Сыновья мельника и аждаха

(Аварская сказка)

Жил-был мельник. Воды возле его мельницы было вдоволь, своё дело он знал хорошо, и борода его всегда была покрыта мучной пылью. Когда мельник умер, два его старших сына захотели делить наследство. Как ни уговаривал их младший сын работать сообща, они не соглашались. Начали делёж.

— К чему мне вечно ходить с запыленной бородой, — сказал старший брат и выбрал себе канаву мельницы.

— Я тоже всегда вспоминаю отца с запыленной бородой, — откажусь-ка и я от такой жизни, — подумал средний брат и выбрал себе крышу мельницы.

— Ну что ж, — сказал младший брат, — пусть будет борода в пыли, лишь бы желудок знал муку, — и взял себе то, что осталось — старый, хорошо поработавший на своём веку жернов.

Старший брат лежал себе на траве возле канавы, средний грелся на солнышке на крыше мельницы, а младший работал в тени и пыли у жернова, и все, кто приходил на мельницу, оставляли ему немного муки.

Догадался старший брат, что он поступил как глупец, и со стыда решил уйти из родного селения. Шёл он, шёл и очутился, наконец, в сыром темном ущелье. В глубине ущелья у родника лежал аждаха.

— Прохладной тебе воды, аждаха, — испугался сын мельника.

— Если бы не доброе пожелание, проглотил бы я тебя, — сказал аждаха.

— И на том спасибо, — ответил сын мельника.

— Послушай, храбрец, а не знаешь ли ты сказки или песни? — спросил аждаха.

— Нет, — отвечает сын мельника, — не знаю.

— А ведь люди, не знающие сказок и песен, — это добыча зверей, — сказал аждаха и одним махом проглотил сына мельника.

Второму сыну мельника надоело лежать на крыше мельницы, он тоже догадался, что был глупцом, и, как старший брат, ушел из селения и попал в брюхо аждахи.

Младший сын мельника, почуяв недоброе, не мог спокойно сидеть дома. Он отвел воду, остановил мельницу и отправился искать братьев.

Попав в ущелье, сын мельника увидел родник, захотел перепрыгнуть через него и очутился на спине аждахи.

— Прохладной тебе воды, аждаха, — не растерялся сын мельника.

— Если бы не доброе пожелание, проглотил бы я тебя, — ответил аждаха и спросил: — А знаешь ли ты песню или сказку?

— Как же не знать, — говорит сын мельника, — и песню знаю, и сказку, и небылицы, и многое другое, — выбирай, что хочешь.

— Ну, у тебя, наверно, не небылицы, а быль, — сказал аждаха.

— Если быль — проглоти меня, если небылица — молчи, а не то вырежу у тебя ремень со спины.

— Вырезай, — согласился аждаха. — Ври, хоть полную торбу, а я смолчу.

— Ну, что ж, — говорит сын мельника, — давай я расскажу сперва, как я попал к тебе.

Я бы не попал, если бы не мои кобылицы.

В тот год, когда я их пас, вода высохла, и не было травы.

Погнал я кобылиц к реке, вижу, она скована льдом.

Взял я топор, пробил во льду дыру, — вижу — далеко до воды, не достанут кобылицы.

Снял я с плеч свою голову, опорожнил её и напоил всех кобылиц.

Если реке в ногах так холодно, подумал я, то, каково должно быть голове. Пошёл к истокам реки, нарубил кустарника, развёл костёр.

Реке стало теплее, но от моего костра случился пожар, — загорелась река, занялись берега, и все мои кобылицы убежали.

Схватил я топор, гляжу — в руках одно топорище, а обух сгорел.

Вспомнил я о своей голове, вернулся вниз по реке, а в черепе пчёлы.

Тут сын мельника посмотрел на аждаху, тот хотел было что-то спросить, да вовремя вспомнил о своей спине.

— Ну, что ж, — говорит сын мельника, — кобылицы пропали, а жить надо. Надел я череп на шею, поймал носом двух оленей, мясо съел, шкуры на дерево повесил, дерево топорищем срубил, — сделал себе арбу.

Достал из черепа двух пчёл, а они жужжат и спорят между собой — кто больше мёда запасёт. Подрались пчёлы, и я их еле разнял. Этот спор, говорю, можно и без драки решить, — носите мёд, а там видно будет, кто из вас прав. Начали пчёлы носить мёд и нанесли так много, что у меня обе оленьи шкуры наполнились.

Погрузил я шкуры на арбу, в арбу впряг пчёл и поехал.

Вдруг одна из пчёл остановилась, и арба чуть не свернула в пропасть. Поднял я кнут, чтобы стегнуть пчелу, да погонялка задела землю, а кнутовище подбросило меня до самого неба.

Ухватился я за тучу, повис над землей. Туча летит, я за неё руками держусь, вижу — вода. Прыгнул, да очутился у тебя на спине, — там, где мне с тебя ремень рвать.

— Ну, это уж ты врёшь, — сказал аждаха.

— А вру, — так давай скорей ремень со спины. Аждаха видит, что ничего не поделаешь, — подставил спину.

Вырезал у него сын мельника полосу шкуры, сдирает ее до хвоста, видит — в брюхе у аждахи два его брата. Выручил сын мельника братьев и вернулся на мельницу.

