|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cobalt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | ( |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | hard lustrous bluish gray metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Co) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cobalt in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d7 4s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 15, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1768 K (1495 °C, 2723 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3200 K (2927 °C, 5301 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.90 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 8.86 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 16.06 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 377 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.81 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5[3] (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.88 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 125 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | Low spin: 126±3 pm High spin: 150±7 pm |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of cobalt |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4720 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.0 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 100 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 62.4 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ferromagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 209 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 75 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 180 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 5.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 1043 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 470–3000 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-48-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Georg Brandt (1735) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of cobalt

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth’s crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, produced by reductive smelting, is a hard, lustrous, silver-gray metal.

Cobalt-based blue pigments (cobalt blue) have been used since ancient times for jewelry and paints, and to impart a distinctive blue tint to glass, but the color was for a long time thought to be due to the known metal bismuth. Miners had long used the name kobold ore (German for goblin ore) for some of the blue-pigment-producing minerals; they were so named because they were poor in known metals, and gave poisonous arsenic-containing fumes when smelted.[4] In 1735, such ores were found to be reducible to a new metal (the first discovered since ancient times), and this was ultimately named for the kobold.

Today, some cobalt is produced specifically from one of a number of metallic-lustered ores, such as cobaltite (CoAsS). The element is, however, more usually produced as a by-product of copper and nickel mining. The Copperbelt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia yields most of the global cobalt production. World production in 2016 was 116,000 tonnes (114,000 long tons; 128,000 short tons) (according to Natural Resources Canada), and the DRC alone accounted for more than 50%.[5]

Cobalt is primarily used in lithium-ion batteries, and in the manufacture of magnetic, wear-resistant and high-strength alloys. The compounds cobalt silicate and cobalt(II) aluminate (CoAl2O4, cobalt blue) give a distinctive deep blue color to glass, ceramics, inks, paints and varnishes. Cobalt occurs naturally as only one stable isotope, cobalt-59. Cobalt-60 is a commercially important radioisotope, used as a radioactive tracer and for the production of high-energy gamma rays.

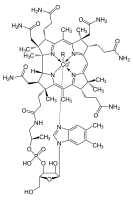

Cobalt is the active center of a group of coenzymes called cobalamins. Vitamin B12, the best-known example of the type, is an essential vitamin for all animals. Cobalt in inorganic form is also a micronutrient for bacteria, algae, and fungi.

Characteristics[edit]

A block of electrolytically refined cobalt (99.9% purity) cut from a large plate

Cobalt is a ferromagnetic metal with a specific gravity of 8.9. The Curie temperature is 1,115 °C (2,039 °F)[6] and the magnetic moment is 1.6–1.7 Bohr magnetons per atom.[7] Cobalt has a relative permeability two-thirds that of iron.[8] Metallic cobalt occurs as two crystallographic structures: hcp and fcc. The ideal transition temperature between the hcp and fcc structures is 450 °C (842 °F), but in practice the energy difference between them is so small that random intergrowth of the two is common.[9][10][11]

Cobalt is a weakly reducing metal that is protected from oxidation by a passivating oxide film. It is attacked by halogens and sulfur. Heating in oxygen produces Co3O4 which loses oxygen at 900 °C (1,650 °F) to give the monoxide CoO.[12] The metal reacts with fluorine (F2) at 520 K to give CoF3; with chlorine (Cl2), bromine (Br2) and iodine (I2), producing equivalent binary halides. It does not react with hydrogen gas (H2) or nitrogen gas (N2) even when heated, but it does react with boron, carbon, phosphorus, arsenic and sulfur.[13] At ordinary temperatures, it reacts slowly with mineral acids, and very slowly with moist, but not with dry, air.[citation needed]

Compounds[edit]

Common oxidation states of cobalt include +2 and +3, although compounds with oxidation states ranging from −3 to +5 are also known. A common oxidation state for simple compounds is +2 (cobalt(II)). These salts form the pink-colored metal aquo complex [Co(H

2O)

6]2+

in water. Addition of chloride gives the intensely blue [CoCl

4]2−

.[3] In a borax bead flame test, cobalt shows deep blue in both oxidizing and reducing flames.[14]

Oxygen and chalcogen compounds[edit]

Several oxides of cobalt are known. Green cobalt(II) oxide (CoO) has rocksalt structure. It is readily oxidized with water and oxygen to brown cobalt(III) hydroxide (Co(OH)3). At temperatures of 600–700 °C, CoO oxidizes to the blue cobalt(II,III) oxide (Co3O4), which has a spinel structure.[3] Black cobalt(III) oxide (Co2O3) is also known.[15] Cobalt oxides are antiferromagnetic at low temperature: CoO (Néel temperature 291 K) and Co3O4 (Néel temperature: 40 K), which is analogous to magnetite (Fe3O4), with a mixture of +2 and +3 oxidation states.[16]

The principal chalcogenides of cobalt include the black cobalt(II) sulfides, CoS2, which adopts a pyrite-like structure, and cobalt(III) sulfide (Co2S3).[citation needed]

Halides[edit]

Cobalt(II) chloride hexahydrate

Four dihalides of cobalt(II) are known: cobalt(II) fluoride (CoF2, pink), cobalt(II) chloride (CoCl2, blue), cobalt(II) bromide (CoBr2, green), cobalt(II) iodide (CoI2, blue-black). These halides exist in anhydrous and hydrated forms. Whereas the anhydrous dichloride is blue, the hydrate is red.[17]

The reduction potential for the reaction Co3+

+ e− → Co2+

is +1.92 V, beyond that for chlorine to chloride, +1.36 V. Consequently, cobalt(III) chloride would spontaneously reduce to cobalt(II) chloride and chlorine. Because the reduction potential for fluorine to fluoride is so high, +2.87 V, cobalt(III) fluoride is one of the few simple stable cobalt(III) compounds. Cobalt(III) fluoride, which is used in some fluorination reactions, reacts vigorously with water.[12]

Coordination compounds[edit]

As for all metals, molecular compounds and polyatomic ions of cobalt are classified as coordination complexes, that is, molecules or ions that contain cobalt linked to one or more ligands. These can be combinations of a potentially infinite variety of molecules and ions, such as:

- water H

2O, as in the cation hexaaquocobalt(II) [Co(H

2O)

6]2+

. This pink-colored complex is the predominant cation in solid cobalt sulfate CoSO

4·(H

2O)x, with x = 6 or 7, as well as in water solutions thereof. - ammonia NH

3, as in cis-diaquotetraamminecobalt(III) [Co(NH

3)

4(H

2O)

2]3+

, in hexol [Co(Co(NH

3)

4(HO)

2)

3]6−

, in [Co(NO

2)

4(NH

3)

2]−

(the anion of Erdmann’s salt),[18] and in [Co(NH

3)

5(CO

3)]−

.[18] - carbonate [CO

3]2−

, as in the green triscarbonatocobaltate(III) [Co(CO

3)

3]3−

anion.[19][18][20] - nitrite [NO

2]−

as in [Co(NO

2)

4(NH

3)

2]−

.[18] - hydroxide [HO]−

, as in hexol. - chloride [Cl]−

, as in tetrachloridocobaltate(II) CoCl

4]2−

. - bicarbonate [HCO

3]−

, as in [Co(CO

3)

2(HCO

3)(H

2O)]3−

.[18] - oxalate [C

2O

4]2−

, as in trisoxalatocobaltate(III) [Co(C

2O

4)3−

3].[18]

These attached groups affect the stability of oxidation states of the cobalt atoms, according to general principles of electronegativity and of the hardness–softness. For example, Co3+ complexes tend to have ammine ligands. Because phosphorus is softer than nitrogen, phosphine ligands tend to feature the softer Co2+ and Co+, an example being tris(triphenylphosphine)cobalt(I) chloride (P(C

6H

5)

3)

3CoCl). The more electronegative (and harder) oxide and fluoride can stabilize Co4+ and Co5+ derivatives, e.g. caesium hexafluorocobaltate(IV) (Cs2CoF6) and potassium percobaltate (K3CoO4).[12]

Alfred Werner, a Nobel-prize winning pioneer in coordination chemistry, worked with compounds of empirical formula [Co(NH

3)

6]3+

. One of the isomers determined was cobalt(III) hexammine chloride. This coordination complex, a typical Werner-type complex, consists of a central cobalt atom coordinated by six ammine orthogonal ligands and three chloride counteranions. Using chelating ethylenediamine ligands in place of ammonia gives tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) ([Co(en)

