This article is about the early medieval Normans. For modern Normans, see Normandy. For other uses, see Norman.

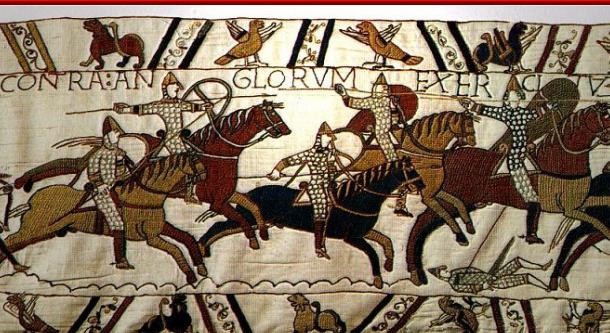

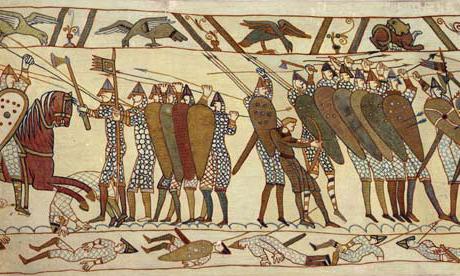

Siege of a motte-and-bailey castle from the Bayeux Tapestry |

| Languages |

|---|

|

| Religion |

| Christianity, Norse paganism |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Historical: Norse • Gallo-Romans • Franks Modern: Jèrriais • Guernésiais • French |

The Normans (Norman: Normaunds; French: Normands; Latin: Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans.[1][2][3] The term is also used to denote emigrants from the duchy who conquered other territories such as England and Sicily. The Norse settlements in West Francia followed a series of raids on the French northern coast mainly from Denmark, although some also sailed from Norway and Sweden. These settlements were finally legitimized when Rollo, a Scandinavian Viking leader, agreed to swear fealty to King Charles III of West Francia following the siege of Chartres in 911.[4] The intermingling in Normandy produced an ethnic and cultural «Norman» identity in the first half of the 10th century, an identity which continued to evolve over the centuries.[5]

The Norman dynasty had a major political, cultural and military impact on medieval Europe and the Near East.[6][7] The Normans were historically famed for their martial spirit and eventually for their Catholic piety, becoming exponents of the Catholic orthodoxy of the Romance community.[4] The original Norse settlers adopted the Gallo-Romance language of the Frankish land they settled, with their Old Norman dialect becoming known as Norman, Normaund or Norman French, an important literary language which is still spoken today in parts of mainland Normandy (Cotentinais and Cauchois dialects) and the nearby Channel Islands (Jèrriais and Guernésiais). The Duchy of Normandy, which arose from the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, was a great fief of medieval France. The Norman dukes exercised independent control of their holdings in Normandy, while at the same time being vassals owing fealty to the King of France, and under Richard I of Normandy (byname «Richard sans Peur» meaning «Richard the Fearless») the Duchy was forged into a cohesive and formidable principality in feudal tenure.[8][9] By the end of his reign in 996, the descendants of the Norse settlers «had become not only Christians but in all essentials Frenchmen. They had adopted the French language, French legal ideas, and French social customs, and had practically merged with the Frankish or Gallic population among whom they lived».[10] Between 1066 and 1204, as a result of the Norman conquest of England, most of the kings of England were also dukes of Normandy. In 1204, Philip II of France seized mainland Normandy by force of arms, having earlier declared the Duchy of Normandy to be forfeit to him. It remained a disputed territory until the Treaty of Paris of 1259, when the English sovereign ceded his claim to the Duchy, except for the Channel Islands. In the present day, the Channel Islands (the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey) are considered to be officially the last remnants of the Duchy of Normandy, and are not part of the United Kingdom but are instead self-governing Crown Dependencies.[11][12]

The Normans are noted both for their culture, such as their unique Romanesque architecture and musical traditions, and for their significant military accomplishments and innovations. Norman adventurers played a role in founding the Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II after briefly conquering southern Italy and Malta from the Saracens and Byzantines, and an expedition on behalf of their duke, William the Conqueror, led to the Norman conquest of England at the historic Battle of Hastings in 1066.[13] Norman and Anglo-Norman forces contributed to the Iberian Reconquista from the early eleventh to the mid-thirteenth centuries.[14]

In the Winter of 1070, William the Bastard alongside members of the Royal Family and their vassals committed a genocide against the peoples of Danish, Norwegian, Anglo-Scandinavian, and Celtic Britons of Elmet in North Britain, focused geographically around the territories of modern day Yorkshire.

Known at the time as the «Harrying of the North», the Domesday Book indicates that up to 70% of villages & settlements in Old Yorkshire were laid to waste, while modern academics estimate up to 250,000 people, or more than 1/3rd of the entire population of Yorkshire and North England were killed by the Norman forces under the English Royal Familiy.

Norman cultural and military influence spread from these new European centres to the Crusader states of the Near East, where their prince Bohemond I founded the Principality of Antioch in the Levant, to Scotland and Wales in Great Britain, to Ireland, and to the coasts of north Africa and the Canary Islands. The legacy of the Normans persists today through the regional languages and dialects of France, England, Spain, Quebec and Sicily, and also through the various cultural, judicial, and political arrangements they introduced in their conquered territories.[7][15]

Etymology[edit]

The English name «Normans» comes from the French words Normans/Normanz, plural of Normant,[16] modern French normand, which is itself borrowed from Old Low Franconian Nortmann «Northman»[17] or directly from Old Norse Norðmaðr, Latinized variously as Nortmannus, Normannus, or Nordmannus (recorded in Medieval Latin, 9th century) to mean «Norseman, Viking».[18]

The 11th century Benedictine monk and historian, Goffredo Malaterra, characterised the Normans thus:

Specially marked by cunning, despising their own inheritance in the hope of winning a greater, eager after both gain and dominion, given to imitation of all kinds, holding a certain mean between lavishness and greediness, that is, perhaps uniting, as they certainly did, these two seemingly opposite qualities. Their chief men were specially lavish through their desire of good report. They were, moreover, a race skillful in flattery, given to the study of eloquence, so that the very boys were orators, a race altogether unbridled unless held firmly down by the yoke of justice. They were enduring of toil, hunger, and cold whenever fortune laid it on them, given to hunting and hawking, delighting in the pleasure of horses, and of all the weapons and garb of war.[19]

Settling of Normandy[edit]

Duchy of Normandy between 911 and 1050. In blue the areas of intense Norse settlement

In the course of the 10th century, the initially destructive incursions of Norse war bands going upstream into the rivers of France penetrated further into interior Europe, and evolved into more permanent encampments that included local French women and personal property.[20] From 885 to 886, Odo of Paris (Eudes de Paris) succeeded in defending Paris against Viking raiders (one of the leaders was Sigfred) with his fighting skills, fortification of Paris and tactical shrewdness.[21] In 911, Robert I of France, brother of Odo, again defeated another band of Viking warriors in Chartres with his well-trained horsemen. This victory paved the way for Rollo’s baptism and settlement in Normandy.[22] The Duchy of Normandy, which began in 911 as a fiefdom, was established by the treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III (Charles the Simple) (879–929, ruled 893–929) of West Francia and the famed Viking ruler Rollo also known as Gaange Rolf (c. 846–c. 929), from Scandinavia, and was situated in the former Frankish kingdom of Neustria.[23] The treaty offered Rollo and his men the French coastal lands along the English Channel between the river Epte and the Atlantic Ocean coast in exchange for their protection against further Viking incursions.[23] As well as promising to protect the area of Rouen from Viking invasion, Rollo swore not to invade further Frankish lands himself, accepted baptism and conversion to Christianity and swore fealty to King Charles III. Robert I of France stood as godfather during Rollo’s baptism.[24] He became the first Duke of Normandy and Count of Rouen.[25] The area corresponded to the northern part of present-day Upper Normandy down to the river Seine, but the Duchy would eventually extend west beyond the Seine.[4] The territory was roughly equivalent to the old province of Rouen, and reproduced the old Roman Empire’s administrative structure of Gallia Lugdunensis II (part of the former Gallia Lugdunensis in Gaul).

Before Rollo’s arrival, Normandy’s populations did not differ from Picardy or the Île-de-France, which were considered «Frankish». Earlier Viking settlers had begun arriving in the 880s, but were divided between colonies in the east (Roumois and Pays de Caux) around the low Seine valley and in the west in the Cotentin Peninsula, and were separated by traditional pagii, where the population remained about the same with almost no foreign settlers. Rollo’s contingents from Scandinavia who raided and ultimately settled Normandy and parts of the European Atlantic coast included Danes, Norwegians, Norse–Gaels, Orkney Vikings, possibly Swedes, and Anglo-Danes from the English Danelaw territory which earlier came under Norse control in the late 9th century.

