The fairy tale commemorated on a Soviet Union stamp

The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Russian: «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», romanized: Skazka o rybake i rybke) is a fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin, published 1835.

The tale is about a fisherman who manages to catch a «Golden Fish» which promises to fulfill any wish of his in exchange for its freedom.

Textual notes[edit]

Pushkin wrote the tale in autumn 1833[1] and it was first published in the literary magazine Biblioteka dlya chteniya in May 1835.

English translations[edit]

Robert Chandler has published an English translation, «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish» (2012).[2][3]

Grimms’ Tales[edit]

It has been believed that Pushkin’s is an original tale based on the Grimms’ tale,[4] «The Fisherman and his Wife».[a]

Azadovsky wrote monumental articles on Pushkin’s sources, his nurse «Arina Rodionovna», and the «Brothers Grimm» demonstrating that tales recited to Pushkin in his youth were often recent translations propagated «word of mouth to a largely unlettered peasantry», rather than tales passed down in Russia, as John Bayley explains.[6]

Still, Bayley»s estimation, the derivative nature does not not diminish the reader’s ability to appreciate «The Fisherman and the Fish» as «pure folklore», though at a lesser scale than other masterpieces.[6] In a similar vein, Sergei Mikhailovich Bondi [ru] emphatically accepted Azadovsky’s verdict on Pushkin’s use of Grimm material, but emphasized that Pushkin still crafted Russian fairy tales out of them.[7]

In a draft version, Pushkin has the fisherman’s wife wishing to be the Roman Pope,[8] thus betraying his influence from the Brother Grimms’ telling, where the wife also aspires to be a she-Pope.[9]

Afanasyev’s collection[edit]

The tale is also very similar in plot and motif to the folktale «The Goldfish» Russian: Золотая рыбка which is No. 75 in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection (1855–1867), which is obscure as to its collected source.[7]

Russian scholarship abounds in discussion of the interrelationship between Pushkin’s verse and Afanasyev’s skazka.[7] Pushkin had been shown Vladimir Dal’s collection of folktales.[7] He seriously studied genuine folktales, and literary style was spawned from absorbing them, but conversely, popular tellings were influenced by Pushkin’s published versions also.[7]

At any rate, after Norbert Guterman’s English translation of Asfaneyev’s «The Goldfish» (1945) appeared,[10] Stith Thompson included it in his One Hundred Favorite Folktales, so this version became the referential Russian variant for the ATU 555 tale type.[11]

Plot summary[edit]

In Pushkin’s poem, an old man and woman have been living poorly for many years. They have a small hut, and every day the man goes out to fish. One day, he throws in his net and pulls out seaweed two times in succession, but on the third time he pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. However, the old man is scared by the fact that a fish can speak; he says he does not want anything, and lets the fish go.

When he returns and tells his wife about the golden fish, she gets angry and tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then, in succession, the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the tsarina, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

Analysis[edit]

The Afanasiev version «The Goldfish» is catalogued as type ATU 555, «(The) Fisherman and his Wife», the type title deriving from the representative tale, Brothers Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife.[11][12][13]

The tale exhibits the «function» of «lack» to use the terminology of Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis, but even while the typical fairy tale is supposed to «liquidate’ the lack with a happy ending, this tale type breaches the rule by reducing the Russian couple back to their original state of dire poverty, hence it is a case of «lack not liquidated».[13] The Poppovian structural analysis sets up «The Goldfish» tale for comparison with a similar Russian fairy tale, «The Greedy Old Woman (Wife)».[13]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1866 — Le Poisson doré (The Golden Fish), «fantastic ballet», choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon, the music by Ludwig Minkus.

- 1917 — The Fisherman and the Fish by Nikolai Tcherepnin, op. 41 for orchestra

- 1937 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, animated film by Aleksandr Ptushko.[14]

- 1950 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, classic traditionally animated film by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky.,[15]

- 2002 — About the Fisherman and the Goldfish, Russia, stop-motion film by Nataliya Dabizha.[16]

See also[edit]

- Odnoklassniki.ru: Click for luck, comedy film (2013)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ D. N. Medrish [ru] also opining that «we have folklore texts that arose under the indisputable Pushkin influence».[5]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction.

