| Romeo and Juliet | |

|---|---|

An 1870 oil painting by Ford Madox Brown depicting the play’s balcony scene |

|

| Written by | William Shakespeare |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | 1597[a] |

| Original language | English |

| Series | First Quarto |

| Subject | Love |

| Genre | Shakespearean tragedy |

| Setting | Italy (Verona and Mantua) |

The opening act of Romeo and Juliet.

See also: Acts II, III, IV, V

Romeo and Juliet is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare’s most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with Hamlet, is one of his most frequently performed plays. Today, the title characters are regarded as archetypal young lovers.

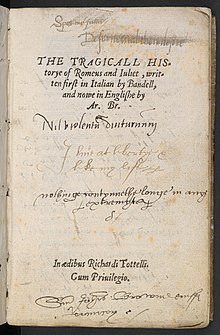

Romeo and Juliet belongs to a tradition of tragic romances stretching back to antiquity. The plot is based on an Italian tale translated into verse as The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet by Arthur Brooke in 1562 and retold in prose in Palace of Pleasure by William Painter in 1567. Shakespeare borrowed heavily from both but expanded the plot by developing a number of supporting characters, particularly Mercutio and Paris. Believed to have been written between 1591 and 1595, the play was first published in a quarto version in 1597. The text of the first quarto version was of poor quality, however, and later editions corrected the text to conform more closely with Shakespeare’s original.

Shakespeare’s use of poetic dramatic structure (including effects such as switching between comedy and tragedy to heighten tension, the expansion of minor characters, and numerous sub-plots to embellish the story) has been praised as an early sign of his dramatic skill. The play ascribes different poetic forms to different characters, sometimes changing the form as the character develops. Romeo, for example, grows more adept at the sonnet over the course of the play.

Romeo and Juliet has been adapted numerous times for stage, film, musical, and opera venues. During the English Restoration, it was revived and heavily revised by William Davenant. David Garrick’s 18th-century version also modified several scenes, removing material then considered indecent, and Georg Benda’s Romeo und Julie omitted much of the action and used a happy ending. Performances in the 19th century, including Charlotte Cushman’s, restored the original text and focused on greater realism. John Gielgud’s 1935 version kept very close to Shakespeare’s text and used Elizabethan costumes and staging to enhance the drama. In the 20th and into the 21st century, the play has been adapted in versions as diverse as George Cukor’s 1936 film Romeo and Juliet, Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film Romeo and Juliet, Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film Romeo + Juliet, and most recently, Carlo Carlei’s 2013 film Romeo and Juliet.

Characters

- Ruling house of Verona

- Prince Escalus is the ruling Prince of Verona.

- Count Paris is a kinsman of Escalus who wishes to marry Juliet.

- Mercutio is another kinsman of Escalus, a friend of Romeo.

- House of Capulet

- Capulet is the patriarch of the house of Capulet.

- Lady Capulet is the matriarch of the house of Capulet.

- Juliet Capulet is the 13-year-old daughter of Capulet, the play’s female protagonist.

- Tybalt is a cousin of Juliet, the nephew of Lady Capulet.

- The Nurse is Juliet’s personal attendant and confidante.

- Rosaline is Lord Capulet’s niece, Romeo’s love in the beginning of the story.

- Peter, Sampson, and Gregory are servants of the Capulet household.

- House of Montague

- Montague is the patriarch of the house of Montague.

- Lady Montague is the matriarch of the house of Montague.

- Romeo Montague, the son of Montague, is the play’s male protagonist.

- Benvolio is Romeo’s cousin and best friend.

- Abram and Balthasar are servants of the Montague household.

- Others

- Friar Laurence is a Franciscan friar and Romeo’s confidant.

- Friar John is sent to deliver Friar Laurence’s letter to Romeo.

- An Apothecary who reluctantly sells Romeo poison.

- A Chorus reads a prologue to each of the first two acts.

Synopsis

L’ultimo bacio dato a Giulietta da Romeo by Francesco Hayez. Oil on canvas, 1823.

The play, set in Verona, Italy, begins with a street brawl between Montague and Capulet servants who, like the masters they serve, are sworn enemies. Prince Escalus of Verona intervenes and declares that further breach of the peace will be punishable by death. Later, Count Paris talks to Capulet about marrying his daughter Juliet, but Capulet asks Paris to wait another two years and invites him to attend a planned Capulet ball. Lady Capulet and Juliet’s Nurse try to persuade Juliet to accept Paris’s courtship.

Meanwhile, Benvolio talks with his cousin Romeo, Montague’s son, about Romeo’s recent depression. Benvolio discovers that it stems from unrequited infatuation for a girl named Rosaline, one of Capulet’s nieces. Persuaded by Benvolio and Mercutio, Romeo attends the ball at the Capulet house in hopes of meeting Rosaline. However, Romeo instead meets and falls in love with Juliet. Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt, is enraged at Romeo for sneaking into the ball but is only stopped from killing Romeo by Juliet’s father, who does not wish to shed blood in his house. After the ball, in what is now famously known as the «balcony scene», Romeo sneaks into the Capulet orchard and overhears Juliet at her window vowing her love to him in spite of her family’s hatred of the Montagues. Romeo makes himself known to her, and they agree to be married. With the help of Friar Laurence, who hopes to reconcile the two families through their children’s union, they are secretly married the next day.

Tybalt, meanwhile, still incensed that Romeo had sneaked into the Capulet ball, challenges him to a duel. Romeo, now considering Tybalt his kinsman, refuses to fight. Mercutio is offended by Tybalt’s insolence, as well as Romeo’s «vile submission»,[1] and accepts the duel on Romeo’s behalf. Mercutio is fatally wounded when Romeo attempts to break up the fight, and declares a curse upon both households before he dies. («A plague o’ both your houses!») Grief-stricken and racked with guilt, Romeo confronts and slays Tybalt.

Benvolio argues that Romeo has justly executed Tybalt for the murder of Mercutio. The Prince, now having lost a kinsman in the warring families’ feud, exiles Romeo from Verona, under penalty of death if he ever returns. Romeo secretly spends the night in Juliet’s chamber, where they consummate their marriage. Capulet, misinterpreting Juliet’s grief, agrees to marry her to Count Paris and threatens to disown her when she refuses to become Paris’s «joyful bride».[2] When she then pleads for the marriage to be delayed, her mother rejects her.

Juliet visits Friar Laurence for help, and he offers her a potion that will put her into a deathlike coma or catalepsy for «two and forty hours».[3] The Friar promises to send a messenger to inform Romeo of the plan so that he can rejoin her when she awakens. On the night before the wedding, she takes the drug and, when discovered apparently dead, she is laid in the family crypt.

The messenger, however, does not reach Romeo and, instead, Romeo learns of Juliet’s apparent death from his servant, Balthasar. Heartbroken, Romeo buys poison from an apothecary and goes to the Capulet crypt. He encounters Paris who has come to mourn Juliet privately. Believing Romeo to be a vandal, Paris confronts him and, in the ensuing battle, Romeo kills Paris. Still believing Juliet to be dead, he drinks the poison. Juliet then awakens and, discovering that Romeo is dead, stabs herself with his dagger and joins him in death. The feuding families and the Prince meet at the tomb to find all three dead. Friar Laurence recounts the story of the two «star-cross’d lovers», fulfilling the curse that Mercutio swore. The families are reconciled by their children’s deaths and agree to end their violent feud. The play ends with the Prince’s elegy for the lovers: «For never was a story of more woe / Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.»[4]

Sources

Romeo and Juliet borrows from a tradition of tragic love stories dating back to antiquity. One of these is Pyramus and Thisbe, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which contains parallels to Shakespeare’s story: the lovers’ parents despise each other, and Pyramus falsely believes his lover Thisbe is dead.[5] The Ephesiaca of Xenophon of Ephesus, written in the 3rd century, also contains several similarities to the play, including the separation of the lovers, and a potion that induces a deathlike sleep.[6]

One of the earliest references to the names Montague and Capulet is from Dante’s Divine Comedy, who mentions the Montecchi (Montagues) and the Cappelletti (Capulets) in canto six of Purgatorio:[7]

Come and see, you who are negligent,

Montagues and Capulets, Monaldi and Filippeschi

One lot already grieving, the other in fear.[8]

Masuccio Salernitano, author of Mariotto & Ganozza (1476), the earliest known version of Romeo & Juliet tale

However, the reference is part of a polemic against the moral decay of Florence, Lombardy, and the Italian Peninsula as a whole; Dante, through his characters, chastises German King Albert I for neglecting his responsibilities towards Italy («you who are negligent»), and successive popes for their encroachment from purely spiritual affairs, thus leading to a climate of incessant bickering and warfare between rival political parties in Lombardy. History records the name of the family Montague as being lent to such a political party in Verona, but that of the Capulets as from a Cremonese family, both of whom play out their conflict in Lombardy as a whole rather than within the confines of Verona.[9] Allied to rival political factions, the parties are grieving («One lot already grieving») because their endless warfare has led to the destruction of both parties,[9] rather than a grief from the loss of their ill-fated offspring as the play sets forth, which appears to be a solely poetic creation within this context.

