Halley’s Comet on 8 March 1986 |

|

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Prehistoric (observation) Edmond Halley (recognition of periodicity) |

| Discovery date | 1758 (first predicted perihelion) |

| Orbital characteristics[5] | |

| Epoch 4 August 2061 (2474040.5) | |

| Aphelion | 35.14 au[1] (aphelion: 9 December 2023)[1][2] |

| Perihelion | 0.59278 au[3] (last perihelion: 9 February 1986) (next perihelion: 28 July 2061)[3] |

|

Semi-major axis |

17.737 au |

| Eccentricity | 0.96658 |

|

Orbital period (sidereal) |

74.7 yr 75y 5m 19d (perihelion to perihelion) |

|

Mean anomaly |

0.07323° |

| Inclination | 161.96° |

|

Longitude of ascending node |

59.396° |

|

Time of perihelion |

28 July 2061[3] |

|

Argument of perihelion |

112.05° |

| Earth MOID | 0.075 au (11.2 million km)[4] |

| TJupiter | -0.598 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 15 km × 8 km[6] |

|

Mean diameter |

11 km[4] |

| Mass | 2.2×1014 kg[7] |

|

Mean density |

0.6 g/cm3 (average)[8] 0.2–1.5 g/cm3 (est.)[9] |

|

Escape velocity |

~0.002 km/s |

|

Synodic rotation period |

2.2 d (52.8 h) (?)[10] |

| Albedo | 0.04[11] |

|

Apparent magnitude |

28.2 (in 2003)[12] |

Halley’s Comet or Comet Halley, officially designated 1P/Halley, is a short-period comet visible from Earth every 75–79 years.[5] Halley is the only known short-period comet that is regularly visible to the naked eye from Earth, and thus the only naked-eye comet that can appear twice in a human lifetime.[13] Halley last appeared in the inner parts of the Solar System in 1986 and will next appear in mid-2061.

Halley’s periodic returns to the inner Solar System have been observed and recorded by astronomers around the world since at least 240 BC. But it was not until 1705 that the English astronomer Edmond Halley understood that these appearances were reappearances of the same comet. As a result of this discovery, the comet is named after Halley.[14]

During its 1986 visit to the inner Solar System, Halley’s Comet became the first comet to be observed in detail by spacecraft, providing the first observational data on the structure of a comet nucleus and the mechanism of coma and tail formation.[15][16] These observations supported a number of longstanding hypotheses about comet construction, particularly Fred Whipple’s «dirty snowball» model, which correctly predicted that Halley would be composed of a mixture of volatile ices—such as water, carbon dioxide, ammonia, and dust. The missions also provided data that substantially reformed and reconfigured these ideas; for instance, it is now understood that the surface of Halley is largely composed of dusty, non-volatile materials, and that only a small portion of it is icy.

Pronunciation[edit]

Comet Halley is commonly pronounced , rhyming with valley, or , rhyming with daily.[17][18] Colin Ronan, one of Edmond Halley’s biographers, preferred , rhyming with crawly.[19] Spellings of Halley’s name during his lifetime included Hailey, Haley, Hayley, Halley, Hawley, and Hawly, so its contemporary pronunciation is uncertain, but the version rhyming with valley seems to be preferred by current bearers of the surname.[20]

Computation of orbit[edit]

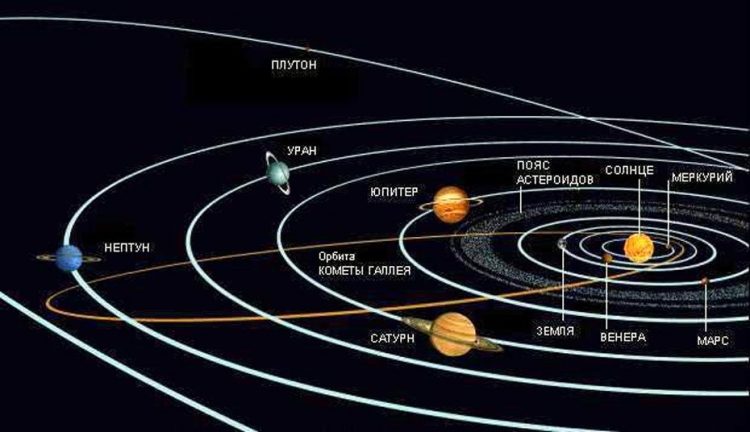

The orbital path of Halley, against the orbits of the planets (animation)

Halley was the first comet to be recognized as periodic. Until the Renaissance, the philosophical consensus on the nature of comets, promoted by Aristotle, was that they were disturbances in Earth’s atmosphere. This idea was disproved in 1577 by Tycho Brahe, who used parallax measurements to show that comets must lie beyond the Moon. Many were still unconvinced that comets orbited the Sun, and assumed instead that they must follow straight paths through the Solar System.[21]

In 1687, Sir Isaac Newton published his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in which he outlined his laws of gravity and motion. His work on comets was decidedly incomplete. Although he had suspected that two comets that had appeared in succession in 1680 and 1681 were the same comet before and after passing behind the Sun (he was later found to be correct; see Newton’s Comet),[22] he was unable to completely reconcile comets into his model.

Ultimately, it was Newton’s friend, editor and publisher, Edmond Halley, who, in his 1705 Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets, used Newton’s new laws to calculate the gravitational effects of Jupiter and Saturn on cometary orbits.[23] Having compiled a list of 24 comet observations, he calculated that the orbital elements of a second comet that had appeared in 1682 were nearly the same as those of two comets that had appeared in 1531 (observed by Petrus Apianus) and 1607 (observed by Johannes Kepler).[23][24] Halley thus concluded that all three comets were, in fact, the same object returning about every 76 years, a period that has since been found to vary between 74 and 79 years. After a rough estimate of the perturbations the comet would sustain from the gravitational attraction of the planets, he predicted its return for 1758.[25] While he had personally observed the comet around perihelion in September 1682,[26] Halley died in 1742 before he could observe its predicted return.[27]

Halley’s prediction of the comet’s return proved to be correct, although it was not seen until 25 December 1758, by Johann Georg Palitzsch, a German farmer and amateur astronomer. It did not pass through its perihelion until 13 March 1759, the attraction of Jupiter and Saturn having caused a retardation of 618 days.[28] This effect was computed before its return (with a one-month error to 13 April)[29] by a team of three French mathematicians, Alexis Clairaut, Joseph Lalande, and Nicole-Reine Lepaute.[30] The confirmation of the comet’s return was the first time anything other than planets had been shown to orbit the Sun. It was also one of the earliest successful tests of Newtonian physics, and a clear demonstration of its explanatory power.[31] The comet was first named in Halley’s honour by French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille in 1759.[31]

Some scholars have proposed that first-century Mesopotamian astronomers already had recognized Halley’s Comet as periodic.[32] This theory notes a passage in the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Horayot[33] that refers to «a star which appears once in seventy years that makes the captains of the ships err.»[34]

Researchers in 1981 attempting to calculate the past orbits of Halley by numerical integration starting from accurate observations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries could not produce accurate results further back than 837 owing to a close approach to Earth in that year. It was necessary to use ancient Chinese comet observations to constrain their calculations.[35]

Orbit and origin[edit]

Halley’s orbital period has varied between 74 and 79 years since 240 BC.[31][36] Its orbit around the Sun is highly elliptical, with an orbital eccentricity of 0.967 (with 0 being a circle and 1 being a parabolic trajectory). The perihelion, the point in the comet’s orbit when it is nearest the Sun, is 0.59 au (88 million km). This is between the orbits of Mercury and Venus. Its aphelion, or farthest distance from the Sun, is 35 au (5.2 billion km) (roughly the distance of Pluto). Unusual for an object in the Solar System, Halley’s orbit is retrograde; it orbits the Sun in the opposite direction to the planets, or, clockwise from above the Sun’s north pole. The orbit is inclined by 18° to the ecliptic, with much of it lying south of the ecliptic. (Because it is retrograde, the true inclination is 162°.)[37] Owing to the retrograde orbit, it has one of the highest velocities relative to the Earth of any object in the Solar System. The 1910 passage was at a relative velocity of 70.56 km/s (157,800 mph).[4] Because its orbit comes close to Earth’s in two places, Halley is associated with two meteor showers: the Eta Aquariids in early May, and the Orionids in late October.[38] Halley is the parent body to the Orionids, while observations conducted around the time of Halley’s appearance in 1986 suggested that the comet could additionally perturb the Eta Aquariids, although it might not be the parent of that shower.[39]

Halley is classified as a periodic or short-period comet; one with an orbit lasting 200 years or less.[40] This contrasts it with long-period comets, whose orbits last for thousands of years. Periodic comets have an average inclination to the ecliptic of only ten degrees, and an orbital period of just 6.5 years, so Halley’s orbit is atypical.[31] Most short-period comets (those with orbital periods shorter than 20 years and inclinations of 20–30 degrees or less) are called Jupiter-family comets. Those resembling Halley, with orbital periods of between 20 and 200 years and inclinations extending from zero to more than 90 degrees, are called Halley-type comets.[40][41] As of 2015, only 75 Halley-type comets have been observed, compared with 511 identified Jupiter-family comets.[42]

The orbits of the Halley-type comets suggest that they were originally long-period comets whose orbits were perturbed by the gravity of the giant planets and directed into the inner Solar System.[40] If Halley was once a long-period comet, it is likely to have originated in the Oort cloud,[41] a sphere of cometary bodies around 20,000–50,000 au from the Sun. Conversely the Jupiter-family comets are generally believed to originate in the Kuiper belt,[41] a flat disc of icy debris between 30 au (Neptune’s orbit) and 50 au from the Sun (in the scattered disc). Another point of origin for the Halley-type comets was proposed in 2008, when a trans-Neptunian object with a retrograde orbit similar to Halley’s was discovered, 2008 KV42, whose orbit takes it from just outside that of Uranus to twice the distance of Pluto. It may be a member of a new population of small Solar System bodies that serves as the source of Halley-type comets.[43]

