- Главная

- Игры

- Викторины

- Викторины для детей с ответами

- Познавательные викторины для детей

- Литературные викторины для детей

- Викторины по литературе для детей по форме

- Викторины по сказкам

- Викторины по сказкам народов мира

- Викторины по русским народным сказкам

Выбрав правильный на ваш взгляд вариант ответа, жмите на кнопку «Проверить». Если хотите сразу увидеть правильные ответы, ищите под вопросами ссылку «Посмотреть правильные ответы»

Подпишитесь на нас в ВКонтакте, чтобы не пропускать наши новинки.

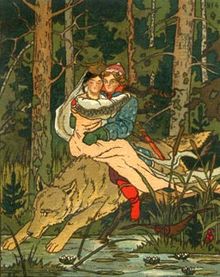

Ivan Tsarevich and the Grey Wolf (Zvorykin)

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; «story»; plural Russian: ска́зки, romanized: skazki) is a fairy tale from Russia.

Various sub-genres of skazka exist. A volshebnaya skazka [волше́бная ска́зка] (literally «magical tale») is considered a magical tale.[1][need quotation to verify] Skazki o zhivotnykh are tales about animals and bytovye skazki are tales about household life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail different types of folktales.

Similarly to Western European traditions, especially the German-language collection published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. Scholars of folklore still refer to his collected texts when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories, describing the stages of their plots and the classification of the characters based on their functions, was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century, by Vladimir Propp (1895-1970).

History[edit]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[2] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[3]

Popular fairy tale writer, Alexander Afanasyev

Effects of Communism[edit]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[3] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in Anatoliy Mityaev’s Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev’s The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[4] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian’s passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[5] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences[edit]

Russian kids listening to a new fairy tale

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[6] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[7]

Cultural influences on Russian fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don’t ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man’s follies and mistakes, others appear pointless.» They were created to entertain the reader.[8]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play’s choreography from its Russian background.[9]

Formalism[edit]

From the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia, called Russian formalism by critics of the new school of thought.[10]

Analysis[edit]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[11][12] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[12]

A Russian Garland of Fairy Tales

Motif[edit]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the «simplest narrative unit.»[13] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson’s approach to folkloristics.[14] Thompson’s research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[15]

Structural[edit]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled «The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style».[13] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[16] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, «It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata.»[13]

Syntagmatic analysis, championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[17] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[16] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky’s definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[7] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[7][18] This methodology gives rise to Propp’s 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[18] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[7]

Alexander Nikiforov, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled «The Morphological Study of Folklore», Nikiforov states that «Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable.»[13] Since Nikiforov’s essay was written almost 2 years before Propp’s publication of Morphology of the Folktale[19], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[20] One source claims that Nikiforov’s work was «not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics» and failed to «keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts».[17] Nikiforov’s work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[19]

Writers and collectors[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[21] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[22]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm’s Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[21]

Alexander Pushkin[edit]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[23] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[24] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[25]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[26] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[27]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[28]

Corpus[edit]

According to scholarship, some of «most popular or most significant» types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][30]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | [b] |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre’s (Devil’s) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [c] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | [d] |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | [e] | |

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [f] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil’s Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | [g] |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [h] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [i][j][k] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | The Humpbacked Horse; The Firebird and Princess Vasilisa | [l] |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [m][n] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [o][p] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [q] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [r] |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Propp’s The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[29]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 301, «The Three Kingdoms and the Stolen Princesses», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 45 variants. The type was also the second «most frequently collected in Ukraine», with 31 texts.[31]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing «throughout Europe», is well known in Russia, where it found «its favorite soil».[32] Likewise, Jack Haney stated that type 307 was «most common» among East Slavs.[33]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 313, «The Magic Flight», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 41 variants. The type was also the «most frequently collected» in Ukraine, with 37 texts.[34]

- ^ Commenting on a Russian tale collected in the 20th century, Richard Dorson stated that the type was «one of the most widespread Russian Märchen».[35] In the East Slavic populations, scholarship registers 42 Russian variants, 25 Ukrainian and 10 Belarrussian.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch «[is] common among the various East European peoples.»[37]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type is popular among the East Slavs[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is «especially common in Russia».[39]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) «belongs to the core of» the Russian tale corpus, due to «the presence of numerous variants».[40]

- ^ Following Löwis de Menar’s study, Walter Puchner concluded on its diffusion especially in the East Slavic area.[41]

- ^ Stith Thompson also located this tale type across Russia and the Baltic regions.[42]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type «is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic».[43]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is «common among the East Slavs».[44]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[45]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «very common in all the East Slavic traditions».[46]

- ^ Wolfram Eberhard reported «45 variants in Russia alone».[47]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «a very common East Slavic type».[48]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «especially common in Russian and Ukrainian».[49]

References[edit]

- ^ «Magic tale (volshebnaia skazka), also called fairy tale». Kononenko, Natalie (2007). Slavic Folklore: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-33610-2.