С тех пор сыновья мельника стали работать вместе. А аждаха со стыда покинул родник и больше не появлялся в этих местах.

Отправляясь искать приключений на собственную ж… жизнь, не забывайте разучить весь народный фольклор: загадки, пословицы, песни, сказки… А не то станете ужином скучающего монстра. Впрочем, не надейтесь, вас потом все равно спасут, и придется снова идти на работу. Суровая проза жизни.

Жил-был мельник. Мельница его стояла на быстрой речке, дело свое он знал хорошо. И на жизнь свою не жаловался. Борода у него всегда была в мучной пыли. Но вот мельник умер. Осталось три его сына, и пошел между ними спор: что делать с мельницей?

Два старших брата захотели делиться. А младший уговаривал братьев работать сообща. Да разве уговоришь их! Разделили мельницу на три части и дали старшему брату выбрать любую из них.

— Я не хочу работать на мельнице, как наш отец, и вечно ходить с пыльной бородой, — сказал старший. И отказался от мельницы, взял себе запруду.

— И мне не нравится ходить с пыльной бородой, — сказал средний брат и выбрал себе крышу мельницы.

Так и досталась мельница младшему брату.

Старший брат привел в порядок запруду, средний починил крышу, и больше дел у них не было, а младший с утра до ночи работал на мельнице, молол людям зерно.

Но вскоре старшему брату стало лень возиться с запрудой — бросил он лопату и ушел. Шел он, шел. Одну гору миновал, другую позади оставил, и дошел до ущелья, где жил змей ашдага.

— Здравствуй, ашдага! — дрожа от страха, поклонился он.

— Ишь, какой вежливый! — проворчал ашдага. А потом спросил: — Не знаешь ли какой сказки или песни?

— Нет, — ответил старший брат, — не знаю…

— Вот как! Тогда я тебя проглочу, — сказал змей и проглотил старшего брата.

Немного погодя, когда пришло время чинить крышу мельницы, ушел из дому и средний брат, и тоже попал в брюхо ашдаги.

А младший брат был хороший брат. Не мог он спокойно сидеть дома да молоть муку, когда пропали два его брата. Остановил он мельницу, открыл запруду и отправился на поиски.

Пришел он к тому ущелью, где жил ашдага. Увидел, какой у того круглый живот, и сразу понял, куда исчезли его братья.

— Привет тебе, ашдага! — крикнул он. — Такой большой привет, как твое ущелье.

— Ишь, какой любезный! — проворчал ашдага. — А не знаешь ли ты песен или сказок каких?

— Как не знать! Знаю песни, знаю и сказки, знаю и кое-что другое. Хочешь — спою, хочешь — расскажу, хочешь — еще что-нибудь сделаю по твоему приказу.

— Расскажи сначала сказку, — велел ашдага.

— Хорошо! Только ты, ашдага, пока я сказку не кончу, ни «да», ни «нет» не говори. Скажешь — распорю тебе брюхо!

— Согласен! — сказал ашдага.

И мельник начал:

— Было у меня пятьдесят коней. В то лето, как я их пас, стояла сильная жара, и вода всюду высохла. Маленьким жеребятам захотелось пить, и погнал я их к реке. Река была покрыта льдом, жеребята не хотели к ней подходить. Тогда я вынул из-за пояса топор и прорубил прорубь. «Надо бедную речку согреть!», — подумал я. Собрал хвороста, развел костер.

От этого костра случился пожар: загорелись река и камни на берегу.

Испугался я, побежал за своим топором. Смотрю: железный топор сгорел, а деревянное топорище целехонькое лежит…

Ашдага хотел было сказать: «Нет, железо не горит», да промолчал.

— Поехал я дальше, — продолжал мельник свою сказку. — Топорищем нарубил в лесу деревьев и сделал арбу. Потом из этого же топорища застрелил двух оленей. Мясо съел, шкуры на ветвях повесил сушиться.

Прихожу как-то раз посмотреть шкуры, и застаю на том месте двух пчел. Пчелы между собой дерутся, а драка у них пошла от обиды. Заспорили они, кто из них больше меду приносит.

«Ваш спор можно решить без драки, — сказал я. — Летите, несите мед, и я вам скажу, кто из вас прав».

Полетели пчелы наперегонки мед собирать. Через несколько дней обе оленьи шкуры были полны медом.

«Вот видите, — сказал я пчелам, — меду вы насобирали поровну, и спорить, выходит, было не о чем!». Взял и запряг пчел в свою арбу. На арбу взвалил обе шкуры, да и сам сел.

Везли меня пчелы смирно и спокойно, подгонять их не пришлось. Вдруг одна пчела споткнулась. Я взмахнул, было, кнутом, чтоб ее ударить, да, на беду, зацепился кнутовищем за тучу, и подбросило меня высоко в небеса. Ухватился я одной рукой за небесный свод и долго так висел, а потом заметил стог сена на земле и спрыгнул прямо на него…

— Нет, — сказал ашдага, — все это выдумки! Так не бывает.

— Подставляй брюхо, змей! — закричал мельник и одним взмахом кинжала распорол ашдаге живот.

