| Tutankhamun | |

|---|---|

| Tutankhaten, Tutankhamen[1] | |

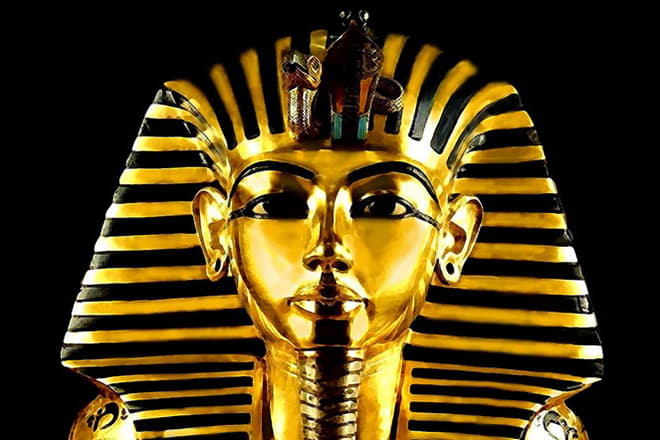

Tutankhamun’s golden mask |

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | c. 1332 – 1323 BC, New Kingdom (18th Dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Neferneferuaten |

| Successor | Ay (granduncle/grandfather-in-law) |

|

Royal titulary |

|

| Consort | Ankhesenamun (half-sister) |

| Children | 2 (317a and 317b) |

| Father | KV55 mummy,[5] identified as most likely Akhenaten |

| Mother | The Younger Lady |

| Born | c. 1341 BC |

| Died | c. 1323 BC (aged 18–19) |

| Burial | KV62 |

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen[a] ( ;[6] Ancient Egyptian: twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn; c. 1341 BC – 1323 BC), also referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh. Having ruled over the New Kingdom of Egypt, he was the last of his royal family to exercise governance during the Eighteenth Dynasty, with his reign lasting from c. 1332 BC until c. 1323 BC in the conventional Egyptian chronology. Through DNA testing, his father was identified as the mummy within tomb KV55 and his mother was identified as a mummy from tomb KV35, with his mother having been his father’s sister. The mummy of Tutankhamun’s father is speculated to be of the pharaoh Akhenaten, though this is disputed; the mummy of Tutankhamun’s mother is informally called «The Younger Lady» but is otherwise unknown.[7]

Tutankhamun took the throne at eight or nine years of age, under the unprecedented viziership of his eventual successor, Ay, to whom he may have been related. Within tomb KV21, the mummy KV21A was identified as having been the biological mother of Tutankhamun’s two daughters — it is therefore speculated that this mummy is of his only known wife, Ankhesenamun, who was his paternal half-sister. Their two daughters were identified as the 317a and 317b mummies; daughter 317a was born prematurely at 5–6 months of pregnancy while daughter 317b was born at full-term, though both died in infancy.[8] His names — Tutankhaten and Tutankhamun — are thought to have meant «living image of Aten» and «living image of Amun» in the ancient Egyptian language, with the god Aten having been replaced by the god Amun after Akhenaten’s death. Some Egyptologists, including Battiscombe Gunn, have claimed that the translation may be incorrect, instead being closer to «the-life-of-Aten-is-pleasing» or «one-perfect-of-life-is-Aten» (latter translation by Gerhard Fecht [de]).

Tutankhamun restored the ancient Egyptian religion against Akhenaten’s Atenism and also relocated Egypt’s capital back to Thebes, undoing Akhenaten’s earlier relocation of the capital to Amarna. He also enriched and endowed the priestly orders of two important cults, initiated a restoration process for old monuments that were damaged during the Amarna Period, and reburied his father’s remains in the Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun suffered from a deformed left foot and bone necrosis, which rendered him physically disabled and dependent on assistive canes. He also had other health issues, including scoliosis, and had contracted several strains of malaria.

In 1922, a team led by British Egyptologist Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings excavated Tutankhamun’s tomb, in an effort that was funded by British aristocrat George Herbert.[9] The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb received worldwide press coverage; with over 5,000 artifacts, it gave rise to renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun’s mask, now preserved at the Egyptian Museum, remains a popular symbol. The deaths of some individuals who were involved in the unearthing of Tutankhamun’s mummy have been popularly attributed to the «curse of the pharaohs» due to the similarity of their circumstances. Some of his treasure has traveled worldwide with unprecedented response; the Egyptian government allowed tours beginning in 1961. Tutankhamun has, since the discovery of his intact tomb, been referred to as «King Tut» in colloquial terms.[10]

Family

Tutankhamun, whose original name was Tutankhaten or Tutankhuaten, was born during the reign of Akhenaten, during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[11] Akhenaten’s reign was characterized by a dramatic shift in ancient Egyptian religion, known as Atenism, and the relocation of the capital to the site of Amarna, which gave its name to the modern term for this era, the Amarna Period.[12] Toward the end of the Amarna Period, two other pharaohs appear in the record who were apparently Akhenaten’s co-regents: Neferneferuaten, a female ruler who may have been Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti or his daughter Meritaten; and Smenkhkare, whom some Egyptologists believe was the same person as Neferneferuaten but most regard as a distinct figure.[13] It is uncertain whether Smenkhkare’s reign outlasted Akhenaten’s, whereas Neferneferuaten is now thought to have become co-regent shortly before Akhenaten’s death and to have reigned for some time after it.[14]

An inscription from Hermopolis refers to «Tutankhuaten» as a «king’s son», and he is generally thought to have been the son of Akhenaten,[15] although some suggest instead that Smenkhkare was his father.[16] Inscriptions from Tutankhamun’s reign treat him as a son of Akhenaten’s father, Amenhotep III, but that is only possible if Akhenaten’s 17-year reign included a long co-regency with his father,[17] a possibility that many Egyptologists once supported but is now being abandoned.[18]

While some suggestions have been made that Tutankhamun’s mother was Meketaten, the second daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, based on a relief from the Royal Tomb at Amarna,[b] this possibility has been deemed unlikely given that she was about 10 years old at the time of her death.[20] Another interpretation of the relief names Nefertiti as his mother.[c][22] Meritaten has also been put forward as his mother based on a re-examination of a box lid and coronation tunic found in his tomb.[23] Tutankhamun was wet nursed by a woman named Maia, known from her tomb at Saqqara.[24][25]

In 2008, genetic analysis was carried out on the mummified remains of Tutankhamun and others thought or known to be New Kingdom royalty by a team from University of Cairo. The results indicated that his father was the mummy from tomb KV55, identified as Akhenaten, and that his mother was the mummy from tomb KV35, known as the «Younger Lady», who was found to be a full sister of her husband.[26] The team reported it was over 99.99 percent certain that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[27] More recent genetic analysis, published in 2020, revealed Tutankhamun had the haplogroups YDNA R1b, which originated in Europe and which today makes up 50–90% of the genetic pool of modern western Europeans, and mtDNA K, which originated in the Near East. He shares this Y-haplogroup with his father, the KV55 mummy (Akhenaten), and grandfather, Amenhotep III, and his mtDNA haplogroup with his mother, The Younger Lady, his grandmother, Tiye, and his great-grandmother, Thuya, upholding the results of the earlier genetic study. The profiles for Tutankhamun and Amenhotep III were incomplete and the analysis produced differing probability figures despite having concordant allele results. Because the relationships of these two mummies with the KV55 mummy had previously been confirmed in an earlier study, the haplogroup prediction of both mummies could be derived from the full profile of the KV55 data.[28]

The identity of The Younger Lady is unknown but she cannot be Nefertiti, as she was not known to be a sister of Akhenaten.[29] However, researchers such as Marc Gabolde and Aidan Dodson claim that Nefertiti was indeed Tutankhamun’s mother. In this interpretation of the DNA results, the genetic closeness is not due to a brother-sister pairing but the result of three generations of first-cousin marriage, making Nefertiti a first cousin of Akhenaten.[30] The validity and reliability of the genetic data from mummified remains has been questioned due to possible degradation due to decay.[31]

When Tutankhaten became king, he married Ankhesenpaaten, one of Akhenaten’s daughters, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun.[32] They had two daughters, neither of whom survived infancy.[26] While only an incomplete genetic profile was obtained from the two mummified foetuses, it was enough to confirm that Tutankhamun was their father.[26] Likewise, only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained so far. KV21A has been suggested as the mother of the foetuses but the data is not statistically significant enough to allow her to be securely identified as Ankhesenamun.[26] Computed tomography studies published in 2011 revealed that one daughter was born prematurely at 5–6 months of pregnancy and the other at full-term, 9 months.[8] Tutankhamun’s death marked the end of the royal line of the 18th Dynasty.[33]