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service». Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). «Russian Fairy Tales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). «‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Review: Back to Its Russian Roots». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). «Russian Formalism». Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). «The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique». Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. «What is a Folklore Motif?». www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). «AN OUTLINE OF PROPP’S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES» (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). «Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union». Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). «Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book».

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service.» Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Delarue, Paul. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ Haney, Jack V.; with Sibelan Forrester. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume III. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2021. p. 536.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Горяева, Б. Б. (2011). «Сюжет «Волшебник и его ученик» (at 325) в калмыцкой сказочной традиции». In: Oriental Studies (2): 153. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-volshebnik-i-ego-uchenik-at-325-v-kalmytskoy-skazochnoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 554. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). «Сказка «слепой и безногий» (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета». Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Krauss, Friedrich Salomo; Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Burt, Raymond I. and Puchner, Walter (eds). Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 615. ISBN 9783205994572.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram. Folktales of China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956. p. 143.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[edit]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

The Three Kingdoms (ATU 301):

- Лызлова Анастасия Сергеевна (2019). Cказки о трех царствах (медном, серебряном и золотом) в лубочной литературе и фольклорной традиции [FAIRY TALES ABOUT THREE KINGDOMS (THE COPPER, SILVER AND GOLD ONES) IN POPULAR LITERATURE AND RUSSIAN FOLK TRADITION]. Проблемы исторической поэтики, 17 (1): 26-44. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ckazki-o-treh-tsarstvah-mednom-serebryanom-i-zolotom-v-lubochnoy-literature-i-folklornoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре [RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES ON THE PLOT « THREE UNDERGROUND KINGDOMS» IN THE SIBERIAN REPERTOIRE]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия, (10): 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Терещенко Анна Васильевна (2017). Фольклорный сюжет «Три царства» в сопоставительном аспекте: на материале русских и селькупских сказок [COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FOLKLORE PLOT “THREE STOLEN PRINCESSES”: RUSSIAN AND SELKUP FAIRY TALES DATA]. Вестник Томского государственного педагогического университета, (6 (183)): 128-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/folklornyy-syuzhet-tri-tsarstva-v-sopostavitelnom-aspekte-na-materiale-russkih-i-selkupskih-skazok (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

Crafty Knowledge (ATU 325):

- Трошкова Анна Олеговна (2019). «Сюжет «Хитрая наука» (сус 325) в русской волшебной сказке» [THE PLOT “THE MAGICIAN AND HIS PUPIL” (NO. 325 OF THE COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS) IN THE RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE]. Вестник Марийского государственного университета, 13 (1 (33)): 98-107. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-hitraya-nauka-sus-325-v-russkoy-volshebnoy-skazke (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. «Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)». In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

- Troshkova, A (2019). «The tale type ‘The Magician and His Pupil’ in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)». Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376. (In Russian)

Mark the Rich or Marko Bogatyr (ATU 461):

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2017). Легенда о Христе в составе сказки о Марко Богатом: устные и книжные источники славянских повествований [LEGEND OF CHRIST WITHIN THE FOLKTALE ABOUT MARKO THE RICH: ORAL AND BOOK SOURCES OF SLAVIC NARRATIVES]. Вестник славянских культур, 46 (4): 122-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/legenda-o-hriste-v-sostave-skazki-o-marko-bogatom-ustnye-i-knizhnye-istochniki-slavyanskih-povestvovaniy (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2019). Разновидности сюжета о Марко Богатом (AaTh 930) в восточно- и южнославянских записях [VERSIONS OF THE PLOT ABOUT MARKO THE RICH (AATH 930) IN THE EAST- AND SOUTH SLAVIC TEXTS]. Вестник славянских культур, 52 (2): 104-116. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/raznovidnosti-syuzheta-o-marko-bogatom-aath-930-v-vostochno-i-yuzhnoslavyanskih-zapisyah (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

External links[edit]

Ivan Tsarevich and the Grey Wolf (Zvorykin)

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; «story»; plural Russian: ска́зки, romanized: skazki) is a fairy tale from Russia.

