Сила трения появляется, когда две поверхности соприкасаются и движутся относительно друг друга. Процесс изучает физика, в частности механика. Она рассматривает основные законы, которым поддаются тела при их движении и взаимодействии, выясняет причины, влияющие на изменение положения предметов.

Определение и природа силы трения

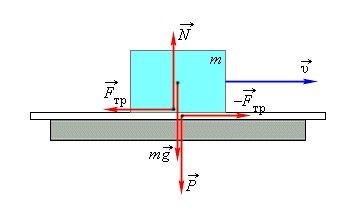

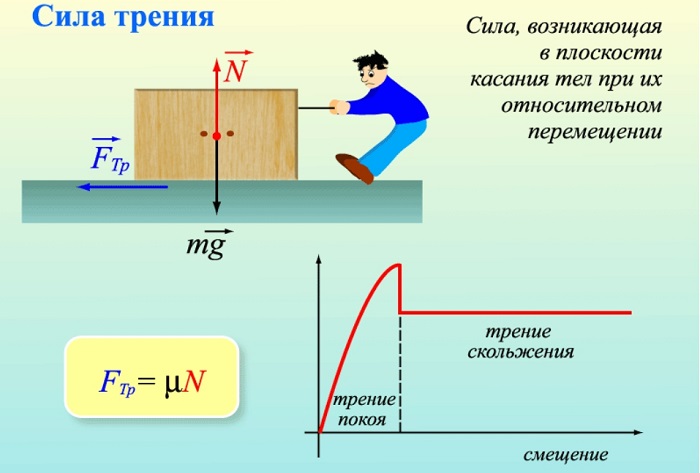

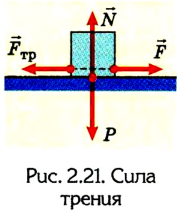

Сила трения Fтр возникает при касании двух тел. Она создает препятствия для их дальнейшего движения.

Это происходит при взаимодействии атомов и молекул, из которых состоят предметы. Поэтому природа ее появления – электромагнитные волны. Она действует в двух направлениях, направлена на оба тела.

При этом ее значение по модулю не изменяется. Если на одно из двух соприкасающихся тел действует сила, то она оказывает влияние и на другое.

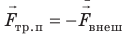

На предмет, остающийся без движения, влияет сила трения покоя. Пока ее значение не превысит внешнее вмешательство, пытающееся сместить предмет, он не изменит положение.

Когда же ее величина возрастет до определенного предела, произойдет перемещение в новое место. Тогда появляется сила трения скольжения, ее направление противоположно смещению предмета.

Благодаря действию трения невозможно перемещаться вечно. Движение закончится через определенное время. Если же внешняя сила вновь превысит значение трения покоя, то перемещение возобновится.

Виды силы трения

Основные виды силы трения:

-

Покоя. Она сопротивляется внешним факторам, пытающимся сдвинуть тело. При их отсутствии ее значение приравнивают к нулю.

-

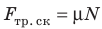

Скольжения. Она находится в прямой зависимости от коэффициента трения и значения силы, с которой поверхность оказывает давление на тело. Ее направление действия всегда перпендикулярно поверхности. Она обычно ниже, чем максимальная сила трения покоя.

-

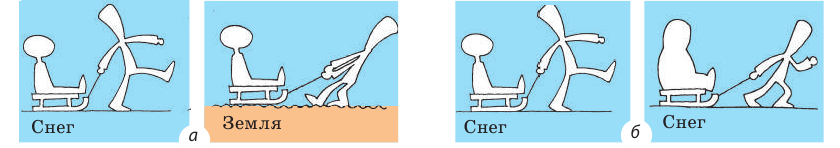

Качения. Она возникает, когда одно тело катится по поверхности другого. Например, при соприкосновении колеса едущего велосипеда с дорогой или при работе подшипникового механизма. Она оказывает гораздо меньшее действие, чем трение скольжения, если остальные условия считать неизменными. Ее открытие стало незаменимым для техники. Колеса и круглые детали, вращающиеся и меняющие положение, являются основой многих механизмов и работы транспортных средств.

-

Верчения. Она появляется, когда один предмет начинает вращаться по поверхности другого.

Само трение может быть нескольких видов:

-

Сухим. Проявляется при соприкосновении твердых поверхностей. На них не наблюдаются другие материалы и слои. Такое в природе и жизни встречается крайне редко.

-

Вязким. Его еще называют жидкостным. Возникает при взаимодействии твердого тела с жидкостью или газом. Они могут течь мимо неподвижного предмета. Или он перемещается в жидкой или газообразной субстанции. Например, лодку тянут на канате по реке. Тело заставляет перемещаться верхний слой жидкости или газа. Словно тянет его за собой. Он в свою очередь действует на другой слой, расположенный ниже. Чем дальше от тела, тем ниже скорость движения слоев. Это происходит из-за уменьшения влияния твердого предмета. Между слоями возникает сила трения, так как тела движутся относительно друг друга. Она приводит к их торможению, а значит и действует на твердое тело, останавливая его. Температура определяет степень вязкости веществ. Например, она снижается при нагревании масла. Это наглядно видно на работе автомобильного мотора. Когда машина долго находилась на холоде, двигатель нужно сначала разогреть, чтобы увеличить скорость его вращения. У газов обратная зависимость. Вязкость растет с увеличением температуры.

-

Смешанным. Оно наблюдается, когда между телами, соприкасающимися поверхностями, есть слой смазки.

Также трение разделяют на внутреннее и внешнее. Последнее возникает при взаимодействии твердых тел. Значит к нему можно отнести сухое трение.

Внутреннее же характеризуется вязкостью. Именно при взаимодействии жидкостей или газа смещение происходит внутри одного тела, когда слои движутся относительно друг друга.

Как найти силу трения

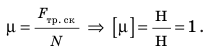

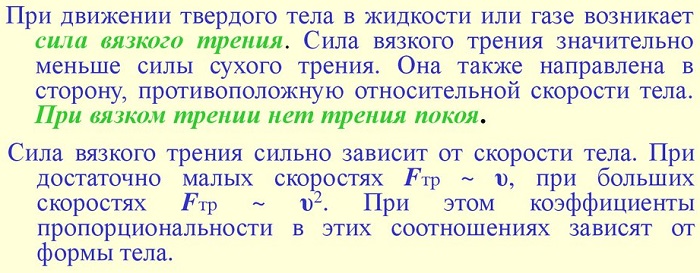

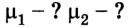

Чтобы найти силу трения, нужно знать коэффициент трения k, зависящий от свойств поверхности. Это постоянная величина, значение которой берется из таблиц.

Также понадобится сила реакции опоры N. Нужная величина определяется произведением двух значений:

Fтр = k * N

Буквой k обозначается коэффициент. Также можно встретить символ µ. Обычно он находится в пределах от 0,1 до 1.

Например, для резины, перемещающейся по сухому асфальту, при движении он колеблется от 0,5 до 0,8. При скольжении металла по дереву – 0,4, железа по чугуну – 0,18.

Сила реакции опоры не отличается от величины силы тяжести, зависящей от веса тела. Поэтому ее значение равно произведению массы тела (m) на ускорение свободного падения (g).

N = m * g

Это постоянная величина, составляющая 9,8 м/с². Это правило действует, когда приходится иметь дело с горизонтальной поверхностью. Сила тяжести и реакция опоры уравновешивают друг друга. Поэтому их считают равными величинами.

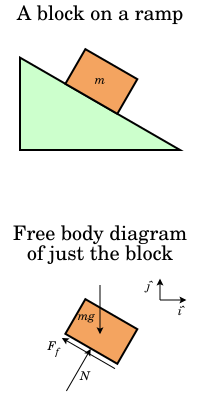

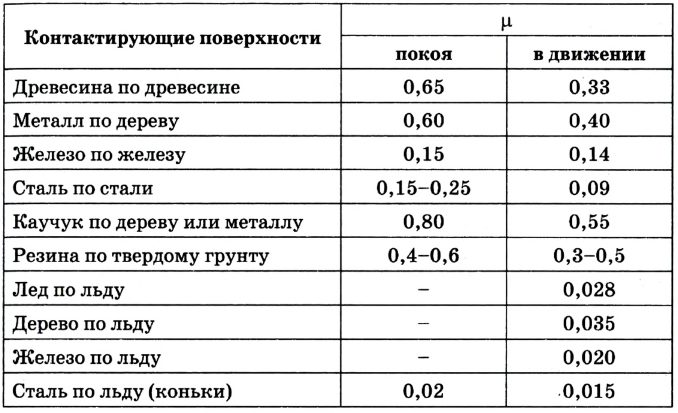

Если же происходит движение по наклонной плоскости, ход рассуждений несколько меняется. На предмет по-прежнему действуют силы тяжести и реакция опоры, но не в одном направлении.

При знании угла наклона плоскости к горизонту, формула трансформируется и приобретает следующий вид:

N = k * m *·g *·cosα

Здесь необходимо руководствоваться тем, что косинус это отношение катета, прилежащего к углу, к гипотенузе треугольника. Это один из тех случаев, доказывающих тесную взаимосвязь физики и тригонометрии.

Пример решения задачи

Задача, на применение полученных знаний, связанных с силой трения, поможет закрепить материал.

Условие задачи. На полу стоит коробка весом 7 кг. Коэффициент трения между ней и полом составляет 0,3. К коробке прикладывают силу, равную 14 Н. Сдвинется ли она с места?

Решение.

Коробка находится на горизонтальной плоскости. Она подвержена действию силы тяжести, которую уравнивает реакция опоры. Они направлены перпендикулярно коробке и полу. Значит, для определения силы реакции опоры, нужно умножить массу коробки на ускорение:

N = m * g;

N = 10 кг * 9,8 м/с² = 98 кг * м/с² = 98 Н;

Fтр = k * N;

Fтр = 0,3·* 98Н = 29,4 Н.

Ответ: полученное значение превышает усилия, приложенные к коробке со стороны, так как 29,4 Н > 14 Н. Значит, она останется на первоначальном месте.

Сила трения присутствует в жизни постоянно. Она мешает предметам сдвинуться с места и противится их длительному скольжению и перемещению. Ее значение зависит от поверхностей, с которыми приходится соприкасаться, их свойств и характеристик.

Площадь соприкосновения не учитывается, зато имеет значение положение тела. Например, сила, возникающая при движении автомобиля по ровной поверхности, отличается от величины при перемещении по горной местности, расположенной под углом к горизонту. А если машине приходится двигаться на мокрой дороге, то значение снова меняется.

Содержание:

Сила трения и коэффициент трения скольжения:

Наблюдение: автомобиль после выключения двигателя через определённое время останавливается. Шайба, движущаяся по льду, также со временем остановится. Останавливается велосипед, если прекратить крутить педали.

Что же является причиной уменьшения скорости движения тел ?

Из ранее изученного вы знаете, что причиной изменения скорости движения тел есть действие одного тела на другое. Значит, в рассматриваемых случаях на каждое движущееся тело действовала сила. Тела остановились, поскольку на них в направлении, противоположном их движению, действовала сила, называемая силой трения

Сила трения возникает между взаимодействующими твёрдыми телами в местах их соприкосновения и препятствует их относительному перемещению.

