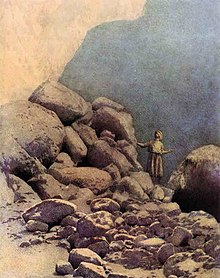

Cassim in the cave, by Maxfield Parrish, 1909, from the story «Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves» |

|

| Language | Arabic |

|---|---|

| Genre | Frame story, folk tales |

| Set in | Middle Ages |

| Text | One Thousand and One Nights at Wikisource |

One Thousand and One Nights (Arabic: أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, ʾAlf Laylah wa-Laylah)[1] is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English-language edition (c. 1706–1721), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment.[2]

The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central and South Asia, and North Africa. Some tales trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Egyptian, Sanskrit, Persian, and Mesopotamian literature.[3] Many tales were originally folk stories from the Abbasid and Mamluk eras, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hezār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales), which in turn relied partly on Indian elements.[4]

Common to all the editions of the Nights is the framing device of the story of the ruler Shahryār being narrated the tales by his wife Scheherazade, with one tale told over each night of storytelling. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while some are self-contained. Some editions contain only a few hundred stories, while others include 1001 or more. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.

Some of the stories commonly associated with the Arabian Nights—particularly «Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp» and «Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves»—were not part of the collection in its original Arabic versions but were added to the collection by Antoine Galland after he heard them from the Syrian[5][6] Maronite Christian storyteller Hanna Diab on Diab’s visit to Paris.[7] Other stories, such as «The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor», had an independent existence before being added to the collection.

Synopsis[edit]

The main frame story concerns Shahryār whom the narrator calls a «Sasanian king» ruling in «India and China.»[8] Shahryār is shocked to learn that his brother’s wife is unfaithful. Discovering that his own wife’s infidelity has been even more flagrant, he has her killed. In his bitterness and grief, he decides that all women are the same. Shahryār begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to dishonor him.

Eventually the Vizier (Wazir), whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it. The king, curious about how the story ends, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins another one, and the king, eager to hear the conclusion of that tale as well, postpones her execution once again. This goes on for one thousand and one nights, hence the name.

The tales vary widely: they include historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems, burlesques, and various forms of erotica. Numerous stories depict jinn, ghouls, ape people,[9] sorcerers, magicians, and legendary places, which are often intermingled with real people and geography, not always rationally. Common protagonists include the historical Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, his Grand Vizier, Jafar al-Barmaki, and the famous poet Abu Nuwas, despite the fact that these figures lived some 200 years after the fall of the Sassanid Empire, in which the frame tale of Scheherazade is set. Sometimes a character in Scheherazade’s tale will begin telling other characters a story of his own, and that story may have another one told within it, resulting in a richly layered narrative texture.

Versions differ, at least in detail, as to final endings (in some Scheherazade asks for a pardon, in some the king sees their children and decides not to execute his wife, in some other things happen that make the king distracted) but they all end with the king giving his wife a pardon and sparing her life.

The narrator’s standards for what constitutes a cliffhanger seem broader than in modern literature. While in many cases a story is cut off with the hero in danger of losing their life or another kind of deep trouble, in some parts of the full text Scheherazade stops her narration in the middle of an exposition of abstract philosophical principles or complex points of Islamic philosophy, and in one case during a detailed description of human anatomy according to Galen—and in all of these cases she turns out to be justified in her belief that the king’s curiosity about the sequel would buy her another day of life.

History: versions and translations[edit]

The history of the Nights is extremely complex and modern scholars have made many attempts to untangle the story of how the collection as it currently exists came about. Robert Irwin summarises their findings:

In the 1880s and 1890s a lot of work was done on the Nights by Zotenberg and others, in the course of which a consensus view of the history of the text emerged. Most scholars agreed that the Nights was a composite work and that the earliest tales in it came from India and Persia. At some time, probably in the early eighth century, these tales were translated into Arabic under the title Alf Layla, or ‘The Thousand Nights’. This collection then formed the basis of The Thousand and One Nights. The original core of stories was quite small. Then, in Iraq in the ninth or tenth century, this original core had Arab stories added to it—among them some tales about the Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Also, perhaps from the tenth century onwards, previously independent sagas and story cycles were added to the compilation […] Then, from the 13th century onwards, a further layer of stories was added in Syria and Egypt, many of these showing a preoccupation with sex, magic or low life. In the early modern period yet more stories were added to the Egyptian collections so as to swell the bulk of the text sufficiently to bring its length up to the full 1,001 nights of storytelling promised by the book’s title.[10]

Possible Indian influence[edit]

Devices found in Sanskrit literature such as frame stories and animal fables are seen by some scholars as lying at the root of the conception of the Nights.[11] The motif of the wise young woman who delays and finally removes an impending danger by telling stories has been traced back to Indian sources.[12] Indian folklore is represented in the Nights by certain animal stories, which reflect influence from ancient Sanskrit fables. The influence of the Panchatantra and Baital Pachisi is particularly notable.[13]

It is possible that the influence of the Panchatantra is via a Sanskrit adaptation called the Tantropakhyana. Only fragments of the original Sanskrit form of the Tantropakhyana survive, but translations or adaptations exist in Tamil,[14] Lao,[15] Thai,[16] and Old Javanese.[17] The frame story follows the broad outline of a concubine telling stories in order to maintain the interest and favour of a king—although the basis of the collection of stories is from the Panchatantra—with its original Indian setting.[18]

The Panchatantra and various tales from Jatakas were first translated into Persian by Borzūya in 570 CE,[19] they were later translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa in 750 CE.[20] The Arabic version was translated into several languages, including Syriac, Greek, Hebrew and Spanish.[21]

Persian prototype: Hezār Afsān[edit]

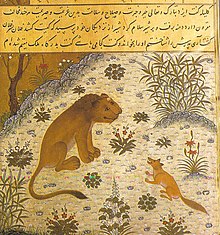

A page from Kelileh va Demneh dated 1429, from Herat, a Persian version of the original ancient Indian Panchatantra – depicts the manipulative jackal-vizier, Dimna, trying to lead his lion-king into war.

The earliest mentions of the Nights refer to it as an Arabic translation from a Persian book, Hezār Afsān (aka Afsaneh or Afsana), meaning ‘The Thousand Stories’. In the tenth century, Ibn al-Nadim compiled a catalogue of books (the «Fihrist») in Baghdad. He noted that the Sassanid kings of Iran enjoyed «evening tales and fables».[22] Al-Nadim then writes about the Persian Hezār Afsān, explaining the frame story it employs: a bloodthirsty king kills off a succession of wives after their wedding night. Eventually one has the intelligence to save herself by telling him a story every evening, leaving each tale unfinished until the next night so that the king will delay her execution.[23]

However, according to al-Nadim, the book contains only 200 stories. He also writes disparagingly of the collection’s literary quality, observing that «it is truly a coarse book, without warmth in the telling».[24] In the same century Al-Masudi also refers to the Hezār Afsān, saying the Arabic translation is called Alf Khurafa (‘A Thousand Entertaining Tales’), but is generally known as Alf Layla (‘A Thousand Nights’). He mentions the characters Shirāzd (Scheherazade) and Dināzād.[25]

No physical evidence of the Hezār Afsān has survived,[11] so its exact relationship with the existing later Arabic versions remains a mystery.[26] Apart from the Scheherazade frame story, several other tales have Persian origins, although it is unclear how they entered the collection.[27] These stories include the cycle of «King Jali’ad and his Wazir Shimas» and «The Ten Wazirs or the History of King Azadbakht and his Son» (derived from the seventh-century Persian Bakhtiyārnāma).[28]

In the 1950s, the Iraqi scholar Safa Khulusi suggested (on internal rather than historical evidence) that the Persian writer Ibn al-Muqaffa’ was responsible for the first Arabic translation of the frame story and some of the Persian stories later incorporated into the Nights. This would place genesis of the collection in the eighth century.[29][30]

Evolving Arabic versions[edit]

In the mid-20th century, the scholar Nabia Abbott found a document with a few lines of an Arabic work with the title The Book of the Tale of a Thousand Nights, dating from the ninth century. This is the earliest known surviving fragment of the Nights.[26] The first reference to the Arabic version under its full title The One Thousand and One Nights appears in Cairo in the 12th century.[32] Professor Dwight Reynolds describes the subsequent transformations of the Arabic version:

Some of the earlier Persian tales may have survived within the Arabic tradition altered such that Arabic Muslim names and new locations were substituted for pre-Islamic Persian ones, but it is also clear that whole cycles of Arabic tales were eventually added to the collection and apparently replaced most of the Persian materials. One such cycle of Arabic tales centres around a small group of historical figures from ninth-century Baghdad, including the caliph Harun al-Rashid (died 809), his vizier Jafar al-Barmaki (d. 803) and the licentious poet Abu Nuwas (d. c. 813). Another cluster is a body of stories from late medieval Cairo in which are mentioned persons and places that date to as late as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[33]

Two main Arabic manuscript traditions of the Nights are known: the Syrian and the Egyptian. The Syrian tradition is primarily represented by the earliest extensive manuscript of the Nights, a fourteenth- or fifteenth-century Syrian manuscript now known as the Galland Manuscript. It and surviving copies of it are much shorter and include fewer tales than the Egyptian tradition. It is represented in print by the so-called Calcutta I (1814–1818) and most notably by the ‘Leiden edition’ (1984).[34][35] The Leiden Edition, prepared by Muhsin Mahdi, is the only critical edition of 1001 Nights to date,[36] believed to be most stylistically faithful representation of medieval Arabic versions currently available.[34][35]

Texts of the Egyptian tradition emerge later and contain many more tales of much more varied content; a much larger number of originally independent tales have been incorporated into the collection over the centuries, most of them after the Galland manuscript was written,[37] and were being included as late as in the 18th and 19th centuries.