- ^ Chandler (2012).

- ^ Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction and Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Medrish, D. N. (1980) Literatura i fol’klornaya traditsiya. Voprosy poetiki Литература и фольклорная традиция. Вопросы поэтики [Literature and folklore tradition. Questions of poetics]. Saratov University p. 97. apud Sugino (2019), p. 8

- ^ a b Bayley, John (1971). «2. Early Poems». Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 53. ISBN 0521079543.

- ^ a b c d e Sugino (2019), p. 8.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna (1997). Meyer, Ronald (ed.). My Half Century: Selected Prose. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 387, n38. ISBN 0810114852.

- ^ Sugino (2019), p. 10.

- ^ Guterman (2013). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish» pp. 528–532.

- ^ a b Thompson (1974). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish». pp. 241–243. Endnote, p. 437 «Type 555».

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The types of international folktales. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 273. ISBN 9789514109638.

- ^ a b c Somoff, Victoria (2019), Canepa, Nancy L. (ed.), «Morals and Miracles: The Case of ATU 555 ‘The Fisherman and His Wife’«, Teaching Fairy Tales, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0814339360

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1937)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «About the Fisherman and the Fish (2002)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Bibliography

- Briggs, A. D. P. (1982). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Chandler, Robert, ed. (2012). «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish». Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141392541.

- Guterman, Norbert, tr., ed. (2013) [1945]. «The Goldfish». Russian Fairy Tales. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Aleksandr Afanas’ev (orig. ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 528–532. ISBN 0307829766.

- Sugino, Yuri (2019), «Pushkinskaya «Skazka o rybake i rybke» v kontekste Vtoroy boldinskoy oseni» Пушкинская «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» в контексте Второй болдинской осени [Pushkin’s“The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”in the Context of the Second Boldin Autumn], Japanese Slavic and East European Studies, 39: 2–25, doi:10.5823/jsees.39.0_2

- Thompson, Stith, ed. (1974) [1968]. «51. The Goldfish». One Hundred Favorite Folktales. Indiana University Press. pp. 241–243, endnote p. 437. ISBN 0253201721.

- Pilinovsky, Helen (2014), «(Review): Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov by Robert Chandler», Marvels & Tales, 28 (2): 395–397, doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.2.0395

External links[edit]

The fairy tale commemorated on a Soviet Union stamp

The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Russian: «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», romanized: Skazka o rybake i rybke) is a fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin, published 1835.

The tale is about a fisherman who manages to catch a «Golden Fish» which promises to fulfill any wish of his in exchange for its freedom.

Textual notes[edit]

Pushkin wrote the tale in autumn 1833[1] and it was first published in the literary magazine Biblioteka dlya chteniya in May 1835.

English translations[edit]

Robert Chandler has published an English translation, «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish» (2012).[2][3]

Grimms’ Tales[edit]

It has been believed that Pushkin’s is an original tale based on the Grimms’ tale,[4] «The Fisherman and his Wife».[a]

Azadovsky wrote monumental articles on Pushkin’s sources, his nurse «Arina Rodionovna», and the «Brothers Grimm» demonstrating that tales recited to Pushkin in his youth were often recent translations propagated «word of mouth to a largely unlettered peasantry», rather than tales passed down in Russia, as John Bayley explains.[6]

Still, Bayley»s estimation, the derivative nature does not not diminish the reader’s ability to appreciate «The Fisherman and the Fish» as «pure folklore», though at a lesser scale than other masterpieces.[6] In a similar vein, Sergei Mikhailovich Bondi [ru] emphatically accepted Azadovsky’s verdict on Pushkin’s use of Grimm material, but emphasized that Pushkin still crafted Russian fairy tales out of them.[7]

In a draft version, Pushkin has the fisherman’s wife wishing to be the Roman Pope,[8] thus betraying his influence from the Brother Grimms’ telling, where the wife also aspires to be a she-Pope.[9]

Afanasyev’s collection[edit]

The tale is also very similar in plot and motif to the folktale «The Goldfish» Russian: Золотая рыбка which is No. 75 in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection (1855–1867), which is obscure as to its collected source.[7]

