| «Silver Hoof» | |

|---|---|

| by Pavel Bazhov | |

| Original title | Серебряное копытце |

| Translator | Alan Moray Williams (first), Eve Manning, et al. |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Series | The Malachite Casket collection (list of stories) |

| Genre(s) | skaz (fairy tale) |

| Published in | Uralsky Sovremennik |

| Publication type | anthology |

| Publisher | Sverdlovsk Publishing House |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 1938 |

| Published in English | 1944 |

«Silver Hoof» (Russian: Серебряное копытце, tr. Serebrjanoe kopyttse, lit. «Small Silver Hoof») is a fairy tale short story written by Pavel Bazhov, based on the folklore of the Ural region of Siberia. It was first published in Uralsky Sovremennik in 1938, and later included in The Malachite Casket collection. In this fairy tale, the characters meet the legendary zoomorphic[1] creature from the Ural folklore called Silver Hoof. In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson.[2][3] In the 1950s another translation was made by Eve Manning.[4][5][6] It was included in James Riordan’s collection of stories The Mistress of the Copper Mountain: Tales from the Urals, published in 1974 by Frederick Muller Ltd.[7] Riordan heard the tales from a headteacher when he was bedridden in Sverdlovsk. After returning to England he rewrote the tales from memory, checking them against Bazhov’s book. He preferred not to call himself «translator», he believed that «communicator» was more appropriate.[8]

Sources[edit]

Bazhov’s stories are based on the oral lore of the miners and gold prospectors.[9] The character of Silver Hoof is based on the Ural legends. Bazhov mentioned that he had heard tales about the mythical creature Silver Deer, also known as the elk Golden Horns and the goat Silver Hoof.[10] The exact origin of the creature is unknown, but deer have significant roles in the mythology of various peoples located all over the world. In the folklore tales, the goat/deer can be either friendly or harmful.[11] Golden or silver deer/elk became popular at the Urals in the 18th century.[12] According to the Bashkir folklore, dreaming about a goat is a good omen.[12] The Finnic peoples prayed to the Elk.[1] The depictions of the animal were found among Permian bronze casts.[1] While the character of Silver Hoof is in fact based on the legends, the actual storyline was penned by Bazhov.[13]

Publication[edit]

The author heard the tales about the goat with a silver hoof at the Urals from the hunter named Bulatov. The tales seemed to originate from the area where many people were engaged in the searches for chrysolites. But Bazhov had to write the storyline for «Silver Hoof» himself.[13] «Silver Hoof» was completed on 3 August 1938.[13]

The tale was not included in the first edition of The Malachite Box. But, inspired by its success, Bazhov continued working on his stories. The tales «Sinyushka’s Well», «Silver Hoof», and «The Demidov Caftans» were finished before the publication of the collection.[14] It was first published in 1938 in the 2nd volume of Sverdlovsk Publishing House’s Uralsky Sovremennik.[15] It was then released as a part of Sverdlovsk Publishing House’s children’s collection Morozko.[16]

Plot[edit]

An old man Kokovanya has no family and decides to take an orphan into his house. He finds out that Daryonka (lit. «A gift»), a 6-year-old girl, has recently lost her family and invites her to live with him. She accepts, and when she asks about his profession, he reveals that he works as a gold prospector in summer, and in winter he’s hunting a certain goat in the forests, because he wants «to see where he stamps his right forefoot».[17] Kokovanya, Daryonka and her cat named Muryonka start living together.

Kokovanya works to earn their living, the girl cleans the house and cooks. Winter comes, and Kokovanya decides to go hunting in the forest as usual. He tells Daryonka about the grey goat called Silver Hoof:

That’s a very special goat. On his right forefoot he’s got a silver hoof. And when he stamps with that silver hoof he leaves a gem there. If he stamps once there’s one gem, if he stamps twice there are two, and if he begins to paw the ground there’ll be a whole pile. […] Ordinary goats have two horns, but this one’s got antlers, with five tines.[18]

Unlike other goats’ horns, Silver Hoof’s horns are not shed in winter, and that is how Kokovanya is planning to recognize him. Daryonka begs the old man to take her hunting, and he reluctantly agrees. The cat follows them too. In the forest, Kokovanya goes hunting every day and comes back with a lot of regular goat meat and skins. Soon they have so much meat that Kokovanya has to go back to the village to bring the horse, so that they could carry everything back. He leaves the girl in the forest for a while.

Next morning Daryonka sees Silver Hoof passing by. That night, she sees her cat Muryonka sitting in the glade with the goat in front of her, as if they are communicating. They run about the glade for a long time. Next day Muryonka and the goat are gone, but Kokovanya and Daryonka find a lot of gemstones. «After that people often found stones in the glade where the goat had run about. Most of them were green ones, chrysolites, folks call them.»[19]

Analysis[edit]

Pavel Bazhov indicated that all his stories can be divided into two groups based on tone: «child-toned» (e.g. «The Fire-Fairy») and «adult-toned» (e.g. «The Stone Flower»). He called «Silver Hoof» a «child-toned» story.[20] Such stories have simple plots, children are the main characters, and the mythical creatures help them, typically leading the story to a happy ending.[21]

In Bazhov’s tales chrysolites, unlike ill-omened malachite and emeralds, are meant for humans and bring happiness to their lives. They are «children’s» stones that appear in the «child-toned» stories. Children play with chrysolites in the very first story from The Malachite Box, «Beloved Name». As an amulet, the chrysolite can banish demons, strengthen spiritual resistance, give courage and protect from night terrors. After his «conversation» with the cat, Silver Hoof gives the gemstones as a gift to Daryonka. This gift can be regarded as corporeal and spiritual at the same time, a sacred gift that is bestowed upon good people only.[22] Bazhov himself did not believe that gemstones could bring luck or protect from envy, jealousy and the evil eye.[23]

