Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | стенда́п | стенда́пы |

| Р. | стенда́па | стенда́пов |

| Д. | стенда́пу | стенда́пам |

| В. | стенда́п | стенда́пы |

| Тв. | стенда́пом | стенда́пами |

| Пр. | стенда́пе | стенда́пах |

стен—да́п

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -стендап-.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [stɛnˈdap]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- неол. эстрадный жанр — выступление на сцене перед живой аудиторией с монологом собственного сочинения ◆ Важно понимать лишь, что стендап это выступление от первого лица. То есть когда автор говорит о себе, шутит про то, что с ним происходило в действительности, либо высказывает свое персональное мнение о тех или иных актуальных или исторических событиях. Алексей Ярцев, «Юмор. Стендап. Психология сцены. Пособие для артистов и им сочувствующих», 2018 г. [Google Книги]

- проф. репортаж или комментарий телевизионного журналиста в кадре непосредственно в момент съёмки ◆ В новостных сюжетах стендап не должен превышать 9 секунд, в тематических – 12 секунд, в прямых включениях всё индивидуально, но долго смотреть на говорящие головы зрителям не интересно. Валерий Богатов, «Новости на телевидении. Практическое пособие», 2017 г. [Google Книги] ◆ — Миша, сейчас делаем стендап возле «Аполло», потом поснимаешь планы, и встретимся в павильоне — хочу скафандр надеть. Е. П. Касимов, «Казино доктора Брауна», 2006 г. [Google Книги]

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- выступление

- репортаж

Гипонимы[править]

- стендап-комедия

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология[править]

Происходит от англ. stand-up «конферанс», далее от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

|

Библиография[править]

- стендап // Научно-информационный «Орфографический академический ресурс „Академос“» Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. orfo.ruslang.ru

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

«Сторителлинг» – один из основных приемов, который используется в этом жанре выступлений. Приглашаем вас на эту программу, чтобы освоить метод и использовать не только для юмористических выступлений, но и в любой сфере жизни, начиная от общения с друзьями и заканчивая публичными выступлениями.

1

Собирайте идеи

Этим вы должны заниматься постоянно. Носите с собой блокнот и записывайте туда все, что приходит в голову: готовые шутки, идеи для них, просто идиотские ситуации, которые со временем можно превратить во что-то смешное. Скорее всего, 90% из них не пригодятся. Но зато «промывка идей» принесет вам 10% самородков. Из них вы и будете строить свое выступление.

Где еще брать темы для шуток

- Шутите над тем, что сами считаете смешным. Ваши шутки должны быть эмоциональными. Вы сами должны смеяться с них. Искренне и по-настоящему. Поэтому не делайте упор на коммерчески выгодные темы. Смейтесь над тем, над чем хочется.

- Шутите над собой. Самонасмешка – это, пожалуй, самый эффективный способ быстро установить связь с аудиторией. Смейтесь над собой, и вас будут воспринимать не заносчивым снобом, а своим веселым парнем. Это даст слушателям позитивную установку на все ваше выступление.

- Выбирайте распространенные и известные темы. Если ваши шутки будут слишком специфическими, вы рискуете остаться непонятым и услышать эту зловещую тишину.

- Смотрите других комиков. Это не значит, что вы будете заниматься плагиатом. Ищите интересные темы, углубляйтесь, шутите над самими стендаперами или манерой их выступления. Учиться у лучших не зазорно – помните об этом.

2

Пишите шутки

Следующий этап – создание шуток на основе заготовленного материала. И для этого вам нужно знать общую структуру элементарной единицы юмора. Комики выделяют в ней две основных составляющих: setup (установка) и punchline (кульминация). Сетап создает в голове у зрителя определенную картинку, а панчлайн разрушает ее, при этом вызывая удивление и смех.

Вот, к примеру, шутка британского комика Милтона Джона:

«Познакомился в Интернете с девушкой, выложил шариками у нее под окном: «Ты выйдешь за меня?» Потом увидел ее лицо, и вопрос сдулся сам собой».

Думаем, вы сами легко догадаетесь, где здесь что. Важно помнить, что установка должна содержать относительно достоверные факты. Ее задача – не удивлять, а усыпить бдительность слушателя. Чем больший контраст между сетапом и панчлайном, тем смешнее получится шутка.

Важный совет: если дело идет туго, попробуйте придумывать шутки в компании с кем-либо еще. Это даст приток новых идей и поможет посмотреть на свои творения со стороны.

3

Создайте монолог

Даже если у вас будет добрая сотня искрометных шуток (на языке стендаперов они называются «биты»), этого недостаточно, чтобы подойти к микрофону. Вы должны написать монолог («act» по англоязычной терминологии). Некое связное повествование из шуток, объединенных одной или несколькими темами. Ваше первое выступление не должно длиться больше 3-х минут (именно столько времени дают на открытых микрофонах), причем на каждую минуту отводите не более 5-6 шуток.

Вот как может выглядеть схема такого выступления:

- Сложности с общественным транспортом;

- Работа и тупой босс;

- Вечер пятницы;

- Ночь пятницы.

Что касается переходов между подтемами, то это вопрос вашей фантазии. Вы можете делать их как плавными, так и резко менять тему.

Совет новичкам: Начинайте с общих и нейтральных тем и лишь затем переходите к чему-то более острому и откровенному. В будущем вы сможете нарушить этот принцип, но сначала нужно заслужить доверие зрителей.

4

Репетиция

Итак, вы написали свой монолог. Вы даже возможно продемонстрировали его нескольким особо доверенным людям, и он показался им забавным. Потом вы его выучили. Что ж, пришло время репетировать. Лучше делать это не самому, а с напарником, который даст вам обратную связь. Также можно записать черновое выступление на видео, а потом проанализировать все ошибки. Не тренируйтесь перед зеркалом – в реальности вы будете смотреть на других людей, а не на любимого себя.