Russian scholarship abounds in discussion of the interrelationship between Pushkin’s verse and Afanasyev’s skazka.[7] Pushkin had been shown Vladimir Dal’s collection of folktales.[7] He seriously studied genuine folktales, and literary style was spawned from absorbing them, but conversely, popular tellings were influenced by Pushkin’s published versions also.[7]

At any rate, after Norbert Guterman’s English translation of Asfaneyev’s «The Goldfish» (1945) appeared,[10] Stith Thompson included it in his One Hundred Favorite Folktales, so this version became the referential Russian variant for the ATU 555 tale type.[11]

Plot summary[edit]

In Pushkin’s poem, an old man and woman have been living poorly for many years. They have a small hut, and every day the man goes out to fish. One day, he throws in his net and pulls out seaweed two times in succession, but on the third time he pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. However, the old man is scared by the fact that a fish can speak; he says he does not want anything, and lets the fish go.

When he returns and tells his wife about the golden fish, she gets angry and tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then, in succession, the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the tsarina, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

Analysis[edit]

The Afanasiev version «The Goldfish» is catalogued as type ATU 555, «(The) Fisherman and his Wife», the type title deriving from the representative tale, Brothers Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife.[11][12][13]

The tale exhibits the «function» of «lack» to use the terminology of Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis, but even while the typical fairy tale is supposed to «liquidate’ the lack with a happy ending, this tale type breaches the rule by reducing the Russian couple back to their original state of dire poverty, hence it is a case of «lack not liquidated».[13] The Poppovian structural analysis sets up «The Goldfish» tale for comparison with a similar Russian fairy tale, «The Greedy Old Woman (Wife)».[13]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1866 — Le Poisson doré (The Golden Fish), «fantastic ballet», choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon, the music by Ludwig Minkus.

- 1917 — The Fisherman and the Fish by Nikolai Tcherepnin, op. 41 for orchestra

- 1937 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, animated film by Aleksandr Ptushko.[14]

- 1950 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, classic traditionally animated film by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky.,[15]

- 2002 — About the Fisherman and the Goldfish, Russia, stop-motion film by Nataliya Dabizha.[16]

See also[edit]

- Odnoklassniki.ru: Click for luck, comedy film (2013)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ D. N. Medrish [ru] also opining that «we have folklore texts that arose under the indisputable Pushkin influence».[5]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction.

- ^ Chandler (2012).

- ^ Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction and Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Medrish, D. N. (1980) Literatura i fol’klornaya traditsiya. Voprosy poetiki Литература и фольклорная традиция. Вопросы поэтики [Literature and folklore tradition. Questions of poetics]. Saratov University p. 97. apud Sugino (2019), p. 8

- ^ a b Bayley, John (1971). «2. Early Poems». Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 53. ISBN 0521079543.

- ^ a b c d e Sugino (2019), p. 8.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna (1997). Meyer, Ronald (ed.). My Half Century: Selected Prose. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 387, n38. ISBN 0810114852.

- ^ Sugino (2019), p. 10.

- ^ Guterman (2013). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish» pp. 528–532.

- ^ a b Thompson (1974). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish». pp. 241–243. Endnote, p. 437 «Type 555».

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The types of international folktales. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 273. ISBN 9789514109638.

- ^ a b c Somoff, Victoria (2019), Canepa, Nancy L. (ed.), «Morals and Miracles: The Case of ATU 555 ‘The Fisherman and His Wife’«, Teaching Fairy Tales, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0814339360

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1937)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «About the Fisherman and the Fish (2002)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Bibliography

- Briggs, A. D. P. (1982). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Chandler, Robert, ed. (2012). «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish». Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141392541.

- Guterman, Norbert, tr., ed. (2013) [1945]. «The Goldfish». Russian Fairy Tales. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Aleksandr Afanas’ev (orig. ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 528–532. ISBN 0307829766.

