-

-

Предмет:

Биология

-

Автор:

kinsleyvalencia695

-

Создано:

2 года назад

Ответы

Знаешь ответ? Добавь его сюда!

-

-

Алгебра50 секунд назад

Раскройте скобки и упростите многочлен

-

История1 минута назад

Какое оружие Второй мировой войны вам больше всего симпатизирует?

-

Алгебра5 минут назад

Люди помогите решить номер два, три и четыре, желательно подробно

-

Русский язык5 минут назад

Русский язык, цвета, антонимы.

-

Алгебра5 минут назад

Представьте многочлен в стандартном виде

Информация

Посетители, находящиеся в группе Гости, не могут оставлять комментарии к данной публикации.

Вы не можете общаться в чате, вы забанены.

Чтобы общаться в чате подтвердите вашу почту

Отправить письмо повторно

Вопросы без ответа

-

Математика1 час назад

Из 90 цветов, посаженных в цветнике, принялись 72. На сколько процентов меньше не принявшихся цветов, чем принявшихся?

-

Русский язык1 час назад

Топ пользователей

-

Fedoseewa27

20518

-

Sofka

7417

-

vov4ik329

5115

-

DobriyChelovek

4631

-

olpopovich

3446

-

dobriykaban

2374

-

zlatikaziatik

2275

-

Udachnick

1867

-

Zowe

1683

-

NikitaAVGN

1210

Войти через Google

или

Запомнить меня

Забыли пароль?

У меня нет аккаунта, я хочу Зарегистрироваться

Выберите язык и регион

Русский

Россия

English

United States

How much to ban the user?

1 hour

1 day

В детстве у меня была чудесная книжка с необычайно красивыми иллюстрациями, выполненными в нежнейших изумрудных тонах. Называлась книжка — «Лягушка-Царевна».

Все мы знаем эту сказку чуть ли не наизусть и пересказывать ее сюжет не имеет смысла. Но вот что интересно: в те годы, когда я была ребенком, и в детских книжках, и в мультиках про царевну-лягушку, и даже в детском кинофильме по данному сюжету Царевна — лягушка всегда изображается жертвой Кощея Бессмертного, который хочет на ней ЖЕНИТЬСЯ.

Кощей, несмотря на старость, не прочь обзавестись молоденькой женой, и выбор его падает на Василису Премудрую. Он сватается к ней, получает отказ и жестоко мстит за него, превратив красавицу в лягушку болотную.

Такова предыстория женитьбы Ивана-царевича на лягушке. Именно в таком варианте во времена моего детства преподносились взаимоотношения Кощея и Царевны. Кощей дал Царевне срок в три года, за который она могла одуматься и выйти замуж за Кощея. (Кто же хочет навсегда остаться жительницею болота?)

В планы Кощея вмешалась сама судьба в облике прекрасного и молодого Ивана-царевича…

А вот что на самом деле было написано в русской народной сказке: Кощей Бессмертный был ОТЦОМ Василисы Премудрой! Только недавно, прочитав первоначальный, неизмененный писателями сюжет народной сказки, я с удивлением обнаружила, что сказка на самом-то деле о родительской ревности и зависти! Цитирую: «Василиса Премудрая хитрей-мудрей отца своего, Кощея Бессмертного, уродилась, он за то разгневался на нее и приказал ей три года квакушею быть…»

Как видим, не домогался Бессмертный старик к девице-красавице, а просто был ее самолюбивым отцом-самодуром. Пошто она его умней уродилась? Взыграла в старом отце зависть к мудрости и уму дочери, самолюбие его было чувствительно задето. Вот и все, собственно. Ивану-царевичу пришлось выцарапывать свою женушку из рук своего же тестюшки. Это был ТЕСТЬ, А НЕ СОПЕРНИК! И не сожги Иван раньше времени лягушачью кожу, так и бороться за жену бы не пришлось. Кощей только три года для дочери определил лягушкою быть. А дальше — делай что хошь! Все-таки родное дитятко!

Вот теперь все части пазла и сошлись! А то все детство меня «терзали смутные сомнения»: почему Василиса такая Премудрая, что даже колдовать умеет? Почему, несмотря на все свое могущество и познания в магии, покоряется Кощею и не сбегает от него? Почему Кощей проморгал ее свадьбу с Иваном-царевичем и не помешал их браку, ведь он сам претендует (якобы) на сердце и руку красавицы? Почему он так мягко ее наказал? Ведь мог и навсегда в жабах оставить…

Все становится логичным и понятным, если знать подлинный вариант сказки. Это просто завистливый батюшка немножечко погневался на доченьку, а потом просто вернул ее под родительский кров.

Делов-то на копейку!

Интересно здесь вот что: народ знал, что родители могут завидовать своим отпрыскам. Это было подмечено точно. Психологическая составляющая сказки очень верна.

К тому же в подлинном варианте сказки Василиса Премудрая вовсе не готовила, не ткала и не пряла сама НИЧЕГО. Все задания за нее выполняли ее служанки. Она лишь приказывала им: «Испеките мне к утру такой же хлеб, какой я у своего батюшки в дому ела!» Ее характер облагородили последующими редакциями, выставив ее перед читателями умелой труженицей. А была она на самом деле избалованной доченькой Кощея Бессмертного!

Знали ли вы об этом? Я узнала только недавно.

Милая лягушечка. Красавица!

А вообще, сказка мне нравится во всех вариантах: в народном она психологически правдива, а в последующих обработках — романтична. Какой вариант лучше, решать читателю!

Источник

| The Frog Princess | |

|---|---|

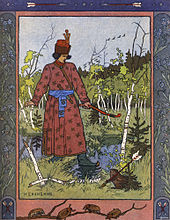

The Frog Tsarevna, Viktor Vasnetsov, 1918 |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Frog Princess |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 402 («The Animal Bride») |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Russian Fairy Tales by Alexander Afanasyev |

| Related |

|

The Frog Princess is a fairy tale that has multiple versions with various origins. It is classified as type 402, the animal bride, in the Aarne–Thompson index.[1] Another tale of this type is the Norwegian Doll i’ the Grass.[2] Russian variants include the Frog Princess or Tsarevna Frog (Царевна Лягушка, Tsarevna Lyagushka)[3] and also Vasilisa the Wise (Василиса Премудрая, Vasilisa Premudraya); Alexander Afanasyev collected variants in his Narodnye russkie skazki.

Synopsis[edit]

The king (or an old peasant woman, in Lang’s version) wants his three sons to marry. To accomplish this, he creates a test to help them find brides. The king tells each prince to shoot an arrow. According to the King’s rules, each prince will find his bride where the arrow lands. The youngest son’s arrow is picked up by a frog. The king assigns his three prospective daughters-in-law various tasks, such as spinning cloth and baking bread. In every task, the frog far outperforms the two other lazy brides-to-be. In some versions, the frog uses magic to accomplish the tasks, and though the other brides attempt to emulate the frog, they cannot perform the magic. Still, the young prince is ashamed of his frog bride until she is magically transformed into a human princess.

In Calvino’s version, the princes use slings rather than bows and arrows. In the Greek version, the princes set out to find their brides one by one; the older two are already married by the time the youngest prince starts his quest. Another variation involves the sons chopping down trees and heading in the direction pointed by them in order to find their brides.[4]

Ivan-Tsarevitch finds the frog in the swamp. Art by Ivan Bilibin

In the Russian versions of the story, Prince Ivan and his two older brothers shoot arrows in different directions to find brides. The other brothers’ arrows land in the houses of the daughters of an aristocrat and a wealthy merchant, respectively. Ivan’s arrow lands in the mouth of a frog in a swamp, who turns into a princess at night. The Frog Princess, named Vasilisa the Wise, is a beautiful, intelligent, friendly, skilled young woman, who was forced to spend three years in a frog’s skin for disobeying Koschei. Her final test may be to dance at the king’s banquet. The Frog Princess sheds her skin, and the prince then burns it, to her dismay. Had the prince been patient, the Frog Princess would have been freed but instead he loses her. He then sets out to find her again and meets with Baba Yaga, whom he impresses with his spirit, asking why she has not offered him hospitality. She tells him that Koschei is holding his bride captive and explains how to find the magic needle needed to rescue his bride. In another version, the prince’s bride flies into Baba Yaga’s hut as a bird. The prince catches her, she turns into a lizard, and he cannot hold on. Baba Yaga rebukes him and sends him to her sister, where he fails again. However, when he is sent to the third sister, he catches her and no transformations can break her free again.

In some versions of the story, the Frog Princess’ transformation is a reward for her good nature. In one version, she is transformed by witches for their amusement. In yet another version, she is revealed to have been an enchanted princess all along.