3]3+

), which was one of the first coordination complexes to be resolved into optical isomers. The complex exists in the right- and left-handed forms of a «three-bladed propeller». This complex was first isolated by Werner as yellow-gold needle-like crystals.[21][22]

Organometallic compounds[edit]

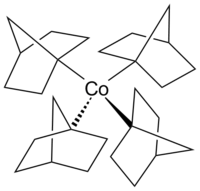

Structure of tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt(IV)

Cobaltocene is a structural analog to ferrocene, with cobalt in place of iron. Cobaltocene is much more sensitive to oxidation than ferrocene.[23] Cobalt carbonyl (Co2(CO)8) is a catalyst in carbonylation and hydrosilylation reactions.[24] Vitamin B12 (see below) is an organometallic compound found in nature and is the only vitamin that contains a metal atom.[25] An example of an alkylcobalt complex in the otherwise uncommon +4 oxidation state of cobalt is the homoleptic complex tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt(IV) (Co(1-norb)4), a transition metal-alkyl complex that is notable for its resistance to β-hydrogen elimination,[26] in accord with Bredt’s rule. The cobalt(III) and cobalt(V) complexes [Li(THF)

4]+

[Co(1-norb)

4]−

and [Co(1-norb)

4]+

[BF

4]−

are also known.[27]

Isotopes[edit]

59Co is the only stable cobalt isotope and the only isotope that exists naturally on Earth. Twenty-two radioisotopes have been characterized: the most stable, 60Co, has a half-life of 5.2714 years; 57Co has a half-life of 271.8 days; 56Co has a half-life of 77.27 days; and 58Co has a half-life of 70.86 days. All the other radioactive isotopes of cobalt have half-lives shorter than 18 hours, and in most cases shorter than 1 second. This element also has 4 meta states, all of which have half-lives shorter than 15 minutes.[28]

The isotopes of cobalt range in atomic weight from 50 u (50Co) to 73 u (73Co). The primary decay mode for isotopes with atomic mass unit values less than that of the only stable isotope, 59Co, is electron capture and the primary mode of decay in isotopes with atomic mass greater than 59 atomic mass units is beta decay. The primary decay products below 59Co are element 26 (iron) isotopes; above that the decay products are element 28 (nickel) isotopes.[28]

History[edit]

Early Chinese blue and white porcelain, manufactured c. 1335

Cobalt compounds have been used for centuries to impart a rich blue color to glass, glazes, and ceramics. Cobalt has been detected in Egyptian sculpture, Persian jewelry from the third millennium BC, in the ruins of Pompeii, destroyed in 79 AD, and in China, dating from the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) and the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD).[29]

Cobalt has been used to color glass since the Bronze Age. The excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck yielded an ingot of blue glass, cast during the 14th century BC.[30][31] Blue glass from Egypt was either colored with copper, iron, or cobalt. The oldest cobalt-colored glass is from the eighteenth dynasty of Egypt (1550–1292 BC). The source for the cobalt the Egyptians used is not known.[32][33]

The word cobalt is derived from the German kobalt, from kobold meaning «goblin», a superstitious term used for the ore of cobalt by miners. The first attempts to smelt those ores for copper or silver failed, yielding simply powder (cobalt(II) oxide) instead. Because the primary ores of cobalt always contain arsenic, smelting the ore oxidized the arsenic into the highly toxic and volatile arsenic oxide, adding to the notoriety of the ore.[34]

Swedish chemist Georg Brandt (1694–1768) is credited with discovering cobalt circa 1735, showing it to be a previously unknown element, distinct from bismuth and other traditional metals. Brandt called it a new «semi-metal».[35][36] He showed that compounds of cobalt metal were the source of the blue color in glass, which previously had been attributed to the bismuth found with cobalt. Cobalt became the first metal to be discovered since the pre-historical period. All other known metals (iron, copper, silver, gold, zinc, mercury, tin, lead and bismuth) had no recorded discoverers.[37]

During the 19th century, a significant part of the world’s production of cobalt blue (a pigment made with cobalt compounds and alumina) and smalt (cobalt glass powdered for use for pigment purposes in ceramics and painting) was carried out at the Norwegian Blaafarveværket.[38][39] The first mines for the production of smalt in the 16th century were located in Norway, Sweden, Saxony and Hungary. With the discovery of cobalt ore in New Caledonia in 1864, the mining of cobalt in Europe declined. With the discovery of ore deposits in Ontario, Canada in 1904 and the discovery of even larger deposits in the Katanga Province in the Congo in 1914, the mining operations shifted again.[34] When the Shaba conflict started in 1978, the copper mines of Katanga Province nearly stopped production.[40][41] The impact on the world cobalt economy from this conflict was smaller than expected: cobalt is a rare metal, the pigment is highly toxic, and the industry had already established effective ways for recycling cobalt materials. In some cases, industry was able to change to cobalt-free alternatives.[40][41]

In 1938, John Livingood and Glenn T. Seaborg discovered the radioisotope cobalt-60.[42] This isotope was famously used at Columbia University in the 1950s to establish parity violation in radioactive beta decay.[43][44]

After World War II, the US wanted to guarantee the supply of cobalt ore for military uses (as the Germans had been doing) and prospected for cobalt within the U.S. border. An adequate supply of the ore was found in Idaho near Blackbird canyon in the side of a mountain. The firm Calera Mining Company started production at the site.[45]

It has been argued that cobalt will be one of the main objects of geopolitical competition in a world running on renewable energy and dependent on batteries, but this perspective has also been criticised for underestimating the power of economic incentives for expanded production.[46]

Occurrence[edit]

The stable form of cobalt is produced in supernovae through the r-process.[47] It comprises 0.0029% of the Earth’s crust. Free cobalt (the native metal) is not found on Earth because of the oxygen in the atmosphere and the chlorine in the ocean. Both are abundant enough in the upper layers of the Earth’s crust to prevent native metal cobalt from forming. Except as recently delivered in meteoric iron, pure cobalt in native metal form is unknown on Earth. The element has a medium abundance but natural compounds of cobalt are numerous and small amounts of cobalt compounds are found in most rocks, soils, plants, and animals.[citation needed]

In nature, cobalt is frequently associated with nickel. Both are characteristic components of meteoric iron, though cobalt is much less abundant in iron meteorites than nickel. As with nickel, cobalt in meteoric iron alloys may have been well enough protected from oxygen and moisture to remain as the free (but alloyed) metal,[48] though neither element is seen in that form in the ancient terrestrial crust.[citation needed]

Cobalt in compound form occurs in copper and nickel minerals. It is the major metallic component that combines with sulfur and arsenic in the sulfidic cobaltite (CoAsS), safflorite (CoAs2), glaucodot ((Co,Fe)AsS), and skutterudite (CoAs3) minerals.[12] The mineral cattierite is similar to pyrite and occurs together with vaesite in the copper deposits of Katanga Province.[49] When it reaches the atmosphere, weathering occurs; the sulfide minerals oxidize and form pink erythrite («cobalt glance»: Co3(AsO4)2·8H2O) and spherocobaltite (CoCO3).[50][51]

Cobalt is also a constituent of tobacco smoke.[52] The tobacco plant readily absorbs and accumulates heavy metals like cobalt from the surrounding soil in its leaves. These are subsequently inhaled during tobacco smoking.[53]

In the ocean[edit]

Cobalt is a trace metal involved in photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation detected in most ocean basins and is a limiting micronutrient for phytoplankton and cyanobacteria.[54][55] The Co-containing complex cobalamin is only synthesized by cyanobacteria and a few archaea, so dissolved cobalt concentrations are low in the upper ocean. Like Mn and Fe, Co has a hybrid profile of biological uptake by phytoplankton via photosynthesis in the upper ocean and scavenging in the deep ocean, although most scavenging is limited by complex organic ligands.[56][57] Co is recycled in the ocean by decaying organic matter that sinks below the upper ocean, although most is scavenged by oxidizing bacteria.[citation needed]

