|

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Союз Советских Социалистических Республик |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922–1991 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flag State Emblem |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь! «Workers of the world, unite!» |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Интернационал «The Internationale» (1922–1944)Государственный гимн СССР[a] «State Anthem of the Soviet Union» (1944–1991) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Soviet Union during the Cold War |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital

and largest city |

Moscow 55°45′N 37°37′E / 55.750°N 37.617°E |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Russian[b] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognised regional languages |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic groups

(1989) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

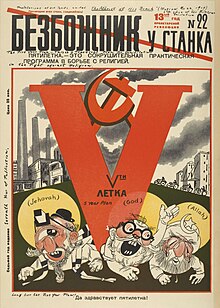

| Religion | Secular state (de jure) State atheism (de facto) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Soviet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | See also: Government of the Soviet Union

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1922–1924 |

Vladimir Lenin[c] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1924–1953 |

Joseph Stalin[d] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1953[f] |

Georgy Malenkov[e] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1953–1964 |

Nikita Khrushchev[g] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1964–1982 |

Leonid Brezhnev[h] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1982–1984 |

Yuri Andropov | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1984–1985 |

Konstantin Chernenko | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1985–1991 |

Mikhail Gorbachev[i] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of state | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1922–1946 (first) |

Mikhail Kalinin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1988–1991 (last) |

Mikhail Gorbachev | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head of government | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1922–1924 (first) |

Vladimir Lenin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1991 (last) |

Ivan Silayev | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Congress of Soviets (1922–1936)[j] Supreme Soviet (1936–1991) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Upper house |

Soviet of Nationalities (1936–1991) Soviet of Republics (1991) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Lower house |

Soviet of the Union (1936–1991) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period • World War II • Cold War | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• October Revolution |

7 November 1917 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Creation |

30 December 1922 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• End of Russian Civil War |

16 June 1923 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• First constitution |

31 January 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Second constitution |

5 December 1936 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Westward expansion |

1939–1940 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Great Patriotic War |

1941–1945 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Foundation of the UN |

24 October 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• De-Stalinization |

25 February 1956 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Last constitution |

9 October 1977 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Secession of Lithuania |

11 March 1990 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• August Coup |

19–22 August 1991 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Belovezh Accords |

8 December 1991[k] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Dissolution |

26 December 1991[l] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total |

22,402,200 km2 (8,649,500 sq mi) (1st) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Water |

2,767,198 km2 (1,068,421 sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Water (%) |

12.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1989 census |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Density |

12.7/km2 (32.9/sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 1990 estimate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total |

$2.7 trillion[6] (2nd) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Per capita |

$9,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 1990 estimate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total |

$2.7 trillion[6] (2nd) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Per capita |

$9,000 (28th) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gini (1989) | 0.275 low |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (1990 formula) | 0.920[7] very high |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Soviet ruble (Rbl) (SUR) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | (UTC+2 to +12) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Driving side | right | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | +7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | SU | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .su[m] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Soviet Union,[n] officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics[o] (USSR),[p] was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national republics;[q] in practice, both its government and its economy were highly centralized until its final years. It was a one-party state governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, with the city of Moscow serving as its capital as well as that of its largest and most populous republic: the Russian SFSR. Other major cities included Leningrad (Russian SFSR), Kiev (Ukrainian SSR), Minsk (Byelorussian SSR), Tashkent (Uzbek SSR), Alma-Ata (Kazakh SSR), and Novosibirsk (Russian SFSR). It was the largest country in the world, covering over 22,402,200 square kilometres (8,649,500 sq mi) and spanning eleven time zones.

The country’s roots lay in the October Revolution of 1917, when the Bolsheviks, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Russian Provisional Government that had earlier replaced the House of Romanov of the Russian Empire. The Bolshevik coup led to the establishment of the Russian Soviet Republic, the world’s first constitutionally guaranteed socialist state.[r] Persisting internal tensions escalated into the Russian Civil War. By 1922 the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin had emerged victorious, forming the Soviet Union. Following Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin came to power.[8] Stalin inaugurated a period of rapid industrialization and forced collectivization that led to significant economic growth, but also contributed to a famine in 1930–1933 that killed millions. The labour camp system of the Gulag was also expanded in this period. Stalin conducted the Great Purge to remove his actual and perceived opponents. After the outbreak of World War II, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The combined Soviet civilian and military casualty count—estimated to be around 27 million people—accounted for the majority of losses of Allied forces. In the aftermath of World War II, the territory taken by the Red Army formed various Soviet satellite states.

The beginning of the Cold War saw the Eastern Bloc of the Soviet Union confront the Western Bloc of the United States, with the latter grouping becoming largely united in 1949 under NATO and the former grouping becoming largely united in 1955 under the Warsaw Pact. Following Stalin’s death in 1953, a period known as de-Stalinization occurred under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev. The Soviets took an early lead in the Space Race with the first artificial satellite, the first human spaceflight, and the first probe to land on another planet (Venus). In the 1970s, there was a brief détente in the Soviet Union’s relationship with the United States, but tensions resumed following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. In the mid-1980s, the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, sought to reform the country through his policies of glasnost and perestroika. In 1989, during the closing stages of the Cold War, various countries of the Warsaw Pact overthrew their Marxist–Leninist regimes, which was accompanied by the outbreak of strong nationalist and separatist movements across the entire Soviet Union. In 1991, Gorbachev initiated a national referendum—boycotted by the Soviet republics of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova—that resulted in the majority of participating citizens voting in favour of preserving the country as a renewed federation. In August 1991, hardline members of the Communist Party staged a coup d’état against Gorbachev; the attempt failed, with Boris Yeltsin playing a high-profile role in facing down the unrest, and the Communist Party was subsequently banned. All of the republics emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union as fully independent post-Soviet states.

The Soviet Union produced many significant social and technological achievements and innovations. It had the world’s second-largest economy, and the Soviet Armed Forces comprised the largest standing military in the world.[6][9][10] An NPT-designated state, it possessed the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons in the world. It was a founding member of the United Nations as well as one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Before the dissolution, the country had maintained its status as one of the world’s two superpowers through its hegemony in Eastern Europe, military and economic strengths, aid to developing countries, and scientific research.[11]

Etymology

The word soviet is derived from the Russian word sovet (Russian: совет), meaning ‘council’, ‘assembly’, ‘advice’,[s] ultimately deriving from the proto-Slavic verbal stem of *vět-iti (‘to inform’), related to Slavic věst (‘news’), English wise, the root in ad-vis-or (which came to English through French), or the Dutch weten (‘to know’; compare wetenschap meaning ‘science’). The word sovietnik means ‘councillor’.[12] Some organizations in Russian history were called council (Russian: совет). In the Russian Empire, the State Council which functioned from 1810 to 1917 was referred to as a Council of Ministers.[12]

The Soviets as workers’ councils first appeared during the Russian revolution of 1905.[13][14] Although they were quickly suppressed by the imperial army, after the February revolution of 1917, workers’ and soldiers’ Soviets emerged throughout the country, and shared power with the Russian Provisional Government.[13][15] The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, demanded that all power be transferred to the Soviets, and gained support from the workers and soldiers.[16] After the October coup of 1917, where they seized power from the Provisional Government in the name of the Soviets,[15][17] Lenin proclaimed the formation of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (RSFSR).[18]

During the Georgian Affair of 1922, Lenin called for the RSFSR and other national Soviet republics to form a greater union which he initially named as the Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia (Russian: Союз Советских Республик Европы и Азии, tr. Soyuz Sovetskikh Respublik Evropy i Azii).[19] Joseph Stalin initially resisted Lenin’s proposal but ultimately accepted it, although with Lenin’s agreement changed the name to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), although all the republics began as socialist soviet and did not change to the other order until 1936. In addition, in the national languages of several republics, the word council or conciliar in the respective language was only quite late changed to an adaptation of the Russian soviet and never in others, e.g. Ukrainian SSR.