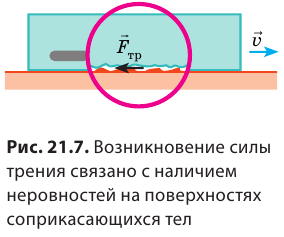

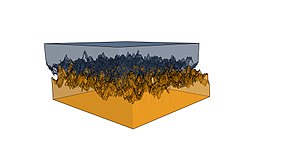

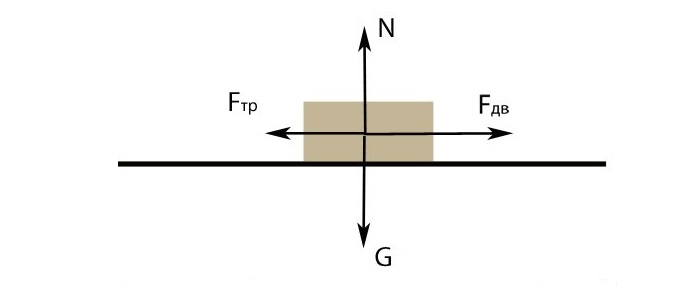

Одной из причин возникновения силы трения является шероховатость соприкасающихся поверхностей тел. Даже гладкие на вид поверхности тел имеют неровности, бугорки и царапины. На рисунке 81 эти неровности изображены в увеличенном виде.

Когда одно тело скользит по поверхности другого, эти неровности зацепляются одна за другую, что создает силу, затрудняющую движение. Вторая причина трения — взаимное притяжение молекул соприкасающихся поверхностей тел. Если поверхности тел очень хорошо отполированы, то их молекулы оказываются так близко друг от друга, что начинает заметно проявляться притяжение между ними. Различают несколько видов трения в зависимости от того, как взаимодействуют трущиеся тела: трение покоя, трение скольжения, трение качения.

Опыт 1. Положим брусок на наклонную доску. Брусок находится в состоянии покоя. Что удерживает его от соскальзывания вниз? Трение покоя обеспечивает сцепление бруска и доски.

Опыт 2. Прижмите свою руку к тетради, лежащей на столе, и передвиньте её. Тетрадь будет двигаться относительно стола, но находиться в покое относительно вашей ладони. С помощью чего вы принудили эту тетрадь двигаться? С помощью трения покоя тетради об руку. Трение покоя перемещает грузы, которые размещаются на подвижной ленте транспортёра, предотвращает развязывание шнурков, удерживает шурупы и гвозди в доске и т. п.

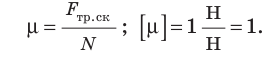

Если тело скользит по другому, то трение, возникающее при этом, называют трением скольжения. Такое трение возникает при движении саней или лыж по снегу, подошв обуви по земле.

Если одно тело катится по другому, то говорят о трении качения. При качении колес вагона, автомобиля, телеги, при перекатывании бочек по земле проявляется трение качения.

А от чего зависит сила трения ?

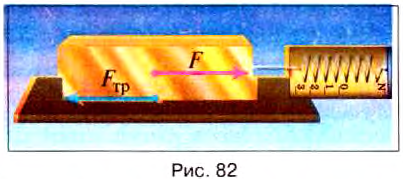

Опыт 3. Прикрепим к бруску динамометр и будем тянуть его, сообщая бруску равномерное движение (рис. 82).

При этом динамометр будет показывать силу, с которой мы тянем брусок, а тем самым и силу трения, возникающую во время движения бруска по поверхности стола. Положим на брусок грузики и повторим опыт. Динамометр зафиксирует большую силу трения.

Чем большая сила прижимает тело к поверхности, тем большая сила трения возникает при этом.

Выполним предыдущий опыт, но тело будем двигать по поверхности стекла, по бетону. Выясним, что сила трения зависит от материала и качества поверхности, по которой движется тело.

Сила трения зависит от материала и качества обработки поверхности, по которой движется тело.

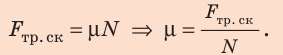

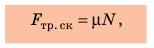

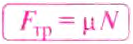

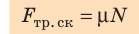

Силу трения скольжения определяют по формуле:

где

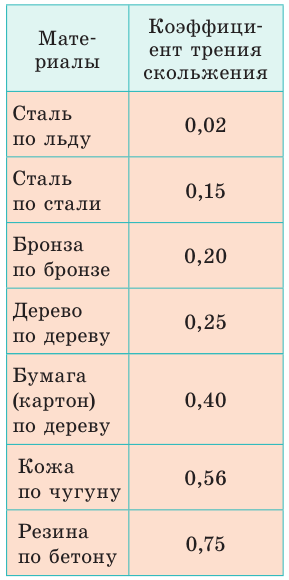

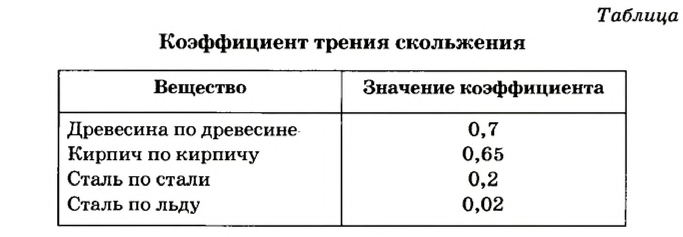

В таблице 5 указаны коэффициенты трения скольжения для некоторых пар материалов.

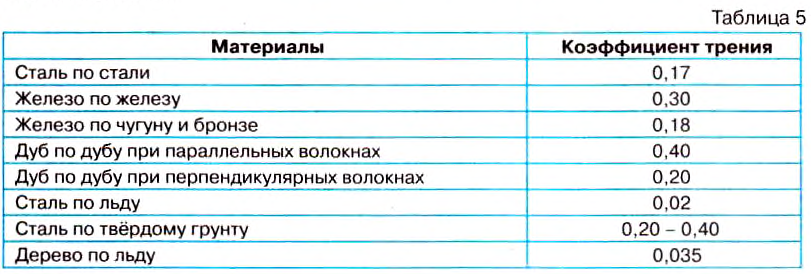

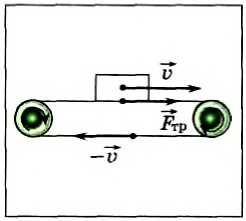

Опыт. Положим деревянный брусок на круглые карандаши (рис. 83).

Потянем брусок динамометром, карандаши за счёт трения между ними, бруском и доской начнут вращаться, а брусок — двигаться. Сила трения качения окажется меньше силы трения скольжения.

При одинаковых нагрузках сила трения качения всегда меньше силы трения скольжения.

Рассматривая швейную иглу, вы сразу заметите, что она отполирована до блеска. Для чего нужна такая полировка? А легко ли шить заржавевшей иглой? Здесь вы непосредственно ощущаете, какую роль играет трение в быту.

В природе и технике трение может быть и полезным, и вредным. Когда оно полезное, его стараются увеличить, а когда вредное — уменьшить.

Из-за трения изнашиваются механизмы и машины, стираются подошвы обуви и шины автомобилей, усложняется перемещение разных грузов. Но представьте, что трение исчезло. Тогда движущийся автомобиль не смог бы остановиться, а неподвижный — сдвинуться с места; пешеходы упали бы на дорогу и не смогли бы подняться; ткани распались бы на нити, так как они удерживаются трением; вы даже не смогли бы перелистать страницы этого учебника.

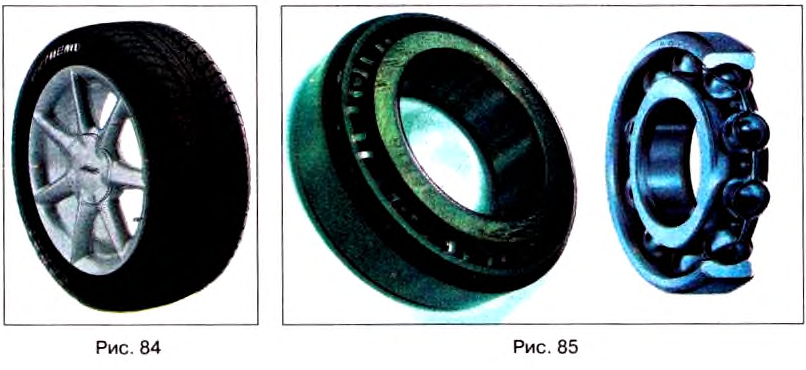

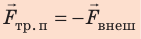

Вы, наверное, неоднократно замечали, что на автомобильных шинах есть рельефные рисунки (так называемые протекторы), которые размещены вдоль и поперёк шины (рис. 84).

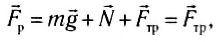

Во всех машинах вследствие трения нагреваются и изнашиваются подвижные части. Чтобы уменьшить трение, соприкасающиеся поверхности делают гладкими и между ними вводят смазочное масло, поскольку трение между поверхностью твердого тела и жидкостью значительно меньше, чем между поверхностями твёрдых тел. Вращающиеся валы машин и станков устанавливают на подшипниках. Подшипники качения бывают шариковыми и роликовыми (рис. 85). Они дают возможность уменьшить силу трения в 20—30 раз по сравнению с подшипниками скольжения.

Известно, что смазка трущихся поверхностей значительно уменьшает трение между ними. Почему же тяжелее удерживать топорище топора сухой рукой, чем влажной? Оказывается, что при смазке дерева мелкие волокна на его поверхности набухают, поэтому трение между рукой и топорищем увеличивается, что и помогает удерживать топор в руках.

Наблюдение. Когда вы стараетесь бежать в воде бассейна, реки или озера, то ощущаете большое сопротивление со стороны воды и не можете передвигаться быстро. Перенося лёгкие большие предметы в ветреную погоду, вы ощущаете такое сопротивление со стороны ветра, что вам очень тяжело идти. Когда в безветренную погоду вы стоите у дороги и мимо вас проезжает большой грузовой автомобиль на большой скорости, то вы обязательно ощутите ветер, сопровождающий движение автомобиля. Сила этого ветра тем больше, чем выше скорость автомобиля.

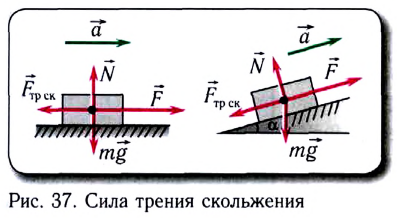

Силы трения, возникающие при движении тел в жидкости или газе, называют силами сопротивления среды.

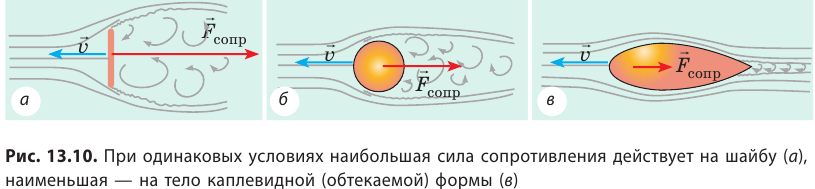

Сила сопротивления зависит от формы тела. Ракетам, самолётам, подводным лодкам, кораблям и автомобилям придают обтекаемую форму, т. е. форму, при которой сила сопротивления минимальна.

Опыт. Возьмём два измерительных цилиндра, наполним один из них водой, а второй — постным или машинным маслом. Бросим одновременно в них одинаковые металлические шарики. В результате опыта увидим, что шарик в воде упадёт на дно быстрее, чем в масле, т. е. сила сопротивления движения шарика в масле больше, чем в воде.

Лодки, корабли не могут развить таких скоростей, какие развивают самолёты, так как сила сопротивления движения в воде намного больше, чем в воздухе.

Сила трения

Как наблюдать силу трения:

Взаимодействие тел, вследствие чего изменяются скорости этих тел, происходит не только при их столкновении. В природе можно наблюдать множество примеров, когда одно тело скользит или катится по поверхности другого. О взаимодействии этих тел можно судить по тому, что скорость этих тел изменяется. Скатившись с горы, камень даже на ровной поверхности со временем остановится. Хоккейная шайба двигается по льду в течение определенного времени, а потом останавливается.