Halley has probably been in its current orbit for 16,000–200,000 years, although it is not possible to numerically integrate its orbit for more than a few tens of apparitions, and close approaches before 837 AD can only be verified from recorded observations.[44] The non-gravitational effects can be crucial;[44] as Halley approaches the Sun, it expels jets of sublimating gas from its surface, which knock it very slightly off its orbital path. These orbital changes cause delays in its perihelion of four days on average.[45]

In 1989, Boris Chirikov and Vitold Vecheslavov performed an analysis of 46 apparitions of Halley’s Comet taken from historical records and computer simulations. These studies showed that its dynamics were chaotic and unpredictable on long timescales.[46] Halley’s projected lifetime could be as long as 10 million years. These studies also showed that many physical properties of Halley’s Comet dynamics can be approximately described by a simple symplectic map, known as the Kepler map.[47] More recent work suggests that Halley will evaporate, or split in two, within the next few tens of thousands of years, or will be ejected from the Solar System within a few hundred thousand years.[48][41] Observations by D. W. Hughes suggest that Halley’s nucleus has been reduced in mass by 80 to 90% over the last 2,000 to 3,000 revolutions.[16]

Structure and composition[edit]

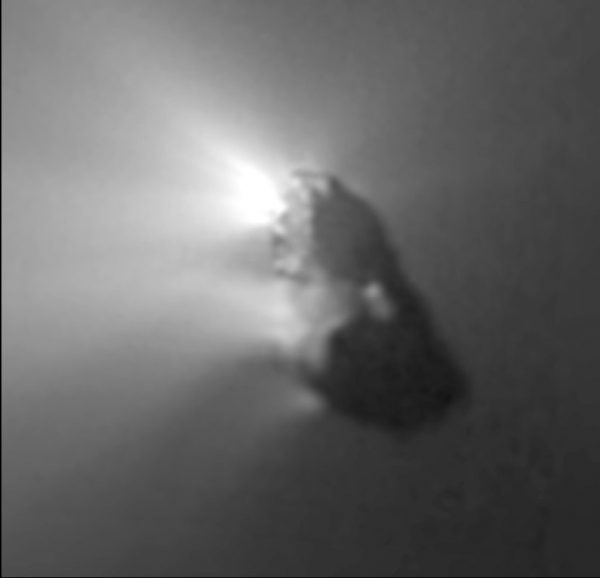

The nucleus of Halley’s Comet, imaged by the Giotto probe in 1986. The dark coloration of the nucleus can be observed, as well as the jets of dust and gas erupting from its surface.

The Giotto and Vega missions gave planetary scientists their first view of Halley’s surface and structure. Like all comets, as Halley nears the Sun, its volatile compounds (those with low boiling points, such as water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and other ices) begin to sublimate from the surface of its nucleus.[49] This causes the comet to develop a coma, or atmosphere, up to 100,000 km across.[6] Evaporation of this dirty ice releases dust particles, which travel with the gas away from the nucleus. Gas molecules in the coma absorb solar light and then re-radiate it at different wavelengths, a phenomenon known as fluorescence, whereas dust particles scatter the solar light. Both processes are responsible for making the coma visible.[13] As a fraction of the gas molecules in the coma are ionized by the solar ultraviolet radiation,[13] pressure from the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emitted by the Sun, pulls the coma’s ions out into a long tail, which may extend more than 100 million kilometres into space.[49][50] Changes in the flow of the solar wind can cause disconnection events, in which the tail completely breaks off from the nucleus.[15]

Despite the vast size of its coma, Halley’s nucleus is relatively small: barely 15 kilometres long, 8 kilometres wide and perhaps 8 kilometres thick.[b] Its shape vaguely resembles that of a peanut shell.[6] Its mass is relatively low (roughly 2.2 × 1014 kg)[7] and its average density is about 0.6 g/cm3, indicating that it is made of a large number of small pieces, held together very loosely, forming a structure known as a rubble pile.[8] Ground-based observations of coma brightness suggested that Halley’s rotation period was about 7.4 days. Images taken by the various spacecraft, along with observations of the jets and shell, suggested a period of 52 hours.[16] Given the irregular shape of the nucleus, Halley’s rotation is likely to be complex.[49] Although only 25% of Halley’s surface was imaged in detail during the flyby missions, the images revealed an extremely varied topography, with hills, mountains, ridges, depressions, and at least one crater.[16]

Halley is the most active of all the periodic comets, with others, such as Comet Encke and Comet Holmes, being one or two orders of magnitude less active.[16] Its day side (the side facing the Sun) is far more active than the night side. Spacecraft observations showed that the gases ejected from the nucleus were 80% water vapour, 17% carbon monoxide and 3–4% carbon dioxide,[51] with traces of hydrocarbons[52] although more-recent sources give a value of 10% for carbon monoxide and also include traces of methane and ammonia.[53] The dust particles were found to be primarily a mixture of carbon–hydrogen–oxygen–nitrogen (CHON) compounds common in the outer Solar System, and silicates, such as are found in terrestrial rocks.[49] The dust particles decreased in size down to the limits of detection (≈0.001 µm).[15] The ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in the water released by Halley was initially thought to be similar to that found in Earth’s ocean water, suggesting that Halley-type comets may have delivered water to Earth in the distant past. Subsequent observations showed Halley’s deuterium ratio to be far higher than that found in Earth’s oceans, making such comets unlikely sources for Earth’s water.[49]

Giotto provided the first evidence in support of Fred Whipple’s «dirty snowball» hypothesis for comet construction; Whipple postulated that comets are icy objects warmed by the Sun as they approach the inner Solar System, causing ices on their surfaces to sublimate (change directly from a solid to a gas), and jets of volatile material to burst outward, creating the coma. Giotto showed that this model was broadly correct,[49] though with modifications. Halley’s albedo, for instance, is about 4%, meaning that it reflects only 4% of the sunlight hitting it; about what one would expect for coal.[54] Thus, despite appearing brilliant white to observers on Earth, Halley’s Comet is in fact pitch black. The surface temperature of evaporating «dirty ice» ranges from 170 K (−103 °C) at higher albedo to 220 K (−53 °C) at low albedo; Vega 1 found Halley’s surface temperature to be in the range 300–400 K (27–127 °C). This suggested that only 10% of Halley’s surface was active, and that large portions of it were coated in a layer of dark dust that retained heat.[15] Together, these observations suggested that Halley was in fact predominantly composed of non-volatile materials, and thus more closely resembled a «snowy dirtball» than a «dirty snowball».[16][55]

History[edit]

Before 1066[edit]

Halley may have been recorded as early as 467 BC, but this is uncertain. A comet was recorded in ancient Greece between 468 and 466 BC; its timing, location, duration, and associated meteor shower all suggest it was Halley.[56] According to Pliny the Elder, that same year a meteorite fell in the town of Aegospotami, in Thrace. He described it as brown in colour and the size of a wagon load.[57] Chinese chroniclers also mention a comet in that year.[58]

Report of Halley’s Comet by Chinese astronomers in 240 BC (Shiji)

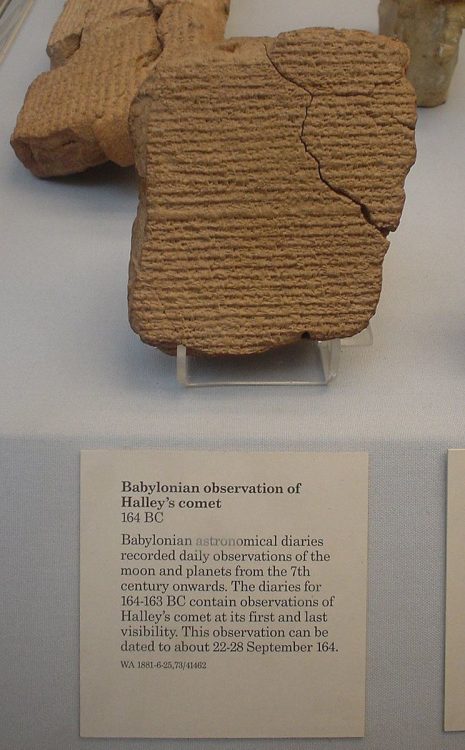

The first certain appearance of Halley’s Comet in the historical record is a description from 240 BC, in the Chinese chronicle Records of the Grand Historian or Shiji, which describes a comet that appeared in the east and moved north.[59] The only surviving record of the 164 BC apparition is found on two fragmentary Babylonian tablets, now owned by the British Museum.[59]

The apparition of 87 BC was recorded in Babylonian tablets which state that the comet was seen «day beyond day» for a month.[60] This appearance may be recalled in the representation of Tigranes the Great, an Armenian king who is depicted on coins with a crown that features, according to Vahe Gurzadyan and R. Vardanyan, «a star with a curved tail [that] may represent the passage of Halley’s Comet in 87 BC.» Gurzadyan and Vardanyan argue that «Tigranes could have seen Halley’s Comet when it passed closest to the Sun on August 6 in 87 BC» as the comet would have been a «most recordable event»; for ancient Armenians it could have heralded the New Era of the brilliant King of Kings.[61]

The apparition of 12 BC was recorded in the Book of Han by Chinese astronomers of the Han Dynasty who tracked it from August through October.[62] It passed within 0.16 au of Earth.[63] According to the Roman historian Cassius Dio, a comet appeared suspended over Rome for several days portending the death of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in that year.[64] Halley’s appearance in 12 BC, only a few years distant from the conventionally assigned date of the birth of Jesus Christ, has led some theologians and astronomers to suggest that it might explain the biblical story of the Star of Bethlehem. There are other explanations for the phenomenon, such as planetary conjunctions, and there are also records of other comets that appeared closer to the date of Jesus’ birth.[65]

Possible report of Halley’s Comet in the Talmud (MS Paris 1337).