The earliest known version of the Romeo and Juliet tale akin to Shakespeare’s play is the story of Mariotto and Ganozza by Masuccio Salernitano, in the 33rd novel of his Il Novellino published in 1476.[10] Salernitano sets the story in Siena and insists its events took place in his own lifetime. His version of the story includes the secret marriage, the colluding friar, the fray where a prominent citizen is killed, Mariotto’s exile, Ganozza’s forced marriage, the potion plot, and the crucial message that goes astray. In this version, Mariotto is caught and beheaded and Ganozza dies of grief.[11][12]

Luigi da Porto (1485–1529) adapted the story as Giulietta e Romeo[13] and included it in his Historia novellamente ritrovata di due nobili amanti (A Newly-Discovered History of two Noble Lovers), written in 1524 and published posthumously in 1531 in Venice.[14][15] Da Porto drew on Pyramus and Thisbe, Boccaccio’s Decameron, and Salernitano’s Mariotto e Ganozza, but it is likely that his story is also autobiographical: He was a soldier present at a ball on 26 February 1511, at a residence of the pro-Venice Savorgnan clan in Udine, following a peace ceremony attended by the opposing pro-Imperial Strumieri clan. There, Da Porto fell in love with Lucina, a Savorgnan daughter, but the family feud frustrated their courtship. The next morning, the Savorgnans led an attack on the city, and many members of the Strumieri were murdered. Years later, still half-paralyzed from a battle-wound, Luigi wrote Giulietta e Romeo in Montorso Vicentino (from which he could see the «castles» of Verona), dedicating the novella to the bellisima e leggiadra (the beautiful and graceful) Lucina Savorgnan.[13][16] Da Porto presented his tale as historically factual and claimed it took place at least a century earlier than Salernitano had it, in the days Verona was ruled by Bartolomeo della Scala[17] (anglicized as Prince Escalus).

Da Porto presented the narrative in close to its modern form, including the names of the lovers, the rival families of Montecchi and Capuleti (Cappelletti) and the location in Verona.[10] He named the friar Laurence (frate Lorenzo) and introduced the characters Mercutio (Marcuccio Guertio), Tybalt (Tebaldo Cappelletti), Count Paris (conte (Paride) di Lodrone), the faithful servant, and Giulietta’s nurse. Da Porto originated the remaining basic elements of the story: the feuding families, Romeo—left by his mistress—meeting Giulietta at a dance at her house, the love scenes (including the balcony scene), the periods of despair, Romeo killing Giulietta’s cousin (Tebaldo), and the families’ reconciliation after the lovers’ suicides.[18] In da Porto’s version, Romeo takes poison and Giulietta keeps her breath until she dies.[19]

In 1554, Matteo Bandello published the second volume of his Novelle, which included his version of Giuletta e Romeo,[15] probably written between 1531 and 1545. Bandello lengthened and weighed down the plot while leaving the storyline basically unchanged (though he did introduce Benvolio).[18] Bandello’s story was translated into French by Pierre Boaistuau in 1559 in the first volume of his Histories Tragiques. Boaistuau adds much moralising and sentiment, and the characters indulge in rhetorical outbursts.[20]

In his 1562 narrative poem The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet, Arthur Brooke translated Boaistuau faithfully but adjusted it to reflect parts of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde.[21] There was a trend among writers and playwrights to publish works based on Italian novelle—Italian tales were very popular among theatre-goers—and Shakespeare may well have been familiar with William Painter’s 1567 collection of Italian tales titled Palace of Pleasure.[22] This collection included a version in prose of the Romeo and Juliet story named «The goodly History of the true and constant love of Romeo and Juliett». Shakespeare took advantage of this popularity: The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure for Measure, and Romeo and Juliet are all from Italian novelle. Romeo and Juliet is a dramatization of Brooke’s translation, and Shakespeare follows the poem closely but adds detail to several major and minor characters (the Nurse and Mercutio in particular).[23][24][25]

Christopher Marlowe’s Hero and Leander and Dido, Queen of Carthage, both similar stories written in Shakespeare’s day, are thought to be less of a direct influence, although they may have helped create an atmosphere in which tragic love stories could thrive.[21]

Date and text

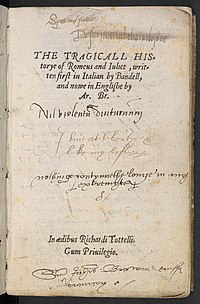

Title page of the first edition

It is unknown when exactly Shakespeare wrote Romeo and Juliet. Juliet’s Nurse refers to an earthquake she says occurred 11 years ago.[26] This may refer to the Dover Straits earthquake of 1580, which would date that particular line to 1591. Other earthquakes—both in England and in Verona—have been proposed in support of the different dates.[27] But the play’s stylistic similarities with A Midsummer Night’s Dream and other plays conventionally dated around 1594–95, place its composition sometime between 1591 and 1595.[28][b] One conjecture is that Shakespeare may have begun a draft in 1591, which he completed in 1595.[29]

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet was published in two quarto editions prior to the publication of the First Folio of 1623. These are referred to as Q1 and Q2. The first printed edition, Q1, appeared in early 1597, printed by John Danter. Because its text contains numerous differences from the later editions, it is labelled a so-called ‘bad quarto’; the 20th-century editor T. J. B. Spencer described it as «a detestable text, probably a reconstruction of the play from the imperfect memories of one or two of the actors», suggesting that it had been pirated for publication.[30] An alternative explanation for Q1’s shortcomings is that the play (like many others of the time) may have been heavily edited before performance by the playing company.[31] However, «the theory, formulated by [Alfred] Pollard,» that the ‘bad quarto’ was «reconstructed from memory by some of the actors is now under attack. Alternative theories are that some or all of ‘the bad quartos’ are early versions by Shakespeare or abbreviations made either for Shakespeare’s company or for other companies.»[32] In any event, its appearance in early 1597 makes 1596 the latest possible date for the play’s composition.[27]

The superior Q2 called the play The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet. It was printed in 1599 by Thomas Creede and published by Cuthbert Burby. Q2 is about 800 lines longer than Q1.[31] Its title page describes it as «Newly corrected, augmented and amended». Scholars believe that Q2 was based on Shakespeare’s pre-performance draft (called his foul papers) since there are textual oddities such as variable tags for characters and «false starts» for speeches that were presumably struck through by the author but erroneously preserved by the typesetter. It is a much more complete and reliable text and was reprinted in 1609 (Q3), 1622 (Q4) and 1637 (Q5).[30] In effect, all later Quartos and Folios of Romeo and Juliet are based on Q2, as are all modern editions since editors believe that any deviations from Q2 in the later editions (whether good or bad) are likely to have arisen from editors or compositors, not from Shakespeare.[31]

The First Folio text of 1623 was based primarily on Q3, with clarifications and corrections possibly coming from a theatrical prompt book or Q1.[30][33] Other Folio editions of the play were printed in 1632 (F2), 1664 (F3), and 1685 (F4).[34] Modern versions—that take into account several of the Folios and Quartos—first appeared with Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition, followed by Alexander Pope’s 1723 version. Pope began a tradition of editing the play to add information such as stage directions missing in Q2 by locating them in Q1. This tradition continued late into the Romantic period. Fully annotated editions first appeared in the Victorian period and continue to be produced today, printing the text of the play with footnotes describing the sources and culture behind the play.[35]

Themes and motifs

Scholars have found it extremely difficult to assign one specific, overarching theme to the play. Proposals for a main theme include a discovery by the characters that human beings are neither wholly good nor wholly evil, but instead are more or less alike,[36] awaking out of a dream and into reality, the danger of hasty action, or the power of tragic fate. None of these have widespread support. However, even if an overall theme cannot be found it is clear that the play is full of several small thematic elements that intertwine in complex ways. Several of those most often debated by scholars are discussed below.[37]

Love

«Romeo

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

Juliet

Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.»

—Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene V[38]

Romeo and Juliet is sometimes considered to have no unifying theme, save that of young love.[36] Romeo and Juliet have become emblematic of young lovers and doomed love. Since it is such an obvious subject of the play, several scholars have explored the language and historical context behind the romance of the play.[39]

On their first meeting, Romeo and Juliet use a form of communication recommended by many etiquette authors in Shakespeare’s day: metaphor. By using metaphors of saints and sins, Romeo was able to test Juliet’s feelings for him in a non-threatening way. This method was recommended by Baldassare Castiglione (whose works had been translated into English by this time). He pointed out that if a man used a metaphor as an invitation, the woman could pretend she did not understand him, and he could retreat without losing honour. Juliet, however, participates in the metaphor and expands on it. The religious metaphors of «shrine», «pilgrim», and «saint» were fashionable in the poetry of the time and more likely to be understood as romantic rather than blasphemous, as the concept of sainthood was associated with the Catholicism of an earlier age.[40] Later in the play, Shakespeare removes the more daring allusions to Christ’s resurrection in the tomb he found in his source work: Brooke’s Romeus and Juliet.[41]

In the later balcony scene, Shakespeare has Romeo overhear Juliet’s soliloquy, but in Brooke’s version of the story, her declaration is done alone. By bringing Romeo into the scene to eavesdrop, Shakespeare breaks from the normal sequence of courtship. Usually, a woman was required to be modest and shy to make sure that her suitor was sincere, but breaking this rule serves to speed along the plot. The lovers are able to skip courting and move on to plain talk about their relationship—agreeing to be married after knowing each other for only one night.[39] In the final suicide scene, there is a contradiction in the message—in the Catholic religion, suicides were often thought to be condemned to Hell, whereas people who die to be with their loves under the «Religion of Love» are joined with their loves in Paradise. Romeo and Juliet’s love seems to be expressing the «Religion of Love» view rather than the Catholic view. Another point is that, although their love is passionate, it is only consummated in marriage, which keeps them from losing the audience’s sympathy.[42]

The play arguably equates love and sex with death. Throughout the story, both Romeo and Juliet, along with the other characters, fantasise about it as a dark being, often equating it with a lover. Capulet, for example, when he first discovers Juliet’s (faked) death, describes it as having deflowered his daughter.[43] Juliet later erotically compares Romeo and death. Right before her suicide, she grabs Romeo’s dagger, saying «O happy dagger! This is thy sheath. There rust, and let me die.»[44][45]

Fate and chance

«O, I am fortune’s fool!»

—Romeo, Act III Scene I[46]

Scholars are divided on the role of fate in the play. No consensus exists on whether the characters are truly fated to die together or whether the events take place by a series of unlucky chances. Arguments in favour of fate often refer to the description of the lovers as «star-cross’d». This phrase seems to hint that the stars have predetermined the lovers’ future.[47] John W. Draper points out the parallels between the Elizabethan belief in the four humours and the main characters of the play (for example, Tybalt as a choleric). Interpreting the text in the light of humours reduces the amount of plot attributed to chance by modern audiences.[48] Still, other scholars see the play as a series of unlucky chances—many to such a degree that they do not see it as a tragedy at all, but an emotional melodrama.[48] Ruth Nevo believes the high degree to which chance is stressed in the narrative makes Romeo and Juliet a «lesser tragedy» of happenstance, not of character. For example, Romeo’s challenging Tybalt is not impulsive; it is, after Mercutio’s death, the expected action to take. In this scene, Nevo reads Romeo as being aware of the dangers of flouting social norms, identity, and commitments. He makes the choice to kill, not because of a tragic flaw, but because of circumstance.[49]

Duality (light and dark)

«O brawling love, O loving hate,

O any thing of nothing first create!

O heavy lightness, serious vanity,

Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms,

Feather of lead, bright smoke, cold fire, sick health,

Still-waking sleep, that is not what it is!»

—Romeo, Act I, Scene I[50]

Scholars have long noted Shakespeare’s widespread use of light and dark imagery throughout the play. Caroline Spurgeon considers the theme of light as «symbolic of the natural beauty of young love» and later critics have expanded on this interpretation.[49][51] For example, both Romeo and Juliet see the other as light in a surrounding darkness. Romeo describes Juliet as being like the sun,[52] brighter than a torch,[53] a jewel sparkling in the night,[54] and a bright angel among dark clouds.[55] Even when she lies apparently dead in the tomb, he says her «beauty makes / This vault a feasting presence full of light.»[56] Juliet describes Romeo as «day in night» and «Whiter than snow upon a raven’s back.»[57][58] This contrast of light and dark can be expanded as symbols—contrasting love and hate, youth and age in a metaphoric way.[49] Sometimes these intertwining metaphors create dramatic irony. For example, Romeo and Juliet’s love is a light in the midst of the darkness of the hate around them, but all of their activity together is done in night and darkness while all of the feuding is done in broad daylight. This paradox of imagery adds atmosphere to the moral dilemma facing the two lovers: loyalty to family or loyalty to love. At the end of the story, when the morning is gloomy and the sun hiding its face for sorrow, light and dark have returned to their proper places, the outward darkness reflecting the true, inner darkness of the family feud out of sorrow for the lovers. All characters now recognise their folly in light of recent events, and things return to the natural order, thanks to the love and death of Romeo and Juliet.[51] The «light» theme in the play is also heavily connected to the theme of time since light was a convenient way for Shakespeare to express the passage of time through descriptions of the sun, moon, and stars.[59]

Time

«These times of woe afford no time to woo.»

—Paris, Act III, Scene IV[60]

Time plays an important role in the language and plot of the play. Both Romeo and Juliet struggle to maintain an imaginary world void of time in the face of the harsh realities that surround them. For instance, when Romeo swears his love to Juliet by the moon, she protests «O swear not by the moon, th’inconstant moon, / That monthly changes in her circled orb, / Lest that thy love prove likewise variable.»[61] From the very beginning, the lovers are designated as «star-cross’d»[62][c] referring to an astrologic belief associated with time. Stars were thought to control the fates of humanity, and as time passed, stars would move along their course in the sky, also charting the course of human lives below. Romeo speaks of a foreboding he feels in the stars’ movements early in the play, and when he learns of Juliet’s death, he defies the stars’ course for him.[48][64]

Another central theme is haste: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet spans a period of four to six days, in contrast to Brooke’s poems spanning nine months.[59] Scholars such as G. Thomas Tanselle believe that time was «especially important to Shakespeare» in this play, as he used references to «short-time» for the young lovers as opposed to references to «long-time» for the «older generation» to highlight «a headlong rush towards doom».[59] Romeo and Juliet fight time to make their love last forever. In the end, the only way they seem to defeat time is through a death that makes them immortal through art.[65]

Time is also connected to the theme of light and dark. In Shakespeare’s day, plays were most often performed at noon or in the afternoon in broad daylight.[d] This forced the playwright to use words to create the illusion of day and night in his plays. Shakespeare uses references to the night and day, the stars, the moon, and the sun to create this illusion. He also has characters frequently refer to days of the week and specific hours to help the audience understand that time has passed in the story. All in all, no fewer than 103 references to time are found in the play, adding to the illusion of its passage.[66][67]

Criticism and interpretation

Critical history

The earliest known critic of the play was diarist Samuel Pepys, who wrote in 1662: «it is a play of itself the worst that I ever heard in my life.»[68] Poet John Dryden wrote 10 years later in praise of the play and its comic character Mercutio: «Shakespear show’d the best of his skill in his Mercutio, and he said himself, that he was forc’d to kill him in the third Act, to prevent being killed by him.»[68] Criticism of the play in the 18th century was less sparse but no less divided. Publisher Nicholas Rowe was the first critic to ponder the theme of the play, which he saw as the just punishment of the two feuding families. In mid-century, writer Charles Gildon and philosopher Lord Kames argued that the play was a failure in that it did not follow the classical rules of drama: the tragedy must occur because of some character flaw, not an accident of fate. Writer and critic Samuel Johnson, however, considered it one of Shakespeare’s «most pleasing» plays.[69]

In the later part of the 18th and through the 19th century, criticism centred on debates over the moral message of the play. Actor and playwright David Garrick’s 1748 adaptation excluded Rosaline: Romeo abandoning her for Juliet was seen as fickle and reckless. Critics such as Charles Dibdin argued that Rosaline had been included in the play in order to show how reckless the hero was and that this was the reason for his tragic end. Others argued that Friar Laurence might be Shakespeare’s spokesman in his warnings against undue haste. At the beginning of the 20th century, these moral arguments were disputed by critics such as Richard Green Moulton: he argued that accident, and not some character flaw, led to the lovers’ deaths.[70]