Various sub-genres of skazka exist. A volshebnaya skazka [волше́бная ска́зка] (literally «magical tale») is considered a magical tale.[1][need quotation to verify] Skazki o zhivotnykh are tales about animals and bytovye skazki are tales about household life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail different types of folktales.

Similarly to Western European traditions, especially the German-language collection published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. Scholars of folklore still refer to his collected texts when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories, describing the stages of their plots and the classification of the characters based on their functions, was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century, by Vladimir Propp (1895-1970).

History[edit]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[2] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[3]

Popular fairy tale writer, Alexander Afanasyev

Effects of Communism[edit]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[3] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in Anatoliy Mityaev’s Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev’s The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[4] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian’s passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[5] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences[edit]

Russian kids listening to a new fairy tale

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[6] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[7]

Cultural influences on Russian fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don’t ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man’s follies and mistakes, others appear pointless.» They were created to entertain the reader.[8]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play’s choreography from its Russian background.[9]

Formalism[edit]

From the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia, called Russian formalism by critics of the new school of thought.[10]

Analysis[edit]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[11][12] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[12]

A Russian Garland of Fairy Tales

Motif[edit]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the «simplest narrative unit.»[13] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson’s approach to folkloristics.[14] Thompson’s research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[15]

Structural[edit]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled «The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style».[13] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[16] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, «It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata.»[13]

Syntagmatic analysis, championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[17] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[16] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky’s definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[7] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[7][18] This methodology gives rise to Propp’s 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[18] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[7]

Alexander Nikiforov, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled «The Morphological Study of Folklore», Nikiforov states that «Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable.»[13] Since Nikiforov’s essay was written almost 2 years before Propp’s publication of Morphology of the Folktale[19], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[20] One source claims that Nikiforov’s work was «not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics» and failed to «keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts».[17] Nikiforov’s work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[19]

Writers and collectors[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[21] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[22]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm’s Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[21]

Alexander Pushkin[edit]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[23] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[24] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[25]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[26] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[27]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[28]

Corpus[edit]

According to scholarship, some of «most popular or most significant» types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][30]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | [b] |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre’s (Devil’s) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [c] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | [d] |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | [e] | |

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [f] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil’s Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | [g] |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [h] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [i][j][k] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | The Humpbacked Horse; The Firebird and Princess Vasilisa | [l] |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [m][n] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [o][p] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [q] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [r] |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Propp’s The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[29]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 301, «The Three Kingdoms and the Stolen Princesses», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 45 variants. The type was also the second «most frequently collected in Ukraine», with 31 texts.[31]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing «throughout Europe», is well known in Russia, where it found «its favorite soil».[32] Likewise, Jack Haney stated that type 307 was «most common» among East Slavs.[33]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 313, «The Magic Flight», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 41 variants. The type was also the «most frequently collected» in Ukraine, with 37 texts.[34]

- ^ Commenting on a Russian tale collected in the 20th century, Richard Dorson stated that the type was «one of the most widespread Russian Märchen».[35] In the East Slavic populations, scholarship registers 42 Russian variants, 25 Ukrainian and 10 Belarrussian.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch «[is] common among the various East European peoples.»[37]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type is popular among the East Slavs[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is «especially common in Russia».[39]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) «belongs to the core of» the Russian tale corpus, due to «the presence of numerous variants».[40]

- ^ Following Löwis de Menar’s study, Walter Puchner concluded on its diffusion especially in the East Slavic area.[41]

- ^ Stith Thompson also located this tale type across Russia and the Baltic regions.[42]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type «is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic».[43]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is «common among the East Slavs».[44]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[45]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «very common in all the East Slavic traditions».[46]

- ^ Wolfram Eberhard reported «45 variants in Russia alone».[47]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «a very common East Slavic type».[48]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «especially common in Russian and Ukrainian».[49]

References[edit]

- ^ «Magic tale (volshebnaia skazka), also called fairy tale». Kononenko, Natalie (2007). Slavic Folklore: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-33610-2.

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service». Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). «Russian Fairy Tales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). «‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Review: Back to Its Russian Roots». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). «Russian Formalism». Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). «The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique». Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. «What is a Folklore Motif?». www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). «AN OUTLINE OF PROPP’S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES» (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). «Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union». Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). «Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book».

