На чтение 9 мин Просмотров 1.6к. Опубликовано 27.06.2022

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ «Дюймовочка» за 1 минуту и подробно за 7 минут.

Очень краткий пересказ сказки «Дюймовочка»

Следуя совету волшебницы, одна бездетная, но очень желавшая детей, женщина посадила зернышко. Из него вырос цветок, внутри которого сидела крошечная прехорошенькая девочка. Так как малышка была всего дюйм (примерно 2,5 см) ростом, приемная мать назвала ее Дюймовочкой.

Крошке хорошо жилось у доброй женщины, пока ее не похитила старая противная жаба, пожелавшая отдать Дюймовочку замуж за своего сына.

С этих пор Дюймовочке приходилось несладко. Сначала она едва не стала женой глупого сына старухи жабы. Потом, когда пришла глубокая осень, дрожала от холода в поле, не имея дома. Затем девочка попала в норку ворчливой упрямой мыши.

И жилось бы ей у мыши неплохо, так как старушка полюбила девочку, однако только та надумала выдать Дюймовочку замуж за слепого толстого крота. Но ласточка, которой девочка спасла жизнь, унесла ее далеко, усадила на прекрасный белый цветок, и Дюймовочка вновь увидела бескрайнее голубое небо, согрелась и почувствовала себя счастливой.

В цветке жил маленький человечек с крыльями – король эльфов. Повелитель эльфийского народа влюбился в хорошенькую кроткую Дюймовочку, свадьбу весело отпраздновали, невесте подарили пару красивых крылышек. Теперь она тоже могла летать. Только звать ее с тех пор стали Майей. До сих пор она по-прежнему счастливо живет в волшебной стране эльфов.

Главный герой и его характеристика:

- Дюймовочка – очень маленькая, с дюйм ростом, прехорошенькая и добрая девочка. Готова была помогать всем, кто нуждался в заботе. Обладала прекрасным нежным голоском, чудесно пела песни. Девчушка была так мала, что скорлупа грецкого ореха служила ей кроваткой.

Второстепенные герои и их характеристика:

- Женщина – жительница селения или городка, страстно желавшая иметь ребенка, но волей судьбы женщина была бездетна. Готовая на все, женщина пошла к колдунье, от которой и получила настоящий подарок – крошечную Дюймовочку. Добрая, ласковая, приемная мать Дюймовочки делала все, чтобы малышке жилось хорошо.

- Колдунья – старая мудрая женщина, умевшая ворожить, знакомая с тайнами потустороннего мира, добрая, не отказывающая людям в помощи. За свои услуги берет совсем немного – 12 медяков (не серебро, не золото, а простые медные монеты).

- Старая жаба – противная, мокрая, большая обитательница болота. Захотела женить сына на Дюймовочке. Равнодушная и грубая, жаба попросту выкрала девочку, не спросив ее согласия.

- Сын жабы – глупый, мокрый и безобразный. Тупость этой амфибии доходила до полной неспособности произнести хоть какую-нибудь членораздельную фразу. Покорный сын своей матери.

- Крот – слепой и толстый житель подземелья. Был исключительно важным, не позволяющим себе проявлять эмоции господином (даже когда ему понравилось пение Дюймовочки, не проронил ни слова). Носил роскошную бархатную шубу. Ненавидел свет, солнце и птиц.

- Полевая мышь – старенькая мышка, не лишенная доброты и способности сочувствовать, но скучная и опасающаяся всего непривычного. Приютила, кормила и поила сироту Дюймовочку, а потом решила по-своему устроить ее судьбу, обеспечив солидным и богатым мужем-кротом.

- Майский жук – рогатое насекомое, заинтересовавшееся миленькой Дюймовочкой. Жук не думал о желаниях и чувствах самой девочки: просто взял ее и унес к своему семейству. А когда члены общества майских жуков раскритиковали Дюймовочку, поддался общему настроению и легко распрощался с крошкой.

- Ласточка – большая (по сравнению с Дюймовочкой) легкокрылая птичка. Умела мило щебетать, веселя Дюймовочку. Отблагодарила Дюймовочку за спасение жизни, забрав ее с собой в теплые края.

- Король эльфов – маленький светлый человечек, словно сделанный из утренней росы. Имел крылья и золотую корону. Правил крошечным народом эльфов. Полюбил Дюймовочку, которая так была на него похожа, рассмотрел ее красоту, позвал малышку замуж.

Краткое содержание сказки «Дюймовочка» подробно

Однажды бездетная женщина, но очень желавшая иметь ребенка, пришла к колдунье и пожаловалась на свою судьбу. Волшебница успокоила страдалицу: это дело легко поправить! Подав женщине ячменное зернышко, колдунья велела посадить и полить его. А затем ждать, что будет.

Женщина так и сделала. Зернышко тотчас проросло, вырос чудесный цветок. Не удержавшись, женщина поцеловала цветок, и он сразу раскрылся. В центре бутона сидела маленькая премиленькая девочка.

Назвав малышку Дюймовочкой, женщина стала за ней ухаживать. Сделала из скорлупы ореха колыбельку, в тарелку налила воды и устроила озеро, в котором плавала Дюймовочка.

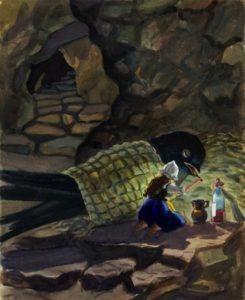

Девочка и ее приемная мать были счастливы, пока ночью в дом не пробралась огромная противная жаба. Увидев спящую в скорлупке Дюймовочку, жаба решила отдать ее в жены своему сыну, и украла малышку.

Дюймовочка проснулась и заплакала от страха: жаба поставила скорлупку на листок кувшинки, росшей на реке. Кругом вода! Что это, куда исчез родной дом?

Между тем жаба украшала свое жилище в болоте для будущих мужа и жены: своего сына и невесты. Сыночку Дюймовочка понравилась, только он даже сказать об этом не мог, так был глуп.

Посчитав, что все сделано, жаба вернулась за Дюймовочкой. Она решила сначала перенести скорлупку, а затем девочку. Но как только противная мамаша со своим глупым сыном скрылась, рыбки перегрызли стебель. Они пожалели Дюймовочку. Лист оторвался, девочка поплыла по течению реки.

Ее увидел майский жук. Девочка понравилась жуку, и он унес ее в своих лапках, чтобы показать семье и друзьям. Но те долго обсуждали Дюймовочку. Наконец решили, что она некрасива, и жук отнес девочку подальше и посадил на ромашку.