Sources of cobalt for many ocean bodies include rivers and terrestrial runoff with some input from hydrothermal vents.[58] In the deep ocean, cobalt sources are found lying on top of seamounts (which can be large or small) where ocean currents sweep the ocean floor to clear sediment over the span of millions of years allowing them to form as ferromanganese crusts.[59] Although limited mapping of the seafloor has been done, preliminary investigation indicates that there is a large amount of these cobalt-rich crusts located in the Clarion Clipperton Zone,[60] an area garnering increasing interest for deep sea mining ventures due to the mineral-rich environment within its domain. Anthropogenic input contributes as a non-natural source but in very low amounts. Dissolved cobalt (dCo) concentrations across oceans are controlled primarily by reservoirs where dissolved oxygen concentrations are low. The complex biochemical cycling of cobalt in the ocean is still not fully understood, but patterns of higher concentrations have been found in areas of low oxygen[61] such as the Oxygen Minimum Zone (OMZ) in the Southern Atlantic Ocean.[62]

Cobalt is considered toxic for marine environments at high concentrations.[63] Safe concentrations fall around 18 μg/L in marine waters for plankton such as diatoms.[citation needed]

Production[edit]

| Country | Production | Reserves |

|---|---|---|

| 64,000 | 3,500,000 | |

| 5,600 | 250,000 | |

| 5,000 | 1,200,000 | |

| 4,300 | 250,000 | |

| 4,200 | 500,000 | |

| 4,000 | 280,000 | |

| 3,800 | 150,000 | |

| 3,200 | 51,000 | |

| 2,900 | 270,000 | |

| 2,800 | — | |

| 2,500 | 29,000 | |

| 1,500 | ||

| 650 | 23,000 | |

| Other countries | 5,900 | 560,000 |

| World total | 110,000 | 7,100,000 |

The main ores of cobalt are cobaltite, erythrite, glaucodot and skutterudite (see above), but most cobalt is obtained by reducing the cobalt by-products of nickel and copper mining and smelting.[65][66]

Since cobalt is generally produced as a by-product, the supply of cobalt depends to a great extent on the economic feasibility of copper and nickel mining in a given market. Demand for cobalt was projected to grow 6% in 2017.[67]

Primary cobalt deposits are rare, such as those occurring in hydrothermal deposits, associated with ultramafic rocks, typified by the Bou-Azzer district of Morocco. At such locations, cobalt ores are mined exclusively, albeit at a lower concentration, and thus require more downstream processing for cobalt extraction.[68][69]

Several methods exist to separate cobalt from copper and nickel, depending on the concentration of cobalt and the exact composition of the used ore. One method is froth flotation, in which surfactants bind to ore components, leading to an enrichment of cobalt ores. Subsequent roasting converts the ores to cobalt sulfate, and the copper and the iron are oxidized to the oxide. Leaching with water extracts the sulfate together with the arsenates. The residues are further leached with sulfuric acid, yielding a solution of copper sulfate. Cobalt can also be leached from the slag of copper smelting.[70]

The products of the above-mentioned processes are transformed into the cobalt oxide (Co3O4). This oxide is reduced to metal by the aluminothermic reaction or reduction with carbon in a blast furnace.[12]

[edit]

The United States Geological Survey estimates world reserves of cobalt at 7,100,000 metric tons.[71] The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) currently produces 63% of the world’s cobalt. This market share may reach 73% by 2025 if planned expansions by mining producers like Glencore Plc take place as expected. But by 2030, global demand could be 47 times more than it was in 2017, Bloomberg New Energy Finance has estimated.[72]

Changes that Congo made to mining laws in 2002 attracted new investments in Congolese copper and cobalt projects. Glencore’s Mutanda Mine shipped 24,500 tons of cobalt in 2016, 40% of Congo DRC’s output and nearly a quarter of global production. After oversupply, Glencore closed Mutanda for two years in late 2019.[73][74] Glencore’s Katanga Mining project is resuming as well and should produce 300,000 tons of copper and 20,000 tons of cobalt by 2019, according to Glencore.[67]

After hitting near-decade highs in early 2018 above US$100,000 per tonne, prices for cobalt used in the global electric battery supply chain slipped by 45% in the following 2 years. With the upsurge in Electric (EV) vehicle demand in 2020 and early 2021, cobalt prices rose to US$54,000 per tonne by March 2021.[citation needed]

Cobalt is ranked as a critical mineral by the United States, Japan, Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom and the European Union.[citation needed]

Democratic Republic of the Congo[edit]

In 2005, the top producer of cobalt was the copper deposits in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Katanga Province. Formerly Shaba province, the area had almost 40% of global reserves, reported the British Geological Survey in 2009.[75]

Artisanal mining supplied 17% to 40% of the DRC production.[76] Some 100,000 cobalt miners in Congo DRC use hand tools to dig hundreds of feet, with little planning and fewer safety measures, say workers and government and NGO officials, as well as The Washington Post reporters’ observations on visits to isolated mines. The lack of safety precautions frequently causes injuries or death.[77] Mining pollutes the vicinity and exposes local wildlife and indigenous communities to toxic metals thought to cause birth defects and breathing difficulties, according to health officials.[78]

Human rights activists have alleged, and investigative journalism reported confirmation,[79][80] that child labor is used in mining cobalt from African artisanal mines.[76][81] This revelation prompted cell phone maker Apple Inc., on March 3, 2017, to stop buying ore from suppliers such as Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt who source from artisanal mines in the DRC, and begin using only suppliers that are verified to meet its workplace standards.[82][83]

There is a push globally by the EU and major car manufacturers (OEM) for global production of cobalt to be sourced and produced sustainably, responsibly and traceability of the supply chain. Mining companies are adopting and practising ESG initiatives in line with OECD Guidance and putting in place evidence of zero to low carbon footprint activities in the supply chain production of Lithium-ion batteries. These initiatives are already taking place with major mining companies, Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining companies (ASM). Car manufacturers and battery manufacturer supply chains Tesla, VW, BMW, BASF, Glencore are participating in several initiatives, such as the Responsible Cobalt Initiative and Cobalt for Development study. In 2018 BMW Group in partnership with BASF, Samsung SDI and Samsung Electronics have launched a pilot project in the DRC over one pilot mine, to improve conditions and address challenges for artisanal miners and the surrounding communities.

The political and ethnic dynamics of the region have in the past caused outbreaks of violence and years of armed conflict and displaced populations. This instability affected the price of cobalt and also created perverse incentives for the combatants in the First and Second Congo Wars to prolong the fighting, since access to diamond mines and other valuable resources helped to finance their military goals—which frequently amounted to genocide—and also enriched the fighters themselves. While DR Congo has in the 2010s not recently been invaded by neighboring military forces, some of the richest mineral deposits adjoin areas where Tutsis and Hutus still frequently clash, unrest continues although on a smaller scale and refugees still flee outbreaks of violence.[84]

Cobalt extracted from small Congolese artisanal mining endeavors in 2007 supplied a single Chinese company, Congo DongFang International Mining. A subsidiary of Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, one of the world’s largest cobalt producers, Congo DongFang supplied cobalt to some of the world’s largest battery manufacturers, who produced batteries for ubiquitous products like the Apple iPhones. Because of accused labour violations and environmental concerns, LG Chem subsequently audited Congo DongFang in accordance with OECD guidelines. LG Chem, which also produces battery materials for car companies, imposed a code of conduct on all suppliers that it inspects.[85]

The Mukondo Mountain project, operated by the Central African Mining and Exploration Company (CAMEC) in Katanga Province, may be the richest cobalt reserve in the world. It produced an estimated one-third of the total global cobalt production in 2008.[86] In July 2009, CAMEC announced a long-term agreement to deliver its entire annual production of cobalt concentrate from Mukondo Mountain to Zhejiang Galico Cobalt & Nickel Materials of China.[87]

In February 2018, global asset management firm AllianceBernstein defined the DRC as economically «the Saudi Arabia of the electric vehicle age», due to its cobalt resources, as essential to the lithium-ion batteries that drive electric vehicles.[88]

On March 9, 2018, President Joseph Kabila updated the 2002 mining code, increasing royalty charges and declaring cobalt and coltan «strategic metals».[89][90]

The 2002 mining code was effectively updated on December 4, 2018.[91]

In December 2019, International Rights Advocates, a human rights NGO, filed a landmark lawsuit against Apple, Tesla, Dell, Microsoft and Google company Alphabet for «knowingly benefiting from and aiding and abetting the cruel and brutal use of young children» in mining cobalt.[92] The companies in question denied their involvement in child labour.[93]

Canada[edit]

In 2017, some exploration companies were planning to survey old silver and cobalt mines in the area of Cobalt, Ontario where significant deposits are believed to lie.[94]

Cuba[edit]

Canada’s Sherritt International processes cobalt ores in nickel deposits from the Moa mines in Cuba, and the island has several others mines in Mayari, Camaguey, and Pinar del Rio. Continued investments by Sherritt International in Cuban nickel and cobalt production while acquiring mining rights for 17–20 years made the communist country third for cobalt reserves in 2019, before Canada itself.[95]

Applications[edit]

In 2016, 116,000 tonnes (128,000 short tons) of cobalt was used.[5]

Cobalt has been used in the production of high-performance alloys.[65][66] It is also used in some rechargeable batteries.