Bazhov liked the idea of a child together with an old man contacting the mythical creatures. These people are traditionally portrayed as the closest to the otherworldly, but at the same time they are the least reliable narrators in the adult world.[24] The cat Muryonka is a literary creation, not the folklore character, because such insignificant character couldn’t have remained intact in the oral tradition.[1] It is an «intermediary», a linking creature that ties the real world and the mythical world.[25] Cats in the literary tradition cats are often depicted as travellers between worlds.[26]

Adaptations[edit]

A 1947 children’s play of the same name was written by Bazhov and Evgeny Permyak.[27] Mariya Litovskaya criticized Permyak for oversimplifying an already simple story. She commented that he had been obviously trying to create a fun children’s play, and therefore had added a clear antagonist and a lot of secondary characters, such as the fox, the bear, the eagle-owl. Litovskaya said that he had turned the «multilayered tale» into «the tale of friendship between humans and animals, and the battle between good and evil».[28] She also noted that Pavel Bazhov had not been opposed to the changes.[29]

Lyubov Nikolskaya composed the children’s opera Silver Hoof based on the story of the same name in 1959.[30][31]

There is a radio play by Beryl E. Jones.[32]

The 1978 film[edit]

The film Podaryonka (also known as Little Present[33]), based on «Silver Hoof», was a part of the animated film series made at Sverdlovsk Film Studio[33][34] from the early 1970s to early 1980s, on time for the 100th anniversary since the birth of Pavel Bazhov. The series included the following films: Sinyushka’s Well (1973), The Mistress of the Copper Mountain (1975), The Malachite Casket, The Stone Flower (1977), Podaryonka, Golden Hair (1979), and The Grass Hideaway (1982).[35][36][37]

Podaryonka is a stop motion animated film directed by Igor Reznikov, with screenplay by Alexander Rozin.[33] It was narrated by V. Dugin,.[34] The music was composed by Vladislav Kazenin[33] performed by the State Symphony Cinema Orchestra.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Ivanov, Alexei (2004). «Угорский архетип в демонологии сказов Бажова» [The Ugrian Archetype in the Demonology of Bazhov’s Stories]. The Philologist. The Perm State Humanitarian and Pedagogical University (5). ISSN 2076-4154.

- ^ The malachite casket; tales from the Urals, (Book, 1944). WorldCat. OCLC 1998181. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov, Pavel Petrovich; Translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. p. 149. ISBN 9787250005603.

- ^ «Malachite casket : tales from the Urals / P. Bazhov ; [translated from the Russian by Eve Manning ; illustrated by O. Korovin ; designed by A. Vlasova]». The National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Malachite casket; tales from the Urals. (Book, 1950s). WorldCat. OCLC 10874080. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 9.

- ^ «The mistress of the Copper Mountain : tales from the Urals / [collected by] Pavel Bazhov ; [translated and adapted by] James Riordan». Trove. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Lathey, Gillian (July 24, 2015). Translating Children’s Literature. Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 9781317621317.

- ^ Yermakova, G (1976). «Заметки о киноискусстве На передовых рубежах» [The Notes about Cinema At the Outer Frontiers]. Zvezda (11): 204–205.

… сказы Бажова основаны на устных преданиях горнорабочих и старателей, воссоздающих реальную атмосферу того времени.

- ^ Bazhov, Pavel (2014-07-10). У старого рудника [By the Old Mine]. The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 9785457073548.

- ^ Shvabauer 2009, p. 64.

- ^ a b Shvabauer 2009, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Batin 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Batin 1983, p. 8.

- ^ Серебряное копытце [Silver Hoof] (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Rozhdestvenskaya, Yelena (2005). «Moemu neizmenno okryljajushhemu redaktoru: vspominaja Pavla Petrovicha Bazhova» Моему неизменно окрыляющему редактору: вспоминая Павла Петровича Бажова [To my always inspiring editor: remembering Pavel Petrovich Bazhov]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 226.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 237.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 231.

- ^ «Bazhov P. P. The Malachite Box» (in Russian). Bibliogid. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 247.

- ^ Prikazchikova, E. (2003). «Каменная сила медных гор Урала» [The Stone Force of The Ural Copper Mountains] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian) (28): 20–21.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Zherdev, D. V. (2003). «Бинарность как элемент поэтики бажовских сказов» [Binarity as the Poetic Element in Bazhov’s Skazy] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 52.

- ^ Shvabauer 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Shvabauer 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 248.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 252.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 251.

- ^ «Nikolskaya Lyubov Borisovna» (in Russian). The Union of Sverdlovsk Oblast Composers. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Sokolskaya, Zh. «P. P. Bazhov i muzyka Urala П. П. Бажов и музыка Урала [Pavel Bazhov and the Ural music]» in: P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm.

- ^ «Broadcast — BBC Programme Index».

- ^ a b c d «A Little Present». Animator.ru. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ a b «The list of animated films» (in Russian). Soyztelefilm. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ «A Malachite Casket». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Mistress of the Coppery Mountain». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Golden Hair». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

References[edit]

- Bazhov, Pavel (1952). Valentina Bazhova; Alexey Surkov; Yevgeny Permyak (eds.). Sobranie sochinenij v trekh tomakh Собрание сочинений в трех томах [Works. In Three Volumes] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. ISBN 9787250005603.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Eve Manning (1950s). Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Shvabauer, Nataliya (10 January 2009). «Tipologija fantasticheskih personazhej v folklore gornorabochih Zapadnoj Evropy i Rossii» Типология фантастических персонажей в фольклоре горнорабочих Западной Европы и России [The Typology of the Fantastic Characters in the Miners’ Folklore of Western Europe and Russia] (PDF). Dissertation (in Russian). The Ural State University. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Litovskaya, Mariya (2014). «Vzroslyj detskij pisatel Pavel Bazhov: konflikt redaktur» Взрослый детский писатель Павел Бажов: конфликт редактур [The Adult-Children’s Writer Pavel Bazhov: The Conflict of Editing]. Detskiye Chteniya (in Russian). 6 (2): 243–254.