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service.» Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Delarue, Paul. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ Haney, Jack V.; with Sibelan Forrester. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume III. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2021. p. 536.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Горяева, Б. Б. (2011). «Сюжет «Волшебник и его ученик» (at 325) в калмыцкой сказочной традиции». In: Oriental Studies (2): 153. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-volshebnik-i-ego-uchenik-at-325-v-kalmytskoy-skazochnoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 554. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). «Сказка «слепой и безногий» (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета». Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Krauss, Friedrich Salomo; Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Burt, Raymond I. and Puchner, Walter (eds). Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 615. ISBN 9783205994572.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram. Folktales of China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956. p. 143.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[edit]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

The Three Kingdoms (ATU 301):

- Лызлова Анастасия Сергеевна (2019). Cказки о трех царствах (медном, серебряном и золотом) в лубочной литературе и фольклорной традиции [FAIRY TALES ABOUT THREE KINGDOMS (THE COPPER, SILVER AND GOLD ONES) IN POPULAR LITERATURE AND RUSSIAN FOLK TRADITION]. Проблемы исторической поэтики, 17 (1): 26-44. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ckazki-o-treh-tsarstvah-mednom-serebryanom-i-zolotom-v-lubochnoy-literature-i-folklornoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре [RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES ON THE PLOT « THREE UNDERGROUND KINGDOMS» IN THE SIBERIAN REPERTOIRE]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия, (10): 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Терещенко Анна Васильевна (2017). Фольклорный сюжет «Три царства» в сопоставительном аспекте: на материале русских и селькупских сказок [COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FOLKLORE PLOT “THREE STOLEN PRINCESSES”: RUSSIAN AND SELKUP FAIRY TALES DATA]. Вестник Томского государственного педагогического университета, (6 (183)): 128-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/folklornyy-syuzhet-tri-tsarstva-v-sopostavitelnom-aspekte-na-materiale-russkih-i-selkupskih-skazok (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

Crafty Knowledge (ATU 325):

- Трошкова Анна Олеговна (2019). «Сюжет «Хитрая наука» (сус 325) в русской волшебной сказке» [THE PLOT “THE MAGICIAN AND HIS PUPIL” (NO. 325 OF THE COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS) IN THE RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE]. Вестник Марийского государственного университета, 13 (1 (33)): 98-107. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-hitraya-nauka-sus-325-v-russkoy-volshebnoy-skazke (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. «Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)». In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

- Troshkova, A (2019). «The tale type ‘The Magician and His Pupil’ in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)». Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376. (In Russian)

Mark the Rich or Marko Bogatyr (ATU 461):

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2017). Легенда о Христе в составе сказки о Марко Богатом: устные и книжные источники славянских повествований [LEGEND OF CHRIST WITHIN THE FOLKTALE ABOUT MARKO THE RICH: ORAL AND BOOK SOURCES OF SLAVIC NARRATIVES]. Вестник славянских культур, 46 (4): 122-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/legenda-o-hriste-v-sostave-skazki-o-marko-bogatom-ustnye-i-knizhnye-istochniki-slavyanskih-povestvovaniy (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2019). Разновидности сюжета о Марко Богатом (AaTh 930) в восточно- и южнославянских записях [VERSIONS OF THE PLOT ABOUT MARKO THE RICH (AATH 930) IN THE EAST- AND SOUTH SLAVIC TEXTS]. Вестник славянских культур, 52 (2): 104-116. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/raznovidnosti-syuzheta-o-marko-bogatom-aath-930-v-vostochno-i-yuzhnoslavyanskih-zapisyah (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

External links[edit]

Викторина по русским народным сказкам «Знатоки сказок»

Уважаемые подписчики, мы предлогаем вам проверить свои знания в области Русских народных сказок. Желаем вам удачно пройти викторину и хорошо провести время!

Начало теста:

- <

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

Какие птицы унесли братца, в то время как сестрица загулялась-заигралась?

Варианты ответов:

- гуси-лебеди

- сороки-вороны

- утки-крякушки

В кого превратился братец Иванушка, который не послушался сестрицу Аленушку?

Варианты ответов:

- в ягнёночка

- в барашка

- в козлёночка

От кого терпит обиды добрая девочка-сирота в сказке «Морозко»?

Варианты ответов:

- от злой мачехи

- от Змея Горыныча

- от бабы Яги

Кто поёт песенку «Несёт меня лиса за тёмные леса», призывая на помощь кота?

