Unless otherwise specified, Chinese in this article is written in simplified/traditional/pinyin order. If the simplified and traditional characters are the same, they are written only once.

| Chinese | |

|---|---|

| 汉语/漢語, Hànyǔ or 中文, Zhōngwén | |

Hànyǔ written in traditional (top) and simplified characters (middle); Zhōngwén (bottom) |

|

| Native to | Sinophone world |

|

Native speakers |

1.35 billion (2022) |

|

Language family |

Sino-Tibetan

|

|

Early forms |

Old Chinese

|

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

Chinese characters (Traditional/Simplified) Transcriptions: |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

Mandarin:

Cantonese:[a]

|

| Regulated by | Ministry of Education (in the reserved name of «National Commission on Language and Script Work [zh]«) (Mainland China) National Languages Committee (Taiwan) Civil Service Bureau (Hong Kong) Education and Youth Affairs Bureau (Macau) Chinese Language Standardisation Council (Malaysia) Promote Mandarin Council (Singapore) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | zh |

| ISO 639-2 | chi (B) zho (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | zho – inclusive codeIndividual codes: cdo – Min Dongcjy – Jinyucmn – Mandarincpx – Pu-Xian Minczh – Huizhouczo – Central Mingan – Ganhak – Hakkahsn – Xiangmnp – Min Beinan – Min Nanwuu – Wuyue – Yuecsp – Southern Pinghuacnp – Northern Pinghuaoch – Old Chineseltc – Late Middle Chineselzh – Classical Chinese |

| Glottolog | sini1245 |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA |

Map of the Chinese-speaking world. Regions with a native Chinese-speaking majority. Regions where Chinese is not native but an official or educational language. Regions with significant Chinese-speaking minorities. |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

| Han language (general or spoken) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 汉语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han people/dynasty’s language | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese text (especially written) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 中文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Chinese («middle/central») text (or writing) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Han text (especially written and when distinguished from other languages of China) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han text (or writing) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chinese[c] (中文; Zhōngwén,[d] especially when referring to written Chinese) is a group of languages spoken natively by the ethnic Han Chinese majority and many minority ethnic groups in Greater China. About 1.3 billion people (or approximately 16% of the world’s population) speak a variety of Chinese as their first language.[1]

Chinese languages form the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages family. The spoken varieties of Chinese are usually considered by native speakers to be variants of a single language. However, their lack of mutual intelligibility means they are sometimes considered separate languages in a family.[e] Investigation of the historical relationships among the varieties of Chinese is ongoing. Currently, most classifications posit 7 to 13 main regional groups based on phonetic developments from Middle Chinese, of which the most spoken by far is Mandarin (with about 800 million speakers, or 66%), followed by Min (75 million, e.g. Southern Min), Wu (74 million, e.g. Shanghainese), and Yue (68 million, e.g. Cantonese). These branches are unintelligible to each other, and many of their subgroups are unintelligible with the other varieties within the same branch (e.g. Southern Min). There are, however, transitional areas where varieties from different branches share enough features for some limited intelligibility, including New Xiang with Southwest Mandarin, Xuanzhou Wu with Lower Yangtze Mandarin, Jin with Central Plains Mandarin and certain divergent dialects of Hakka with Gan (though these are unintelligible with mainstream Hakka). All varieties of Chinese are tonal to at least some degree, and are largely analytic.

The earliest Chinese written records are Shang dynasty-era oracle bone inscriptions, which can be dated to 1250 BCE. The phonetic categories of Old Chinese can be reconstructed from the rhymes of ancient poetry. During the Northern and Southern dynasties period, Middle Chinese went through several sound changes and split into several varieties following prolonged geographic and political separation. Qieyun, a rime dictionary, recorded a compromise between the pronunciations of different regions. The royal courts of the Ming and early Qing dynasties operated using a koiné language (Guanhua) based on Nanjing dialect of Lower Yangtze Mandarin.

Standard Chinese (Standard Mandarin), based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin, was adopted in the 1930s and is now an official language of both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan), one of the four official languages of Singapore, and one of the six official languages of the United Nations. The written form, using the logograms known as Chinese characters, is shared by literate speakers of mutually unintelligible dialects. Since the 1950s, simplified Chinese characters have been promoted for use by the government of the People’s Republic of China, while Singapore officially adopted simplified characters in 1976. Traditional characters remain in use in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and other countries with significant overseas Chinese speaking communities such as Malaysia (which although adopted simplified characters as the de facto standard in the 1980s, traditional characters still remain in widespread use).

Classification[edit]

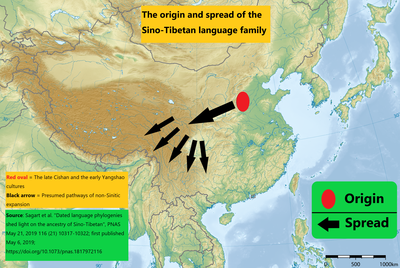

After applying the linguistic comparative method to the database of comparative linguistic data developed by Laurent Sagart in 2019 to identify sound correspondences and establish cognates, phylogenetic methods are used to infer relationships among these languages and estimate the age of their origin and homeland.[4]

Linguists classify all varieties of Chinese as part of the Sino-Tibetan language family, together with Burmese, Tibetan and many other languages spoken in the Himalayas and the Southeast Asian Massif.[5] Although the relationship was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted, reconstruction of Sino-Tibetan is much less developed than that of families such as Indo-European or Austroasiatic. Difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflection in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to reach and are often also sensitive border zones.[6] Without a secure reconstruction of proto-Sino-Tibetan, the higher-level structure of the family remains unclear.[7] A top-level branching into Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages is often assumed, but has not been convincingly demonstrated.[8]

History[edit]

The first written records appeared over 3,000 years ago during the Shang dynasty. As the language evolved over this period, the various local varieties became mutually unintelligible. In reaction, central governments have repeatedly sought to promulgate a unified standard.[9]

Old and Middle Chinese[edit]

The earliest examples of Chinese (Old Chinese) are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BCE in the late Shang dynasty.[10] The next attested stage came from inscriptions on bronze artifacts of the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BCE), the Classic of Poetry and portions of the Book of Documents and I Ching.[11] Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the phonology of Old Chinese by comparing later varieties of Chinese with the rhyming practice of the Classic of Poetry and the phonetic elements found in the majority of Chinese characters.[12] Although many of the finer details remain unclear, most scholars agree that Old Chinese differs from Middle Chinese in lacking retroflex and palatal obstruents but having initial consonant clusters of some sort, and in having voiceless nasals and liquids.[13] Most recent reconstructions also describe an atonal language with consonant clusters at the end of the syllable, developing into tone distinctions in Middle Chinese.[14] Several derivational affixes have also been identified, but the language lacks inflection, and indicated grammatical relationships using word order and grammatical particles.[15]

Middle Chinese was the language used during Northern and Southern dynasties and the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties (6th through 10th centuries CE). It can be divided into an early period, reflected by the Qieyun rime book (601 CE), and a late period in the 10th century, reflected by rhyme tables such as the Yunjing constructed by ancient Chinese philologists as a guide to the Qieyun system.[16] These works define phonological categories, but with little hint of what sounds they represent.[17] Linguists have identified these sounds by comparing the categories with pronunciations in modern varieties of Chinese, borrowed Chinese words in Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean, and transcription evidence.[18] The resulting system is very complex, with a large number of consonants and vowels, but they are probably not all distinguished in any single dialect. Most linguists now believe it represents a diasystem encompassing 6th-century northern and southern standards for reading the classics.[19]

Classical and literary forms[edit]

The relationship between spoken and written Chinese is rather complex («diglossia»). Its spoken varieties have evolved at different rates, while written Chinese itself has changed much less. Classical Chinese literature began in the Spring and Autumn period.