Analysis[edit]

Tale type[edit]

The Russian tale is classified — and gives its name — to tale type SUS 402, «Russian: Царевна-лягушка, romanized: Tsarevna-lyagushka, lit. ‘Princess-Frog'», of the East Slavic Folktale Catalogue (Russian: СУС, romanized: SUS).[5] According to Lev Barag [ru], the East Slavic type 402 «frequently continues» as type 400: the hero burns the princess’s animal skin and she disappears.[6]

Russian researcher Varvara Dobrovolskaya stated that type SUS 402, «Frog Tsarevna», figures among some of the popular tales of enchanted spouses in the Russian tale corpus.[7] In some Russian variants, as soon as the hero burns the skin of his wife, the Frog Tsarevna, she says she must depart to Koschei’s realm,[8] prompting a quest for her (tale type ATU 400, «The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife»).[9] Jack Haney stated that the combination of types 402, «Animal Bride», and 400, «Quest for the Lost Wife», is a common combination in Russian tales.[10]

Species of animal bride[edit]

Researcher Carole G. Silver states that, apart from bird and fish maidens, the animal bride appears as a frog in Burma, Russia, Austria and Italy; a dog in India and in North America, and a mouse in Sri Lanka.[11]

Professor Anna Angelopoulos noted that the animal wife in the Eastern Mediterranean is a turtle, which is the same animal of Greek variants.[12] In the same vein, Greek scholar Georgios A. Megas [el] noted that similar aquatic beings (seals, sea urchin) and water-related entities (gorgonas, nymphs, neraidas) appear in the Greek oikotype of type 402.[13]

Yolando Pino-Saavedra [es] located the frog, the toad and the monkey as animal brides in variants from the Iberian Peninsula, and from Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking areas in the Americas.[14]

Role of the animal bride[edit]

The tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 402, «The Animal Bride». According to Andreas John, this tale type is considered to be a «male-centered» narrative. However, in East Slavic variants, the Frog Maiden assumes more of a protagonistic role along with her intended.[15] Likewise, scholar Maria Tatar describes the frog heroine as «resourceful, enterprising, and accomplished», whose amphibian skin is burned by her husband, and she has to depart to regions unknown. The story, then, delves into the husband’s efforts to find his wife, ending with a happy reunion for the couple.[16]

On the other hand, Barbara Fass Leavy draws attention to the role of the frog wife in female tasks, like cooking and weaving. It is her exceptional domestic skills that impress her father-in-law and ensure her husband inherits the kingdom.[17]

Maxim Fomin sees «intricate meanings» in the objects the frog wife produces at her husband’s request (a loaf of bread decorated with images of his father’s realm; the carpet depicting the whole kingdom), which Fomin associated with «regal semantics».[18]

A totemic figure?[edit]

Analysing Armenian variants of the tale type where the frog appears as the bride, Armenian scholarship suggests that the frog bride is a totemic figure, and represents a magical disguise of mermaids and magical beings connected to rain and humidity.[19]

Likewise, Russian scholarship (e.g., Vladimir Propp and Yeleazar Meletinsky) has argued for the totemic character of the frog princess.[20] Propp, for instance, described her dance at the court as some sort of «ritual dance»: she waves her arms and forests and lakes appear, and flocks of birds fly about.[21] Charles Fillingham Coxwell [de] also associated these human-animal marriages to totem ancestry, and cited the Russian tale as one example of such.[22]

In his work about animal symbolism in Slavic culture, Russian philologist Aleksandr V. Gura [ru] stated that the frog and the toad are linked to female attributes, like magic and wisdom.[23] In addition, according to ethnologist Ljubinko Radenkovich [sr], the frog and the toad represent liminal creatures that live between land and water realms, and are considered to be imbued with (often negative) magical properties in Slavic folklore.[24] In some variants, the Frog Princess is the daughter of Koschei, the Deathless,[25] and Baba Yaga — sorcerous characters with immense magical power who appear in Slavic folklore in adversarial position. This familial connection, then, seems to reinforce the magical, supernatural origin of the Frog Princess.[26]

Other motifs[edit]

Georgios A. Megas noted two distinctive introductory episodes: the shooting of arrows appears in Greek, Slavic, Turkish, Finnish, Arabic and Indian variants, while following the feathers is a Western European occurrence.[27]

Variants[edit]

Andrew Lang included an Italian variant of the tale, titled The Frog in The Violet Fairy Book.[28] Italo Calvino included another Italian variant from Piedmont, The Prince Who Married a Frog, in Italian Folktales,[29] where he noted that the tale was common throughout Europe.[30] Georgios A. Megas included a Greek variant, The Enchanted Lake, in Folktales of Greece.[31]

In a variant from northern Moldavia collected and published by Romanian author Elena Niculiță-Voronca, the bride selection contest replaces the feather and arrow for shooting bullets, and the frog bride commands the elements (the wind, the rain and the frost) to fulfill the three bridal tasks.[32]

Russia[edit]

The oldest attestation of the tale type in Russia is in a 1787 compilation of fairy tales, published by one Petr Timofeev.[33] In this tale, titled «Сказка девятая, о лягушке и богатыре» (English: «Tale nr. 9: About the frog and the bogatyr»), a widowed king has three sons, and urges them to find wives by shooting three arrows at random, and to marry whoever they find on the spot the arrows land on. The youngest son, Ivan Bogatyr, shoots his, and it takes him some time to find it again. He walks through a vast swamp and finds a large hut, with a large frog inside, holding his arrow. The frog presses Ivan to marry it, lest he will not leave the swamp. Ivan agrees, and it takes off the frog skin to become a beautiful maiden. Later, the king asks his daughters-in-law to weave him a fine linen shirt and a beautiful carpet with gold, silver and silk, and finally to bake him delicious bread. Ivan’s frog wife summons the winds to help her in both sewing tasks. Lastly, the king invites his daughters-in-law to the palace, and the frog wife takes off the frog skin, leaves it at home and goes on a golden carriage. While she dances and impresses the court, Ivan goes back home and burns her frog skin. The maiden realizes her husband’s folly and, saying her name is Vasilisa the Wise, tells him she will vanish to a distant kingdom and begs him to find her.[34]

Czech Republic[edit]

In a Czech variant translated by Jeremiah Curtin, The Mouse-Hole, and the Underground Kingdom, prince Yarmil and his brothers are to seek wives and bring to the king their presents in a year and a day. Yarmil and his brothers shoot arrow to decide their fates, Yarmil’s falls into a mouse-hole. The prince enters the mouse hole, finds a splendid castle and an ugly toad he must bathe for a year and a day. When the date is through, he returns to his father with the toad’s magnificent present: a casket with a small mirror inside. This repeats two more times: on the second year, Yarmil brings the princess’s portrait and on the third year the princess herself. She reveals she was the toad, changed into amphibian form by an evil wizard, and that Yarmil helped her break this curse, on the condition that he must never reveal her cursed state to anyone, specially to his mother. He breaks this prohibition one night and she disappears. Yarmil, then, goes on a quest for her all the way to the glass mountain (tale type ATU 400, «The Quest for the Lost Wife»).[35]

Ukraine[edit]

In a Ukrainian variant collected by M. Dragomanov, titled «Жена-жаба» («The Frog Wife» or «The Frog Woman»), a king shoots three bullets to three different locations, the youngest son follows and finds a frog. He marries it and discovers it is a beautiful princess. After he burns the frog skin, she disappears, and the prince must seek her.[36]

In another Ukrainian variant, the Frog Princess is a maiden named Maria, daughter of the Sea Tsar and cursed into frog form. The tale begins much the same: the three arrows, the marriage between human prince and frog and the three tasks. When the human tsar announces a grand ball to which his sons and his wives are invited, Maria takes off her frog skin to appear as human. While she is in the tsar’s ballroom, her husband hurries back home and burns the frog skin. When she comes home, she reveals the prince her cursed state would soon be over, says he needs to find Baba Yaga in a remote kingdom, and vanishes from sight in the form of a cuckoo. The tale continues as tale type ATU 313, «The Magical Flight», like the Russian tale of The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise.[37]

Finland[edit]

Finnish author Eero Salmelainen [fi] collected a Finnish tale with the title Sammakko morsiamena (English: «The Frog Bride»), and translated into French as Le Cendrillon et sa fiancée, la grenouille («The Male Cinderella and his bride, the frog»). In this tale, a king has three sons, the youngest named Tuhkimo (a male Cinderella; from Finnish tuhka, «ashes»). One day, the king organizes a bride selection test for his sons: they are to aim his bows and shoot arrows at random directions, and marry the woman that they will find with the arrow. Tuhkimo’s arrow lands near a frog and he takes it as his bride. The king sets three tasks for his prospective daughters-in-law: to prepare the food and to sew garments. While prince Tuhkimo is aleep, his frog fiancée takes off her frog skin, becomes a human maiden and summons her eight sisters to her house: eight swans fly in through the window, take off their swanskins and become humans. Tuhkimo discovers his bride’s transformation and burns the amphibian skin. The princess laments the fact, since her mother cursed her and her eight sisters, and in three nights time the curse would have been lifted. The princess then changes into a swan and flies away with her swan sisters. Tuhkimo follows her and meets an old widow, who directs him to a lake, in three days journey. Tuhkimo finds the lake, and he waits. Nine swans come, take off their skins to become human women and bathe in the lake. Tuhkimo hides his bride’s swanskin. She comes out of the water and cannot find her swanskin. Tuhkimo appears to her and she tells him he must come to her father’s palace and identify her among her sisters.[38][39]