Reign

Tutankhamun was between eight and nine years of age when he ascended the throne and became pharaoh,[36] taking the throne name Nebkheperure.[37] He reigned for about nine years.[38] During Tutankhamun’s reign the position of Vizier had been split between Upper and Lower Egypt. The principal vizier for Upper Egypt was Usermontu. Another figure named Pentju was also vizier but it is unclear of which lands. It is not entirely known if Ay, Tutankhamun’s successor, actually held this position. A gold foil fragment from KV58 seems to indicate, but not certainly, that Ay was referred to as a Priest of Maat along with an epithet of «vizier, doer of maat.» The epithet does not fit the usual description used by the regular vizier but might indicate an informal title. It might be that Ay used the title of vizier in an unprecedented manner.[39]

An Egyptian priest named Manetho wrote a comprehensive history of ancient Egypt where he refers to a king named Orus, who ruled for 36 years and had a daughter named Acencheres who reigned twelve years and her brother Rathotis who ruled for only nine years.[40][41] The Amarna rulers are central in the list but which name corresponds with which historic figure is not agreed upon by researchers. Orus and Acencheres have been identified with Horemheb and Akhenaten and Rathotis with Tutankhamun. The names are also associated with Smenkhkare, Amenhotep III, Ay and the others in differing order.[42]

Kings were venerated after their deaths through mortuary cults and associated temples. Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped in this manner during his lifetime.[43] A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Ra and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by sin. Temples of his cult were built as far away as in Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king, indicative of the universality of his cult.[44]

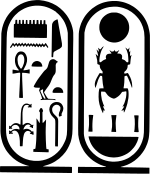

In order for the pharaoh, who held divine office, to be linked to the people and the gods, special epithets were created for them at their accession to the throne. The ancient Egyptian titulary also served to demonstrate one’s qualities and link them to the terrestrial realm. The five names were developed over the centuries beginning with the Horus name.[d][45][46] Tutankhamun’s[e] original nomen, Tutankhaten,[47] did not have a Nebty name[f] or a Gold Falcon name[g] associated with it[48] as nothing has been found with the full five-name protocol.[h] Tutankhaten was believed to mean «Living-image-of-Aten» as far back as 1877; however, not all Egyptologists agree with this interpretation. English Egyptologist Battiscombe Gunn believed that the older interpretation did not fit with Akhenaten’s theology. Gunn believed that such an name would have been blasphemous. He saw tut as a verb and not a noun and gave his translation in 1926 as The-life-of-Aten-is-pleasing. Professor Gerhard Fecht also believed the word tut was a verb. He noted that Akhenaten used tit as a word for ‘image’, not tut. Fecht translated the verb tut as «To be perfect/complete». Using Aten as the subject, Fecht’s full translation was «One-perfect-of-life-is-Aten». The Hermopolis Block (two carved block fragments discovered in Ashmunein) has a unique spelling of the first nomen written as Tutankhuaten; it uses ankh as a verb, which does support the older translation of Living-image-of-Aten.[48]

End of Amarna period

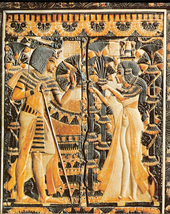

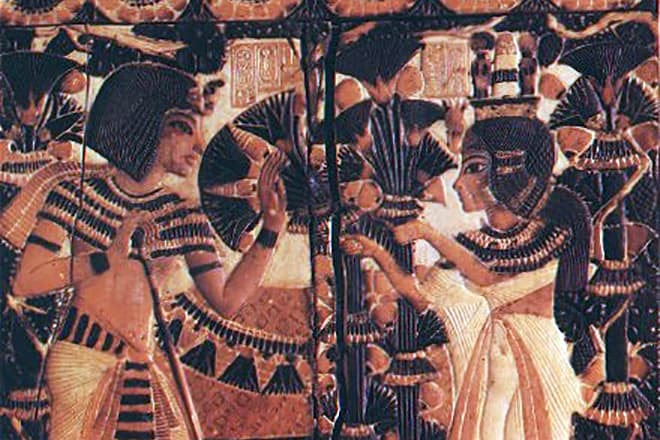

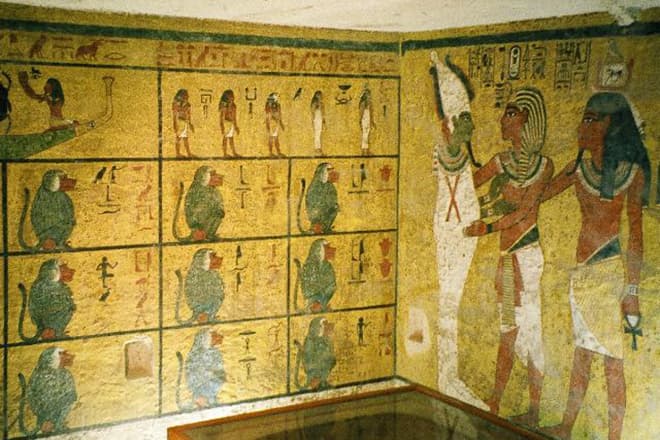

Egyptian art of the Amarna period

Once crowned and after «taking counsel» with the god Amun, Tutankhamun made several endowments that enriched and added to the priestly numbers of the cults of Amun and Ptah. He commissioned new statues of the deities from the best metals and stone and had new processional barques made of the finest cedar from Lebanon and had them embellished with gold and silver. The priests and all of the attending dancers, singers and attendants had their positions restored and a decree of royal protection granted to insure their future stability.[49]

Tutankhamun’s second year as pharaoh began the return to the old Egyptian order. Both he and his queen removed ‘Aten’ from their names, replacing it with Amun and moved the capital from Akhetaten to Thebes. He renounced the god Aten, relegating it to obscurity and returned Egyptian religion to its polytheistic form. His first act as a pharaoh was to remove his father’s mummy from his tomb at Akhetaten and rebury it in the Valley of the Kings. This helped strengthen his reign. Tutankhamun rebuilt the stelae, shrines, and buildings at Karnak. He added works to Luxor as well as beginning the restoration of other temples throughout Egypt that were pillaged by Akhenaten.[50]

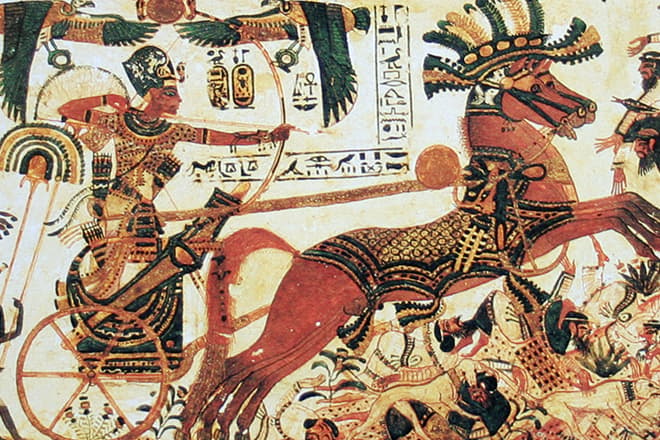

Campaigns, monuments, and construction

The country was economically weak and in turmoil following the reign of Akhenaten. Diplomatic relations with other kingdoms had been neglected, and Tutankhamun sought to restore them, in particular with the Mitanni. Evidence of his success is suggested by the gifts from various countries found in his tomb. Despite his efforts for improved relations, battles with Nubians and Asiatics were recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes. His tomb contained body armor, folding stools appropriate for military campaigns, and bows, and he was trained in archery.[51] However, given his youth and physical disabilities, which seemed to require the use of a cane in order to walk, most historians speculate that he did not personally take part in these battles.[7][52]

Given his age, the king probably had advisers which presumably included Ay (who succeeded Tutankhamun) and General Horemheb, Ay’s possible son in law and successor. Horemheb records that the king appointed him «lord of the land» as hereditary prince to maintain law. He also noted his ability to calm the young king when his temper flared.[52]

In his third regnal year Tutankhamun reversed several changes made during his father’s reign. He ended the worship of the god Aten and restored the god Amun to supremacy. The ban on the cult of Amun was lifted and traditional privileges were restored to its priesthood. The capital was moved back to Thebes and the city of Akhetaten was abandoned.[53] As part of his restoration, the king initiated building projects, in particular at Karnak in Thebes, where he laid out the sphinx avenue leading to the temple of Mut. The sphinxes were originally made for Akhenaten and Nefertiti; they were given new ram heads and small statues of the king.[54] At Luxor temple he completed the decoration of the entrance colonnade of Amenhotep III.[55] Monuments defaced under Akhenaten were restored, and new cult images of the god Amun were created. The traditional festivals were now celebrated again, including those related to the Apis Bull, Horemakhet, and Opet. His Restoration Stela erected in front of Karnak temple says:

The temples of the gods and goddesses … were in ruins. Their shrines were deserted and overgrown. Their sanctuaries were as non-existent and their courts were used as roads … the gods turned their backs upon this land … If anyone made a prayer to a god for advice he would never respond.[56]

A building called the Temple-of-Nebkheperure-Beloved-of-Amun-Who-Puts-Thebes-in-Order, which may be identical to a building called Temple-of-Nebkheperre-in-Thebes, a possible mortuary temple, used recycled talatat from Akhenaten’s east Karnak Aten temples indicating that the dismantling of these temples was already underway.[57] Many of Tutankhamun’s construction projects were uncompleted at the time of his death and were completed by or usurped by his successors, especially Horemheb. The sphinx avenue was completed by his successor Ay and the whole was usurped by Horemheb. The Restoration Stele was usurped by Horemheb; pieces of the Temple-of-Nebkheperure-in-Thebes were recycled into Horemheb’s own building projects.[58]

Health and death

Close-up of Tutankhamun’s head

Tutankhamun was slight of build, and roughly 167 cm (5 ft 6 in) tall.[59][60] He had large front incisors and an overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged.[61] Analysis of the clothing found in his tomb, particularly the dimensions of his loincloths and belts indicates that he had a narrow waist and rounded hips.[62] In attempts to explain both his unusual depiction in art and his early death it has been theorised that Tutankhamun had gynecomastia,[63] Marfan syndrome, Wilson–Turner X-linked intellectual disability syndrome, Fröhlich syndrome (adiposogenital dystrophy), Klinefelter syndrome,[64] androgen insensitivity syndrome, aromatase excess syndrome in conjunction with sagittal craniosynostosis syndrome, Antley–Bixler syndrome or one of its variants.[65] It has also been suggested that he had inherited temporal lobe epilepsy in a bid to explain the religiosity of his great-grandfather Thutmose IV and father Akhenaten and their early deaths.[66] However, caution has been urged in this diagnosis.[67]

In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente conducted X-ray examinations of New Kingdom Pharaoh’s crania and skeletal remains, which included the mummified remains of Tutankhamun. The authors determined that the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty bore strong similarities to contemporary Nubians with slight differences.[68]

In January 2005 Tutankhamun’s mummy was CT scanned. The results showed that the young king had a partially cleft hard palate and possibly a mild case of scoliosis.[69][70] Additionally, he was diagnosed with a flat right foot with hypophalangism, while his left foot was clubbed and had bone necrosis of the second and third metatarsals (Freiberg disease or Köhler disease II).[71] However, the clubfoot diagnosis is disputed.[72] James Gamble instead suggests that the position is a result of Tutankhamun habitually walking on the outside of his foot due to the pain caused by Köhler disease II;[73] this theory has been refuted by members of Hawass’ team.[74] The condition may have forced Tutankhamun to walk with the use of a cane, many of which were found in his tomb.[26] Genetic testing through STR analysis rejected the hypothesis of gynecomastia and craniosynostoses (e.g., Antley–Bixler syndrome) or Marfan syndrome.[7] Genetic testing for STEVOR, AMA1, or MSP1 genes specific for Plasmodium falciparum revealed indications of malaria tropica in 4 mummies, including Tutankhamun’s.[7] This is currently the oldest known genetic proof of the ailment.[75] The team discovered DNA from several strains of the parasite, indicating that he was repeatedly infected with the most severe strain of malaria. His malaria infections may have caused a fatal immune response in the body or triggered circulatory shock.[76] The CT scan also showed that he had experienced a compound left leg fracture. This injury being the result of modern damage was ruled out based on the ragged edges of the fracture; modern damage features sharp edges. Embalming substances were present within the fracture indicating that it was associated with an open wound; no signs of healing were present.[77]

A facial reconstruction of Tutankhamun was carried out in 2005 by the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities and National Geographic. Three separate teams—Egyptian, French, and American—worked separately to approximate the face of the boy king. While the Egyptian and French teams knew their subject was Tutankhamun, the American team worked blind. All teams produced very similar results, but it was that of the French team that was ultimately cast in silicone.[78][79]

Stuart Tyson Smith, Egyptologist and professor of anthropology at University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2008 expressed criticism of the forensic reconstruction in a journal review. He noted that “Tutankhamun’s face” was depicted as “very light-skinned” which reflected a “bias” among media outlets. Smith further added that “Egyptologists have been strangely reluctant to admit that the ancient Egyptians were rather dark-skinned Africans, especially the farther south one goes”.[80]

Cause of death

There are no surviving records of the circumstances of Tutankhamun’s death; it has been the subject of considerable debate and major studies.[81]

Hawass and his team postulate that his death was likely the result of the combination of his multiple weakening disorders, a leg fracture, perhaps as the result of a fall, and a severe malarial infection.[82] However, Timmann and Meyer have argued that sickle cell anemia better fits the pathologies exhibited by the king,[83] a suggestion the Egyptian team has called «interesting and plausible».[84]

Murder by a blow to the head was theorised as a result of the 1968 x-ray which showed two bone fragments inside the skull.[85] This theory was disproved by further analysis of the x-rays and the CT scan. The inter-cranial bone fragments were determined to be the result of the modern unwrapping of the mummy as they are loose and not adherent to the embalming resin.[86] No evidence of bone thinning or calcified membranes, which could be indicative of a fatal blow to the head, were found.[87] It has also been suggested that the young king was killed in a chariot accident due to a pattern of crushing injuries, including the fact that the front part of his chest wall and ribs are missing.[88][89] However, the missing ribs are unlikely to be a result of an injury sustained at the time of death; photographs taken at the conclusion of Carter’s excavation in 1926 show that the chest wall of the king was intact, still wearing a beaded collar with falcon-headed terminals. The absence of both the collar and chest wall was noted in the 1968 x-ray[90] and further confirmed by the CT scan.[70] It is likely that the front part of his chest was removed by robbers during the theft of the beaded collar; the intricate beaded skullcap the king was pictured wearing in 1926 was also missing by 1968.[91]

Tomb

A painted, wooden figure of Tutankhamun found in his royal tomb

Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was unusually small considering his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, causing his mummy to be buried in a tomb intended for someone else. This would preserve the observance of the customary 70 days between death and burial.[92] His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, these robberies likely took place within several months at most of the initial burial. The location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by debris from subsequent tombs, and workers’ houses were built over the tomb entrance.[93]

Rediscovery

The concession rights for excavating the Valley of the Kings was held by Theodore Davis from 1905 until 1914. In that time, he had unearthed ten tombs including the nearly intact but non-royal tomb of Queen Tiye’s parents, Yuya and Thuya. As he continued working there in the later years, he uncovered nothing of major significance.[94] Davis did find several objects in KV58 referring to Tutankhamun, which included knobs and handles bearing his name most significantly the embalming cache of the king (KV54). He believed this to be the pharaoh’s lost tomb and published his findings as such with the line; «I fear the Valley of the Tombs is exhausted».[95][96] In 1907, Howard Carter was invited by William Garstin and Gaston Maspero to excavate for George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon in the Valley. The Earl of Carnarvon and Carter had hoped this would lead to their gaining the concession when Davis gave it up but had to be satisfied with excavations in different parts of the Theban Necropolis for seven more years.[97]

After a systematic search beginning in 1915, Carter discovered the actual tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) in November 1922.[98] An ancient stroke of luck allowed the tomb to survive to modern times. The tomb’s entrance was buried by mounds of debris from the cutting of KV9 over 150 years after Tutankhamun’s burial; ancient workmen’s huts were also built on the site.[99][100] This area remained unexcavated until 1922 due to its proximity to KV9, as excavations would impede tourist access to that tomb.[101] Carter commenced excavations in early November 1922, before the height of the tourist season.[102] The first step of the tomb’s entrance staircase was uncovered on 4 November 1922. According to Carter’s account the workmen discovered the step while digging beneath the remains of the huts; other accounts attribute the discovery to a boy digging outside the assigned work area.[103][i]

By February 1923 the antechamber had been cleared of everything but two sentinel statues. A day and time were selected to unseal the tomb with about twenty appointed witnesses that included Lord Carnarvon, several Egyptian officials, museum representatives and the staff of the Government Press Bureau. On 17 February 1923 at just after two o’clock, the seal was broken.[107]