Dramatic structure

In Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare employs several dramatic techniques that have garnered praise from critics, most notably the abrupt shifts from comedy to tragedy (an example is the punning exchange between Benvolio and Mercutio just before Tybalt arrives). Before Mercutio’s death in Act III, the play is largely a comedy.[71] After his accidental demise, the play suddenly becomes serious and takes on a tragic tone. When Romeo is banished, rather than executed, and Friar Laurence offers Juliet a plan to reunite her with Romeo, the audience can still hope that all will end well. They are in a «breathless state of suspense» by the opening of the last scene in the tomb: If Romeo is delayed long enough for the Friar to arrive, he and Juliet may yet be saved.[72] These shifts from hope to despair, reprieve, and new hope serve to emphasise the tragedy when the final hope fails and both the lovers die at the end.[73]

Shakespeare also uses sub-plots to offer a clearer view of the actions of the main characters. For example, when the play begins, Romeo is in love with Rosaline, who has refused all of his advances. Romeo’s infatuation with her stands in obvious contrast to his later love for Juliet. This provides a comparison through which the audience can see the seriousness of Romeo and Juliet’s love and marriage. Paris’ love for Juliet also sets up a contrast between Juliet’s feelings for him and her feelings for Romeo. The formal language she uses around Paris, as well as the way she talks about him to her Nurse, show that her feelings clearly lie with Romeo. Beyond this, the sub-plot of the Montague–Capulet feud overarches the whole play, providing an atmosphere of hate that is the main contributor to the play’s tragic end.[73]

Language

Shakespeare uses a variety of poetic forms throughout the play. He begins with a 14-line prologue in the form of a Shakespearean sonnet, spoken by a Chorus. Most of Romeo and Juliet is, however, written in blank verse, and much of it in strict iambic pentameter, with less rhythmic variation than in most of Shakespeare’s later plays.[74] In choosing forms, Shakespeare matches the poetry to the character who uses it. Friar Laurence, for example, uses sermon and sententiae forms and the Nurse uses a unique blank verse form that closely matches colloquial speech.[74] Each of these forms is also moulded and matched to the emotion of the scene the character occupies. For example, when Romeo talks about Rosaline earlier in the play, he attempts to use the Petrarchan sonnet form. Petrarchan sonnets were often used by men to exaggerate the beauty of women who were impossible for them to attain, as in Romeo’s situation with Rosaline. This sonnet form is used by Lady Capulet to describe Count Paris to Juliet as a handsome man.[75] When Romeo and Juliet meet, the poetic form changes from the Petrarchan (which was becoming archaic in Shakespeare’s day) to a then more contemporary sonnet form, using «pilgrims» and «saints» as metaphors.[76] Finally, when the two meet on the balcony, Romeo attempts to use the sonnet form to pledge his love, but Juliet breaks it by saying «Dost thou love me?»[77] By doing this, she searches for true expression, rather than a poetic exaggeration of their love.[78] Juliet uses monosyllabic words with Romeo but uses formal language with Paris.[79] Other forms in the play include an epithalamium by Juliet, a rhapsody in Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech, and an elegy by Paris.[80] Shakespeare saves his prose style most often for the common people in the play, though at times he uses it for other characters, such as Mercutio.[81] Humour, also, is important: scholar Molly Mahood identifies at least 175 puns and wordplays in the text.[82] Many of these jokes are sexual in nature, especially those involving Mercutio and the Nurse.[83]

Psychoanalytic criticism

Early psychoanalytic critics saw the problem of Romeo and Juliet in terms of Romeo’s impulsiveness, deriving from «ill-controlled, partially disguised aggression»,[84] which leads both to Mercutio’s death and to the double suicide.[84][e] Romeo and Juliet is not considered to be exceedingly psychologically complex, and sympathetic psychoanalytic readings of the play make the tragic male experience equivalent with sicknesses.[86] Norman Holland, writing in 1966, considers Romeo’s dream[87] as a realistic «wish fulfilling fantasy both in terms of Romeo’s adult world and his hypothetical childhood at stages oral, phallic and oedipal» – while acknowledging that a dramatic character is not a human being with mental processes separate from those of the author.[88] Critics such as Julia Kristeva focus on the hatred between the families, arguing that this hatred is the cause of Romeo and Juliet’s passion for each other. That hatred manifests itself directly in the lovers’ language: Juliet, for example, speaks of «my only love sprung from my only hate»[89] and often expresses her passion through an anticipation of Romeo’s death.[90] This leads on to speculation as to the playwright’s psychology, in particular to a consideration of Shakespeare’s grief for the death of his son, Hamnet.[91]

Feminist criticism

Feminist literary critics argue that the blame for the family feud lies in Verona’s patriarchal society. For Coppélia Kahn, for example, the strict, masculine code of violence imposed on Romeo is the main force driving the tragedy to its end. When Tybalt kills Mercutio, Romeo shifts into a violent mode, regretting that Juliet has made him so «effeminate».[92] In this view, the younger males «become men» by engaging in violence on behalf of their fathers, or in the case of the servants, their masters. The feud is also linked to male virility, as the numerous jokes about maidenheads aptly demonstrate.[93][94] Juliet also submits to a female code of docility by allowing others, such as the Friar, to solve her problems for her. Other critics, such as Dympna Callaghan, look at the play’s feminism from a historicist angle, stressing that when the play was written the feudal order was being challenged by increasingly centralised government and the advent of capitalism. At the same time, emerging Puritan ideas about marriage were less concerned with the «evils of female sexuality» than those of earlier eras and more sympathetic towards love-matches: when Juliet dodges her father’s attempt to force her to marry a man she has no feeling for, she is challenging the patriarchal order in a way that would not have been possible at an earlier time.[95]

Queer theory

A number of critics have found the character of Mercutio to have unacknowledged homoerotic desire for Romeo.[96] Jonathan Goldberg examined the sexuality of Mercutio and Romeo utilising queer theory in Queering the Renaissance (1994), comparing their friendship with sexual love.[97] Mercutio, in friendly conversation, mentions Romeo’s phallus, suggesting traces of homoeroticism.[98] An example is his joking wish «To raise a spirit in his mistress’ circle … letting it there stand / Till she had laid it and conjured it down.»[99][100] Romeo’s homoeroticism can also be found in his attitude to Rosaline, a woman who is distant and unavailable and brings no hope of offspring. As Benvolio argues, she is best replaced by someone who will reciprocate. Shakespeare’s procreation sonnets describe another young man who, like Romeo, is having trouble creating offspring and who may be seen as being a homosexual. Goldberg believes that Shakespeare may have used Rosaline as a way to express homosexual problems of procreation in an acceptable way. In this view, when Juliet says «…that which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet»,[101] she may be raising the question of whether there is any difference between the beauty of a man and the beauty of a woman.[102]

The balcony scene

The balcony scene was introduced by Da Porto in 1524. He had Romeo walk frequently by her house, «sometimes climbing to her chamber window», and wrote, «It happened one night, as love ordained, when the moon shone unusually bright, that whilst Romeo was climbing the balcony, the young lady … opened the window, and looking out saw him».[103] After this they have a conversation in which they declare eternal love to each other. A few decades later, Bandello greatly expanded this scene, diverging from the familiar one: Julia has her nurse deliver a letter asking Romeo to come to her window with a rope ladder, and he climbs the balcony with the help of his servant, Julia and the nurse (the servants discreetly withdraw after this).[18]

Nevertheless, in October 2014, Lois Leveen pointed out in The Atlantic that the original Shakespeare play did not contain a balcony; it just says that Juliet appears at a window.[104] The word balcone is not known to have existed in the English language until two years after Shakespeare’s death.[105] The balcony was certainly used in Thomas Otway’s 1679 play, The History and Fall of Caius Marius, which had borrowed much of its story from Romeo and Juliet and placed the two lovers in a balcony reciting a speech similar to that between Romeo and Juliet. Leveen suggested that during the 18th century, David Garrick chose to use a balcony in his adaptation and revival of Romeo and Juliet and modern adaptations have continued this tradition.[104]

Legacy

Shakespeare’s day

Romeo and Juliet ranks with Hamlet as one of Shakespeare’s most performed plays. Its many adaptations have made it one of his most enduring and famous stories.[107] Even in Shakespeare’s lifetime, it was extremely popular. Scholar Gary Taylor measures it as the sixth most popular of Shakespeare’s plays, in the period after the death of Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Kyd but before the ascendancy of Ben Jonson during which Shakespeare was London’s dominant playwright.[108][f] The date of the first performance is unknown. The First Quarto, printed in 1597, reads «it hath been often (and with great applause) plaid publiquely», setting the first performance before that date. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men were certainly the first to perform it. Besides their strong connections with Shakespeare, the Second Quarto actually names one of its actors, Will Kemp, instead of Peter, in a line in Act V. Richard Burbage was probably the first Romeo, being the company’s actor; and Master Robert Goffe (a boy), the first Juliet.[106] The premiere is likely to have been at The Theatre, with other early productions at the Curtain.[109] Romeo and Juliet is one of the first Shakespeare plays to have been performed outside England: a shortened and simplified version was performed in Nördlingen in 1604.[110]