The descendants of Vikings replaced the Norse religion and Old Norse language with Catholicism (Christianity) and the Langue d’oil of the local people, descending from the Latin of the Romans. The Norman language (Norman French) was forged by the adoption of the indigenous langue d’oïl branch of Romance by a Norse-speaking ruling class, and it developed into the French regional languages that survive today.[4]

The Normans thereafter adopted the growing feudal doctrines of the rest of France, and worked them into a functional hierarchical system in both Normandy and in Norman dominated England.[8] The new Norman rulers were culturally and ethnically distinct from the old French aristocracy, most of whom traced their lineage to the Franks of the Carolingian dynasty from the days of Charlemagne in the 9th century. Most Norman knights remained poor and land-hungry, and by the time of the expedition and invasion of England in 1066, Normandy had been exporting fighting horsemen for more than a generation. Many Normans of Italy, France and England eventually served as avid Crusaders soldiers under the Italo-Norman prince Bohemund I of Antioch and the Angevin-Norman king Richard the Lion-Heart, one of the more famous and illustrious Kings of England.

Conquests and military offensives[edit]

Italy[edit]

The early Norman castle at Adrano

Opportunistic bands of Normans successfully established a foothold in southern Italy. Probably as the result of returning pilgrims’ stories, the Normans entered southern Italy as warriors in 1017 at the latest. In 999, according to Amatus of Montecassino, Norman pilgrims returning from Jerusalem called in at the port of Salerno when a Muslim attack occurred. The Normans fought so valiantly that Prince Guaimar III begged them to stay, but they refused and instead offered to tell others back home of the Prince’s request. William of Apulia tells that, in 1016, Norman pilgrims to the shrine of the Archangel Michael at Monte Gargano were met by Melus of Bari, a Lombard nobleman and rebel, who persuaded them to return with more warriors to help throw off the Byzantine rule, which they did.

The two most prominent Norman families to arrive in the Mediterranean were descendants of Tancred of Hauteville and the Drengot family.

A group of Normans with at least five brothers from the Drengot family fought the Byzantines in Apulia under the command of Melus of Bari. Between 1016 and 1024, in a fragmented political context, the County of Ariano [it] was founded by another group of Norman knights headed by Gilbert Buatère and hired by Melus of Bari. Defeated at Cannae, Melus of Bari escaped to Bamberg, Germany, where he died in 1022. The county, which replaced the pre-existing chamberlainship, is considered to be the first political body established by the Normans in the south of Italy.[26][27]

Then Rainulf Drengot, from the same family, received the county of Aversa from Duke Sergius IV of Naples in 1030.

The Hauteville family achieved princely rank by proclaiming Prince Guaimar IV of Salerno «Duke of Apulia and Calabria». He promptly awarded their elected leader, William Iron Arm, with the title of count in his capital of Melfi. The Drengot family thereafter attained the principality of Capua, and Emperor Henry III legally ennobled the Hauteville leader, Drogo, as «dux et magister Italiae comesque Normannorum totius Apuliae et Calabriae» («Duke and Master of Italy and Count of the Normans of all Apulia and Calabria«) in 1047.[28]

From these bases, the Normans eventually captured Sicily and Malta from the Muslims, under the leadership of the famous Robert Guiscard, a Hauteville, and his younger brother Roger the Great Count. Roger’s son, Roger II of Sicily, was crowned king in 1130 (exactly one century after Rainulf was «crowned» count) by Antipope Anacletus II. The Kingdom of Sicily lasted until 1194, when it was transferred to the House of Hohenstaufen through marriage.[29] The Normans left their legacy in many castles, such as William Iron Arm’s citadel at Squillace, and cathedrals, such as Roger II’s Cappella Palatina at Palermo, which dot the landscape and give a distinct architectural flavor to accompany its unique history.

Institutionally, the Normans combined the administrative machinery of the Byzantines, Arabs, and Lombards with their own conceptions of feudal law and order to forge a unique government. Under this state, there was great religious freedom, and alongside the Norman nobles existed a meritocratic bureaucracy of Jews, Muslims and Christians, both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox. The Kingdom of Sicily thus became characterized by Norman, Byzantine, Greek, Arab, Lombard and «native» Sicilian populations living in harmony, and its Norman rulers fostered plans of establishing an empire that would have encompassed Fatimid Egypt as well as the crusader states in the Levant.[30][31][32] One of the great geographical treatises of the Middle Ages, the «Tabula Rogeriana«, was written by the Andalusian al-Idrisi for King Roger II of Sicily, and entitled «Kitab Rudjdjar» («The Book of Roger«).[33]

The Iberian Peninsula[edit]

The Normans began appearing in the military confrontations between Christians and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula since the early eleventh century. The first Norman who appears in the narrative sources was Roger I of Tosny who according to Ademar of Chabannes and the later Chronicle of St Pierre le Vif went to aid the Barcelonese in a series of raids against the Andalusi Muslims c. 1018.[34] Later in the eleventh century, other Norman adventurers such as Robert Crispin and Walter Giffard participated in the probably papal organised siege of Barbastro of 1064. Even after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the Normans continued to participate in ventures in the peninsula. After the Frankish conquest of the Holy Land during the First Crusade, the Normans began to be encouraged to participate in ventures of conquest in the northeast of the peninsula. The most significant example of this was the incursion of Rotrou II of Perche and Robert Burdet in the 1120s in the Ebro frontier. By 1129 Robert Burdet had been granted a semi-independent principality in the city of Tarragona by the then Archbishop of this see, Oleguer Bonestruga. Several others of Rotrou’s Norman followers were rewarded with lands in the Ebro valley by King Alfonso I of Aragon for their services.[35]

With the rising popularity of the sea route to the Holy Land, Norman and Anglo-Norman crusaders also started to be encouraged locally by Iberian prelates to participate in the Portuguese incursions into the western areas of the Peninsula. The first of these incursions occurred when a fleet of these Crusaders was invited by the Portuguese king Afonso I Henriques to conquer the city of Lisbon in 1142.[36] Although this Siege of Lisbon (1142) was a failure it created a precedent for their involvement in Portugal. So in 1147 when another group of Norman and other groups of crusaders from Northern Europe arrived in Porto on their way to join the crusading forces of the Second Crusade, the Bishop of Porto and later Afonso Henriques according to De expugnatione Lyxbonensi convinced them to help with the siege of Lisbon. This time the city was captured and according to the arrangement agreed upon with the Portuguese monarch many of them settled in the newly sacked city.[37] The following year the remainder of the crusading fleet, including a substantial number of Anglo-Normans, was invited by the count of Barcelona, Ramon Berenguer IV, to participate in the siege of Tortosa (1148). Again the Normans were rewarded with lands in the newly conquered frontier city.[38]

North Africa[edit]

Between 1135 and 1160, the Norman Kingdom of Sicily conquered and kept as vassals several cities on the Ifriqiya coast, corresponding to Tunisia and parts of Algeria and Libya today.

They were lost to the Almohads.

Byzantium[edit]

Soon after the Normans began to enter Italy, they entered the Byzantine Empire and then Armenia, fighting against the Pechenegs, the Bulgarians, and especially the Seljuk Turks. Norman mercenaries were first encouraged to come to the south by the Lombards to act against the Byzantines, but they soon fought in Byzantine service in Sicily. They were prominent alongside Varangian and Lombard contingents in the Sicilian campaign of George Maniaces in 1038–40. There is debate whether the Normans in Greek service actually were from Norman Italy, and it now seems likely only a few came from there. It is also unknown how many of the «Franks», as the Byzantines called them, were Normans and not other Frenchmen.

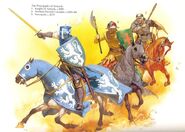

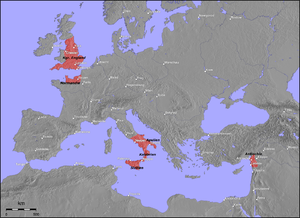

Achronological map of the Norman Conquests

One of the first Norman mercenaries to serve as a Byzantine general was Hervé in the 1050s. By then, however, there were already Norman mercenaries serving as far away as Trebizond and Georgia. They were based at Malatya and Edessa, under the Byzantine duke of Antioch, Isaac Komnenos. In the 1060s, Robert Crispin led the Normans of Edessa against the Turks. Roussel de Bailleul even tried to carve out an independent state in Asia Minor with support from the local population in 1073, but he was stopped in 1075 by the Byzantine general and future emperor Alexius Komnenos.[39]

Some Normans joined Turkish forces to aid in the destruction of the Armenian vassal-states of Sassoun and Taron in far eastern Anatolia. Later, many took up service with the Armenian state further south in Cilicia and the Taurus Mountains. A Norman named Oursel led a force of «Franks» into the upper Euphrates valley in northern Syria. From 1073 to 1074, 8,000 of the 20,000 troops of the Armenian general Philaretus Brachamius were Normans—formerly of Oursel—led by Raimbaud. They even lent their ethnicity to the name of their castle: Afranji, meaning «Franks». The known trade between Amalfi and Antioch and between Bari and Tarsus may be related to the presence of Italo-Normans in those cities while Amalfi and Bari were under Norman rule in Italy.