Azerbaijan[edit]

In the Azerbaijani version of the fairy tale, the princes do not shoot arrows to choose their fiancées, they hit girls with apples.[40] And indeed, there was such a custom among the Mongols living in the territory of present-day Azerbaijan in the 17th century.[41]

Poland[edit]

In a Polish from Masuria collected by Max Toeppen with the title Die Froschprinzessin («The Frog Princess»), a landlord has three sons, the elder two smart and the youngest, Hans (Janek in the Polish text), a fool. One day, the elder two decide to leave home to learn a trade and find wives, and their foolish little brother wants to do so. The two elders and Hans go their separate ways in a crossroads, and Hans loses his way in the woods, without food, and the berries of the forest not enough to sate his hunger. Luckily for him, he finds a hut in the distance, where a little frog lives. Hans tells the little animal he wants to find work, and the frog agrees to hire him, his only job is to carry the frog on a satin pillow, and he shall have drink and food. One day, the youth sighs that his brothers are probably returning home with gifts for their mother, and he has none to show them. The little frog tells Hans to sleep and, in the next morning, to knock three times on the stable door with a wand; he will find a beautiful horse he can ride home, and a little box. Hans goes back home with the horse and gives the little box to his mother; inside, a beautiful dress of gold and diamond buttons. Hans’s brothers question the legitimate origin of the dress. Some time later, the brothers go back to their masters and promise to return with their brides. Hans goes back to the little frog’s hut and mopes that his brother have bride to introduce to his family, while he has the frog. The frog tells him not to worry, and to knock on the stable again. Hans does that and a carriage appears with a princess inside, who is the frog herself. The princess asks Hans to take her to his parents, but not let her put anything on her mouth during dinner. Hans and the princess go to his parents’ house, and he fulfills the princess’s request, despite some grievaance from his parents and brothers. Finally, the princess turns back into a frog and tells Hans he has a last challenge before he redeems her: Hans will have to face three nights of temptations, dance, music and women in the first; counts and nobles who wish to crown him king in the second; and executioners who wish to kill him in the third. Hans endures and braves each night, awakening in the fourth day in a large castle. The princess, fully redeemed, tells him the castle is theirs, and she is his wife.[42]

In another Polish tale, collected by collector Antoni Józef Gliński [pl] and translated into English by translator Maude Ashurst Biggs as The Frog Princess, a king wishes to see his three sons married before they eventually ascend to the throne. So, the next day, the princes prepare to shoot three arrows at random, and to marry the girls that live wherever the arrows land. The first two find human wives, while the youngest’s arrow falls in the margins of the lake. A frog, sat on it, agrees to return the prince’s arrow, in exchange for becoming his wife. The prince questions the frog’s decision, but she advises him to tell his family he married an Eastern lady who must be only seen by her beloved. Eventually, the king asks his sons to bring him carpet woven by his daughters-in-law. The little frog summons «seven lovely maidens» to help her weave the carpet. Next, the king asks for a cake to be baked by his daughters-in-law, and the little frog bakes a delicious cake for the king. Surprised by the frog’s hidden talents, the prince asks her about them, and she reveals she is, in fact, a princess underneath the frog skin, a disguise created by her mother, the magical Queen of Light, to keep her safe from her enemies. The king then summons his sons and his daughters-in-law for a banquet at the palace. The little frog tells the prince to go first, and, when his father asks about her, it will begin to rain; when it lightens, he is to tell her she is adorning herself; and when it thunders, she is coming to the palace. It happens thus, and the prince introduces his bride to his father, and whispers in his ear about the frogskin. The king suggests his son burns the frogskin. The prince follows through with the suggestion and tells his bride about it. The princess cries bitter tears and, while he is asleep, turns into a duck and flies away. The prince wakes the next morning and begins a quest to find the kingdom of the Queen of Light. In his quest, he passes by the houses of three witches named Jandza, which spin on chicken legs. Each of the Jandzas tells him that the princess flies in their huts in duck form, and the prince must hide himself to get her back. He fails in the first two houses, due to her shapeshifting into other animals to escape, but gets her in the third. They reconcile and return to his father’s kingdom.[43]

Other regions[edit]

Researchers Nora Marks Dauenhauer and Richard L. Dauenhauer found a variant titled Yuwaan Gagéets, heard during Nora’s childhood from a Tlingit storyteller. They identified the tale as belonging to the tale type ATU 402 (and a second part as ATU 400, «The Quest for the Lost Wife») and noted its resemblance to the Russian story, trying to trace its appearance in the teller’s repertoire.[44]

Adaptations[edit]

- A literary treatment of the tale was published as The Wise Princess (A Russian Tale) in The Blue Rose Fairy Book (1911), by Maurice Baring.[45]

- A translation of the story by illustrator Katherine Pyle was published with the title The Frog Princess (A Russian Story).[46]

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1939 Soviet film directed by Aleksandr Rou, is based on this plot. It was the first large-budget feature in the Soviet Union to use fantasy elements, as opposed to the realistic style long favored politically.[47]

- In 1953 the director Mikhail Tsekhanovsky had the idea of animating this popular national fairy tale. Production took two years, and the premiere took place in December, 1954. At present the film is included in the gold classics of «Soyuzmultfilm».

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1977 Soviet animated film is also based on this fairy tale.

- In 1996, an animated Russian version based on an in-depth version of the tale in the film «Classic Fairy Tales From Around the World» on VHS. This version tells of how the beautiful Princess Vasilisa was kidnapped and cursed by the evil wizard Kashay to make her his bride and only the love of the handsome Prince Ivan can free her.

- Taking inspiration from the Russian story, Vasilisa appears to assist Hellboy against Koschei in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls.

- The Frog Princess was featured in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, where it was depicted in a country setting. The episode features the voice talents of Jasmine Guy as Frog Princess Lylah, Greg Kinnear as Prince Gavin, Wallace Langham as Prince Bobby, Mary Gross as Elise, and Beau Bridges as King Big Daddy.

- A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék («Hungarian Folk Tales») (hu), with the title Marci és az elátkozott királylány («Martin and the Cursed Princess»).

- «Wildwood Dancing,» a 2007 fantasy novel by Juliet Marillier, expands the princess and the frog theme.[48]

Culture[edit]

Music

The Divine Comedy’s 1997 single The Frog Princess is loosely based on the theme of the original Frog Princess story, interwoven with the narrator’s personal experiences.

See also[edit]

- The Frog Prince

- The Princess and the Frog

- Vasilisa (name)

- Puddocky

References[edit]

- ^ Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 224, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ D. L. Ashliman, «Animal Brides: folktales of Aarne–Thompson type 402 and related stories»

- ^

Works related to The Frog-Tzarevna at Wikisource

- ^ Out of the Everywhere: New Tales for Canada, Jan Andrews

- ^ Barag, Lev. «Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка». Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 128.

- ^ Barag, Lev. «Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка». Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 128.

- ^ Dobrovolskaya, Varvara. «PLOT No. 425A OF COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS (“CUPID AND PSYCHE”) IN RUSSIAN FOLK-TALE TRADITION». In: Traditional culture. 2017. Vol. 18. № 3 (67). p. 139.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA — Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- ^ Kobayashi, Fumihiko (2007). «The Forbidden Love in Nature. Analysis of the «Animal Wife» Folktale in Terms of Content Level, Structural Level, and Semantic Level». Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore. 36: 144–145. doi:10.7592/FEJF2007.36.kobayashi.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 548. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Silver, Carole G. «Animal Brides and Grooms: Marriage of Person to Animal Motif B600, and Animal Paramour, Motif B610». In: Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (eds.). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. A Handbook. Armonk / London: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. p. 94.

- ^ Angelopoulos, Anna. «La fille de Thalassa». In: ELO N. 11/12 (2005): 17 (footnote nr. 5), 29 (footnote nr. 47). http://hdl.handle.net/10400.1/1607

- ^ Angelopoulou, Anna; Broskou, Aigle. «ΕΠΕΞΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ ΠΑΡΑΜΥΘΙΑΚΩΝ ΤΥΠΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΡΑΛΛΑΓΩΝ AT 300-499». Tome B: AT 400-499. Athens, Greece: ΚΕΝΤΡΟ ΝΕΟΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ Ε.Ι.Ε. 1999. p. 540.

- ^ Pino Saavedra, Yolando. Folktales of Chile. [Chicago:] University of Chicago Press, 1967. p. 258.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, Criticism. Norton Critical Edition. Norton, 1999. p. 31. ISBN 9780393972771

- ^ Leavy, Barbara Fass. In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender. NYU Press, 1994. pp. 204, 207, 212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.9.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. «The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions». In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 259-268. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- ^ Hayrapetyan Tamar. «Combinaisons archétipales dans les epopees orales et les contes merveilleux armeniens». Traduction par Léon Ketcheyan. In: Revue des etudes Arméniennes tome 39 (2020). pp. 499-500 and footnote nr. 141.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. «The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions». In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 259 (footnote nr. 9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- ^ Propp, V. Theory and history of folklore. Theory and history of literature v. 5. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. p. 143. ISBN 0-8166-1180-7.

