Всего найдено: 9

Точно первая часть двойной фамилии не склоняется? Разве неверно говорить «роман Новиков-Прибоя», «творчество Лебедев-Кумача», «судьба Антонов-Овсеенко»? Ср. похожий случай, который описан в вашем «Письмовнике»: «В русском языке сложилась традиция употреблять фамилии ряда иностранных деятелей (преимущественно писателей) в сочетании с именами: Вальтер Скотт, Жюль Верн, Майн Рид, Конан Дойль, Брет Гарт, Оскар Уальд, Ромен Роллан; ср. также литературные персонажи: Робин Гуд, Шерлок Холмс, Нат Пинкертон. Употребление этих фамилий отдельно, без имен мало распространено (в особенности это касается односложных фамилий; вряд ли кто-нибудь читал в детстве Верна, Рида, Дойля и Скотта!). Следствием такого тесного единства имени и фамилии оказывается склонение в косвенных падежах только фамилии: Вальтер Скотта, Жюль Верну, с Майн Ридом, о Робин Гуде и т.п.»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В приведенном Вами фрагменте из «Письмовника» речь идет не о двойной фамилии, а о сочетаниях иностранных имен и фамилий. Склонение двойных фамилий подчиняется другому правилу. В русских двойных фамилиях первая часть склоняется, если она сама по себе употребляется как фамилия, например: песни Соловьева-Седого, картины Соколова-Скаля, роман Новикова-Прибоя, творчество Лебедева-Кумача, судьба Антонова-Овсеенко. Если же первая часть не образует фамилии, то она не склоняется, например: исследования Грум-Гржимайло, в роли Сквозник-Дмухановского, скульптура Демут-Малиновского.

Ударение в имени Артур (Конан Дойл)

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: Артур Конан Дойль.

Доброго времени!

Очень прошу Вас дать точное написание фамилии писателя.

Источники дают разные варианты. В редакции ломаются копья.

Конан Дойл (Кругосвет, Либ. ру)

Конан Дойль (Википедия, обложки книг)

Конан Дойл; Конан-Дойль (словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона)

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словари, действительно, фиксируют оба варианта, это означает, что оба допустимы. Важно придерживаться выбранного написания во всем тексте. В БСЭ: Конан Дойл.

Собака Баскервилей. В слове Баскервилей куда падает ударение?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словарная рекомендация: «Собака Баскервилей» (роман А. Конан Дойла).

Какое окончание правильное: Именно по этому адресу Артур Конан Дойл поселил придуманного им персонажа (или придуманный им персонаж) — сыщика Шерлока Холмса ?????

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верны оба варианта, существительное персонаж может употребляться как одушевленное и как неодушевленное.

Я видел в печатных изданиях, что при склонении имени английского писателя Доиля его имя оставлялось в имеительном падеже, то есть «у Конан Доиля», «с Конан Доилем».

Разве имя Конан не должно склоняться (у Конана, с Конаном)?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вот словарная рекомендация:

Словарь имён собственных

Конан Дойл (Дойль) Артур, Конан Дойла (Дойля) Артура

Как правильно — Конан Дойл или Конан-Дойл?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно раздельное написание.

Cкажите как правильно говорить Артура Конана Дойла или Артура Конан Дойла? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Допустимы оба варианта.

Как правильно: Артура Конан Дойла или Артура Конана Дойла?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Артура Конана Дойла (Дойля)_.

|

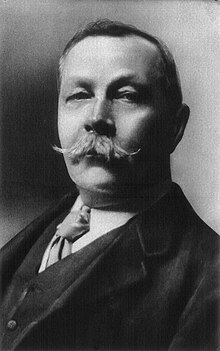

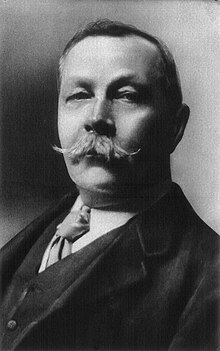

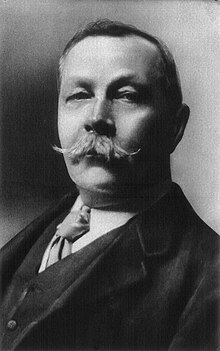

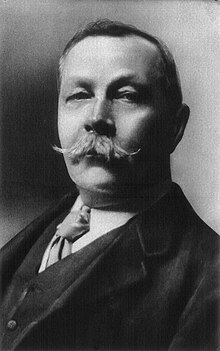

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle KStJ DL |

|

|---|---|

Arthur Conan Doyle in June 1914 |

|

| Born | Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle 22 May 1859 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 7 July 1930 (aged 71) Crowborough, Sussex, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Genre |

|

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 5 (including Adrian and Jean) |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| www.conandoyleestate.com |

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle KStJ DL (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for A Study in Scarlet, the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Holmes and Dr. Watson. The Sherlock Holmes stories are milestones in the field of crime fiction.

Doyle was a prolific writer; other than Holmes stories, his works include fantasy and science fiction stories about Professor Challenger, and humorous stories about the Napoleonic soldier Brigadier Gerard, as well as plays, romances, poetry, non-fiction, and historical novels. One of Doyle’s early short stories, «J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement» (1884), helped to popularise the mystery of the Mary Celeste.

Name[edit]

Doyle is often referred to as «Sir Arthur Conan Doyle» or «Conan Doyle», implying that «Conan» is part of a compound surname rather than a middle name. His baptism entry in the register of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, gives «Arthur Ignatius Conan» as his given names and «Doyle» as his surname. It also names Michael Conan as his godfather.[1] The catalogues of the British Library and the Library of Congress treat «Doyle» alone as his surname.[2]

Steven Doyle, publisher of The Baker Street Journal, wrote: «Conan was Arthur’s middle name. Shortly after he graduated from high school he began using Conan as a sort of surname. But technically his last name is simply ‘Doyle’.»[3] When knighted, he was gazetted as Doyle, not under the compound Conan Doyle.[4]

Early life[edit]

Title page from Arthur Conan Doyle’s thesis

Doyle was born on 22 May 1859 at 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh, Scotland.[5][6] His father, Charles Altamont Doyle, was born in England, of Irish Catholic descent, and his mother, Mary (née Foley), was Irish Catholic. His parents married in 1855.[7] In 1864 the family scattered because of Charles’s growing alcoholism, and the children were temporarily housed across Edinburgh. Arthur lodged with Mary Burton, the aunt of a friend, at Liberton Bank House on Gilmerton Road, while studying at Newington Academy.[8]

In 1867, the family came together again and lived in squalid tenement flats at 3 Sciennes Place.[9] Doyle’s father died in 1893, in the Crichton Royal, Dumfries, after many years of psychiatric illness.[10][11] Beginning at an early age, throughout his life Doyle wrote letters to his mother, and many of them were preserved.[12]

Supported by wealthy uncles, Doyle was sent to England, to the Jesuit preparatory school Hodder Place, Stonyhurst in Lancashire, at the age of nine (1868–70). He then went on to Stonyhurst College, which he attended until 1875. While Doyle was not unhappy at Stonyhurst, he said he did not have any fond memories of it because the school was run on medieval principles: the only subjects covered were rudiments, rhetoric, Euclidean geometry, algebra, and the classics.[13] Doyle commented later in his life that this academic system could only be excused «on the plea that any exercise, however stupid in itself, forms a sort of mental dumbbell by which one can improve one’s mind».[13] He also found the school harsh, noting that, instead of compassion and warmth, it favoured the threat of corporal punishment and ritual humiliation.[14]

From 1875 to 1876, he was educated at the Jesuit school Stella Matutina in Feldkirch, Austria.[9] His family decided that he would spend a year there in order to perfect his German and broaden his academic horizons.[15] He later rejected the Catholic faith and became an agnostic.[16] One source attributed his drift away from religion to the time he spent in the less strict Austrian school.[14] He also later became a spiritualist mystic.[17]

Medical career[edit]

From 1876 to 1881, Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh Medical School; during this period he spent time working in Aston (then a town in Warwickshire, now part of Birmingham), Sheffield and Ruyton-XI-Towns, Shropshire.[18] Also during this period, he studied practical botany at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh.[19] While studying, Doyle began writing short stories. His earliest extant fiction, «The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe», was unsuccessfully submitted to Blackwood’s Magazine.[9] His first published piece, «The Mystery of Sasassa Valley», a story set in South Africa, was printed in Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal on 6 September 1879.[9][20] On 20 September 1879, he published his first academic article, «Gelsemium as a Poison» in the British Medical Journal,[9][21][22] a study which The Daily Telegraph regarded as potentially useful in a 21st-century murder investigation.[23]