И тотчас выскочили оттуда старшие братья, очень тощие и очень бледные, но очень довольные и очень счастливые. И все трое вернулись на мельницу и стали работать дружно, сообща, не заботясь о том, что бороды у них всегда в мучной пыли.

Скачать сказку в формате

PDF

О пользе сказки, или как сын мельника обманул аждаху. Аварская народная сказка

Жил-был старый мельник с длинной седой бородой. Говорят, что он не был уж очень старым — просто мучная пыль въелась в его бороду и посеребрила ее. Так было или иначе — не знаю, но дни его были сочтены, и, когда аллах призвал его к себе, мельник оставил на земле трех сыновей.

— Давайте, братья, работать сообща,- предложил младший брат,- мельница у нас исправная, и дела пойдут хорошо.

Но старшие братья не согласились и потребовали разделить все наследство, в том числе и мельницу, поровну. Воля старших — закон, и начался дележ.

— Не хочу ходить, как отец, с запыленной бородой,- возгордился самый старший и выбрал себе мельничную канаву.

— Мне тоже надоело дышать мучной пылью,- сказал средний брат и потребовал, чтобы ему отдали крышу мельницы.

А младшему достался жернов.

Старший брат чинил канаву, средний катал на крыше каток, младший следил за жерновом и исправно собирал сах муки с каждого помолотого мешка.

Так прошло некоторое время. Понял старший брат, что прогадал: он следит за канавой, а муку получает младший брат. Не захотел гордец признаться в своей оплошности и молча ушел из дому. Шел он долго, пока не дошел до ущелья у Верхнего Гвалда, где жил аждаха.

— Салам алейкум, аждаха!

— Не уважай я сапам, ободрал бы тебя, как козу, да съел,- проворчал аждаха и спросил: Знаешь ты сказки или песни?

— Нет,- ответил старший сын мельника и покачал головой.

— Такие незнайки — лакомое блюдо,- обрадовался аждаха и мигом проглотил его.

Вскоре и средний сын мельника понял, что совершил глупость: не согласился жить сообща. Не долго думая, он тоже тайно покинул мельницу.

Он дошел до ущелья, где жил аждаха, и разделил судьбу старшего брата.

— Куда исчезли мои братья? — забеспокоился младший и отправился на поиски.

Шел он, шел и, наконец, тоже попал к аждахе.

— Салам алейкум, аждаха! — закричал младший брат.

— Не уважай я твой садам, давно бы проглотил тебя,- ответил аждаха.- А знаешь ли ты сказки или песни?

— Как не знать, ведь я мельник, а они, брат, знают все: и песни, и сказки, и разные небылицы.

— А ну-ка, расскажи мне сказку! — потребовал аждаха.

— Хорошо,- сказал сын мельника.- Только ты не прерывай меня и слушай молча. Если промолвишь хоть слово, я вырежу ремень из твоей спины. А если до конца промолчишь, то можешь меня проглотить.

Аждаха согласился, и сын мельника начал рассказывать.

— Пас я как-то кобылиц. Было так жарко, что повсюду испарилась вода. Погнал я кобылиц на водопой, а река успела уже замерзнуть. Не идут никак кобылицы к реке. Схватил я тогда топор, разбил лед и сделал прорубь. Опять кобылицы не идут. Оторвал я свою голову да черепом напоил всех кобылиц. Подумал я: если река так сильно замерзла, то какой холод должен быть в ее истоках. Пошел я вверх по реке и разложил небольшой костер. Вдруг вспыхнул пожар — это начала гореть река. Испугался я, как бы огонь не добрался до моего черепа и топора, и побежал обратно. Смотрю, сгорело все, кроме топорища и черепа.

Аждаха заерзал и хотел, было сказать что-то, но вспомнил об условии и промолчал.

— Положил я череп на свое место и пошел дальше. В Заибе топорищем срубил деревья и сделал арбу. Пошел на охоту, вижу: олени. Швырнул топорище и двоих убил. Мясо их съел, а шкуры повесил на ветки.

Аждаха хотел, было открыть рот, но удержался.

— Однажды увидел я двух дерущихся пчел. «Чего вы не поделили?» — спросил я их. «Эта нахалка утверждает, что несет больше меду, чем я»,- ответила одна из пчел и начала бить другую. Я их разнял и предложил носить мед для меня. Кто больше принесет, тот и окажется прав. Через несколько дней обе оленьи шкуры были доверху наполнены медом. Впряг я пчел в арбу, нагрузил на них шкуры с медом и поехал домой. Одна пчела стала отставать, и я ударил ее палкой. Одним концом палка задела землю, а другим подбросила меня в небеса. Схватился я руками за край неба и повис над землей. Долго я так висел, болтая ногами, наконец, увидел стог сена да прыгнул в него.

Не выдержал аждаха и крикнул:

— Ну и болтун же ты!

— Ах, так!- воскликнул сын мельника.- Подставляй-ка спину.

Стал он сдирать ремень со спины аждахи и, как только дошел до шеи, пырнул его ножом. Тут выскочили оба его брата. Все трое братьев пошли домой, и стали жить вместе и дружно работать на отцовской мельнице.