- ^ Coxwell, C. F. Siberian And Other Folk Tales. London: The C. W. Daniel Company, 1925. p. 252.

- ^ Гура, Александр Викторович. «Символика животных в славянской народной традиции» [Animal Symbolism in Slavic folk traditions]. М: Индрик, 1997. pp. 380-382. ISBN 5-85759-056-6.

- ^ Radenkovic, Ljubinko. «Митолошки елементи у словенским народним представама о жаби» [Mythological Elements in Slavic Notions of Frogs]. In: Заједничко у словенском фолклору: зборник радова [Common Elements in Slavic Folklore: Collected Papers, 2012]. Београд: Балканолошки институт САНУ, 2012. pp. 379-397. ISBN 978–86–7179-074–1 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: invalid character.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. «The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions». In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 260. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- ^ Kovalchuk Lidia Petrovna (2015). «Comparative research of blends frog-woman and toad-woman in Russian and English folktales». In: Russian Linguistic Bulletin, (3 (3)), 14-15. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/comparative-research-of-blends-frog-woman-and-toad-woman-in-russian-and-english-folktales (дата обращения: 17.11.2021).

- ^ Megas, Geōrgios A. Folktales of Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970. p. 224.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Violet Fairy Book, «The Frog»

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 438 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 718 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 49, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ Ciubotaru, Silvia. «Elena Niculiţă-Voronca şi basmele fantastice» [Elena Niculiţă-Voronca and the Fantastic Fairy Tales]. In: Anuarul Muzeului Etnografic al Moldovei [The Yearly Review of the Ethnographic Museum of Moldavia] 18/2018. p. 158. ISSN 1583-6819.

- ^ Barag, Lev. «Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка». Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. pp. 46 (source), 128 (entry).

- ^ Русские сказки в ранних записях и публикациях». Л.: Наука, 1971. pp. 203-213.

- ^ Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1890. pp. 331–355.

- ^ Драгоманов, М (M. Dragomanov).»Малорусские народные предания и рассказы». 1876. pp. 313-317.

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 179-181. ISBN 9781576070635.

- ^ Salmelainen, Eero. Suomen kansan satuja ja tarinoita. II Osa. Helsingissä: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. 1871. pp. 118–127.

- ^ Beauvois, Eugéne. Contes populaires de la Norvège, de la Finlande & de la Bourgogne, etc. Paris: E. Dentu, Éditeur. 1862. pp. 180–193.

- ^ «Царевич и лягушка». Фольклор Азербайджана и прилегающих стран. Vol. 1. Баку: Изд-во АзГНИИ. Азербайджанский государственный научно-исследовательский ин-т, Отд-ние языка, литературы и искусства (под ред. А. В. Багрия). 1930. pp. 30–33.

- ^ Челеби Э. (1983). «Описание крепости Шеки/О жизни племени ит-тиль». Книга путешествия. (Извлечения из сочинения турецкого путешественника ХVII века). Вып. 3. Земли Закавказья и сопредельных областей Малой Азии и Ирана. Москва: Наука. p. 159.

- ^ Toeppen, Max. Aberglauben aus Masuren, mit einem Anhange, enthaltend: Masurische Sagen und Mährchen. Danzig: Th. Bertling, 1867. pp. 158-162.

- ^ Polish Fairy Tales. Translated from A. J. Glinski by Maude Ashurst Biggs. New York: John Lane Company. 1920. pp. 1-15.

- ^ Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Dauenhauer, Richard L. «Tracking “Yuwaan Gagéets”: A Russian Fairy Tale in Tlingit Oral Tradition». In: Oral Tradition, 13/1 (1998): 58-91.

- ^ Baring, Maurice. The Blue Rose Fairy Book. New York: Maude, Dodd and Company. 1911. pp. 247-260.

- ^ Pyle, Katherine. Tales of folk and fairies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1919. pp. 137-158.

- ^ James Graham, Baba Yaga in Film[Usurped!]

- ^ https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/13929.Wildwood_Dancing

External links[edit]

- The Frog Princess on YouTube

- The Wise Princess (The Blue Rose Fairy Book) from Project Gutenberg

- The Frog Princess (Ukrainian Folk Tale)

- The Frog Princess (Polish Folk Tale)

- The Frog Princess (Chinese Folk Tale)

| The Frog Princess | |

|---|---|

The Frog Tsarevna, Viktor Vasnetsov, 1918 |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Frog Princess |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 402 («The Animal Bride») |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Russian Fairy Tales by Alexander Afanasyev |

| Related |

|

The Frog Princess is a fairy tale that has multiple versions with various origins. It is classified as type 402, the animal bride, in the Aarne–Thompson index.[1] Another tale of this type is the Norwegian Doll i’ the Grass.[2] Russian variants include the Frog Princess or Tsarevna Frog (Царевна Лягушка, Tsarevna Lyagushka)[3] and also Vasilisa the Wise (Василиса Премудрая, Vasilisa Premudraya); Alexander Afanasyev collected variants in his Narodnye russkie skazki.

Synopsis[edit]

The king (or an old peasant woman, in Lang’s version) wants his three sons to marry. To accomplish this, he creates a test to help them find brides. The king tells each prince to shoot an arrow. According to the King’s rules, each prince will find his bride where the arrow lands. The youngest son’s arrow is picked up by a frog. The king assigns his three prospective daughters-in-law various tasks, such as spinning cloth and baking bread. In every task, the frog far outperforms the two other lazy brides-to-be. In some versions, the frog uses magic to accomplish the tasks, and though the other brides attempt to emulate the frog, they cannot perform the magic. Still, the young prince is ashamed of his frog bride until she is magically transformed into a human princess.

In Calvino’s version, the princes use slings rather than bows and arrows. In the Greek version, the princes set out to find their brides one by one; the older two are already married by the time the youngest prince starts his quest. Another variation involves the sons chopping down trees and heading in the direction pointed by them in order to find their brides.[4]

Ivan-Tsarevitch finds the frog in the swamp. Art by Ivan Bilibin

In the Russian versions of the story, Prince Ivan and his two older brothers shoot arrows in different directions to find brides. The other brothers’ arrows land in the houses of the daughters of an aristocrat and a wealthy merchant, respectively. Ivan’s arrow lands in the mouth of a frog in a swamp, who turns into a princess at night. The Frog Princess, named Vasilisa the Wise, is a beautiful, intelligent, friendly, skilled young woman, who was forced to spend three years in a frog’s skin for disobeying Koschei. Her final test may be to dance at the king’s banquet. The Frog Princess sheds her skin, and the prince then burns it, to her dismay. Had the prince been patient, the Frog Princess would have been freed but instead he loses her. He then sets out to find her again and meets with Baba Yaga, whom he impresses with his spirit, asking why she has not offered him hospitality. She tells him that Koschei is holding his bride captive and explains how to find the magic needle needed to rescue his bride. In another version, the prince’s bride flies into Baba Yaga’s hut as a bird. The prince catches her, she turns into a lizard, and he cannot hold on. Baba Yaga rebukes him and sends him to her sister, where he fails again. However, when he is sent to the third sister, he catches her and no transformations can break her free again.

In some versions of the story, the Frog Princess’ transformation is a reward for her good nature. In one version, she is transformed by witches for their amusement. In yet another version, she is revealed to have been an enchanted princess all along.

Analysis[edit]

Tale type[edit]

The Russian tale is classified — and gives its name — to tale type SUS 402, «Russian: Царевна-лягушка, romanized: Tsarevna-lyagushka, lit. ‘Princess-Frog'», of the East Slavic Folktale Catalogue (Russian: СУС, romanized: SUS).[5] According to Lev Barag [ru], the East Slavic type 402 «frequently continues» as type 400: the hero burns the princess’s animal skin and she disappears.[6]

Russian researcher Varvara Dobrovolskaya stated that type SUS 402, «Frog Tsarevna», figures among some of the popular tales of enchanted spouses in the Russian tale corpus.[7] In some Russian variants, as soon as the hero burns the skin of his wife, the Frog Tsarevna, she says she must depart to Koschei’s realm,[8] prompting a quest for her (tale type ATU 400, «The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife»).[9] Jack Haney stated that the combination of types 402, «Animal Bride», and 400, «Quest for the Lost Wife», is a common combination in Russian tales.[10]

Species of animal bride[edit]

Researcher Carole G. Silver states that, apart from bird and fish maidens, the animal bride appears as a frog in Burma, Russia, Austria and Italy; a dog in India and in North America, and a mouse in Sri Lanka.[11]

Professor Anna Angelopoulos noted that the animal wife in the Eastern Mediterranean is a turtle, which is the same animal of Greek variants.[12] In the same vein, Greek scholar Georgios A. Megas [el] noted that similar aquatic beings (seals, sea urchin) and water-related entities (gorgonas, nymphs, neraidas) appear in the Greek oikotype of type 402.[13]