Варианты ответов:

- петух

- гусь

- индюк

У бабы Яги необычный дом. На каких ножках он стоит?

Варианты ответов:

- на железных

- на курьих

- на деревянных

Как называется сказка, из которой песенка: «Вы, детушки! Вы, козлятушки! Отопритеся, отворитеся…»?

Варианты ответов:

- «Волк и семеро козлят»

- «Волк и три поросёнка

- «Ненасытный Волк»

У петушка красивый гребешок. Какой он?

Варианты ответов:

- бронзовый

- серебряный

- золотой

Какой овощ тянули дедка, бабка, внучка, Жучка, кошка, мышка?

Варианты ответов:

- редьку

- редиску

- репку

В сказке «По щучьему веленью» какие предметы с водой сами умели ходить?

Варианты ответов:

- вёдра

- чайники

- кастрюли

. Кто разрушил теремок в сказке «Теремок»?

Варианты ответов:

- медведь

- чудо-юдо

- волк

Какой из перечисленных персонажей относится к персонажам русских народных сказок?

Варианты ответов:

- Баба-Яга

- Золушка

- Буратино

Кто из перечисленных авторов литературно обрабатывал русские сказки?

Варианты ответов:

- Л. Толстой

- К. Чуковский

- А. Афанасьев

Кто в русских сказках чаще всего помогает главному герою?

Варианты ответов:

- Животные

- Ожившие вещи

- Демонические существа

Какие сказки рассказывают нам о превращениях и поисках потерянного?

Варианты ответов:

- Волшебные сказки

- Анекдотические сказки

- Сказки о животных

Как в старину называлась сказка?

Варианты ответов:

- Песнь

- Небылица

- Баснь

Какая из перечисленных сказок о животных?

Варианты ответов:

- Ведьмина дочка

- Журавль и цапля

- Война грибов

Кто из героев взял в жены Елену премудрую?

Варианты ответов:

- Иван-царевич

- Емеля

- Солдат

Какое животное в русских народных сказках является символом хитрости и изворотливости?

Варианты ответов:

- Волк

- Кот

- Лиса

Какую из перечисленных сказок написал А. С. Пушкин?

Варианты ответов:

- Мойдодыр

- Три медведя

- Сказка о золотом петушке

Кто из русских художников писал картины по мотивам русских народных сказок?

Варианты ответов:

- В. Васнецов

- И. Шишкин

- О. Кипренский

Идет подсчет результатов

11

Сообщить о нарушение

Ваше сообщение отправлено, мы постараемся разобраться в ближайшее время.

Отправить сообщение

83 просмотров

Верно 0 / С ошибками 17

- 0

- 0

Популярные тесты

-

Тест Роршаха расскажет, что сейчас творится у вас в голове

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 447 381

655 545 просмотров — 22 февраля 2019

Пройти тест -

Угадайте воинские звания России по погонам

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 622 746

1 034 727 просмотров — 11 марта 2019

Пройти тест -

Тест, который покажет, каким животным вы являетесь в душе.

HTML-код

Никитин КонстантинКоличество прохождений: 417 071

628 856 просмотров — 11 января 2017

Пройти тест -

Насколько хорошо вы знаете географию России?

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 339 686

534 348 просмотров — 28 января 2019

Пройти тест -

Догадливы и эрудированны ли вы настолько, чтобы парировать 15 вопросов обо всём?

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 311 276

614 483 просмотров — 12 марта 2019

Пройти тест -

Тест на общие знания, который без ошибок проходят лишь единицы. А получится ли у вас?

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 495 019

790 783 просмотров — 05 марта 2019

Пройти тест -

Если закончите цитаты из советских фильмов на 10/10, то вы наверняка родились в СССР

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 325 112

447 151 просмотров — 22 июля 2022

Пройти тест -

Главный тест на общие знания: насколько ты умён?

HTML-код

Всякие Научные ШтукиКоличество прохождений: 472 493

672 206 просмотров — 28 февраля 2019

Пройти тест -

Тест, который осилят лишь настоящие профи в мировой географии

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 297 797

478 227 просмотров — 07 марта 2019

Пройти тест -

Каково ваше имя, судя по вашему характеру

HTML-код

Тесты от ШпицаКоличество прохождений: 561 795

1 027 067 просмотров — 30 августа 2018

Пройти тест -

Ваша эрудиция на высоте, если осилите наш тест хотя бы на 8/11 — ТЕСТ

HTML-код

АннаКоличество прохождений: 429 488

922 172 просмотров — 04 апреля 2020

Пройти тест -

Не заглядывая в Гугл, сможете ответить хотя бы на половину вопросов этого теста?