If, as has been suggested, the reference by Yehoshua ben Hananiah in b. Horayot 10a to «a star which arises once in seventy years and misleads the sailors»[66] refers to Halley’s Comet, it may be a reference to the 66 AD appearance, because this apparition was the only one to occur during Yehoshua ben Hananiah’s lifetime.[67]

The 141 AD apparition was recorded in Chinese chronicles.[68] It was also recorded in the Tamil work Purananuru, in connection with the death of the south Indian Chera king Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai.[69]

The 374 AD and 607 approaches each came within 0.09 au of Earth.[63] The 451 AD apparition was said to herald the defeat of Attila the Hun at the Battle of Chalons.[70] The 684 AD apparition was recorded in Europe in one of the sources used by the compiler of the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicles, which contains an image 8 centuries after the event.[71] Chinese records also report it as the «broom star».[72][24] In 837, Halley’s Comet may have passed as close as 0.03 au (3.2 million miles; 5.1 million kilometres) from Earth, by far its closest approach.[73][63] Its tail may have stretched 60 degrees across the sky. It was recorded by astronomers in China, Japan, Germany, the Byzantine Empire, and the Middle East;[62] Emperor Louis the Pious observed this appearance and devoted himself to prayer and penance, fearing that «by this token a change in the realm and the death of a prince are made known.»[74] In 912, Halley is recorded in the Annals of Ulster, which state «A dark and rainy year. A comet appeared.»[75]

1066[edit]

Halley’s Comet seen from London on 6 May 1066 as simulated by Stellarium. The Moon, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are also visible.

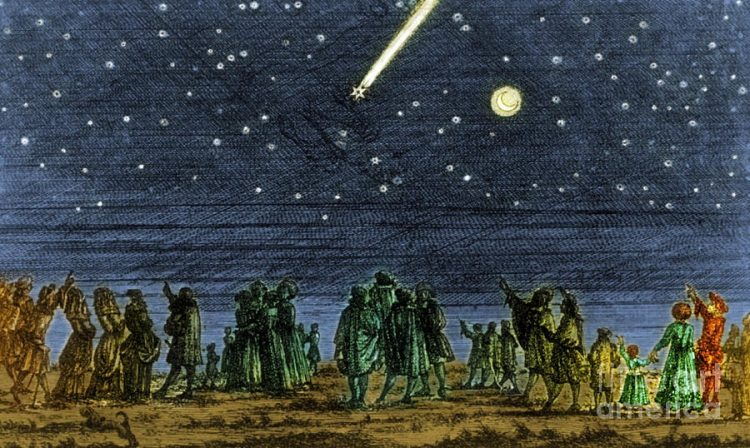

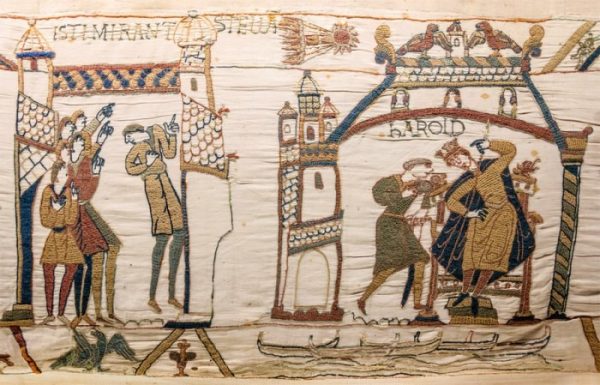

In 1066, the comet was seen in England and thought to be an omen: later that year Harold II of England died at the Battle of Hastings and William the Conqueror claimed the throne. The comet is represented on the Bayeux Tapestry and described in the tituli as a star. Surviving accounts from the period describe it as appearing to be four times the size of Venus, and shining with a light equal to a quarter of that of the Moon. Halley came within 0.10 au of Earth at that time.[63]

This appearance of the comet is also noted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Eilmer of Malmesbury may have seen Halley in 989 and 1066, as recorded by William of Malmesbury:

«Not long after, a comet, portending (they say) a change in governments, appeared, trailing its long flaming hair through the empty sky: concerning which there was a fine saying of a monk of our monastery called Æthelmær. Crouching in terror at the sight of the gleaming star, ‘You’ve come, have you?’, he said. ‘You’ve come, you source of tears to many mothers. It is long since I saw you; but as I see you now you are much more terrible, for I see you brandishing the downfall of my country.’»[76]

The Irish Annals of the Four Masters recorded the comet as «A star [that] appeared on the seventh of the Calends of May, on Tuesday after Little Easter, than whose light the brilliance or light of The Moon was not greater; and it was visible to all in this manner till the end of four nights afterwards.»[75] Chaco Native Americans in New Mexico may have recorded the 1066 apparition in their petroglyphs.[77]

The Italo-Byzantine chronicle of Lupus the Protospatharios mentions that a «comet-star» appeared in the sky in the year 1067 (the chronicle is erroneous, as the event occurred in 1066, and by Robert he means William).

The Emperor Constantine Ducas died in the month of May, and his son Michael received the Empire. And in this year there appeared a comet star, and the Norman count Robert [sic] fought a battle with Harold, King of the English, and Robert was victorious and became king over the people of the English.[78]

1145–1378[edit]

The Adoration of the Magi (circa 1305) by Giotto, who purportedly modelled the star of Bethlehem on Halley, which had been sighted 4 years before that painting.

The 1145 apparition was recorded by the monk Eadwine. The 1986 apparition exhibited a fan tail similar to Eadwine’s drawing.[72] Some claim that Genghis Khan was inspired to turn his conquests toward Europe by the 1222 apparition.[79] The 1301 apparition may have been seen by the artist Giotto di Bondone, who represented the Star of Bethlehem as a fire-colored comet in the Nativity section of his Arena Chapel cycle, completed in 1305.[72] Its 1378 appearance is recorded in the Annales Mediolanenses[80] as well as in East Asian sources.[81]

1456[edit]

In 1456, the year of Halley’s next apparition, the Ottoman Empire invaded the Kingdom of Hungary, culminating in the siege of Belgrade in July of that year. In a papal bull, Pope Callixtus III ordered special prayers be said for the city’s protection. In 1470, the humanist scholar Bartolomeo Platina wrote in his Lives of the Popes that,[82]

A hairy and fiery star having then made its appearance for several days, the mathematicians declared that there would follow grievous pestilence, dearth and some great calamity. Calixtus, to avert the wrath of God, ordered supplications that if evils were impending for the human race He would turn all upon the Turks, the enemies of the Christian name. He likewise ordered, to move God by continual entreaty, that notice should be given by the bells to call the faithful at midday to aid by their prayers those engaged in battle with the Turk.

Platina’s account is not mentioned in official records. In the 18th century, a Frenchman further embellished the story, in anger at the Church, by claiming that the Pope had «excommunicated» the comet, though this story was most likely his own invention.[83]

Halley’s apparition of 1456 was also witnessed in Kashmir and depicted in great detail by Śrīvara, a Sanskrit poet and biographer to the Sultans of Kashmir. He read the apparition as a cometary portent of doom foreshadowing the imminent fall of Sultan Zayn al-Abidin (AD 1418/1420–1470).[84]

After witnessing a bright light in the sky which most historians have identified as Halley’s Comet, Zara Yaqob, Emperor of Ethiopia from 1434 to 1468, founded the city of Debre Berhan (tr. City of Light) and made it his capital for the remainder of his reign.[85]

1531[edit]

In the Sikh scriptures of the Guru Granth Sahib, the founder of the faith Guru Nanak makes reference to «a long star that has risen» at Ang 1110, and it is believed by some Sikh scholars to be a reference to Halley’s appearance in 1531.[86]

1531–1759[edit]

I am more and more confirmed that we have seen that Comett now three times, since ye Yeare 1531

Halley, 1695[87]

Halley’s periodic returns have been subject to scientific investigation since the 16th century. The three apparitions from 1531 to 1682 were noted by Edmond Halley, enabling him to predict it would return.[88] One key breakthrough occurred when Halley talked with Newton about his ideas of the laws of motion. Newton also helped Halley get Flamsteed’s data on the 1682 apparition.[87] By studying data on the 1531, 1607, and 1682 comets, he came to the conclusion these were the same comet, and presented his findings in 1696.[87]

One difficulty was accounting for variations in the comet’s orbital period, which was over a year longer between 1531 and 1607 than it was between 1607 and 1682.[89] Newton had theorized that such delays were caused by the gravity of other comets, but Halley found that Jupiter and Saturn would cause the appropriate delays.[89] In the decades that followed, more refined mathematics would be worked on, notable by Paris Observatory; the work on Halley also provided a boost to Newton and Kepler’s rules for celestial motions.[87] (See also #Computation of orbit)

| 1682 | 1759 | 1835 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

1835[edit]

An 1835 watercolour painting depicting observation of the 1835 apparition

At Markree Observatory in Ireland, a E. J. Cooper used a Cauchoix of Paris lens telescope with an aperture of 340 millimetres (13.3 in) to sketch Halley’s comet in 1835.[90]

The comet was also sketched by F.W. Bessel.[91] Streams of vapour observed during the comet’s 1835 apparition prompted astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel to propose that the jet forces of evaporating material could be great enough to significantly alter a comet’s orbit.[92]

An interview in 1910, of someone who was a teenager at the time of the 1835 apparition had this to say:[93]

When the comet was first seen, it appeared in the western sky, its head toward the north and tail towards the south, about horizontal and considerably above the horizon and quite a distance south of the Sun. It could be plainly seen directly after sunset every day, and was visible for a long time, perhaps a month …

They go on to describe the comet’s tail as being more broad and not as long as the comet of 1843 they had also witnessed.[93]

