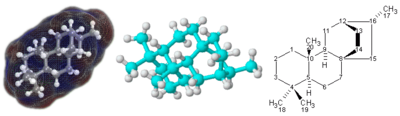

AFM image of 1,5,9-trioxo-13-azatriangulene and its chemical structure.[3]

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion.[4][5][6][7][8] In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and biochemistry, the distinction from ions is dropped and molecule is often used when referring to polyatomic ions.

A molecule may be homonuclear, that is, it consists of atoms of one chemical element, e.g. two atoms in the oxygen molecule (O2); or it may be heteronuclear, a chemical compound composed of more than one element, e.g. water (two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom; H2O). In the kinetic theory of gases, the term molecule is often used for any gaseous particle regardless of its composition. This relaxes the requirement that a molecule contains two or more atoms, since the noble gases are individual atoms.[9] Atoms and complexes connected by non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds or ionic bonds, are typically not considered single molecules.[10]

Concepts similar to molecules have been discussed since ancient times, but modern investigation into the nature of molecules and their bonds began in the 17th century. Refined over time by scientists such as Robert Boyle, Amedeo Avogadro, Jean Perrin, and Linus Pauling, the study of molecules is today known as molecular physics or molecular chemistry.

Etymology

According to Merriam-Webster and the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word «molecule» derives from the Latin «moles» or small unit of mass. The word is derived from French molécule (1678), from New Latin molecula, diminutive of Latin moles «mass, barrier». The word, which until the late 18th century was used only in Latin form, became popular after being used in works of philosophy by Descartes.[11][12]

History

The definition of the molecule has evolved as knowledge of the structure of molecules has increased. Earlier definitions were less precise, defining molecules as the smallest particles of pure chemical substances that still retain their composition and chemical properties.[13] This definition often breaks down since many substances in ordinary experience, such as rocks, salts, and metals, are composed of large crystalline networks of chemically bonded atoms or ions, but are not made of discrete molecules.

The modern concept of molecules can be traced back towards pre-scientific and Greek philosophers such as Leucippus and Democritus who argued that all the universe is composed of atoms and voids. Circa 450 BC Empedocles imagined fundamental elements (fire (), earth (

), air (

), and water (

)) and «forces» of attraction and repulsion allowing the elements to interact.

A fifth element, the incorruptible quintessence aether, was considered to be the fundamental building block of the heavenly bodies. The viewpoint of Leucippus and Empedocles, along with the aether, was accepted by Aristotle and passed to medieval and renaissance Europe.

In a more concrete manner, however, the concept of aggregates or units of bonded atoms, i.e. «molecules», traces its origins to Robert Boyle’s 1661 hypothesis, in his famous treatise The Sceptical Chymist, that matter is composed of clusters of particles and that chemical change results from the rearrangement of the clusters. Boyle argued that matter’s basic elements consisted of various sorts and sizes of particles, called «corpuscles», which were capable of arranging themselves into groups. In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of «ultimate» particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds. If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and similarly for the other combinations of ultimate particles.

Amedeo Avogadro created the word «molecule».[14] His 1811 paper «Essay on Determining the Relative Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies», he essentially states, i.e. according to Partington’s A Short History of Chemistry, that:[15]

The smallest particles of gases are not necessarily simple atoms, but are made up of a certain number of these atoms united by attraction to form a single molecule.

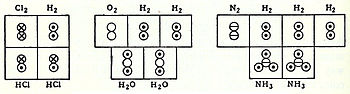

In coordination with these concepts, in 1833 the French chemist Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin presented a clear account of Avogadro’s hypothesis,[16] regarding atomic weights, by making use of «volume diagrams», which clearly show both semi-correct molecular geometries, such as a linear water molecule, and correct molecular formulas, such as H2O:

Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin’s volume diagrams of molecules in the gas phase (1833)

In 1917, an unknown American undergraduate chemical engineer named Linus Pauling was learning the Dalton hook-and-eye bonding method, which was the mainstream description of bonds between atoms at the time. Pauling, however, wasn’t satisfied with this method and looked to the newly emerging field of quantum physics for a new method. In 1926, French physicist Jean Perrin received the Nobel Prize in physics for proving, conclusively, the existence of molecules. He did this by calculating Avogadro’s number using three different methods, all involving liquid phase systems. First, he used a gamboge soap-like emulsion, second by doing experimental work on Brownian motion, and third by confirming Einstein’s theory of particle rotation in the liquid phase.[17]

In 1927, the physicists Fritz London and Walter Heitler applied the new quantum mechanics to the deal with the saturable, nondynamic forces of attraction and repulsion, i.e., exchange forces, of the hydrogen molecule. Their valence bond treatment of this problem, in their joint paper,[18] was a landmark in that it brought chemistry under quantum mechanics. Their work was an influence on Pauling, who had just received his doctorate and visited Heitler and London in Zürich on a Guggenheim Fellowship.

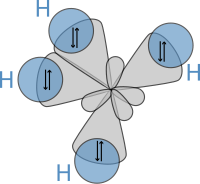

Subsequently, in 1931, building on the work of Heitler and London and on theories found in Lewis’ famous article, Pauling published his ground-breaking article «The Nature of the Chemical Bond»[19] in which he used quantum mechanics to calculate properties and structures of molecules, such as angles between bonds and rotation about bonds. On these concepts, Pauling developed hybridization theory to account for bonds in molecules such as CH4, in which four sp³ hybridised orbitals are overlapped by hydrogen’s 1s orbital, yielding four sigma (σ) bonds. The four bonds are of the same length and strength, which yields a molecular structure as shown below:

A schematic presentation of hybrid orbitals overlapping hydrogens’ s orbitals

Molecular science

The science of molecules is called molecular chemistry or molecular physics, depending on whether the focus is on chemistry or physics. Molecular chemistry deals with the laws governing the interaction between molecules that results in the formation and breakage of chemical bonds, while molecular physics deals with the laws governing their structure and properties. In practice, however, this distinction is vague. In molecular sciences, a molecule consists of a stable system (bound state) composed of two or more atoms. Polyatomic ions may sometimes be usefully thought of as electrically charged molecules. The term unstable molecule is used for very reactive species, i.e., short-lived assemblies (resonances) of electrons and nuclei, such as radicals, molecular ions, Rydberg molecules, transition states, van der Waals complexes, or systems of colliding atoms as in Bose–Einstein condensate.

Prevalence

Molecules as components of matter are common. They also make up most of the oceans and atmosphere. Most organic substances are molecules. The substances of life are molecules, e.g. proteins, the amino acids of which they are composed, the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), sugars, carbohydrates, fats, and vitamins. The nutrient minerals are generally ionic compounds, thus they are not molecules, e.g. iron sulfate.

However, the majority of familiar solid substances on Earth are made partly or completely of crystals or ionic compounds, which are not made of molecules. These include all of the minerals that make up the substance of the Earth, sand, clay, pebbles, rocks, boulders, bedrock, the molten interior, and the core of the Earth. All of these contain many chemical bonds, but are not made of identifiable molecules.

No typical molecule can be defined for salts nor for covalent crystals, although these are often composed of repeating unit cells that extend either in a plane, e.g. graphene; or three-dimensionally e.g. diamond, quartz, sodium chloride. The theme of repeated unit-cellular-structure also holds for most metals which are condensed phases with metallic bonding. Thus solid metals are not made of molecules. In glasses, which are solids that exist in a vitreous disordered state, the atoms are held together by chemical bonds with no presence of any definable molecule, nor any of the regularity of repeating unit-cellular-structure that characterizes salts, covalent crystals, and metals.

Bonding

Molecules are generally held together by covalent bonding. Several non-metallic elements exist only as molecules in the environment either in compounds or as homonuclear molecules, not as free atoms: for example, hydrogen.

While some people say a metallic crystal can be considered a single giant molecule held together by metallic bonding,[20] others point out that metals behave very differently than molecules.[21]

Covalent

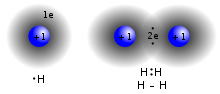

A covalent bond forming H2 (right) where two hydrogen atoms share the two electrons

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are termed shared pairs or bonding pairs, and the stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is termed covalent bonding.[22]

Ionic

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bond that involves the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, and is the primary interaction occurring in ionic compounds. The ions are atoms that have lost one or more electrons (termed cations) and atoms that have gained one or more electrons (termed anions).[23] This transfer of electrons is termed electrovalence in contrast to covalence. In the simplest case, the cation is a metal atom and the anion is a nonmetal atom, but these ions can be of a more complicated nature, e.g. molecular ions like NH4+ or SO42−. At normal temperatures and pressures, ionic bonding mostly creates solids (or occasionally liquids) without separate identifiable molecules, but the vaporization/sublimation of such materials does produce separate molecules where electrons are still transferred fully enough for the bonds to be considered ionic rather than covalent.