All extant substantial versions of both recensions share a small common core of tales:[38]

- The Merchant and the Genie

- The Fisherman and the Genie

- The Porter and the Three Ladies

- The Three Apples

- Nur al-Din Ali and Shams al-Din (and Badr al-Din Hasan)

- Nur al-Din Ali and Anis al-Jalis

- Ali Ibn Bakkar and Shams al-Nahar

The texts of the Syrian recension do not contain much beside that core. It is debated which of the Arabic recensions is more «authentic» and closer to the original: the Egyptian ones have been modified more extensively and more recently, and scholars such as Muhsin Mahdi have suspected that this was caused in part by European demand for a «complete version»; but it appears that this type of modification has been common throughout the history of the collection, and independent tales have always been added to it.[37][39]

Printed Arabic editions[edit]

The first printed Arabic-language edition of the One Thousand and One Nights was published in 1775. It contained an Egyptian version of The Nights known as «ZER» (Zotenberg’s Egyptian Recension) and 200 tales. No copy of this edition survives, but it was the basis for an 1835 edition by Bulaq, published by the Egyptian government.

Arabic manuscript with parts of Arabian Nights, collected by Heinrich Friedrich von Diez, 19th century CE, origin unknown

The Nights were next printed in Arabic in two volumes in Calcutta by the British East India Company in 1814–1818. Each volume contained one hundred tales.

Soon after, the Prussian scholar Christian Maximilian Habicht collaborated with the Tunisian Mordecai ibn al-Najjar to create an edition containing 1001 nights both in the original Arabic and in German translation, initially in a series of eight volumes published in Breslau in 1825–1838. A further four volumes followed in 1842–1843. In addition to the Galland manuscript, Habicht and al-Najjar used what they believed to be a Tunisian manuscript, which was later revealed as a forgery by al-Najjar.[36]

Both the ZER printing and Habicht and al-Najjar’s edition influenced the next printing, a four-volume edition also from Calcutta (known as the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition).[40] This claimed to be based on an older Egyptian manuscript (which has never been found).

A major recent edition, which reverts to the Syrian recension, is a critical edition based on the fourteenth- or fifteenth-century Syrian manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale originally used by Galland.[41] This edition, known as the Leiden text, was compiled in Arabic by Muhsin Mahdi (1984–1994).[42] Mahdi argued that this version is the earliest extant one (a view that is largely accepted today) and that it reflects most closely a «definitive» coherent text ancestral to all others that he believed to have existed during the Mamluk period (a view that remains contentious).[37][43][44] Still, even scholars who deny this version the exclusive status of «the only real Arabian Nights» recognize it as being the best source on the original style and linguistic form of the medieval work.[34][35]

In 1997, a further Arabic edition appeared, containing tales from the Arabian Nights transcribed from a seventeenth-century manuscript in the Egyptian dialect of Arabic.[45]

Modern translations[edit]

Sindbad the sailor and Ali Baba and the forty thieves by William Strang, 1896

The first European version (1704–1717) was translated into French by Antoine Galland[46] from an Arabic text of the Syrian recension and other sources. This 12-volume work,[46] Les Mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français (‘The Thousand and one nights, Arab stories translated into French’), included stories that were not in the original Arabic manuscript. «Aladdin’s Lamp», and «Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves» (as well as several other lesser-known tales) appeared first in Galland’s translation and cannot be found in any of the original manuscripts. He wrote that he heard them from the Christian Maronite storyteller Hanna Diab during Diab’s visit to Paris. Galland’s version of the Nights was immensely popular throughout Europe, and later versions were issued by Galland’s publisher using Galland’s name without his consent.

As scholars were looking for the presumed «complete» and «original» form of the Nights, they naturally turned to the more voluminous texts of the Egyptian recension, which soon came to be viewed as the «standard version». The first translations of this kind, such as that of Edward Lane (1840, 1859), were bowdlerized. Unabridged and unexpurgated translations were made, first by John Payne, under the title The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (1882, nine volumes), and then by Sir Richard Francis Burton, entitled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885, ten volumes) – the latter was, according to some assessments, partially based on the former, leading to charges of plagiarism.[47][48]

In view of the sexual imagery in the source texts (which Burton emphasized even further, especially by adding extensive footnotes and appendices on Oriental sexual mores[48]) and the strict Victorian laws on obscene material, both of these translations were printed as private editions for subscribers only, rather than published in the usual manner. Burton’s original 10 volumes were followed by a further six (seven in the Baghdad Edition and perhaps others) entitled The Supplemental Nights to the Thousand Nights and a Night, which were printed between 1886 and 1888.[46] It has, however, been criticized for its «archaic language and extravagant idiom» and «obsessive focus on sexuality» (and has even been called an «eccentric ego-trip» and a «highly personal reworking of the text»).[48]

Later versions of the Nights include that of the French doctor J. C. Mardrus, issued from 1898 to 1904. It was translated into English by Powys Mathers, and issued in 1923. Like Payne’s and Burton’s texts, it is based on the Egyptian recension and retains the erotic material, indeed expanding on it, but it has been criticized for inaccuracy.[47]

Muhsin Mahdi’s 1984 Leiden edition, based on the Galland Manuscript, was rendered into English by Husain Haddawy (1990).[49] This translation has been praised as «very readable» and «strongly recommended for anyone who wishes to taste the authentic flavour of those tales.»[50] An additional second volume of Arabian nights translated by Haddawy, composed of popular tales not present in the Leiden edition, was published in 1995.[51] Both volumes were the basis for a single-volume reprint of selected tales of Haddawy’s translations.[52]

In 2008 a new English translation was published by Penguin Classics in three volumes. It is translated by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons with introduction and annotations by Robert Irwin. This is the first complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) since Burton’s. It contains, in addition to the standard text of 1001 Nights, the so-called «orphan stories» of Aladdin and Ali Baba as well as an alternative ending to The seventh journey of Sindbad from Antoine Galland’s original French. As the translator himself notes in his preface to the three volumes, «[N]o attempt has been made to superimpose on the translation changes that would be needed to ‘rectify’ … accretions, … repetitions, non sequiturs and confusions that mark the present text,» and the work is a «representation of what is primarily oral literature, appealing to the ear rather than the eye.»[53] The Lyons translation includes all the poetry (in plain prose paraphrase) but does not attempt to reproduce in English the internal rhyming of some prose sections of the original Arabic. Moreover, it streamlines somewhat and has cuts. In this sense it is not, as claimed, a complete translation.