Famous astronomers across the world made observations starting August 1835, including Struve at Dorpat observatory, and Sir John Herschel, who made of observations from the Cape of Good Hope.[94] In the United States telescopic observations were made from Yale College.[94] The new observations helped confirm early appearances of this comet including its 1456 and 1378 apparitions.[94]

At Yale College in Connecticut, the comet was first reported on 31 August 1835 by astronomers D. Olmstead and E. Loomis.[95] In Canada reports were made from Newfoundland and also Quebec.[95] Reports came in from all over by later 1835, and often reported in newspapers of this time in Canada.[95]

Several accounts of the 1835 apparition were made by observers who survived until the 1910 return, where increased interest in the comet led to their being interviewed.[95]

Astrophotography was not known to have been attempted until 1839, as photography was still being invented in the 1830s, too late to photograph the apparition of 1P/Halley in 1835.[96]

The time to Halley’s return in 1910 would be only 74.42 years, one of the shortest known periods of its return, which is calculated to be as long as 79 years owing to the effects of the planets.[97]

At Paris Observatory Halley’s Comet 1835 apparition was observed with a Lerebours telescope of 24.4 cm (9.6 in) aperture by the astronomer François Arago.[98] Arago recorded polimetric observations of Halley, and suggested that the tail might be sunlight reflecting off a sparsely distributed material; he had earlier made similar observations of Comet Tralles of 1819.[99]

1910[edit]

A photograph of Halley’s Comet taken during its 1910 approach

Halley in April 1910, from Harvard’s Southern Hemisphere Station, taken with an 8-inch Bache Doublet

Infographic from the January 1910 issue of Popular Science Monthly magazine, showing how Halley’s tail points away from the Sun as it passes through the inner Solar System

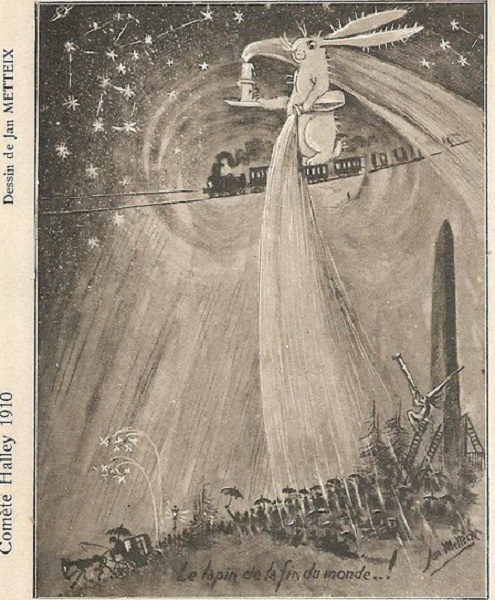

The 1910 approach, which came into naked-eye view around 10 April[63] and came to perihelion on 20 April,[63] was notable for several reasons: it was the first approach of which photographs exist, and the first for which spectroscopic data were obtained.[15] Furthermore, the comet made a relatively close approach of 0.15 au,[63] making it a spectacular sight. Indeed, on 19 May, Earth actually passed through the tail of the comet.[100][101] One of the substances discovered in the tail by spectroscopic analysis was the toxic gas cyanogen,[102] which led astronomer Camille Flammarion to claim that, when Earth passed through the tail, the gas «would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet.»[103] His pronouncement led to panicked buying of gas masks and quack «anti-comet pills» and «anti-comet umbrellas» by the public.[104] In reality, as other astronomers were quick to point out, the gas is so diffused that the world suffered no ill effects from the passage through the tail.[103]

The comet added to the unrest in China on the eve of the Xinhai Revolution that would end the last dynasty in 1911. As James Hutson, a missionary in Sichuan Province at the time, recorded,

The people believe that it indicates calamity such as war, fire, pestilence, and a change of dynasty. In some places on certain days the doors were unopened for half a day, no water was carried and many did not even drink water as it was rumoured that pestilential vapour was being poured down upon the earth from the comet.»[105]

The 1910 visitation is also recorded as being the travelling companion of Hedley Churchward, the first known English Muslim to make the Haj pilgrimage to Mecca. However, his explanation of its scientific predictability did not meet with favour in the Holy City.[106]

The comet was used in an advertising campaign of Le Bon Marché, a well-known department store in Paris.[107]

The comet was also fertile ground for hoaxes. One that reached major newspapers claimed that the Sacred Followers, a supposed Oklahoma religious group, attempted to sacrifice a virgin to ward off the impending disaster, but were stopped by the police.[108]

American satirist and writer Mark Twain was born on 30 November 1835, exactly two weeks after the comet’s perihelion. In his autobiography, published in 1909, he said,

I came in with Halley’s comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’[109][110]

Twain died on 21 April 1910, the day following the comet’s subsequent perihelion.[111] The 1985 fantasy film The Adventures of Mark Twain was inspired by the quotation.

Halley’s 1910 apparition is distinct from the Great Daylight Comet of 1910, which surpassed Halley in brilliance and was actually visible in broad daylight for a short period, approximately four months before Halley made its appearance.[112][113]

1986[edit]

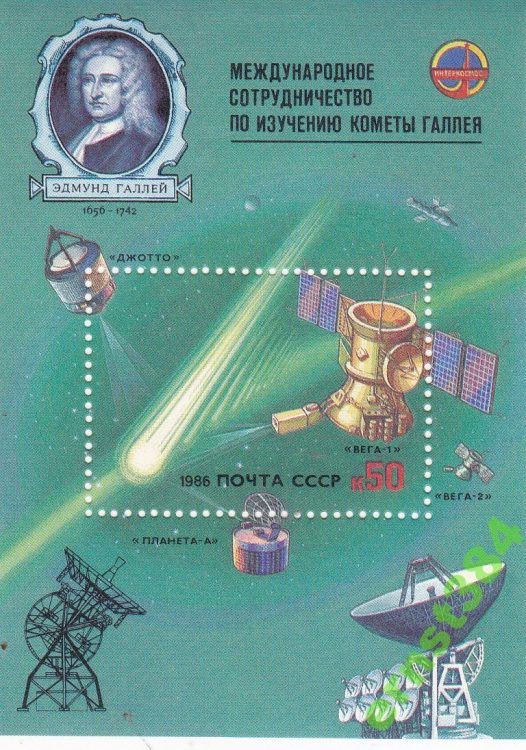

1986 USSR miniature sheet, featuring Edmond Halley, Comet Halley, Vega 1, Vega 2, Giotto, Suisei (Planet-A)

Daily motion across sky during the 1986 passage of Halley’s Comet

Animation of 1P/Halley orbit — 1986 apparition

1P/Halley ·

Earth ·

Sun

The 1986 apparition of Halley’s Comet was the least favourable on record. In February 1986, the comet and the Earth were on opposite sides of the Sun, creating the worst possible viewing circumstances for Earth observers during the previous 2,000 years.[114] Halley’s closest approach was 0.42 au.[115] Additionally, increased light pollution from urbanization caused many people to fail in attempts to see the comet. With the help of binoculars, observation from areas outside cities was more successful.[116] Further, the comet appeared brightest when it was almost invisible from the northern hemisphere in March and April 1986,[117] with best opportunities occurring when the comet could be sighted close to the horizon at dawn and dusk, if not obscured by clouds.

The approach of the comet was first detected by astronomers David C. Jewitt and G. Edward Danielson on 16 October 1982 using the 5.1 m Hale telescope at Mount Palomar and a CCD camera.[118]

The first visual observance of the comet on its 1986 return was by an amateur astronomer, Stephen James O’Meara, on 24 January 1985. O’Meara used a home-built 610-millimetre (24 in) telescope on top of Mauna Kea to detect the magnitude 19.6 comet.[119] The first to observe Halley’s Comet with the naked eye during its 1986 apparition were Stephen Edberg (then serving as the coordinator for amateur observations at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory) and Charles Morris on 8 November 1985.[120][121]

Although the comet’s retrograde orbit and high inclination made it difficult to send a space probe to it,[122] the 1986 apparition gave scientists the opportunity to study the comet closely and several probes were launched to do so. The Soviet Vega 1 probe began returning images of Halley on 4 March 1986, captured the first-ever image of its nucleus,[16] and made its flyby on 6 March. It was followed by the Vega 2 probe, making its flyby on 9 March. On 14 March, the Giotto space probe, launched by the European Space Agency, made the closest pass of the comet’s nucleus.[16] There also were two Japanese probes, Suisei and Sakigake. Unofficially, the numerous probes became known as the Halley Armada.[123]

Based on data retrieved by the largest ultraviolet space telescope of the time, Astron, during its Halley’s Comet observations in December 1985, a group of Soviet scientists developed a model of the comet’s coma.[124] The comet also was observed from space by the International Cometary Explorer (ICE). Originally named International Sun-Earth Explorer 3, the probe was renamed and freed from its L1 Lagrangian point location in Earth’s orbit in order to intercept comets 21P/Giacobini-Zinner and Halley.[125] ICE flew about 40.2 million km (25 million mi) from Halley’s Comet on 28 March 1986.[126][127]

Two Space Shuttle missions—the STS-51-L and the STS-61-E—had been scheduled to observe Halley’s Comet from low Earth orbit. The STS-51-L mission carried the Shuttle-Pointed Tool for Astronomy (SPARTAN-203) satellite, also called the Halley’s Comet Experiment Deployable (HCED).[128] The ill-fated mission was ended by the Challenger disaster.[129] Scheduled for March 1986, STS-61-E was a Columbia mission carrying the ASTRO-1 platform to study the comet.[130] Owing to the suspension of the American human spaceflight program after the Challenger explosion, the mission was canceled and ASTRO-1 would not fly until late 1990 on STS-35.[131]

After 1986[edit]