Doyle was the doctor on the Greenland whaler Hope of Peterhead in 1880.[24] On 11 July 1880, John Gray’s Hope and David Gray’s Eclipse met up with the Eira and Leigh Smith. The photographer W. J. A. Grant took a photograph aboard the Eira of Doyle along with Smith, the Gray brothers, and ship’s surgeon William Neale, who were members of the Smith expedition. That expedition explored Franz Josef Land, and led to the naming, on 18 August, of Cape Flora, Bell Island, Nightingale Sound, Gratton («Uncle Joe») Island, and Mabel Island.[25]

After graduating with Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery (M.B. C.M.) degrees from the University of Edinburgh in 1881, he was ship’s surgeon on the SS Mayumba during a voyage to the West African coast.[9] He completed his Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree (an advanced degree beyond the basic medical qualification in the UK) with a dissertation on tabes dorsalis in 1885.[26][27]

In 1882, Doyle partnered with his former classmate George Turnavine Budd in a medical practice in Plymouth, but their relationship proved difficult, and Doyle soon left to set up an independent practice.[9][28] Arriving in Portsmouth in June 1882, with less than £10 (£1100 in 2019[29]) to his name, he set up a medical practice at 1 Bush Villas in Elm Grove, Southsea.[30] The practice was not successful. While waiting for patients, Doyle returned to writing fiction.

Doyle was a staunch supporter of compulsory vaccination and wrote several articles advocating the practice and denouncing the views of anti-vaccinators.[31][32]

In early 1891, Doyle embarked on the study of ophthalmology in Vienna. He had previously studied at the Portsmouth Eye Hospital in order to qualify to perform eye tests and prescribe glasses. Vienna had been suggested by his friend Vernon Morris as a place to spend six months and train to be an eye surgeon. But Doyle found it too difficult to understand the German medical terms being used in his classes in Vienna, and soon quit his studies there. For the rest of his two-month stay in Vienna, he pursued other activities, such as ice skating with his wife Louisa and drinking with Brinsley Richards of the London Times. He also wrote The Doings of Raffles Haw.

After visiting Venice and Milan, he spent a few days in Paris observing Edmund Landolt, an expert on diseases of the eye. Within three months of his departure for Vienna, Doyle returned to London. He opened a small office and consulting room at 2 Upper Wimpole Street, or 2 Devonshire Place as it was then. (There is today a Westminster City Council commemorative plaque over the front door.) He had no patients, according to his autobiography, and his efforts as an ophthalmologist were a failure.[33][34][35]

Literary career[edit]

Sherlock Holmes[edit]

Doyle struggled to find a publisher. His first work featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, A Study in Scarlet, was written in three weeks when he was 27 and was accepted for publication by Ward Lock & Co on 20 November 1886, which gave Doyle £25 (equivalent to £2,900 in 2019) in exchange for all rights to the story. The piece appeared a year later in the Beeton’s Christmas Annual and received good reviews in The Scotsman and the Glasgow Herald.[9]

Holmes was partially modelled on Doyle’s former university teacher Joseph Bell. In 1892, in a letter to Bell, Doyle wrote, «It is most certainly to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes … round the centre of deduction and inference and observation which I have heard you inculcate I have tried to build up a man»,[36] and in his 1924 autobiography, he remarked, «It is no wonder that after the study of such a character [viz., Bell] I used and amplified his methods when in later life I tried to build up a scientific detective who solved cases on his own merits and not through the folly of the criminal.»[37] Robert Louis Stevenson was able to recognise the strong similarity between Joseph Bell and Sherlock Holmes: «My compliments on your very ingenious and very interesting adventures of Sherlock Holmes. … can this be my old friend Joe Bell?»[38] Other authors sometimes suggest additional influences—for instance, Edgar Allan Poe’s character C. Auguste Dupin, who is mentioned, disparagingly, by Holmes in A Study in Scarlet.[39] Dr. (John) Watson owes his surname, but not any other obvious characteristic, to a Portsmouth medical colleague of Doyle’s, Dr. James Watson.[40]

Sherlock Holmes statue in Edinburgh, erected opposite the birthplace of Doyle, which was demolished c. 1970

A sequel to A Study in Scarlet was commissioned, and The Sign of the Four appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine in February 1890, under agreement with the Ward Lock company. Doyle felt grievously exploited by Ward Lock as an author new to the publishing world, and so, after this, he left them.[9] Short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes were published in the Strand Magazine. Doyle wrote the first five Holmes short stories from his office at 2 Upper Wimpole Street (then known as Devonshire Place), which is now marked by a memorial plaque.[41]

Doyle’s attitude towards his most famous creation was ambivalent.[40] In November 1891, he wrote to his mother: «I think of slaying Holmes, … and winding him up for good and all. He takes my mind from better things.» His mother responded, «You won’t! You can’t! You mustn’t!»[42] In an attempt to deflect publishers’ demands for more Holmes stories, he raised his price to a level intended to discourage them, but found they were willing to pay even the large sums he asked.[40] As a result, he became one of the best-paid authors of his time.

Statue of Holmes and the English Church in Meiringen

In December 1893, to dedicate more of his time to his historical novels, Doyle had Holmes and Professor Moriarty plunge to their deaths together down the Reichenbach Falls in the story «The Final Problem». Public outcry, however, led him to feature Holmes in 1901 in the novel The Hound of the Baskervilles. Holmes’s fictional connection with the Reichenbach Falls is celebrated in the nearby town of Meiringen.

In 1903, Doyle published his first Holmes short story in ten years, «The Adventure of the Empty House», in which it was explained that only Moriarty had fallen, but since Holmes had other dangerous enemies—especially Colonel Sebastian Moran—he had arranged to make it look as if he too were dead. Holmes was ultimately featured in a total of 56 short stories—the last published in 1927—and four novels by Doyle, and has since appeared in many novels and stories by other authors.

Other works[edit]

Doyle’s first novels were The Mystery of Cloomber, not published until 1888, and the unfinished Narrative of John Smith, published only posthumously, in 2011.[43] He amassed a portfolio of short stories, including «The Captain of the Pole-Star» and «J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement», both inspired by Doyle’s time at sea. The latter popularised the mystery of the Mary Celeste[44] and added fictional details such as that the ship was found in perfect condition (it had actually taken on water by the time it was discovered), and that its boats remained on board (the single boat was in fact missing). These fictional details have come to dominate popular accounts of the incident,[9][44] and Doyle’s alternative spelling of the ship’s name as the Marie Celeste has become more commonly used than the original spelling.[45]

Between 1888 and 1906, Doyle wrote seven historical novels, which he and many critics regarded as his best work.[40] He also wrote nine other novels, and—later in his career (1912–29)—five narratives (two of novel length) featuring the irascible scientist Professor Challenger. The Challenger stories include his best-known work after the Holmes oeuvre, The Lost World. His historical novels include The White Company and its prequel Sir Nigel, set in the Middle Ages. He was a prolific author of short stories, including two collections set in Napoleonic times and featuring the French character Brigadier Gerard.

Doyle’s works for the stage include Waterloo, which centres on the reminiscences of an English veteran of the Napoleonic Wars and features a character Gregory Brewster, written for Henry Irving; The House of Temperley, the plot of which reflects his abiding interest in boxing; The Speckled Band, adapted from his earlier short story «The Adventure of the Speckled Band»; and an 1893 collaboration with J. M. Barrie on the libretto of Jane Annie.[46]

Sporting career[edit]

While living in Southsea, the seaside resort of Portsmouth, Doyle played football as a goalkeeper for Portsmouth Association Football Club, an amateur side, under the pseudonym A. C. Smith.[47]

Doyle was a keen cricketer, and between 1899 and 1907 he played 10 first-class matches for the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC).[48] He also played for the amateur cricket teams the Allahakbarries and the Authors XI alongside fellow writers J. M. Barrie, P. G. Wodehouse and A. A. Milne.[49][50] His highest score, in 1902 against London County, was 43. He was an occasional bowler who took one first-class wicket, W. G. Grace, and wrote a poem about the achievement.[51]

In 1900, Doyle founded the Undershaw Rifle Club at his home, constructing a 100-yard range and providing shooting for local men, as the poor showing of British troops in the Boer War had led him to believe that the general population needed training in marksmanship.[52][53] He was a champion of «miniature» rifle clubs, whose members shot small-calibre firearms on local ranges.[54][55] These ranges were much cheaper and more accessible to working-class participants than large «fullbore» ranges, such as Bisley Camp, which were necessarily remote from population centres. Doyle went on to sit on the Rifle Clubs Committee of the National Rifle Association.[56]