Molecular size

Most molecules are far too small to be seen with the naked eye, although molecules of many polymers can reach macroscopic sizes, including biopolymers such as DNA. Molecules commonly used as building blocks for organic synthesis have a dimension of a few angstroms (Å) to several dozen Å, or around one billionth of a meter. Single molecules cannot usually be observed by light (as noted above), but small molecules and even the outlines of individual atoms may be traced in some circumstances by use of an atomic force microscope. Some of the largest molecules are macromolecules or supermolecules.

The smallest molecule is the diatomic hydrogen (H2), with a bond length of 0.74 Å.[24]

Effective molecular radius is the size a molecule displays in solution.[25][26]

The table of permselectivity for different substances contains examples.

Molecular formulas

Chemical formula types

The chemical formula for a molecule uses one line of chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, such as parentheses, dashes, brackets, and plus (+) and minus (−) signs. These are limited to one typographic line of symbols, which may include subscripts and superscripts.

A compound’s empirical formula is a very simple type of chemical formula.[27] It is the simplest integer ratio of the chemical elements that constitute it.[28] For example, water is always composed of a 2:1 ratio of hydrogen to oxygen atoms, and ethanol (ethyl alcohol) is always composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen in a 2:6:1 ratio. However, this does not determine the kind of molecule uniquely – dimethyl ether has the same ratios as ethanol, for instance. Molecules with the same atoms in different arrangements are called isomers. Also carbohydrates, for example, have the same ratio (carbon:hydrogen:oxygen= 1:2:1) (and thus the same empirical formula) but different total numbers of atoms in the molecule.

The molecular formula reflects the exact number of atoms that compose the molecule and so characterizes different molecules. However different isomers can have the same atomic composition while being different molecules.

The empirical formula is often the same as the molecular formula but not always. For example, the molecule acetylene has molecular formula C2H2, but the simplest integer ratio of elements is CH.

The molecular mass can be calculated from the chemical formula and is expressed in conventional atomic mass units equal to 1/12 of the mass of a neutral carbon-12 (12C isotope) atom. For network solids, the term formula unit is used in stoichiometric calculations.

Structural formula

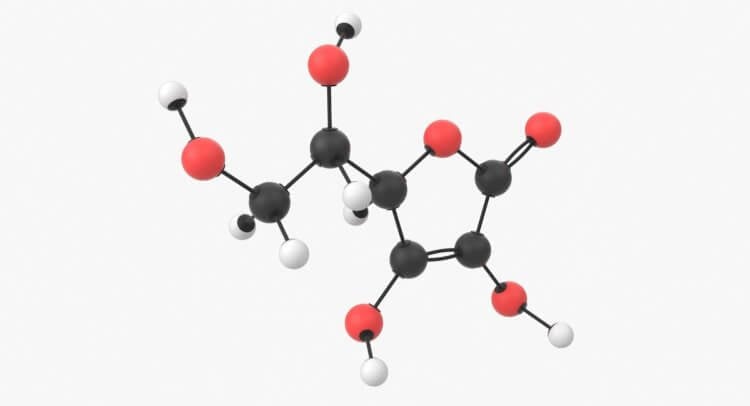

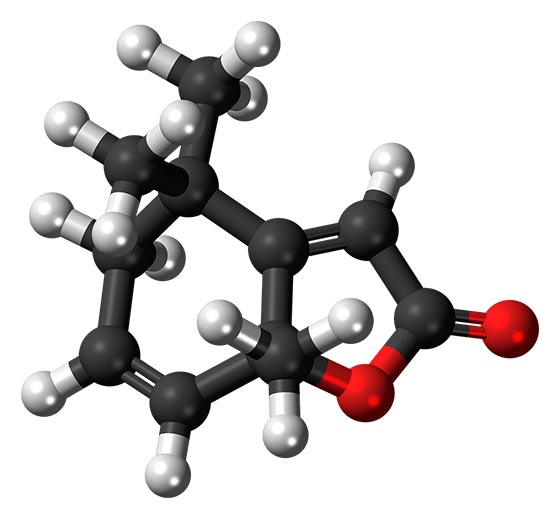

3D (left and center) and 2D (right) representations of the terpenoid molecule atisane

For molecules with a complicated 3-dimensional structure, especially involving atoms bonded to four different substituents, a simple molecular formula or even semi-structural chemical formula may not be enough to completely specify the molecule. In this case, a graphical type of formula called a structural formula may be needed. Structural formulas may in turn be represented with a one-dimensional chemical name, but such chemical nomenclature requires many words and terms which are not part of chemical formulas.

Molecular geometry

Molecules have fixed equilibrium geometries—bond lengths and angles— about which they continuously oscillate through vibrational and rotational motions. A pure substance is composed of molecules with the same average geometrical structure. The chemical formula and the structure of a molecule are the two important factors that determine its properties, particularly its reactivity. Isomers share a chemical formula but normally have very different properties because of their different structures. Stereoisomers, a particular type of isomer, may have very similar physico-chemical properties and at the same time different biochemical activities.

Molecular spectroscopy

Hydrogen can be removed from individual H2TPP molecules by applying excess voltage to the tip of a scanning tunneling microscope (STM, a); this removal alters the current-voltage (I-V) curves of TPP molecules, measured using the same STM tip, from diode like (red curve in b) to resistor like (green curve). Image (c) shows a row of TPP, H2TPP and TPP molecules. While scanning image (d), excess voltage was applied to H2TPP at the black dot, which instantly removed hydrogen, as shown in the bottom part of (d) and in the rescan image (e). Such manipulations can be used in single-molecule electronics.[30]

Molecular spectroscopy deals with the response (spectrum) of molecules interacting with probing signals of known energy (or frequency, according to Planck’s formula). Molecules have quantized energy levels that can be analyzed by detecting the molecule’s energy exchange through absorbance or emission.[31]

Spectroscopy does not generally refer to diffraction studies where particles such as neutrons, electrons, or high energy X-rays interact with a regular arrangement of molecules (as in a crystal).

Microwave spectroscopy commonly measures changes in the rotation of molecules, and can be used to identify molecules in outer space. Infrared spectroscopy measures the vibration of molecules, including stretching, bending or twisting motions. It is commonly used to identify the kinds of bonds or functional groups in molecules. Changes in the arrangements of electrons yield absorption or emission lines in ultraviolet, visible or near infrared light, and result in colour. Nuclear resonance spectroscopy measures the environment of particular nuclei in the molecule, and can be used to characterise the numbers of atoms in different positions in a molecule.

Theoretical aspects

The study of molecules by molecular physics and theoretical chemistry is largely based on quantum mechanics and is essential for the understanding of the chemical bond. The simplest of molecules is the hydrogen molecule-ion, H2+, and the simplest of all the chemical bonds is the one-electron bond. H2+ is composed of two positively charged protons and one negatively charged electron, which means that the Schrödinger equation for the system can be solved more easily due to the lack of electron–electron repulsion. With the development of fast digital computers, approximate solutions for more complicated molecules became possible and are one of the main aspects of computational chemistry.

When trying to define rigorously whether an arrangement of atoms is sufficiently stable to be considered a molecule, IUPAC suggests that it «must correspond to a depression on the potential energy surface that is deep enough to confine at least one vibrational state».[4] This definition does not depend on the nature of the interaction between the atoms, but only on the strength of the interaction. In fact, it includes weakly bound species that would not traditionally be considered molecules, such as the helium dimer, He2, which has one vibrational bound state[32] and is so loosely bound that it is only likely to be observed at very low temperatures.

Whether or not an arrangement of atoms is sufficiently stable to be considered a molecule is inherently an operational definition. Philosophically, therefore, a molecule is not a fundamental entity (in contrast, for instance, to an elementary particle); rather, the concept of a molecule is the chemist’s way of making a useful statement about the strengths of atomic-scale interactions in the world that we observe.