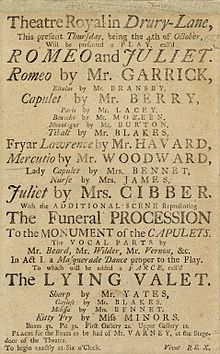

Restoration and 18th-century theatre

All theatres were closed down by the puritan government on 6 September 1642. Upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, two patent companies (the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company) were established, and the existing theatrical repertoire was divided between them.[111]

Sir William Davenant of the Duke’s Company staged a 1662 adaptation in which Henry Harris played Romeo, Thomas Betterton Mercutio, and Betterton’s wife Mary Saunderson Juliet: she was probably the first woman to play the role professionally.[112] Another version closely followed Davenant’s adaptation and was also regularly performed by the Duke’s Company. This was a tragicomedy by James Howard, in which the two lovers survive.[113]

Thomas Otway’s The History and Fall of Caius Marius, one of the more extreme of the Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare, debuted in 1680. The scene is shifted from Renaissance Verona to ancient Rome; Romeo is Marius, Juliet is Lavinia, the feud is between patricians and plebeians; Juliet/Lavinia wakes from her potion before Romeo/Marius dies. Otway’s version was a hit, and was acted for the next seventy years.[112] His innovation in the closing scene was even more enduring, and was used in adaptations throughout the next 200 years: Theophilus Cibber’s adaptation of 1744, and David Garrick’s of 1748 both used variations on it.[114] These versions also eliminated elements deemed inappropriate at the time. For example, Garrick’s version transferred all language describing Rosaline to Juliet, to heighten the idea of faithfulness and downplay the love-at-first-sight theme.[115][116] In 1750, a «Battle of the Romeos» began, with Spranger Barry and Susannah Maria Arne (Mrs. Theophilus Cibber) at Covent Garden versus David Garrick and George Anne Bellamy at Drury Lane.[117]

The earliest known production in North America was an amateur one: on 23 March 1730, a physician named Joachimus Bertrand placed an advertisement in the Gazette newspaper in New York, promoting a production in which he would play the apothecary.[118] The first professional performances of the play in North America were those of the Hallam Company.[119]

19th-century theatre

The American Cushman sisters, Charlotte and Susan, as Romeo and Juliet in 1846

Garrick’s altered version of the play was very popular, and ran for nearly a century.[112] Not until 1845 did Shakespeare’s original return to the stage in the United States with the sisters Susan and Charlotte Cushman as Juliet and Romeo, respectively,[120] and then in 1847 in Britain with Samuel Phelps at Sadler’s Wells Theatre.[121] Cushman adhered to Shakespeare’s version, beginning a string of eighty-four performances. Her portrayal of Romeo was considered genius by many. The Times wrote: «For a long time Romeo has been a convention. Miss Cushman’s Romeo is a creative, a living, breathing, animated, ardent human being.»[122][120] Queen Victoria wrote in her journal that «no-one would ever have imagined she was a woman».[123] Cushman’s success broke the Garrick tradition and paved the way for later performances to return to the original storyline.[112]

Professional performances of Shakespeare in the mid-19th century had two particular features: firstly, they were generally star vehicles, with supporting roles cut or marginalised to give greater prominence to the central characters. Secondly, they were «pictorial», placing the action on spectacular and elaborate sets (requiring lengthy pauses for scene changes) and with the frequent use of tableaux.[124] Henry Irving’s 1882 production at the Lyceum Theatre (with himself as Romeo and Ellen Terry as Juliet) is considered an archetype of the pictorial style.[125] In 1895, Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson took over from Irving and laid the groundwork for a more natural portrayal of Shakespeare that remains popular today. Forbes-Robertson avoided the showiness of Irving and instead portrayed a down-to-earth Romeo, expressing the poetic dialogue as realistic prose and avoiding melodramatic flourish.[126]

American actors began to rival their British counterparts. Edwin Booth (brother to John Wilkes Booth) and Mary McVicker (soon to be Edwin’s wife) opened as Romeo and Juliet at the sumptuous Booth’s Theatre (with its European-style stage machinery, and an air conditioning system unique in New York) on 3 February 1869. Some reports said it was one of the most elaborate productions of Romeo and Juliet ever seen in America; it was certainly the most popular, running for over six weeks and earning over $60,000 (equivalent to $1,000,000 in 2021).[127][g][h] The programme noted that: «The tragedy will be produced in strict accordance with historical propriety, in every respect, following closely the text of Shakespeare.»[i]

The first professional performance of the play in Japan may have been George Crichton Miln’s company’s production, which toured to Yokohama in 1890.[128] Throughout the 19th century, Romeo and Juliet had been Shakespeare’s most popular play, measured by the number of professional performances. In the 20th century it would become the second most popular, behind Hamlet.[129]

20th-century theatre

In 1933, the play was revived by actress Katharine Cornell and her director husband Guthrie McClintic and was taken on a seven-month nationwide tour throughout the United States. It starred Orson Welles, Brian Aherne and Basil Rathbone. The production was a modest success, and so upon the return to New York, Cornell and McClintic revised it, and for the first time the play was presented with almost all the scenes intact, including the Prologue. The new production opened on Broadway in December 1934. Critics wrote that Cornell was «the greatest Juliet of her time», «endlessly haunting», and «the most lovely and enchanting Juliet our present-day theatre has seen».[130]

John Gielgud, who was among the more famous 20th-century actors to play Romeo, Friar Laurence and Mercutio on stage

John Gielgud’s New Theatre production in 1935 featured Gielgud and Laurence Olivier as Romeo and Mercutio, exchanging roles six weeks into the run, with Peggy Ashcroft as Juliet.[131] Gielgud used a scholarly combination of Q1 and Q2 texts and organised the set and costumes to match as closely as possible the Elizabethan period. His efforts were a huge success at the box office, and set the stage for increased historical realism in later productions.[132] Olivier later compared his performance and Gielgud’s: «John, all spiritual, all spirituality, all beauty, all abstract things; and myself as all earth, blood, humanity … I’ve always felt that John missed the lower half and that made me go for the other … But whatever it was, when I was playing Romeo I was carrying a torch, I was trying to sell realism in Shakespeare.»[133]

Peter Brook’s 1947 version was the beginning of a different style of Romeo and Juliet performances. Brook was less concerned with realism, and more concerned with translating the play into a form that could communicate with the modern world. He argued, «A production is only correct at the moment of its correctness, and only good at the moment of its success.»[134] Brook excluded the final reconciliation of the families from his performance text.[135]

Throughout the century, audiences, influenced by the cinema, became less willing to accept actors distinctly older than the teenage characters they were playing.[136] A significant example of more youthful casting was in Franco Zeffirelli’s Old Vic production in 1960, with John Stride and Judi Dench, which would serve as the basis for his 1968 film.[135] Zeffirelli borrowed from Brook’s ideas, altogether removing around a third of the play’s text to make it more accessible. In an interview with The Times, he stated that the play’s «twin themes of love and the total breakdown of understanding between two generations» had contemporary relevance.[135][j]

Recent performances often set the play in the contemporary world. For example, in 1986, the Royal Shakespeare Company set the play in modern Verona. Switchblades replaced swords, feasts and balls became drug-laden rock parties, and Romeo committed suicide by hypodermic needle.