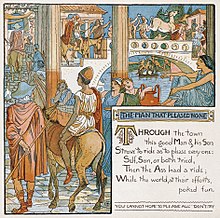

Walter Crane’s composite illustration of all the events in the tale for the limerick retelling of the fables, Baby’s Own Aesop

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

The miller, his son and the donkey is a widely dispersed fable, number 721 in the Perry Index and number 1215 in the Aarne–Thompson classification systems of folklore narratives. Though it may have ancient analogues, the earliest extant version is in the work of the 13th-century Arab writer Ibn Said. There are many eastern versions of the tale and in Europe it was included in a number of Mediaeval collections. Since then it has been frequently included in collections of Aesop’s fables as well as the influential Fables of Jean de la Fontaine.

The fable[edit]

In this fable a man and his son are accompanied by their donkey and meet constant criticism from passers-by of the way it is used or treated by them. The story’s purpose is to show that everyone has their own opinion and there is no way one can satisfy all. There are four or five different elements to the story that are ordered differently according to version. When both walk beside the donkey they are criticised for not riding it. When the father rides, he is blamed for making his young son walk; when the son rides, he is blamed for leaving his elderly father on foot. When both ride, they are berated for overburdening their beast. In later versions the father then exclaims that the only option left is to carry the donkey on his back; in others he does so, or father and son tie the donkey to a pole which they carry on their shoulders. This action causes general mirth and has an unhappy outcome, resulting in the donkey’s death through one cause or another.[1]

History[edit]

Although there is no ancient source for the tale, there may be some link with a dialogue in Aristophanes’ The Frogs,[2] produced in 405 BC. Dionysos is talking to his slave Xanthias, who is riding on a donkey but also carrying a burden himself. Xanthias says the donkey is no help with that weight on his shoulders. «All right, then,» answers Dionysos, «Since you claim the donkey’s useless to you, why not take your turn and carry it?»

Eastern[edit]

The oldest documented occurrence of the actual story is in the work of the historian, geographer and poet Ibn Said (1213–1286), born and educated in Al-Andalus.[3]

There are many versions of the tale in the East. It occurs in the Forty Vezirs[4] translated from Arabic into Turkish by Sheykh Zada in the early 17th century, summarised as:

-

-

- An old gardener, having mounted his son upon an ass, is going to his garden, when he is met by certain persons who jeer at him; he then makes the boy get down and mounts himself, when certain others jeer at him; next he makes the boy get up before, and then behind him, always with the same result; at length both go on foot, and thus reach the garden.

-

The story occurs in the Mulla Nasreddin corpus,[4][5] where it is the Mulla and his son who are subject to the advice and comments of passers-by. After the experience is over, the Mulla advises his son:

-

-

- «If you ever should come into the possession of a donkey, never trim its tail in the presence of other people. Some will say that you have cut off too much, and others that you have cut off too little. If you want to please everyone, in the end your donkey will have no tail at all.»

-

Many Nasreddin tales are also told of Goha in the Arab world, and sure enough, Goha features in a similar story, popular as a subject for the patchwork story cloths of the tentmakers of the Street of Tentmakers (Sharia al Khiyamiya) in Cairo.[6] The story is framed as a deliberate lesson on the part of the father. As Sarah Gauch comments in The adventures of Goha, the Wise Fool,[7] a book illustrated with the tentmakers’ creations, «every tentmaker has a Goha… but whatever the Goha, it seems the favourite story is the tale ‘Goha Gives His Son a Lesson About Life’.»

European[edit]

In Mediaeval Europe it is found from the 13th century on in collections of parables created for inclusion in sermons, of which Jacques de Vitry’s Tabula exemplorum is the earliest.[8] Among collections of fables in European tongues, it makes its earliest appearance in the Castilian of Don Juan Manuel. Titled «What happened to a good Man and his Son, leading a beast to market» (story 23), it is included in his Tales of Count Lucanor (1335).[9] Here it is the son who is so infirm of will that he is guided by the criticisms of others along the road until the father expostulates with him that they have run out of alternatives. The moral given is:

-

-

- In thy chosen life’s adventures, stedfastly pursue the cause,

- Neither moved by critic’s censure, nor the multitude’s applause.

-

In this version the episode of the two carrying the ass is absent, but it appears in Poggio Bracciolini’s Facetiae (1450), where the story is related as one that a papal secretary has heard and seen depicted in Germany. The miller and his son are on the way to sell the ass at market but finally the father is so frustrated by the constant criticism that he throws the ass into the river.[10] The same story is told among the «100 Fables» (Fabulae Centum) of Gabriele Faerno (1564)[11] and as the opening poem in Giovanni Maria Verdizotti’s Cento favole morali (1570).[12] It also appeared in English in Merry Tales and Quick Answers or Shakespeare’s Jest Book (c.1530) with the same ending of the old man throwing the ass into the water.[13]

A slightly later version by the German meistersinger Hans Sachs was created as a broadsheet in 1531.[14] In his retelling a man is asked by his son why they are living secluded in the woods and replies that it is because there is no pleasing anyone in the world. When the son wishes to test this, they set off with their ass and meet criticism whatever they do. Finally they beat the ass to death, are criticised for that too and retreat back into the forest. In drawing the lesson that one should stick to one’s decisions despite what the world says, Sachs refers to the story as an ‘old fable’, although it is obviously not the one with which Poggio’s fellow secretary was acquainted. The Latin version created in Germany by Joachim Camerarius under the title Asinus Vulgi («The public ass») follows the standard story with the single variation that father and son throw the ass over a bridge when they reach it. It is this version too that the Dane Niels Heldvad (1563-1634) used for his translation of the fable.[15]