Yolando Pino-Saavedra [es] located the frog, the toad and the monkey as animal brides in variants from the Iberian Peninsula, and from Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking areas in the Americas.[14]

Role of the animal bride[edit]

The tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 402, «The Animal Bride». According to Andreas John, this tale type is considered to be a «male-centered» narrative. However, in East Slavic variants, the Frog Maiden assumes more of a protagonistic role along with her intended.[15] Likewise, scholar Maria Tatar describes the frog heroine as «resourceful, enterprising, and accomplished», whose amphibian skin is burned by her husband, and she has to depart to regions unknown. The story, then, delves into the husband’s efforts to find his wife, ending with a happy reunion for the couple.[16]

On the other hand, Barbara Fass Leavy draws attention to the role of the frog wife in female tasks, like cooking and weaving. It is her exceptional domestic skills that impress her father-in-law and ensure her husband inherits the kingdom.[17]

Maxim Fomin sees «intricate meanings» in the objects the frog wife produces at her husband’s request (a loaf of bread decorated with images of his father’s realm; the carpet depicting the whole kingdom), which Fomin associated with «regal semantics».[18]

A totemic figure?[edit]

Analysing Armenian variants of the tale type where the frog appears as the bride, Armenian scholarship suggests that the frog bride is a totemic figure, and represents a magical disguise of mermaids and magical beings connected to rain and humidity.[19]

Likewise, Russian scholarship (e.g., Vladimir Propp and Yeleazar Meletinsky) has argued for the totemic character of the frog princess.[20] Propp, for instance, described her dance at the court as some sort of «ritual dance»: she waves her arms and forests and lakes appear, and flocks of birds fly about.[21] Charles Fillingham Coxwell [de] also associated these human-animal marriages to totem ancestry, and cited the Russian tale as one example of such.[22]

In his work about animal symbolism in Slavic culture, Russian philologist Aleksandr V. Gura [ru] stated that the frog and the toad are linked to female attributes, like magic and wisdom.[23] In addition, according to ethnologist Ljubinko Radenkovich [sr], the frog and the toad represent liminal creatures that live between land and water realms, and are considered to be imbued with (often negative) magical properties in Slavic folklore.[24] In some variants, the Frog Princess is the daughter of Koschei, the Deathless,[25] and Baba Yaga — sorcerous characters with immense magical power who appear in Slavic folklore in adversarial position. This familial connection, then, seems to reinforce the magical, supernatural origin of the Frog Princess.[26]

Other motifs[edit]

Georgios A. Megas noted two distinctive introductory episodes: the shooting of arrows appears in Greek, Slavic, Turkish, Finnish, Arabic and Indian variants, while following the feathers is a Western European occurrence.[27]

Variants[edit]

Andrew Lang included an Italian variant of the tale, titled The Frog in The Violet Fairy Book.[28] Italo Calvino included another Italian variant from Piedmont, The Prince Who Married a Frog, in Italian Folktales,[29] where he noted that the tale was common throughout Europe.[30] Georgios A. Megas included a Greek variant, The Enchanted Lake, in Folktales of Greece.[31]

In a variant from northern Moldavia collected and published by Romanian author Elena Niculiță-Voronca, the bride selection contest replaces the feather and arrow for shooting bullets, and the frog bride commands the elements (the wind, the rain and the frost) to fulfill the three bridal tasks.[32]

Russia[edit]

The oldest attestation of the tale type in Russia is in a 1787 compilation of fairy tales, published by one Petr Timofeev.[33] In this tale, titled «Сказка девятая, о лягушке и богатыре» (English: «Tale nr. 9: About the frog and the bogatyr»), a widowed king has three sons, and urges them to find wives by shooting three arrows at random, and to marry whoever they find on the spot the arrows land on. The youngest son, Ivan Bogatyr, shoots his, and it takes him some time to find it again. He walks through a vast swamp and finds a large hut, with a large frog inside, holding his arrow. The frog presses Ivan to marry it, lest he will not leave the swamp. Ivan agrees, and it takes off the frog skin to become a beautiful maiden. Later, the king asks his daughters-in-law to weave him a fine linen shirt and a beautiful carpet with gold, silver and silk, and finally to bake him delicious bread. Ivan’s frog wife summons the winds to help her in both sewing tasks. Lastly, the king invites his daughters-in-law to the palace, and the frog wife takes off the frog skin, leaves it at home and goes on a golden carriage. While she dances and impresses the court, Ivan goes back home and burns her frog skin. The maiden realizes her husband’s folly and, saying her name is Vasilisa the Wise, tells him she will vanish to a distant kingdom and begs him to find her.[34]

Czech Republic[edit]

In a Czech variant translated by Jeremiah Curtin, The Mouse-Hole, and the Underground Kingdom, prince Yarmil and his brothers are to seek wives and bring to the king their presents in a year and a day. Yarmil and his brothers shoot arrow to decide their fates, Yarmil’s falls into a mouse-hole. The prince enters the mouse hole, finds a splendid castle and an ugly toad he must bathe for a year and a day. When the date is through, he returns to his father with the toad’s magnificent present: a casket with a small mirror inside. This repeats two more times: on the second year, Yarmil brings the princess’s portrait and on the third year the princess herself. She reveals she was the toad, changed into amphibian form by an evil wizard, and that Yarmil helped her break this curse, on the condition that he must never reveal her cursed state to anyone, specially to his mother. He breaks this prohibition one night and she disappears. Yarmil, then, goes on a quest for her all the way to the glass mountain (tale type ATU 400, «The Quest for the Lost Wife»).[35]

Ukraine[edit]

In a Ukrainian variant collected by M. Dragomanov, titled «Жена-жаба» («The Frog Wife» or «The Frog Woman»), a king shoots three bullets to three different locations, the youngest son follows and finds a frog. He marries it and discovers it is a beautiful princess. After he burns the frog skin, she disappears, and the prince must seek her.[36]

In another Ukrainian variant, the Frog Princess is a maiden named Maria, daughter of the Sea Tsar and cursed into frog form. The tale begins much the same: the three arrows, the marriage between human prince and frog and the three tasks. When the human tsar announces a grand ball to which his sons and his wives are invited, Maria takes off her frog skin to appear as human. While she is in the tsar’s ballroom, her husband hurries back home and burns the frog skin. When she comes home, she reveals the prince her cursed state would soon be over, says he needs to find Baba Yaga in a remote kingdom, and vanishes from sight in the form of a cuckoo. The tale continues as tale type ATU 313, «The Magical Flight», like the Russian tale of The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise.[37]

Finland[edit]

Finnish author Eero Salmelainen [fi] collected a Finnish tale with the title Sammakko morsiamena (English: «The Frog Bride»), and translated into French as Le Cendrillon et sa fiancée, la grenouille («The Male Cinderella and his bride, the frog»). In this tale, a king has three sons, the youngest named Tuhkimo (a male Cinderella; from Finnish tuhka, «ashes»). One day, the king organizes a bride selection test for his sons: they are to aim his bows and shoot arrows at random directions, and marry the woman that they will find with the arrow. Tuhkimo’s arrow lands near a frog and he takes it as his bride. The king sets three tasks for his prospective daughters-in-law: to prepare the food and to sew garments. While prince Tuhkimo is aleep, his frog fiancée takes off her frog skin, becomes a human maiden and summons her eight sisters to her house: eight swans fly in through the window, take off their swanskins and become humans. Tuhkimo discovers his bride’s transformation and burns the amphibian skin. The princess laments the fact, since her mother cursed her and her eight sisters, and in three nights time the curse would have been lifted. The princess then changes into a swan and flies away with her swan sisters. Tuhkimo follows her and meets an old widow, who directs him to a lake, in three days journey. Tuhkimo finds the lake, and he waits. Nine swans come, take off their skins to become human women and bathe in the lake. Tuhkimo hides his bride’s swanskin. She comes out of the water and cannot find her swanskin. Tuhkimo appears to her and she tells him he must come to her father’s palace and identify her among her sisters.[38][39]

Azerbaijan[edit]

In the Azerbaijani version of the fairy tale, the princes do not shoot arrows to choose their fiancées, they hit girls with apples.[40] And indeed, there was such a custom among the Mongols living in the territory of present-day Azerbaijan in the 17th century.[41]

Poland[edit]

