.[194][195]

Green economy

Kazakhstan launched the Green Economy Plan in 2013. It committed Kazakhstan to meet 50 percent of its energy needs from alternative and renewable sources by 2050.[196] The green economy was projected to increase GDP by 3 percent and create some 500,000 jobs.[197] The government set prices for energy produced from renewable sources. The price of 1 kilowatt-hour for energy produced by wind power plants was set at 22.68 tenge ($0.12), for 1 kilowatt-hour produced by small hydro-power plants 16.71 tenges ($0.09), and from biogas plants 32.23 tenges ($0.18).[198]

Foreign direct investment

Kazakhstan has attracted $330 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) from more than 120 countries since its independence.[199] In 2015, the U.S. State Department said Kazakhstan was widely considered to have the best investment climate in the region.[200] In 2014,

President Nazarbayev signed into law tax concessions to promote foreign direct investment which included a 10-year exemption from corporation tax, an eight-year exemption from property tax, and a 10-year freeze on most other taxes.[201] Other incentives include a refund on capital investments of up to 30 percent once a production facility is in operation.[201]

In 2014, the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Kazakhstan created the partnership for Re-Energizing the Reform Process in Kazakhstan to work with international financial institutions to channel US$2.7 billion provided by the Kazakh government into important sectors of Kazakhstan’s economy.[202]

As of May 2014, Kazakhstan had attracted $190 billion in gross foreign investments since its independence in 1991 and it led the CIS countries in terms of FDI attracted per capita.[203] One of the factors that attract foreign direct investments is country’s political stability.

The OECD 2017 Investment Policy Review noted that «great strides» had been made to open up opportunities to foreign investors and improve policy to attract FDI.[204]

Banking

The banking industry of Kazakhstan went through a boom-and-bust cycle in the early 21st century. After several years of rapid expansion in the mid-2000s, the banking industry collapsed in 2008. Several large banking groups, including BTA Bank J.S.C. and Alliance Bank, defaulted soon thereafter. The industry shrank and was restructured, with system-wide loans dropping from 59 percent of GDP in 2007 to 39 percent in 2011. Although the Russian and Kazakhstani banking systems share some common features, there are key differences: Banks in Kazakhstan experienced a lengthy period of political stability and economic growth, which helped push Kazakhstan’s banking system to a higher level of development. Banking technology and personnel qualifications were stronger in Kazakhstan. On the negative side, past stability in Kazakhstan arose from the concentration of virtually all political power in the hands of a single individual – the key factor in any assessment of system or country risk.[205]

Bond market

In October 2014, Kazakhstan introduced its first overseas dollar bonds in 14 years.[206] Kazakhstan issued $2.5 billion of 10- and 30-year bonds on 5 October 2014, in what was the nation’s first dollar-denominated overseas sale since 2000.[206] Kazakhstan sold $1.5 billion of 10-year dollar bonds to yield 1.5 percentage points above midswaps and $1 billion of 30-year debt at two percentage points over midswaps.[206] The country drew bids for $11 billion.[206]

Housing market

As of 2016, the total housing area in Kazakhstan was 342.6 million square metres (3,688 million square feet), an average of 21.4 m2 (230 sq ft) per person.[207] The housing area per person increased by 20% in the period from 2005 to 2016,[207] but remained below the UN’s recommended standard of 30 square metres (320 square feet) per person.

«Nurly Jol» economic policy

On 11 November 2014, the President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev delivered an unexpected state-of-the-nation address in Astana at an extended session of the Political Council of the Nur Otan party, introducing a «Nurly Jol» (Bright Path), a new economic policy that implies massive state investment in infrastructure over the next several years.[208] The «Nurly Zhol» policy is accepted as preventive measures needed to help steer the economy towards sustainable growth in the context of the modern global economic and geopolitical challenges, such as the 25 percent-reduction in the oil price, reciprocal sanctions between the West and Russia over Ukraine, etc.[208] The policy embraces all aspects of economic growth, including finances, industry and social welfare, but especially emphasises investments into the development of infrastructure and construction works.[208] Given recent decreases in revenues from the export of raw materials, funds will be used from Kazakhstan’s National Fund.[208]

Economic competitiveness

In the 2020 Doing Business Report by the World Bank, Kazakhstan ranked 25th globally and as the number one best country globally for protecting minority investors’ rights.[209] Kazakhstan achieved its goal of entering the top 50 most competitive countries in 2013 and has maintained its position in the 2014–2015 World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report that was published at the beginning of September 2014.[210] Kazakhstan is ahead of other states in the CIS in almost all of the report’s pillars of competitiveness, including institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market development, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication and innovation, lagging behind only in the category of health and primary education.[210] The Global Competitiveness Index gives a score from 1 to 7 in each of these pillars, and Kazakhstan earned an overall score of 4.4.[210]