When Jean de La Fontaine included the tale in his work (Fables III.1, 1668), he related that it had been told by the poet François de Malherbe to his indecisive disciple Honorat de Bueil, seigneur de Racan. The order of the episodes are radically altered, however, and the story begins with the father and son carrying the ass between them so that it will arrive fresh for sale at market. The laughter of bystanders causes him to set it free and subsequent remarks have them changing places until the miller loses patience and decides he will only suit himself in future, for «Doubt not but tongues will have their talk» whatever the circumstances.[16] Earlier on he had reflected that ‘He’s mad who hopes to please the whole world and his brother’. Robert Dodsley draws the same conclusion in his version of 1764: ‘there cannot be a more fruitless attempt than to endeavour to please all mankind’,[17] a sentiment shortened by later authors to ‘there’s no pleasing everyone’. Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea had also made a close translation of the poem, published in 1713.[18]

The applied and decorative arts[edit]

The fable has been illustrated in a number of connections, including on a 1960 Hungarian postage stamp. In around 1800, a composite version of the episodes in the tale appeared as a design for printed cotton fabric in France[19] and in 1817 Hippolyte Lecomte designed a lithograph of the fable suitable to be displayed in people’s homes. Later in the 19th century it was the subject of cards issued by the Liebig meat extract company[20] and Guérin Boutron chocolates.[21] An educational postcard was also issued with the text on the back.[22] Elsewhere, the American Encaustic Tiling Company of Zanesville, Ohio, produced in 1890 a series of printed decal tiles taken directly from the original plates of Walter Crane’s Baby’s Own Aesop. The fable was one of these and featured a composite design of its episodes.

At the start of the 18th century, French artist Claude Gillot produced a coloured drawing of father and son riding side by side on the donkey.[23] In 1835 it is recorded that the French Baron Bastien Felix Feuillet de Conches, a collector and great enthusiast of La Fontaine’s fables, got a colleague to commission a miniature of this and other fables from the Punjabi court painter Imam Bakhsh Lahori.[24] The composite design shows the group positioned sideways along a street of handsome Indian buildings.[25] It is now on exhibition at the Musée Jean de La Fontaine at Château-Thierry, as well as Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot’s oil painting of the father riding through the town with the son holding onto the bridle.[26] Other minor artists who painted the subject were Jules Salles-Wagner (1814–1900),[27] Jules-Joseph Meynier (1826–1903)[28] and Émile Louis Foubert (1848–1911).[29]

Some artists painted more than one version of episodes from the fable. One was Honoré Daumier, whose painting of 1849/50 is now in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.[30] This shows a group of three women turning back to mock the miller and son as they cross the end of the street; but another version has them watched by a woman and her children as they take the road round the edge of the town.[31] Another such artist was the American Symbolist painter Elihu Vedder, whose nine scenes from the story (dating from 1867/8) are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and follow the donkey’s course through an Italian hill town until it topples over a bridge into a ravine.[32][33] European Symbolist painters who treated the subject include the French Gustave Moreau, who made it part of a set of watercolours dedicated to La Fontaine’s fables,[34] and the Swiss Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918).[35] In the 20th century there has been an etching by Marc Chagall[36] and a coloured woodcut by André Planson (1898–1981).[37]

Notes[edit]

- ^ There is a consideration of European variants up to the 14th century in the notes to Nicole Bozon’s Contes Moralisés, ed. Lucy Toulmin Smith and Paul Mayer, Paris 1889, pp.284-7; available online

- ^ Hansen, William (2002). Ariadne’s thread : a guide to international tales found in classical literature (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8014-3670-3.

Dionysos, Xanthias, and the donkey.

- ^ Ulrich Marzolph; Richard van Leeuwen; Hassan Wassouf (2004). «The Gardener, His Son and the Donkey». The Arabian nights encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO Ltd. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-57607-204-2.

- ^ a b «The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey, Folktales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 1215 translated and/or edited by D. L. Ashliman». Pitt.edu. 2009-01-28. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ An illustrated children’s version exists in French:

- ^ «Postcards from Cairo: Goha and the Donkey Walk». jennybowker.blogspot.com.

- ^ Johnson-Davies, Denys; illustrator El Saed Amed, Hany (2005). The adventures of Goha, the Wise Fool. New York: Philomel Books. ISBN 978-0-399-24222-9.

- ^ There is a consideration of the fable’s pedigree from the 13th-17th century by Bengt Holbek in Dansker Studier 1964, pp.32-53; available online

- ^ Manuel, Juan (1335). Count Lucanor; or The Fifty Pleasant Stories Of Patronio.

- ^ The Facetiae in a new translation by Bernhardt J. Hurwood, London 1968, Tale 99, pp.93-4

- ^ Fable 100: Pater, filius et asinus; available in the 1753 edition with Charles Perrault’s French translation online, p.234ff

- ^ Verdizotti, Giovanni Mario (1599). Available on Google Books. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ Tale 59, pp.62-4; available in the 1831 reprint online

- ^ Sachs, Hans (1879). «Spruchgedichte 35 (Der waldbruder mit dem esel)». Ausgewählte poetische Werke. Leipzig.