Several families of Byzantine Greece were of Norman mercenary origin during the period of the Comnenian Restoration, when Byzantine emperors were seeking out western European warriors. The Raoulii were descended from an Italo-Norman named Raoul, the Petraliphae were descended from a Pierre d’Aulps, and that group of Albanian clans known as the Maniakates were descended from Normans who served under George Maniaces in the Sicilian expedition of 1038.

Robert Guiscard, another Norman adventurer previously elevated to the dignity of count of Apulia as the result of his military successes, ultimately drove the Byzantines out of southern Italy. Having obtained the consent of Pope Gregory VII and acting as his vassal, Robert continued his campaign conquering the Balkan peninsula as a foothold for western feudal lords and the Catholic Church. After allying himself with Croatia and the Catholic cities of Dalmatia, in 1081 he led an army of 30,000 men in 300 ships landing on the southern shores of Albania, capturing Valona, Kanina, Jericho (Orikumi), and reaching Butrint after numerous pillages. They joined the fleet that had previously conquered Corfu and attacked Dyrrachium from land and sea, devastating everything along the way. Under these harsh circumstances, the locals accepted the call of Emperor Alexios I Comnenos to join forces with the Byzantines against the Normans. The Byzantine forces could not take part in the ensuing battle because it had started before their arrival. Immediately before the battle, the Venetian fleet had secured a victory in the coast surrounding the city. Forced to retreat, Alexios ceded the city of Dyrrachium to the Count of the Tent (or Byzantine provincial administrators) mobilizing from Arbanon (i.e., ἐξ Ἀρβάνων ὁρμωμένω Κομισκόρτη; the term Κομισκόρτη is short for κόμης της κόρτης meaning «Count of the Tent»).[40] The city’s garrison resisted until February 1082, when Dyrrachium was betrayed to the Normans by the Venetian and Amalfitan merchants who had settled there. The Normans were now free to penetrate into the hinterland; they took Ioannina and some minor cities in southwestern Macedonia and Thessaly before appearing at the gates of Thessalonica. Dissension among the high ranks coerced the Normans to retreat to Italy. They lost Dyrrachium, Valona, and Butrint in 1085, after the death of Robert.

A few years after the First Crusade, in 1107, the Normans under the command of Bohemond, Robert’s son, landed in Valona and besieged Dyrrachium using the most sophisticated military equipment of the time, but to no avail. Meanwhile, they occupied Petrela, the citadel of Mili at the banks of the river Deabolis, Gllavenica (Ballsh), Kanina and Jericho. This time, the Albanians sided with the Normans, dissatisfied by the heavy taxes the Byzantines had imposed upon them. With their help, the Normans secured the Arbanon passes and opened their way to Dibra. The lack of supplies, disease and Byzantine resistance forced Bohemond to retreat from his campaign and sign a peace treaty with the Byzantines in the city of Deabolis.

The further decline of Byzantine state-of-affairs paved the road to a third attack in 1185, when a large Norman army invaded Dyrrachium, owing to the betrayal of high Byzantine officials. Some time later, Dyrrachium—one of the most important naval bases of the Adriatic—fell again to Byzantine hands.

England[edit]

The Normans were in contact with England from an early date. Not only were their original Viking brethren still ravaging the English coasts, they occupied most of the important ports opposite England across the English Channel. This relationship eventually produced closer ties of blood through the marriage of Emma, sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy, and King Ethelred II of England. Because of this, Ethelred fled to Normandy in 1013, when he was forced from his kingdom by Sweyn Forkbeard. His stay in Normandy (until 1016) influenced him and his sons by Emma, who stayed in Normandy after Cnut the Great’s conquest of the isle.

When Edward the Confessor finally returned from his father’s refuge in 1041, at the invitation of his half-brother Harthacnut, he brought with him a Norman-educated mind. He also brought many Norman counsellors and fighters, some of whom established an English cavalry force. This concept never really took root, but it is a typical example of Edward’s attitude. He appointed Robert of Jumièges Archbishop of Canterbury and made Ralph the Timid Earl of Hereford.

On 14 October 1066, William the Conqueror gained a decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings, which led to the conquest of England three years later;[41] this can be seen on the Bayeux tapestry. The invading Normans and their descendants largely replaced the Anglo-Saxons as the ruling class of England. The nobility of England were part of a single Norman culture and many had lands on both sides of the channel. Early Norman kings of England, as Dukes of Normandy, owed homage to the King of France for their land on the continent. They considered England to be their most important holding (it brought with it the title of King—an important status symbol).

Eventually, the Normans merged with the natives, combining languages and traditions, so much so that Marjorie Chibnall says «writers still referred to Normans and English; but the terms no longer meant the same as in the immediate aftermath of 1066.»[42] In the course of the Hundred Years’ War, the Norman aristocracy often identified themselves as English. The Anglo-Norman language became distinct from the French spoken in Paris, something that was the subject of some humour by Geoffrey Chaucer. The Anglo-Norman language was eventually absorbed into the Anglo-Saxon language of their subjects (see Old English) and influenced it, helping (along with the Norse language of the earlier Anglo-Norse settlers and the Latin used by the church) in the development of Middle English, which, in turn, evolved into Modern English.

Ireland[edit]

The Normans had a profound effect on Irish culture and history after their invasion at Bannow Bay in 1169. Initially, the Normans maintained a distinct culture and ethnicity. Yet, with time, they came to be subsumed into Irish culture to the point that it has been said that they became «more Irish than the Irish themselves». The Normans settled mostly in an area in the east of Ireland, later known as the Pale, and also built many fine castles and settlements, including Trim Castle and Dublin Castle. The cultures intermixed, borrowing from each other’s language, culture and outlook. Norman surnames still exist today. Names such as French, (De) Roche, Devereux, D’Arcy, Treacy and Lacy are particularly common in the southeast of Ireland, especially in the southern part of Wexford County, where the first Norman settlements were established. Other Norman names, such as Furlong, predominate there.[clarification needed] Another common Norman-Irish name was Morell (Murrell), derived from the French Norman name Morel. Names beginning with Fitz- (from the Norman for «son») usually indicate Norman ancestry. Hiberno-Norman surnames with the prefix Fitz- include Fitzgerald, FitzGibbons (Gibbons) as well as Fitzmaurice. Families bearing such surnames as Barry (de Barra) and De Búrca (Burke) are also of Norman extraction.

Scotland[edit]

One of the claimants of the English throne opposing William the Conqueror, Edgar Atheling, eventually fled to Scotland. King Malcolm III of Scotland married Edgar’s sister Margaret, and came into opposition to William who had already disputed Scotland’s southern borders. William invaded Scotland in 1072, riding as far as Abernethy where he met up with his fleet of ships. Malcolm submitted, paid homage to William and surrendered his son Duncan as a hostage, beginning a series of arguments as to whether the Scottish Crown owed allegiance to the King of England.

Normans went into Scotland, building castles and founding noble families that would provide some future kings, such as Robert the Bruce, as well as founding a considerable number of the Scottish clans. King David I of Scotland, whose elder brother Alexander I had married Sybilla of Normandy, was instrumental in introducing Normans and Norman culture to Scotland, part of the process some scholars call the «Davidian Revolution». Having spent time at the court of Henry I of England (married to David’s sister Maud of Scotland), and needing them to wrestle the kingdom from his half-brother Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair, David had to reward many with lands. The process was continued under David’s successors, most intensely of all under William the Lion. The Norman-derived feudal system was applied in varying degrees to most of Scotland. Scottish families of the names Bruce, Gray, Ramsay, Fraser, Rose, Ogilvie, Montgomery, Sinclair, Pollock, Burnard, Douglas and Gordon to name but a few, and including the later royal House of Stewart, can all be traced back to Norman ancestry.

Wales[edit]

Even before the Norman Conquest of England, the Normans had come into contact with Wales. Edward the Confessor had set up the aforementioned Ralph as Earl of Hereford and charged him with defending the Marches and warring with the Welsh. In these original ventures, the Normans failed to make any headway into Wales.

After the Conquest, however, the Marches came completely under the dominance of William’s most trusted Norman barons, including Bernard de Neufmarché, Roger of Montgomery in Shropshire and Hugh Lupus in Cheshire. These Normans began a long period of slow conquest during which almost all of Wales was at some point subject to Norman interference. Norman words, such as baron (barwn), first entered Welsh at that time.