Neil Bartlett’s production of Romeo and Juliet themed the play very contemporary with a cinematic look which started its life at the Lyric Hammersmith, London then went to West Yorkshire Playhouse for an exclusive run in 1995. The cast included Emily Woof as Juliet, Stuart Bunce as Romeo, Sebastian Harcombe as Mercutio, Ashley Artus as Tybalt, Souad Faress as Lady Capulet and Silas Carson as Paris.[138] In 1997, the Folger Shakespeare Theatre produced a version set in a typical suburban world. Romeo sneaks into the Capulet barbecue to meet Juliet, and Juliet discovers Tybalt’s death while in class at school.[139]

The play is sometimes given a historical setting, enabling audiences to reflect on the underlying conflicts. For example, adaptations have been set in the midst of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict,[140] in the apartheid era in South Africa,[141] and in the aftermath of the Pueblo Revolt.[142] Similarly, Peter Ustinov’s 1956 comic adaptation, Romanoff and Juliet, is set in a fictional mid-European country in the depths of the Cold War.[143] A mock-Victorian revisionist version of Romeo and Juliet‘s final scene (with a happy ending, Romeo, Juliet, Mercutio, and Paris restored to life, and Benvolio revealing that he is Paris’s love, Benvolia, in disguise) forms part of the 1980 stage-play The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby.[144] Shakespeare’s R&J, by Joe Calarco, spins the classic in a modern tale of gay teenage awakening.[145] A recent comedic musical adaptation was The Second City’s Romeo and Juliet Musical: The People vs. Friar Laurence, the Man Who Killed Romeo and Juliet, set in modern times.[146]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Romeo and Juliet has often been the choice of Shakespeare plays to open a classical theatre company, beginning with Edwin Booth’s inaugural production of that play in his theatre in 1869, the newly re-formed company of the Old Vic in 1929 with John Gielgud, Martita Hunt, and Margaret Webster,[147] as well as the Riverside Shakespeare Company in its founding production in New York City in 1977, which used the 1968 film of Franco Zeffirelli’s production as its inspiration.[148]

21st-century theatre

In 2013, Romeo and Juliet ran on Broadway at Richard Rodgers Theatre from 19 September to 8 December for 93 regular performances after 27 previews starting on 24 August with Orlando Bloom and Condola Rashad in the starring roles.[149]

In 2018, independent theater company Stairwell Theater presented Romeo and Juliet with a basketball theme

Ballet

The best-known ballet version is Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet.[150] Originally commissioned by the Kirov Ballet, it was rejected by them when Prokofiev attempted a happy ending and was rejected again for the experimental nature of its music. It has subsequently attained an «immense» reputation, and has been choreographed by John Cranko (1962) and Kenneth MacMillan (1965) among others.[151]

In 1977, Michael Smuin’s production of one of the play’s most dramatic and impassioned dance interpretations was debuted in its entirety by San Francisco Ballet. This production was the first full-length ballet to be broadcast by the PBS series «Great Performances: Dance in America»; it aired in 1978.[152]

Dada Masilo, a South African dancer and choreographer, reinterpreted Romeo and Juliet in a new modern light. She introduced changes to the story, notably that of presenting the two families as multiracial.[153]

Music

«Romeo loved Juliet

Juliet, she felt the same

When he put his arms around her

He said Julie, baby, you’re my flame

Thou givest fever …»

—Peggy Lee’s rendition of «Fever»[154][155]

At least 24 operas have been based on Romeo and Juliet.[156] The earliest, Romeo und Julie in 1776, a Singspiel by Georg Benda, omits much of the action of the play and most of its characters and has a happy ending. It is occasionally revived. The best-known is Gounod’s 1867 Roméo et Juliette (libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré), a critical triumph when first performed and frequently revived today.[157][158] Bellini’s I Capuleti e i Montecchi is also revived from time to time, but has sometimes been judged unfavourably because of its perceived liberties with Shakespeare; however, Bellini and his librettist, Felice Romani, worked from Italian sources—principally Romani’s libretto for Giulietta e Romeo by Nicola Vaccai—rather than directly adapting Shakespeare’s play.[159] Among later operas, there is Heinrich Sutermeister’s 1940 work Romeo und Julia.[160]

Roméo et Juliette by Berlioz is a «symphonie dramatique», a large-scale work in three parts for mixed voices, chorus, and orchestra, which premiered in 1839.[161] Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Fantasy-Overture (1869, revised 1870 and 1880) is a 15-minute symphonic poem, containing the famous melody known as the «love theme».[162] Tchaikovsky’s device of repeating the same musical theme at the ball, in the balcony scene, in Juliet’s bedroom and in the tomb[163] has been used by subsequent directors: for example, Nino Rota’s love theme is used in a similar way in the 1968 film of the play, as is Des’ree’s «Kissing You» in the 1996 film.[164] Other classical composers influenced by the play include Henry Hugh Pearson (Romeo and Juliet, overture for orchestra, Op. 86), Svendsen (Romeo og Julie, 1876), Delius (A Village Romeo and Juliet, 1899–1901), Stenhammar (Romeo och Julia, 1922), and Kabalevsky (Incidental Music to Romeo and Juliet, Op. 56, 1956).[165]

The play influenced several jazz works, including Peggy Lee’s «Fever».[155] Duke Ellington’s Such Sweet Thunder contains a piece entitled «The Star-Crossed Lovers»[166] in which the pair are represented by tenor and alto saxophones: critics noted that Juliet’s sax dominates the piece, rather than offering an image of equality.[167] The play has frequently influenced popular music, including works by The Supremes, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Waits, Lou Reed,[168] and Taylor Swift.[169] The most famous such track is Dire Straits’ «Romeo and Juliet».[170]

The most famous musical theatre adaptation is West Side Story with music by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. It débuted on Broadway in 1957 and in the West End in 1958 and was twice adapted as popular films in 1961 and in 2021. This version updated the setting to mid-20th-century New York City and the warring families to ethnic gangs.[171] Other musical adaptations include Terrence Mann’s 1999 rock musical William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, co-written with Jerome Korman;[172] Gérard Presgurvic’s 2001 Roméo et Juliette, de la Haine à l’Amour; Riccardo Cocciante’s 2007 Giulietta & Romeo[173] and Johan Christher Schütz; and Johan Petterssons’s 2013 adaptation Carnival Tale (Tivolisaga), which takes place at a travelling carnival.[174]

Literature and art

Romeo and Juliet had a profound influence on subsequent literature. Before then, romance had not even been viewed as a worthy topic for tragedy.[175] In Harold Bloom’s words, Shakespeare «invented the formula that the sexual becomes the erotic when crossed by the shadow of death».[176] Of Shakespeare’s works, Romeo and Juliet has generated the most—and the most varied—adaptations, including prose and verse narratives, drama, opera, orchestral and choral music, ballet, film, television, and painting.[177][k] The word «Romeo» has even become synonymous with «male lover» in English.[178]

Romeo and Juliet was parodied in Shakespeare’s own lifetime: Henry Porter’s Two Angry Women of Abingdon (1598) and Thomas Dekker’s Blurt, Master Constable (1607) both contain balcony scenes in which a virginal heroine engages in bawdy wordplay.[179] The play directly influenced later literary works. For example, the preparations for a performance form a major plot in Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby.[180]

Romeo and Juliet is one of Shakespeare’s most-illustrated works.[181] The first known illustration was a woodcut of the tomb scene,[182] thought to be created by Elisha Kirkall, which appeared in Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of Shakespeare’s plays.[183] Five paintings of the play were commissioned for the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery in the late 18th century, one representing each of the five acts of the play.[184] Early in the 19th century, Henry Thomson painted Juliet after the Masquerade, an engraving. of which was published in The Literary Souvenir, 1828, with an accompanying poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon. The 19th-century fashion for «pictorial» performances led to directors’ drawing on paintings for their inspiration, which, in turn, influenced painters to depict actors and scenes from the theatre.[185] In the 20th century, the play’s most iconic visual images have derived from its popular film versions.[186]

David Blixt’s 2007 novel The Master Of Verona imagines the origins of the famous Capulet-Montague feud, combining the characters from Shakespeare’s Italian plays with the historical figures of Dante’s time.[187] Blixt’s subsequent novels Voice Of The Falconer (2010), Fortune’s Fool (2012), and The Prince’s Doom (2014) continue to explore the world, following the life of Mercutio as he comes of age. More tales from Blixt’s Star-Cross’d series appear in Varnished Faces: Star-Cross’d Short Stories (2015) and the plague anthology, We All Fall Down (2020). Blixt also authored Shakespeare’s Secrets: Romeo & Juliet (2018), a collection of essays on the history of Shakespeare’s play in performance, in which Blixt asserts the play is structurally not a Tragedy, but a Comedy-Gone-Wrong. In 2014 Blixt and his wife, stage director Janice L Blixt, were guests of the city of Verona, Italy for the launch of the Italian language edition of The Master Of Verona, staying with Dante’s descendants and filmmaker Anna Lerario, with whom Blixt collaborated on a film about the life of Veronese prince Cangrande della Scala.[188][189]

Lois Leveen’s 2014 novel Juliet’s Nurse imagined the fourteen years leading up to the events in the play from the point of view of the nurse. The nurse has the third largest number of lines in the original play; only the eponymous characters have more lines.[190]