Contents

Diagram of Tutankhamun’s tomb

There were 5,398 items found in the tomb, including a solid gold coffin, face mask, thrones, archery bows, trumpets, a lotus chalice, two Imiut fetishes, gold toe stalls, furniture, food, wine, sandals, and fresh linen underwear. Howard Carter took 10 years to catalog the items.[108] Recent analysis suggests a dagger recovered from the tomb had an iron blade made from a meteorite; study of artifacts of the time including other artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb could provide valuable insights into metalworking technologies around the Mediterranean at the time.[109][110] Many of Tutankhamun’s burial goods show signs of being adapted for his use after being originally made for earlier owners, probably Smenkhkare or Neferneferuaten or both.[111][112][113]

On 4 November 2007, 85 years to the day after Carter’s discovery, Tutankhamun’s mummy was placed on display in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus to a climate-controlled glass box. The case was designed to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.[114] In 2009, the tomb was closed for restoration by the Ministry of antiquities and the Getty Conservation Institute. While the closure was originally planned for five years to restore the walls affected by humidity, the Egyptian revolution of 2011 set the project back. The tomb re-opened in February 2019.[115]

Rumored curse

For many years, rumors of a «curse of the pharaohs» (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery[116]) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had entered the tomb. The most prominent was George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, who died on 5 April 1923, five months after the discovery of the first step leading down to the tomb on 4 November 1922.[117]

The cause of Carnarvon’s death was pneumonia supervening on [facial] erysipelas (a streptococcal infection of the skin and underlying soft tissue).[118] The Earl had been in an automobile accident in 1901 making him very unhealthy and frail. His doctor recommended a warmer climate so in 1903 the Carnarvons traveled to Egypt where the Earl became interested in Egyptology.[117] Along with the stresses of the excavation, Carnarvon was already in a weakened state when an infection led to pneumonia.[119]

A study showed that of the 58 people who were present when the tomb and sarcophagus were opened, only eight died within a dozen years;[120] Howard Carter died of lymphoma in 1939 at the age of 64.[121] The last survivors included Lady Evelyn Herbert, Lord Carnarvon’s daughter who was among the first people to enter the tomb after its discovery in November 1922, who lived for a further 57 years and died in 1980,[122] and American archaeologist J.O. Kinnaman who died in 1961, 39 years after the event.[123]

Legacy

The «Egyptian Number» of Life, 19 April 1923

Tutankhamun’s fame is primarily the result of his well-preserved tomb and the global exhibitions of his associated artifacts. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter’s The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, «The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt’s Pharaohs has become in death the most renowned».[124]

The discoveries in the tomb were prominent news in the 1920s. Tutankhamen came to be called by a modern neologism, «King Tut». Ancient Egyptian references became common in popular culture, including Tin Pan Alley songs; the most popular of the latter was «Old King Tut» by Harry Von Tilzer from 1923,[125][126] which was recorded by such prominent artists of the time as Jones & Hare[127] and Sophie Tucker.[125] «King Tut» became the name of products, businesses, and the pet dog of U.S. President Herbert Hoover.[128] While The Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibit was touring the United States in 1978, comedian Steve Martin wrote a novelty song King Tut. Originally performed on Saturday Night Live, the song was released as a single and sold over a million copies.[129]

International exhibitions

San Francisco’s M. H. de Young Memorial Museum hosted an exhibition of Tutankhamun artifacts in 2009[130]

Tutankhamun’s artifacts have traveled the world with unprecedented visitorship.[131] The exhibitions began in 1962 when Algeria won its independence from France. With the ending of that conflict, the Louvre Museum in Paris was quickly able to arrange an exhibition of Tutankhamun’s treasures through Christiane Desroches Noblecourt. The French Egyptologist was already in Egypt as part of a UNESCO appointment. The French exhibit drew 1.2 million visitors. Noblecourt had also convinced the Egyptian Minister of Culture to allow British photographer George Rainbird to re-photograph the collection in color. The new color photos as well as the Louvre exhibition began a Tutankhamun revival.[132]

In 1965, the Tutankhamun exhibit traveled to Tokyo National Museum in Tokyo, Japan (21 August–10 October)[133] where it garnered more visitors than the future New York exhibit in 1979. The exhibit next moved to the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art in Kyoto (15 October–28 November)[133] with almost 1.75 million visitors, and then to the Fukuoka Prefectural Cultural Hall in Fukuoka (3 December–26 December).[133] The blockbuster attraction exceeded all other exhibitions of Tutankhamun’s treasures for the next 60 years.[131][134] The Treasures of Tutankhamun tour ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from 30 March until 30 September 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors saw the exhibition.[131][135] The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the United States, Soviet Union, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from 17 November 1976 through 15 April 1979. More than eight million attended.[136][137]

In 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched a tour of Tutankhamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects, this time called Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. It featured the same exhibits as Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter in a slightly different format. It was expected to draw more than three million people but exceeded that with almost four million people attending just the first four tour stops.[138] The exhibition started in Los Angeles, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Chicago, Philadelphia and London before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. An encore of the exhibition in the United States ran at the Dallas Museum of Art.[139] After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, followed by the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.[140]

Tutankhamun exhibition in 2018

The exhibition visited Australia for the first time, opening at the Melbourne Museum for its only Australian stop before Egypt’s treasures returned to Cairo in December 2011.[141]

The exhibition included 80 exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessors in the 18th Dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun’s burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun’s tomb. The exhibition did not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972–1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has decided that damage which occurred to previous artifacts on tours precludes this one from joining them.[142]

In 2018, it was announced that the largest collection of Tutankhamun artifacts, amounting to forty percent of the entire collection, would be leaving Egypt again in 2019 for an international tour entitled; «King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh».[143] The 2019–2022 tour began with an exhibit called; «Tutankhamun, Pharaoh’s Treasures,» which launched in Los Angeles and then traveled to Paris. The exhibit featured at the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris ran from March to September 2019. The exhibit featured one hundred and fifty gold coins, along with various pieces of jewelry, sculpture and carvings, as well as the renowned gold mask of Tutankhamun. Promotion of the exhibit filled the streets of Paris with posters of the event. The exhibit moved to London in November 2019 and was scheduled to travel to Boston and Sydney when the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the tour. On 28 August 2020 the artifacts that made up the temporary exhibition returned to the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and other institutions.[144] The treasures will be permanently housed in the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo, expected to open in November 2022.[145][146]

Ancestry

Tutankhamun ascending family history |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Based on genetic testing and archeological evidence

|

See also

- Anubis Shrine

- Head of Nefertem

- Tutankhamun’s mummy

- Tutankhamun’s meteoric iron dagger

- Tutankhamun’s trumpets

Notes

- ^ Egyptological pronunciation.

- ^ The relief depicts a child in the arms of a nurse outside a chamber in which Meketaten is being mourned by her parents and siblings, which has been interpreted to indicate she died in childbirth.[19]

- ^ Part of this interpretation is based on the inscribed block from Hermopolis, which names a ‘King’s Son’ in conjunction with a ‘King’s Daughter’.[21]

- ^ Tutankhamun’s Horus Name was Ka nakht tut mesut,[3] translated as; Victorious bull, the (very) image of (re)birth.[4]

- ^ His second full nomen (also called the Son of Re Name) was; Tut ankh imen, heqa iunu shemau, translated as; The living image of Amun, Ruler of Southern Heliopolis.[4]

- ^ Tutankahmun’s Nebty or Two Ladies Name was; (1): Nefer hepu, segereh tawy,[3] translated as; Perfect of laws, who has quieted down the Two Lands.[4] (2): Nefer hepu, segereh tawy sehetep netjeru nebu, translated as; Perfect of laws, who has quieted down the Two Lands and pacified all the gods.[4] (3): Wer ah imen, translated as; The great one of the palace of Amun.[46]

- ^ Tutankhamun’s Gold Falcon Name was: (1): Wetjes khau, sehetep netjeru[3] translated as; Elevated of appearances, who has satisfied the gods.[4] *Gold Falcon name (2): Wetjes khau it ef ra, translates as; Who has elevated the appearances of his father Re.[46]

- ^ Tutankhamun’s Prenomen (Throne Name) was: Neb kheperu re,[3][46] translated as: The possessor of the manifestation of Re.[4] which had an epithet added: Heqa maat, translated as; Ruler of Maat.[46]

- ^ Karl Kitchen, a reporter for the Boston Globe, wrote in 1924 that a boy named Mohamed Gorgar had found the step; he interviewed Gorgar, who did not say whether the story was true.[104] Lee Keedick, the organiser of Carter’s American lecture tour, said Carter attributed the discovery to an unnamed boy carrying water for the workmen.[105] Many recent accounts, such as the 2018 book Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh by the Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, identify the water-boy as Hussein Abd el-Rassul, a member of a prominent local family. Hawass says he heard this story from el-Rassul in person. Another Egyptologist, Christina Riggs, suggests the story may instead be a conflation of Keedick’s account, which was widely publicised by the 1978 book Tutankhamun: The Untold Story by Thomas Hoving, with el-Rassul’s long-standing claim to have been the boy who was photographed wearing one of Tutankhamun’s pectorals in 1926.[106]

Citations

- ^ Clayton 2006, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d e Osing & Dreyer 1987, pp. 110–123.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Digital Egypt for Universities: Tutankhamun». University College London. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Leprohon 2013, p. 206.