Halley’s Comet observed in 2003 at 28 au from the Sun

On 12 February 1991, at a distance of 14.4 au (2.15×109 km) from the Sun, Halley displayed an outburst that lasted for several months, releasing a cloud of dust 300,000 km (190,000 mi) across.[49] The outburst likely started in December 1990, and then the comet brightened from magnitude 24.3 to magnitude 18.9.[132] Halley was most recently observed in 2003 by three of the Very Large Telescopes at Paranal, Chile, when Halley’s magnitude was 28.2. The telescopes observed Halley, at the faintest and farthest any comet has ever been imaged, in order to verify a method for finding very faint trans-Neptunian objects.[12] Astronomers are now able to observe the comet at any point in its orbit.[12]

On 9 December 2023, Halley’s Comet will reach the farthest and slowest point in its orbit from the Sun when it will be traveling at 0.91 km/s (2,000 mph) with respect to the Sun.[1][2]

2061[edit]

Animation of 1P/Halley orbit — 2061 apparition

Sun ·

Venus ·

Earth ·

Jupiter ·

1P/Halley

The next perihelion of Halley’s Comet is 28 July 2061,[3] when it will be better positioned for observation than during the 1985–1986 apparition, as it will be on the same side of the Sun as Earth.[36] The closest approach to Earth will be one day after perihelion.[4] It is expected to have an apparent magnitude of −0.3, compared with only +2.1 for the 1986 apparition.[133] On 9 September 2060, Halley will pass within 0.98 au (147,000,000 km) of Jupiter, and then on 20 August 2061 will pass within 0.0543 au (8,120,000 km) of Venus.[4]

2134[edit]

Halley will come to perihelion on 27 March 2134.[134] Then on 7 May 2134, Halley will pass within 0.092 au (13,800,000 km) of Earth.[4] Its apparent magnitude is expected to be −2.0.[133]

Apparitions[edit]

Halley’s calculations enabled the comet’s earlier appearances to be found in the historical record. The following table sets out the astronomical designations for every apparition of Halley’s Comet from 240 BC, the earliest documented widespread sighting.[4][135] For example, «1P/1982 U1, 1986 III, 1982i» indicates that for the perihelion in 1986, Halley was the first period comet known (designated 1P) and this apparition was the first seen in half-month U (the second half of October)[136] in 1982 (giving 1P/1982 U1); it was the third comet past perihelion in 1986 (1986 III); and it was the ninth comet spotted in 1982 (provisional designation 1982i). The perihelion dates of each apparition are shown.[137] The perihelion dates farther from the present are approximate, mainly because of uncertainties in the modelling of non-gravitational effects. Perihelion dates of 1531 and earlier are in the Julian calendar, while perihelion dates 1607 and after are in the Gregorian calendar.[138]

Halley’s Comet is visible from Earth every 74–79 years.[4][62][36]

| Designation | Year BC/AD | Gap (years) | Date of perihelion[5] | Visible duration | Earth approach[63] | Description[139] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1P/−239 K1, −239 | 240 BC | – | 25 May | 15–25 May | First confirmed sighting. | |

| 1P/−163 U1, −163 | 164 BC | 76 | 12 Nov | Seen by Babylonians. | ||

| 1P/−86 Q1, −86 | 87 BC | 77 | 6 August | 6–19 August | Seen by the Babylonians and Chinese. | |

| 1P/−11 Q1, −11 | 12 BC | 75 | 10 October | August – 10 October | 0.16 au | Watched by Chinese for two months. |

| 1P/66 B1, 66 | 66 | 78 | 25 January | 25–26 January | May be the comet described in Josephus’s The Jewish War as «A comet of the kind called Xiphias, because their tails appear to represent the blade of a sword» that supposedly heralded the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD.[64] | |

| 1P/141 F1, 141 | 141 | 75 | 22 March | 22–25 March | Described by the Chinese as bluish-white in colour. Described in Tamil literature and death of Chera (Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai) king after appearance of comet.[140] | |

| 1P/218 H1, 218 | 218 | 77 | 17 May | 6 April – 17 May | Described by the Roman historian Dion Cassius as «a very fearful star». | |

| 1P/295 J1, 295 | 295 | 77 | 20 April | 7–20 April | Seen in China, but not spectacular. | |

| 1P/374 E1, 374 | 374 | 79 | 16 February | 13–16 February | 0.09 au | Comet passed 13.5 million kilometres from Earth. |

| 1P/451 L1, 451 | 451 | 77 | 28 June | 28 June – 3 July | Appeared before the defeat of Attila the Hun at the Battle of Chalons. The 451AD orbital period was 79.29 years.[5] | |

| 1P/530 Q1, 530 | 530 | 79 | 27 September | 27 September – 15 November | Noted in China and Europe, but not spectacular. | |

| 1P/607 H1, 607 | 607 | 77 | 15 March | 15–26 March | 0.09 au | Comet passed 13.5 million kilometres from Earth. |

| 1P/684 R1, 684 | 684 | 77 | 2 October | 2 October – 26 November | First known Japanese records of the comet. Seen in Europe and depicted 800 years later in the Nuremberg Chronicle. Attempts have been made to connect an ancient Maya depiction of God L to the event.[141] | |

| 1P/760 K1, 760 | 760 | 76 | 20 May | 20 May – 10 June | Seen in China, at the same time as another comet. | |

| 1P/837 F1, 837 | 837 | 77 | 28 February | 25–28 February | 0.033 au[73] | Closest-ever approach to the Earth (5 million km). Tail stretched halfway across the sky. Appeared as bright as Venus. |

| 1P/912 J1, 912 | 912 | 75 | 18 July | 18–27 July | Seen briefly in China and Japan. | |

| 1P/989 N1, 989 | 989 | 77 | 5 September | 2–5 September | Seen in China, Japan, and (possibly) Korea. | |

| 1P/1066 G1, 1066 | 1066 | 77 | 20 March | January – 25 March | 0.10 au | Seen for over two months in China. Recorded in England and depicted on the later Bayeux tapestry which portrayed the events of that year. |

| 1P/1145 G1, 1145 | 1145 | 79 | 18 April | 15–19 April | Depicted on the Eadwine Psalter, with the remark that such «hairy stars» appeared rarely, «and then as a portent». | |

| 1P/1222 R1, 1222 | 1222 | 77 | 28 September | 10–28 September | Described by Japanese astronomers as being «as large as the half Moon . . . Its colour was white but its rays were red». | |

| 1P/1301 R1, 1301 | 1301 | 79 | 25 October | 22–31 October | Seen by Giotto di Bondone and included in his painting The Adoration of the Magi. Chinese astronomers compared its brilliance to that of the first-magnitude star Procyon. | |

| 1P/1378 S1, 1378 | 1378 | 77 | 10 November | 9–14 November | Passed within 10 degrees of the north celestial pole, more northerly than at any time during the past 2000 years. This is the last appearance of the comet for which Oriental records are better than Western ones. | |

| 1P/1456 K1, 1456 | 1456 | 78 | 9 June | 8 January – 9 June | Observed in Italy by Paolo Toscanelli, who said its head was «as large as the eye of an ox», with a tail «fan-shaped like that of a peacock». Arabs said the tail resembled a Turkish scimitar. Turkish forces attacked Belgrade. | |

| 1P/1531 P1, 1531 | 1531 | 75 | 26 August | 26 August | Seen by Peter Apian, who noted that its tail always pointed away from the Sun. This sighting was included in Halley’s table. | |

| 1P/1607 S1, 1607 | 1607 | 76 | 27 October | 27 October | Seen by Johannes Kepler. This sighting was included in Halley’s table. | |

| 1P/1682 Q1, 1682 | 1682 | 75 | 15 September | 15 September | Seen by Edmond Halley at Islington. | |

| 1P/1758 Y1, 1759 I | 1758 | 76 | 13 March | 13 March – 25 December | Return predicted by Halley. First seen by Johann Palitzsch on 1758 December 25. | |

| 1P/1835 P1, 1835 III | 1835 | 77 | 16 November | August – 16 November | First seen at the Observatory of the Roman College in August.[142] Studied by John Herschel at the Cape of Good Hope. | |

| 1P/1909 R1, 1910 II, 1909c | 1910 | 75 | 20 April | 20 April – 20 May | 0.151 au[4] | Photographed for the first time. Earth passed through the comet’s tail on 20 May. |

| 1P/1982 U1, 1986 III, 1982i | 1986 | 76 | 9 February | 9 February | 0.417 au | Reached perihelion on 9 February, closest to Earth (63 million km) on 10 April. Nucleus photographed by the European space probe Giotto and the Soviet probes Vega 1 and 2. |

| 2061 | 75 | 28 July | 28 July 2061[3] | 0.477 au | Next return with perihelion on 28 July 2061[3] and Earth approach one day later on 29 July 2061[4] | |

| 2134 | 73 | 27 March | 27 March 2134[134] | 0.092 au[4] | Subsequent return with perihelion on 27 March 2134 and Earth approach on 7 May 2134 | |

| 2209 | 75 | 3 February | 3 February 2209[143] | 0.515 au[143] | Best-fit for February 2209 perihelion passage and April Earth approach |

See also[edit]

- List of Halley-type comets

- Halley’s Comet in fiction

- Kepler orbit

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «Horizons Batch for 1P/Halley (90000030) on 2023-Dec-09» (Aphelion occurs when rdot flips from positive to negative). JPL Horizons. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022. (JPL#73 Soln.date: 2022-Jun-07)

- ^ a b DNews (3 September 2013). «Let’s Plan For a Rendezvous With Halley’s Comet». Seeker. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f «Horizons Batch for 1P/Halley (90000030) on 2061-Jul-28» (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive @ 2061-Jul-28 17:20 UT). JPL Horizons. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022. (JPL#73 Soln.date: 2022-Jun-07)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k «JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 1P/Halley» (11 January 1994 last obs). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d «1P/Halley Orbit». Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022. (epoch 451 is 79.29 years)

- ^ a b c «What Have We Learned About Halley’s Comet?». Astronomical Society of the Pacific (No. 6 – Fall 1986). 1986. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ a b Cevolani, Giordano; Bortolotti, Giuseppe; Hajduk, Anton (1987). «Halley, comet’s mass loss and age». Il Nuovo Cimento C. Società Italiana di Fisica [Italian Physical Society]. 10 (5): 587–591. Bibcode:1987NCimC..10..587C. doi:10.1007/BF02507255. S2CID 120603847.