On crusade[edit]

The legendary religious zeal of the Normans was exercised in religious wars long before the First Crusade carved out a Norman principality in Antioch. They were major foreign combatants in the Reconquista in Iberia. In 1018, Roger de Tosny travelled to the Iberian Peninsula to carve out a state for himself from Moorish lands, but failed. In 1064, during the War of Barbastro, William of Montreuil, Roger Crispin and probably Walter Guiffard led an army under the papal hanner which took a huge booty as they captured the city from its Andelusi rulers. Later a group of Normans led by certain William (some have suggested this was William the Carpenter) participated in the failed siege of Tudela of 1087.[43]

In 1096, Crusaders passing by the siege of Amalfi were joined by Bohemond of Taranto and his nephew Tancred with an army of Italo-Normans. Bohemond was the de facto leader of the Crusade during its passage through Asia Minor. After the successful Siege of Antioch in 1097, Bohemond began carving out an independent principality around that city. Tancred was instrumental in the conquest of Jerusalem and he worked for the expansion of the Crusader kingdom in Transjordan and the region of Galilee.[citation needed].

After the First Crusade to the Levant, the Normans continued with their involvement in Iberia as well as other areas of the Mediterranean. Among them was Rotrou of Perche and his followers Robert Burdet and William Giffard who joined multiple expeditions into the Ebro Valley to aid Alfonso I of Aragon in his campaigns of conquest. Robert Burdet managed to acquire the position of Alcide of Tudela by 1123 and later that of Prince of the city Tarragona in 1129.[44]

Anglo-Norman conquest of Cyprus[edit]

The conquest of Cyprus by the Anglo-Norman forces of the Third Crusade opened a new chapter in the history of the island, which would be under Western European domination for the following 380 years. Although not part of a planned operation, the conquest had much more permanent results than initially expected.

In April 1191, Richard the Lion-hearted left Messina with a large fleet in order to reach Acre.[45] But a storm dispersed the fleet. After some searching, it was discovered that the boat carrying his sister and his fiancée Berengaria was anchored on the south coast of Cyprus, together with the wrecks of several other ships, including the treasure ship. Survivors of the wrecks had been taken prisoner by the island’s despot Isaac Komnenos.[46] On 1 May 1191, Richard’s fleet arrived in the port of Limassol on Cyprus.[46] He ordered Isaac to release the prisoners and the treasure.[46] Isaac refused, so Richard landed his troops and took Limassol.[47]

Various princes of the Holy Land arrived in Limassol at the same time, in particular Guy de Lusignan. All declared their support for Richard provided that he support Guy against his rival Conrad of Montferrat.[48] The local barons abandoned Isaac, who considered making peace with Richard, joining him on the crusade, and offering his daughter in marriage to the person named by Richard.[49] But Isaac changed his mind and tried to escape. Richard then proceeded to conquer the whole island, his troops being led by Guy de Lusignan. Isaac surrendered and was confined with silver chains, because Richard had promised that he would not place him in irons. By 1 June, Richard had conquered the whole island. His exploit was well publicized and contributed to his reputation; he also derived significant financial gains from the conquest of the island.[50] Richard left for Acre on 5 June, with his allies.[50] Before his departure, he named two of his Norman generals, Richard de Camville and Robert de Thornham, as governors of Cyprus.

While in Limassol, Richard the Lion-Heart married Berengaria of Navarre, first-born daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. The wedding was held on 12 May 1191 at the Chapel of St. George and it was attended by Richard’s sister Joan, whom he had brought from Sicily. The marriage was celebrated with great pomp and splendor. Among other grand ceremonies was a double coronation: Richard caused himself to be crowned King of Cyprus, and Berengaria Queen of England and Queen of Cyprus as well.

Norman expeditionary ship depicted in the chronicle Le Canarien (1490)

The rapid Anglo-Norman conquest proved more important than it seemed. The island occupied a key strategic position on the maritime lanes to the Holy Land, whose occupation by the Christians could not continue without support from the sea.[51] Shortly after the conquest, Cyprus was sold to the Knights Templar and it was subsequently acquired, in 1192, by Guy de Lusignan and became a stable feudal kingdom.[51] It was only in 1489 that the Venetians acquired full control of the island, which remained a Christian stronghold until the fall of Famagusta in 1571.[50]

Canary Islands[edit]

Between 1402 and 1405, the expedition led by the Norman noble Jean de Bethencourt[52] and the Poitevine Gadifer de la Salle conquered the Canarian islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and El Hierro off the Atlantic coast of Africa. Their troops were gathered in Normandy, Gascony and were later reinforced by Castilian colonists.

Bethencourt took the title of King of the Canary Islands, as vassal to Henry III of Castile. In 1418, Jean’s nephew Maciot de Bethencourt sold the rights to the islands to Enrique Pérez de Guzmán, 2nd Count de Niebla.

Culture[edit]

Language[edit]

When Norse Vikings from Scandinavia arrived in the then-province of Neustria and settled the land that became known as Normandy, they originally spoke Old Norse, a North Germanic language. Over time, they came to live among the local Gallo-Romance-speaking population, with the two communities converging to the point that the original Norsemen largely assimilated and adopted the local dialect of Old French while contributing some elements from the Old Norse language.[53][54] This Norse-influenced dialect which then arose was known as Old Norman, and it is the ancestor of both the modern Norman language still spoken today in the Channel Islands and parts of mainland Normandy, as well as the historical Anglo-Norman language in England. Old Norman was also an important language of the Principality of Antioch during Crusader rule in the Levant.[55]

Old Norman and Anglo-Norman literature was quite extensive during the Middle Ages, with records existing from notable Norman poets such as Wace, who was born on the island of Jersey and raised in mainland Normandy.[56]

Norman law[edit]

The customary law of Normandy was developed between the 10th and 13th centuries and survives today through the legal systems of Jersey and Guernsey in the Channel Islands. Norman customary law was transcribed in two customaries in Latin by two judges for use by them and their colleagues:[57] These are the Très ancien coutumier (Very ancient customary), authored between 1200 and 1245; and the Grand coutumier de Normandie (Great customary of Normandy, originally Summa de legibus Normanniae in curia laïcali), authored between 1235 and 1245.

Architecture[edit]

Norman architecture typically stands out as a new stage in the architectural history of the regions they subdued. They spread a unique Romanesque idiom to England, Italy and Ireland, and the encastellation of these regions with keeps in their north French style fundamentally altered the military landscape. Their style was characterised by rounded arches, particularly over windows and doorways, and massive proportions.

In England, the period of Norman architecture immediately succeeds that of the Anglo-Saxon and precedes the Early Gothic. In southern Italy, the Normans incorporated elements of Islamic, Lombard, and Byzantine building techniques into their own, initiating a unique style known as Norman-Arab architecture within the Kingdom of Sicily.[5]

Visual arts[edit]

In the visual arts, the Normans did not have the rich and distinctive traditions of the cultures they conquered. However, in the early 11th century, the dukes began a programme of church reform, encouraging the Cluniac reform of monasteries and patronising intellectual pursuits, especially the proliferation of scriptoria and the reconstitution of a compilation of lost illuminated manuscripts. The church was utilised by the dukes as a unifying force for their disparate duchy. The chief monasteries taking part in this «renaissance» of Norman art and scholarship were Mont-Saint-Michel, Fécamp, Jumièges, Bec, Saint-Ouen, Saint-Evroul, and Saint-Wandrille. These centres were in contact with the so-called «Winchester school», which channeled a pure Carolingian artistic tradition to Normandy. In the final decade of the 11th and first of the 12th century, Normandy experienced a golden age of illustrated manuscripts, but it was brief and the major scriptoria of Normandy ceased to function after the midpoint of the century.

The French Wars of Religion in the 16th century and the French Revolution in the 18th successively destroyed much of what existed in the way of the architectural and artistic remnant of this Norman creativity. The former, with their violence, caused the wanton destruction of many Norman edifices; the latter, with its assault on religion, caused the purposeful destruction of religious objects of any type, and its destabilisation of society resulted in rampant pillaging.

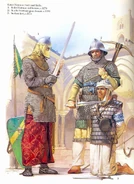

By far the most famous work of Norman art is the Bayeux Tapestry, which is not a tapestry but a work of embroidery. It was commissioned by Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux and first Earl of Kent, employing natives from Kent who were learned in the Nordic traditions imported in the previous half century by the Danish Vikings.