A new English language translation was published in December 2021, the first solely by a female author, Yasmine Seale, which removes earlier sexist and racist references. The new translation includes all the tales from Hanna Diyab and additionally includes stories previously omitted featuring female protagonists, such as tales about Parizade, Pari Banu, and the horror story Sidi Numan.[54]

Timeline[edit]

Arabic manuscript of The Thousand and One Nights dating back to the 14th century

Scholars have assembled a timeline concerning the publication history of The Nights:[55][50][56]

- One of the oldest Arabic manuscript fragments from Syria (a few handwritten pages) dating to the early ninth century. Discovered by scholar Nabia Abbott in 1948, it bears the title Kitab Hadith Alf Layla («The Book of the Tale of the Thousand Nights») and the first few lines of the book in which Dinazad asks Shirazad (Scheherazade) to tell her stories.[33]

- 10th century: Mention of Hezār Afsān in Ibn al-Nadim’s «Fihrist» (Catalogue of books) in Baghdad. He attributes a pre-Islamic Sassanian Persian origin to the collection and refers to the frame story of Scheherazade telling stories over a thousand nights to save her life.[24]

- 10th century: Reference to The Thousand Nights, an Arabic translation of the Persian Hezār Afsān («Thousand Stories»), in Muruj Al-Dhahab (The Meadows of Gold) by Al-Mas’udi.[25]

- 12th century: A document from Cairo refers to a Jewish bookseller lending a copy of The Thousand and One Nights (this is the first appearance of the final form of the title).[32]

- 14th century: Existing Syrian manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (contains about 300 tales).[41]

- 1704: Antoine Galland’s French translation is the first European version of The Nights. Later volumes were introduced using Galland’s name though the stories were written by unknown persons at the behest of the publisher wanting to capitalize on the popularity of the collection.

- c. 1706 – c. 1721: An anonymously translated version in English appears in Europe dubbed the 12-volume «Grub Street» version. This is entitled Arabian Nights’ Entertainments—the first known use of the common English title of the work.[57]

- 1768: first Polish translation, 12 volumes. Based, as many European on the French translation.

- 1775: Egyptian version of The Nights called «ZER» (Hermann Zotenberg’s Egyptian Recension) with 200 tales (no surviving edition exists).

- 1804–1806, 1825: The Austrian polyglot and orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774–1856) translates a subsequently lost manuscript into French between 1804 and 1806. His French translation, which was partially abridged and included Galland’s «orphan stories», has been lost, but its translation into German that was published in 1825 still survives.[58]

- 1814: Calcutta I, the earliest existing Arabic printed version, is published by the British East India Company. A second volume was released in 1818. Both had 100 tales each.

- 1811: Jonathan Scott (1754–1829), an Englishman who learned Arabic and Persian in India, produces an English translation, mostly based on Galland’s French version, supplemented by other sources. Robert Irwin calls it the «first literary translation into English», in contrast to earlier translations from French by «Grub Street hacks».[59]

- Early 19th century: Modern Persian translations of the text are made, variously under the title Alf leile va leile, Hezār-o yek šhab (هزار و یک شب), or, in distorted Arabic, Alf al-leil. One early extant version is that illustrated by Sani ol Molk (1814–1866) for Mohammad Shah Qajar.[60]

- 1825–1838: The Breslau/Habicht edition is published in Arabic in 8 volumes. Christian Maximilian Habicht (born in Breslau, Kingdom of Prussia, 1775) collaborated with the Tunisian Mordecai ibn al-Najjar to create this edition containing 1001 nights. In addition to the Galland manuscript, they used what they believed to be a Tunisian manuscript, which was later revealed as a forgery by al-Najjar.[36] Using versions of The Nights, tales from Al-Najjar, and other stories from unknown origins Habicht published his version in Arabic and German.

- 1842–1843: Four additional volumes by Habicht.

- 1835: Bulaq version: These two volumes, printed by the Egyptian government, are the oldest printed (by a publishing house) version of The Nights in Arabic by a non-European. It is primarily a reprinting of the ZER text.

- 1839–1842: Calcutta II (4 volumes) is published. It claims to be based on an older Egyptian manuscript (which was never found). This version contains many elements and stories from the Habicht edition.

- 1838: Torrens version in English.

- 1838–1840: Edward William Lane publishes an English translation. Notable for its exclusion of content Lane found immoral and for its anthropological notes on Arab customs by Lane.

- 1882–1884: John Payne publishes an English version translated entirely from Calcutta II, adding some tales from Calcutta I and Breslau.

- 1885–1888: Sir Richard Francis Burton publishes an English translation from several sources (largely the same as Payne[47]). His version accentuated the sexuality of the stories vis-à-vis Lane’s bowdlerized translation.

- 1889–1904: J. C. Mardrus publishes a French version using Bulaq and Calcutta II editions.

- 1973: First Polish translation based on the original language edition, but compressed 12 volumes to 9, by PIW.

- 1984: Muhsin Mahdi publishes an Arabic edition based on the oldest Arabic manuscript surviving (based on the oldest surviving Syrian manuscript currently held in the Bibliothèque Nationale).

- 1986–1987: French translation by Arabist René R. Khawam

- 1990: Husain Haddawy publishes an English translation of Mahdi.

- 2008: New Penguin Classics translation (in three volumes) by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons of the Calcutta II edition

Literary themes and techniques[edit]

Illustration of One Thousand and One Nights by Sani ol Molk, Iran, 1853

The One Thousand and One Nights and various tales within it make use of many innovative literary techniques, which the storytellers of the tales rely on for increased drama, suspense, or other emotions.[61] Some of these date back to earlier Persian, Indian and Arabic literature, while others were original to the One Thousand and One Nights.

Frame story[edit]

The One Thousand and One Nights employs an early example of the frame story, or framing device: the character Scheherazade narrates a set of tales (most often fairy tales) to the Sultan Shahriyar over many nights. Many of Scheherazade’s tales are themselves frame stories, such as the Tale of Sinbad the Seaman and Sinbad the Landsman, which is a collection of adventures related by Sinbad the Seaman to Sinbad the Landsman.

In folkloristics, the frame story is classified as ATU 875B “Storytelling Saves a Wife from Death”[62]

Embedded narrative[edit]

Another technique featured in the One Thousand and One Nights is an early example of the «story within a story», or embedded narrative technique: this can be traced back to earlier Persian and Indian storytelling traditions, most notably the Panchatantra of ancient Sanskrit literature. The Nights, however, improved on the Panchatantra in several ways, particularly in the way a story is introduced. In the Panchatantra, stories are introduced as didactic analogies, with the frame story referring to these stories with variants of the phrase «If you’re not careful, that which happened to the louse and the flea will happen to you.» In the Nights, this didactic framework is the least common way of introducing the story: instead, a story is most commonly introduced through subtle means, particularly as an answer to questions raised in a previous tale.[63]

The general story is narrated by an unknown narrator, and in this narration the stories are told by Scheherazade. In most of Scheherazade’s narrations there are also stories narrated, and even in some of these, there are some other stories.[64] This is particularly the case for the «Sinbad the Sailor» story narrated by Scheherazade in the One Thousand and One Nights. Within the «Sinbad the Sailor» story itself, the protagonist Sinbad the Sailor narrates the stories of his seven voyages to Sinbad the Porter. The device is also used to great effect in stories such as «The Three Apples» and «The Seven Viziers». In yet another tale Scheherazade narrates, «The Fisherman and the Jinni», the «Tale of the Wazir and the Sage Duban» is narrated within it, and within that there are three more tales narrated.

Dramatic visualization[edit]

Dramatic visualization is «the representing of an object or character with an abundance of descriptive detail, or the mimetic rendering of gestures and dialogue in such a way as to make a given scene ‘visual’ or imaginatively present to an audience». This technique is used in several tales of the One Thousand and One Nights;[65] an example of this is the tale of «The Three Apples» (see Crime fiction elements below).

Fate and destiny[edit]

A common theme in many Arabian Nights tales is fate and destiny. Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini observed:[66]

every tale in The Thousand and One Nights begins with an ‘appearance of destiny’ which manifests itself through an anomaly, and one anomaly always generates another. So a chain of anomalies is set up. And the more logical, tightly knit, essential this chain is, the more beautiful the tale. By ‘beautiful’ I mean vital, absorbing and exhilarating. The chain of anomalies always tends to lead back to normality. The end of every tale in The One Thousand and One Nights consists of a ‘disappearance’ of destiny, which sinks back to the somnolence of daily life … The protagonist of the stories is in fact destiny itself.

Though invisible, fate may be considered a leading character in the One Thousand and One Nights.[67] The plot devices often used to present this theme are coincidence,[68] reverse causation, and the self-fulfilling prophecy (see Foreshadowing section below).

Foreshadowing[edit]

Sindbad and the Valley of Diamonds, from the Second Voyage.

Early examples of the foreshadowing technique of repetitive designation, now known as «Chekhov’s gun», occur in the One Thousand and One Nights, which contains «repeated references to some character or object which appears insignificant when first mentioned but which reappears later to intrude suddenly in the narrative.»[69] A notable example is in the tale of «The Three Apples» (see Crime fiction elements below).