Обязательно проверьте время выступления. Будьте готовы, что в реальности все может пойти не так. Оставьте про запас несколько шуток, или же наоборот, подумайте, как сократить монолог при необходимости.

Придумайте план Б на случай, если шутка не зайдет. Конечно, можно рассчитывать на импровизацию. Но вам ведь ничего не мешает сделать это заранее, да?

Главная цель репетиции – отработать подачу шуток. Самый смешной стендап можно загубить просто унылым видом лица. Вы сами должны проявлять эмоции, чтобы вызвать их у зрителей.

Репетиция – это не залог успеха, а способ повысить свою уверенность. Даже самые знаменитые комики иногда забывали слова прямо во время выступления. Это нормально. Сделайте вид, что все так и задумано, попробуйте пошутить над этим или просто двигайтесь дальше. Возьмите с собой небольшую шпаргалку, на случай если что-то вылетит из головы.

5

Выступление

Вы проделали большую работу, готовились и через несколько секунд ваш выход. И первая проблема, с которой вы столкнетесь – волнение. Вот, что говорит по этому поводу стендап-тренер Джуди Картер: «Не пытайтесь перестать нервничать – просто измените свое отношение к этому. Может быть, нервничать – смешно, а быть спокойным и уверенным в себе – скучно?…Если вы беспокоитесь, что у вас пересохнет во рту, возьмите с собой воду. Если ущипнуть себя за щеку, слюна тоже выделится, но лучше сделайте это до выхода на сцену».

Вы поняли посыл, да? От этого нет таблетки. Просто забейте или превратите это в шутку.

Будьте готовы импровизировать. Удачная шутка, основанная на происходящем в момент выступления (или до него), помогает быстро установить контакт с аудиторией. Что делать, когда кто-то уже пошутил на выбранную вами тему? Если вы не хотите, прятаться в тени чьей-то славы, лучше отказаться от части вашего выступления. Кстати, именно для этого вам и понадобится план Б.

Заканчивайте ваш выход самой смешной (даже физиологичной или сексуальной) шуткой. Или даже тогда, когда вы вдруг сорвали ошеломительные аплодисменты, а в запасе еще полминуты. Принцип простой – уходите на пике славы. Но вежливо. Четко обозначьте конец выступления и попрощайтесь.

А дальше? Ну, как хотите. Несравненная Джуди Картер предлагает напиться.

Полезная литература по теме

- Библия Комедии — Джуди Картер: книга научит структуре стендап-шуток и даст понять, что стендап — это не дар небес, а ремесло, которое можно освоить.

- Пошаговое руководство по созданию комедийного шоу — Грег Дин: эта книга проведет вас по всем этапам создания стендап-шоу – от идеи до подготовки выступления и репетиций.

- Джон Мэкс «Как быть смешным»: не совсем о стендапе, но о шутках. Как их придумывать, как рассказывать и вообще как развивать чувство юмора.

- The Comic Toolbox: How to Be Funny Even If You’re Not — John Vorhaus: книга о психологии стендаперства. В ней вы узнаете о психологических трюках, которые помогают мотивировать, настраивать себя на рабочий лад и заряжать других людей.

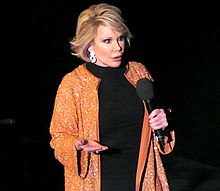

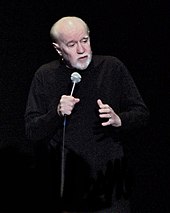

| Stand-up comedy |

|---|

George Carlin performing in 2008 |

Stand-up comedy is a comedic performance to a live audience in which the performer addresses the audience directly from the stage. The performer is known as a comedian, a comic or a stand-up.

Stand-up comedy consists of one-liners, stories, observations or a shtick that may incorporate props, music, magic tricks or ventriloquism. It can be performed almost anywhere, including comedy clubs, comedy festivals, bars, nightclubs, colleges or theatres.[citation needed][1]

History[edit]

Stand-up as a Western art form has its roots in the stump speech of American minstrel shows, which featured an actor in blackface delivering nonsensical monologue to the audience. While the intention of stump speeches was to mock African-Americans, they also occasionally contained political and social satire. The minstrel show would later influence theatrical traditions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as vaudeville and burlesque.[2]

Charles Farrar Browne (April 26, 1834 – March 6, 1867) was an American humor writer, better known under his nom de plume, Artemus Ward, which as a character, an illiterate rube with «Yankee common sense», Browne also played in public performances. He is considered to be America’s first stand-up comedian.

The first documented use of «stand-up» as a term was in The Stage in 1911, detailing a woman named Nellie Perrier delivering ‘stand up comic ditties in a chic and charming manner’, though this was used to describe a performance of comedy songs rather than stand-up comedy in its true modern form.[3]

In The Yorkshire Evening Post on November 10, 1917, the «Stage Gossip» column described the career of a comedian named Finlay Dunn. The article stated that Dunn was «what he calls ‘a stand-up comedian'» during the latter part of the 19th century, although the term may have been used retrospectively.[4]

Genres[edit]

Stand-up has multiple genres and styles with their own formats. Common ones include:

- Alternative: Intended to counter the established figures of mainstream comedy.

- Character: A fictional persona created by the performer.

- DIY: A «new alternative» to alternative comedy.[5]

- Musical: Humorous songs or musical parody sometimes without lyrics.