In 1901, Doyle was one of three judges for the world’s first major bodybuilding competition, which was organised by the «Father of Bodybuilding», Eugen Sandow. The event was held in London’s Royal Albert Hall. The other two judges were the sculptor Sir Charles Lawes-Wittewronge and Eugen Sandow himself.[57]

Doyle was an amateur boxer.[58] In 1909, he was invited to referee the James Jeffries–Jack Johnson heavyweight championship fight in Reno, Nevada. Doyle wrote: «I was much inclined to accept … though my friends pictured me as winding up with a revolver at one ear and a razor at the other. However, the distance and my engagements presented a final bar.»[58]

Also a keen golfer, Doyle was elected captain of the Crowborough Beacon Golf Club in Sussex for 1910. He had moved to Little Windlesham house in Crowborough with Jean Leckie, his second wife, and resided there with his family from 1907 until his death in July 1930.[59]

He entered the English Amateur billiards championship in 1913.[60]

While living in Switzerland, Doyle became interested in skiing, which was relatively unknown in Switzerland at the time. He wrote an article, «An Alpine Pass on ‘Ski‘» for the December 1894 issue of The Strand Magazine,[61] in which he described his experiences with skiing and the beautiful alpine scenery that could be seen in the process. The article popularised the activity and began the long association between Switzerland and skiing.[62]

Family life[edit]

Doyle with his family c. 1923–1925

In 1885 Doyle married Louisa (sometimes called «Touie») Hawkins (1857–1906). She was the youngest daughter of J. Hawkins, of Minsterworth, Gloucestershire, and the sister of one of Doyle’s patients. Louisa had tuberculosis.[63] In 1907, the year after Louisa’s death, he married Jean Elizabeth Leckie (1874–1940). He had met and fallen in love with Jean in 1897, but had maintained a platonic relationship with her while his first wife was still alive, out of loyalty to her.[64] Jean outlived him by ten years, and died in London.[65]

Doyle fathered five children. He had two with his first wife: Mary Louise (1889–1976) and Arthur Alleyne Kingsley, known as Kingsley (1892–1918). He had an additional three with his second wife: Denis Percy Stewart (1909–1955), who became the second husband of Georgian Princess Nina Mdivani; Adrian Malcolm (1910–1970); and Jean Lena Annette (1912–1997).[66] None of Doyle’s five children had children of their own, so he has no living direct descendants.[67][68]

Political campaigning[edit]

Doyle served as a volunteer physician in the Langman Field Hospital at Bloemfontein between March and June 1900,[69] during the Second Boer War in South Africa (1899–1902). Later that year, he wrote a book on the war, The Great Boer War, as well as a short work titled The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct, in which he responded to critics of the United Kingdom’s role in that war, and argued that its role was justified. The latter work was widely translated, and Doyle believed it was the reason he was knighted (given the rank of Knight Bachelor) by King Edward VII in the 1902 Coronation Honours.[70] He received the accolade from the King in person at Buckingham Palace on 24 October of that year.[71]

He stood for Parliament twice as a Liberal Unionist: in 1900 in Edinburgh Central; and in 1906 in the Hawick Burghs. He received a respectable share of the vote, but was not elected.[72] He served as a Deputy-Lieutenant of Surrey beginning in 1902,[73] and was appointed a Knight of Grace of the Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in 1903.[74]

Doyle was a supporter of the campaign for the reform of the Congo Free State that was led by the journalist E. D. Morel and diplomat Roger Casement. In 1909 he wrote The Crime of the Congo, a long pamphlet in which he denounced the horrors of that colony. He became acquainted with Morel and Casement, and it is possible that, together with Bertram Fletcher Robinson, they inspired several characters that appear in his 1912 novel The Lost World.[75] Later, after the Irish Easter Rising, Casement was found guilty of treason against the Crown, and was sentenced to death. Doyle tried, unsuccessfully, to save him, arguing that Casement had been driven mad, and therefore should not be held responsible for his actions.[76]

As the First World War loomed, and having been caught up in a growing public swell of Germanophobia, Doyle gave a public donation of 10 shillings to the anti-immigration British Brothers’ League.[77] In 1914, Doyle was one of fifty-three leading British authors—including H. G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling and Thomas Hardy—who signed their names to the «Authors’ Declaration», justifying Britain’s involvement in the First World War. This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain «could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war».[78]

Legal advocate[edit]

Doyle was also a fervent advocate of justice and personally investigated two closed cases, which led to two men being exonerated of the crimes of which they were accused. The first case, in 1906, involved a shy half-British, half-Indian lawyer named George Edalji, who had allegedly penned threatening letters and mutilated animals in Great Wyrley. Police were set on Edalji’s conviction, even though the mutilations continued after their suspect was jailed.[79] Apart from helping George Edalji, Doyle’s work helped establish a way to correct other miscarriages of justice, as it was partially as a result of this case that the Court of Criminal Appeal was established in 1907.[80]

The story of Doyle and Edalji was dramatised in an episode of the 1972 BBC television series, The Edwardians. In Nicholas Meyer’s pastiche The West End Horror (1976), Holmes manages to help clear the name of a shy Parsi Indian character wronged by the English justice system. Edalji was of Parsi heritage on his father’s side. The story was fictionalised in Julian Barnes’s 2005 novel Arthur and George, which was adapted into a three-part drama by ITV in 2015.[citation needed]

The second case, that of Oscar Slater—a Jew of German origin who operated a gambling den and was convicted of bludgeoning an 82-year-old woman in Glasgow in 1908—excited Doyle’s curiosity because of inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case and a general sense that Slater was not guilty. He ended up paying most of the costs for Slater’s successful 1928 appeal.[81]

Freemasonry and spiritualism[edit]

Doyle had a longstanding interest in mystical subjects and remained fascinated by the idea of paranormal phenomena, even though the strength of his belief in their reality waxed and waned periodically over the years.

In 1887, in Southsea, influenced by Major-General Alfred Wilks Drayson, a member of the Portsmouth Literary and Philosophical Society, Doyle began a series of investigations into the possibility of psychic phenomena and attended about 20 seances, experiments in telepathy, and sittings with mediums. Writing to spiritualist journal Light that year, he declared himself to be a spiritualist, describing one particular event that had convinced him psychic phenomena were real.[82] Also in 1887 (on 26 January), he was initiated as a Freemason at the Phoenix Lodge No. 257 in Southsea. (He resigned from the Lodge in 1889, returned to it in 1902, and resigned again in 1911.)[83]

In 1889, he became a founding member of the Hampshire Society for Psychical Research; in 1893, he joined the London-based Society for Psychical Research; and in 1894, he collaborated with Sir Sidney Scott and Frank Podmore in a search for poltergeists in Devon.[84]

Doyle and the spiritualist William Thomas Stead (before the latter was lost in the sinking of the Titanic) were led to believe that Julius and Agnes Zancig had genuine psychic powers, and they claimed publicly that the Zancigs used telepathy. However, in 1924, the Zancigs confessed that their mind reading act had been a trick; they published the secret code and all other details of the trick method they had used under the title «Our Secrets!!» in a London newspaper.[85] Doyle also praised the psychic phenomena and spirit materialisations that he believed had been produced by Eusapia Palladino and Mina Crandon, both of whom were also later exposed as frauds.[86]

In 1916, at the height of the First World War, Doyle’s belief in psychic phenomena was strengthened by what he took to be the psychic abilities of his children’s nanny, Lily Loder Symonds.[87] This and the constant drumbeat of wartime deaths inspired him with the idea that spiritualism was what he called a «New Revelation»[88] sent by God to bring solace to the bereaved. He wrote a piece in Light magazine about his faith and began lecturing frequently on spiritualism. In 1918, he published his first spiritualist work, The New Revelation.

Some have mistakenly assumed that Doyle’s turn to spiritualism was prompted by the death of his son Kingsley, but Doyle began presenting himself publicly as a spiritualist in 1916, and Kingsley died on 28 October 1918 (from pneumonia contracted during his convalescence after being seriously wounded in the 1916 Battle of the Somme).[88] Nevertheless, the war-related deaths of many people who were close to him appears to have even further strengthened his long-held belief in life after death and spirit communication. Doyle’s brother Brigadier-general Innes Doyle died, also from pneumonia, in February 1919. His two brothers-in-law (one of whom was E. W. Hornung, creator of the literary character Raffles), as well as his two nephews, also died shortly after the war. His second book on spiritualism, The Vital Message, appeared in 1919.