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 436 365

717 367 просмотров — 22 августа 2019

Пройти тест -

Тест по фильмам СССР: Сможете пройти его на все 10/10? (Часть 2)

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 357 561

577 275 просмотров — 04 марта 2019

Пройти тест -

Сумеешь угадать фильм с одного кадра?

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 301 762

560 220 просмотров — 15 июня 2018

Пройти тест -

Никто не может ответить больше чем на 7 из 10 вопросов в этом тесте на IQ

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 356 484

709 009 просмотров — 25 октября 2019

Пройти тест -

На какое животное вы похожи, когда злитесь?

HTML-код

Никитин КонстантинКоличество прохождений: 697 347

1 111 683 просмотров — 22 декабря 2016

Пройти тест -

Если вы наберете 11/12 в этом тесте на эрудицию, то такого начитанного и разностороннего человека еще поискать

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 583 892

1 213 739 просмотров — 04 августа 2019

Пройти тест -

А вы сможете продолжить эти 13 крылатых фраз?

HTML-код

ВладленаКоличество прохождений: 452 292

701 523 просмотров — 31 марта 2020

Пройти тест -

Тест на общие знания, который на 11/11 осилит лишь настоящий эрудит

HTML-код

АннаКоличество прохождений: 447 808

744 397 просмотров — 30 марта 2020

Пройти тест -

Докажите свою высокоинтеллектуальность, набрав в нашем тесте на общие знания 13/13

HTML-код

АндрейКоличество прохождений: 309 976

550 052 просмотров — 21 марта 2019

Пройти тест

HTML-код для вставки на сайт

Разрешить комментарии

Автор теста запретил комментарии

Блок Новинок и Популярных тестов

Теперь тесты из блоков новинок и популярных отображаются внутри вашего сайта, что увеличивает просмотры ваших страниц в 5 раз!

Все комментарии после публикации проходят строгую модерацию!

OK

Сегодня все дети начинают знакомство с литературным языком со сказок. Самые первые образчики, на протяжении последних ста лет в России, – это всеми любимые «Курочка Ряба», «Колобок» и «Репка». Несмотря на то, что тексты мы знаем наизусть, данные сюжеты настолько старинны, что мы не всегда уже понимаем, какой именно урок должны извлечь из них добры молодцы и красны девицы.

Происходит так потому, что за долгие годы эти истории частично растеряли персонажей и события.

«Курочка Ряба»

В старину текст этой сказки был гораздо более богат событиями. За разбитым яичком следовала целая череда несчастий, нарастающих по силе и степени трагизма:

Жили-были дед да баба,

У них была курочка ряба.

Снесла курочка яичко:

Пестрó, вострó, костянó, мудренó, —

Посадила яичко в осиновое дупёлко,

В кут — под лавку.

Мышка бежала, хвостом вернула,

Яичко приломала.

Об этом яичке дед стал плакать,

Бабка рыдать,

Вереи — хохотать,

Курицы летать,

Ворота скрипеть,

Сор под порогом закурился,

Двери побутусились, тын рассыпался,

Верх на избе зашатался…

А курочка ряба им говорит:

Дед не плачь, бабка не рыдай,

Куры не летайте,

Ворота не скрипите, сор под порогом

Не закуривайся,

Тын не рассыпайся,

Верх на избе не шатайся —

Снесу вам еще яичко:

Пестрó, вострó, костянó, мудренó,

Яичко не простое — золотое.

В более позднем варианте страшные последствия ничтожного происшествия другие: дед и баба плачут — сорока ногу изломала — тын расшатался — дуб с себя листочки посшибал — попова дочь вёдра разбила — попадья выкинула пироги за окошко (или кадку с тестом перевернула) — поп церковные книги порвал, разбежался и ударился о косяк и т. д. Всего известно несколько десятков различных вариантов этой сказки. Такое кумулятивное (нарастающее) построение сюжета делает ее комической – незначительное событие приводит к мировым катастрофам. В принципе, в современном мире эту старинную логику мы привыкли описывать «эффектом бабочки».