- Sugino, Yuri (2019), «Pushkinskaya «Skazka o rybake i rybke» v kontekste Vtoroy boldinskoy oseni» Пушкинская «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» в контексте Второй болдинской осени [Pushkin’s“The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”in the Context of the Second Boldin Autumn], Japanese Slavic and East European Studies, 39: 2–25, doi:10.5823/jsees.39.0_2

- Thompson, Stith, ed. (1974) [1968]. «51. The Goldfish». One Hundred Favorite Folktales. Indiana University Press. pp. 241–243, endnote p. 437. ISBN 0253201721.

- Pilinovsky, Helen (2014), «(Review): Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov by Robert Chandler», Marvels & Tales, 28 (2): 395–397, doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.2.0395

External links[edit]

| Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке | |

Иллюстрация Ивана Билибина |

|

| Жанр: |

сказка |

|---|---|

| Автор: |

Александр Сергеевич Пушкин |

| Язык оригинала: |

русский |

| Год написания: |

1833 |

| Публикация: |

1835[1] |

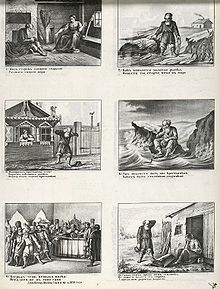

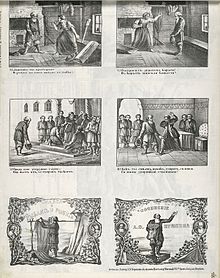

Литографии А.В. Морозова к сказке

Литографии А.В. Морозова к сказке

«Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» — сказка Александра Сергеевича Пушкина. Написана 14 октября 1833 года. Впервые напечатана в 1835 году в журнале «Библиотека для чтения»[1]. В рукописи есть помета: «18 песнь сербская». Эта помета означает, что Пушкин собирался включить ее в состав «Песен западных славян». С этим циклом сближает сказку и стихотворный размер.

Содержание

- 1 Сюжет

- 2 Источники сюжета

- 3 Театрально-музыкальные и экранизированные постановки

- 4 Примечания

- 5 Ссылки

- 6 См. также

Сюжет

Старик с женой живут у моря. Старик добывает пропитание рыбной ловлей и однажды в его сети попадается необычная золотая рыбка, способная говорить человеческим языком. Рыбка молит отпустить ее в море и старик отпускает её, не прося награды. Возвратившись домой, он рассказывает о произошедшем жене. Она называет его дурачиной и простофилей, но требует, чтобы он вернулся к морю, позвал рыбку и потребовал награду, хотя бы новое корыто. Старик зовёт рыбку у моря, она появляется и обещает исполнить его желание, говоря: «Ступай себе с Богом». Возвратившись домой, он видит у жены новое корыто. Однако «аппетиты» старухи все возрастают — она заставляет мужа возвращаться к рыбке снова и снова, требуя (для себя) все новых и новых наград. Море, к которому подходит старик, каждый раз изменяется от спокойного ко все более взволнованному, а под конец — штормящему. В определенный момент старуха демонстрирует презрение к супругу, который является источником ее успехов и требует, чтобы рыбка сделала ее «владычицей морскою», причем сама рыбка должна была бы служить у нее «на посылках». Рыбка не отвечает на просьбу старика, а когда он возвращается домой, то видит старуху, лишенную всего дарованного, сидящую у старого разбитого корыта.

В русскую культуру вошла поговорка «остаться у разбитого корыта» — остаться ни с чем.

Источники сюжета

Считается, что сюжет сказки основан[2] на померанской сказке «О рыбаке и его жене» (нем. Vom Fischer und seiner Frau) из сборника Братьев Гримм,[3][4]с которой имеет очень близкие совпадения, а также перекликается с русской народной сказкой «Жадная старуха» (где вместо рыбки выступает волшебное дерево)[5].

В конце сказки братьев Гримм старуха хочет стать римским папой (намёк на папессу Иоанну). В первой рукописной редакции сказки у Пушкина старуха сидела на Вавилонской башне, а на ней была папская тиара:

Говорит старику старуха: «Не хочу быть вольною царицей, а хочу быть римскою папой».

Стал он кликать рыбку золотую

«Добро, будет она римскою папой»

Воротился старик к старухе. Перед ним монастырь латинский, на стенах латинские монахи поют латынскую обедню.