- Batin, Mikhail (1983). «Istorija sozdanija skaza Malahitovaja shkatulka» История создания сказа «Малахитовая шкатулка» [The Malachite Box publication history] (in Russian). The official website of the Polevskoy Town District. Retrieved 30 November 2015.[permanent dead link]

- Nikulina, Maya (2003). «Pro zemelnye dela i pro tajnuju silu. O dalnikh istokakh uralskoj mifologii P.P. Bazhova» Про земельные дела и про тайную силу. О дальних истоках уральской мифологии П.П. Бажова [Of land and the secret force. The distant sources of P.P. Bazhov’s Ural mythology]. Filologichesky Klass (in Russian). Cyberleninka.ru. 9.

- P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm // Tvorchestvo P.P. Bazhova v menjajushhemsja mire П. П. Бажов и социалистический реализм // Творчество П. П. Бажова в меняющемся мире [Pavel Bazhov and socialist realism // The works of Pavel Bazhov in the changing world]. The materials of the inter-university research conference devoted to the 125th birthday (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: The Ural State University. 28–29 January 2004. pp. 18–26.

| «Silver Hoof» | |

|---|---|

| by Pavel Bazhov | |

| Original title | Серебряное копытце |

| Translator | Alan Moray Williams (first), Eve Manning, et al. |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Series | The Malachite Casket collection (list of stories) |

| Genre(s) | skaz (fairy tale) |

| Published in | Uralsky Sovremennik |

| Publication type | anthology |

| Publisher | Sverdlovsk Publishing House |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 1938 |

| Published in English | 1944 |

«Silver Hoof» (Russian: Серебряное копытце, tr. Serebrjanoe kopyttse, lit. «Small Silver Hoof») is a fairy tale short story written by Pavel Bazhov, based on the folklore of the Ural region of Siberia. It was first published in Uralsky Sovremennik in 1938, and later included in The Malachite Casket collection. In this fairy tale, the characters meet the legendary zoomorphic[1] creature from the Ural folklore called Silver Hoof. In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson.[2][3] In the 1950s another translation was made by Eve Manning.[4][5][6] It was included in James Riordan’s collection of stories The Mistress of the Copper Mountain: Tales from the Urals, published in 1974 by Frederick Muller Ltd.[7] Riordan heard the tales from a headteacher when he was bedridden in Sverdlovsk. After returning to England he rewrote the tales from memory, checking them against Bazhov’s book. He preferred not to call himself «translator», he believed that «communicator» was more appropriate.[8]

Sources[edit]

Bazhov’s stories are based on the oral lore of the miners and gold prospectors.[9] The character of Silver Hoof is based on the Ural legends. Bazhov mentioned that he had heard tales about the mythical creature Silver Deer, also known as the elk Golden Horns and the goat Silver Hoof.[10] The exact origin of the creature is unknown, but deer have significant roles in the mythology of various peoples located all over the world. In the folklore tales, the goat/deer can be either friendly or harmful.[11] Golden or silver deer/elk became popular at the Urals in the 18th century.[12] According to the Bashkir folklore, dreaming about a goat is a good omen.[12] The Finnic peoples prayed to the Elk.[1] The depictions of the animal were found among Permian bronze casts.[1] While the character of Silver Hoof is in fact based on the legends, the actual storyline was penned by Bazhov.[13]

Publication[edit]

The author heard the tales about the goat with a silver hoof at the Urals from the hunter named Bulatov. The tales seemed to originate from the area where many people were engaged in the searches for chrysolites. But Bazhov had to write the storyline for «Silver Hoof» himself.[13] «Silver Hoof» was completed on 3 August 1938.[13]

The tale was not included in the first edition of The Malachite Box. But, inspired by its success, Bazhov continued working on his stories. The tales «Sinyushka’s Well», «Silver Hoof», and «The Demidov Caftans» were finished before the publication of the collection.[14] It was first published in 1938 in the 2nd volume of Sverdlovsk Publishing House’s Uralsky Sovremennik.[15] It was then released as a part of Sverdlovsk Publishing House’s children’s collection Morozko.[16]

Plot[edit]

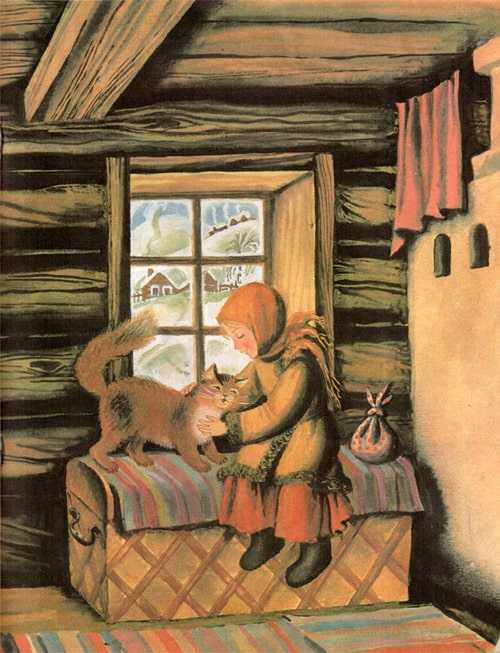

An old man Kokovanya has no family and decides to take an orphan into his house. He finds out that Daryonka (lit. «A gift»), a 6-year-old girl, has recently lost her family and invites her to live with him. She accepts, and when she asks about his profession, he reveals that he works as a gold prospector in summer, and in winter he’s hunting a certain goat in the forests, because he wants «to see where he stamps his right forefoot».[17] Kokovanya, Daryonka and her cat named Muryonka start living together.