In a Polish from Masuria collected by Max Toeppen with the title Die Froschprinzessin («The Frog Princess»), a landlord has three sons, the elder two smart and the youngest, Hans (Janek in the Polish text), a fool. One day, the elder two decide to leave home to learn a trade and find wives, and their foolish little brother wants to do so. The two elders and Hans go their separate ways in a crossroads, and Hans loses his way in the woods, without food, and the berries of the forest not enough to sate his hunger. Luckily for him, he finds a hut in the distance, where a little frog lives. Hans tells the little animal he wants to find work, and the frog agrees to hire him, his only job is to carry the frog on a satin pillow, and he shall have drink and food. One day, the youth sighs that his brothers are probably returning home with gifts for their mother, and he has none to show them. The little frog tells Hans to sleep and, in the next morning, to knock three times on the stable door with a wand; he will find a beautiful horse he can ride home, and a little box. Hans goes back home with the horse and gives the little box to his mother; inside, a beautiful dress of gold and diamond buttons. Hans’s brothers question the legitimate origin of the dress. Some time later, the brothers go back to their masters and promise to return with their brides. Hans goes back to the little frog’s hut and mopes that his brother have bride to introduce to his family, while he has the frog. The frog tells him not to worry, and to knock on the stable again. Hans does that and a carriage appears with a princess inside, who is the frog herself. The princess asks Hans to take her to his parents, but not let her put anything on her mouth during dinner. Hans and the princess go to his parents’ house, and he fulfills the princess’s request, despite some grievaance from his parents and brothers. Finally, the princess turns back into a frog and tells Hans he has a last challenge before he redeems her: Hans will have to face three nights of temptations, dance, music and women in the first; counts and nobles who wish to crown him king in the second; and executioners who wish to kill him in the third. Hans endures and braves each night, awakening in the fourth day in a large castle. The princess, fully redeemed, tells him the castle is theirs, and she is his wife.[42]

In another Polish tale, collected by collector Antoni Józef Gliński [pl] and translated into English by translator Maude Ashurst Biggs as The Frog Princess, a king wishes to see his three sons married before they eventually ascend to the throne. So, the next day, the princes prepare to shoot three arrows at random, and to marry the girls that live wherever the arrows land. The first two find human wives, while the youngest’s arrow falls in the margins of the lake. A frog, sat on it, agrees to return the prince’s arrow, in exchange for becoming his wife. The prince questions the frog’s decision, but she advises him to tell his family he married an Eastern lady who must be only seen by her beloved. Eventually, the king asks his sons to bring him carpet woven by his daughters-in-law. The little frog summons «seven lovely maidens» to help her weave the carpet. Next, the king asks for a cake to be baked by his daughters-in-law, and the little frog bakes a delicious cake for the king. Surprised by the frog’s hidden talents, the prince asks her about them, and she reveals she is, in fact, a princess underneath the frog skin, a disguise created by her mother, the magical Queen of Light, to keep her safe from her enemies. The king then summons his sons and his daughters-in-law for a banquet at the palace. The little frog tells the prince to go first, and, when his father asks about her, it will begin to rain; when it lightens, he is to tell her she is adorning herself; and when it thunders, she is coming to the palace. It happens thus, and the prince introduces his bride to his father, and whispers in his ear about the frogskin. The king suggests his son burns the frogskin. The prince follows through with the suggestion and tells his bride about it. The princess cries bitter tears and, while he is asleep, turns into a duck and flies away. The prince wakes the next morning and begins a quest to find the kingdom of the Queen of Light. In his quest, he passes by the houses of three witches named Jandza, which spin on chicken legs. Each of the Jandzas tells him that the princess flies in their huts in duck form, and the prince must hide himself to get her back. He fails in the first two houses, due to her shapeshifting into other animals to escape, but gets her in the third. They reconcile and return to his father’s kingdom.[43]

Other regions[edit]

Researchers Nora Marks Dauenhauer and Richard L. Dauenhauer found a variant titled Yuwaan Gagéets, heard during Nora’s childhood from a Tlingit storyteller. They identified the tale as belonging to the tale type ATU 402 (and a second part as ATU 400, «The Quest for the Lost Wife») and noted its resemblance to the Russian story, trying to trace its appearance in the teller’s repertoire.[44]

Adaptations[edit]

- A literary treatment of the tale was published as The Wise Princess (A Russian Tale) in The Blue Rose Fairy Book (1911), by Maurice Baring.[45]

- A translation of the story by illustrator Katherine Pyle was published with the title The Frog Princess (A Russian Story).[46]

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1939 Soviet film directed by Aleksandr Rou, is based on this plot. It was the first large-budget feature in the Soviet Union to use fantasy elements, as opposed to the realistic style long favored politically.[47]

- In 1953 the director Mikhail Tsekhanovsky had the idea of animating this popular national fairy tale. Production took two years, and the premiere took place in December, 1954. At present the film is included in the gold classics of «Soyuzmultfilm».

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1977 Soviet animated film is also based on this fairy tale.

- In 1996, an animated Russian version based on an in-depth version of the tale in the film «Classic Fairy Tales From Around the World» on VHS. This version tells of how the beautiful Princess Vasilisa was kidnapped and cursed by the evil wizard Kashay to make her his bride and only the love of the handsome Prince Ivan can free her.

- Taking inspiration from the Russian story, Vasilisa appears to assist Hellboy against Koschei in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls.

- The Frog Princess was featured in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, where it was depicted in a country setting. The episode features the voice talents of Jasmine Guy as Frog Princess Lylah, Greg Kinnear as Prince Gavin, Wallace Langham as Prince Bobby, Mary Gross as Elise, and Beau Bridges as King Big Daddy.

- A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék («Hungarian Folk Tales») (hu), with the title Marci és az elátkozott királylány («Martin and the Cursed Princess»).

- «Wildwood Dancing,» a 2007 fantasy novel by Juliet Marillier, expands the princess and the frog theme.[48]

Culture[edit]

Music

The Divine Comedy’s 1997 single The Frog Princess is loosely based on the theme of the original Frog Princess story, interwoven with the narrator’s personal experiences.

See also[edit]

- The Frog Prince

- The Princess and the Frog

- Vasilisa (name)

- Puddocky

References[edit]

- ^ Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 224, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ D. L. Ashliman, «Animal Brides: folktales of Aarne–Thompson type 402 and related stories»

- ^

Works related to The Frog-Tzarevna at Wikisource

- ^ Out of the Everywhere: New Tales for Canada, Jan Andrews

- ^ Barag, Lev. «Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка». Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 128.

- ^ Barag, Lev. «Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка». Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 128.

- ^ Dobrovolskaya, Varvara. «PLOT No. 425A OF COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS (“CUPID AND PSYCHE”) IN RUSSIAN FOLK-TALE TRADITION». In: Traditional culture. 2017. Vol. 18. № 3 (67). p. 139.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA — Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- ^ Kobayashi, Fumihiko (2007). «The Forbidden Love in Nature. Analysis of the «Animal Wife» Folktale in Terms of Content Level, Structural Level, and Semantic Level». Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore. 36: 144–145. doi:10.7592/FEJF2007.36.kobayashi.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 548. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Silver, Carole G. «Animal Brides and Grooms: Marriage of Person to Animal Motif B600, and Animal Paramour, Motif B610». In: Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (eds.). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. A Handbook. Armonk / London: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. p. 94.

- ^ Angelopoulos, Anna. «La fille de Thalassa». In: ELO N. 11/12 (2005): 17 (footnote nr. 5), 29 (footnote nr. 47). http://hdl.handle.net/10400.1/1607

- ^ Angelopoulou, Anna; Broskou, Aigle. «ΕΠΕΞΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ ΠΑΡΑΜΥΘΙΑΚΩΝ ΤΥΠΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΡΑΛΛΑΓΩΝ AT 300-499». Tome B: AT 400-499. Athens, Greece: ΚΕΝΤΡΟ ΝΕΟΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ Ε.Ι.Ε. 1999. p. 540.

- ^ Pino Saavedra, Yolando. Folktales of Chile. [Chicago:] University of Chicago Press, 1967. p. 258.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, Criticism. Norton Critical Edition. Norton, 1999. p. 31. ISBN 9780393972771

- ^ Leavy, Barbara Fass. In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender. NYU Press, 1994. pp. 204, 207, 212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.9.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. «The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions». In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 259-268. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- ^ Hayrapetyan Tamar. «Combinaisons archétipales dans les epopees orales et les contes merveilleux armeniens». Traduction par Léon Ketcheyan. In: Revue des etudes Arméniennes tome 39 (2020). pp. 499-500 and footnote nr. 141.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. «The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions». In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 259 (footnote nr. 9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- ^ Propp, V. Theory and history of folklore. Theory and history of literature v. 5. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. p. 143. ISBN 0-8166-1180-7.

- ^ Coxwell, C. F. Siberian And Other Folk Tales. London: The C. W. Daniel Company, 1925. p. 252.

- ^ Гура, Александр Викторович. «Символика животных в славянской народной традиции» [Animal Symbolism in Slavic folk traditions]. М: Индрик, 1997. pp. 380-382. ISBN 5-85759-056-6.

- ^ Radenkovic, Ljubinko. «Митолошки елементи у словенским народним представама о жаби» [Mythological Elements in Slavic Notions of Frogs]. In: Заједничко у словенском фолклору: зборник радова [Common Elements in Slavic Folklore: Collected Papers, 2012]. Београд: Балканолошки институт САНУ, 2012. pp. 379-397. ISBN 978–86–7179-074–1 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: invalid character.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. «The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions». In: Studia Celto-Slavica 3 (2010): 260. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54586/HXAR3954.