Rise of northern dialects[edit]

After the fall of the Northern Song dynasty and subsequent reign of the Jin (Jurchen) and Yuan (Mongol) dynasties in northern China, a common speech (now called Old Mandarin) developed based on the dialects of the North China Plain around the capital.[20]

The Zhongyuan Yinyun (1324) was a dictionary that codified the rhyming conventions of new sanqu verse form in this language.[21]

Together with the slightly later Menggu Ziyun, this dictionary describes a language with many of the features characteristic of modern Mandarin dialects.[22]

Up to the early 20th century, most Chinese people only spoke their local variety.[23]

Thus, as a practical measure, officials of the Ming and Qing dynasties carried out the administration of the empire using a common language based on Mandarin varieties, known as Guānhuà (官话/官話, literally «language of officials»).[24]

For most of this period, this language was a koiné based on dialects spoken in the Nanjing area, though not identical to any single dialect.[25]

By the middle of the 19th century, the Beijing dialect had become dominant and was essential for any business with the imperial court.[26]

In the 1930s, a standard national language, Guóyǔ (国语/國語 ; «national language») was adopted. After much dispute between proponents of northern and southern dialects and an abortive attempt at an artificial pronunciation, the National Language Unification Commission finally settled on the Beijing dialect in 1932. The People’s Republic founded in 1949 retained this standard but renamed it pǔtōnghuà (普通话/普通話; «common speech»).[27] The national language is now used in education, the media, and formal situations in both Mainland China and Taiwan.[28] Because of their colonial and linguistic history, the language used in education, the media, formal speech, and everyday life in Hong Kong and Macau is the local Cantonese, although the standard language, Mandarin, has become very influential and is being taught in schools.[29]

Influence[edit]

Historically, the Chinese language has spread to its neighbors through a variety of means. Northern Vietnam was incorporated into the Han empire in 111 BCE, marking the beginning of a period of Chinese control that ran almost continuously for a millennium. The Four Commanderies were established in northern Korea in the first century BCE, but disintegrated in the following centuries.[30] Chinese Buddhism spread over East Asia between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE, and with it the study of scriptures and literature in Literary Chinese.[31] Later Korea, Japan, and Vietnam developed strong central governments modeled on Chinese institutions, with Literary Chinese as the language of administration and scholarship, a position it would retain until the late 19th century in Korea and (to a lesser extent) Japan, and the early 20th century in Vietnam.[32] Scholars from different lands could communicate, albeit only in writing, using Literary Chinese.[33]

Although they used Chinese solely for written communication, each country had its own tradition of reading texts aloud, the so-called Sino-Xenic pronunciations. Chinese words with these pronunciations were also extensively imported into the Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese languages, and today comprise over half of their vocabularies.[34] This massive influx led to changes in the phonological structure of the languages, contributing to the development of moraic structure in Japanese[35] and the disruption of vowel harmony in Korean.[36]

Borrowed Chinese morphemes have been used extensively in all these languages to coin compound words for new concepts, in a similar way to the use of Latin and Ancient Greek roots in European languages.[37] Many new compounds, or new meanings for old phrases, were created in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to name Western concepts and artifacts. These coinages, written in shared Chinese characters, have then been borrowed freely between languages. They have even been accepted into Chinese, a language usually resistant to loanwords, because their foreign origin was hidden by their written form. Often different compounds for the same concept were in circulation for some time before a winner emerged, and sometimes the final choice differed between countries.[38] The proportion of vocabulary of Chinese origin thus tends to be greater in technical, abstract, or formal language. For example, in Japan, Sino-Japanese words account for about 35% of the words in entertainment magazines, over half the words in newspapers, and 60% of the words in science magazines.[39]

Vietnam, Korea, and Japan each developed writing systems for their own languages, initially based on Chinese characters, but later replaced with the hangul alphabet for Korean and supplemented with kana syllabaries for Japanese, while Vietnamese continued to be written with the complex chữ nôm script. However, these were limited to popular literature until the late 19th century. Today Japanese is written with a composite script using both Chinese characters (kanji) and kana. Korean is written exclusively with hangul in North Korea (although knowledge of the supplementary Chinese characters — hanja — is still required), and hanja are increasingly rarely used in South Korea. As a result of former French colonization, Vietnamese switched to a Latin-based alphabet.

Examples of loan words in English include «tea», from Hokkien (Min Nan) tê (茶), «dim sum», from Cantonese dim2 sam1 (點心) and «kumquat», from Cantonese gam1gwat1 (金橘).

Varieties[edit]

Range of Chinese dialect groups in China Mainland and Taiwan according to the Language Atlas of China[40]

Jerry Norman estimated that there are hundreds of mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese.[41] These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, though the rate of change varies immensely.[42] Generally, mountainous South China exhibits more linguistic diversity than the North China Plain. In parts of South China, a major city’s dialect may only be marginally intelligible to close neighbors. For instance, Wuzhou is about 190 kilometres (120 mi) upstream from Guangzhou, but the Yue variety spoken there is more like that of Guangzhou than is that of Taishan, 95 kilometres (60 mi) southwest of Guangzhou and separated from it by several rivers.[43] In parts of Fujian the speech of neighboring counties or even villages may be mutually unintelligible.[44]

Until the late 20th century, Chinese emigrants to Southeast Asia and North America came from southeast coastal areas, where Min, Hakka, and Yue dialects are spoken.[45]

The vast majority of Chinese immigrants to North America up to the mid-20th century spoke the Taishan dialect, from a small coastal area southwest of Guangzhou.[46]

Grouping[edit]

Proportions of first-language speakers

Wu (6.1%)

Local varieties of Chinese are conventionally classified into seven dialect groups, largely on the basis of the different evolution of Middle Chinese voiced initials:[47][48]

- Mandarin, including Standard Chinese, Pekingese, Sichuanese, and also the Dungan language spoken in Central Asia

- Wu, including Shanghainese, Suzhounese, and Wenzhounese

- Gan

- Xiang

- Min, including Fuzhounese, Hainanese, Hokkien and Teochew

- Hakka

- Yue, including Cantonese and Taishanese

The classification of Li Rong, which is used in the Language Atlas of China (1987), distinguishes three further groups:[40][49]

- Jin, previously included in Mandarin.

- Huizhou, previously included in Wu.

- Pinghua, previously included in Yue.

Some varieties remain unclassified, including Danzhou dialect (spoken in Danzhou, on Hainan Island), Waxianghua (spoken in western Hunan) and Shaozhou Tuhua (spoken in northern Guangdong).[50]

Standard Chinese[edit]

Standard Chinese, often called Mandarin, is the official standard language of China, de facto official language of Taiwan, and one of the four official languages of Singapore (where it is called «Huáyŭ» 华语/華語 or Chinese). Standard Chinese is based on the Beijing dialect, the dialect of Mandarin as spoken in Beijing. The governments of both China and Taiwan intend for speakers of all Chinese speech varieties to use it as a common language of communication. Therefore, it is used in government agencies, in the media, and as a language of instruction in schools.

In China and Taiwan, diglossia has been a common feature. For example, in addition to Standard Chinese, a resident of Shanghai might speak Shanghainese; and, if they grew up elsewhere, then they are also likely to be fluent in the particular dialect of that local area. A native of Guangzhou may speak both Cantonese and Standard Chinese. In addition to Mandarin, most Taiwanese also speak Taiwanese Hokkien (commonly «Taiwanese» 台語[51][52]), Hakka, or an Austronesian language.[53] A Taiwanese may commonly mix pronunciations, phrases, and words from Mandarin and other Taiwanese languages, and this mixture is considered normal in daily or informal speech.[54]

Due to their traditional cultural ties to Guangdong province and colonial histories, Cantonese is used as the standard variant of Chinese in Hong Kong and Macau instead.

Nomenclature[edit]

The official Chinese designation for the major branches of Chinese is fāngyán (方言, literally «regional speech»), whereas the more closely related varieties within these are called dìdiǎn fāngyán (地点方言/地點方言 «local speech»).[55] Conventional English-language usage in Chinese linguistics is to use dialect for the speech of a particular place (regardless of status) and dialect group for a regional grouping such as Mandarin or Wu.[41] Because varieties from different groups are not mutually intelligible, some scholars prefer to describe Wu and others as separate languages.[56][better source needed] Jerry Norman called this practice misleading, pointing out that Wu, which itself contains many mutually unintelligible varieties, could not be properly called a single language under the same criterion, and that the same is true for each of the other groups.[41]

Mutual intelligibility is considered by some linguists to be the main criterion for determining whether varieties are separate languages or dialects of a single language,[57] although others do not regard it as decisive,[58][59][60][61][62] particularly when cultural factors interfere as they do with Chinese.[63] As Campbell (2008) explains, linguists often ignore mutual intelligibility when varieties share intelligibility with a central variety (i.e. prestige variety, such as Standard Mandarin), as the issue requires some careful handling when mutual intelligibility is inconsistent with language identity.[64] John DeFrancis argues that it is inappropriate to refer to Mandarin, Wu and so on as «dialects» because the mutual unintelligibility between them is too great. On the other hand, he also objects to considering them as separate languages, as it incorrectly implies a set of disruptive «religious, economic, political, and other differences» between speakers that exist, for example, between French Catholics and English Protestants in Canada, but not between speakers of Cantonese and Mandarin in China, owing to China’s near-uninterrupted history of centralized government.[65]

Because of the difficulties involved in determining the difference between language and dialect, other terms have been proposed. These include vernacular,[66] lect,[67] regionalect,[55] topolect,[68] and variety.[69]

Most Chinese people consider the spoken varieties as one single language because speakers share a common culture and history, as well as a shared national identity and a common written form.[70]

Phonology[edit]

Syllables in the Chinese languages have some unique characteristics. They are tightly related to the morphology and also to the characters of the writing system; and phonologically they are structured according to fixed rules.