Kokovanya works to earn their living, the girl cleans the house and cooks. Winter comes, and Kokovanya decides to go hunting in the forest as usual. He tells Daryonka about the grey goat called Silver Hoof:

That’s a very special goat. On his right forefoot he’s got a silver hoof. And when he stamps with that silver hoof he leaves a gem there. If he stamps once there’s one gem, if he stamps twice there are two, and if he begins to paw the ground there’ll be a whole pile. […] Ordinary goats have two horns, but this one’s got antlers, with five tines.[18]

Unlike other goats’ horns, Silver Hoof’s horns are not shed in winter, and that is how Kokovanya is planning to recognize him. Daryonka begs the old man to take her hunting, and he reluctantly agrees. The cat follows them too. In the forest, Kokovanya goes hunting every day and comes back with a lot of regular goat meat and skins. Soon they have so much meat that Kokovanya has to go back to the village to bring the horse, so that they could carry everything back. He leaves the girl in the forest for a while.

Next morning Daryonka sees Silver Hoof passing by. That night, she sees her cat Muryonka sitting in the glade with the goat in front of her, as if they are communicating. They run about the glade for a long time. Next day Muryonka and the goat are gone, but Kokovanya and Daryonka find a lot of gemstones. «After that people often found stones in the glade where the goat had run about. Most of them were green ones, chrysolites, folks call them.»[19]

Analysis[edit]

Pavel Bazhov indicated that all his stories can be divided into two groups based on tone: «child-toned» (e.g. «The Fire-Fairy») and «adult-toned» (e.g. «The Stone Flower»). He called «Silver Hoof» a «child-toned» story.[20] Such stories have simple plots, children are the main characters, and the mythical creatures help them, typically leading the story to a happy ending.[21]

In Bazhov’s tales chrysolites, unlike ill-omened malachite and emeralds, are meant for humans and bring happiness to their lives. They are «children’s» stones that appear in the «child-toned» stories. Children play with chrysolites in the very first story from The Malachite Box, «Beloved Name». As an amulet, the chrysolite can banish demons, strengthen spiritual resistance, give courage and protect from night terrors. After his «conversation» with the cat, Silver Hoof gives the gemstones as a gift to Daryonka. This gift can be regarded as corporeal and spiritual at the same time, a sacred gift that is bestowed upon good people only.[22] Bazhov himself did not believe that gemstones could bring luck or protect from envy, jealousy and the evil eye.[23]

Bazhov liked the idea of a child together with an old man contacting the mythical creatures. These people are traditionally portrayed as the closest to the otherworldly, but at the same time they are the least reliable narrators in the adult world.[24] The cat Muryonka is a literary creation, not the folklore character, because such insignificant character couldn’t have remained intact in the oral tradition.[1] It is an «intermediary», a linking creature that ties the real world and the mythical world.[25] Cats in the literary tradition cats are often depicted as travellers between worlds.[26]

Adaptations[edit]

A 1947 children’s play of the same name was written by Bazhov and Evgeny Permyak.[27] Mariya Litovskaya criticized Permyak for oversimplifying an already simple story. She commented that he had been obviously trying to create a fun children’s play, and therefore had added a clear antagonist and a lot of secondary characters, such as the fox, the bear, the eagle-owl. Litovskaya said that he had turned the «multilayered tale» into «the tale of friendship between humans and animals, and the battle between good and evil».[28] She also noted that Pavel Bazhov had not been opposed to the changes.[29]

Lyubov Nikolskaya composed the children’s opera Silver Hoof based on the story of the same name in 1959.[30][31]

There is a radio play by Beryl E. Jones.[32]

The 1978 film[edit]

The film Podaryonka (also known as Little Present[33]), based on «Silver Hoof», was a part of the animated film series made at Sverdlovsk Film Studio[33][34] from the early 1970s to early 1980s, on time for the 100th anniversary since the birth of Pavel Bazhov. The series included the following films: Sinyushka’s Well (1973), The Mistress of the Copper Mountain (1975), The Malachite Casket, The Stone Flower (1977), Podaryonka, Golden Hair (1979), and The Grass Hideaway (1982).[35][36][37]

Podaryonka is a stop motion animated film directed by Igor Reznikov, with screenplay by Alexander Rozin.[33] It was narrated by V. Dugin,.[34] The music was composed by Vladislav Kazenin[33] performed by the State Symphony Cinema Orchestra.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Ivanov, Alexei (2004). «Угорский архетип в демонологии сказов Бажова» [The Ugrian Archetype in the Demonology of Bazhov’s Stories]. The Philologist. The Perm State Humanitarian and Pedagogical University (5). ISSN 2076-4154.

- ^ The malachite casket; tales from the Urals, (Book, 1944). WorldCat. OCLC 1998181. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov, Pavel Petrovich; Translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. p. 149. ISBN 9787250005603.

- ^ «Malachite casket : tales from the Urals / P. Bazhov ; [translated from the Russian by Eve Manning ; illustrated by O. Korovin ; designed by A. Vlasova]». The National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Malachite casket; tales from the Urals. (Book, 1950s). WorldCat. OCLC 10874080. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 9.

- ^ «The mistress of the Copper Mountain : tales from the Urals / [collected by] Pavel Bazhov ; [translated and adapted by] James Riordan». Trove. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Lathey, Gillian (July 24, 2015). Translating Children’s Literature. Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 9781317621317.

- ^ Yermakova, G (1976). «Заметки о киноискусстве На передовых рубежах» [The Notes about Cinema At the Outer Frontiers]. Zvezda (11): 204–205.

… сказы Бажова основаны на устных преданиях горнорабочих и старателей, воссоздающих реальную атмосферу того времени.

- ^ Bazhov, Pavel (2014-07-10). У старого рудника [By the Old Mine]. The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 9785457073548.

- ^ Shvabauer 2009, p. 64.

- ^ a b Shvabauer 2009, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Batin 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Batin 1983, p. 8.

- ^ Серебряное копытце [Silver Hoof] (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Rozhdestvenskaya, Yelena (2005). «Moemu neizmenno okryljajushhemu redaktoru: vspominaja Pavla Petrovicha Bazhova» Моему неизменно окрыляющему редактору: вспоминая Павла Петровича Бажова [To my always inspiring editor: remembering Pavel Petrovich Bazhov]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 226.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 237.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 231.