- ^ Dansker Studier 1964, pp.24-7; available online, PDF

- ^ «An English version online». Oaks.nvg.org. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ Select fables of Esop and other fabulists, part 2.1, pp.65-6 available on Google Books

- ^ Miscellany Poems, p.218

- ^ «This is one episode». Linge-de-berry.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «A set of six». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/image/joconde/0479/m078402_0002733_p.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ http://environnement.ecole.free.fr/images3/le%20meunier%20son%20fils%20et%20l%20ane.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ «An online reproduction». Chapitre.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «The Sunday Tribune — Spectrum». Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ http://www.la-fontaine-ch-thierry.net/images/meunfils.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/image/joconde/0377/m078486_0001542_p.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ «The painting is in Grenoble Museum». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ His painting was exhibited at the 1868 Salon and a small official photograph was taken of it and others purchased by the state at the time

- ^ The painting was exhibited in 1906 and photographed then

- ^ «Honore Daumier. The Miller, His Son and the Donkey (Le Meunier, son fils et l’ane) — Olga’s Gallery». Abcgallery.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «Le Meunier, son filset l, ‘ βne — Honorι Daumier et toutes les images aux couleurs similaires». Repro-tableaux.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «Elihu Vedder — The Fable of the Miller, His Son, and the Donkey — The Metropolitan Museum of Art». metmuseum.org.

- ^ «The Fable of the Miller, His Son and the Donkey No. 1». elihuvedder.org.

- ^ «On display at the Musée Gustave Moreau». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «An oil painting at Geneva’s Musée d’Art et d’Histoire». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «The Miller, his Son and the Donkey. From the Fables of La Fontaine». Marcchagallprints.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «André Planson (1898-1981), litho, Le meunier, son fils et l’âne, illustratie bij fabel boek III, nr. 1, uit: La Fontaine, 20 Fables, Monaco, 1961, afm. 32 x 22 cm». Venduehuis Dickhaut Maastricht. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

External links[edit]

Media related to The miller, his son and the donkey at Wikimedia Commons

- wikisource:The Miller, His Son, and Their Ass, the Aesop’s fable translated by George Fyler Townsend (1887) from Three Hundred Æsop’s Fables

- The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey, Folktales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 1215 translated and/or edited by D. L. Ashliman

- illustrations of the fable, Pater, Filius, et Asinus, on laurakgibbs photostream on flickr

Walter Crane’s composite illustration of all the events in the tale for the limerick retelling of the fables, Baby’s Own Aesop

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

The miller, his son and the donkey is a widely dispersed fable, number 721 in the Perry Index and number 1215 in the Aarne–Thompson classification systems of folklore narratives. Though it may have ancient analogues, the earliest extant version is in the work of the 13th-century Arab writer Ibn Said. There are many eastern versions of the tale and in Europe it was included in a number of Mediaeval collections. Since then it has been frequently included in collections of Aesop’s fables as well as the influential Fables of Jean de la Fontaine.

The fable[edit]

In this fable a man and his son are accompanied by their donkey and meet constant criticism from passers-by of the way it is used or treated by them. The story’s purpose is to show that everyone has their own opinion and there is no way one can satisfy all. There are four or five different elements to the story that are ordered differently according to version. When both walk beside the donkey they are criticised for not riding it. When the father rides, he is blamed for making his young son walk; when the son rides, he is blamed for leaving his elderly father on foot. When both ride, they are berated for overburdening their beast. In later versions the father then exclaims that the only option left is to carry the donkey on his back; in others he does so, or father and son tie the donkey to a pole which they carry on their shoulders. This action causes general mirth and has an unhappy outcome, resulting in the donkey’s death through one cause or another.[1]

History[edit]

Although there is no ancient source for the tale, there may be some link with a dialogue in Aristophanes’ The Frogs,[2] produced in 405 BC. Dionysos is talking to his slave Xanthias, who is riding on a donkey but also carrying a burden himself. Xanthias says the donkey is no help with that weight on his shoulders. «All right, then,» answers Dionysos, «Since you claim the donkey’s useless to you, why not take your turn and carry it?»

Eastern[edit]

The oldest documented occurrence of the actual story is in the work of the historian, geographer and poet Ibn Said (1213–1286), born and educated in Al-Andalus.[3]

There are many versions of the tale in the East. It occurs in the Forty Vezirs[4] translated from Arabic into Turkish by Sheykh Zada in the early 17th century, summarised as:

-

-

- An old gardener, having mounted his son upon an ass, is going to his garden, when he is met by certain persons who jeer at him; he then makes the boy get down and mounts himself, when certain others jeer at him; next he makes the boy get up before, and then behind him, always with the same result; at length both go on foot, and thus reach the garden.

-

The story occurs in the Mulla Nasreddin corpus,[4][5] where it is the Mulla and his son who are subject to the advice and comments of passers-by. After the experience is over, the Mulla advises his son:

-

-

- «If you ever should come into the possession of a donkey, never trim its tail in the presence of other people. Some will say that you have cut off too much, and others that you have cut off too little. If you want to please everyone, in the end your donkey will have no tail at all.»