Alloys[edit]

Cobalt-based superalloys have historically consumed most of the cobalt produced.[65][66] The temperature stability of these alloys makes them suitable for turbine blades for gas turbines and aircraft jet engines, although nickel-based single-crystal alloys surpass them in performance.[96] Cobalt-based alloys are also corrosion- and wear-resistant, making them, like titanium, useful for making orthopedic implants that don’t wear down over time. The development of wear-resistant cobalt alloys started in the first decade of the 20th century with the stellite alloys, containing chromium with varying quantities of tungsten and carbon. Alloys with chromium and tungsten carbides are very hard and wear-resistant.[97] Special cobalt-chromium-molybdenum alloys like Vitallium are used for prosthetic parts (hip and knee replacements).[98] Cobalt alloys are also used for dental prosthetics as a useful substitute for nickel, which may be allergenic.[99] Some high-speed steels also contain cobalt for increased heat and wear resistance. The special alloys of aluminium, nickel, cobalt and iron, known as Alnico, and of samarium and cobalt (samarium-cobalt magnet) are used in permanent magnets.[100] It is also alloyed with 95% platinum for jewelry, yielding an alloy suitable for fine casting, which is also slightly magnetic.[101]

Batteries[edit]

Lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2) is widely used in lithium-ion battery cathodes. The material is composed of cobalt oxide layers with the lithium intercalated. During discharge (i.e. when not actively being charged), the lithium is released as lithium ions.[102] Nickel-cadmium[103] (NiCd) and nickel metal hydride[104] (NiMH) batteries also include cobalt to improve the oxidation of nickel in the battery.[103]

Transparency Market Research estimated the global lithium-ion battery market at $30 billion in 2015 and predicted an increase to over US$75 billion by 2024.[105]

Although in 2018 most cobalt in batteries was used in a mobile device,[106] a more recent application for cobalt is rechargeable batteries for electric cars. This industry has increased five-fold in its demand for cobalt, which makes it urgent to find new raw materials in more stable areas of the world.[107] Demand is expected to continue or increase as the prevalence of electric vehicles increases.[108] Exploration in 2016–2017 included the area around Cobalt, Ontario, an area where many silver mines ceased operation decades ago.[107] Cobalt for electric vehicles increased 81% from the first half of 2018 to 7,200 tonnes in the first half of 2019, for a battery capacity of 46.3 GWh.[109][110] The future of electric cars may depend on deep-sea mining, since cobalt is abundant in rocks on the seabed.[111]

Since child and slave labor have been repeatedly reported in cobalt mining, primarily in the artisanal mines of DR Congo, technology companies seeking an ethical supply chain have faced shortages of this raw material and[112] the price of cobalt metal reached a nine-year high in October 2017, more than US$30 a pound, versus US$10 in late 2015.[113] After oversupply, the price dropped to a more normal $15 in 2019.[114][115] As a reaction to the issues with artisanal cobalt mining in DR Congo a number of cobalt suppliers and their customers have formed the Fair Cobalt Alliance (FCA) which aims to end the use of child labor and to improve the working conditions of cobalt mining and processing in the DR Congo. Members of FCA include Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Sono Motors, the Responsible Cobalt Initiative, Fairphone, Glencore and Tesla, Inc.[116][117]

Research is being conducted by the European Union on the possibility to eliminate cobalt requirements in lithium-ion battery production.[118][119] As of August 2020 battery makers have gradually reduced the cathode cobalt content from 1/3 (NMC 111) to 2/10 (NMC 442) to currently 1/10 (NMC 811) and have also introduced the cobalt free LFP cathode into the battery packs of electric cars such as the Tesla Model 3.[120][121] In September 2020, Tesla outlined their plans to make their own, cobalt-free battery cells.[122]

Catalysts[edit]

Several cobalt compounds are oxidation catalysts. Cobalt acetate is used to convert xylene to terephthalic acid, the precursor of the bulk polymer polyethylene terephthalate. Typical catalysts are the cobalt carboxylates (known as cobalt soaps). They are also used in paints, varnishes, and inks as «drying agents» through the oxidation of drying oils.[123][102] The same carboxylates are used to improve the adhesion between steel and rubber in steel-belted radial tires. In addition they are used as accelerators in polyester resin systems.[124][125][126]

Cobalt-based catalysts are used in reactions involving carbon monoxide. Cobalt is also a catalyst in the Fischer–Tropsch process for the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide into liquid fuels.[127] Hydroformylation of alkenes often uses cobalt octacarbonyl as a catalyst,[128]

The hydrodesulfurization of petroleum uses a catalyst derived from cobalt and molybdenum. This process helps to clean petroleum of sulfur impurities that interfere with the refining of liquid fuels.[102]

Pigments and coloring[edit]

Before the 19th century, cobalt was predominantly used as a pigment. It has been used since the Middle Ages to make smalt, a blue-colored glass. Smalt is produced by melting a mixture of roasted mineral smaltite, quartz and potassium carbonate, which yields a dark blue silicate glass, which is finely ground after the production.[129] Smalt was widely used to color glass and as pigment for paintings.[130] In 1780, Sven Rinman discovered cobalt green, and in 1802 Louis Jacques Thénard discovered cobalt blue.[131] Cobalt pigments such as cobalt blue (cobalt aluminate), cerulean blue (cobalt(II) stannate), various hues of cobalt green (a mixture of cobalt(II) oxide and zinc oxide), and cobalt violet (cobalt phosphate) are used as artist’s pigments because of their superior chromatic stability.[132][133]

Radioisotopes[edit]

Cobalt-60 (Co-60 or 60Co) is useful as a gamma-ray source because it can be produced in predictable amounts with high activity by bombarding cobalt with neutrons. It produces gamma rays with energies of 1.17 and 1.33 MeV.[28][134]

Cobalt is used in external beam radiotherapy, sterilization of medical supplies and medical waste, radiation treatment of foods for sterilization (cold pasteurization),[135] industrial radiography (e.g. weld integrity radiographs), density measurements (e.g. concrete density measurements), and tank fill height switches. The metal has the unfortunate property of producing a fine dust, causing problems with radiation protection. Cobalt from radiotherapy machines has been a serious hazard when not discarded properly, and one of the worst radiation contamination accidents in North America occurred in 1984, when a discarded radiotherapy unit containing cobalt-60 was mistakenly disassembled in a junkyard in Juarez, Mexico.[136][137]

Cobalt-60 has a radioactive half-life of 5.27 years. Loss of potency requires periodic replacement of the source in radiotherapy and is one reason why cobalt machines have been largely replaced by linear accelerators in modern radiation therapy.[138] Cobalt-57 (Co-57 or 57Co) is a cobalt radioisotope most often used in medical tests, as a radiolabel for vitamin B12 uptake, and for the Schilling test. Cobalt-57 is used as a source in Mössbauer spectroscopy and is one of several possible sources in X-ray fluorescence devices.[139][140]

Nuclear weapon designs could intentionally incorporate 59Co, some of which would be activated in a nuclear explosion to produce 60Co. The 60Co, dispersed as nuclear fallout, is sometimes called a cobalt bomb.[141]

[142]

Other uses[edit]

- Cobalt is used in electroplating for its attractive appearance, hardness, and resistance to oxidation.[143]

- It is also used as a base primer coat for porcelain enamels.[144]

Biological role[edit]

Cobalt is essential to the metabolism of all animals. It is a key constituent of cobalamin, also known as vitamin B12, the primary biological reservoir of cobalt as an ultratrace element.[145][146] Bacteria in the stomachs of ruminant animals convert cobalt salts into vitamin B12, a compound which can only be produced by bacteria or archaea. A minimal presence of cobalt in soils therefore markedly improves the health of grazing animals, and an uptake of 0.20 mg/kg a day is recommended because they have no other source of vitamin B12.[147]