- ^ Hawass et al. 2010, pp. 640–641.

- ^ «Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen». Collins English Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hawass et al. 2010, pp. 638–647.

- ^ a b Hawass & Saleem 2011, pp. W829–W831.

- ^ Hawass 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Schwarzer, Marjorie; Museums, American Association of (2006). Riches, Rivals & Radicals: 100 Years of Museums in America. American Association of Museums. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-933253-05-3. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Williamson 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Dodson 2009, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 276.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2010, p. 149.

- ^ Tawfik, Thomas & Hegenbarth-Reichardt 2018, p. 180.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, p. 167.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 13.

- ^ Arnold et al. 1996, p. 115.

- ^ Brand & Cooper 2009, p. 88.

- ^ Dodson 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Gabolde 2000, pp. 107–110.

- ^ Tawfik, Thomas & Hegenbarth-Reichardt 2018, pp. 179–195.

- ^ Zivie 1998, pp. 33–54.

- ^ Gundlach & Taylor 2009, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e Hawass et al. 2010, pp. 642–645.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 123.

- ^ Gad et al. 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2010, p. 146.

- ^ Dodson 2009, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Eaton-Krauss 2015, pp. 6–10.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 89.

- ^ Morkot 2004, p. 161.

- ^ Robinson 2009, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Collier & Manley 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Hawass 2004, p. 56.

- ^ «Classroom TUTorials: The Many Names of King Tutankhamun» (PDF). Michael C. Carlos Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Baker & Baker 2001, p. 137.

- ^ Dodson 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Cooney 2018, p. 361.

- ^ Barclay 2006, p. 62.

- ^ Booysen 2013, p. 188.

- ^ Redford 2003, p. 85.

- ^ Booth 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Toby A.H. Wilkinson (11 September 2002). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-134-66420-7.

- ^ a b c d e Leprohon 2013, pp. 1–15.

- ^ The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. Egypt Exploration Fund. 1998. p. 212.

- ^ a b Eaton-Krauss 2015, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Darnell & Manassa 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Mey Zaki (2008). Legacy of Tutankhamun: Art and History. American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-977-17-4930-1.

- ^ Gilbert, Holt & Hudson 1976, pp. 28–9.

- ^ a b Booth 2007, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Erik Hornung, Akhenaten and the Religion of Light, Translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8014-8725-0.

- ^ Forbes, D. C. (2000). «Seven Battered Osiride Figures in the Cairo Museum and the Sphinx Avenue of Tutankhamen at Karnak». Amarna Letters. 4: 82–87.

- ^ Dodson 2009, p. 70.

- ^ Hart, George (1990). Egyptian Myths. University of Texas Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-292-72076-3.

- ^ Dodson 2009, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Dodson 2009, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 94.

- ^ Carter, Howard; Derry, Douglas E. (1927). The Tomb of Tutankhamen. Cassel and Company, LTD. p. 157.

- ^ Pausch, Niels Christian; Naether, Franziska; Krey, Karl Friedrich (December 2015). «Tutankhamun’s Dentition: The Pharaoh and his Teeth». Brazilian Dental Journal. 26 (6): 701–704. doi:10.1590/0103-6440201300431. PMID 26963220. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Vogelsang-Eastwood, G. M. (1999). Tutankhamun’s Wardrobe : garments from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Rotterdam: Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn. pp. 18–19. ISBN 90-5613-042-0.

- ^ Paulshock, Bernadine Z. (11 July 1980). «Tutankhamun and His Brothers». JAMA. 244 (2): 160–164. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310020036024.

- ^ Walshe 1973, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Markel, H. (17 February 2010). «King Tutankhamun, modern medical science, and the expanding boundaries of historical inquiry». JAMA. 303 (7): 667–668. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.153. PMID 20159878.

- ^ Ashrafian, Hutan (September 2012). «Familial epilepsy in the pharaohs of ancient Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty». Epilepsy & Behavior. 25 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.06.014. PMID 22980077. S2CID 20771815.

- ^ Cavka, Mislav; Kelava, Tomislav (April 2013). «Comment on: Familial epilepsy in the pharaohs of ancient Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty». Epilepsy & Behavior. 27 (1): 278. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.11.044. PMID 23291226. S2CID 43043052.

- ^ An X-ray atlas of the royal mummies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1980. pp. 207–208. ISBN 0226317455.

- ^ Hawass et al. 2010, p. 642.

- ^ a b Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 95.

- ^ Hussein, Kais; Matin, Ekatrina; Nerlich, Andreas G. (2013). «Paleopathology of the juvenile Pharaoh Tutankhamun—90th anniversary of discovery». Virchows Archiv. 463 (3): 475–479. doi:10.1007/s00428-013-1441-1. PMID 23812343. S2CID 1481224.

- ^ Marchant, Jo. «New twist in the tale of Tutankhamun’s club foot». New Scientist. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Gamble, James G. (23 June 2010). «King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise». JAMA. 303 (24): 2472, author reply 2473–5. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.820. PMID 20571009.

- ^ Gad, Yehia Z.; Selim, Ashraf; Pusch, Carsten M. (23 June 2010). «King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise—Reply». JAMA. 303 (24): 2471. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.823.

- ^ Braun 2012, p. 221.

- ^ Mackowiak 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, pp. 96–97.

- ^ «CT scans reveal King Tut’s face». NBC News.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 252.

- ^ Smith, Stuart Tyson (1 January 2008). «Review of From Slave to Pharaoh: The Black Experience of Ancient Egypt by Donald Redford». Near Eastern Archaeology 71:3.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi. «Tutankhamon, segreti di famiglia». National Geographic (in Italian). Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Hawass et al. 2010.

- ^ Timmann & Meyer 2010, p. 1279.

- ^ Marchant 2010.

- ^ Harrison, R. G.; Abdalla, A. B. (March 1972). «The remains of Tutankhamun». Antiquity. 46 (181): 11. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00053072. S2CID 162450016.

- ^ Hawass & Saleem 2016, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Boyer, R.S.; Rodin, E.A.; Grey, T.C.; Connolly, R.C. (2003). «The skull and cervical spine radiographs of Tutankhamen: a critical appraisal» (PDF). AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 24 (6): 1142–7. PMC 8149017. PMID 12812942. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Knapp, Alex. «Forensic Experts Claim That King Tut Died In A Chariot Accident». Forbes. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Harer, W. Benson (2011). «New evidence for King Tutankhamen’s death: his bizarre embalming». The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 97 (1): 228–233. doi:10.1177/030751331109700120. JSTOR 23269903. S2CID 194860857.

- ^ Harrison, R. G.; Abdalla, A. B. (March 1972). «The remains of Tutankhamun». Antiquity. 46 (181): 9. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00053072. S2CID 162450016.

- ^ Forbes, Dennis; Ikram, Salima; Kamrin, Janice (2007). «Tutankhamen’s Missing Ribs». KMT. Vol. 18, no. 1. p. 56.

- ^ «The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendour in the New Kingdom«, Zahi Hawass, p. 61, American University in Cairo Press, 2004, ISBN 977-424-836-8

- ^ Mascort, Maite (12 April 2018). «How Howard Carter Almost Missed Finding King Tut’s Tomb». National Geographic. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ T. G. H. James (2006). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-84511-258-5.

- ^ Davis, Theodore M. (2001). The tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou (Paperback ed.). Duckworth Publishers. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ Richard H. Wilkinson; Kent R. Weeks (2016). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. p. 491. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- ^ Howard Carter (23 October 2014). The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume 1: Search, Discovery and Clearance of the Antechamber. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4725-7687-3.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 81.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 9, 11.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ James 2000, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Thompson 2018, p. 46.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Riggs 2021, p. 297.