Doyle found solace in supporting spiritualism’s ideas and the attempts of spiritualists to find proof of an existence beyond the grave. In particular, according to some,[89] he favoured Christian Spiritualism and encouraged the Spiritualists’ National Union to accept an eighth precept – that of following the teachings and example of Jesus of Nazareth. He was a member of the renowned supernaturalist organisation The Ghost Club.[90]

Doyle with his family in New York City, 1922

In 1919, the magician P. T. Selbit staged a séance at his flat in Bloomsbury, which Doyle attended. Although some later claimed that Doyle had endorsed the apparent instances of clairvoyance at that séance as genuine,[91][92] a contemporaneous report by the Sunday Express quoted Doyle as saying «I should have to see it again before passing a definite opinion on it» and «I have my doubts about the whole thing».[93] In 1920, Doyle and the noted sceptic Joseph McCabe held a public debate at Queen’s Hall in London, with Doyle taking the position that the claims of spiritualism were true. After the debate, McCabe published a booklet Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?, in which he laid out evidence refuting Doyle’s arguments and claimed that Doyle had been duped into believing in spiritualism through deliberate mediumship trickery.[94]

Doyle also debated the psychiatrist Harold Dearden, who vehemently disagreed with Doyle’s belief that many cases of diagnosed mental illness were the result of spirit possession.[95]

In 1920, Doyle travelled to Australia and New Zealand on spiritualist missionary work, and over the next several years, until his death, he continued his mission, giving talks about his spiritualist conviction in Britain, Europe, and the United States.[84]

One of the five photographs of Frances Griffiths with the alleged fairies, taken by Elsie Wright in Cottingley, England in July 1917

Doyle wrote a novel The Land of Mist centred on spiritualist themes and featuring the character Professor Challenger. He also wrote many non-fiction spiritualist works. Perhaps his most famous of these was The Coming of the Fairies (1922),[96] in which Doyle described his beliefs about the nature and existence of fairies and spirits, reproduced the five Cottingley Fairies photographs, asserted that those who suspected them being faked were wrong, and expressed his conviction that they were authentic. Decades later, the photos—taken by cousins Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright—were definitively shown to have been faked, and their creators admitted to the fakery, although both maintained that they really had seen fairies.[97]

Doyle was friends for a time with the American magician Harry Houdini. Even though Houdini explained that his feats were based on illusion and trickery, Doyle was convinced that Houdini had supernatural powers and said as much in his work The Edge of the Unknown. Houdini’s friend Bernard M. L. Ernst recounted a time when Houdini had performed an impressive trick at his home in Doyle’s presence. Houdini had assured Doyle that the trick was pure illusion and had expressed the hope that this demonstration would persuade Doyle not to go around «endorsing phenomena» simply because he could think of no explanation for what he had seen other than supernatural power. However, according to Ernst, Doyle simply refused to believe that it had been a trick.[98] Houdini became a prominent opponent of the spiritualist movement in the 1920s, after the death of his beloved mother. He insisted that spiritualist mediums employed trickery, and consistently exposed them as frauds. These differences between Houdini and Doyle eventually led to a bitter, public falling-out between them.[99]

1922 photograph of Doyle by spirit photographer Ada Deane

In 1922, the psychical researcher Harry Price accused the «spirit photographer» William Hope of fraud. Doyle defended Hope, but further evidence of trickery was obtained from other researchers.[100] Doyle threatened to have Price evicted from the National Laboratory of Psychical Research and predicted that, if he persisted in writing what he called «sewage» about spiritualists, he would meet the same fate as Harry Houdini.[101] Price wrote: «Arthur Conan Doyle and his friends abused me for years for exposing Hope.»[102] In response to the exposure of frauds that had been perpetrated by Hope and other spiritualists, Doyle led 84 members of the Society for Psychical Research to resign in protest from the society on the ground that they believed it was opposed to spiritualism.[103]

Doyle’s two-volume book The History of Spiritualism was published in 1926. W. Leslie Curnow, a spiritualist, contributed much research to the book.[104][105] Later that year, Robert John Tillyard wrote a predominantly supportive review of it in the journal Nature.[106] This review provoked controversy: Several other critics, notably A. A. Campbell Swinton, pointed out the evidence of fraud in mediumship, as well as Doyle’s non-scientific approach to the subject.[107][108][109] In 1927, Doyle gave a filmed interview, in which he spoke about Sherlock Holmes and spiritualism.[110]

Doyle and the Piltdown Hoax[edit]

Richard Milner, an American historian of science, argued that Doyle may have been the perpetrator of the Piltdown Man hoax of 1912, creating the counterfeit hominid fossil that fooled the scientific world for over 40 years. Milner noted that Doyle had a plausible motive—namely, revenge on the scientific establishment for debunking one of his favourite psychics—and said that The Lost World appeared to contain several clues referring cryptically to his having been involved in the hoax.[111][112] Samuel Rosenberg’s 1974 book Naked is the Best Disguise purports to explain how, throughout his writings, Doyle had provided overt clues to otherwise hidden or suppressed aspects of his way of thinking that seemed to support the idea that Doyle would be involved in such a hoax.[113]

However, more recent research suggests that Doyle was not involved. In 2016, researchers at the Natural History Museum and Liverpool John Moores University analyzed DNA evidence showing that responsibility for the hoax lay with the amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson, who had originally «found» the remains. He had initially not been considered the likely perpetrator, because the hoax was seen as being too elaborate for him to have devised. However, the DNA evidence showed that a supposedly ancient tooth he had «discovered» in 1915 (at a different site) came from the same jaw as that of the Piltdown Man, suggesting that he had planted them both. That tooth, too, was later proven to have been planted as part of a hoax.[114]

Chris Stringer, an anthropologist from the Natural History Museum, was quoted as saying: «Conan Doyle was known to play golf at the Piltdown site and had even given Dawson a lift in his car to the area, but he was a public man and very busy[,] and it is very unlikely that he would have had the time [to create the hoax]. So there are some coincidences, but I think they are just coincidences. When you look at the fossil evidence[,] you can only associate Dawson with all the finds, and Dawson was known to be personally ambitious. He wanted professional recognition. He wanted to be a member of the Royal Society and he was after an MBE [sic[115]]. He wanted people to stop seeing him as an amateur».[116]

Architecture[edit]

Façade of Undershaw with Doyle’s children, Mary and Kingsley, on the drive

Another of Doyle’s longstanding interests was architectural design. In 1895, when he commissioned an architect friend of his, Joseph Henry Ball, to build him a home, he played an active part in the design process.[117][118] The home in which he lived from October 1897 to September 1907, known as Undershaw (near Hindhead, in Surrey),[119] was used as a hotel and restaurant from 1924 until 2004, when it was bought by a developer and then stood empty while conservationists and Doyle fans fought to preserve it.[63] In 2012, the High Court in London ruled in favor of those seeking to preserve the historic building, ordering that the redevelopment permission be quashed on the ground that it had not been obtained through proper procedures.[120] The building was later approved to become part of Stepping Stones, a school for children with disabilities and special needs.

Doyle made his most ambitious foray into architecture in March 1912, while he was staying at the Lyndhurst Grand Hotel: He sketched the original designs for a third-storey extension and for an alteration of the front facade of the building.[121] Work began later that year, and when it was finished, the building was a nearly exact manifestation of the plans Doyle had sketched. Superficial alterations have been subsequently made, but the essential structure is still clearly Doyle’s.[122]

In 1914, on a family trip to the Jasper National Park in Canada, he designed a golf course and ancillary buildings for a hotel. The plans were realised in full, but neither the golf course nor the buildings have survived.[123]

In 1926, Doyle laid the foundation stone for a Spiritualist Temple in Camden, London. Of the building’s total £600 construction costs, he provided £500.[124]

Crimes Club[edit]

The Crimes Club was a private social club founded by Doyle in 1903, whose purpose was discussion of crime and detection, criminals and criminology, and continues to this day as «Our Society», with membership numbers limited to 100. The club meets four times a year at the Imperial Hotel, Russell Square, London, where all proceedings are strictly confidential («Chatham House rules»). Its logo is a silhouette of Doyle.[125]

The club’s earliest members included John Churton Collins, Japanologist Arthur Diósy, Sir Edward Marshall Hall, Sir Travers Humphreys, H. B. Irving, author (Thou Shalt Do No Murder) Arthur Lambton, William Le Queux, A. E. W. Mason, coroner Ingleby Oddie, Sir Max Pemberton, Bertram Fletcher Robinson, George R. Sims, Sir Bernard Spilsbury, P. G. Wodehouse, and Filson Young.[126]

Death[edit]

Doyle in 1930, the year of his death, with his son Adrian

Doyle was found clutching his chest in the hall of Windlesham Manor, his house in Crowborough, Sussex, on 7 July 1930. He died of a heart attack at the age of 71. His last words were directed toward his wife: «You are wonderful.»[127] At the time of his death, there was some controversy concerning his burial place, as he was avowedly not a Christian, considering himself a Spiritualist. He was first buried on 11 July 1930 in Windlesham rose garden.