Proteins based on cobalamin use corrin to hold the cobalt. Coenzyme B12 features a reactive C-Co bond that participates in the reactions.[148] In humans, B12 has two types of alkyl ligand: methyl and adenosyl. MeB12 promotes methyl (−CH3) group transfers. The adenosyl version of B12 catalyzes rearrangements in which a hydrogen atom is directly transferred between two adjacent atoms with concomitant exchange of the second substituent, X, which may be a carbon atom with substituents, an oxygen atom of an alcohol, or an amine. Methylmalonyl coenzyme A mutase (MUT) converts MMl-CoA to Su-CoA, an important step in the extraction of energy from proteins and fats.[149]

Although far less common than other metalloproteins (e.g. those of zinc and iron), other cobaltoproteins are known besides B12. These proteins include methionine aminopeptidase 2, an enzyme that occurs in humans and other mammals that does not use the corrin ring of B12, but binds cobalt directly. Another non-corrin cobalt enzyme is nitrile hydratase, an enzyme in bacteria that metabolizes nitriles.[150]

Cobalt deficiency[edit]

In humans, consumption of cobalt-containing vitamin B12 meets all needs for cobalt. For cattle and sheep, which meet vitamin B12 needs via synthesis by resident bacteria in the rumen, there is a function for inorganic cobalt. In the early 20th century, during the development of farming on the North Island Volcanic Plateau of New Zealand, cattle suffered from what was termed «bush sickness». It was discovered that the volcanic soils lacked the cobalt salts essential for the cattle food chain.[151][152] The «coast disease» of sheep in the Ninety Mile Desert of the Southeast of South Australia in the 1930s was found to originate in nutritional deficiencies of trace elements cobalt and copper. The cobalt deficiency was overcome by the development of «cobalt bullets», dense pellets of cobalt oxide mixed with clay given orally for lodging in the animal’s rumen.[clarification needed][153][152][154]

-

-

Cobalt-deficient sheep

Health issues[edit]

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling:[155] | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H302, H317, H319, H334, H341, H350, H360F, H412 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P273, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2 0 0 |

The LD50 value for soluble cobalt salts has been estimated to be between 150 and 500 mg/kg.[156] In the US, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has designated a permissible exposure limit (PEL) in the workplace as a time-weighted average (TWA) of 0.1 mg/m3. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.05 mg/m3, time-weighted average. The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value is 20 mg/m3.[157]

However, chronic cobalt ingestion has caused serious health problems at doses far less than the lethal dose. In 1966, the addition of cobalt compounds to stabilize beer foam in Canada led to a peculiar form of toxin-induced cardiomyopathy, which came to be known as beer drinker’s cardiomyopathy.[158][159]

Furthermore, cobalt metal is suspected of causing cancer (i.e., possibly carcinogenic, IARC Group 2B) as per the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs.[160]

It causes respiratory problems when inhaled.[161] It also causes skin problems when touched; after nickel and chromium, cobalt is a major cause of contact dermatitis.[162]

References[edit]

- ^ «cobalt». Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Cobalt». CIAAW. 2017.

- ^ a b c Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 1117–1119. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ «cobalt». Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ^ a b Danielle Bochove (November 1, 2017). «Electric car future spurs Cobalt rush: Swelling demand for product breathes new life into small Ontario town». Vancouver Sun. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2019-07-28.

- ^ Enghag, Per (2004). «Cobalt». Encyclopedia of the elements: technical data, history, processing, applications. p. 667. ISBN 978-3-527-30666-4.

- ^ Murthy, V. S. R (2003). «Magnetic Properties of Materials». Structure And Properties Of Engineering Materials. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-07-048287-6.

- ^ Celozzi, Salvatore; Araneo, Rodolfo; Lovat, Giampiero (2008-05-01). Electromagnetic Shielding. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-470-05536-6.

- ^ Lee, B.; Alsenz, R.; Ignatiev, A.; Van Hove, M.; Van Hove, M. A. (1978). «Surface structures of the two allotropic phases of cobalt». Physical Review B. 17 (4): 1510–1520. Bibcode:1978PhRvB..17.1510L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.17.1510.

- ^ «Properties and Facts for Cobalt». American Elements. Archived from the original on 2008-10-02. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Cobalt, Centre d’Information du Cobalt, Brussels (1966). Cobalt. p. 45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. (2007). «Cobalt». Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (102nd ed.). de Gruyter. pp. 1146–1152. ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1.

- ^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 722. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ Rutley, Frank (2012-12-06). Rutley’s Elements of Mineralogy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 40. ISBN 978-94-011-9769-4.

- ^ Krebs, Robert E. (2006). The history and use of our earth’s chemical elements: a reference guide (2nd ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 107. ISBN 0-313-33438-2.

- ^ Petitto, Sarah C.; Marsh, Erin M.; Carson, Gregory A.; Langell, Marjorie A. (2008). «Cobalt oxide surface chemistry: The interaction of CoO(100), Co3O4(110) and Co3O4(111) with oxygen and water». Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. 281 (1–2): 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2007.08.023. S2CID 28393408.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 1119–1120. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas P. McCutcheon and William J. Schuele (1953): «Complex Acids of Cobalt and Chromium. The Green Carbonatocobalt(III) Anion». Journal of the American Chemical Society, volume 75, issue 8, pages 1845–1846. doi:10.1021/ja01104a019

- ^ H. F. Bauer and W. C. Drinkard (1960): «A General Synthesis of Cobalt(III) Complexes; A New Intermediate, Na3[Co(CO3)3]·3H2O». Journal of the American Chemical Society, volume 82, issue 19, pages 5031–5032. doi:10.1021/ja01504a004.

- ^ Fikru Tafesse, Elias Aphane, and Elizabeth Mongadi (2009): «Determination of the structural formula of sodium tris-carbonatocobaltate(III), Na3[Co(CO3)3]·3H2O by thermogravimetry». Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, volume 102, issue 1, pages 91–97. doi:10.1007/s10973-009-0606-2

- ^ Werner, A. (1912). «Zur Kenntnis des asymmetrischen Kobaltatoms. V». Chemische Berichte. 45: 121–130. doi:10.1002/cber.19120450116.

- ^ Gispert, Joan Ribas (2008). «Early Theories of Coordination Chemistry». Coordination chemistry. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-3-527-31802-5. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ^

James E. House (2008). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 767–. ISBN 978-0-12-356786-4. Retrieved 2011-05-16. - ^ Charles M. Starks; Charles Leonard Liotta; Marc Halpern (1994). Phase-transfer catalysis: fundamentals, applications, and industrial perspectives. Springer. pp. 600–. ISBN 978-0-412-04071-9. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ Sigel, Astrid; Sigel, Helmut; Sigel, Roland, eds. (2010). Organometallics in Environment and Toxicology (Metal Ions in Life Sciences). Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-84755-177-1.

- ^

Byrne, Erin K.; Richeson, Darrin S.; Theopold, Klaus H. (1986-01-01). «Tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt, a low spin tetrahedral complex of a first row transition metal». Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (19): 1491. doi:10.1039/C39860001491. ISSN 0022-4936. - ^

Byrne, Erin K.; Theopold, Klaus H. (1987-02-01). «Redox chemistry of tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt. Synthesis and characterization of a cobalt(V) alkyl and self-exchange rate of a Co(III)/Co(IV) couple». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 109 (4): 1282–1283. doi:10.1021/ja00238a066. ISSN 0002-7863. - ^ a b c Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ Cobalt, Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^

Pulak, Cemal (1998). «The Uluburun shipwreck: an overview». International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 27 (3): 188–224. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1998.tb00803.x. - ^

Henderson, Julian (2000). «Glass». The Science and Archaeology of Materials: An Investigation of Inorganic Materials. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-415-19933-9. - ^

Rehren, Th. (2003). «Aspects of the Production of Cobalt-blue Glass in Egypt». Archaeometry. 43 (4): 483–489. doi:10.1111/1475-4754.00031. - ^ Lucas, A. (2003). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. Kessinger Publishing. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7661-5141-3.

- ^ a b Dennis, W. H (2010). «Cobalt». Metallurgy: 1863–1963. pp. 254–256. ISBN 978-0-202-36361-5.

- ^ Georg Brandt first showed cobalt to be a new metal in: G. Brandt (1735) «Dissertatio de semimetallis» (Dissertation on semi-metals), Acta Literaria et Scientiarum Sveciae (Journal of Swedish literature and sciences), vol. 4, pages 1–10.