Another early foreshadowing technique is formal patterning, «the organization of the events, actions and gestures which constitute a narrative and give shape to a story; when done well, formal patterning allows the audience the pleasure of discerning and anticipating the structure of the plot as it unfolds.» This technique is also found in One Thousand and One Nights.[65]

The self-fulfilling prophecy[edit]

Several tales in the One Thousand and One Nights use the self-fulfilling prophecy, as a special form of literary prolepsis, to foreshadow what is going to happen. This literary device dates back to the story of Krishna in ancient Sanskrit literature, and Oedipus or the death of Heracles in the plays of Sophocles. A variation of this device is the self-fulfilling dream, which can be found in Arabic literature (or the dreams of Joseph and his conflicts with his brothers, in the Hebrew Bible).

A notable example is «The Ruined Man who Became Rich Again through a Dream», in which a man is told in his dream to leave his native city of Baghdad and travel to Cairo, where he will discover the whereabouts of some hidden treasure. The man travels there and experiences misfortune, ending up in jail, where he tells his dream to a police officer. The officer mocks the idea of foreboding dreams and tells the protagonist that he himself had a dream about a house with a courtyard and fountain in Baghdad where treasure is buried under the fountain. The man recognizes the place as his own house and, after he is released from jail, he returns home and digs up the treasure. In other words, the foreboding dream not only predicted the future, but the dream was the cause of its prediction coming true. A variant of this story later appears in English folklore as the «Pedlar of Swaffham» and Paulo Coelho’s «The Alchemist»; Jorge Luis Borges’ collection of short stories A Universal History of Infamy featured his translation of this particular story into Spanish, as «The Story Of The Two Dreamers.»[70]

«The Tale of Attaf» depicts another variation of the self-fulfilling prophecy, whereby Harun al-Rashid consults his library (the House of Wisdom), reads a random book, «falls to laughing and weeping and dismisses the faithful vizier Ja’far ibn Yahya from sight. Ja’afar, disturbed and upset flees Baghdad and plunges into a series of adventures in Damascus, involving Attaf and the woman whom Attaf eventually marries.» After returning to Baghdad, Ja’afar reads the same book that caused Harun to laugh and weep, and discovers that it describes his own adventures with Attaf. In other words, it was Harun’s reading of the book that provoked the adventures described in the book to take place. This is an early example of reverse causation.[71]

Near the end of the tale, Attaf is given a death sentence for a crime he did not commit but Harun, knowing the truth from what he has read in the book, prevents this and has Attaf released from prison. In the 12th century, this tale was translated into Latin by Petrus Alphonsi and included in his Disciplina Clericalis,[72] alongside the «Sindibad» story cycle.[73] In the 14th century, a version of «The Tale of Attaf» also appears in the Gesta Romanorum and Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron.[72]

Repetition[edit]

Illustration of One Thousand and One Nights by Sani ol molk, Iran, 1849–1856

Leitwortstil is «the purposeful repetition of words» in a given literary piece that «usually expresses a motif or theme important to the given story.» This device occurs in the One Thousand and One Nights, which binds several tales in a story cycle. The storytellers of the tales relied on this technique «to shape the constituent members of their story cycles into a coherent whole.»[61]

Another technique used in the One Thousand and One Nights is thematic patterning, which is:

[T]he distribution of recurrent thematic concepts and moralistic motifs among the various incidents and frames of a story. In a skillfully crafted tale, thematic patterning may be arranged so as to emphasize the unifying argument or salient idea which disparate events and disparate frames have in common.[65]

Several different variants of the «Cinderella» story, which has its origins in the Egyptian story of Rhodopis, appear in the One Thousand and One Nights, including «The Second Shaykh’s Story», «The Eldest Lady’s Tale» and «Abdallah ibn Fadil and His Brothers», all dealing with the theme of a younger sibling harassed by two jealous elders. In some of these, the siblings are female, while in others they are male. One of the tales, «Judar and His Brethren», departs from the happy endings of previous variants and reworks the plot to give it a tragic ending instead, with the younger brother being poisoned by his elder brothers.[74]

Sexual humour[edit]

The Nights contain many examples of sexual humour. Some of this borders on satire, as in the tale called «Ali with the Large Member» which pokes fun at obsession with penis size.[75][76]

Unreliable narrator[edit]

The literary device of the unreliable narrator was used in several fictional medieval Arabic tales of the One Thousand and One Nights. In one tale, «The Seven Viziers» (also known as «Craft and Malice of Women or The Tale of the King, His Son, His Concubine and the Seven Wazirs»), a courtesan accuses a king’s son of having assaulted her, when in reality she had failed to seduce him (inspired by the Qur’anic/Biblical story of Yusuf/Joseph). Seven viziers attempt to save his life by narrating seven stories to prove the unreliability of women, and the courtesan responds by narrating a story to prove the unreliability of viziers.[77] The unreliable narrator device is also used to generate suspense in «The Three Apples» and humor in «The Hunchback’s Tale» (see Crime fiction elements below).

Genre elements[edit]

Crime fiction[edit]

An example of the murder mystery[78] and suspense thriller genres in the collection, with multiple plot twists[79] and detective fiction elements[80] was «The Three Apples», also known as Hikayat al-sabiyya ‘l-maqtula (‘The Tale of the Murdered Young Woman’).[81]

In this tale, Harun al-Rashid comes to possess a chest, which, when opened, contains the body of a young woman. Harun gives his vizier, Ja’far, three days to find the culprit or be executed. At the end of three days, when Ja’far is about to be executed for his failure, two men come forward, both claiming to be the murderer. As they tell their story it transpires that, although the younger of them, the woman’s husband, was responsible for her death, some of the blame attaches to a slave, who had taken one of the apples mentioned in the title and caused the woman’s murder.

Harun then gives Ja’far three more days to find the guilty slave. When he yet again fails to find the culprit, and bids his family goodbye before his execution, he discovers by chance his daughter has the apple, which she obtained from Ja’far’s own slave, Rayhan. Thus the mystery is solved.

Another Nights tale with crime fiction elements was «The Hunchback’s Tale» story cycle which, unlike «The Three Apples», was more of a suspenseful comedy and courtroom drama rather than a murder mystery or detective fiction. The story is set in a fictional China and begins with a hunchback, the emperor’s favourite comedian, being invited to dinner by a tailor couple. The hunchback accidentally chokes on his food from laughing too hard and the couple, fearful that the emperor will be furious, take his body to a Jewish doctor’s clinic and leave him there. This leads to the next tale in the cycle, the «Tale of the Jewish Doctor», where the doctor accidentally trips over the hunchback’s body, falls down the stairs with him, and finds him dead, leading him to believe that the fall had killed him. The doctor then dumps his body down a chimney, and this leads to yet another tale in the cycle, which continues with twelve tales in total, leading to all the people involved in this incident finding themselves in a courtroom, all making different claims over how the hunchback had died.[82] Crime fiction elements are also present near the end of «The Tale of Attaf» (see Foreshadowing above).

Horror fiction[edit]

Haunting is used as a plot device in gothic fiction and horror fiction, as well as modern paranormal fiction. Legends about haunted houses have long appeared in literature. In particular, the Arabian Nights tale of «Ali the Cairene and the Haunted House in Baghdad» revolves around a house haunted by jinn.[83] The Nights is almost certainly the earliest surviving literature that mentions ghouls, and many of the stories in that collection involve or reference ghouls. A prime example is the story The History of Gherib and His Brother Agib (from Nights vol. 6), in which Gherib, an outcast prince, fights off a family of ravenous Ghouls and then enslaves them and converts them to Islam.[84]

Horror fiction elements are also found in «The City of Brass» tale, which revolves around a ghost town.[85]

The horrific nature of Scheherazade’s situation is magnified in Stephen King’s Misery, in which the protagonist is forced to write a novel to keep his captor from torturing and killing him. The influence of the Nights on modern horror fiction is certainly discernible in the work of H. P. Lovecraft. As a child, he was fascinated by the adventures recounted in the book, and he attributes some of his creations to his love of the 1001 Nights.[86]

Fantasy and science fiction[edit]

An illustration of the story of Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Paribanou, More tales from the Arabian nights by Willy Pogany (1915)

Several stories within the One Thousand and One Nights feature early science fiction elements. One example is «The Adventures of Bulukiya», where the protagonist Bulukiya’s quest for the herb of immortality leads him to explore the seas, journey to Paradise and to Hell, and travel across the cosmos to different worlds much larger than his own world, anticipating elements of galactic science fiction;[87] along the way, he encounters societies of jinn,[88] mermaids, talking serpents, talking trees, and other forms of life.[87] In «Abu al-Husn and His Slave-Girl Tawaddud», the heroine Tawaddud gives an impromptu lecture on the mansions of the Moon, and the benevolent and sinister aspects of the planets.[89]

In another 1001 Nights tale, «Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman», the protagonist Abdullah the Fisherman gains the ability to breathe underwater and discovers an underwater society that is portrayed as an inverted reflection of society on land, in that the underwater society follows a form of primitive communism where concepts like money and clothing do not exist. Other Arabian Nights tales also depict Amazon societies dominated by women, lost ancient technologies, advanced ancient civilizations that went astray, and catastrophes which overwhelmed them.[90]

«The City of Brass» features a group of travellers on an archaeological expedition[91] across the Sahara to find an ancient lost city and attempt to recover a brass vessel that Solomon once used to trap a jinni,[92] and, along the way, encounter a mummified queen, petrified inhabitants,[93] lifelike humanoid robots and automata, seductive marionettes dancing without strings,[94] and a brass horseman robot who directs the party towards the ancient city,[95] which has now become a ghost town.[85] The «Third Qalandar’s Tale» also features a robot in the form of an uncanny boatman.[95]

Poetry[edit]

There is an abundance of Arabic poetry in One Thousand and One Nights. It is often deployed by stories’ narrators to provide detailed descriptions, usually of the beauty of characters. Characters also occasionally quote or speak in verse in certain settings. The uses include but are not limited to:

- Giving advice, warning, and solutions.