- ^ «Bazhov P. P. The Malachite Box» (in Russian). Bibliogid. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 247.

- ^ Prikazchikova, E. (2003). «Каменная сила медных гор Урала» [The Stone Force of The Ural Copper Mountains] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian) (28): 20–21.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Zherdev, D. V. (2003). «Бинарность как элемент поэтики бажовских сказов» [Binarity as the Poetic Element in Bazhov’s Skazy] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 52.

- ^ Shvabauer 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Shvabauer 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 248.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 252.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 251.

- ^ «Nikolskaya Lyubov Borisovna» (in Russian). The Union of Sverdlovsk Oblast Composers. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Sokolskaya, Zh. «P. P. Bazhov i muzyka Urala П. П. Бажов и музыка Урала [Pavel Bazhov and the Ural music]» in: P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm.

- ^ «Broadcast — BBC Programme Index».

- ^ a b c d «A Little Present». Animator.ru. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ a b «The list of animated films» (in Russian). Soyztelefilm. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ «A Malachite Casket». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Mistress of the Coppery Mountain». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Golden Hair». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

References[edit]

- Bazhov, Pavel (1952). Valentina Bazhova; Alexey Surkov; Yevgeny Permyak (eds.). Sobranie sochinenij v trekh tomakh Собрание сочинений в трех томах [Works. In Three Volumes] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. ISBN 9787250005603.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Eve Manning (1950s). Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Shvabauer, Nataliya (10 January 2009). «Tipologija fantasticheskih personazhej v folklore gornorabochih Zapadnoj Evropy i Rossii» Типология фантастических персонажей в фольклоре горнорабочих Западной Европы и России [The Typology of the Fantastic Characters in the Miners’ Folklore of Western Europe and Russia] (PDF). Dissertation (in Russian). The Ural State University. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Litovskaya, Mariya (2014). «Vzroslyj detskij pisatel Pavel Bazhov: konflikt redaktur» Взрослый детский писатель Павел Бажов: конфликт редактур [The Adult-Children’s Writer Pavel Bazhov: The Conflict of Editing]. Detskiye Chteniya (in Russian). 6 (2): 243–254.

- Batin, Mikhail (1983). «Istorija sozdanija skaza Malahitovaja shkatulka» История создания сказа «Малахитовая шкатулка» [The Malachite Box publication history] (in Russian). The official website of the Polevskoy Town District. Retrieved 30 November 2015.[permanent dead link]

- Nikulina, Maya (2003). «Pro zemelnye dela i pro tajnuju silu. O dalnikh istokakh uralskoj mifologii P.P. Bazhova» Про земельные дела и про тайную силу. О дальних истоках уральской мифологии П.П. Бажова [Of land and the secret force. The distant sources of P.P. Bazhov’s Ural mythology]. Filologichesky Klass (in Russian). Cyberleninka.ru. 9.

- P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm // Tvorchestvo P.P. Bazhova v menjajushhemsja mire П. П. Бажов и социалистический реализм // Творчество П. П. Бажова в меняющемся мире [Pavel Bazhov and socialist realism // The works of Pavel Bazhov in the changing world]. The materials of the inter-university research conference devoted to the 125th birthday (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: The Ural State University. 28–29 January 2004. pp. 18–26.

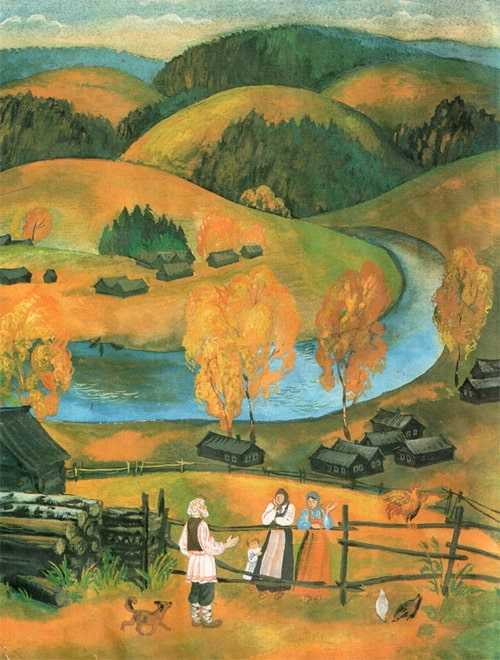

Сказка про деда Кокованю, который взял к себе жить маленькую сиротку-Даренку. Он рассказал девочке сказку про волшебного козла, у которого на правой передней ноге есть серебряное копытце. Когда козел топает этой ножкой, из-под нее самоцветы вылетают.

Серебряное копытце читать

Жил в нашем заводе старик один, по прозвищу Кокованя. Семьи у Коковани не осталось, он и придумал взять в дети сиротку. Спросил у соседей, — не знают ли кого, а соседи и говорят:

— Недавно на Глинке осиротела семья Григория Потопаева. Старших-то девчонок приказчик велел в барскую рукодельню взять, а одну девчоночку по шестому году никому не надо. Вот ты и возьми ее.

— Несподручно мне с девчонкой-то. Парнишечко бы лучше. Обучил бы его своему делу, пособника бы ростить стал. А с девчонкой как? Чему я ее учить-то стану?

Потом подумал-подумал и говорит:

— Знавал я Григорья да и жену его тоже. Оба веселые да ловкие были. Если девчоночка по родителям пойдет, не тоскливо с ней в избе будет. Возьму ее.

Только пойдет ли? Соседи объясняют:

— Плохое житье у нее. Приказчик избу Григорьеву отдал какому-то горюну и велел за это сиротку кормить, пока не подрастет. А у того своя семья больше десятка. Сами не досыта едят. Вот хозяйка и взъедается на сиротку, попрекает ее куском-то. Та хоть маленькая, а понимает. Обидно ей. Как не пойдет от такого житья! Да и уговоришь, поди-ка.