СССР (in the Latin alphabet: SSSR) is the abbreviation of the Russian language cognate of USSR, as written in Cyrillic letters. The Soviets used this abbreviation so frequently that audiences worldwide became familiar with its meaning. After this, the most common Russian initialization is Союз ССР (transliteration: Soyuz SSR) which, after compensating for grammatical differences, essentially translates to Union of SSRs in English. In addition, the Russian short form name Советский Союз (transliteration: Sovetskiy Soyuz, which literally means Soviet Union) is also commonly used, but only in its unabbreviated form. Since the start of the Great Patriotic War at the latest, abbreviating the Russian name of the Soviet Union as СС (in the same way as, for example, United States is abbreviated into US) has been complete taboo, the reason being that СС as a Russian Cyrillic abbreviation is instead associated with the infamous Schutzstaffel of Nazi Germany, just as SS is in English. One apparent exception was the Russian abbreviation the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, КПСС (KPSS).

In English language media, the state was referred to as the Soviet Union or the USSR. In other European languages, the locally translated short forms and abbreviations are usually used such as Union soviétique and URSS in French, or Sowjetunion and UdSSR in German. In the English-speaking world, the Soviet Union was also informally called Russia and its citizens Russians,[20] although that was technically incorrect since Russia was only one of the republics of the USSR.[21] Such misapplications of the linguistic equivalents to the term Russia and its derivatives were frequent in other languages as well.

Geography

The Soviet Union covered an area of over 22,402,200 square kilometres (8,649,500 sq mi), and was the world’s largest country,[22] a status that is retained by its successor state, Russia.[23] It covered a sixth of Earth’s land surface, and its size was comparable to the continent of North America.[24] Its western part in Europe accounted for a quarter of the country’s area and was the cultural and economic center. The eastern part in Asia extended to the Pacific Ocean to the east and Afghanistan to the south, and, except some areas in Central Asia, was much less populous. It spanned over 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi) east to west across eleven time zones, and over 7,200 kilometres (4,500 mi) north to south. It had five climate zones: tundra, taiga, steppes, desert and mountains.

The Soviet Union, similarly to Russia, had the world’s longest border, measuring over 60,000 kilometres (37,000 mi), or 1+1⁄2 circumferences of Earth. Two-thirds of it was a coastline. The country bordered (from 1945 to 1991): Norway, Finland, the Baltic Sea, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, the Black Sea, Turkey, Iran, the Caspian Sea, Afghanistan, China, Mongolia, and North Korea. The Bering Strait separated the country from the United States, while the La Pérouse Strait separated it from Japan.

The Soviet Union’s highest mountain was Communism Peak (now Ismoil Somoni Peak) in Tajik SSR, at 7,495 metres (24,590 ft). It also included most of the world’s largest lakes; the Caspian Sea (shared with Iran), and Lake Baikal in Russia, the world’s largest and deepest freshwater lake.

History

Revolution and foundation (1917–1927)

Modern revolutionary activity in the Russian Empire began with the 1825 Decembrist revolt. Although serfdom was abolished in 1861, it was done on terms unfavourable to the peasants and served to encourage revolutionaries. A parliament—the State Duma—was established in 1906 after the Russian Revolution of 1905, but Tsar Nicholas II resisted attempts to move from absolute to a constitutional monarchy. Social unrest continued and was aggravated during World War I by military defeat and food shortages in major cities.

A spontaneous popular demonstration in Petrograd on 8 March 1917, demanding peace and bread, culminated in the February Revolution and the toppling of Nicholas II and the imperial government.[25] The tsarist autocracy was replaced by the Russian Provisional Government, which intended to conduct elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and to continue fighting on the side of the Entente in World War I. At the same time, workers’ councils, known in Russian as ‘Soviets’, sprang up across the country, and the most influential of them, the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, shared power with the Provisional Government.[14][15]

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, pushed for socialist revolution in the Soviets and on the streets, adopting the slogan of “All Power to the Soviets” and urging the overthrow of the Provisional Government.[26][27] On 7 November 1917, Bolshevik Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace in Petrograd, arresting the Provisional Government leaders and Lenin declared that all power was now transferred to the Soviets.[17][15] This event would later be officially known in Soviet bibliographies as the Great October Socialist Revolution. In December, the Bolsheviks signed an armistice with the Central Powers, though by February 1918, fighting had resumed. In March, the Soviets ended involvement in the war and signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

A long and bloody Civil War ensued between the Reds and the Whites, starting in 1917 and ending in 1923 with the Reds’ victory. It included foreign intervention, the execution of the former tsar and his family, and the famine of 1921, which killed about five million people.[28] In March 1921, during a related conflict with Poland, the Peace of Riga was signed, splitting disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between the Republic of Poland and Soviet Russia. Soviet Russia had to resolve similar conflicts with the newly established republics of Estonia, Finland, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Treaty on the Creation of the USSR

On 28 December 1922, a conference of plenipotentiary delegations from the Russian SFSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR, the Ukrainian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR approved the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR[29] and the Declaration of the Creation of the USSR, forming the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.[30] These two documents were confirmed by the first Congress of Soviets of the USSR and signed by the heads of the delegations,[31] Mikhail Kalinin, Mikhail Tskhakaya, Mikhail Frunze, Grigory Petrovsky, and Alexander Chervyakov,[32] on 30 December 1922. The formal proclamation was made from the stage of the Bolshoi Theatre.

An intensive restructuring of the economy, industry and politics of the country began in the early days of Soviet power in 1917. A large part of this was done according to the Bolshevik Initial Decrees, government documents signed by Vladimir Lenin. One of the most prominent breakthroughs was the GOELRO plan, which envisioned a major restructuring of the Soviet economy based on total electrification of the country.[33] The plan became the prototype for subsequent Five-Year Plans and was fulfilled by 1931.[34] After the economic policy of ‘War communism’ during the Russian Civil War, as a prelude to fully developing socialism in the country, the Soviet government permitted some private enterprise to coexist alongside nationalized industry in the 1920s, and total food requisition in the countryside was replaced by a food tax.

From its creation, the government in the Soviet Union was based on the one-party rule of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks).[t] The stated purpose was to prevent the return of capitalist exploitation, and that the principles of democratic centralism would be the most effective in representing the people’s will in a practical manner. The debate over the future of the economy provided the background for a power struggle in the years after Lenin’s death in 1924. Initially, Lenin was to be replaced by a ‘troika’ consisting of Grigory Zinoviev of the Ukrainian SSR, Lev Kamenev of the Russian SFSR, and Joseph Stalin of the Transcaucasian SFSR.