- Praising God, royalties and those in power.

- Pleading for mercy and forgiveness.

- Lamenting wrong decisions or bad luck.

- Providing riddles, laying questions, challenges.

- Criticizing elements of life, wondering.

- Expressing feelings to others or one’s self: happiness, sadness, anxiety, surprise, anger.

In a typical example, expressing feelings of happiness to oneself from Night 203, Prince Qamar Al-Zaman, standing outside the castle, wants to inform Queen Bodour of his arrival.[96] He wraps his ring in a paper and hands it to the servant who delivers it to the Queen. When she opens it and sees the ring, joy conquers her, and out of happiness she chants this poem:[97]

|

وَلَقدْ نَدِمْتُ عَلى تَفَرُّقِ شَمْلِنا |

Wa-laqad nadimtu ‘alá tafarruqi shamlinā |

Translations:

|

And I have regretted the separation of our companionship |

Long, long have I bewailed the sev’rance of our loves, |

| —Literal translation | —Burton’s verse translation |

In world culture[edit]

The influence of the versions of The Nights on world literature is immense. Writers as diverse as Henry Fielding to Naguib Mahfouz have alluded to the collection by name in their own works. Other writers who have been influenced by the Nights include John Barth, Jorge Luis Borges, Salman Rushdie, Orhan Pamuk, Goethe, Walter Scott, Thackeray, Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell, Nodier, Flaubert, Marcel Schwob, Stendhal, Dumas, Hugo, Gérard de Nerval, Gobineau, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Hofmannsthal, Conan Doyle, W. B. Yeats, H. G. Wells, Cavafy, Calvino, Georges Perec, H. P. Lovecraft, Marcel Proust, A. S. Byatt and Angela Carter.[98]

Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba. Part of its popularity may have sprung from improved standards of historical and geographical knowledge. The marvelous beings and events typical of fairy tales seem less incredible if they are set further «long ago» or farther «far away»; this process culminates in the fantasy world having little connection, if any, to actual times and places. Several elements from Arabian mythology are now common in modern fantasy, such as genies, bahamuts, magic carpets, magic lamps, etc. When L. Frank Baum proposed writing a modern fairy tale that banished stereotypical elements, he included the genie as well as the dwarf and the fairy as stereotypes to go.[99]

In 1982, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) began naming features on Saturn’s moon Enceladus after characters and places in Burton’s translation[100] because «its surface is so strange and mysterious that it was given the Arabian Nights as a name bank, linking fantasy landscape with a literary fantasy.»[101]

In Arab culture[edit]

There is little evidence that the Nights was particularly treasured in the Arab world. It is rarely mentioned in lists of popular literature and few pre-18th-century manuscripts of the collection exist.[102] Fiction had a low cultural status among Medieval Arabs compared with poetry, and the tales were dismissed as khurafa (improbable fantasies fit only for entertaining women and children). According to Robert Irwin, «Even today, with the exception of certain writers and academics, the Nights is regarded with disdain in the Arabic world. Its stories are regularly denounced as vulgar, improbable, childish and, above all, badly written.»[103]

Nevertheless, the Nights have proved an inspiration to some modern Egyptian writers, such as Tawfiq al-Hakim (author of the Symbolist play Shahrazad, 1934), Taha Hussein (Scheherazade’s Dreams, 1943)[104] and Naguib Mahfouz (Arabian Nights and Days, 1979). Idries Shah finds the Abjad numerical equivalent of the Arabic title, alf layla wa layla, in the Arabic phrase umm el quissa, meaning «mother of records.» He goes on to state that many of the stories «are encoded Sufi teaching stories, descriptions of psychological processes, or enciphered lore of one kind or another.»[105]

On a more popular level, film and TV adaptations based on stories like Sinbad and Aladdin enjoyed long lasting popularity in Arabic speaking countries.

Early European literature[edit]

Although the first known translation into a European language appeared in 1704, it is possible that the Nights began exerting its influence on Western culture much earlier. Christian writers in Medieval Spain translated many works from Arabic, mainly philosophy and mathematics, but also Arab fiction, as is evidenced by Juan Manuel’s story collection El Conde Lucanor and Ramón Llull’s The Book of Beasts.[106]

Knowledge of the work, direct or indirect, apparently spread beyond Spain. Themes and motifs with parallels in the Nights are found in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (in The Squire’s Tale the hero travels on a flying brass horse) and Boccaccio’s Decameron. Echoes in Giovanni Sercambi’s Novelle and Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso suggest that the story of Shahriyar and Shahzaman was also known.[107] Evidence also appears to show that the stories had spread to the Balkans and a translation of the Nights into Romanian existed by the 17th century, itself based on a Greek version of the collection.[108]

Western literature (18th century onwards)[edit]

Galland translations (1700s)[edit]

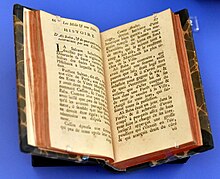

First European edition of Arabian Nights, «Les Mille et une Nuit», by Antoine Galland, Vol. 11, 1730 CE, Paris

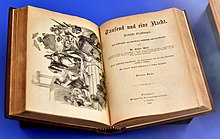

Arabian Nights, «Tausend und eine Nacht. Arabische Erzählungen», translated into German by Gustav Weil, Vol .4, 1866 CE, Stuttgart

The modern fame of the Nights derives from the first known European translation by Antoine Galland, which appeared in 1704. According to Robert Irwin, Galland «played so large a part in discovering the tales, in popularizing them in Europe and in shaping what would come to be regarded as the canonical collection that, at some risk of hyperbole and paradox, he has been called the real author of the Nights.»[109]

The immediate success of Galland’s version with the French public may have been because it coincided with the vogue for contes de fées (‘fairy stories’). This fashion began with the publication of Madame d’Aulnoy’s Histoire d’Hypolite in 1690. D’Aulnoy’s book has a remarkably similar structure to the Nights, with the tales told by a female narrator. The success of the Nights spread across Europe and by the end of the century there were translations of Galland into English, German, Italian, Dutch, Danish, Russian, Flemish and Yiddish.[110]

Galland’s version provoked a spate of pseudo-Oriental imitations. At the same time, some French writers began to parody the style and concoct far-fetched stories in superficially Oriental settings. These tongue-in-cheek pastiches include Anthony Hamilton’s Les quatre Facardins (1730), Crébillon’s Le sopha (1742) and Diderot’s Les bijoux indiscrets (1748). They often contained veiled allusions to contemporary French society. The most famous example is Voltaire’s Zadig (1748), an attack on religious bigotry set against a vague pre-Islamic Middle Eastern background.[111] The English versions of the «Oriental Tale» generally contained a heavy moralising element,[112] with the notable exception of William Beckford’s fantasy Vathek (1786), which had a decisive influence on the development of the Gothic novel. The Polish nobleman Jan Potocki’s novel Saragossa Manuscript (begun 1797) owes a deep debt to the Nights with its Oriental flavour and labyrinthine series of embedded tales.[113]

The work was included on a price-list of books on theology, history, and cartography, which was sent by the Scottish bookseller Andrew Millar (then an apprentice) to a Presbyterian minister. This is illustrative of the title’s widespread popularity and availability in the 1720s.[114]

19th century–20th century[edit]

The Nights continued to be a favourite book of many British authors of the Romantic and Victorian eras. According to A. S. Byatt, «In British Romantic poetry the Arabian Nights stood for the wonderful against the mundane, the imaginative against the prosaically and reductively rational.»[115] In their autobiographical writings, both Coleridge and de Quincey refer to nightmares the book had caused them when young. Wordsworth and Tennyson also wrote about their childhood reading of the tales in their poetry.[116] Charles Dickens was another enthusiast and the atmosphere of the Nights pervades the opening of his last novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870).[117]

Several writers have attempted to add a thousand and second tale,[118] including Théophile Gautier (La mille deuxième nuit, 1842)[104] and Joseph Roth (Die Geschichte von der 1002 Nacht, 1939).[118] Edgar Allan Poe wrote «The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade» (1845), a short story depicting the eighth and final voyage of Sinbad the Sailor, along with the various mysteries Sinbad and his crew encounter; the anomalies are then described as footnotes to the story. While the king is uncertain—except in the case of the elephants carrying the world on the back of the turtle—that these mysteries are real, they are actual modern events that occurred in various places during, or before, Poe’s lifetime. The story ends with the king in such disgust at the tale Scheherazade has just woven, that he has her executed the very next day.