See also

- Atom

- Chemical polarity

- Chemical structure

- Covalent bond

- Diatomic molecule

- List of compounds

- List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

- Molecular biology

- Molecular design software

- Molecular engineering

- Molecular geometry

- Molecular Hamiltonian

- Molecular ion

- Molecular modelling

- Molecular promiscuity

- Molecular orbital

- Non-covalent bonding

- Periodic systems of small molecules

- Small molecule

- Comparison of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Van der Waals molecule

- World Wide Molecular Matrix

References

- ^ Iwata, Kota; Yamazaki, Shiro; Mutombo, Pingo; Hapala, Prokop; Ondráček, Martin; Jelínek, Pavel; Sugimoto, Yoshiaki (2015). «Chemical structure imaging of a single molecule by atomic force microscopy at room temperature». Nature Communications. 6: 7766. Bibcode:2015NatCo…6.7766I. doi:10.1038/ncomms8766. PMC 4518281. PMID 26178193.

- ^ Dinca, L.E.; De Marchi, F.; MacLeod, J.M.; Lipton-Duffin, J.; Gatti, R.; Ma, D.; Perepichka, D.F.; Rosei, F. (2015). «Pentacene on Ni(111): Room-temperature molecular packing and temperature-activated conversion to graphene». Nanoscale. 7 (7): 3263–9. Bibcode:2015Nanos…7.3263D. doi:10.1039/C4NR07057G. PMID 25619890.

- ^ Hapala, Prokop; Švec, Martin; Stetsovych, Oleksandr; Van Der Heijden, Nadine J.; Ondráček, Martin; Van Der Lit, Joost; Mutombo, Pingo; Swart, Ingmar; Jelínek, Pavel (2016). «Mapping the electrostatic force field of single molecules from high-resolution scanning probe images». Nature Communications. 7: 11560. Bibcode:2016NatCo…711560H. doi:10.1038/ncomms11560. PMC 4894979. PMID 27230940.

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Molecule». doi:10.1351/goldbook.M04002

- ^ Ebbin, Darrell D. (1990). General Chemistry (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-395-43302-7.

- ^ Brown, T.L.; Kenneth C. Kemp; Theodore L. Brown; Harold Eugene LeMay; Bruce Edward Bursten (2003). Chemistry – the Central Science (9th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-066997-1.

- ^ Chang, Raymond (1998). Chemistry (6th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-115221-1.

- ^ Zumdahl, Steven S. (1997). Chemistry (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-669-41794-4.

- ^ Chandra, Sulekh (2005). Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry. New Age Publishers. ISBN 978-81-224-1512-4.

- ^ «Molecule». Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «molecule». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ «molecule». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Molecule Definition Archived 13 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Frostburg State University)

- ^ Ley, Willy (June 1966). «The Re-Designed Solar System». For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- ^ Avogadro, Amedeo (1811). «Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies». Journal de Physique. 73: 58–76. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Seymour H. Mauskopf (1969). «The Atomic Structural Theories of Ampère and Gaudin: Molecular Speculation and Avogadro’s Hypothesis». Isis. 60 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1086/350449. JSTOR 229022. S2CID 143759556.

- ^ Perrin, Jean, B. (1926). Discontinuous Structure of Matter Archived 29 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Nobel Lecture, December 11.

- ^ Heitler, Walter; London, Fritz (1927). «Wechselwirkung neutraler Atome und homöopolare Bindung nach der Quantenmechanik». Zeitschrift für Physik. 44 (6–7): 455–472. Bibcode:1927ZPhy…44..455H. doi:10.1007/BF01397394. S2CID 119739102.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1931). «The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 53 (4): 1367–1400. doi:10.1021/ja01355a027.

- ^ Harry, B. Gray. Chemical Bonds: An Introduction to Atomic and Molecular Structure (PDF). pp. 210–211. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ «How many gold atoms make gold metal?». phys.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Brad Williamson; Robin J. Heyden (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-250882-7. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Campbell, Flake C. (2008). Elements of Metallurgy and Engineering Alloys. ASM International. ISBN 978-1-61503-058-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Roger L. DeKock; Harry B. Gray; Harry B. Gray (1989). Chemical structure and bonding. University Science Books. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-935702-61-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Chang RL; Deen WM; Robertson CR; Brenner BM (1975). «Permselectivity of the glomerular capillary wall: III. Restricted transport of polyanions». Kidney Int. 8 (4): 212–218. doi:10.1038/ki.1975.104. PMID 1202253.

- ^ Chang RL; Ueki IF; Troy JL; Deen WM; Robertson CR; Brenner BM (1975). «Permselectivity of the glomerular capillary wall to macromolecules. II. Experimental studies in rats using neutral dextran». Biophys. J. 15 (9): 887–906. Bibcode:1975BpJ….15..887C. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(75)85863-2. PMC 1334749. PMID 1182263.

- ^ Wink, Donald J.; Fetzer-Gislason, Sharon; McNicholas, Sheila (2003). The Practice of Chemistry. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-4871-7. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ «ChemTeam: Empirical Formula». www.chemteam.info. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Hirsch, Brandon E.; Lee, Semin; Qiao, Bo; Chen, Chun-Hsing; McDonald, Kevin P.; Tait, Steven L.; Flood, Amar H. (2014). «Anion-induced dimerization of 5-fold symmetric cyanostars in 3D crystalline solids and 2D self-assembled crystals». Chemical Communications. 50 (69): 9827–30. doi:10.1039/C4CC03725A. PMID 25080328. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Zoldan, V. C.; Faccio, R; Pasa, A.A. (2015). «N and p type character of single molecule diodes». Scientific Reports. 5: 8350. Bibcode:2015NatSR…5E8350Z. doi:10.1038/srep08350. PMC 4322354. PMID 25666850.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Spectroscopy». doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05848

- ^ Anderson JB (May 2004). «Comment on «An exact quantum Monte Carlo calculation of the helium-helium intermolecular potential» [J. Chem. Phys. 115, 4546 (2001)]». J Chem Phys. 120 (20): 9886–7. Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.9886A. doi:10.1063/1.1704638. PMID 15268005.

External links

- Molecule of the Month – School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

AFM image of 1,5,9-trioxo-13-azatriangulene and its chemical structure.[3]

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion.[4][5][6][7][8] In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and biochemistry, the distinction from ions is dropped and molecule is often used when referring to polyatomic ions.

A molecule may be homonuclear, that is, it consists of atoms of one chemical element, e.g. two atoms in the oxygen molecule (O2); or it may be heteronuclear, a chemical compound composed of more than one element, e.g. water (two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom; H2O). In the kinetic theory of gases, the term molecule is often used for any gaseous particle regardless of its composition. This relaxes the requirement that a molecule contains two or more atoms, since the noble gases are individual atoms.[9] Atoms and complexes connected by non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds or ionic bonds, are typically not considered single molecules.[10]

Concepts similar to molecules have been discussed since ancient times, but modern investigation into the nature of molecules and their bonds began in the 17th century. Refined over time by scientists such as Robert Boyle, Amedeo Avogadro, Jean Perrin, and Linus Pauling, the study of molecules is today known as molecular physics or molecular chemistry.

Etymology

According to Merriam-Webster and the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word «molecule» derives from the Latin «moles» or small unit of mass. The word is derived from French molécule (1678), from New Latin molecula, diminutive of Latin moles «mass, barrier». The word, which until the late 18th century was used only in Latin form, became popular after being used in works of philosophy by Descartes.[11][12]

History

The definition of the molecule has evolved as knowledge of the structure of molecules has increased. Earlier definitions were less precise, defining molecules as the smallest particles of pure chemical substances that still retain their composition and chemical properties.[13] This definition often breaks down since many substances in ordinary experience, such as rocks, salts, and metals, are composed of large crystalline networks of chemically bonded atoms or ions, but are not made of discrete molecules.

The modern concept of molecules can be traced back towards pre-scientific and Greek philosophers such as Leucippus and Democritus who argued that all the universe is composed of atoms and voids. Circa 450 BC Empedocles imagined fundamental elements (fire (), earth (

), air (

), and water (

)) and «forces» of attraction and repulsion allowing the elements to interact.

A fifth element, the incorruptible quintessence aether, was considered to be the fundamental building block of the heavenly bodies. The viewpoint of Leucippus and Empedocles, along with the aether, was accepted by Aristotle and passed to medieval and renaissance Europe.