- ^ a b Sagdeev, Roald Z.; Elyasberg, Pavel E.; Moroz, Vasily I. (1988). «Is the nucleus of Comet Halley a low density body?». Nature. 331 (6153): 240–242. Bibcode:1988Natur.331..240S. doi:10.1038/331240a0. S2CID 4335780.

- ^ Peale, Stanton J. (1989). «On the density of Halley’s comet». Icarus. 82 (1): 36–49. Bibcode:1989Icar…82…36P. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90021-3.

densities obtained by this procedure are in reasonable agreement with intuitive expectations of densities near 1 g/cm3, the uncertainties in several parameters and assumptions expand the error bars so far as to make the constraints on the density uniformative … suggestion that cometary nuclei tend to by very fluffy, … should not yet be adopted as a paradigm of cometary physics.

- ^ Peale, Stanton J.; Lissauer, Jack J. (1989). «Rotation of Halley’s Comet». Icarus. 79 (2): 396–430. Bibcode:1989Icar…79..396P. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90085-7.

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy (29 November 2001). «Comet Borrelly Puzzle: Darkest Object in the Solar System». Space.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ a b c «New Image of Comet Halley in the Cold». European Southern Observatory. 1 September 2003. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Delehanty, Marc. «Comets, awesome celestial objects». AstronomyToday. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Halley, Edmund (1705). A synopsis of the astronomy of comets. Oxford: John Senex. Retrieved 16 June 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e Mendis, D. Asoka (1988). «A Postencounter view of comets». Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 26 (1): 11–49. Bibcode:1988ARA&A..26…11M. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.26.090188.000303.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Keller, Horst Uwe; Britt, Daniel; Buratti, Bonnie J.; Thomas, Nicolas (2005). «In Situ Observations of Cometary Nuclei» (PDF). In Festou, Michel; Keller, Horst Uwe; Weaver, Harold A. (eds.). Comets II. University of Arizona Press. pp. 211–222. ISBN 978-0-8165-2450-1.

- ^ «Halley». Merriam–Webster Online. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (1985). «Saying Hallo to Halley». Revised extracts from «A Comet Called Halley» by Ian Ridpath, published by Cambridge University Press in 1985. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ That is, with the vowel of hall and in some accents homophonous withholly.

- ^ «New York Times Science Q&A». The New York Times. 14 May 1985. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, pp. 14, 25

- ^ Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, p. 35

- ^ a b Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, p. 76

- ^ a b Ley, Willy (October 1967). «The Worst of All the Comets». For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 96–105.

- ^ Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, p. 78

- ^ Yeomans, Donald Keith; Rahe, Jürgen; Freitag, Ruth S. (1986). «The History of Comet Halley». Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 80: 81. Bibcode:1986JRASC..80…62Y.

- ^ Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, p. 80

- ^ Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, p. 86

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Druyan, Ann; Comet, p. 74

- ^ Lancaster-Brown, Peter; Halley & His Comet, pp. 84–85

- ^ a b c d Hughes, David W.; et al. (1987). «The History of Halley’s Comet». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 323 (1572): 349–367. Bibcode:1987RSPTA.323..349H. doi:10.1098/rsta.1987.0091. JSTOR 37959. S2CID 123592786.

- ^ Brodetsky, Selig. «Astronomy in the Babylonian Talmud». Jewish Review. 1911: 60.

- ^ «Tractate Horioth chapter 3».

- ^ Rayner, John D. (1998). A Jewish Understanding of the World. Berghahn Books. pp. 108–111. ISBN 1-57181-973-8.

- ^ Stephenson, F. Richard; Yau, Kevin K. C., «Oriental tales of Halley’s Comet», New Scientist, vol. 103, no. 1423, pp. 30–32, 27 September 1984 ISSN 0262-4079

- ^ a b c Yeomans, Donald Keith; Rahe, Jürgen; Freitag, Ruth S. (1986). «The History of Comet Halley». Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 80: 70. Bibcode:1986JRASC..80…62Y.

- ^ Nakano, Syuichi (2001). «OAA computing sectioncircular». Oriental Astronomical Association. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- ^ «Meteor Streams». Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Mitra, Umasankar (1987). «An Investigation Into the Association Between Eta-Aquarid Meteor Shower and Halley’s Comet». Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India. 15: 23. Bibcode:1987BASI…15…23M.

- ^ a b c

Morbidelli, Alessandro (2005). «Origin and dynamical evolution of comets and their reservoirs». arXiv:astro-ph/0512256. - ^ a b c d Jewitt, David C. (2002). «From Kuiper Belt Object to Cometary Nucleus: The Missing Ultrared Matter». The Astronomical Journal. 123 (2): 1039–49. Bibcode:2002AJ….123.1039J. doi:10.1086/338692. S2CID 122240711.

- ^ Fernández, Yanga R. (28 July 2015). «List of Jupiter-Family and Halley-Family Comets». University of Central Florida: Physics. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Gladman, Brett J.; et al. (2009). «Discovery of the first retrograde transneptunian object». The Astrophysical Journal. 697 (2): L91–L94. Bibcode:2009ApJ…697L..91G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/2/L91.

- ^ a b Olsson-Steel, Duncan I. (1987). «The dynamical lifetime of comet P/Halley». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 187 (1–2): 909–912. Bibcode:1987A&A…187..909O.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald Keith (1991). Comets: A Chronological History of Observation, Science, Myth, and Folklore. Wiley and Sons. pp. 260–261. ISBN 0-471-61011-9.

- ^ Chirikov, Boris V.; Vecheslavov, Vitold V. (1989). «Chaotic dynamics of comet Halley» (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 221 (1): 146–154. Bibcode:1989A&A…221..146C.

- ^ Lages, José; Shepelyansky, Dima L.; Shevchenko, Ivan I. (2018). «Kepler map». Scholarpedia. 13 (2): 33238. Bibcode:2018SchpJ..1333238L. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.33238.

- ^ Williams, Matt (12 June 2015). «WHAT IS HALLEY’S COMET?». Universe today.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brandt, John C. «McGraw−Hill AccessScience: Halley’s Comet». McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ Crovisier, Jacques; Encrenaz, Thérèse (2000). Comet Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64591-1.

- ^ Woods, Thomas N.; Feldman, Paul D.; Dymond, Kenneth F.; Sahnow, David J. (1986). «Rocket ultraviolet spectroscopy of comet Halley and abundance of carbon monoxide and carbon». Nature. 324 (6096): 436–438. Bibcode:1986Natur.324..436W. doi:10.1038/324436a0. S2CID 4333809.

- ^ Chyba, Christopher F.; Sagan, Carl (1987). «Infrared emission by organic grains in the coma of comet Halley». Nature. 330 (6146): 350–353. Bibcode:1987Natur.330..350C. doi:10.1038/330350a0. S2CID 4351413.

- ^ «Giotto:Halley». European Space Agency. 2006. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ Weaver, Harold A.; et al. (1997). «The Activity and Size of the Nucleus of Comet Hale–Bopp (C/1995 O1)». Science. 275 (5308): 1900–1904. Bibcode:1997Sci…275.1900W. doi:10.1126/science.275.5308.1900. PMID 9072959. S2CID 25489175.

- ^ «Voyages to Comets». NASA. 2005. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (10 September 2010). «Halley’s comet ‘was spotted by the ancient Greeks’«. BBC News.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald Keith (1991). Comets: A Chronological History of Observation, Science, Myth, and Folklore. Wiley and Sons. p. 4. ISBN 0-471-61011-9.

- ^ Vilyev, Mikhail Anatolyevich; 1917; «Investigations on the Theory of Motion of Halley’s Comet», cited by Dubyago, Alexander Dmitriyevich; 1961; «The Determination of Orbits», Ch. 1; The Macmillan Company, New York

- ^ a b Kronk, Gary W. (1999). Cometography, vol. 1: Ancient-1799. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-521-58504-0.

- ^ Stephenson, F. Richard; Yau, Kevin K. C.; Hunger, Hermann (1985). «Records of Halley’s Comet on Babylonian tablets». Nature. 314 (6012): 587–592. Bibcode:1985Natur.314..587S. doi:10.1038/314587a0. S2CID 33251962.

- ^ Gurzadyan, Vahe G.; Vardanyan, Ruben (4 August 2004). «Halley’s Comet of 87 BC on the coins of Armenian king Tigranes?». Astronomy & Geophysics. 45 (4): 4.06. arXiv:physics/0405073. Bibcode:2004A&G….45d…6G. doi:10.1046/j.1468-4004.2003.45406.x. S2CID 119357985.

- ^ a b c Kronk, Gary W. «1P/Halley». cometography.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yeomans, Donald Keith (1998). «Great Comets in History». Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ a b Chambers, George F. (1909). The Story of the Comets. The Clarenden Press. p. 123.

- ^ Humphreys, Colin (1995). «The Star of Bethlehem». Science and Christian Belief. 5: 83–101.

- ^ «Horayot 10a:19». www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Ne’eman, Yuval (1983). «Astronomy in Israel: From Og’s Circle to the Wise Observatory». Tel-Aviv University. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Ravené, Gustave (1897). «The Appearance of Halley’s Comet in AD 141». The Observatory. 20: 203–205. Bibcode:1897Obs….20..203R.

- ^ Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai

- ^ O’Toole, Thomas (1985). «A Comet Lights the Imagination». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «The History Of Halley’s Comet».

- ^ a b c Olson, Roberta J.; Pasachoff, Jay M. (1986). «New information on Comet Halley as depicted by Giotto di Bondone and other Western artists». In ESA, Proceedings of the 20th ESLAB Symposium on the Exploration of Halley’s Comet. 3: 201–213. Bibcode:1986ESASP.250c.201O.