Погрустив, Дюймовочка принялась за дело: обустроила для себя жилище, навела уют, стала жить-поживать, питаясь медвяной росой. Но вот пришли холода, домик — цветок ее разрушился, есть стало нечего. Дюймовочка в поисках укрытия набрела на норку полевой мыши.

Мышь была старой и немножко ворчливой, но доброй. Она пожалела малышку и оставила ее у себя. Кормила приемную дочку, предоставила ей довольно уютное убежище от холода, а Дюймовочка в ответ прибирала дом мыши и рассказывала старушке сказки.

Как-то в гости к отшельницам явился толстый важный крот. Мышь решила, что для Дюймовочки будет большой удачей выйти замуж за такого холеного и богатого господина. А пока крот пригласил дам осмотреть свои владения.

По дороге к кроту троица наткнулась на мертвую птицу. То была ласточка, повредившая крыло и замерзшая на лету. Мышь и крот не любили птиц, а потому прошли мимо.

Ночью Дюймовочке не спалось. Она думала о ласточке, все лето забавлявшей ее веселыми песенками, а теперь лежащей в мрачном подземелье. Поднявшись с постели, Дюймовочка сплела ковер из сухих травинок, взяла теплого пуха и немного мха из кладовой и укутала ласточку. Прижавшись на минутку к птице, девочка вдруг услышала удары сердца: ласточка была жива! Она просто окоченела от холода, а сейчас начала согреваться.

Дюймовочка очень обрадовалась. Всю зиму она потихоньку подкармливала птицу, а весной открыла ей дыру в норе, через которую можно было улететь. На предложение ласточки лететь вместе Дюймовочка с грустью ответила отказом: ей было жаль покидать мышь, которая по-матерински привязалась к своей крохотной приемной дочке.

Все лето прожили девочка с мышью вдвоем. Старушка твердо решила, что Дюймовочку нужно выдать замуж за крота, и девочка готовила себе приданое.

Когда Дюймовочка вышла из норки в последний раз перед печальным замужеством взглянуть на солнце, она услышала пение ласточки. Это оказалась ее знакомая птичка. Ласточка улетала в теплые края и снова предложила Дюймовочке лететь вместе. На этот раз девочка охотно согласилась.

Пара путешественниц миновала замерзающие леса и луга и приземлилась возле залитого солнцем древнего беломраморного дворца. Одна из колонн дворца раскололась, около осколков росли большие красивые цветы. Там ласточка и оставила Дюймовочку, а сама полетела в свое гнездо, устроенное над одной из оставшихся целыми колонн.

Девочка увидела прозрачного маленького человечка, за спиной которого трепетали крылья. Оказалось, что это король эльфов. Дюймовочка и эльф понравились друг другу. Недолго думая, сыграли свадьбу. Дюймовочка стала носить имя Майя. Эльфы подарили ей крылышки, и она летала с ними вместе с цветка на цветок.

Вернувшись на лето на родину, ласточка рассказала эту историю одному сказочнику. А тот поведал ее всему миру.

Кратко об истории создания произведения

Когда именно Ганс Христиан Андерсен написал «Дюймовочку», сейчас установить трудно. В печать она попала в 1835 году в составе «Сборника сказок, рассказанных для детей». Вероятно, писателя вдохновляли истории об эльфах – крошечном летающем народце. Прототипом Дюймовочки считается дочь знакомого Андерсену переводчика Генриетта Вульф. Девушка была мала ростом и обладала кротким нравом. Прототип крота – некий реально существовавший учитель.

Российские дети познакомились с Дюймовочкой только в конце XIX века, причем сначала ее звали Лизок-с-вершок. Благозвучное имя Дюймовочка маленькая героиня получила позже.

Сказка учит маленьких читателей не пасовать перед трудностями, делать добрые дела и верить в удачу.

1

Андерсен. Дюймовочка, какой финал у сказки, чем всё закончилось?

1 ответ:

2

0

Финал сказки Андерсена «Дюймовочка» великолепный. Эта маленькая девочка, которая перенесла на своих хрупких плечиках все невзгоды, девочка, которую истязали, кому не лень, в конце концов стала счастливой, вышла замуж за принца-эльфа, и они вместе парили над цветами и вкушали все радости мира. Плохо лишь то, что мы уже никогда не узнаем, какие прекрасные дети родились от такой прекрасной любви, но об этом мы можем только предполагать.Редко, когда у Андерсена сказки имеют счастливый конец, но именно эта прекрасная сказка «Дюймовочка» как раз заканчивается тем, что девочка находит свою любовь, устраивает свою жизнь, и все рады этому…

Читайте также

Реальный один — Эльф, которому для того, чтобы заполучить Дюймовочку, даже пришлось прибегнуть к открытому шантажу.

Так что всего один. Ибо жук её нагло продинамил,

а крота

и жабу — сына, так она сама жёстко кинула через колено.

Дикие лебеди. Эта сказка очень нравится миллионам читателей и почитателей творчества великого датчанина, Ганса Христиана Андерсена.

Совершенно естественно предположить, что если данное произведение является сказкой, то и события описываются сказочные, то есть такие, которые никак и никогда не смогли бы произойти в реальной жизни.

Если кратко, то королевская дочь по имени Элиза, спасает своих братьев, которых злая мачеха превратила в белых лебедей.Девушка проходит через все испытания и невзгоды, рискует жизнью ради спасения своих близких людей.

Более подробно смотрите цитату в конце этого ответа.

В принципе, сказка о любви и о способности к самопожертвованию.

Только моё мнение.

Потому, что для жука было очень влиятельно общественное мнение. Когда жук привёл на танцплощадку Дюймовочку, не неё обратили внимание гусеницы, и высказали своё мнение «у неё не талии, и даже усиков». На что жук отреагировал, приняв к сведению эти слова, и сказал Дюймовочке «Вы кроме меня, никому не понравились, увы». Поэтому жук и бросил Дюймовочку,так как Дюймовочка была из другого «теста».

Ганс Христиан Андерсен хотел прославиться как драматург и романист и не воспринимал себя только как сказочника, очень злился, когда его называли автором сказок для детей, считая,что пишет и для взрослых, по этой причине потребовал, чтобы его памятник не окружали дети.

У Андерсена есть сказка про Исаака Ньютона, его сказку «Новое платье короля» включил в свою первую азбуку Лев Николаевич Толстой.

А у Константина Паустовского есть необыкновенно трепетный, пронзительный рассказ о датском сказочнике «Ночной дилижанс», а еще замечательные воспоминания о своем Андерсене, о его сказках, впервые открытых и прочитанных маленьким Паустовским, и о том впечатлении, которое осталось с ним на всю жизнь.