- ^ Kovalchuk Lidia Petrovna (2015). «Comparative research of blends frog-woman and toad-woman in Russian and English folktales». In: Russian Linguistic Bulletin, (3 (3)), 14-15. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/comparative-research-of-blends-frog-woman-and-toad-woman-in-russian-and-english-folktales (дата обращения: 17.11.2021).

- ^ Megas, Geōrgios A. Folktales of Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970. p. 224.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Violet Fairy Book, «The Frog»

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 438 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 718 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 49, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ Ciubotaru, Silvia. «Elena Niculiţă-Voronca şi basmele fantastice» [Elena Niculiţă-Voronca and the Fantastic Fairy Tales]. In: Anuarul Muzeului Etnografic al Moldovei [The Yearly Review of the Ethnographic Museum of Moldavia] 18/2018. p. 158. ISSN 1583-6819.

- ^ Barag, Lev. «Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка». Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. pp. 46 (source), 128 (entry).

- ^ Русские сказки в ранних записях и публикациях». Л.: Наука, 1971. pp. 203-213.

- ^ Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1890. pp. 331–355.

- ^ Драгоманов, М (M. Dragomanov).»Малорусские народные предания и рассказы». 1876. pp. 313-317.

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 179-181. ISBN 9781576070635.

- ^ Salmelainen, Eero. Suomen kansan satuja ja tarinoita. II Osa. Helsingissä: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. 1871. pp. 118–127.

- ^ Beauvois, Eugéne. Contes populaires de la Norvège, de la Finlande & de la Bourgogne, etc. Paris: E. Dentu, Éditeur. 1862. pp. 180–193.

- ^ «Царевич и лягушка». Фольклор Азербайджана и прилегающих стран. Vol. 1. Баку: Изд-во АзГНИИ. Азербайджанский государственный научно-исследовательский ин-т, Отд-ние языка, литературы и искусства (под ред. А. В. Багрия). 1930. pp. 30–33.

- ^ Челеби Э. (1983). «Описание крепости Шеки/О жизни племени ит-тиль». Книга путешествия. (Извлечения из сочинения турецкого путешественника ХVII века). Вып. 3. Земли Закавказья и сопредельных областей Малой Азии и Ирана. Москва: Наука. p. 159.

- ^ Toeppen, Max. Aberglauben aus Masuren, mit einem Anhange, enthaltend: Masurische Sagen und Mährchen. Danzig: Th. Bertling, 1867. pp. 158-162.

- ^ Polish Fairy Tales. Translated from A. J. Glinski by Maude Ashurst Biggs. New York: John Lane Company. 1920. pp. 1-15.

- ^ Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Dauenhauer, Richard L. «Tracking “Yuwaan Gagéets”: A Russian Fairy Tale in Tlingit Oral Tradition». In: Oral Tradition, 13/1 (1998): 58-91.

- ^ Baring, Maurice. The Blue Rose Fairy Book. New York: Maude, Dodd and Company. 1911. pp. 247-260.

- ^ Pyle, Katherine. Tales of folk and fairies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1919. pp. 137-158.

- ^ James Graham, Baba Yaga in Film[Usurped!]

- ^ https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/13929.Wildwood_Dancing

External links[edit]

- The Frog Princess on YouTube

- The Wise Princess (The Blue Rose Fairy Book) from Project Gutenberg

- The Frog Princess (Ukrainian Folk Tale)

- The Frog Princess (Polish Folk Tale)

- The Frog Princess (Chinese Folk Tale)

Две с половиной тысячи лет назад записал Геродот удивительные истории о скифах. Одна из них напомнила нам сюжет русской сказки. Но, чтобы утвердиться в своей догадке, пришлось отыскать ее старинный вариант.

Итак, что записал Геродот? Богатырь (историк называет его Гераклом) попадает в далекую страну, которую позже назовут Скифией, и, утомленный, засыпает. А проснувшись, обнаруживает пропажу: нет его коней. Он отправляется на поиски и приходит к пещере, где живет полуженщина-полузмея. Образ фантастический, но Геродот опирается на представления реального народа – скифов. В древности часто отдавали предпочтение небесным девам, богиням, которые являлись людям и объединяли черты матерей-прародительниц.

Геракл приглянулся деве, она согласна вернуть коней при условии, что герой возьмет ее в жены. От этого брака рождается трое сыновей: Агафирс, Гелон и Скиф. Уходя на новые подвиги, Геракл наказывает удивительной женщине дать его пояс и лук всем сыновьям поочередно: тот, кто опояшется поясом и сумеет натянуть его лук, пусть правит страной. Это удалось сделать Скифу. По его имени и назвали страну Скифией.

О богине, обитающей в пещере, и о Геракле, помогающем ей победить гигантов, рассказывает и историк античности Страбон.

И вот еще одна версия — поразительная сказка «О лягушке и богатыре». Донесли ее до довольно поздних времен русские сказочники. Опубликована она впервые в XVIII веке в сборнике десяти русских сказок. В устном варианте, дошедшем до XVIII века, еще сохранились древние скифские мотивы, в ее героине еще узнается дева-сирена, женщина-полузмея. Понятно, что многие поколения безвестных рассказчиков изменили божественные образы и реалии скифской старины, упростили их, приземлили. Превратили женщину-сирену в царевну-лягушку. Однако самые большие искажения история претерпела именно в последние два столетия. Пересказы стерли следы древности, мифилогическое повествование превратилось в детскую сказочку, местами даже глуповатую, вряд ли кто теперь готов принимать ее всерьез. Даже название ее не сохранилось. До нас дошло просто «Царевна-лягушка». Но ведь это тавтология. Слово «лугаль» было известно еще почти пять тысяч лет назад шумерам, и означает оно буквально «царь». Его варианты – «регул», «лугаль» – прописаны на картах звездного неба со времен Шумера и Вавилона.

Три «любимицы» короля (царя), родившие ему трех сыновей, героев сказки, в поздних вариантах даже не упоминаются. А ведь само начало сказки в ее старинном виде переносит читателя в особый мир. В исторически обозримые времена не найти, как правило, царей без цариц, без законных наследников. Отклонения от этой нормы – редкое исключение. Зато мифы сообщают нам об этом далеко не в виде исключения.

Геракл считается сыном Зевса, главы Олимпа. Но у Зевса как раз и были многочисленные «любимицы» и потомки от них. Сказка пришла к нам из эпохи богов. Бог богов Зевс был неоднократно женат. Иногда говорят о восьми или девяти его женах. Намного больше было у него «любимиц». Геракл рожден от смертной женщины Алкмены. Ее родная бабка Даная тоже была возлюбленной Зевса. В сказке число «любимиц» сокращено до трех – быть может, из соображений нравственных.

В поздних пересказах действие начинается со странного события. Царь созывает сыновей, велит им взять луки и выпустить в чистом поле по стреле: куда стрела попадет, там и судьба, там живет его невеста. Вот такие простаки – царь с сыновьями. А речь-то идет о сыновьях от разных «любимиц» и о царе не столько земном, сколько небесном. И тут вполне уместно испытание с помощью лука. Древний миф предлагает для этого оружия самое почетное место: выходят братья вовсе не в чистое поле, а в заповедные луга. Это луга чудес, небесные луга, и нужно самому найти там свою судьбу, если ты рожден не законной царицей, а просто «любимицей».

В Геракле воплощены черты самого Зевса, и у него, согласно Геродоту, именно три сына, и, как в сказке, они должны пройти испытание с помощью лука. Братья старшие стреляют вправо и влево, а Иван-царевич пускает стрелу прямо, и попадает она в болото. А там шалаш из тростника. В шалаше лягушка.

«Лягушка, лягушка, отдай мою стрелу!» – просит Иван-царевич в сказке, известной нам с детства. В старинном же варианте Иван-богатырь, наоборот, от стрелы своей хочет отступиться. Там лягушка требует, чтобы герой взял стрелу: «Войди в мой шалаш и возьми свою стрелу! Ежели не взойдешь, то вечно из болота не выйдешь!»

Но шалаш мал, Ивану не войти в него. Тогда лягушка перекувырнулась – и шалаш превратился в роскошную беседку. Удивился Иван и вошел. А лягушка говорит: «Знаю, что ты три дня ничего не ел». И правда: три дня бродил Иван по горам и лесам, по болоту, пока искал свою стрелу. Снова лягушка перекувырнулась, и появился стол с кушаньями и напитками. Только когда Иван отобедал, лягушка заговорила о замужестве.

В подлинной русской сказке Иван-богатырь решает в уме сложную задачу: как отказать лягушке. Он только думает. Но по законам магии лягушка читает его мысли. Значит, магия – реальность, которая хорошо была известна нашим предкам, а мы лишь сравнительно недавно научились произносить вслух слово «телепатия». Иван хочет обмануть лягушку, и она, угадав это его желание, грозит, что он не найдет пути из болота домой. «Ничего не поделаешь, – думает Иван, – нужно брать ее в жены». И только он это подумал, сбросила лягушка кожу и превратилась в «великую красавицу»: «Вот, любезный Иван-богатырь, какова я есть». Обрадовался Иван и поклялся, что возьмет лягушку за себя.