- Observational: Conversation on the absurdities of everyday life.[6]

- Satire: Ridicule of celebrity, political figures, the establishment, religion or ideology.[citation needed]

Stand up performances[edit]

Opener, feature and headliner[edit]

The host, compere or emcee «warms up» the audience and introduces the other performers. This is followed by the opener, the feature, then the headliner. The host may also double as an opener for smaller shows.[7] Proven comics can get regular bookings for club chains and comedy venues. Jobbing stand-ups may perform sets at two or more venues on the same day.[citation needed]

Open mic[edit]

Club and small venues often run open mic events; these slots may be booked in advance or left for walk-ins. Comedians use open mics to work on material or to show off their skills to get an opener slot.[8] «Bringer shows» are open mics that require amateur performers to bring a specified number of paying guests with them in order to receive stage time.[citation needed]

Festivals[edit]

As well as being a mainstay of the comedy circuit, festivals often also showcase up and coming acts, with promoters and agents using the festivals to seek out new talent.[9]

Specials[edit]

Experienced comics with a popular following may produce a special. Typically lasting between one and two hours, a special may be recorded on tour or at a show advertised and performed specifically for the purpose. It may be released as a comedy album, video, or on television and streaming services.[10]

Comedy set[edit]

Routine[edit]

A stand-up defines their craft through the development of the routine or set. These are designed through the construction and revision of jokes and «bits» (linked jokes). The routine emerges from the arrangement of bits to build an interlinked narrative or overarching theme leading to the closer (the final joke that ties the themes of the show together in a satisfying or meaningful conclusion).[citation needed]

Most jokes are the juxtaposition of two incongruous things and are made up of the premise, set-up, and punchline, often adding a twist, topper or tagline for an intensified or extra laugh. Delivery relies on the use of intonation, inflection, attitude and timing or other stylistic devices such as the rule of three, idioms, archetypes or wordplay.[11][12] Another popular joke structure is the paraprosdokian, a surprising punchline that changes the context or meaning of the setup.[13]

In order to falsely frame their stories as true or to free themselves of responsibility for breaking social conventions, comedians can use the jester’s privilege, the right to discuss and mock anything freely without being punished.[14][15] «Punching up» and «punching down» describe who should be the «butt of the joke». This carries the assumption that, relative to the comedian’s own socio-political identity, comedy should «punch up» at the rich and powerful without «punching down» at those who are marginalized and less fortunate.[16][17]

Joke theft[edit]

Appropriation and plagiarism are considered «social crimes» by most stand-ups. There have been several high-profile accusations of joke theft, some ending in lawsuits for copyright infringement. Those accused will sometimes claim cryptomnesia or parallel thinking,[18][19] but it is difficult to successfully sue for joke theft regardless due to the idea–expression distinction.[20]

Audiences[edit]

According to Anna Spagnolli, stand-up comedy audiences «are both ‘co-constructors of the situation’ and ‘co-responsible for it'».[21]

Audiences enter into an unspoken contract with the comedian in which they temporarily disregard normal social rules and accept the discussion of unexpected, controversial or scandalous subjects. The ability to understand the premise and appreciate the associated punchline determines whether a joke results in laughter or scathing disapproval.[citation needed]

Stand-up comedy differs from most other performing arts as the comedian is usually the only thing on stage and addresses the audience directly. The material should be perceived as spontaneous and only fully succeeds when the comic creates a sense of intimacy, while also discouraging heckling.[citation needed]

Part of the appeal of stand up is in appreciation of the skill of the performer, most people find the idea of standing on stage extremely daunting; research on the subject has consistently found that the fear of public speaking is more intense than the fear of dying.[22][23]

The audience is integral to live comedy, both as a foil to the comedian and as a contributing factor to the overall experience. The use of canned laughter in television comedy reveals this, with shows often seeming «dry» or dull without it. Shows may be filmed in front of a live audience for the same reason.[24]

Terms[edit]

Beat: A pause specifically to create comic timing.

Bit: A section within a comedy show or routine.

Bombing: Failing to get laughs.

Callback: A reference to a joke earlier in the set.

Chewing the scenery: Being overly theatrical or «trying too hard» to get a laugh, especially when failing.

Chi-chi room: The ritzy room of a nightclub or a comedy club with niche performances.[25]

Clapter: When the audience cheers or applauds an opinion that they agree with, but which is not funny enough for them to laugh at. Coined by Seth Meyers.[26]

Corpsing or breaking: When the comedian laughs unintentionally during a portion of the show in which they are supposed to keep a straight face.

Crowd work: Talking directly with audience members through prewritten bits, improvisation or both.

Hack: A clichéd or unskilled comic.

Killing and dying: When a stand-up does well, they are killing. If they are doing poorly, they are dying.

Mugging: Pulling silly faces to get a cheap laugh.

Punter: A member of the audience. Primarily a British term.[27]

The room: The space where the performance takes place. Stand-ups can «read the room» to interpret signs from the audience or «work the room» by interacting with the audience directly.

Smelling the road: Claiming that one can «smell the road» on a comedian suggests they have compromised their originality or pandered to get laughs while touring.

Tight five: A five-minute routine that is well-rehearsed and consists of a comedian’s best material that reliably gets laughs. It is often used for auditions and is a stepping stone to getting a paid spot.[28]

Warm up: To warm up a «cold» audience during the opening act before the main show. Often used at the filming of television comedies in front of studio audiences.

Work out: The process in which brand new jokes are introduced and polished over time.

Records[edit]

Phyllis Diller holds the Guinness World Record for most laughs per minute, with 12.[29]

Taylor Goodwin holds the Guinness World Record for most jokes told in an hour with 550.[30]

Lee Evans sold £7 million worth of tickets for his 2011 tour in a day, the biggest first-day sale of a British comedy tour.[31]

Peter Kay[edit]

British comedian Peter Kay currently holds multiple records for his 2010-2011 show The Tour That Doesn’t Tour Tour…Now On Tour on a 112 date UK & Ireland arena tour.

- Longest individual run at the Manchester Arena performing 20 nights.

- First ever stand-up comedian to play 15 sold out nights at The O2, London.