Я тоже недавно купила себе замечательный двухтомник сказок Андерсена, и нет времени лучше, чем время, проведенное за чтением этих книг.

думаю та, где всякие дюймовочки живут со всякими слепыми и богатыми кротами, та, где, чтобы найти любовь нужно побегать, и та, что нигде, никогда и ни у кого не бывает жизни без проблем и приключений, и чтобы жить спокойно нужно сначала «помучаться»

Краткое содержание «Дюймовочка»

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 462.

Обновлено 15 Сентября, 2022

О произведении

Сказка «Дюймовочка» Андерсена была опубликована впервые в 1835 году. Как большинство произведений писателя, сюжет сказки был плодом его воображения, а не заимствован из народного творчества. Это история о крошечной девочке, которой пришлось пережить немало испытаний, прежде чем она обрела счастье.

Для читательского дневника и подготовки к уроку литературы в 3 классе рекомендуем читать онлайн краткое содержание «Дюймовочки».

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 36 лет.

Место и время действия

События сказки происходят в волшебном мире: возле реки, в норе мыши, в стране эльфов.

Главные герои

- Дюймовочка – маленькая красивая девочка, очень добрая и смелая.

Другие персонажи

- Женщина – бездетная женщина, ставшая матерью Дюймовочке.

- Жаба – безобразное создание, похитившее беззащитную Дюймовочку.

- Майский жук – похититель Дюймовочки, быстро охладевший к ней.

- Полевая мышь – заботливая, расчетливая хозяйка.

- Крот – сосед полевой мыши; по ее мнению, богатый, знатный, завидный жених.

- Ласточка – раненая птица, которую выходила Дюймовочка.

- Король эльфов – повелитель эльфов в теплой стране, жених Дюймовочки.

Краткое содержание

Как-то раз женщина, у которой не было детей, отправилась к доброй колдунье за помощью. Получив от нее ячменное зерно, женщина посадила его в цветочный горшок и принялась ждать.

В скором времени из семечка вырос «большой чудесный цветок вроде тюльпана»

. Когда лепестки его раскрылись, внутри оказалась крошечная девочка, которую женщина назвала Дюймовочкой.

Однажды, когда Дюймовочка крепко спала, на окно взобралась «большущая жаба, мокрая, безобразная»

. Она схватила спящую девочку и поспешила на свое болото. Мерзкая жаба решила женить своего сынка на красавице Дюймовочке, а чтобы она не сбежала, посадила ее «посередине реки на широкий лист кувшинки»

.

Когда девочка поняла, какая страшная участь ее ожидает, она горько заплакала. Маленькие рыбки пожалели девочку и помогли ей сбежать. Они перегрызли стебель кувшинки, и «листок с девочкой поплыл по течению, дальше, дальше»

.

Мимо пролетал крупный майский жук. Увидев красивую девочку, он схватил ее и унес на дерево, где представил своим знакомым. Однако «жучки-барышни шевелили усиками и говорили»

, что Дюймовочка недостаточно хороша и не может находиться в их обществе. Майский жук тут же решил, «что она безобразна, и не захотел больше держать ее у себя»

. Он спустил девочку на землю и попрощался.

Все лето Дюймовочка жила «одна-одинешенька в лесу»

. Из травинок и листьев она сплела себе колыбельку. Питалась она цветочной пыльцой и росой, в ясную погоду грелась на солнышке, а от дождика скрывалась под большим листом лопуха.

Но вскоре на смену солнечному лету пришли холодные осенние дожди и ветра. Дюймовочку, которая страдала от голода и холода, приютила полевая мышь. Они славно зажили вместе: девочка помогала мыши по хозяйству, рассказывала ей сказки, а взамен получала теплый кров и пропитание.

У полевой мыши был сосед – богатый и ученый крот, который тем и занимался, что все время пересчитывал свое богатство. Он собирался жениться на Дюймовочке, как только та подготовит себе приданое. Но девочка была совсем не рада этому – «ей не нравился скучный крот»

.

Однажды, гуляя по подземным переходам, Дюймовочка увидела раненую ласточку, которая чуть не умерла от холода. Всю зиму она ухаживала за больной птичкой и к весне выходила ее.

Перед свадьбой Дюймовочка попросила мышь отпустить ее наверх полюбоваться напоследок солнышком. Когда она вылезла из мышиной норы, то увидела ласточку, которую вылечила. Дюймовочка пожаловалась птице, что ее заставляют выйти «замуж за противного крота и жить с ним глубоко под землей»

.

Ласточка предложила девочке улететь с ней в теплые края, и та согласилась. Оказавшись в чудесной стране, Дюймовочка увидела маленького человечка с прозрачными крылышками – это был король эльфов. Он сразу влюбился в Дюймовочку и предложил ей стать «его женой, королевой эльфов и царицей цветов»

.

И что в итоге?

Дюймовочка — улетает с Ласточкой в тёплые края, встречает там Короля эльфов и выходит за него замуж.

Заключение

Главная мысль книги – нужно стойко переносить все трудности и лишения, не унывать и не опускать руки, ведь в конце пути приходит заслуженное счастье.

После ознакомления с кратким пересказом сказки Андерсена «Дюймовочка» рекомендуем прочесть ее в полной версии.

Тест по сказке

Проверьте запоминание краткого содержания тестом:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Инна Васипова

10/10

-

Ирина Лесникова

9/10

-

Ирина Давыдова

8/10

-

Милана Блинова

8/10

-

Кирилл Бычков

10/10

-

Маша Максимова

10/10

-

Милана Калинина

9/10

-

Шварева Наталья

8/10

-

Наталья Сквознякова

10/10

-

Ольга Годер

8/10

Рейтинг пересказа

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 462.

А какую оценку поставите вы?

This article is about the 1835 literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. For other uses, see Thumbelina (disambiguation).

| «Thumbelina» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Hans Christian Andersen | ||

Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen, |

||

| Original title | Tommelise | |

| Translator | Mary Howitt | |

| Country | Denmark | |

| Language | Danish | |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale | |

| Published in | Fairy Tales Told for Children. First Collection. Second Booklet. 1835. (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. Andet Hefte. 1835.) | |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection | |

| Publisher | C. A. Reitzel | |

| Media type | ||

| Publication date | 16 December 1835 | |

| Published in English | 1846 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

||

| Full text | ||

Thumbelina (; Danish: Tommelise) is a literary novel bedtime story fairy tale written by the famous Danish author Hans Christian Andersen first published by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen, Denmark, with «The Naughty Boy» and «The Travelling Companion» in the second instalment of Fairy Tales Told for Children. Thumbelina is about a tiny girl and her adventures with marriage-minded toads, moles, and cockchafers. She successfully avoids their intentions before falling in love with a flower-fairy prince just her size.