А что в пересказе осталось? Не отдала лягушка Ивану стрелу, велела в жены себя брать: «Знать, судьба твоя такая». Закручинился Иван-царевич. Вот и все переживания. И далее. Удивительная вещь: в исконной сказке царь, расстроившись от всей этой истории со стрелой и болотом, которой он сам и был зачинщиком, уговаривает Ивана бросить лягушку! А Иван просит отца позволить ему жениться. Оно и понятно. Он же знает, какова она есть на самом деле. Это в пересказе – лягушка и лягушка. Там весь смысл перечеркнут. И за сим сразу читаем: царь сыграл три свадьбы. Будто ничего странного не произошло, будто в порядке вещей богатырям на лягушках жениться. А ведь цари к женитьбе сыновей своих относились достаточно серьезно.

Вот эпизод с рубашками, которые царь заказывает сшить женам сыновей. В пересказе, помните, лягушка спать Ивана уложила, сама прыгнула на крыльцо, кожу сбросила, обернулась Василисой Премудрой, в ладоши хлопнула: «Мамки, няньки, собирайтесь. Сшейте мне к утру такую рубашку, какую видела я у моего родного батюшки». Потом царь дары сыновей принимал. Рубашку старшего сына – в черной избе носить, среднего сына – только в баню ходить. А рубашку Ивана-царевича – в праздник надевать.

В истинной сказке мамок да нянек кличут старшие снохи. И пока те им кроят и шьют, их девка-чернавка пробирается в комнаты Ивана-богатыря, чтобы подсмотреть, что будет делать с царским полотном лягушка. А лягушка изрезала все полотно на мелкие кусочки, бросила на ветер и сказала: «Буйны ветры! Разнесите лоскуточки и сшейте свекру рубашку». Царь наутро принимал подарки. Посмотрел на рубашку, которую поднес больший брат, и сказал: «Эта сорочка сшита так, как обыкновенно шьют». И у другого сына рубашка была не лучше. Вот на лягушкину рубашку царь надивиться не мог: нельзя было найти на ней ни одного шва! А шитье без швов, насколько мне известно, привилегия представителей внеземных цивилизаций! Ветры буйные шили лягушке.

Затем следует история с ковроткачеством. Из золота, серебра и шелка мамки и няньки старших невесток соткали ковры. Но те годились лишь на то, чтобы во время дождя коней покрывать или в передней комнате под ноги приезжающим постилать. А для лягушки те же ветры буйные выткали ковер такой, «каким ее батюшка окошки закрывал». Царь, на ковер этот подивившись, велел постилать его на свой стол в самые торжественные дни.

Третьим испытанием для жен стал хлеб, который им надо было испечь.

«Испекись, хлеб, чист, и рыхл, и бел, как снег!» – произнесла лягушка, опрокинув квашню с тестом в холодную печь (магическое, между прочим, заклинание!). Так в сказке. Это в пересказе лягушка ломает печь и «прямо туда, в дыру, всю квашню и опрокинула». Но разломанная печь, несмотря ни на какие магические заклинания, вряд ли сможет печь хлеб. Законы магии достаточно строги, любая деталь имеет свое значение. И едва ли сыновья царя осмелились бы подать отцу хлеб, испеченный вот так: побросали тесто в печь и грязь эту вынули. В сказке все по-другому. Там их жены, убедившись, что хлеб по «рецепту» лягушки у них не получится, спешно разводят огонь в печи и пекут обычным способом. Но времени у них в обрез, и получается хлеб неважным. Все очень просто, как в жизни. Таковы законы подлинных сказок. С одной стороны – волшебство, с другой – сама жизнь, неприкрашенная. Трижды показали молодые жены свое искусство. И каждая могла бы хоть раз показать себя. Но верх взяла лягушка.

И вот подоспело время пира. Царь в благодарность за то, что невестки старались, приглашает их во дворец. (Заметим: в пересказе просто пир. В честь чего – неизвестно.) Лягушка едет на пир в карете парадной, которую принесли ей опять-таки ветры буйные от ее батюшки. Это в пересказе поднимает она шум да гром, а что сие означает, ведомо лишь пересказчикам. Описание пира совпадает, почти адекватно. А вот когда Иван сжигает кожу лягушачью, царевна ему и говорит: «Ну, Иван-богатырь, ищи меня теперь за тридевять земель, в тридесятом царстве, в Подсолнечном государстве. И знай, что зовут меня Василиса Премудрая». Только теперь узнает Иван настоящее имя своей жены. И искать ее он должен в Подсолнечном царстве, а не у Кащея Бессмертного. Не правда ли, есть разница?

В поисках жены приходит Иван к избушке Бабы Яги. И узнает, что прилетает Василиса к Яге каждый день для отдыха. А как ляжет она отдыхать, должен Иван поймать ее за голову, и «станет она оборачиваться лягушкой, жабой, змеей и прочими гадами и напоследок превратится в стрелу». Тогда должен Иван стрелу эту переломить о колено, и вечно будет Василиса Ивану принадлежать. Не сумел Иван-царевич удержать жену: как стала она змеей, испугался и отпустил. В ту же минуту Василиса пропала. Пришлось Ивану снова отправиться в путь, к другой Бабе Яге. Та же история. В третий раз отправился Иван, долго ли, коротко ли, близко ли, далеко ли – пришел наконец к избушке на курьих ножках. Встретила его еще одна Яга. Рассказал он ей, чего ищет. Дала ему Баба Яга наставления да предупредила, что если и теперь отпустит Иван жену, то уж никогда ее больше не получит. Выдержал Иван испытание, не струсил. Переломил стрелу надвое. И отдалась Василиса Премудрая в полную его волю. Подарила им Яга ковер-самолет, чтобы в три дня долетели они до своего государства.

Все в финале подлинной сказки говорит о близости ее к древнему мифу: лягушка обнаруживает свое родство с летающими богинями-змеями и сиренами. Пришелица из Подсолнечного царства, «мудрая змея-царевна» или «огненный разумный дракон», которые, согласно глухим, древнейшим сведениям оккультного характера, помогли людям приобщиться к науке и искусству, наделили их мудростью.

Много ли на свете сказок, герои которых были бы тысячелетия назад изваяны из камня или отчеканены из металла? И найдены были эти изображения археологами в наши дни. Ожил древний миф, рассказанный Геродотом. Ожила и русская сказка. И оказалось, что это не просто волшебная сказка, а след древней эпохи.

История персонажа

Много ли вы знаете сказок, сюжет которых был известен уже много сотен лет назад? Царевна-лягушка – персонаж, популярный среди народов Причерноморья и Приазовья. Археологи находят упоминания о ней на артефактах 5-3 в до н.э., добытых в скифских курганах. Сказочный персонаж, словно мифологический герой, воспевался древним населением и запечатлен мастерами той эпохи. Насколько реальна легенда о Царевне-лягушке, можно только догадываться. Вся правда о ней известна древним племенам, восхищавшимся фантастическим созданием.

История создания

Первая публикация легенды о сказочной героине датируется 18 веком. Сказание, передававшееся из уст в уста, называлось «Сказ о лягушке и богатыре». Авторство приписывают античному историку Геродоту. Скифские мифы, записанные им, изобиловали фантастическими сюжетами.

Повествование рассказывало о том, как разыскивавший пропавших коней богатырь попал в пещеру и столкнулся с невиданным существом. Полузмея-полуженщина обладала невиданной красотой. Девушка пообещала отдать лошадей, если герой возьмет ее в жены. В их союзе родились сыновья Скиф, Анафис и Гелон. Отец завещал им прохождение испытания. Юноши, опоясавшись его снаряжением и вооружившись луком, должны были выполнить задание. Призом был титул царя. Древние скифские мотивы, главенствующие в легенде, напрямую связаны с пониманием божественного мира древним населением.

За время пересказывания предания сюжет модифицировался. Божественные образы упростились. Существо с телом женщины и змеи превратилось в Царевну-лягушку. Она властвовала над стихиями, чем покорила Ивана-царевича, пришедшего за брошенной стрелой. Шалаш лягушки, куда был приглашен богатырь, мгновенно обратился изысканным шатром. Магический обряд дался Царевне-лягушке без труда, как и шитье бесшовной рубахи с помощью буйных ветров. Способности девушки сродни волшебству и возможностям космических пришельцев. Одежда без швов была «технологией», знакомой богам и представителям высшего разума. В этом символе есть детали оккультизма и намеки на власть над пространством.

Поразительная красота, которой обладал персонаж легенды, стала причиной зависти братьев царевича и послужила мотивацией для сожжения волшебной шкурки лягушки. Перед тем как исчезнуть, она назвала свое имя и пропала. Вопреки привычной трактовке, герою пришлось разыскивать суженую не в царстве Кощея Бессмертного, а в Подсолнечной стране. Древние люди именовали так Солнечную систему. Помощником Ивана стала Баба-Яга.