The structure of each syllable consists of a nucleus that has a vowel (which can be a monophthong, diphthong, or even a triphthong in certain varieties), preceded by an onset (a single consonant, or consonant+glide; zero onset is also possible), and followed (optionally) by a coda consonant; a syllable also carries a tone. There are some instances where a vowel is not used as a nucleus. An example of this is in Cantonese, where the nasal sonorant consonants /m/ and /ŋ/ can stand alone as their own syllable.

In Mandarin much more than in other spoken varieties, most syllables tend to be open syllables, meaning they have no coda (assuming that a final glide is not analyzed as a coda), but syllables that do have codas are restricted to nasals /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, the retroflex approximant /ɻ/, and voiceless stops /p/, /t/, /k/, or /ʔ/. Some varieties allow most of these codas, whereas others, such as Standard Chinese, are limited to only /n/, /ŋ/, and /ɻ/.

The number of sounds in the different spoken dialects varies, but in general there has been a tendency to a reduction in sounds from Middle Chinese. The Mandarin dialects in particular have experienced a dramatic decrease in sounds and so have far more multisyllabic words than most other spoken varieties. The total number of syllables in some varieties is therefore only about a thousand, including tonal variation, which is only about an eighth as many as English.[f]

Tones[edit]

All varieties of spoken Chinese use tones to distinguish words.[71] A few dialects of north China may have as few as three tones, while some dialects in south China have up to 6 or 12 tones, depending on how one counts. One exception from this is Shanghainese which has reduced the set of tones to a two-toned pitch accent system much like modern Japanese.

A very common example used to illustrate the use of tones in Chinese is the application of the four tones of Standard Chinese (along with the neutral tone) to the syllable ma. The tones are exemplified by the following five Chinese words:

The four main tones of Standard Mandarin, pronounced with the syllable ma.

| Characters | Pinyin | Pitch contour | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 妈/媽 | mā | high level | ‘mother’ |

| 麻 | má | high rising | ‘hemp’ |

| 马/馬 | mǎ | low falling-rising | ‘horse’ |

| 骂/罵 | mà | high falling | ‘scold’ |

| 吗/嗎 | ma | neutral | question particle |

Standard Cantonese, in contrast, has six tones. Historically, finals that end in a stop consonant were considered to be «checked tones» and thus counted separately for a total of nine tones. However, they are considered to be duplicates in modern linguistics and are no longer counted as such:[72]

| Characters | Jyutping | Yale | Pitch contour | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 诗/詩 | si1 | sī | high level, high falling | ‘poem’ |

| 史 | si2 | sí | high rising | ‘history’ |

| 弒 | si3 | si | mid level | ‘to assassinate’ |

| 时/時 | si4 | sìh | low falling | ‘time’ |

| 市 | si5 | síh | low rising | ‘market’ |

| 是 | si6 | sih | low level | ‘yes’ |

Grammar[edit]

Chinese is often described as a «monosyllabic» language. However, this is only partially correct. It is largely accurate when describing Classical Chinese and Middle Chinese; in Classical Chinese, for example, perhaps 90% of words correspond to a single syllable and a single character. In the modern varieties, it is usually the case that a morpheme (unit of meaning) is a single syllable; in contrast, English has many multi-syllable morphemes, both bound and free, such as «seven», «elephant», «para-» and «-able».

Some of the conservative southern varieties of modern Chinese have largely monosyllabic words, especially among the more basic vocabulary. In modern Mandarin, however, most nouns, adjectives and verbs are largely disyllabic. A significant cause of this is phonological attrition. Sound change over time has steadily reduced the number of possible syllables. In modern Mandarin, there are now only about 1,200 possible syllables, including tonal distinctions, compared with about 5,000 in Vietnamese (still largely monosyllabic) and over 8,000 in English.[f]

This phonological collapse has led to a corresponding increase in the number of homophones. As an example, the small Langenscheidt Pocket Chinese Dictionary[73] lists six words that are commonly pronounced as shí (tone 2): 十 ‘ten’; 实/實 ‘real, actual’; 识/識 ‘know (a person), recognize’; 石 ‘stone’; 时/時 ‘time’; 食 ‘food, eat’. These were all pronounced differently in Early Middle Chinese; in William H. Baxter’s transcription they were dzyip, zyit, syik, dzyek, dzyi and zyik respectively. They are still pronounced differently in today’s Cantonese; in Jyutping they are sap9, sat9, sik7, sek9, si4, sik9. In modern spoken Mandarin, however, tremendous ambiguity would result if all of these words could be used as-is; Yuen Ren Chao’s modern poem Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den exploits this, consisting of 92 characters all pronounced shi. As such, most of these words have been replaced (in speech, if not in writing) with a longer, less-ambiguous compound. Only the first one, 十 ‘ten’, normally appears as such when spoken; the rest are normally replaced with, respectively, shíjì 实际/實際 (lit. ‘actual-connection’); rènshi 认识/認識 (lit. ‘recognize-know’); shítou 石头/石頭 (lit. ‘stone-head’); shíjiān 时间/時間 (lit. ‘time-interval’); shíwù 食物 (lit. ‘foodstuff’). In each case, the homophone was disambiguated by adding another morpheme, typically either a synonym or a generic word of some sort (for example, ‘head’, ‘thing’), the purpose of which is to indicate which of the possible meanings of the other, homophonic syllable should be selected.

However, when one of the above words forms part of a compound, the disambiguating syllable is generally dropped and the resulting word is still disyllabic. For example, shí 石 alone, not shítou 石头/石頭, appears in compounds meaning ‘stone-‘, for example, shígāo 石膏 ‘plaster’ (lit. ‘stone cream’), shíhuī 石灰 ‘lime’ (lit. ‘stone dust’), shíkū 石窟 ‘grotto’ (lit. ‘stone cave’), shíyīng 石英 ‘quartz’ (lit. ‘stone flower’), shíyóu 石油 ‘petroleum’ (lit. ‘stone oil’).

Most modern varieties of Chinese have the tendency to form new words through disyllabic, trisyllabic and tetra-character compounds. In some cases, monosyllabic words have become disyllabic without compounding, as in kūlong 窟窿 from kǒng 孔; this is especially common in Jin.

Chinese morphology is strictly bound to a set number of syllables with a fairly rigid construction. Although many of these single-syllable morphemes (zì, 字) can stand alone as individual words, they more often than not form multi-syllabic compounds, known as cí (词/詞), which more closely resembles the traditional Western notion of a word. A Chinese cí (‘word’) can consist of more than one character-morpheme, usually two, but there can be three or more.

For example:

- yún 云/雲 ‘cloud’

- hànbǎobāo, hànbǎo 汉堡包/漢堡包, 汉堡/漢堡 ‘hamburger’

- wǒ 我 ‘I, me’

- shǒuményuán 守门员/守門員 ‘goalkeeper’

- rén 人 ‘people, human, mankind’

- dìqiú 地球 ‘The Earth’

- shǎndiàn 闪电/閃電 ‘lightning’

- mèng 梦/夢 ‘dream’

All varieties of modern Chinese are analytic languages, in that they depend on syntax (word order and sentence structure) rather than morphology—i.e., changes in form of a word—to indicate the word’s function in a sentence.[74] In other words, Chinese has very few grammatical inflections—it possesses no tenses, no voices, no numbers (singular, plural; though there are plural markers, for example for personal pronouns), and only a few articles (i.e., equivalents to «the, a, an» in English).[g]

They make heavy use of grammatical particles to indicate aspect and mood. In Mandarin Chinese, this involves the use of particles like le 了 (perfective), hái 还/還 (‘still’), yǐjīng 已经/已經 (‘already’), and so on.

Chinese has a subject–verb–object word order, and like many other languages of East Asia, makes frequent use of the topic–comment construction to form sentences. Chinese also has an extensive system of classifiers and measure words, another trait shared with neighboring languages like Japanese and Korean. Other notable grammatical features common to all the spoken varieties of Chinese include the use of serial verb construction, pronoun dropping and the related subject dropping.

Although the grammars of the spoken varieties share many traits, they do possess differences.

Vocabulary[edit]

The entire Chinese character corpus since antiquity comprises well over 50,000 characters, of which only roughly 10,000 are in use and only about 3,000 are frequently used in Chinese media and newspapers.[75] However Chinese characters should not be confused with Chinese words. Because most Chinese words are made up of two or more characters, there are many more Chinese words than characters. A more accurate equivalent for a Chinese character is the morpheme, as characters represent the smallest grammatical units with individual meanings in the Chinese language.