Закрепим наклонно на столе доску, положим на нее шарик и отпустим. Шарик скатится, приобретя определенную скорость, прокатится по столу и, в конце концов, остановится. Если на стол положить стекло, то шарик прокатится на большее расстояние. Таким образом, причиной изменения скорости шарика является его взаимодействие со столом или стеклом.

В рассмотренных примерах скорости камня, шайбы, шарика уменьшались. Значит, на них действовала некоторая сила, направленная против движения. Эта сила возникла в результате взаимодействия тел, касающихся друг друга и осуществляющих взаимное перемещение. Движущийся камень взаимодействует с поверхностью Земли, шайба — с поверхностью льда, шарик — с поверхностью стола или стекла. При движении тела в жидкости или газе тоже возникает сила трения.

Силу, возникающую при относительном перемещении соприкасающихся тел, называют силой трения.

Как измерить силу трения

Опыты показывают, что сила трения может иметь различные значения. Измерить ее можно при помощи динамометра. Положим деревянный брусок на доску, присоединим к нему крючок динамометра и начнем тянуть за него. Стрелка динамометра начнет отклоняться от нулевой отметки, а когда брусок начнет двигаться равномерно, остановится на определенном делении. Это и будет значение силы трения при движении бруска но поверхности доски. Сила трения всегда пропорциональна силе, с которой прижимается одно тело к другому. Эту зависимость можно выразить формулой:

где

Коэффициент трения

Почему возникает сила трения

Природу силы трения можно объяснить, если учесть свойства взаимодействующих тел. Поверхность каждого тела всегда имеет микроскопические неровности. При относительном перемещении двух тел эти неровности мешают взаимному смещению тел, что и проявляется как сила трения (рис. 53). Даже тщательная полировка не поможет преодолеть трение. Исследования показали, что трение даже будет возрастать. Так как в этом случае расстояния между молекулами тел уменьшаются, то можно сделать выводы, что трение связано с взаимодействием молекул.

Виды трения

Различают три вида трения: трение скольжения, трение качения и трение покоя.

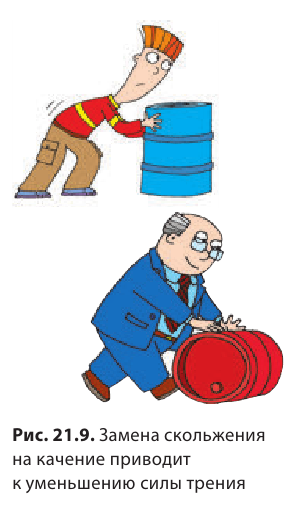

Трение скольжения возникает тогда, когда одно тело скользит по поверхности другого. Трение качения возникает при качении одного тела шарообразной или цилиндрической формы по поверхности другого тела. Сила трения скольжения всегда больше силы трения качения. Этот факт хорошо известен грузчикам, которые вместо того, чтобы тянуть бочку, катят ее.

Как учитывают силы трения

Трение везде встречается в природе и может как содействовать, так и мешать деятельности человека. В каждом случае люди научились управлять этим явлением, создавая условия, когда силы трения уменьшаются или, наоборот, увеличиваются. Так, для увеличения безопасности движения автомобиля его шины изготавливают с шероховатой поверхностью, которая дополнительно имеет узорчатые углубления (рис. 54), что способствует увеличению силы трения колес об асфальт.

Во всех транспортных средствах есть тормоза, предназначенные для торможения, то есть для ускорения остановки автомобиля или поезда. Тормоза оснащены тормозными колодками, которые покрыты специальным материалом, коэффициент трения которого по стали велик (рис. 55).

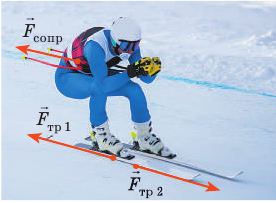

В то же время, бывают случаи, когда силу трения нужно существенно уменьшить. Тогда трущиеся поверхности разделяют жидкостью — минеральной смазкой или даже водой, как это происходит в стиральных машинах. Слой жидкости разделяет трущиеся поверхности, и они не взаимодействуют друг с другом (рис. 56).

На различных деталях современных машин и механизмов устанавливают шариковые или роликовые подшипники качения (рис. 57). Как правило, это две стальные обоймы, между которыми находятся металлические шарики или цилиндрики — ролики. Такие подшипники существенно уменьшают трение, так как в них действуют только силы трения качения, которые при равных условиях значительно меньше сил трения скольжения. Заполненные смазкой шариковые и роликовые подшипники обеспечивают быстрое, бесшумное и экономное вращение деталей.

Что такое сила трения

Трение, при котором твердые тела взаимодействуют своими поверхностями, называют внешним. Внутренним считают трение, возникающее во время движения жидкостей и газов.

Сила трения — это сила, возникающая в плоскости касания поверхностей двух тел, прижатых одно к другому, и препятствующая их относительному перемещению.

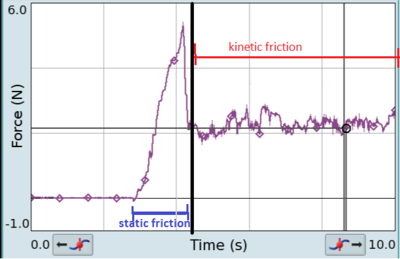

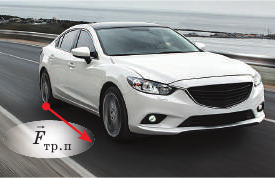

Сила трения возникает не только во время относительного движения тел, но и в случае их относительного покоя (сила трения покоя).

Сила трения покоя равна внешней силе, которая пытается сдвинуть тело с места. Она направлена противоположно направлению приложенной силы.

В зависимости от вида перемещения одного тела по другому различают трение скольжения и трение качения.

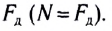

Сила трения скольжения прямо пропорциональна силе реакции опоры:

где

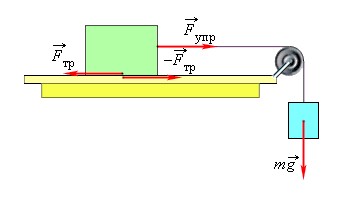

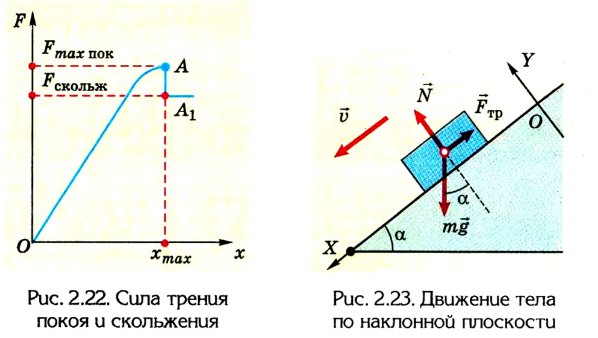

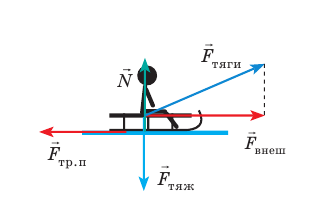

Если приложенная к телу сила

Сила трения покоя во время взаимодействия изменяется от нуля до максимального значения (точка А). Когда сила F достигает этого значения, трение покоя переходит в

трение скольжения.

Тело начинает скользить. При этом сила трения скольжения несколько меньше силы трения покоя. Дальше сила трения скольжения уже остается постоянной.

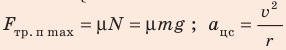

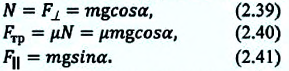

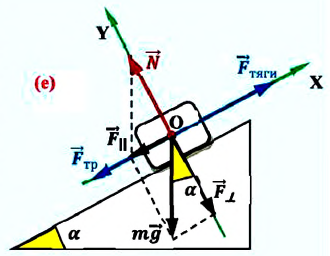

При движении тела по наклонной плоскости (рис. 2.23) на силу реакции опоры влияет угол наклона этой плоскости к горизонту а: N = mg cos а.

Значения коэффициента трения скольжения в зависимости от характера трущихся поверхностей для сухого трения (без масел) приведены в таблице 1.

Сила трения качения имеет более сложную зависимость, также обусловленную деформацией соприкасающихся поверхностей.

Таблица 1

Коэффициент трения скольжения

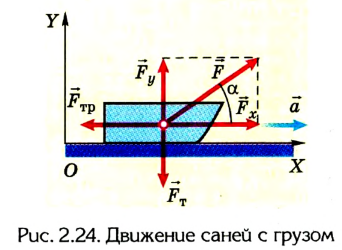

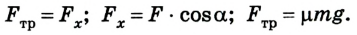

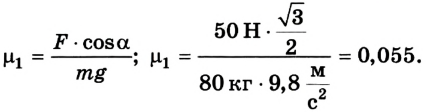

Пример №1

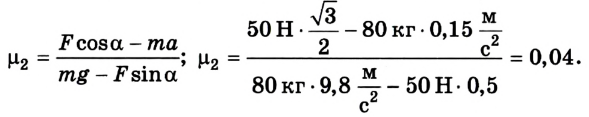

По горизонтальной дороге тянут за веревку (под углом 30°) сани с грузом, общая масса которых 80 кг. Сила натяжения 50 Н. Определить коэффициент трения скольжения, если сани движутся с ускорением 0,15

Дано:

m = 80 кг,

F = 50 Н,

а = 0,15

Решение

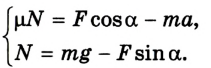

На сани действуют силы: тяжести

реакции дороги

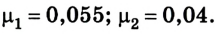

Сначала рассмотрим случай, когда сани движутся равномерно. Силу трения

Тогда

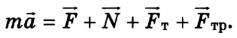

Для равноускоренного движения запишем второй закон механики Ньютона для саней в векторной форме:

В проекциях на оси координат данное уравнение будет иметь такой вид:

на ось ОХ: та = Fcos

на ось ОУ: 0 — Fsin

Поскольку

Разделив первое уравнение на второе, получим

Ответ:

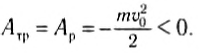

Работа силы трения

Движение тел на Земле происходит под действием различных сил, но практически всегда присутствуют силы трения, силы сопротивления среды, в которой движется тело. Поэтому рассмотрим на частных примерах работу этих сил.

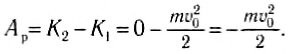

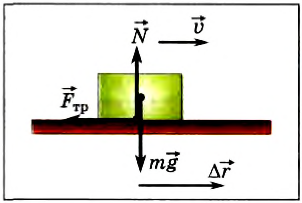

Проведем следующий опыт. Толкнем брусок, лежащий на столе. Он придет в движение, а затем остановится. В процессе движения на него действуют сила тяжести

поскольку сила тяжести компенсируется силой нормальной реакции стола. По теореме об изменении кинетической энергии тела работа равнодействующей силы равна изменению кинетической энергии тела. Если в начальный момент времени скорость тела была равна

C другой стороны, эта работа есть работа сил трения, т. е.:

Таким образом, работа силы трения скольжения отрицательна.

При скольжении одного тела по поверхности другого происходит, во-первых, деформация шероховатостей обеих поверхностей и, во-вторых, трущиеся тела нагреваются, т. е. повышается их температура. В этом можно легко убедиться, если потереть деревянный брусок о доску. Из курса физики 8-го класса известно, что температура тел определяется средней кинетической энергией движения молекул, из которых они состоят. Повышение температуры трущихся тел означает увеличение средней кинетической энергии хаотического движения молекул этих тел, а следовательно, их внутренней энергии. Таким образом, можно сказать, что начальная кинетическая энергия бруска превратилась во внутреннюю энергию трущихся тел.