On 1 February 1924, the USSR was recognized by the United Kingdom. The same year, a Soviet Constitution was approved, legitimizing the December 1922 union.

According to Archie Brown the constitution was never an accurate guide to political reality in the USSR. For example the fact that the Party played the leading role in making and enforcing policy was not mentioned in it until 1977.[35] The USSR was a federative entity of many constituent republics, each with its own political and administrative entities. However, the term ‘Soviet Russia’ – strictly applicable only to the Russian Federative Socialist Republic – was often applied to the entire country by non-Soviet writers.

Stalin era (1927–1953)

On 3 April 1922, Stalin was named the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Lenin had appointed Stalin the head of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate, which gave Stalin considerable power. By gradually consolidating his influence and isolating and outmaneuvering his rivals within the party, Stalin became the undisputed leader of the country and, by the end of the 1920s, established a totalitarian rule. In October 1927, Zinoviev and Leon Trotsky were expelled from the Central Committee and forced into exile.

In 1928, Stalin introduced the first five-year plan for building a socialist economy. In place of the internationalism expressed by Lenin throughout the Revolution, it aimed to build Socialism in One Country. In industry, the state assumed control over all existing enterprises and undertook an intensive program of industrialization. In agriculture, rather than adhering to the ‘lead by example’ policy advocated by Lenin,[38] forced collectivization of farms was implemented all over the country.

Famines ensued as a result, causing deaths estimated at three to seven million; surviving kulaks were persecuted, and many were sent to Gulags to do forced labor.[39][40] Social upheaval continued in the mid-1930s. Despite the turmoil of the mid-to-late 1930s, the country developed a robust industrial economy in the years preceding World War II.

Closer cooperation between the USSR and the West developed in the early 1930s. From 1932 to 1934, the country participated in the World Disarmament Conference. In 1933, diplomatic relations between the United States and the USSR were established when in November, the newly elected President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, chose to recognize Stalin’s Communist government formally and negotiated a new trade agreement between the two countries.[41] In September 1934, the country joined the League of Nations. After the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, the USSR actively supported the Republican forces against the Nationalists, who were supported by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.[42]

In December 1936, Stalin unveiled a new constitution that was praised by supporters around the world as the most democratic constitution imaginable, though there was some skepticism.[u] Stalin’s Great Purge resulted in the detainment or execution of many ‘Old Bolsheviks’ who had participated in the October Revolution with Lenin. According to declassified Soviet archives, the NKVD arrested more than one and a half million people in 1937 and 1938, of whom 681,692 were shot.[44] Over those two years, there were an average of over one thousand executions a day.[45][v]

In 1939, after attempts to form a military alliance with Britain and France against Germany failed, the Soviet Union made a dramatic shift towards Nazi Germany.[49] Almost a year after Britain and France had concluded the Munich Agreement with Germany, the Soviet Union made agreements with Germany as well, both militarily and economically during extensive talks. The two countries concluded the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and the on 23 August 1939. The former made possible the Soviet occupation of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and eastern Poland.

On 1 September, Germany invaded Poland and on the 17th the Soviet Union invaded Poland as well. On 6 October, Poland fell and part of the Soviet occupation zone was then handed over to Germany.

On 10 October, the Soviet Union and Lithuania signed an agreement whereby the Soviet Union transferred Polish sovereignty over the Vilna region to Lithuania, and on 28 October the boundary between the Soviet occupation zone and the new territory of Lithuania was officially demarcated.

On 1 November, the Soviet Union annexed Western Ukraine, followed by Western Belarus on the 2nd.

In late November, unable to coerce the Republic of Finland by diplomatic means into moving its border 25 kilometres (16 mi) back from Leningrad, Stalin ordered the invasion of Finland. On 14 December 1939, the Soviet Union was expelled from the League of Nations for invading Finland.[50] In the east, the Soviet military won several decisive victories during border clashes with the Empire of Japan in 1938 and 1939. However, in April 1941, the USSR signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact with Japan, recognizing the territorial integrity of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state.

World War II

The Battle of Stalingrad, considered by many historians as a decisive turning point of World War II.

Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 starting what was known in the USSR as the Great Patriotic War. The Red Army stopped the seemingly invincible German Army at the Battle of Moscow. The Battle of Stalingrad, which lasted from late 1942 to early 1943, dealt a severe blow to Germany from which they never fully recovered and became a turning point in the war. After Stalingrad, Soviet forces drove through Eastern Europe to Berlin before Germany surrendered in 1945. The German Army suffered 80% of its military deaths in the Eastern Front.[51] Harry Hopkins, a close foreign policy advisor to Franklin D. Roosevelt, spoke on 10 August 1943 of the USSR’s decisive role in the war.[w]

In the same year, the USSR, in fulfilment of its agreement with the Allies at the Yalta Conference, denounced the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact in April 1945[53] and invaded Manchukuo and other Japan-controlled territories on 9 August 1945.[54] This conflict ended with a decisive Soviet victory, contributing to the unconditional surrender of Japan and the end of World War II.

The USSR suffered greatly in the war, losing around 27 million people.[46] Approximately 2.8 million Soviet POWs died of starvation, mistreatment, or executions in just eight months of 1941–42.[55][56] During the war, the country together with the United States, the United Kingdom and China were considered the Big Four Allied powers,[57] and later became the Four Policemen that formed the basis of the United Nations Security Council.[58] It emerged as a superpower in the post-war period. Once denied diplomatic recognition by the Western world, the USSR had official relations with practically every country by the late 1940s. A member of the United Nations at its foundation in 1945, the country became one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, which gave it the right to veto any of its resolutions.

Cold War

Map showing greatest territorial extent of the Soviet Union and the states that it dominated politically, economically and militarily in 1960, after the Cuban Revolution of 1959 but before the official Sino-Soviet split of 1961 (total area: c. 35,000,000 km2)[x]

During the immediate post-war period, the Soviet Union rebuilt and expanded its economy, while maintaining its strictly centralized control. It took effective control over most of the countries of Eastern Europe (except Yugoslavia and later Albania), turning them into satellite states. The USSR bound its satellite states in a military alliance, the Warsaw Pact, in 1955, and an economic organization, Council for Mutual Economic Assistance or Comecon, a counterpart to the European Economic Community (EEC), from 1949 to 1991.[59] The USSR concentrated on its own recovery, seizing and transferring most of Germany’s industrial plants, and it exacted war reparations from East Germany, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria using Soviet-dominated joint enterprises. It also instituted trading arrangements deliberately designed to favour the country. Moscow controlled the Communist parties that ruled the satellite states, and they followed orders from the Kremlin.[y] Later, the Comecon supplied aid to the eventually victorious Chinese Communist Party, and its influence grew elsewhere in the world. Fearing its ambitions, the Soviet Union’s wartime allies, the United Kingdom and the United States, became its enemies. In the ensuing Cold War, the two sides clashed indirectly in proxy wars.

De-Stalinization and Khrushchev Thaw (1953–1964)

Stalin died on 5 March 1953. Without a mutually agreeable successor, the highest Communist Party officials initially opted to rule the Soviet Union jointly through a troika headed by Georgy Malenkov. This did not last, however, and Nikita Khrushchev eventually won the ensuing power struggle by the mid-1950s. In 1956, he denounced Joseph Stalin and proceeded to ease controls over the party and society. This was known as de-Stalinization.