Thumbelina is chiefly Andersen’s invention, though he did take inspiration from tales of miniature people such as «Tom Thumb». Thumbelina was published as one of a series of seven fairy tales in 1835 which were not well received by the Danish critics who disliked their informal style and their lack of morals. One critic, however, applauded Thumbelina.[1] The earliest English translation of Thumbelina is dated 1846. The tale has been adapted to various media including television drama and animated film.

Plot[edit]

A woman yearning for a child asks a witch for advice, and is presented with a barley which she is told to go home and plant (in the first English translation of 1847 by Mary Howitt, the tale opens with a beggar woman giving a peasant’s wife a barleycorn in exchange for food). After the barleycorn is planted and sprouts, a tiny girl named Thumbelina (Tommelise) emerges from its flower.

One night, Thumbelina, asleep in her walnut-shell cradle, is carried off by a toad who wants her as a bride for her son. With the help of friendly fish and a butterfly, Thumbelina escapes the toad and her son, and drifts on a lily pad until captured by a stag beetle who later discards her when his friends reject her company.

Thumbelina tries to protect herself from the elements. When winter comes, she is in desperate straits. She is finally given shelter by an old field mouse and tends her dwelling in gratitude. Thumbelina sees a swallow who is injured while visiting a mole, a neighbor of the field mouse. She meets the swallow one night and finds out what happened to him. She keeps on visiting the swallow during midnight without telling the field mouse and tries to help him gain strength and she frequently spends time with him singing songs and telling him stories and listening to his stories in the winter until spring arrives. The swallow, after becoming healthy, promises that he would come to that spot again and flies away saying goodbye to Thumbelina.

At the end of winter, the mouse suggests Thumbelina marry the mole, but Thumbelina finds the prospect of being married to such a creature repulsive because he spends all his days underground and never sees the sun or sky, even though he is impressive with his knowledge of ancient history and lots of other topics. The field mouse keeps pushing Thumbelina into the marriage, insisting the mole is a good match for her. Eventually Thumbelina sees little choice but to agree, but cannot bear the thought of the mole keeping her underground and never seeing the sun.

At the last minute, Thumbelina escapes the situation by fleeing to a far land with the swallow. In a sunny field of flowers, Thumbelina meets a tiny flower-fairy prince just her size and to her liking; they eventually wed. She receives a pair of wings to accompany her husband on his travels from flower to flower, and a new name, Maia. In the end, the swallow is heartbroken once Thumbelina marries the flower-fairy prince, and flies off eventually arriving at a small house. There, he tells Thumbelina’s story to a man who is implied to be Andersen himself, who chronicles the story in a book.[2]

Background[edit]

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805 to Hans Andersen, a shoemaker, and Anne Marie Andersdatter.[3] An only child, Andersen shared a love of literature with his father, who read him The Arabian Nights and the fables of Jean de la Fontaine. Together, they constructed panoramas, pop-up pictures and toy theatres, and took long jaunts into the countryside.[4]

Andersen’s father died in 1816,[5] and from then on, Andersen was left on his own. In order to escape his poor, illiterate mother, he promoted his artistic inclinations and courted the cultured middle class of Odense, singing and reciting in their drawing-rooms. On 4 September 1819, the fourteen-year-old Andersen left Odense for Copenhagen with the few savings he had acquired from his performances, a letter of reference to the ballerina Madame Schall, and youthful dreams and intentions of becoming a poet or an actor.[6]

After three years of rejections and disappointments, he finally found a patron in Jonas Collin, the director of the Royal Theatre, who, believing in the boy’s potential, secured funds from the king to send Andersen to a grammar school in Slagelse, a provincial town in west Zealand, with the expectation that the boy would continue his education at Copenhagen University at the appropriate time.

At Slagelse, Andersen fell under the tutelage of Simon Meisling, a short, stout, balding thirty-five-year-old classicist and translator of Virgil’s Aeneid. Andersen was not the quickest student in the class and was given generous doses of Meisling’s contempt.[7] «You’re a stupid boy who will never make it», Meisling told him.[8] Meisling is believed to be the model for the learned mole in «Thumbelina».[9]

Fairy tale and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie have proposed the tale as a «distant tribute» to Andersen’s confidante, Henriette Wulff, the small, frail, hunchbacked daughter of the Danish translator of Shakespeare who loved Andersen as Thumbelina loves the swallow;[10] however, no written evidence exists to support the theory.[9]

Sources and inspiration[edit]

«Thumbelina» is essentially Andersen’s invention but takes inspiration from the traditional tale of «Tom Thumb» (both tales begin with a childless woman consulting a supernatural being about acquiring a child). Other inspirations were the six-inch Lilliputians in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Voltaire’s short story «Micromégas» with its cast of huge and miniature peoples, and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s hallucinatory, erotic tale «Meister Floh», in which a tiny lady a span in height torments the hero. A tiny girl figures in Andersen’s prose fantasy «A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager» (1828),[9][11] and a literary image similar to Andersen’s tiny being inside a flower is found in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s «Princess Brambilla» (1821).[12]

Publication and critical reception[edit]

Andersen published two installments of his first collection of Fairy Tales Told for Children in 1835, the first in May and the second in December. «Thumbelina» was first published in the December installment by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen. «Thumbelina» was the first tale in the booklet which included two other tales: «The Naughty Boy» and «The Traveling Companion». The story was republished in collected editions of Andersen’s works in 1850 and 1862.[13]

The first reviews of the seven tales of 1835 did not appear until 1836 and the Danish critics were not enthusiastic. The informal, chatty style of the tales and their lack of morals were considered inappropriate in children’s literature. One critic however acknowledged «Thumbelina» to be «the most delightful fairy tale you could wish for».[14]

The critics offered Andersen no further encouragement. One literary journal never mentioned the tales at all while another advised Andersen not to waste his time writing fairy tales. One critic stated that Andersen «lacked the usual form of that kind of poetry […] and would not study models». Andersen felt he was working against their preconceived notions of what a fairy tale should be, and returned to novel-writing, believing it was his true calling.[15] The critical reaction to the 1835 tales was so harsh that he waited an entire year before publishing «The Little Mermaid» and «The Emperor’s New Clothes» in the third and final installment of Fairy Tales Told for Children.