Перед ним вавилонская башня. на самой верхней на макушке сидит его старая старуха: на старухе сарочинская шапка, на шапке венец латынский, на венце тонкая спица, на спице Строфилус-птица. Поклонился старик старухе, закричал он голосом громким: «Здравствуй ты, старая баба, я, чай, твоя душенька довольна?»

Отвечает глупая старуха: «Врёшь ты, пустое городишь, совсем душенька моя не довольна — не хочу я быть римскою папой, а хочу быть владычицей морскою…»

— С. М. Бонди «Новые страницы Пушкина», «Мир», — М., 1931

Однако папа римский фигурирует также и в некоторых других произведениях русского эпоса, например, в знаменитой Голубиной Книге.

Театрально-музыкальные и экранизированные постановки

В 1950 году на киностудии «Союзмультфильм» по сценарию Михаила Вольпина выпустили мультипликационный фильм «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке». Режиссёр-постановщик — Михаил Цехановский, композитор — Юрий Левитин.

В фильме «После дождичка в четверг» (1986) Иван-царевич и Иван-подкидыш разыгрывают перед Кощеем кукольное представление этой сказки.

В 1998 году театром кукол Московского Городского Дворца детского (юношеского) творчества был поставлен спектакль-опера «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке». Режиссёр-постановщик — Елена Плотникова, композитор — Елена Могилевская.

В 2002 году на киностудии «Союзмультфильм» по сценарию Наталии Дабижи вышел мультипликационный фильм «О рыбаке и рыбке». Режиссёр-постановщик — Наталия Дабижа, композитор — Григорий Гладков.

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 А. С. Пушкин Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке // Библиотека для чтения. — 1835. — Т. X. — № 5. — С. 5—11.

- ↑ Азадовский М. К. Источники сказок Пушкина//Пушкин: Временник Пушкинской комиссии / АН СССР. Ин-т литературы. — М.; Л.: Изд-во АН СССР, 1936. — Вып. 1. — С. 134—163

- ↑ А. И. Гагарина. Народные и литературные сказки разных стран. Программа факультативных занятий для VI класса общеобразовательных учреждений с белорусским и русским языками обучения с 12-летним сроком обучения.

- ↑ Von dem Fischer un syner Fru — текст сказки на немецком языке.

О рыбаке и его жене — перевод под ред. П. Н. Полевого. - ↑ Пропп В. Я. Исторические корни Волшебной Сказки в библиотеке Максима Мошкова

Ссылки

| Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке на Викискладе? |

- О рыбаке и его жене (Gebrüder Grimm — Vom Fischer und seiner Frau (hochdeutsch). Projekt Gutenberg auf Spiegel Online)

- Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке с рисунками Вл. Конашевича, Спб., Берлин: Издательство З. И. Гржебина, 1922, на сайте «Руниверс»

- Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке с иллюстрациями Б. Дехтерева, Москва, Государственное издательство детской литературы министерства просвещения РСФСР, 1953 г. на сайте www.web-yan.com

- «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», стр 7 — 18, в сборнике «Дивре Ширъ», переводы стихотворений на иврит, М. Зингера, 1897 год

- «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» (O rybaku i złotej rybce), в переводе на польский язык

- Спектакль-опера «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» Театра кукол МГДД(Ю)Т. Фрагменты видеозаписи

См. также

- Золотая рыбка

- Сказка о рыбаке и его жене (мультфильм)

- Золотая рыбка (балет Минкуса) — балет на музыку Л.Минкуса

- Золотая рыбка (балет Черепнина) — балет на музыку Н. Н. Черепнина созданный в 1937 году

| |

|

|---|---|

| Роман в стихах | Евгений Онегин |

| Поэмы |

Руслан и Людмила • Кавказский пленник • Гавриилиада • Вадим • Братья разбойники • Бахчисарайский фонтан • Цыганы • Граф Нулин • Полтава • Тазит • Домик в Коломне • Езерский • Анджело • Медный всадник |

| Стихотворения |

Стихотворения 1813—1825 (список) • Стихотворения 1826—1836 (список) |

| Драматургия |

Борис Годунов • Русалка • Сцены из рыцарских времён Маленькие трагедии: Скупой рыцарь • Моцарт и Сальери • Каменный гость • Пир во время чумы |