See also: (1) G. Brandt (1746) «Rön och anmärkningar angäende en synnerlig färg—cobolt» (Observations and remarks concerning an extraordinary pigment—cobalt), Kongliga Svenska vetenskapsakademiens handlingar (Transactions of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science), vol. 7, pp. 119–130; (2) G. Brandt (1748) «Cobalti nova species examinata et descripta» (Cobalt, a new element examined and described), Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis (Journal of the Royal Scientific Society of Uppsala), 1st series, vol. 3, pp. 33–41; (3) James L. Marshall and Virginia R. Marshall (Spring 2003) «Rediscovery of the Elements: Riddarhyttan, Sweden». The Hexagon (official journal of the Alpha Chi Sigma fraternity of chemists), vol. 94, no. 1, pages 3–8. - ^

Wang, Shijie (2006). «Cobalt—Its recovery, recycling, and application». Journal of the Minerals, Metals and Materials Society. 58 (10): 47–50. Bibcode:2006JOM….58j..47W. doi:10.1007/s11837-006-0201-y. S2CID 137613322. - ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). «The discovery of the elements. III. Some eighteenth-century metals». Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (1): 22. Bibcode:1932JChEd…9…22W. doi:10.1021/ed009p22.

- ^ Ramberg, Ivar B. (2008). The making of a land: geology of Norway. Geological Society. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-82-92394-42-7. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ Cyclopaedia (1852). C. Tomlinson. 9 divs (ed.). Cyclopædia of useful arts & manufactures. pp. 400–. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ a b Wellmer, Friedrich-Wilhelm; Becker-Platen, Jens Dieter. «Global Nonfuel Mineral Resources and Sustainability». United States Geological Survey.

- ^ a b Westing, Arthur H; Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (1986). «cobalt». Global resources and international conflict: environmental factors in strategic policy and action. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-0-19-829104-6.

- ^ Livingood, J.; Seaborg, Glenn T. (1938). «Long-Lived Radio Cobalt Isotopes». Physical Review. 53 (10): 847–848. Bibcode:1938PhRv…53..847L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.53.847.

- ^ Wu, C. S. (1957). «Experimental Test of Parity Conservation in Beta Decay». Physical Review. 105 (4): 1413–1415. Bibcode:1957PhRv..105.1413W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.1413.

- ^ Wróblewski, A. K. (2008). «The Downfall of Parity – the Revolution That Happened Fifty Years Ago». Acta Physica Polonica B. 39 (2): 251. Bibcode:2008AcPPB..39..251W. S2CID 34854662.

- ^ «Richest Hole In The Mountain». Popular Mechanics: 65–69. 1952.

- ^ Overland, Indra (2019-03-01). «The geopolitics of renewable energy: Debunking four emerging myths». Energy Research & Social Science. 49: 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.018. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ Ptitsyn, D. A.; Chechetkin, V. M. (1980). «Creation of the Iron-Group Elements in a Supernova Explosion». Soviet Astronomy Letters. 6: 61–64. Bibcode:1980SvAL….6…61P.

- ^ Nuccio, Pasquale Mario and Valenza, Mariano (1979). «Determination of metallic iron, nickel and cobalt in meteorites» (PDF). Rendiconti Societa Italiana di Mineralogia e Petrografia. 35 (1): 355–360.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Kerr, Paul F. (1945). «Cattierite and Vaesite: New Co-Ni Minerals from the Belgian Kongo» (PDF). American Mineralogist. 30: 483–492. - ^ Buckley, A. N. (1987). «The Surface Oxidation of Cobaltite». Australian Journal of Chemistry. 40 (2): 231. doi:10.1071/CH9870231.

- ^ Young, R. (1957). «The geochemistry of cobalt». Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 13 (1): 28–41. Bibcode:1957GeCoA..13…28Y. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(57)90056-X.

- ^

Talhout, Reinskje; Schulz, Thomas; Florek, Ewa; Van Benthem, Jan; Wester, Piet; Opperhuizen, Antoon (2011). «Hazardous Compounds in Tobacco Smok». International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 8 (12): 613–628. doi:10.3390/ijerph8020613. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 3084482. PMID 21556207. - ^

Pourkhabbaz, A; Pourkhabbaz, H (2012). «Investigation of Toxic Metals in the Tobacco of Different Iranian Cigarette Brands and Related Health Issues». Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 15 (1): 636–644. PMC 3586865. PMID 23493960. - ^ Bundy, Randelle M.; Tagliabue, Alessandro; Hawco, Nicholas J.; Morton, Peter L.; Twining, Benjamin S.; Hatta, Mariko; Noble, Abigail E.; Cape, Mattias R.; John, Seth G.; Cullen, Jay T.; Saito, Mak A. (1 October 2020). «Elevated sources of cobalt in the Arctic Ocean». Biogeosciences. 17 (19): 4745–4767. Bibcode:2020BGeo…17.4745B. doi:10.5194/bg-17-4745-2020. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Noble, Abigail E.; Lamborg, Carl H.; Ohnemus, Dan C.; Lam, Phoebe J.; Goepfert, Tyler J.; Measures, Chris I.; Frame, Caitlin H.; Casciotti, Karen L.; DiTullio, Giacomo R.; Jennings, Joe; Saito, Mak A. (2012). «Basin-scale inputs of cobalt, iron, and manganese from the Benguela-Angola front to the South Atlantic Ocean». Limnology and Oceanography. 57 (4): 989–1010. Bibcode:2012LimOc..57..989N. doi:10.4319/lo.2012.57.4.0989. ISSN 1939-5590.

- ^ Cutter, Gregory A.; Bruland, Kenneth W. (2012). «Rapid and noncontaminating sampling system for trace elements in global ocean surveys». Limnology and Oceanography: Methods. 10 (6): 425–436. doi:10.4319/lom.2012.10.425.

- ^ Bruland, K. W.; Lohan, M. C. (1 December 2003). «Controls of Trace Metals in Seawater». Treatise on Geochemistry. 6: 23–47. Bibcode:2003TrGeo…6…23B. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/06105-3. ISBN 978-0-08-043751-4.

- ^ Lass, Hans Ulrich; Mohrholz, Volker (November 2008). «On the interaction between the subtropical gyre and the Subtropical Cell on the shelf of the SE Atlantic». Journal of Marine Systems. 74 (1–2): 1–43. Bibcode:2008JMS….74….1L. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.09.008.

- ^ International Seabed Authority. «Cobalt-Rich Crusts» (PDF). isa.org. International Seabed Authority. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. «DeepCCZ: Deep-sea Mining Interests in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research». oceanexplorer.noaa.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Hawco, Nicholas J.; McIlvin, Matthew M.; Bundy, Randelle M.; Tagliabue, Alessandro; Goepfert, Tyler J.; Moran, Dawn M.; Valentin-Alvarado, Luis; DiTullio, Giacomo R.; Saito, Mak A. (7 July 2020). «Minimal cobalt metabolism in the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (27): 15740–15747. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11715740H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2001393117. PMC 7354930. PMID 32576688.

- ^ Lass, Hans Ulrich; Mohrholz, Volker (November 2008). «On the interaction between the subtropical gyre and the Subtropical Cell on the shelf of the SE Atlantic». Journal of Marine Systems. 74 (1–2): 1–43. Bibcode:2008JMS….74….1L. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.09.008.

- ^ Karthikeyan, Panneerselvam; Marigoudar, Shambanagouda Rudragouda; Nagarjuna, Avula; Sharma, K. Venkatarama (2019). «Toxicity assessment of cobalt and selenium on marine diatoms and copepods». Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology. 1: 36–42. doi:10.1016/j.enceco.2019.06.001.

- ^ Cobalt Statistics and Information (PDF), U.S. Geological Survey, 2018

- ^ a b c Shedd, Kim B. «Mineral Yearbook 2006: Cobalt» (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ a b c Shedd, Kim B. «Commodity Report 2008: Cobalt» (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ a b Henry Sanderson (March 14, 2017). «Cobalt’s meteoric rise at risk from Congo’s Katanga». Financial Times.

- ^ Murray W. Hitzman, Arthur A. Bookstrom, John F. Slack, and Michael L. Zientek (2017). «Cobalt—Styles of Deposits and the Search for Primary Deposits». USGS. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ «Cobalt price: BMW avoids the Congo conundrum – for now». Mining.com. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Davis, Joseph R. (2000). ASM specialty handbook: nickel, cobalt, and their alloys. ASM International. p. 347. ISBN 0-87170-685-7.