He was later reinterred together with his wife in Minstead churchyard in the New Forest, Hampshire.[9] Carved wooden tablets to his memory and to the memory of his wife, originally from the church at Minstead, are on display as part of a Sherlock Holmes exhibition at Portsmouth Museum.[128][129] The epitaph on his gravestone in the churchyard reads, in part: «Steel true/Blade straight/Arthur Conan Doyle/Knight/Patriot, Physician and man of letters».[130]

A statue honours Doyle at Crowborough Cross in Crowborough, where he lived for 23 years.[131] There is a statue of Sherlock Holmes in Picardy Place, Edinburgh, close to the house where Doyle was born.[132]

Honours and awards[edit]

Knight Bachelor (1902)[4]

Knight of Grace of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (1903)

Queen’s South Africa Medal (1901)

Knight of the Order of the Crown of Italy (1895)

Order of the Medjidie – 2nd Class (Ottoman Empire) (1907)

Commemoration[edit]

Doyle has been commemorated with statues and plaques since his death. In 2009, he was among the ten people selected by the Royal Mail for their «Eminent Britons» commemorative postage stamp issue.[133]

Portrayals[edit]

Arthur Conan Doyle has been portrayed by many actors, including:

Television series[edit]

- Nigel Davenport in the BBC Two series The Edwardians, in the episode «Conan Doyle» (1972)[134]

- Michael Ensign in the Voyagers! episode «Jack’s Back» (1983)

- Robin Laing and Charles Edwards in Murder Rooms: Mysteries of the Real Sherlock Holmes (2000–2001)

- Geraint Wyn Davies in Murdoch Mysteries, 3 episodes (2008–2013)

- Alfred Molina in the Drunk History (American series) episode «Detroit» (2013)

- David Calder in the miniseries Houdini (2014)

- Martin Clunes in the miniseries Arthur & George (2015)

- Bruce Mackinnon and Bradley Walsh in Drunk History (British series), in series 2, episodes 5 and 8 respectively (2016)[135][136]

- Stephen Mangan in Houdini & Doyle (2016)

- Michael Pitthan in the German TV series Charité episode «Götterdämmerung» (2017)

- Bill Paterson in the Urban Myths episode «Agatha Christie» (2018)

Television films[edit]

- Peter Cushing in The Great Houdini (1976)

- David Warner in Houdini (1998)

- Richard Wilson in Reichenbach Falls (2007)

- Michael McElhatton in Agatha and the Truth of Murder (2018)

Theatrical films[edit]

- Paul Bildt in The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes (1937)

- Peter O’Toole in FairyTale: A True Story (1997)

- Edward Hardwicke in Photographing Fairies (1997)

- Tom Fisher in Shanghai Knights (2003)

- Ian Hart in Finding Neverland (2004)

Other media[edit]

- Carleton Hobbs in the BBC radio drama Conan Doyle Investigates (1972)[137]

- Iain Cuthbertson in the BBC radio drama Conan Doyle and The Edalji Case (1987)[138]

- Peter Jeffrey in the BBC radio drama Conan Doyle’s Strangest Case (1995)[139]

- Adrian Lukis in the stage adaptation of the novel Arthur & George (2010)[140]

- Chris Tallman in Chapter 10 of The Dead Authors Podcast (2012)[141]

- Steven Miller in the Jago & Litefoot audio drama «The Monstrous Menagerie» (2014)[142]

- Eamon Stocks in the video game Assassin’s Creed Syndicate (2015)[143]

- Ryohei Kimura in the mobile game Ikémen Vampire: Temptation in the Dark (2019)[144]

In fiction[edit]

Arthur Conan Doyle is the ostensible narrator of Ian Madden’s short story «Cracks in an Edifice of Sheer Reason».[145]

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle features as a recurring character in Pip Murphy’s Christie and Agatha’s Detective Agency series, including A Discovery Disappears[146] and Of Mountains and Motors.[147]

See also[edit]

- William Gillette, a personal friend who performed the most famous stage version of Sherlock Holmes

- List of notable Freemasons

- Physician writer

References[edit]

- ^ Stashower says that the compound version of his surname originated from his great-uncle Michael Conan, a distinguished journalist, from whom Arthur and his elder sister, Annette, received the compound surname of «Conan Doyle» (Stashower 20–21). The same source points out that in 1885 he was describing himself on the brass nameplate outside his house, and on his doctoral thesis, as «A. Conan Doyle» (Stashower 70).

- ^ Redmond, Christopher (2009). Sherlock Holmes Handbook 2nd ed. Dundurn. p. 97. Google Books. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Doyle, Steven; Crowder, David A. (2010). Sherlock Holmes for Dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 51.

- ^ a b «No. 27494». The London Gazette. 11 November 1902. p. 7165.

The entry, ‘Arthur Conan Doyle, Esq., M.D., D.L.’, is alphabetised based on ‘Doyle’.

- ^ «Scottish Writer Best Known for His Creation of the Detective Sherlock Holmes». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ «Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Biography». sherlockholmesonline.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ The details of the births of Arthur and his siblings are unclear. Some sources say there were nine children, some say ten. It seems three died in childhood. See Owen Dudley Edwards, «Doyle, Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan (1859–1930)», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; Encyclopædia Britannica Archived 27 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine; Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters, Wordsworth Editions, 2007 p. viii; ISBN 978-1-84022-570-9.

- ^ «Liberton Bank House, 1, Gilmerton Road, Edinburgh». Register for Scotland: Buildings at Risk. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Owen Dudley Edwards, «Doyle, Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan (1859–1930)», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Lellenberg, Jon; Stashower, Daniel; Foley, Charles (2007). Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters. HarperPress. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-00-724759-2.

- ^ Stashower, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Jon Lellenberg; Daniel Stashower; Charles Foley, eds. (2008). Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-724760-8.

- ^ a b Pascal, Janet (2000). Arthur Conan Doyle: Beyond Baker Street. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-19-512262-3.

- ^ a b O’Brien, James (2013). The Scientific Sherlock Holmes: Cracking the Case with Science and Forensics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-979496-6.

- ^ Miller, Russell (2010). The Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-9308-6.

- ^ Golgotha Press (2011). The Life and Times of Arthur Conan Doyle. BookCaps Study Guides. ISBN 978-1-62107-027-6.

In time, he would reject the Catholic religion and become an agnostic.

- ^ Pascal, Janet B. (2000). Arthur Conan Doyle: Beyond Baker Street. Oxford University Press. p. 139.

- ^ Brown, Yoland (1988). Ruyton XI Towns, Unusual Name, Unusual History. Brewin Books. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-947731-41-5.

- ^ McNeill, Colin (6 January 2016). «Mystery solved of how Sherlock Holmes knew so much about poisonous plants». Herald Scotland. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ Stashower, Daniel (2000). Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle. Penguin Books. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-8050-5074-4.

- ^ Doyle, Arthur Conan (20 September 1879). «Arthur Conan Doyle takes it to the limit (1879)». BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 339: b2861. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2861. S2CID 220100995. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.(subscription required)

- ^ Doyle, Arthur Conan (20 September 1879). «Letters, Notes, and Answers to Correspondents». British Medical Journal. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. (subscription required)

- ^ Robert Mendick (23 May 2015). «Russian supergrass ‘poisoned after being tricked into visiting Paris’«. The Sunday Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015.

- ^ Conan Doyle, Arthur (Author), Lellenberg, Jon (Editor), Stashower, Daniel (Editor) (2012). Dangerous Work: Diary of an Arctic Adventure. University of Chicago Press; ISBN 0-226-00905-X, 978-0-226-00905-6.

- ^ Capelotti, P.J. (2013). Shipwreck at Cape Flora: The Expeditions of Benjamin Leigh Smith, England’s Forgotten Arctic Explorer. New York: University of Calgary. pp. 156–162. ISBN 978-1-55238-712-2.

- ^ Available at the Edinburgh Research Archive Archived 11 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ «MD Thesis 1885, Unpaginated». images.is.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Stashower, pp. 52–59.