-

Many Nasreddin tales are also told of Goha in the Arab world, and sure enough, Goha features in a similar story, popular as a subject for the patchwork story cloths of the tentmakers of the Street of Tentmakers (Sharia al Khiyamiya) in Cairo.[6] The story is framed as a deliberate lesson on the part of the father. As Sarah Gauch comments in The adventures of Goha, the Wise Fool,[7] a book illustrated with the tentmakers’ creations, «every tentmaker has a Goha… but whatever the Goha, it seems the favourite story is the tale ‘Goha Gives His Son a Lesson About Life’.»

European[edit]

In Mediaeval Europe it is found from the 13th century on in collections of parables created for inclusion in sermons, of which Jacques de Vitry’s Tabula exemplorum is the earliest.[8] Among collections of fables in European tongues, it makes its earliest appearance in the Castilian of Don Juan Manuel. Titled «What happened to a good Man and his Son, leading a beast to market» (story 23), it is included in his Tales of Count Lucanor (1335).[9] Here it is the son who is so infirm of will that he is guided by the criticisms of others along the road until the father expostulates with him that they have run out of alternatives. The moral given is:

-

-

- In thy chosen life’s adventures, stedfastly pursue the cause,

- Neither moved by critic’s censure, nor the multitude’s applause.

-

In this version the episode of the two carrying the ass is absent, but it appears in Poggio Bracciolini’s Facetiae (1450), where the story is related as one that a papal secretary has heard and seen depicted in Germany. The miller and his son are on the way to sell the ass at market but finally the father is so frustrated by the constant criticism that he throws the ass into the river.[10] The same story is told among the «100 Fables» (Fabulae Centum) of Gabriele Faerno (1564)[11] and as the opening poem in Giovanni Maria Verdizotti’s Cento favole morali (1570).[12] It also appeared in English in Merry Tales and Quick Answers or Shakespeare’s Jest Book (c.1530) with the same ending of the old man throwing the ass into the water.[13]

A slightly later version by the German meistersinger Hans Sachs was created as a broadsheet in 1531.[14] In his retelling a man is asked by his son why they are living secluded in the woods and replies that it is because there is no pleasing anyone in the world. When the son wishes to test this, they set off with their ass and meet criticism whatever they do. Finally they beat the ass to death, are criticised for that too and retreat back into the forest. In drawing the lesson that one should stick to one’s decisions despite what the world says, Sachs refers to the story as an ‘old fable’, although it is obviously not the one with which Poggio’s fellow secretary was acquainted. The Latin version created in Germany by Joachim Camerarius under the title Asinus Vulgi («The public ass») follows the standard story with the single variation that father and son throw the ass over a bridge when they reach it. It is this version too that the Dane Niels Heldvad (1563-1634) used for his translation of the fable.[15]

When Jean de La Fontaine included the tale in his work (Fables III.1, 1668), he related that it had been told by the poet François de Malherbe to his indecisive disciple Honorat de Bueil, seigneur de Racan. The order of the episodes are radically altered, however, and the story begins with the father and son carrying the ass between them so that it will arrive fresh for sale at market. The laughter of bystanders causes him to set it free and subsequent remarks have them changing places until the miller loses patience and decides he will only suit himself in future, for «Doubt not but tongues will have their talk» whatever the circumstances.[16] Earlier on he had reflected that ‘He’s mad who hopes to please the whole world and his brother’. Robert Dodsley draws the same conclusion in his version of 1764: ‘there cannot be a more fruitless attempt than to endeavour to please all mankind’,[17] a sentiment shortened by later authors to ‘there’s no pleasing everyone’. Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea had also made a close translation of the poem, published in 1713.[18]

The applied and decorative arts[edit]

The fable has been illustrated in a number of connections, including on a 1960 Hungarian postage stamp. In around 1800, a composite version of the episodes in the tale appeared as a design for printed cotton fabric in France[19] and in 1817 Hippolyte Lecomte designed a lithograph of the fable suitable to be displayed in people’s homes. Later in the 19th century it was the subject of cards issued by the Liebig meat extract company[20] and Guérin Boutron chocolates.[21] An educational postcard was also issued with the text on the back.[22] Elsewhere, the American Encaustic Tiling Company of Zanesville, Ohio, produced in 1890 a series of printed decal tiles taken directly from the original plates of Walter Crane’s Baby’s Own Aesop. The fable was one of these and featured a composite design of its episodes.