Moscow considered Eastern Europe to be a critically vital buffer zone for the forward defence of its western borders, in case of another major invasion such as the German invasion of 1941. For this reason, the USSR sought to cement its control of the region by transforming the Eastern European countries into satellite states, dependent upon and subservient to its leadership. As a result, Soviet military forces were used to suppress an anti-communist uprising in Hungary in 1956.

In the late 1950s, a confrontation with China regarding the Soviet rapprochement with the West, and what Mao Zedong perceived as Khrushchev’s revisionism, led to the Sino–Soviet split. This resulted in a break throughout the global Marxist–Leninist movement, with the governments in Albania, Cambodia and Somalia choosing to ally with China.

During this period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, the USSR continued to realize scientific and technological exploits in the Space Race, rivaling the United States: launching the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1 in 1957; a living dog named Laika in 1957; the first human being, Yuri Gagarin in 1961; the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova in 1963; Alexei Leonov, the first person to walk in space in 1965; the first soft landing on the Moon by spacecraft Luna 9 in 1966; and the first Moon rovers, Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2.[61]

Khrushchev initiated ‘The Thaw’, a complex shift in political, cultural and economic life in the country. This included some openness and contact with other nations and new social and economic policies with more emphasis on commodity goods, allowing a dramatic rise in living standards while maintaining high levels of economic growth. Censorship was relaxed as well. Khrushchev’s reforms in agriculture and administration, however, were generally unproductive. In 1962, he precipitated a crisis with the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. An agreement was made with the United States to remove nuclear missiles from both Cuba and Turkey, concluding the crisis. This event caused Khrushchev much embarrassment and loss of prestige, resulting in his removal from power in 1964.

Era of Stagnation (1964–1985)

Following the ousting of Khrushchev, another period of collective leadership ensued, consisting of Leonid Brezhnev as general secretary, Alexei Kosygin as Premier and Nikolai Podgorny as Chairman of the Presidium, lasting until Brezhnev established himself in the early 1970s as the preeminent Soviet leader.

In 1968, the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact allies invaded Czechoslovakia to halt the Prague Spring reforms. In the aftermath, Brezhnev justified the invasion and previous military interventions as well as any potential military interventions in the future by introducing the Brezhnev Doctrine, which proclaimed any threat to socialist rule in a Warsaw Pact state as a threat to all Warsaw Pact states, therefore justifying military intervention.

Brezhnev presided throughout détente with the West that resulted in treaties on armament control (SALT I, SALT II, Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty) while at the same time building up Soviet military might.

In October 1977, the third Soviet Constitution was unanimously adopted. The prevailing mood of the Soviet leadership at the time of Brezhnev’s death in 1982 was one of aversion to change. The long period of Brezhnev’s rule had come to be dubbed one of ‘standstill’, with an ageing and ossified top political leadership. This period is also known as the Era of Stagnation, a period of adverse economic, political, and social effects in the country, which began during the rule of Brezhnev and continued under his successors Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko.

In late 1979, the Soviet Union’s military intervened in the ongoing civil war in neighboring Afghanistan, effectively ending a détente with the West.

Perestroika and Glasnost reforms (1985–1991)

Two developments dominated the decade that followed: the increasingly apparent crumbling of the Soviet Union’s economic and political structures, and the patchwork attempts at reforms to reverse that process. Kenneth S. Deffeyes argued in Beyond Oil that the Reagan administration encouraged Saudi Arabia to lower the price of oil to the point where the Soviets could not make a profit selling their oil, and resulted in the depletion of the country’s hard currency reserves.[62]

Brezhnev’s next two successors, transitional figures with deep roots in his tradition, did not last long. Yuri Andropov was 68 years old and Konstantin Chernenko 72 when they assumed power; both died in less than two years. In an attempt to avoid a third short-lived leader, in 1985, the Soviets turned to the next generation and selected Mikhail Gorbachev. He made significant changes in the economy and party leadership, called perestroika. His policy of glasnost freed public access to information after decades of heavy government censorship. Gorbachev also moved to end the Cold War. In 1988, the USSR abandoned its war in Afghanistan and began to withdraw its forces. In the following year, Gorbachev refused to interfere in the internal affairs of the Soviet satellite states, which paved the way for the Revolutions of 1989. In particular, the standstill of the Soviet Union at the Pan-European Picnic in August 1989 then set a peaceful chain reaction in motion at the end of which the Eastern Bloc collapsed. With the tearing down of the Berlin Wall and with East and West Germany pursuing unification, the Iron Curtain between the West and Soviet-controlled regions came down.[63][64][65][66]

At the same time, the Soviet republics started legal moves towards potentially declaring sovereignty over their territories, citing the freedom to secede in Article 72 of the USSR constitution.[67] On 7 April 1990, a law was passed allowing a republic to secede if more than two-thirds of its residents voted for it in a referendum.[68] Many held their first free elections in the Soviet era for their own national legislatures in 1990. Many of these legislatures proceeded to produce legislation contradicting the Union laws in what was known as the ‘War of Laws’. In 1989, the Russian SFSR convened a newly elected Congress of People’s Deputies. Boris Yeltsin was elected its chairman. On 12 June 1990, the Congress declared Russia’s sovereignty over its territory and proceeded to pass laws that attempted to supersede some of the Soviet laws. After a landslide victory of Sąjūdis in Lithuania, that country declared its independence restored on 11 March 1990.

A referendum for the preservation of the USSR was held on 17 March 1991 in nine republics (the remainder having boycotted the vote), with the majority of the population in those republics voting for preservation of the Union. The referendum gave Gorbachev a minor boost. In the summer of 1991, the New Union Treaty, which would have turned the country into a much looser Union, was agreed upon by eight republics. The signing of the treaty, however, was interrupted by the August Coup—an attempted coup d’état by hardline members of the government and the KGB who sought to reverse Gorbachev’s reforms and reassert the central government’s control over the republics. After the coup collapsed, Yeltsin was seen as a hero for his decisive actions, while Gorbachev’s power was effectively ended. The balance of power tipped significantly towards the republics. In August 1991, Latvia and Estonia immediately declared the restoration of their full independence (following Lithuania’s 1990 example). Gorbachev resigned as general secretary in late August, and soon afterwards, the party’s activities were indefinitely suspended—effectively ending its rule. By the fall, Gorbachev could no longer influence events outside Moscow, and he was being challenged even there by Yeltsin, who had been elected President of Russia in July 1991.

Dissolution and aftermath

Changes in national boundaries after the end of the Cold War

Internally displaced Azerbaijanis from Nagorno-Karabakh, 1993

Country emblems of the Soviet Republics before and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union (note that the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (fifth in the second row) no longer exists as a political entity of any kind and the emblem is unofficial)

The remaining 12 republics continued discussing new, increasingly looser, models of the Union. However, by December all except Russia and Kazakhstan had formally declared independence. During this time, Yeltsin took over what remained of the Soviet government, including the Moscow Kremlin. The final blow was struck on 1 December when Ukraine, the second-most powerful republic, voted overwhelmingly for independence. Ukraine’s secession ended any realistic chance of the country staying together even on a limited scale.