- The only British artist to ever play 20 consecutive nights at an arena.

- Over 1.2 million tickets sold in arenas across the UK and Ireland, making it the biggest stand-up comedy tour of all time.

See also[edit]

- Macchietta, 19th-century Italian comedy

- Rakugo, Japanese one-man comedy

- Manzai, Japanese double act comedy

- Owarai, Japanese stand-up comedy[32]

- The Clown’s Prayer, a poem or prayer that comedians use for inspiration

- Xiangsheng, Chinese stand-up comedy

References[edit]

- ^ Zoglin, Richard. «Stand-up comedy». Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Bloomquist, Jennifer. “The Minstrel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of ‘Black’ Identities in Entertainment.” Journal of African American Studies 19, no. 4 (2015): 410–425.

- ^ Comedy Studies (VOL. 8, NO. 1, 106-09)

- ^ Double, Oliver (9 Apr 2018). «The origin of the term ‘stand-up comedy’«. Comedy Studies. 12 (2): 235–237. doi:10.1080/2040610X.2018.1428427. S2CID 195058528 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

[T]he ‘new alternative’ known as DIY comedy. It opposed the commercialist ethos that had come to dominate alternative comedy and responded to an ‘increasing sense of purposelessness and loneliness among young persons in Western society’.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

Observational comedy works by mocking ‘normal’ behaviours but, even as it does so, it often affirms and promotes a fixed idea of what ‘normal’ is.

- ^ Seizer, Susan (2011). «On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy». Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 215–216. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

On this circuit, shows generally consist of three to four comics: Headliner, Feature act, Opener and/or Emcee (i.e., Master of Ceremonies). The Headliner does roughly an hour of original material. The Feature act does 25-30 minutes. The Opener has a ten minute slot, and the Emcee squeezes in a joke or two between acts (if the Opener is not also acting as the Emcee)…

- ^ Oswalt, Patton (14 June 2014). «A Closed Letter to Myself About Thievery, Heckling and Rape Jokes». Patton Oswalt. Patton Oswalt. Archived from the original on 2019-03-04. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

Open mikes are where, as a comedian [like Daniel Tosh and his controversy], you’re supposed to be allowed to fuck up.

- ^ Frances-White, Deborah; Shandur, Marsha (2016). Off the Mic: The World’s Best Stand-up Comedians Get Serious About Comedy. Jim Jefferies. NY, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4725-2638-0.

Go to festivals, because that’s where you get noticed by the media … [and] gauge [yourself against] everybody else.

- ^ «Top 25 Stand-Up Specials of All-Time». IMDb. 12 August 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Eddie Izzard (2011). The Art of Stand-Up (TV). United Kingdom: BBC: One.

Eddie Izzard states, ‘it should be—establish, reaffirm, and then you kill it on the third… you can keep reaffirming before you twist.

- ^ Helitzer, Mel; Shatz, Mark (2005). Comedy Writing secrets: the best-selling book on how to think funny, write funny, act funny, and get paid for it (2nd ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-58297-357-9.

- ^ Leighton, H. Vernon (2020). «A Theory of Humor (Abridged) and the Comic Mechanisms of John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces«. In Marsh, Leslie (ed.). Theology and Geometry: Essays on John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (Politics, Literature, & Film). United Kingdom: Lexington Books (published 29 January 2020). pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-1-4985-8547-7. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

it is useful to examine the famous paraprosdokian, ‘I’ve had a wonderful evening, but this wasn’t it.’

- ^ «Medieval Jesters – And their Parallels in Modern America». History is Now. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ Billington, Sandra. “A Social History of the Fool,” The Harvester Press, 1984. ISBN 0-7108-0610-8

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2018). The Politics of British Stand-Up Comedy: The New Alternative. Palgrave Studies in Comedy. London, UK: palgrave macmillan. pp. 23, 29. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01105-5. ISBN 978-3-030-01104-8. LCCN 2018956867.

the comedy of the left ‘punches up’ at the established authorities of its time, be they governmental, cultural, or artistic. … a joke is a joke, not a political act, and the ability to say what you like in the context of joking is held sacred.

- ^ Cohen, Sascha (2014). «A Brief History of Punch-Down Comedy». Mask. Maskmag. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

George Carlin echoed this sentiment, observing that ‘comedy has traditionally picked on people in power.’ … ‘[Chappelle and Gervais] have done daring and subversive work on other topics, like race and religion, respectively, but punching down at an essentially powerless minority group is pure hack.’

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Voss, Erik (4 November 2010). «Is There Ever a Justification for Joke Stealing?». Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Abby Stein. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 242. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

[T]here are also cases of simple coincidence and, often in the case of observational material, parallel thinking.

- ^ Bailey, Jonathan (27 September 2021). «When Joke Theft Becomes Serious». Plagiarism today. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «The Interactional Context of Humor in Stand-up Comedy’«. 2009: 210–230.

- ^ «Fear public speaking more than death? Fear not – the audience only sees 20% of your nerves». February 2022.

- ^ Burgess, Kaya. «Speaking in public is worse than death for most».

- ^ Lockyear, Sharon; Myers, Lynn (November 2011). «It’s About Expecting the Unexpected — Live Stand-up Comedy from the Audiences Perspective» (PDF). Participations. 8 (2): 165–188 – via on-line Database.

- ^ Wilde, Larry (2000) [1968]. «Shelley Berman». Great Comedians Talk About Comedy. Shelley Berman. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Executive Books. p. 86. ISBN 0-937539-51-1.

Just because it is small, they call it a chi-chi room, or because they bring certain oddball forms of entertainment

- ^ Pandya, Hershal (10 January 2018). «The Rise of «Clapter» Comedy». Vulture. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bello, Benamin (6 September 2021). «Whose job is it to deal with aggressive comedy punters?». Chortle. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rosenfield, Stephen (2018). Mastering Stand-Up: The Complete Guide to Becoming a Successful Comedian. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-61373-692-0.