- ^ James 2000, p. 255.

- ^ Riggs 2021, pp. 296–298, 407.

- ^ Howard Carter; A. C. Mace (19 October 2012). The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. Courier Corporation. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-486-14182-4.

- ^ Williams, A. R. (24 November 2015). «King Tut: The Teen Whose Death Rocked Egypt». National Geographic News. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Daniela Comelli; Massimo D’orazio; Luigi Folco; Mahmud El‐Halwagy; Tommaso Frizzi; Roberto Alberti; Valentina Capogrosso; Abdelrazek Elnaggar; Hala Hassan; Austin Nevin; Franco Porcelli; Mohamed G. Rashed; Gianluca Valentini; et al. (2016). «The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun’s iron dagger blade — Comelli — 2016 — Meteoritics & Planetary Science — Wiley Online Library». Meteoritics and Planetary Science. 51 (7): 1301. Bibcode:2016M&PS…51.1301C. doi:10.1111/maps.12664.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (2 June 2016). «King Tut’s Dagger Made of ‘Iron From the Sky,’ Researchers Say». The New York Times. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ Reeves 2015, p. 523.

- ^ Tawfik, Thomas & Hegenbarth-Reichardt 2018, pp. 181, 192.

- ^ Ridley 2019, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Michael McCarthy (5 October 2007). «3,000 years old: the face of Tutankhaten». The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007.

- ^ Nada Deyaa’ (3 February 2019). «Long awaited for Tutankhamun’s tomb reopened after restoration». Daily News Egypt. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Hankey, Julie (2007). A Passion for Egypt: Arthur Weigall, Tutankhamun and the ‘Curse of the Pharaohs’. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-1-84511-435-0.

- ^ a b Kathryn A. Bard (27 January 2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-470-67336-2.

- ^ Carl Nicholas Reeves (1993). Howard Carter: Before Tutankhamun. H.N. Abrams. pp. 62–156. ISBN 978-0-8109-3186-2.

- ^ Lorna Oakes; Lucia Gahlin (2005). Ancient Egypt: an illustrated reference to the myths, religions, pyramids and temples of the land of the pharaohs. Hermes House. p. 495. ISBN 978-1-84477-451-7.

- ^ Gordon, Stuart (1995). The Book of Spells, Hexes, and Curses. New York: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-08065-1675-2.

- ^ David Vernon in Skeptical – a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed. Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0-7316-5794-2, p. 25.

- ^ Bill Price (21 January 2009). Tutankhamun, Egypt’s Most Famous Pharaoh. Harpenden : Pocket Essentials. p. 138. ISBN 9781842432402.

- ^ «Death Claims Noted Biblical Archaeologist». Lodi News-Sentinel. 8 September 1961. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Carter, Howard; Mace, A.C. (1977). The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486235009.

- ^ a b Coniam, Matthew (2017). Egyptomania Goes to the Movies: From Archaeology to Popular Craze to Hollywood Fantasy. McFarland & Company. pp. 42–44. ISBN 9781476668284. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

…on May 19, [1923] when Motion Picture News reported that to further assist its exhibitors Fox had arranged with Harry Von Tilzer for a special and complete orchestration titled «Old King Tut» … Sophie Tucker performed it in The Pepper Box Revue and recorded it for Okeh Records both with sufficient success that she took out an ad in Variety …

- ^ Paul, Gill. «1920s «Tutmania» and its Enduring Echoes | History News Network». historynewsnetwork.org. History News Network. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

Tutmania seeped into popular culture with the 1923 song “Old King Tut”, a stage magician who called himself «Carter the Great», and the iconic 1932 horror film The Mummy, written by a journalist who had covered the discovery of the tomb. President Herbert Hoover even called his pet dog King Tut!

- ^ Edward Chaney (2020). «‘Mummy First, Statue After’: Wyndham Lewis, Diffusionism, Mosaic Distinctions and the Egyptian Origins of Art». In Dobson, Eleanor; Tonks, Nichola (eds.). Ancient Egypt in the Modern Imagination: Art, Literature and Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 9781786736703.

Tutankhamun’s popularity was such that a hit song … was launched by Billy Jones and Ernie Hare under the title ‘Old King Tut Was a (Wise Old Nut)’.

- ^ «The First Family’s Pets». hoover.archives.gov. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ «Sensational Steve Martin». Time. 24 August 1987. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ Travel and Tourism Market Research Yearbook. Richard K. Miller Associates. 2008. p. 200. ISBN 9781577831365.

- ^ a b c Sarah Anne Hughes (20 June 2019). Museum and Gallery Publishing: From Theory to Case Study. Taylor & Francis. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-317-09309-1.

- ^ William Carruthers (11 July 2014). Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures. Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-135-01457-5.

- ^ a b c «ツタンカーメン展» (in Japanese). Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties. 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Thomas R.H. Havens (14 July 2014). Artist and Patron in Postwar Japan: Dance, Music, Theater, and the Visual Arts, 1955-1980. Princeton University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4008-5539-1.

- ^ «Record visitor figures». British Museum. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Mona L. Russell (2013). Egypt. ABC-CLIO. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-59884-233-3.

- ^ Riggs 2018, p. 216.

- ^ Paul Cartledge; Fiona Rose Greenland (20 January 2010). Responses to Oliver Stone’s Alexander: Film, History, and Cultural Studies. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-299-23283-2.

- ^ Fritze 2016, p. 242.

- ^ Nici 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Proceedings of the 1st International Conference in Safety and Crisis Management in the Construction, Tourism and SME Sectors. Universal-Publishers. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-61233-557-5.

- ^ Jenny Booth (6 January 2005). «CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle». The Times. London: Times Newspapers Limited.

- ^ «Tutankhamun exhibition to be hosted in Sydney in 2021 — Egypt Today». Egypt Today. 16 June 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Dowson, Thomas (22 February 2019). «Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh 2019 – 2023». Archaeology Travel. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Mira Maged (20 March 2019). «King Tutankhamun exhibition in Paris sells 130,000 tickets — Egypt Independent». Al-Masry Al-Youm. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ «Blockbuster King Tut Exhibitions and their Fascinating History». Art & Object. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

References

- Arnold, Dorothea; Metropolitan Museum of Art Staff; Green, L.; Allen, James P. (1996). The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-816-4. OCLC 35292712.

- Baker, Rosalie F.; Baker, Charles F. (2001). Ancient Egyptians: People of the Pyramids. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-512221-3.

- Barclay, John M.G. (2006). Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary, Volume 10: Against Apion. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-0405-7.

- Booysen, Riaan (2013). Thera and the Exodus: The Exodus Explained in Terms of Natural Phenomena and the Human Response to It. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78099-450-5.

- Brand, Peter Peter James; Cooper, Louise (2009). Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17644-7. OCLC 318869912.

- Braun, David (2012). National Geographic Tales of the Weird: Unbelievable True Stories. National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-0965-9.

- Booth, Charlotte (2007). The Boy Behind the Mask: Meeting the Real Tutankhamun. Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8. OCLC 191804020.

- Chyla, Julia; Rosińska-Balik, Karolina; Debowska-Ludwin, Joanna (2017). Current Research in Egyptology 17. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-603-5. OCLC 1029884966.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28628-9. OCLC 869729880.

- Collier, Mark; Manley, Bill (2003). How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Step-by-step Guide to Teach Yourself. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23949-4. OCLC 705578614.

- Cooney, Kathlyn M.; Jasnow, Richard (2015). Joyful in Thebes: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Betsy M. Bryan. Lockwood Press. ISBN 978-1-937040-41-3. OCLC 960643348.

- Cooney, Kara (30 October 2018). When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt. National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-1978-8. OCLC 1100619021.

- Darnell, John Coleman; Manassa, Colleen (3 August 2007). Tutankhamun’s Armies: Battle and Conquest During Ancient Egypt’s Late Eighteenth Dynasty. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-74358-3.

- Dodson, Aidan (2009). Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-1-61797-050-4. OCLC 1055144573.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2010). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28857-3.

- Eaton-Krauss, Marianne (2015). The Unknown Tutankhamun. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4725-7563-0. OCLC 1049775714.

- Gabolde, Marc (2000). D’Akhenaton à Toutânkhamon. Université Lumière-Lyon 2, Institut d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’antiquité. ISBN 9782911971020. OCLC 607262790.