- ^ United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth «consistent series» supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). «What Was the U.K. GDP Then?». MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Stashower, pp. 55, 58–59.

- ^ «Compulsory Vaccination – The Evening Mail – The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia». www.arthur-conan-doyle.com.

- ^ «Compulsory Vaccination – The Hampshire County Times – The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia». www.arthur-conan-doyle.com.

- ^ Higham, Charles (1976). The Adventures of Conan Doyle. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 86–87.

- ^ Diniejko, Andrzej. «Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: A Biographical Introduction». The Victorian Web. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ Stashower, pp. 114–118.

- ^ Independent, 7 August 2006 Archived 22 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ Doyle, Arthur Conan, Memories and Adventures (Reprint), Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge) 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Letter from R L Stevenson to Doyle 5 April 1893 The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson Volume 2/Chapter XII.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- ^ a b c d Carr, John Dickson (1947). The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

- ^ City of Westminster green plaques Archived 16 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine; accessed 22 March 2014.

- ^ Panek, LeRoy Lad (1987). An Introduction to the Detective Story. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-87972-377-7.

- ^ Saunders, Emma (6 June 2011). «First Conan Doyle novel to be published». BBC. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- ^ a b Macdonald Hastings, Mary Celeste, (1971); ISBN 0-7181-1024-2.

- ^ «Mary Celeste – definition of Mary Celeste in English from the Oxford dictionary». Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ «Jane Annie – J. M. Barrie and Doyle’s Libretto Rather Puzzles London», The New York Times, 28 May 1893, p. 13.

- ^ Juson, Dave; Bull, David (2001). Full-Time at The Dell. Hagiology Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 0-9534474-2-1.

- ^ «Arthur Conan Doyle». ESPN Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ «What is the connection between Peter Pan, Sherlock Holmes, Winnie the Pooh and the noble sport of cricket? Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Parkinson, Justin (26 July 2014). «Authors and actors revive cricket rivalry». BBC News Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ «London County v Marylebone Cricket Club at Crystal Palace Park, 23–25 Aug 1900». Static.cricinfo.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ «Champions of Civilian Marksmanship». American Rifleman. National Rifle Association of America. 8 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Arthur Conan-Doyle (5 January 1901). «The Undershaw Rifle Club» (English). The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ «Rifle Shooting as a National Pursuit». The Arthur Conan Doyle EncyclopediaThe Arthur Conan Doyle EncyclopediaThe Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. 14 June 1905. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Captain Philip Trevor (June 1901). «A British Commando». The Arthur Conan Doyle EncyclopediaThe Arthur Conan Doyle EncyclopediaThe Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ «History». National Rifle Association. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ «Eugen Sandow: Bodybuilding’s Great Pioneer». 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ a b Rawson, Mitchell (13 March 1961). «A Case for Sherlock». Sports Illustrated Vault. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle. «Memories and Adventures», p. 222. Oxford University Press, 2012; ISBN 1441719288.

- ^ «Billiards: The Amateur Championship». The Manchester Guardian. 22 January 1913. p. 8 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Guardian and The Observer. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ «An Alpine Pass on ‘Ski’«. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ «How Arthur’s Secret Obsession Changed the World». 5 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b Leeman, Sue, «Sherlock Holmes fans hope to save Doyle’s house from developers», Associated Press, 28 July 2006.

- ^ Janet B. Pascal (2000). Arthur Conan Doyle: Beyond Baker Street. p. 95. Oxford University Press; ISBN 0195122623.

- ^ «No. 35171». The London Gazette. 23 May 1941. p. 2977.

- ^ «Obituary: Air Commandant Dame Jean Conan Doyle» Archived 18 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Independent; retrieved 6 November 2012

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (18 January 2010). «Heirs to Sherlock Holmes Face Web of Ownership Issues». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.

- ^ «Who owns Sherlock Holmes?». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Miller, Russell. The Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2008. pp. 211–217; ISBN 0-312-37897-1,

- ^ «The Coronation Honours». The Times. No. 36804. London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- ^ «No. 27494». The London Gazette. 11 November 1902. p. 7165.

- ^ «Arthur Conan Doyle: 19 things you didn’t know» Archived 1 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 25 November 2014

- ^ «No. 27453». The London Gazette. 11 July 1902. p. 4444.

- ^ «No. 27550». The London Gazette. 8 May 1903. p. 2921.

- ^ Spiring, Paul. «B. Fletcher Robinson & The Lost World«. Bfronline.biz. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Wijesinha, Rajiva (2013). Twentieth Century Classics: Reflections on Writers and Their Times. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Winder, Robert (2004). Bloody Foreigners. London: Little, Brown. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-349-13880-0.

- ^ Milne, Nick (20 October 2014). «1914 Authors’ Manifesto Defending Britain’s Involvement in WWI, Signed by H.G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle». Slate. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ International Commentary on Evidence, Volume 4, Issue 2 2006 Article 3, Boxes in Boxes: Julian Bardes, Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and the Edalji Case, D. Michael Risinger

- ^ International Commentary on Evidence, Volume 4, Issue 2 2006 Article 3, Boxes in Boxes: Julian Barnes, Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and the Edalji Case, D. Michael Risinger

- ^ Roughead, William (1941). «Oscar Slater». In Hodge, Harry (ed.). Famous Trials. Vol. 1. Penguin Books. p. 108.

- ^ Wingett, Matt (2016). Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light, 1887–1920. Life Is Amazing. pp. 19–32. ISBN 978-0-9572413-5-0.

- ^ Beresiner, Yasha (2007). «Arthur Conan Doyle, Spiritualist and Freemason». Masonic papers. Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015.

- ^ a b Wingett, Matt (2016). Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light, 1887–1920. Life Is Amazing. pp. 32–36. ISBN 978-0-9572413-5-0.

- ^ John Booth. (1986). Psychic Paradoxes. Prometheus Books. p. 8; ISBN 978-0-87975-358-0.

- ^ William Kalush, Larry Ratso Sloman. (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero. Atria Books. ISBN 978-0-7432-7208-7.

- ^ Wingett, Matt (2016). Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light, 1887–1920. Life Is Amazing. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-9572413-5-0.

- ^ a b Wingett, Matt (2016). Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light, 1887–1920. Life Is Amazing. pp. 44–48. ISBN 978-0-9572413-5-0.

- ^ Price, Leslie (2010). «Did Conan Doyle Go Too Far?». Psychic News (4037).

- ^ Ian Topham (31 October 2010). «The Ghost Club – A History by Peter Underwood». Mysteriousbritain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- ^ Baker, Robert A. (1996). Hidden Memories: Voices and Visions from Within. Prometheus Books. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-57392-094-0.

- ^ Christopher, Milbourne. (1996). The Illustrated History of Magic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-435-07016-8.

- ^ Wingett, Matt (2016). Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light, 1887–1920. Life Is Amazing. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-9572413-5-0.

- ^ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based On Fraud? The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. London Watts & Co.

- ^ Dearden, Harold. (1975 edition). Devilish But True: The Doctor Looks at Spiritualism. EP Publishing Limited. pp. 70–72. ISBN 0-7158-1041-3.

- ^ «The Coming of the Fairies». British Library catalogue. British Library. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ «Fairies, Phantoms, and Fantastic Photographs». Presenter: Arthur C. Clarke. Narrator: Anna Ford. Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers. ITV. 22 May 1985. No. 6, season 1

- ^ Polidoro, Massimo (July 2006). «Houdini’s Impossible Demonstration». Skeptical Inquirer. The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Massimo Polidoro. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books. pp. 120–124. ISBN 1-59102-086-7.

- ^ Massimo Polidoro (2011). «Photos of Ghosts: The Burden of Believing the Unbelievable by Massimo Polidoro». Csicop.org. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- ^ William Kalush, Larry Ratso Sloman. (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero. Atria Books. pp. 419–420. ISBN 978-0-7432-7208-7.

- ^ Massimo Polidoro. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-57392-896-0.

- ^ G. K. Nelson. (2013). Spiritualism and Society. Routledge. p. 159; ISBN 978-0-415-71462-4.

- ^ Hall, Trevor H. (1978). Sherlock Holmes and his Creator. Duckworth. p. 121.

- ^ Stashower, Daniel (1999). Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle. Henry Holt & Company. «A Spiritualist researcher named Leslie Curnow contributed a great deal of material and wrote some of the chapters, which Conan Doyle freely admits in the book’s preface.»

- ^ Tillyard, Robert John (1926). «The History of Spiritualism». Nature. 118 (2961): 147–149. Bibcode:1926Natur.118..147T. doi:10.1038/118147a0. S2CID 4122097.