Corruption

In 2005, the World Bank listed Kazakhstan as a corruption hotspot, on a par with Angola, Bolivia, Kenya, Libya and Pakistan.[211] In 2012, Kazakhstan ranked low in an index of the least corrupt countries[212] and the World Economic Forum listed corruption as the biggest problem in doing business in the country.[212] A 2017 OECD report on Kazakhstan indicated that Kazakhstan has reformed laws with regard to the civil service, judiciary, instruments to prevent corruption, access to information, and prosecuting corruption.[213] Kazakhstan has implemented anticorruption reforms that have been recognised by organizations like Transparency International.[214]

In 2011 Switzerland confiscated US$48 million in Kazakhstani assets from Swiss bank accounts, as a result of a bribery investigation in the United States.[215] US officials believed the funds represented bribes paid by American officials to Kazakhstani officials in exchange for oil or prospecting rights in Kazakhstan. Proceedings eventually involved US$84 million in the US and another US$60 million in Switzerland.[215]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Kazakh Anti-Corruption Agency signed a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty in February 2015.[216]

Science and technology

Trends in research expenditure in Central Asia, as a percentage of GDP, 2001–2013. Source: UNESCO Science Report: 2030 (2015), Figure 14.3

Research remains largely concentrated in Kazakhstan’s largest city and former capital, Almaty, home to 52 percent of research personnel. Public research is largely confined to institutes, with universities making only a token contribution. Research institutes receive their funding from national research councils under the umbrella of the Ministry of Education and Science. Their output, however, tends to be disconnected from market needs. In the business sector, few industrial enterprises conduct research themselves.[217][218]

Group of Kazakhstan physicists in collaboration with Uzbek researchers working at the ion accelerator DC-60

One of the most ambitious targets of the State Programme for Accelerated Industrial and Innovative Development adopted in 2010 is to raise the country’s level of expenditure on research and development to 1 percent of GDP by 2015. By 2013, this ratio stood at 0.18 percent of GDP. It will be difficult to reach the target as long as economic growth remains strong.[needs update] Since 2005, the economy has grown faster (by 6 percent in 2013) than gross domestic expenditure on research and development, which only progressed from PPP$598 million to PPP$714 million between 2005 and 2013.[218]

Innovation expenditure more than doubled in Kazakhstan between 2010 and 2011, representing KZT 235 billion (circa US$1.6 billion), or around 1.1 percent of GDP. Some 11 percent of the total was spent on research and development. This compares with about 40 to 70 percent of innovation expenditure in developed countries. This augmentation was due to a sharp rise in product design and the introduction of new services and production methods over this period, to the detriment of the acquisition of machinery and equipment, which has traditionally made up the bulk of Kazakhstan’s innovation expenditure. Training costs represented just 2 percent of innovation expenditure, a much lower share than in developed countries.[217][218] Kazakhstan was ranked 79th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.[219]

In December 2012, President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy with the slogan «Strong Business, Strong State.» This pragmatic strategy proposes sweeping socio-economic and political reforms to hoist Kazakhstan among the top 30 economies by 2050. In this document, Kazakhstan gives itself 15 years to evolve into a knowledge economy. New sectors are to be created during each five-year plan. The first of these, covering the years 2010–2014, focused on developing industrial capacity in car manufacturing, aircraft engineering and the production of locomotives, passenger and cargo railroad cars. During the second five-year plan to 2019, the goal is to develop export markets for these products. To enable Kazakhstan to enter the world market of geological exploration, the country intends to increase the efficiency of traditional extractive sectors such as oil and gas. It also intends to develop rare earth metals, given their importance for electronics, laser technology, communication and medical equipment. The second five-year plan coincides with the development of the Business 2020 roadmap for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which makes provision for the allocation of grants to SMEs in the regions and for microcredit. The government and the National Chamber of Entrepreneurs also plan to develop an effective mechanism to help start-ups.[218]

During subsequent five-year plans to 2050, new industries will be established in fields such as mobile, multi-media, nano- and space technologies, robotics, genetic engineering and alternative energy. Food processing enterprises will be developed with an eye to turning the country into a major regional exporter of beef, dairy and other agricultural products. Low-return, water-intensive crop varieties will be replaced with vegetable, oil and fodder products. As part of the shift to a «green economy» by 2030, 15% of acreage will be cultivated with water-saving technologies. Experimental agrarian and innovational clusters will be established and drought-resistant genetically modified crops developed.[218]

The Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy fixes a target of devoting 3 percent of GDP to research and development by 2050 to allow for the development of new high-tech sectors.[218]

The Digital Kazakhstan program was launched in 2018 to boost the country’s economic growth through the implementation of digital technologies. Kazakhstan’s digitization efforts generated 800 billion tenges (US$1.97 billion) in two years. The program helped create 120,000 jobs and attracted 32.8 billion tenges (US$80.7 million) of investment into the country.