If you have an all ‘A’ [material] 5-minute set, you’ll get paid nothing.

- ^ King, Susan (22 December 2006). «Diller can still pack a punch line». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

[Phyllis Diller] still holds the Guinness Book of World Records for doling out 12 punch lines a minute.

- ^ «Most jokes told in an hour». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015.

- ^ «Biggest first day sale of any British comedy tour ever». Chortle. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Spacey, John (5 September 2015). «4 Types of Japanese comedy». Japan Talk. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

| Stand-up comedy |

|---|

George Carlin performing in 2008 |

Stand-up comedy is a comedic performance to a live audience in which the performer addresses the audience directly from the stage. The performer is known as a comedian, a comic or a stand-up.

Stand-up comedy consists of one-liners, stories, observations or a shtick that may incorporate props, music, magic tricks or ventriloquism. It can be performed almost anywhere, including comedy clubs, comedy festivals, bars, nightclubs, colleges or theatres.[citation needed][1]

History[edit]

Stand-up as a Western art form has its roots in the stump speech of American minstrel shows, which featured an actor in blackface delivering nonsensical monologue to the audience. While the intention of stump speeches was to mock African-Americans, they also occasionally contained political and social satire. The minstrel show would later influence theatrical traditions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as vaudeville and burlesque.[2]

Charles Farrar Browne (April 26, 1834 – March 6, 1867) was an American humor writer, better known under his nom de plume, Artemus Ward, which as a character, an illiterate rube with «Yankee common sense», Browne also played in public performances. He is considered to be America’s first stand-up comedian.

The first documented use of «stand-up» as a term was in The Stage in 1911, detailing a woman named Nellie Perrier delivering ‘stand up comic ditties in a chic and charming manner’, though this was used to describe a performance of comedy songs rather than stand-up comedy in its true modern form.[3]

In The Yorkshire Evening Post on November 10, 1917, the «Stage Gossip» column described the career of a comedian named Finlay Dunn. The article stated that Dunn was «what he calls ‘a stand-up comedian'» during the latter part of the 19th century, although the term may have been used retrospectively.[4]

Genres[edit]

Stand-up has multiple genres and styles with their own formats. Common ones include:

- Alternative: Intended to counter the established figures of mainstream comedy.

- Character: A fictional persona created by the performer.

- DIY: A «new alternative» to alternative comedy.[5]

- Musical: Humorous songs or musical parody sometimes without lyrics.

- Observational: Conversation on the absurdities of everyday life.[6]

- Satire: Ridicule of celebrity, political figures, the establishment, religion or ideology.[citation needed]

Stand up performances[edit]

Opener, feature and headliner[edit]

The host, compere or emcee «warms up» the audience and introduces the other performers. This is followed by the opener, the feature, then the headliner. The host may also double as an opener for smaller shows.[7] Proven comics can get regular bookings for club chains and comedy venues. Jobbing stand-ups may perform sets at two or more venues on the same day.[citation needed]

Open mic[edit]

Club and small venues often run open mic events; these slots may be booked in advance or left for walk-ins. Comedians use open mics to work on material or to show off their skills to get an opener slot.[8] «Bringer shows» are open mics that require amateur performers to bring a specified number of paying guests with them in order to receive stage time.[citation needed]

Festivals[edit]

As well as being a mainstay of the comedy circuit, festivals often also showcase up and coming acts, with promoters and agents using the festivals to seek out new talent.[9]

Specials[edit]

Experienced comics with a popular following may produce a special. Typically lasting between one and two hours, a special may be recorded on tour or at a show advertised and performed specifically for the purpose. It may be released as a comedy album, video, or on television and streaming services.[10]

Comedy set[edit]

Routine[edit]

A stand-up defines their craft through the development of the routine or set. These are designed through the construction and revision of jokes and «bits» (linked jokes). The routine emerges from the arrangement of bits to build an interlinked narrative or overarching theme leading to the closer (the final joke that ties the themes of the show together in a satisfying or meaningful conclusion).[citation needed]

Most jokes are the juxtaposition of two incongruous things and are made up of the premise, set-up, and punchline, often adding a twist, topper or tagline for an intensified or extra laugh. Delivery relies on the use of intonation, inflection, attitude and timing or other stylistic devices such as the rule of three, idioms, archetypes or wordplay.[11][12] Another popular joke structure is the paraprosdokian, a surprising punchline that changes the context or meaning of the setup.[13]

In order to falsely frame their stories as true or to free themselves of responsibility for breaking social conventions, comedians can use the jester’s privilege, the right to discuss and mock anything freely without being punished.[14][15] «Punching up» and «punching down» describe who should be the «butt of the joke». This carries the assumption that, relative to the comedian’s own socio-political identity, comedy should «punch up» at the rich and powerful without «punching down» at those who are marginalized and less fortunate.[16][17]

Joke theft[edit]

Appropriation and plagiarism are considered «social crimes» by most stand-ups. There have been several high-profile accusations of joke theft, some ending in lawsuits for copyright infringement. Those accused will sometimes claim cryptomnesia or parallel thinking,[18][19] but it is difficult to successfully sue for joke theft regardless due to the idea–expression distinction.[20]

Audiences[edit]

According to Anna Spagnolli, stand-up comedy audiences «are both ‘co-constructors of the situation’ and ‘co-responsible for it'».[21]

Audiences enter into an unspoken contract with the comedian in which they temporarily disregard normal social rules and accept the discussion of unexpected, controversial or scandalous subjects. The ability to understand the premise and appreciate the associated punchline determines whether a joke results in laughter or scathing disapproval.[citation needed]

Stand-up comedy differs from most other performing arts as the comedian is usually the only thing on stage and addresses the audience directly. The material should be perceived as spontaneous and only fully succeeds when the comic creates a sense of intimacy, while also discouraging heckling.[citation needed]

Part of the appeal of stand up is in appreciation of the skill of the performer, most people find the idea of standing on stage extremely daunting; research on the subject has consistently found that the fear of public speaking is more intense than the fear of dying.[22][23]

The audience is integral to live comedy, both as a foil to the comedian and as a contributing factor to the overall experience. The use of canned laughter in television comedy reveals this, with shows often seeming «dry» or dull without it. Shows may be filmed in front of a live audience for the same reason.[24]

Terms[edit]

Beat: A pause specifically to create comic timing.