English translations[edit]

In 1861, Alfred Wehnert translated the tale into English in Andersen’s Tales for Children under the title Little Thumb.[16] Mary Howitt published the story as «Tommelise» in Wonderful Stories for Children in 1846. However, she did not approve of the opening scene with the witch, and, instead, had the childless woman provide bread and milk to a hungry beggar woman who then rewarded her hostess with a barleycorn.[10] Charles Boner also translated the tale in 1846 as «Little Ellie» while Madame de Chatelain dubbed the child ‘Little Totty’ in her 1852 translation. The editor of The Child’s Own Book (1853) called the child throughout, ‘Little Maja’.

H. W. Dulcken was probably the translator responsible for the name, ‘Thumbelina’. His widely published volumes of Andersen’s tales appeared in 1864 and 1866.[10] Mrs. H.B. Paulli translated the name as ‘Little Tiny’ in the late-nineteenth century.[17]

In the twentieth century, Erik Christian Haugaard translated the name as ‘Inchelina’ in 1974,[18] and Jeffrey and Diane Crone Frank translated the name as ‘Thumbelisa’ in 2005. Modern English translations of «Thumbelina» are found in the six-volume complete edition of Andersen’s tales from the 1940s by Jean Hersholt, and Erik Christian Haugaard’s translation of the complete tales in 1974.[19]

[edit]

For fairy tale researchers and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, «Thumbelina» is an adventure story from the feminine point of view with its moral being people are happiest with their own kind. They point out that Thumbelina is a passive character, the victim of circumstances; whereas her male counterpart Tom Thumb (one of the tale’s inspirations) is an active character, makes himself felt, and exerts himself.[10]

Folklorist Maria Tatar sees «Thumbelina» as a runaway bride story and notes that it has been viewed as an allegory about arranged marriages, and a fable about being true to one’s heart that upholds the traditional notion that the love of a prince is to be valued above all else. She points out that in Hindu belief, a thumb-sized being known as the innermost self or soul dwells in the heart of all beings, human or animal, and that the concept may have migrated to European folklore and taken form as Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, both of whom seek transfiguration and redemption. She detects parallels between Andersen’s tale and the Greek myth of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone, and, notwithstanding the pagan associations and allusions in the tale, notes that «Thumbelina» repeatedly refers to Christ’s suffering and resurrection, and the Christian concept of salvation.[20]

Andersen biographer Jackie Wullschlager indicates that «Thumbelina» was the first of Andersen’s tales to dramatize the sufferings of one who is different, and, as a result of being different, becomes the object of mockery. It was also the first of Andersen’s tales to incorporate the swallow as the symbol of the poetic soul and Andersen’s identification with the swallow as a migratory bird whose pattern of life his own traveling days were beginning to resemble.[21]

Roger Sale believes Andersen expressed his feelings of social and sexual inferiority by creating characters that are inferior to their beloveds. The Little Mermaid, for example, has no soul while her human beloved has a soul as his birthright. In «Thumbelina», Andersen suggests the toad, the beetle, and the mole are Thumbelina’s inferiors and should remain in their places rather than wanting their superior. Sale indicates they are not inferior to Thumbelina but simply different. He suggests that Andersen may have done some damage to the animal world when he colored his animal characters with his own feelings of inferiority.[22]

Jacqueline Banerjee views the tale as a success story. «Not surprisingly,» she writes, «”Thumbelina» is now often read as a story of specifically female empowerment.»[23] Susie Stephens believes Thumbelina herself is a grotesque, and observes that «the grotesque in children’s literature is […] a necessary and beneficial component that enhances the psychological welfare of the young reader». Children are attracted to the cathartic qualities of the grotesque, she suggests.[24] Sidney Rosenblatt in his essay «Thumbelina and the Development of Female Sexuality» believes the tale may be analyzed, from the perspective of Freudian psychoanalysis, as the story of female masturbation. Thumbelina herself, he posits, could symbolize the clitoris, her rose petal coverlet the labia, the white butterfly «the budding genitals», and the mole and the prince the anal and vaginal openings respectively.[25]

Adaptations[edit]

Animation[edit]

The earliest animated version of the tale is a silent black-and-white release by director Herbert M. Dawley in 1924.[citation needed] Lotte Reiniger released a 10-minute cinematic adaptation in 1954 featuring her «silhouette» puppets.[26]

In 1964 Soyuzmultfilm released Dyuymovochka, a half-hour Russian adaptation of the fairy tale directed by Leonid Amalrik.[citation needed] Although the screenplay by Nikolai Erdman stayed faithful to the story, it was noted for satirical characters and dialogues (many of them turned into catchphrases).[27]

In 1992, Golden Films released Thumbelina (1992),[citation needed] and Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina afterwards. A Japanese animated series adapted the plot and made it into a movie, Thumbelina: A Magical Story (1992), released in 1993.[28]

On March 30, 1994, Warner Brothers released the animated film Thumbelina (1994),[29] directed by Don Bluth and Gary Goldman, with Jodi Benson as the voice of Thumbelina.

Live action[edit]

On June 11, 1985, a television dramatization of the tale was broadcast as the 12th episode of the anthology series Faerie Tale Theatre. The production starred Carrie Fisher.[30]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 221–9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 13

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 25–26

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 60–61

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, p. 77

- ^ a b c Frank & Frank 2005, p. 76

- ^ a b c d Opie & Opie 1974, p. 219

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, pp. 75–76

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen: Thumbelina». Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165

- ^ Andersen 2000, p. 335

- ^ Andersen, Hans Christian (1861). Andersen’s Tales for Children. Bell and Daldy.

- ^ Eastman, p. 258

- ^ Andersen 1983, p. 29

- ^ Classe 2000, p. 42

- ^ Andersen 2008, pp. 193–194, 205

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 163

- ^ Sale 1978, pp. 65–68

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline (2008). «The Power of «Faerie»: Hans Christian Andersen as a Children’s Writer». The Victorian Web: Literature, History, & Culture in the Age of Victoria. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Stephens, Susie. «The Grotesque in Children’s Literature». Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Siegel 1992, pp. 123, 126

- ^ «Däumlienchen». IMDb.

- ^ Petr Bagrov. Swine-herd and Stableman. From Hans Christian to Christian Hans article from Seance № 25/26, 2005 ISSN 0136-0108 (in Russian)

- ^ Clements, Jonathan; Helen McCarthy (2001-09-01). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 399. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

- ^ «Thumbelina — Character Designs, Cornelius, Thumbelina, and Bumble Bee». SCAD Libraries. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ «DVD Verdict Review — Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre: The Complete Collection». dvdverdict.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17.