- ^ Swinton, A. A. Campbell (1926). «Science and Psychical Research». Nature. 118 (2965): 299–300. Bibcode:1926Natur.118..299S. doi:10.1038/118299a0. S2CID 4124050.

- ^ Donkin, Bryan (1926). «Science and Psychical Research». Nature. 118 (2970): 480. Bibcode:1926Natur.118Q.480D. doi:10.1038/118480a0. S2CID 4125188.

- ^ Donkin, Bryan (1926). «Science and Psychical Research». Nature. 118 (2975): 658–659. Bibcode:1926Natur.118..658D. doi:10.1038/118658a0. S2CID 4059745.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle Interviewed on Sherlock Holmes and Spirituality. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ «Piltdown Man: Britain’s Greatest Hoax». BBC. 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ McKie, Robin (5 February 2012). «Piltdown Man: British archaeology’s greatest hoax». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Samuel Rosenberg. (1974). Naked is the Best Disguise: The Death and Resurrection of Sherlock Holmes. Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 0-14-004030-7.

- ^ «Piltdown Man». www.bournemouth.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ The latter honour did not exist in the lifetime of Dawson, who died in August 1916; the Order of the British Empire was founded on 4 June 1917.

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (10 August 2016). «Sir Arthur Conan Doyle cleared of Piltdown Man hoax». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Cooke, Simon, 2013, Introduction: Life and Controversy, «Charles Altamont Doyle», The Victorian Web.

- ^ Historic England. «Undershaw (1244471)». National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Duncan, Alistair (2011). An Entirely New Country: Arthur Conan Doyle, Undershaw and the Resurrection of Sherlock Holmes. MX Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908218-19-3.

- ^ «Sir Arthur Conan Doyle house development appeal upheld». BBC News. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012.

- ^ Griffith, Carolyn. «Campaigner says hotel’s writer link should secure landmark building». Lymington Times, 15 September 2017.

- ^ Glasshayes House: the 1912 extension of The Lyndhurst Grand Hotel. Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia, 2017.

- ^ The Golfball Factory, accessed September 2017, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – Golf Course Architect. Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Crossley, Frankie (17 August 2017). «Blur guitarist leads fight to save Camden Road Spiritualist Temple». Hampstead Highgate Express.

- ^ «Our Society». Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ Carrie Selina Parris. The Crimes Club: The Early Years of Our Society (PDF) (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). p. 2. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ Stashower, p. 439.

- ^ «Stock Photo – Wooden headstone of Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle at a special display in the Town’s museum. Portsmouth, Hampshire, UK». Alamy. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ «City Museums». www.portsmouthcitymuseums.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Roy (1992). «Studying Fiction: A Guide and Study Programme», p. 15. Manchester University Press; ISBN 0719033977.

- ^ «Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930)». librarything.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ «Sherlock Holmes statue reinstated in Edinburgh after tram works», bbc.co.uk; retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ «The Royal Mail celebrate eminent Britons». The Times. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ «The Edwardians: Conan Doyle». BBC Genome: Radio Times. BBC. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «Drunk History Series 2, Episode 5». British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «Drunk History Series 2, Episode 8». British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «Saturday-Night Theatre: Conan Doyle Investigates». BBC Genome: Radio Times. BBC. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «Saturday-Night Theatre: Conan Doyle and the Edalji Case». BBC Genome: Radio Times. BBC. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «Saturday Playhouse: Conan Doyle’s Strangest Case». BBC Genome: Radio Times. BBC. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Michael, Billington (23 March 2010). «Arthur and George». The Guardian. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «The Dead Authors Podcast : Chapter 10: Arthur Conan Doyle, featuring Chris Tallman». thedeadauthorspodcast.libsyn.com. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ «7. Jago & Litefoot Series 07». Big Finish Productions. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate Cast». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «アーサー・コナン・ドイル(CV:木村良平)のキャラクター紹介». ikemen.cybird.ne.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Madden, Ian, «Cracks in an Edifice of Sheer Reason», in Maguire, Susie, & Tongue, Samuel (eds.) (2018), With Their Best Clothes On, New Writing Scotland 36, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, pp. 77–85. ISBN 978-1-906841-33-1

- ^ Murphy, Pip (2021). A Discovery Disappears. Roberta Tedeschi, ill. Leicester: Sweet Cherry Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78226-796-6. OCLC 1263776847.

- ^ Murphy, Pip (2022). Of Mountains and Motors. Roberta Tedeschi, ill. Leicester: Sweet Cherry Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78226-815-4. OCLC 1295111029.

Further reading[edit]

- Martin Booth (2000). The Doctor and the Detective: A Biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Minotaur Books. ISBN 0-312-24251-4

- John Dickson Carr (2003 edition, originally published in 1949). The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Carroll and Graf Publishers.

- Michael Dirda (2014). On Conan Doyle: or, The Whole Art of Storytelling. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691164120

- Arthur Conan Doyle, Joseph McCabe (1920). Debate on Spiritualism: Between Arthur Conan Doyle and Joseph McCabe. The Appeal’s Pocket Series.

- Bernard M. L. Ernst, Hereward Carrington (1932). Houdini and Conan Doyle: The Story of a Strange Friendship. Albert and Charles Boni, Inc.

- Margalit Fox (2018). Conan Doyle for the Defense. Random House.

- Kelvin Jones (1989). Conan Doyle and the Spirits: The Spiritualist Career of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Aquarian Press.

- Jon Lellenberg, Daniel Stashower, Charles Foley (2007). Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters. HarperPress. ISBN 978-0-00-724759-2

- Andrew Lycett (2008). The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes: The Life and Times of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-7523-3

- Russell Miller (2008). The Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle: A Biography. Thomas Dunne Books.

- Pierre Nordon (1967). Conan Doyle: A Biography. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Ronald Pearsall (1977). Conan Doyle: A Biographical Solution. Littlehampton Book Services Ltd.

- Massimo Polidoro (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-896-0

- Daniel Stashower (2000). Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-8050-5074-4

External links[edit]

Digital collections

- Works by Arthur Conan Doyle in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Arthur Conan Doyle at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Arthur Conan Doyle at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Arthur Conan Doyle at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Works by or about Arthur Conan Doyle at Internet Archive

- Works by Arthur Conan Doyle at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Poems by Arthur Conan Doyle

Physical collections

- Arthur Conan Doyle Papers, Photographs, and Personal Effects at the Harry Ransom Center

- Arthur Conan Doyle Collection at Toronto Public Library

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Collection at Dartmouth College Library

- Arthur Conan Doyle Online Exhibition

- «Archival material relating to Arthur Conan Doyle». UK National Archives.

- C. Frederick Kittle’s Collection of Doyleana Archived 6 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Newberry Library

- Newspaper clippings about Arthur Conan Doyle in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Biographical information

- Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan, Knt. – Cr. 1902, The county families of the United Kingdom or Royal manual of the titled and untitled aristocracy of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, (Volume ed. 59, yr. 1919) (page 109 of 415) by Edward Walford

- The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia

- Conan Doyle in Birmingham

Other references

- 1930 audio recording of Conan Doyle speaking

- Arthur Conan Doyle at Curlie

- The short film Arthur Conan Doyle (1927) (Fox newsreel interview) is available for free download at the Internet Archive.

- The Arthur Conan Doyle Society

- Arthur Conan Doyle quotes

- Arthur Conan Doyle at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Arthur Conan Doyle at IMDb

|

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle KStJ DL |

|

|---|---|

Arthur Conan Doyle in June 1914 |

|

| Born | Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle 22 May 1859 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 7 July 1930 (aged 71) Crowborough, Sussex, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Genre |

|

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 5 (including Adrian and Jean) |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| www.conandoyleestate.com |

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle KStJ DL (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for A Study in Scarlet, the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Holmes and Dr. Watson. The Sherlock Holmes stories are milestones in the field of crime fiction.

Doyle was a prolific writer; other than Holmes stories, his works include fantasy and science fiction stories about Professor Challenger, and humorous stories about the Napoleonic soldier Brigadier Gerard, as well as plays, romances, poetry, non-fiction, and historical novels. One of Doyle’s early short stories, «J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement» (1884), helped to popularise the mystery of the Mary Celeste.