Существует огромное множество научных трактовок древних символов, присутствующих в сказке. Владимир Топоров (советский лингвист и филолог, основоположник «теории основного мифа») видел в ней мотив «Мирового яйца», из которого рождается мир. Поэтому старый мир и умирает. Мышь в данном случае – разрушительный образ стихии, связанный с подземным царством. Кстати, непонятную фразу о том, что «Вереи начинают хохотать» тоже объясняют именно с этой точки зрения. Вереи – это столбы, на которые навешивались ворота, важный элемент, поддерживающий «границу существующего мира» — дома. А хохотали они, в преддверии ужасного разрушения, как считают исследователи, вполне в рамках старинной славянской традиции провожать покойников шумным весельем. Это странное на первый взгляд поведение объясняется мудрым отношением наших предков к смерти. В ней они всегда видели обещание новой жизни. Смех в данном случае превращал смерть в рождение, а сказка из слегка нелогичной и детской превращается в космогоническую модель вселенной. Поэтому Курочка и обещает снести новое яичко, лучше прежнего. Все эти подробности сказка в основном потеряла в XIX веке. Литературный вариант, который сегодня наиболее известен, был записан в 1864 году Ушинским.

«Репка»

Рисунки к сказке из сборника А. Н. Афанасьева

Эта сказка также претерпела некоторые изменения, но смысл ее от этого не исказился. Сказка была записана в XIX веке в Архангельской губернии исследователем фольклора А. Н. Афанасьевым. В 1863 году он включил ее в свой сборник «Народные русские сказки». В первоначальном фольклорном варианте речь шла о «ногах» которые приходили по очереди на помощь:

«Пришла дрýга нóга; дрýга нóга за нóгу, нóга за сучку, сучка за внучку, внучка за бабку, бабка за дедку, дедка за репку, тянут-потянут, вытянуть не можут.»

<

Рисунок с обложки книги русских сказок 1916 г.

Автор привычного нам текста – тот же знаменитый русский педагог и писатель Константин Дмитриевич Ушинский. Он очень мудро дал собачке имя. Кстати, сейчас даже существует шутка по поводу того, что Жучка, — единственное поименованное существо в сказке, скрывает таким образом более грубое обращение. Неизвестные шутники даже не знают, насколько они правы. В дальнейшем при пересказах и Толстой и Даль эту кличку сохранили. Судя по некоторым источникам, в сказке раньше было больше действующих лиц, но тут, возможно, каждый рассказчик в старину мог проявлять фантазию, на то оно и устное народное творчество. В остальном же сюжет этой сказки-цепочки остается прежним, и говорит она, конечно, о взаимовыручке и о том, что даже самое маленькое усилие может помочь общему делу.

«Колобок»

Этот персонаж, который, как известно, плохо кончил, имеет, вероятно, очень древние корни. Само по себе кулинарное изделие из нашей кухни уже ушло, но память о нем в исторических документах сохранилась. Так, например, в московской «Росписи царским кушаньям», созданной в 1610—1613 годах упоминается блюдо Колоб, состоящее из 3 лопаток муки крупчатки, 25 яиц и 3 гривенок сала говяжьего. Судя по количеству яиц, колоб, подаваемый к царскому столу был велик. Не то что у старухи, которая «по сусекам поскребла».

По поводу старинной интерпретации этого сюжета сейчас в сети распространена версия, которая, правда, дается без ссылок на серьезные источники, но выглядит логичной и поэтому достаточно привлекательной. Считается, что Колобок на самом деле от каждого из встреченных животных укатывался слегка надкусанным:

«Вепрь кусочек откусил, Ворон отклевал, Медведь бок примял, Волк часть съел, пока Лиса совсем не съела.»

Согласно этой версии таким образом детишкам в старину объяснялись основы астрономии и календаря – все более уменьшающийся Колобок наглядно иллюстрировал фазы лунного цикла.

В любом случае, у нашего Колобка точно есть множество иностранных собратьев. Данный сюжет о сбежавшем хлебобулочном изделии, которое по дороге встречает множество действующих лиц, но находит обычно конец в зубах у лисы или свиньи существует во многих странах: Пряничный мальчик и Джонни-Пирог (США), Лепешечка (Шотландия), Блин (Норвегия), Толстый, жирный блин (Германия) и многие другие. Так что этот персонаж является любимым во всем мире.

Поищу что нибудь интересное про другие классические русские народные сказки

Это копия статьи, находящейся по адресу https://masterokblog.ru/?p=51115.