Bit: A section within a comedy show or routine.

Bombing: Failing to get laughs.

Callback: A reference to a joke earlier in the set.

Chewing the scenery: Being overly theatrical or «trying too hard» to get a laugh, especially when failing.

Chi-chi room: The ritzy room of a nightclub or a comedy club with niche performances.[25]

Clapter: When the audience cheers or applauds an opinion that they agree with, but which is not funny enough for them to laugh at. Coined by Seth Meyers.[26]

Corpsing or breaking: When the comedian laughs unintentionally during a portion of the show in which they are supposed to keep a straight face.

Crowd work: Talking directly with audience members through prewritten bits, improvisation or both.

Hack: A clichéd or unskilled comic.

Killing and dying: When a stand-up does well, they are killing. If they are doing poorly, they are dying.

Mugging: Pulling silly faces to get a cheap laugh.

Punter: A member of the audience. Primarily a British term.[27]

The room: The space where the performance takes place. Stand-ups can «read the room» to interpret signs from the audience or «work the room» by interacting with the audience directly.

Smelling the road: Claiming that one can «smell the road» on a comedian suggests they have compromised their originality or pandered to get laughs while touring.

Tight five: A five-minute routine that is well-rehearsed and consists of a comedian’s best material that reliably gets laughs. It is often used for auditions and is a stepping stone to getting a paid spot.[28]

Warm up: To warm up a «cold» audience during the opening act before the main show. Often used at the filming of television comedies in front of studio audiences.

Work out: The process in which brand new jokes are introduced and polished over time.

Records[edit]

Phyllis Diller holds the Guinness World Record for most laughs per minute, with 12.[29]

Taylor Goodwin holds the Guinness World Record for most jokes told in an hour with 550.[30]

Lee Evans sold £7 million worth of tickets for his 2011 tour in a day, the biggest first-day sale of a British comedy tour.[31]

Peter Kay[edit]

British comedian Peter Kay currently holds multiple records for his 2010-2011 show The Tour That Doesn’t Tour Tour…Now On Tour on a 112 date UK & Ireland arena tour.

- Longest individual run at the Manchester Arena performing 20 nights.

- First ever stand-up comedian to play 15 sold out nights at The O2, London.

- The only British artist to ever play 20 consecutive nights at an arena.

- Over 1.2 million tickets sold in arenas across the UK and Ireland, making it the biggest stand-up comedy tour of all time.

See also[edit]

- Macchietta, 19th-century Italian comedy

- Rakugo, Japanese one-man comedy

- Manzai, Japanese double act comedy

- Owarai, Japanese stand-up comedy[32]

- The Clown’s Prayer, a poem or prayer that comedians use for inspiration

- Xiangsheng, Chinese stand-up comedy

References[edit]

- ^ Zoglin, Richard. «Stand-up comedy». Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Bloomquist, Jennifer. “The Minstrel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of ‘Black’ Identities in Entertainment.” Journal of African American Studies 19, no. 4 (2015): 410–425.

- ^ Comedy Studies (VOL. 8, NO. 1, 106-09)

- ^ Double, Oliver (9 Apr 2018). «The origin of the term ‘stand-up comedy’«. Comedy Studies. 12 (2): 235–237. doi:10.1080/2040610X.2018.1428427. S2CID 195058528 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

[T]he ‘new alternative’ known as DIY comedy. It opposed the commercialist ethos that had come to dominate alternative comedy and responded to an ‘increasing sense of purposelessness and loneliness among young persons in Western society’.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

Observational comedy works by mocking ‘normal’ behaviours but, even as it does so, it often affirms and promotes a fixed idea of what ‘normal’ is.

- ^ Seizer, Susan (2011). «On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy». Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 215–216. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

On this circuit, shows generally consist of three to four comics: Headliner, Feature act, Opener and/or Emcee (i.e., Master of Ceremonies). The Headliner does roughly an hour of original material. The Feature act does 25-30 minutes. The Opener has a ten minute slot, and the Emcee squeezes in a joke or two between acts (if the Opener is not also acting as the Emcee)…

- ^ Oswalt, Patton (14 June 2014). «A Closed Letter to Myself About Thievery, Heckling and Rape Jokes». Patton Oswalt. Patton Oswalt. Archived from the original on 2019-03-04. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

Open mikes are where, as a comedian [like Daniel Tosh and his controversy], you’re supposed to be allowed to fuck up.

- ^ Frances-White, Deborah; Shandur, Marsha (2016). Off the Mic: The World’s Best Stand-up Comedians Get Serious About Comedy. Jim Jefferies. NY, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4725-2638-0.

Go to festivals, because that’s where you get noticed by the media … [and] gauge [yourself against] everybody else.

- ^ «Top 25 Stand-Up Specials of All-Time». IMDb. 12 August 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Eddie Izzard (2011). The Art of Stand-Up (TV). United Kingdom: BBC: One.

Eddie Izzard states, ‘it should be—establish, reaffirm, and then you kill it on the third… you can keep reaffirming before you twist.

- ^ Helitzer, Mel; Shatz, Mark (2005). Comedy Writing secrets: the best-selling book on how to think funny, write funny, act funny, and get paid for it (2nd ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-58297-357-9.