- Gad, Yehia; Ismail, Somaia; Fathalla, Dina; Khairat, Rabab; Fares, Suzan; Gad, Ahmed Zakaria; Saad, Rama; Moustafa, Amal; ElShahat, Eslam; Mandil, Naglaa; Fateen, Mohamed; Elleithy, Hisham; Wasef, Sally; Zink, Albert; Hawass, Zahi; Pusch, Carsten (2020). «Maternal and paternal lineages in King Tutankhamun’s family». Guardian of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of Zahi Hawass. Czech Institute of Egyptology. pp. 1–23. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Gilbert, Katherine Stoddert; Holt, Joan K.; Hudson, Sara, eds. (1976). Treasures of Tutankhamun. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-156-1. OCLC 865140073.

- Gundlach, Rolf; Taylor, John H. (2009). 4. Symposium Zur Ägyptischen Königsideologie. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05888-9. OCLC 500749022.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2016). Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-685-8. OCLC 1010951566.

- Hawass, Zahi; et al. (17 February 2010). «Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family» (PDF). The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 638–647. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. PMID 20159872. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Hawass, Zahi (2004). The Golden Age of Tutankhamun. American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-977-424-836-8. OCLC 56358390.

- Hawass, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar (2016). Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-977-416-673-0. OCLC 1078493215.

- Hawass, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar (2011). «Mummified Daughters of King Tutankhamun: Archeologic and CT Studies». American Journal of Roentgenology. 197 (5): W829–W836. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.6837. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 22021529.

- Hoving, Thomas (2002). Tutankhamun: The Untold Story. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-1-4617-3214-3. OCLC 3965932.

- James, T. G. H. (2000). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun, Second Edition. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-615-7.

- Kozma, Chahira (2008). «Skeletal dysplasia in ancient Egypt». American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 146A (23): 3104–3112. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32501. ISSN 1552-4825. PMID 19006207. S2CID 20360474.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Mackowiak, Philip A. (2013). Diagnosing Giants: Solving the Medical Mysteries of Thirteen Patients Who Changed the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-936114-4.

- Marchant, Jo (25 June 2010). «Tutankhamen ‘killed by sickle-cell disease’«. New Scientist. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Morkot, Robert (10 November 2004). The Egyptians: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-48857-5. OCLC 60448544.

- Nici, John (2015). Famous Works of Art—And How They Got That Way. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-4955-4. OCLC 1035635529.

- Osing, Jürgen; Dreyer, Günter (1987). Form und Mass: Beiträge zur Literatur, Sprache und Kunst des alten Ägypten : Festschrift für Gerhard Fecht zum 65. Geburtstag am 6. Februar 1987. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-02704-5.

- Redford, Donald B. (2003). The Oxford Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology. Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-425-19096-8.

- Reeves, Carl Nicholas (1990). The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27810-9. OCLC 1104938097.

- Reeves, Nicholas (2015). «Tutankhamun’s Mask Reconsidered (2015)». Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar. 19: 511–526. Retrieved 7 September 2019 – via Academia.edu.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings. London: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 809290016.

- Ridley, Ronald T. (2019). Akhenaten: A Historian’s View. Cairo and New York: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-793-5. OCLC 8993387156.

- Riggs, Christina (2018). Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-03853-0. OCLC 1114957945.

- Roberts, Peter (2006). HSC Ancient History. Pascal Press. ISBN 978-1-74125-179-1. OCLC 225398561.

- Riggs, Christina (2021). Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-0121-2.

- Robinson, Andrew (27 August 2009). Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-19-956778-2. OCLC 654777745.

- Tawfik, Tarek; Thomas, Susanna; Hegenbarth-Reichardt, Ina (2018). «New Evidence for Tutankhamun’s Parents: Revelations from the Grand Egyptian Museum». Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. 74: 179–195. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Thompson, Jason (2018). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology, 3. From 1914 to the Twenty-First Century. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-760-7.

- Timmann, Christian; Meyer, Christian G. (2010). «Malaria, mummies, mutations: Tutankhamun’s archaeological autopsy». Tropical Medicine & International Health. 15 (11): 1278–1280. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02614.x. ISSN 1365-3156. PMID 20723182. S2CID 9019947. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2012). Tutankhamen: The Search for an Egyptian King. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02020-1.

- Walshe, J.M. (January 1973). «Tutankhamun: Klinefelter’s Or Wilson’s?». The Lancet. 301 (7794): 109–110. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(73)90516-3. PMID 4118642.

- Williamson, Jacquelyn (2015). «Amarna Period». In Wendrich, Willeke (ed.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UC Los Angeles.

- Winstone, H. V. F. (2006). Howard Carter and the Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, Revised Edition. Barzan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905521-04-3.

- Zivie, A. (1998). «La nourrice royale Maïa et ses voisins: cinq tombeaux du Nouvel Empire récemment découverts à Saqqara». Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 142 (1).

Further reading

- Andritsos, John. Social Studies of Ancient Egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006.

- Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story. Putnam Adult, 13 April 1998, ISBN 0-425-16689-9 (paperback), ISBN 0-399-14383-1 (hardcover), ISBN 0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding).

- Carter, Howard and Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Courier Dover Publications, 1 June 1977, ISBN 0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discovery and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible.

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamun: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover), ISBN 0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback).

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: The CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Haag, Michael. The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty. London 2005. ISBN 1-84353-554-8.

- Hoving, Thomas. The Search for Tutankhamun: The Untold Story of Adventure and Intrigue Surrounding the Greatest Modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, 15 October 1978, ISBN 0-671-24305-5 (hardcover), ISBN 0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb.

- James, T. G. H. Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, 1 September 2000, ISBN 1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects.

- Neubert, Otto. Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings. London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972, ISBN 0-583-12141-1 (paperback) First hand account of the discovery of the Tomb.

- Rossi, Renzo. Tutankhamun. Cincinnati (Ohio) 2007 ISBN 978-0-7153-2763-0, a work all illustrated and coloured.

External links

- Grim secrets of Pharaoh’s city—BBC News

- Tutankhamun and the Age of the Golden Pharaohs website

- British Museum Tutankhamun highlight

- «Swiss geneticists examine Tutankhamun’s genetic profile» by Reuters

- Ultimate Tut Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

| Tutankhamun | |

|---|---|

| Tutankhaten, Tutankhamen[1] | |

Tutankhamun’s golden mask |

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | c. 1332 – 1323 BC, New Kingdom (18th Dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Neferneferuaten |

| Successor | Ay (granduncle/grandfather-in-law) |

|

Royal titulary |

|

| Consort | Ankhesenamun (half-sister) |

| Children | 2 (317a and 317b) |

| Father | KV55 mummy,[5] identified as most likely Akhenaten |

| Mother | The Younger Lady |

| Born | c. 1341 BC |

| Died | c. 1323 BC (aged 18–19) |

| Burial | KV62 |

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen[a] ( ;[6] Ancient Egyptian: twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn; c. 1341 BC – 1323 BC), also referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh. Having ruled over the New Kingdom of Egypt, he was the last of his royal family to exercise governance during the Eighteenth Dynasty, with his reign lasting from c. 1332 BC until c. 1323 BC in the conventional Egyptian chronology. Through DNA testing, his father was identified as the mummy within tomb KV55 and his mother was identified as a mummy from tomb KV35, with his mother having been his father’s sister. The mummy of Tutankhamun’s father is speculated to be of the pharaoh Akhenaten, though this is disputed; the mummy of Tutankhamun’s mother is informally called «The Younger Lady» but is otherwise unknown.[7]

Tutankhamun took the throne at eight or nine years of age, under the unprecedented viziership of his eventual successor, Ay, to whom he may have been related. Within tomb KV21, the mummy KV21A was identified as having been the biological mother of Tutankhamun’s two daughters — it is therefore speculated that this mummy is of his only known wife, Ankhesenamun, who was his paternal half-sister. Their two daughters were identified as the 317a and 317b mummies; daughter 317a was born prematurely at 5–6 months of pregnancy while daughter 317b was born at full-term, though both died in infancy.[8] His names — Tutankhaten and Tutankhamun — are thought to have meant «living image of Aten» and «living image of Amun» in the ancient Egyptian language, with the god Aten having been replaced by the god Amun after Akhenaten’s death. Some Egyptologists, including Battiscombe Gunn, have claimed that the translation may be incorrect, instead being closer to «the-life-of-Aten-is-pleasing» or «one-perfect-of-life-is-Aten» (latter translation by Gerhard Fecht [de]).