- ^

«Cobalt» (PDF). United States Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries. January 2016. pp. 52–53. - ^ Thomas Wilson (October 26, 2017). «We’ll All Be Relying on Congo to Power Our Electric Cars».

- ^ «Glencore’s cobalt stock overhang contains prices despite mine suspension». Reuters. 8 August 2019.

- ^ «Glencore closes Mutanda mine, 20% of global cobalt supply comes offline». Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. 28 November 2019.

the mine would be placed on care and maintenance for a period of no less than two years

- ^

«African Mineral Production» (PDF). British Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-06-06. - ^ a b

Frankel, Todd C. (2016-09-30). «Cobalt mining for lithium ion batteries has a high human cost». The Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-10-18. - ^ Mucha, Lena; Sadof, Karly Domb; Frankel, Todd C. (2018-02-28). «Perspective — The hidden costs of cobalt mining». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ^

Todd C. Frankel (September 30, 2016). «THE COBALT PIPELINE: Tracing the path from deadly hand-dug mines in Congo to consumers’ phones and laptops». The Washington Post. - ^ Crawford, Alex. Meet Dorsen, 8, who mines cobalt to make your smartphone work. Sky News UK. Retrieved on 2018-01-07.

- ^ Are you holding a product of child labour right now? (Video). Sky News UK (2017-02-28). Retrieved on 2018-01-07.

- ^

Child labour behind smart phone and electric car batteries. Amnesty International (2016-01-19). Retrieved on 2018-01-07. - ^

Reisinger, Don. (2017-03-03) Child Labor Revelation Prompts Apple to Make Supplier Policy Change. Fortune. Retrieved on 2018-01-07. - ^ Frankel, Todd C. (2017-03-03) Apple cracks down further on cobalt supplier in Congo as child labor persists. The Washington Post. Retrieved on 2018-01-07.

- ^

Wellmer, Friedrich-Wilhelm; Becker-Platen, Jens Dieter. «Global Nonfuel Mineral Resources and Sustainability». Retrieved 2009-05-16. - ^ Audit Report on Congo Dongfang International Mining sarl. DNV-GL Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^

«CAMEC – The Cobalt Champion» (PDF). International Mining. July 2008. Retrieved 2011-11-18. - ^

Amy Witherden (6 July 2009). «Daily podcast – July 6, 2009». Mining weekly. Retrieved 2011-11-15. - ^ Mining Journal «The [Ivanhoe] pullback investors have been waiting for», Aspermont Ltd., London, UK, February 22, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Shabalala, Zandi «Cobalt to be declared a strategic mineral in Congo», Reuters, March 14, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.]

- ^ Reuters «Congo’s Kabila signs into law new mining code», March 14, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.]

- ^ [1] «DRC declares cobalt ‘strategic'», Mining Journal, December 4, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2020.]

- ^ «U.S. cobalt lawsuit puts spotlight on ‘sustainable’ tech». Sustainability Times. 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ «Apple, Google Fight Blame For Child Labor In Cobalt Mines — Law360». www.law360.com. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ The Canadian Ghost Town That Tesla Is Bringing Back to Life. Bloomberg (2017-10-31). Retrieved on 2018-01-07.

- ^ «Cubas Nickel Production Exceeds 50000 metric tons». Cuba Business Report. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^

Donachie, Matthew J. (2002). Superalloys: A Technical Guide. ASM International. ISBN 978-0-87170-749-9. - ^ Campbell, Flake C (2008-06-30). «Cobalt and Cobalt Alloys». Elements of metallurgy and engineering alloys. pp. 557–558. ISBN 978-0-87170-867-0.

- ^ Michel, R.; Nolte, M.; Reich M.; Löer, F. (1991). «Systemic effects of implanted prostheses made of cobalt-chromium alloys». Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 110 (2): 61–74. doi:10.1007/BF00393876. PMID 2015136. S2CID 28903564.

- ^ Disegi, John A. (1999). Cobalt-base Aloys for Biomedical Applications. ASTM International. p. 34. ISBN 0-8031-2608-5.

- ^ Luborsky, F. E.; Mendelsohn, L. I.; Paine, T. O. (1957). «Reproducing the Properties of Alnico Permanent Magnet Alloys with Elongated Single-Domain Cobalt-Iron Particles». Journal of Applied Physics. 28 (344): 344. Bibcode:1957JAP….28..344L. doi:10.1063/1.1722744.

- ^ Biggs, T.; Taylor, S. S.; Van Der Lingen, E. (2005). «The Hardening of Platinum Alloys for Potential Jewellery Application». Platinum Metals Review. 49: 2–15. doi:10.1595/147106705X24409.

- ^ a b c

Hawkins, M. (2001). «Why we need cobalt». Applied Earth Science. 110 (2): 66–71. Bibcode:2001AdEaS.110…66H. doi:10.1179/aes.2001.110.2.66. S2CID 137529349. - ^ a b

Armstrong, R. D.; Briggs, G. W. D.; Charles, E. A. (1988). «Some effects of the addition of cobalt to the nickel hydroxide electrode». Journal of Applied Electrochemistry. 18 (2): 215–219. doi:10.1007/BF01009266. S2CID 97073898. - ^

Zhang, P.; Yokoyama, Toshiro; Itabashi, Osamu; Wakui, Yoshito; Suzuki, Toshishige M.; Inoue, Katsutoshi (1999). «Recovery of metal values from spent nickel–metal hydride rechargeable batteries». Journal of Power Sources. 77 (2): 116–122. Bibcode:1999JPS….77..116Z. doi:10.1016/S0378-7753(98)00182-7. - ^ West, Karl (29 July 2017). «Carmakers’ electric dreams depend on supplies of rare minerals». The Guardian. eISSN 1756-3224. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ Castellano, Robert (13 October 2017). «How To Minimize Tesla’s Cobalt Supply Chain Risk». Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ a b «As Cobalt Supply Tightens, LiCo Energy Metals Announces Two New Cobalt Mines». cleantechnica.com. 2017-11-28. Retrieved 2018-01-07.

- ^ Shilling, Erik (31 October 2017). «We May Not Have Enough Minerals To Even Meet Electric Car Demand». Jalopnik. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ «State of Charge: EVs, Batteries and Battery Materials (Free Report from @AdamasIntel)». Adamas Intelligence. 20 September 2019. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ «Muskmobiles running rivals off the road». MINING.COM. 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-09-30.

- ^ «Electric car future may depend on deep sea mining». BBC News. 13 November 2019.

- ^

Hermes, Jennifer. (2017-05-31) Tesla & GE Face Major Shortage Of Ethically Sourced Cobalt. Environmentalleader.com. Retrieved on 2018-01-07. - ^ Electric cars yet to turn cobalt market into gold mine – Nornickel. MINING.com (2017-10-30). Retrieved on 2018-01-07.

- ^ «Why Have Cobalt Prices Crashed». International Banker. 31 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-11-30.

- ^ «Cobalt Prices and Cobalt Price Charts — InvestmentMine». www.infomine.com.

- ^ «Tesla joins «Fair Cobalt Alliance» to improve DRC artisanal mining». mining-technology.com. 2020-09-08. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Klender, Joey (2020-09-08). «Tesla joins Fair Cobalt Alliance in support of moral mining efforts». teslarati.com. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ CObalt-free Batteries for FutuRe Automotive Applications website

- ^ COBRA project at European Union

- ^ Yoo-chul, Kim (2020-08-14). «Tesla’s battery strategy, implications for LG and Samsung». koreatimes.co.kr. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (2020-08-31). «Lithium & Nickel & Tesla, Oh My!». cleantechnica.com. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Calma, Justine (2020-09-22). «Tesla to make EV battery cathodes without cobalt». theverge.com. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ «Cobalt Drier for Paints | Cobalt Cem-All®». Borchers. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ Weatherhead, R. G. (1980), Weatherhead, R. G. (ed.), «Catalysts, Accelerators and Inhibitors for Unsaturated Polyester Resins», FRP Technology: Fibre Reinforced Resin Systems, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 204–239, doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8721-0_10, ISBN 978-94-009-8721-0, retrieved 2021-05-15

- ^ «The product selector | AOC». aocresins.com. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ «Comar Chemicals — Polyester Acceleration». www.comarchemicals.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^

Khodakov, Andrei Y.; Chu, Wei & Fongarland, Pascal (2007). «Advances in the Development of Novel Cobalt Fischer-Tropsch Catalysts for Synthesis of Long-Chain Hydrocarbons and Clean Fuels». Chemical Reviews. 107 (5): 1692–1744. doi:10.1021/cr050972v. PMID 17488058. - ^