— И то правда, — отвечает Кокованя, — уговорю как-нибудь.

В праздничный день и пришел он к тем людям, у кого сиротка жила. Видит, полна изба народу, больших и маленьких. На голбчике, у печки, девчоночка сидит, а рядом с ней кошка бурая. Девчоночка маленькая, и кошка маленькая и до того худая да ободранная, что редко кто такую в избу пустит. Девчоночка эту кошку гладит, а она до того звонко мурлычет, что по всей избе слышно. Поглядел Кокованя на девчоночку и спрашивает:

— Это у вас Григорьева-то подаренка?

Хозяйка отвечает:

— Она самая. Мало одной-то, так еще кошку драную где-то подобрала. Отогнать не можем. Всех моих ребят перецарапала, да еще корми ее!

Кокованя и говорит:

— Неласковые, видно, твои ребята. У ней вон мурлычет.

Потом и спрашивает у сиротки:

— Ну, как, подаренушка, пойдешь ко мне жить?

Девчоночка удивилась:

— Ты, дедо, как узнал, что меня Даренкой зовут?

— Да так, — отвечает, — само вышло. Не думал, не гадал, нечаянно попал.

— Ты хоть кто? — спрашивает девчоночка.

— Я, — говорит, — вроде охотника. Летом пески промываю, золото добываю, а зимой по лесам за козлом бегаю да все увидеть не могу.

— Застрелишь его?

— Нет, — отвечает Кокованя. — Простых козлов стреляю, а этого не стану. Мне посмотреть охота, в котором месте он правой передней ножкой топнет.

— Тебе на что это?

— А вот пойдешь ко мне жить, так все и расскажу, — ответил Кокованя.

Девчоночке любопытно стало про козла-то узнать. И то видит — старик веселый да ласковый. Она и говорит:

— Пойду. Только ты эту кошку Муренку тоже возьми. Гляди, какая хорошая.

— Про это, — отвечает Кокованя, — что и говорить. Такую звонкую кошку не взять — дураком остаться. Вместо балалайки она у нас в избе будет.

Хозяйка слышит их разговор. Рада-радехонька, что Кокованя сиротку к себе зовет. Стала скорей Даренкины пожитки собирать. Боится, как бы старик не передумал.

Кошка будто тоже понимает весь разговор. Трется у ног-то да мурлычет:

— Пр-равильно придумал. Пр-равильно.

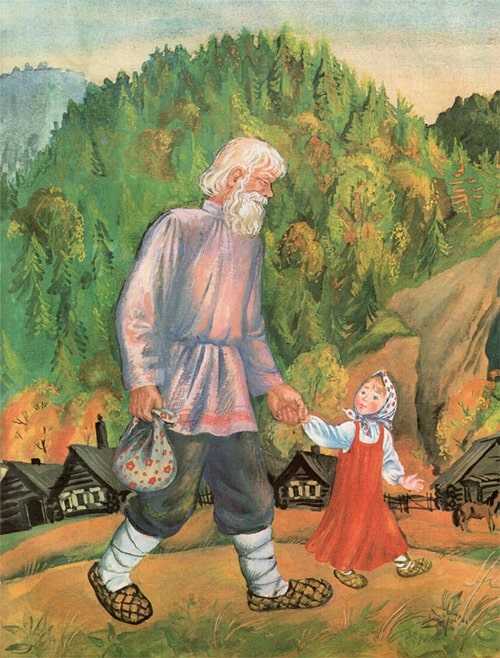

Вот и повел Кокованя сиротку к себе жить. Сам большой да бородатый, а она махонькая и носишко пуговкой. Идут по улице, и кошчонка ободранная за ними попрыгивает.

Так и стали жить вместе дед Кокованя, сиротка Даренка да кошка Муренка.

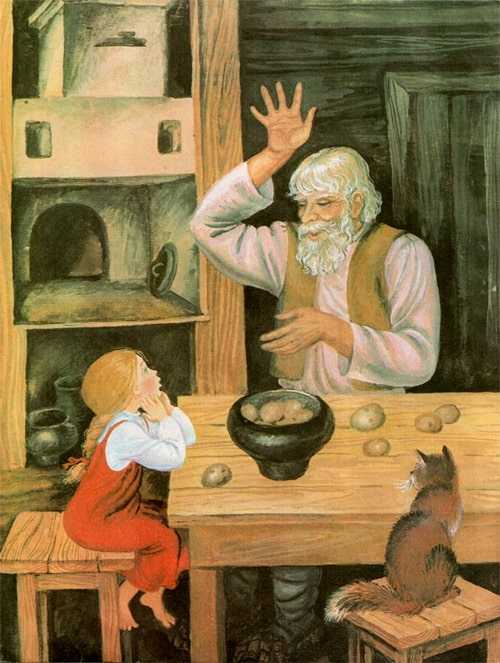

Жили-поживали, добра много не наживали, а на житье не плакались, и у всякого дело было. Кокованя с утра на работу уходил. Даречка в избе прибирала, похлебку да кашу варила, а кошка Муренка на охоту ходила — мышей ловила. К вечеру соберутся, и весело им.

Старик был мастер сказки сказывать, Даренка любила те сказки слушать, а кошка Муренка лежит да мурлычет:

— Пр-равильно говорит. Пр-равильно.

Только после всякой сказки Даренка напомнит:

— Дедо, про козла-то скажи. Какой он?

Кокованя отговаривался сперва, потом и рассказал:

— Тот козел особенный. У него на правой передней ноге серебряное копытце. В каком месте топнет этим копытцем — там и появится дорогой камень. Раз топнет — один камень, два топнет — два камня, а где ножкой бить станет — там груда дорогих камней.

Сказал это, да и не рад стал. С той поры у Дарении только и разговору, что об этом козле.

— Дедо, а он большой?