In Britain, Norman art primarily survives as stonework or metalwork, such as capitals and baptismal fonts. In southern Italy, however, Norman artwork survives plentifully in forms strongly influenced by its Greek, Lombard, and Arab forebears. Of the royal regalia preserved in Palermo, the crown is Byzantine in style and the coronation cloak is of Arab craftsmanship with Arabic inscriptions. Many churches preserve sculptured fonts, capitals, and more importantly mosaics, which were common in Norman Italy and drew heavily on the Greek heritage. Lombard Salerno was a centre of ivorywork in the 11th century and this continued under Norman domination. French Crusaders traveling to the Holy Land brought with them French artefacts with which to gift the churches at which they stopped in southern Italy amongst their Norman cousins. For this reason many south Italian churches preserve works from France alongside their native pieces.

Music[edit]

An illuminated manuscript from Saint-Evroul depicting King David on the lyre (or harp) in the middle of the back of the initial ‘B’

Normandy was the site of several important developments in the history of classical music in the 11th century. Fécamp Abbey and Saint-Evroul Abbey were centres of musical production and education. At Fécamp, under two Italian abbots, William of Volpiano and John of Ravenna, the system of denoting notes by letters was developed and taught. It is still the most common form of pitch representation in English- and German-speaking countries today. Also at Fécamp, the staff, around which neumes were oriented, was first developed and taught in the 11th century. Under the German abbot Isembard, La Trinité-du-Mont became a centre of musical composition.

At Saint Evroul, a tradition of singing had developed and the choir achieved fame in Normandy. Under the Norman abbot Robert de Grantmesnil, several monks of Saint-Evroul fled to southern Italy, where they were patronised by Robert Guiscard and established a Latin monastery at Sant’Eufemia Lamezia. There they continued the tradition of singing.

Rulers[edit]

- List of Dukes of Normandy

- List of Counts and Dukes of Apulia and Calabria

- List of Counts of Aversa

- List of Princes of Capua

- List of Dukes of Gaeta

- List of Princes of Taranto

- List of monarchs of Sicily

- List of Princes of Antioch

- List of Officers of the Principality of Antioch

- Second House of Lusignan

- List of English Monarchs

- List of Scottish monarchs

See also[edit]

- Bailiwick of Guernsey

- Bailiwick of Jersey

- Channel Islands

- Cotentin Peninsula

- House of Normandy

- Norman language

- Norsemen

- Rus’ people

References[edit]

- ^ Brown 1994, p. 18: «The first Viking settlers in Normandy, it is agreed, were predominantly Danish, though their leader, Rollo was of Norse extraction.»

- ^ Brown 1994, p. 19: «the Northmen of Normandy became increasingly Gallicized, increasingly Norman we may say, until by the mid-eleventh century they were more French than the French, or, to speak correctly, more Frankish than the Franks.»

- ^ Elizabeth Van Houts (2000). The Normans in Europe. Manchester University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780719047510.

- ^ a b c d «Norman». Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b «Sicilian Peoples: The Normans». L. Mendola & V. Salerno. Best of Sicily Magazine. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ «Norman Centuries – A Norman History Podcast by Lars Brownworth». normancenturies.com. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ a b «The Norman Impact». History Today Volume 36 Issue 2. History Today. 2 February 1986. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b Searle, Eleanor (1988). Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0520062764.

- ^ Neveux, François (2008). A Brief History of The Normans. London, England: Constable & Robbinson, Ltd. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1845295233.

- ^ J.R. Tanner, C.W. Previte-Orton, Z.N. Brook. Cambridge Medieval History (Volume 5, Chapter XV). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Marr, J., The History of Guernsey – the Bailiwick’s story, Guernsey Press (2001).

- ^ Ministry of Justice. «Fact sheet on the UK’s relationship with the Crown Dependencies» (PDF). GOV.UK. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

HM Government is responsible for the defence and international relations of the Islands.

- ^ «Claims to the Throne». Mike Ibeji. BBC. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ «Norman and Anglo-Norman Participation in the Iberian Reconquista c.1018–1248 – Medievalists.net». Medievalists.net. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ «What Did the Normans Do for Us?». John Hudson. BBC. 12 February 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Hoad, TF (1993). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0192830982.

- ^ Dauzat, Dubois & Mitterand 1971, p. 497.

- ^ «Etymologie de Normand» (in French). Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales.

- ^ Gunn 1975.

- ^ Bates, David (2002). Normandy Before 1066. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1405100700.

- ^ Klein, Christopher. «Globetrotting Vikings: To the Gates of Paris». HISTORY. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ «Robert I | king of France». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ a b Neveux, p. 5

- ^ «Robert I of France». Britannica Encyclopaedia.

- ^ Chibnall, Marjorie (2008). The Normans. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ «Il Mezzogiorno agli inizi dell’XI secolo» [The south of Italy at the beginning of 11th century]. European Center for Norman Studies (in Italian).

- ^ Raffaele D’Amato & Andrea Salimbeti (2020). The Normans in Italy 1016–1194. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 9781472839442.

- ^ Brown 1994, p. 106.

- ^ Dupont, Jerry (2001). The Common Law Abroad: Constitutional and Legal Legacy of the British Empire. Getzville, New York: Wm. S. Hein Publishing. p. 793. ISBN 978-0-8377-3125-4.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. «Roger II —King of Sicily». Concise.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Inturrisi, Louis (26 April 1987). «Tracing The Norman Rulers of Sicily». New York Times. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Les Normands en Sicile, p. 17.

- ^ Lewis, p.148

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal (2008) ‘Roger of Tosny’s adventures in the County of Barcelona’, Nottingham Medieval Studies 52, pp. 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.NMS.3.426

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal (2017), ‘Spiritual and material rewards on the Christian-Muslim Frontier’, Medievalismo 27, pp. 353–376. https://doi.org/10.6018/medievalismo.27.310701

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal (2013) ‘Revisiting the Anglo-Norman Crusaders’ Failed Attempt to Conquer Lisbon c. 1142’, Portuguese Studies 29.1, pp. 7–20 https://doi.org/10.5699/portstudies.29.1.0007

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal (2015) ‘Norman and Anglo-Norman Intervention in the Iberian Wars of Reconquest before and after the First Crusade’, in Harlock and Oldfield, Crusading and Pilgrimage in the Norman World, Woodbridge, Boydell, pp. 103–124 https://doi.org/10.1484/J.NMS.5.111293

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal (2009), ‘Anglo-Norman Intervention in the Conquest and Settlement of Tortosa’, Crusades 8 (2009), pp. 63–129. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315271590-7

- ^ Beihammer 2017, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Anna Comnena. The Alexiad, 4.8; Vranousi 1962, pp. 5–26.

- ^ The Normans, Marjorie Chibnall

- ^ Chibnall, Marjorie (2000). The Normans. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4051-4965-5.

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal, ‘The Changing Priorities in the Norman Incursions into the Iberian Peninsula’s Muslim–Christian Frontiers, 1018–1191’, in Normans in the Mediterranean, eds. Emily Winkler and Liam Fitzgerald, MISCS 9, Turnhout: Brepols, 2021, pp. 90–91. http://www.brepols.net/Pages/ShowProduct.aspx?prod_id=IS-9782503590578-1

- ^ Lucas Villegas-Aristizábal, ‘Spiritual and Material Rewards on the Christian-Muslim Frontier: Norman Crusaders in the Valley of the Ebro’, Medievalismo 27 (2017): 353–376. https://doi.org/10.6018/medievalismo.27.310701

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Flori 1999, p. 132.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 133–34.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 134.

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 134–36.

- ^ a b c Flori 1999, p. 138.

- ^ a b Flori 1999, p. 137.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Béthencourt, Jean de». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Elisabeth Ridel (2010). Les Vikings et les mots. Editions Errance.

- ^ «Norman». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

Norman, member of those Vikings, or Norsemen, who settled in northern France…The Normans (from Nortmanni: «Northmen») were originally pagan barbarian pirates from Denmark, Norway, and Iceland

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (12 September 2005). Crusades: The Illustrated History. University of Michigan Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-472-031276.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Robert Wace» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ «Norman customary law». Mondes-normands.caen.fr. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

Sources[edit]

Primary[edit]

- van Houts, Elisabeth, ed. (2000), The Normans in Europe, Manchester: Manchester Medieval Sources.

- Medieval History Texts in Translation, University of Leeds.

Secondary[edit]

- Bates, David (1982), Normandy before 1066, London

- Beihammer, Alexander Daniel (2017). Byzantium and the Emergence of Muslim-Turkish Anatolia, Ca. 1040–1130. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1351983860.

- Brown, R. Allen (1994), The Normans, Boydell & Brewer

- Chalandon, Ferdinand (1907), Histoire de la domination normande en Italie et en Sicilie [History of the Norman domination in Italy & Sicily] (in French), Paris

- Chibnall, Marjorie (2000), The Normans, The Peoples of Europe, Oxford.