The play was the subject of a 2017 General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) question by the Oxford, Cambridge and RSA Examinations board that was administered to c. 14000 students. The board attracted widespread media criticism and derision after the question appeared to confuse the Capulets and the Montagues,[191][192][193] with exams regulator Ofqual describing the error as unacceptable.[194]

Romeo and Juliet was adapted into manga format by publisher UDON Entertainment’s Manga Classics imprint and was released in May 2018.[195]

Screen

Romeo and Juliet may be the most-filmed play of all time.[196] The most notable theatrical releases were George Cukor’s multi-Oscar-nominated 1936 production, Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 version, and Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 MTV-inspired Romeo + Juliet. The latter two were both, in their time, the highest-grossing Shakespeare film ever.[197] Romeo and Juliet was first filmed in the silent era, by Georges Méliès, although his film is now lost.[196] The play was first heard on film in The Hollywood Revue of 1929, in which John Gilbert recited the balcony scene opposite Norma Shearer.[198]

Leslie Howard as Romeo and Norma Shearer as Juliet, in the 1936 MGM film directed by George Cukor

Shearer and Leslie Howard, with a combined age over 75, played the teenage lovers in George Cukor’s MGM 1936 film version. Neither critics nor the public responded enthusiastically. Cinema-goers considered the film too «arty», staying away as they had from Warner’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream a year before: leading to Hollywood abandoning the Bard for over a decade.[199] Renato Castellani won the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival for his 1954 film of Romeo and Juliet.[200] His Romeo, Laurence Harvey, was already an experienced screen actor.[201] By contrast, Susan Shentall, as Juliet, was a secretarial student who was discovered by the director in a London pub and was cast for her «pale sweet skin and honey-blonde hair».[202][l]

Stephen Orgel describes Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 Romeo and Juliet as being «full of beautiful young people, and the camera and the lush technicolour make the most of their sexual energy and good looks».[186] Zeffirelli’s teenage leads, Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey, had virtually no previous acting experience but performed capably and with great maturity.[203][204] Zeffirelli has been particularly praised,[m] for his presentation of the duel scene as bravado getting out-of-control.[206] The film courted controversy by including a nude wedding-night scene[207] while Olivia Hussey was only fifteen.[208]

Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet and its accompanying soundtrack successfully targeted the «MTV Generation»: a young audience of similar age to the story’s characters.[209] Far darker than Zeffirelli’s version, the film is set in the «crass, violent and superficial society» of Verona Beach and Sycamore Grove.[210] Leonardo DiCaprio was Romeo and Claire Danes was Juliet.

The play has been widely adapted for TV and film. In 1960, Peter Ustinov’s cold-war stage parody, Romanoff and Juliet was filmed.[143] The 1961 film West Side Story—set among New York gangs—featured the Jets as white youths, equivalent to Shakespeare’s Montagues, while the Sharks, equivalent to the Capulets, are Puerto Rican.[211] In 2006, Disney’s High School Musical made use of Romeo and Juliet‘s plot, placing the two young lovers in different high-school cliques instead of feuding families.[212] Film-makers have frequently featured characters performing scenes from Romeo and Juliet.[213][n] The conceit of dramatising Shakespeare writing Romeo and Juliet has been used several times,[214][215] including John Madden’s 1998 Shakespeare in Love, in which Shakespeare writes the play against the backdrop of his own doomed love affair.[216][217] An anime series produced by Gonzo and SKY Perfect Well Think, called Romeo x Juliet, was made in 2007 and the 2013 version is the latest English-language film based on the play. In 2013, Sanjay Leela Bhansali directed the Bollywood film Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela, a contemporary version of the play which starred Ranveer Singh and Deepika Padukone in leading roles. The film was a commercial and critical success.[218][219] In February 2014, BroadwayHD released a filmed version of the 2013 Broadway Revival of Romeo and Juliet. The production starred Orlando Bloom and Condola Rashad.[220]

Modern social media and virtual world productions

In April and May 2010, the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Mudlark Production Company presented a version of the play, entitled Such Tweet Sorrow, as an improvised, real-time series of tweets on Twitter. The production used RSC actors who engaged with the audience as well each other, performing not from a traditional script but a «Grid» developed by the Mudlark production team and writers Tim Wright and Bethan Marlow. The performers also make use of other media sites such as YouTube for pictures and video.[221]

Astronomy

Two of Uranus’s moons, Juliet and Mab, are named for the play.[222]

Scene by scene

-

Title page of the Second Quarto of Romeo and Juliet published in 1599

-

Act I prologue

-

Act I scene 1: Quarrel between Capulets and Montagues

-

Act I scene 2

-

Act I scene 3

-

Act I scene 4

-

Act I scene 5

-

Act I scene 5: Romeo’s first interview with Juliet

-

Act II prologue

-

Act II scene 3

-

Act II scene 5: Juliet intreats her nurse

-

Act II scene 6

-

Act III scene 5: Romeo takes leave of Juliet

-

Act IV scene 5: Juliet’s fake death

-

Act IV scene 5: Another depiction

-

Act V scene 3: Juliet awakes to find Romeo dead

See also

- Pyramus and Thisbe

- Lovers of Cluj-Napoca

- Lovers of Teruel

- Antony and Cleopatra

- Tristan and Iseult

- Mem and Zin

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ see § Shakespeare’s day

- ^ As well as A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Gibbons draws parallels with Love’s Labour’s Lost and Richard II.[28]

- ^ Levenson defines «star-cross’d» as «thwarted by a malign star».[63]

- ^ When performed in the central yard of an inn and in public theaters such as the Globe Theatre the only source of lighting was daylight. When performed at Court, inside the stately home of a member of the nobility and in indoor theaters such as the Blackfriars theatre candle lighting was used and plays could be performed even at night.

- ^ Halio here quotes Karl A. Menninger’s Man Against Himself (1938).[85]

- ^ The five more popular plays, in descending order, are Henry VI, Part 1, Richard III, Pericles, Hamlet and Richard II.[108]

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. «Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–». Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Booth’s Romeo and Juliet was rivalled in popularity only by his own «hundred night Hamlet» at The Winter Garden of four years before.

- ^ First page of the program for the opening night performance of Romeo and Juliet at Booth’s Theatre, 3 February 1869.

- ^ Levenson provides the quote from the 1960 interview with Zeffirelli in The Times.[137]

- ^ Levenson credits this list of genres to Stanley Wells.

- ^ Brode quotes Renato Castellani.

- ^ Brode cites Anthony West of Vogue and Mollie Panter-Downes of The New Yorker as examples.[205]

- ^ McKernan and Terris list 39 instances of uses of Romeo and Juliet, not including films of the play itself.

References

All references to Romeo and Juliet, unless otherwise specified, are taken from the Arden Shakespeare second edition (Gibbons, 1980) based on the Q2 text of 1599, with elements from Q1 of 1597.[223] Under its referencing system, which uses Roman numerals, II.ii.33 means act 2, scene 2, line 33, and a 0 in place of a scene number refers to the prologue to the act.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.i.73.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.v.115.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, IV.i.105.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, V.iii.308–309.

- ^ Halio 1998, p. 93.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, p. 33.

- ^ Moore 1930, pp. 264–77.

- ^ Higgins 1998, p. 223.

- ^ a b Higgins 1998, p. 585.

- ^ a b Hosley 1965, p. 168.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 4.

- ^ a b da Porto 1831.

- ^ Prunster 2000, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Moore 1937, pp. 38–44.

- ^ Muir 1998, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Da Porto does not specify which Bartolomeo is intended, whether Bartolomeo I (regnat 1301–1304) or Bartolomeo II (regnat 1375–1381), though the association of the former with his patronage of Dante makes him perhaps slightly more likely, given that Dante actually mentions the Cappelletti and Montecchi in his Commedia.

- ^ a b c Scarci 1993–1994.

- ^ Da Porto, Luigi. «Historia novellamente ritrovata di due nobili amanti, (A Newly-Discovered History of two Noble Lovers)».

- ^ Gibbons 1980, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Gibbons 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Keeble 1980, p. 18.

- ^ Roberts 1902, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, pp. 32, 36–37.

- ^ Levenson 2000, pp. 8–14.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.iii.23.

- ^ a b Gibbons 1980, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Gibbons 1980, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Spencer 1967, p. 284.

- ^ a b c Halio 1998, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Wells 2013.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, p. 21.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, p. ix.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Bowling 1949, pp. 208–20.

- ^ Halio 1998, p. 65.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.v.92–99.

- ^ a b Honegger 2006, pp. 73–88.

- ^ Groves 2007, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Groves 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Siegel 1961, pp. 371–92.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.v.38–42.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, V.iii.169–170.

- ^ MacKenzie 2007, pp. 22–42.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.i.138.