Рассказал ей Кокованя, что ростом козел не выше стола, ножки тоненькие, головка легонькая. А Даренка опять спрашивает:

— Дедо, а рожки у него есть?

— Рожки-то, — отвечает, — у него отменные. У простых козлов на две веточки, а у него на пять веток.

— Дедо, а он кого ест?

— Никого, — отвечает, — не ест. Травой да листом кормится. Ну, сено тоже зимой в стожках подъедает.

— Дедо, а шерстка у него какая?

— Летом, — отвечает, — буренькая, как вот у Муренки нашей, а зимой серенькая.

— Дедо, а он душной?

Кокованя даже рассердился:

— Какой же душной! Это домашние козлы такие бывают, а лесной козел, он лесом и пахнет.

Стал осенью Кокованя в лес собираться. Надо было ему поглядеть, в которой стороне козлов больше пасется. Даренка и давай проситься:

— Возьми меня, дедо, с собой. Может, я хоть сдалека того козлика увижу. Кокованя и объясняет ей:

— Сдалека-то его не разглядишь. У всех козлов осенью рожки есть. Не разберешь, сколько на них веток. Зимой вот — дело другое. Простые козлы безрогие ходят, а этот, Серебряное копытце, всегда с рожками, хоть летом, хоть зимой. Тогда его сдалека признать можно.

Этим и отговорился. Осталась Даренка дома, а Кокованя в лес ушел. Дней через пять воротился Кокованя домой, рассказывает Даренке:

— Ныне в Полдневской стороне много козлов пасется. Туда и пойду зимой.

— А как же, — спрашивает Даренка, — зимой-то в лесу ночевать станешь?

— Там, — отвечает, — у меня зимний балаган у покосных ложков поставлен. Хороший балаган, с очагом, с окошечком. Хорошо там.

Даренка опять спрашивает:

— Серебряное копытце в той же стороне пасется?

— Кто его знает. Может, и он там. Даренка тут и давай проситься:

— Возьми меня, дедо, с собой. Я в балагане сидеть буду. Может, Серебряное копытце близко подойдет, — я и погляжу.

Старик сперва руками замахал:

— Что ты! Что ты! Статочное ли дело зимой по лесу маленькой девчонке ходить! На лыжах ведь надо, а ты не умеешь. Угрузнешь в снегу-то. Как я с тобой буду? Замерзнешь еще!

Только Даренка никак не отстает:

— Возьми, дедо! На лыжах-то я маленько умею.

Кокованя отговаривал-отговаривал, потом и подумал про себя:

«Сводить разве? Раз побывает, в другой не запросится».

Вот он и говорит:

— Ладно, возьму. Только, чур, в лесу не реветь и домой до времени не проситься.

Как зима в полную силу вошла, стали они в лес собираться. Уложил Кокованя на ручные санки сухарей два мешка, припас охотничий и другое, что ему надо. Даренка тоже узелок себе навязала. Лоскуточков взяла кукле платье шить, ниток клубок, иголку да еще веревку.

«Нельзя ли, — думает, — этой веревкой Серебряное копытце поймать?»

Жаль Даренке кошку свою оставлять, да что поделаешь. Гладит кошку-то на прощанье, разговаривает с ней:

— Мы, Муренка, с дедом в лес пойдем, а ты дома сиди, мышей лови. Как увидим Серебряное копытце, так и воротимся. Я тебе тогда все расскажу.

Кошка лукаво посматривает, а сама мурлычет:

— Пр-равильно придумала. Пр-равильно.

Пошли Кокованя с Даренкой. Все соседи дивуются:

— Из ума выжился старик! Такую маленькую девчонку в лес зимой повел!

Как стали Кокованя с Даренкой из заводу выходить, слышат — собачонки что-то сильно забеспокоились. Такой лай да визг подняли, будто зверя на улицах увидали.

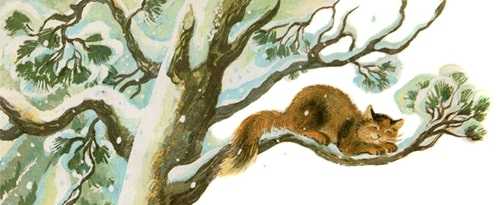

Оглянулись, — а это Муренка серединой улицы бежит, от собак отбивается. Муренка к той поре поправилась. Большая да здоровая стала. Собачонки к ней и подступиться не смеют.

Хотела Даренка кошку поймать да домой унести, только где тебе! Добежала Муренка до лесу, да и на сосну. Пойди поймай!

Покричала Даренка, не могла кошку приманить. Что делать? Пошли дальше.

Глядят, — Муренка стороной бежит. Так и до балагана добралась. Вот и стало их в балагане трое.

Даренка хвалится:

— Веселее так-то.

Кокованя поддакивает:

— Известно, веселее.

А кошка Муренка свернулась клубочком у печки в звонко мурлычет:

— Пр-равильно говоришь. Пр-равильно.

Козлов в ту зиму много было. Это простых-то. Кокованя каждый день то одного, то двух к балагану притаскивал. Шкурок у них накопилось, козлиного мяса насолили — на ручных санках не увезти. Надо бы в завод за лошадью сходить, да как Даренку с кошкой в лесу оставить! А Даренка попривыкла в лесу-то. Сама говорит старику:

— Дедо, сходил бы ты в завод за лошадью. Надо ведь солонину домой перевезти.

Кокованя даже удивился:

— Какая ты у меня разумница, Дарья Григорьевна. Как большая рассудила. Только забоишься, поди, одна-то.

— Чего, — отвечает, — бояться. Балаган у нас крепкий, волкам не добиться. И Муренка со мной. Не забоюсь. А ты поскорее ворочайся все-таки!

Ушел Кокованя. Осталась Даренка с Муренкой. Днем-то привычно было без Коковани сидеть, пока он козлов выслеживал… Как темнеть стало, запобаивалась. Только глядит — Муренка лежит спокойнехонько. Даренка и повеселела. Села к окошечку, смотрит в сторону покосных ложков и видит — по лесу какой-то комочек катится.