At the start of the 18th century, French artist Claude Gillot produced a coloured drawing of father and son riding side by side on the donkey.[23] In 1835 it is recorded that the French Baron Bastien Felix Feuillet de Conches, a collector and great enthusiast of La Fontaine’s fables, got a colleague to commission a miniature of this and other fables from the Punjabi court painter Imam Bakhsh Lahori.[24] The composite design shows the group positioned sideways along a street of handsome Indian buildings.[25] It is now on exhibition at the Musée Jean de La Fontaine at Château-Thierry, as well as Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot’s oil painting of the father riding through the town with the son holding onto the bridle.[26] Other minor artists who painted the subject were Jules Salles-Wagner (1814–1900),[27] Jules-Joseph Meynier (1826–1903)[28] and Émile Louis Foubert (1848–1911).[29]

Some artists painted more than one version of episodes from the fable. One was Honoré Daumier, whose painting of 1849/50 is now in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.[30] This shows a group of three women turning back to mock the miller and son as they cross the end of the street; but another version has them watched by a woman and her children as they take the road round the edge of the town.[31] Another such artist was the American Symbolist painter Elihu Vedder, whose nine scenes from the story (dating from 1867/8) are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and follow the donkey’s course through an Italian hill town until it topples over a bridge into a ravine.[32][33] European Symbolist painters who treated the subject include the French Gustave Moreau, who made it part of a set of watercolours dedicated to La Fontaine’s fables,[34] and the Swiss Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918).[35] In the 20th century there has been an etching by Marc Chagall[36] and a coloured woodcut by André Planson (1898–1981).[37]

Notes[edit]

- ^ There is a consideration of European variants up to the 14th century in the notes to Nicole Bozon’s Contes Moralisés, ed. Lucy Toulmin Smith and Paul Mayer, Paris 1889, pp.284-7; available online

- ^ Hansen, William (2002). Ariadne’s thread : a guide to international tales found in classical literature (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8014-3670-3.

Dionysos, Xanthias, and the donkey.

- ^ Ulrich Marzolph; Richard van Leeuwen; Hassan Wassouf (2004). «The Gardener, His Son and the Donkey». The Arabian nights encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO Ltd. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-57607-204-2.

- ^ a b «The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey, Folktales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 1215 translated and/or edited by D. L. Ashliman». Pitt.edu. 2009-01-28. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ An illustrated children’s version exists in French:

- ^ «Postcards from Cairo: Goha and the Donkey Walk». jennybowker.blogspot.com.

- ^ Johnson-Davies, Denys; illustrator El Saed Amed, Hany (2005). The adventures of Goha, the Wise Fool. New York: Philomel Books. ISBN 978-0-399-24222-9.

- ^ There is a consideration of the fable’s pedigree from the 13th-17th century by Bengt Holbek in Dansker Studier 1964, pp.32-53; available online

- ^ Manuel, Juan (1335). Count Lucanor; or The Fifty Pleasant Stories Of Patronio.

- ^ The Facetiae in a new translation by Bernhardt J. Hurwood, London 1968, Tale 99, pp.93-4

- ^ Fable 100: Pater, filius et asinus; available in the 1753 edition with Charles Perrault’s French translation online, p.234ff

- ^ Verdizotti, Giovanni Mario (1599). Available on Google Books. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ Tale 59, pp.62-4; available in the 1831 reprint online

- ^ Sachs, Hans (1879). «Spruchgedichte 35 (Der waldbruder mit dem esel)». Ausgewählte poetische Werke. Leipzig.

- ^ Dansker Studier 1964, pp.24-7; available online, PDF

- ^ «An English version online». Oaks.nvg.org. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ Select fables of Esop and other fabulists, part 2.1, pp.65-6 available on Google Books

- ^ Miscellany Poems, p.218

- ^ «This is one episode». Linge-de-berry.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «A set of six». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/image/joconde/0479/m078402_0002733_p.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ http://environnement.ecole.free.fr/images3/le%20meunier%20son%20fils%20et%20l%20ane.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ «An online reproduction». Chapitre.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «The Sunday Tribune — Spectrum». Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ http://www.la-fontaine-ch-thierry.net/images/meunfils.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/image/joconde/0377/m078486_0001542_p.jpg[bare URL image file]

- ^ «The painting is in Grenoble Museum». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ His painting was exhibited at the 1868 Salon and a small official photograph was taken of it and others purchased by the state at the time

- ^ The painting was exhibited in 1906 and photographed then

- ^ «Honore Daumier. The Miller, His Son and the Donkey (Le Meunier, son fils et l’ane) — Olga’s Gallery». Abcgallery.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «Le Meunier, son filset l, ‘ βne — Honorι Daumier et toutes les images aux couleurs similaires». Repro-tableaux.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «Elihu Vedder — The Fable of the Miller, His Son, and the Donkey — The Metropolitan Museum of Art». metmuseum.org.

- ^ «The Fable of the Miller, His Son and the Donkey No. 1». elihuvedder.org.

- ^ «On display at the Musée Gustave Moreau». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «An oil painting at Geneva’s Musée d’Art et d’Histoire». Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «The Miller, his Son and the Donkey. From the Fables of La Fontaine». Marcchagallprints.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ «André Planson (1898-1981), litho, Le meunier, son fils et l’âne, illustratie bij fabel boek III, nr. 1, uit: La Fontaine, 20 Fables, Monaco, 1961, afm. 32 x 22 cm». Venduehuis Dickhaut Maastricht. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

External links[edit]

Media related to The miller, his son and the donkey at Wikimedia Commons

- wikisource:The Miller, His Son, and Their Ass, the Aesop’s fable translated by George Fyler Townsend (1887) from Three Hundred Æsop’s Fables

- The Man, the Boy, and the Donkey, Folktales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 1215 translated and/or edited by D. L. Ashliman

- illustrations of the fable, Pater, Filius, et Asinus, on laurakgibbs photostream on flickr