On 8 December 1991, the presidents of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (formerly Byelorussia), signed the Belavezha Accords, which declared the Soviet Union dissolved and established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in its place. While doubts remained over the authority of the accords to do this, on 21 December 1991, the representatives of all Soviet republics except Georgia signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, which confirmed the accords. On 25 December 1991, Gorbachev resigned as the President of the USSR, declaring the office extinct. He turned the powers that had been vested in the presidency over to Yeltsin. That night, the Soviet flag was lowered for the last time, and the Russian tricolour was raised in its place.

The following day, the Supreme Soviet, the highest governmental body, voted both itself and the country out of existence. This is generally recognized as marking the official, final dissolution of the Soviet Union as a functioning state, and the end of the Cold War.[69] The Soviet Army initially remained under overall CIS command but was soon absorbed into the different military forces of the newly independent states. The few remaining Soviet institutions that had not been taken over by Russia ceased to function by the end of 1991.

Following the dissolution, Russia was internationally recognized[70] as its legal successor on the international stage. To that end, Russia voluntarily accepted all Soviet foreign debt and claimed Soviet overseas properties as its own. Under the 1992 Lisbon Protocol, Russia also agreed to receive all nuclear weapons remaining in the territory of other former Soviet republics. Since then, the Russian Federation has assumed the Soviet Union’s rights and obligations. Ukraine has refused to recognize exclusive Russian claims to succession of the USSR and claimed such status for Ukraine as well, which was codified in Articles 7 and 8 of its 1991 law On Legal Succession of Ukraine. Since its independence in 1991, Ukraine has continued to pursue claims against Russia in foreign courts, seeking to recover its share of the foreign property that was owned by the USSR.

The dissolution was followed by a severe drop in economic and social conditions in post-Soviet states,[71][72] including a rapid increase in poverty,[73][74][75][76] crime,[77] corruption,[78][79] unemployment,[80] homelessness,[81][82] rates of disease,[83][84][85] infant mortality and domestic violence,[86] as well as demographic losses,[87] income inequality and the rise of an oligarchical class,[88][73] along with decreases in calorie intake, life expectancy, adult literacy, and income.[89] Between 1988 and 1989 and 1993–1995, the Gini ratio increased by an average of 9 points for all former socialist countries.[73] The economic shocks that accompanied wholesale privatization were associated with sharp increases in mortality.[90] Data shows Russia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia saw a tripling of unemployment and a 42% increase in male death rates between 1991 and 1994.[91][92] In the following decades, only five or six of the post-communist states are on a path to joining the wealthy capitalist West while most are falling behind, some to such an extent that it will take over fifty years to catch up to where they were before the fall of the Soviet Bloc.[93][94]

In summing up the international ramifications of these events, Vladislav Zubok stated: ‘The collapse of the Soviet empire was an event of epochal geopolitical, military, ideological, and economic significance.’[95] Before the dissolution, the country had maintained its status as one of the world’s two superpowers for four decades after World War II through its hegemony in Eastern Europe, military strength, economic strength, aid to developing countries, and scientific research, especially in space technology and weaponry.[11]

Post-Soviet states

The analysis of the succession of states for the 15 post-Soviet states is complex. The Russian Federation is seen as the legal continuator state and is for most purposes the heir to the Soviet Union. It retained ownership of all former Soviet embassy properties, and also inherited the Soviet Union’s UN membership, with its permanent seat on the Security Council.

Of the two other co-founding states of the USSR at the time of the dissolution, Ukraine was the only one that had passed laws, similar to Russia, that it is a state-successor of both the Ukrainian SSR and the USSR.[96] Soviet treaties laid groundwork for Ukraine’s future foreign agreements as well as they led to Ukraine agreeing to undertake 16.37% of debts of the Soviet Union for which it was going to receive its share of USSR’s foreign property. Although it had a tough position at the time, due to Russia’s position as a ‘single continuation of the USSR’ that became widely accepted in the West as well as a constant pressure from the Western countries, allowed Russia to dispose state property of USSR abroad and conceal information about it. Due to that Ukraine never ratified ‘zero option’ agreement that Russian Federation had signed with other former Soviet republics, as it denied disclosing of information about Soviet Gold Reserves and its Diamond Fund.[97][98] The dispute over former Soviet property and assets between the two former republics is still ongoing:

The conflict is unsolvable. We can continue to poke Kiev handouts in the calculation of ‘solve the problem’, only it won’t be solved. Going to a trial is also pointless: for a number of European countries this is a political issue, and they will make a decision clearly in whose favor. What to do in this situation is an open question. Search for non-trivial solutions. But we must remember that in 2014, with the filing of the then Ukrainian Prime Minister Yatsenyuk, litigation with Russia resumed in 32 countries.

Similar situation occurred with restitution of cultural property. Although on 14 February 1992 Russia and other former Soviet republics signed agreement ‘On the return of cultural and historic property to the origin states’ in Minsk, it was halted by Russian State Duma that had eventually passed ‘Federal Law on Cultural Valuables Displaced to the USSR as a Result of the Second World War and Located on the Territory of the Russian Federation’ which made restitution currently impossible.[100]

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania consider themselves as revivals of the three independent countries that existed prior to their occupation and annexation by the Soviet Union in 1940. They maintain that the process by which they were incorporated into the Soviet Union violated both international law and their own law, and that in 1990–1991 they were reasserting an independence that still legally existed.

There are additionally six states that claim independence from the other internationally recognized post-Soviet states but possess limited international recognition: Abkhazia, Artsakh, Donetsk, Luhansk, South Ossetia and Transnistria. The Chechen separatist movement of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, the Gagauz separatist movement of the Gagauz Republic and the Talysh separatist movement of the Talysh-Mughan Autonomous Republic lack any international recognition.

Foreign relations

Soviet stamps 1974 for friendship between USSR and India

Mikhail Gorbachev and George H. W. Bush signing bilateral documents during Gorbachev’s official visit to the United States in 1990

During his rule, Stalin always made the final policy decisions. Otherwise, Soviet foreign policy was set by the commission on the Foreign Policy of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, or by the party’s highest body the Politburo. Operations were handled by the separate Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It was known as the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (or Narkomindel), until 1946. The most influential spokesmen were Georgy Chicherin (1872–1936), Maxim Litvinov (1876–1951), Vyacheslav Molotov (1890–1986), Andrey Vyshinsky (1883–1954) and Andrei Gromyko (1909–1989). Intellectuals were based in the Moscow State Institute of International Relations.[101]

- Comintern (1919–1943), or Communist International, was an international communist organization based in the Kremlin that advocated world communism. The Comintern intended to ‘struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state’.[102] It was abolished as a conciliatory measure toward Britain and the United States.[103]

- Comecon, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Russian: Совет Экономической Взаимопомощи, Sovet Ekonomicheskoy Vzaimopomoshchi, СЭВ, SEV) was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under Soviet control that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along with several communist states elsewhere in the world. Moscow was concerned about the Marshall Plan, and Comecon was meant to prevent countries in the Soviets’ sphere of influence from moving towards that of the Americans and Southeast Asia. Comecon was the Eastern Bloc’s reply to the formation in Western Europe of the Organization for European Economic Co-Operation (OEEC),[104][105]