References[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (1983) [1974]. The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories. Translated by Haugaard, Erik Christian. New York, NY: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-18951-6.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2000) [1871]. The Fairy Tale of My Life. New York, NY: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1105-7.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2008). Tatar, Maria (ed.). The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393060812.

- Classe, O., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English; v.2. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-36-2.

- Eastman, Mary Huse (ed.). Index to Fairy Tales, Myths and Legends. BiblioLife, LLC.

- Frank, Diane Crone; Frank, Jeffrey (2005). The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen. Durham, NC and London, UK: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3693-6.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211559-6.

- Sale, Roger (1978). Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E.B. White. New Haven, CT: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-29157-3.

- Siegel, Elaine V., ed. (1992). Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Women. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel, Inc. ISBN 0-87630-655-5.

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2002). Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91747-9.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thumbelina.

- Thumbelina English translation by Jean Hersholt

- Thumbelina: The Musical Musical of Thumbelina by Chris Seed and Maxine Gallagher

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

This article is about the 1835 literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. For other uses, see Thumbelina (disambiguation).

| «Thumbelina» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Hans Christian Andersen | ||

Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen, |

||

| Original title | Tommelise | |

| Translator | Mary Howitt | |

| Country | Denmark | |

| Language | Danish | |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale | |

| Published in | Fairy Tales Told for Children. First Collection. Second Booklet. 1835. (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. Andet Hefte. 1835.) | |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection | |

| Publisher | C. A. Reitzel | |

| Media type | ||

| Publication date | 16 December 1835 | |

| Published in English | 1846 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

||

| Full text | ||

Thumbelina (; Danish: Tommelise) is a literary novel bedtime story fairy tale written by the famous Danish author Hans Christian Andersen first published by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen, Denmark, with «The Naughty Boy» and «The Travelling Companion» in the second instalment of Fairy Tales Told for Children. Thumbelina is about a tiny girl and her adventures with marriage-minded toads, moles, and cockchafers. She successfully avoids their intentions before falling in love with a flower-fairy prince just her size.

Thumbelina is chiefly Andersen’s invention, though he did take inspiration from tales of miniature people such as «Tom Thumb». Thumbelina was published as one of a series of seven fairy tales in 1835 which were not well received by the Danish critics who disliked their informal style and their lack of morals. One critic, however, applauded Thumbelina.[1] The earliest English translation of Thumbelina is dated 1846. The tale has been adapted to various media including television drama and animated film.

Plot[edit]

A woman yearning for a child asks a witch for advice, and is presented with a barley which she is told to go home and plant (in the first English translation of 1847 by Mary Howitt, the tale opens with a beggar woman giving a peasant’s wife a barleycorn in exchange for food). After the barleycorn is planted and sprouts, a tiny girl named Thumbelina (Tommelise) emerges from its flower.

One night, Thumbelina, asleep in her walnut-shell cradle, is carried off by a toad who wants her as a bride for her son. With the help of friendly fish and a butterfly, Thumbelina escapes the toad and her son, and drifts on a lily pad until captured by a stag beetle who later discards her when his friends reject her company.

Thumbelina tries to protect herself from the elements. When winter comes, she is in desperate straits. She is finally given shelter by an old field mouse and tends her dwelling in gratitude. Thumbelina sees a swallow who is injured while visiting a mole, a neighbor of the field mouse. She meets the swallow one night and finds out what happened to him. She keeps on visiting the swallow during midnight without telling the field mouse and tries to help him gain strength and she frequently spends time with him singing songs and telling him stories and listening to his stories in the winter until spring arrives. The swallow, after becoming healthy, promises that he would come to that spot again and flies away saying goodbye to Thumbelina.

At the end of winter, the mouse suggests Thumbelina marry the mole, but Thumbelina finds the prospect of being married to such a creature repulsive because he spends all his days underground and never sees the sun or sky, even though he is impressive with his knowledge of ancient history and lots of other topics. The field mouse keeps pushing Thumbelina into the marriage, insisting the mole is a good match for her. Eventually Thumbelina sees little choice but to agree, but cannot bear the thought of the mole keeping her underground and never seeing the sun.

At the last minute, Thumbelina escapes the situation by fleeing to a far land with the swallow. In a sunny field of flowers, Thumbelina meets a tiny flower-fairy prince just her size and to her liking; they eventually wed. She receives a pair of wings to accompany her husband on his travels from flower to flower, and a new name, Maia. In the end, the swallow is heartbroken once Thumbelina marries the flower-fairy prince, and flies off eventually arriving at a small house. There, he tells Thumbelina’s story to a man who is implied to be Andersen himself, who chronicles the story in a book.[2]

Background[edit]

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805 to Hans Andersen, a shoemaker, and Anne Marie Andersdatter.[3] An only child, Andersen shared a love of literature with his father, who read him The Arabian Nights and the fables of Jean de la Fontaine. Together, they constructed panoramas, pop-up pictures and toy theatres, and took long jaunts into the countryside.[4]

Andersen’s father died in 1816,[5] and from then on, Andersen was left on his own. In order to escape his poor, illiterate mother, he promoted his artistic inclinations and courted the cultured middle class of Odense, singing and reciting in their drawing-rooms. On 4 September 1819, the fourteen-year-old Andersen left Odense for Copenhagen with the few savings he had acquired from his performances, a letter of reference to the ballerina Madame Schall, and youthful dreams and intentions of becoming a poet or an actor.[6]

After three years of rejections and disappointments, he finally found a patron in Jonas Collin, the director of the Royal Theatre, who, believing in the boy’s potential, secured funds from the king to send Andersen to a grammar school in Slagelse, a provincial town in west Zealand, with the expectation that the boy would continue his education at Copenhagen University at the appropriate time.