Another important literary figure, the Irish poet W. B. Yeats was also fascinated by the Arabian Nights, when he wrote in his prose book, A Vision an autobiographical poem, titled The Gift of Harun Al-Rashid,[119] in relation to his joint experiments with his wife Georgie Hyde-Lees, with Automatic writing. The automatic writing, is a technique used by many occultists in order to discern messages from the subconscious mind or from other spiritual beings, when the hand moves a pencil or a pen, writing only on a simple sheet of paper and when the person’s eyes are shut. Also, the gifted and talented wife, is playing in Yeats’s poem as «a gift» herself, given only allegedly by the caliph to the Christian and Byzantine philosopher Qusta Ibn Luqa, who acts in the poem as a personification of W. B. Yeats. In July 1934 he was asked by Louis Lambert, while in a tour in the United States, which six books satisfied him most. The list that he gave placed the Arabian Nights, secondary only to William Shakespeare’s works.[120]

Modern authors influenced by the Nights include James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Jorge Luis Borges, John Barth and Ted Chiang.

Film, radio and television[edit]

Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1917).

Stories from the One Thousand and One Nights have been popular subjects for films, beginning with Georges Méliès’ Le Palais des Mille et une nuits (1905).

The critic Robert Irwin singles out the two versions of The Thief of Baghdad (1924 version directed by Raoul Walsh; 1940 version produced by Alexander Korda) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Il fiore delle Mille e una notte (1974) as ranking «high among the masterpieces of world cinema.»[121] Michael James Lundell calls Il fiore «the most faithful adaptation, in its emphasis on sexuality, of The 1001 Nights in its oldest form.»[122]

Alif Laila (transl. One Thousand Nights; 1933) was a Hindi-language fantasy film based on One Thousand and One Nights from the early era of Indian cinema, directed by Balwant Bhatt and Shanti Dave. K. Amarnath made, Alif Laila (1953), another Indian fantasy film in Hindi based on the folktale of Aladdin.[123] Niren Lahiri’s Arabian Nights, an adventure-fantasy film adaptation of the stories, released in 1946.[124] A number of Indian films based on the Nights and The Thief of Baghdad were produced over the years, including Baghdad Ka Chor (1946), Baghdad Thirudan (1960), and Baghdad Gaja Donga (1968).[123] A television series, Thief of Baghdad, was also made in India which aired on Zee TV between 2000 and 2001.

UPA, an American animation studio, produced an animated feature version of 1001 Arabian Nights (1959), featuring the cartoon character Mr. Magoo.[125]

The 1949 animated film The Singing Princess, another movie produced in Italy, is inspired by The Arabian Nights. The animated feature film, One Thousand and One Arabian Nights (1969), produced in Japan and directed by Osamu Tezuka and Eichii Yamamoto, featured psychedelic imagery and sounds, and erotic material intended for adults.[126]

Alif Laila (The Arabian Nights), a 1993–1997 Indian TV series based on the stories from One Thousand and One Nights produced by Sagar Entertainment Ltd, aired on DD National starts with Scheherazade telling her stories to Shahryār, and contains both the well-known and the lesser-known stories from One Thousand and One Nights. Another Indian television series, Alif Laila, based on various stories from the collection aired on Dangal TV in 2020.[127]

Alf Leila Wa Leila, Egyptian television adaptations of the stories was broadcast between the 80’s and early 90’s, with each series featuring a cast of big name Egyptian performers such as Hussein Fahmy, Raghda, Laila Elwi, Yousuf Shaaban (actor), Nelly (Egyptian entertainer), Sherihan and Yehia El-Fakharany. Each series premiered on every yearly month of Ramadan between the 1980s and 1990s.[128]

One of the best known Arabian Nights-based films is the 1992 Walt Disney animated movie Aladdin, which is loosely based on the story of the same name.

Arabian Nights (2000), a two-part television mini-series adopted for BBC and ABC studios, starring Mili Avital, Dougray Scott, and John Leguizamo, and directed by Steve Barron, is based on the translation by Sir Richard Francis Burton.

Shabnam Rezaei and Aly Jetha created, and the Vancouver-based Big Bad Boo Studios produced 1001 Nights (2011), an animated television series for children, which launched on Teletoon and airs in 80 countries around the world, including Discovery Kids Asia.[129]

Arabian Nights (2015, in Portuguese: As Mil e uma Noites), a three-part film directed by Miguel Gomes, is based on One Thousand and One Nights.[130]

Alf Leila Wa Leila, a popular Egyptian radio adaptation was broadcast on Egyptian radio stations for 26 years. Directed by famed radio director Mohamed Mahmoud Shabaan also known by his nickname Baba Sharoon, the series featured a cast of respected Egyptian actors, among them Zouzou Nabil as Scheherazade and Abdelrahim El Zarakany as Shahryar.[131]

Music[edit]

The Nights has inspired many pieces of music, including:

Classical

- François-Adrien Boieldieu: Le calife de Bagdad (1800)

- Carl Maria von Weber: Abu Hassan (1811)

- Luigi Cherubini: Ali Baba (1833)

- Robert Schumann: Scheherazade (1848)

- Peter Cornelius: Der Barbier von Bagdad (1858)

- Ernest Reyer: La statue (1861)

- C. F. E. Horneman (1840–1906), Aladdin (overture), 1864

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade Op. 35 (1888)[132]

- Tigran Chukhajian (1837–1898), Zemire (1891)

- Maurice Ravel (1875–1937), Shéhérazade (1898)

- Ferrucio Busoni: Piano Concerto in C major (1904)

- Henri Rabaud: Mârouf, savetier du Caire (1914)

- Carl Nielsen, Aladdin Suite (1918–1919)

- Collegium musicum, Suita po tisic a jednej noci (1969)

- Fikret Amirov: Arabian Nights (Ballet, 1979)

- Ezequiel Viñao, La Noche de las Noches (1990)

- Carl Davis, Aladdin (Ballet, 1999)

Pop, rock, and metal

- Umm Kulthum: Alf Leila Wa Leila (1969)

- Renaissance: Scheherazade and Other Stories (1975)

- Doce: Ali-Bábá, um homem das Arábias (1981)

- Icehouse: No Promises (From the album ‘Measure for Measure’) (1986)

- Kamelot, Nights of Arabia (From the album ‘The Fourth Legacy’) (1999)

- Sarah Brightman, Harem and Arabian Nights (From the album ‘Harem’) (2003)

- Ch!pz, «1001 Arabian Nights (song)» (From the album The World of Ch!pz) (2006)

- Nightwish, Sahara (2007)

- Rock On!!, Sinbad The Sailor (2008)

- Abney Park, Scheherazade (2013)

Musical Theatre

- A Thousand And One Nights (From Twisted: The Untold Story of a Royal Vizier) (2013)

Games[edit]

Popular modern games with an Arabian Nights theme include the Prince of Persia series, Crash Bandicoot: Warped, Sonic and the Secret Rings, Disney’s Aladdin, Bookworm Adventures, and the pinball table, Tales of the Arabian Nights. Additionally, the popular game Magic the Gathering released a set titled Arabian Nights.

Illustrators[edit]

Many artists have illustrated the Arabian nights, including: Pierre-Clément Marillier for Le Cabinet des Fées (1785–1789), Gustave Doré, Léon Carré (Granville, 1878 – Alger, 1942), Roger Blachon, Françoise Boudignon, André Dahan, Amato Soro, Albert Robida, Alcide Théophile Robaudi and Marcelino Truong; Vittorio Zecchin (Murano, 1878 – Murano, 1947) and Emanuele Luzzati; The German Morgan; Mohammed Racim (Algiers, 1896 – Algiers 1975), Sani ol-Molk (1849–1856), Anton Pieck and Emre Orhun.