Рис. 141

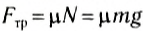

Работу силы трения скольжения мы можем легко подсчитать и иначе. По закону сухого трения

так как

Из формулы (3) следует, что работа силы трения зависит от модуля перемещения тела. Если тело вернется в исходную точку, то работа силы трения не будет равна нулю. Таким образом, сила трения не является потенциальной силой. Для нее нельзя ввести понятие потенциальной энергии. Такие силы, работа которых зависит от формы траектории движения тела, называются непотенциальными или диссипативными (лат. dissipative — рассеяние).

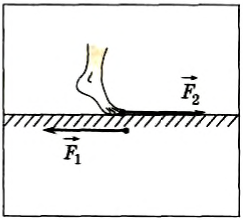

Очевидно, что сила сопротивления среды (газа или жидкости) при движении некоторого тела, направленная в сторону, противоположную скорости тела, также совершает работу. Однако не надо думать, что работа сил трения всегда отрицательна. Ведь именно благодаря силе трения покоя человек и различные машины движутся по земле. Действительно, при ходьбе человек действует на поверхность Земли с силой

Рис. 142

Если тело лежит на движущейся ленте транспортера, то именно благодаря силе трения оно приобретает скорость (рис. 143).

Рис. 143

Точно так же под действием силы трения покоя движутся и автомобили. На ведущие колеса автомобиля от мотора передается вращательный момент.

Колеса пытаются провернуться, следовательно, в горизонтальном направлении они действуют на поверхность земли с силой

Рис. 144

Главные выводы

- Силы трения не являются потенциальными силами.

- Работа сил трения зависит от формы траектории движения тела. Работа сил трения по замкнутой траектории не равна нулю.

- Работа сил трения обычно отрицательна. Она идет на увеличение внутренней энергии взаимодействующих тел.

Сила трения и движение под действием силы трения

Сила трения возникает между соприкасающимися друг с другом телами и направлена вдоль поверхности соприкосновения против их относительного движения. Причиной возникновения силы трения являются неровности соприкасающихся поверхностей и «силы сцепления» (силы притяжения) между молекулами этих поверхностей. Возникновение таких сил между молекулами определяет электромагнитную природу силы трения.

Существуют три вида силы трения:

- Сила трения скольжения — это сила трения, возникающая при скольжении одного тела по поверхности другого тела.

- Сила трения качения — это сила трения, возникающая, когда одно тело катится по поверхности другого.

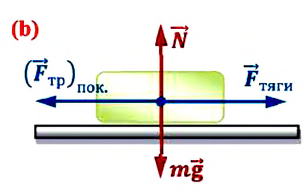

- Сила трения покоя — это сила трения, возникающая между телами, находящимися в состоянии покоя друг относительно друга. Численно сила трения покоя равна силе (b) тяги, направленной параллельно поверхности соприкосновения неподвижных тел, и направлена против нее (b).

При определенном значении силы тяги тело начинает двигаться и скользить по поверхности другого тела — возникает сила трения скольжения.

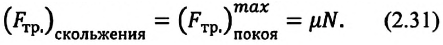

Численное значение силы трения скольжения прямо пропорционально силе реакции опоры (силе давления) и равно максимальному значению силы трения покоя:

Где

В зависимости от свойств соприкасающихся поверхностей силу трения называют сухой силой трения и силой сопротивления.

- Сухое трение — это трение, возникающее между поверхностями соприкасающихся твердых тел.

- Сила сопротивления — это сила, возникающая во время движения твердого тела в жидкости или газе.

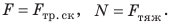

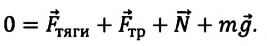

Движение под действием силы трения

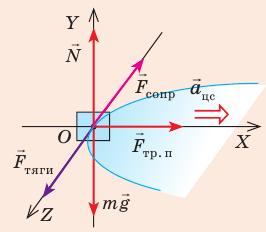

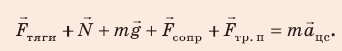

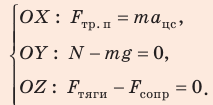

Исследуем разные движения тела массой

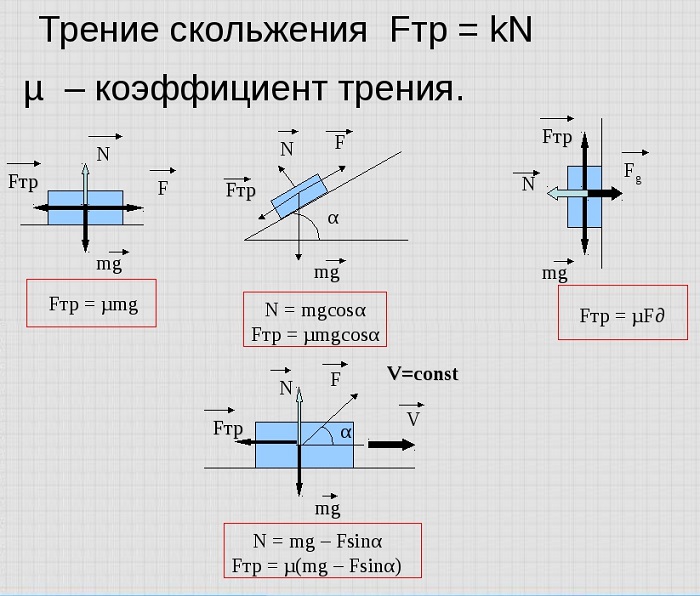

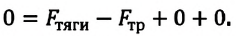

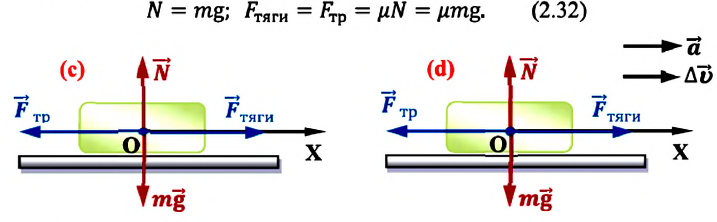

Тело движется прямолинейно равномерно по горизонтальной поверхности

Все силы, действующие на тело, показаны на схеме (с). При равномерном движении тела его ускорение

Выбрав координатную ось вдоль направления силы тяги (в направлении движения) и получив проекции всех сил на эту ось, можно написать уравнение движения (см: с):

Здесь было принято во внимание, что проекции силы реакции и силы тяжести на ось

Таким образом, модули сил, действующих на тело, движущееся равномерно прямолинейно по горизонтальной поверхности, попарно равны и компенсируют взаимное действие друг друга:

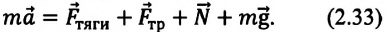

Тело движется прямолинейно равнопеременно по горизонтальной поверхности (d).

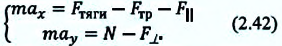

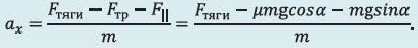

В этом случае уравнение движении тела в общем виде:

Спроецировав силы на горизонтальную координатную ось, запишем уравнение движения в скалярном виде:

Любая величина, входящая в последнее выражение, с легкостью определяется.

На движущееся тело действует только сила трения

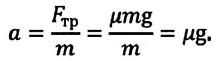

Так как сила трения всегда направлена против направления движения, то ускорение, сообщаемое этой силой, направлено против скорости движения тела. Поэтому, если на движущееся тело действует только сила трения, то оно тормозится. В этом случае уравнение движения записывается в виде:

Для ускорения тела имеем

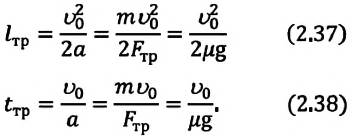

Отсюда можно определить тормозной путь и время торможения тела, движущегося по горизонтальной дороге:

Тело движется по наклонной плоскости

Наклонная носкость — это плоскость, образующая определенный угол

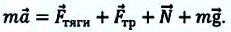

Уравнение движения тела по наклонной плоскости в общем виде записывается так:

Для решения уравнения выбираем прямоугольную систему координат XOY, находим проекции сил на ее оси и получаем систему двух уравнений:

Ввиду отсутствия движения вдоль оси OY

Определение силы трения

При движении одного тела по поверхности другого (при попытке к такому движению) возникает сила трения, направленная против движения (против возможного движения).

Опыт показывает, что в земных условиях всякое неподдерживаемое механическое движение с течением времени прекращается под действием сил трения (сопротивления).

Трением называется взаимодействие между различными соприкасающимися телами, препятствующее их относительному перемещению.

Силы трения имеют электромагнитное происхождение, поскольку их появление обусловлено взаимодействием «пограничных» атомов, расположенных на поверхностях соприкасающихся тел. Вследствие этого, силы трения, как правило, действуют параллельно трущимся поверхностям.

Различают силы сухого трения (покоя, скольжения, качения) и вязкого трения (силы сопротивления, возникающие при движении в жидкости или газе).

Отметим, что действие сил трения приводит к переходу механической энергии во внутреннюю энергию тела.

Трение покоя

Силы трения покоя возникают между неподвижными телами при попытке сдвинуть одно из них (рис. 36).

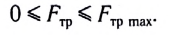

Сила трения покоя равна по модулю и направлена противоположно силе, приложенной к телу, параллельно поверхности соприкасающихся тел. В зависимости от приложенной силы модуль силы трения

Экспериментально установлено, что

где N — модуль силы нормальной реакции опоры в месте соприкосновения тел,

Согласно третьему закону Ньютона модуль силы нормальной реакции опоры N равен модулю силы нормального давления

Трение скольжения. Сила трения скольжения

Она направлена противоположно скорости относительного движения поверхностей. Модуль силы трения скольжения

где

Этот закон был установлен экспериментально и называется законом Кулона — Амонтона.

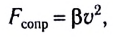

Точные измерения показывают, что коэффициент трения скольжения зависит также и от модуля скорости относительного движения соприкасающихся тел (при малых скоростях в большинстве случаев

Как следует из формулы для модуля силы трения скольжения, коэффициент трения

Поверхность называется гладкой, если силы трения равны нулю при любом характере движения.

Вязкое трение

Эксперименты показывают, что при движении в жидкости или газе (сплошной среде) на тело действует сила вязкого трения

При небольших скоростях движения (малых по сравнению со скоростью звука в воздухе) можно считать, что модуль силы вязкого трения прямо пропорционален скорости движения тела:

а при больших скоростях — квадрату скорости:

где

- Заказать решение задач по физике

Откуда появилась сила трения

Почему профили самолетов и подводных лодок напоминают контуры тела дельфина? Почему зимой автомобили «переобувают» в шипованную резину? Почему трудно двигаться в гололед? Как «падает» парашютист? Как уменьшить силу трения? А может, ее не стоит уменьшать, а наоборот, нужно увеличивать? Что будет, если трение исчезнет вообще?

При любом движении тело обязательно контактирует с микро- или макротелами вокруг (поверхностью другого тела, частицами жидкости или газа, внутри которых тело движется, и т. д.). При таком контакте возникают силы, замедляющие движение тела, — силы трения.

Сила трения

Сила трения всегда направлена вдоль поверхности соприкасающихся тел и противоположно направлению скорости их относительного движения (рис. 13.1).