- ^ a b «Horizons Batch for 1P/Halley (90000015) on 837AD-Apr-10» (Earth approach occurs when deldot flips from negative to positive @ 837-Apr-10 12:13). JPL Horizons. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022. (SAO/837)

- ^ Son of Charlemagne: A Contemporary Life of Louis the Pious. Translated by Cabaniss, Allen. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 1961. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8156-2031-0.

- ^ a b «The Annals of Ulster AD 431–1201». Corpus of Electronic Texts. University College Cork. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ William of Malmesbury; Gesta regum Anglorum / The history of the English Kings, edited and translated by Mynors, R. A. B.; Thomson, R. M.; and Winterbottom, M.; 2 vols., Oxford Medieval Texts (1998–99), p. 121

- ^ Brazil, Ben (18 September 2005). «Chaco Canyon mystery tour». The LA Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ The Chronicle of Lupus Protospatharios.

- ^ Johnson, George (28 March 1997). «Comets Breed Fear, Fascination and Web Sites». The New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, ed. Ludovico Antonio Muratori (Milan, 1730) v. 16 col. 770.

- ^ Kronk, Gary W. (1999). Cometography, vol. 1: Ancient-1799. Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0-521-58504-0.

- ^ Emerson, Edwin. Comet lore, Halley’s comet in history and astronomy. New York, Printed by the Schilling press. p. 74. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Botley, Cicely M. (1971). «The Legend of 1P/Halley 1456». The Observatory. 91: 125–126. Bibcode:1971Obs….91..125B.

- ^ Slaje, Walter; inter alia, realia: «An Apparition of Halley’s Comet in Kashmir observed by Śrīvara in AD 1456» in Steiner, Roland (ed.); Highland Philology: Results of a Text-Related Kashmir Panel at the 31st DOT, Marburg 2010, Studia Indologica Universitatis Halensis, 4, Halle 2012: 33–48

- ^ The founding of Debre Berhan is described in the Ethiopian Royal Chronicles (Pankhurst, Richard; Oxford University Press, Addis Ababa, 1967, pp. 36–38).

- ^ Kapoor, R.C. (10 July 2017). «Records of sighting of Halley’s Comet in the 1531 apparition and an eclipse in Guru Nanak’s references». Current Science. 113 (1): 173–179. JSTOR 26163925.

- ^ a b c d Broughton, P. (1985). «The First Predicted Return of Comet Halley». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 16 (2): 123–132. Bibcode:1985JHA….16..123B. doi:10.1177/002182868501600203. S2CID 118670662.

- ^ Grier, David Alan (2005). «The First Anticipated Return: Halley’s Comet 1758». When Computers Were Human. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 11–25. ISBN 0-691-09157-9.

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl; Druyan, Ann; Comet, p. 57

- ^ «History of the Cauchoix objective«.

- ^ «Comet Halley in 1835». Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Druyan, Ann; Comet, p. 117

- ^ a b Todd, William G. (1910). «Saw Halley’s Comet in 1835». Popular Astronomy. 18: 127. Bibcode:1910PA…..18..127T.

- ^ a b c Lynn, W. T. (1909). «Halley’s Comet in 1835». The Observatory. 32: 175–177. Bibcode:1909Obs….32..175L.

- ^ a b c d Smith, J. A. (1986). «Halley’s Comet: Canadian Observations and Reactions 1835–36 and 1910». Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 80 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:1986JRASC..80….1S.

- ^ «The First Astronomy Photograph In History January 2, 1839». David Reneke | Space and Astronomy News — Space News, Astronomy News, Telescopes, Astrophotography, UFOs. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ «In Depth | 1P/Halley». NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Lequeux, James (8 September 2015). François Arago: A 19th Century French Humanist and Pioneer in Astrophysics. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-20723-0.

- ^ «From François Arago to small bodies exploration: Polarimetry as a tool to reveal properties of thin dust clouds in the Solar system and beyon» (PDF).

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (1985). «Through the comet’s tail». Revised extracts from «A Comet Called Halley» by Ian Ridpath, published by Cambridge University Press in 1985. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Nunnally, Brian (16 May 2011). «This Week in Science History: Halley’s Comet». pfizer: ThinkScience Now. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ anonymous (8 February 1910). «Yerkes Observatory Finds Cyanogen in Spectrum of Halley’s Comet». The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ a b Strauss, Mark (November 2009). «Ten Notable Apocalypses That (Obviously) Didn’t Happen». Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ anonymous (2009). «Interesting Facts About Comets». Universe Today. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ Hutson, James; Chinese Life in the Tibetan Foothills, 1921 (See section: Eclipses and Comets, p. 207)

- ^ From Drury Lane to Mecca. Being an account of the strange life and adventures of Hedley Churchward, Sampson Low, London, 1931

- ^ https://bibnum.obspm.fr/ark:/11287/z750B, digital library of Paris Observatory

- ^ Johnson, George (28 March 1997). «Comets Breed Fear, Fascination and Web Sites». The New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

When Halley’s comet made its appearance in 1910, an Oklahoma religious group, known as the Sacred Followers, tried to sacrifice a virgin to ward off catastrophe. (They were stopped by the police.)

- ^

Paine, Albert Bigelow (1912). Mark Twain, a biography: the personal and literary life of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Harper & Brothers. p. 1511. - ^ Metcalf, Miranda. «Mark Twain’s birthday». Smithsonian Libraries. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ anonymous (1910). «The Death of Mark Twain». Chautauquan. The University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (13 January 2010). «The Great Daylight Comet of 1910». Sky & Telescope Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (1998). «The Bright Comet Chronicles». International Comet Quarterly. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Broughton, R. Peter (1979). «The visibility of Halley’s comet». Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 73: 24–36. Bibcode:1979JRASC..73…24B.

- ^ «Comet Halley Summary». Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 1985. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ «Australian Astronomy: Comets» (PDF). Australian Astronomical Association. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2005. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ «Last Chance For Good Comet-Viewing». Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. 1 April 1986. p. 14. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ «Comet Halley Recovered». European Space Agency. 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ Browne, Malcolm W. (20 August 1985). «Telescope Builders See Halley’s Comet From Vermont Hilltop». The New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2008. (Horizons shows the nucleus @ APmag +20.5; the coma up to APmag +14.3)

- ^ anonymous (12 November 1985). «First Naked-Eye Sighting of Halley’s Comet Reported». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ «First Naked-Eye Sighting of Halley’s Comet Reported». New York Times. 12 November 1985. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ Ley, Willy (September 1968). «Mission to a Comet». For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 101–110.

- ^ «Suisei». Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ Boyarchuk, Alexander A.; Grinin, Vladimir P.; Zvereva, A. M.; Petrov, Peter P.; Sheikhet, A. I. (1986). «A model for the coma of Comet Halley, based on the Astron ultraviolet spectrophotometry». Pis’ma v Astronomicheskii Zhurnal (in Russian). 12: 291–296. Bibcode:1986PAZh…12..696B.

- ^ Murdin, Paul (2000). «International Cometary Explorer (ICE)». Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Institute of Physics Publishing. Bibcode:2000eaa..bookE4650.. doi:10.1888/0333750888/4650. hdl:2060/19920003890. ISBN 0-333-75088-8.

- ^ «In Depth | ISEE-3/ICE». NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration. United States: NASA History Program Office. pp. 149–150. ISBN 9781626830424.

- ^ «Spartan 203 (Spartan Halley, HCED)». space.skyrocket.de. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ «STS-51L». NASA Kennedy Space Center. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Shayler, David J.; Burgess, Colin (2007). «Ending of Eras». NASA’s Scientist-Astronauts. Praxis. pp. 431–476. ISBN 978-0-387-21897-7. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ «STS-35 (38)». NASA. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Prialnik, Dina; Bar-Nun, Akiva (1992). «Crystallization of amorphous ice as the cause of Comet P/Halley’s outburst at 14 AU». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 258 (2): L9–L12. Bibcode:1992A&A…258L…9P.

- ^ a b Odenwald, Sten. «When will Halley’s Comet return?». NASA. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ a b «Horizons Batch for 1P/Halley (90000030) on 2134-Mar-27» (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive). JPL Horizons. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022. (JPL#73 Soln.date: 2022-Jun-07)

- ^ «Comet names and designations». International Comet Quarterly. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Schmude, Richard M. (2010). Comets and How to Observe Them. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4419-5790-0.

- ^ Marsden, Brian G.; Williams, Gareth V. (1996). «Catalogue of Cometary Orbits 1996. 11th edition». Catalogue of Cometary Orbits. International Astronomical Union. Bibcode:1996cco..book…..M.

- ^ Brady, Joseph L. (1982). «Halley’s Comet AD 1986 to 2647 BC». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, University of California. 92: 209. Bibcode:1982JBAA…92..209B.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (1985). «Returns of Halley’s Comet». Revised extracts from «A Comet Called Halley» by Ian Ridpath, published by Cambridge University Press in 1985. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ The poets Kurunkozhiyur Kizhaar and Koodaloor Kizhaar, who were present at the death of the king, state that the death was portended by a falling star (possibly a comet) seven days previous to the occurrence.

- ^ Star Gods of the Maya: Astronomy in Art, Folklore, and Calendars

- ^ Dumouchel, Etienne (1836). «Vermischte Nachrichten». Astronomische Nachrichten. 13 (1): 16.

- ^ a b «Horizons Batch for 1P/Halley (90000030) on 2209-Feb-03 and 2209-Apr-10» (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive). JPL Horizons. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022. (JPL#73 Soln.date: 2022-Jun-07)

Bibliography[edit]

- Gore, Rick (December 1986). «Halley’s Comet ’86». National Geographic. Vol. 170, no. 6. pp. 758–785. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Lancaster-Brown, Peter (1985). Halley & His Comet. Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1447-6.