- The Warsaw Pact was a collective defence alliance formed in 1955 among the USSR and its satellite states in Eastern Europe during the Cold War. The Warsaw Pact was the military complement to the Comecon, the regional economic organization for the socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe. The Warsaw Pact was created in reaction to the integration of West Germany into NATO.[106]

- The Cominform (1947–1956), informally the Communist Information Bureau and officially the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers’ Parties, was the first official agency of the international Marxist-Leninist movement since the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943. Its role was to coordinate actions between Marxist-Leninist parties under Soviet direction. Stalin used it to order Western European communist parties to abandon their exclusively parliamentarian line and instead concentrate on politically impeding the operations of the Marshall Plan.[107] It also coordinated international aid to Marxist-Leninist insurgents during the Greek Civil War in 1947–1949.[108] It expelled Yugoslavia in 1948 after Josip Broz Tito insisted on an independent program. Its newspaper, For a Lasting Peace, for a People’s Democracy!, promoted Stalin’s positions. The Cominform’s concentration on Europe meant a deemphasis on world revolution in Soviet foreign policy. By enunciating a uniform ideology, it allowed the constituent parties to focus on personalities rather than issues.[109]

Early policies (1919–1939)

The Marxist-Leninist leadership of the Soviet Union intensely debated foreign policy issues and changed directions several times. Even after Stalin assumed dictatorial control in the late 1920s, there were debates, and he frequently changed positions.[110]

During the country’s early period, it was assumed that Communist revolutions would break out soon in every major industrial country, and it was the Soviet responsibility to assist them. The Comintern was the weapon of choice. A few revolutions did break out, but they were quickly suppressed (the longest lasting one was in Hungary)—the Hungarian Soviet Republic—lasted only from 21 March 1919 to 1 August 1919. The Russian Bolsheviks were in no position to give any help.

By 1921, Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin realized that capitalism had stabilized itself in Europe and there would not be any widespread revolutions anytime soon. It became the duty of the Russian Bolsheviks to protect what they had in Russia, and avoid military confrontations that might destroy their bridgehead. Russia was now a pariah state, along with Germany. The two came to terms in 1922 with the Treaty of Rapallo that settled long-standing grievances. At the same time, the two countries secretly set up training programs for the illegal German army and air force operations at hidden camps in the USSR.[111]

Moscow eventually stopped threatening other states, and instead worked to open peaceful relationships in terms of trade, and diplomatic recognition. The United Kingdom dismissed the warnings of Winston Churchill and a few others about a continuing Marxist-Leninist threat, and opened trade relations and de facto diplomatic recognition in 1922. There was hope for a settlement of the pre-war Tsarist debts, but it was repeatedly postponed. Formal recognition came when the new Labour Party came to power in 1924.[112] All the other countries followed suit in opening trade relations. Henry Ford opened large-scale business relations with the Soviets in the late 1920s, hoping that it would lead to long-term peace. Finally, in 1933, the United States officially recognized the USSR, a decision backed by the public opinion and especially by US business interests that expected an opening of a new profitable market.[113]

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Stalin ordered Marxist-Leninist parties across the world to strongly oppose non-Marxist political parties, labor unions or other organizations on the left. Stalin reversed himself in 1934 with the Popular Front program that called on all Marxist parties to join with all anti-Fascist political, labor, and organizational forces that were opposed to fascism, especially of the Nazi variety.[114][115]

In 1939, half a year after the Munich Agreement, the USSR attempted to form an anti-Nazi alliance with France and Britain.[116] Adolf Hitler proposed a better deal, which would give the USSR control over much of Eastern Europe through the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. In September, Germany invaded Poland, and the USSR also invaded later that month, resulting in the partition of Poland. In response, Britain and France declared war on Germany, marking the beginning of World War II.[117]

World War II (1939–1945)

Up until his death in 1953, Joseph Stalin controlled all foreign relations of the Soviet Union during the interwar period. Despite the increasing build-up of Germany’s war machine and the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Soviet Union did not cooperate with any other nation, choosing to follow its own path.[118] However, after Operation Barbarossa, the Soviet Union’s priorities changed. Despite previous conflict with the United Kingdom, Vyacheslav Molotov dropped his post war border demands.[119]

Cold War (1945–1991)

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc, which began following World War II in 1945. The term cold war is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the two superpowers, but they each supported major regional conflicts known as proxy wars. The conflict was based around the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence by these two superpowers, following their temporary alliance and victory against Nazi Germany in 1945. Aside from the nuclear arsenal development and conventional military deployment, the struggle for dominance was expressed via indirect means such as psychological warfare, propaganda campaigns, espionage, far-reaching embargoes, rivalry at sports events and technological competitions such as the Space Race.

Politics

There were three power hierarchies in the Soviet Union: the legislature represented by the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the government represented by the Council of Ministers, and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the only legal party and the final policymaker in the country.[120]

Communist Party

Military parade on the Red Square in Moscow, 7 November 1964

At the top of the Communist Party was the Central Committee, elected at Party Congresses and Conferences. In turn, the Central Committee voted for a Politburo (called the Presidium between 1952 and 1966), Secretariat and the general secretary (First Secretary from 1953 to 1966), the de facto highest office in the Soviet Union.[121] Depending on the degree of power consolidation, it was either the Politburo as a collective body or the General Secretary, who always was one of the Politburo members, that effectively led the party and the country[122] (except for the period of the highly personalized authority of Stalin, exercised directly through his position in the Council of Ministers rather than the Politburo after 1941).[123] They were not controlled by the general party membership, as the key principle of the party organization was democratic centralism, demanding strict subordination to higher bodies, and elections went uncontested, endorsing the candidates proposed from above.[124]

The Communist Party maintained its dominance over the state mainly through its control over the system of appointments. All senior government officials and most deputies of the Supreme Soviet were members of the CPSU. Of the party heads themselves, Stalin (1941–1953) and Khrushchev (1958–1964) were Premiers. Upon the forced retirement of Khrushchev, the party leader was prohibited from this kind of double membership,[125] but the later General Secretaries for at least some part of their tenure occupied the mostly ceremonial position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the nominal head of state. The institutions at lower levels were overseen and at times supplanted by primary party organizations.[126]

However, in practice the degree of control the party was able to exercise over the state bureaucracy, particularly after the death of Stalin, was far from total, with the bureaucracy pursuing different interests that were at times in conflict with the party.[127] Nor was the party itself monolithic from top to bottom, although factions were officially banned.[128]

Government

The Supreme Soviet (successor of the Congress of Soviets) was nominally the highest state body for most of the Soviet history,[129] at first acting as a rubber stamp institution, approving and implementing all decisions made by the party. However, its powers and functions were extended in the late 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, including the creation of new state commissions and committees. It gained additional powers relating to the approval of the Five-Year Plans and the government budget.[130] The Supreme Soviet elected a Presidium (successor of the Central Executive Committee) to wield its power between plenary sessions,[131] ordinarily held twice a year, and appointed the Supreme Court,[132] the Procurator General[133] and the Council of Ministers (known before 1946 as the Council of People’s Commissars), headed by the Chairman (Premier) and managing an enormous bureaucracy responsible for the administration of the economy and society.[131] State and party structures of the constituent republics largely emulated the structure of the central institutions, although the Russian SFSR, unlike the other constituent republics, for most of its history had no republican branch of the CPSU, being ruled directly by the union-wide party until 1990. Local authorities were organized likewise into party committees, local Soviets and executive committees. While the state system was nominally federal, the party was unitary.[134]