Famous illustrators for British editions include: Arthur Boyd Houghton, John Tenniel, John Everett Millais and George John Pinwell for Dalziel’s Illustrated Arabian Nights Entertainments, published in 1865; Walter Crane for Aladdin’s Picture Book (1876); Frank Brangwyn for the 1896 edition of Lane’s translation; Albert Letchford for the 1897 edition of Burton’s translation; Edmund Dulac for Stories from the Arabian Nights (1907), Princess Badoura (1913) and Sindbad the Sailor & Other Tales from the Arabian Nights (1914). Others artists include John D. Batten, (Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights, 1893), Kay Nielsen, Eric Fraser, Errol le Cain, Maxfield Parrish, W. Heath Robinson and Arthur Szyk (1954).[133]

Gallery[edit]

-

The Sultan

-

One Thousand and One Nights book.

-

The fifth voyage of Sindbad

-

William Harvey, The Fifth Voyage of Es-Sindbad of the Sea, 1838–40, woodcut

-

William Harvey, The Story of the Two Princes El-Amjad and El-As’ad, 1838–40, woodcut

-

William Harvey, The Story of Abd Allah of the Land and Abd Allah of the Sea

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of Abon-Hassan the Wag («He found himself upon the royal couch»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of the Merchant («Sheherezade telling the stories»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of Ansal-Wajooodaud, Rose-in-Bloom («The daughter of a Visier sat at a lattice window»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of Gulnare («The merchant uncovered her face»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of Beder Basim («Whereupon it became eared corn»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of Abdalla («Abdalla of the sea sat in the water, near the shore»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of Mahomed Ali («He sat his boat afloat with them»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

-

Frank Brangwyn, Story of the City of Brass («They ceased not to ascend by that ladder»), 1895–96, watercolour and tempera on millboard

See also[edit]

- Arabic literature

- Ghost stories

- Hamzanama

- List of One Thousand and One Nights characters

- List of stories from The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (translation by R. F. Burton)

- List of works influenced by One Thousand and One Nights

- Persian literature

- Shahnameh

- The Panchatantra — an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose, arranged within a frame story.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2007). «Arabian Nights». In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_0021.

Arabian Nights, the work known in Arabic as Alf layla wa-layla

- ^ See illustration of title page of Grub St Edition in Yamanaka and Nishio (p. 225)

- ^ Ben Pestell; Pietra Palazzolo; Leon Burnett, eds. (2016). Translating Myth. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9781134862566.

- ^

Marzolph (2007), «Arabian Nights», Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. I, Leiden: Brill. - ^ Horta, Paulo Lemos (2017-01-16). Marvellous Thieves. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97377-0.

- ^ Doyle, Laura (2020-11-02). Inter-imperiality: Vying Empires, Gendered Labor, and the Literary Arts of Alliance. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-1261-0.

- ^ John Payne, Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp and Other Stories, (London 1901) gives details of Galland’s encounter with ‘Hanna’ in 1709 and of the discovery in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris of two Arabic manuscripts containing Aladdin and two more of the added tales. Text of «Alaeddin and the enchanted lamp»

- ^ The Arabian Nights, translated by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons (Penguin Classics, 2008), vol. 1, p. 1

- ^ The Third Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman – The Arabian Nights – The Thousand and One Nights – Sir Richard Burton translator. Classiclit.about.com (2013-07-19). Retrieved on 2013-09-23.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 48.

- ^ a b Reynolds p. 271

- ^ Hamori, A. (2012). «S̲h̲ahrazād». In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6771.

- ^ «Vikram and the Vampire, or, Tales of Hindu devilry, by Richard Francis Burton—A Project Gutenberg eBook». www.gutenberg.org. p. xiii.

- ^ Artola. Pancatantra Manuscripts from South India in the Adyar Library Bulletin. 1957. pp. 45ff.

- ^ K. Raksamani. The Nandakaprakarana attributed to Vasubhaga, a Comparative Study. University of Toronto Thesis. 1978. pp. 221ff.

- ^ E. Lorgeou. Les entretiensde Nang Tantrai. Paris. 1924.

- ^ C. Hooykaas. Bibliotheca Javaneca No. 2. Bandoeng. 1931.

- ^ A. K. Warder. Indian Kāvya Literature: The art of storytelling, Volume VI. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. 1992. pp. 61–62, 76–82.

- ^ IIS.ac.uk Dr Fahmida Suleman, «Kalila wa Dimna» Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine, in Medieval Islamic Civilization, An Encyclopaedia, Vol. II, pp. 432–33, ed. Josef W. Meri, New York-London: Routledge, 2006

- ^ The Fables of Kalila and Dimnah, translated from the Arabic by Saleh Sa’adeh Jallad, 2002. Melisende, London, ISBN 1-901764-14-1

- ^ Kalilah and Dimnah; or, The fables of Bidpai; being an account of their literary history, p. xiv

- ^ Pinault p. 1

- ^ Pinault p. 4

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 49.

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Eva Sallis Scheherazade Through the Looking-Glass: The Metamorphosis of the Thousand and One Nights (Routledge, 1999), p. 2 and note 6

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Safa Khulusi, Studies in Comparative Literature and Western Literary Schools, Chapter: Qisas Alf Laylah wa Laylah (One thousand and one Nights), pp. 15–85. Al-Rabita Press, Baghdad, 1957.

- ^ Safa Khulusi, The Influence of Ibn al-Muqaffa’ on The Arabian Nights. Islamic Review, Dec 1960, pp. 29–31

- ^ The Thousand and One Nights; Or, The Arabian Night’s Entertainments – David Claypoole Johnston – Google Books. Books.google.com.pk. Retrieved on 2013-09-23.

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 50.

- ^ a b Reynolds p. 270

- ^ a b c Beaumont, Daniel. Literary Style and Narrative Technique in the Arabian Nights. p. 1. In The Arabian nights encyclopedia, Volume 1

- ^ a b c Irwin 2004, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Marzolph, Ulrich (2017). «Arabian Nights». In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_0021.

- ^ a b c Sallis, Eva. 1999. Sheherazade through the looking glass: the metamorphosis of the Thousand and One Nights. pp. 18–43

- ^ Payne, John (1901). The Book Of Thousand Nights And One Night Vol-ix. London. p. 289. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Pinault, David. Story-telling techniques in the Arabian nights. pp. 1–12. Also in Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature, v. 1

- ^ The Alif Laila or, Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, Commonly Known as ‘The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments’, Now, for the First Time, Published Complete in the Original Arabic, from an Egyptian Manuscript Brought to India by the Late Major Turner Macan, ed. by W. H. Macnaghten, vol. 4 (Calcutta: Thacker, 1839–42).

- ^ a b «Les Mille et une nuits». Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ The Thousand and One Nights (Alf layla wa-layla), from the Earliest Known Sources, ed. by Muhsin Mahdi, 3 vols (Leiden: Brill, 1984–1994), ISBN 9004074287.

- ^ Madeleine Dobie, 2009. Translation in the contact zone: Antoine Galland’s Mille et une nuits: contes arabes. p. 37. In Makdisi, Saree and Felicity Nussbaum (eds.): «The Arabian Nights in Historical Context: Between East and West»

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Alf laylah wa-laylah: bi-al-ʻāmmīyah al-Miṣrīyah: layālī al-ḥubb wa-al-ʻishq, ed. by Hishām ʻAbd al-ʻAzīz and ʻĀdil ʻAbd al-Ḥamīd (Cairo: Dār al-Khayyāl, 1997), ISBN 9771922521.

- ^ a b c Goeje, Michael Jan de (1911). «Thousand and One Nights» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 883.

- ^ a b c Sallis, Eva. 1999. Sheherazade through the looking glass: the metamorphosis of the Thousand and One Nights. pp. 4 passim

- ^ a b c Marzolph, Ulrich and Richard van Leeuwen. 2004. The Arabian nights encyclopedia, Volume 1. pp. 506–08

- ^ The Arabian Nights, trans. by Husain Haddawy (New York: Norton, 1990).

- ^ a b Irwin 2004.

- ^ The Arabian Nights II: Sindbad and Other Popular Stories, trans. by Husain Haddawy (New York: Norton, 1995).