At Slagelse, Andersen fell under the tutelage of Simon Meisling, a short, stout, balding thirty-five-year-old classicist and translator of Virgil’s Aeneid. Andersen was not the quickest student in the class and was given generous doses of Meisling’s contempt.[7] «You’re a stupid boy who will never make it», Meisling told him.[8] Meisling is believed to be the model for the learned mole in «Thumbelina».[9]

Fairy tale and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie have proposed the tale as a «distant tribute» to Andersen’s confidante, Henriette Wulff, the small, frail, hunchbacked daughter of the Danish translator of Shakespeare who loved Andersen as Thumbelina loves the swallow;[10] however, no written evidence exists to support the theory.[9]

Sources and inspiration[edit]

«Thumbelina» is essentially Andersen’s invention but takes inspiration from the traditional tale of «Tom Thumb» (both tales begin with a childless woman consulting a supernatural being about acquiring a child). Other inspirations were the six-inch Lilliputians in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Voltaire’s short story «Micromégas» with its cast of huge and miniature peoples, and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s hallucinatory, erotic tale «Meister Floh», in which a tiny lady a span in height torments the hero. A tiny girl figures in Andersen’s prose fantasy «A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager» (1828),[9][11] and a literary image similar to Andersen’s tiny being inside a flower is found in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s «Princess Brambilla» (1821).[12]

Publication and critical reception[edit]

Andersen published two installments of his first collection of Fairy Tales Told for Children in 1835, the first in May and the second in December. «Thumbelina» was first published in the December installment by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen. «Thumbelina» was the first tale in the booklet which included two other tales: «The Naughty Boy» and «The Traveling Companion». The story was republished in collected editions of Andersen’s works in 1850 and 1862.[13]

The first reviews of the seven tales of 1835 did not appear until 1836 and the Danish critics were not enthusiastic. The informal, chatty style of the tales and their lack of morals were considered inappropriate in children’s literature. One critic however acknowledged «Thumbelina» to be «the most delightful fairy tale you could wish for».[14]

The critics offered Andersen no further encouragement. One literary journal never mentioned the tales at all while another advised Andersen not to waste his time writing fairy tales. One critic stated that Andersen «lacked the usual form of that kind of poetry […] and would not study models». Andersen felt he was working against their preconceived notions of what a fairy tale should be, and returned to novel-writing, believing it was his true calling.[15] The critical reaction to the 1835 tales was so harsh that he waited an entire year before publishing «The Little Mermaid» and «The Emperor’s New Clothes» in the third and final installment of Fairy Tales Told for Children.

English translations[edit]

In 1861, Alfred Wehnert translated the tale into English in Andersen’s Tales for Children under the title Little Thumb.[16] Mary Howitt published the story as «Tommelise» in Wonderful Stories for Children in 1846. However, she did not approve of the opening scene with the witch, and, instead, had the childless woman provide bread and milk to a hungry beggar woman who then rewarded her hostess with a barleycorn.[10] Charles Boner also translated the tale in 1846 as «Little Ellie» while Madame de Chatelain dubbed the child ‘Little Totty’ in her 1852 translation. The editor of The Child’s Own Book (1853) called the child throughout, ‘Little Maja’.

H. W. Dulcken was probably the translator responsible for the name, ‘Thumbelina’. His widely published volumes of Andersen’s tales appeared in 1864 and 1866.[10] Mrs. H.B. Paulli translated the name as ‘Little Tiny’ in the late-nineteenth century.[17]

In the twentieth century, Erik Christian Haugaard translated the name as ‘Inchelina’ in 1974,[18] and Jeffrey and Diane Crone Frank translated the name as ‘Thumbelisa’ in 2005. Modern English translations of «Thumbelina» are found in the six-volume complete edition of Andersen’s tales from the 1940s by Jean Hersholt, and Erik Christian Haugaard’s translation of the complete tales in 1974.[19]

[edit]

For fairy tale researchers and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, «Thumbelina» is an adventure story from the feminine point of view with its moral being people are happiest with their own kind. They point out that Thumbelina is a passive character, the victim of circumstances; whereas her male counterpart Tom Thumb (one of the tale’s inspirations) is an active character, makes himself felt, and exerts himself.[10]

Folklorist Maria Tatar sees «Thumbelina» as a runaway bride story and notes that it has been viewed as an allegory about arranged marriages, and a fable about being true to one’s heart that upholds the traditional notion that the love of a prince is to be valued above all else. She points out that in Hindu belief, a thumb-sized being known as the innermost self or soul dwells in the heart of all beings, human or animal, and that the concept may have migrated to European folklore and taken form as Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, both of whom seek transfiguration and redemption. She detects parallels between Andersen’s tale and the Greek myth of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone, and, notwithstanding the pagan associations and allusions in the tale, notes that «Thumbelina» repeatedly refers to Christ’s suffering and resurrection, and the Christian concept of salvation.[20]

Andersen biographer Jackie Wullschlager indicates that «Thumbelina» was the first of Andersen’s tales to dramatize the sufferings of one who is different, and, as a result of being different, becomes the object of mockery. It was also the first of Andersen’s tales to incorporate the swallow as the symbol of the poetic soul and Andersen’s identification with the swallow as a migratory bird whose pattern of life his own traveling days were beginning to resemble.[21]

Roger Sale believes Andersen expressed his feelings of social and sexual inferiority by creating characters that are inferior to their beloveds. The Little Mermaid, for example, has no soul while her human beloved has a soul as his birthright. In «Thumbelina», Andersen suggests the toad, the beetle, and the mole are Thumbelina’s inferiors and should remain in their places rather than wanting their superior. Sale indicates they are not inferior to Thumbelina but simply different. He suggests that Andersen may have done some damage to the animal world when he colored his animal characters with his own feelings of inferiority.[22]

Jacqueline Banerjee views the tale as a success story. «Not surprisingly,» she writes, «”Thumbelina» is now often read as a story of specifically female empowerment.»[23] Susie Stephens believes Thumbelina herself is a grotesque, and observes that «the grotesque in children’s literature is […] a necessary and beneficial component that enhances the psychological welfare of the young reader». Children are attracted to the cathartic qualities of the grotesque, she suggests.[24] Sidney Rosenblatt in his essay «Thumbelina and the Development of Female Sexuality» believes the tale may be analyzed, from the perspective of Freudian psychoanalysis, as the story of female masturbation. Thumbelina herself, he posits, could symbolize the clitoris, her rose petal coverlet the labia, the white butterfly «the budding genitals», and the mole and the prince the anal and vaginal openings respectively.[25]

Adaptations[edit]

Animation[edit]

The earliest animated version of the tale is a silent black-and-white release by director Herbert M. Dawley in 1924.[citation needed] Lotte Reiniger released a 10-minute cinematic adaptation in 1954 featuring her «silhouette» puppets.[26]

In 1964 Soyuzmultfilm released Dyuymovochka, a half-hour Russian adaptation of the fairy tale directed by Leonid Amalrik.[citation needed] Although the screenplay by Nikolai Erdman stayed faithful to the story, it was noted for satirical characters and dialogues (many of them turned into catchphrases).[27]

In 1992, Golden Films released Thumbelina (1992),[citation needed] and Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina afterwards. A Japanese animated series adapted the plot and made it into a movie, Thumbelina: A Magical Story (1992), released in 1993.[28]

On March 30, 1994, Warner Brothers released the animated film Thumbelina (1994),[29] directed by Don Bluth and Gary Goldman, with Jodi Benson as the voice of Thumbelina.