Estimates of the total number of Chinese words and lexicalized phrases vary greatly. The Hanyu Da Zidian, a compendium of Chinese characters, includes 54,678 head entries for characters, including bone oracle versions. The Zhonghua Zihai (1994) contains 85,568 head entries for character definitions, and is the largest reference work based purely on character and its literary variants. The CC-CEDICT project (2010) contains 97,404 contemporary entries including idioms, technology terms and names of political figures, businesses and products. The 2009 version of the Webster’s Digital Chinese Dictionary (WDCD),[76] based on CC-CEDICT, contains over 84,000 entries.

The most comprehensive pure linguistic Chinese-language dictionary, the 12-volume Hanyu Da Cidian, records more than 23,000 head Chinese characters and gives over 370,000 definitions. The 1999 revised Cihai, a multi-volume encyclopedic dictionary reference work, gives 122,836 vocabulary entry definitions under 19,485 Chinese characters, including proper names, phrases and common zoological, geographical, sociological, scientific and technical terms.

The 7th (2016) edition of Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, an authoritative one-volume dictionary on modern standard Chinese language as used in mainland China, has 13,000 head characters and defines 70,000 words.

Loanwords[edit]

Like any other language, Chinese has absorbed a sizable number of loanwords from other cultures. Most Chinese words are formed out of native Chinese morphemes, including words describing imported objects and ideas. However, direct phonetic borrowing of foreign words has gone on since ancient times.

Some early Indo-European loanwords in Chinese have been proposed, notably 蜜 mì «honey», 狮/獅 shī «lion,» and perhaps also 马/馬 mǎ «horse», 猪/豬 zhū «pig», 犬 quǎn «dog», and 鹅/鵝 é «goose».[h]

Ancient words borrowed from along the Silk Road since Old Chinese include 葡萄 pútáo «grape», 石榴 shíliu/shíliú «pomegranate» and 狮子/獅子 shīzi «lion». Some words were borrowed from Buddhist scriptures, including 佛 Fó «Buddha» and 菩萨/菩薩 Púsà «bodhisattva.» Other words came from nomadic peoples to the north, such as 胡同 hútòng «hutong». Words borrowed from the peoples along the Silk Road, such as 葡萄 «grape,» generally have Persian etymologies. Buddhist terminology is generally derived from Sanskrit or Pāli, the liturgical languages of North India. Words borrowed from the nomadic tribes of the Gobi, Mongolian or northeast regions generally have Altaic etymologies, such as 琵琶 pípá, the Chinese lute, or 酪 lào/luò «cheese» or «yogurt», but from exactly which source is not always clear.[77]

Modern borrowings[edit]

Modern neologisms are primarily translated into Chinese in one of three ways: free translation (calque, or by meaning), phonetic translation (by sound), or a combination of the two. Today, it is much more common to use existing Chinese morphemes to coin new words to represent imported concepts, such as technical expressions and international scientific vocabulary. Any Latin or Greek etymologies are dropped and converted into the corresponding Chinese characters (for example, anti- typically becomes «反«, literally opposite), making them more comprehensible for Chinese but introducing more difficulties in understanding foreign texts. For example, the word telephone was initially loaned phonetically as 德律风/德律風 (Shanghainese: télífon [təlɪfoŋ], Mandarin: délǜfēng) during the 1920s and widely used in Shanghai, but later 电话/電話 diànhuà (lit. «electric speech»), built out of native Chinese morphemes, became prevalent (電話 is in fact from the Japanese 電話 denwa; see below for more Japanese loans). Other examples include 电视/電視 diànshì (lit. «electric vision») for television, 电脑/電腦 diànnǎo (lit. «electric brain») for computer; 手机/手機 shǒujī (lit. «hand machine») for mobile phone, 蓝牙/藍牙 lányá (lit. «blue tooth») for Bluetooth, and 网志/網誌 wǎngzhì (lit. «internet logbook») for blog in Hong Kong and Macau Cantonese. Occasionally half-transliteration, half-translation compromises are accepted, such as 汉堡包/漢堡包 hànbǎobāo (漢堡 hànbǎo «Hamburg» + 包 bāo «bun») for «hamburger». Sometimes translations are designed so that they sound like the original while incorporating Chinese morphemes (phono-semantic matching), such as 马利奥/馬利奧 Mǎlì’ào for the video game character Mario. This is often done for commercial purposes, for example 奔腾/奔騰 bēnténg (lit. «dashing-leaping») for Pentium and 赛百味/賽百味 Sàibǎiwèi (lit. «better-than hundred tastes») for Subway restaurants.

Foreign words, mainly proper nouns, continue to enter the Chinese language by transcription according to their pronunciations. This is done by employing Chinese characters with similar pronunciations. For example, «Israel» becomes 以色列 Yǐsèliè, «Paris» becomes 巴黎 Bālí. A rather small number of direct transliterations have survived as common words, including 沙发/沙發 shāfā «sofa», 马达/馬達 mǎdá «motor», 幽默 yōumò «humor», 逻辑/邏輯 luóji/luójí «logic», 时髦/時髦 shímáo «smart, fashionable», and 歇斯底里 xiēsīdǐlǐ «hysterics». The bulk of these words were originally coined in the Shanghai dialect during the early 20th century and were later loaned into Mandarin, hence their pronunciations in Mandarin may be quite off from the English. For example, 沙发/沙發 «sofa» and 马达/馬達 «motor» in Shanghainese sound more like their English counterparts. Cantonese differs from Mandarin with some transliterations, such as 梳化 so1 faa3*2 «sofa» and 摩打 mo1 daa2 «motor».

Western foreign words representing Western concepts have influenced Chinese since the 20th century through transcription. From French came 芭蕾 bālěi «ballet» and 香槟/香檳 xiāngbīn, «champagne»; from Italian, 咖啡 kāfēi «caffè». English influence is particularly pronounced. From early 20th century Shanghainese, many English words are borrowed, such as 高尔夫/高爾夫 gāoěrfū «golf» and the above-mentioned 沙发/沙發 shāfā «sofa». Later, the United States soft influences gave rise to 迪斯科 dísikē/dísīkē «disco», 可乐/可樂 kělè «cola», and 迷你 mínǐ «mini [skirt]». Contemporary colloquial Cantonese has distinct loanwords from English, such as 卡通 kaa1 tung1 «cartoon», 基佬 gei1 lou2 «gay people», 的士 dik1 si6*2 «taxi», and 巴士 baa1 si6*2 «bus». With the rising popularity of the Internet, there is a current vogue in China for coining English transliterations, for example, 粉丝/粉絲 fěnsī «fans», 黑客 hēikè «hacker» (lit. «black guest»), and 博客 bókè «blog». In Taiwan, some of these transliterations are different, such as 駭客 hàikè for «hacker» and 部落格 bùluògé for «blog» (lit. «interconnected tribes»).

Another result of the English influence on Chinese is the appearance in Modern Chinese texts of so-called 字母词/字母詞 zìmǔcí (lit. «lettered words») spelled with letters from the English alphabet. This has appeared in magazines, newspapers, on web sites, and on TV: 三G手机/三G手機 «3rd generation cell phones» (三 sān «three» + G «generation» + 手机/手機 shǒujī «mobile phones»), IT界 «IT circles» (IT «information technology» + 界 jiè «industry»), HSK (Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì, 汉语水平考试/漢語水平考試), GB (Guóbiāo, 国标/國標), CIF价/CIF價 (CIF «Cost, Insurance, Freight» + 价/價 jià «price»), e家庭 «e-home» (e «electronic» + 家庭 jiātíng «home»), Chinese: W时代/Chinese: W時代 «wireless era» (W «wireless» + 时代/時代 shídài «era»), TV族 «TV watchers» (TV «television» + 族 zú «social group; clan»), 后РС时代/後PC時代 «post-PC era» (后/後 hòu «after/post-» + PC «personal computer» + 时代/時代), and so on.

Since the 20th century, another source of words has been Japanese using existing kanji (Chinese characters used in Japanese). Japanese re-molded European concepts and inventions into wasei-kango (和製漢語, lit. «Japanese-made Chinese»), and many of these words have been re-loaned into modern Chinese. Other terms were coined by the Japanese by giving new senses to existing Chinese terms or by referring to expressions used in classical Chinese literature. For example, jīngjì (经济/經濟; 経済 keizai in Japanese), which in the original Chinese meant «the workings of the state», was narrowed to «economy» in Japanese; this narrowed definition was then reimported into Chinese. As a result, these terms are virtually indistinguishable from native Chinese words: indeed, there is some dispute over some of these terms as to whether the Japanese or Chinese coined them first. As a result of this loaning, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese share a corpus of linguistic terms describing modern terminology, paralleling the similar corpus of terms built from Greco-Latin and shared among European languages.