The state security police (the KGB and its predecessor agencies) played an important role in Soviet politics. It was instrumental in the Great Purge,[135] but was brought under strict party control after Stalin’s death. Under Yuri Andropov, the KGB engaged in the suppression of political dissent and maintained an extensive network of informers, reasserting itself as a political actor to some extent independent of the party-state structure,[136] culminating in the anti-corruption campaign targeting high-ranking party officials in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[137]

Separation of power and reform

The constitution, which was promulgated in 1924, 1936 and 1977,[138] did not limit state power. No formal separation of powers existed between the Party, Supreme Soviet and Council of Ministers[139] that represented executive and legislative branches of the government. The system was governed less by statute than by informal conventions, and no settled mechanism of leadership succession existed. Bitter and at times deadly power struggles took place in the Politburo after the deaths of Lenin[140] and Stalin,[141] as well as after Khrushchev’s dismissal,[142] itself due to a decision by both the Politburo and the Central Committee.[143] All leaders of the Communist Party before Gorbachev died in office, except Georgy Malenkov[144] and Khrushchev, both dismissed from the party leadership amid internal struggle within the party.[143]

Between 1988 and 1990, facing considerable opposition, Mikhail Gorbachev enacted reforms shifting power away from the highest bodies of the party and making the Supreme Soviet less dependent on them. The Congress of People’s Deputies was established, the majority of whose members were directly elected in competitive elections held in March 1989. The Congress now elected the Supreme Soviet, which became a full-time parliament, and much stronger than before. For the first time since the 1920s, it refused to rubber stamp proposals from the party and Council of Ministers.[145] In 1990, Gorbachev introduced and assumed the position of the President of the Soviet Union, concentrated power in his executive office, independent of the party, and subordinated the government,[146] now renamed the Cabinet of Ministers of the USSR, to himself.[147]

Tensions grew between the Union-wide authorities under Gorbachev, reformists led in Russia by Boris Yeltsin and controlling the newly elected Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, and communist hardliners. On 19–21 August 1991, a group of hardliners staged a coup attempt. The coup failed, and the State Council of the Soviet Union became the highest organ of state power ‘in the period of transition’.[148] Gorbachev resigned as General Secretary, only remaining President for the final months of the existence of the USSR.[149]

Judicial system

The judiciary was not independent of the other branches of government. The Supreme Court supervised the lower courts (People’s Court) and applied the law as established by the constitution or as interpreted by the Supreme Soviet. The Constitutional Oversight Committee reviewed the constitutionality of laws and acts. The Soviet Union used the inquisitorial system of Roman law, where the judge, procurator, and defence attorney collaborate to establish the truth.[150]

Administrative divisions

Constitutionally, the USSR was a federation of constituent Union Republics, which were either unitary states, such as Ukraine or Byelorussia (SSRs), or federations, such as Russia or Transcaucasia (SFSRs),[120] all four being the founding republics who signed the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR in December 1922. In 1924, during the national delimitation in Central Asia, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan were formed from parts of Russia’s Turkestan ASSR and two Soviet dependencies, the Khorezm and Bukharan SSRs. In 1929, Tajikistan was split off from the Uzbekistan SSR. With the constitution of 1936, the Transcaucasian SFSR was dissolved, resulting in its constituent republics of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan being elevated to Union Republics, while Kazakhstan and Kirghizia were split off from Russian SFSR, resulting in the same status.[151] In August 1940, Moldavia was formed from parts of Ukraine and Bessarabia and Ukrainian SSR. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (SSRs) were also admitted into the union which was not recognized by most of the international community and was considered an illegal occupation. Karelia was split off from Russia as a Union Republic in March 1940 and was reabsorbed in 1956. Between July 1956 and September 1991, there were 15 union republics (see map below).[152]

While nominally a union of equals, in practice the Soviet Union was dominated by Russians. The domination was so absolute that for most of its existence, the country was commonly (but incorrectly) referred to as ‘Russia’. While the RSFSR was technically only one republic within the larger union, it was by far the largest (both in terms of population and area), most powerful, and most highly developed. The RSFSR was also the industrial center of the Soviet Union. Historian Matthew White wrote that it was an open secret that the country’s federal structure was ‘window dressing’ for Russian dominance. For that reason, the people of the USSR were usually called ‘Russians’, not ‘Soviets’, since ‘everyone knew who really ran the show’.[153]

| Republic | Map of the Union Republics between 1956 and 1991 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | ||

| 7 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 10 | ||

| 11 | ||

| 12 | ||

| 13 | ||

| 14 | ||

| 15 |

Military

A medium-range SS-20 non-ICBM ballistic missile, the deployment of which in the late 1970s launched a new arms race in Europe in which NATO deployed Pershing II missiles in West Germany, among other things

Under the Military Law of September 1925, the Soviet Armed Forces consisted of the Land Forces, the Air Force, the Navy, Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU), and the Internal Troops.[154] The OGPU later became independent and in 1934 joined the NKVD, and so its internal troops were under the joint leadership of the defense and internal commissariats. After World War II, Strategic Missile Forces (1959), Air Defense Forces (1948) and National Civil Defense Forces (1970) were formed, which ranked first, third, and sixth in the official Soviet system of importance (ground forces were second, Air Force Fourth, and Navy Fifth).

The army had the greatest political influence. In 1989, there served two million soldiers divided between 150 motorized and 52 armored divisions. Until the early 1960s, the Soviet navy was a rather small military branch, but after the Caribbean crisis, under the leadership of Sergei Gorshkov, it expanded significantly. It became known for battlecruisers and submarines. In 1989 there served 500 000 men. The Soviet Air Force focused on a fleet of strategic bombers and during war situation was to eradicate enemy infrastructure and nuclear capacity. The air force also had a number of fighters and tactical bombers to support the army in the war. Strategic missile forces had more than 1,400 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), deployed between 28 bases and 300 command centers.

In the post-war period, the Soviet Army was directly involved in several military operations abroad. These included the suppression of the uprising in East Germany (1953), Hungarian revolution (1956) and the invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968). The Soviet Union also participated in the war in Afghanistan between 1979 and 1989.

In the Soviet Union, general conscription applied.

Space program

At the end of the 1950s, the USSR constructed the first satellite – Sputnik 1, which marked the beginning of the Space Race, a competition to achieve superior spaceflight capability with the United States.[155] This was followed by other successful satellites, most notably Sputnik 5, where test dogs were sent to space. On 12 April 1961, the USSR launched Vostok 1, which carried Yuri Gagarin, making him the first human to ever be launched into space and complete a space journey.[156] At that time, the first plans for space shuttles and orbital stations were drawn up in Soviet design offices, but in the end personal disputes between designers and management prevented this.