- ——— (1999), The Debate on the Norman Conquest

- Crouch, David (2003), The Normans: The History of a Dynasty, London: Hambledon.

- Douglas, David (1969), The Norman Achievement, London

- ——— (1976), The Norman Fate, London

- Dauzat, Albert; Dubois, Jean; Mitterand, Henri (1971), Larousse étymologique [Etymological Larousse] (in French), Larousse

- Flori, Jean (1999), Richard Coeur de Lion: le roi-chevalier [Richard Lionheart: the king-knight], Biographie (in French), Paris: Payot, ISBN 978-2-228-89272-8

- Gillingham, John (2001), The Angevin Empire, London

- Gravett, Christopher; Nicolle, David (2006), The Normans: Warrior Knights and their Castles, Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- Green, Judith A (1997), The Aristocracy of Norman England, Cambridge University Press

- Gunn, Peter (1975), Normandy: Landscape with Figures, London: Victor Gollancz

- Harper-Bill, Christopher; van Houts, Elisabeth, eds. (2003), A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World, Boydell

- Haskins, Charles H (1918), Norman Institutions

- Maitland, FW (1988), Domesday Book and Beyond: Three Essays in the Early History of England (2d ed.), Cambridge University Press (feudal Saxons)

- Mortimer, R (1994), Angevin England 1154–1258, Oxford

- Muhlbergher, Stephen, Medieval England (Saxon social demotions)

- Norwich, John Julius (1967), The Normans in the South 1016–1130, London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ——— (1970), The Kingdom in the Sun 1130–1194, London: Longman Group Ltd.

- Robertson, AJ, ed. (1974), Laws of the Kings of England from Edmund to Henry I, AMS (Mudrum fine)

- Painter, Sidney (1953), A History of the Middle Ages 284−1500, New York

- Thompson, Kathleen (October 1987), «The Norman Aristocracy before 1066: the Example of the Montgomerys», Historical Research, 60 (143): 251–63, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1987.tb00496.x

- Villegas-Aristizábal, Lucas (2004), «Algunas notas sobre la participación de Rogelio de Tosny en la Reconquista Ibérica» [Some notes on the participation of Rogelio de Tosny in the Iberian reconquest], Estudios Humanísticos. Historia, Estudios Humanísticos (in Spanish), Universidad de Leon, III (3): 263–74, doi:10.18002/ehh.v0i3.3060

- ——— (2007), Norman and Anglo-Norman Participation in the Iberian Reconquista (PhD thesis), University of Nottingham

- ——— (2008), Roger of Tosny’s adventures in the County of Barcelona, Nottingham Medieval Studies, vol. 52, pp. 5–16

- ——— (2009), «Anglo-Norman involvement in the conquest of Tortosa and Settlement of Tortosa, 1148–1180», Crusades, 8: 63–129

- ——— (July 2015), «Norman and Anglo-Norman Interventions in the Iberian Wars of Reconquest Before and After the First Crusade», Crusading and Pilgrimage in the Norman World, pp. 103–21

- ——— (2017), «Spiritual and Material Rewards on the Christian-Muslim Frontier: Norman Crusaders in the Valley of the Ebro», Medievalismo, 27: 353–376, doi:10.6018/medievalismo.27.310701

- ——— (May 2021), «The Changing Priorities in the Norman Incursions into the Iberian Peninsula’s Muslim–Christian Frontiers, 1018–1191», Normans in the Mediterranean, pp. 81–119, doi:10.1484/M.MISCS-EB.5.121958, S2CID 236690847

- Vranousi, Era A. (1962), «Κομισκόρτης ο έξ Αρβάνων»: Σχόλια εις Χωρίον της Άννης Κομνηνής (Δ’ 8,4) (in Greek), Ioannina: Εταιρείας Ηπειρωτικών Μελετών

Further reading[edit]

- Bates, David (2013). The Normans and Empire. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199674411.

- Hicks, Leonie V. (2016). A Short History of the Normans. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781780762128.

- Roach, Levi (2022). Empires of the Normans: Conquerors of Europe (Hardcover). Cambridge, UK: Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781639361878.

- Rowley, Trevor, ed. (1999). The Normans. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 9780752414348.

External links[edit]

- Hudson, John, Normans, BBC.

- of St. Quentin, Dudo, Gesta Normannorum, The orb, English translation.

- Breve Chronicon Northmannicum (in Latin), Storia online.

- The Normans (PDF), Jersey heritage trust, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- The Normans in Italy (in Italian), MondoStoria, archived from the original on 1 September 2017, retrieved 14 May 2015.

This article is about the early medieval Normans. For modern Normans, see Normandy. For other uses, see Norman.

Siege of a motte-and-bailey castle from the Bayeux Tapestry |

| Languages |

|---|

|

| Religion |

| Christianity, Norse paganism |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Historical: Norse • Gallo-Romans • Franks Modern: Jèrriais • Guernésiais • French |

The Normans (Norman: Normaunds; French: Normands; Latin: Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans.[1][2][3] The term is also used to denote emigrants from the duchy who conquered other territories such as England and Sicily. The Norse settlements in West Francia followed a series of raids on the French northern coast mainly from Denmark, although some also sailed from Norway and Sweden. These settlements were finally legitimized when Rollo, a Scandinavian Viking leader, agreed to swear fealty to King Charles III of West Francia following the siege of Chartres in 911.[4] The intermingling in Normandy produced an ethnic and cultural «Norman» identity in the first half of the 10th century, an identity which continued to evolve over the centuries.[5]

The Norman dynasty had a major political, cultural and military impact on medieval Europe and the Near East.[6][7] The Normans were historically famed for their martial spirit and eventually for their Catholic piety, becoming exponents of the Catholic orthodoxy of the Romance community.[4] The original Norse settlers adopted the Gallo-Romance language of the Frankish land they settled, with their Old Norman dialect becoming known as Norman, Normaund or Norman French, an important literary language which is still spoken today in parts of mainland Normandy (Cotentinais and Cauchois dialects) and the nearby Channel Islands (Jèrriais and Guernésiais). The Duchy of Normandy, which arose from the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, was a great fief of medieval France. The Norman dukes exercised independent control of their holdings in Normandy, while at the same time being vassals owing fealty to the King of France, and under Richard I of Normandy (byname «Richard sans Peur» meaning «Richard the Fearless») the Duchy was forged into a cohesive and formidable principality in feudal tenure.[8][9] By the end of his reign in 996, the descendants of the Norse settlers «had become not only Christians but in all essentials Frenchmen. They had adopted the French language, French legal ideas, and French social customs, and had practically merged with the Frankish or Gallic population among whom they lived».[10] Between 1066 and 1204, as a result of the Norman conquest of England, most of the kings of England were also dukes of Normandy. In 1204, Philip II of France seized mainland Normandy by force of arms, having earlier declared the Duchy of Normandy to be forfeit to him. It remained a disputed territory until the Treaty of Paris of 1259, when the English sovereign ceded his claim to the Duchy, except for the Channel Islands. In the present day, the Channel Islands (the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey) are considered to be officially the last remnants of the Duchy of Normandy, and are not part of the United Kingdom but are instead self-governing Crown Dependencies.[11][12]

The Normans are noted both for their culture, such as their unique Romanesque architecture and musical traditions, and for their significant military accomplishments and innovations. Norman adventurers played a role in founding the Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II after briefly conquering southern Italy and Malta from the Saracens and Byzantines, and an expedition on behalf of their duke, William the Conqueror, led to the Norman conquest of England at the historic Battle of Hastings in 1066.[13] Norman and Anglo-Norman forces contributed to the Iberian Reconquista from the early eleventh to the mid-thirteenth centuries.[14]

In the Winter of 1070, William the Bastard alongside members of the Royal Family and their vassals committed a genocide against the peoples of Danish, Norwegian, Anglo-Scandinavian, and Celtic Britons of Elmet in North Britain, focused geographically around the territories of modern day Yorkshire.

Known at the time as the «Harrying of the North», the Domesday Book indicates that up to 70% of villages & settlements in Old Yorkshire were laid to waste, while modern academics estimate up to 250,000 people, or more than 1/3rd of the entire population of Yorkshire and North England were killed by the Norman forces under the English Royal Familiy.