| Сказки |

Жених • Сказка о попе и о работнике его Балде • Сказка о медведихе • Сказка о царе Салтане • Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке • Сказка о мёртвой царевне и о семи богатырях • Сказка о золотом петушке |

| Художественная проза |

Арап Петра Великого • История села Горюхина • Рославлев • Дубровский • Пиковая дама • Кирджали • Египетские ночи • Путешествие в Арзрум • Капитанская дочка • Роман в письмах • Повесть о стрельце Повести Белкина: Выстрел • Метель • Гробовщик • Станционный смотритель • Барышня-крестьянка |

| Историческая проза |

История Пугачёва • История Петра |

| Прочее |

Список произведений Пушкина • Переводы Пушкина с иностранных языков |

| Неоконченные произведения выделены курсивом |

Произведение Александра Сергеевича Пушкина «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» была впервые напечатана 14 мая 1835 года в журнале «Библиотека для чтения». В рукописи есть пометка: «18 песнь сербская». Эта помета означает, что Пушкин собирался включить ее в состав «Песен западных славян». С этим циклом сближает сказку и стихотворный размер.

По широко распространенной версии, сюжет сказки основан на померанской сказке «О рыбаке и его жене» из сборника сказок братьев Гримм, с которой имеет общую сюжетную линию, а также перекликается с русской народной сказкой «Жадная старуха», где вместо рыбки выступает волшебное дерево. Более древняя версия сюжета — индийская сказка «Золотая рыба», с местным национальным колоритом, здесь Золотая рыба — могущественный подводный дух Джала Камани.

Ближе к концу сказки братьев Гримм старуха становится римским папой — намек на папессу Иоанну, и стремится стать богом. В первой рукописной редакции сказки у Пушкина старуха сидела на Вавилонской башне, а на ней была папская тиара.

В окончательный вариант этот эпизод не вошел, чтобы не лишать произведение русского колорита. Однако Папа Римский фигурирует также и в некоторых других произведениях русского эпоса, например, в знаменитой Голубиной книге.

Пушкин писал сказки в наивысший расцвет своего творчества. И изначально они не были предназначены для детей, хотя сразу же вошли в круг их чтения. Сказка про золотую рыбку — не просто развлечение для детей с моралью в конце. Это в первую очередь образец творчества, традиций и верований русского народа.

Тем не менее сам сюжет сказки не является точным пересказыванием народных произведений. На самом деле немногое именно из русского фольклора нашло отражение в ней. Многие исследователи утверждают, что большая часть сказок поэта, в том числе и сказка про золотую рыбку, была заимствована из немецких сказок, собранных братьями Гримм.

Пушкин выбирал понравившийся сюжет, переделывал его по своему усмотрению и облекал его в стихотворную форму, не заботясь о том, насколько подлинными будут истории. Однако поэту удалось передать если не сюжет, то дух и характер русского народа.

Сказка про золотую рыбку не богата персонажами — их всего трое, однако и этого достаточно для увлекательного и поучительного сюжета. Образы старика и старухи диаметрально противоположны, а их взгляды на жизнь совершенно разные.

Они оба бедны, но отражают разные стороны бедности. Старик всегда бескорыстен и готов помочь в беде, потому что сам не раз бывал в таком же положении и знает, что такое горе. Он добр и спокоен, даже когда ему выпала удача, он не пользуется предложением рыбки, а просто отпускает ее на свободу. Старуха, несмотря на то же социальное положение, высокомерна, жестока и жадна. Она помыкает стариком, изводит его, постоянно бранит и вечно всем недовольна. За это она и будет наказана в конце сказки, оставшись с разбитым корытом.

Однако и старик не получает никакого вознаграждения, потому что неспособен противиться воле старухи. За свою покорность он не заслужил лучшей жизни. Здесь Пушкин описывает одну из основных черт русского народа — долготерпение. Именно оно не позволяет жить лучше и спокойнее. Образ рыбки невероятно поэтичен и пропитан народной мудростью. Она выступает в качестве высшей силы, которая до поры до времени готова исполнять желания. Однако и ее терпение не безгранично.