In a more concrete manner, however, the concept of aggregates or units of bonded atoms, i.e. «molecules», traces its origins to Robert Boyle’s 1661 hypothesis, in his famous treatise The Sceptical Chymist, that matter is composed of clusters of particles and that chemical change results from the rearrangement of the clusters. Boyle argued that matter’s basic elements consisted of various sorts and sizes of particles, called «corpuscles», which were capable of arranging themselves into groups. In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of «ultimate» particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds. If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and similarly for the other combinations of ultimate particles.

Amedeo Avogadro created the word «molecule».[14] His 1811 paper «Essay on Determining the Relative Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies», he essentially states, i.e. according to Partington’s A Short History of Chemistry, that:[15]

The smallest particles of gases are not necessarily simple atoms, but are made up of a certain number of these atoms united by attraction to form a single molecule.

In coordination with these concepts, in 1833 the French chemist Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin presented a clear account of Avogadro’s hypothesis,[16] regarding atomic weights, by making use of «volume diagrams», which clearly show both semi-correct molecular geometries, such as a linear water molecule, and correct molecular formulas, such as H2O:

Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin’s volume diagrams of molecules in the gas phase (1833)

In 1917, an unknown American undergraduate chemical engineer named Linus Pauling was learning the Dalton hook-and-eye bonding method, which was the mainstream description of bonds between atoms at the time. Pauling, however, wasn’t satisfied with this method and looked to the newly emerging field of quantum physics for a new method. In 1926, French physicist Jean Perrin received the Nobel Prize in physics for proving, conclusively, the existence of molecules. He did this by calculating Avogadro’s number using three different methods, all involving liquid phase systems. First, he used a gamboge soap-like emulsion, second by doing experimental work on Brownian motion, and third by confirming Einstein’s theory of particle rotation in the liquid phase.[17]

In 1927, the physicists Fritz London and Walter Heitler applied the new quantum mechanics to the deal with the saturable, nondynamic forces of attraction and repulsion, i.e., exchange forces, of the hydrogen molecule. Their valence bond treatment of this problem, in their joint paper,[18] was a landmark in that it brought chemistry under quantum mechanics. Their work was an influence on Pauling, who had just received his doctorate and visited Heitler and London in Zürich on a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Subsequently, in 1931, building on the work of Heitler and London and on theories found in Lewis’ famous article, Pauling published his ground-breaking article «The Nature of the Chemical Bond»[19] in which he used quantum mechanics to calculate properties and structures of molecules, such as angles between bonds and rotation about bonds. On these concepts, Pauling developed hybridization theory to account for bonds in molecules such as CH4, in which four sp³ hybridised orbitals are overlapped by hydrogen’s 1s orbital, yielding four sigma (σ) bonds. The four bonds are of the same length and strength, which yields a molecular structure as shown below:

A schematic presentation of hybrid orbitals overlapping hydrogens’ s orbitals

Molecular science

The science of molecules is called molecular chemistry or molecular physics, depending on whether the focus is on chemistry or physics. Molecular chemistry deals with the laws governing the interaction between molecules that results in the formation and breakage of chemical bonds, while molecular physics deals with the laws governing their structure and properties. In practice, however, this distinction is vague. In molecular sciences, a molecule consists of a stable system (bound state) composed of two or more atoms. Polyatomic ions may sometimes be usefully thought of as electrically charged molecules. The term unstable molecule is used for very reactive species, i.e., short-lived assemblies (resonances) of electrons and nuclei, such as radicals, molecular ions, Rydberg molecules, transition states, van der Waals complexes, or systems of colliding atoms as in Bose–Einstein condensate.

Prevalence

Molecules as components of matter are common. They also make up most of the oceans and atmosphere. Most organic substances are molecules. The substances of life are molecules, e.g. proteins, the amino acids of which they are composed, the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), sugars, carbohydrates, fats, and vitamins. The nutrient minerals are generally ionic compounds, thus they are not molecules, e.g. iron sulfate.

However, the majority of familiar solid substances on Earth are made partly or completely of crystals or ionic compounds, which are not made of molecules. These include all of the minerals that make up the substance of the Earth, sand, clay, pebbles, rocks, boulders, bedrock, the molten interior, and the core of the Earth. All of these contain many chemical bonds, but are not made of identifiable molecules.

No typical molecule can be defined for salts nor for covalent crystals, although these are often composed of repeating unit cells that extend either in a plane, e.g. graphene; or three-dimensionally e.g. diamond, quartz, sodium chloride. The theme of repeated unit-cellular-structure also holds for most metals which are condensed phases with metallic bonding. Thus solid metals are not made of molecules. In glasses, which are solids that exist in a vitreous disordered state, the atoms are held together by chemical bonds with no presence of any definable molecule, nor any of the regularity of repeating unit-cellular-structure that characterizes salts, covalent crystals, and metals.

Bonding

Molecules are generally held together by covalent bonding. Several non-metallic elements exist only as molecules in the environment either in compounds or as homonuclear molecules, not as free atoms: for example, hydrogen.

While some people say a metallic crystal can be considered a single giant molecule held together by metallic bonding,[20] others point out that metals behave very differently than molecules.[21]

Covalent

A covalent bond forming H2 (right) where two hydrogen atoms share the two electrons

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are termed shared pairs or bonding pairs, and the stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is termed covalent bonding.[22]

Ionic

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bond that involves the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, and is the primary interaction occurring in ionic compounds. The ions are atoms that have lost one or more electrons (termed cations) and atoms that have gained one or more electrons (termed anions).[23] This transfer of electrons is termed electrovalence in contrast to covalence. In the simplest case, the cation is a metal atom and the anion is a nonmetal atom, but these ions can be of a more complicated nature, e.g. molecular ions like NH4+ or SO42−. At normal temperatures and pressures, ionic bonding mostly creates solids (or occasionally liquids) without separate identifiable molecules, but the vaporization/sublimation of such materials does produce separate molecules where electrons are still transferred fully enough for the bonds to be considered ionic rather than covalent.

Molecular size

Most molecules are far too small to be seen with the naked eye, although molecules of many polymers can reach macroscopic sizes, including biopolymers such as DNA. Molecules commonly used as building blocks for organic synthesis have a dimension of a few angstroms (Å) to several dozen Å, or around one billionth of a meter. Single molecules cannot usually be observed by light (as noted above), but small molecules and even the outlines of individual atoms may be traced in some circumstances by use of an atomic force microscope. Some of the largest molecules are macromolecules or supermolecules.

The smallest molecule is the diatomic hydrogen (H2), with a bond length of 0.74 Å.[24]

Effective molecular radius is the size a molecule displays in solution.[25][26]

The table of permselectivity for different substances contains examples.

Molecular formulas

Chemical formula types

The chemical formula for a molecule uses one line of chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, such as parentheses, dashes, brackets, and plus (+) and minus (−) signs. These are limited to one typographic line of symbols, which may include subscripts and superscripts.

A compound’s empirical formula is a very simple type of chemical formula.[27] It is the simplest integer ratio of the chemical elements that constitute it.[28] For example, water is always composed of a 2:1 ratio of hydrogen to oxygen atoms, and ethanol (ethyl alcohol) is always composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen in a 2:6:1 ratio. However, this does not determine the kind of molecule uniquely – dimethyl ether has the same ratios as ethanol, for instance. Molecules with the same atoms in different arrangements are called isomers. Also carbohydrates, for example, have the same ratio (carbon:hydrogen:oxygen= 1:2:1) (and thus the same empirical formula) but different total numbers of atoms in the molecule.

The molecular formula reflects the exact number of atoms that compose the molecule and so characterizes different molecules. However different isomers can have the same atomic composition while being different molecules.

The empirical formula is often the same as the molecular formula but not always. For example, the molecule acetylene has molecular formula C2H2, but the simplest integer ratio of elements is CH.

The molecular mass can be calculated from the chemical formula and is expressed in conventional atomic mass units equal to 1/12 of the mass of a neutral carbon-12 (12C isotope) atom. For network solids, the term formula unit is used in stoichiometric calculations.

Structural formula

3D (left and center) and 2D (right) representations of the terpenoid molecule atisane

For molecules with a complicated 3-dimensional structure, especially involving atoms bonded to four different substituents, a simple molecular formula or even semi-structural chemical formula may not be enough to completely specify the molecule. In this case, a graphical type of formula called a structural formula may be needed. Structural formulas may in turn be represented with a one-dimensional chemical name, but such chemical nomenclature requires many words and terms which are not part of chemical formulas.