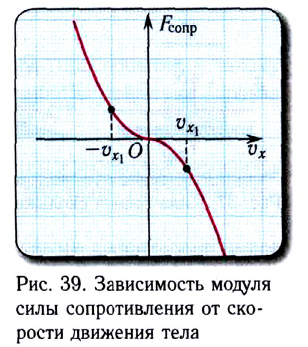

Рис. 13.1. Относительно поверхности снега и относительно воздуха лыжник движется вправо, поэтому сила трения

Трение между поверхностью твердого тела и окружающей жидкой или газообразной средой называют сопротивлением среды или жидким (вязким) трением. Трение между поверхностями двух соприкасающихся твердых тел называют сухим трением.

Почему возникает сила сухого трения

Если рассмотреть поверхность любого тела в лупу, можно увидеть множество мелких неровностей. Когда одно тело скользит или пытается скользить по поверхности другого, неровности цепляются друг за друга и деформируются. Возникают силы упругости, направленные в сторону, противоположную деформации (рис. 13.2).

Рис. 13.2. Один из механизмов возникновения сухого трения связан с наличием неровностей на поверхностях соприкасающихся тел

Это одна из причин возникновения силы сухого трения. Есть и другие причины. Так, в некоторых местах выступы тел плотно прижаты друг к другу — расстояние между ними настолько мало, что действуют силы межмолекулярного притяжения, в результате чего выступы оказываются как бы «склеенными». Понятно, что такое «склеивание» происходит в ходе всего движения и препятствует ему.

И сила упругости, и сила межмолекулярного притяжения имеют электромагнитное происхождение, поэтому природа силы сухого трения — электромагнитная.

Какие существуют виды сухого трения

Различают три вида сухого трения: трение покоя, трение скольжения, трение качения. Если вы попробуете, прикладывая небольшую силу, сдвинуть с места санки с тяжелым грузом, они не сдвинутся, поскольку возникнет сила трения покоя, которая уравновесит прилагаемую внешнюю силу.

Сила трения покоя

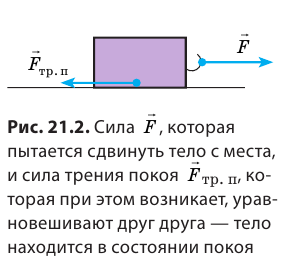

Рис. 13.4. Внешние силы пытаются сдвинуть тело. Сила трения покоя, возникающая при этом, уравновешивает внешние силы, и тело находится в состоянии покоя

Сила трения покоя всегда равна по модулю и противоположна по направлению равнодействующей внешних сил

Чем большая сила будет приложена, тем больше будет сила трения покоя. Наконец при определенном значении равнодействующей внешних сил (а следовательно, и силы трения покоя) тело сдвинется с места. То есть сила трения покоя имеет некоторое максимальное значение.

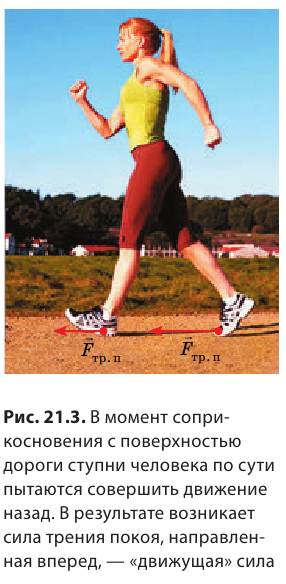

Чаще всего действие силы трения покоя «полезно»: благодаря ей вещи не выскальзывают из рук, грифель карандаша оставляет след на бумаге; эта сила позволяет выполнять повороты, удерживает корни растений в почве. Благодаря силе трения покоя передвигаются люди, животные, транспорт (рис. 13.5).

Рис. 13.5. Шины автомобиля в момент соприкосновения с поверхностью дороги по сути пытаются осуществить движение назад. В результате возникает сила трения покоя, направленная вперед, — движущая сила

В технике, на транспорте, в быту часто принимают меры для увеличения максимальной силы трения покоя: на ступеньки и обувь наклеивают противоскользящие накладки, автомобили «переобувают» в зимние шины и т. д.

После того как равнодействующая внешних сил становится равной максимальной силе трения покоя, тело начинает скольжение, — и тогда говорят о силе трения скольжения.

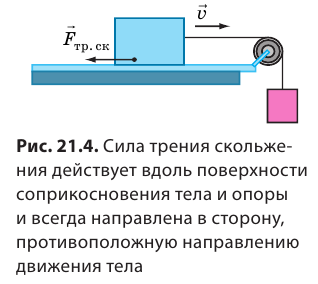

Сила трения скольжения

Сила трения скольжения действует вдоль поверхности соприкосновения тел, и она немного меньше максимальной силы трения покоя (рис. 13.6).

Рис. 13.6. Когда сила трения покоя достигает максимального значения, тело трогается с места (начинает скольжение)

Именно поэтому тела сдвигаются с места рывком и сдвинуть их труднее, чем затем перемещать. Это особенно заметно, когда тела массивные. Ваш жизненный опыт показывает, что сила трения скольжения зависит от свойств соприкасающихся поверхностей и увеличивается с увеличением силы нормальной реакции опоры (рис. 13.7). Закон, отражающий зависимость

Сила трения скольжения не зависит от площади соприкосновения тел и прямо пропорциональна силе N нормальной реакции опоры:

Здесь

Рис. 13.7. Сила трения скольжения зависит от качества и рода поверхностей (а) и увеличивается с увеличением силы нормальной реакции опоры (б)

Значения коэффициентов трения скольжения устанавливают исключительно экспериментально. Обычно таблицы коэффициентов трения скольжения содержат ориентировочные средние значения для пар материалов (см. таблицу).

| Материалы | Коэффициент трения скольжения |

| Сталь по льду | 0,02 |

| Сталь по стали | м |

| Бронза по бронзе | 0,20 |

| Дерево по дереву | 0,25 |

| Бумага (картон) по дереву | 0,40 |

| Резина по бетону | 0,75 |

Силу трения скольжения можно уменьшить, смазав соприкасающиеся поверхности. Твердая смазка изменяет качество поверхности; жидкая смазка отдаляет соприкасающиеся поверхности друг от друга — сухое трение заменяется значительно более слабым жидким трением.

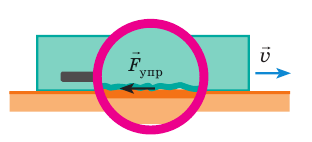

Трение существенно уменьшится, если между соприкасающимися поверхностями расположить твердые катки, то есть скольжение заменить качением. Опыты показывают, что при одинаковых условиях сила трения качения в десятки раз меньше, чем сила трения скольжения.

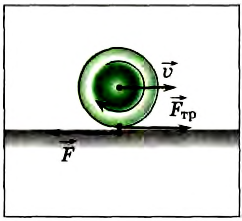

Одна из причин возникновения силы трения качения заключается в том, что поверхность, по которой движется шарообразное тело (цилиндр, колесо, шар), деформируется, поэтому тело все время словно закатывается на небольшую наклонную плоскость (рис. 13.8).

Чем больше деформация поверхности, тем больше угол наклона плоскости и тем больше сила трения качения. Именно поэтому сила трения качения:

- уменьшается с увеличением твердости поверхности, по которой катится тело, и твердости материала, из которого изготовлено тело;

- увеличивается с увеличением давления тела на поверхность;

- уменьшается с увеличением радиуса тела.

Сила сопротивления среды

Сила сопротивления среды (сила вязкого трения)

Рассмотрим причины возникновения силы сопротивления среды.

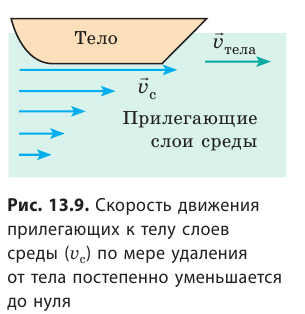

- Ламинарное обтекание. Если твердое тело движется внутри жидкости или газа, то прилегающие слои среды движутся вместе с телом (рис. 13.9). Чем больше вязкость среды, тем больше ее слоев вовлекаются в движение.

- Лобовое сопротивление. Частицы среды сталкиваются с телом и замедляют его движение.

- Вихревое обтекание. Если тело движется с большой скоростью, то ламинарное обтекание переходит в вихревое: непосредственно за телом образуется зона пониженного давления, и тело как бы втягивается в эту зону, замедляя свое движение.

Сила сопротивления среды существенно зависит от формы тела (рис. 13.10).

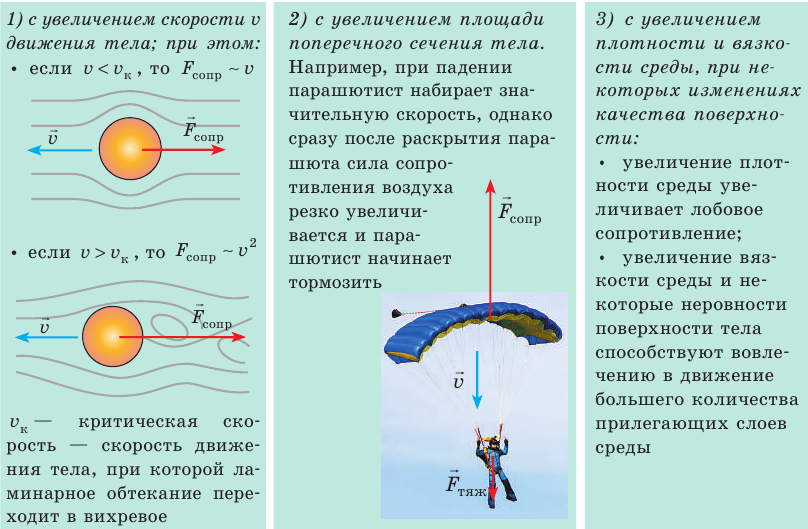

Сила сопротивления среды увеличивается:

Обратите внимание! Не существует силы жидкого трения покоя. То есть если тело, расположенное в жидкой или газообразной среде, находится в состоянии покоя относительно среды, то сила сопротивления среды на него не действует.

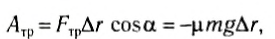

Пример №2

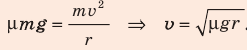

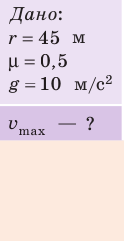

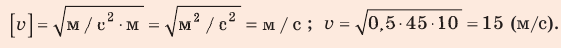

На горизонтальной дороге автомобиль выполняет поворот радиусом 45 м. Какую наибольшую скорость может иметь автомобиль, чтобы «вписаться» в поворот, если коэффициент трения скольжения шин об асфальт

Анализ физической проблемы. Автомобиль «не впишется» в поворот, если

Выполним пояснительный рисунок, указав силы, действующие на автомобиль, и направление ускорения его движения. Систему координат свяжем с телом на поверхности Земли.

Решение:

Запишем второй закон Ньютона:

Спроецируем уравнения на оси координат:

Поскольку

Ответ:

Выводы:

- Сила трения — это сила, возникающая при движении или попытке движения одного тела по поверхности другого, а также при движении тела внутри жидкой или газообразной среды. Сила трения всегда направлена вдоль поверхностей соприкасающихся тел и противоположно скорости их относительного движения.

- Различают силы трения покоя, трения скольжения, трения качения и сопротивления среды. Все эти силы, кроме силы трения качения, имеют электромагнитную природу.

- Сила трения покоя равна по модулю и противоположна по направлению равнодействующей внешних сил, действующих на тело:

- Сила трения скольжения прямо пропорциональна силе нормальной реакции опоры:

. Коэффициент трения скольжения µ зависит от материалов соприкасающихся поверхностей и качества их обработки.