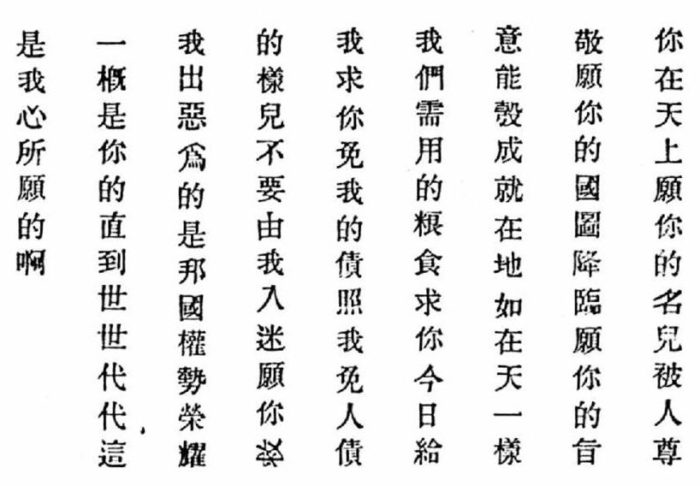

Writing system[edit]

The Chinese orthography centers on Chinese characters, which are written within imaginary square blocks, traditionally arranged in vertical columns, read from top to bottom down a column, and right to left across columns, despite alternative arrangement with rows of characters from left to right within a row and from top to bottom across rows (like English and other Western writing systems) having become more popular since the 20th century.[78] Chinese characters denote morphemes independent of phonetic variation in different languages. Thus the character 一 («one») is uttered yī in Standard Chinese, yat1 in Cantonese and it in Hokkien (a form of Min).

Most written Chinese documents in the modern time, especially the more formal ones, are created using the grammar and syntax of the Standard Mandarin Chinese variants, regardless of dialectical background of the author or targeted audience. This replaced the old writing language standard of Literary Chinese before the 20th century.[79] However, vocabularies from different Chinese-speaking areas have diverged, and the divergence can be observed in written Chinese.[80]

Meanwhile, colloquial forms of various Chinese language variants have also been written down by their users, especially in less formal settings. The most prominent example of this is the written colloquial form of Cantonese, which has become quite popular in tabloids, instant messaging applications, and on the internet amongst Hong-Kongers and Cantonese-speakers elsewhere.[81]

Because some Chinese variants have diverged and developed a number of unique morphemes that are not found in Standard Mandarin (despite all other common morphemes), unique characters rarely used in Standard Chinese have also been created or inherited from archaic literary standard to represent these unique morphemes. For example, characters like 冇 and 係 for Cantonese and Hakka, are actively used in both languages while being considered archaic or unused in standard written Chinese.

The Chinese had no uniform phonetic transcription system for most of its speakers until the mid-20th century, although enunciation patterns were recorded in early rime books and dictionaries. Early Indian translators, working in Sanskrit and Pali, were the first to attempt to describe the sounds and enunciation patterns of Chinese in a foreign language. After the 15th century, the efforts of Jesuits and Western court missionaries resulted in some Latin character transcription/writing systems, based on various variants of Chinese languages. Some of these Latin character based systems are still being used to write various Chinese variants in the modern era.[82]

In Hunan, women in certain areas write their local Chinese language variant in Nü Shu, a syllabary derived from Chinese characters. The Dungan language, considered by many a dialect of Mandarin, is nowadays written in Cyrillic, and was previously written in the Arabic script. The Dungan people are primarily Muslim and live mainly in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia; some of the related Hui people also speak the language and live mainly in China.

Chinese characters[edit]

永 (meaning «forever») is often used to illustrate the eight basic types of strokes of Chinese characters.

Each Chinese character represents a monosyllabic Chinese word or morpheme. In 100 CE, the famed Han dynasty scholar Xu Shen classified characters into six categories, namely pictographs, simple ideographs, compound ideographs, phonetic loans, phonetic compounds and derivative characters. Of these, only 4% were categorized as pictographs, including many of the simplest characters, such as rén 人 (human), rì 日 (sun), shān 山 (mountain; hill), shuǐ 水 (water). Between 80% and 90% were classified as phonetic compounds such as chōng 沖 (pour), combining a phonetic component zhōng 中 (middle) with a semantic radical 氵 (water). Almost all characters created since have been made using this format. The 18th-century Kangxi Dictionary recognized 214 radicals.

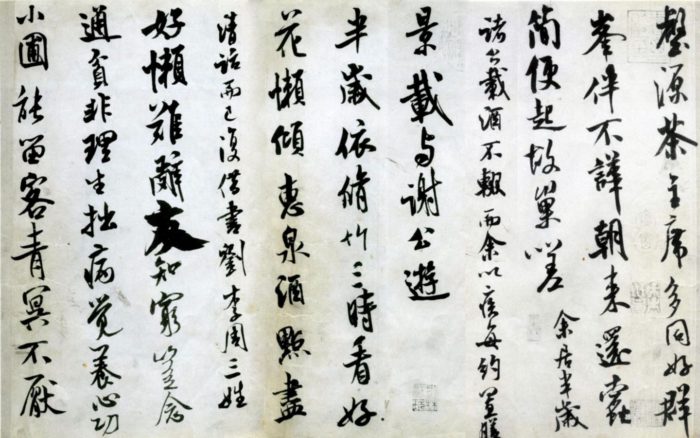

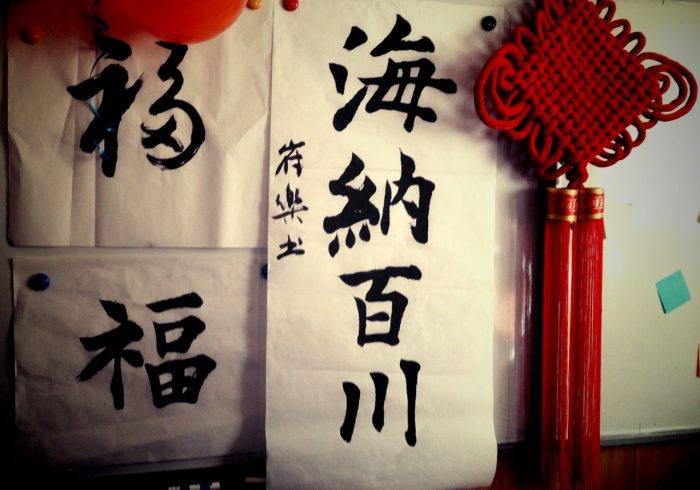

Modern characters are styled after the regular script. Various other written styles are also used in Chinese calligraphy, including seal script, cursive script and clerical script. Calligraphy artists can write in traditional and simplified characters, but they tend to use traditional characters for traditional art.

There are currently two systems for Chinese characters. The traditional system, used in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and Chinese speaking communities (except Singapore and Malaysia) outside mainland China, takes its form from standardized character forms dating back to the late Han dynasty. The Simplified Chinese character system, introduced by the People’s Republic of China in 1954 to promote mass literacy, simplifies most complex traditional glyphs to fewer strokes, many to common cursive shorthand variants. Singapore, which has a large Chinese community, was the second nation to officially adopt simplified characters, although it has also become the de facto standard for younger ethnic Chinese in Malaysia.

The Internet provides the platform to practice reading these alternative systems, be it traditional or simplified. Most Chinese users in the modern era are capable of, although not necessarily comfortable with, reading (but not writing) the alternative system, through experience and guesswork.[83]

A well-educated Chinese reader today recognizes approximately 4,000 to 6,000 characters; approximately 3,000 characters are required to read a Mainland newspaper. The PRC government defines literacy amongst workers as a knowledge of 2,000 characters, though this would be only functional literacy. School-children typically learn around 2,000 characters whereas scholars may memorize up to 10,000.[84] A large unabridged dictionary, like the Kangxi Dictionary, contains over 40,000 characters, including obscure, variant, rare, and archaic characters; fewer than a quarter of these characters are now commonly used.

Romanization[edit]

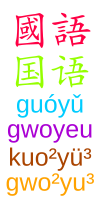

«National language» (國語/国语; Guóyǔ) written in Traditional and Simplified Chinese characters, followed by various romanizations.

Romanization is the process of transcribing a language into the Latin script. There are many systems of romanization for the Chinese varieties, due to the lack of a native phonetic transcription until modern times. Chinese is first known to have been written in Latin characters by Western Christian missionaries in the 16th century.

Today the most common romanization standard for Standard Mandarin is Hanyu Pinyin, introduced in 1956 by the People’s Republic of China, and later adopted by Singapore and Taiwan. Pinyin is almost universally employed now for teaching standard spoken Chinese in schools and universities across the Americas, Australia, and Europe. Chinese parents also use Pinyin to teach their children the sounds and tones of new words. In school books that teach Chinese, the Pinyin romanization is often shown below a picture of the thing the word represents, with the Chinese character alongside.