- Needham, Joseph (1959). «Comets, meteors, and meteorites». Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press. pp. 430–433. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8.

- Sagan, Carl; Druyan, Ann (1985). Comet. Random House. ISBN 0-394-54908-2.

External links[edit]

- Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets (1706 reprint of Halley’s 1705 paper)

- Halley’s nucleus by Giotto spacecraft (ESA link)

- Image of Halley in 1986 by Giotto spacecraft (NASA link)

- cometography.com

- 1P/Halley at CometBase database

- seds.org

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris

- Donald Keith Yeomans, «Great Comets in History»

- A brief history of Halley’s Comet (Ian Ridpath)

- Photographs of 1910 approach taken from the Lick Observatory from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library’s Digital Collections Archived 20 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

| Numbered comets | ||

|---|---|---|

| Previous (periodic comet navigator) |

1P/Halley | Next 2P/Encke |

Halley’s Comet on 8 March 1986 |

|

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Prehistoric (observation) Edmond Halley (recognition of periodicity) |

| Discovery date | 1758 (first predicted perihelion) |

| Orbital characteristics[5] | |

| Epoch 4 August 2061 (2474040.5) | |

| Aphelion | 35.14 au[1] (aphelion: 9 December 2023)[1][2] |

| Perihelion | 0.59278 au[3] (last perihelion: 9 February 1986) (next perihelion: 28 July 2061)[3] |

|

Semi-major axis |

17.737 au |

| Eccentricity | 0.96658 |

|

Orbital period (sidereal) |

74.7 yr 75y 5m 19d (perihelion to perihelion) |

|

Mean anomaly |

0.07323° |

| Inclination | 161.96° |

|

Longitude of ascending node |

59.396° |

|

Time of perihelion |

28 July 2061[3] |

|

Argument of perihelion |

112.05° |

| Earth MOID | 0.075 au (11.2 million km)[4] |

| TJupiter | -0.598 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 15 km × 8 km[6] |

|

Mean diameter |

11 km[4] |

| Mass | 2.2×1014 kg[7] |

|

Mean density |

0.6 g/cm3 (average)[8] 0.2–1.5 g/cm3 (est.)[9] |

|

Escape velocity |

~0.002 km/s |

|

Synodic rotation period |

2.2 d (52.8 h) (?)[10] |

| Albedo | 0.04[11] |

|

Apparent magnitude |

28.2 (in 2003)[12] |

Halley’s Comet or Comet Halley, officially designated 1P/Halley, is a short-period comet visible from Earth every 75–79 years.[5] Halley is the only known short-period comet that is regularly visible to the naked eye from Earth, and thus the only naked-eye comet that can appear twice in a human lifetime.[13] Halley last appeared in the inner parts of the Solar System in 1986 and will next appear in mid-2061.

Halley’s periodic returns to the inner Solar System have been observed and recorded by astronomers around the world since at least 240 BC. But it was not until 1705 that the English astronomer Edmond Halley understood that these appearances were reappearances of the same comet. As a result of this discovery, the comet is named after Halley.[14]

During its 1986 visit to the inner Solar System, Halley’s Comet became the first comet to be observed in detail by spacecraft, providing the first observational data on the structure of a comet nucleus and the mechanism of coma and tail formation.[15][16] These observations supported a number of longstanding hypotheses about comet construction, particularly Fred Whipple’s «dirty snowball» model, which correctly predicted that Halley would be composed of a mixture of volatile ices—such as water, carbon dioxide, ammonia, and dust. The missions also provided data that substantially reformed and reconfigured these ideas; for instance, it is now understood that the surface of Halley is largely composed of dusty, non-volatile materials, and that only a small portion of it is icy.

Pronunciation[edit]

Comet Halley is commonly pronounced , rhyming with valley, or , rhyming with daily.[17][18] Colin Ronan, one of Edmond Halley’s biographers, preferred , rhyming with crawly.[19] Spellings of Halley’s name during his lifetime included Hailey, Haley, Hayley, Halley, Hawley, and Hawly, so its contemporary pronunciation is uncertain, but the version rhyming with valley seems to be preferred by current bearers of the surname.[20]

Computation of orbit[edit]

The orbital path of Halley, against the orbits of the planets (animation)

Halley was the first comet to be recognized as periodic. Until the Renaissance, the philosophical consensus on the nature of comets, promoted by Aristotle, was that they were disturbances in Earth’s atmosphere. This idea was disproved in 1577 by Tycho Brahe, who used parallax measurements to show that comets must lie beyond the Moon. Many were still unconvinced that comets orbited the Sun, and assumed instead that they must follow straight paths through the Solar System.[21]

In 1687, Sir Isaac Newton published his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in which he outlined his laws of gravity and motion. His work on comets was decidedly incomplete. Although he had suspected that two comets that had appeared in succession in 1680 and 1681 were the same comet before and after passing behind the Sun (he was later found to be correct; see Newton’s Comet),[22] he was unable to completely reconcile comets into his model.

Ultimately, it was Newton’s friend, editor and publisher, Edmond Halley, who, in his 1705 Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets, used Newton’s new laws to calculate the gravitational effects of Jupiter and Saturn on cometary orbits.[23] Having compiled a list of 24 comet observations, he calculated that the orbital elements of a second comet that had appeared in 1682 were nearly the same as those of two comets that had appeared in 1531 (observed by Petrus Apianus) and 1607 (observed by Johannes Kepler).[23][24] Halley thus concluded that all three comets were, in fact, the same object returning about every 76 years, a period that has since been found to vary between 74 and 79 years. After a rough estimate of the perturbations the comet would sustain from the gravitational attraction of the planets, he predicted its return for 1758.[25] While he had personally observed the comet around perihelion in September 1682,[26] Halley died in 1742 before he could observe its predicted return.[27]

Halley’s prediction of the comet’s return proved to be correct, although it was not seen until 25 December 1758, by Johann Georg Palitzsch, a German farmer and amateur astronomer. It did not pass through its perihelion until 13 March 1759, the attraction of Jupiter and Saturn having caused a retardation of 618 days.[28] This effect was computed before its return (with a one-month error to 13 April)[29] by a team of three French mathematicians, Alexis Clairaut, Joseph Lalande, and Nicole-Reine Lepaute.[30] The confirmation of the comet’s return was the first time anything other than planets had been shown to orbit the Sun. It was also one of the earliest successful tests of Newtonian physics, and a clear demonstration of its explanatory power.[31] The comet was first named in Halley’s honour by French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille in 1759.[31]

Some scholars have proposed that first-century Mesopotamian astronomers already had recognized Halley’s Comet as periodic.[32] This theory notes a passage in the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Horayot[33] that refers to «a star which appears once in seventy years that makes the captains of the ships err.»[34]

Researchers in 1981 attempting to calculate the past orbits of Halley by numerical integration starting from accurate observations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries could not produce accurate results further back than 837 owing to a close approach to Earth in that year. It was necessary to use ancient Chinese comet observations to constrain their calculations.[35]

Orbit and origin[edit]

Halley’s orbital period has varied between 74 and 79 years since 240 BC.[31][36] Its orbit around the Sun is highly elliptical, with an orbital eccentricity of 0.967 (with 0 being a circle and 1 being a parabolic trajectory). The perihelion, the point in the comet’s orbit when it is nearest the Sun, is 0.59 au (88 million km). This is between the orbits of Mercury and Venus. Its aphelion, or farthest distance from the Sun, is 35 au (5.2 billion km) (roughly the distance of Pluto). Unusual for an object in the Solar System, Halley’s orbit is retrograde; it orbits the Sun in the opposite direction to the planets, or, clockwise from above the Sun’s north pole. The orbit is inclined by 18° to the ecliptic, with much of it lying south of the ecliptic. (Because it is retrograde, the true inclination is 162°.)[37] Owing to the retrograde orbit, it has one of the highest velocities relative to the Earth of any object in the Solar System. The 1910 passage was at a relative velocity of 70.56 km/s (157,800 mph).[4] Because its orbit comes close to Earth’s in two places, Halley is associated with two meteor showers: the Eta Aquariids in early May, and the Orionids in late October.[38] Halley is the parent body to the Orionids, while observations conducted around the time of Halley’s appearance in 1986 suggested that the comet could additionally perturb the Eta Aquariids, although it might not be the parent of that shower.[39]

Halley is classified as a periodic or short-period comet; one with an orbit lasting 200 years or less.[40] This contrasts it with long-period comets, whose orbits last for thousands of years. Periodic comets have an average inclination to the ecliptic of only ten degrees, and an orbital period of just 6.5 years, so Halley’s orbit is atypical.[31] Most short-period comets (those with orbital periods shorter than 20 years and inclinations of 20–30 degrees or less) are called Jupiter-family comets. Those resembling Halley, with orbital periods of between 20 and 200 years and inclinations extending from zero to more than 90 degrees, are called Halley-type comets.[40][41] As of 2015, only 75 Halley-type comets have been observed, compared with 511 identified Jupiter-family comets.[42]

The orbits of the Halley-type comets suggest that they were originally long-period comets whose orbits were perturbed by the gravity of the giant planets and directed into the inner Solar System.[40] If Halley was once a long-period comet, it is likely to have originated in the Oort cloud,[41] a sphere of cometary bodies around 20,000–50,000 au from the Sun. Conversely the Jupiter-family comets are generally believed to originate in the Kuiper belt,[41] a flat disc of icy debris between 30 au (Neptune’s orbit) and 50 au from the Sun (in the scattered disc). Another point of origin for the Halley-type comets was proposed in 2008, when a trans-Neptunian object with a retrograde orbit similar to Halley’s was discovered, 2008 KV42, whose orbit takes it from just outside that of Uranus to twice the distance of Pluto. It may be a member of a new population of small Solar System bodies that serves as the source of Halley-type comets.[43]