- Сила трения качения прямо пропорциональна силе нормальной реакции опоры, намного меньше силы трения скольжения, зависит от радиуса тела, материала и твердости соприкасающихся поверхностей.

- Сила сопротивления среды существенно зависит от формы тела, увеличивается с увеличением скорости движения тела, площади его поперечного сечения, а также с увеличением вязкости и плотности среды.

Вычисление силы трения

Французский физик Гийом Амонтон (1663–1705), размышляя о роли трения, писал: «Всем нам случалось выходить в гололедицу: сколько усилий стоило нам, чтобы удерживаться от падения, сколько смешных движений приходилось нам проделывать, чтобы устоять!.. Представим, что трение исчезло вовсе. Тогда никакие тела, будь они величиной с каменную глыбу или малы, как песчинки, никогда не удержатся одно на другом: все будет скользить и катиться…. Не будь трения, Земля представляла бы собой шар без неровностей, подобный жидкой капле».

Сила трения покоя

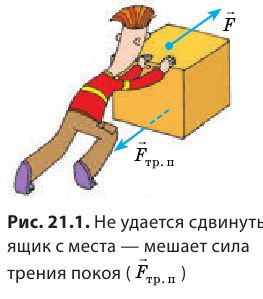

Если вы пытаетесь передвинуть тяжелое тело, например большой ящик, и не можете сдвинуть его с места, это означает, что силу, которую вы прикладываете к ящику, уравновешивает сила трения покоя, возникающая между полом и нижней поверхностью ящика (рис. 21.1).

Сила трения покоя

Сила трения покоя приложена вдоль поверхности, которой тело соприкасается с другим телом, и по значению равна силе

При увеличении силы

В технике, на транспорте, в быту часто принимают меры, чтобы поверхность одного тела не двигалась относительно поверхности другого. Например, для увеличения максимальной силы трения покоя тротуары во время гололедицы посыпают песком, зимой автомобили «переобувают» в зимние шины. Попробуйте привести еще несколько подобных примеров.

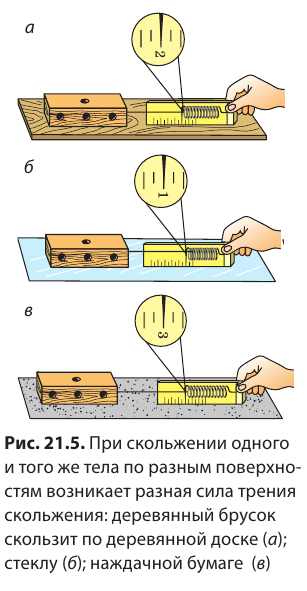

От чего зависит сила трения скольжения

Именно поэтому тела сдвигаются с места рывком и сдвинуть их тяжелее, чем затем двигать. Это особенно заметно, когда тела массивные. Прикрепим к деревянному бруску крючок динамометра и будем равномерно тянуть брусок по горизонтальной поверхности (рис. 21.5). На брусок в направлении его движения действует сила упругости со стороны пружины динамометра, а в противоположном направлении — сила трения скольжения. Брусок движется равномерно, поэтому сила упругости уравновешивает силу трения скольжения. Следовательно, динамометр показывает значение силы трения скольжения. Рассмотрите рис. 21.5 и сделайте вывод о том, как зависит сила трения скольжения от свойств соприкасающихся поверхностей. Обратите внимание: если провести те же опыты, перевернув брусок на меньшую грань, показания динамометра не изменятся.

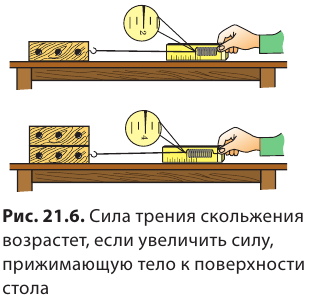

Сила трения скольжения не зависит от площади соприкасающихся поверхностей. Проведем еще один опыт. Положим на брусок дополнительный груз, увеличив таким образом силу нормальной реакции опоры (рис. 21.6). Опыт покажет, что сила трения скольжения возросла.

Сила трения скольжения прямо пропорциональна силе нормальной реакции опоры*:

Этот закон был установлен французским ученым Г. Амонтоном и проверен его соотечественником Ш. Кулоном, поэтому получил название закон Амонтона — Кулона.

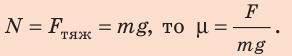

Поскольку и силу трения скольжения, и силу нормальной реакции опоры измеряют в ньютонах, коэффициент трения скольжения — величина, не имеющая размерности:

Причины возникновения и способы уменьшения силы трения

Поверхности твердых тел всегда шероховатые, неровные. При движении или попытке движения неровности цепляются друг за друга и деформируются или даже сминаются. В результате возникает сила, противодействующая движению тела, — сила трения (рис. 21.7).

Сила трения, как и сила упругости, — проявление сил межмолекулярного взаимодействия. Казалось бы, для уменьшения силы трения нужно тщательно отполировать поверхности и таким образом свести неровности к минимуму. Однако в таком случае поверхности будут настолько плотно прилегать друг к другу, что значительное количество молекул окажется на расстоянии, на котором становится существенным межмолекулярное притяжение. В результате сила трения возрастет*. Силу трения скольжения можно уменьшить, смазав соприкасающиеся поверхности. Смазка (как правило, жидкая), попав между соприкасающимися поверхностями, отдалит их друг от друга. То есть будут скользить не поверхности тел, а слои смазки, — трение скольжения (так называемое сухое трение) сменится вязким (жидким) трением, при котором сила трения значительно меньше.

Исследование трения и обоснование причин его возникновения достаточно сложны и вы ходят за рамки школьного курса физики.

Сила трения качения

Давний опыт человечества показывает, что, например, каменную глыбу легче перекатить на бревнах, чем просто тащить по земле. Если одно тело катится вдоль поверхности другого, то мы имеем дело с трением качения. Сила трения качения обычно намного меньше, чем сила трения скольжения (рис. 21.8, 21.9).

Поэтому для уменьшения силы трения люди издавна используют колесо, а в различных механизмах — подшипники (рис. 21.10).

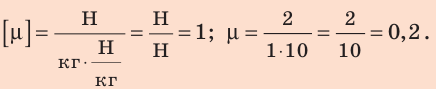

Пример №3

Чтобы равномерно двигать по столу книгу массой 1 кг, нужно приложить горизонтальную силу 2 Н. Чему равен коэффициент трения скольжения между книгой и столом? Анализ физической проблемы. Выполним пояснительный рисунок, на котором изобразим все силы, действующие на книгу:

Дано:

Найти:

Решение:

По формуле для определения силы трения скольжения имеем:

Поскольку

Проверим единицу, найдем значение искомой величины:

Анализ результатов: коэффициент трения 0,2 соответствует паре «дерево по дереву»; результат правдоподобен. Ответ: µ=0,2.

Итоги:

Сила трения покоя

Сила трения скольжения

- Вес тела в физике

- Закон всемирного тяготения

- Свободное падение тела

- Равнодействующая сила и движение тела под действием нескольких сил

- Сила тяжести в физике

- Сила упругости в физике и закон Гука

- Деформация в физике

- Плотность вещества в физике

Что такое сила трения

Тела взаимодействуют друг с другом по-разному. Один из видов взаимодействия — трение. Прежде чем разбираться с тонкостями сухого и вязкого трения, ответим на два вопроса. Что такое сила трения, и когда она возникает?

Сила трения — сила, возникающая при соприкосновении тел и препятствующая их относительному движению.

Трение возникает вследствие взаимодействия между атомами и молекулами тел, когда они соприкасаются друг с другом.

Природа силы трения — электромагнитная.

Как и для любого другого взаимодействия, для трения справедлив третий закон Ньютона. Если на одно из двух взаимодействующих тел действует сила трения, то такая же по модулю сила действует на другое тело в противоположном направлении.

Сила трения покоя и сила трения скольжения

Различают сухое и вязкое трение, силу трения покоя, силу трения скольжения, силу трения качения.

Сухое трение — это трение, которое возникает между твердыми телами при отсутствии между ними жидкой или газообразной прослойки. Силы трения направлена по касательной к соприкасающимся поверхностям.

Представим, что на тело, например, брусок, лежащий на столе, действует некоторая внешняя сила. Эта сила стремится сдвинуть брусок с места. Пока тела покоятся, на брусок действуют сила трения покоя и, собственно, внешняя сила. Сила трения покоя равна внешней силе и уравновешивает ее.

Когда внешняя сила превышает некоторое предельное значение Fтр. max, брусок сдвигается с места. На него так же действует сила трения, но это уже не сила трения покоя, а сила трения скольжения. Сила трения скольжения направлена в сторону, противоположную движению, и зависит от скорости движения тела.

При решении физических задач силу трения скольжения часто принимают равной максимальной силе трения покоя, а зависимостью от силы трения от относительной скорости движения тел пренебрегают.

На рисунке выше показаны реальная и идеализированная характеристики сухого трения. Как видим, на самом деле сила трения скольжения меняется в зависимости от скорости, однако изменения не столь велики, чтобы ими нельзя было пренебречь.

Сила трения пропорциональна силе нормальной реакции опоры.

Fтр=Fтр. max=μN.

Что такое коэффициент трения скольжения?

μ — коэффициент пропорциональности, который называется коэффициентом трения скольжения. Он зависит от материалов соприкосающихся тел и их свойств. Коэффициент трения скольжения — безразмерная величина, не превышающая единицы.

Силы трения качения возникают при качении тел. Обычно при решении задач ими пренебрегают.

Вязкое трение в жидкостях и газах

Вязкое трение возникает при движении тел в жидкостях и газах. Сила вязкого трения также направлена в сторону, противоположную движению тела, но по величине гораздо меньше силы трения скольжения. Трение покоя отсутствует при вязком трении.

Расчет силы вязкого трения более сложен, нежели расчет силы трения скольжения. При малых скоростях движения тела в жидкоси сила вязкого трения пропорциональна скорости тела, а при больших скоростях — квадрату скорости. Коэффициенты пропорциональности при этом зависят от формы тел, также необходимо учитывать свойства самой среды, в которой происходит движение.

Например, силы вязкого трения в воде и масле будут отличаться, так как эти жидкости имеют различные вязкости.

Figure 1: Simulated blocks with fractal rough surfaces, exhibiting static frictional interactions[1]

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other.[2] There are several types of friction:

- Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of two solid surfaces in contact. Dry friction is subdivided into static friction («stiction») between non-moving surfaces, and kinetic friction between moving surfaces. With the exception of atomic or molecular friction, dry friction generally arises from the interaction of surface features, known as asperities (see Figure 1).

- Fluid friction describes the friction between layers of a viscous fluid that are moving relative to each other.[3][4]

- Lubricated friction is a case of fluid friction where a lubricant fluid separates two solid surfaces.[5][6][7]

- Skin friction is a component of drag, the force resisting the motion of a fluid across the surface of a body.

- Internal friction is the force resisting motion between the elements making up a solid material while it undergoes deformation.[4]

When surfaces in contact move relative to each other, the friction between the two surfaces converts kinetic energy into thermal energy (that is, it converts work to heat). This property can have dramatic consequences, as illustrated by the use of friction created by rubbing pieces of wood together to start a fire. Kinetic energy is converted to thermal energy whenever motion with friction occurs, for example when a viscous fluid is stirred. Another important consequence of many types of friction can be wear, which may lead to performance degradation or damage to components. Friction is a component of the science of tribology.

Friction is desirable and important in supplying traction to facilitate motion on land. Most land vehicles rely on friction for acceleration, deceleration and changing direction. Sudden reductions in traction can cause loss of control and accidents.