- ^ The Arabian Nights: The Husain Haddawy Translation Based on the Text Edited by Muhsin Mahdi, Contexts, Criticism, ed. by Daniel Heller-Roazen (New York: Norton, 2010).

- ^ PEN American Center. Pen.org. Retrieved on 2013-09-23.

- ^ Flood, Alison (December 15, 2021). «New Arabian Nights translation to strip away earlier versions’ racism and sexism». www.theguardian.com. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Dwight Reynolds. «The Thousand and One Nights: A History of the Text and its Reception.» The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: Arabic Literature in the Post-Classical Period. Cambridge UP, 2006.

- ^ «The Oriental Tale in England in the Eighteenth Century», by Martha Pike Conant, Ph.D. Columbia University Press (1908)

- ^ Mack, Robert L., ed. (2009) [1995]. Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xvi, xxv. ISBN 978-0192834799. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Irwin 2010, p. 474.

- ^ Irwin 2010, p. 497.

- ^

Ulrich Marzolph, The Arabian nights in transnational perspective, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8143-3287-0, p. 230. - ^ a b Heath, Peter (May 1994), «Reviewed work(s): Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights by David Pinault», International Journal of Middle East Studies, Cambridge University Press, 26 (2): 358–60 [359–60], doi:10.1017/s0020743800060633, S2CID 162223060

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jorg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Animal tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 499.

- ^ Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004), The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, pp. 3–4, ISBN 1-57607-204-5

- ^ Burton, Richard (September 2003), The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, Volume 1, Project Gutenberg, archived from the original on 2012-01-18, retrieved 2008-10-17

- ^ a b c Heath, Peter (May 1994), «Reviewed work(s): Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights by David Pinault», International Journal of Middle East Studies, Cambridge University Press, 26 (2): 358–60 [360], doi:10.1017/s0020743800060633, S2CID 162223060

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 200.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 198.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Heath, Peter (May 1994), «Reviewed work(s): Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights by David Pinault», International Journal of Middle East Studies, Cambridge University Press, 26 (2): 358–60 [359], doi:10.1017/s0020743800060633, S2CID 162223060

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 199.

- ^ a b Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004), The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, p. 109, ISBN 1-57607-204-5

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 93.

- ^ Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004), The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, p. 4, ISBN 1-57607-204-5

- ^ Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004), The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, pp. 97–98, ISBN 1-57607-204-5

- ^ «Ali with the Large Member» is only in the Wortley Montague manuscript (1764), which is in the Bodleian Library, and is not found in Burton or any of the other standard translations. (Ref: Arabian Nights Encyclopedia).

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, p. 59, ISBN 90-04-09530-6

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006), The Arabian Nights Reader, Wayne State University Press, pp. 240–42, ISBN 0-8143-3259-5

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill, pp. 93, 95, 97, ISBN 90-04-09530-6

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 91, 93, ISBN 90-04-09530-6

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006), The Arabian Nights Reader, Wayne State University Press, p. 240, ISBN 0-8143-3259-5

- ^ Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004), The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, pp. 2–4, ISBN 1-57607-204-5

- ^ Yuriko Yamanaka, Tetsuo Nishio (2006), The Arabian Nights and Orientalism: Perspectives from East & West, I.B. Tauris, p. 83, ISBN 1-85043-768-8

- ^ Al-Hakawati. «The Story of Gherib and his Brother Agib«. Thousand Nights and One Night. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2008.

- ^ a b Hamori, Andras (1971), «An Allegory from the Arabian Nights: The City of Brass», Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Cambridge University Press, 34 (1): 9–19 [10], doi:10.1017/S0041977X00141540, S2CID 161610007 The hero of the tale is an historical person, Musa bin Nusayr.

- ^ Daniel Harms, John Wisdom Gonce, John Wisdom Gonce, III (2003), The Necronomicon Files: The Truth Behind Lovecraft’s Legend, Weiser, pp. 87–90, ISBN 978-1-57863-269-5

- ^ a b Irwin 2004, p. 209.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 204.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Hamori, Andras (1971), «An Allegory from the Arabian Nights: The City of Brass», Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Cambridge University Press, 34 (1): 9–19 [9], doi:10.1017/S0041977X00141540, S2CID 161610007

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 148–49, 217–19, ISBN 90-04-09530-6

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 213.

- ^ Hamori, Andras (1971), «An Allegory from the Arabian Nights: The City of Brass», Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Cambridge University Press, 34 (1): 9–19 [12–3], doi:10.1017/S0041977X00141540, S2CID 161610007

- ^ a b Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill, pp. 10–11, ISBN 90-04-09530-6

- ^ Burton Nights. Mythfolklore.net (2005-01-01). Retrieved on 2013-09-23.

- ^ Tale of Nur Al-Din Ali and His Son Badr Al-Din Hasan – The Arabian Nights – The Thousand and One Nights – Sir Richard Burton translator. Classiclit.about.com

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 290.

- ^ James Thurber, «The Wizard of Chitenango», p. 64 Fantasists on Fantasy edited by Robert H. Boyer and Kenneth J. Zahorski, ISBN 0-380-86553-X.

- ^ Blue, J.; (2006) Categories for Naming Planetary Features. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ «IAU Information Bulletin No. 104» (PDF). Iau.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2021-11-06.

- ^ Reynolds p. 272

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b «Encyclopaedia Iranica». Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Shah, Idries (1977) [1964]. The Sufis. London, UK: Octagon Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 0-86304-020-9.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Reynolds pp. 279–81

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 238–241.

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 242.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 245–260.

- ^ «The manuscripts, Letter from Andrew Millar to Robert Wodrow, 5 August, 1725. Andrew Millar Project. University of Edinburgh». www.millar-project.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ^ A. S. Byatt On Histories and Stories (Harvard University Press, 2001) p. 167

- ^ Wordsworth in Book Five of The Prelude; Tennyson in his poem «Recollections of the Arabian Nights«. (Irwin, pp. 266–69)

- ^ Irwin 2004, p. 270.

- ^ a b Byatt p. 168

- ^ «The Cat and the Moon and Certain Poems by William Butler Yeats» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Jeffares, A. Norman; Cross, K. G. W. (1965). In Excited Reverie: Centenary Tribute to W.B. Yeats. Springer. ISBN 978-1349006465 – via Google Books.

- ^ Irwin 2004, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Lundell, Michael (2013), «Pasolini’s Splendid Infidelities: Un/Faithful Film Versions of The Thousand and One Nights«, Adaptation, Oxford University Press, 6 (1): 120–27, doi:10.1093/adaptation/aps022

- ^ a b Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9781579581466.

- ^ «Arabian Nights (1946)». Indiancine.ma.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. New American Library. pp. 341–42. ISBN 0-452-25993-2.

- ^ One Thousand and One Arabian Nights Review (1969). Thespinningimage.co.uk. Retrieved on 2013-09-23.

- ^ «Dangal TV’s new fantasy drama Alif Laila soon on TV». ABP News. 2020-02-24.

- ^ «ألف ليلة وليلة ׀ ليلى والإشكيف׃ تتر بداية». YouTube. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ 1001 Nights heads to Discovery Kids Asia. Kidscreen (2013-06-13). Retrieved on 2013-09-23.

- ^ The Most Ambitious Movie At This Year’s Cannes Film Festival is ‘Arabian Nights’. Retrieved on 2015-01-18.

- ^ ألف ليلة وليلة .. الليلة الأولى: حكاية شهريار ولقائه الأول مع شهرزاد. Egyptian Radio.

- ^ See Encyclopædia Iranica (NB: Some of the dates provided there are wrong)

- ^ Irwin, Robert (March 12, 2011). «The Arabian Nights: a thousand and one illustrations». The Guardian.

General sources[edit]

- Irwin, Robert (2004). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-983-1. OCLC 693781081.

- Irwin, Robert (2010). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-051-2. OCLC 843203755.

- Ch. Pellat, «Alf Layla Wa Layla» in Encyclopædia Iranica. Online Access June 2011 at [1]

- David Pinault Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights (Brill Publishers, 1992)

- Dwight Reynolds, «A Thousand and One Nights: a history of the text and its reception» in The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature Vol 6. (CUP 2006)

- Eva Sallis Scheherazade Through the Looking-Glass: The Metamorphosis of the Thousand and One Nights (Routledge, 1999),

- Ulrich Marzolph (ed.) The Arabian Nights Reader (Wayne State University Press, 2006)

- Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf,The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia (2004)

- Yamanaka, Yuriko and Nishio, Tetsuo (ed.) The Arabian Nights and Orientalism – Perspectives from East and West (I.B. Tauris, 2006) ISBN 1-85043-768-8

Further reading[edit]