Name[edit]

Doyle is often referred to as «Sir Arthur Conan Doyle» or «Conan Doyle», implying that «Conan» is part of a compound surname rather than a middle name. His baptism entry in the register of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, gives «Arthur Ignatius Conan» as his given names and «Doyle» as his surname. It also names Michael Conan as his godfather.[1] The catalogues of the British Library and the Library of Congress treat «Doyle» alone as his surname.[2]

Steven Doyle, publisher of The Baker Street Journal, wrote: «Conan was Arthur’s middle name. Shortly after he graduated from high school he began using Conan as a sort of surname. But technically his last name is simply ‘Doyle’.»[3] When knighted, he was gazetted as Doyle, not under the compound Conan Doyle.[4]

Early life[edit]

Title page from Arthur Conan Doyle’s thesis

Doyle was born on 22 May 1859 at 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh, Scotland.[5][6] His father, Charles Altamont Doyle, was born in England, of Irish Catholic descent, and his mother, Mary (née Foley), was Irish Catholic. His parents married in 1855.[7] In 1864 the family scattered because of Charles’s growing alcoholism, and the children were temporarily housed across Edinburgh. Arthur lodged with Mary Burton, the aunt of a friend, at Liberton Bank House on Gilmerton Road, while studying at Newington Academy.[8]

In 1867, the family came together again and lived in squalid tenement flats at 3 Sciennes Place.[9] Doyle’s father died in 1893, in the Crichton Royal, Dumfries, after many years of psychiatric illness.[10][11] Beginning at an early age, throughout his life Doyle wrote letters to his mother, and many of them were preserved.[12]

Supported by wealthy uncles, Doyle was sent to England, to the Jesuit preparatory school Hodder Place, Stonyhurst in Lancashire, at the age of nine (1868–70). He then went on to Stonyhurst College, which he attended until 1875. While Doyle was not unhappy at Stonyhurst, he said he did not have any fond memories of it because the school was run on medieval principles: the only subjects covered were rudiments, rhetoric, Euclidean geometry, algebra, and the classics.[13] Doyle commented later in his life that this academic system could only be excused «on the plea that any exercise, however stupid in itself, forms a sort of mental dumbbell by which one can improve one’s mind».[13] He also found the school harsh, noting that, instead of compassion and warmth, it favoured the threat of corporal punishment and ritual humiliation.[14]

From 1875 to 1876, he was educated at the Jesuit school Stella Matutina in Feldkirch, Austria.[9] His family decided that he would spend a year there in order to perfect his German and broaden his academic horizons.[15] He later rejected the Catholic faith and became an agnostic.[16] One source attributed his drift away from religion to the time he spent in the less strict Austrian school.[14] He also later became a spiritualist mystic.[17]

Medical career[edit]

From 1876 to 1881, Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh Medical School; during this period he spent time working in Aston (then a town in Warwickshire, now part of Birmingham), Sheffield and Ruyton-XI-Towns, Shropshire.[18] Also during this period, he studied practical botany at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh.[19] While studying, Doyle began writing short stories. His earliest extant fiction, «The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe», was unsuccessfully submitted to Blackwood’s Magazine.[9] His first published piece, «The Mystery of Sasassa Valley», a story set in South Africa, was printed in Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal on 6 September 1879.[9][20] On 20 September 1879, he published his first academic article, «Gelsemium as a Poison» in the British Medical Journal,[9][21][22] a study which The Daily Telegraph regarded as potentially useful in a 21st-century murder investigation.[23]

Doyle was the doctor on the Greenland whaler Hope of Peterhead in 1880.[24] On 11 July 1880, John Gray’s Hope and David Gray’s Eclipse met up with the Eira and Leigh Smith. The photographer W. J. A. Grant took a photograph aboard the Eira of Doyle along with Smith, the Gray brothers, and ship’s surgeon William Neale, who were members of the Smith expedition. That expedition explored Franz Josef Land, and led to the naming, on 18 August, of Cape Flora, Bell Island, Nightingale Sound, Gratton («Uncle Joe») Island, and Mabel Island.[25]

After graduating with Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery (M.B. C.M.) degrees from the University of Edinburgh in 1881, he was ship’s surgeon on the SS Mayumba during a voyage to the West African coast.[9] He completed his Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree (an advanced degree beyond the basic medical qualification in the UK) with a dissertation on tabes dorsalis in 1885.[26][27]

In 1882, Doyle partnered with his former classmate George Turnavine Budd in a medical practice in Plymouth, but their relationship proved difficult, and Doyle soon left to set up an independent practice.[9][28] Arriving in Portsmouth in June 1882, with less than £10 (£1100 in 2019[29]) to his name, he set up a medical practice at 1 Bush Villas in Elm Grove, Southsea.[30] The practice was not successful. While waiting for patients, Doyle returned to writing fiction.

Doyle was a staunch supporter of compulsory vaccination and wrote several articles advocating the practice and denouncing the views of anti-vaccinators.[31][32]

In early 1891, Doyle embarked on the study of ophthalmology in Vienna. He had previously studied at the Portsmouth Eye Hospital in order to qualify to perform eye tests and prescribe glasses. Vienna had been suggested by his friend Vernon Morris as a place to spend six months and train to be an eye surgeon. But Doyle found it too difficult to understand the German medical terms being used in his classes in Vienna, and soon quit his studies there. For the rest of his two-month stay in Vienna, he pursued other activities, such as ice skating with his wife Louisa and drinking with Brinsley Richards of the London Times. He also wrote The Doings of Raffles Haw.

After visiting Venice and Milan, he spent a few days in Paris observing Edmund Landolt, an expert on diseases of the eye. Within three months of his departure for Vienna, Doyle returned to London. He opened a small office and consulting room at 2 Upper Wimpole Street, or 2 Devonshire Place as it was then. (There is today a Westminster City Council commemorative plaque over the front door.) He had no patients, according to his autobiography, and his efforts as an ophthalmologist were a failure.[33][34][35]

Literary career[edit]

Sherlock Holmes[edit]

Doyle struggled to find a publisher. His first work featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, A Study in Scarlet, was written in three weeks when he was 27 and was accepted for publication by Ward Lock & Co on 20 November 1886, which gave Doyle £25 (equivalent to £2,900 in 2019) in exchange for all rights to the story. The piece appeared a year later in the Beeton’s Christmas Annual and received good reviews in The Scotsman and the Glasgow Herald.[9]

Holmes was partially modelled on Doyle’s former university teacher Joseph Bell. In 1892, in a letter to Bell, Doyle wrote, «It is most certainly to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes … round the centre of deduction and inference and observation which I have heard you inculcate I have tried to build up a man»,[36] and in his 1924 autobiography, he remarked, «It is no wonder that after the study of such a character [viz., Bell] I used and amplified his methods when in later life I tried to build up a scientific detective who solved cases on his own merits and not through the folly of the criminal.»[37] Robert Louis Stevenson was able to recognise the strong similarity between Joseph Bell and Sherlock Holmes: «My compliments on your very ingenious and very interesting adventures of Sherlock Holmes. … can this be my old friend Joe Bell?»[38] Other authors sometimes suggest additional influences—for instance, Edgar Allan Poe’s character C. Auguste Dupin, who is mentioned, disparagingly, by Holmes in A Study in Scarlet.[39] Dr. (John) Watson owes his surname, but not any other obvious characteristic, to a Portsmouth medical colleague of Doyle’s, Dr. James Watson.[40]

Sherlock Holmes statue in Edinburgh, erected opposite the birthplace of Doyle, which was demolished c. 1970

A sequel to A Study in Scarlet was commissioned, and The Sign of the Four appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine in February 1890, under agreement with the Ward Lock company. Doyle felt grievously exploited by Ward Lock as an author new to the publishing world, and so, after this, he left them.[9] Short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes were published in the Strand Magazine. Doyle wrote the first five Holmes short stories from his office at 2 Upper Wimpole Street (then known as Devonshire Place), which is now marked by a memorial plaque.[41]

Doyle’s attitude towards his most famous creation was ambivalent.[40] In November 1891, he wrote to his mother: «I think of slaying Holmes, … and winding him up for good and all. He takes my mind from better things.» His mother responded, «You won’t! You can’t! You mustn’t!»[42] In an attempt to deflect publishers’ demands for more Holmes stories, he raised his price to a level intended to discourage them, but found they were willing to pay even the large sums he asked.[40] As a result, he became one of the best-paid authors of his time.

Statue of Holmes and the English Church in Meiringen

In December 1893, to dedicate more of his time to his historical novels, Doyle had Holmes and Professor Moriarty plunge to their deaths together down the Reichenbach Falls in the story «The Final Problem». Public outcry, however, led him to feature Holmes in 1901 in the novel The Hound of the Baskervilles. Holmes’s fictional connection with the Reichenbach Falls is celebrated in the nearby town of Meiringen.