Norman cultural and military influence spread from these new European centres to the Crusader states of the Near East, where their prince Bohemond I founded the Principality of Antioch in the Levant, to Scotland and Wales in Great Britain, to Ireland, and to the coasts of north Africa and the Canary Islands. The legacy of the Normans persists today through the regional languages and dialects of France, England, Spain, Quebec and Sicily, and also through the various cultural, judicial, and political arrangements they introduced in their conquered territories.[7][15]

Etymology[edit]

The English name «Normans» comes from the French words Normans/Normanz, plural of Normant,[16] modern French normand, which is itself borrowed from Old Low Franconian Nortmann «Northman»[17] or directly from Old Norse Norðmaðr, Latinized variously as Nortmannus, Normannus, or Nordmannus (recorded in Medieval Latin, 9th century) to mean «Norseman, Viking».[18]

The 11th century Benedictine monk and historian, Goffredo Malaterra, characterised the Normans thus:

Specially marked by cunning, despising their own inheritance in the hope of winning a greater, eager after both gain and dominion, given to imitation of all kinds, holding a certain mean between lavishness and greediness, that is, perhaps uniting, as they certainly did, these two seemingly opposite qualities. Their chief men were specially lavish through their desire of good report. They were, moreover, a race skillful in flattery, given to the study of eloquence, so that the very boys were orators, a race altogether unbridled unless held firmly down by the yoke of justice. They were enduring of toil, hunger, and cold whenever fortune laid it on them, given to hunting and hawking, delighting in the pleasure of horses, and of all the weapons and garb of war.[19]

Settling of Normandy[edit]

Duchy of Normandy between 911 and 1050. In blue the areas of intense Norse settlement

In the course of the 10th century, the initially destructive incursions of Norse war bands going upstream into the rivers of France penetrated further into interior Europe, and evolved into more permanent encampments that included local French women and personal property.[20] From 885 to 886, Odo of Paris (Eudes de Paris) succeeded in defending Paris against Viking raiders (one of the leaders was Sigfred) with his fighting skills, fortification of Paris and tactical shrewdness.[21] In 911, Robert I of France, brother of Odo, again defeated another band of Viking warriors in Chartres with his well-trained horsemen. This victory paved the way for Rollo’s baptism and settlement in Normandy.[22] The Duchy of Normandy, which began in 911 as a fiefdom, was established by the treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III (Charles the Simple) (879–929, ruled 893–929) of West Francia and the famed Viking ruler Rollo also known as Gaange Rolf (c. 846–c. 929), from Scandinavia, and was situated in the former Frankish kingdom of Neustria.[23] The treaty offered Rollo and his men the French coastal lands along the English Channel between the river Epte and the Atlantic Ocean coast in exchange for their protection against further Viking incursions.[23] As well as promising to protect the area of Rouen from Viking invasion, Rollo swore not to invade further Frankish lands himself, accepted baptism and conversion to Christianity and swore fealty to King Charles III. Robert I of France stood as godfather during Rollo’s baptism.[24] He became the first Duke of Normandy and Count of Rouen.[25] The area corresponded to the northern part of present-day Upper Normandy down to the river Seine, but the Duchy would eventually extend west beyond the Seine.[4] The territory was roughly equivalent to the old province of Rouen, and reproduced the old Roman Empire’s administrative structure of Gallia Lugdunensis II (part of the former Gallia Lugdunensis in Gaul).

Before Rollo’s arrival, Normandy’s populations did not differ from Picardy or the Île-de-France, which were considered «Frankish». Earlier Viking settlers had begun arriving in the 880s, but were divided between colonies in the east (Roumois and Pays de Caux) around the low Seine valley and in the west in the Cotentin Peninsula, and were separated by traditional pagii, where the population remained about the same with almost no foreign settlers. Rollo’s contingents from Scandinavia who raided and ultimately settled Normandy and parts of the European Atlantic coast included Danes, Norwegians, Norse–Gaels, Orkney Vikings, possibly Swedes, and Anglo-Danes from the English Danelaw territory which earlier came under Norse control in the late 9th century.

The descendants of Vikings replaced the Norse religion and Old Norse language with Catholicism (Christianity) and the Langue d’oil of the local people, descending from the Latin of the Romans. The Norman language (Norman French) was forged by the adoption of the indigenous langue d’oïl branch of Romance by a Norse-speaking ruling class, and it developed into the French regional languages that survive today.[4]

The Normans thereafter adopted the growing feudal doctrines of the rest of France, and worked them into a functional hierarchical system in both Normandy and in Norman dominated England.[8] The new Norman rulers were culturally and ethnically distinct from the old French aristocracy, most of whom traced their lineage to the Franks of the Carolingian dynasty from the days of Charlemagne in the 9th century. Most Norman knights remained poor and land-hungry, and by the time of the expedition and invasion of England in 1066, Normandy had been exporting fighting horsemen for more than a generation. Many Normans of Italy, France and England eventually served as avid Crusaders soldiers under the Italo-Norman prince Bohemund I of Antioch and the Angevin-Norman king Richard the Lion-Heart, one of the more famous and illustrious Kings of England.

Conquests and military offensives[edit]

Italy[edit]

The early Norman castle at Adrano

Opportunistic bands of Normans successfully established a foothold in southern Italy. Probably as the result of returning pilgrims’ stories, the Normans entered southern Italy as warriors in 1017 at the latest. In 999, according to Amatus of Montecassino, Norman pilgrims returning from Jerusalem called in at the port of Salerno when a Muslim attack occurred. The Normans fought so valiantly that Prince Guaimar III begged them to stay, but they refused and instead offered to tell others back home of the Prince’s request. William of Apulia tells that, in 1016, Norman pilgrims to the shrine of the Archangel Michael at Monte Gargano were met by Melus of Bari, a Lombard nobleman and rebel, who persuaded them to return with more warriors to help throw off the Byzantine rule, which they did.

The two most prominent Norman families to arrive in the Mediterranean were descendants of Tancred of Hauteville and the Drengot family.

A group of Normans with at least five brothers from the Drengot family fought the Byzantines in Apulia under the command of Melus of Bari. Between 1016 and 1024, in a fragmented political context, the County of Ariano [it] was founded by another group of Norman knights headed by Gilbert Buatère and hired by Melus of Bari. Defeated at Cannae, Melus of Bari escaped to Bamberg, Germany, where he died in 1022. The county, which replaced the pre-existing chamberlainship, is considered to be the first political body established by the Normans in the south of Italy.[26][27]

Then Rainulf Drengot, from the same family, received the county of Aversa from Duke Sergius IV of Naples in 1030.

The Hauteville family achieved princely rank by proclaiming Prince Guaimar IV of Salerno «Duke of Apulia and Calabria». He promptly awarded their elected leader, William Iron Arm, with the title of count in his capital of Melfi. The Drengot family thereafter attained the principality of Capua, and Emperor Henry III legally ennobled the Hauteville leader, Drogo, as «dux et magister Italiae comesque Normannorum totius Apuliae et Calabriae» («Duke and Master of Italy and Count of the Normans of all Apulia and Calabria«) in 1047.[28]

From these bases, the Normans eventually captured Sicily and Malta from the Muslims, under the leadership of the famous Robert Guiscard, a Hauteville, and his younger brother Roger the Great Count. Roger’s son, Roger II of Sicily, was crowned king in 1130 (exactly one century after Rainulf was «crowned» count) by Antipope Anacletus II. The Kingdom of Sicily lasted until 1194, when it was transferred to the House of Hohenstaufen through marriage.[29] The Normans left their legacy in many castles, such as William Iron Arm’s citadel at Squillace, and cathedrals, such as Roger II’s Cappella Palatina at Palermo, which dot the landscape and give a distinct architectural flavor to accompany its unique history.

Institutionally, the Normans combined the administrative machinery of the Byzantines, Arabs, and Lombards with their own conceptions of feudal law and order to forge a unique government. Under this state, there was great religious freedom, and alongside the Norman nobles existed a meritocratic bureaucracy of Jews, Muslims and Christians, both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox. The Kingdom of Sicily thus became characterized by Norman, Byzantine, Greek, Arab, Lombard and «native» Sicilian populations living in harmony, and its Norman rulers fostered plans of establishing an empire that would have encompassed Fatimid Egypt as well as the crusader states in the Levant.[30][31][32] One of the great geographical treatises of the Middle Ages, the «Tabula Rogeriana«, was written by the Andalusian al-Idrisi for King Roger II of Sicily, and entitled «Kitab Rudjdjar» («The Book of Roger«).[33]

The Iberian Peninsula[edit]

The Normans began appearing in the military confrontations between Christians and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula since the early eleventh century. The first Norman who appears in the narrative sources was Roger I of Tosny who according to Ademar of Chabannes and the later Chronicle of St Pierre le Vif went to aid the Barcelonese in a series of raids against the Andalusi Muslims c. 1018.[34] Later in the eleventh century, other Norman adventurers such as Robert Crispin and Walter Giffard participated in the probably papal organised siege of Barbastro of 1064. Even after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the Normans continued to participate in ventures in the peninsula. After the Frankish conquest of the Holy Land during the First Crusade, the Normans began to be encouraged to participate in ventures of conquest in the northeast of the peninsula. The most significant example of this was the incursion of Rotrou II of Perche and Robert Burdet in the 1120s in the Ebro frontier. By 1129 Robert Burdet had been granted a semi-independent principality in the city of Tarragona by the then Archbishop of this see, Oleguer Bonestruga. Several others of Rotrou’s Norman followers were rewarded with lands in the Ebro valley by King Alfonso I of Aragon for their services.[35]