Как ближе подкатился, разглядела, — это козел бежит. Ножки тоненькие, головка легонькая, а на рожках по пяти веточек.

Выбежала Даренка поглядеть, а никого нет. Воротилась, да и говорит:

— Видно, задремала я. Мне и показалось.

Муренка мурлычет:

— Пр-равильно говоришь. Пр-равильно.

Легла Даренка рядом с кошкой, да и уснула до утра. Другой день прошел. Не воротился Кокованя. Скучненько стало Даренке, а не плачет. Гладит Муренку да приговаривает:

— Не скучай, Муренушка! Завтра дедо непременно придет.

Муренка свою песенку поет:

— Пр-равильно говоришь. Пр-равильно.

Посидела опять Даренушка у окошка, полюбовалась на звезды. Хотела спать ложиться, вдруг по стенке топоток прошел. Испугалась Даренка, а топоток по другой стене, потом по той, где окошечко, потом где дверка, а там и сверху запостукивало. Не громко, будто кто легонький да быстрый ходит. Даренка и думает:

«Не козел ли тот вчерашний прибежал?» И до того ей захотелось поглядеть, что и страх не держит.

Отворила дверку, глядит, а козел — тут, вовсе близко. Правую переднюю ножку поднял — вот топнет, а на ней серебряное копытце блестит, и рожки у козла о пяти ветках. Даренка не знает, что ей делать, да и манит его как домашнего:

— Ме-ка! Ме-ка!

Козел на это как рассмеялся. Повернулся и побежал.

Пришла Даренушка в балаган, рассказывает Муренке:

— Поглядела я на Серебряное копытце. И рожки видела, и копытце видела. Не видела только, как тот козлик ножкой дорогие камни выбивает. Другой раз, видно, покажет.

Муренка, знай, свою песенку поет:

— Пр-равильно говоришь. Пр-равильно.

Третий день прошел, а все Коковани нет. Вовсе затуманилась Даренка. Слезки запокапывали. Хотела с Муренкой поговорить, а ее нету. Тут вовсе испугалась Даренушка, из балагана выбежала кошку искать.

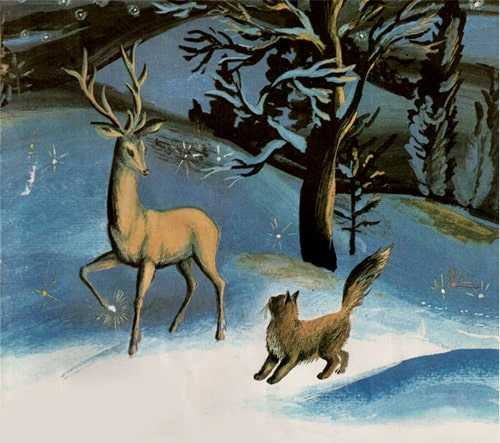

Ночь месячная, светлая, далеко видно. Глядит Даренка — кошка близко на покосном ложке сидит, а перед ней козел. Стоит, ножку поднял, а на ней серебряное копытце блестит.

Муренка головой покачивает, и козел тоже. Будто разговаривают. Потом стали по покосным ложкам бегать. Бежит-бежит козел, остановится и давай копытцем бить. Муренка подбежит, козел дальше отскочит и опять копытцем бьет. Долго они так-то по покосным ложкам бегали. Не видно их стало. Потом опять к самому балагану воротились.

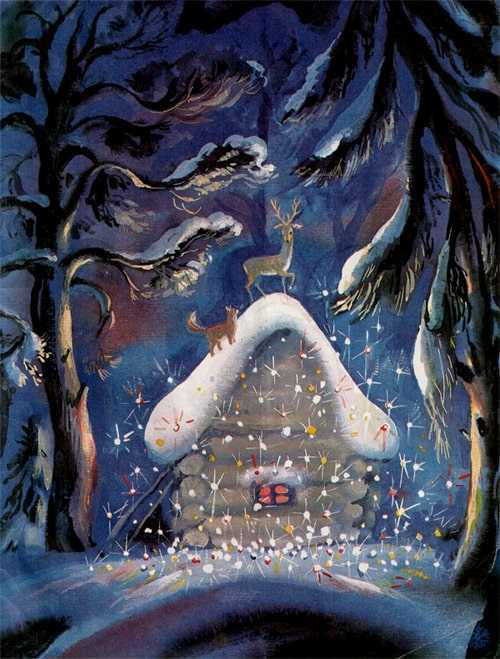

Тут вспрыгнул козел на крышу и давай по ней серебряным копытцем бить. Как искры, из-под ножки-то камешки посыпались. Красные, голубые, зеленые, бирюзовые — всякие.

К этой поре как раз Кокованя и вернулся. Узнать своего балагана не может. Весь он как ворох дорогих камней стал. Так и горит-переливается разными огнями. Наверху козел стоит — и все бьет да бьет серебряным копытцем, а камни сыплются да сыплются. Вдруг Муренка скок туда-же. Встала рядом с козлом, громко мяукнула, и ни Муренки, ни Серебряного копытца не стало.

Кокованя сразу полшапки камней нагреб, да Даренка запросила:

— Не тронь, дедо! Завтра днем еще на это поглядим.

Кокованя и послушался. Только к утру-то снег большой выпал. Все камни и засыпало. Перегребали потом снег-то, да ничего не нашли. Ну, им и того хватило, сколько Кокованя в шапку нагреб.

Все бы хорошо, да Муренки жалко. Больше ее так и не видали, да и Серебряное копытце тоже не показался. Потешил раз, — и будет.

А по тем покосным ложкам, где козел скакал, люди камешки находить стали. Зелененькие больше. Хризолитами называются. Видали?

❤️ 642

🔥 465

😁 470

😢 391

👎 348

🥱 394

Добавлено на полку

Удалено с полки

Достигнут лимит