Molecular geometry

Molecules have fixed equilibrium geometries—bond lengths and angles— about which they continuously oscillate through vibrational and rotational motions. A pure substance is composed of molecules with the same average geometrical structure. The chemical formula and the structure of a molecule are the two important factors that determine its properties, particularly its reactivity. Isomers share a chemical formula but normally have very different properties because of their different structures. Stereoisomers, a particular type of isomer, may have very similar physico-chemical properties and at the same time different biochemical activities.

Molecular spectroscopy

Hydrogen can be removed from individual H2TPP molecules by applying excess voltage to the tip of a scanning tunneling microscope (STM, a); this removal alters the current-voltage (I-V) curves of TPP molecules, measured using the same STM tip, from diode like (red curve in b) to resistor like (green curve). Image (c) shows a row of TPP, H2TPP and TPP molecules. While scanning image (d), excess voltage was applied to H2TPP at the black dot, which instantly removed hydrogen, as shown in the bottom part of (d) and in the rescan image (e). Such manipulations can be used in single-molecule electronics.[30]

Molecular spectroscopy deals with the response (spectrum) of molecules interacting with probing signals of known energy (or frequency, according to Planck’s formula). Molecules have quantized energy levels that can be analyzed by detecting the molecule’s energy exchange through absorbance or emission.[31]

Spectroscopy does not generally refer to diffraction studies where particles such as neutrons, electrons, or high energy X-rays interact with a regular arrangement of molecules (as in a crystal).

Microwave spectroscopy commonly measures changes in the rotation of molecules, and can be used to identify molecules in outer space. Infrared spectroscopy measures the vibration of molecules, including stretching, bending or twisting motions. It is commonly used to identify the kinds of bonds or functional groups in molecules. Changes in the arrangements of electrons yield absorption or emission lines in ultraviolet, visible or near infrared light, and result in colour. Nuclear resonance spectroscopy measures the environment of particular nuclei in the molecule, and can be used to characterise the numbers of atoms in different positions in a molecule.

Theoretical aspects

The study of molecules by molecular physics and theoretical chemistry is largely based on quantum mechanics and is essential for the understanding of the chemical bond. The simplest of molecules is the hydrogen molecule-ion, H2+, and the simplest of all the chemical bonds is the one-electron bond. H2+ is composed of two positively charged protons and one negatively charged electron, which means that the Schrödinger equation for the system can be solved more easily due to the lack of electron–electron repulsion. With the development of fast digital computers, approximate solutions for more complicated molecules became possible and are one of the main aspects of computational chemistry.

When trying to define rigorously whether an arrangement of atoms is sufficiently stable to be considered a molecule, IUPAC suggests that it «must correspond to a depression on the potential energy surface that is deep enough to confine at least one vibrational state».[4] This definition does not depend on the nature of the interaction between the atoms, but only on the strength of the interaction. In fact, it includes weakly bound species that would not traditionally be considered molecules, such as the helium dimer, He2, which has one vibrational bound state[32] and is so loosely bound that it is only likely to be observed at very low temperatures.

Whether or not an arrangement of atoms is sufficiently stable to be considered a molecule is inherently an operational definition. Philosophically, therefore, a molecule is not a fundamental entity (in contrast, for instance, to an elementary particle); rather, the concept of a molecule is the chemist’s way of making a useful statement about the strengths of atomic-scale interactions in the world that we observe.

See also

- Atom

- Chemical polarity

- Chemical structure

- Covalent bond

- Diatomic molecule

- List of compounds

- List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

- Molecular biology

- Molecular design software

- Molecular engineering

- Molecular geometry

- Molecular Hamiltonian

- Molecular ion

- Molecular modelling

- Molecular promiscuity

- Molecular orbital

- Non-covalent bonding

- Periodic systems of small molecules

- Small molecule

- Comparison of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Van der Waals molecule

- World Wide Molecular Matrix

References

- ^ Iwata, Kota; Yamazaki, Shiro; Mutombo, Pingo; Hapala, Prokop; Ondráček, Martin; Jelínek, Pavel; Sugimoto, Yoshiaki (2015). «Chemical structure imaging of a single molecule by atomic force microscopy at room temperature». Nature Communications. 6: 7766. Bibcode:2015NatCo…6.7766I. doi:10.1038/ncomms8766. PMC 4518281. PMID 26178193.

- ^ Dinca, L.E.; De Marchi, F.; MacLeod, J.M.; Lipton-Duffin, J.; Gatti, R.; Ma, D.; Perepichka, D.F.; Rosei, F. (2015). «Pentacene on Ni(111): Room-temperature molecular packing and temperature-activated conversion to graphene». Nanoscale. 7 (7): 3263–9. Bibcode:2015Nanos…7.3263D. doi:10.1039/C4NR07057G. PMID 25619890.

- ^ Hapala, Prokop; Švec, Martin; Stetsovych, Oleksandr; Van Der Heijden, Nadine J.; Ondráček, Martin; Van Der Lit, Joost; Mutombo, Pingo; Swart, Ingmar; Jelínek, Pavel (2016). «Mapping the electrostatic force field of single molecules from high-resolution scanning probe images». Nature Communications. 7: 11560. Bibcode:2016NatCo…711560H. doi:10.1038/ncomms11560. PMC 4894979. PMID 27230940.

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Molecule». doi:10.1351/goldbook.M04002

- ^ Ebbin, Darrell D. (1990). General Chemistry (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-395-43302-7.

- ^ Brown, T.L.; Kenneth C. Kemp; Theodore L. Brown; Harold Eugene LeMay; Bruce Edward Bursten (2003). Chemistry – the Central Science (9th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-066997-1.

- ^ Chang, Raymond (1998). Chemistry (6th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-115221-1.

- ^ Zumdahl, Steven S. (1997). Chemistry (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-669-41794-4.

- ^ Chandra, Sulekh (2005). Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry. New Age Publishers. ISBN 978-81-224-1512-4.

- ^ «Molecule». Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «molecule». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ «molecule». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Molecule Definition Archived 13 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Frostburg State University)

- ^ Ley, Willy (June 1966). «The Re-Designed Solar System». For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- ^ Avogadro, Amedeo (1811). «Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies». Journal de Physique. 73: 58–76. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Seymour H. Mauskopf (1969). «The Atomic Structural Theories of Ampère and Gaudin: Molecular Speculation and Avogadro’s Hypothesis». Isis. 60 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1086/350449. JSTOR 229022. S2CID 143759556.

- ^ Perrin, Jean, B. (1926). Discontinuous Structure of Matter Archived 29 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Nobel Lecture, December 11.

- ^ Heitler, Walter; London, Fritz (1927). «Wechselwirkung neutraler Atome und homöopolare Bindung nach der Quantenmechanik». Zeitschrift für Physik. 44 (6–7): 455–472. Bibcode:1927ZPhy…44..455H. doi:10.1007/BF01397394. S2CID 119739102.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1931). «The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 53 (4): 1367–1400. doi:10.1021/ja01355a027.

- ^ Harry, B. Gray. Chemical Bonds: An Introduction to Atomic and Molecular Structure (PDF). pp. 210–211. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ «How many gold atoms make gold metal?». phys.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Brad Williamson; Robin J. Heyden (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-250882-7. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Campbell, Flake C. (2008). Elements of Metallurgy and Engineering Alloys. ASM International. ISBN 978-1-61503-058-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Roger L. DeKock; Harry B. Gray; Harry B. Gray (1989). Chemical structure and bonding. University Science Books. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-935702-61-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Chang RL; Deen WM; Robertson CR; Brenner BM (1975). «Permselectivity of the glomerular capillary wall: III. Restricted transport of polyanions». Kidney Int. 8 (4): 212–218. doi:10.1038/ki.1975.104. PMID 1202253.

- ^ Chang RL; Ueki IF; Troy JL; Deen WM; Robertson CR; Brenner BM (1975). «Permselectivity of the glomerular capillary wall to macromolecules. II. Experimental studies in rats using neutral dextran». Biophys. J. 15 (9): 887–906. Bibcode:1975BpJ….15..887C. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(75)85863-2. PMC 1334749. PMID 1182263.