Hebrard, Frédéric & Kalck, Philippe (2009). «Cobalt-Catalyzed Hydroformylation of Alkenes: Generation and Recycling of the Carbonyl Species, and Catalytic Cycle». Chemical Reviews. 109 (9): 4272–4282. doi:10.1021/cr8002533. PMID 19572688. - ^

Overman, Frederick (1852). A treatise on metallurgy. D. Appleton & company. pp. 631–637. - ^

Muhlethaler, Bruno; Thissen, Jean; Muhlethaler, Bruno (1969). «Smalt». Studies in Conservation. 14 (2): 47–61. doi:10.2307/1505347. JSTOR 1505347. - ^

Gehlen, A. F. (1803). «Ueber die Bereitung einer blauen Farbe aus Kobalt, die eben so schön ist wie Ultramarin. Vom Bürger Thenard». Neues Allgemeines Journal der Chemie, Band 2. H. Frölich. (German translation from L. J. Thénard; Journal des Mines; Brumaire 12 1802; p 128–136) - ^

Witteveen, H. J.; Farnau, E. F. (1921). «Colors Developed by Cobalt Oxides». Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 13 (11): 1061–1066. doi:10.1021/ie50143a048. - ^

Venetskii, S. (1970). «The charge of the guns of peace». Metallurgist. 14 (5): 334–336. doi:10.1007/BF00739447. S2CID 137225608. - ^

Mandeville, C.; Fulbright, H. (1943). «The Energies of the γ-Rays from Sb122, Cd115, Ir192, Mn54, Zn65, and Co60«. Physical Review. 64 (9–10): 265–267. Bibcode:1943PhRv…64..265M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.64.265. - ^

Wilkinson, V. M; Gould, G (1998). Food irradiation: a reference guide. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-85573-359-6. - ^

Blakeslee, Sandra (1984-05-01). «The Juarez accident». The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-06. - ^

«Ciudad Juarez orphaned source dispersal, 1983». Wm. Robert Johnston. 2005-11-23. Retrieved 2009-10-24. - ^

National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Radiation Source Use and Replacement; National Research Council (U.S.). Nuclear and Radiation Studies Board (January 2008). Radiation source use and replacement: abbreviated version. National Academies Press. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-0-309-11014-3. Retrieved 2011-04-29. - ^

Meyer, Theresa (2001-11-30). Physical Therapist Examination Review. p. 368. ISBN 978-1-55642-588-2. - ^

Kalnicky, D.; Singhvi, R. (2001). «Field portable XRF analysis of environmental samples». Journal of Hazardous Materials. 83 (1–2): 93–122. doi:10.1016/S0304-3894(00)00330-7. PMID 11267748. - ^

Payne, L. R. (1977). «The Hazards of Cobalt». Occupational Medicine. 27 (1): 20–25. doi:10.1093/occmed/27.1.20. PMID 834025. - ^

Puri-Mirza, Amna (2020). «Morocco Cobalt Production». Statistica. - ^ Davis, Joseph R; Handbook Committee, ASM International (2000-05-01). «Cobalt». Nickel, cobalt, and their alloys. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-87170-685-0.

- ^ Committee On Technological Alternatives For Cobalt Conservation, National Research Council (U.S.); National Materials Advisory Board, National Research Council (U.S.) (1983). «Ground–Coat Frit». Cobalt conservation through technological alternatives. p. 129.

- ^ Yamada, Kazuhiro (2013). «Chapter 9. Cobalt: Its Role in Health and Disease». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 295–320. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_9. PMID 24470095.

- ^

Cracan, Valentin; Banerjee, Ruma (2013). «Chapter 10 Cobalt and Corrinoid Transport and Biochemistry». In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 333–374. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_10. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. PMID 23595677. electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402. - ^ Schwarz, F. J.; Kirchgessner, M.; Stangl, G. I. (2000). «Cobalt requirement of beef cattle – feed intake and growth at different levels of cobalt supply». Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 83 (3): 121–131. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0396.2000.00258.x.

- ^ Voet, Judith G.; Voet, Donald (1995). Biochemistry. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. p. 675. ISBN 0-471-58651-X. OCLC 31819701.

- ^ Smith, David M.; Golding, Bernard T.; Radom, Leo (1999). «Understanding the Mechanism of B12-Dependent Methylmalonyl-CoA Mutase: Partial Proton Transfer in Action». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 121 (40): 9388–9399. doi:10.1021/ja991649a.

- ^ Kobayashi, Michihiko; Shimizu, Sakayu (1999). «Cobalt proteins». European Journal of Biochemistry. 261 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00186.x. PMID 10103026.

- ^ «Soils». Waikato University. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ a b McDowell, Lee Russell (2008). Vitamins in Animal and Human Nutrition (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-470-37668-3.

- ^ Australian Academy of Science > Deceased Fellows > Hedley Ralph Marston 1900–1965 Accessed 12 May 2013.

- ^ Snook, Laurence C. (1962). «Cobalt: its use to control wasting disease». Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia. 4. 3 (11): 844–852.

- ^ «Cobalt 356891». Sigma-Aldrich. 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Donaldson, John D. and Beyersmann, Detmar (2005) «Cobalt and Cobalt Compounds» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_281.pub2

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0146». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Morin Y; Tětu A; Mercier G (1969). «Quebec beer-drinkers’ cardiomyopathy: Clinical and hemodynamic aspects». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 156 (1): 566–576. Bibcode:1969NYASA.156..566M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb16751.x. PMID 5291148. S2CID 7422045.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G. & Barceloux, Donald (1999). «Cobalt». Clinical Toxicology. 37 (2): 201–216. doi:10.1081/CLT-100102420. PMID 10382556.

- ^ [PDF]

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; van Heerden, Dominique; Mackintosh, Eliza (May 2018). «Dirty Energy». CNN. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Basketter, David A.; Angelini, Gianni; Ingber, Arieh; Kern, Petra S.; Menné, Torkil (2003). «Nickel, chromium and cobalt in consumer products: revisiting safe levels in the new millennium». Contact Dermatitis. 49 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2003.00149.x. PMID 14641113. S2CID 24562378.

Further reading[edit]

- Harper, E. M.; Kavlak, G.; Graedel, T. E. (2012). «Tracking the metal of the goblins: Cobalt’s cycle of use». Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (2): 1079–86. Bibcode:2012EnST…46.1079H. doi:10.1021/es201874e. PMID 22142288. S2CID 206948482.

- Narendrula, R.; Nkongolo, K. K.; Beckett, P. (2012). «Comparative soil metal analyses in Sudbury (Ontario, Canada) and Lubumbashi (Katanga, DR-Congo)». Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 88 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1007/s00128-011-0485-7. PMID 22139330. S2CID 34070357.

- Pauwels, H.; Pettenati, M.; Greffié, C. (2010). «The combined effect of abandoned mines and agriculture on groundwater chemistry». Journal of Contaminant Hydrology. 115 (1–4): 64–78. Bibcode:2010JCHyd.115…64P. doi:10.1016/j.jconhyd.2010.04.003. PMID 20466452.

- Bulut, G. (2006). «Recovery of copper and cobalt from ancient slag». Waste Management & Research. 24 (2): 118–24. doi:10.1177/0734242X06063350. PMID 16634226. S2CID 24931095.

- Jefferson, J. A.; Escudero, E.; Hurtado, M. E.; Pando, J.; Tapia, R.; Swenson, E. R.; Prchal, J.; Schreiner, G. F.; Schoene, R. B.; Hurtado, A.; Johnson, R. J. (2002). «Excessive erythrocytosis, chronic mountain sickness, and serum cobalt levels». Lancet. 359 (9304): 407–8. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07594-3. PMID 11844517. S2CID 12319751.

- Løvold, T. V.; Haugsbø, L. (1999). «Cobalt mining factory—diagnoses 1822-32». Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening. 119 (30): 4544–6. PMID 10827501.

- Bird, G. A.; Hesslein, R. H.; Mills, K. H.; Schwartz, W. J.; Turner, M. A. (1998). «Bioaccumulation of radionuclides in fertilized Canadian Shield lake basins». The Science of the Total Environment. 218 (1): 67–83. Bibcode:1998ScTEn.218…67B. doi:10.1016/s0048-9697(98)00179-x. PMID 9718743.