The second-most common romanization system, the Wade–Giles, was invented by Thomas Wade in 1859 and modified by Herbert Giles in 1892. As this system approximates the phonology of Mandarin Chinese into English consonants and vowels, i.e. it is largely an Anglicization, it may be particularly helpful for beginner Chinese speakers of an English-speaking background. Wade–Giles was found in academic use in the United States, particularly before the 1980s, and until 2009 was widely used in Taiwan.

When used within European texts, the tone transcriptions in both pinyin and Wade–Giles are often left out for simplicity; Wade–Giles’ extensive use of apostrophes is also usually omitted. Thus, most Western readers will be much more familiar with Beijing than they will be with Běijīng (pinyin), and with Taipei than T’ai²-pei³ (Wade–Giles). This simplification presents syllables as homophones which really are none, and therefore exaggerates the number of homophones almost by a factor of four.

Here are a few examples of Hanyu Pinyin and Wade–Giles, for comparison:

| Characters | Wade–Giles | Pinyin | Meaning/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 中国/中國 | Chung¹-kuo² | Zhōngguó | China |

| 台湾/台灣 | T’ai²-wan¹ | Táiwān | Taiwan |

| 北京 | Pei³-ching¹ | Běijīng | Beijing |

| 台北/臺北 | T’ai²-pei³ | Táiběi | Taipei |

| 孫文 | Sun¹-wên² | Sūn Wén | Sun Yat-sen |

| 毛泽东/毛澤東 | Mao² Tse²-tung¹ | Máo Zédōng | Mao Zedong, Former Communist Chinese leader |

| 蒋介石/蔣介石 | Chiang³ Chieh⁴-shih² | Jiǎng Jièshí | Chiang Kai-shek, Former Nationalist Chinese leader |

| 孔子 | K’ung³ Tsu³ | Kǒngzǐ | Confucius |

Other systems of romanization for Chinese include Gwoyeu Romatzyh, the French EFEO, the Yale system (invented during WWII for U.S. troops), as well as separate systems for Cantonese, Min Nan, Hakka, and other Chinese varieties.

Other phonetic transcriptions[edit]

Chinese varieties have been phonetically transcribed into many other writing systems over the centuries. The ‘Phags-pa script, for example, has been very helpful in reconstructing the pronunciations of premodern forms of Chinese.

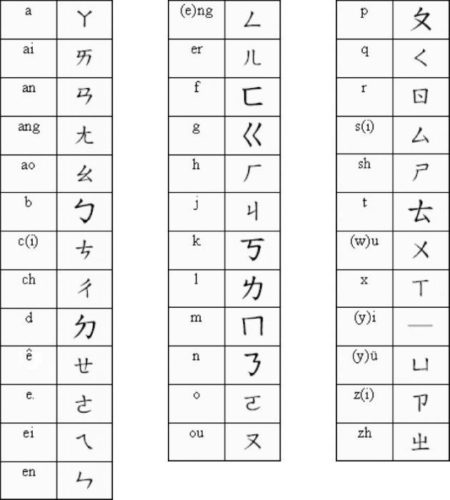

Zhuyin (colloquially bopomofo), a semi-syllabary is still widely used in Taiwan’s elementary schools to aid standard pronunciation. Although zhuyin characters are reminiscent of katakana script, there is no source to substantiate the claim that Katakana was the basis for the zhuyin system. A comparison table of zhuyin to pinyin exists in the zhuyin article. Syllables based on pinyin and zhuyin can also be compared by looking at the following articles:

- Pinyin table

- Zhuyin table

There are also at least two systems of cyrillization for Chinese. The most widespread is the Palladius system.

As a foreign language[edit]

With the growing importance and influence of China’s economy globally, Mandarin instruction has been gaining popularity in schools throughout East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Western world.[85]

Besides Mandarin, Cantonese is the only other Chinese language that is widely taught as a foreign language, largely due to the economic and cultural influence of Hong Kong and its widespread usage among significant Overseas Chinese communities.[86]

In 1991 there were 2,000 foreign learners taking China’s official Chinese Proficiency Test (also known as HSK, comparable to the English Cambridge Certificate), then the number of candidates had risen sharply to 117,660 in 2005[87] and 750,000 in 2010.[88]

See also[edit]

- Chinese exclamative particles

- Chinese honorifics

- Chinese numerals

- Chinese punctuation

- Classical Chinese grammar

- Four-character idiom

- Han unification

- Languages of China

- North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics

- Protection of the Varieties of Chinese

Notes[edit]

- ^ De facto – while no specific variety of Chinese is official in Hong Kong and Macau, Cantonese is the predominant spoken form and the de facto regional standard, written in traditional Chinese characters. Standard Mandarin and simplified Chinese characters are only occasionally used in some official and educational settings. The HK SAR Government promotes 兩文三語 [Biliteracy (Chinese, English) and Trilingualism (Cantonese, Mandarin, English)], while the Macau SAR Government promotes 三文四語 [Triliteracy (Chinese, Portuguese, English) and Quadrilingualism (Cantonese, Mandarin, Portuguese, English)], especially in public education.

- ^ lit. «Han language»

- ^ simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語; pinyin: Hànyǔ[b]

- ^ lit. «Chinese writing»

- ^ Various examples include:

- David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), p. 312. «The mutual unintelligibility of the varieties is the main ground for referring to them as separate languages.»

- Charles N. Li, Sandra A. Thompson. Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar (1989), p. 2. «The Chinese language family is genetically classified as an independent branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family.»

- Norman (1988), p. 1. «[…] the modern Chinese dialects are really more like a family of languages […]»

- DeFrancis (1984), p. 56. «To call Chinese a single language composed of dialects with varying degrees of difference is to mislead by minimizing disparities that according to Chao are as great as those between English and Dutch. To call Chinese a family of languages is to suggest extralinguistic differences that in fact do not exist and to overlook the unique linguistic situation that exists in China.»

Linguists in China often use a formulation introduced by Fu Maoji in the Encyclopedia of China: «汉语在语言系属分类中相当于一个语族的地位。» («In language classification, Chinese has a status equivalent to a language family.»)[2]

- ^ a b DeFrancis (1984), p. 42 counts Chinese as having 1,277 tonal syllables, and about 398 to 418 if tones are disregarded; he cites Jespersen, Otto (1928) Monosyllabism in English; London, p. 15 for a count of over 8000 syllables for English.

- ^ A distinction is made between 他 as ‘he’ and 她 as ‘she’ in writing, but this is a 20th-century introduction, and both characters are pronounced in exactly the same way.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica s.v. «Chinese languages»: «Old Chinese vocabulary already contained many words not generally occurring in the other Sino-Tibetan languages. The words for ‘honey’ and ‘lion’, and probably also ‘horse’, ‘dog’, and ‘goose’, are connected with Indo-European and were acquired through trade and early contacts. (The nearest known Indo-European languages were Tocharian and Sogdian, a middle Iranian language.) A number of words have Austroasiatic cognates and point to early contacts with the ancestral language of Muong–Vietnamese and Mon–Khmer.»; Jan Ulenbrook, Einige Übereinstimmungen zwischen dem Chinesischen und dem Indogermanischen (1967) proposes 57 items; see also Tsung-tung Chang, 1988 Indo-European Vocabulary in Old Chinese.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Summary by language size». Ethnologue. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Mair (1991), pp. 10, 21.

- ^ Sagart et al. (2019), pp. 10319–10320.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Handel (2008), pp. 422, 434–436.

- ^ Handel (2008), p. 426.

- ^ Handel (2008), p. 431.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 183–185.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 1.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 42–45.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 177.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 181–183.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 12.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 125.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 34–42.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 24.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 48.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 49–51.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 133, 247.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 136.

- ^ Coblin (2000), pp. 549–550.

- ^ Coblin (2000), pp. 540–541.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), pp. 3–15.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 133.

- ^ Zhang & Yang (2004).

- ^ Sohn & Lee (2003), p. 23.

- ^ Miller (1967), pp. 29–30.

- ^ Kornicki (2011), pp. 75–77.

- ^ Kornicki (2011), p. 67.

- ^ Miyake (2004), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Shibatani (1990), pp. 120–121.

- ^ Sohn (2001), p. 89.

- ^ Shibatani (1990), p. 146.

- ^ Wilkinson (2000), p. 43.

- ^ Shibatani (1990), p. 143.

- ^ a b Wurm et al. (1987).

- ^ a b c Norman (2003), p. 72.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 189–190.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 23.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 188.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 191.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 98.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 181.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 53–55.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 72–73.

- ^ 何, 信翰 (10 August 2019). «自由廣場》Taigi與台語». 自由時報. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ 李, 淑鳳 (1 March 2010). «台、華語接觸所引起的台語語音的變化趨勢». 台語研究. 2 (1): 56–71. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Klöter, Henning (2004). «Language Policy in the KMT and DPP eras». China Perspectives. 56. ISSN 1996-4617. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Kuo, Yun-Hsuan (2005). New dialect formation: the case of Taiwanese Mandarin (PhD). University of Essex. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ a b DeFrancis (1984), p. 57.