- ^ Wink, Donald J.; Fetzer-Gislason, Sharon; McNicholas, Sheila (2003). The Practice of Chemistry. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-4871-7. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ «ChemTeam: Empirical Formula». www.chemteam.info. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Hirsch, Brandon E.; Lee, Semin; Qiao, Bo; Chen, Chun-Hsing; McDonald, Kevin P.; Tait, Steven L.; Flood, Amar H. (2014). «Anion-induced dimerization of 5-fold symmetric cyanostars in 3D crystalline solids and 2D self-assembled crystals». Chemical Communications. 50 (69): 9827–30. doi:10.1039/C4CC03725A. PMID 25080328. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Zoldan, V. C.; Faccio, R; Pasa, A.A. (2015). «N and p type character of single molecule diodes». Scientific Reports. 5: 8350. Bibcode:2015NatSR…5E8350Z. doi:10.1038/srep08350. PMC 4322354. PMID 25666850.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Spectroscopy». doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05848

- ^ Anderson JB (May 2004). «Comment on «An exact quantum Monte Carlo calculation of the helium-helium intermolecular potential» [J. Chem. Phys. 115, 4546 (2001)]». J Chem Phys. 120 (20): 9886–7. Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.9886A. doi:10.1063/1.1704638. PMID 15268005.

External links

- Molecule of the Month – School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

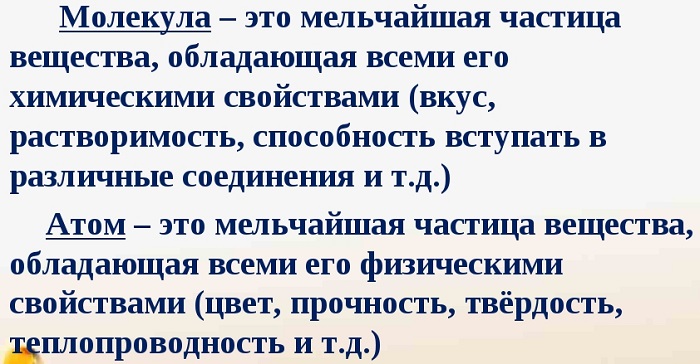

Одним из основополагающих понятий современной науки является понятие молекулы. Его введение европейскими учеными в 1860 г. дало толчок к развитию не только химии и физики, но и других естественных наук.

Молекулой, в наиболее общем определении, называется частица, образованная из нескольких (двух или более) атомов, объединенных между собой ковалентными связями. Она не имеет электрического заряда, все электроны в её составе имеют пару.

Молекулы, несущие заряд, называются ионами, неспаренные электроны – радикалами. Качественный и количественный состав их стабилен. Количество ядер атомов, электронов и их взаимное расположение позволяют отличать молекулы разных веществ друг от друга.

Что такое молекула в физике

В физике этим понятием оперируют при изучении свойств разных сред (газы, жидкости) и твердых тел.

Также их свойствами объясняются явления диффузии, теплопроводности и вязкость веществ.

Что такое молекула в химии

Учение о молекулах для химической науки является одним из самых главных. Именно химические исследования дали важнейшие сведения о составе и свойствах этой мельчайшей единицы вещества.

При прохождении химического превращения молекулы обмениваются атомами, распадаются. Поэтому знания о строении и состоянии этих частиц лежат в основе изучения химии веществ и их превращений.

На основании знаний о проходящей химической реакции можно предсказать строение молекул веществ, в ней участвующих. Противоположное заключение тоже будет верным: на основании сведений о строении молекулы вещества реально предсказать его поведение во время химической реакции.

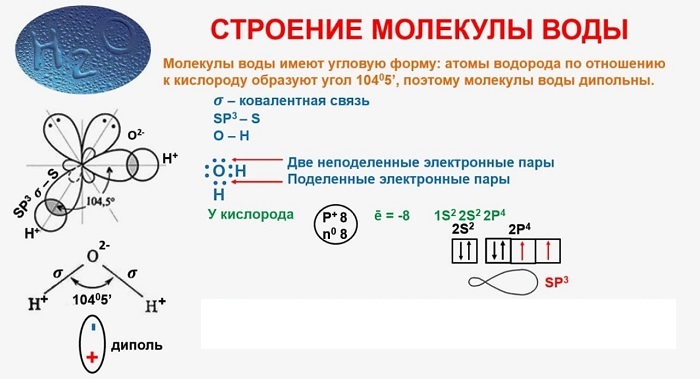

Строение молекулы

Понятие о строении включает геометрическую структуру и распределение электронной плотности.

В качестве примера рассмотрим строение наименьшей частицы воды.

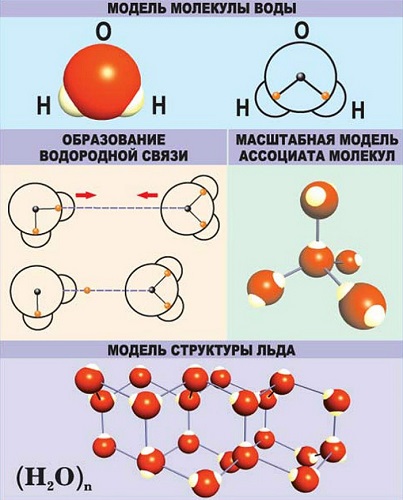

Существует несколько способов взаимодействия атомов. Основным способом являются химические связи, благодаря им поддерживается стабильное существование молекул. Прочие (неосновные) взаимодействия происходят между теми атомами, которые не связаны непосредственно.

Виды химической связи:

-

Металлическая — ядра атомов металлов, расположенные в узлах кристаллических решёток, объединены общим облаком электронов.

-

Водородная — основана на способности атома водорода образовывать дополнительную связь при смещении от него электронной плотности.

-

Ионная — имеет электрическую природу. Сильно поляризована. Возникает при притяжении ионов, несущих противоположный заряд.

-

Ковалентная — может быть полярной и неполярной. Образуется за счет пары электронов, совместно принадлежащей двум атомам. Отличается наибольшей устойчивостью и энергетической емкостью.

Связи характеризуются следующими показателями:

-

длина – степень удаления друг от друга ядер атомов, образовавших связь;

-

энергия – сила, прилагаемая для разрушения связи;

-

полярность – смещение электронного облака к одному из атомов;

-

порядок или кратность – количество пар электронов, образовавших связь.

Строение молекул условно отражается структурными формулами. Основные взаимодействия атомов, при составлении таких формул, отображается черточками. В таких формулах связи образуют неразрывную цепь и иллюстрируют валентности образовавших их элементов (атомов).

Структурные формулы также отражают то, как выглядит молекула (линейная, циклическая, наличие радикалов и т. д.).

Строение частицы вещества активно изучается. Для этого используют различные экспериментальные и теоретические методы. К экспериментальным относят рентгеновский структурный анализ, спектроскопия, массспектрометрия и др. К теоретическим — расчётные методы квантовой химии.

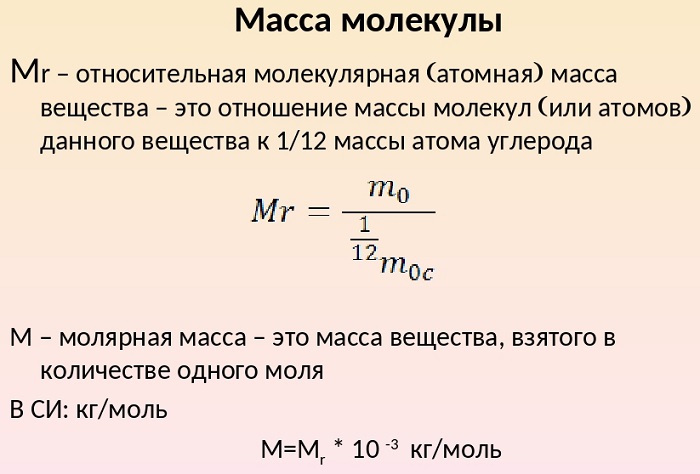

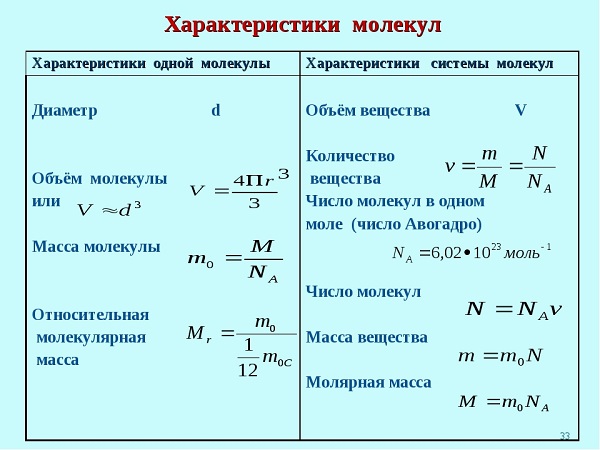

Масса (размер) молекулы

В зависимости о количества ядер атомов, входящих в их состав, можно выделить молекулы двухатомные, трехатомные и т. д.