Tutankhamun restored the ancient Egyptian religion against Akhenaten’s Atenism and also relocated Egypt’s capital back to Thebes, undoing Akhenaten’s earlier relocation of the capital to Amarna. He also enriched and endowed the priestly orders of two important cults, initiated a restoration process for old monuments that were damaged during the Amarna Period, and reburied his father’s remains in the Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun suffered from a deformed left foot and bone necrosis, which rendered him physically disabled and dependent on assistive canes. He also had other health issues, including scoliosis, and had contracted several strains of malaria.

In 1922, a team led by British Egyptologist Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings excavated Tutankhamun’s tomb, in an effort that was funded by British aristocrat George Herbert.[9] The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb received worldwide press coverage; with over 5,000 artifacts, it gave rise to renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun’s mask, now preserved at the Egyptian Museum, remains a popular symbol. The deaths of some individuals who were involved in the unearthing of Tutankhamun’s mummy have been popularly attributed to the «curse of the pharaohs» due to the similarity of their circumstances. Some of his treasure has traveled worldwide with unprecedented response; the Egyptian government allowed tours beginning in 1961. Tutankhamun has, since the discovery of his intact tomb, been referred to as «King Tut» in colloquial terms.[10]

Family

Tutankhamun, whose original name was Tutankhaten or Tutankhuaten, was born during the reign of Akhenaten, during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[11] Akhenaten’s reign was characterized by a dramatic shift in ancient Egyptian religion, known as Atenism, and the relocation of the capital to the site of Amarna, which gave its name to the modern term for this era, the Amarna Period.[12] Toward the end of the Amarna Period, two other pharaohs appear in the record who were apparently Akhenaten’s co-regents: Neferneferuaten, a female ruler who may have been Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti or his daughter Meritaten; and Smenkhkare, whom some Egyptologists believe was the same person as Neferneferuaten but most regard as a distinct figure.[13] It is uncertain whether Smenkhkare’s reign outlasted Akhenaten’s, whereas Neferneferuaten is now thought to have become co-regent shortly before Akhenaten’s death and to have reigned for some time after it.[14]

An inscription from Hermopolis refers to «Tutankhuaten» as a «king’s son», and he is generally thought to have been the son of Akhenaten,[15] although some suggest instead that Smenkhkare was his father.[16] Inscriptions from Tutankhamun’s reign treat him as a son of Akhenaten’s father, Amenhotep III, but that is only possible if Akhenaten’s 17-year reign included a long co-regency with his father,[17] a possibility that many Egyptologists once supported but is now being abandoned.[18]

While some suggestions have been made that Tutankhamun’s mother was Meketaten, the second daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, based on a relief from the Royal Tomb at Amarna,[b] this possibility has been deemed unlikely given that she was about 10 years old at the time of her death.[20] Another interpretation of the relief names Nefertiti as his mother.[c][22] Meritaten has also been put forward as his mother based on a re-examination of a box lid and coronation tunic found in his tomb.[23] Tutankhamun was wet nursed by a woman named Maia, known from her tomb at Saqqara.[24][25]

In 2008, genetic analysis was carried out on the mummified remains of Tutankhamun and others thought or known to be New Kingdom royalty by a team from University of Cairo. The results indicated that his father was the mummy from tomb KV55, identified as Akhenaten, and that his mother was the mummy from tomb KV35, known as the «Younger Lady», who was found to be a full sister of her husband.[26] The team reported it was over 99.99 percent certain that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[27] More recent genetic analysis, published in 2020, revealed Tutankhamun had the haplogroups YDNA R1b, which originated in Europe and which today makes up 50–90% of the genetic pool of modern western Europeans, and mtDNA K, which originated in the Near East. He shares this Y-haplogroup with his father, the KV55 mummy (Akhenaten), and grandfather, Amenhotep III, and his mtDNA haplogroup with his mother, The Younger Lady, his grandmother, Tiye, and his great-grandmother, Thuya, upholding the results of the earlier genetic study. The profiles for Tutankhamun and Amenhotep III were incomplete and the analysis produced differing probability figures despite having concordant allele results. Because the relationships of these two mummies with the KV55 mummy had previously been confirmed in an earlier study, the haplogroup prediction of both mummies could be derived from the full profile of the KV55 data.[28]

The identity of The Younger Lady is unknown but she cannot be Nefertiti, as she was not known to be a sister of Akhenaten.[29] However, researchers such as Marc Gabolde and Aidan Dodson claim that Nefertiti was indeed Tutankhamun’s mother. In this interpretation of the DNA results, the genetic closeness is not due to a brother-sister pairing but the result of three generations of first-cousin marriage, making Nefertiti a first cousin of Akhenaten.[30] The validity and reliability of the genetic data from mummified remains has been questioned due to possible degradation due to decay.[31]

When Tutankhaten became king, he married Ankhesenpaaten, one of Akhenaten’s daughters, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun.[32] They had two daughters, neither of whom survived infancy.[26] While only an incomplete genetic profile was obtained from the two mummified foetuses, it was enough to confirm that Tutankhamun was their father.[26] Likewise, only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained so far. KV21A has been suggested as the mother of the foetuses but the data is not statistically significant enough to allow her to be securely identified as Ankhesenamun.[26] Computed tomography studies published in 2011 revealed that one daughter was born prematurely at 5–6 months of pregnancy and the other at full-term, 9 months.[8] Tutankhamun’s death marked the end of the royal line of the 18th Dynasty.[33]

Reign

Tutankhamun was between eight and nine years of age when he ascended the throne and became pharaoh,[36] taking the throne name Nebkheperure.[37] He reigned for about nine years.[38] During Tutankhamun’s reign the position of Vizier had been split between Upper and Lower Egypt. The principal vizier for Upper Egypt was Usermontu. Another figure named Pentju was also vizier but it is unclear of which lands. It is not entirely known if Ay, Tutankhamun’s successor, actually held this position. A gold foil fragment from KV58 seems to indicate, but not certainly, that Ay was referred to as a Priest of Maat along with an epithet of «vizier, doer of maat.» The epithet does not fit the usual description used by the regular vizier but might indicate an informal title. It might be that Ay used the title of vizier in an unprecedented manner.[39]

An Egyptian priest named Manetho wrote a comprehensive history of ancient Egypt where he refers to a king named Orus, who ruled for 36 years and had a daughter named Acencheres who reigned twelve years and her brother Rathotis who ruled for only nine years.[40][41] The Amarna rulers are central in the list but which name corresponds with which historic figure is not agreed upon by researchers. Orus and Acencheres have been identified with Horemheb and Akhenaten and Rathotis with Tutankhamun. The names are also associated with Smenkhkare, Amenhotep III, Ay and the others in differing order.[42]

Kings were venerated after their deaths through mortuary cults and associated temples. Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped in this manner during his lifetime.[43] A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Ra and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by sin. Temples of his cult were built as far away as in Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king, indicative of the universality of his cult.[44]

In order for the pharaoh, who held divine office, to be linked to the people and the gods, special epithets were created for them at their accession to the throne. The ancient Egyptian titulary also served to demonstrate one’s qualities and link them to the terrestrial realm. The five names were developed over the centuries beginning with the Horus name.[d][45][46] Tutankhamun’s[e] original nomen, Tutankhaten,[47] did not have a Nebty name[f] or a Gold Falcon name[g] associated with it[48] as nothing has been found with the full five-name protocol.[h] Tutankhaten was believed to mean «Living-image-of-Aten» as far back as 1877; however, not all Egyptologists agree with this interpretation. English Egyptologist Battiscombe Gunn believed that the older interpretation did not fit with Akhenaten’s theology. Gunn believed that such an name would have been blasphemous. He saw tut as a verb and not a noun and gave his translation in 1926 as The-life-of-Aten-is-pleasing. Professor Gerhard Fecht also believed the word tut was a verb. He noted that Akhenaten used tit as a word for ‘image’, not tut. Fecht translated the verb tut as «To be perfect/complete». Using Aten as the subject, Fecht’s full translation was «One-perfect-of-life-is-Aten». The Hermopolis Block (two carved block fragments discovered in Ashmunein) has a unique spelling of the first nomen written as Tutankhuaten; it uses ankh as a verb, which does support the older translation of Living-image-of-Aten.[48]

End of Amarna period

Egyptian art of the Amarna period

Once crowned and after «taking counsel» with the god Amun, Tutankhamun made several endowments that enriched and added to the priestly numbers of the cults of Amun and Ptah. He commissioned new statues of the deities from the best metals and stone and had new processional barques made of the finest cedar from Lebanon and had them embellished with gold and silver. The priests and all of the attending dancers, singers and attendants had their positions restored and a decree of royal protection granted to insure their future stability.[49]