Friction is not itself a fundamental force. Dry friction arises from a combination of inter-surface adhesion, surface roughness, surface deformation, and surface contamination. The complexity of these interactions makes the calculation of friction from first principles impractical and necessitates the use of empirical methods for analysis and the development of theory.

Friction is a non-conservative force – work done against friction is path dependent. In the presence of friction, some kinetic energy is always transformed to thermal energy, so mechanical energy is not conserved.

History

The Greeks, including Aristotle, Vitruvius, and Pliny the Elder, were interested in the cause and mitigation of friction.[8] They were aware of differences between static and kinetic friction with Themistius stating in 350 A.D. that «it is easier to further the motion of a moving body than to move a body at rest».[8][9][10][11]

The classic laws of sliding friction were discovered by Leonardo da Vinci in 1493, a pioneer in tribology, but the laws documented in his notebooks were not published and remained unknown.[12][13][14][15][16][17] These laws were rediscovered by Guillaume Amontons in 1699[18] and became known as Amonton’s three laws of dry friction. Amontons presented the nature of friction in terms of surface irregularities and the force required to raise the weight pressing the surfaces together. This view was further elaborated by Bernard Forest de Bélidor[19] and Leonhard Euler (1750), who derived the angle of repose of a weight on an inclined plane and first distinguished between static and kinetic friction.[20]

John Theophilus Desaguliers (1734) first recognized the role of adhesion in friction.[21] Microscopic forces cause surfaces to stick together; he proposed that friction was the force necessary to tear the adhering surfaces apart.

The understanding of friction was further developed by Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1785).[18] Coulomb investigated the influence of four main factors on friction: the nature of the materials in contact and their surface coatings; the extent of the surface area; the normal pressure (or load); and the length of time that the surfaces remained in contact (time of repose).[12] Coulomb further considered the influence of sliding velocity, temperature and humidity, in order to decide between the different explanations on the nature of friction that had been proposed. The distinction between static and dynamic friction is made in Coulomb’s friction law (see below), although this distinction was already drawn by Johann Andreas von Segner in 1758.[12]

The effect of the time of repose was explained by Pieter van Musschenbroek (1762) by considering the surfaces of fibrous materials, with fibers meshing together, which takes a finite time in which the friction increases.

John Leslie (1766–1832) noted a weakness in the views of Amontons and Coulomb: If friction arises from a weight being drawn up the inclined plane of successive asperities, why then isn’t it balanced through descending the opposite slope? Leslie was equally skeptical about the role of adhesion proposed by Desaguliers, which should on the whole have the same tendency to accelerate as to retard the motion.[12] In Leslie’s view, friction should be seen as a time-dependent process of flattening, pressing down asperities, which creates new obstacles in what were cavities before.

Arthur Jules Morin (1833) developed the concept of sliding versus rolling friction. Osborne Reynolds (1866) derived the equation of viscous flow. This completed the classic empirical model of friction (static, kinetic, and fluid) commonly used today in engineering.[13] In 1877, Fleeming Jenkin and J. A. Ewing investigated the continuity between static and kinetic friction.[22]

The focus of research during the 20th century has been to understand the physical mechanisms behind friction. Frank Philip Bowden and David Tabor (1950) showed that, at a microscopic level, the actual area of contact between surfaces is a very small fraction of the apparent area.[14] This actual area of contact, caused by asperities increases with pressure. The development of the atomic force microscope (ca. 1986) enabled scientists to study friction at the atomic scale,[13] showing that, on that scale, dry friction is the product of the inter-surface shear stress and the contact area. These two discoveries explain Amonton’s first law (below); the macroscopic proportionality between normal force and static frictional force between dry surfaces.

Laws of dry friction

The elementary property of sliding (kinetic) friction were discovered by experiment in the 15th to 18th centuries and were expressed as three empirical laws:

- Amontons’ First Law: The force of friction is directly proportional to the applied load.

- Amontons’ Second Law: The force of friction is independent of the apparent area of contact.

- Coulomb’s Law of Friction: Kinetic friction is independent of the sliding velocity.

Dry friction

Dry friction resists relative lateral motion of two solid surfaces in contact. The two regimes of dry friction are ‘static friction’ («stiction») between non-moving surfaces, and kinetic friction (sometimes called sliding friction or dynamic friction) between moving surfaces.

Coulomb friction, named after Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, is an approximate model used to calculate the force of dry friction. It is governed by the model:

where

The Coulomb friction

The force of friction is always exerted in a direction that opposes movement (for kinetic friction) or potential movement (for static friction) between the two surfaces. For example, a curling stone sliding along the ice experiences a kinetic force slowing it down. For an example of potential movement, the drive wheels of an accelerating car experience a frictional force pointing forward; if they did not, the wheels would spin, and the rubber would slide backwards along the pavement. Note that it is not the direction of movement of the vehicle they oppose, it is the direction of (potential) sliding between tire and road.

Normal force

Free-body diagram for a block on a ramp. Arrows are vectors indicating directions and magnitudes of forces. N is the normal force, mg is the force of gravity, and Ff is the force of friction.

The normal force is defined as the net force compressing two parallel surfaces together, and its direction is perpendicular to the surfaces. In the simple case of a mass resting on a horizontal surface, the only component of the normal force is the force due to gravity, where

The friction coefficient is an empirical (experimentally measured) structural property that depends only on various aspects of the contacting materials, such as surface roughness. The coefficient of friction is not a function of mass or volume. For instance, a large aluminum block has the same coefficient of friction as a small aluminum block. However, the magnitude of the friction force itself depends on the normal force, and hence on the mass of the block.

Depending on the situation, the calculation of the normal force

If the object is on a tilted surface such as an inclined plane, the normal force from gravity is smaller than

In general, process for solving any statics problem with friction is to treat contacting surfaces tentatively as immovable so that the corresponding tangential reaction force between them can be calculated. If this frictional reaction force satisfies

Coefficient of friction

|

This section needs expansion with: explanation of why kinetic friction is always lower. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020) |

The coefficient of friction (COF), often symbolized by the Greek letter µ, is a dimensionless scalar value which equals the ratio of the force of friction between two bodies and the force pressing them together, either during or at the onset of slipping. The coefficient of friction depends on the materials used; for example, ice on steel has a low coefficient of friction, while rubber on pavement has a high coefficient of friction. Coefficients of friction range from near zero to greater than one. The coefficient of friction between two surfaces of similar metals is greater than that between two surfaces of different metals; for example, brass has a higher coefficient of friction when moved against brass, but less if moved against steel or aluminum.[23]

For surfaces at rest relative to each other,

For surfaces in relative motion

Arthur Morin introduced the term and demonstrated the utility of the coefficient of friction.[12] The coefficient of friction is an empirical measurement — it has to be measured experimentally, and cannot be found through calculations.[24] Rougher surfaces tend to have higher effective values. Both static and kinetic coefficients of friction depend on the pair of surfaces in contact; for a given pair of surfaces, the coefficient of static friction is usually larger than that of kinetic friction; in some sets the two coefficients are equal, such as teflon-on-teflon.

Most dry materials in combination have friction coefficient values between 0.3 and 0.6. Values outside this range are rarer, but teflon, for example, can have a coefficient as low as 0.04. A value of zero would mean no friction at all, an elusive property. Rubber in contact with other surfaces can yield friction coefficients from 1 to 2. Occasionally it is maintained that μ is always < 1, but this is not true. While in most relevant applications μ < 1, a value above 1 merely implies that the force required to slide an object along the surface is greater than the normal force of the surface on the object. For example, silicone rubber or acrylic rubber-coated surfaces have a coefficient of friction that can be substantially larger than 1.

While it is often stated that the COF is a «material property,» it is better categorized as a «system property.» Unlike true material properties (such as conductivity, dielectric constant, yield strength), the COF for any two materials depends on system variables like temperature, velocity, atmosphere and also what are now popularly described as aging and deaging times; as well as on geometric properties of the interface between the materials, namely surface structure.[1] For example, a copper pin sliding against a thick copper plate can have a COF that varies from 0.6 at low speeds (metal sliding against metal) to below 0.2 at high speeds when the copper surface begins to melt due to frictional heating. The latter speed, of course, does not determine the COF uniquely; if the pin diameter is increased so that the frictional heating is removed rapidly, the temperature drops, the pin remains solid and the COF rises to that of a ‘low speed’ test.«Coefficient of Friction — an overview — ScienceDirect Topics». Retrieved 9 May 2022.

Approximate coefficients of friction

| Materials | Static Friction,  |

Kinetic/Sliding Friction,

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry and clean | Lubricated | Dry and clean | Lubricated | ||

| Aluminium | Steel | 0.61[25] | 0.47[25] | ||

| Aluminium | Aluminium | 1.05–1.35[25] | 0.3[25] | 1.4[25]–1.5[26] | |

| Gold | Gold | 2.5[26] | |||

| Platinum | Platinum | 1.2[25] | 0.25[25] | 3.0[26] | |

| Silver | Silver | 1.4[25] | 0.55[25] | 1.5[26] | |

| Alumina ceramic | Silicon nitride ceramic | 0.004 (wet)[27] | |||

| BAM (Ceramic alloy AlMgB14) | Titanium boride (TiB2) | 0.04–0.05[28] | 0.02[29][30] | ||

| Brass | Steel | 0.35–0.51[25] | 0.19[25] | 0.44[25] | |

| Cast iron | Copper | 1.05[25] | 0.29[25] | ||

| Cast iron | Zinc | 0.85[25] | 0.21[25] | ||

| Concrete | Rubber | 1.0 | 0.30 (wet) | 0.6–0.85[25] | 0.45–0.75 (wet)[25] |

| Concrete | Wood | 0.62[25][31] | |||

| Copper | Glass | 0.68[32] | 0.53[32] | ||

| Copper | Steel | 0.53[32] | 0.36[25][32] | 0.18[32] | |

| Glass | Glass | 0.9–1.0[25][32] | 0.005–0.01[32] | 0.4[25][32] | 0.09–0.116[32] |

| Human synovial fluid | Human cartilage | 0.01[33] | 0.003[33] | ||

| Ice | Ice | 0.02–0.09[34] | |||

| Polyethene | Steel | 0.2[25][34] | 0.2[25][34] | ||

| PTFE (Teflon) | PTFE (Teflon) | 0.04[25][34] | 0.04[25][34] | 0.04[25] | |

| Steel | Ice | 0.03[34] | |||

| Steel | PTFE (Teflon) | 0.04[25]−0.2[34] | 0.04[25] | 0.04[25] | |

| Steel | Steel | 0.74[25]−0.80[34] | 0.005–0.23[32][34] | 0.42–0.62[25][32] | 0.029–0.19[32] |

| Wood | Metal | 0.2–0.6[25][31] | 0.2 (wet)[25][31] | 0.49[32] | 0.075[32] |

| Wood | Wood | 0.25–0.62[25][31][32] | 0.2 (wet)[25][31] | 0.32–0.48[32] | 0.067–0.167[32] |

Under certain conditions some materials have very low friction coefficients. An example is (highly ordered pyrolytic) graphite which can have a friction coefficient below 0.01.[35]

This ultralow-friction regime is called superlubricity.

Static friction

When the mass is not moving, the object experiences static friction. The friction increases as the applied force increases until the block moves. After the block moves, it experiences kinetic friction, which is less than the maximum static friction.