В том случае, если количество атомов велико, молекула носит название макромолекулы.

Путем сложения масс атомов, входящих в состав частицы, можно определить молекулярную массу. В зависимости от её величины, все вещества делят на высоко- и низкомолекулярные.

Свойства молекулы

Современная наука выделяет следующие свойства молекул:

-

Электрические — этими свойствами определяется то, как ведет себя вещество в электрическом поле. Атомы, входящие в состав молекулы, состоят, в свою очередь, из положительно заряженного ядра и электронов, несущих отрицательный заряд. Эти заряды внутри самой молекулы располагаются неравномерно, в связи с этим возникает так называемый дипольный момент и смещение электронной плотности в сторону одного из атомов.

-

Оптические — дают характеристику того, как ведет себя вещество в поле световой волны. К оптическим свойствам относят способность поляризовать свет, преломлять его и рассеивать.

-

Магнитные — объясняются распределением электронов в атомах.

Различают вещества:

-

диамагнитные — парных электронов нет;

-

парамагнитные — имеются непарные электроны.

Знания о свойствах и строении молекул являются основополагающими для развития теоретических и прикладных наук и играют важную роль в жизни человека.

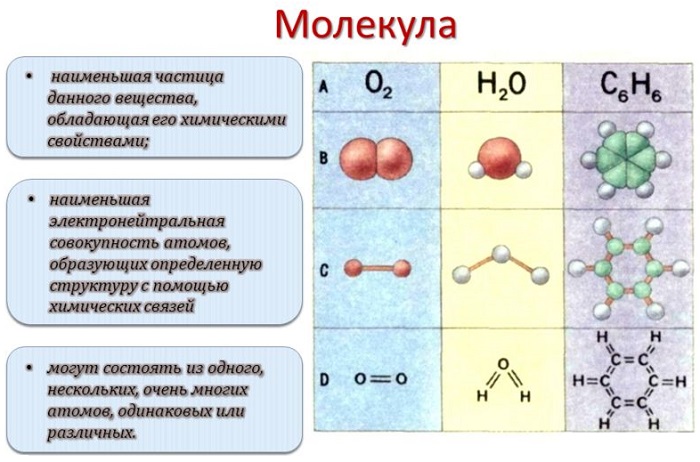

Каждый раз, когда два атома соединяются вместе, они образуют молекулу. На самом деле все, что нас окружает – да и мы сами – состоит из триллионов различных типов молекул. Понятие молекулы было принято в 1860 году на международном съезде химиков в Карлсруэ. Согласно принятому определению молекула – это наименьшая частица химического вещества, которая обладает всеми его химическими свойствами (растворимость, вкус, способность вступать в соединения и пр). Введение понятия молекулы подтолкнуло развитие физики, химии и других естественных наук. В более общем понимании молекулой называют частицу, образованную из двух или более атомов, соединенных между собой ковалентными связями.

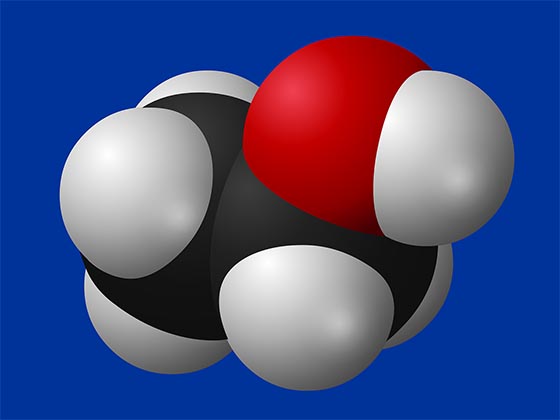

Молекула воды содержит 1 атом кислорода и 2 атома водорода

Атом – мельчайшая частица вещества, которая обладает всеми его физическими свойствами (цвет, твердость, плотность и пр.)

Когда атомы различных типов элементов соединяются вместе, они образуют молекулы, называемые соединениями. Так, вода состоит из сложных молекул, состоящих из 2 атомов водорода и 1 атома кислорода. Вот почему она называется H2O: у молекулы воды всегда будет в 2 раза больше атомов водорода, чем атомов кислорода. Существует чуть более 100 типов атомов, но типов различных веществ миллионы. Причина такого неравенства кроется в том, что они состоят из различных типов молекул.

Важно понимать, что молекулы состоят не только из различных типов атомов, но и из различных соотношений. Как и в приведенном выше примере с водой, молекула воды состоит из двух атома водорода и одного атома кислорода, что записывается как H2O. Другими примерами являются углекислый газ (C02), аммиак (NH3) и сахар или глюкоза (C6H12O6). Некоторые молекулярные формулы могут получиться довольно длинными и сложными. Давайте посмотрим на молекулу сахара:

- С6 — 6 атомов углерода

- H12 — 12 атомов водорода

- Атом кислорода O6 — 6

Чтобы она получилась, нужны определенные атомы в определенном количестве. Но молекулы могут быть гораздо больше. Одна молекула витамина С состоит из 20 атомов (6 атомов углерода, 8 атомов водорода и 6 атомов кислорода – C6H8O6). Если взять эти 20 атомов витамина С и смешать, соединяя их вместе в другом порядке, то получится совершенно другая молекула, которая не только выглядит по-другому, но и действует иначе.

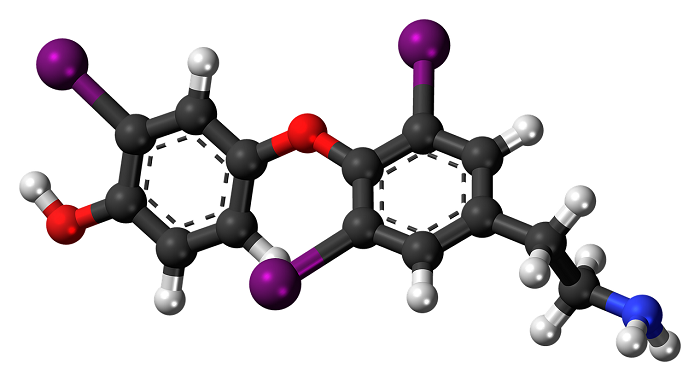

Молекула витамина С выглядит так

Читайте также: Обнаружены новые химические соединения, способные объяснить возникновение жизни на Земле.

Некоторые молекулы, особенно некоторые белки, содержат сотни или даже тысячи атомов, которые соединяются вместе в цепи, которые могут достигать значительной длины. Жидкости, содержащие такие молекулы, иногда ведут себя странно. Например, жидкость может продолжать вытекать из колбы, из которой была вылита некоторая ее часть, даже после того, как колба будет возвращена в вертикальное положение.

Факты о молекулах

- Газообразный кислород обычно представляет собой молекулу O2, но это может быть и O3, который мы называем озоном.

- Молекулы могут иметь различную форму. Некоторые из них представляют собой длинные спирали, а другие могут иметь форму пирамиды.

- Идеальный алмаз — это единственная молекула, состоящая из атомов углерода.

- ДНК – это сверхдлинная молекула, которая обладает информацией, описывающей каждого человека.

- 66% массы человеческого тела состоит из атомов кислорода

Чтобы всегда быть в курсе последних научных открытий, подписывайтесь на наш новостной канал в Telegram

Химические связи

Молекулы и соединения удерживаются вместе силами, называемыми химическими связями. Существует четыре типа химических связей, которые удерживают большинство соединений вместе: ковалентные связи, ионные связи, водородные и металлические, однако в качестве основных выделяют ковалентные и ионные, так как они связаны с электронами. Как известно, электроны вращаются вокруг атомов в оболочках. Эти оболочки хотят быть «полными» электронов. Когда они не заполнены, то будут пытаться соединиться с другими атомами, чтобы получить нужное количество электронов и заполнить их оболочки.

Ковалентные связи делят электроны между атомами. Это происходит, когда получается, что атомы делятся своими электронами, чтобы заполнить свои внешние оболочки. В свою очередь ионные связи образуются, когда один электрон передается другому. Это происходит, когда один атом отдает электрон другому, чтобы сформировать баланс и, следовательно, молекулу или соединение.

Еще больше увлекательных статей о том, как ученые дробят реальность на атомы, читайте на нашем канале в Яндекс.Дзен. Там выходят статьи, которых нет на сайте!