As for Lunar space program; USSR only had a program on automated spacecraft launches; with no crewed spacecraft used; passing on the ‘Moon Race’ part of Space Race.[157]

In the 1970s, specific proposals for the design of the space shuttle began to emerge, but shortcomings, especially in the electronics industry (rapid overheating of electronics), postponed the program until the end of the 1980s. The first shuttle, the Buran, flew in 1988, but without a human crew. Another shuttle, Ptichka, eventually ended up under construction, as the shuttle project was canceled in 1991. For their launch into space, there is today an unused superpower rocket, Energia, which is the most powerful in the world.[158]

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union managed to build the Mir orbital station. It was built on the construction of Salyut stations and its only role was civilian-grade research tasks.[159][160]

Mir was the only orbital station in operation from 1986 to 1998. Gradually, other modules were added to it, including American ones. However, the station deteriorated rapidly after a fire on board, so in 2001 it was decided to bring it into the atmosphere where it burned down.[159]

Human rights

Human rights in the Soviet Union were severely limited. The Soviet Union was a totalitarian state from 1927 until 1953[161][162][163][164] and a one-party state until 1990.[165] Freedom of speech was suppressed and dissent was punished. Independent political activities were not tolerated, whether these involved participation in free labor unions, private corporations, independent churches or opposition political parties. The freedom of movement within and especially outside the country was limited. The state restricted rights of citizens to private property.

The Soviet conception of human rights was very different from international law. According to Soviet legal theory, «it is the government who is the beneficiary of human rights which are to be asserted against the individual».[166] The Soviet state was considered as the source of human rights.[167] Therefore, the Soviet legal system regarded law as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government.[168] Extensive extra-judicial powers were given to the Soviet secret police agencies. The Soviet government in practice significantly curbed the rule of law, civil liberties, protection of law and guarantees of property,[168][169] which were considered as examples of «bourgeois morality» by Soviet law theorists such as Andrey Vyshinsky.[170] According to Vladimir Lenin, the purpose of socialist courts was «not to eliminate terror … but to substantiate it and legitimize it in principle».[168]

The Soviet Union signed legally-binding human rights documents, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1973, but they were neither widely known or accessible to people living under Communist rule, nor were they taken seriously by the Communist authorities.[171]: 117

Economy

The Soviet Union in comparison to other countries by GDP (nominal) per capita in 1965 based on a West-German school book (1971)

|

> 5,000 DM 2,500–5,000 DM 1,000–2,500 DM |

500–1,000 DM 250–500 DM |

The Soviet Union adopted a command economy, whereby production and distribution of goods were centralized and directed by the government. The first Bolshevik experience with a command economy was the policy of War communism, which involved the nationalization of industry, centralized distribution of output, coercive requisition of agricultural production, and attempts to eliminate money circulation, private enterprises and free trade. After the severe economic collapse, Lenin replaced war communism by the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921, legalizing free trade and private ownership of small businesses. The economy quickly recovered as a result.[172]

After a long debate among the members of the Politburo about the course of economic development, by 1928–1929, upon gaining control of the country, Stalin abandoned the NEP and pushed for full central planning, starting forced collectivization of agriculture and enacting draconian labor legislation. Resources were mobilized for rapid industrialization, which significantly expanded Soviet capacity in heavy industry and capital goods during the 1930s.[172] The primary motivation for industrialization was preparation for war, mostly due to distrust of the outside capitalist world.[173] As a result, the USSR was transformed from a largely agrarian economy into a great industrial power, leading the way for its emergence as a superpower after World War II.[174] The war caused extensive devastation of the Soviet economy and infrastructure, which required massive reconstruction.[175]

By the early 1940s, the Soviet economy had become relatively self-sufficient; for most of the period until the creation of Comecon, only a tiny share of domestic products was traded internationally.[176] After the creation of the Eastern Bloc, external trade rose rapidly. However, the influence of the world economy on the USSR was limited by fixed domestic prices and a state monopoly on foreign trade.[177] Grain and sophisticated consumer manufactures became major import articles from around the 1960s.[176] During the arms race of the Cold War, the Soviet economy was burdened by military expenditures, heavily lobbied for by a powerful bureaucracy dependent on the arms industry. At the same time, the USSR became the largest arms exporter to the Third World. Significant amounts of Soviet resources during the Cold War were allocated in aid to the other socialist states.[176]

Picking cotton in Armenia in the 1930s

From the 1930s until its dissolution in late 1991, the way the Soviet economy operated remained essentially unchanged. The economy was formally directed by central planning, carried out by Gosplan and organized in five-year plans. However, in practice, the plans were highly aggregated and provisional, subject to ad hoc intervention by superiors. All critical economic decisions were taken by the political leadership. Allocated resources and plan targets were usually denominated in rubles rather than in physical goods. Credit was discouraged, but widespread. The final allocation of output was achieved through relatively decentralized, unplanned contracting. Although in theory prices were legally set from above, in practice they were often negotiated, and informal horizontal links (e.g. between producer factories) were widespread.[172]

A number of basic services were state-funded, such as education and health care. In the manufacturing sector, heavy industry and defence were prioritized over consumer goods.[178] Consumer goods, particularly outside large cities, were often scarce, of poor quality and limited variety. Under the command economy, consumers had almost no influence on production, and the changing demands of a population with growing incomes could not be satisfied by supplies at rigidly fixed prices.[179] A massive unplanned second economy grew up at low levels alongside the planned one, providing some of the goods and services that the planners could not. The legalization of some elements of the decentralized economy was attempted with the reform of 1965.[172]

Although statistics of the Soviet economy are notoriously unreliable and its economic growth difficult to estimate precisely,[180][181] by most accounts, the economy continued to expand until the mid-1980s. During the 1950s and 1960s, it had comparatively high growth and was catching up to the West.[182] However, after 1970, the growth, while still positive, steadily declined much more quickly and consistently than in other countries, despite a rapid increase in the capital stock (the rate of capital increase was only surpassed by Japan).[172]

Overall, the growth rate of per capita income in the Soviet Union between 1960 and 1989 was slightly above the world average (based on 102 countries).[183] A 1986 study published in the American Journal of Public Health claimed that, citing World Bank data, the Soviet model provided a better quality of life and human development than market economies at the same level of economic development in most cases.[184] According to Stanley Fischer and William Easterly, growth could have been faster. By their calculation, per capita income in 1989 should have been twice higher than it was, considering the amount of investment, education and population. The authors attribute this poor performance to the low productivity of capital.[185] Steven Rosefielde states that the standard of living declined due to Stalin’s despotism. While there was a brief improvement after his death, it lapsed into stagnation.[186]

In 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev attempted to reform and revitalize the economy with his program of perestroika. His policies relaxed state control over enterprises but did not replace it by market incentives, resulting in a sharp decline in output. The economy, already suffering from reduced petroleum export revenues, started to collapse. Prices were still fixed, and the property was still largely state-owned until after the country’s dissolution.[172][179] For most of the period after World War II until its collapse, Soviet GDP (PPP) was the second-largest in the world, and third during the second half of the 1980s,[187] although on a per-capita basis, it was behind that of First World countries.[188] Compared to countries with similar per-capita GDP in 1928, the Soviet Union experienced significant growth.[189]

In 1990, the country had a Human Development Index of 0.920, placing it in the ‘high’ category of human development. It was the third-highest in the Eastern Bloc, behind Czechoslovakia and East Germany, and the 25th in the world of 130 countries.[190]

Energy