Static friction is friction between two or more solid objects that are not moving relative to each other. For example, static friction can prevent an object from sliding down a sloped surface. The coefficient of static friction, typically denoted as μs, is usually higher than the coefficient of kinetic friction. Static friction is considered to arise as the result of surface roughness features across multiple length scales at solid surfaces. These features, known as asperities are present down to nano-scale dimensions and result in true solid to solid contact existing only at a limited number of points accounting for only a fraction of the apparent or nominal contact area.[36] The linearity between applied load and true contact area, arising from asperity deformation, gives rise to the linearity between static frictional force and normal force, found for typical Amonton–Coulomb type friction.[37]

The static friction force must be overcome by an applied force before an object can move. The maximum possible friction force between two surfaces before sliding begins is the product of the coefficient of static friction and the normal force:

An example of static friction is the force that prevents a car wheel from slipping as it rolls on the ground. Even though the wheel is in motion, the patch of the tire in contact with the ground is stationary relative to the ground, so it is static rather than kinetic friction. Upon slipping, the wheel friction changes to kinetic friction. An anti-lock braking system operates on the principle of allowing a locked wheel to resume rotating so that the car maintains static friction.

The maximum value of static friction, when motion is impending, is sometimes referred to as limiting friction,[39]

although this term is not used universally.[3]

Kinetic friction

Kinetic friction, also known as dynamic friction or sliding friction, occurs when two objects are moving relative to each other and rub together (like a sled on the ground). The coefficient of kinetic friction is typically denoted as μk, and is usually less than the coefficient of static friction for the same materials.[40][41] However, Richard Feynman comments that «with dry metals it is very hard to show any difference.»[42]

The friction force between two surfaces after sliding begins is the product of the coefficient of kinetic friction and the normal force:

New models are beginning to show how kinetic friction can be greater than static friction. Kinetic friction is now understood, in many cases, to be primarily caused by chemical bonding between the surfaces, rather than interlocking asperities;[44] however, in many other cases roughness effects are dominant, for example in rubber to road friction. Surface roughness and contact area affect kinetic friction for micro- and nano-scale objects where surface area forces dominate inertial forces.[45]

The origin of kinetic friction at nanoscale can be explained by thermodynamics.[46] Upon sliding, new surface forms at the back of a sliding true contact, and existing surface disappears at the front of it. Since all surfaces involve the thermodynamic surface energy, work must be spent in creating the new surface, and energy is released as heat in removing the surface. Thus, a force is required to move the back of the contact, and frictional heat is released at the front.

Angle of friction, θ, when block just starts to slide.

Angle of friction

For the maximum angle of static friction between granular materials, see Angle of repose.

For certain applications, it is more useful to define static friction in terms of the maximum angle before which one of the items will begin sliding. This is called the angle of friction or friction angle. It is defined as:

and thus:

where

Friction at the atomic level

Determining the forces required to move atoms past each other is a challenge in designing nanomachines. In 2008 scientists for the first time were able to move a single atom across a surface, and measure the forces required. Using ultrahigh vacuum and nearly zero temperature (5 K), a modified atomic force microscope was used to drag a cobalt atom, and a carbon monoxide molecule, across surfaces of copper and platinum.[48]

Limitations of the Coulomb model

The Coulomb approximation follows from the assumptions that: surfaces are in atomically close contact only over a small fraction of their overall area; that this contact area is proportional to the normal force (until saturation, which takes place when all area is in atomic contact); and that the frictional force is proportional to the applied normal force, independently of the contact area. The Coulomb approximation is fundamentally an empirical construct. It is a rule-of-thumb describing the approximate outcome of an extremely complicated physical interaction. The strength of the approximation is its simplicity and versatility. Though the relationship between normal force and frictional force is not exactly linear (and so the frictional force is not entirely independent of the contact area of the surfaces), the Coulomb approximation is an adequate representation of friction for the analysis of many physical systems.

When the surfaces are conjoined, Coulomb friction becomes a very poor approximation (for example, adhesive tape resists sliding even when there is no normal force, or a negative normal force). In this case, the frictional force may depend strongly on the area of contact. Some drag racing tires are adhesive for this reason. However, despite the complexity of the fundamental physics behind friction, the relationships are accurate enough to be useful in many applications.

«Negative» coefficient of friction

As of 2012, a single study has demonstrated the potential for an effectively negative coefficient of friction in the low-load regime, meaning that a decrease in normal force leads to an increase in friction. This contradicts everyday experience in which an increase in normal force leads to an increase in friction.[49] This was reported in the journal Nature in October 2012 and involved the friction encountered by an atomic force microscope stylus when dragged across a graphene sheet in the presence of graphene-adsorbed oxygen.[49]

Numerical simulation of the Coulomb model

Despite being a simplified model of friction, the Coulomb model is useful in many numerical simulation applications such as multibody systems and granular material. Even its most simple expression encapsulates the fundamental effects of sticking and sliding which are required in many applied cases, although specific algorithms have to be designed in order to efficiently numerically integrate mechanical systems with Coulomb friction and bilateral or unilateral contact.[50][51][52][53][54] Some quite nonlinear effects, such as the so-called Painlevé paradoxes, may be encountered with Coulomb friction.[55]

Dry friction and instabilities

Dry friction can induce several types of instabilities in mechanical systems which display a stable behaviour in the absence of friction.[56]

These instabilities may be caused by the decrease of the friction force with an increasing velocity of sliding, by material expansion due to heat generation during friction (the thermo-elastic instabilities), or by pure dynamic effects of sliding of two elastic materials (the Adams–Martins instabilities). The latter were originally discovered in 1995 by George G. Adams and João Arménio Correia Martins for smooth surfaces[57][58] and were later found in periodic rough surfaces.[59] In particular, friction-related dynamical instabilities are thought to be responsible for brake squeal and the ‘song’ of a glass harp,[60][61] phenomena which involve stick and slip, modelled as a drop of friction coefficient with velocity.[62]

A practically important case is the self-oscillation of the strings of bowed instruments such as the violin, cello, hurdy-gurdy, erhu, etc.

A connection between dry friction and flutter instability in a simple mechanical system has been discovered,[63] watch the movie Archived 2015-01-10 at the Wayback Machine for more details.

Frictional instabilities can lead to the formation of new self-organized patterns (or «secondary structures») at the sliding interface, such as in-situ formed tribofilms which are utilized for the reduction of friction and wear in so-called self-lubricating materials.[64]

Fluid friction

Fluid friction occurs between fluid layers that are moving relative to each other. This internal resistance to flow is named viscosity. In everyday terms, the viscosity of a fluid is described as its «thickness». Thus, water is «thin», having a lower viscosity, while honey is «thick», having a higher viscosity. The less viscous the fluid, the greater its ease of deformation or movement.

All real fluids (except superfluids) offer some resistance to shearing and therefore are viscous. For teaching and explanatory purposes it is helpful to use the concept of an inviscid fluid or an ideal fluid which offers no resistance to shearing and so is not viscous.

Lubricated friction

Lubricated friction is a case of fluid friction where a fluid separates two solid surfaces. Lubrication is a technique employed to reduce wear of one or both surfaces in close proximity moving relative to each another by interposing a substance called a lubricant between the surfaces.

In most cases the applied load is carried by pressure generated within the fluid due to the frictional viscous resistance to motion of the lubricating fluid between the surfaces. Adequate lubrication allows smooth continuous operation of equipment, with only mild wear, and without excessive stresses or seizures at bearings. When lubrication breaks down, metal or other components can rub destructively over each other, causing heat and possibly damage or failure.

Skin friction

Skin friction arises from the interaction between the fluid and the skin of the body, and is directly related to the area of the surface of the body that is in contact with the fluid. Skin friction follows the drag equation and rises with the square of the velocity.

Skin friction is caused by viscous drag in the boundary layer around the object. There are two ways to decrease skin friction: the first is to shape the moving body so that smooth flow is possible, like an airfoil. The second method is to decrease the length and cross-section of the moving object as much as is practicable.

Internal friction

Internal friction is the force resisting motion between the elements making up a solid material while it undergoes deformation.

Plastic deformation in solids is an irreversible change in the internal molecular structure of an object. This change may be due to either (or both) an applied force or a change in temperature. The change of an object’s shape is called strain. The force causing it is called stress.

Elastic deformation in solids is reversible change in the internal molecular structure of an object. Stress does not necessarily cause permanent change. As deformation occurs, internal forces oppose the applied force. If the applied stress is not too large these opposing forces may completely resist the applied force, allowing the object to assume a new equilibrium state and to return to its original shape when the force is removed. This is known as elastic deformation or elasticity.

Radiation friction

As a consequence of light pressure, Einstein[65] in 1909 predicted the existence of «radiation friction» which would oppose the movement of matter. He wrote, «radiation will exert pressure on both sides of the plate. The forces of pressure exerted on the two sides are equal if the plate is at rest. However, if it is in motion, more radiation will be reflected on the surface that is ahead during the motion (front surface) than on the back surface. The backward-acting force of pressure exerted on the front surface is thus larger than the force of pressure acting on the back. Hence, as the resultant of the two forces, there remains a force that counteracts the motion of the plate and that increases with the velocity of the plate. We will call this resultant ‘radiation friction’ in brief.»

Other types of friction

Rolling resistance

Rolling resistance is the force that resists the rolling of a wheel or other circular object along a surface caused by deformations in the object or surface. Generally the force of rolling resistance is less than that associated with kinetic friction.[66] Typical values for the coefficient of rolling resistance are 0.001.[67]

One of the most common examples of rolling resistance is the movement of motor vehicle tires on a road, a process which generates heat and sound as by-products.[68]

Braking friction

Any wheel equipped with a brake is capable of generating a large retarding force, usually for the purpose of slowing and stopping a vehicle or piece of rotating machinery. Braking friction differs from rolling friction because the coefficient of friction for rolling friction is small whereas the coefficient of friction for braking friction is designed to be large by choice of materials for brake pads.

Triboelectric effect

Rubbing dissimilar materials against one another can cause a build-up of electrostatic charge, which can be hazardous if flammable gases or vapours are present. When the static build-up discharges, explosions can be caused by ignition of the flammable mixture.

Belt friction

Belt friction is a physical property observed from the forces acting on a belt wrapped around a pulley, when one end is being pulled. The resulting tension, which acts on both ends of the belt, can be modeled by the belt friction equation.

In practice, the theoretical tension acting on the belt or rope calculated by the belt friction equation can be compared to the maximum tension the belt can support. This helps a designer of such a rig to know how many times the belt or rope must be wrapped around the pulley to prevent it from slipping. Mountain climbers and sailing crews demonstrate a standard knowledge of belt friction when accomplishing basic tasks.

Reducing friction

Devices

Devices such as wheels, ball bearings, roller bearings, and air cushion or other types of fluid bearings can change sliding friction into a much smaller type of rolling friction.

Many thermoplastic materials such as nylon, HDPE and PTFE are commonly used in low friction bearings. They are especially useful because the coefficient of friction falls with increasing imposed load.[69] For improved wear resistance, very high molecular weight grades are usually specified for heavy duty or critical bearings.

Lubricants

A common way to reduce friction is by using a lubricant, such as oil, water, or grease, which is placed between the two surfaces, often dramatically lessening the coefficient of friction. The science of friction and lubrication is called tribology. Lubricant technology is when lubricants are mixed with the application of science, especially to industrial or commercial objectives.

Superlubricity, a recently discovered effect, has been observed in graphite: it is the substantial decrease of friction between two sliding objects, approaching zero levels. A very small amount of frictional energy would still be dissipated.

Lubricants to overcome friction need not always be thin, turbulent fluids or powdery solids such as graphite and talc; acoustic lubrication actually uses sound as a lubricant.