- ^ Thomason (1988), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Mair (1991), p. 17.

- ^ DeFrancis (1984), p. 54.

- ^ Romaine (2000), pp. 13, 23.

- ^ Wardaugh & Fuller (2014), pp. 28–32.

- ^ Liang (2014), pp. 11–14.

- ^ Hymes (1971), p. 64.

- ^ Thomason (1988), p. 27.

- ^ Campbell (2008), p. 637.

- ^ DeFrancis (1984), pp. 55–57.

- ^ Haugen (1966), p. 927.

- ^ Bailey (1973:11), cited in Groves (2008:1)

- ^ Mair (1991), p. 7.

- ^ Hudson (1996), p. 22.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 7–8.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 52.

- ^ Matthews & Yip (1994), pp. 20–22.

- ^ Terrell, Peter, ed. (2005). Langenscheidt Pocket Chinese Dictionary. Berlin and Munich: Langenscheidt KG. ISBN 978-1-58573-057-5.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 10.

- ^ «BBC — Languages — Real Chinese — Mini-guides — Chinese characters». www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Dr. Timothy Uy and Jim Hsia, Editors, Webster’s Digital Chinese Dictionary – Advanced Reference Edition, July 2009

- ^ Kane (2006), p. 161.

- ^ Requirements for Chinese Text Layout 中文排版需求.

- ^ 黃華. «白話為何在五四時期「活」起來了?» (PDF). Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ^ 粵普之爭 為你中文解毒.

- ^ 粤语:中国最强方言是如何炼成的_私家历史_澎湃新闻-The Paper. The Paper.

- ^ «白話字滄桑 — 陳宇碩 — 新使者雜誌 The New Messenger 125期 母語的將來». newmsgr.pct.org.tw.

- ^ «全球華文網-華文世界,數位之最».

- ^ Zimmermann, Basile (2010). «Redesigning Culture: Chinese Characters in Alphabet-Encoded Networks». Design and Culture. 2 (1): 27–43. doi:10.2752/175470710X12593419555126. S2CID 53981784.

- ^ «How hard is it to learn Chinese?». BBC News. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Wakefield, John C., Cantonese as a Second Language: Issues, Experiences and Suggestions for Teaching and Learning (Routledge Studies in Applied Linguistics), Routledge, New York City, 2019., p.45

- ^ (in Chinese) «汉语水平考试中心:2005年外国考生总人数近12万»,Gov.cn Xinhua News Agency, 16 January 2006.

- ^ Liu lili (27 June 2011). «Chinese language proficiency test becoming popular in Mexico». Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

Sources[edit]

- Bailey, Charles-James N. (1973), Variation and Linguistic Theory, Arlington, VA: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Campbell, Lyle (2008), «[Untitled review of Ethnologue, 15th edition]», Language, 84 (3): 636–641, doi:10.1353/lan.0.0054, S2CID 143663395.

- Chappell, Hilary (2008), «Variation in the grammaticalization of complementizers from verba dicendi in Sinitic languages», Linguistic Typology, 12 (1): 45–98, doi:10.1515/lity.2008.032, S2CID 201097561.

- Coblin, W. South (2000), «A brief history of Mandarin», Journal of the American Oriental Society, 120 (4): 537–552, doi:10.2307/606615, JSTOR 606615.

- DeFrancis, John (1984), The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1068-9.

- Handel, Zev (2008), «What is Sino-Tibetan? Snapshot of a Field and a Language Family in Flux», Language and Linguistics Compass, 2 (3): 422–441, doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00061.x.

- Haugen, Einar (1966), «Dialect, Language, Nation», American Anthropologist, 68 (4): 922–935, doi:10.1525/aa.1966.68.4.02a00040, JSTOR 670407.

- Hudson, R. A. (1996), Sociolinguistics (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-56514-1.

- Hymes, Dell (1971), «Sociolinguistics and the ethnography of speaking», in Ardener, Edwin (ed.), Social Anthropology and Language, Routledge, pp. 47–92, ISBN 978-1-136-53941-1.

- Groves, Julie (2008), «Language or Dialect—or Topolect? A Comparison of the Attitudes of Hong Kongers and Mainland Chinese towards the Status of Cantonese» (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers (179)

- Kane, Daniel (2006), The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5.

- Kornicki, P.F. (2011), «A transnational approach to East Asian book history», in Chakravorty, Swapan; Gupta, Abhijit (eds.), New Word Order: Transnational Themes in Book History, Worldview Publications, pp. 65–79, ISBN 978-81-920651-1-3.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of «The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects», Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2015), Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Eighteenth ed.), Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Liang, Sihua (2014), Language Attitudes and Identities in Multilingual China: A Linguistic Ethnography, Springer International Publishing, ISBN 978-3-319-12619-7.

- Mair, Victor H. (1991), «What Is a Chinese «Dialect/Topolect»? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic terms» (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 29: 1–31, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2018, retrieved 12 January 2009.

- Matthews, Stephen; Yip, Virginia (1994), Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-08945-6.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1967), The Japanese Language, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-52717-8.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo (2004), Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 978-0-415-30575-4.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Norman, Jerry (2003), «The Chinese dialects: phonology», in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, Routledge, pp. 72–83, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Romaine, Suzanne (2000), Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-875133-5.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007), ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990), The Languages of Japan, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2001), The Korean Language, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36943-5.

- Sohn, Ho-Min; Lee, Peter H. (2003), «Language, forms, prosody, and themes», in Lee, Peter H. (ed.), A History of Korean Literature, Cambridge University Press, pp. 15–51, ISBN 978-0-521-82858-1.

- Thomason, Sarah Grey (1988), «Languages of the World», in Paulston, Christina Bratt (ed.), International Handbook of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education, Westport, CT: Greenwood, pp. 17–45, ISBN 978-0-313-24484-1.

- Van Herk, Gerard (2012), What is Sociolinguistics?, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-4051-9319-1.

- Wardaugh, Ronald; Fuller, Janet (2014), An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-118-73229-8.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese History: A Manual (2nd ed.), Harvard Univ Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Li, Rong; Baumann, Theo; Lee, Mei W. (1987), Language Atlas of China, Longman, ISBN 978-962-359-085-3.

- Zhang, Bennan; Yang, Robin R. (2004), «Putonghua education and language policy in postcolonial Hong Kong», in Zhou, Minglang (ed.), Language policy in the People’s Republic of China: Theory and practice since 1949, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 143–161, ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

- Sagart, Laurent; Jacques, Guillaume; Lai, Yunfan; Ryder, Robin; Thouzeau, Valentin; Greenhill, Simon J.; List, Johann-Mattis (2019), «Dated language phylogenies shed light on the history of Sino-Tibetan», Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116 (21): 10317–10322, doi:10.1073/pnas.1817972116, PMC 6534992, PMID 31061123.

- «Origin of Sino-Tibetan language family revealed by new research». ScienceDaily (Press release). 6 May 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Hannas, William C. (1997), Asia’s Orthographic Dilemma, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Qiu, Xigui (2000), Chinese Writing, trans. Gilbert Louis Mattos and Jerry Norman, Society for the Study of Early China and Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-55729-071-7.

- R. L. G. «Language borrowing Why so little Chinese in English?» The Economist. 6 June 2013.

- Huang, Cheng-Teh James; Li, Yen-Hui Audrey; Li, Yafei (2009), The Syntax of Chinese, Cambridge Syntax Guides, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139166935, ISBN 978-0-521-59958-0.

External links[edit]

Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Chinese.