With the rising popularity of the sea route to the Holy Land, Norman and Anglo-Norman crusaders also started to be encouraged locally by Iberian prelates to participate in the Portuguese incursions into the western areas of the Peninsula. The first of these incursions occurred when a fleet of these Crusaders was invited by the Portuguese king Afonso I Henriques to conquer the city of Lisbon in 1142.[36] Although this Siege of Lisbon (1142) was a failure it created a precedent for their involvement in Portugal. So in 1147 when another group of Norman and other groups of crusaders from Northern Europe arrived in Porto on their way to join the crusading forces of the Second Crusade, the Bishop of Porto and later Afonso Henriques according to De expugnatione Lyxbonensi convinced them to help with the siege of Lisbon. This time the city was captured and according to the arrangement agreed upon with the Portuguese monarch many of them settled in the newly sacked city.[37] The following year the remainder of the crusading fleet, including a substantial number of Anglo-Normans, was invited by the count of Barcelona, Ramon Berenguer IV, to participate in the siege of Tortosa (1148). Again the Normans were rewarded with lands in the newly conquered frontier city.[38]

North Africa[edit]

Between 1135 and 1160, the Norman Kingdom of Sicily conquered and kept as vassals several cities on the Ifriqiya coast, corresponding to Tunisia and parts of Algeria and Libya today.

They were lost to the Almohads.

Byzantium[edit]

Soon after the Normans began to enter Italy, they entered the Byzantine Empire and then Armenia, fighting against the Pechenegs, the Bulgarians, and especially the Seljuk Turks. Norman mercenaries were first encouraged to come to the south by the Lombards to act against the Byzantines, but they soon fought in Byzantine service in Sicily. They were prominent alongside Varangian and Lombard contingents in the Sicilian campaign of George Maniaces in 1038–40. There is debate whether the Normans in Greek service actually were from Norman Italy, and it now seems likely only a few came from there. It is also unknown how many of the «Franks», as the Byzantines called them, were Normans and not other Frenchmen.

Achronological map of the Norman Conquests

One of the first Norman mercenaries to serve as a Byzantine general was Hervé in the 1050s. By then, however, there were already Norman mercenaries serving as far away as Trebizond and Georgia. They were based at Malatya and Edessa, under the Byzantine duke of Antioch, Isaac Komnenos. In the 1060s, Robert Crispin led the Normans of Edessa against the Turks. Roussel de Bailleul even tried to carve out an independent state in Asia Minor with support from the local population in 1073, but he was stopped in 1075 by the Byzantine general and future emperor Alexius Komnenos.[39]

Some Normans joined Turkish forces to aid in the destruction of the Armenian vassal-states of Sassoun and Taron in far eastern Anatolia. Later, many took up service with the Armenian state further south in Cilicia and the Taurus Mountains. A Norman named Oursel led a force of «Franks» into the upper Euphrates valley in northern Syria. From 1073 to 1074, 8,000 of the 20,000 troops of the Armenian general Philaretus Brachamius were Normans—formerly of Oursel—led by Raimbaud. They even lent their ethnicity to the name of their castle: Afranji, meaning «Franks». The known trade between Amalfi and Antioch and between Bari and Tarsus may be related to the presence of Italo-Normans in those cities while Amalfi and Bari were under Norman rule in Italy.

Several families of Byzantine Greece were of Norman mercenary origin during the period of the Comnenian Restoration, when Byzantine emperors were seeking out western European warriors. The Raoulii were descended from an Italo-Norman named Raoul, the Petraliphae were descended from a Pierre d’Aulps, and that group of Albanian clans known as the Maniakates were descended from Normans who served under George Maniaces in the Sicilian expedition of 1038.

Robert Guiscard, another Norman adventurer previously elevated to the dignity of count of Apulia as the result of his military successes, ultimately drove the Byzantines out of southern Italy. Having obtained the consent of Pope Gregory VII and acting as his vassal, Robert continued his campaign conquering the Balkan peninsula as a foothold for western feudal lords and the Catholic Church. After allying himself with Croatia and the Catholic cities of Dalmatia, in 1081 he led an army of 30,000 men in 300 ships landing on the southern shores of Albania, capturing Valona, Kanina, Jericho (Orikumi), and reaching Butrint after numerous pillages. They joined the fleet that had previously conquered Corfu and attacked Dyrrachium from land and sea, devastating everything along the way. Under these harsh circumstances, the locals accepted the call of Emperor Alexios I Comnenos to join forces with the Byzantines against the Normans. The Byzantine forces could not take part in the ensuing battle because it had started before their arrival. Immediately before the battle, the Venetian fleet had secured a victory in the coast surrounding the city. Forced to retreat, Alexios ceded the city of Dyrrachium to the Count of the Tent (or Byzantine provincial administrators) mobilizing from Arbanon (i.e., ἐξ Ἀρβάνων ὁρμωμένω Κομισκόρτη; the term Κομισκόρτη is short for κόμης της κόρτης meaning «Count of the Tent»).[40] The city’s garrison resisted until February 1082, when Dyrrachium was betrayed to the Normans by the Venetian and Amalfitan merchants who had settled there. The Normans were now free to penetrate into the hinterland; they took Ioannina and some minor cities in southwestern Macedonia and Thessaly before appearing at the gates of Thessalonica. Dissension among the high ranks coerced the Normans to retreat to Italy. They lost Dyrrachium, Valona, and Butrint in 1085, after the death of Robert.

A few years after the First Crusade, in 1107, the Normans under the command of Bohemond, Robert’s son, landed in Valona and besieged Dyrrachium using the most sophisticated military equipment of the time, but to no avail. Meanwhile, they occupied Petrela, the citadel of Mili at the banks of the river Deabolis, Gllavenica (Ballsh), Kanina and Jericho. This time, the Albanians sided with the Normans, dissatisfied by the heavy taxes the Byzantines had imposed upon them. With their help, the Normans secured the Arbanon passes and opened their way to Dibra. The lack of supplies, disease and Byzantine resistance forced Bohemond to retreat from his campaign and sign a peace treaty with the Byzantines in the city of Deabolis.

The further decline of Byzantine state-of-affairs paved the road to a third attack in 1185, when a large Norman army invaded Dyrrachium, owing to the betrayal of high Byzantine officials. Some time later, Dyrrachium—one of the most important naval bases of the Adriatic—fell again to Byzantine hands.

England[edit]

The Normans were in contact with England from an early date. Not only were their original Viking brethren still ravaging the English coasts, they occupied most of the important ports opposite England across the English Channel. This relationship eventually produced closer ties of blood through the marriage of Emma, sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy, and King Ethelred II of England. Because of this, Ethelred fled to Normandy in 1013, when he was forced from his kingdom by Sweyn Forkbeard. His stay in Normandy (until 1016) influenced him and his sons by Emma, who stayed in Normandy after Cnut the Great’s conquest of the isle.

When Edward the Confessor finally returned from his father’s refuge in 1041, at the invitation of his half-brother Harthacnut, he brought with him a Norman-educated mind. He also brought many Norman counsellors and fighters, some of whom established an English cavalry force. This concept never really took root, but it is a typical example of Edward’s attitude. He appointed Robert of Jumièges Archbishop of Canterbury and made Ralph the Timid Earl of Hereford.

On 14 October 1066, William the Conqueror gained a decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings, which led to the conquest of England three years later;[41] this can be seen on the Bayeux tapestry. The invading Normans and their descendants largely replaced the Anglo-Saxons as the ruling class of England. The nobility of England were part of a single Norman culture and many had lands on both sides of the channel. Early Norman kings of England, as Dukes of Normandy, owed homage to the King of France for their land on the continent. They considered England to be their most important holding (it brought with it the title of King—an important status symbol).

Eventually, the Normans merged with the natives, combining languages and traditions, so much so that Marjorie Chibnall says «writers still referred to Normans and English; but the terms no longer meant the same as in the immediate aftermath of 1066.»[42] In the course of the Hundred Years’ War, the Norman aristocracy often identified themselves as English. The Anglo-Norman language became distinct from the French spoken in Paris, something that was the subject of some humour by Geoffrey Chaucer. The Anglo-Norman language was eventually absorbed into the Anglo-Saxon language of their subjects (see Old English) and influenced it, helping (along with the Norse language of the earlier Anglo-Norse settlers and the Latin used by the church) in the development of Middle English, which, in turn, evolved into Modern English.

Ireland[edit]