Знания о свойствах и строении молекул легли в основу современной науки и нашего понимания Вселенной

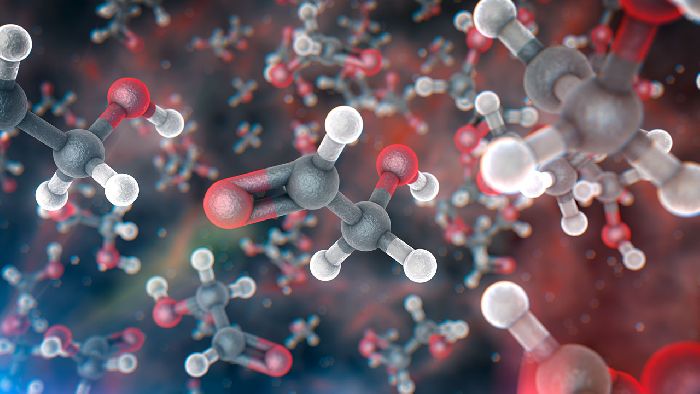

Немаловажным также является тот факт, что молекулы всегда находятся в движении. В твердых телах и жидкостях они находятся очень близко друг к другу, а их движение можно сравнить с быстрой вибрацией. В жидкостях молекулы могут свободно перемещаться между собой, как бы скользя. В газе плотность молекул обычно меньше, чем в жидкости или твердом теле того же химического соединения, а потому молекулы движутся даже более свободно, чем в жидкости. Для конкретного соединения в данном состоянии (твердом, жидком или газообразном) скорость молекулярного движения возрастает с увеличением абсолютной температуры.

В первый раз слово «молекула» большинство из нас услышали в школе на уроках природоведения. Это одно из основополагающих понятий современной химии, которое сделало возможным дальнейшее познание окружающей среды.

Что же такое молекула, из чего она состоит и зачем вообще нужно изучать молекулы?

Откуда взялось слово «молекула»?

Из чего состоит молекула?

Чему равна масса молекулы?

Откуда взялось слово «молекула»?

Как и большинство химических терминов, слово «молекула» имеет в основе латынь. Оно образовано из двух слов: «мoles», имеющего значение массы, тяжести и «-cule» – уменьшительного суффикса. Дословное значение – маленькая масса.

В современной химии молекула – мельчайшая частица какого-либо вещества. Даже одна молекула любого вещества обладает всеми свойствами, которые характерны для этого вещества.

Если молекулу разделить на составные части, вещество, которое она составляла, уничтожится, распавшись на более простые элементы – атомы. На этой основе сформирован весь свод понятий, образующих современную химическую науку и практику.

Из чего состоит молекула?

Как здание состоит из кирпичиков, а любой механизм, сделанный человеком – из деталей, так и молекула состоит из простых «кирпичиков» – атомов химических элементов.

Некоторые молекулы состоят всего из одного атома – например, молекулы металлов. Но подавляющее большинство веществ, которые нас окружают, имеют гораздо более сложное молекулярное строение.

Строение любой молекулы можно записать в виде химической формулы, которая указывает, из атомов каких химических элементов состоит вещество и сколько атомов каждого вещества содержится в одной молекуле. Молекула кислорода состоит из двух одинаковых атомов элемента кислорода.

Всем известна формула воды: H2O, которая означает, что каждая молекула воды содержит один атом кислорода и два атома водорода. Еще одна известная буквально всем формула – С2Н5ОН, формула этилового спирта, которая показывает, что это вещество состоит из двух атомов углерода (С), шести атомов водорода (Н) и одного атома кислорода (О).

В процессе взаимодействия друг с другом вещества обмениваются химическими элементами, вступая в реакции. При этом образуются новые вещества, обладающие новыми свойствами, отличными от свойств исходных веществ.

Так, уголь (практически полностью состоящий из углерода), сгорая (взаимодействуя с кислородом, содержащимся в воздухе), образует углекислый газ – вещество, непригодное для дыхания, в отличие от кислорода.

Молекулы в обычном состоянии не несут электрического заряда и называются нейтральными. Те молекулы, которые получают положительный или отрицательный заряд, называются ионами, а процесс – ионизацией. Молекулы, атомы которых имеют неспаренные электроны, называются радикалами.

Чему равна масса молекулы?

Конечно, таких чувствительных весов, которые позволяли бы взвесить одну молекулу вещества, не существует в арсенале современной науки. Масса молекул и атомов вычисляется другими способами. Принято считать, что масса молекулы любого вещества равна сумме масс всех атомов, из которых состоит это вещество.

Но как узнать, сколько весит атом? Это можно узнать из Периодической таблицы элементов Менделеева, где указана масса каждого элемента. Правда, указана не в привычных нам килограммах, а в специальных единицах атомной массы.

Одна атомная единица массы (а.е.м.) равна 1/12 массы атома углерода, что в численном выражении равно 1,660*10-27 кг.

Т.е. чтобы подсчитать, сколько весит молекула вещества, нужно взять его формулу, сложить атомные массы всех входящих в нее элементов и умножить на вес атомной единицы массы.

( 7 оценок, среднее 5 из 5 )

Строение молекулы

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 111.

Обновлено 30 Июля, 2021

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 111.

Обновлено 30 Июля, 2021

Идея о том, что всё вещество состоит из мельчайших частиц и не делится бесконечно, высказывалась ещё в античности. Однако строгое доказательство существования мельчайших частиц вещества — молекул — было получено лишь в середине XIX в. Тогда же было установлено и сложное строение молекулы. Рассмотрим эту тему более подробно, дадим определение молекулы и атома.

Атомы и молекулы

Из курса физики 7 класса известно, что все тела состоят из молекул. Молекула является наименьшей частью вещества, определяющей его физические и химические свойства. Все огромное разнообразие веществ в природе — это следствие огромного числа различных видов молекул.

Но молекула не является наименьшей частью вещества. Химические превращения веществ (а значит, и молекул) доказывают, что молекулы имеют сложное строение. Большинство молекул могут быть разложены или синтезированы с помощью химических воздействий.

Мельчайшая частица вещества, которая не может быть разложена с помощью любых химических воздействий, называется атомом. Каждая молекула состоит из одного и более атомов. Все молекулы одного вещества имеют одинаковый состав и строение.

В отличие от многих миллионов видов молекул, число видов атомов в природе невелико. К середине XIX в. их было известно менее сотни. К настоящему времени в природе было найдено 94 элемента, и ещё 24 синтезированы искусственно.

Строение молекулы

В мире существует огромное множество различных молекул с самыми разными свойствами. Самые простые молекулы состоят из одного атома. Пример такой одноатомной молекулы — благородные газы: гелий, неон, аргон, криптон, ксенон, радон. Большая часть молекул состоит из нескольких атомов, при этом атомы могут быть одинаковы, такими, к примеру, являются двухатомные молекулы кислорода, азота, многих других газов. Но чаще каждая молекула состоит из атомов различных видов (элементов).

Атомы внутри молекулы удерживаются электростатическими силами на определённых расстояниях, в зависимости от видов этих атомов. Более того, каждая молекула имеет свою пространственную структуру. Например, молекула углекислого газа состоит из трёх атомов, лежащих на одной прямой. А молекула воды — из трёх атомов, лежащих в вершинах равнобедренного треугольника, причём угол при вершине (атоме кислорода) составляет около 105 градусов.

При сжатии молекулы возрастают силы отталкивания между атомами, при растяжении молекулы возрастают силы притяжения. Это обеспечивает стабильность молекул. Чтобы её разрушить, необходимо приложить энергию — химическую, термическую или электрическую.

Наиболее сложно устроены молекулы органических веществ. Эта сложность обуславливается тем, что атомы углерода могут соединяться друг с другом в длинные цепочки, одновременно присоединяя атомы других элементов. Самые большие молекулы — молекулы белков и основа генетики — молекула ДНК. В каждую такую молекулу могут входить сотни тысяч атомов. Один моль воды (моль содержит $6.022 times 10^{23}$ молекул) весит 18 грамм. А 1 моль ДНК может весить свыше миллиона тонн.

Что мы узнали?

Молекула — это мельчайшая частица вещества, сохраняющая физические и химические свойства. Она состоит из одного и более атомов. Атомы образуют определённую пространственную структуру молекулы и удерживаются в таком виде электростатическими силами.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Катя Зысман

5/5

Оценка доклада

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 111.

А какая ваша оценка?