- Classical Chinese texts – Chinese Text Project

- Marjorie Chan’s ChinaLinks Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Ohio State University with hundreds of links to Chinese related web pages

Unless otherwise specified, Chinese in this article is written in simplified/traditional/pinyin order. If the simplified and traditional characters are the same, they are written only once.

| Chinese | |

|---|---|

| 汉语/漢語, Hànyǔ or 中文, Zhōngwén | |

Hànyǔ written in traditional (top) and simplified characters (middle); Zhōngwén (bottom) |

|

| Native to | Sinophone world |

|

Native speakers |

1.35 billion (2022) |

|

Language family |

Sino-Tibetan

|

|

Early forms |

Old Chinese

|

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

Chinese characters (Traditional/Simplified) Transcriptions: |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

Mandarin:

Cantonese:[a]

|

| Regulated by | Ministry of Education (in the reserved name of «National Commission on Language and Script Work [zh]«) (Mainland China) National Languages Committee (Taiwan) Civil Service Bureau (Hong Kong) Education and Youth Affairs Bureau (Macau) Chinese Language Standardisation Council (Malaysia) Promote Mandarin Council (Singapore) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | zh |

| ISO 639-2 | chi (B) zho (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | zho – inclusive codeIndividual codes: cdo – Min Dongcjy – Jinyucmn – Mandarincpx – Pu-Xian Minczh – Huizhouczo – Central Mingan – Ganhak – Hakkahsn – Xiangmnp – Min Beinan – Min Nanwuu – Wuyue – Yuecsp – Southern Pinghuacnp – Northern Pinghuaoch – Old Chineseltc – Late Middle Chineselzh – Classical Chinese |

| Glottolog | sini1245 |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA |

Map of the Chinese-speaking world. Regions with a native Chinese-speaking majority. Regions where Chinese is not native but an official or educational language. Regions with significant Chinese-speaking minorities. |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

| Han language (general or spoken) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 汉语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han people/dynasty’s language | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese text (especially written) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 中文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Chinese («middle/central») text (or writing) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Han text (especially written and when distinguished from other languages of China) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han text (or writing) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chinese[c] (中文; Zhōngwén,[d] especially when referring to written Chinese) is a group of languages spoken natively by the ethnic Han Chinese majority and many minority ethnic groups in Greater China. About 1.3 billion people (or approximately 16% of the world’s population) speak a variety of Chinese as their first language.[1]

Chinese languages form the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages family. The spoken varieties of Chinese are usually considered by native speakers to be variants of a single language. However, their lack of mutual intelligibility means they are sometimes considered separate languages in a family.[e] Investigation of the historical relationships among the varieties of Chinese is ongoing. Currently, most classifications posit 7 to 13 main regional groups based on phonetic developments from Middle Chinese, of which the most spoken by far is Mandarin (with about 800 million speakers, or 66%), followed by Min (75 million, e.g. Southern Min), Wu (74 million, e.g. Shanghainese), and Yue (68 million, e.g. Cantonese). These branches are unintelligible to each other, and many of their subgroups are unintelligible with the other varieties within the same branch (e.g. Southern Min). There are, however, transitional areas where varieties from different branches share enough features for some limited intelligibility, including New Xiang with Southwest Mandarin, Xuanzhou Wu with Lower Yangtze Mandarin, Jin with Central Plains Mandarin and certain divergent dialects of Hakka with Gan (though these are unintelligible with mainstream Hakka). All varieties of Chinese are tonal to at least some degree, and are largely analytic.

The earliest Chinese written records are Shang dynasty-era oracle bone inscriptions, which can be dated to 1250 BCE. The phonetic categories of Old Chinese can be reconstructed from the rhymes of ancient poetry. During the Northern and Southern dynasties period, Middle Chinese went through several sound changes and split into several varieties following prolonged geographic and political separation. Qieyun, a rime dictionary, recorded a compromise between the pronunciations of different regions. The royal courts of the Ming and early Qing dynasties operated using a koiné language (Guanhua) based on Nanjing dialect of Lower Yangtze Mandarin.

Standard Chinese (Standard Mandarin), based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin, was adopted in the 1930s and is now an official language of both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan), one of the four official languages of Singapore, and one of the six official languages of the United Nations. The written form, using the logograms known as Chinese characters, is shared by literate speakers of mutually unintelligible dialects. Since the 1950s, simplified Chinese characters have been promoted for use by the government of the People’s Republic of China, while Singapore officially adopted simplified characters in 1976. Traditional characters remain in use in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and other countries with significant overseas Chinese speaking communities such as Malaysia (which although adopted simplified characters as the de facto standard in the 1980s, traditional characters still remain in widespread use).

Classification[edit]

After applying the linguistic comparative method to the database of comparative linguistic data developed by Laurent Sagart in 2019 to identify sound correspondences and establish cognates, phylogenetic methods are used to infer relationships among these languages and estimate the age of their origin and homeland.[4]

Linguists classify all varieties of Chinese as part of the Sino-Tibetan language family, together with Burmese, Tibetan and many other languages spoken in the Himalayas and the Southeast Asian Massif.[5] Although the relationship was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted, reconstruction of Sino-Tibetan is much less developed than that of families such as Indo-European or Austroasiatic. Difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflection in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to reach and are often also sensitive border zones.[6] Without a secure reconstruction of proto-Sino-Tibetan, the higher-level structure of the family remains unclear.[7] A top-level branching into Chinese and Tibeto-Burman languages is often assumed, but has not been convincingly demonstrated.[8]

History[edit]

The first written records appeared over 3,000 years ago during the Shang dynasty. As the language evolved over this period, the various local varieties became mutually unintelligible. In reaction, central governments have repeatedly sought to promulgate a unified standard.[9]

Old and Middle Chinese[edit]

The earliest examples of Chinese (Old Chinese) are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BCE in the late Shang dynasty.[10] The next attested stage came from inscriptions on bronze artifacts of the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BCE), the Classic of Poetry and portions of the Book of Documents and I Ching.[11] Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the phonology of Old Chinese by comparing later varieties of Chinese with the rhyming practice of the Classic of Poetry and the phonetic elements found in the majority of Chinese characters.[12] Although many of the finer details remain unclear, most scholars agree that Old Chinese differs from Middle Chinese in lacking retroflex and palatal obstruents but having initial consonant clusters of some sort, and in having voiceless nasals and liquids.[13] Most recent reconstructions also describe an atonal language with consonant clusters at the end of the syllable, developing into tone distinctions in Middle Chinese.[14] Several derivational affixes have also been identified, but the language lacks inflection, and indicated grammatical relationships using word order and grammatical particles.[15]

Middle Chinese was the language used during Northern and Southern dynasties and the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties (6th through 10th centuries CE). It can be divided into an early period, reflected by the Qieyun rime book (601 CE), and a late period in the 10th century, reflected by rhyme tables such as the Yunjing constructed by ancient Chinese philologists as a guide to the Qieyun system.[16] These works define phonological categories, but with little hint of what sounds they represent.[17] Linguists have identified these sounds by comparing the categories with pronunciations in modern varieties of Chinese, borrowed Chinese words in Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean, and transcription evidence.[18] The resulting system is very complex, with a large number of consonants and vowels, but they are probably not all distinguished in any single dialect. Most linguists now believe it represents a diasystem encompassing 6th-century northern and southern standards for reading the classics.[19]

Classical and literary forms[edit]

The relationship between spoken and written Chinese is rather complex («diglossia»). Its spoken varieties have evolved at different rates, while written Chinese itself has changed much less. Classical Chinese literature began in the Spring and Autumn period.

Rise of northern dialects[edit]

After the fall of the Northern Song dynasty and subsequent reign of the Jin (Jurchen) and Yuan (Mongol) dynasties in northern China, a common speech (now called Old Mandarin) developed based on the dialects of the North China Plain around the capital.[20]

The Zhongyuan Yinyun (1324) was a dictionary that codified the rhyming conventions of new sanqu verse form in this language.[21]

Together with the slightly later Menggu Ziyun, this dictionary describes a language with many of the features characteristic of modern Mandarin dialects.[22]

Up to the early 20th century, most Chinese people only spoke their local variety.[23]

Thus, as a practical measure, officials of the Ming and Qing dynasties carried out the administration of the empire using a common language based on Mandarin varieties, known as Guānhuà (官话/官話, literally «language of officials»).[24]

For most of this period, this language was a koiné based on dialects spoken in the Nanjing area, though not identical to any single dialect.[25]

By the middle of the 19th century, the Beijing dialect had become dominant and was essential for any business with the imperial court.[26]

In the 1930s, a standard national language, Guóyǔ (国语/國語 ; «national language») was adopted. After much dispute between proponents of northern and southern dialects and an abortive attempt at an artificial pronunciation, the National Language Unification Commission finally settled on the Beijing dialect in 1932. The People’s Republic founded in 1949 retained this standard but renamed it pǔtōnghuà (普通话/普通話; «common speech»).[27] The national language is now used in education, the media, and formal situations in both Mainland China and Taiwan.[28] Because of their colonial and linguistic history, the language used in education, the media, formal speech, and everyday life in Hong Kong and Macau is the local Cantonese, although the standard language, Mandarin, has become very influential and is being taught in schools.[29]

Influence[edit]

Historically, the Chinese language has spread to its neighbors through a variety of means. Northern Vietnam was incorporated into the Han empire in 111 BCE, marking the beginning of a period of Chinese control that ran almost continuously for a millennium. The Four Commanderies were established in northern Korea in the first century BCE, but disintegrated in the following centuries.[30] Chinese Buddhism spread over East Asia between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE, and with it the study of scriptures and literature in Literary Chinese.[31] Later Korea, Japan, and Vietnam developed strong central governments modeled on Chinese institutions, with Literary Chinese as the language of administration and scholarship, a position it would retain until the late 19th century in Korea and (to a lesser extent) Japan, and the early 20th century in Vietnam.[32] Scholars from different lands could communicate, albeit only in writing, using Literary Chinese.[33]