- ^ Leighton, H. Vernon (2020). «A Theory of Humor (Abridged) and the Comic Mechanisms of John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces«. In Marsh, Leslie (ed.). Theology and Geometry: Essays on John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (Politics, Literature, & Film). United Kingdom: Lexington Books (published 29 January 2020). pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-1-4985-8547-7. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

it is useful to examine the famous paraprosdokian, ‘I’ve had a wonderful evening, but this wasn’t it.’

- ^ «Medieval Jesters – And their Parallels in Modern America». History is Now. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ Billington, Sandra. “A Social History of the Fool,” The Harvester Press, 1984. ISBN 0-7108-0610-8

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2018). The Politics of British Stand-Up Comedy: The New Alternative. Palgrave Studies in Comedy. London, UK: palgrave macmillan. pp. 23, 29. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01105-5. ISBN 978-3-030-01104-8. LCCN 2018956867.

the comedy of the left ‘punches up’ at the established authorities of its time, be they governmental, cultural, or artistic. … a joke is a joke, not a political act, and the ability to say what you like in the context of joking is held sacred.

- ^ Cohen, Sascha (2014). «A Brief History of Punch-Down Comedy». Mask. Maskmag. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

George Carlin echoed this sentiment, observing that ‘comedy has traditionally picked on people in power.’ … ‘[Chappelle and Gervais] have done daring and subversive work on other topics, like race and religion, respectively, but punching down at an essentially powerless minority group is pure hack.’

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Voss, Erik (4 November 2010). «Is There Ever a Justification for Joke Stealing?». Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Abby Stein. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 242. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

[T]here are also cases of simple coincidence and, often in the case of observational material, parallel thinking.

- ^ Bailey, Jonathan (27 September 2021). «When Joke Theft Becomes Serious». Plagiarism today. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «The Interactional Context of Humor in Stand-up Comedy’«. 2009: 210–230.

- ^ «Fear public speaking more than death? Fear not – the audience only sees 20% of your nerves». February 2022.

- ^ Burgess, Kaya. «Speaking in public is worse than death for most».

- ^ Lockyear, Sharon; Myers, Lynn (November 2011). «It’s About Expecting the Unexpected — Live Stand-up Comedy from the Audiences Perspective» (PDF). Participations. 8 (2): 165–188 – via on-line Database.

- ^ Wilde, Larry (2000) [1968]. «Shelley Berman». Great Comedians Talk About Comedy. Shelley Berman. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Executive Books. p. 86. ISBN 0-937539-51-1.

Just because it is small, they call it a chi-chi room, or because they bring certain oddball forms of entertainment

- ^ Pandya, Hershal (10 January 2018). «The Rise of «Clapter» Comedy». Vulture. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bello, Benamin (6 September 2021). «Whose job is it to deal with aggressive comedy punters?». Chortle. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rosenfield, Stephen (2018). Mastering Stand-Up: The Complete Guide to Becoming a Successful Comedian. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-61373-692-0.

If you have an all ‘A’ [material] 5-minute set, you’ll get paid nothing.

- ^ King, Susan (22 December 2006). «Diller can still pack a punch line». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

[Phyllis Diller] still holds the Guinness Book of World Records for doling out 12 punch lines a minute.

- ^ «Most jokes told in an hour». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015.

- ^ «Biggest first day sale of any British comedy tour ever». Chortle. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Spacey, John (5 September 2015). «4 Types of Japanese comedy». Japan Talk. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Всего найдено: 34

На месте вопросов должно стоять тире или двоеточие? Заранее благодарю! «Семинар для членов патриотических организаций, время проведения (?) март-апрель 2020 года, планируемое количество участников (?) 500 человек.»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нужно поставить тире.

Как правильно пишется ролл-ап?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Орфографическая форма этого слова пока не установлена академическим орфографическим словарем. Сейчас написание колеблется: пишут и слитно, и раздельно, и через дефис. Предполагаем, что будущее все же за слитным написанием, так как часть ап в русском языке не обладает достаточной смысловой самостоятельностью. Есть и орфографические аналогии: пикап, мейкап.

Добрый день! Правильно ли расставлены запятые в предложении: Такие конструкции, как ролл-апы или Х-баннеры, собираются и разбираются за 5 минут.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятые расставлены верно.

Как правильно писать: Подождите денек другой. Нужно ли ставить дефис после слова денек

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Дефис нужен. Сочетания, имеющие значение приблизительного указания на количество или время чего-либо пишутся через дефис, ср.: день-другой, неделя-другая, напишет письмо-другое, год-два, два-три часа, раза три-четыре, человек двенадцать—пятнадцать, двое-трое мальчиков, вдвоём-втроём; Он вернется в марте-апреле.

См. также фиксацию в орфографическом словаре.

Добрый день! Как пишется чекап или чек-ап — проверка здоровья по типу диспансеризации?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нормативной рекомендации нет, возможны варианты написания. Отметим, что в ходе освоения такие заимствования тяготеют к слитному написанию (ср.: пикап, мейкап).

Здравствуйте! Интересует написание слова лайн-ап: на дефисе или слитно. Имеется в виду состав исполнителей или групп на концерте. Не оставьте без внимания мой вопрос, пожалуйста!!!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словарной рекомендации нет. Дефисное написание предпочтительно.

Добрый день! Как правильно писать: стендап, стенд ап или стенд-ап?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: стендап.

Добрый день! Во фразе «молодой человек лет двадцати двух-двадцати трёх» корректно использовать дефис или тире? Речь идёт о приблизительности, то есть используется то же правило, что и в выражениях «день-другой, год-два, человек десять-пятнадцать, в марте-апреле», и значит, должен быть дефис — так ли это? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Поскольку числительное состоит из двух слов, вместо дефиса пишется тире: молодой человек лет двадцати двух — двадцати трех.