Live action[edit]

On June 11, 1985, a television dramatization of the tale was broadcast as the 12th episode of the anthology series Faerie Tale Theatre. The production starred Carrie Fisher.[30]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 221–9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 13

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 25–26

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 60–61

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, p. 77

- ^ a b c Frank & Frank 2005, p. 76

- ^ a b c d Opie & Opie 1974, p. 219

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, pp. 75–76

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen: Thumbelina». Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165

- ^ Andersen 2000, p. 335

- ^ Andersen, Hans Christian (1861). Andersen’s Tales for Children. Bell and Daldy.

- ^ Eastman, p. 258

- ^ Andersen 1983, p. 29

- ^ Classe 2000, p. 42

- ^ Andersen 2008, pp. 193–194, 205

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 163

- ^ Sale 1978, pp. 65–68

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline (2008). «The Power of «Faerie»: Hans Christian Andersen as a Children’s Writer». The Victorian Web: Literature, History, & Culture in the Age of Victoria. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Stephens, Susie. «The Grotesque in Children’s Literature». Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Siegel 1992, pp. 123, 126

- ^ «Däumlienchen». IMDb.

- ^ Petr Bagrov. Swine-herd and Stableman. From Hans Christian to Christian Hans article from Seance № 25/26, 2005 ISSN 0136-0108 (in Russian)

- ^ Clements, Jonathan; Helen McCarthy (2001-09-01). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 399. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

- ^ «Thumbelina — Character Designs, Cornelius, Thumbelina, and Bumble Bee». SCAD Libraries. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ «DVD Verdict Review — Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre: The Complete Collection». dvdverdict.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17.

References[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (1983) [1974]. The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories. Translated by Haugaard, Erik Christian. New York, NY: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-18951-6.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2000) [1871]. The Fairy Tale of My Life. New York, NY: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1105-7.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2008). Tatar, Maria (ed.). The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393060812.

- Classe, O., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English; v.2. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-36-2.

- Eastman, Mary Huse (ed.). Index to Fairy Tales, Myths and Legends. BiblioLife, LLC.

- Frank, Diane Crone; Frank, Jeffrey (2005). The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen. Durham, NC and London, UK: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3693-6.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211559-6.

- Sale, Roger (1978). Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E.B. White. New Haven, CT: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-29157-3.

- Siegel, Elaine V., ed. (1992). Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Women. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel, Inc. ISBN 0-87630-655-5.

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2002). Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91747-9.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thumbelina.

- Thumbelina English translation by Jean Hersholt

- Thumbelina: The Musical Musical of Thumbelina by Chris Seed and Maxine Gallagher

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Бездетная женщина просит колдунью исправить ее горе — у нее не было детей. Волшебница дает ей ячменное зернышко и рассказывает, как с ним поступить, чтобы исполнить желание женщины.

Женщина поступает, как ей велела колдунья и выращивает чудесный цветок. Когда его бутон раскрывается, она видит крохотную девочку. Она была настолько маленькой, что ей дали имя Дюймовочка.

Женщина недолго радуется своему счастью. Вскоре ее дочку похищает жаба. Она мечтает женить сына и считает, что Дюймовочка будет ему отличной парой.

О замыслах жабы узнают маленькие рыбки. Они пожалели девочку и перегрызли стебель кувшинки, где держали Дюймовочку жаба с сыном. Лист кувшинки быстро плыл по течению, и жабы уже не смогли бы догнать девочку. Уплыть еще дальше Дюймовочке помог мотылек, которого она обвязала своим пояском.

С листа кувшинки девочку уносит майский жук. Он кормит ее цветочным соком и говорит, что она прекрасна. Вскоре к жуку и Дюймовочке приходят другие жучки в гости. Они твердят, как девочка некрасива. Майский жук разочаровался в девочке. Он уносит ее на цветочную поляну.

Лето прожила Дюймовочка в лесу. Она сплела себе колыбель, питалась нектаром и пила росу.

Поздней осенью девочка постучалась в жилище полевой мыши и попросила ячменного зернышка. Полевая мышь впустила Дюймовочку к себе, предложила жить у нее и помогать ей в хозяйстве и рассказывать сказки.

Однажды к мыши в гости пришел крот. Он был богат, учен и слеп. Полевая мышь посоветовала девочке обойтись с ним ласково. Дюймовочка рассказала кроту несколько сказок и спела две песни. Ее голос так понравился кроту, что он сразу влюбился в девочку.

Крот предложил соседкам гулять по его новой галерее. Он предупредил, что там лежит мертвая птица. Все вместе они отправились на нее взглянуть. Пока мышь и крот отошли в сторону, Дюймовочка не сдерживает жалости и целует птичку.

Ночью девочка отправляется к птице. Она укутывает ласточку в ковер и закутывает ее в пух. Она прикладывается к груди птички, чтобы проститься с нею. Тут Дюймовочка слышит стук сердца ласточки.

На другой день девочка снова идет к ласточке. Она видит, что птица пришла в себя. Ласточка обещает скоро улететь. Дюймовочка просит ее остаться, потому что на улице холодно.

Ласточка рассказывает Дюймовочке, как поранила крыло о терновый куст. За зиму девочка с ласточкой стали друзьями.

Весной птица вылетает на улицу. Она зовет с собой Дюймовочку. Но девочка отказывается, чтобы не огорчать мышь.

Вскоре девочка начинает готовить приданое. За нее посватался сосед. Она до самой осени не выходит из дому. Она лишь утром и вечером стоит на пороге и изредка видит сквозь колосья солнце и небо.

Когда крот приходит за девочкой, она входит в последний раз посмотреть на солнце. К ней прилетает ласточка. Она говорит, что улетает в теплые страны и зовет Дюймовочку с собой.

Вместе они улетают. Ласточка показывает подруге свой дом и предлагает ей выбрать для себя цветок. Там Дюймовочка сможет жить.

Цветок, который выбрала девочка, оказался занятым. Там сидел крошечный человечек. Это был король эльфов. Дюймовочка любуется им. Король поражается красоте гостьи. Он предлагает Дюймовочке стать его женой.

Девочка соглашается. На свадьбе Дюймовочке дарят крылышки. Король эльфов дает своей королеве новое имя — Майя.

Когда ласточка прилетает снова в Данию, она селится за окном мастера рассказывать сказки. От нее он узнает историю Дюймовочки, а уже он знакомит с ней других людей.