- ^ Evans 1950, pp. 841–65.

- ^ a b c Draper 1939, pp. 16–34.

- ^ a b c Nevo 1972, pp. 241–58.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.i.167–171.

- ^ a b Parker 1968, pp. 663–74.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.ii.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.v.42.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.v.44–45.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.ii.26–32.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.v.85–86.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.ii.17–19.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c Tanselle 1964, pp. 349–61.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.iv.8–9.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.ii.109–111.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.0.6.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Muir 2005, pp. 34–41.

- ^ Lucking 2001, pp. 115–26.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Driver 1964, pp. 363–70.

- ^ a b Scott 1987, p. 415.

- ^ Scott 1987, p. 410.

- ^ Scott 1987, pp. 411–12.

- ^ Shapiro 1964, pp. 498–501.

- ^ Bonnard 1951, pp. 319–27.

- ^ a b Halio 1998, pp. 20–30.

- ^ a b Halio 1998, p. 51.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.ii.90.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Levin 1960, pp. 3–11.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Bloom 1998, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Wells 2004, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b Halio 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Menninger 1938.

- ^ Appelbaum 1997, pp. 251–72.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, V.i.1–11.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 81, 83.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.v.137.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Halio 1998, p. 85.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.i.112.

- ^ Kahn 1977, pp. 5–22.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Levenson 2000, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Goldberg 1994.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.i.24–26.

- ^ Rubinstein 1989, p. 54.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, II.ii.43–44.

- ^ Goldberg 1994, pp. 221–27.

- ^ da Porto 1868, p. 10.

- ^ a b Leveen 2014.

- ^ OED: balcony.

- ^ a b Halio 1998, p. 97.

- ^ Halio 1998, p. ix.

- ^ a b Taylor 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 62.

- ^ Dawson 2002, p. 176.

- ^ Marsden 2002, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Halio 1998, pp. 100–02.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Marsden 2002, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Branam 1984, pp. 170–79.

- ^ Stone 1964, pp. 191–206.

- ^ Pedicord 1954, p. 14.

- ^ Morrison 2007, p. 231.

- ^ Morrison 2007, p. 232.

- ^ a b Gay 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Halliday 1964, pp. 125, 365, 420.

- ^ The Times 1845.

- ^ Potter 2001, pp. 194–95.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Schoch 2002, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 104–05.

- ^ Winter 1893, pp. 46–47, 57.

- ^ Holland 2002, pp. 202–03.

- ^ Levenson 2000, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Mosel 1978, p. 354.

- ^ Smallwood 2002, p. 102.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 105–07.

- ^ Smallwood 2002, p. 110.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 107–09.

- ^ a b c Levenson 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Holland 2001, p. 207.

- ^ The Times 1960.

- ^ Halio 1998, p. 110.

- ^ Halio 1998, pp. 110–12.

- ^ Pappe 1997, p. 63.

- ^ Quince 2000, pp. 121–25.

- ^ Munro 2016, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Howard 2000, p. 297.

- ^ Edgar 1982, p. 162.

- ^ Marks 1997.

- ^ Houlihan 2004.

- ^ Barranger 2004, p. 47.

- ^ The New York Times 1977.

- ^ Hetrick & Gans 2013.

- ^ Nestyev 1960, p. 261.

- ^ Sanders 2007, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Winn 2007.

- ^ Curnow 2010.

- ^ Buhler 2007, p. 156.

- ^ a b Sanders 2007, p. 187.

- ^ Meyer 1968, pp. 38.

- ^ Huebner 2002.

- ^ Holden 1993, p. 393.

- ^ Collins 1982, pp. 532–38.

- ^ Levi 2002.

- ^ Sanders 2007, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Stites 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.v, II.ii, III.v, V.iii.

- ^ Sanders 2007, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, I.0.6.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 187–88.

- ^ Swift 2009.

- ^ Buhler 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Sanders 2007, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Ehren 1999.

- ^ Arafay 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Review from NT: «Den fina recensionen i NT

Skriver… — Johan Christher Schütz | Facebook». Facebook. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020.

- ^ Levenson 2000, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Bloom 1998, p. 89.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 91.

- ^ OED: romeo.

- ^ Bly 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Muir 2005, pp. 352–62.

- ^ Fowler 1996, p. 111.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, V.iii.

- ^ Fowler 1996, pp. 112–13.

- ^ Fowler 1996, p. 120.

- ^ Fowler 1996, pp. 126–27.

- ^ a b Orgel 2007, p. 91.

- ^ «The Master of Verona». Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ «Biografia di David Blixt» [Biography of David Blixt]. veronaeconomia.it (in Italian). 5 May 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ «Film documentario su Cangrande, il Principe di Verona» [Documentary film on Cangrande, the Prince of Verona]. Verona-in.it (in Italian). 24 October 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Kirkus Reviews 2017.

- ^ Sabur 2017.

- ^ Marsh 2017.

- ^ Richardson 2017.

- ^ Pells 2017.

- ^ Manga Classics: Romeo and Juliet (2018) UDON Entertainment ISBN 978-1-947808-03-4

- ^ a b Brode 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 225.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 43.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Tatspaugh 2000, p. 138.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 51–25.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 218.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet, III.v.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 218–20.

- ^ Tatspaugh 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Tatspaugh 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 215–16.

- ^ Symonds 2017, p. 172.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, pp. 141–56.

- ^ Lanier 2007, p. 96.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, p. 146.

- ^ Howard 2000, p. 310.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 228.

- ^ Goyal 2013.

- ^ International Business Times 2013.

- ^ Lee 2014.

- ^ Kennedy 2010.

- ^ «Uranus Moons». NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Gibbons 1980, p. vii.

Sources

Editions of Romeo and Juliet

- Gibbons, Brian, ed. (1980). Romeo and Juliet. The Arden Shakespeare, second series. London: Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-1-903436-41-7.

- Levenson, Jill L., ed. (2000). Romeo and Juliet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281496-6.

- Spencer, T.J.B., ed. (1967). Romeo and Juliet. The New Penguin Shakespeare. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-070701-4.

Secondary sources

- Appelbaum, Robert (1997). ««Standing to the Wall»: The Pressures of Masculinity in Romeo and Juliet«. Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 48 (38): 251–72. doi:10.2307/2871016. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2871016.

- Arafay, Mireia (2005). Books in Motion: Adaptation, Adaptability, Authorship. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1957-7.

- Barranger, Milly S. (2004). Margaret Webster: A Life in the Theatre. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11390-3.

- Bloom, Harold (1998). Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-57322-120-1.

- Bly, Mary (2001). «The Legacy of Juliet’s Desire in Comedies of the Early 1600s». In Alexander, Margaret M. S; Wells, Stanley (eds.). Shakespeare and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–71. ISBN 0-521-80475-2.

- Bonnard, Georges A. (1951). «Romeo and Juliet: A Possible Significance?». Review of English Studies. II (5): 319–27. doi:10.1093/res/II.5.319.

- Bowling, Lawrence Edward (1949). «The Thematic Framework of Romeo and Juliet». PMLA. Modern Language Association of America. 64 (1): 208–20. doi:10.2307/459678. JSTOR 459678. S2CID 163454145.

- Branam, George C. (1984). «The Genesis of David Garrick’s Romeo and Juliet». Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 35 (2): 170–79. doi:10.2307/2869925. JSTOR 2869925.

- Brode, Douglas (2001). Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books. ISBN 0-425-18176-6.

- Buhler, Stephen M. (2007). «Musical Shakespeares: attending to Ophelia, Juliet, and Desdemona». In Shaughnessy, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–74. ISBN 978-0-521-60580-9.

- Collins, Michael (1982). «The Literary Background of Bellini’s I Capuleti ed i Montecchi«. Journal of the American Musicological Society. 35 (3): 532–38. doi:10.1525/jams.1982.35.3.03a00050.

- Curnow, Robyn (2 November 2010). «Dada Masilo: South African dancer who breaks the rules». CNN. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- Dawson, Anthony B. (2002). «International Shakespeare». In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–93. ISBN 978-0-521-79711-5.

- Draper, John W. (1939). «Shakespeare’s ‘Star-Crossed Lovers’«. Review of English Studies. os–XV (57): 16–34. doi:10.1093/res/os-XV.57.16.

- Driver, Tom F. (1964). «The Shakespearian Clock: Time and the Vision of Reality in Romeo and Juliet and The Tempest«. Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 15 (4): 363–70. doi:10.2307/2868094. JSTOR 2868094.

- Edgar, David (1982). The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. New York: Dramatists’ Play Service. ISBN 0-8222-0817-2.