Здравствуйте! Подскажите, тире с пробелами или без пробелов мы ставим в сочетании «март — май», «сентябрь — ноябрь»? Спасибо заранее!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Если сочетание имеет значение приблизительного указания, ставится дефис, например: в марте-апреле («то ли в марте, то ли в апреле»). Если же сочетание обозначает интервал значений («от… до»), ставится тире, пробелы нужны: в марте – апреле (т. е. с каких-то чисел марта до каких-то чисел апреля), в марте – мае (с марта до мая).

Не нашла в Письмовнике — как склонять: Роман Божья-Воля. Считаю, что склоняться будет только вторая часть фамилии. Так ли это?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы правы. «Справочник по русскому языку: правописание, произношение, литературное редактирование» Д. Э. Розенталя, Е. В. Джанджаковой, Н. П. Кабановой указывает: в русских двойных фамилиях первая часть склоняется, если она сама по себе употребляется как фамилия: песни Соловьева-Седого. Ср. также: картины Петрова-Водкина, проза Соколова-Микитова, фильмы Михалкова-Кончаловского, судьба Муравьева-Апостола. Если же первая часть не образует фамилии, то она не склоняется: исследования Грум-Гржимайло. Поскольку в рассматриваемой фамилии первая часть (Божья) не употребляется как самостоятельная фамилия, корректно склонять только вторую часть фамилии: Романа Божья-Воли, Роману Божья-Воле.

Здравствуйте, уважаемые коллеги! Как пишется слово «пост-апокалипсис» — слитно или через дефис? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Приставка пост— пишется слитно: постапокалипсис.

Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно писать: зомби-апокалипсис или зомбиапокалипсис?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно дефисное написание.

Как пишется: старт-ап, стартап, старт ап?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: стартап. См.: Русский орфографический словарь РАН / Под ред. В. В. Лопатина, О. Е. Ивановой. – 4-е изд., испр. и доп. – М., 2012.

Добрый день.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, правильно ли расставлены запятые в данном предложении?

» В связи с выходом из строя программно-аппаратного комплекса, вещание осуществлялось напрямую со спутника, без врезок региональной рекламы.»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Такая пунктуация возможна.

Ну вот, на простейшие вопросы вы отвечаете, а те, что потруднее, игнорируете. Уже в третий раз спрашиваю: как правильно писать «купальник танкини, трусы боксы, трусы слипы, бюстгальтер пуш-ап и другие подобные выражения»? Нужны ли прописные буквы, кавычки, дефисы?

И еще одно (ОЧЕНЬ-ОЧЕНЬ СРОЧНО!): правильно ли говорить «ни граммом больше»? Например: «Получают ровно столько, сколько удается собрать, — ни граммом больше».

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректное написание: купальник танкини, трусы боксы, трусы слипы, бюстгальтер пуш-ап.

Ни граммом больше — корректно.

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Стендап.

Стенд́ап (распространены также такие варианты написания и произношения слова, как «ст́эндап», «ст́эндап-камеди», «стенд́ап комедия») (все от англ. stand-up comedy) — сольное юмористическое выступление перед живой аудиторией. Часто для таких выступлений организуются специальные комедийные клубы (англ. comedy club).

В репертуар стендап-комиков, как правило, входят авторские монологи (routines), короткие шутки (one-liners) и импровизация с залом. В надежде вызвать смех аудитории комики включают в свои выступления также музыкальные, театрализованные фрагменты, чревовещание, фокусы и многое другое.

История

Стендап зародился в Великобритании в 18-19 веках. Артисты выступали в мюзик-холлах, от которого произошло название жанра: мюзик-холл камеди. Со временем, жесткая цензура спала после ухода Лорда Чемберлена, и комиков не заставляли отдавать материал на проверку. К 1970 году музыкальный жанр отжил свое. Большим толчком к развитию служило телевидение и радио. Если раньше артист мог выступать с одним номером много лет, то теперь приходилось писать новый материал. США имеет свою историю. Основатели жанра пришли из водевиля. Ими считаются Марк Твен и Норман Уилкерсон. В послевоенное время произошел «бум» стендап-камеди. По всей Америке строились новые клубы. А к 1970 году стендап-камеди в Америке становится основной формой юмористического выступления.

Стендап в России

- В силу телевизионного формата передач (установленные редакторами правила, наложенный смех, монтаж), КВН, Comedy Club и Убойная лига не предполагают ни свободы автора в используемых приемах, ни непосредственной реакции аудитории, и поэтому стендапом не являются. Однако многие участники указанных телепрограмм, такие как Александр Незлобин, Руслан Белый и Павел Воля, выступают в форме стендапа.

- Ян Арлазоров был немногим из актёров разговорного жанра, кто общался со зрителями напрямую, втягивая их в сценическое действо.

Англоязычные представители жанра

- Дилан Моран

- Джордж Карлин

- Ленни Брюс

- Адам Сэндлер

- Вупи Голдберг

- Джефф Данэм

- Эдди Иззард

- Джим Керри

- Билли Кристал

- Мартин Лоуренс

- Эдди Мёрфи

- Крис Рок

- Робин Уильямс

- Джейми Фокс

- Рассел Брэнд

- Рассел Питерс

- Ноэль Филдинг

- Луис Си Кей

- Джимми Карр

- Кэролайн Ри

- Уи́льям Ме́лвин «Билл» Хикс

Примечания

Ссылки

| |

|

|---|---|

| Форматы |

Дуэт • Камеди-рок • Мандзай • Моноспектакль • Опера • Пантомима • Ситком • Стендап |

| Поджанры |

Буффонада • Скетч • Трагикомедия |

| Разное |

Ирония • Комик • Пранк • Сатира • Шутка • Юмор |